A Comprehensive Review on Pre- and Post-Harvest Perspectives of Potato Quality and Non-Destructive Assessment Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Pre-Harvest Potato Quality Aspects

2.1. Genetic and Cultivar Background

2.2. Soil Nutrients and Fertility

2.3. Water and Irrigation Stress

2.4. Pest and Microbial Stress

3. Post-Harvesting Quality Aspects

3.1. Storage Conditions

3.2. Physiological Quality, Disorders, and Defects

4. Nutritional Quality

4.1. Carbohydrates

4.2. Protein

4.3. Micronutrient and Bioactive Compounds

5. Processing Quality

6. Nondestructive Assessment of Potato Quality

6.1. Nondestructive Assessment for Pre-Harvest Potato Quality

6.2. Nondestructive Assessment for Post-Harvest Potato Quality

6.2.1. Damage and Bruises

6.2.2. Sprouting

6.2.3. Disease

6.2.4. Shape, Size and Compositional Quality

7. Integration Between Pre- and Post-Harvest Research and Future Prospective

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chetty, V.J.; Narváez-Vásquez, J.; Orozco-Cárdenas, M.L. Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). In Agrobacterium Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, J.G.; Francisco-Ortega, J. The early history of the potato in Europe. Euphytica 1993, 70, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolničar, P. Importance of potato as a crop and practical approaches to potato breeding. In Solanum tuberosum: Methods and Protocols; Dobnik, D., Gruden, K., Ramšak, Z., Coll, A., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hijmans, R.J. Global distribution of the potato crop. Am. J. Potato Res. 2001, 78, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobnik, D.; Gruden, K.; Ramšak, Ž.; Coll, A. (Eds.) Solanum tuberosum: Methods and Protocols; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 2354. [Google Scholar]

- Lutaladio, N.B.; Castaldi, L. Potato: The hidden treasure. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2009, 22, 491–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. A Guide to the International Day of Potato. Available online: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/1738150/ (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Singh, J.; Kaur, L. (Eds.) Advances in Potato Chemistry and Technology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wijesinha-Bettoni, R.; Mouillé, B. The contribution of potatoes to global food security, nutrition and healthy diets. Am. J. Potato Res. 2019, 96, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Sharma, V.; Dua, V.K.; Gupta, V.K.; Kumar, D. Variations in micronutrient content in tubers of Indian potato varieties. Potato J. 2017, 44, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Beals, K.A. Potatoes, nutrition and health. Am. J. Potato Res. 2019, 96, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlingame, B.; Mouillé, B.; Charrondiere, R. Nutrients, bioactive non-nutrients and anti-nutrients in potatoes. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2009, 22, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarre, D.A.; Goyer, A.; Shakya, R. Nutritional value of potatoes: Vitamin, phytonutrient, and mineral content. In Advances in Potato Chemistry and Technology; Singh, J., Kaur, L., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 395–424. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.R. Antioxidants in potato. Am. J. Potato Res. 2005, 82, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.R.; Durst, R.W.; Wrolstad, R.; De Jong, W. Variability of phytonutrient content of potato in relation to growing location and cooking method. Potato Res. 2008, 51, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezekiel, R.; Singh, N.; Sharma, S.; Kaur, A. Beneficial phytochemicals in potato—A review. Food Res. Int. 2013, 50, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, S.A.; Morris, J.R. Perspective: Potatoes, quality carbohydrates, and dietary patterns. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, A.; Goffart, J.P.; Kromann, P.; Andrade-Piedra, J.; Polar, V.; Hareau, G. The potato of the future: Opportunities and challenges in sustainable agri-food systems. Potato Res. 2021, 64, 681–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgos, G.; Zum Felde, T.; Andre, C.; Kubow, S. The potato and its contribution to the human diet and health. In The Potato Crop: Its Agricultural, Nutritional and Social Contribution to Humankind; Campos, H., Ortiz, O., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 37–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; El-Bialee, N.; Saad, M.; Romano, E. Non-destructive quality inspection of potato tubers using automated vision system. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2020, 10, 2419–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Sun, L.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Xie, X.; Xu, Y. Non-destructive classification of defective potatoes based on hyperspectral imaging and support vector machine. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2019, 99, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshaghi, A.; Ashourian, M.; Ghabeli, L. Potato diseases detection and classification using deep learning methods. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 5725–5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitoyannis, I.S.; Vaitsi, O.; Mavromatis, A. Potato: A comparative study of the effect of cultivars and cultivation conditions and genetic modification on the physico-chemical properties of potato tubers in conjunction with multivariate analysis towards authenticity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 48, 799–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prysiazhniuk, L.; Sonets, T.; Shytikova, Y.; Melnyk, S.; Dikhtiar, I.; Mazhuha, K.; Sorochinsky, B. The environmental and genetic factors affect the productivity and quality of potato cultivars. Zemdirb.-Agric. 2023, 110, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seid, E.; Tessema, L. Review on breeding potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) genotypes for processing quality traits. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 2021, 12, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zaheer, K.; Akhtar, M.H. Potato production, usage, and nutrition—A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Shah, A.N.; Shah, A.A.; Nadeem, M.A.; Alsaleh, A.; Javed, T.; Alotaibi, S.S.; Abdelsalam, N.R. Genome-wide analysis of invertase gene family, and expression profiling under abiotic stress conditions in potato. Biology 2022, 11, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, M.A.; Ali, E.; Salman, S.R. Effect of nitrogen application and fertigation scheduling on potato yield performance under drip irrigation system. Gesunde Pflanz. 2023, 75, 2909–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, M.; Fu, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Shao, Y.; Xing, Y.; Wang, X. Coupling effects of irrigation amount and fertilization rate on yield, quality, water and fertilizer use efficiency of different potato varieties in Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 287, 108446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Selim, D.A.F.H.; Elbagory, M.; Othman, M.M.; Omara, A.E.D.; Mohamed, M.H. Plant growth, yield and quality of potato crop in relation to potassium fertilization. Agronomy 2021, 11, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabian, S.; Farhangi-Abriz, S.; Qin, R.; Noulas, C.; Sathuvalli, V.; Charlton, B.; Loka, D.A. Potassium: A vital macronutrient in potato production—A review. Agronomy 2021, 11, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Li, M.; Shi, M.; Kang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Qin, S. Effects of potassium fertilizer base/topdressing ratio on dry matter quality, photosynthetic fluorescence characteristics and carbon and nitrogen metabolism of potato. Potato Res. 2025, 68, 835–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorrilla, C.; Navarro, F.; Vega-Semorile, S.; Palta, J.; Molina, L.; La Molina, A. QTL for pitted scab, hollow heart, and tuber calcium identified in a tetraploid population of potato derived from an Atlantic × Superior cross. Crop Sci. 2021, 61, 1630–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, M.; Six, J. Soil structure and microbiome functions in agroecosystems. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Lin, J.Y.; Sayre, J.M.; Schmidt, R.; Fonte, S.J.; Rodrigues, J.L.; Scow, K.M. Compost amendment maintains soil structure and carbon storage by increasing available carbon and microbial biomass in agricultural soil—A six-year field study. Geoderma 2022, 427, 116117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, S.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Q. Nutrient expert system optimizes fertilizer management to improve potato productivity and tuber quality. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hadidi, E.; Ewais, M.; Shehata, A. Fertilization effects on potato yield and quality. J. Soil Sci. Agric. Eng. 2017, 8, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.L.; Guo, T.W.; Song, S.Y.; Zhang, P.L.; Zhang, X.C.; Zhao, C. Balanced fertilizer management strategy enhances potato yield and marketing quality. Agron. J. 2016, 108, 2235–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.W.; Toth, Z. Effect of drought stress on potato production: A review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaman, K.; Irmak, S.; Koudahe, K.; Allen, S. Irrigation management in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) production: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jama-Rodzenska, A.; Janik, G.; Walczak, A.; Adamczewska-Sowinska, K.; Sowinski, J. Tuber yield and water efficiency of early potato varieties (Solanum tuberosum L.) cultivated under various irrigation levels. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ierna, A.; Mauromicale, G. How irrigation water saving strategy can affect tuber growth and nutritional composition of potato. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 299, 111034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsák, M.; Kotíková, Z.; Hnilička, F.; Lachman, J. Effect of drought and waterlogging on saccharides and amino acids content in potato tubers. Plant Soil Environ. 2021, 67, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kupriyanovich, Y.; Wagg, C.; Zheng, F.; Hann, S. Water deficit duration affects potato plant growth, yield and tuber quality. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, J.; Thornton, M.; Nolte, P. Potato Production Systems; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.S.; Stevenson, W.R. Water management, disease development, and potato production. Am. Potato J. 1990, 67, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meno, L.; Escuredo, O.; Rodríguez-Flores, M.S.; Seijo, M.C. Looking for a sustainable potato crop. field assessment of early blight management. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 308–309, 108617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Konar, A. Integrated disease and pest management under potato based cropping system. In Integrated Pest Management in Diverse Cropping Systems; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 427–459. [Google Scholar]

