Abstract

Hazardous gas detection requires portable, low-power sensors with high sensitivity, where micro-heater design is critical for semiconductor metal oxide (SMO) sensors. This study presents a standardized evaluation framework for quantitatively comparing patterned micro-heaters under equal-power conditions, ensuring objective comparison across geometries. Two key metrics—power efficiency and temperature uniformity—were defined, normalized, and integrated into a single optimal score through weighted summation. The framework was validated through coupled electro-thermal simulations and experiments on six geometries, including spiral and meander patterns. Results demonstrated that the framework enables accurate identification of designs combining low power consumption with high temperature uniformity. Notably, the meander-based design showed superior efficiency and uniformity, demonstrating its suitability for practical applications. This framework thus offers a rational tool for micro-heater design, supporting the development of reliable, energy-efficient devices for portable and Internet of Things (IoT) applications.

1. Introduction

With the rapid expansion of the Internet of Things (IoT) era, sensors have become a cornerstone technology for real-time data acquisition in diverse environments ranging from industrial process monitoring to personal healthcare. Sensors are increasingly required to combine miniaturization, low cost, high sensitivity, and high selectivity to satisfy the demands of next-generation applications. Among various sensor technologies, gas sensors are particularly critical for ensuring human safety and protecting the environment, as they enable the rapid and reliable detection of hazardous gasses, including toxic species such as CO, H2S and NO2, as well as flammable species such as H2 and CH4 [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Consequently, gas sensors are expected to play an essential role in emerging applications such as environmental monitoring networks, portable electronics, and wearable platforms. Gas sensors are classified according to the detection principle as electrochemical [7], optical [8], surface acoustic wave (SAW) [9], and semiconductor-based types [10]. Each of these approaches has demonstrated unique advantages; however, they are often constrained by limitations, such as high cost, complex instrumentation, slow response, and high power consumption. Semiconductor metal oxide (SMO) gas sensors have received considerable attention owing to their compact size, low fabrication cost, simple structure, and straightforward operation. Metal oxides such as SnO2, ZnO, WO3, NiO, and CuO exhibit high sensitivity and fast response and recovery times, and their compatibility with microelectromechanical system (MEMS) fabrication processes makes them particularly promising for integration and miniaturization [2,11,12,13].

Despite these advantages, SMO-based sensors typically require elevated operating temperatures (200–400 °C) to activate adsorption and desorption reactions at the sensing surface [14,15,16]. This makes the integration of a micro-heater indispensable. The characteristics of the micro-heater directly influence the sensing performance because both the sensitivity and response speed are strongly temperature-dependent. Simultaneously, maintaining uniform heating across the sensing layer is crucial to ensure reliability. Localized hot spots can accelerate material degradation and shorten the sensor lifetime, whereas low-temperature regions may yield incomplete reactions, leading to reduced sensitivity and inaccurate selectivity. Furthermore, for portable, wearable, and IoT-oriented applications, excessive power consumption severely limits the battery life and continuous operation. Therefore, an ideal micro-heater must simultaneously deliver (i) sufficient heat to reach the target operating temperature, (ii) minimal power consumption, and (iii) a uniform temperature distribution over the sensing area [17,18]. Numerous micro-heater geometries have been proposed to address these requirements, including box-shaped (e.g., rectangular mesh, line, and plate), annular (e.g., spiral, octagonal, and circular), and serpentine (e.g., meander, wing, and hook) designs [19]. In particular, spiral- and meander-type heaters have been reported to offer superior power efficiency and temperature uniformity because of their uniform current pathways and efficient Joule heating [20,21,22]. However, most previous studies have conducted evaluations under a fixed voltage or current bias, without considering the differences in electrical resistance across heater designs. Because the resistance directly determines the amount of heat generated for a given voltage or current, such approaches do not allow a fair and quantitative comparison of heater performance [23,24,25,26,27]. The absence of a standardized evaluation framework has impeded systematic design and optimization of micro-heaters in gas sensor applications.

In this study, we propose a standardized evaluation framework for patterned micro-heaters under equal-power input conditions. Two quantitative metrics were introduced: (i) power efficiency, defined as the average temperature rise per unit power, and (ii) temperature uniformity, defined as the temperature variation per unit power. Power efficiency serves as an indicator for evaluating high-efficiency operation, while temperature uniformity represents the degree of surface temperature consistency of the sensing material. These two metrics were normalized and integrated into a single performance index, referred to as the optimal score, which enables a comprehensive evaluation considering both efficiency and uniformity. To validate the framework, six different micro-heater patterns were analyzed in terms of their power efficiency and temperature uniformity, and the pattern with the best balance between these metrics was identified as the highest-performing design.

2. Methods

2.1. Optimal Design Framework Based on Thermal Performance Evaluation Metrics

2.1.1. Thermo-Electrical Coupling in a Patterned Micro-Heater

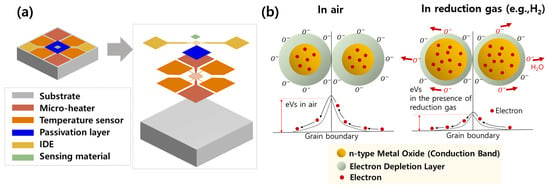

As shown in Figure 1, a typical metal oxide gas sensor consists of a sensing material (e.g., SnO2, ZnO, and WO3), interdigitated electrodes (IDE), a passive layer, a micro-heater, and a temperature sensor. The sensing material is the core component for gas detection. In air, oxygen molecules are adsorbed onto the surface, capturing the electrons from the conduction band and forming chemically adsorbed oxygen ions. This process creates an electron-depletion layer. When a reducing gas (such as H2S, CO or H2) reaches the sensing layer, it reacts with the adsorbed oxygen ions, releasing the captured electrons back to the conduction band. Consequently, the resistance between the electrodes decreased and this change was proportional to the gas concentration, allowing for quantitative measurement [28].

