Design and Performance Evaluation of Double-Curvature Impellers for Centrifugal Pumps

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

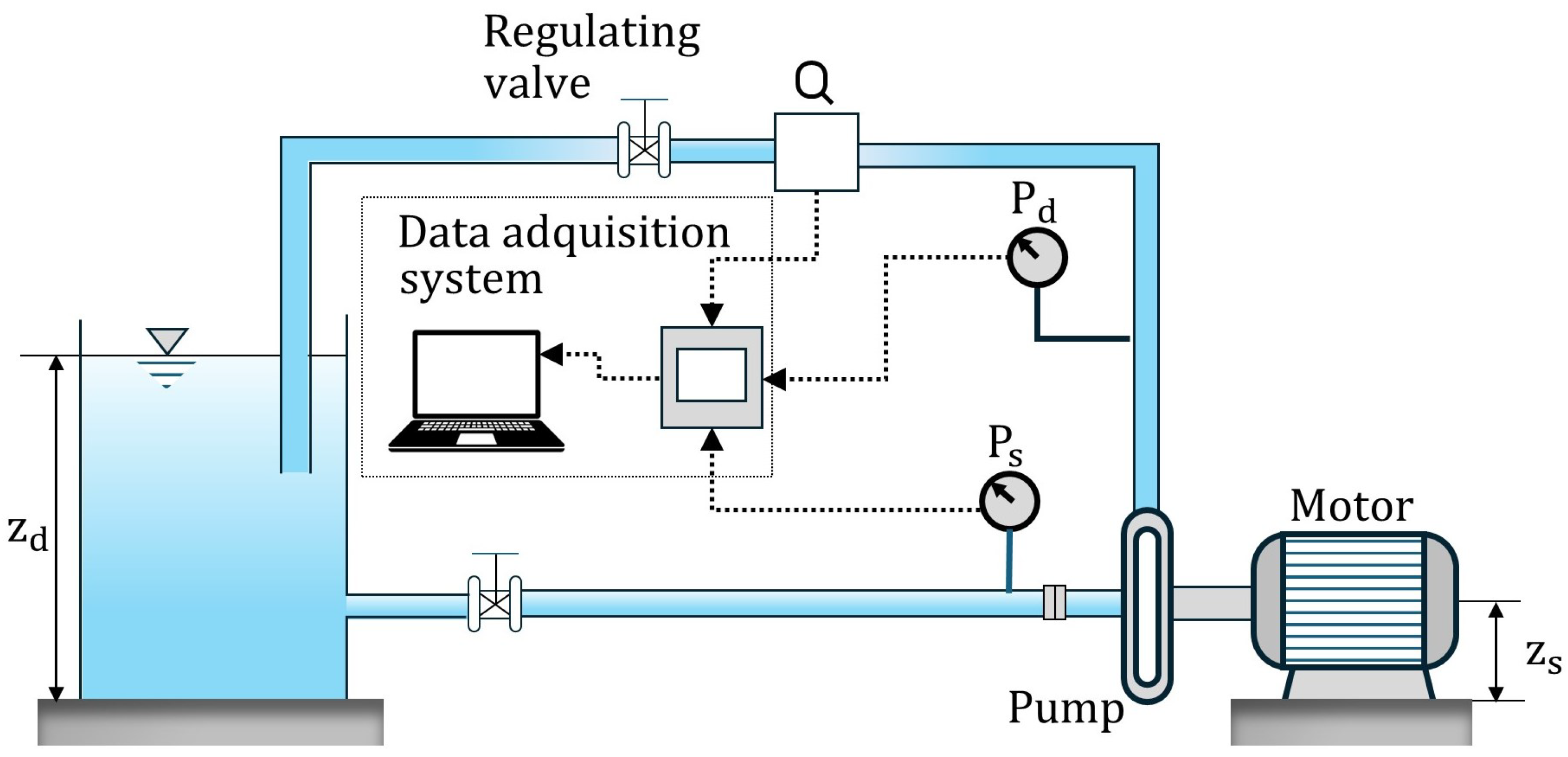

2.1. Experimental Setup

- High-precision sensors: Autonics pressure gauges for suction and discharge pressures.

