Abstract

Lycopene is a potent antioxidant carotenoid with significant health-promoting properties. However, its practical application is limited by poor water solubility. This study aimed to enhance lycopene dispersibility through the development of solid dispersions obtained by hot-melt extrusion (HME). Polymeric carriers composed of polyvinylpyrrolidone K30 (PVP K30), phosphatidylcholine, and xylitol were designed to achieve optimal processing conditions and thermal stability. Nine formulations containing 10–30% lycopene were prepared and characterized using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), and dispersibility testing. TGA confirmed the thermal stability of lycopene at the extrusion temperature (150 °C). DSC and XRPD analyses indicated partial amorphization of lycopene in the extrudates, while FT-IR spectra revealed molecular interactions between lycopene and carrier components, particularly hydroxyl and carbonyl groups. Among the tested systems, the formulation containing PVP K30 and xylitol without phosphatidylcholine exhibited the highest dispersibility (1.0484 mg/mL after 3 h). Dispersibility decreased with increasing lycopene content. These findings demonstrate that HME is an effective technique for producing partially amorphous lycopene dispersions with improved dispersibility, and that polymer–polyol systems are particularly promising carriers for enhancing lycopene bioavailability.

1. Introduction

Lycopene is a naturally occurring carotenoid responsible for the characteristic red hue of fruits and vegetables [1,2]. Tomato-based products are the predominant contributors to dietary intake of this compound [3]. Owing to its structure rich in conjugated double bonds, lycopene displays remarkable antioxidant activity; however, it has extremely poor water solubility and chemical instability [4,5,6,7]. Environmental factors such as light, heat, oxygen, acidic pH, and the presence of metal ions can readily promote its degradation, ultimately limiting its biological efficacy and practical utility across pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic applications [2,8,9,10]. Despite extensive evidence supporting its beneficial effects in conditions related to oxidative stress, including cardiovascular disorders, cancer, and metabolic diseases, the low bioavailability of lycopene remains a major barrier to fully harnessing its therapeutic potential [3,4,11,12].

To overcome these limitations, innovative formulation strategies are required to enhance its stability and improve its solubility profile. Among the emerging techniques, hot-melt extrusion (HME) has gained considerable attention as a solvent-free, continuous process capable of modifying the physicochemical properties of poorly soluble bioactives. It is regarded as one of the leading strategies for improving the solubility of active pharmaceutical compounds with poor aqueous solubility, mainly because it can convert crystalline substances into an amorphous state. Transitioning a substance from a crystalline to an amorphous form significantly increases its solubility and dissolution rate by disrupting its ordered structure, which enhances molecular mobility and surface area [13,14,15]. This behavior is largely due to the greater free energy of the amorphous phase compared with the crystalline lattice, enabling more rapid dissolution [16].

Among the available methods for generating amorphous systems, HME is particularly notable because of multiple benefits. It is a solvent-free, continuous technique that is cost-efficient and readily adaptable for large-scale manufacturing [17,18]. Industrially, HME uses rotating screws that transport and blend polymeric materials at temperatures above their glass transition temperature, enabling the active components to be dispersed at the molecular level within thermoplastic carriers such as polymers or binders. The resulting material is a uniform amorphous product with improved physical consistency and enhanced dissolution behavior [19,20].

In recent years, hot-melt extrusion has attracted growing interest in both pharmaceutical and nutraceutical fields because of its ability to enhance the solubility, stability, and bioavailability of poorly soluble actives such as carotenoids. A key factor determining the effectiveness of HME-based systems is the selection of suitable carrier polymers [21,22].

Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) is a synthetic, biocompatible, and chemically stable polymer widely used in pharmaceutical formulations [23,24,25]. It is available in multiple grades defined by K-values, which reflect polymer chain length and solution viscosity [24,26]. Among these, PVP K30 (≈50 kDa) is one of the most commonly applied due to its stability and versatility [23,24,26].

PVP, especially PVP K30, enhances aqueous solubility, dissolution rate, and oral bioavailability of poorly soluble compounds by forming stabilizing interactions that help maintain amorphous drug forms [27,28,29]. For these reasons, PVP K30 has been reported as an effective carrier for lycopene, supporting its improved solubility and bioavailability [30,31]. Previous studies employing solvent evaporation, mechanical mixing, or solid dispersion methods demonstrated that PVP K30 can significantly improve lycopene solubility and dispersion stability, whether used alone or in combination with polymers such as Eudragit L100, Poloxamer, or other hydrophilic excipients [31,32,33]. These findings support the rationale behind selecting PVP K30 in the present study and underscore its versatility as a polymeric matrix for carotenoid delivery systems.

In addition to polymeric carriers such as PVP K30, phospholipids are often incorporated to further enhance the performance of formulations. Their amphiphilic nature enables the formation of supramolecular structures, including micelles, which reduce interfacial tension and facilitate the solubilization of poorly water-soluble active compounds. As a result, phospholipids improve dissolution and bioavailability and are therefore widely used as versatile pharmaceutical excipients [34]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that phospholipid complexes enhance solubility and systemic exposure of bioactive molecules, as shown for mangiferin [35] and curcumin [36]. Despite these advantages, phospholipid-based delivery systems also present technological challenges. Their soft, lipid-like consistency can hinder the preparation of solid dosage forms, and phospholipid complexes often exhibit a tendency to aggregate or agglomerate, which may negatively affect dissolution and absorption [37,38,39]. To overcome these limitations, the combination of phospholipids with amorphous polymers has been highlighted as a promising strategy. Polymer–phospholipid matrices, such as those prepared using PVP K30, have been shown to improve the dispersibility, amorphization, and bioavailability of poorly soluble compounds more effectively than phospholipid complexes alone [37].

Alongside polymers and phospholipids, sweetening agents like xylitol can also play a functional role in hot-melt extrusion formulations. Acting as plasticizers, sugar alcohols such as xylitol contain multiple hydroxyl groups that form hydrogen bonds, helping to stabilize dispersions of active compounds. Previous research has demonstrated their effectiveness in producing solid dispersions of bioactive compounds, such as curcumin and hesperetin, via hot-melt extrusion [40]. Xylitol also acts as an effective plasticizer, as previously reported for HME-processed bioactive compounds, including curcumin and hesperetin [40,41].

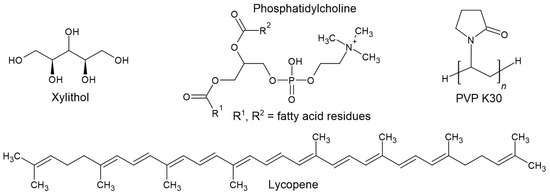

Figure 1 shows the chemical structures of xylitol, phosphatidylcholine, PVP K30, and lycopene.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of xylitol, phosphatidylcholine, PVP K30, and lycopene.

Therefore, the aim of this study was not only to apply hot-melt extrusion to obtain solid dispersions of lycopene, but also to systematically design and evaluate carrier systems composed of PVP K30, phosphatidylcholine, and/or xylitol to enhance the aqueous dispersibility of this carotenoid. Specifically, this study sought to: (i) formulate carrier mixtures with thermal and rheological properties suitable for efficient extrusion; (ii) process lycopene with these carriers using HME at varying excipient ratios; (iii) assess the thermal behavior and glass transition characteristics of the prepared systems; (iv) determine the extent of amorphization achieved during extrusion; (v) identify potential molecular interactions between lycopene and the individual carrier components; and (vi) evaluate the dissolution performance of the resulting solid dispersions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Lycopene (CAS No. 502-65-8, purity 98%) was purchased from Angene (Secunderabad, India). Polyvinylpyrrolidone K30 (PVP K30; CAS No. 9003-39-8) and phosphatidylcholine from dried egg yolk (CAS No. 8002-43-5, product No. 61755) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Xylitol was provided by Santini (Poznań, Poland). Methanol (HPLC grade) was purchased from J.T. Baker (Center Valley, PA, USA), and phosphate buffer concentrate was obtained from Stamar (Dąbrowa Górnicza, Poland). Ultrapure water was produced using a Direct-Q 3 UV water purification system (Millipore, Molsheim, France; model Exil SA 67120).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of Carriers

To prepare the carriers (mixtures of PVP K30 polymer with phospholipid and/or xylitol), the weighed components were transferred into a beaker and dissolved in 100 mL of purified water at 22 °C. The mixtures were then mixed using a magnetic stirrer. Various formulations were prepared by adjusting the percentage ratio of the excipients to achieve a glass transition temperature of 115 °C for the PVP K30–phospholipid–xylitol mixture. The required quantities of each component were calculated using equations derived from a linear function.

The percentage composition of each formulation is presented in Table 1. The resulting mixture was subjected to lyophilization using a LyoQuest-85 freeze dryer (Telstar, Terrassa, Spain) at −82.1 °C under a pressure of 0.412 mbar. The purpose of lyophilization was to eliminate residual moisture from the carrier and ensure accurate weighing of the excipients, thereby minimizing potential variability in thermal behavior and extrusion parameters. After completion of the process, the lyophilizate was powdered using a laboratory mill.

Table 1.

Percentage composition of polymer, phospholipid, and xylitol in the carrier formulations.

2.2.2. Preparation of Extrudates

Nine extrudates containing 10%, 20%, and 30% lycopene were prepared. For each formulation, the appropriate amounts of lycopene and carrier were accurately weighed on weighing paper as follows:

- (a)

- F1: 0.3 g lycopene, 2.7 g carrier 1;

- (b)

- F2: 0.3 g lycopene, 2.7 g carrier 2;

- (c)

- F3: 0.3 g lycopene, 2.7 g carrier 3;

- (d)

- F4: 0.6 g lycopene, 2.4 g carrier 1;

- (e)

- F5: 0.6 g lycopene, 2.4 g carrier 2;

- (f)

- F6: 0.6 g lycopene, 2.4 g carrier 3;

- (g)

- F7: 0.9 g lycopene, 2.1 g carrier 1;

- (h)

- F8: 0.9 g lycopene, 2.1 g carrier 2;

- (i)

- F9: 0.9 g lycopene, 2.1 g carrier 3.

Each mixture prepared for extrusion had a total mass of 3 g (Table 2). The components were thoroughly blended using a laboratory mill. The mixtures were then sequentially fed into the extruder hopper. The extrusion process was carried out at 150 °C and a screw speed of 90 rpm. The obtained extrudates were ground using a laboratory mill, transferred into Eppendorf tubes, and stored for further analyses.

Table 2.

Percentage composition of lycopene and phospholipid in the carrier formulations.

2.2.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Differential scanning calorimetry analyses were performed using a DSC 214 Polyma instrument (Netzsch, Selb, Germany). Approximately 5–10 mg of each sample was placed into crimped aluminum pans equipped with lids containing a small pinhole. The samples were first heated to 205 °C, cooled to 25 °C, and subsequently reheated to remove residual moisture. Measurements were conducted under a nitrogen atmosphere at a flow rate of 250 mL/min, using a heating and cooling rate of 10 K/min.

Raw lycopene was heated to 195 °C, cooled to 25 °C, and then reheated to 195 °C at heating rates of 5, 10, 20, and 40 K/min to assess its ability to undergo amorphization.

For the Tg analysis of the PVP K30–phospholipid and PVP K30–phospholipid–xylitol systems, the samples were first heated to 195 °C to remove residual moisture, cooled to 25 °C, and then reheated to 195 °C. All measurements were performed at a heating rate of 10 K/min.

2.2.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Thermogravimetric analysis was performed using a TG 209 F3 Tarsus microbalance (Netzsch, Selb, Germany). Approximately 6 mg of the powdered sample was placed in an alumina crucible and heated from 25 °C to 550 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min. Nitrogen was used as the purge gas at a flow rate of 250 mL/min.

2.2.5. X-Ray Powder Diffraction (XRPD)

X-ray diffraction measurements were carried out using a Bruker AXS D2 Phaser diffractometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with a copper anode (Cu-Kα radiation, λ = 1.54 Å, 30 kV, 10 mA). Data were collected over a 2θ range of 5–45°, with a step size of 0.02° and a counting time of 2 s per step.

2.2.6. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

FT-IR spectra were recorded using a Shimadzu IRT Racer-100 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a single-reflection diamond QATR-10 accessory. The instrument was operated with LabSolutions IR software (version 1.86 SP2, Warsaw, Poland) at a spectral resolution of 1 cm−1.

2.2.7. Dispersibility Study

The aim of this experiment was to evaluate the apparent aqueous dissolution and dispersibility of lycopene released from the solid dispersions, rather than to determine its intrinsic solubility. Because the intrinsic solubility of lycopene in water does not change, the test reflects its ability to disperse in an aqueous medium following encapsulation within the hydrophobic domains of the carrier matrix.

As the dissolution medium, purified water with phosphate buffer components was used. This medium provides a predominantly aqueous environment with controlled and physiologically relevant pH, while the small amount of buffer salts ensures pH stability without interacting with lycopene or the excipients.

For the dispersibility test, an excess amount of each powdered formulation equivalent to 1.5 mg of lycopene was placed in 10 mL glass tubes. Then, 2.0 mL of phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) was added to the water, and the mixtures were stirred at 100 rpm at room temperature (25 ± 0.1 °C). Samples were collected after 3 and 24 h of stirring.

During the dispersibility studies, lycopene concentrations were determined using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The analyses were performed on a Shimadzu LC-2050C system (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a diode array detector (DAD). The stationary phase consisted of a Dr. Maisch ReproSil-Pur Basic-C18 column (100 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; Dr. Maisch, Ammerbuch-Entrigen, Germany). The mobile phase was 100% methanol, delivered at a flow rate of 2 mL/min. Detection was carried out at 470 nm, and the column temperature was maintained at 30 °C. The injection volume was 10 µL. Lycopene exhibited a retention time of 10.62 min.