- Charkowski, A.; Sharma, K.; Parker, M.L.; Secor, G.A.; Elphinstone, J. Bacterial Diseases of Potato. Am. J. Potato Res. 2020, 94, 283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Nolte, P.; Miller, J.; Duellman, K.M.; Gevens, A.J.; Banks, E. Disease management. In Potato Production Systems; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 203–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, V. Management of soil and tuber borne diseases of potato. Indian Hortic. 2019, 64, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, M.N.; Taheri, A.; Dumenyo, C.K. Development of PCR-based detection system for soft rot pectobacteriaceae pathogens using molecular signatures. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-El-Khair, H.; Abdel-Gaied, T.G.; Mikhail, M.S.; Abdel-Alim, A.I.; El-Nasr, H.I.S. Biological control of Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum, the causal agent of bacterial soft rot in vegetables, in vitro and in vivo tests. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2021, 45, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashmawy, N.A.; El-Bebany, A.F.; Shams, A.H.M.; Shoeib, A.A. Identification and differentiation of soft rot and blackleg bacteria from potato using nested and multiplex PCR. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2020, 127, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhalag, K.; Elbadry, N.; Farag, S.; Hagag, M.; Hussien, A. Etiology of potato soft rot and blackleg diseases complex in Egypt. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2020, 127, 855–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, J.; Genin, S.; Magori, S.; Citovsky, V.; Sriariyanum, M.; Ronald, P.; Dow, M.; Verdier, V.; Beer, S.V.; Machado, M.A.; et al. Top 10 plant pathogenic bacteria in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.; Gevens, A.; Charkowski, A.; Allen, C.; Jansky, S. Potato common scab: A review of the causal pathogens, management practices, varietal resistance screening methods, and host resistance. Am. J. Potato Res. 2017, 94, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabhikhi, H.S.; Hunjan, M.S.; Kaur, Y. Development of Common Scab in Potato Cv. Kufri pukhraj in the Indian Punjab is influenced by scab lesion severity on seed tubers and by crop duration in the field. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2023, 130, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Li, J.; Yang, S.; Wang, W.; Min, F.; Guo, M.; Zhang, S.; Dong, X.; Hu, L.; Li, Z.; et al. Streptomyces rhizophilus causes potato common scab disease. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shaughnessy, S.A.; Rho, H.; Colaizzi, P.D.; Workneh, F.; Rush, C.M. Impact of Zebra Chip disease and irrigation levels on potato production. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 269, 107647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Crous, P.W.; Ades, P.K.; Wang, W.; Liu, F.; Damm, U.; Vaghefi, N.; Taylor, P.W.J. Potato leaf infection caused by Colletotrichum coccodes and C. nigrum. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2024, 170, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, M.; Shoaib, A.; Javaid, A.; Perveen, S.; Umer, M.; Arif, M.; Cheng, C. Exploration of resistance level against black scurf caused by rhizoctonia solani in different cultivars of potato. Plant Stress 2024, 12, 100476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azil, N.; Stefańczyk, E.; Sobkowiak, S.; Chihat, S.; Boureghda, H.; Śliwka, J. Identification and pathogenicity of Fusarium spp. associated with tuber dry rot and wilt of potato in algeria. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2021, 159, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, S.; Khatoon, Z.; Amna; Ahmad, I.; Muneer, M.A.; Kamran, M.A.; Ali, J.; Ali, B.; Chaudhary, H.J.; Munis, M.F.H. Bacillus sp. PM31 harboring various plant growth-promoting activities regulates Fusarium dry rot and wilt tolerance in potato. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2023, 69, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, K.M.; Townsend, P.A.; Chlus, A.; Herrmann, I.; Couture, J.J.; Larson, E.R.; Gevens, A.J. Hyperspectral measurements enable pre-symptomatic detection and differentiation of contrasting physiological effects of late blight and early blight in potato. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.K.; Sharma, S.; Shah, M.A. Potato pests and diseases: A global perspective. In Sustainable Management of Potato Pests and Diseases; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuze, J.F.; Souza-Dias, J.A.C.; Jeevalatha, A.; Figueira, A.R.; Valkonen, J.P.T.; Jones, R.A.C. Viral Diseases in Potato. In The Potato Crop; Campos, H., Ortiz, O., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 389–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Tiwari, R.K.; Sundaresha, S.; Kaundal, P.; Raigond, B. Potato viruses and their management. In Sustainable Management of Potato Pests and Diseases; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 309–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, A.K.; Hilton, A.J. Black dot (Colletotrichum coccodes): An increasingly important disease of potato. Plant Pathol. 2003, 52, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebola, M.O.; Bello, T.S.; Seriki, E.A.; Aremu, M.B. Evaluation of three plant species to control black scurf disease of Irish potato (Solanum Tuberosum Linn.). Not. Sci. Biol. 2020, 12, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuri, T.; Biswas, M.K. Impact of different culture media, temperature and PH on growth of rhizoctonia solani i kühn causes black scurf of potato. Plant Cell Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. 2021, 22, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Kong, Y.; Guo, M.; Dong, X.; Min, F.; Wei, Q.; Wang, W.; Mao, Y.; Gu, X.; Wang, L. First report of black scurf caused by Rhizoctonia solani AG 2-2IV on potato tubers in Heilongjiang Province, China. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.K.; Patidar, J.K.; Singh, R.; Roy, S. Screening of potato varieties against black scurf caused by Rhizoctonia solani kuhn. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2021, 10, 1444–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanowski, A.; Avis, T.J.; Pelletier, S.; Tweddell, R.J. Management of potato dry rot. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 84, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauske, M.J.; Robinson, A.P.; Gudmestad, N.C. Early Blight in Potato. NDSU Agriculture and Extension, North Dakota State University, 2018; Publication PP1892. 7. Available online: https://www.ag.ndsu.edu/publications/crops/early-blight-in-potato (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Nie, X.; Dickison, V.; Singh, M.; de Koeyer, D.; Xu, H.; Bai, Y.; Hawkins, G. Potato tuber necrosis induced by alfalfa mosaic virus depends on potato cultivar rather than on virus strain. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Sun, L.; Li, Y.; Ye, D. Detection of bruised potatoes using hyperspectral imaging technique based on discrete wavelet transform. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2019, 103, 103054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowokinos, J.R. Biochemical and molecular control of cold-induced sweetening in potatoes. Am. J. Potato Res. 2001, 78, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, M. The Harvested Crop. In Potato Biology and Biotechnology: Advances and Perspectives; Elsevier Science BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 441–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gikundi, E.N.; Buzera, A.K.; Orina, I.N.; Sila, D.N. Storability of Irish potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) varieties grown in Kenya, under different storage conditions. Potato Res. 2023, 66, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Q.; Xu, C.; Tana; Wang, H.; Yue, X.; Yan, C.; Sun, Y. Research on the temperature and humidity distribution characteristics in potato storage facilities: Experimental analysis and numerical simulation. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1594791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomão, H.M.; Suchoronczek, A.; Jadoski, S.O.; Suchoronczek, A.; Cristina, K.; Hartmann, D.; Cosmedamiana, J.; Bueno, M. Quality of potato tubers according to the storage time. Commun. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, T.; Królczyk, J.B. Method for the reduction of natural losses of potato tubers during their long-term storage. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiaitsi, E.; Tosetti, R.; Terry, L.A. Susceptibility to blackheart disorder in potato tubers is influenced by sugar and phenolic profile. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 162, 111094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; He, Y.; Li, X.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, M.; Huang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Jian, H.; Du, Z.; Lv, H. Assessment of optical properties and monte carlo-based simulation of light propagation in blackhearted potatoes. Sensors 2025, 25, 3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismayil, M.; Kumar, N.; Bankar, D.; Chauhan, A. Novel Approaches in Plant Protection; Integrated Publications: Delhi, India, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.I.; Chang, D.C.; Cho, J.H.; Yu, D.L.; Nam, J.H.; Yu, H.S.; Lee, S. Storage condition that induce black heart of potato (Solanum tuberosom L.). In Proceedings of the Korean Society of Crop Science Conference, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 24–28 April 2017; p. 193. [Google Scholar]