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic structure of a semiconductor metal oxide gas sensor. (b) Sensing mechanism of an n-type metal oxide in air and in the presence of a reducing gas.

This sensing mechanism is most effective when the sensing material is maintained at 200–400 °C, where oxygen adsorption–desorption is sufficiently activated, allowing a rapid surface reaction with the target gas. Consequently, the sensor achieved high sensitivity and fast response and recovery. Therefore, a micro-heater provides the required thermal energy, while a temperature sensor ensures stable operation at the target temperature [29,30,31]. Heating in the micro-heater occurs owing to Joule heating, where resistive elements generate heat under current flow. The heating power was expressed as follows:

with resistance:

where is the temperature-dependent resistivity; L, w, and t are the length, width, and thickness of the heater, respectively; is the resistivity at the reference temperature (293.15 K); and is the resistivity temperature coefficient.

The heat generated by Joule heating dissipates into the surrounding medium [32]. This heat loss can be categorized into three mechanisms: conduction, convection, and radiation. Among these, thermal conduction, also referred to as thermal diffusion, follows Fourier’s law which relates the local heat flux density to the temperature gradient as

where k is the thermal conductivity of the material and represents the temperature gradient. Expanding Equation (3) into Cartesian coordinates yields

Accordingly, the total conductive heat-transfer rate through the heater surface can be written as

Here, is the cross-sectional area through which conduction occurs. In addition to conduction, heat is also dissipated from the heater surface through convection and radiation. The convective heat transfer follows Newton’s law of cooling, expressed as

where is the convective heat-transfer coefficient, is the surface area exposed to air, is the surface temperature of the heater, and is the ambient air temperature. For radiative heat transfer, the Stefan–Boltzmann law describes the energy emitted by a surface as

where is the surface emissivity, is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant ( W ), and is the radiating surface area. Under steady-state conditions, the generated Joule heating power P is balanced by the total heat dissipation through these three mechanisms, as expressed by

All temperatures appearing in the conduction, convection, and radiation models in Equations (3)–(8) are expressed in absolute temperature (Kelvin).

When voltage is applied to the micro-heater, resistive (Joule) heating increases its temperature, and the generated heat is distributed throughout the sensor structure and into the surrounding environment. Heat is primarily transferred to the sensing layer and substrate via conduction, dissipated to the ambient gas by convection, and partially lost through radiation. Therefore, the final temperature of the sensing material was determined by the balance between the total heat generated in the heater and the combined losses from conduction, convection, and radiation. These heat transfer mechanisms have been widely applied in micro-heater modeling and design. As sensing reactions are most effective at elevated temperatures, maintaining a stable operating temperature is essential to ensure both sensitivity and rapid response and recovery. Therefore, the structural design of the micro-heater becomes a critical factor, as it must deliver sufficient heating while avoiding localized hot spots or under-heated regions that degrade the sensing performance. In particular, two design requirements must be satisfied simultaneously: power efficiency, which enables the heater to achieve and sustain high temperatures with minimal power consumption, and temperature uniformity, which ensures consistent heating across the entire sensing layer. These criteria are particularly important for portable IoT sensors with limited power budgets. Achieving both efficiency and uniformity reduces unnecessary energy consumption, extends long-term operating stability, and prevents localized overheating or cold spots. Consequently, the optimization of the micro-heater pattern must carefully balance the power efficiency and temperature uniformity to ensure reliable and high-performance gas sensing.

2.1.2. Methodology for Performance Evaluation of Micro-Heater Patterns

The temperature distribution of the sensing material changes with the micro-heater pattern structure, which determines the power efficiency and temperature uniformity. Therefore, it is important to systematically evaluate the power efficiency and temperature uniformity to compare the performances of the different pattern structures. However, when the micro-heater pattern structure was changed, the resistance value also changed, resulting in different heat generation even with the same input voltage. However, most previous studies have evaluated the pattern performance simply by using the temperature distribution without considering these differences in heat generation. To overcome this limitation and enable accurate and consistent comparison, the temperature level and uniformity of the sensing material should be evaluated based on the same amount of heat generation (under the same power consumption conditions). Therefore, this study aims to define power efficiency and temperature uniformity using the metrics presented in Equation (9) and used them to compare and evaluate the performance of various micro-heater patterns.

In this context, denotes the average temperature of the sensing material, corresponds to the temperature difference between the maximum and minimum values within the sensing material, and represents the input electrical power to the micro-heater, which is used as the source of heat generation.

