Featured Application

A new hybrid process for prototyping medium-size metal components with enhanced mechanical properties, especially within the framework of the nuclear industry.

Abstract

This work focuses on wire arc additive manufacturing for the rapid prototyping of shell-type parts such as sealed containers/capsules required in the manufacturing of metal components using hot isostatic pressing (HIP) of powder. The selected material was AISI 316L. The automatic generation step of robot trajectories from the CAD design of the part to be manufactured was addressed first. The mechanical and metallurgical properties of WAAM samples were then evaluated. Finally, a hollow cylindrical capsule manufactured by WAAM was used for the HIP sintering of powder to demonstrate the relevance of the hybrid technology. The main results are as follows: 1. The Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS) of AISI 316L WAAM samples was measured be-19 tween 540 MPa (longitudinal direction) and 600 MPa (transverse direction). 2. The as-manufactured WAAM parts present a residual (δ) ferrite content of 5–7%. 3. HIP processing permitted to reset a fully austenitic structure within the WAAM wall/shell. 4. The grain size was found to be coarser in the WAAM walls and finer in the core of the part (made of sintered powder). Finally, the suggested hybrid process may become an alternative technology for the manufacture of medium-size metal components in the nuclear industry.

1. Introduction

Hot isostatic pressing of powder is a promising technology for the future of prototyping large metal components. Expectations regarding the direct manufacturing of parts by hot isostatic pressing (HIP) of metal powder are particularly high, especially with regard to the design of new small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs), for which the technology might represent an alternative to casting and forging. It notably allows for the manufacturing of geometrically complex single-piece parts with a fine-grained microstructure. Depending on the process, a hollow shell-type preform (called a capsule) has to be manufactured first. This preform is then filled with metallic powder, followed by being vacuumed and sealed before the entire assembly is subjected to hot isostatic pressing. The HIP processing, which is carried out at up to 2000 bars and 2000 °C (or even more depending on the type of material), then results in the closure of all initially existing cavities/voids between the powder grains. Finally, the manufactured parts ultimately exhibit a relative density that can exceed 99.9%. Of course, the initial preform (capsule) must remain perfectly sealed and gastight throughout the sintering process. Otherwise, the gas pressure applied in the chamber would propagate inside the capsule, resulting in a low-quality sintering process that would be unable to close the voids between the powder grains. Until now, the gastight capsules required for the process have been manufactured using conventional welding mechanic processing (including multiple operations of cutting, stamping, and welding). These steps can be extremely time-consuming, depending on the geometrical complexity of the part to be manufactured. Hence, the cost of the conventional welding mechanic processing of the capsule, including its removal, may represent up to 45% of the final cost of an HIP part [1]. There is thus huge interest in simplifying the steps of manufacturing the capsule.

In this context, wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) technology has been developed as a specific process for manufacturing gastight containers (capsules). Indeed, WAAM has proved to be particularly suitable for printing large metal components. The WAAM shell printing technique is thus presented first in this work. Wire arc additive manufacturing has great potential for manufacturing blanks of large metal parts. It benefits from various advantages such as the absence of a closed chamber under inert gas and its high deposition rate (up to about 3 kg/h). On the other hand, the resolution of the manufactured parts is significantly lower in comparison with the laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) additive manufacturing process, for example (several-millimeter-wide cords/beads in WAAM versus around 50 µm for LPBF). It can therefore be used to produce rough parts quickly; these will then have to undergo surface finishing, particularly to eliminate large-scale waves on the external surface, which are inherent in the process. It can also be used to locally manufacture material additions on larger parts, thus simplifying the initial design of the part in question. At the present time, there are no fully integrated standard solutions provided by the manufacturers of welding tools, as is the case for LPBF; therefore, laboratories and companies generally carry out their own homemade developments, at the software level. However, some SMEs have recently specialized in the integration of virtual robotic cells, and automatic offline programming of robot trajectories for WAAM applications. Among these enterprises, ADAXIS may be cited for commercializing the ADAONE software. The first step of the present work was to develop a complete tool meeting our specifications, and adapted to our available equipment (KUKA KR6, KR8, and KR60 robots; FRONIUS Cold Metal Transfer (CMT) welding workstation). Throughout this work, the specific developments made (CAD slicer, automation of trajectories generation, deposition strategy, and examples of printed parts) are described first. The main objective was to quickly create a simple, easy-to-use, and effective solution for the manufacture of blanks with potentially complex geometries.

Many studies devoted to wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) are concerned with the characterization of the material properties, so that simple straight walls are often manufactured in this context. Horgar et al. [2] built aluminum alloy parts (AA5183, i.e., Al4.5MgMn alloy) and produced tensile specimens oriented differently regarding the aligned welds. In all cases, the Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS) of their samples was a little below 300 MPa, with maximum strains in the range of 22–29% depending on the sample’s orientation. Fuchs et al. [3] studied the machining allowance of Ti6Al4V near-net shaped WAAM parts in the context of the aeronautic industry. They developed a process chain that consisted of WAAM and milling, and their objective was to minimize the deviation between the WAAM part and the model. Rodrigues et al. [4] compared conventional GMAW WAAM and UC-WAAM (ultracold wire–arc additive manufacturing), in which the electric arc is established between the wire feedstock material and a non-consumable tungsten electrode. According to the authors, a potential advantage of UC-WAAM was that the layers can be deposited on a non-conductive material, which can allow for the production of overhang structures without any support; this advantage can be useful when manufacturing complex structures. Pizano et al. [5] applied HIP and heat treatment to Ni-based superalloy (HAYNES 282) parts manufactured by WAAM. HIP was found to reduce the porosity level to about 1%, facilitated the tailoring of the microstructure and improved the mechanical properties of the WAAM parts. Mclean et al. [6] used HIP to close pores and reduce the pore size in Al 2319 parts manufactured by WAAM. Experimentally, the volume of pores is reduced but the resulting pressure inside the pores is strongly increased after HIP. They further applied post-HIP heat treatment at atmospheric pressure, and showed that the overall porosity after post-HIP heat treatment is reduced by 95% in comparison with the initial porosity level in as-built specimens. Shiyas et al. [7] presented a review on the post-processing techniques of additively manufactured metal parts, intended to improve the surface finish, fatigue lifetime, and mechanical properties. Similarly, Motallebi et al. [8] performed a review on the post-processing heat treatment methods of lightweight magnesium fabricated by additive manufacturing. HIP may be useful to close pores especially in LPBF parts; in particular, HIP allowed a decrease in the pore level, from 3.4% in an as-built specimen to 0.7% after HIP treatment. However, depending on the application, other sintering processes can be interesting. For example, Teixera et al. [9] used two distinct sintering methods, and showed that microwave sintering was a good alternative to conventional sintering, to manufacture NiTi samples with controlled porosity level and pore sizes. In their study, microwave sintering was considered as very promising as it allowed for the formation of interesting intermetallic phases and homogeneous pores in a very short time. Hence, HIP is useful to improve the properties of AM parts [5,6,7,8], especially when pores must be closed. However, in the case of AISI 316L, the quasi-absence of porosity is achieved in the parts manufactured by WAAM. Gurcik and Kovanda [10] used a FANUC robot with offline programming to generate their trajectories. They illustrated the problem of trajectory defaults, as well as those of defects caused by the variation in the wire feeding speed. However, they finally manufactured quite simple parts (cylinders with a height of almost 60 mm) that could have been efficiently produced with a few lines of robot commands defining a circle by just three vertices, and including a repeating loop. Schmitz et al. [11] used multidirectional WAAM additive manufacturing (i.e., the possibility of building up layers in all directions) without providing concrete examples of part manufacturing. He et al. [12] recently discussed the architecture of an open-source software dedicated to the printing of parts by WAAM. They provided some details and showed a few parts manufactured with the suggested software/method, among which were several axisymmetric parts. Their robotic cell included two Yaskawa robots and a positioner. Baccomo et al. [13] suggested a method to analyze the influence of the kinematic of the robot on the WAAM process. They printed a sort of “tulip” part, observed some defects such as variation in the wall thickness, and suggested a method to investigate/explain the reasons of these defects.

