Featured Application

The findings of this paper lay the groundwork for wind field assessment of UAVs and their flight path planning in the future.

Abstract

To assess UAV (Unmanned Aerial Vehicle) flight stability in urban wind fields, this study conducted numerical simulations of urban scene and logistics UAV models and developed a wind field safety level evaluation model for UAV flight paths. First, urban wind field structures were analyzed with simulations of typical building clusters. Second, the UAV’s aerodynamic characteristics under vertical balance were elaborated. Third, sideslip angles and wind speeds were adjusted based on the UAV’s maximum wind resistance to explore aerodynamic performance variations across conditions. Finally, a safety level calculation method was proposed to determine the wind field safety distribution along target paths. The results show that building layouts significantly affect urban wind fields, forming wind acceleration zones beside high-rises and between some buildings. The acceleration effect at 25 m is stronger than at 10 m and 50 m. UAV aerodynamic moments vary greatly with wind sideslip angles, with the dangerous angle being around 150°. Flight stability and wind field structures differ notably by path and height. This evaluation method enables UAVs to avoid high-risk areas, improving urban flight stability.

1. Introduction

With the development of the low-altitude economy [1], in-depth enhancement by information and digital management technologies is accelerating the evolution of UAM (Urban Air Mobility) and an integrated low-altitude flight system [2,3]. As the core application carrier of low-altitude engineering, the operational safety and reliability of UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles) directly determine the industrial development level. Wind resistance, a critical indicator for UAVs’ operations in urban scenarios, serves as the “safety cornerstone” for the implementation of the low-altitude economy. Currently, civil UAVs in China have been used in several fields, such as precision operations in agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fishery, as well as recreational aerial photography. However, high-frequency and rigid-demand applications in cities, including delivery in core business districts and community air services, are still constrained by the challenges of complex wind fields. The research on aerodynamic stability has become a key technical target.

From a technical perspective, aerodynamic stability serves as the core foundation for UAVs’ wind resistance, and the lack of scenario research will directly render wind resistance design unsubstantiated [4]. Constrained by volume, payload, and power output, lightweight UAVs cannot solely rely on power systems to counteract disturbances from complex urban wind fields. Their wind resistance essentially depends on the compatibility between aerodynamic configuration and flow fields. Only through precise aerodynamic stability research can the variation laws of lift, drag, and aerodynamic moments of UAVs under different wind speeds, directions, and turbulent environments be quantitatively analyzed and the critical conditions for attitude instability be clarified, providing core data support for airfoil optimization, body design, and flight control algorithm iteration [5]. Without this fundamental research on urban wind fields, UAVs’ wind-resistant design remains experience-based, unable to address the uncertainty of urban wind fields.

From the perspective of scenario implementation, research on aerodynamic stability is a core requirement of UAVs’ flight in urban environments. Urban wind fields exhibit high complexity and uncertainty due to factors such as building distribution, height differences, and street orientations: complex flow fields easily form around high-rises, including backflow and eddy currents, with wind speeds at locations like building base air vents and inter-building channels reaching twice or more the ground level [6]. Currently, low-altitude UAV route planning is primarily based on ground morphology, population density, and existing transportation infrastructure [7]. The core objective of low-altitude grid construction is to enhance operational efficiency.

However, UAV operation in urban environments requires consideration of complex urban wind conditions. Instantaneous strong wind disturbances can cause UAV stall, yaw, or attitude loss. The core value of the low-altitude economy lies in leveraging UAVs to establish urban “air microcirculation,” enabling efficient coverage of high-frequency scenarios such as logistics delivery, emergency rescue, and air commuting—these scenarios demand far higher flight precision and stability than open-area applications. Insufficient aerodynamic stability directly leads to delivery deviations, mission interruptions, and even safety accidents like crashes causing casualties and property damage. Thus, conducting aerodynamic stability research to accurately match the aerodynamic response requirements of complex urban wind fields is a prerequisite for UAVs to meet urban scenario demands and achieve sustainable operations. The primary influencing factor of urban wind fields is obstacles of various forms, including low-rise building and high-rise building clusters, as well as building clusters with different configurations. High-rise buildings and low-rise buildings exert inconsistent effects on wind fields, and there are also significant differences in the patterns of flow separation and vortex shedding. These aspects have been fully studied in the field of wind engineering [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Therefore, it is essential to conduct in-depth research on the impacts of urban wind fields on the aerodynamic characteristics of UAVs.