The power efficiency metric () is defined as the average temperature rise divided by the input power; a larger value indicates better heating efficiency. In contrast, the temperature uniformity metric () is defined as the temperature deviation divided by the input power, with a smaller value indicating a more uniform temperature distribution. Therefore, to enhance sensor performance, a pattern structure that yields a large power efficiency metric and a small temperature uniformity metric is desirable. However, when these two metrics are evaluated independently, it is difficult to perform an integrated performance comparison that simultaneously considers power efficiency and temperature uniformity. Therefore, this study defines the optimal score as shown in Equation (10), to reflect both metrics simultaneously.

where

Here, and are the weighting factors, and and represent the normalized values of the power efficiency metric and the temperature uniformity metric, respectively.

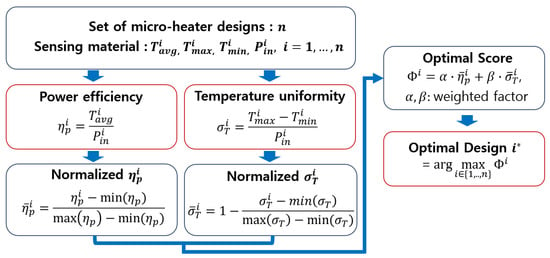

The optimal score defined in this manner can reflect the relative importance of the two metrics using weighting factors, and is useful for quickly and consistently comparing the performances of various micro-heater pattern structures. Accordingly, this study proposes a framework (Figure 2) for accurately and efficiently evaluating the performance of micro-thermal heater pattern structures. Here, the superscript * denotes the optimal design. Simulations were conducted using six different micro-thermal heater pattern structures to validate the proposed framework. Power efficiency and temperature uniformity metrics were calculated from the temperature distributions of the sensing materials obtained from the simulations. Finally, based on these two metrics, the optimal score was computed to identify the micro-heater pattern with the best performance.

Figure 2.

Framework for performance evaluation of micro-heater patterns.

2.2. Electro-Thermal Simulation of Patterned Micro-Heaters

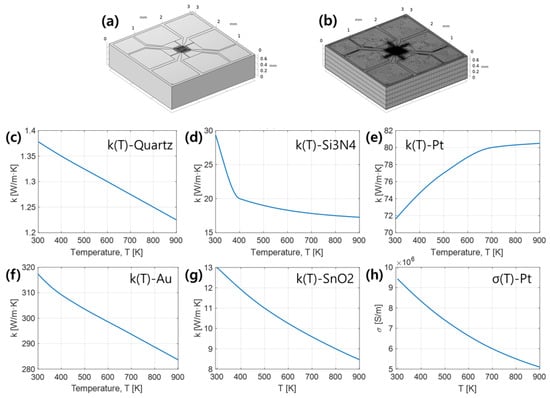

The heat transfer behavior of the micro-heater under Joule heating was analyzed using coupled electro-thermal simulations in COMSOL Multiphysics (version 6.3) Figure 3 and Table 1 present the sensor structure and material properties [33,34,35,36]. Thermal and electrical conductivities were temperature-dependent properties constructed by linear interpolation of literature data at 100 K intervals from 293 to 900 K. The thermal and electrical conductivities show strong temperature dependence, whereas the heat capacity and density vary only weakly. Thus, temperature-dependent conductivities were considered, while specific heat and density were treated as constants to maintain both accuracy and computational efficiency [37]. The micro-heater and temperature sensor were fabricated using a Pt/Ti stack, with Joule heating occurring mainly in the Pt layer. The Ti adhesion layer is only a few nanometers thick and contributes negligibly to heating resistance; therefore, Pt properties were used in the simulation. Likewise, the IDE electrode employed an Au/Ti stack, but due to the extremely thin Ti layer, Au dominated the thermal behavior and its material properties were used in the analysis. For the initial conditions, the entire computational domain was assumed to be at room temperature (). The boundary conditions are illustrated in Figure 4a,b. For the electrical boundary conditions, one terminal of the micro-heater was grounded ().

Figure 3.

(a) Geometry of the metal oxide gas sensor and (b) meshing configuration for numerical simulation. Temperature-dependent thermal conductivity of (c) quartz, (d) , (e) Pt, (f) Au, and (g) , and (h) temperature-dependent electrical conductivity of Pt used in the simulations.

Table 1.

Material properties of each layer in the micro-heater gas sensor structure.

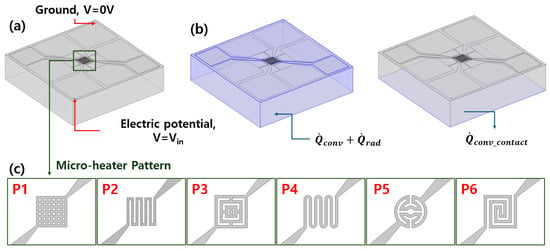

Figure 4.

Boundary conditions and design configurations: (a) Electrical boundary conditions with the ground set to 0 V and the input potential applied as . (b) Thermal boundary conditions including natural convection, radiation, and substrate contact conduction. (c) Six micro-heater pattern designs (P1–P6).

While an input voltage () was applied to the opposite terminal. For the thermal boundary conditions, the heat loss from natural convection was applied to the top and side surfaces of the gas sensor. A convective heat flux boundary condition was applied to the bottom surface of the gas sensor considering its contact with the chamber stage. Additionally, to consider the heat loss due to radiation, an emissivity of 0.9 was set for the top and side surfaces of the gas sensor. The six micro-heater pattern structures employed to validate the proposed framework are presented in Figure 4c. The contact heat transfer between the gas sensor and the chamber stage can vary considerably depending on factors such as surface roughness and contact pressure. As a result, the contact heat transfer coefficient reported in the literature spans a broad range of 1000–10,000 W/K [32,37].