- Atiq, M.; Faizan Ullah, M.; Ahmed Rajput, N.; Hameed, A.; Ahmad, S.; Usman, M.; Hasnain, A.; Nawaz, A.; Iqbal, S.; Ahmad, H.; et al. Surveillance and management of brown spot of potato. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2024, 57, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimo, F.; Pentangelo, A.; Pane, C.; Parisi, B.; Mandolino, G. Relationships between internal brown spot and skin roughness in potato tubers under field conditions. Potato Res. 2018, 61, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjar, G.; Quellec, S.; Pépin, J.; Challois, S.; Joly, G.; Deleu, C.; Leport, L.; Musse, M. MRI Investigation of internal defects in potato tubers with particular attention to rust spots induced by water stress. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 180, 111600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingwal, S.; Sinha, A.; Rai, J.P.; Prabhakar, C.S.; Srinivasaraghavan, A. Brown spot of potato caused by alternaria alternata: An emerging problem of potato in eastern India. Potato Res. 2022, 65, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.K. Screening for hollow heart in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Genotypes. Potato J. 2020, 47, 54–58. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, H.; Ranjan, R.S. Effect of soil moisture deficit on marketable yield and quality of potatoes. Biosyst. Eng. J. 2015, 57, 1.25–1.37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhalsamant, K.; Singh, C.B.; Lankapalli, R. A Review on greening and glycoalkaloids in potato tubers: Potential solutions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 13819–13831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanios, S.; Thangavel, T.; Eyles, A.; Tegg, R.S.; Nichols, D.S.; Corkrey, R.; Wilson, C.R. Suberin deposition in potato periderm: A novel resistance mechanism against tuber greening. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanios, S.; Tegg, R.; Eyles, A.; Thangavel, T.; Wilson, C. Potato Tuber Greening risk is associated with tuber nitrogen content. Am. J. Potato Res. 2020, 97, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Feng, H.; Wang, X.; Cai, C. Advances in the modulation of potato tuber dormancy and sprouting. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, M.W.; Nafees, M.; Amin, M.; Asad, H.U.; Ahmad, I. Physiology of tuber dormancy and its mechanism of release in potato. J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2021, 4, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visse-Mansiaux, M.; Soyeurt, H.; Herrera, J.M.; Torche, J.M.; Vanderschuren, H.; Dupuis, B. Prediction of potato sprouting during storage. Field Crops Res. 2022, 278, 108396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Tang, C.; Zhou, X.; Yang, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, L.; Yang, M.; Li, D.; Li, L. Potatoes dormancy release and sprouting commencement: A review on current and future prospects. Food Front. 2023, 4, 1001–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bussan, A.J.; Bethke, P.C. Stem-end defect in chipping potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.) as influenced by mild environmental stresses. Am. J. Potato Res. 2012, 89, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlista, A.D.; Ojala, J.C. Potatoes: Chip and French fry processing. In Processing Vegetables: Science and Technology; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 237–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.L.; Love, S.L.; Sowokinos, J.R.; Thornton, M.K.; Shock, C.C. Review of the sugar end disorder in potato (Solanum tuberosum, L.). Am. J. Potato Res. 2008, 85, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldredge, E.P.; Holmes, Z.A.; Mosley, A.R.; Shock, C.C.; Stieber, T.D. Effects of transitory water stress on potato tuber stem-end reducing sugar and fry color. Am. Potato J. 1996, 73, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, M.; Buhrig, W.; Olsen, N. The relationship between soil temperature and sugar ends in potato. Potato Res. 2010, 53, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, C.M.; Byrd, S.; Gergela, D.; Rowland, D.L. Potato Physiological Disorders: Brown Center and Hollow Heart; Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida Cooperative Extension Service: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tanios, S.; Eyles, A.; Tegg, R.; Wilson, C. Potato tuber greening: A review of predisposing factors, management and future challenges. Am. J. Potato Res. 2018, 95, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudzińska, M.; Boguszewska-Mańkowska, D.; Zarzyńska, K. Drought stress during the growing season: Changes in reducing sugars, starch content and respiration rate during storage of two potato cultivars differing in drought sensitivity. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2022, 208, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buono, V.; Paradiso, A.; Serio, F.; Gonnella, M.; De Gara, L.; Santamaria, P. Tuber quality and nutritional components of “early” potato subjected to chemical haulm desiccation. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2009, 22, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist-Kreuze, H.; Bonierbale, M.; Grüneberg, W.J.; Mendes, T.; De Boeck, B.; Campos, H. Potato and sweetpotato breeding at the international potato center: Approaches, outcomes and the way forward. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USDA FoodData Central. Flour, Potato—Nutrients—Foundation. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/food-details/2261422/nutrients (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- USDA FoodData Central. Potatoes, Russet, Without Skin, Raw—Nutrients—Foundation. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/food-details/2346401/nutrients (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- USDA FoodData Central. Potatoes, Red, Without Skin, Raw—Nutrients—Foundation. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/food-details/2346402/nutrients (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- USDA FoodData Central. Potatoes, Gold, Without Skin, Raw—Nutrients—Foundation. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/food-details/2346403/nutrients (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Raigond, P.; Atkinson, F.S.; Lal, M.K.; Thakur, N.; Singh, B.; Mishra, T. Potato Carbohydrates. In Potato: Nutrition and Food Security; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raatz, S.K.; Idso, L.; Johnson, L.K.; Jackson, M.I.; Combs, G.F., Jr. Resistant starch analysis of commonly consumed potatoes: Content varies by cooking method and service temperature but not by variety. Food Chem. 2016, 208, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mareček, J.; Frančáková, H.; Bojňanská, T.; Fikselová, M.; Mendelová, A.; Ivanišová. Carbohydrates in varieties of stored potatoes and influence of storage on quality of fried products. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2013, 2, 1744–1753. [Google Scholar]