In recent years, in line with the principle of “centering on operational scenarios and conducting hierarchical management based on operational risks,” the CAAC (Civil Aviation Administration of China) has steadily regulated UAV operations involving significant safety risks [14]. The implementation of policies such as wind resistance classification, flight zone delineation, and operational license approval all require aerodynamic stability data, serving as the core indicator for defining UAVs’ safe operation thresholds [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Establishing a standardized technical evaluation system through aerodynamic stability research not only provides a scientific basis for regulation but also guides enterprises to focus on core technological breakthroughs, lowers industry entry barriers, and accelerates the formation of a virtuous cycle of “technical compliance–scenario implementation–policy improvement,” laying the foundation for the low-altitude economy.

Currently, regarding the risk assessment of drones in urban scenarios, some scholars have proposed the impact of path occlusion effects on pedestrian safety [23]. However, for lightweight drones, the wind resistance is more critical to flight stability. In urban scenarios, the wind field structure is affected by building distribution, and local high-wind zones tend to form around high-rise buildings. For instance, the wind speed near air vents at the bottom of high-rises is approximately twice that of flat ground. Consequently, in studies focusing on the operational safety risk assessment of drones in urban contexts, the in-depth calculation and analysis of the wind field structure in their intended flight areas is necessary.

In this paper, by constructing urban scenarios and logistics drone models, CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) numerical simulations are carried out to compute the distribution characteristics of urban wind fields and the aerodynamic performance of the drone. Afterwards, with the limited wind speed of this specific model adopted as the incoming flow condition, the variations in aerodynamic forces and moments under various wind direction angles are calculated. Ultimately, based on the law governing the variation in aerodynamic characteristics with wind speed, the wind field safety along the drone’s travel route in urban scenarios is evaluated, and suggestions regarding the stable flight regions for drones are presented.

2. Near-Ground Wind Field Characteristics

2.1. Atmosphere Boundary Layer

When the wind blows across the Earth’s surface, the wind speed near the ground decreases due to the obstruction from various roughness elements on the ground, such as grasslands, crops, woodlands, and buildings. This effect weakens gradually as the height above the ground increases, and eventually disappears when a certain height is reached. The near-surface atmospheric layer affected by surface friction is generally referred to as the ABL (atmospheric boundary layer). As the main region where people conduct production and daily life, the wind field of the ABL constitutes one of the key research aspects of wind engineering.

In recent years, wind engineering has mainly focused on aspects such as the wind resistance of building structures, the dispersion of urban pollutants, and the impact of the outdoor wind environment on pedestrians. However, with the development of the low-altitude economy, aircraft activities have become frequent in the surface layer region. Taking logistics UAVs as an example, the selection of their operation routes considers not only efficiency but also the safety of the wind environment. In-depth research based on the UAVs’ own wind resistance and aerodynamic characteristics enables wind field assessment of the spatial areas along their operation routes, thereby enhancing the reliability and safety of urban transportation planning.

2.2. Urban Wind Field Characteristics

In modern society, changes in the local ABL caused by urbanization exert a significant impact on low-level air flow and atmospheric turbulence. The unique urban underlying surface with high roughness can generate intense mechanical turbulence, alter the local wind field structure, and thereby affect the daily lives of residents.

The complex internal structure of a city leads to local differences in the flow field. Certain areas become wind shadow zones with extremely low wind speeds. Conversely, under special circumstances, the local wind speed is significantly higher than that in rural areas at the same time and altitude.