In the present work, special interest was taken in the case of shell-type parts, for which concrete applications are more particularly expected, such as the manufacture of complex shape capsules for the hot isostatic pressing (HIP) of powder. Concerning this specific topic, Riehm et al. [14,15] combined additive manufacturing (LBPF) and hot isostatic pressing (HIP) to manufacture near net-shape composite components. In their study, LPBF was used to print the capsule, which was then filled with powder, and HIP was then applied to provide a dense solid part. In their study, they anticipated the distortion and shrinkage of the capsule due to HIP, and compensated by optimizing the capsule shape based on finite element modeling of the HIP process. Bieske et al. [16] developed (or used) a two-step manufacturing process of titanium–aluminide (TiAl) parts, which consisted of filling a gastight non-porous capsule with powder, with the whole being obtained by Electron Beam Powder Bed Fusion (EB-PBF). The produced parts were then treated by HIP to eliminate the pore content and provide dense parts. In the same vein, Farkoush et al. [17] also manufactured titanium–aluminide (TiAl) capsule specimens by EB-PBF. In their manufacturing process, the parts are initially composed of a porous core made of powder treated with low energy parameters, whereas the porous core is coated by a gastight 3 mm thick dense wall treated with higher energy parameters. Low energy parameters facilitate the avoidance of Al losses, which are detrimental to mechanical properties. HIP was then applied to obtain a full dense part, with a nearly 100% relative density. According to their results, after HIP, the parts manufactured with low energy parameters in the core exhibited much lower pore contents than the parts that contained non-treated powder in the core. Finally, their process allowed them to manufacture dense parts without any change in the Al content.

In the present work, the question of path planning in WAAM is discussed, as well as interfacing with the CAD of the part to print. In particular, the intersection between triangular faces described in an STL file, with a horizontal plane, results in a polygonal cross-section of the component along this plane. Depending on the part complexity, the result may either be a single polygonal line or multiple polygons separated from each other or imbricated one in the other (in the case of a hollow part). For a multidirectional slicing strategy, some parts of the geometry may be sliced in one direction, whereas some other parts are scanned in a different direction. Among the works cited by Schmitz et al., one can mention that of Ding et al. [18], which addressed the slicing of STL models for WAAM purposes. They showed a typical sequence of instructions in ASCII STL files created by software products such as CREO or FreeCAD. In their work, they subdivided the geometry into multiple volumes to allow them to apply different slicing directions depending on the considered subpart. In another article [19], Schmitz et al. used their method to print a simple elliptical half shell. Concerning welding, Fang et al. [20] used CAD data to define the path of the weld in the case of Y-type intersection of ducts. Venturini et al. [21] discussed the strategy for the manufacture of T-crossing features. Knezovic et al. showed several parts concerned with this strategy [22]. However, one can notice that the geometrical complexity is moderate for this type of part, since all deposited layers show the same shape, so that a loop can be used with a progressive upgrade/increase in the Z coordinate. The strategy consists of selecting the most adapted sequence of the alternating path. Ali et al. [23] studied the effect of different paths when manufacturing a flat part from juxtaposed welds. They showed that the resulting Von Mises stress and displacement fields differ depending on the selected scanning trajectories. Reisgen et al. [24] tested different cooling methods and showed their influence on the t8/5 time (i.e., the time it takes for the weld seam to cool from 800 °C down to 500 °C). The results were then correlated to the Vickers hardness. Finally, Rodrigues et al. [25] established the status and perspectives of WAAM in terms of processes (variants and declinations), in situ cooling, substrates’ preheating strategies, material types, deposition strategy, residual stresses, post heat treatments, and, of course, applications. It is worth mentioning that many studies presently draw about WAAM. For example, the WAAM topic in web of science regroups more than 3000 references, more than 300 per year from 2022, and more than 600 in 2024. For this reason, not all of them can be cited.

The aims of the first part of the present study may be summarized as follows:

- -

- Development of a slicer that can provide directly the robot program (sequence of instructions) in KRL format (case of KUKA robots) from the CAD design of the part to be printed;

- -

- Ilustration of the capabilities of the developed program (slicer/robot trajectories) through presentation of two examples, including the corresponding printed parts.

