Abstract

The electric power grid constitutes a foundational pillar of modern critical infrastructure (CI), underpinning societal functionality and global economic stability. Yet, the increasing convergence of Information Technology (IT) and Operational Technology (OT), particularly through the integration of Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) and Industrial Control Systems (ICS), has amplified the sector’s exposure to sophisticated cyber threats. This study conducts a comparative analysis of five major cyber incidents targeting electric power systems: the 2015 and 2016 Ukrainian power grid disruptions, the 2022 Industroyer2 event, the 2010 Stuxnet attack, and the 2012 Shamoon incident. Each case is examined with respect to its objectives, methodologies, operational impacts, and mitigation efforts. Building on these analyses, the research evaluates the extent to which such attacks could have been prevented or mitigated through the systematic adoption of leading cybersecurity maturity frameworks. The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0, the ENISA NIS2 Directive Risk Management Measures, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (C2M2), and the Cybersecurity Risk Foundation (CRF) Maturity Model alongside complementary technical standards such as NIST SP 800-82 and IEC 62443 have been thoroughly examined. The findings suggest that a proactive, layered defense architecture grounded in the principles of these frameworks could have significantly reduced both the likelihood and the operational impact of the reviewed incidents. Moreover, the paper identifies critical gaps in the existing maturity models, particularly in their ability to capture hybrid, cross-domain, and human-centric threat dynamics. The study concludes by proposing directions for evolving from compliance-driven to resilience-oriented cybersecurity ecosystems, offering actionable recommendations for policymakers and power system operators to strengthen the cyber-physical resilience of electric generation and distribution infrastructures worldwide.

1. Introduction

The stability and security of modern nations are profoundly dependent on the resilience of their Critical Infrastructure (CI). Among these interconnected systems, the electric power grid plays a central and indispensable role, functioning as the foundation upon which other vital sectors such as finance, healthcare, transportation, and communications rely [1]. A sustained disruption to electrical power can cause cascading failures across the socio-economic spectrum, producing systemic consequences that extend far beyond operational inconvenience to encompass national security and public safety concerns.

The increasing convergence of Information Technology (IT) and Operational Technology (OT), driven by demands for greater efficiency, automation, and remote operability, has concurrently expanded the cyber threat landscape for Industrial Control Systems (ICS) and Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) networks that govern power generation and distribution processes. These environments, frequently constrained by legacy components, proprietary communication protocols, and prolonged life cycles, remain particularly susceptible to exploitation by state-sponsored adversaries, organized cybercriminals and ideologically motivated actors [2].

Despite the abundance of cybersecurity frameworks and maturity models available to operators of critical energy infrastructure, there remains limited clarity on how effectively these models address real-world ICS/SCADA attack scenarios. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine whether leading cybersecurity maturity frameworks (specifically NIST CSF 2.0, ENISA NIS2 Directive risk management measures, C2M2, and the Cybersecurity Risk Foundation (CRF) model) provide sufficient guidance to mitigate or prevent major cyber incidents targeting electric power systems. To achieve this aim, the paper conducts a comparative analysis of five significant cyberattacks that have directly affected (or demonstrated the capability to affect) power sector operations.

By linking the observed attack vectors and failure points to the controls, functions, and maturity domains of the selected frameworks, this study identifies persistent gaps and highlights areas where existing models may require refinement. The paper concludes with actionable recommendations designed to strengthen cybersecurity governance and enhance the overall cyber resilience of the global electric power ecosystem.

2. Background and Literature Review

This section provides the conceptual and empirical foundations necessary to understand the cybersecurity posture of the electric power sector. It examines the role of critical infrastructure, the evolving cyber-threat landscape in ICS/SCADA environments and the historical progression of major cyber incidents targeting power systems. Also, it synthesizes insights from recent survey literature and identifies persistent research gaps, thereby establishing the rationale for a maturity-based assessment approach in the remainder of the study.

2.1. Critical Infrastructure and the Electric Power Sector

Critical Infrastructure (CI) encompasses the essential systems, assets and networks whose incapacitation would have a weakening impact on national security, economic stability, public health and safety [3]. Among these, the electric power sector is uniquely critical due to its interdependency with other infrastructure domains. Research consistently highlights that energy systems are both the enablers and the most interdependent components of national infrastructure ecosystems [4]. Consequently, disruptions in electricity generation or transmission can propagate across other sectors, amplifying the societal and economic consequences of cyber incidents.

2.2. Cyber Threat Landscape in ICS/SCADA Environments

The rapid digital transformation of the energy sector has led to the integration of digital communication technologies, remote monitoring and automation within Operational Technology (OT) environments. While this evolution has improved system efficiency and responsiveness, it has simultaneously increased exposure to cyber threats [5]. Industrial Control Systems (ICS) and Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) networks, which have been designed originally for reliability and availability rather than security, often operate with limited authentication, outdated encryption and inadequate patch management mechanisms [6].

Scholars and practitioners alike have emphasized that legacy infrastructure, combined with a lack of network segmentation and persistent use of insecure communication protocols (e.g., Modbus, DNP3), creates a fertile ground for adversarial exploitation [7]. Threat actors ranging from state-sponsored Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) to cybercriminal organizations and hacktivist groups have increasingly targeted these vulnerabilities to disrupt or manipulate critical operations [8].

2.3. Evolution of Cyber Attacks Against Power Systems

Historical analysis reveals a steady escalation in both the frequency and sophistication of cyber attacks on power systems over the past two decades. The Stuxnet worm (2010) demonstrated the feasibility of using malware to cause physical damage to industrial processes, marking a paradigm shift in cyber-physical warfare [9]. Subsequent incidents such as the Shamoon attack (2012), the Ukrainian power grid intrusions (2015 and 2016), and the Industroyer2 malware (2022) have progressively exploited the IT-OT interface to compromise operational continuity and data integrity [10].

Recent literature has increasingly focused on assessing these events through structured frameworks that enable a deeper understanding of threat vectors, mitigation strategies, and resilience-building mechanisms [2]. These studies highlight the necessity of transitioning from reactive defense mechanisms to proactive, maturity-based cybersecurity governance models.

2.3.1. Insights from Recent Survey Literature

Over the past decade, a substantial corpus of survey-based research has emerged to characterize cyber threats, defensive postures and governance mechanisms across Industrial Control Systems (ICS) and smart grid environments.

Bhamare et al. (2020) and Yadav and Paul (2021) highlight those contemporary studies have transitioned from descriptive, incident-focused analyses toward structured frameworks that quantify detection maturity, assess defense depth, and integrate organizational governance [1,2]. This evolution signifies a conceptual shift: cybersecurity in critical infrastructures is no longer regarded as a purely technical function but as a dynamic, measurable component of systemic resilience.

Ahmadian et al. (2020) developed a hierarchical taxonomic framework to categorize over 250 cyber incidents targeting ICS assets according to their attack vectors, operational domains and mitigation responses [11]. Their empirical work demonstrated that the majority of high-impact events could have been mitigated through baseline maturity controls such as network segmentation and patch management illustrating how data-driven taxonomies directly inform the design of maturity models.

Complementing this, El Mrabet et al. (2018) extended the traditional confidentiality–integrity–availability (CIA) paradigm by introducing accountability as a fourth dimension, linking traceability and governance to resilience engineering [12]. Together, these surveys illustrate a paradigmatic realignment in critical-infrastructure cybersecurity research from reactive intrusion response toward proactive, governance-centered maturity modeling. Rather than isolating discrete vulnerabilities, recent scholarship emphasizes cross-domain situational awareness, supply-chain assurance, and adaptive learning processes within organizations.

This growing body of evidence supports the use of integrated frameworks such as NIST CSF 2.0, the ENISA NIS2 Directive and C2M2, which help enable ongoing assessment, capability development, and improved resilience in the electric power sector.