The linearity of the method was evaluated over the concentration range of 0.00004–0.2 mg/mL. The correlation coefficient (r = 0.99393) indicated a strong linear relationship between concentration and detector response. The slope (a ± Sa) was 30,643,566 ± 3,131,891.4648, and the intercept was found to be statistically insignificant (α = 0.05). The limit of detection (LOD) and the limit of quantification (LOQ) were 0.0286 mg/mL and 0.0867 mg/mL, respectively. These results confirmed that the method met the analytical linearity requirements and was suitable for quantitative determination of lycopene.

3. Results

3.1. Ability of Lycopene to Form an Amorphous Phase

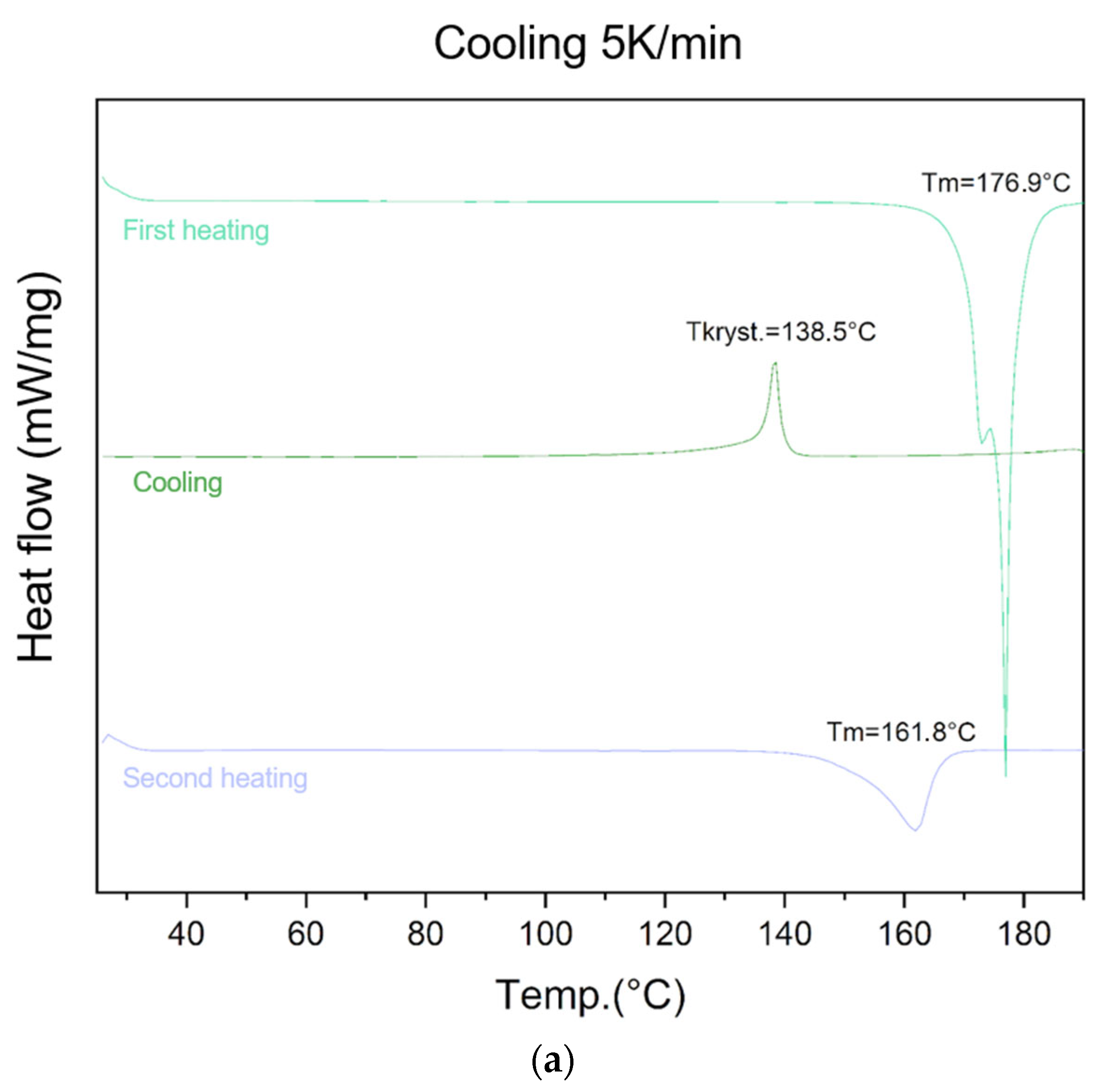

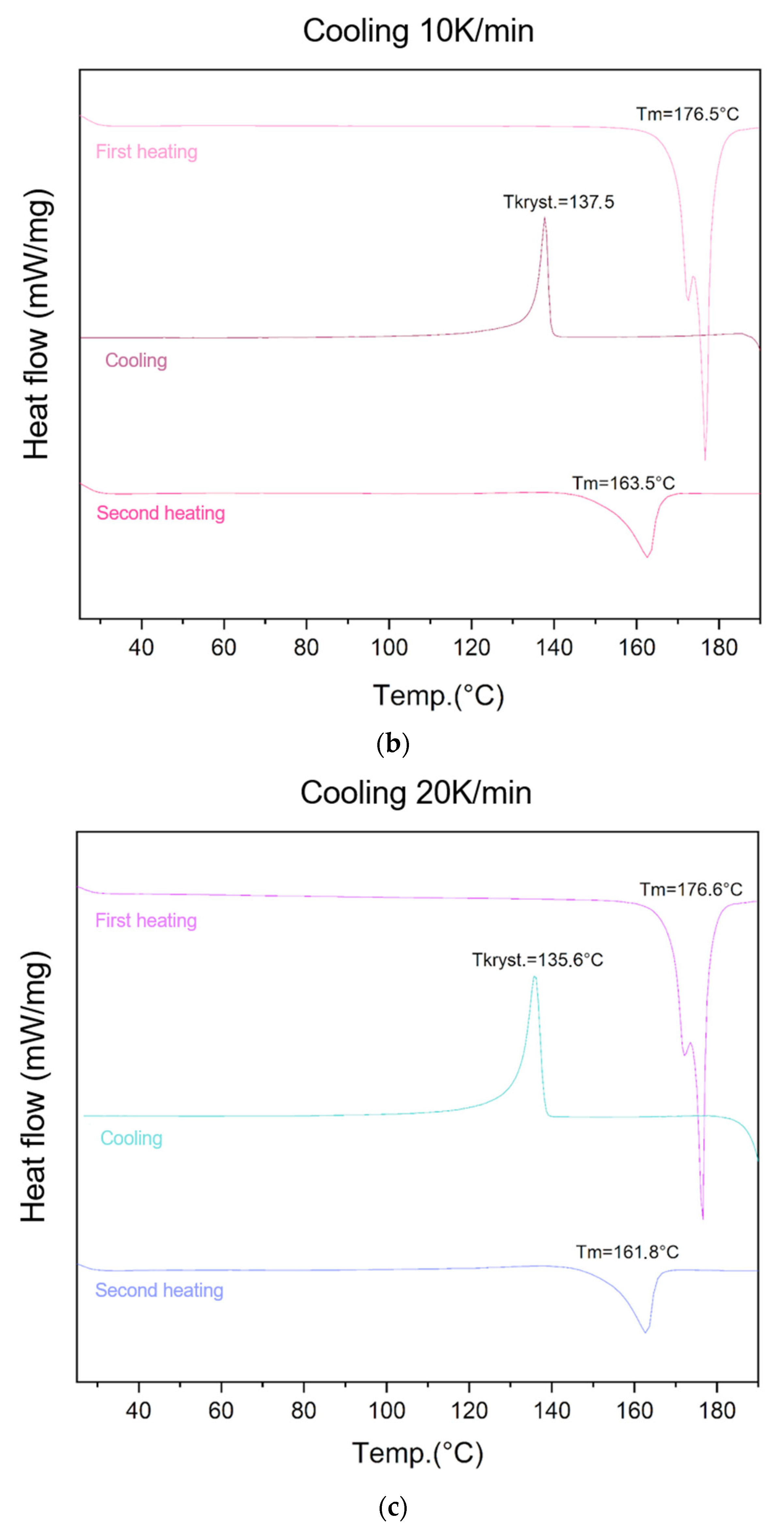

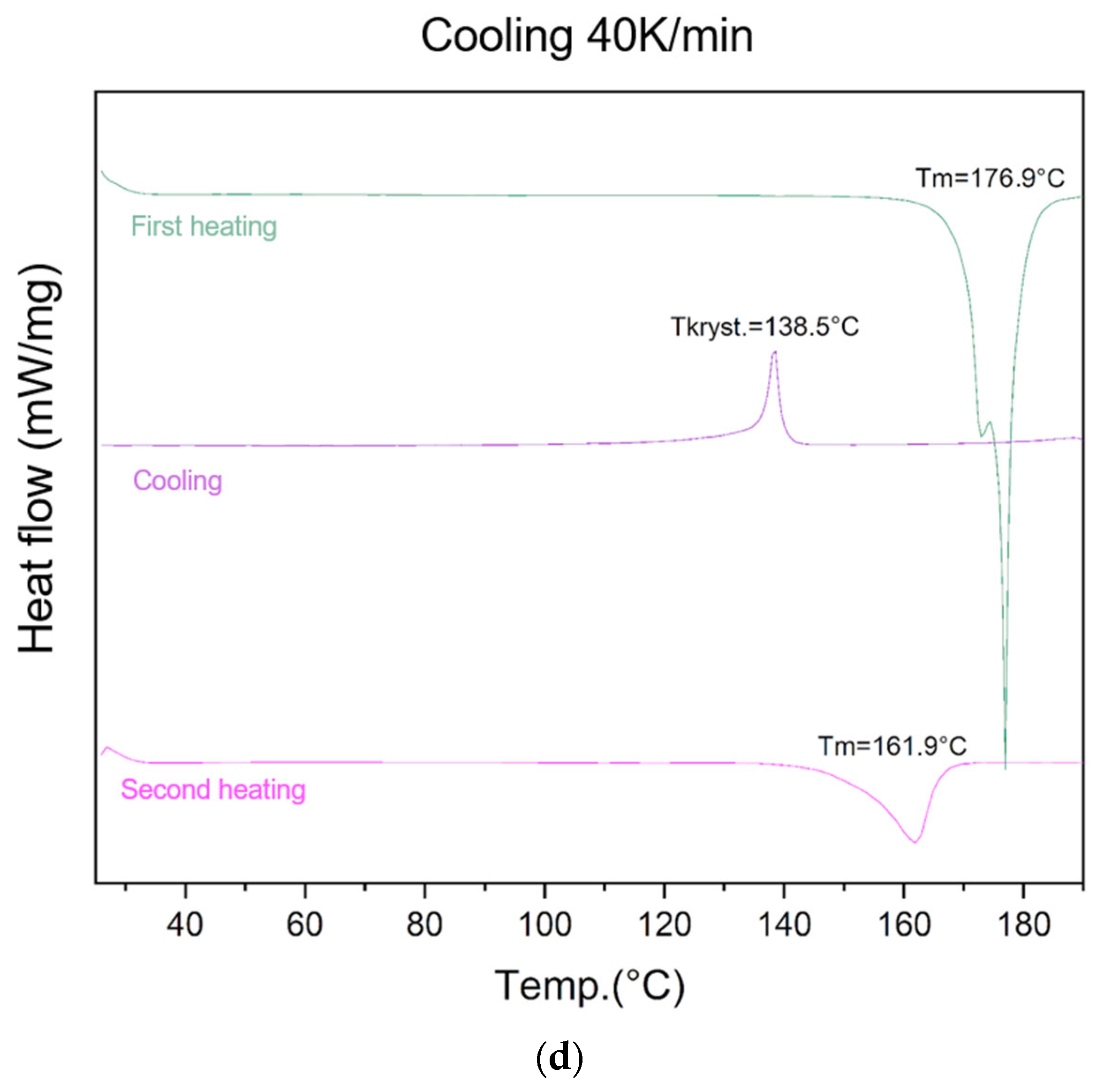

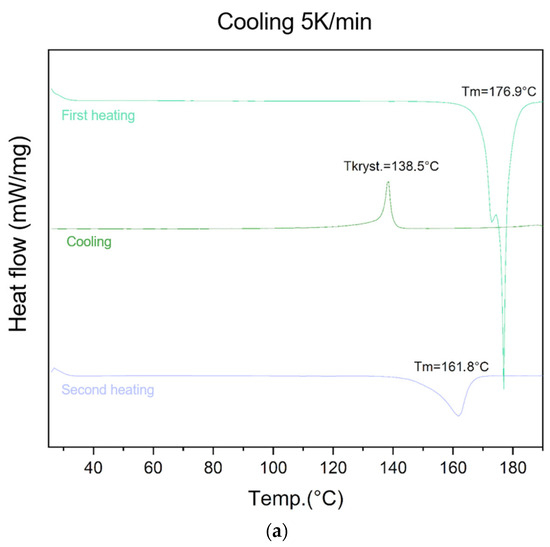

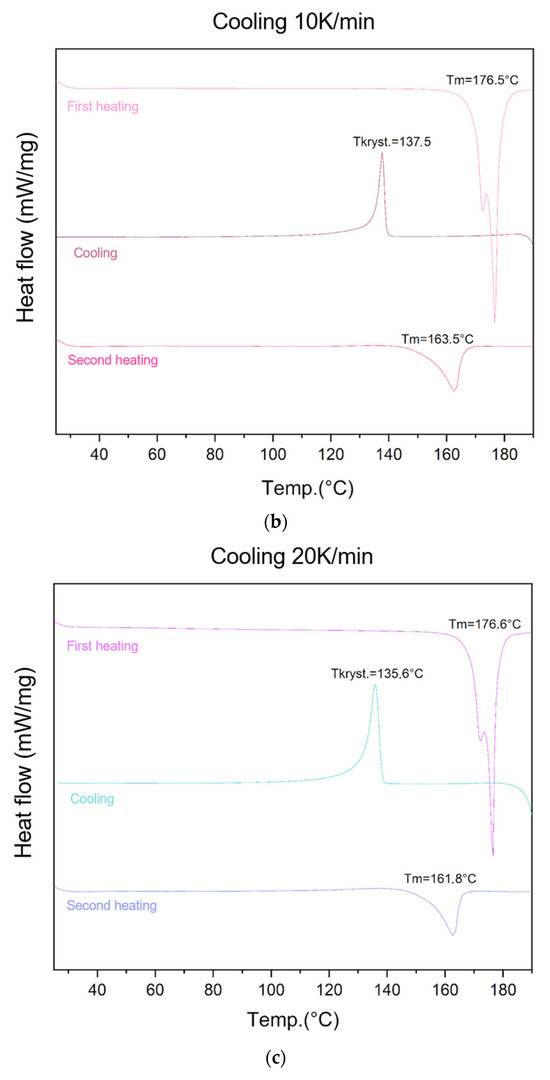

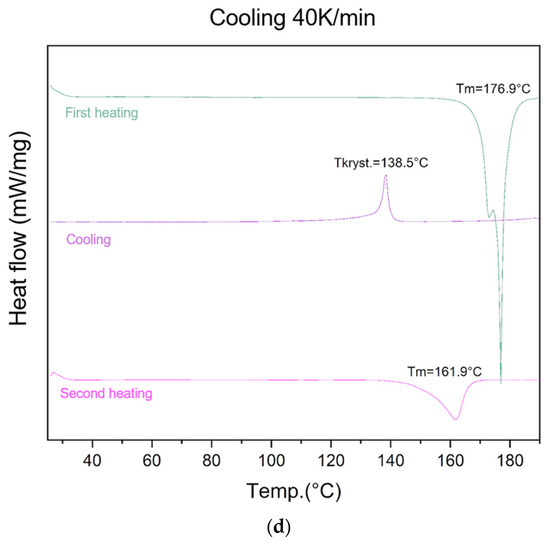

The ability of lycopene to form an amorphous phase was evaluated using different cooling rates (5 K/min, 10 K/min, 20 K/min, and 40 K/min) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Evaluation of lycopene’s ability to form an amorphous phase. First heating, cooling, and second heating were presented. The procedure was performed using a cooling temperature of (a) 5 K/min; (b) 10 K/min; (c) 20 K/min; (d) 40 K/min.

For the lowest cooling rate (5 K/min), an endothermic peak at 176.9 °C was observed during the first heating cycle, corresponding to the melting point of lycopene. An exothermic peak at 138.0 °C appeared during the cooling cycle, indicating a recrystallization process. During the second heating, an endothermic transition at 161.8 °C was recorded, confirming the presence of the crystalline phase in the sample.

At the cooling rate of 10 K/min, an endothermic peak at 176.5 °C was observed during the first heating, followed by an exothermic recrystallization peak at 137.5 °C during cooling, and an endothermic transition at 163.5 °C during the second heating.