The next steps will be focused on the mechanical properties of flat samples cut in straight WAAM walls, and using a gastight cylindrical capsule filled of powder to obtain a dense solid part after HIP (the voids between the powder grains are closed during HIP treatment).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Slicing Software Development

As preliminary part of the work, an in-house offline programming (OLP) tool was first developed to generate automatically the command files of the robot/welder system from the CAD file of the part to print. Once this part has been designed and converted into STL format, the in-house slicer tool allows the automatic generation of the successive vertices defining the part contours and the corresponding robot trajectories. The automatic generation of the robot program is then performed including displacement instructions written in KRL (KUKA Robot Language), as well as commands related to starts and stops of the welding device. The different steps in the offline programming pre-treatment process are first described. Up to now, the case of shell-type parts has been considered, since they present several applications, especially in terms of the objective of parts’ weight reduction and the manufacture of powder containers for the HIP process. The objective of the present part of the work was thus to show the different steps of the OLP software (i.e., STL file, slicer, trajectories, and robot/welding device command files). The present solution is certainly very similar to that developed by Schmitz et al. between 2020 and 2021 [11,19]. The first step concerned the choice of CAD package used to import or draw the part. In this work, free and open-source software was used, and FreeCAD [26] was selected. It allows the use of solid modeling, functional modeling, and surface modeling. In addition, it allowed us to export the designed parts in ASCII STL files, which were quite easy to read with any programming language, such as C.

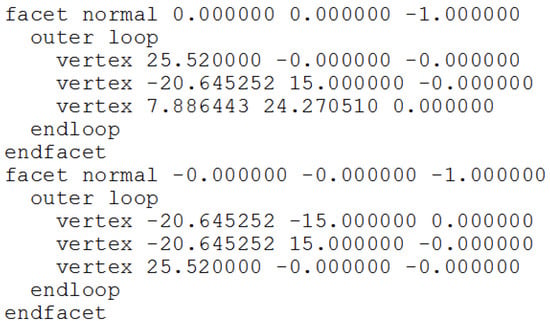

Figure 1 shows a typical list of definition instructions within an ASCII STL file. All triangular faces are defined individually from the Cartesian coordinates of three vertices. It is thus easy to read such a file and to define the three edges connecting the vertices. In principle, only one other face is connected to each edge (i.e., only two faces share a common edge). It is also easy to calculate the coordinates of the two vertices defining the intersection with a horizontal plane (if it exists). Finally, the intersection of a horizontal plane with a solid defined in a STL file consists of connected edges forming at least one closed polygon (and possibly several ones).

Figure 1.

Typical list of definition instructions within an ASCII STL file.

It is thus possible to define the different polygons corresponding to the intersection of solids defined in the STL file, with a series of slices (for example, a series of Z altitudes). Finally, it is the role of the slicer to do this work, and to provide the different polygons through a series of successive vertices. In a second step, it is possible to convert the series of vertices into a series of KRL instructions [27] defining the contour of the part and the robot trajectories (in the case of a KUKA robot). In addition, it is possible to add instructions for arc ignition (start of a polygon) and arc extinction (end of a polygon). The connection between two successive polygons may be defined by an additional straight line, and the corresponding displacement instruction may be added; during this connection, the arc of the welder is off. In the present state of development, the proposed technique is thus able to print the contours of the part designed with the CAD software package, which is perfectly suitable for the rapid manufacturing of powder containers (capsules) for the hot isostatic pressing (HIP) of powder. A new HIP facility was just installed in Le Creusot in 2025, with a maximum heating temperature of 1400 °C and a maximum isostatic pressure of 200 MPa. This machine, financed in the frame of EQUIPEX+ ANR-21-ESRE-0039, will allow for the manufacture of parts with a diameter as large as 0.420 m and a height of 1 m, which corresponds to an intermediate scale for the nuclear industry.

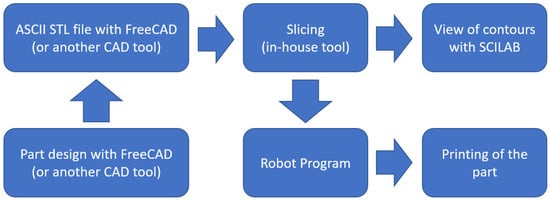

The different preprocessing steps to derive the robot program in KRL format (in the case of a Kuka robot) from the CAD design of the part are summarized in a flowchart (Figure 2). The FreeCAD software is used to provide an ASCII STL file of the considered part. The in-house tool provides slices that can be viewed with SCILAB software. In the second step, the in-house tool generates the robot program from edges defined by slicing. This robot program also contains commands to stop and start the welding process managed by the FRONIUS device.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the successive steps, including the use of free software products.

2.2. WAAM Cell and Deposition Parameters

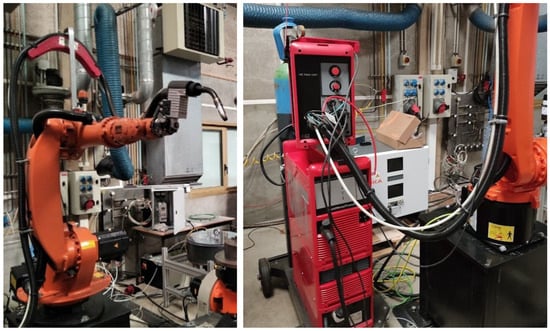

The test/printing rig used for the experiments was composed of a six-axis KUKA KR6 robot carrying a CMT welding torch associated with a CMT ADVANCED source from FRONIUS, within an open cell (roof), and equipped with gas/vapor extraction devices. Figure 3 shows the KR6 robot (left) and the FRONIUS source with the wire dispenser on its top (right). The parts were printed on a one-meter-high steel table, where the ground connector clamp of the welding source was fixed. All parts were manufactured with AISI 316L stainless steel (on thick supporting plates made of 316L too). The filler wire had a diameter of 0.8 mm.

Figure 3.

Photographs of the six-axis KUKA KR6 robot (controller KR C2) carrying the CMT torch (left), and of the CMT ADVANCED FRONIUS source, with the root of the new KUKA KR8 robot (controller KR C5) (used from February 2023) (right).

The retained deposition parameters are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Deposition parameters.

2.3. Characterization Techniques

2.3.1. Ferrite Content Analysis

A ferrite meter (MF300F-P10 model from SOFRANEL) was used to estimate the ferrite contents in the WAAM parts. All the measurements were taken after machining, and especially after the preparation of the tensile specimens.

2.3.2. Mechanical Testing

The tensile specimens were manufactured in straight WAAM walls. The milling of the wall faces was performed first, and wire electric discharge machining (EDM) was then used to cut the specimens. The total length of each specimen was 120 mm, whereas their useful length was 60 mm, which allowed an extensometer to be placed. Tensile tests were performed with an MTS machine.