- Flow measurement: Signet 8550 flow transmitters to ensure accurate volumetric flow readings.

- Power and efficiency monitoring: FLUKE 1735 Power Logger energy analyzer to measure motor power consumption.

- Speed control: A variable frequency drive (VFD) to regulate motor speed at 1400, 1700, and 1900 rpm.

- Data acquisition system: Developed in LabView, it is capable of recording 100 data points per second and providing averaged values.

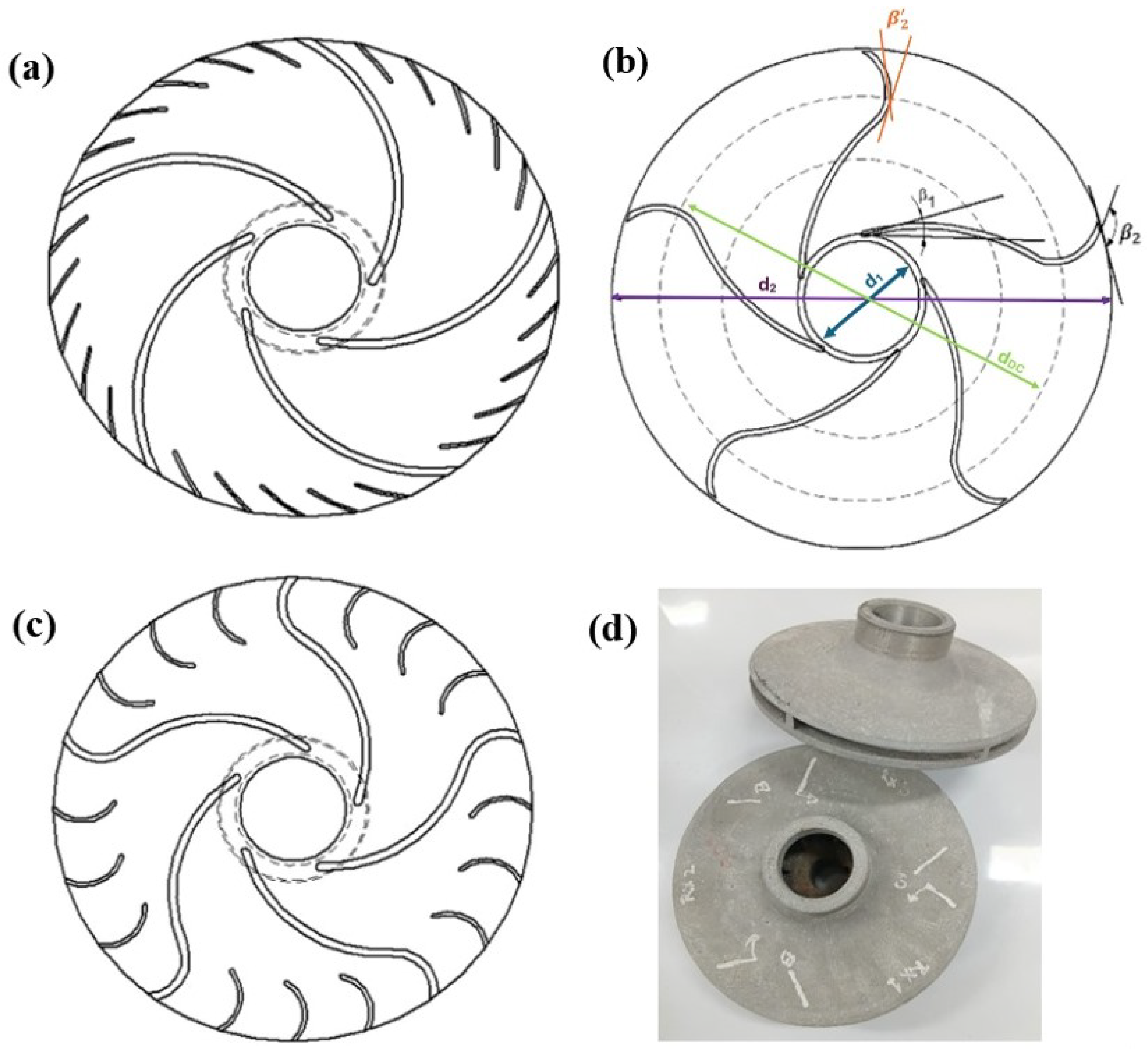

2.2. Impeller Characteristics

- : Impeller inlet blade angle.