Similarly, for the cooling rate of 20 K/min, all three transitions were observed: melting at 176.6 °C (first heating), recrystallization at 135.6 °C (cooling), and endothermic transition at 161.8 °C (second heating).

At the highest cooling rate (40 K/min), an endothermic peak at 176.9 °C was recorded during the first heating, followed by an exothermic recrystallization event at 138.5 °C during cooling. The second heating cycle revealed an endothermic peak at 161.9 °C, confirming the presence of residual crystalline regions.

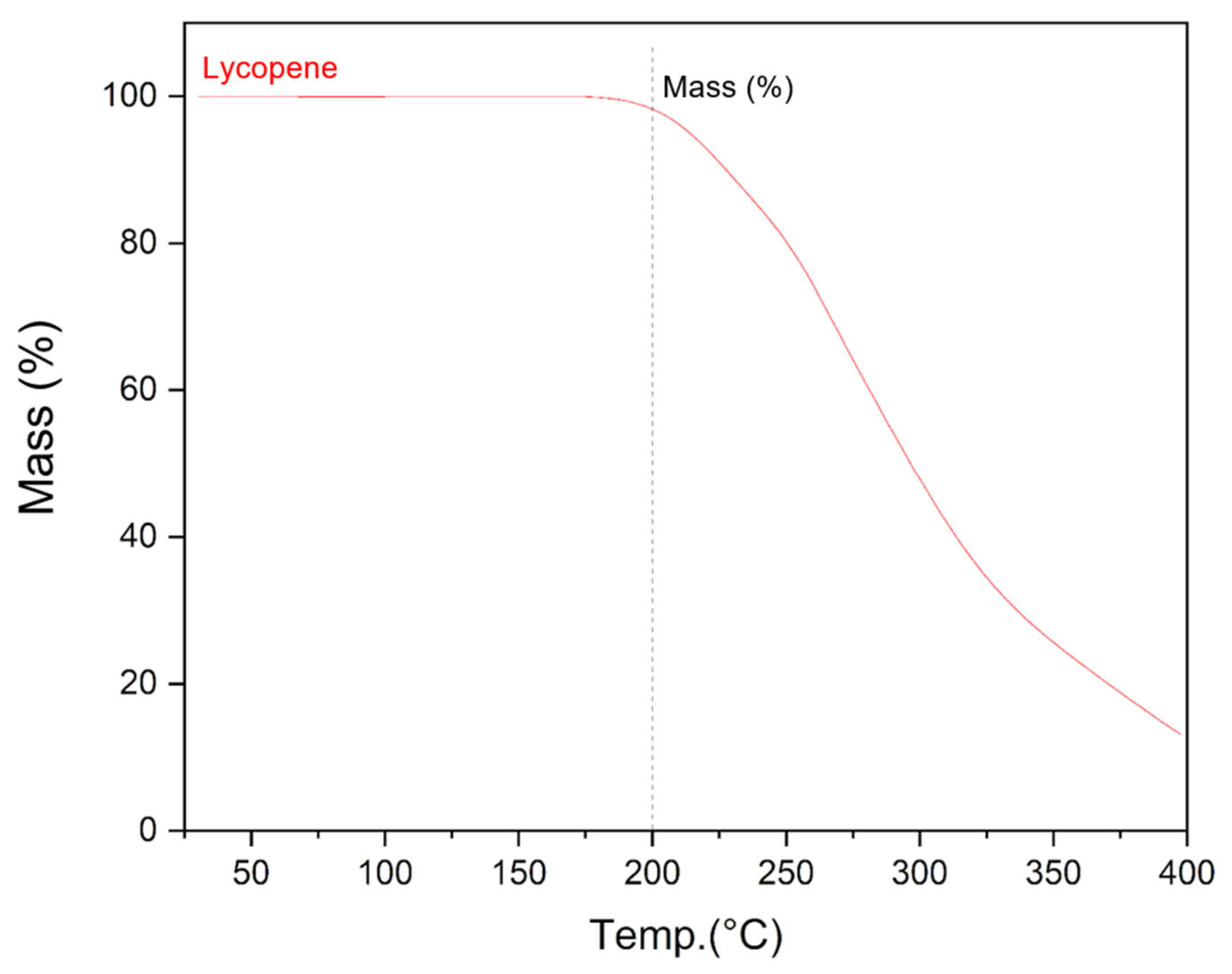

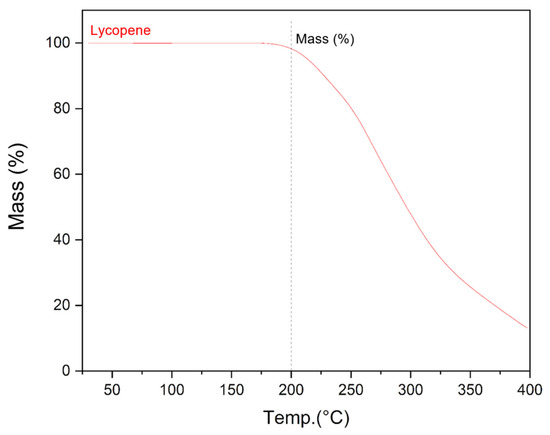

3.2. Determination of Lycopene Thermal Stability

The use of hot-melt extrusion to obtain solid dispersions of lycopene with enhanced dispersibility involves exposure to elevated temperatures during processing. Prior to conducting this study, it was necessary to assess whether lycopene would degrade at the processing temperature of 150 °C. Thermogravimetric analysis showed that lycopene remains stable at 150 °C. A mass loss of approximately 2% was observed only upon heating to 200 °C, indicating sufficient thermal stability under the applied extrusion conditions (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Graph of the dependence of the mass of the lycopene sample on temperature obtained as a result of thermogravimetric analysis.

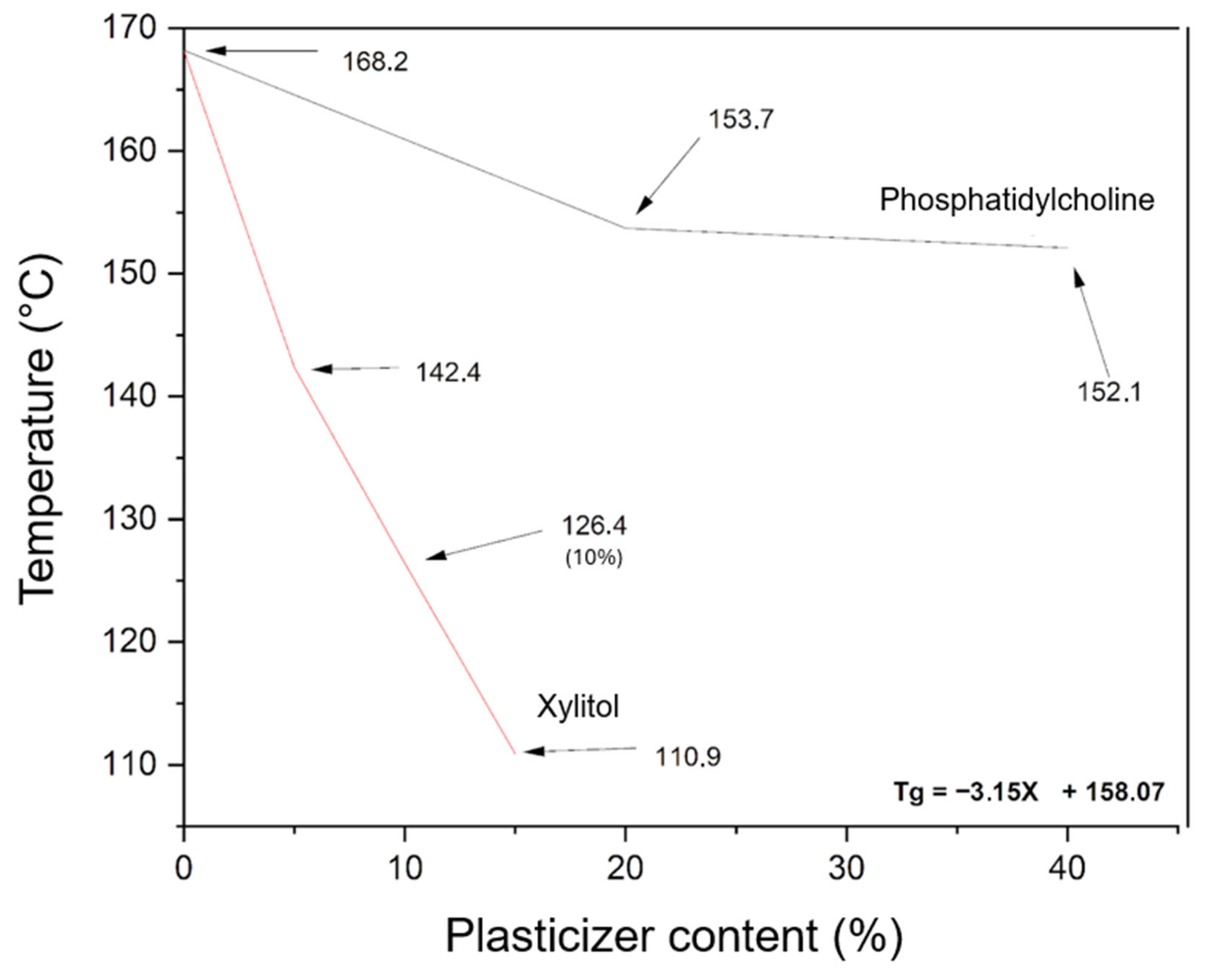

3.3. Design of PVP K30–Phosphatidylcholine–Xylitol Systems

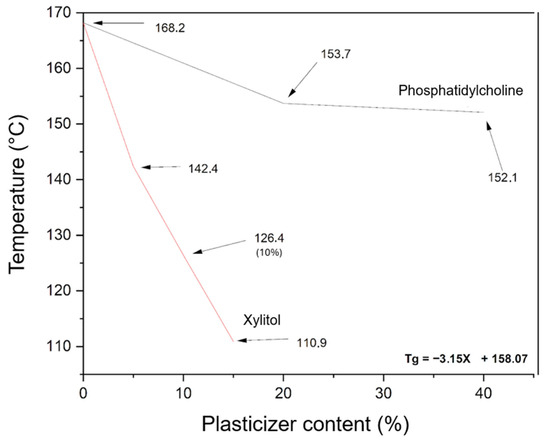

To prepare amorphous lycopene dispersions via hot-melt extrusion, it was necessary to first design PVP K30–phospholipid mixtures with appropriate thermal properties. Figure 4 shows the dependence of xylitol and phosphatidylcholine content on the Tg value of the PVP K30-excipient mixture.

Figure 4.

Effect of excipient content on the glass transition temperature (Tg) of PVP K30-excipient mixtures, as determined by DSC. The black line represents PVP K30 with phosphatidylcholine, and the red line represents PVP K30 with xylitol (X, % w/w). Arrows indicate Tg values. The equation shows the influence of xylitol content on the Tg of the PVP K30-based mixture.