- Hassel, R.L.; Kelly, D.M.; Wittmeyer, E.C.; Wallace, C.; Grassbaugh, E.M.; Elliott, J.Y.; Wenneker, G.L. Ohio potato cultivar trials. Ohio State Univ. Hortic. Ser. 1997, 666, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D.; Ezekiel, R.; Singh, B.; Ahmed, I. Conversion table for specific gravity, dry matter and starch content from under water weight of potatoes grown in north-Indian plains. Potato J. 2005, 32, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinkopf, G.E.; Westermann, D.T.; Wille, M.J.; Kleinschmidt, G.D. Specific gravity of Russet Burbank potatoes. Am. Potato J. 1987, 64, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Qayum, A.; Xiuxiu, Z.; Liu, L.; Hussain, K.; Yue, P.; Yue, S.; Koko, M.Y.; Hussain, A.; Li, X. Potato protein: An emerging source of high quality and allergy free protein, and its possible future based products. Food Res. Int. 2021, 148, 110583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.; Reichert, C.L.; Schmid, M.; Loeffler, M. Physical, chemical and biochemical modification approaches of potato (peel) constituents for bio-based food packaging concepts: A review. Foods 2022, 11, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayimbila, F.; Keawsompong, S. Nutritional quality and biological application of mushroom protein as a novel protein alternative. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2023, 12, 290–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, C.R.; Kurilich, A.C.; Davignon, J. The role of potatoes and potato components in cardiometabolic health: A review. Ann. Med. 2013, 45, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pęksa, A.; Sciences, J.M.-A. Potato industry by-products as a source of protein with beneficial nutritional, functional, health-promoting and antimicrobial properties. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narwojsz, A.; Borowska, E.J.; Polak-Śliwińska, M.; Danowska-Oziewicz, M. Effect of different methods of thermal treatment on starch and bioactive compounds of potato. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2020, 75, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasheed, H.; Ahmad, D.; Bao, J. Genetic diversity and health properties of polyphenols in potato. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cebulak, T.; Krochmal-Marczak, B.; Stryjecka, M.; Krzysztofik, B.; Sawicka, B.; Danilčenko, H.; Jarienè, E. Phenolic acid content and antioxidant properties of edible potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) with various tuber flesh colours. Foods 2023, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.R. Anthocyanin and carotenoid contents in potato: Breeding for the specialty market. Proc Ida Winter Commod Sch 2006, 39, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Lokendrajit, N.; Singh, C.B.; Swapana, N.; Singh, M.S. Evaluation of nutritional value of two local potato cultivars (Aberchaibi and Amubi) of Manipur, Northeast India. Bioscan 2013, 8, 589–593. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte-Correa, Y.; Vega-Castro, O.; López-Barón, N.; Singh, J. Fortifying compounds reduce starch hydrolysis of potato chips during gastro-small intestinal digestion in vitro. Starch-Stärke 2021, 73, 2000196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bede, D.; Lou, Z. Recent developments in resistant starch as a functional Food. Starch-Stärke 2021, 73, 2000139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, R.; Taneda, K.; Pelpolage, S.W.; Bochimoto, H.; Fukuma, N.; Shimada, K.; Tani, M.; Han, K.H.; Fukushima, M. Effect of calcium-fortified potato starch on cecal fermentation and fat accumulation in rats. Starch-Stärke 2021, 73, 2000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammoun, M.; Gargouri-Bouzid, R.; Nouri-Ellouz, O. Effect of deep-fat frying on french fries quality of new somatic hybrid potatoes. Potato Res. 2022, 65, 915–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngadi, M.; Adedeji, A.A.; Kassama, L. Microstructural changes during frying of foods. In Advances in Deep-Fat Frying of Foods; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; pp. 169–200. ISBN 9781420055597. [Google Scholar]

- Szczesniak, A.S. The meaning of textural characteristics-crispness. J. Texture Stud. 1988, 19, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, N.G.; Bussell, W.T. Good potatoes for good potato crisps, a review of current potato crisp quality control and manufacture. Food 2007, 1, 271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Fick, R.J.; Brook, R.C. Threshold Sugar Concentrations in Snowden Potatoes During Storage. Am. J. Potato Res. 1999, 76, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, L.; Putz, B. Quality of potato crisps. influence of variety, type of frying oil and frying temperature on crisp quality. Kartoffelbau 2003, 11, 424–427. [Google Scholar]