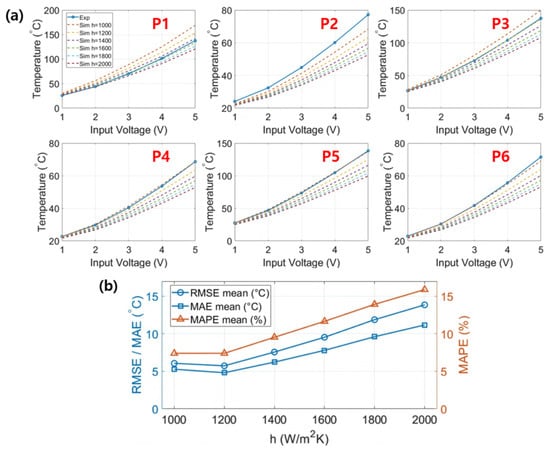

In this study, the contact heat transfer coefficient was determined to validate the electro-thermal simulation model by ensuring consistency between the simulation results and the experimental measurements. The experimental specimens, conditions, and corresponding results are provided in Appendix A. Figure 5a compares the experimental temperature sensor measurements with the corresponding simulation results for the six micro-heater patterns under different contact heat transfer coefficients. Figure 5b shows the average errors, namely, the mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), which were obtained by averaging the errors across the six heater patterns for each heat transfer coefficient. The analysis showed that when the contact heat transfer coefficient was set to 1200 W/K, the average MAE, RMSE, and MAPE were approximately , , and 7.4%, respectively, indicating the best agreement with the experimental results. Accordingly, the calibrated contact heat transfer coefficient was determined to be 1200 W/K in this study.

Figure 5.

Comparison of experimental and simulation results: (a) Temperature sensor measurements for six micro-heater patterns under different contact heat transfer coefficients. (b) Average errors (MAE, RMSE, and MAPE) across the six patterns as a function of the contact heat transfer coefficient.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Simulation Results of Various Heater Patterns

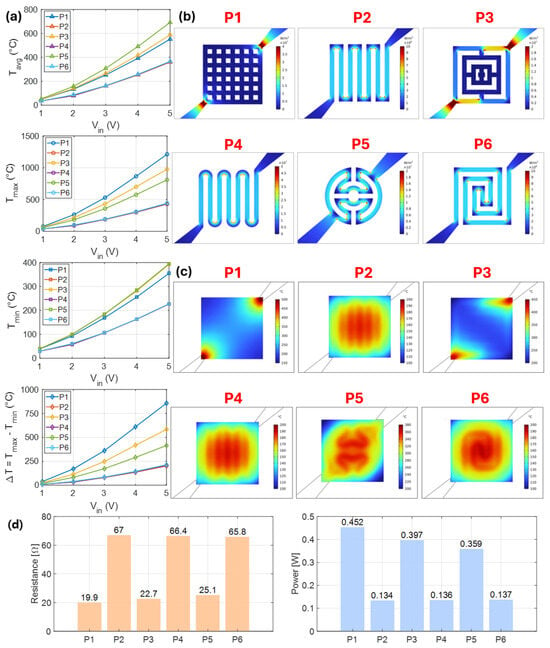

Figure 6a shows the simulation results of the average, maximum, minimum, and temperature difference of the sensing material for six micro-heater patterns under applied voltages ranging from 1 to 5 V. Figure 6b,c show the distributions of the surface loss density (power loss per unit area) of the micro-heaters and surface temperature of the sensing layer, respectively, under an applied voltage of 3V. The surface loss density is primarily concentrated in regions with narrow line widths and large curvature at the corners, where local intensification induces Joule heating, leading to the formation of hotspots. The generated heat subsequently spreads through conduction, convection, and radiation, thereby establishing an overall temperature field. During this process, the distribution and intensity of hotspots exert a significant influence on the overall thermal characteristics. For each pattern, P1 and P3 exhibited localized regions of high surface loss density near the electrode connections owing to the current concentration, which resulted in distinct hotspots adjacent to the electrodes. In contrast, P2, P4, P5, and P6 exhibited repeated occurrences of elevated surface loss densities in the small corner regions, leading to a more uniformly distributed heating source across the structure. The heat generated in these localized areas subsequently diffuses and overlaps, producing a broad high-temperature region in the central part of the sensing material. These results demonstrate that the current pathways and localized heating characteristics of each pattern correspond directly to the overall temperature distribution observed on the sensing material surface.

Figure 6.

Simulation results: (a) Average, maximum, minimum temperatures, and temperature difference of the sensing material surface as a function of input voltage for six micro-heater patterns. (b) Distribution of surface loss density of the micro-heater at an input voltage of 3 V. (c) Surface temperature distribution of the sensing material at an input voltage of 3 V. (d) Resistance of the micro-heater patterns. and corresponding power consumption.