The evaluation of phosphatidylcholine’s effect on the selected polymer indicated only a minor plasticizing effect on PVP K30. Therefore, xylitol was introduced as an additional plasticizer. The relationship between xylitol content (5–15%) and the resulting thermal properties was found to be linear, allowing the derivation of a linear function to calculate the xylitol content required to achieve the desired glass transition temperature (Tg) for the PVP K30–phosphatidylcholine–xylitol mixture.

The carriers were designed to have a Tg of 115 °C, ensuring a minimum difference of 20 °C from the extrusion temperature, which is necessary for efficient processing. Carrier 1 contained 13.67% xylitol, carrier 2 contained 7.64%, and carrier 3 contained 5.54%.

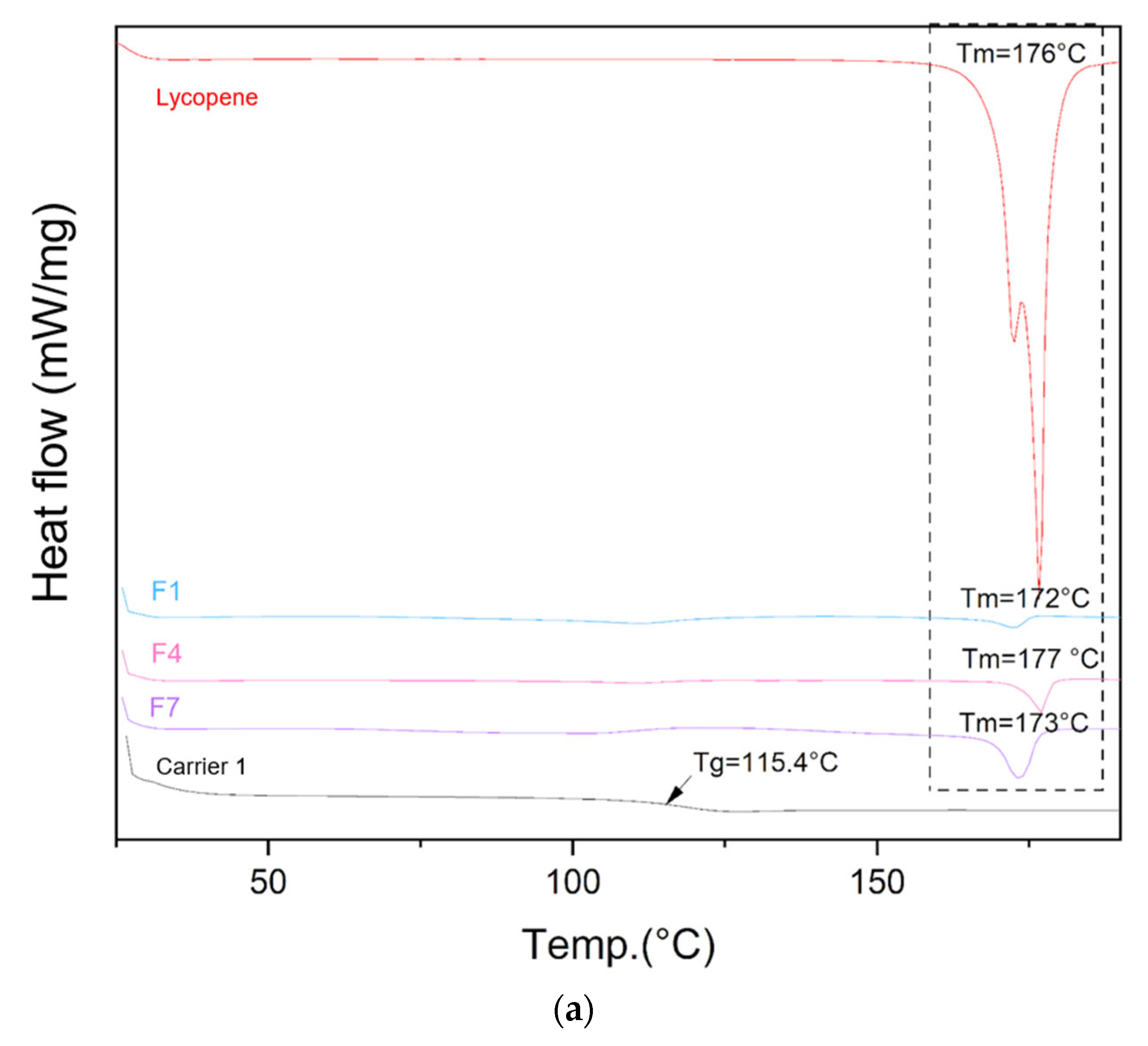

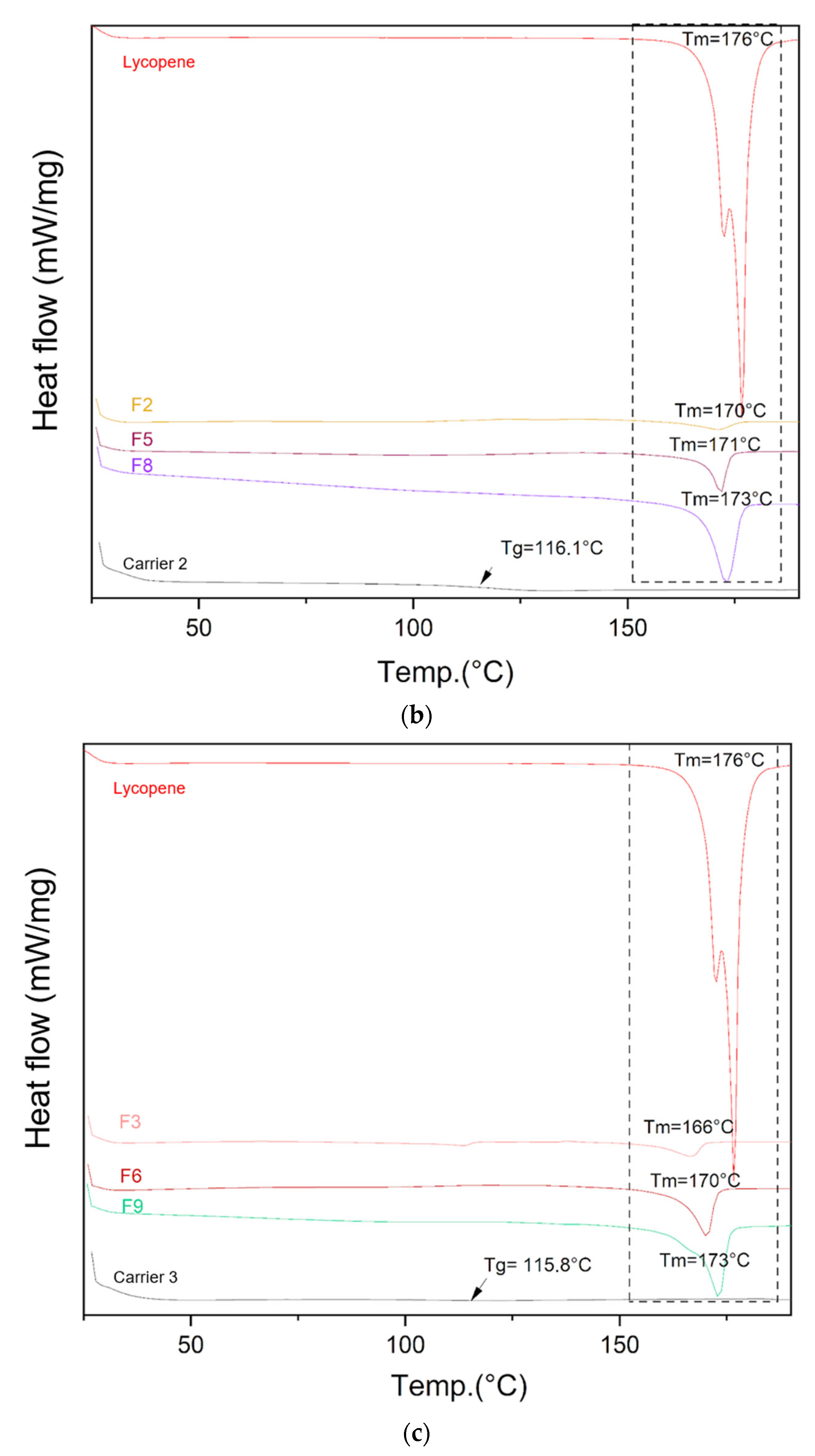

3.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

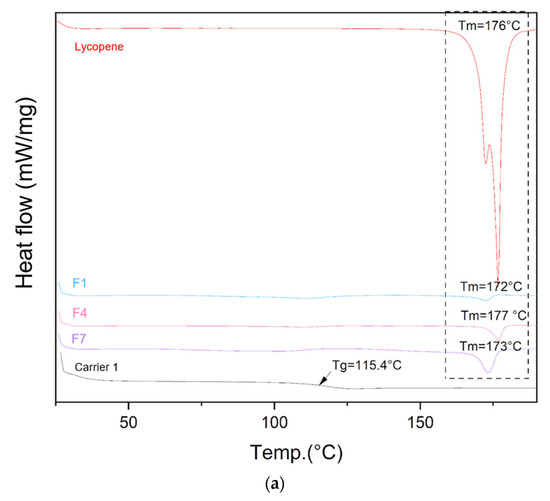

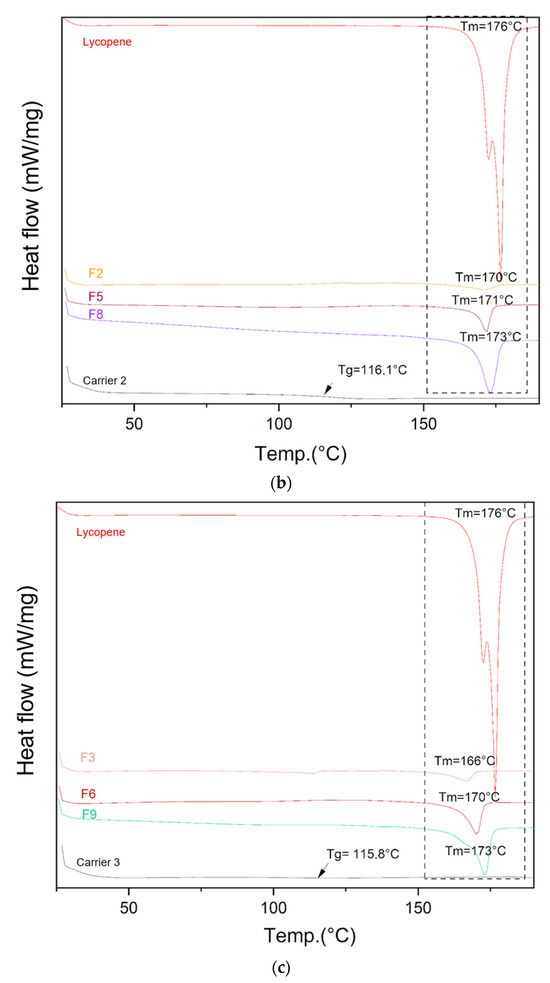

The DSC thermograms of lycopene, carriers and extrudates are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

DSC thermograms of (a) lycopene, carrier 1 and systems containing it: 1, 4 and 7; (b) lycopene, carrier 2 and systems containing it: 2, 5 and 8; (c) lycopene, carrier 3 and systems containing it: 3, 6 and 9. The arrow points to Tg (glass transition temperature).

Differential scanning calorimetry was used to evaluate the thermal properties of the prepared systems. The glass transition temperatures (Tg) of the carriers were similar: 115.4 °C for carrier 1, 116.1 °C for carrier 2, and 115.8 °C for carrier 3, in accordance with the design specifications. Endothermic peaks corresponding to lycopene melting were observed on the thermograms of the prepared formulations, indicating the presence of crystalline regions within the dispersions.