2.3.2. Gaps and Challenges in Existing Research

Despite the extensive growth of literature on ICS and smart grid cybersecurity, several critical gaps persist in current research and practice. First, most survey studies remain descriptive, focusing on threat typologies or attack taxonomies without systematically linking them to operational governance or maturity-level evaluation. While frameworks such as NIST CSF and C2M2 are frequently referenced, empirical validation within real-world critical infrastructure environments remains limited [13].

Secondly, the majority of comparative analyses emphasize technical mitigations such as intrusion detection or encryption—over organizational preparedness and cross-sector coordination. This imbalance underscores the continued separation between Information Technology (IT) and Operational Technology (OT) domains in both academic and operational contexts. As noted by authors [14,15], resilience-building initiatives often lack standardized metrics to evaluate human factors, supply chain dependencies or cascading effects.

Finally, few studies integrate longitudinal perspectives that assess how repeated exposure to cyber incidents influences institutional learning and maturity progression. The absence of such continuity-based evaluation limits our understanding of how resilience evolves over time within the energy sector.

Addressing these limitations requires harmonizing empirical taxonomies, maturity frameworks, and resilience engineering principles under a unified research agenda. This convergence can transform maturity assessment from a compliance exercise into a continuous improvement process linking technical, organizational, and policy dimensions of cybersecurity in the electric power sector.

In response to these gaps, the present study aims to operationalize this convergence by systematically mapping historical cyber incidents in the electric power sector against the control objectives and maturity indicators defined in leading cybersecurity frameworks (NIST CSF 2.0, ENISA NIS2, and C2M2). By doing so, it seeks to determine which incidents could have been mitigated through maturity-based governance, identify areas insufficiently covered by existing standards and propose integrative recommendations for strengthening resilience-oriented cybersecurity architectures.

2.4. Cybersecurity Maturity Frameworks and Their Relevance

Several cybersecurity maturity models have been proposed to guide the protection and governance of critical infrastructures. The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0 provides a structured approach for identifying, protecting, detecting, responding to and recovering from cyber incidents [16]. The ENISA NIS2 Directive Risk Management Measures extend this approach by emphasizing organizational accountability, incident reporting and risk-based resource allocation within the European regulatory context. Meanwhile, the Cybersecurity Risk Foundation (CRF) Maturity Model focuses on adaptive risk management and the continuous improvement of cybersecurity postures across organizational hierarchies [13]. Complementing these, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (C2M2) offers a sector-specific implementation framework that enables energy organizations to assess and enhance their cybersecurity capabilities through measurable maturity indicators [17]. This study integrates these frameworks to evaluate their practical applicability to real-world cyber incidents targeting electric power infrastructures. By mapping historical attacks against the controls and capabilities outlined in these models, the paper seeks to determine the extent to which maturity-based governance could have mitigated or prevented these events.

3. Research Design and Methodology

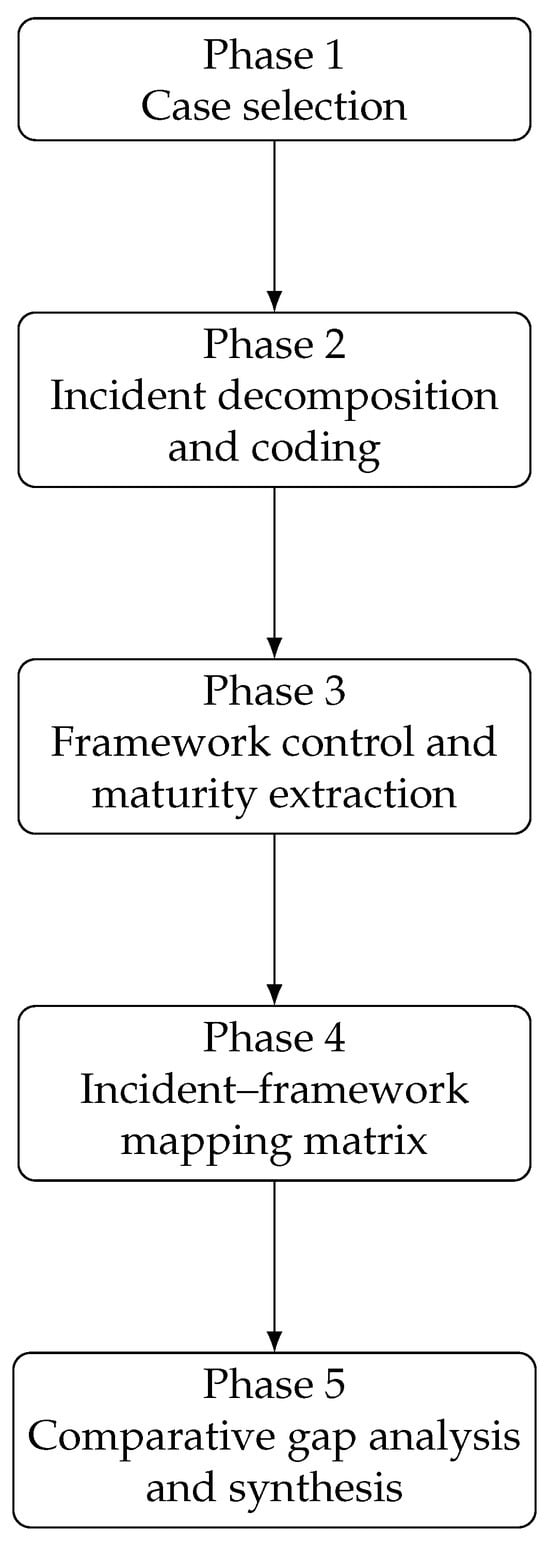

This study employs a structured, multi-stage qualitative research design to evaluate how major cyber incidents affecting industrial control environments intersect with, and expose limitations in, leading cybersecurity maturity frameworks and technical standards. The overall workflow comprises five sequential phases: (1) selection of representative cyber incidents, (2) decomposition and coding of each incident, (3) extraction of relevant controls and maturity indicators from the selected frameworks and standards, (4) rule-based mapping between incident techniques and framework controls and (5) comparative gap analysis and synthesis of findings. Figure 1 provides an overview of the analytical process, while Table 1 illustrates the resulting incident–framework mapping structure.

Figure 1.

Overview of the research design and methodology used to relate cyber incidents to cybersecurity maturity frameworks and technical standards.

Table 1.

Excerpt of the incident–framework mapping matrix highlighting how selected attacks align with representative controls from maturity frameworks and technical standards.

3.1. Phase 1: Selection of Cyber Incidents

The case studies presented in this paper (Section 4) were selected according to the following criteria:

- direct relevance to electric power generation, transmission or closely related industrial control environments;

- availability of credible technical, forensic or governmental reporting enabling detailed reconstruction of the attack sequence;

- representation of diverse attack vectors, including IT intrusion, OT protocol manipulation, wiper malware and hybrid IT/OT campaigns;

- demonstrated operational impact or clear potential to affect critical infrastructure resilience at national or sectoral level.

Based on these criteria, five major incidents were chosen: Stuxnet (2010), Shamoon (2012), the 2015 and 2016 Ukrainian power grid attacks and Industroyer2 (2022). Together, they span more than a decade of adversarial evolution and capture distinct modalities of cyber-physical disruption.

3.2. Phase 2: Incident Decomposition and Coding

In the second phase, each incident was decomposed into a set of structured elements describing:

- the initial access vectors (e.g., spear-phishing, supply-chain compromise, removable media);

- the attacker’s progression across IT and OT networks (e.g., lateral movement, credential theft, pivoting to SCADA/ICS segments);

- the techniques used to manipulate or impact industrial processes (e.g., protocol abuse, PLC reprogramming, relay manipulation);

- the operational consequences (e.g., loss of view, loss of control, data destruction, physical damage);

- the observed or reported mitigation and response measures.