2.4. Hot Isostatic Pressing of Powder with a WAAM Capsule

The HIP of powder with the WAAM capsule was performed with a QIH 15L press from QUINTUS. This HIP press integrates an intermediate-sized chamber (186 mm in diameter and 500 mm in height), and may reach a maximal temperature level of 2000 °C and a pressure of 200 MPa. From 2025, a new HIP facility (QUINTUS QIH 60-URC2) has been available. This new device was purchased in the frame of the CALHIPSO EQUIPEX+ program ANR-21-ESRE-0039 and integrates a larger chamber (1 m in height and 420 mm in diameter).

The HIP sintering operations comprised the following steps:

- -

- Filling the AISI 316L capsule with AISI 316L powder on a vibrating plate;

- -

- Positioning a filter (to avoid suction of the powder);

- -

- Vacuum draw, and heating at 300 °C;

- -

- Pinching the filling tube, and welding;

- -

- HIP sintering with the following parameters:

- -

- Two cycles of vacuum draw/argon filling of the chamber.

- -

- Pressurization at 10 MPa.

- -

- Heating up to 1200 °C, 102 MPa, with two speeds (10 °C/min, and then 5).

- -

- 4h sintering at 1200 °C/102 MPa.

- -

- Natural cooling, and decompression from 150 °C.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Slicing Results and Typical Structure of the Robot Programs

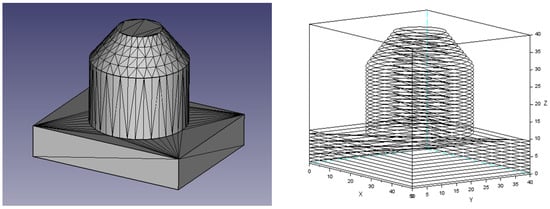

Figure 4 shows a concrete example for the case of a simple part composed of a brick, a cylinder, and a conical part. The STL mesh generated by FreeCAD is shown on the left, and the corresponding slices are shown on the right (plot of the successive lines with SCILAB [28], including connecting lines between successive slices). Even if all slice contours look like circles in the top part, these circles are made of straight edges, forming closed polygons. In the present case, the different slices are formed by a little more than 2200 straight edges.

Figure 4.

Simple CAD part viewed in FreeCAD (left) and corresponding slices viewed with SCILAB (right), including connecting lines, allowing us to start the next layer on the opposite side of the part.

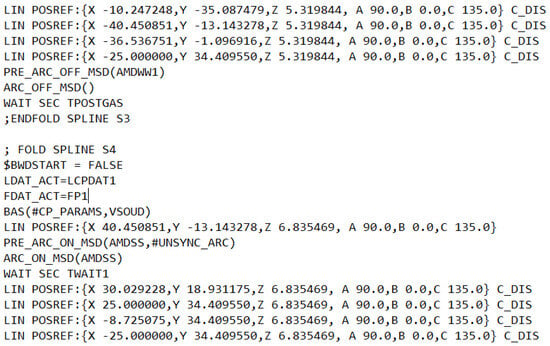

Figure 5 shows a typical sequence of instructions in a KRL src file (in the case of a KUKA robot) automatically generated by the OLP tool. The part that is shown is just between two successive polygons. First, each displacement between successive points of a polygon is achieved with a LIN command that displaces the TCP (Tool Center Point) linearly from the current position to the specified point. In the example, POSREF represents a reference position, corresponding to the origin position of the part in the CAD model, which will be located on the welding table. In addition, the C_DIS option of LIN commands avoids stops at each intermediate point (with subsequent slowdown), and permits the continuous displacing with the specified speed. When the contour of a polygon is finished, the arc is switched off and the welder displacement is stopped at the last point during a time lapse of a few seconds (during which the gas of the welding device contributes to cooling down the part). Then, the welder moves linearly from the current position to the first point of the next polygon, the arc is then ignited again, and the welder moves linearly to successive points of the next polygon. Finally, the suppression of short edges along the polygons is not required but may just allow for a decreasing number of points and size of files. One may remark that the three angles defining the tool orientation at each point are kept unchanged, meaning that the welding device remains vertically aligned; this choice allows for the avoidance of strong accelerations where the skeleton of the part shows directional changes. However, it is desired (in the near future) to follow the wall’s orientation for some types of parts, and especially for parts presenting smooth variations in the curvature without any abrupt directional changes.

Figure 5.

Typical sequence of instructions in a KRL src file automatically generated from successive slices (i.e., polygons such as those shown in Figure 2), and including arc ignition/extinction commands, as well as waiting instructions.

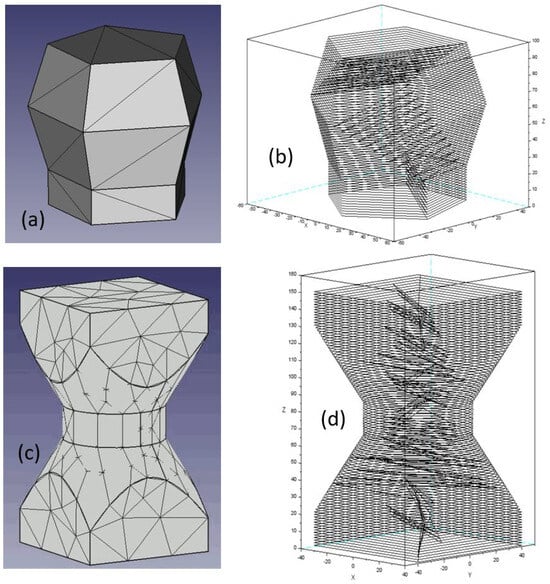

Figure 6 shows the design of two parts manufactured with the slicer method. The first one (Figure 6a) consists of a part with a regular pentagon basis (5 × 50 mm edges at the bottom; 5 × 108° between five successive edges). The total height of the part is 97 mm: the bottom part is 21 mm + 2 × 38 mm in the upper part. In addition, the dimension of the five edges at the largest section is 63.5 mm. The left picture (Figure 6a) shows the simplest STL file that can be generated in the present case: each quadrangle is split in two triangles, whereas the bottom and top pentagons are split with three triangles, resulting in a total number of 36 triangular faces (i.e., 15 × 2 + 2 × 3). The slicing of this part with horizontal planes results in a series of polygons composed of ten edges, with one intermediate vertex along each straight edge of the pentagon (Figure 6b). The second part (Figure 6c) consists of a double square to circular transition part (i.e., square to circular transition, followed by a circular to square transition). The dimensions of the bottom and top square sections are 80 × 80 mm, whereas the diameter of the circular part at mid height is 60 mm. The total height of the part is 150 mm. This part is thus much more complex, including nonplanar curved surfaces. The resulting robot trajectories (Figure 6d) include connecting edges between successive slices: these edges are used to alternate the successive positions of the starting point for each weld bead. The resulting number of vertices, edges, and displacement instructions in the robot file is as high as 7155 for this example.