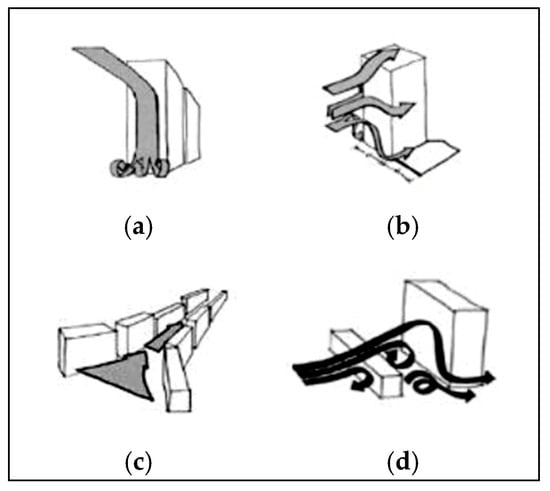

The impact of urban building clusters on the wind field is mainly reflected in the numerous irregular street canyons. Specifically, the layout of buildings mainly influences the flow field inside the street canyons. In addition, if the direction of the incoming flow is roughly consistent with the orientation of the street canyon, local strong wind zones will emerge inside the street canyon due to the Venturi effect. On the contrary, when the incoming flow is perpendicular to the axis of the street canyon, the relationship between the flow field inside the street canyon, its geometric characteristics, and the upstream incoming flow becomes highly complex, which generally forms a vortex structure within the street canyon. The different impacts of building arrangement patterns on the urban wind field are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Influence of the wind field surrounding the buildings: (a) downwash, (b) edge enhancement, (c) Venturi effect, and (d) building occlusion effect.

3. Models and Numerical Calculation Methods

To further verify the impact of urban wind field structures on the flight safety of UAVs, this paper established a typical urban building complex model and conducted CFD numerical simulations. The inflow velocity is set to U10 = 7.9 m/s according to the airworthiness limited wind speed [14]. The incoming flow adopted the C-type ground roughness wind speed profile defined by the “Load code for the design of building structures” [24]. Commonly used in wind engineering, the RANS SST k-ω model was selected as the turbulence model. Meanwhile, the UAV model chosen is the EHang logistics UAV. Through an investigation into the aerodynamic characteristics of rotor UAVs under heavy wind conditions, the laws governing the variation in aerodynamic stability of rotor UAVs are obtained.

3.1. Models

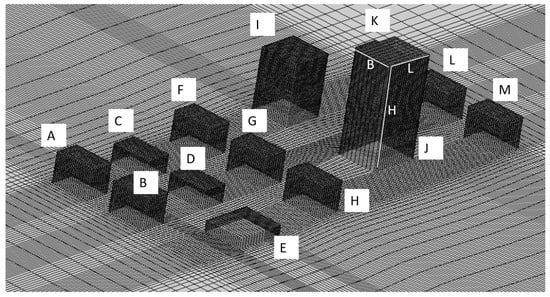

This paper focuses on the impact of the urban wind environment on the UAVs. Based on the typical distribution patterns of urban buildings, scene models were generated including 13 buildings arranged in 4 rows along the incoming flow direction. The building layout and grid are illustrated in Figure 2. A structured mesh was adopted with a grid number of about 2 million, and the detailed parameters of the buildings are presented in Table 1. Buildings A, B, C, D, F, G, H, K, L, and M are designed as low-rise residential structures, whereas Building E is designated as a public building space, and Buildings I and K are planned to serve as high-rise office complexes or residential developments. The flow separation and vortex shedding around high-rise and low-rise buildings exhibit distinct behaviors. Consequently, during the scenario design of this research, comprehensive consideration must be afforded to buildings with multiple height, ranging from 10 m to 100 m.

Figure 2.

Urban architectural scene model grid.

Table 1.

Dimensions of Buildings.

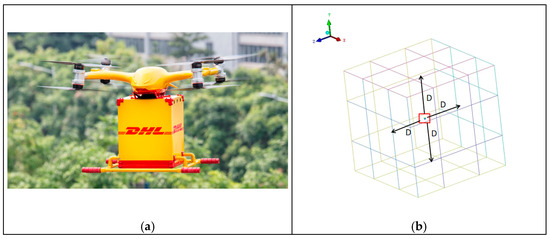

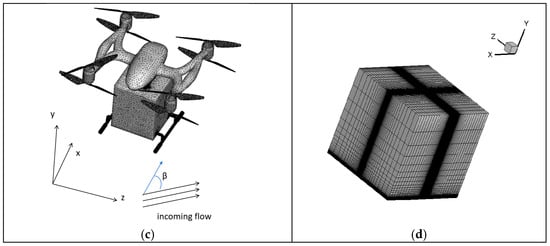

The resistance wind speed of the UAV is measured at 10 m above the ground surface. As a general rule, the aerodynamic impact induced by wind intensifies with increasing flight altitude. In this paper, the Falcon logistics UAV was selected as the research model, which was the custom-developed by EHang (the company located in Guangzhou, China) for Deutsche Post DHL. Through analysis of its aerodynamic characteristics under high-wind conditions, this work aims to provide a theoretical and data-driven basis for wind field assessment in logistics route planning. The physical prototype of the UAV and its model mesh are illustrated in Figure 3. An unstructured mesh was adopted for numerical simulation, with a grid number of about 5 million. Detailed dimensional parameters of each component are tabulated in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Real UAV figure and computational model grid: (a) Falcon UAV, (b) computational domain of the UAV model with D = 40 m (the center red box is the UAV model put in the computational domain), (c) surface grid of the UAV model, and (d) whole grid of the UAV model.