Figure 6d shows the resistance of each micro-heater pattern and the corresponding input power under an applied voltage of 3 V. As the input power at a constant voltage follows the relationship in Equation (1), it can be observed that lower resistance results in higher input power. This indicates that the resistance varies with the pattern geometry; consequently, the heating power differs among the patterns, even under the same voltage conditions. A comparison of the temperature distributions solely under identical voltage conditions does not provide a reliable assessment of the intrinsic performance of each micro-heater pattern. This is because the observed differences were influenced by both the structural characteristics of the patterns and the variations in input power arising from resistance differences. Therefore, to properly evaluate the structural characteristics of the micro-heater patterns, the performance comparison in this study was conducted under identical input power conditions. The evaluation was systematically performed using the defined power efficiency metric, temperature uniformity metric, and the integrated performance metric (optimal score).

3.2. Evaluation Metric Results for Various Heater Patterns

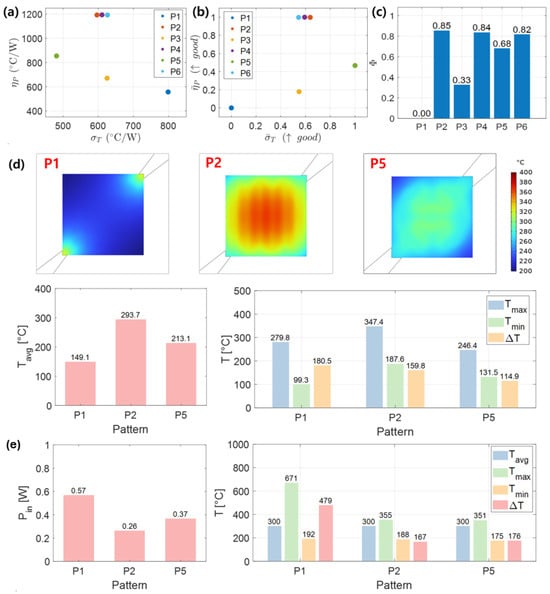

Figure 7a–c present the power efficiency and temperature uniformity metrics, their normalized values, and the final overall performance metric (, ). In this study, the weights were set to under the assumption that the two performance metrics have equal importance. This equal-weight assignment is not intended to prescribe an optimal design for any specific application; rather, it serves to demonstrate the fundamental concept and applicability of the proposed comprehensive evaluation methodology.Therefore, in practical design scenarios, the weighting factors can be adjusted according to the relative importance of power efficiency and temperature uniformity required for the target application. These results were determined based on the simulation conducted under an input voltage of 3 V (See Figure 6a,d). The analysis revealed that patterns P2, P4, and P6 exhibited the highest power efficiency, whereas pattern P5 showed the best temperature uniformity.

Figure 7.

Simulation Results for the micro-heater patterns: (a) Power efficiency and temperature uniformity metrics at . (b) Normalized values of the metrics in (a). (c) Optimal score derived from the normalized metrics. (d) Temperature distribution of the sensing material for patterns P1, P2, and P5 at the same input power of 250 mW. (e) Input power required to reach an average sensing-layer temperature of for patterns P1, P2, and P5, along with the corresponding thermal characteristics (average, maximum, minimum temperatures, and temperature difference).

In patterns such as P1 and P3, where current branching or intersection points are present, the current density becomes locally concentrated, leading to a significant increase in Joule loss density at these locations. This localized heating induces the formation of hot spots and nonlinearly enhances heat dissipation through convection and radiation, even under identical input power conditions. As a result, heat cannot be effectively accumulated across the sensing layer, limiting the increase in the average temperature, while the presence of localized high-temperature regions substantially increases the temperature deviation. This ultimately degrades the temperature uniformity of the sensing layer.

In contrast, the P2, P4, P5, and P6 patterns contain few current branching or intersection points compared with P1 and P3, resulting in a relatively uniform distribution of Joule loss density across the sensing area. The differences in power efficiency among these patterns are primarily governed by the effective heat dissipation path length, namely the dominant heat transfer path formed along the metal leads. For P2, P4, and P6, the metal lead length is relatively long (approximately 1.8 mm; see Appendix B), which increases the thermal resistance associated with heat dissipation along the lead direction. Consequently, even under identical input power conditions, heat is more effectively accumulated within the sensing layer, leading to a larger increase in the average temperature. As a result, these patterns exhibit superior power efficiency. However, in the case of P6, repeated changes in the current flow direction cause subtle localized increases in Joule loss density that gradually accumulate toward the central region. This leads to a tendency for heat generation to become relatively concentrated near the center. As a result, the temperature uniformity of P6 is slightly degraded compared with P2 and P4, in which heat generation is more linearly distributed and spatially dispersed.

Meanwhile, P5 has a relatively short metal lead length of approximately 0.81 mm (See Appendix B), which facilitates heat dissipation along the lead direction and results in a lower thermal resistance. Consequently, even under identical input power conditions, thermal accumulation within the sensing layer is limited, leading to a relatively lower increase in the average temperature. At the same time, P5 exhibits a structural characteristic in which Joule loss density is not concentrated in localized regions but is spatially distributed across the entire sensing area. Owing to this distributed heat generation, the formation of localized hot spots is effectively suppressed and the temperature gradient is mitigated, resulting in a smaller temperature deviation and the most superior temperature uniformity among the investigated patterns. When both performance aspects were integrated into the overall evaluation, patterns P2 and P4 achieved the highest optimal scores, indicating that meander-based heater designs represent the most effective configurations when considering power efficiency and temperature uniformity simultaneously.