3.5. X-Ray Powder Diffraction (XRPD)

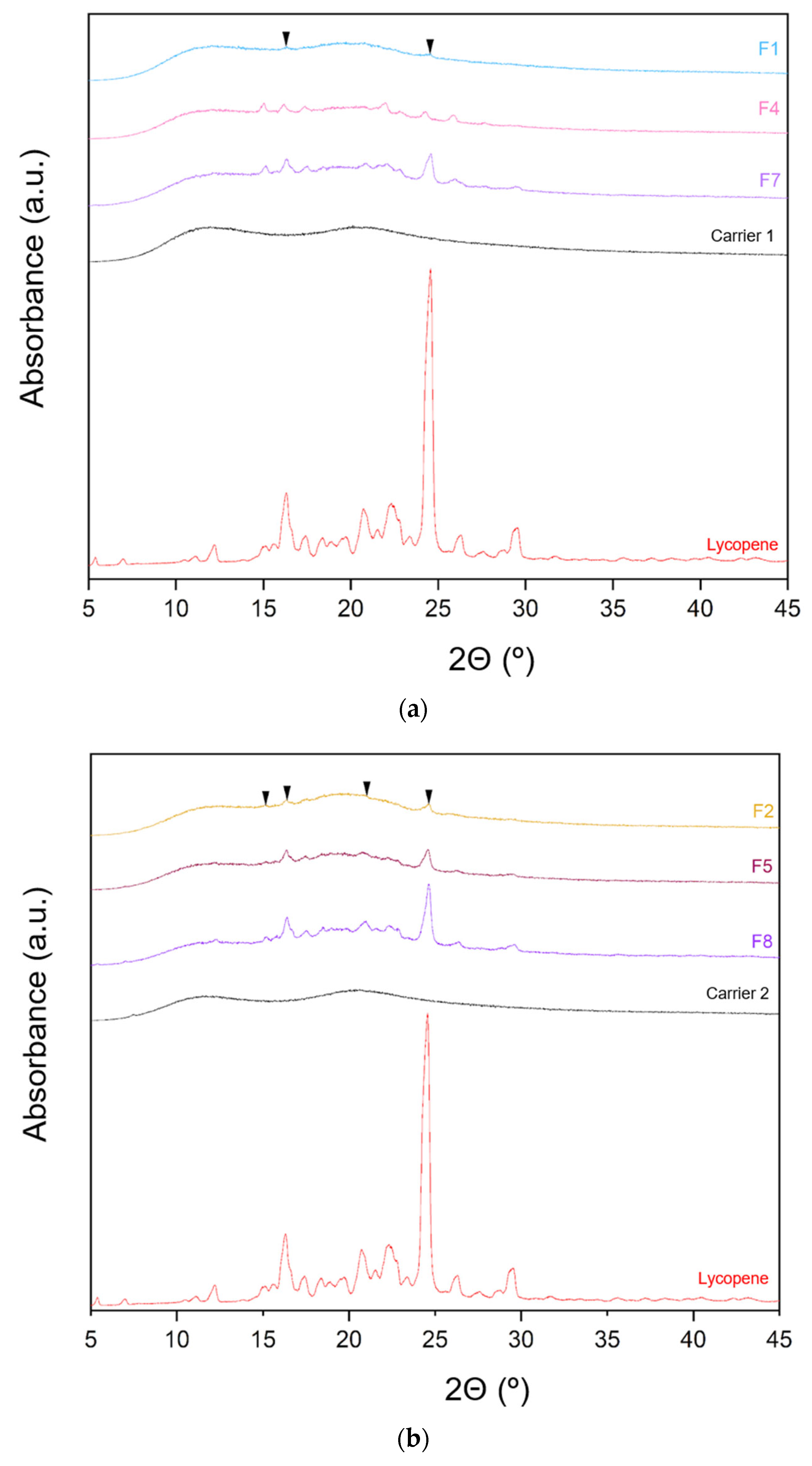

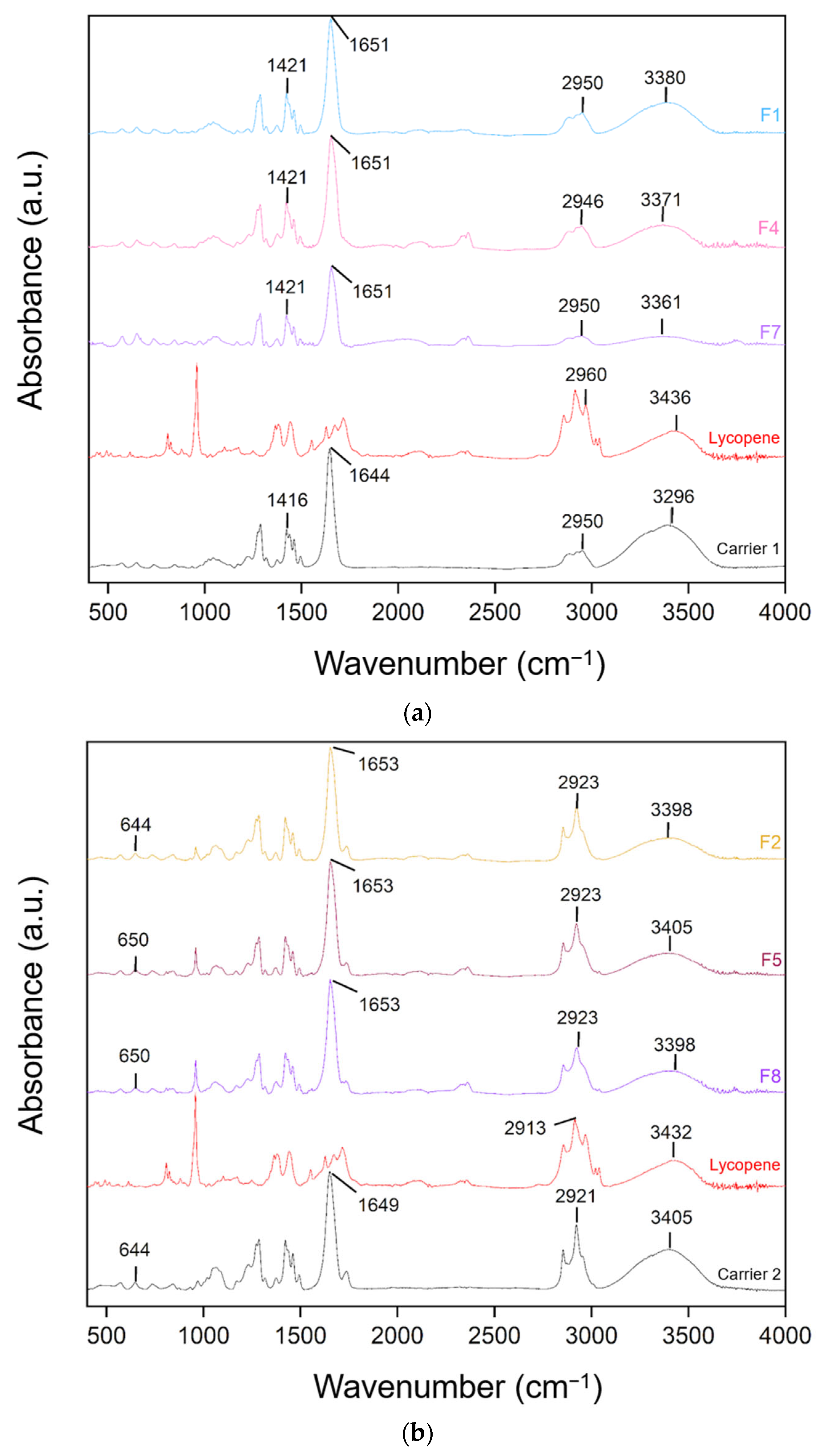

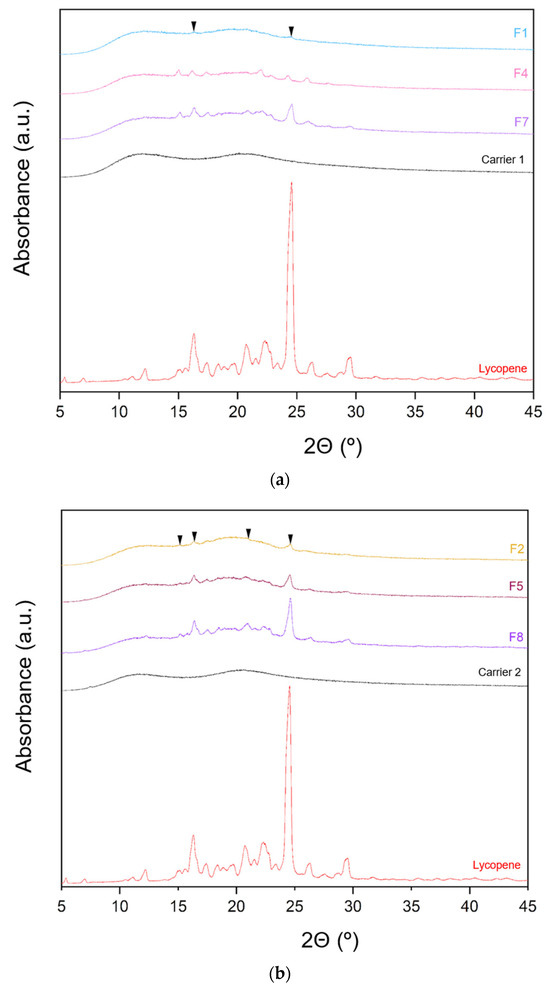

The XRPD patterns of lycopene, carriers and extrudates are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

XRPD analysis: (a) lycopene, carrier 1 and systems containing it: 1, 4 and 7; (b) lycopene, carrier 2 and systems containing it: 2, 5 and 8; (c) lycopene, carrier 3 and systems containing it: 3, 6 and 9.

XRPD analysis was performed to investigate whether the hot-melt extrusion process resulted in the formation of amorphous lycopene dispersions. The diffraction patterns of pure lycopene and the obtained extrudates were analyzed. Pure lycopene exhibited sharp peaks at 2θ angles of 12.9, 16.31, 17.41, 20.76, 22.30, 24.6, 26.33, and 29.46°, indicating its crystalline nature.

Analysis of the diffractograms for formulations F1–F9 revealed incomplete amorphization. Nevertheless, the hot-melt extrusion process led to a disappearance of sharp Bragg peaks, suggesting a reduction in the degree of crystallinity. Based on the obtained results, it can be concluded that formulations F1–F9 contained a mixture of crystalline and amorphous phases.

Formulations with the lowest lycopene content (F1, F2, and F3) exhibited the lowest degree of crystallinity, with F1 showing the least pronounced peaks. In F1, only minor peaks were observed at 2θ angles of 16.29 and 24.56°, while peaks indicative of the crystalline phase were more prominent in the remaining formulations.