Figure 6.

Design of parts manufactured by WAAM (a,c), and corresponding robot trajectories provided by the slicer software (b,d).

Direct in situ coding of the robot program required to print these two parts would be complex for the top one (Figure 6a,b), and almost impossible for the bottom one (Figure 6c,d). In contrast, the OLP tool generates the corresponding list of instructions in less than one second, once the STL file is produced. With that tool, there are only few parameters to adjust, such as the height of slicing (Z distance between successive slices). In addition, the another advantage relates to the reliability of the process: the generated list of instructions is always free of bugs once the program has been tested and validated. Once back on the real robot cell, only the POSREF position must be defined by the in situ learning of the printing position on the welding table. The corresponding robot trajectories (Figure 6b,d) are herein viewed with SCILAB software and include the connecting lines between successive slices (starting at the opposite side for two successive slices). The starting point of each slice is always one of the vertices along the trajectory (i.e., one of the ten vertices defining each pentagon for the first part, or more for the second one). For the first part, it may thus either be one of the pentagon corners, or the single intermediate point on each straight edge of the pentagon. These points are thus often aligned or regularly staggered. To avoid this, a simple strategy can be implemented, consisting of increasing the number of triangles in the STL file; for example, by forcing a maximum edge length of 10 or 20 mm for triangles. By doing so, the more points there are along a slice/contour, the lower the probability that the starting point (where the arc ignition takes place) will be regularly aligned regarding the previous layers.

3.2. Wire Arc Additive Manufacuring of Capsules

The deposition parameters shown in Table 1 were used to print these parts. When neglecting material losses, the expected value of the cross-section of individual weld beads may be estimated from the following:

Considering an average wall width of 6 mm, the expected height of each weld bead is thus 1.4 mm. Experimentally, this value was effectively observed when applying a short waiting time between successive welds/layers. Specifically, the part temperature remains high during the deposition process, and the beads are large. When a higher waiting time was applied (typically 10 s or more), the part cooling was increased, and the average height of each deposited bead was about 1.5 mm, corresponding to the retained slicing distance. This value is not so different from the expected one, and the weak difference is certainly related to a small overestimation of the average thickness of the wall, which has dips and bumps.

3.2.1. Printing of Complex Shape Capsules with the Slicing Method

The printing of the two parts of Figure 6 was thus considered with the parameter set of Table 1. The objective was to show the feasibility of the automated manufacturing process.

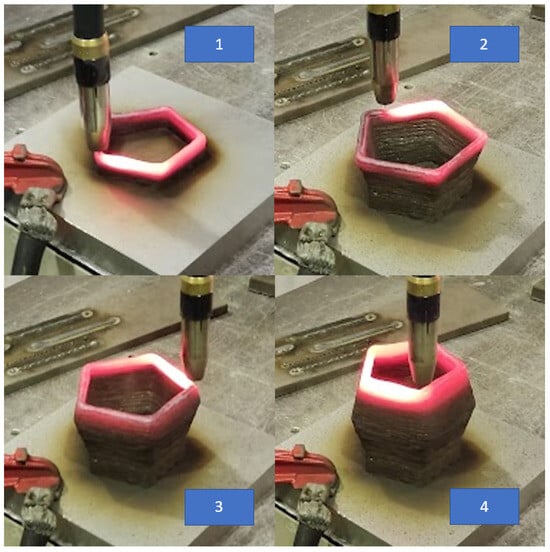

The first part is shown at different steps during the WAAM printing process (Figure 7). The part was manufactured by applying an alternative direction strategy:

Figure 7.

View of the part at four different steps during the manufacturing process (1–3 clockwise rotating direction; 2–4 counterclockwise direction).

- -

- The starting point of a polygon at the opposite side to the previous one;

- -

- The inversion of the rotation direction for each layer.

Specifically, the weld gun turned clockwise for subfigures 1 and 3 of Figure 7 (left), and in the counterclockwise direction for subfigures 2 and 4 (right).

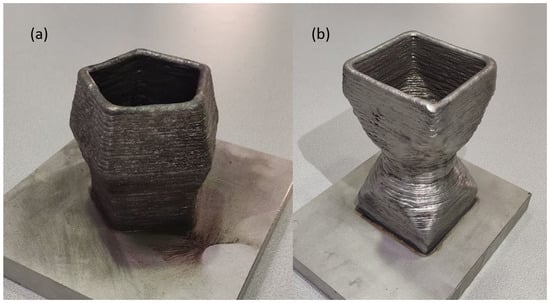

The corresponding printed parts are shown on Figure 8. The part of Figure 8b was brushed more efficiently. Depending on the application, only functional faces could be machined at this step, whereas some other faces could remain as raw. If all surfaces must be machined, the existing CAD file of the part could be used to perform the corresponding machining using a CNC machining center. The potential applications of this technology are numerous. One of them relates to the rapid fabrication of complex shape capsules for the hot isostatic pressing technology of powder. Consequently, the hollow WAAM part could be closed with a plate (for this example), and then filled with powder to provide a solid part after HIP.

Up to now, one of the remaining challenges has concerned the accuracy of the thickness of each layer, in relation to initial expectations. For the first case exposed, the total height of the first printed part was slightly lower in comparison with that which was initially expected (i.e., about 95 mm instead of 97 mm in the CAD model). A lengthening of the waiting time between layers allowed us to correct this small mismatch in a second step (i.e., second printing of the same part). However, it would be preferable to avoid iterative printing. One idea to meet this challenge consists of the implementation of an online control system for the deposited thickness of each layer, or at least an online control system for the parts’ height during the deposition process, not necessary at each layer. Specifically, the robot program could be slightly modified, in order to allow repeating several times a layer if required (i.e., if the part height after a given layer is lower than the expected one). Another subsequent default correlated to the same reason is the progressive increase in the stick-out (i.e., the distance between the contact tip and the part) if the deposited thickness becomes lower than the expected one; this drawback would also be offset by the online control of the part height. However, some other complementary experiments showed that the thickness of the deposited weld bead is dependent on the sublayer material’s temperature (i.e., the bead thickness decreases somewhat if the sublayer temperature is too high). The first step before any control of the part height is thus the in situ control of the part temperature; the idea could thus be to automatically adjust the waiting time between the manufacture of successive weld beads in order keep the part temperature unchanged during the whole manufacturing process.