- : Primary impeller outlet blade angle.

- : Secondary outlet blade angle in double-curvature impellers.

- (%): Percentage of double curvature (15%, 25%, or 35%).

- : Double-curvature transition diameter.

2.3. Testing Procedure

2.4. Head Calculation

2.5. Pump-Motor Unit Efficiency Calculation

3. Results and Discussion

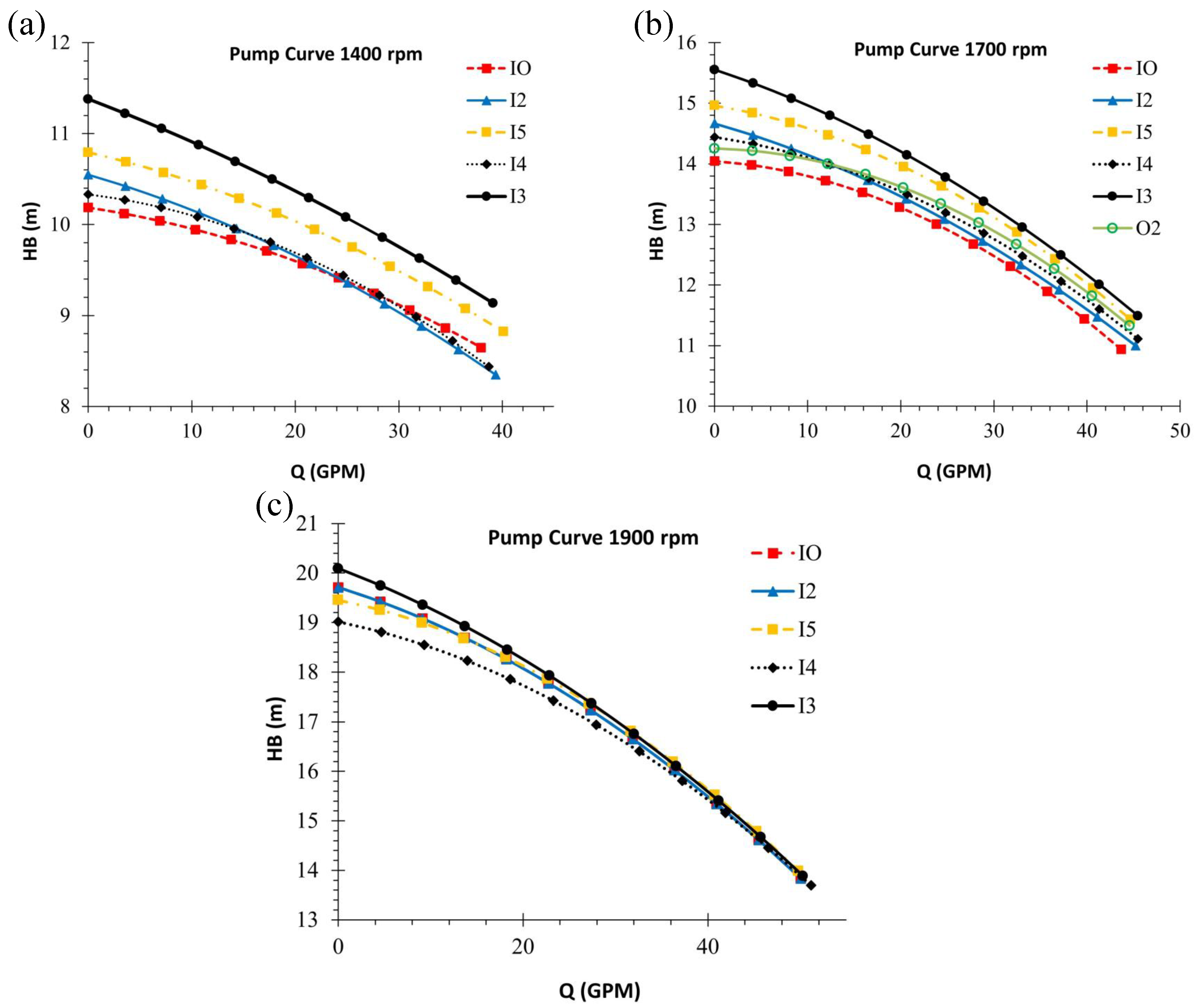

3.1. Head–Flow Rate Relationship

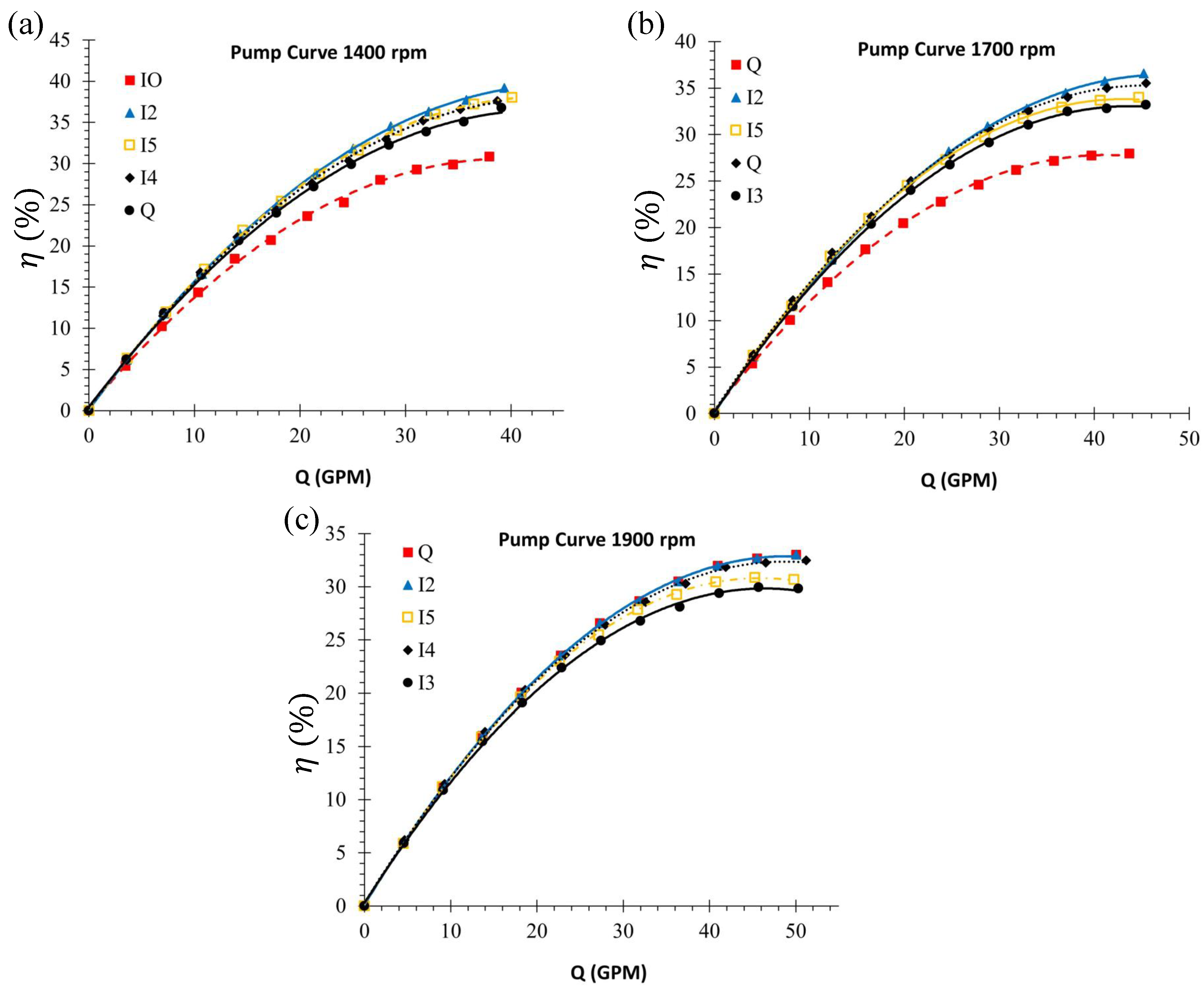

3.2. Pump-Motor Efficiency

3.3. Power Consumption Analysis

3.4. Discussion of Experimental Findings

4. Conclusions

- Head–flow rate performance: Impellers incorporating double-curvature profiles exhibited a consistent improvement in head generation compared to the baseline (uncurved) impeller. The 25% and 35% curvature configurations demonstrated the highest head values, indicating that blade curvature enhances pressure rise capabilities across a wide range of flow conditions.

- Hydraulic efficiency improvement: The adoption of double-curvature geometries led to increased pump-motor efficiency, particularly in mid-range flow rates. This improvement is attributed to enhanced flow guidance and reduced internal losses due to minimized turbulence and flow separation.

- Energy consumption considerations: While impellers with higher curvature (notably 35%) resulted in a moderate increase in power consumption at maximum flow rates, the observed gains in hydraulic performance suggest a favorable trade-off. The results indicate that performance enhancements can be achieved without disproportionate energy penalties.

- Flow rate capacity enhancement: Double-curvature impellers achieved superior maximum flow rates across all tested rotational speeds. Notably, the I4 impeller (35% curvature) delivered the highest flow rate at 1900 rpm, followed closely by I3 (25%) and I2 (15%), confirming the influence of blade geometry on volumetric capacity.

- Most favorable design configuration: Among all evaluated configurations, the 25% double-curvature impeller offered the best compromise between improved head, enhanced efficiency, and manageable energy consumption. Although the 35% design delivered higher head, it exhibited diminishing returns in efficiency and energy performance.