These elements were then coded using a combination of widely adopted analytical models for cyber operations (such as the Cyber Kill Chain and tactic–technique taxonomies for industrial environments). The goal of this coding step was not to propose a new taxonomy, but to normalize the description of heterogeneous incidents so that they could be systematically compared and aligned with framework requirements.

3.3. Phase 3: Extraction of Framework Controls and Maturity Indicators

The third phase focused on the cybersecurity maturity frameworks and technical standards examined in this study, namely:

- NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0;

- ENISA NIS2 Directive Risk Management Measures;

- Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (C2M2);

- Cybersecurity Risk Foundation (CRF) Maturity Model;

- NIST SP 800-82 (Guide to Industrial Control Systems Security);

- IEC 62443 series for industrial automation and control systems.

For each instrument, the analysis extracted those control families, subcategories, risk-management obligations and maturity indicators that are directly relevant to:

- asset identification and inventory management in OT environments;

- network architecture, segmentation, and secure remote access;

- vulnerability and configuration management for ICS/SCADA components;

- monitoring, anomaly detection, and incident response;

- backup, recovery, and resilience planning for critical functions.

This resulted in a consolidated control baseline reflecting both governance-level expectations (e.g., NIST CSF, NIS2, C2M2, CRF) and OT-specific engineering measures (NIST SP 800-82, IEC 62443).

3.4. Phase 4: Incident–Framework Mapping Procedure

In the fourth phase, a rule-based mapping was performed between coded incident techniques and the extracted framework controls. The mapping followed three guiding principles:

- A control was considered preventive if, when fully implemented, it would likely have interrupted or significantly constrained the execution of a given attack step (e.g., network segmentation blocking pivot from IT to OT).

- A control was considered detective if it enabled timely identification of anomalous activity associated with the attack (e.g., monitoring of OT protocol commands, integrity checks on PLC logic).

- A control was considered resilience-oriented if it reduced the operational impact or time-to-recovery (e.g., tested backup and restoration procedures, black-start capabilities, manual fallback operation).

For each incident, the coded attack path was examined step by step, and the relevant controls from NIST CSF 2.0, NIS2, C2M2, CRF, NIST SP 800-82 and IEC 62443 were identified. These relationships were then recorded in a binary matrix of the form Incident × Control, where a value of 1 indicates that the given control is explicitly applicable to, and would have mitigated or detected, the corresponding attack element, and 0 otherwise.

3.5. Phase 5: Comparative Gap Analysis and Synthesis

In the final phase, the incident–framework matrix was aggregated to identify recurring strengths and weaknesses across the examined instruments:

- Controls that consistently mapped to multiple incidents were interpreted as core enablers of resilience (e.g., network segmentation, robust identity and access management, continuous monitoring).

- Controls that were weakly represented, missing or only implicitly covered in one or more frameworks were flagged as potential gaps, particularly when repeatedly exploited across incidents (e.g., hybrid IT/OT campaign readiness, human-factor resilience, systemic grid-level risk).

- Where controls existed but required higher maturity levels (e.g., advanced C2M2 domains, full implementation of NIS2 governance measures), the analysis evaluated whether realistic adoption levels in typical utilities would have been sufficient to mitigate the attack.

The results of this gap analysis directly inform the retrospective discussion on framework effectiveness and the proposed directions for evolving toward more resilience-oriented maturity models presented in the subsequent sections.

3.6. Incident–Framework Mapping Matrix

Table 1 summarizes an excerpt of the mapping between the selected case studies and representative controls from the evaluated frameworks and standards. The table is not intended to be exhaustive; rather, it illustrates how specific attack techniques observed in the incidents align with preventive, detective and resilience-oriented measures prescribed by NIST CSF 2.0, NIS2, C2M2, IEC 62443, and NIST SP 800-82. The full mapping was used to derive the comparative findings discussed later in this paper.

4. Case Studies: Major Cyberattacks on Industrial Control Systems

Critical Infrastructure (CI) encompasses the essential assets, systems, and networks, whether physical or virtual, whose disruption or destruction would severely compromise national security, economic stability, public health or safety. Within this hierarchy, the electric power sector is universally classified as a Tier 1 CI, given that its continuous and reliable operation underpins the functionality of all other sectors and services [23].

The economic and societal ramifications of power outages are profound. Beyond the direct financial losses incurred through infrastructure damage and utility downtime, the secondary effects (such as disrupted industrial production, compromised supply chains and volatility in financial markets) can escalate into large-scale economic instability. From a societal perspective, extended power disruptions may impede emergency response operations, disrupt communications and endanger public health through the loss of critical services, including hospital operations and water treatment facilities.

While the increasing digitalization and interconnectivity of modern power grids have enhanced operational efficiency and situational awareness, they have also expanded the cyber threat landscape. The complex interdependencies between Information Technology (IT) and Operational Technology (OT) systems have created a vast and dynamic attack surface. Consequently, power systems have become high-value targets for state-sponsored threat actors and other sophisticated adversaries seeking to exploit vulnerabilities within Industrial Control Systems (ICS) and Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) environments [24].

4.1. Ukrainian Power Grid Attack (2015)

The cyberattack on Ukraine’s power grid in December 2015 represents a pivotal moment in the history of industrial cybersecurity, marking the first publicly confirmed incident in which a cyber operation directly caused a large-scale power outage [8]. This event not only demonstrated the growing sophistication of adversaries targeting Operational Technology (OT) environments but also underscored the systemic vulnerabilities present within interconnected Industrial Control Systems (ICS) and Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) networks.

The primary objective of the attackers was to disrupt power supply operations and exhibit their technical capability to compromise critical infrastructure. The intrusion began with a spear-phishing campaign directed at employees of regional power distribution companies, through which the BlackEnergy malware variant was deployed. Once the attackers gained an initial foothold within the corporate IT network, they executed lateral movement techniques to infiltrate the OT environment, ultimately achieving unauthorized control over SCADA systems [25].

The adversaries employed a combination of spear phishing, lateral movement, SCADA manipulation, and denial-of-service (DoS) attacks. Using legitimate operator credentials, they remotely opened circuit breakers, effectively disconnecting substations from the grid. In parallel, they launched DoS attacks to disrupt monitoring capabilities, thereby obscuring system visibility and impeding operators’ situational awareness.

The operational consequences were severe: approximately 225,000 customers across three regional power companies experienced prolonged outages lasting several hours. Beyond the immediate disruption, attackers also wiped critical system components, deliberately impeding restoration efforts and prolonging the recovery process [10].

Restoration of services ultimately required manual operation of substations, illustrating the sector’s dependency on legacy control mechanisms and the absence of robust contingency measures [26]. Post-incident analyses emphasized the urgent necessity for network segmentation-to ensure strict separation between IT and OT domains-and the implementation of comprehensive access control policies to mitigate unauthorized lateral movement within industrial networks.

4.2. Ukrainian Power Grid Attack (2016)—Industroyer/CRASHOVERRIDE

In December 2016, one year after the first Ukrainian power grid incident, a second and more sophisticated cyberattack targeted Ukraine’s electricity infrastructure. This operation employed the Industroyer malware (also known as CRASHOVERRIDE), a highly modular and adaptable framework specifically engineered to disrupt industrial control environments. The attack represented a significant evolution in threat capability, as it was the first publicly known malware designed to directly communicate using industrial control protocols [27].

The primary objective of the attackers was to inflict long-term damage and sustain disruption within power transmission networks. Industroyer’s architecture incorporated multiple payloads capable of interacting natively with critical industrial communication standards enabling it to issue legitimate commands to substation equipment. This capability allowed the malware to manipulate switches and circuit breakers autonomously, effectively taking control of substation operations.