3.6. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

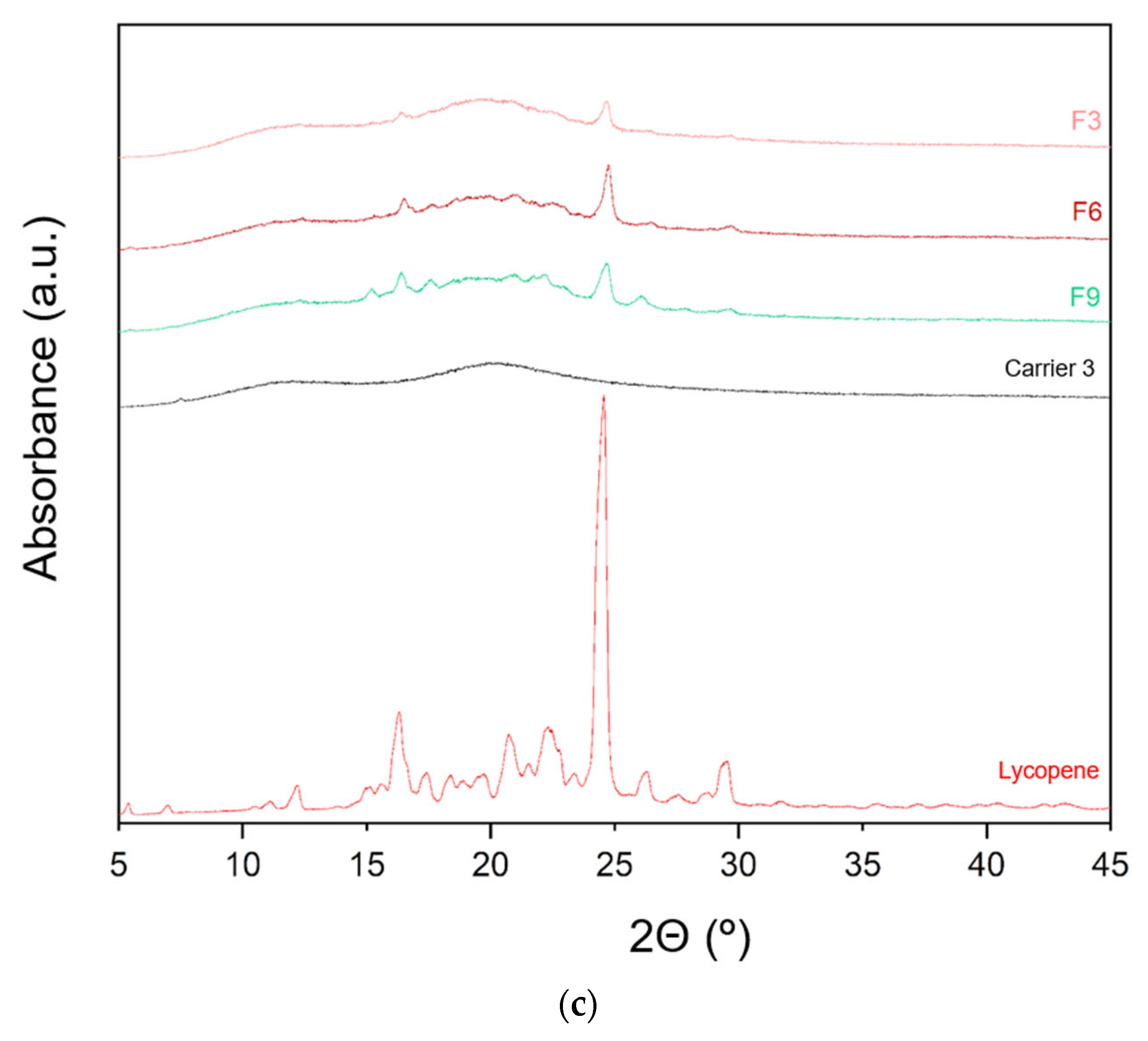

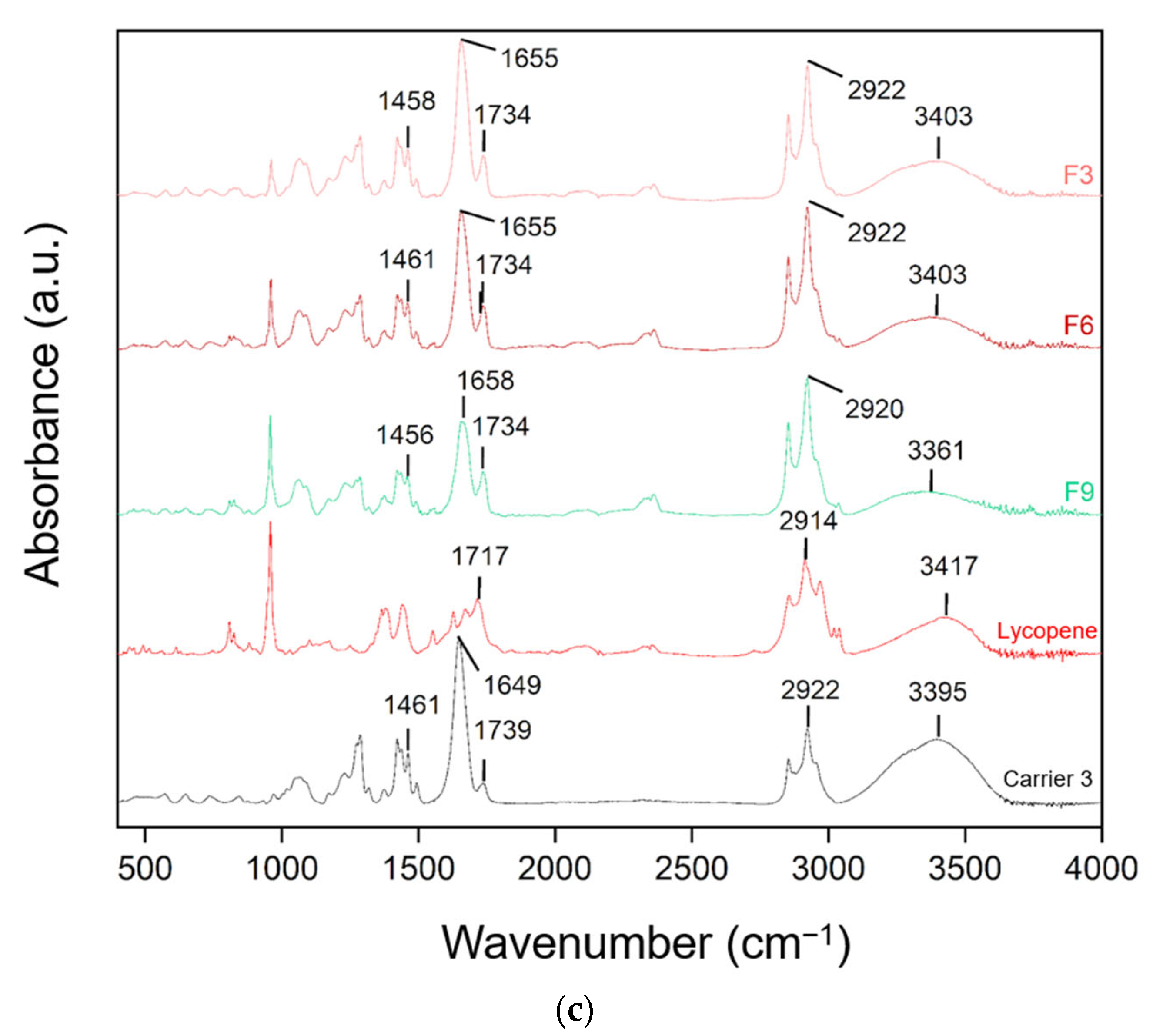

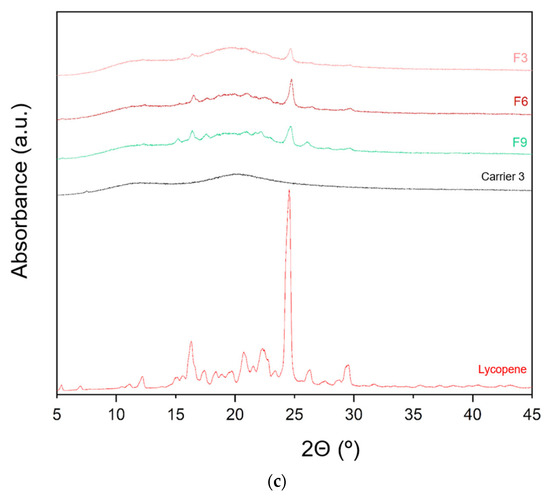

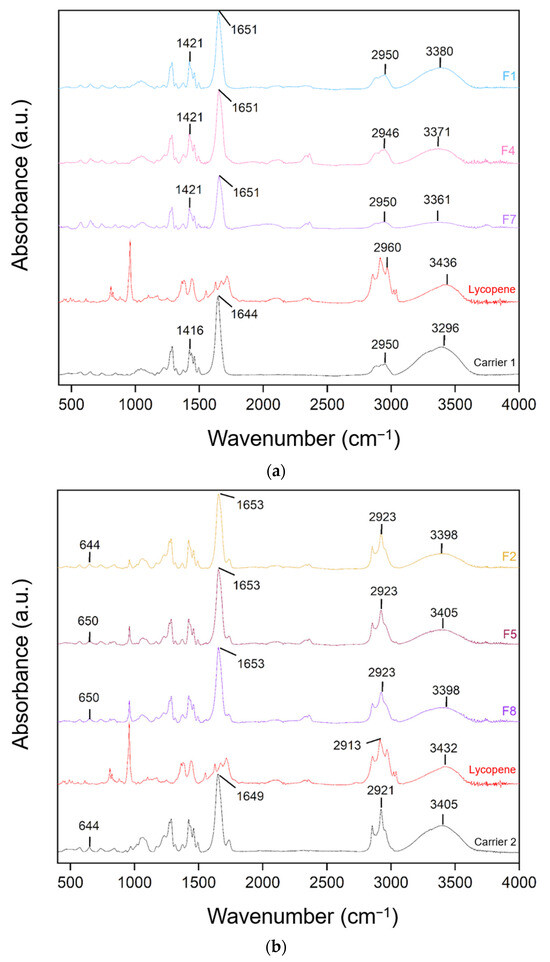

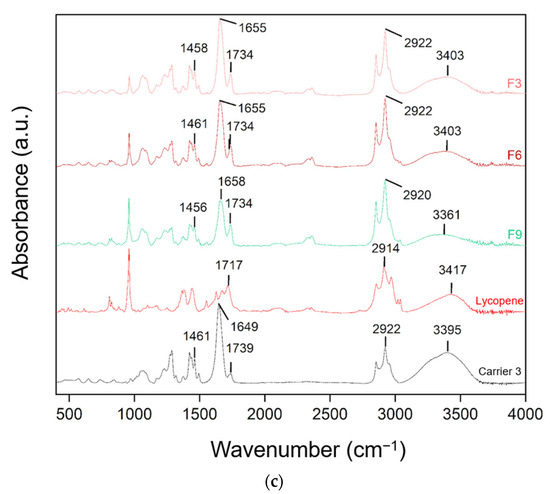

FT-IR spectra of lycopene, carriers and extrudates are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

FT-IR analysis: (a) lycopene, carrier 1 and systems containing it: 1, 4 and 7; (b) lycopene, carrier 2 and systems containing it: 2, 5 and 8; (c) lycopene, carrier 3 and systems containing it: 3, 6 and 9.

FT-IR analysis was conducted to identify potential molecular interactions by comparing the spectra of pure lycopene, the carriers, and the hot-melt extrudates. The spectra were grouped according to the type of carrier used. Changes in the positions and intensities of characteristic peaks were observed, suggesting possible molecular interactions.

For dispersions based on the PVP K30–xylitol–lycopene system, a broad band observed between 3250 and 3500 cm−1 corresponds mainly to residual water in the samples, rather than to structural vibrations of lycopene itself. In the carrier a broad peak was observed at 3296 cm−1 and in lycopene at 3418 cm−1 shifted to 3380 cm−1, 3371 cm−1, and 3361 cm−1 in formulations F1, F4, and F7, respectively. Peaks in the 3400–3200 cm−1 region are characteristic of hydroxyl groups. The peak at 1644 cm−1 in PVP K30 shifted to 1651 cm−1 in F1, F4, and F7, corresponding to the carbonyl group. Peaks at 1421 cm−1 in F1, F4, and F7 matched the peak at 1416 cm−1 in carrier 1.

For dispersions based on carrier 2, similar shifts were observed: the 3405 cm−1 peak of the carrier and 3432 cm−1 peak of lycopene corresponded to peaks at 3398 cm−1 in F2 and F8 and 3405 cm−1 in F5. The 1649 cm−1 peak of carrier 2 shifted to 1653 cm−1 in F2, F5, and F8. Additionally, the 644 cm−1 peak of the carrier shifted to 650 cm−1 in F5 and F8.

In dispersions based on carrier 3, peak shifts were also observed. The 2922 cm−1 peak of the carrier shifted to 2920 cm−1 in F9. The 1739 cm−1 peak of carrier 3 and 1717 cm−1 of lycopene corresponded to the 1739 cm−1 peak in F3, F6, and F9. The 1649 cm−1 peak of the carrier shifted to 1655 cm−1 in F3 and F6 and 1658 cm−1 in F9. Peaks at 1461 cm−1 in carrier 3 corresponded to 1458 cm−1 in F3 and 1456 cm−1 in F9.

Characteristic absorption peaks of lycopene were also observed and interpreted based on research data: C–H stretching vibrations in CH2 and CH3 groups at 2914 cm−1, C=C stretching vibrations in conjugated systems at 1627 and 1670 cm−1, C–H deformation vibrations in aliphatic hydrocarbon chains at 1442 cm−1, CH3 deformation vibrations at 1378 cm−1, and out-of-plane bending of =CH typical for trans-alkenes at 960 cm−1, characteristic of lycopene in its trans configuration [42]. Comparison of the obtained spectra with the literature allowed for assignment of the peaks to the corresponding structural fragments of the lycopene molecule.

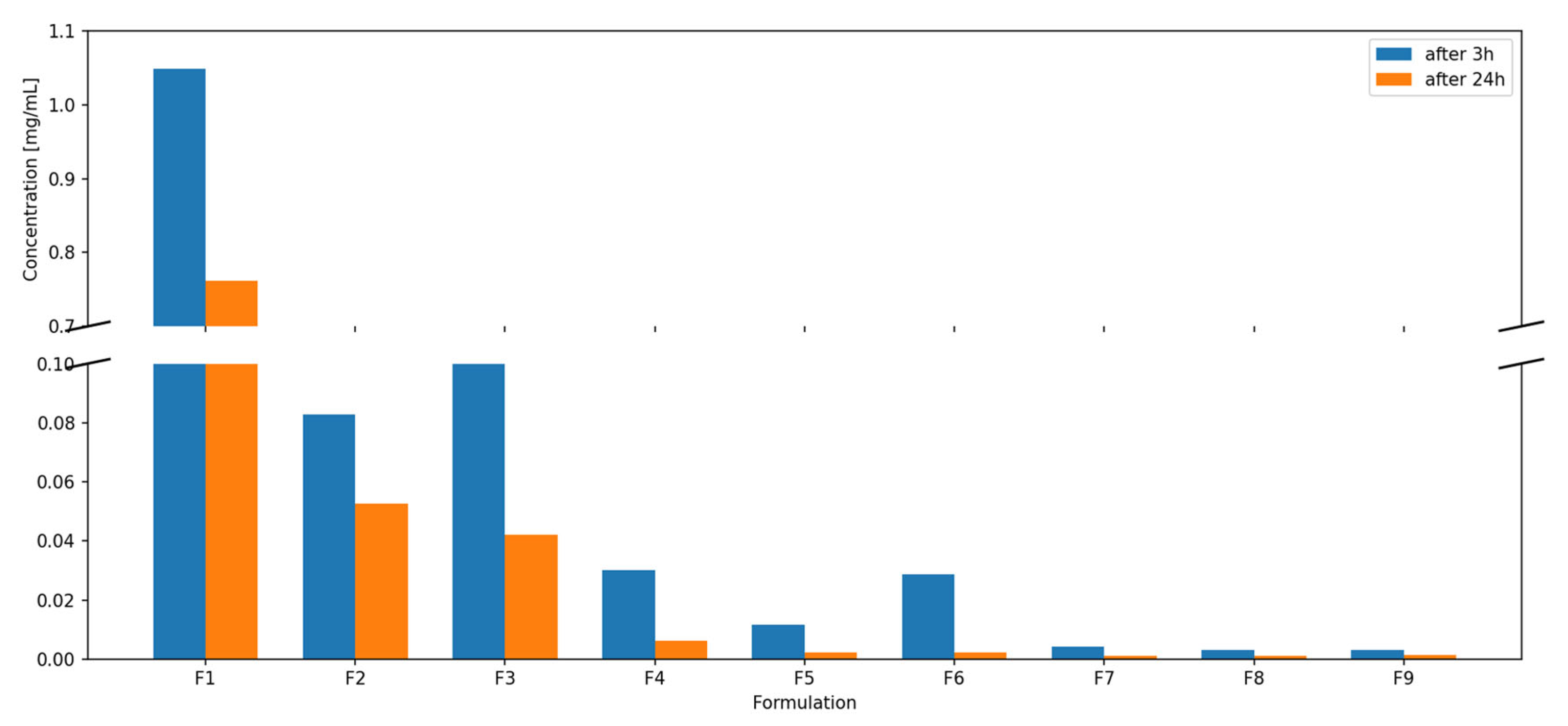

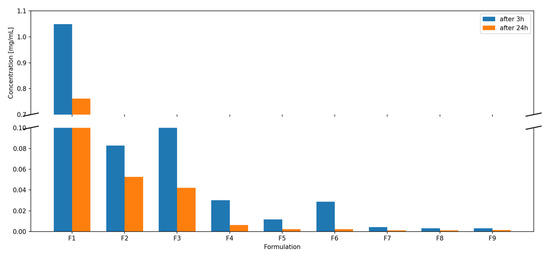

3.7. Dispersibility Study

Figure 8.

Lycopene dispersibility [mg/mL] at 3 h and 24 h.

Table 3.

Lycopene dispersibility [mg/mL] at 3 h and 24 h.

The highest lycopene dispersibility at both time points was observed for formulation F1, reaching 1.0484 mg/mL after 3 h and 0.7619 mg/mL after 24 h. This formulation did not contain phosphatidylcholine, and the unexpectedly high dispersibility is likely associated with limited compatibility of lycopene with the highly hydrophilic PVP–xylitol matrix, promoting partial phase segregation of lycopene toward the surface of the extrudate and facilitating its removal during dispersion and methanol extraction. Formulation F4, which also lacked phospholipid, showed increased dispersibility compared to formulations with the same lycopene content but containing phosphatidylcholine.

Dispersions F7, F8, and F9 exhibited similar, and the lowest, dispersibility values at both sampling times. Overall, dispersibility decreased with increasing lycopene content in the formulations. Dispersions F3 and F6, containing carrier 3, showed better dispersibility after 3 h than formulations with carrier 2 at the same lycopene content, but lower dispersibility compared to formulations containing carrier 1 (without phosphatidylcholine). A decrease in measured lycopene concentration over time was also observed.