To further validate the evaluation, the average temperature and temperature deviation of the sensing material were compared under identical input power conditions. For this comparison, three representative patterns were selected: P1 (low power efficiency and poor temperature uniformity), P2 (highest performance in both indices; P4 could also serve as an alternative high-performing configuration), and P5 (moderate power efficiency but superior temperature uniformity). Because the resistance values differed among the patterns, the input voltages were adjusted to 2.08 V for P1, 4.39 V for P2, and 2.41 V for P5 to ensure the same input power of 250 mW. As shown in Figure 7d, the results indicate that higher power efficiency leads to an increase in the average temperature, whereas higher temperature uniformity results in a reduction in temperature deviation. P1 exhibited the lowest average temperature and the largest temperature deviation, whereas P2 showed the highest average temperature and P5 demonstrated the smallest temperature deviation. However, when the temperature distributions were compared solely under identical voltage conditions (see Figure 6a), P5 appeared to exhibit the highest average temperature, whereas P2 showed the smallest temperature deviation. This discrepancy arises from the variation in input power caused by resistance differences among the patterns, underscoring the necessity of considering input power when objectively evaluating the performance of micro-heaters. Figure 7e compares the input power, maximum temperature, minimum temperature, and temperature difference on the surface of the sensing material for P1, P2, and P5, under the condition that the average temperature of the sensing layer(the operating temperature of the gas sensor) is fixed at 300 °C. As a result, P2 required only 0.26 W of input power to reach the target temperature, demonstrating the highest power efficiency 55% lower than P1 and 30% lower than P5. However, in terms of temperature uniformity, the temperature variation of P2 was only 5% smaller than that of P5, and this difference is likely due to the lower thermal input rather than any structural characteristics. This implies that P2 cannot necessarily be considered to have better intrinsic thermal uniformity than P5.

Therefore, by quantifying and normalizing both power efficiency and temperature uniformity, their integration into a single optimal score enables more accurate and objective comparisons of different micro-heater patterns. It was also confirmed that this optimal score effectively reflects the overall performance by accounting for both energy efficiency and thermal distribution characteristics.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

Previous studies have evaluated the performance of micro-heaters for metal oxide gas sensors by applying identical voltage or current and comparing the resulting temperature distributions, which does not allow an accurate assessment of the structural effects of different micro-heater patterns. This is because the observed temperature distribution is influenced by both the structural characteristics of the patterns and the variations in input power arising from resistance differences.

In this study, we proposed and validated an evaluation framework for the accurate and quantitative comparison of micro-heater performance according to structural variations. A power efficiency metric, defined as the average temperature rise per unit of power consumption, and a temperature uniformity metric, defined as the temperature deviation per unit of power consumption, were introduced to enable precise evaluation of low-power operation and uniform heating depending on the structural characteristics of micro-heater patterns. Furthermore, these two metrics were normalized and combined through weighted summation to derive a single integrated metric, referred to as the optimal score, for comprehensive performance evaluation. The results confirmed that the proposed methodology can accurately and quantitatively identify micro-heater patterns that simultaneously achieve low-power operation and excellent temperature uniformity. Its validity was further demonstrated through boundary condition calibration by comparing experimental and simulation results, as well as a case study analysis of six different patterns. Accordingly, the proposed framework facilitates rapid screening and informed decision-making in micro-heater design, providing a practical basis for enhancing battery life and ensuring reliable long-term monitoring in portable and IoT applications.

Future work will focus on detailed optimization of the best-performing pattern, P2, by varying design parameters such as line width, spacing, and thickness. To achieve this, advanced design exploration techniques, such as Bayesian optimization, will be applied based on the proposed evaluation framework to further enhance the performance of micro-heaters with greater precision.

Author Contributions

J.Y. performed the finite element simulations and analyzed the results. Y.H. devised and conducted the experiments. J.K. contributed to data processing and figure preparation. J.P. and D.G.J. provided technical expertise, supervision, and critical feedback. All authors contributed to improving the manuscript and reviewed it multiple times prior to submission. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research and Development Reserve Fund Program (UR250005) of the Korea Institute of Industrial Technology (KITECH). This study is a 2024 SME Technology Innovation Development Export-Oriented (Tech-Bridge) R&D project of the Small and Medium Business Technology Information Promotion Agency (SME Technology Innovation Development Institute), and is a study on tungsten oxide-based nanopowder synthesis and NOx gas sensor development (RS-2024-00469383). This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (2018R1D1A1B07040446).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Experimental Details

Appendix A.1. Fabrication Process of Patterned Micro-Heater Integrated Gas Sensor