- Ağçam, E. Modeling of the changes in some physical and chemical quality attributes of potato chips during frying process. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wu, G.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Qi, X.; Jin, Q.; Wang, X. Analysis of quality and microstructure of freshly potato strips fried with different oils. LWT 2020, 133, 110038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Tarmizi, A.H.; Ismail, R. Comparison of the Frying Stability of Standard Palm Olein and Special Quality Palm Olein. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2008, 85, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Razak, R.A.; Ahmad Tarmizi, A.H.; Kuntom, A.; Sanny, M.; Ismail, I.S. Intermittent frying effect on french fries in palm olein, sunflower, soybean and canola oils on quality indices, 3-monochloropropane-1,2-diol esters (3-mcpde), glycidyl esters (ge) and acrylamide contents. Food Control 2021, 124, 107887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, K.; Linko, Y.Y.; Linko, P. The role of trans fatty acids in human nutrition. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2000, 102, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.S.; Zeng, X.F.; Liu, Z.N.; Zhao, Q.H.; Tan, Y.T.; Gao, J.; Li, H.L.; Xiang, Y.B. Diet and liver cancer risk: A narrative review of epidemiological evidence. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 124, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueik, V.; Robert, P.; Bouchon, P. Vacuum frying reduces oil uptake and improves the quality parameters of carrot crisps. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.M.; Oliveira, F.A.R. Modelling the kinetics of water loss during potato frying with a compartmental dynamic model. J. Food Eng. 1999, 41, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, M.H.; Rice, P.; Selman, J.D. Relationship between oil uptake and moisture loss during frying of potato slices from c. v. record U.K. tubers. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 1987, 22, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsák, M.; Kotíková, Z.; Podhorecká, K.; Lachman, J.; Kasal, P. Acrylamide formation in red-, purple- and yellow-fleshed potatoes by frying and baking. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 110, 104529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanny, M.; Luning, P. Acrylamide in fried potato products. In Acrylamide in Food; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 161–183. ISBN 9780323991193. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Z.A.; Mohammed, N.K. Investigating influencing factors on acrylamide content in fried potatoes and mitigating measures: A review. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2024, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Bhattacharya, B.; Agarwal, T.; Paul, V.; Chakkaravarthi, S. Integrated approach towards acrylamide reduction in potato-based snacks: A critical review. Food Res. Int. 2022, 156, 111172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, A.; Bhattacharjee, P. Acrylamide mitigation and 2,4-decadienal elimination in potato-crisps using l-proline accompanied by modified processing conditions. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirit, B.; Canbay, H.S.; Gürsoy, O.; Yilmaz, Y. Vacuum impregnation pre-treatment: A novel method for incorporating mono- and divalent cations into potato strips to reduce the acrylamide formation in French fries. Open Chem 2023, 21, 20220279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerit, İ.; Demirkol, O. Application of thiol compounds to reduce acrylamide levels and increase antioxidant activity of French fries. LWT 2021, 143, 111165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahana Kabeer, S.; Mohamed Hatha, A.A. Effective processing strategies for minimizing acrylamide level in potato chips using l-asparaginase from Streptomyces koyangensis SK4. J. Food Process Eng. 2023, 46, e14459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Yadav, N. Inhibition of acrylamide and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural formation in French fries by additives in a model reaction. J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 45, e14178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Mackay, G.R.; Bain, H.; Griffith, D.W.; Allison, M.J. The processing potential of tubers of the cultivated potato, Solanum tuberosum L., after storage at low temperatures. 2. Sugar concentration. Potato Res. 1990, 33, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, G.; Anon, M.C. Influence of reducing sugars and amino acids in the color development of fried potatoes. J. Food Sci. 1986, 51, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abasi, S.; Minaei, S.; Jamshidi, B.; Fathi, D. Dedicated non-destructive devices for food quality measurement: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekramirad, N.; Adedeji, A. A review of non-destructive methods for detection of insect infestation in fruits and vegetables. Innov. Food Res. 2016, 2, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Magwaza, L.S.; Tesfay, S.Z. A Review of destructive and non-destructive methods for determining avocado fruit maturity. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2015, 8, 1995–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, P.D.C.; Hashim, N.; Shamsudin, R.; Nor, M.Z.M. Applications of imaging and spectroscopy techniques for non-destructive quality evaluation of potatoes and sweet potatoes: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 96, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Lizarazo, I.; Prieto, F.; Angulo-Morales, V. Assessment of potato late blight from UAV-based multispectral imagery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 184, 106061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Vijver, R.; Mertens, K.; Heungens, K.; Somers, B.; Nuyttens, D.; Borra-Serrano, I.; Lootens, P.; Roldán-Ruiz, I.; Vangeyte, J.; Saeys, W. In-field detection of Alternaria solani in potato crops using hyperspectral imaging. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 168, 105106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Hou, L. Potato late blight severity and epidemic period prediction based on Vis/NIR spectroscopy. Agriculture 2022, 12, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaswar, M.; Bustan, D.; Mouazen, A.M. Economic and environmental assessment of variable rate nitrogen application in potato by fusion of online visible and near infrared (Vis-NIR) and remote sensing data. Soil Syst. 2024, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Maestresalas, A.; Keresztes, J.C.; Goodarzi, M.; Arazuri, S.; Jarén, C.; Saeys, W. Non-destructive detection of blackspot in potatoes by Vis-NIR and SWIR hyperspectral imaging. Food Control 2016, 70, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Xu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Ning, X. Non-destructive detection of external defects in potatoes using hyperspectral imaging and machine learning. Agriculture 2025, 15, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