3.2.2. Printing of Simple Cylindrical Capsules with Direct Programming (No Slicing)

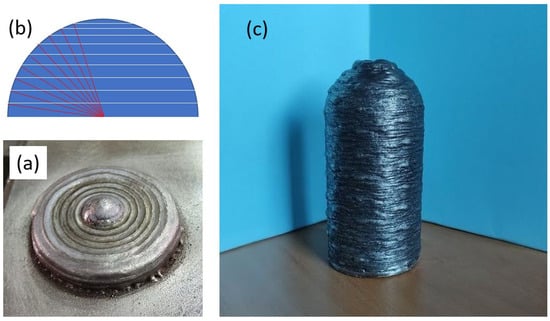

A different printing strategy was considered while printing capsules such as like-cylinder ones. For printing the solid bottom, the best results were obtained by superposing several layers formed by a spiral-type robot path (Figure 9a). This may be achieved by programming a parametric function of the following type:

in which the value of must be calculated to provide an accurate distance between juxtaposed beads, and parameter ranges between 0 (or a higher value) and , in which n is the required number of rounds depending on the diameter of the part/cylinder. When printing the cylindrical part, the starting point of each cylindrical layer/bead must be shifted to avoid the superposition of defaults. In the present case, the corresponding predefined shift angles were set in an array. For printing the half-spherical top, a progressive slicing refinement must be implemented, such as is illustrated in Figure 9b. Finally, the resulting capsule is shown in Figure 9c.

Figure 9.

Printing of the bottom with a spiral path (a), the strategy of slicing refinement for printing the half-sphere dome (b), and the resulting cylindrical capsule for HIP testing (c).

3.3. Characterization of Materials’ Properties

3.3.1. Microstructure and Ferrite Content of WAAM Samples

Simple experiments showed that the printed parts (Figure 8) are weakly magnetic, which confirmed that the superposed welds are not composed exclusively of austenitic γ-phase.

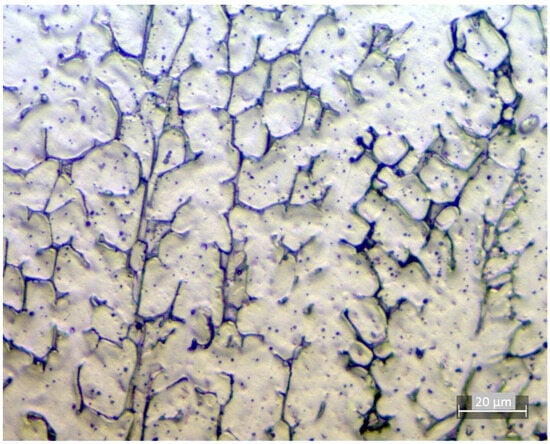

Specifically, the δ-ferrite phase can form at high temperatures and probably appeared during the manufacturing process. This phase may decrease the risk of hot cracking if its content is lower than 8%. However, it can be detrimental to corrosion resistance if its content becomes higher than 10%. According to the Schaeffler diagram [29], the ferrite content of AISI 316L steel after solidification and cooling should be about 5%. The typical microstructure of the AISI 316L samples manufactured by WAAM with the parameters provided in Table 1 is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Typical microstructure of an AISI 316L part manufactured by WAAM.

The main phase is the austenitic γ-phase. However, a skeleton composed of δ-ferrite is also clearly observed. The ferrite content was measured in the range 5–7%, and varies only slightly with the position (i.e., top or bottom of a part).

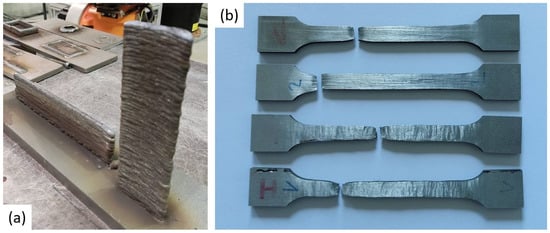

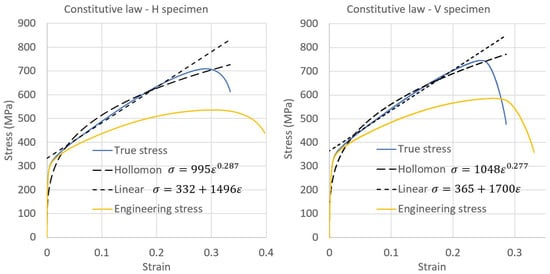

3.3.2. Mechanical Properties of WAAM Parts

Once the printing method has been described and validated, showing the potential of the WAAM technology for the manufacture of complex shape hollow parts, the mechanical properties of materials manufactured with this method were evaluated. Straight walls were first manufactured (Figure 11a) with the objective of evaluating the mechanical properties in both the longitudinal/horizontal and transverse/vertical directions. These walls were then machined (milling of faces first), and the tensile specimens were then cut by wire electric discharge machining. The corresponding specimens after tensile tests are shown in Figure 11b. The Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS) was measured at 540 MPa for samples manufactured along the horizontal direction (Figure 12 left), and 585 MPa for samples manufactured along the vertical direction (Figure 12 right). In addition, the maximum engineering strain was 40% for the horizontal samples (Figure 11b, bottom), and 34% for the vertical ones (Figure 11b, top). In all cases, ductile behavior was observed. The true stress curves are also reported on the figures, as well as different-type fitting curves: the true stress–strain curves take the striction of the specimens into account. If stands for the engineering stress and for the true stress, then and in which . The true stress/strain curves were used to derive some constitutive behavior law of the as-deposited material assuming two different models:

Figure 11.

(a) Straight walls manufactured by WAAM to cut tensile specimen in the horizontal and vertical directions, and (b) corresponding samples after tensile tests (top; two vertical specimens/bottom and two horizontal specimens).

Figure 12.

Tensile tests’ loading curves in both horizontal (left) and vertical (right) directions, and engineering stress (orange color), and true stress (blue color), with the corresponding Hollomon and bilinear fitting curves.

- -

- A bilinear model with a Yield stress, and tangent modulus;

- -

- The Hollomon law, commonly used to predict the strain hardening behavior.