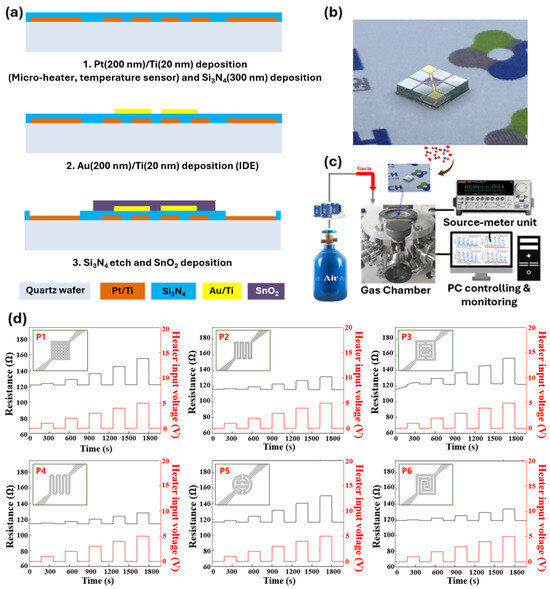

Patterned micro-heaters for gas sensor applications were designed and fabricated in this study. Each chip consisted of six heater patterns (P1–P6), a temperature sensor, an interdigitated electrode (IDE), and a SnO2 sensing layer. The chip and sensing area sizes were and , respectively. The widths and thicknesses of the heaters, temperature sensors, and IDEs were and . A quartz wafer was used to reduce heat loss, Pt was selected for both the heater and temperature sensor due to its linear resistance–temperature behavior, and Au and SnO2 were used for the IDE and sensing layer. Figure A1a,b show the fabrication process and a photograph of the fabricated chip. The fabrication steps were: (1) substrate cleaning with acetone and methanol for 10 min; (2) patterning of heaters and temperature sensors by photolithography, followed by Pt/Ti deposition via e-beam evaporation and lift-off; (3) deposition of Si3N4 by PECVD as the insulation and passivation layer; (4) IDE formation by photolithography, Au deposition, and lift-off; and (5) sputtering of SnO2 and etching of Si3N4 to open the electrical pads.

Appendix A.2. Experimental Setup and Results

The performance of the fabricated temperature sensor and micro-heaters (P1–P6) was evaluated using a measurement system composed of a DC power supply, a commercial heater, a gas chamber, and a source meter unit (SMU) (see Figure A1c). The resistance of the temperature sensor, measured using the commercial heater, increased linearly with temperature, enabling real-time estimation of the heating performance of the P1–P6 micro-heaters. Different input voltages were applied to the micro-heaters, and their heating characteristics were obtained by monitoring the corresponding resistance changes. Figure A1d show the resistance variations of the temperature sensor as functions of the micro-heater patterns (P1–P6) and the applied input voltage.

Figure A1.

(a) Fabrication process of micro-heaters with patterns P1–P6. (b) Photograph of the fabricated micro-heater chip. (c) Experimental setup used to characterize micro-heater performance. (d) Resistance variations of the temperature sensor for micro-heater patterns P1–P6 under different input voltages.

Appendix B. Geometric Details of the Micro-Heater Patterns

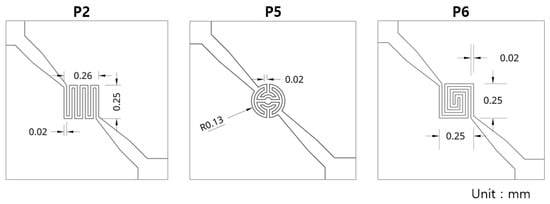

The geometric dimensions of the P2, P5, and P6 patterns are shown in Figure A2, and pattern P4 was generated by applying a fillet radius of 0.01 mm to the corner regions of the P2 heater.

Figure A2.

Geometric dimensions of the representative micro-heater patterns P2, P5, and P6.