- Practical and industrial relevance: The results support the application of double-curvature impellers in energy-intensive industrial environments where performance optimization is critical. These findings reinforce the role of geometric refinement in centrifugal pump design and highlight the need for continued research into curvature parameterization and scaling for larger pump systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Capurso, T.; Bergamini, L.; Torresi, M. Performance analysis of double suction centrifugal pumps with a novel impeller configuration. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2022, 14, 100227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.; Zhu, H.; Ren, Y.; Zheng, S. Hydraulic dissipation analysis in reversible pump with a novel double-bend impeller for small pumped hydro storage based on entropy generation theory. Energy 2024, 313, 134129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, Q.; Ding, P.; Ji, Q.; Cheng, L. Experimental investigation of the impact of blade number on energy performance and pressure fluctuation in a high-speed coolant pump for electric vehicles. Energy 2024, 313, 133925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaeefard, M.H.; Saremian, S. Analyzing the impact of blade geometrical parameters on energy recovery and efficiency of centrifugal pump as turbine installed in the pressure-reducing station. Energy 2024, 289, 130004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cao, Z.; Wei, Z.; Ren, Q. Theoretical model of energy conversion and loss prediction for multi-stage centrifugal pump as turbine. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 325, 119379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y. Dynamic analysis of the impeller under optimized blade design for a pump-turbine. J. Energy Storage 2025, 107, 114900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Shen, X.; Pan, Q.; Ding, J.; Luo, W.; Meng, J.; Zhang, D. Multi-objective optimization design for broadening the high efficiency region of hydrodynamic turbine with forward-curved impeller and energy loss analysis. Renew. Energy 2025, 245, 122818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cai, S.; Li, Y.J.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.X. Optimization design of multiphase pump impeller based on combined genetic algorithm and boundary vortex flux diagnosis. J. Hydrodyn. 2017, 29, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntiri Asomani, S.; Yuan, J.; Wang, L.; Appiah, D.; Adu-Poku, K.A. The Impact of Surrogate Models on the Multi-Objective Optimization of Pump-As-Turbine (PAT). Energies 2020, 13, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Asomani, S.N.; Yuan, J.; Appiah, D. Geometrical Optimization of Pump-As-Turbine (PAT) Impellers for Enhancing Energy Efficiency with 1-D Theory. Energies 2020, 13, 4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentzos, M.; Kassanos, I.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Filios, A. The Effect of Blade Angle Distribution on the Flow Field of a Centrifugal Impeller in Liquid-Gas Flow. Energies 2024, 17, 3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shao, J.; Yang, F.; Zhu, Q.; Zuo, M. Optimization design of centrifugal pump cavitation performance based on the improved BP neural network algorithm. Meas. J. Int. Meas. Confed. 