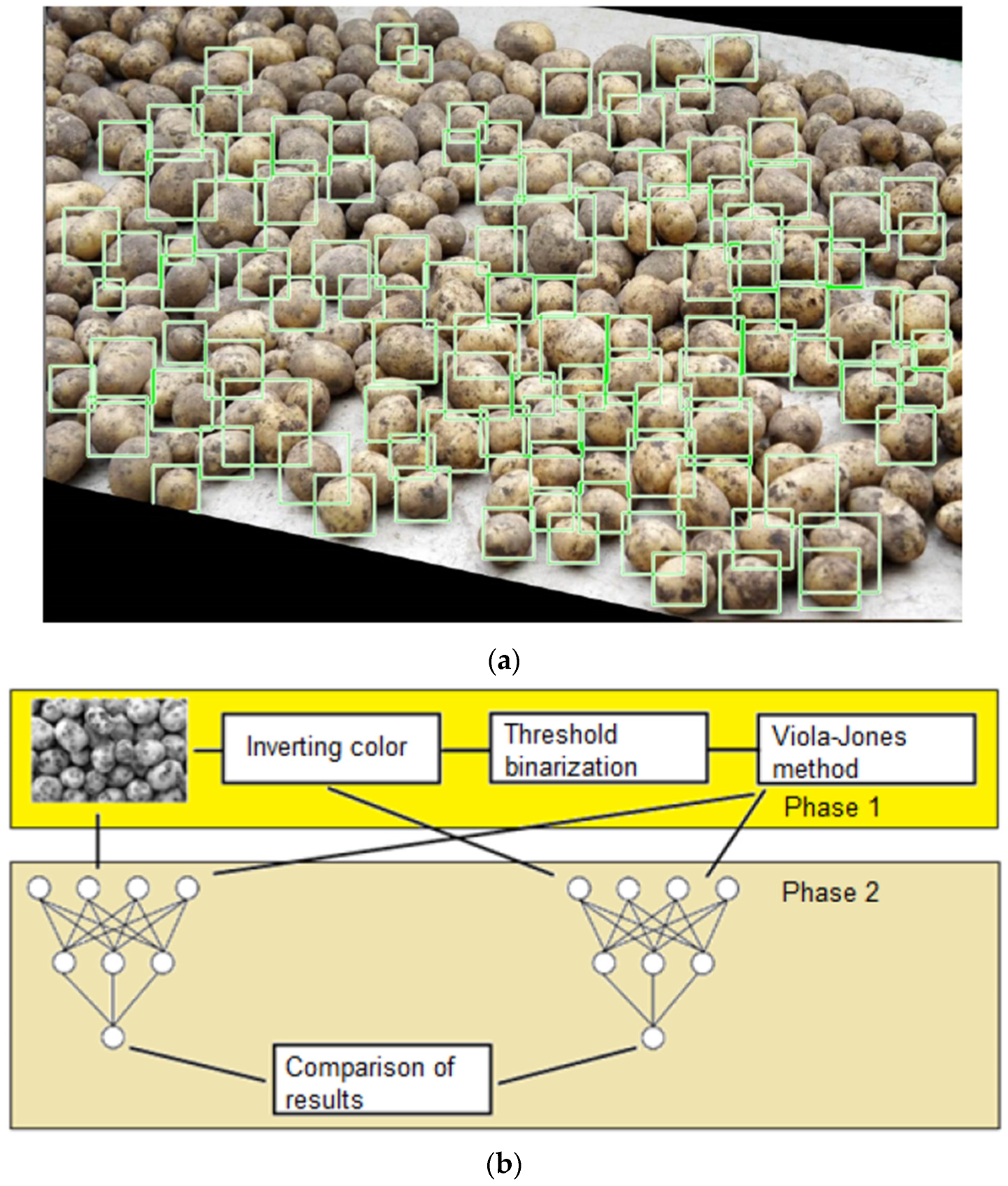

- Korchagin, S.A.; Gataullin, S.T.; Osipov, A.V.; Smirnov, M.V.; Suvorov, S.V.; Serdechnyi, D.V.; Bublikov, K.V. Development of an optimal algorithm for detecting damaged and diseased potato tubers moving along a conveyor belt using computer vision systems. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.-F.; Lv, C.-X.; Yuan, Y.-W.; Yang, B.-N.; Zhao, Q.-L.; Cao, Y.-F. Non-destructive detection of blackheart potatoes based on energy spectrum of VIS/NIR transmittance. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 8, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjær, A.; Nielsen, G.; Stærke, S.; Clausen, M.R.; Edelenbos, M.; Jørgensen, B. Detection of glycoalkaloids and chlorophyll in potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.) by hyperspectral imaging. Am. J. Potato Res. 2017, 94, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, S.; Singla, D.; Chowdhury, M.; Singh, C.B. A machine-learning-based prediction model for total glycoalkaloid accumulation in Yukon Gold potatoes. Foods 2025, 14, 3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, S.; An, H.S.; Hwang, I.G.; Choi, J.H.; Baek, M.W.; Choi, H.R.; Park, D.S.; Jeong, C.S. Prediction of α-solanine and α-chaconine in potato tubers from hunter colour values and VIS/NIR spectra. J. Food Qual. 2020, 2020, 8884219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, Q.; Rao, X.; Ying, Y. Precautionary analysis of sprouting potato eyes using hyperspectral imaging technology. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2018, 11, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rady, A.M.; Guyer, D.E.; Donis-González, I.R.; Kirk, W.; Watson, N.J. A comparison of different optical instruments and machine learning techniques to identify sprouting activity in potatoes during storage. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2020, 14, 3565–3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacal-Nieto, A.; Formella, A.; Carrión, P.; Vazquez-Fernandez, E.; Fernández-Delgado, M. Common scab detection on potatoes using an infrared hyperspectral imaging system. In Proceedings of the Image Analysis and Processing—ICIAP 2011, Ravenna, Italy, 14–16 September 2011; International Conference on Image Analysis and Processing; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (LNIP, Volume 6979). Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, E.W.; Amanah, H.Z.; Farras, I.; Pahlawan, M.F.R.; Masithoh, R.E. Vis/NIR reflectance spectroscopy for non-destructive diagnosis of Fusarium spp. infection in postharvest potato tubers (Solanum tuberosum). Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 8, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, E.W.; Amanah, H.Z.; Farras, I.; Pahlawan, M.F.R.; Masithoh, R.E. Detection of Fusarium spp. Infection in Potato (Solanum Tuberosum L.) during Postharvest Storage through Visible–near-Infrared and Shortwave–near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy. Open Agric. 2024, 9, 20220295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, F.; Chen, J. Research on potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) nitrogen nutrition diagnosis based on hyperspectral data. Agron. J. 2024, 116, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, Q.; Deng, W.; Wang, C. Detection of anthocyanins in potatoes using micro-hyperspectral images based on convolutional neural networks. Foods 2024, 13, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