4. Discussion

Recent advances in the formulation of carotenoids have highlighted the value of polymeric carriers in improving the solubility and dispersion of highly lipophilic molecules, such as lycopene. Among these carriers, PVP K30 has repeatedly been shown to enhance lycopene dissolution, irrespective of the processing technique. In our study, these known properties of PVP K30 are reflected in the improved dispersibility observed for PVP-based systems, confirming that the polymer effectively contributes to lycopene molecular dispersion in HME-processed matrices.

Hot-melt extrusion has also emerged as a powerful technique for generating amorphous or partially amorphous dispersions of poorly soluble active compounds. Its applicability to hydrophobic plant-derived molecules, including carotenoids, has been documented, particularly when amphiphilic or vinylpyrrolidone-based polymers are employed [43,44,45]. Prior research describing HME-processing of lycopene with carriers such as PVP K30, PVP VA64, Soluplus, cyclodextrin–PEG complexes, or even natural substrates like corn grit confirms that this method can be successfully adapted to structurally diverse excipients [31,46,47,48]. However, despite these promising examples, the overall number of studies investigating lycopene dispersions produced specifically via HME remains relatively low. Our work therefore expands the existing evidence by employing PVP K30 in combination with xylitol and phosphatidylcholine to design novel carrier systems tailored to increase lycopene dispersibility.

Phospholipids are frequently incorporated into formulations of poorly water-soluble compounds because their amphiphilic structure enables the formation of supramolecular assemblies, such as micelles or mixed aggregates, which can promote dissolution and improve membrane permeability [34]. In our formulations, however, phosphatidylcholine reduced the dispersibility and did not stabilize the amorphous fraction, indicating that its softening effect may limit lycopene incorporation into the matrix.

In the context of hot-melt extrusion, phospholipids are therefore typically used as functional additives rather than stand-alone carriers. Their inclusion can modulate permeability and dispersibility, but they may also soften the matrix, alter rheological behavior, or reduce the stability of the amorphous phase. These considerations are reflected in our results, where the presence of phosphatidylcholine did not improve lycopene dispersion stability and, in several cases, led to lower dispersibility compared to polymer–polyol systems. This suggests that while phospholipids offer valuable biopharmaceutical advantages, their processing behavior and structural influence must be carefully controlled when designing HME formulations.

Sugar alcohols such as xylitol represent another category of excipients with functional benefits in HME. The FT-IR shifts observed in our work directly support the formation of interactions between xylitol, PVP K30, and lycopene, which likely contributed to better stabilization of the amorphous fraction and higher dispersibility. The superior dispersibility obtained for formulations lacking phosphatidylcholine but containing xylitol indicates that polymer–polyol systems provide a more favorable environment for lycopene dispersion than polymer–phospholipid matrices. This is consistent with the hypothesis that xylitol contributes both to improved processing characteristics and to kinetic stabilization against recrystallization.

The present study demonstrates that hot-melt extrusion is a promising technique for enhancing the dispersibility of lycopene, although the amorphization of this highly crystalline carotenoid remains challenging. The thermal analysis performed to evaluate the inherent ability of lycopene to form an amorphous phase revealed a pronounced tendency for recrystallization, regardless of the applied cooling rate. These findings indicate that lycopene is a compound with low glass-forming ability. The poor amorphization capacity observed here highlights the importance of selecting an appropriate carrier matrix capable of inhibiting recrystallization during and after processing.

The DSC and XRPD analyses collectively confirmed only partial amorphization of lycopene within the extruded dispersions. In all formulations, endothermic events close to the melting point of lycopene were detected, indicating the persistence of crystalline domains. Importantly, the melting peaks recorded in the formulations were shifted relative to pure lycopene, suggesting the presence of interactions between lycopene and the carrier components. Such interactions may alter the crystallization behavior of the active compound and explain the reduced but still detectable crystallinity observed in the XRPD diffractograms. The XRPD results further suggest that partial recrystallization could occur during storage prior to measurement, which is consistent with the low glass-forming ability observed in the preliminary DSC analysis. Higher lycopene loadings additionally weakened the ability of the polymeric matrix to inhibit crystallization, resulting in more pronounced residual peaks and confirming that lycopene content is a critical factor in achieving stable amorphous dispersions.

These findings are consistent with our earlier work, in which we also demonstrated, using PVP VA64- and Soluplus-based extrudates, that the XRPD patterns of lycopene-containing systems predominantly reflected the amorphous halo of the carrier polymer. In those studies, all extrudates, regardless of polymer type or extract content (10–40%), exhibited diffractograms characteristic of the polymer matrix, confirming complete dispersion of the extract. Similar to the present results, increases in extract concentration resulted in changes in peak intensities, suggesting subtle differences in ordering within the system, particularly at higher lycopene loads [48].

In our previous study, we reported that lycopene incorporated into PVP K30 at 5–15% concentrations by ball milling showed complete loss of crystallinity, as confirmed by XRPD patterns free of Bragg peaks and DSC thermograms lacking lycopene melting transitions. The appearance of glass transition events and concentration-dependent depression further supported successful molecular dispersion of lycopene in the polymer [30].

In contrast, the hot-melt extruded systems developed in the present work exhibited only partial amorphization. Several factors may explain the less efficient amorphization versus ball milling. First, lycopene displayed limited intrinsic ability to form an amorphous phase, as demonstrated by DSC experiments performed at different cooling rates, where recrystallization occurred even at rapid cooling (40 K/min). Second, phosphatidylcholine, unlike pure PVP K30, showed only a minor plasticizing effect and may have hindered molecular dispersion of lycopene within the carrier. Finally, higher lycopene contents (20–30%) likely exceeded the dispersibility capacity of the polymeric matrix, consistent with the increasing crystallinity observed in F4–F9.

In our previous extrusion study using acetone-extracted lycopene with PVP VA64 and Soluplus, a similar pattern was observed in DSC analysis: the characteristic polymer endotherms remained visible in all extrudates, but their intensities decreased and shifted to lower temperatures with increasing extract content. This was interpreted as evidence of good, but not complete, molecular dispersion of the lycopene extract within the polymer matrix, mirroring the incomplete amorphization found in the present work [48].

Ma et al. [46] demonstrated that lycopene incorporated into HP-β-CD or PEG systems prepared by hot-melt extrusion underwent complete amorphization, as shown by the disappearance of its melting peak and the absence of XRPD reflections. In contrast, our extrudates still exhibited a detectable melting transition and retained weakened crystalline peaks, indicating that the carriers used in our study do not stabilize lycopene to the same extent as the HME-processed cyclodextrin systems described by MA.

Mirahmadi et al. [31] also reported that solubilizer–lycopene mixtures obtained via hot-melt extrusion did not show the characteristic melting endotherm, suggesting complete amorphization or strong melting-point depression. In our case, however, DSC thermograms consistently showed residual melting events, and XRPD confirmed the presence of crystalline regions. This indicates that the excipients used in our HME formulations were less effective in eliminating crystallinity than the solubilizers assessed by Mirahmadi et al.

FT-IR spectroscopy provided complementary evidence for molecular interactions in the prepared systems. Shifts in the hydroxyl and carbonyl stretching regions indicate intermolecular bonding between lycopene and both PVP K30 and xylitol. These interactions may contribute to kinetic stabilization of the amorphous fraction by restricting molecular mobility and hindering the formation of an ordered crystalline lattice. Although phosphatidylcholine also participated in intermolecular interactions, its presence did not improve dispersion stability or dispersibility. In fact, formulations lacking phosphatidylcholine (F1 and F4) exhibited superior performance. This observation suggests that polymer–polyol systems create a more favorable microenvironment for lycopene dispersion compared to polymer–phospholipid combinations, possibly due to the higher hydrogen-bonding capacity of xylitol and its stronger plasticizing effect on PVP.

In our previous study with lycopene–PVP K30 systems prepared by ball milling, we also observed shifts in the carbonyl stretching band of PVP K30 and the disappearance of lycopene-specific signals in amorphous systems, indicating non-covalent stabilization, particularly through dipole-induced dipole interactions [30].

Our earlier extrusion work also confirmed that no new covalent bonds were formed during processing. FT-IR spectra of the extract, polymers, physical mixtures, and extrudates showed no new absorption bands in the 400–1800 cm−1 region. Only a reduction and slight shift in the broad ~3312 cm−1 band, associated with water in the extract, was observed in extrudates [48]. This behaviour is consistent with reduced water content and modified hydrogen-bonding interactions upon dispersion of the extract, agreeing closely with the interaction pattern described in the present study.

In the HME-processed systems studied by Ma et al. [46], FTIR spectra displayed pronounced peak shifts attributed to hydrogen bonding between lycopene and HP-β-CD, which contributed to full amorphization. In our HME formulations, the FTIR shifts were more subtle, suggesting weaker interactions, consistent with the only partial loss of crystallinity observed by DSC and XRPD.

Mirahmadi et al. [31] showed that lycopene–solubilizer systems produced via HME exhibited substantial FTIR changes, reflecting strong hydrogen-bonding or carbonyl-mediated interactions responsible for amorphization. In contrast, our spectra revealed only modest band shifts. Although these indicate some interaction with PVP K30, phosphatidylcholine, and xylitol, the strength of these interactions appears insufficient to prevent recrystallization, which aligns with our thermal and diffraction findings.

The dispersibility results further emphasize the importance of carrier composition. Formulation F1, containing PVP K30 and xylitol without phosphatidylcholine, achieved the highest dispersibility at both 3 h and 24 h, exceeding 1 mg/mL at the initial time point. However, these results should not be interpreted as improved stabilization by the hydrophilic carrier. Instead, the absence of phosphatidylcholine likely reduces the formation of hydrophobic microdomains within the matrix, leading to weaker affinity between lycopene and the carrier. Consequently, lycopene may undergo partial phase separation and accumulate near the extrudate surface, which increases its apparent dispersibility and facilitates its extraction into methanol during HPLC analysis. Systems containing phosphatidylcholine demonstrated lower dispersibility, consistent with the formation of hydrophobic domains able to better retain lycopene within the matrix. The consistent inverse relationship between lycopene content and dispersibility also reflects the diminishing ability of the carrier to stabilize higher drug loads, leading to greater crystallinity and reduced dissolution rates. The decrease in measured lycopene concentration after 24 h suggests precipitation from the supersaturated state, likely driven by ongoing recrystallization in solution—a phenomenon frequently observed for compounds with low amorphous stability.

Consistent with our observations, Mirahmadi et al. [31] reported that employing solid dispersion strategies with polymers such as PVP-K30 markedly enhances the dissolution behavior of lycopene. In their work, formulations based on PVP and isolated whey protein improved the compound’s bioavailability. These outcomes align with our findings, where the use of polymers similarly increased lycopene’s dispersibility.

In our previous study we used lycopene–PVP K30 dispersions prepared by ball milling. We reported dispersibility values of 0.372 mg/mL (5% lycopene), 0.210 mg/mL (10% lycopene), and 0.064 mg/mL (15% lycopene) after 2 h, with all systems showing marked decreases after 24 h. These results are consistent with complete amorphization and polymer-mediated stabilization in aqueous media [30].

In the present study, dispersibility values varied more widely. The most promising formulation, F1 (10% lycopene, phosphatidylcholine-free), exhibited remarkably high dispersibility: 1.0484 mg/mL (3 h) and 0.7619 mg/mL (24 h), substantially exceeding the values reported in our previous study. Such enhancement is most likely related not only to the presence of xylitol but also to reduced lycopene–matrix compatibility in the absence of phosphatidylcholine, promoting surface localization of the hydrophobic compound and thus increasing the measured dispersibility. However, formulations containing phosphatidylcholine (F2–F9) showed lower dispersibility, indicating that phospholipid addition reduced carrier hydration and lycopene release. Additionally, higher lycopene loading (30%) led to minimal dispersibility improvements, consistent with incomplete amorphization and the presence of crystalline residues.

In our earlier extrusion experiments with PVP VA64 and Soluplus, we similarly demonstrated that polymer type and content play a decisive role in lycopene dissolution. The acetone extract alone reached only about 1% release under acidic conditions, whereas combining it with PVP VA64 or Soluplus markedly increased dissolution. For example, the 10% extract/90% PVP VA64 extrudate achieved a 34% dissolution rate, and the corresponding Soluplus extrudate reached 31%. These results align with the present finding that dissolution enhancement arises not only from amorphization but also from improved wetting, dispersibility, and polymer–matrix interactions [48]. The parallels between both studies reinforce the conclusion that high polymer content is critical for efficient lycopene release.

While the systems prepared in our previous studies showed more consistent amorphization, the best-performing formulation in the current study achieved substantially higher dispersibility, highlighting that amorphization is not the only determinant of dissolution performance. Matrix hydrophilicity, carrier composition, and extrudate morphology likely played a significant role.

Overall, this study demonstrates that hot-melt extrusion can yield solid dispersions with significantly improved dispersibility when suitable carrier systems are applied. Polymer–polyol matrices based on PVP K30 and xylitol proved most effective, facilitating partial amorphization, promoting stabilizing intermolecular interactions, and providing the highest dispersibility enhancement. These findings underscore the potential of HME technology for modifying the physicochemical properties of highly crystalline carotenoids and support the further exploration of polymeric and polyol-based carriers to enhance lycopene bioavailability. Future studies should focus on long-term physical stability, the kinetics of recrystallization during storage and dissolution, and in vitro–in vivo correlations to elucidate the extent to which improved dispersibility translates into enhanced biological activity.

5. Conclusions

Hot-melt extrusion proved to be an effective technique for obtaining lycopene dispersions with modified physicochemical properties. The process conditions (150 °C, 90 rpm) ensured thermal stability of the compound, as confirmed by thermogravimetric analysis. DSC and XRPD analyses indicated that the extrusion process led to a reduction in the crystalline phase of lycopene, resulting in partially amorphous dispersions. FT-IR spectroscopy revealed shifts in characteristic absorption bands, suggesting the occurrence of molecular interactions between lycopene and excipients, particularly involving hydroxyl and carbonyl groups.