The attack leveraged a combination of protocol-specific exploitation, suspected supply chain compromise as an initial infection vector, wiper malware (KillDisk) to prevent system recovery and targeted relay manipulation to cause physical disruption. Although the resulting power outage in Kyiv was relatively brief, the incident’s broader significance lay in its demonstration of malware capable of “speaking” the operational language of industrial devices effectively functioning as a “circuit breaker” for critical infrastructure systems [28].

The 2016 Industroyer attack underscored the escalating sophistication of adversaries targeting ICS/SCADA networks and highlighted the urgent need for enhanced deep packet inspection of OT communication protocols, as well as rigorous supply chain risk management practices to authenticate third-party software, firmware and hardware components. These findings reaffirmed the necessity of continuous monitoring, anomaly detection, and the adoption of proactive cybersecurity governance models within the energy sector.

4.3. Stuxnet (2010)

Although not directly targeting the electric power sector, Stuxnet stands as the seminal example of a cyber-physical weapon and serves as a critical reference point for understanding the vulnerabilities of Industrial Control Systems (ICS) environments. The malware specifically targeted the uranium enrichment facility at Natanz, Iran, marking a transformative moment in the evolution of cyber warfare by bridging the gap between digital intrusion and physical destruction [8].

The principal objective of Stuxnet was the physical degradation of centrifuge equipment through the manipulation of their operational parameters, particularly their rotational speed. To achieve this, the malware employed an exceptionally sophisticated architecture that exploited four zero-day vulnerabilities and targeted specific Siemens programmable logic controllers (PLCs) responsible for managing the centrifuges. Once introduced into the network, likely through an infected USB device, it propagated autonomously, reprogramming PLC logic while simultaneously deploying man-in-the-middle (MITM) techniques to present falsified data to system operators. This ensured that the sabotage remained undetected until physical malfunction became inevitable.

Stuxnet’s attack methodology incorporated a combination of zero-day exploits, PLC reprogramming, air-gap jumping, and data manipulation tactics. The result was the physical destruction of approximately 1000 centrifuges, which significantly delayed Iran’s nuclear enrichment activities. This event provided irrefutable evidence that cyberattacks could produce tangible, real-world consequences, thereby redefining the boundaries of both cyber defense and national security strategy [29].

The implications of Stuxnet extended far beyond its immediate target. The incident exposed the inherent vulnerabilities of “air-gapped” industrial networks, challenging long-held assumptions regarding their immunity to cyber threats. In its aftermath, cybersecurity practitioners and policymakers alike recognized the need for a comprehensive re-evaluation of vulnerability management, supply chain assurance and physical access control mechanisms, even within isolated operational environments.

4.4. Industroyer2 (2022)

The 2022 Industroyer2 attack marked a renewed attempt to disrupt Ukraine’s high-voltage power infrastructure, underscoring both the persistence and the evolution of cyber threats targeting critical energy systems. Building on the legacy of the 2016 Industroyer incident, this operation demonstrated the adversaries’ capacity to adapt existing malware to new operational environments while increasing both speed and destructive potential [30].

The attackers’ primary objective was the disruption of power transmission and the infliction of potential physical damage to substation equipment. Industroyer2 constituted a refined and more agile version of the original Industroyer malware, capable of interfacing with modernized grid systems and exploiting updated industrial control protocols. The malware was deployed in tandem with the CaddyWiper wiper malware, designed to erase data and impede post-incident recovery efforts, thereby amplifying the operational impact of the attack.

The operation featured a combination of tailored ICS-specific malware, scheduled execution mechanisms (programmed to activate at a predetermined time) and advanced persistence capabilities that allowed the attackers to maintain covert access within compromised environments [31]. While the attack was ultimately detected and mitigated before causing large-scale disruption, forensic analyses revealed its potential to inflict significant harm had it executed as planned.

The swift and effective containment of the attack was largely attributed to proactive threat intelligence, early detection and the rapid deployment of incident response teams coordinated by Ukrainian cybersecurity authorities and international partners [32]. Moreover, the response benefited from the strategic improvements implemented after the 2015 and 2016 power grid attacks, particularly the establishment of robust incident response protocols and continuous monitoring frameworks.

The Industroyer2 incident reaffirmed that persistent adversaries continue to refine their methods for targeting critical infrastructure, and it highlighted the ongoing necessity of real-time network visibility, cross-sector threat intelligence sharing, and resilient recovery planning to ensure the operational continuity of power systems under cyber duress.

4.5. Shamoon (2012)

Although the Shamoon attack (2012) primarily targeted the oil and gas sector, specifically Saudi Aramco, it remains a critical reference point in industrial cybersecurity due to its employment of wiper malware, a class of destructive tools capable of erasing data and crippling operational continuity across any form of critical infrastructure (CI). The incident revealed how data destruction alone, without direct manipulation of control systems, can produce cascading operational and economic consequences comparable to physical sabotage [33].

The objective of Shamoon was data destruction and large-scale operational disruption. The malware was engineered to overwrite the Master Boot Record (MBR) of infected systems, effectively rendering them inoperable while simultaneously erasing vital business and operational data [34]. In doing so, it targeted the corporate network layer rather than the industrial control systems directly-yet the resulting downtime had tangible effects on physical operations and service delivery.

From a technical perspective, the attack leveraged wiper malware (Shamoon) to overwrite storage sectors and corrupt file systems, combined with a network compromise that enabled its rapid spread across internal domains. Evidence also suggested the potential involvement of an insider threat during the initial compromise, underscoring the vulnerability of trusted access points in air-gapped or segmented environments.

The impact was catastrophic: over 30,000 workstations were permanently disabled, leading to an unprecedented operational shutdown [35]. Saudi Aramco was forced to revert to manual operations for extended periods, severely impairing both productivity and communications. The restoration process required weeks of system rebuilding and highlighted the systemic risks associated with inadequate network segmentation and backup infrastructure.

In terms of mitigation, the Shamoon incident underscored the strategic importance of robust data backup and recovery architectures, particularly air-gapped backup systems resistant to network-based propagation [36]. Furthermore, it reinforced the value of comprehensive endpoint protection, continuous network behavior monitoring and employee awareness programs aimed at detecting insider anomalies or credential misuse.

Ultimately, Shamoon served as a seminal example of data-centric cyber warfare, illustrating that destructive intent executed at the informational layer can yield operational paralysis comparable to kinetic attacks [37]. Its legacy continues to inform the development of advanced resilience frameworks within both the energy sector and broader industrial ecosystems.

4.6. Analytical Summary: Evolution of Cyber Threats to Critical Infrastructure

The analysis of major cyber incidents targeting critical infrastructure systems between 2010 and 2022 reveals a consistent escalation in both the sophistication and intent of adversarial operations. Early cyber-physical attacks such as Stuxnet (2010) demonstrated that malicious code could transcend the digital domain to inflict physical damage on industrial control systems (ICS). Stuxnet’s use of zero-day exploits, PLC reprogramming and air-gap jumping fundamentally altered the security paradigm for operational technology (OT) environments by exposing the fallacy of presumed isolation [38,39].

Subsequent incidents, notably the Ukrainian power grid attacks (2015–2016) and Industroyer/CRASHOVERRIDE (2016), marked a shift toward intentional disruption of civilian power systems, leveraging malware capable of communicating through industrial protocols such as IEC 60870-5-101/104 and IEC 61850 [35]. These attacks underscored the growing convergence of cyber warfare and critical infrastructure, as threat actors demonstrated not only technical capability but also a strategic intent to undermine national stability and public trust [34].

The Shamoon (2012) attack on Saudi Aramco and its later variants represented another dimension of this evolution, emphasizing data destruction and operational paralysis through wiper malware [40]. While not directly targeting electric power systems, Shamoon’s methodology illustrated the vulnerability of large-scale industrial enterprises to insider-assisted infiltration and destructive payloads, reinforcing the necessity of endpoint protection and data resilience strategies [41].