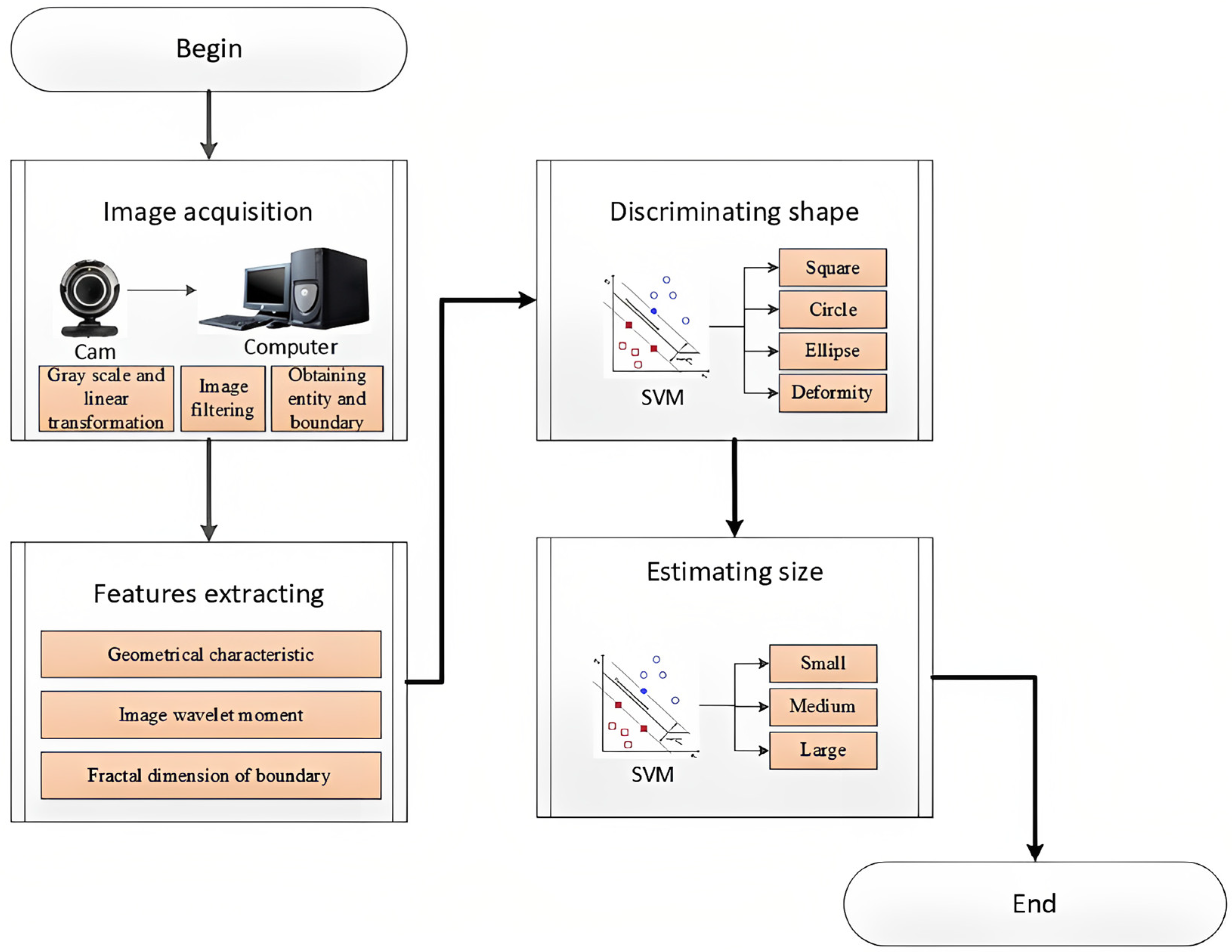

- Shen, D.; Zhang, S.; Ming, W.; He, W.; Zhang, G.; Xie, Z. Development of a new machine vision algorithm to estimate potato’s shape and size based on support vector machine. J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 45, e13974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peraza-Alemán, C.M.; López-Maestresalas, A.; Jarén, C.; Rubio-Padilla, N.; Arazuri, S. A systematized review on the applications of hyperspectral imaging for quality control of potatoes. Potato Res. 2024, 67, 1539–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y.; Han, M. Hyperspectral reflectance imaging for water content and firmness prediction of potatoes by optimum wavelengths. J. Consum. Prot. Food Saf. 2022, 17, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muruganantham, P.; Samrat, N.; Islam, N. Rapid estimation of moisture content in unpeeled potato tubers using hyperspectral imaging. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peraza-Aleman, C.; Arazuri, S.; Jarén, C.; de Galarreta, J.I.R.; Barandalla, L.; López-Maestresalas, A. Predicting the spatial distribution of reducing sugars using near-infrared hyperspectral imaging and chemometrics: A study in multiple potato genotypes. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rady, A.M.; Guyer, D.E.; Watson, N.J. Near-infrared spectroscopy and hyperspectral imaging for sugar content evaluation in potatoes over multiple growing seasons. Food Anal. Methods 2021, 14, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, C.; Song, S.; Xie, S.; Kang, F. Study on starch content detection and visualization of potato based on hyperspectral imaging. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 4420–4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Wang, C. Improved model for starch prediction in potato by the fusion of near-infrared spectral and textural data. Foods 2022, 11, 3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Chen, S. A transfer learning method for near infrared models of potato starch content and traceability from different origins. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 137, 106909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; He, Y.; Lv, C.; Chen, Y.; Lv, H. Online detection of dry matter in potatoes based on visible near-infrared transmission spectroscopy combined with 1D-CNN. Agriculture 2024, 14, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yan, J.; Tian, S.; Tian, H.; Xu, H. Vis/NIR model development and robustness in prediction of potato dry matter content with influence of cultivar and season. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 197, 112202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Domingo, M.Á.; Valero-Benito, E.M.; Hernández-Andrés, J. Multispectral and Hyperspectral Imaging. In Non-Invasive and Non-Destructive Methods for Food Integrity; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 175–201. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, W.; Jiang, Q.; Qi, W. Research progress in near-infrared spectroscopy for detecting the quality of potato crops. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2025, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease Category | Disease | Pre-Harvest/Post-Harvest Predominance | Pathogen | Transmission Mode | Affected Part and Symptom | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | Ring rot | Post-harvest | Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus | Cut seed Harvest Storage | Necrotic patches and wilt Tubers turn yellowish brown and crumbly | [49] |

| Brown rot | Pre-harvest | Ralstonia solanacearum | Roots | Dark brown to black lesions on leaves and stems tuber infections | [49,50,51] | |

| Soft Rot | Post-harvest | Pectobacterium | Tuber wounds Frost damage Harvest equipment | Tuber deterioration | [52] | |

| Common scab | Pre-harvest | Streptomyces species | Soil infections | Surface-scratched lesions | [57] | |

| Zebra Chips | Pre-harvest | Bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum (Lso) or Candidatus Liberibacter psyllaurous | Potato psyllid Bactericera cockerelli | Tuber darkening of the vascular tissue with necrotic flecking Stripping of the medullary ray tissues | [60] | |

| Fungal | Black dots | Post-harvest | Colletotrichum coccodes | Stems and roots | Brown necrotic spots Microsclerotia on the tuber exterior | [69] |

| Black scurf | Pre-harvest | Rhizoctonia solani | Soil and seed | Canker on the sprout, underground stem, and stolon tuber surface black (sclerotia) | [70,71,72,73] | |

| Dry rot | Post-harvest | Fusarium spp. | Damaged skin or wound Seed tuber | Tuber internal brown dry tuber | [74] | |

| Early blight | Pre-harvest | Alternaria solani | Stressed and injured plants Nutrient deficiency | Leaves, stems, and tubers | [75] | |

| Viral | Calico | Pre-harvest | Alfalfa mosaic virus (AMV) | Aphids | Internal tuber necrosis | [76] |

| Corky ringspot (CRS) | Pre-harvest | Tobacco rattle virus (TRV) | Root nematode (Paratrichodorus allies) | Necrotic arcs, rings, or patches in potato tubers | ||

| Potato latent mosaic | Pre-harvest | Potato virus X (PVX) | Mechanical | No symptoms or slight mosaic | [66,67] | |

| Potato mosaic | Pre-harvest | Potato virus Y (PVY) | Aphids | Range from no symptoms stunned plant, foliage damage plant death Tuber cracking | [66,67] | |

| Tuber necrosis/potato leafroll | Pre-harvest | Potato leaf roll virus (PLRV) | Aphids | leaf rolling immature plant unacceptable tubers | [66,67] |

| Disorder/Defect | Pre- and Post-Harvest Predominance | Causes | Affected Part | Symptoms | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black heart | Post-harvest (Storage) | Low oxygen environment Physiological stress | Tuber flesh | Discoloured internal tissue | [84] |

| Brown spot | Pre-harvest (Field stress) | Growing environments Low calcium in the soil Temperature | Tuber flesh | Rust-colored necrosis in parenchymal tissues | [88] |

| Hollow heart | Pre-harvest | Nutritional or moisture stress Tuber enlargement-tissue stress | Core of the potato tuber | Star-shaped hollow | [106] |

| Greening | Post-harvest (Mostly storage and retail) | Exposure to light Nitrogen concentration | Tuber periderm | Green-colored tuber surface | [96,107] |

| Sprouting | Post-harvest | Hormones Environment Physiological processes | Tuber physiology | Dormancy break Budding | [100] |