2025, 245, 116553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, S.; Niu, T. Unsteady Study on the Influence of the Angle of Attack of the Blade on the Stall of the Impeller of the Double-Suction Centrifugal Pump. Energies 2022, 15, 9528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Zhuang, B.; Wei, Y.; Luo, X.; Wang, H. Investigation on the unstable flow characteristic and its alleviation methods by modifying the impeller blade tailing edge in a centrifugal pump. J. Energy Storage 2024, 86, 111358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, F.; Masi, M. A Hybrid Experimental-Numerical Method to Support the Design of Multistage Pumps. Energies 2023, 16, 4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oro, J.M.F.; Perotti, R.B.; Vega, M.G.; González, J. Effect of the radial gap size on the deterministic flow in a centrifugal pump due to impeller-tongue interactions. Energy 2023, 278, 127820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhao, Z.; He, X.; Zeng, W.; Yang, J.; Yang, J. Design techniques for improving energy performance and S-shaped characteristics of a pump-turbine with splitter blades. Renew. Energy 2023, 212, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, W.; Chen, F.; Cai, J.; Wang, X.M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.L.; Wang, Q. Performance prediction and optimization strategy for LNG multistage centrifugal pump based on PSO-LSSVR surrogate model. Cryogenics 2024, 140, 103856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Li, L.; Wang, B.; Wang, H.; Yu, J.; Liang, L.; Xie, C.; Tang, Y. Optimization of submersible LNG centrifugal pump blades design based on support vector regression and the non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II. Energy 2024, 313, 133812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Pei, J.; Wang, W. Effect of impeller and diffuser matching optimization on broadening operating range of storage pump. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Luo, G.; Li, Y.; Xia, R.; Liu, H. Multi-condition optimization and experimental verification of impeller for a marine centrifugal pump. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2020, 12, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Pu, K.; Shi, P.; Wu, P.; Huang, B.; Wu, D. Blade redesign based on secondary flow suppression to improve the dynamic performance of a centrifugal pump. J. Sound Vib. 2023, 554, 117689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, A.; Lin, Z.; Chen, D.; Li, Y. A review on the hydraulic performance and erosion wear characteristic of the centrifugal slurry pump. Particuology 2024, 95, 370–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuchar-Curi, A.M.; Coronado-Hernández, O.E.; Useche, J.; Abuchar-Soto, V.J.; Palencia-Díaz, A.; Paternina-Verona, D.A.; Ramos, H.M. Improving Pump Characteristics through Double Curvature Impellers: Experimental Measurements and 3D CFD Analysis. Fluids 2023, 8, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Wu, P.; Huang, B.; Wu, D. Optimization of a centrifugal pump to improve hydraulic efficiency and reduce hydro-induced vibration. Energy 2023, 268, 126677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J. Optimization of a centrifugal pump with high efficiency and low noise based on fast prediction method and vortex control. Energy 2024, 289, 129835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhu, J.; Tang, F.; Wang, C. Multi-Disciplinary Optimization Design of Axial-Flow Pump Impellers Based on the Approximation Model. Energies 2020, 13, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Peng, G.; Lin, R.; Lou, Y.; Shi, W.; Zhou, L. Efficiency optimization of energy storage centrifugal pump by using energy balance equation and non-dominated sorting genetic algorithms-II. J. Energy Storage 2025, 114, 115817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASME PTC 8.2-1990; Centrifugal Pumps. American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 1990.