The composition of the carrier system had a significant influence on the dispersibility of lycopene. The highest dispersibility values were recorded for formulations containing PVP K30 and xylitol without phosphatidylcholine, indicating that the polymer–polyol combination provided better stabilization of lycopene in the amorphous form. Increasing lycopene content in the formulations resulted in a marked decrease in dispersibility.

These findings demonstrate that while partial amorphization can be achieved via HME, complete amorphization of lycopene is challenging due to its low glass-forming ability and tendency for recrystallization. The results underscore that the dissolution performance of lycopene is not solely determined by amorphization, but also by carrier hydrophilicity, polymer–polyol interactions, and potential phase segregation, which can enhance apparent dispersibility.

Moreover, this study provides insights into the role of individual excipients: xylitol contributed both to plasticization of PVP K30 and to hydrogen-bond-mediated stabilization of lycopene, while phosphatidylcholine, despite forming molecular interactions, did not improve dispersibility and may limit lycopene release due to hydrophobic domain formation. This highlights the importance of carefully balancing carrier composition to optimize both processability and functional performance.

From a practical perspective, these results suggest that polymer–polyol-based HME formulations may serve as a promising approach for improving the oral bioavailability of lycopene, particularly when phospholipids are omitted or used in controlled proportions. Future studies should focus on long-term physical stability, recrystallization kinetics, optimization of polymer-to-lycopene ratios, and in vitro–in vivo correlation studies to assess how enhanced dispersibility translates into increased biological efficacy.

In conclusion, the current work not only confirms the feasibility of HME for lycopene formulation but also emphasizes the nuanced interplay between carrier selection, excipient functionality, and processing parameters in achieving optimal dispersibility and potential bioavailability enhancement. This comprehensive understanding can guide the rational design of carotenoid delivery systems and inform future applications in nutraceutical and pharmaceutical products.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K., J.C.-P. and P.Z.; methodology, J.C.-P. and P.Z.; investigation, A.K. and P.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K., K.W., N.R., M.P.-W. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, J.C.-P. and P.Z.; supervision, J.C.-P. and P.Z.; project administration, J.C.-P. and P.Z.; funding acquisition, J.C.-P. and P.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland, grant number DWD/6/0002/2022.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Figures adapted from Servier Medical Art https://smart.servier.com/ (accessed on 24 November 2025), licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Conflicts of Interest

Author Anna Kulawik was employed by Phytopharm Klęka S.A., Klęka 1, 63-040 Nowe Miasto nad Wartą, Poland. The remaining authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Imran, M.; Ghorat, F.; Ul-Haq, I.; Ur-Rehman, H.; Aslam, F.; Heydari, M.; Shariati, M.A.; Okuskhanova, E.; Yessimbekov, Z.; Thiruvengadam, M.; et al. Lycopene as a Natural Antioxidant Used to Prevent Human Health Disorders. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Zhu, H.; Wang, S.; Xing, J. Inclusion Complexes of Lycopene and β-Cyclodextrin: Preparation, Characterization, Stability and Antioxidant Activity. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulawik, A.; Cielecka-Piontek, J.; Zalewski, P. The Importance of Antioxidant Activity for the Health-Promoting Effect of Lycopene. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Jumah, M.N.; Nadeem, M.S.; Gilani, S.J.; Mubeen, B.; Ullah, I.; Alzarea, S.I.; Ghoneim, M.M.; Alshehri, S.; Al-Abbasi, F.A.; Kazmi, I. Lycopene: A Natural Arsenal in the War against Oxidative Stress and Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulawik, A.; Rosiak, N.; Miklaszewski, A.; Cielecka-Piontek, J.; Zalewski, P. Investigation of Cyclodextrin as Potential Carrier for Lycopene. Arch. Pharm. 2024, 74, 178–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowska, M.; Wawrzyniak, D.; Rolle, K.; Chomczyński, P.; Oziewicz, S.; Jurga, S.; Barciszewski, J. Let Food Be Your Medicine: Nutraceutical Properties of Lycopene. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 3090–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, A.d.G.N.; Vasconcelos, A.G.; Souza, J.; Oliveira, A.; Gullón, B.; de Souza de Almeida Leite, J.R.; Pintado, M. Bio-Availability, Anticancer Potential, and Chemical Data of Lycopene: An Overview and Technological Prospecting. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wu, Y.; Cui, Z.; Hu, L. Nutraceutical Delivery Systems to Improve the Bioaccessibility and Bioavailability of Lycopene: A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 6361–6379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, G.C.; Sábio, R.M.; Chorilli, M. An Overview of Properties and Analytical Methods for Lycopene in Organic Nanocarriers. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2021, 51, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leh, H.E.; Lee, L.K. Lycopene: A Potent Antioxidant for the Amelioration of Type II Diabetes Mellitus. Molecules 2022, 27, 2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulawik, A.; Cielecka-Piontek, J.; Czerny, B.; Kamiński, A.; Zalewski, P. The Relationship Between Lycopene and Metabolic Diseases. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, N.; Patani, P.; Singhvi, I. A Review on Tomato Lycopene. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2018, 9, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wdowiak, K.; Pietrzak, R.; Tykarska, E.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Hot-Melt Extrusion as an Effective Technique for Obtaining an Amorphous System of Curcumin and Piperine with Improved Properties Essential for Their Better Biological Activities. Molecules 2023, 28, 3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, Y.; Tin, Y.-Y.; Soe, M.-T.-P.; Ko, B.; Park, S.; Lee, J. Recent Technologies for Amorphization of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiang, W.; Löbmann, K.; McCoy, C.P.; Andrews, G.P.; Zhao, M. Microwave-Induced In Situ Amorphization: A New Strategy for Tackling the Stability Issue of Amorphous Solid Dispersions. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, S.M.; Lu, W.; Park, J.-B.; Morott, J.T.; Alsulays, B.B.; Majumdar, S.; Langley, N.; Kolter, K.; Gryczke, A.; Repka, M.A. Stability-Enhanced Hot-Melt Extruded Amorphous Solid Dispersions via Combinations of Soluplus® and HPMCAS-HF. AAPS PharmSciTech 2015, 16, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Censi, R.; Gigliobianco, M.R.; Casadidio, C.; Di Martino, P. Hot Melt Extrusion: Highlighting Physicochemical Factors to Be Investigated While Designing and Optimizing a Hot Melt Extrusion Process. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.V.; Patil, H.; Repka, M.A. Contribution of Hot-Melt Extrusion Technology to Advance Drug Delivery in the 21st Century. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2016, 13, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, M.F.; Pinto, R.M.A.; Simões, S. Hot-Melt Extrusion in the Pharmaceutical Industry: Toward Filing a New Drug Application. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 1749–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, H.; Tiwari, R.V.; Repka, M.A. Hot-Melt Extrusion: From Theory to Application in Pharmaceutical Formulation. AAPS PharmSciTech 2016, 17, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repka, M.A.; Bandari, S.; Kallakunta, V.R.; Vo, A.Q.; McFall, H.; Pimparade, M.B.; Bhagurkar, A.M. Melt Extrusion with Poorly Soluble Drugs—An Integrated Review. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 535, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-Y.; Hsieh, Y.-S.; Ko, H.-H.; Wu, Y.-T. Formulation Approaches to Crystalline Status Modification for Carotenoids: Impacts on Dissolution, Stability, Bioavailability, and Bioactivities. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurakula, M.; Koteswara Rao, G.S.N. Moving Polyvinyl Pyrrolidone Electrospun Nanofibers and Bioprinted Scaffolds toward Multidisciplinary Biomedical Applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 136, 109919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurakula, M.; Rao, G.S.N.K. Pharmaceutical Assessment of Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP): As Excipient from Conventional to Controlled Delivery Systems with a Spotlight on COVID-19 Inhibition. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 60, 102046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koczkur, K.M.; Mourdikoudis, S.; Polavarapu, L.; Skrabalak, S.E. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) in Nanoparticle Synthesis. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 17883–17905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, R.C.; Sheskey, P.J.; Quinn, M.E. Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients, 6th ed.; Pharmaceutical Press: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-85369-792-3. [Google Scholar]

- Javadzadeh, Y.; Jafari-Navimipour, B.; Nokhodchi, A. Liquisolid Technique for Dissolution Rate Enhancement of a High Dose Water-Insoluble Drug (Carbamazepine). Int. J. Pharm. 2007, 341, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molaei, M.-A.; Osouli-Bostanabad, K.; Adibkia, K.; Shokri, J.; Asnaashari, S.; Javadzadeh, Y. Enhancement of Ketoconazole Dissolution Rate by the Liquisolid Technique. Acta Pharm. 2018, 68, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, C.; He, Y.; Duan, B.; Yang, G.; Ma, W.; Zhang, Y. Factors Affecting the Dissolution of Indomethacin Solid Dispersions. AAPS PharmSciTech 2017, 18, 3258–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulawik, A.; Kulawik, M.; Rosiak, N.; Lu, W.; Cielecka-Piontek, J.; Zalewski, P. Amorphous Lycopene–PVP K30 Dispersions Prepared by Ball Milling: Improved Solubility and Antioxidant Activity. Polymers 2025, 17, 2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirahmadi, M.; Kamali, H.; Azimi-Hashemi, S.; Lavaee, P.; Gharaei, S.; Sherkatsadi, K.; Pourhossein, T.; Baharara, H.; Nejabat, M.; Ghafourian, T.; et al. Evaluation of Novel Carriers for Enhanced Dissolution of Lycopene. Food Meas. 2024, 18, 4718–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurav, P.P.; Mhaske, M.P.; Sayyad, S.F.; Chavan, M.J. Solubility Enhancement of Lycopene by Lyophilized Polymeric Nanoparticles. Adv. Biores. 2021, 12, 177–191. Available online: https://soeagra.com/abr/abr_jan2021/23.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- Shahverdi, F.; Khodaverdi, E.; Movaffagh, J.; Tafazzoli Mehrjardi, S.; Kamali, H.; Nokhodchi, A. Lycopene-Carrier Solid Dispersion Loaded Lipid Liquid Crystal Nanoparticle: In Vitro Evaluation and in Vivo Wound Healing Effects. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2025, 30, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghule, T.; Saha, R.N.; Alexander, A.; Singhvi, G. Tailoring the Multi-Functional Properties of Phospholipids for Simple to Complex Self-Assemblies. J. Control. Release 2022, 349, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Chen, H.; Sun, L.; Tong, L.; Zhang, T. Improving Permeability and Oral Absorption of Mangiferin by Phospholipid Complexation. Fitoterapia 2014, 93, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, K.; Mukherjee, K.; Gantait, A.; Saha, B.P.; Mukherjee, P.K. Curcumin–Phospholipid Complex: Preparation, Therapeutic Evaluation and Pharmacokinetic Study in Rats. Int. J. Pharm. 2007, 330, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Dong, W.; Ye, J.; Hao, H.; Zhou, J.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y. A Novel Matrix Dispersion Based on Phospholipid Complex for Improving Oral Bioavailability of Baicalein: Preparation, in Vitro and in Vivo Evaluations. Drug Deliv. 2017, 24, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann-Trettenes, U.; Barnert, S.; Bauer-Brandl, A. Single Step Bottom-up Process to Generate Solid Phospholipid Nano-Particles. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2014, 19, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, K.; Cho, J.M.; Lee, H.; Kim, E.K.; Kim, H.C.; Kim, H.; Lee, J. Enhancement of Aqueous Solubility and Dissolution of Celecoxib through Phosphatidylcholine-Based Dispersion Systems Solidified with Adsorbent Carriers. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wdowiak, K.; Tajber, L.; Miklaszewski, A.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Sweeteners Show a Plasticizing Effect on PVP K30—A Solution for the Hot-Melt Extrusion of Fixed-Dose Amorphous Curcumin-Hesperetin Solid Dispersions. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wdowiak, K.; Tajber, L.; Miklaszewski, A.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Application of the Box–Behnken Design in the Development of Amorphous PVP K30–Phosphatidylcholine Dispersions for the Co-Delivery of Curcumin and Hesperetin Prepared by Hot-Melt Extrusion. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, D.; Keddari, S.; Boufadi, M.Y.; Bessad, L. Lycopene Purification with DMSO Anti-Solvent: Optimization Using Box-Behnken’s Experimental Design and Evaluation of the Synergic Effect between Lycopene and Ammi visnaga L. Essential Oil. Chem. Pap. 2022, 76, 6335–6347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.; Bates, S.; Engers, D.A.; Leach, K.; Schields, P.; Yang, Y. Effect of Water Vapor Sorption on Local Structure of Poly(Vinylpyrrolidone). J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 99, 3815–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosiak, N.; Tykarska, E.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Enhanced Antioxidant and Neuroprotective Properties of Pterostilbene (Resveratrol Derivative) in Amorphous Solid Dispersions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Bielinski, D.F.; Fisher, D.R.; Zhang, J.; Shukitt-Hale, B. Protective Effects of a Polyphenol-Rich Blueberry Extract on Adult Human Neural Progenitor Cells. Molecules 2022, 27, 6152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhong, L.; Peng, Z.; Liu, X.; Ouyang, D.; Guan, S. Development of a Highly Water-Soluble Lycopene Cyclodextrin Ternary Formulation by the Integrated Experimental and Modeling Techniques. AAPS PharmSciTech 2021, 22, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonyali, B.; Sensoy, I.; Karakaya, S. The Effect of Extrusion on the Functional Components and in Vitro Lycopene Bioaccessibility of Tomato Pulp Added Corn Extrudates. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulawik, A.; Kulawik, M.; Rosiak, N.; Lu, W.; Kryszak, A.; Cielecka-Piontek, J.; Zalewski, P. Improving the Pharmaceutical Potential of Lycopene Using Hot-Melt Extrusion. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.