More recently, the Industroyer2 (2022) incident reaffirmed the persistence and adaptive evolution of threat actors in targeting the energy sector. The attack’s integration of CaddyWiper and scheduled execution mechanisms reflected an enhanced focus on timing, coordination, and persistence hallmarks of state-sponsored advanced persistent threats (APTs) [42]. Unlike earlier attacks, however, Industroyer2 was mitigated before significant damage occurred, highlighting the tangible benefits of continuous threat intelligence, rapid incident response, and mature cybersecurity governance frameworks developed in the aftermath of prior breaches [25].

Collectively, these cases demonstrate that the threat landscape for critical infrastructure has evolved from isolated, experimental attacks to systematic, multi-vector operations aimed at both disruption and deterrence. The convergence of IT and OT domains, the use of supply chain compromise as an initial vector, and the increasing modularity of malware tools suggest that future attacks will be characterized by hybrid tactics combining espionage, sabotage, and psychological impact [28].

From a defensive perspective, the progression of these attacks underscores the urgent necessity for integrated cybersecurity architectures that encompass network segmentation, continuous monitoring of industrial protocols, and cross-sector collaboration. Furthermore, the incidents collectively reinforce the centrality of resilience the capacity not only to prevent attacks but also to sustain and recover critical operations amid compromise [43]. The maturation of defense practices, informed by these lessons, constitutes a pivotal step toward securing the world’s increasingly digital and interconnected power systems.

5. Cybersecurity Maturity Frameworks on Electric Power Grids

As the digital transformation of electric power systems accelerates, the convergence of Information Technology and Operational Technology has brought about unprecedented efficiencies and equally unprecedented risks. Critical Infrastructure, particularly electric power grids, now relies on complex, interconnected networks that are increasingly exposed to cyber threats capable of causing widespread physical and economic disruption.

To manage these risks effectively, a structured and repeatable approach to cybersecurity governance and improvement is essential [44]. Cybersecurity maturity frameworks provide this structure by defining measurable stages of preparedness, control implementation, and risk management integration. These frameworks enable organizations to evaluate their cybersecurity posture, identify gaps and establish a roadmap toward enhanced resilience.

This section provides an in-depth analysis of five key frameworks and policy instruments relevant to electric power grids: the NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0, the ENISA NIS2 Directive Risk Management Measures, the Cybersecurity Risk Foundation (CRF) Maturity Model, the Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (C2M2) and the U.S DOE’s “21 Steps to Improve Cyber Security of SCADA Networks”. Each framework offers distinct advantages and challenges when applied to industrial control systems (ICS) and supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) environments.

5.1. NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0

The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0 represents one of the most comprehensive and widely adopted models for managing cybersecurity risks across both public and private sectors. Developed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, it provides a flexible structure based on six core functions: Govern, Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond and Recover [45]. The ’Govern’ function, newly introduced in version 2.0, emphasizes leadership accountability and continuous governance-critical components in achieving cyber resilience for power utilities.

For electric power systems, the CSF provides a bridge between IT and OT security domains, enabling operators to align risk management with operational reliability. It promotes the implementation of tailored controls across SCADA networks, including network segmentation, anomaly detection and incident response playbooks. By focusing on outcomes rather than prescriptive controls, NIST CSF enables utilities to adapt to the evolving threat landscape while maintaining compliance with sector-specific standards such as IEC 62443.

5.2. ENISA/NIS2 Directive

The European Union’s NIS2 Directive (Directive (EU) 2022/2555) establishes a comprehensive and legally binding framework for enhancing cybersecurity resilience across critical sectors, including energy, transportation, healthcare and digital infrastructure. As an evolution of the original NIS Directive, NIS2 mandates that operators of essential and important entities implement robust measures for risk management, incident handling, business continuity and supply chain security, thereby reinforcing a culture of proactive cyber risk governance [46]. Supervised and guided by the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA), the directive extends accountability to the executive level, framing cybersecurity not merely as a technical concern but as a core component of corporate governance and operational reliability.

In the context of electric power systems, NIS2,supported by ENISA’s sector-specific guidelines, advocates for network segmentation of substations, continuous anomaly detection, secure remote access management and rigorous third-party risk assessments. Although the directive is legally binding only within EU Member States, its structured approach to resilience and cross-border information sharing serves as a reference model for non-EU jurisdictions and energy operators worldwide seeking to enhance the security and integrity of their critical infrastructure. Ultimately, NIS2’s harmonized reporting obligations and accountability mechanisms aim to improve transparency, ensure timely incident response, and mitigate the risk of cascading failures across interconnected energy networks.

5.3. Cybersecurity Risk Foundation (CRF) Maturity Model

The Cybersecurity Risk Foundation (CRF) Maturity Model offers a practical, risk-based approach to cybersecurity management through measurable safeguards and prioritized maturity levels. It emphasizes operational feasibility and outcome-driven improvements rather than checklist compliance, making it adaptable across various industrial environments.

In the context of electric utilities, the CRF Maturity Model can help standardize security policies and operational practices while promoting awareness among both IT and OT personnel. Its iterative improvement model supports long-term resilience, aligning with the continuous operation cycles of power plants. The model’s focus on pragmatic risk reduction makes it suitable for utilities with limited resources seeking to establish a structured cybersecurity program.

5.4. Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (C2M2)

Developed by the U.S. Department of Energy, the Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (C2M2) provides a sector-specific approach for critical infrastructure operators to evaluate and improve cybersecurity capabilities. The model is structured into ten domains, ranging from Risk Management to Incident Response, each mapped across maturity levels from partial to adaptive [17].

For electric utilities, C2M2 offers practical guidance for strengthening ICS and SCADA security, with domains explicitly covering asset management, configuration control and situational awareness. It enables utilities to benchmark current capabilities and plan progressive improvements, ensuring alignment with national standards and best practices.

After examining the principal cybersecurity maturity frameworks relevant to the energy sector, their comparative strengths and limitations can be summarized as shown in Table 2. Table 2 provides a comparative overview of key cybersecurity frameworks and technical standards relevant to the protection of electric power systems, illustrating their complementary governance and operational roles.

Table 2.

Comparative Summary of Cybersecurity Frameworks and Technical Standards.

5.5. Complementary Technical Standards

While these frameworks provide strategic and governance-level guidance, their practical implementation in industrial control environments requires alignment with technical standards such as NIST SP 800-82 and IEC 62443, which translate policy objectives into enforceable control mechanisms.

5.5.1. Historical Foundations: DOE’s “21 Steps to Improve Cyber Security of SCADA Networks”

Before examining the contemporary technical standards, it is essential to acknowledge the early foundations that shaped the evolution of cybersecurity practices in industrial control systems. One of the earliest initiatives to address cybersecurity within industrial control environments emerged from the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) 2002 publication “21 Steps to Improve Cyber Security of SCADA Networks.” [47]. This document represented a pivotal transition from general policy guidance to a structured set of technical recommendations for securing SCADA and ICS architectures. By emphasizing network isolation, authentication management, access limitation, and periodic auditing, the 21 Steps provided actionable measures that directly informed later U.S. cybersecurity policies and standards.

Although conceived as a national-level guidance, its influence extended far beyond the United States, forming the conceptual bridge between early critical-infrastructure protection policies (such as PPD-21) and comprehensive technical standards like NIST SP 800-82 and IEC 62443. The document’s enduring relevance lies in its operational focus it articulated practical steps that transformed policy intent into engineering practice, effectively laying the groundwork for the layered “defense-in-depth” principles now embedded in modern OT security frameworks.