| Sugar ends | Worsened in post-harvest | Soil temperature, moisture deficit, and nitrogen fertilization (both insufficient or excess) Low storage temperatures | Tuber base | High sugar in the tuber’s base | [108] |

| Potato | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name of Constituent | Russet (Raw, Without Skin) | Gold (Raw, Without Skin) | Red (Raw, Without Skin) |

| Water (g) | 78.6 | 81.1 | 80.5 |

| Energy (kcal) | 83 | 73 | 76 |

| Protein (g) | 2.27 | 1.81 | 2.06 |

| Lipid (g) | 0.36 | 0.26 | 0.25 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 17.8 | 16 | 16.3 |

| Fiber-dietary (g) | 14.9 | 13.8 | 13.8 |

| Total sugars (g) | 0.53 | 0.65 | 0.66 |

| Calcium (mg) | 8 | 6 | 5 |

| Iron (mg) | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.39 |

| Potassium (mg) | 450 | 446 | 472 |

| Sodium (mg) | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 10.9 | 23.3 | 21.3 |

| Niacin (mg) | 1.5 | 1.58 | 1.48 |

| Thiamin (mg) | 0.074 | 0.051 | 0.066 |

| Vitamin B-6 (mg) | 0.157 | 0.145 | 0.144 |

| Phase | Target | Technique | Accuracy | Limitations and Future Study | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-harvesting (Field) | Variable rate nitrogen application | Online VIS-NIR and remote sensing | Significant reduction (50%) in nitrogen input and higher yield | Need to explore diverse sites and environments. | [167] |

| Prediction of late blight severity and epidemic period | VIS-NIR | Classification accuracies up to 99 and 95% for the methods adopted for late blight and 88.5% for the epidemic period | The interaction among late blight, temperature, and relative humidity requires further attention. | [166] | |

| Late blight detection | UAV-Multi imaging | Linear support vector and Random Forest, better performance and accuracy | Weeds’ influence on image background separation and detection accuracy | [164] | |

| Post-harvesting | Bruised detection | HSI and discrete wavelet transform | Detection accuracy 99.82% | Replacement of manual detection with such classification methods in a factory | [77] |

| Blackspot detection | VIS-NIR and SWIR imaging | Above 93% classification in the SWIR range | Validation on a larger sample size, diverse cultivars, regions and conditions before commercial application | [168] | |

| External defects | HSI and machine learning | 93, 93, and 83% accuracy for healthy, black/green, and scab/mechanical damage skin, respectively | Prediction accuracy enhancement is challenging for scab, mechanical damage and damaged skin | [169] | |

| Detection of disease and damaged potatoes on the moving conveyor | Computer machine vision | Detect and classify 100 potatoes per second with high accuracy | Different methods can be selected for classification | [170] | |

| Black heart detection | VIS-NIR transmittance | Faster and accurate online detection compared to absorbance | Generalization on diverse samples and conditions | [171] | |

| Glycoalkaloids and chlorophyll | HSI | Prediction accuracy for chlorophyll and glycoalkaloids was 0.92 and 0.21, respectively. | Limitations in total glycoalkaloids prediction | [172] | |

| Total glycoalkaloids | SWIR-HSI and machine learning | Best prediction model correlation coefficient of 0.72 | Extension of the model to multiple cultivars | [173] | |

| Total glycoalkaloids | VIS-NIR and Hunter colour variables | The regression coefficients of α-solanine and α-chaconine were 0.68 and 0.63, respectively. | Further work is required to improve the prediction. | [174] | |

| Sprouting (lateral/eye) detection | HSI | accuracy of 95.3% | More future work on apical sprouting | [175] | |

| Sprout detection | VIS-NIR interactance, VIS-NIR HSI, and NIR transmittance with machine learning | Highest accuracy 87.5% and 90% for sliced and whole, respectively, by HSI | Study on sprout inhibitor as a complementary aid to understand application timing | [176] | |

| Scab detection | HSI | Accuracy of 97.1% | Research on diverse cultivars with variations in skin colour and texture | [177] | |

| Seed potato Fusarium dry rot detection | VIS-NIR reflectance | Highest detection accuracy of 98.65% | Further study on the compositional status of the potato | [178] | |

| Fusarium dry rot detection | VIS-NIR and SWIR | SW–NIR is more effective | Can be applied to a potato internal quality study | [179] | |

| Anthocyanin | HSI-CNN | Coefficient of regression above 0.94 | Generalization on multiple varieties | [181] | |

| Shape and size | Machine vision system | 88.89% and 87.41% discrimination accuracy SVM polynomial kernel and linear kernel, respectively | High-quality camera and improved system design can be explored | [182] | |

| VIS-NIR and SWIR range HSI | Moisture content and firmness | VIS-NIR with the combination SG, CARS, and PLSR achieved the best model for moisture content and firmness | Multiple cultivars validation, as moisture content and firmness may vary across varieties | [184] | |

| HSI | Moisture content | Capability to assess the moisture content in unpeeled potato tubers | A larger sample and a more diverse range of cultivars | [185] | |

| NIR-HSI | Reducing sugar | Feasible for reducing sugar prediction across multiple cultivars | Studies on more potatoes for each cultivar and diverse seasons will be beneficial | [186] | |

| NIR-HSI | Glucose and sucrose | 95% and 80.1% classification accuracy for glucose and sucrose, respectively | It can be improved by studying more cultivars and seasons | [187] | |

| HSI | Starch | A correlation coefficient of 0.931 and, root-mean-square error of prediction of 0.763% were achieved | The study was conducted on sliced potatoes; therefore, the focus should be on a nondestructive way. | [190] | |

| VIS-NIR transmission with 1D-CNN | Dry matter | Highlighted the potential for dry matter determination | Further work with larger sample sizes, cultivars, and a wider range of dry matter levels is needed. | [191] | |

| VIS-NIR | Dry matter | Model combinations could effectively reduce biological variations and the external effects. | Work on real-time industry and online applications | [192] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Keithellakpam, L.B.; Karunakaran, C.; Singh, C.B.; Jayas, D.S.; Danielski, R. A Comprehensive Review on Pre- and Post-Harvest Perspectives of Potato Quality and Non-Destructive Assessment Approaches. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010190

Keithellakpam LB, Karunakaran C, Singh CB, Jayas DS, Danielski R. A Comprehensive Review on Pre- and Post-Harvest Perspectives of Potato Quality and Non-Destructive Assessment Approaches. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):190. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010190

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeithellakpam, Lakshmi Bala, Chithra Karunakaran, Chandra B. Singh, Digvir S. Jayas, and Renan Danielski. 2026. "A Comprehensive Review on Pre- and Post-Harvest Perspectives of Potato Quality and Non-Destructive Assessment Approaches" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010190

APA StyleKeithellakpam, L. B., Karunakaran, C., Singh, C. B., Jayas, D. S., & Danielski, R. (2026). A Comprehensive Review on Pre- and Post-Harvest Perspectives of Potato Quality and Non-Destructive Assessment Approaches. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010190