Table 2.

Dimensions of UAV model.

3.2. Numerical Calculation Methods

Urban scenario-based numerical simulation belongs to the research scope of bluff body flow simulation. The governing equations are the viscous incompressible Navier–Stokes equations. Theoretically, the most robust numerical prediction methods are DNS (Direct Numerical Simulation) and LES (Large Eddy Simulation). However, limited by the constraints of computer memory and computational performance, their application in real-world engineering contexts remains demanding to date. Currently, the most prevalent numerical simulation methodology is founded on the RANS (Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes) equations, which require turbulence models for closure and are solved by means of discretization [25].

In this study, the SST k-ω turbulence model is selected which is commonly utilized for numerical simulations of flow fields within the atmospheric boundary layer. According to previous research, it is known that the SST k-ω turbulence model can achieve good fitting performance for both building flow around bluff bodies and airfoil aerodynamic characteristics [9,26]. The commercial software ANSYS FLUENT 21.0 is employed for the numerical computation of urban wind fields and UAV aerodynamics. The solver uses pressure–velocity coupling with the SIMPLEC algorithm. And the spatial gradient discretization method is selected as Least Squares Cell-Based, while the second-order upwind scheme is adopted.

In the calculation of the urban wind field, the incoming wind speed profile and turbulence intensity are defined by the “Load code for the design of building structures” [24], and the specific formulas are as follows:

where the constant Cμ is 0.09, L is the characteristic length, the turbulence integral length lt is 0.07 L, Iu is the turbulence intensity, I10 is the nominal turbulence intensity at 10 m, U10 is the mean velocity at 10 m, z0 is the height above the ground, and the wind velocity components in the x, y, z directions are u, v, w. The expressions of Iu and u complied with the definition in the building load code and I10 was 0.23. The incoming flow u, turbulent kinetic energy k, and specific dissipation rate ω are implemented via a UDF (User-Defined Function).

Considering the relatively small size, the UAV model is influenced less by the gradient wind. When investigating the variation patterns of its aerodynamic characteristics, it can be treated as a uniform incoming flow. First, based on the weight of the logistics UAV (Wfuselage + Wcargo = 30 kg), the rotational speed in the vertical balance condition under windless environments is determined to be 2000 r/min. This rotational speed provides the minimum lift to ensure flight stability, and the aerodynamic characteristics under all subsequent operating conditions are referenced to this vertical balance condition. The main aerodynamic forces and moments are defined such that CL is the force vertical to the wing surface, CD is the force preventing its progress in the opposite direction to the flight direction, CX is the lateral force perpendicular to the plane of symmetry of the aircraft, Cmx is the rolling moment along the longitudinal axis (x-axis), Cmy is the pitching moment along the horizontal axis (y-axis), and Cmz is the yawing moment along the vertical axis (z-axis).

The aerodynamic force and moment coefficients are defined as follows:

(a) Vertical force coefficient

(b) Lateral force coefficient

(c) Rolling moment coefficient

(d) Pitch moment coefficient

(e) Yaw moment coefficient

where ρ is the air density, V∞ is the incoming velocity, S is the wing reference area, cA is the MAC (Mean Aerodynamic Chord), Fz is the vertical force, Fy is the lateral force, Mx is the rolling moment, My is the pitch moment, and Mz is the yaw moment.

3.3. Grid Independence Verification

Grid Independence Verification is a critical step in numerical simulations, aiming to ensure the reliability and accuracy of computational results. Its necessity mainly stems from the inherent limitations of numerical methods and the practical requirements of engineering applications.