5.5.2. NIST SP 800-82 and IEC 62443 Technical Standards

Building upon the foundations established by the 21 Steps framework, NIST SP 800-82 (Guide to Industrial Control Systems (ICS) Security) and IEC 62443 collectively define the global benchmark for securing operational-technology environments. These standards operationalize cybersecurity maturity models by translating organizational-level objectives, such as those expressed in NIS2, NIST CSF, and C2M2, into prescriptive control requirements for system architecture, communication networks, and industrial assets.

NIST SP 800-82 focuses on practical implementation guidance for U.S. critical-infrastructure operators, detailing risk-based controls, defense-in-depth design and integration of IT-OT security practices [19]. IEC 62443, developed under the International Electrotechnical Commission, provides a modular, lifecycle-based approach applicable across global energy and manufacturing sectors, introducing standardized security levels and certification pathways [18]. Together, these standards form the technical backbone of modern critical-infrastructure protection, complementing governance frameworks with enforceable engineering controls that enhance the resilience of electric power systems.

6. “Discussion: Framework Effectiveness in Retrospect”

While the preceding case studies illustrate the escalating sophistication of cyberattacks targeting critical infrastructures, a reflective analysis reveals that many of these incidents exploited weaknesses that existing cybersecurity frameworks were designed (or could have been adapted) to address. The extent to which frameworks such as NIST CSF, C2M2 and NIS2 could have mitigated these attacks offers valuable insight into their practical effectiveness and residual gaps.

Evaluating these frameworks retrospectively not only underscores their strengths in risk governance and response coordination but also exposes persistent blind spots in supply chain dependencies, operational-technology (OT) integration and adversarial adaptation mechanisms.

6.1. Contextual Overview and Rationale

Before presenting the detailed retrospective evaluation, it is important to clarify the methodological rationale for the structure of this Discussion section. The analysis undertaken in this study synthesizes insights from both the case studies and the examined cybersecurity maturity frameworks. Given the complexity of hybrid cyber–physical attacks and the multidimensional nature of electric power system cybersecurity, the Discussion is intentionally organized into layered components: (i) a high-level contextual reflection, (ii) a retrospective mapping of incidents to framework controls and (iii) a forward-looking assessment of structural gaps and future needs.

This structure was chosen to avoid oversimplifying the interplay between governance frameworks, technical standards and real-world attack dynamics. While a more condensed Discussion could have been provided, doing so would risk overlooking the nuanced distinctions between framework capabilities and the operational realities observed in the case studies. For this reason, the section proceeds from general insights toward increasingly granular analysis, ensuring a coherent progression without fragmenting the narrative.

Furthermore, several aspects raised in the reviewer comments, such as the explicit mapping between incidents and maturity models, the discussion of gaps, and the emphasis on resilience, were already considered during the design of the Discussion. These elements were intentionally expanded, not to overcomplicate the section, but to ensure that the article makes a meaningful contribution to the literature by bridging practical case evidence with the theoretical foundations of maturity frameworks. In particular, the sub-sections that follow highlight where existing frameworks align with historical failure points and where they lack the depth required to address emerging hybrid and cross-domain threats.

This brief contextual clarification is introduced to support the reader’s understanding of the Discussion flow and to reinforce the reasoning behind the analytical structure that follows.

6.2. Retrospective Analysis: Potential Prevention Through Framework Adoption

The reviewed incidents ranging from Stuxnet (2010) and the Ukraine Power Grid Attacks (2015–2016) to Shamoon (2012) and Industroyer2 (2022) demonstrate a recurring pattern of vulnerabilities rooted in insufficient network segmentation, outdated software and fragmented governance between Information Technology (IT) and Operational Technology (OT) domains. Retrospectively analyzing these events through the lens of existing cybersecurity frameworks reveals that several critical weaknesses could have been mitigated or entirely prevented if the relevant maturity models and standards had been systematically implemented.

For instance, the Stuxnet operation exploited the absence of asset identification and supply chain verification processes that are explicitly mandated under the “Identify” and “Protect” functions of the NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF). The deployment of IEC 62443-3-3 controls (particularly those addressing network segmentation, system integrity, and least privilege) could have substantially reduced the malware’s ability to propagate between engineering workstations and programmable logic controllers (PLCs). Likewise, the C2M2 framework’s maturity indicators for configuration management and vulnerability remediation align directly with the failure points observed in this case.

In the 2015 Ukraine power grid attacks, adversaries leveraged inadequate incident response coordination and limited situational awareness across distributed control centers. The NIS2 Directive’s emphasis on incident reporting timelines, executive accountability and cross-sector coordination directly addresses such governance deficiencies. Moreover, if the NIST CSF’s “Detect” and “Respond” functions which are supported by continuous monitoring and anomaly detection mechanisms as outlined in NIST SP 800-82, had been institutionalized, lateral movement across substations could likely have been identified earlier, reducing operational disruption. The 2012 Shamoon attack, which targeted the Saudi Aramco corporate network, underscores the risks associated with weak segmentation between enterprise IT environments and operational networks. The absence of business continuity planning and backup strategies exacerbated downtime and data loss. Application of C2M2’s maturity domains related to risk management and resilience planning, along with ISO/IEC 27001 and IEC 62443-2-1 requirements for security management systems, could have ensured faster recovery and limited operational impact.

Finally, the emergence of modular malware such as Industroyer2 reflects an evolution toward adversarial adaptability, an area where current frameworks provide only partial coverage. Although NIST CSF 2.0 introduces the new “Govern” function to integrate threat intelligence and accountability into enterprise decision-making, the adaptive feedback mechanisms required for predictive defense remain underdeveloped. This suggests that while existing frameworks could have prevented many legacy incidents, future threats will demand more dynamic, intelligence-driven, and behaviorally adaptive maturity models that continuously evolve with the threat landscape.

6.3. Framework Gaps and Future Directions

The retrospective analysis of major cyber incidents against electric power infrastructures suggests that many of the exploited weaknesses were, in principle, addressable by existing maturity models and technical standards. However, the same analysis also reveals that these frameworks are not fully aligned with the evolving threat landscape.

Even where NIST CSF, C2M2, NIS2, NIST SP 800-82 and IEC 62443 provide relevant controls, their application is often fragmented, static or insufficiently tailored to hybrid and cross-domain attacks. This section critically examines the residual gaps that would likely have persisted even under full nominal compliance and outlines directions for evolving maturity models and standards to better protect electric power systems.

6.3.1. Limitations of Current Frameworks in Addressing Hybrid Threats

First, current frameworks only partially capture the hybrid nature of contemporary attacks on power grids. The case studies show that adversaries increasingly combine IT intrusion, OT manipulation, supply chain compromise and psychological impact (e.g., public fear, political signaling) within a single campaign. While NIST CSF and NIS2 acknowledge supply chain risk and IT–OT convergence at a conceptual level, they do not provide sufficiently granular guidance or metrics for assessing an organization’s readiness against multi-vector, state-aligned operations. Similarly, C2M2 measures capability across domains, but its scoring remains largely inward-looking and does not explicitly model adversarial adaptation, coordinated campaigns or the interplay between technical and cognitive effects on operators and the public.

In practical terms, this means that, even if these frameworks had been fully adopted prior to incidents such as the Ukraine power grid attacks or Shamoon, they might have reduced the probability of compromise but not necessarily the strategic impact of a well-resourced, multi-phase campaign. The absence of explicit “hybrid threat readiness” dimensions—covering coordinated IT/OT attacks, misinformation, and cross-sector disruption—constitutes a structural blind spot in current maturity models.