According to the results, the as-built WAAM material was found to be slightly anisotropic. Specifically, the tangent modulus derived for the horizontal direction is 1.5 GPa (i.e., slope of 1496 MPa as derived from the corresponding linear interpolation curve plotted in Figure 12, left) considering a strain range of [0.01…0.25], whereas the tangent modulus is about 1.7 GPa for the vertical direction. In addition, since the elastic curve is almost vertical in this type of graph, the value of 332 MPa reported for the ordinate origin in the linear interpolation (H direction) may be considered as the Yield stress (334 MPa considering the intersection point of the elastic and plastic curves, assuming for the elastic domain). Again, the ordinate origin is somewhat higher for the vertical direction (365 MPa against 332), corresponding to a Yield stress of 368 MPa.

Considering a Young modulus of 200 GPa, the ratio is thus about 0.75% for the horizontal direction, and 0.85% for the vertical direction.

Concerning the Hollomon law (power law), the best fit was obtained with (strain range [0.05…0.3]) for the horizontal direction, and (strain range [0.05…0.24]) for the vertical one.

Table 2 summarizes the main mechanical properties measured from the tensile tests. The higher UTS (and Yield stress) for the vertical direction attests for the perfect metallurgical continuity and subsequent excellent cohesion between successive layers/beads. A possible explanation is that the grains are more elongated in the vertical direction, which is the preferred cooling and solidification direction, and thus the preferred orientation of grains. For this reason, the number of grain boundaries along the specimen length could be higher for the horizontal direction, giving rise to a higher maximum strain and lower UTS. As observed in Figure 11b, bottom, the horizontal specimens show streaks across the vertical direction after the tensile tests.

Table 2.

Summary of mechanical properties measured for both the horizontal and vertical directions/samples.

In all cases, the results derived for the two different behavior laws will be useful to simulate the deposition/welding process with an FEM package.

3.4. HIP of Powder with a Capsule Manufacured by WAAM

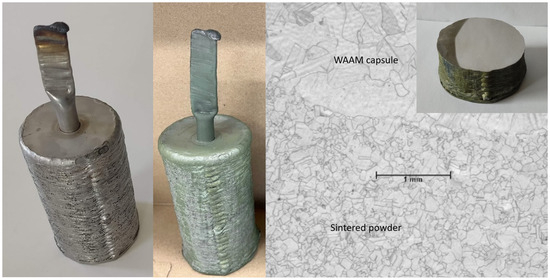

First, experiments validating the new hybrid WAAM/HIP manufacturing process for the prototyping of a solid part from a hollow WAAM capsule were performed. The case of a cylindrical part was considered for these first experiments. A two-step process was used to manufacture the WAAM cylinder, printing a flat bottom first, and printing the cylinder just after. An AISI 316L cover, including a cylindrical tube (for powder filling), was then welded onto the WAAM capsule (Figure 13). The part was then filled with AISI 316L powder (i.e., the same material as the WAAM capsule) on a vibrating plate, to densify the powder. The HIP processing parameters are summarized in Section 2.4. HIP treatment allowed all the voids between the powder grains to be closed, thus providing a solid part with smaller dimensions. A sectioning of the part was then performed after HIP processing, and the surface was then prepared/polished before chemical etching with Kalling reagent was performed, to reveal the granular microstructure. The results showed perfect continuity from the WAAM capsule to the sintered powder, with a finer microstructure in the core of the sample (sintered powder). According to the Hall–Petch relationship, this fineness of grains is favorable to achieve high mechanical properties.

Figure 13.

As-built cylindrical capsule manufactured by WAAM, filled with powder, and sealed (left); corresponding part after HIP treatment (middle); view of the grains after cutting a slice, surface polishing, and chemical etching (right); and polished surface of a complete slice (top right corner).

4. Conclusions

The first aim of the present study was to develop a slicer able to provide the printing robot program from the STL file of the CAD part to be printed, and to illustrate the capacities of the corresponding in-house OLP (offline programming) tool, through several examples. The methods that provided directly the list of instructions for the robot program required to manufacture a part by WAAM, from the CAD file of the corresponding part in STL format, were first described. The functionalities of this tool are certainly very similar to those of the tool developed by Schmitz in 2020–2021 [11,19]. Nevertheless, additional information, advice, and examples were provided. The present tool produces very clean files and always applies the same method, which reinforces the robustness and interest of the method. The case of a deposition process managed by a KUKA robot was considered, so that the OLP tool provides a suitable list of instructions in KRL format. Of course, all robot manufacturers have their own input language. However, they often all have the same functionalities, so it is highly probable that one will find corresponding instructions for each robot manufacturer. It is thus highly probable that the present tool could be used to generate programs for several robot manufacturers, including only small changes (i.e., probably only the export function would have to be changed). The case of shell-type parts was considered in the present work, since it already is of particular interest, especially for the printing of large powder containers for the HIP sintering process. The mechanical properties of the samples were evaluated and the exceptional cohesion between successive beads in WAAM parts was confirmed. Finally, a new hybrid WAAM/HIP process was developed, involving using WAAM to manufacture a gastight capsule and applying HIP to provide the corresponding solid part from the capsule filled with powder.

Supplementary Materials

A video of the manufacturing of one layer of the first part is available at https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7057308642076700672/, accessed on 10 October 2025. This video was recorded using an advanced visualization technology including pulsed lighting with a laser diode from CAVITAR Ltd. (500 W peak power, infrared domain at a wavelength of 810 nm), and using a synchronized Phantom camera from AMETEK. The arc plasma emits only slightly at this range of wavelength so that images are not saturated. One may thus clearly observe the molten pool at the rear of the arc region.

Author Contributions

R.B. and A.M. contributed equally to the development of the automatic robot trajectories generation tool, to the manufacturing of the parts, and to the redaction of the article. H.A. did a post doctorate in the frame of the project, and contributed to the characterization of the HIP part. M.-A.K. joined the team as part of his master’s internship, and was in charge of FEM modeling. F.B. was in charge of HIP operations. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the EIPHI Graduate School (Grant number ANR 17-EURE-0002) and Bourgogne-Franche-Comté Region. The HIP facility was funded by ANR EQUIPEX+, grant number ANR-21-ESRE-0039.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WAAM | Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing |

| HIP | Hot Isostatic Pressing |

| UTS | Ultimate Tensile Strength |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| SMR | Small Modular Reactor |