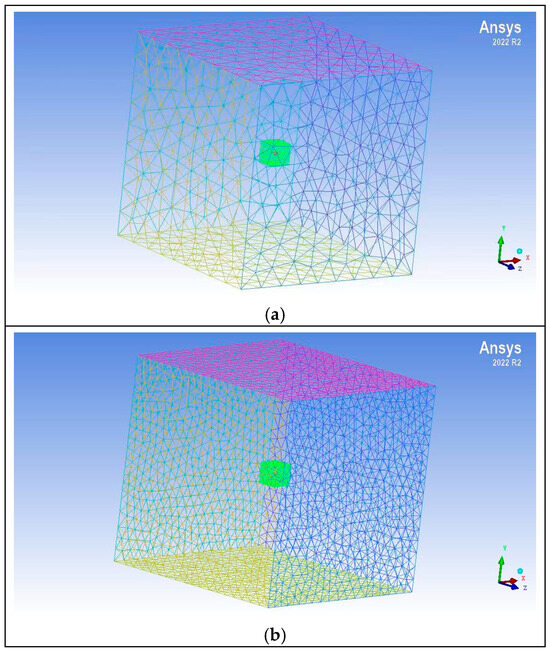

In this paper, there are three sets of grids with different densities in this study with a grid number of about 1, 5, and 10 million, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Three sets of grids: (a) 1 million, (b) 5 million, and (c) 10 million.

The results in Table 3 show that the CL and CD exhibit a progressively convergent trend with grid refinement over the 5 million grid number. Therefore, in the subsequent calculations, the UAV model with a grid count of 5 million is adopted.

Table 3.

Grid Independence Verification results, U∞ = 18 m/s.

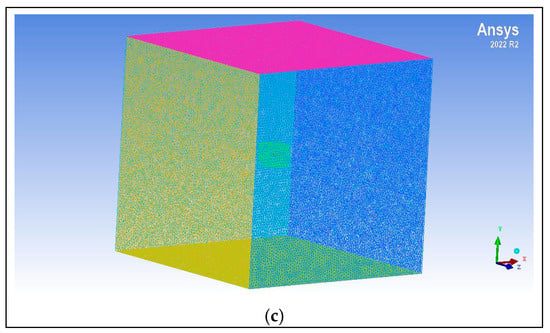

4. Effects of Wind Speeds and Directions on the Aerodynamic Characteristics of Rotor UAVs

According to the definition of the vertical balance condition, the total thrust balances the total weight. Calculations show that the UAV can achieve the vertical balance condition at a rotational speed of 2000 r/min. As indicated by the UAV flight stability status, it is most susceptible to wind effects in the vertical balance condition. Therefore, the aerodynamic characteristics of the vertical balance condition should be investigated first, as shown in Table 4. Then, the ratios of aerodynamic forces and moments under different wind conditions are calculated. Figure 5 shows the fuselage pressure distribution in the vertical balance condition.

Table 4.

Aerodynamic forces and moments of the UAV model when in vertical balance.

Figure 5.

Fuselage pressure distribution of the UAV model when in vertical balance.

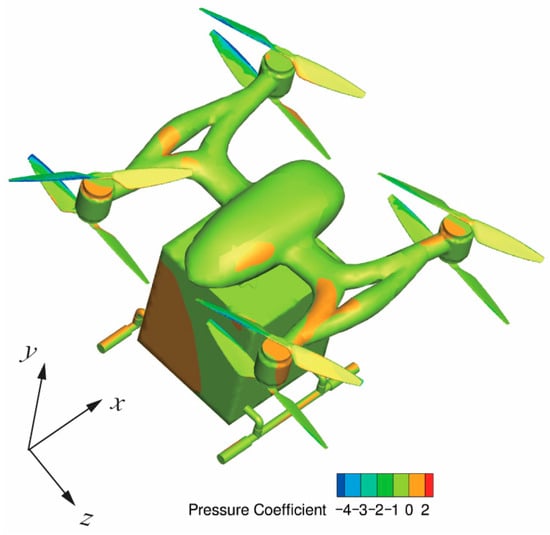

4.1. Effect of Wind Sideslip Angle on the Aerodynamic Characteristics of Rotor UAVs

According to the product manual, the limited wind speed of the UAV is 18 m/s. Therefore, a uniform incoming flow with U∞ = 18 m/s is selected for numerical simulation with sideslip angles ranging β from 0° to 180°.

The research on the influence of aerodynamic stability on UAVs in the vertical balance condition mainly focuses on the variation law of aerodynamic moments [10,11,12]. As shown in Figure 6, the yawing moment increases firstly and then decreases with the wind sideslip angle, with the ratio peak value of 2.16 appearing around β = 60°. The rolling moment increases initially with the wind sideslip angle and then remains stable, and the ratio of the rolling moment in the stable segment to the reference value is approximately 1.3. The pitching moment increases with the wind sideslip angle, reaching the ratio peak value of 1.73 at around β = 150°.