6.3.2. OT-Specific Depth and Systemic Risk Representation

Second, there is a persistent misalignment between governance-level frameworks and OT-specific technical realities. High-level instruments such as NIS2 and NIST CSF provide outcome-oriented functions (Identify–Protect–Detect–Respond–Recover), while IEC 62443 and NIST SP 800-82 offer detailed technical controls for ICS and SCADA environments. However, this layered ecosystem is rarely integrated into a coherent assessment methodology. The result is that organizations may achieve formal compliance with governance frameworks while still underestimating systemic OT risks such as the following:

- the possibility of cascading failures in transmission and distribution networks;

- the combined effect of cyber events and physical grid contingencies;

- dependencies on legacy protection relays, field devices, and vendor-specific protocols.

Current frameworks also fall short in quantifying systemic risk at grid level. They focus on organizational controls rather than on how cyber incidents propagate through interconnected substations, control centers and regional operators. Thus, even under full implementation of IEC 62443 controls at asset level, the broader risk of regional blackouts or cross-border disturbances remains only partially represented.

6.3.3. Resilience and Recovery Maturity Beyond “Having a Plan”

Third, while all major frameworks emphasize resilience and recovery, their maturity criteria are often limited to the existence of plans, procedures and drills rather than their effectiveness under stress. The reviewed incidents indicate that:

- manual fallback procedures were either poorly rehearsed or not synchronized across organizations,

- black-start and islanding strategies were not systematically integrated into cyber incident playbooks,

- cross-border and cross-operator coordination mechanisms were reactive rather than pre-negotiated.

In most maturity models, an organization is considered more “mature” if it maintains documented incident response and recovery plans, yet the time-to-recovery, graceful degradation capability and ability to maintain critical functions under partial compromise are rarely measured. This creates a gap between paper-based resilience and operational resilience-a gap that was clearly exposed in several large-scale outages.

6.3.4. Human and Organizational Dimensions as Under-Specified Control Areas

Fourth, the human and organizational dimensions of power system cybersecurity remain under-specified in both maturity models and technical standards. Many of the case studies involved:

- spear-phishing and social engineering against engineers and operators,

- misuse or compromise of legitimate remote access channels,

- decision-making under uncertainty and time pressure in control rooms.

Although frameworks typically include generic references to “training” and “awareness,” they rarely differentiate between routine compliance training and mission-critical operator resilience, such as practicing operations with degraded visibility, conflicting sensor data, or simultaneous cyber–physical contingencies. Moreover, the psychological impact component-how adversaries leverage media, public communication, and uncertainty to amplify the effect of technical disruptions-is almost entirely absent from existing models. This omission is particularly significant for electric power systems, where public confidence and political stability are tightly coupled to perceived reliability.

6.3.5. Future Directions: Toward Hybrid, Resilience-Centric Maturity Models

Taken together, these gaps suggest several directions for the evolution of cybersecurity maturity models and standards for electric power grids:

- 1.

- Explicit Hybrid Threat Readiness Domains: Future versions of frameworks such as NIST CSF and C2M2 should include dedicated domains or subcategories for hybrid, multi-vector attacks, incorporating metrics for supply chain assurance, coordinated IT/OT defense, and the management of informational and psychological effects during prolonged crises.

- 2.

- Integration of Systemic Risk and Grid-Level Resilience Metrics: Maturity models should move beyond organization-centric scoring to include system-level indicators, such as the ability to maintain N-1 security under cyber-induced contingencies, the resilience of protection schemes to malicious manipulation, and the robustness of cross-border coordination mechanisms in interconnected grids.

- 3.

- Stronger Coupling Between Governance Frameworks and Technical Standards: Rather than treating NIS2, NIST CSF, and C2M2 as separate from IEC 62443 and NIST SP 800-82, future approaches should provide explicit mappings from maturity levels to concrete OT controls. This would allow operators to trace how improvements in governance (e.g., risk management processes, executive accountability) translate into measurable hardening of substations, control centers, and field devices.

- 4.

- Resilience-as-a-Function, Not a By-Product: Resilience should be operationalized through quantitative and scenario-based metrics, including time-to-recovery, acceptable degradation modes and performance under concurrent cyber–physical disturbances. Regular, adversary-informed exercises—simulating realistic hybrid attacks on power systems—should be incorporated into maturity assessments.

- 5.

- Human-Centric and Cognitive Resilience Components: Finally, models should incorporate human and organizational resilience as first-class elements, evaluating an organization’s capacity to operate safely under uncertainty, misinformation and partial loss of visibility. This includes advanced training for control room personnel, structured decision-support systems, and communication strategies that mitigate psychological impact on both operators and the public.

By explicitly addressing these gaps, the next generation of maturity models and standards can evolve from static compliance instruments into dynamic, intelligence-driven tools that better reflect the realities of modern cyber operations against electric power systems. In this sense, the lessons derived from past attacks should not only validate existing frameworks but also motivate a systematic redesign of how resilience, hybridity, and human factors are embedded in the cybersecurity governance of critical infrastructures.

7. Conclusions and Implications for Practice

This study has demonstrated that the cybersecurity posture of electric power infrastructures cannot be secured solely through compliance-oriented maturity models or static technical standards. Through a structured methodology that combined incident decomposition, framework-to-control mapping, and a multi-layered gap analysis, the research provided evidence that, while frameworks such as NIST CSF, C2M2, and NIS2 offer essential governance structures—and technical standards such as IEC 62443 and NIST SP 800-82 provide robust control baselines—they nonetheless fall short of fully addressing the hybrid, adaptive, and cross-domain nature of contemporary cyber threats.

From a theoretical standpoint, the findings highlight the need to move beyond mere framework alignment toward a more integrated approach in which governance, technical, operational, and human-centric layers operate as a unified resilience ecosystem. The retrospective mapping conducted in this study shows that several historical incidents could have been mitigated through systematic adoption of existing frameworks, yet the residual gaps point to a deeper structural challenge: current models are not designed to capture adversarial adaptation, systemic grid interdependencies, or the cognitive and organizational dimensions of operator response.

For practitioners, the implications are clear. Formal adherence to frameworks must be complemented by continuous testing, red-team and adversarial simulations, and dynamic risk modeling that reflects real-world operational constraints. For policymakers and standards bodies, the results emphasize the urgency of embedding systemic risk quantification, hybrid-threat readiness, and human resilience metrics as measurable components of next-generation maturity models.