| LPBF | Laser Powder Bed Fusion |

| EB-PBF | Electron Beam Powder Bed Fusion |

| CMT | Cold Metal Transfer |

| SMEs | Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises |

| GMAW | Gas Metal Arc Welding |

| OLP | Offline Programming |

| STL | Standard Triangle (or Tesselation) Language |

| KRL | KUKA Robot Language |

| TCP | Tool Center Point |

References

- Bernard, F.; Château-Cornu, J.-P.; Bolot, R.; Mathieu, A.; Lamesle, P.; Frayssines, P.-É.; Lemarquis, L. Une application thermo-industrielle du futur au Creusot «Métallurgie des Poudres et Compression Isostatique à Chaud»: La plateforme EquipeX+/CALHIPSO. In Chaleur, Énergie, Thermodynamique, Le Message de Carnot Aujourd’hui… 200 Ans Après; Ed Éditions Universitaires de Dijon: Dijon Cedex, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Horgar, A.; Fostervoll, H.; Nyhus, B.; Ren, X.; Eriksson, M.; Akselsen, O.M. Additive manufacturing using WAAM with AA5183 wire. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 259, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.; Baier, D.; Semm, T.; Zaeh, M.F. Determining the machining allowance for WAAM parts. Prod. Eng. 2020, 14, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.A.; Duarte, V.R.; Miranda, R.M.; Santos, T.G.; Oliveira, J.P. Ultracold-Wire and arc additive manufacturing (UC-WAAM). J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2021, 296, 117196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizano, L.F.L.; Sridar, S.; De Vecchis, R.R.; Wang, X.; Biddlecom, J.; Pataky, G.J.; Sudbrack, C.; Xiong, W. Recrystallization behavior and mechanical properties of Haynes 282 fabricated by wire-arc additive manufacturing with post-heat treatment. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 119, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclean, N.; Bermingham, M.J.; Colegrove, P.; Sales, A.; Soro, N.; Ng, C.H.; Dargusch, M.S. Effect of Hot Isostatic Pressing and heat treatments on porosity of Wire Arc Additive Manufactured Al 2319. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 310, 117769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiyas, K.A.; Ramanujam, R. A review on post processing techniques of additively manufactured metal parts for improving the material properties. Mater. Today-Proc. 2021, 46, 1429–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motallebi, R.; Savaedi, Z.; Mirzadeh, H. Post-processing heat treatment of lightweight magnesium alloys fabricated by additive manufacturing: A review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 1873–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, R.D.S.; Oliveira, R.V.D.; Rodrigues, P.F.; Mascarenhas, J.; Neves, F.C.F.P.; Paula, A.D.S. Microwave versus Conventional Sintering of NiTi Alloys Processed by Mechanical Alloying. Materials 2022, 15, 5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurčík, T.; Kovanda, K. Waam technology optimized by off-line 3d robot simulation. Acta Polytech. 2019, 59, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, M.; Wiartalla, J.; Gelfgren, M.; Mann, S.; Corves, B.; Hüsing, M. A Robot-Centered Path-Planning Algorithm for Multidirectional Additive Manufacturing for WAAM Processes and Pure Object Manipulation. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.L.; Lu, C.L.; Ren, J.H.; Dhar, J.; Saunders, G.; Wason, J.; Samuel, J.; Julius, A.; Wen, J.T. Open-source software architecture for multi-robot Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM). Appl. Eng. Sci. 2025, 22, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccomo, A.; Chanal, H.; Duc, E.; Limousin, M. A method for analyzing the kinematic influence of a robot on the WAAM process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 136, 4239–4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riehm, S.; Kaletsch, A.; Broeckmann, C.; Friederici, V.; Wieland, S.; Petzoldt, F. Tailor-Made Net-Shape Composite Components by Combining Additive Manufacturing and Hot Isostatic Pressing. In Hot Isostatic Pressing: Hip’17 (Materials Research Proceedings); Materials Research Forum LLC: Millersville, PA, USA, 2019; Volume 10, pp. 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Riehm, S.; Friederici, V.; Wiel, S.; Deng, Y.; Herzog, S.; Kaletsch, A.; Broeckmann, C. Tailor-made functional composite components using additive manufacturing and hot isostatic pressing. Powder Metall. 2021, 64, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieske, J.; Franke, M.; Schloffer, M.; Körner, C. Microstructure and properties of TiAl processed via an electron beam powder bed fusion capsule technology. Intermetallics 2020, 126, 106929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkoush, H.B.; Marchese, G.; Bassini, E.; Aversa, A.; Biamino, S. Microstructure of TiAl Capsules Processed by Electron Beam Powder Bed Fusion Followed by Post-Hot Isostatic Pressing. Materials 2023, 16, 5510. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, D.; Pan, Z.; Cuiuri, D.; Li, H.; Larkin, N.; van Duin, S. Multi-direction slicing of STL models for robotic wire-feed additive manufacturing. In Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium; The University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 2015; pp. 1059–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, M.; Weidemann, C.; Corves, B.; Hüsing, M. Trajectory Planning Strategy for Multidirectional Wire-Arc Additive Manufacturing. In ROMANSY 23—Robot Design, Dynamics and Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 467–475. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.C.; Ong, S.K.; Nee, A.Y.C. Robot path planning optimization for welding complex joints. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 90, 3829–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, G.; Montevecchi, F.; Scippa, A.; Campatelli, G. Optimization of WAAM Deposition Patterns for T-crossing Features. Procedia CIRP 2016, 55, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knezovic, N.; Topic, A. Wire and Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM)—A New Advance in Manufacturing. New Technol. Dev. Appl. 2019, 42, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.H.; Han, Y.S. Effect of Phase Transformations on Scanning Strategy in WAAM Fabrication. Materials 2021, 14, 7871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisgen, U.; Sharma, R.; Mann, S.; Oster, L. Increasing the manufacturing efficiency of WAAM by advanced cooling strategies. Weld. World 2020, 64, 1409–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.A.; Duarte, V.; Miranda, R.M.; Santos, T.G.; Oliveira, J.P. Current Status and Perspectives on Wire and Arc Additive Manufacturing (WAAM). Materials 2019, 12, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The FREECAD Team 2023, FREECAD Website. Available online: https://www.freecad.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- KUKA Roboter GmbH, KRL Reference Guide Release 4.1. Available online: http://robot.zaab.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/KRL-Reference-Guide-v4_1.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Scilab, Dassault Systèmes 2023. Available online: https://www.scilab.org/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Franco-Rendón, C.M.; León-Henao, H.; Bedoya-Zapata, A.D.; Santa, J.F.; Giraldo, J.E. Failure analysis of fillet welds with premature corrosion in 316L stainless steel slide gates using constitution diagrams. Rev. UIS Ing. 2020, 19, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.