Figure 6.

Variation in aerodynamic moments of UAV model with different wind sideslip angles.

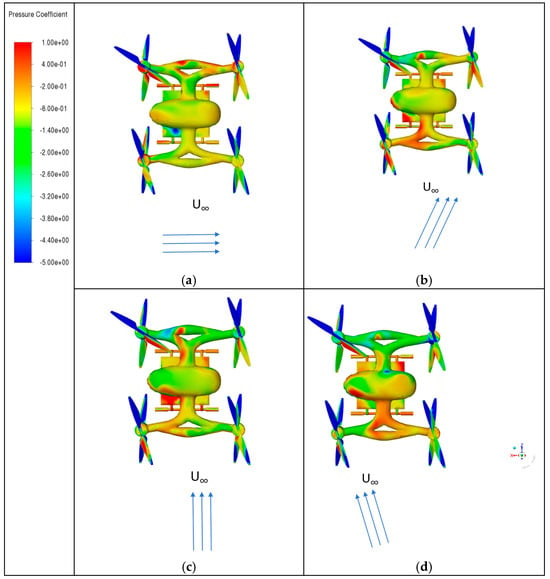

As illustrated in Figure 7, the pressure coefficient of the upper fuselage surface can reflect the stress change under different sideslip angles (the arrows refered to the incoming flow direction). It can be seen that the surface pressure becomes uneven compared with β = 0° as the wind direction angle increases. As Figure 7d shows, when β = 150°, the pressure coefficient is larger than that of the small sideslip angle. And the front of the fuselage exhibits negative pressure, while the rear of the fuselage exhibits positive pressure, resulting in nose-up pitching moment. Meanwhile, the right frame part shows the negative pressure and the left frame part shows the positive pressure with β = 150°. Therefore, the UAV model generates the rolling moment along the positive y-axis direction.

Figure 7.

Upper fuselage surface pressure coefficient of the UAV model with U∞ = 18 m/s: (a) β = 30°, (b) β = 60°, (c) β = 90°, and (d) β = 150°.

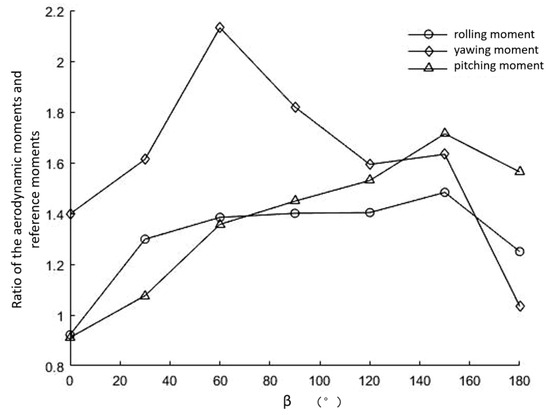

4.2. Effect of Wind Speed on the Aerodynamic Characteristics of Rotor UAVs

To analyse the influence of the wind speed on the UAV’s aerodynamics, the direct crosswind β = 90° is chosen to reflect a relatively high stability risk. Under this angle, numerical calculations of the UAV’s aerodynamic characteristics are performed with the incoming flow velocity ranging from 6 m/s to 18 m/s.

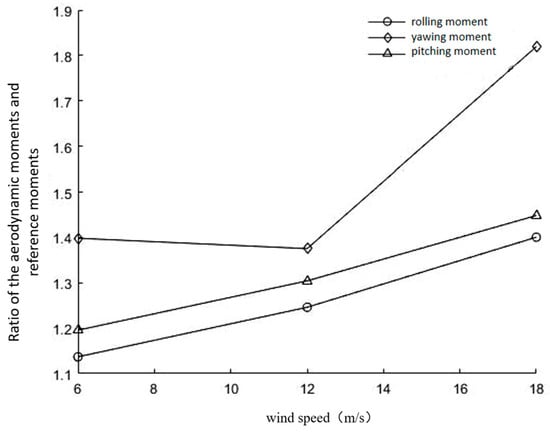

As illustrated in Figure 8, the yawing moment decreases slightly first and then increases rapidly, while the rolling moment and pitching moment increase with the rise of wind speed. The variation trends of the three aerodynamic moments with the large incoming flow velocity are basically consistent, which shows that their values all increase with wind speed. And the growth rate of the yawing moment becomes significantly higher than that of the other two moments when the wind speed exceeds 12 m/s. The conclusions of this section will provide a calculation basis for subsequent wind field assessments.