Ultimately, securing the digitalized power grid requires transitioning from a paradigm centered on protection and recovery to one grounded in anticipation, adaptation, and continuous learning. Strengthening cross-sector coordination, establishing intelligence-driven defense cycles, and integrating predictive resilience metrics are indispensable steps toward safeguarding critical electric power infrastructures against the complexity and persistence of modern cyber warfare.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and M.D.; Writing—original draft, A.A.; Writing—review & editing, A.A. and M.D.; Supervision, A.C. and M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in article.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the doctoral research support provided by Gazi University, where this study contributes to the broader objectives of the ongoing Ph.D. dissertation on cybersecurity resilience in electric power systems. The author also appreciates the constructive discussions and insights shared by academic colleagues during the preparation of this paper, which helped refine its conceptual and methodological scope.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Yadav, G.; Paul, K. Architecture and Security of SCADA Systems: A Review. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2021, 34, 100433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamare, D.; Zolanvari, M.; Erbad, A.; Jain, R.; Khan, K.; Meskin, N. Cybersecurity for Industrial Control Systems: A Survey. Comput. Secur. 2020, 89, 101677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). Critical Infrastructure Sectors. U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Available online: https://www.cisa.gov/topics/critical-infrastructure-security-and-resilience/critical-infrastructure-sectors (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Mottahedi, A.; Sereshki, F.; Ataei, M.; Nouri Qarahasanlou, A.; Barabadi, A. The Resilience of Critical Infrastructure Systems: A Systematic Literature Review. Energies 2021, 14, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabacak, B.; Tatar, U. Strategies to Counter Cyber Attacks: Cyber Threats and Critical Infrastructure Protection. Critical Infrastructure Protection Series. 2014. Available online: https://fuse.franklin.edu/facstaff-pub/44 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- He, H.; Chan, K.W.; Gu, J. Cyber-Physical Attacks and Defences in the Smart Grid: A Survey. IET Cyber-Phys. Syst. Theory Appl. 2016, 1, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, W.; Prince, D.; Hutchison, D.; Disso, J.F.P.; Jones, K. A Survey of Cyber Security Management in Industrial Control Systems. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2015, 9, 52–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alladi, T.; Chamola, V.; Zeadally, S. Industrial Control Systems: Cyberattack Trends and Countermeasures. Comput. Commun. 2020, 155, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.M.; Abu-Nimeh, S. Lessons from Stuxnet. Computer 2011, 44, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, T.; Geiger, M.; Bauer, J.; Masuch, M.; Franke, J. An Analysis of Black Energy 3, CrashOverride, and TRISIS: Three Malware Approaches Targeting Operational Technology Systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Vienna, Austria, 8–11 September 2020; pp. 1537–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, M.M.; Shajari, M.; Shafiee, M.A. Industrial Control System Security Taxonomic Framework with Application to a Comprehensive Incidents Survey. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2020, 29, 100356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mrabet, Z.; Kaabouch, N.; El Ghazi, H.; El Ghazi, H. Cyber-Security in Smart Grid: Survey and Challenges. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2018, 67, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.R.; Hu, Q.; Zeadally, S. Cybersecurity in Industrial Control Systems: Issues, Technologies, and Challenges. Comput. Netw. 2019, 165, 106946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmavathy, R.; Singh, S.K.; Sindhu, M.; Jasim, L.H.; Saxena, A.; Dari, S.S. Enhancing Power Grid Resilience Against Cyber Threats in the Smart Grid Era. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 540, 01021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, N.; Gkioulos, V. Cyber security training for critical infrastructure protection: A literature review. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2021, 40, 100361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0. NIST Cybersecurity White Paper, 2024, NIST CSWP 29. Available online: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.CSWP.29 (accessed on 12 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model (C2M2), Version 2.0. Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response (CESER). 2021. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/ceser/cybersecurity-capability-maturity-model-c2m2 (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). IEC 62443 Series: Security for Industrial Automation and Control Systems; International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://webstore.iec.ch/publication/22273 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). NIST Special Publication 800-82, Revision 3: Guide to Industrial Control Systems (ICS) Security; U.S. Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-82r3.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- IEC 60870-5-101; Telecontrol Equipment and Systems—Part 5-101: Transmission Protocols—Companion Standard for Basic Telecontrol Tasks. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- IEC 60870-5-104; Telecontrol Equipment and Systems—Part 5-104: Transmission Protocols—Network Access for IEC 60870-5-101 Using Standard Transport Profiles. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- IEC 61850; Communication Networks and Systems for Power Utility Automation. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2022/2557 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Resilience of Critical Entities. Off. J. Eur. Union 2022, L333, 164–204. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/2557/oj (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Explore Electricity Security 2021. IEA Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-security (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Lee, R.M.; Assante, M.J.; Conway, T. Analysis of the Cyber Attack on the Ukrainian Power Grid. SANS Industrial Control Systems Report. 2016. Available online: https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/3891751/SANS-and-Electricity-Information-Sharing-and.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Miller, T.; Staves, A.; Maesschalck, S.; Sturdee, M.; Green, B. Looking Back to Look Forward: Lessons Learnt from Cyber-Attacks on Industrial Control Systems. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2024, 45, 100627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragos Inc. CRASHOVERRIDE: Analysis of the Threat to Electric Grid Operations. Dragos Intelligence Report. 2017. Available online: https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/3869008/Dragos-CRASHOVERRIDE-Analyzing-the-Threat-to.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Cherepanov, A.; Lipovský, R. Industroyer: Biggest Threat to Industrial Control Systems Since Stuxnet. ESET Research White Paper. 2017. Available online: https://www.welivesecurity.com/2017/06/12/industroyer-biggest-threat-industrial-control-systems-since-stuxnet/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Langer, R. Robust Control System Networks: How to Achieve Reliable Control After Stuxnet; Momentum Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Umer, M.A.; Junejo, K.N.; Jilani, M.T.; Mathur, A.P. Machine Learning for Intrusion Detection in Industrial Control Systems: Applications, Challenges, and Recommendations. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2021, 38, 100516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozjaei, M.D.; Mahmoudyar, N.; Baseri, Y.; Ghorbani, A.A. An Evaluation Framework for Industrial Control System Cyber Incidents. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2023, 36, 100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyber Threat Alliance. Incident Response Blog: Cyber Incidents in Ukraine. Cyber Threat Alliance Blog, 25 February 2022. Available online: https://www.cyberthreatalliance.org/incident-response-blog-cyber-incidents-in-ukraine/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Dehlawi, Z.; Abokhodair, N. Saudi Arabia’s Response to Cyber Conflict: A Case Study of the Shamoon Malware Incident. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics, Seattle, WA, USA, 4–7 June 2013; pp. 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symantec Security Response. Shamoon: Destructive Threat Re-Emerges with New Sting in Its Tail. Symantec Technical Report. 2012. Available online: https://www.security.com/threat-intelligence/shamoon-destructive-threat-re-emerges-new-sting-its-tail (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Bronk, C.; Tikk-Ringas, E. The Cyber Attack on Saudi Aramco. Survival 2013, 55, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumbergs, B. Technical Analysis of Advanced Threat Tactics Targeting Critical Information Infrastructure. Cyber Security Review, 2014, Winter Issue. pp. 1–12, NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCD COE). Available online: https://ccdcoe.org/uploads/2018/10/2014-Technical-Analysis-of-Advanced-Threat-Tactics-Targeting-Critical-Information-Infrastructure.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Kumar, R.; Kela, R.; Singh, S.; Trujillo-Rasua, R. APT Attacks on Industrial Control Systems: A Tale of Three Incidents. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2022, 37, 100521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SOC Prime. Detect Industroyer2 and CaddyWiper Malware: Sandworm APT Hits Ukrainian Power Facilities. CERT-UA Security Advisory. 2022. Available online: https://socprime.com/blog/detect-industroyer2-and-caddywiper-malware-sandworm-apt-hits-ukrainian-power-facilities/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- ESET Research. Industroyer2: Industroyer Reloaded-This ICS-Capable Malware Targets a Ukrainian Energy Company. ESET Threat Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.welivesecurity.com/2022/04/12/industroyer2-industroyer-reloaded/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Security.com Threat Intelligence Team. Shamoon Is Back: Analysis of the Latest Destructive Campaign. Security.com Threat Intelligence Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.security.com/threat-intelligence/shamoon-back-destructive (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Langner, R. Stuxnet: Dissecting a Cyberwarfare Weapon. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2011, 9, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushner, D. The Real Story of Stuxnet. IEEE Spectr. 2013, 50, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetter, K. Inside the Cunning, Unprecedented Hack of Ukraine’s Power Grid. Wired Magazine. 2016. Available online: https://www.wired.com/2016/03/inside-cunning-unprecedented-hack-ukraines-power-grid/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Aytekin, A.; Dursun, M. Enhancing Cyber Defense and Resilience of Critical Infrastructures Against Terrorist Attacks. Def. Terror. Rev. 2023, 18, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0. U.S. Department of Commerce. 2024. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/cyberframework (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- European Union (EU). Directive (EU) 2022/2555 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on Measures for a High Common Level of Cybersecurity Across the Union (NIS2 Directive). Off. J. Eur. Union 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32022L2555 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). 21 Steps to Improve Cyber Security of SCADA Networks; Office of Energy Assurance, U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/oeprod/DocumentsandMedia/21_Steps_-_SCADA.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.