References

- Morsi, I.G.; Khedr, M.E.; Aly, A.G.E. Detection of LPG Gas by Using Multi Sensors Array and Fabricated ZnO Gas Sensor. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2128, 012005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Pinna, N. Atomic Layer Deposition to Heterostructures for Application in Gas Sensors. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2023, 5, 022008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Zeng, W.; Li, Y. Gas Sensing Mechanisms of Metal Oxide Semiconductors: A Focus Review. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 22664–22684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaqoob, U.; Jaber, N.; Alcheikh, N.; Younis, M.I. Selective Multiple Analyte Detection Using Multi-Mode Excitation of a MEMS Resonator. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farea, M.A.; Mohammed, H.Y.; Shirsat, S.M.; Sayyad, P.W.; Ingle, N.N.; Al-Gahouari, T.; Mahadik, M.M.; Bodkhe, G.A.; Shirsat, M.D. Hazardous Gases Sensors Based on Conducting Polymer Composites. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2021, 776, 138703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, H.R.; Kordrostami, Z.; Mirzaei, A. In-Vehicle Wireless Driver Breath Alcohol Detection System Using a Microheater Integrated Gas Sensor Based on Sn-Doped CuO Nanostructures. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, E.; Telting-Diaz, M. Electrochemical Sensors. Anal. Chem. 2002, 74, 2781–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Liao, B. Theoretical Investigation of a Dual-Channel Optical Fibre Surface Plasmon Resonance Hydrogen Sensor Based on Wavelength Modulation. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2013, 24, 065102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, S.; Hanif, M.; Jeoti, V.; Stojanović, G.M.; Khan, M.T. Review of Fabrication of SAW Sensors on Flexible Substrates: Challenges and Future. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Zhou, X.; Wang, C.; Shimanoe, K.; Lu, G.; Yamazoe, N. Hollow SnO2/α-Fe2O3 Spheres with a Double-Shell Structure for Gas Sensors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 1302–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-I.; Kim, H.-J.; Kang, Y.C.; Lee, J.-H. Ultraselective and Ultrasensitive Detection of H2S in Highly Humid Atmosphere Using CuO-Loaded SnO2 Hollow Spheres for Real-Time Diagnosis of Halitosis. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 194, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kida, T.; Fujiyama, S.; Suematsu, K.; Yuasa, M.; Shimanoe, K. Pore and Particle Size Control of Gas Sensing Films Using SnO2 Nanoparticles Synthesized by Seed-Mediated Growth. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 17574–17582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-W.; Katoch, A.; Sun, G.-J.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, S.S. Dual Functional Sensing Mechanism in SnO2–ZnO Core–Shell Nanowires. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 8281–8287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Y.; Okawa, Y.; Inoue, K.; Natukawa, K. Low-Voltage and Low-Power Optimization of Micro-Heater and Its On-Chip Drive Circuitry for Gas Sensor Array. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2002, 100, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun-Kou, R.; Paredes-Doig, A.; Picasso, G.; La Rosa-Toro, A.; Doig-Camino, E. Effect of Temperature on Methanol and Ethanol Measurement Using Noble Metal Doped Tin Oxide Sensors. In Proceedings of the Electrochemical Society Meeting Abstracts; The Electrochemical Society: Pennington, NJ, USA, 2021; p. 1438. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.-Y.; Yuan, K.-P.; Yang, J.-H.; Hang, C.-Z.; Ma, H.-P.; Ji, X.-M.; Devi, A.; Lu, H.-L.; Zhang, D.W. Hierarchical Highly Ordered SnO2 Nanobowl Branched ZnO Nanowires for Ultrasensitive and Selective Hydrogen Sulfide Gas Sensing. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2020, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Wang, S.; Lu, M.; Zuo, L. A Novel Polyimide Based Micro Heater with High Temperature Uniformity. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2017, 257, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeroish, Z.E.; Bhuvaneshwari, K.S.; Samsuri, F.; Narayanamurthy, V. Microheater: Material, Design, Fabrication, Temperature Control, and Applications—A Role in COVID-19. Biomed. Microdevices 2022, 24, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, P.B.; Shiurkar, U.D. MEMS for Detection of Environmental Pollutants: A Review Pertains to Sensors over a Couple of Decades in 21st Century. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 44, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeslam, A.; Fouad, K.; Khalifa, A. Design and Optimization of Platinium Heaters for Gas Sensor Applications. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2020, 15, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, B. Influence of Microheater Patterns: MoSi2-SnO2 as Energy-Saving Chemiresistors for Gas Sensing Applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 351, 130901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandewad, G.W.; Pawar, S.N.; Shinde, P.B.; Kamble, C.P. Design and Optimization of Microheater for Smart Gas Sensor Applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 3314–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwaria, S.K.; Bhata, S.; Mahatob, K.K.; Manjunathc, B.B. Design and Simulation of Parallel Microheater. Front. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yuan, L.; Hua, Z.; Zhen, D.; Qiu, Z. Design and Optimization of Heating Plate for Metal Oxide Semiconductor Gas Sensor. Microsyst. Technol. 2019, 25, 3511–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoui, S.; Gomri, S.; Samet, H.C.; Kachouri, A. Design, Simulation, and Optimization of a Meander Micro Hotplate for Gas Sensors. Trans. Electr. Electron. Mater. 2016, 17, 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, N.G.; Suganthi, S.; Arulmozhi, M.; Sivakumar, P.; Sophia, S.J. Design and Evaluation of Micro-Heater Geometries for MEMS-Based Ozone Gas Sensor through a Theoretical Modeling. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 66, 2012–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardon, M.; Guilemany, J.M. A Review on Fabrication, Sensing Mechanisms and Performance of Metal Oxide Gas Sensors. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2013, 24, 1410–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Jayaraman, V. SnO2: A Comprehensive Review on Structures and Gas Sensors. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 66, 112–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, N.; Yamada, S.; Yagi, T.; Taketoshi, N.; Jia, J.; Shigesato, Y. Thermophysical Properties of SnO2-Based Transparent Conductive Films: Effect of Dopant Species and Structure. J. Mater. Res. 2014, 29, 1579–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Zou, H. Implementing an analytical model to elucidate the impacts of nanostructure size and topology of morphologically diverse zinc oxide on gas sensing. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Knoepfel, A.; Zou, H.; Ding, Y. Investigations of methane gas sensor based on biasing operation of n-ZnO nanorods/p-Si assembled diode and Pd functionalized Schottky junctions. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 392, 134030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masato, D.; Kazmer, D.; Gruber, A. Meta-Analysis of Thermal Contact Resistance in Injection Molding: A Comprehensive Literature Review and Multivariate Modeling. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2023, 63, 3923–3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hot Disk Instruments. Measuring Thermal Conductivity of Fused Quartz in the Temperature Range 20–1000 °C; Application Note, n.d. Available online: https://www.hotdiskinstruments.com/applications/application-notes/measuring-thermal-conductivity-of-fused-quartz-in-the-temperature-range-20c-to-1000c/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Ho, C.Y.; Powell, R.W.; Liley, P.E. Thermal Conductivity of the Elements. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1972, 1, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, D.R.; O’Hagan, M.E. Measurements of the Thermal Conductivity and Electrical Resistivity of Platinum from 100 to 900 °C; NBS Report 9387; Institute for Applied Technology, National Bureau of Standards: Washington, DC, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Touloukian, Y.S.; Powell, R.W.; Ho, C.Y.; Klemens, P.G. (Eds.) Thermophysical Properties of Matter, Vol. 2: Thermal Conductivity—yNonmetallic Solids; IFI/Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Ustinov, V.A. Experimental Investigation and Modeling of Contact Heat Transfer. Ph.D. Thesis, RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.