| Impeller | (°) | (°) | (°) | (%) | (mm) | NSB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IO | 27 | 30 | - | - | - | 5 |

| I2 | 27 | 135 | 30 | 35 | 133.2 | 3 |

| I3 | 27 | 80 | 30 | 35 | 133.2 | 3 |

| I4 | 27 | 135 | 30 | 15 | 159.9 | 5 |

| I5 | 27 | 80 | 30 | 25 | 146.6 | 3 |

| Impeller | (rpm) | A | B | C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IO | 1400 | 10.19 | 99.32 | ||

| 1700 | 14.05 | 98.66 | |||

| 1900 | 19.71 | 99.18 | |||

| I2 | 1400 | 10.55 | 99.35 | ||

| 1700 | 14.67 | 99.21 | |||

| 1900 | 19.72 | 99.26 | |||

| I3 | 1400 | 11.38 | 97.90 | ||

| 1700 | 15.55 | 99.27 | |||

| 1900 | 20.09 | 99.49 | |||

| I4 | 1400 | 10.33 | 99.82 | ||

| 1700 | 14.44 | 99.42 | |||

| 1900 | 19.02 | 99.64 | |||

| I5 | 1400 | 10.79 | 98.92 | ||

| 1700 | 14.96 | 99.26 | |||

| 1900 | 19.45 | 99.34 |

| Impeller | (rpm) | D | E | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IO | 1400 | 99.87 | |||

| 1700 | 99.95 | ||||

| 1900 | 99.99 | ||||

| I2 | 1400 | 99.99 | |||

| 1700 | 99.99 | ||||

| 1900 | 99.97 | ||||

| I3 | 1400 | 99.92 | |||

| 1700 | 99.98 | ||||

| 1900 | 99.96 | ||||

| I4 | 1400 | 99.95 | |||

| 1700 | 99.96 | ||||

| 1900 | 99.95 | ||||

| I5 | 1400 | 99.98 | |||

| 1700 | 99.98 | ||||

| 1900 | 99.98 |

| Impeller | 1400 rpm | 1700 rpm | 1900 rpm |

|---|---|---|---|

| IO | 37.95 | 43.68 | 50.04 |

| I2 | 39.35 | 45.20 | 50.04 |

| I3 | 39.09 | 45.46 | 50.29 |

| I4 | 38.71 | 45.46 | 51.18 |

| I5 | 40.11 | 44.69 | 49.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Palencia-Díaz, A.; Abuchar-Curi, A.M.; Fábregas-Villegas, J.; Guillén-Rujano, R.; Parejo-García, M.; Velilla-Díaz, W. Design and Performance Evaluation of Double-Curvature Impellers for Centrifugal Pumps. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010180

Palencia-Díaz A, Abuchar-Curi AM, Fábregas-Villegas J, Guillén-Rujano R, Parejo-García M, Velilla-Díaz W. Design and Performance Evaluation of Double-Curvature Impellers for Centrifugal Pumps. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):180. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010180

Chicago/Turabian StylePalencia-Díaz, Argemiro, Alfredo M. Abuchar-Curi, Jonathan Fábregas-Villegas, Renny Guillén-Rujano, Melissa Parejo-García, and Wilmer Velilla-Díaz. 2026. "Design and Performance Evaluation of Double-Curvature Impellers for Centrifugal Pumps" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010180

APA StylePalencia-Díaz, A., Abuchar-Curi, A. M., Fábregas-Villegas, J., Guillén-Rujano, R., Parejo-García, M., & Velilla-Díaz, W. (2026). Design and Performance Evaluation of Double-Curvature Impellers for Centrifugal Pumps. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010180