Figure 8.

Variation in aerodynamic moments of UAV model with wind speed 6~18 m/s when β = 90°.

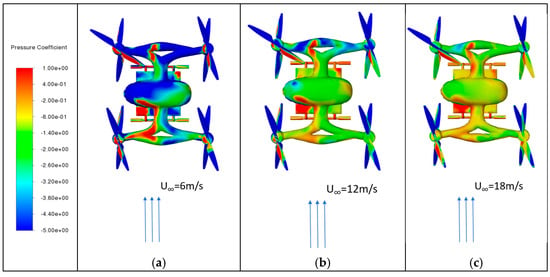

As can be seen from Figure 9, the pressure of the upper fuselage changes from negative to positive and the nose-up pitching moment is formed (the arrows refered to the incoming flow direction). With larger wind speed, the pressure difference between the left and right frames of the UAV increases, which means the rolling moment increases accordingly. At the same time, the positive pressure on the windward side of the UAV’s blades increases, resulting in a significant yawing moment.

Figure 9.

Upper fuselage surface pressure coefficient of the UAV model when β = 90°: (a) U∞ = 6 m/s, (b) U∞ = 12 m/s, and (c) U∞ = 18 m/s.

5. Wind Field Assessment of UAV Flight Space in Urban Scenarios

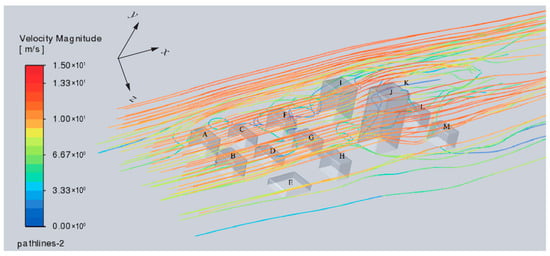

Research on urban building wind fields can provide a basis for detailed spatial wind environment conditions for the planning of UAV flight paths. Using the method and turbulence model mentioned in Section 3, when the incoming flow is U10 = 7.9 m/s, the streamlines diagram of the urban wind field model is illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Streamlines of urban architectural scene model with U10 = 7.9 m/s.

Through the simulation of urban building scenarios, the wind field distribution in urban environments at different altitudes can be obtained. According to the different missions of logistics UAVs, three typical heights above the ground are selected, as 10 m, 25 m, and 50 m, which represent near-ground navigation, flight above multistoried buildings, and cruising across high-rise buildings, respectively. By investigating the wind field characteristics at different altitude levels, the aerodynamic stability of UAV travel routes can be qualitatively evaluated.

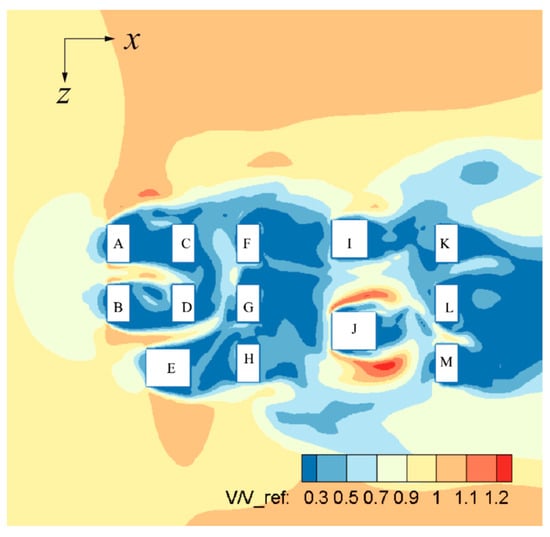

Figure 11 presents the calculation results of the flow field at a ground height of 10 m. V is the wind speed at a certain point in this altitude layer and V_ref is the incoming flow speed at this altitude. The wind speed ratio can be defined as V/V_ref, which can directly obtain the acceleration and deceleration area. It can be seen that the large wind speed areas are generated on both sides of the relatively tall Building J, with a maximum wind speed ratio of 1.25. A slight increment is also observed between Buildings A and B, as well as between Buildings B and E, with a maximum wind speed ratio of 1.08. Meanwhile, the leeward sides of the buildings are negative pressure zones, where the flow is relatively complex and weak, with an average wind speed ratio of approximately 0.4.

Figure 11.

Computational result of wind speed ratio at height of 10 m, U10 = 7.9 m/s.

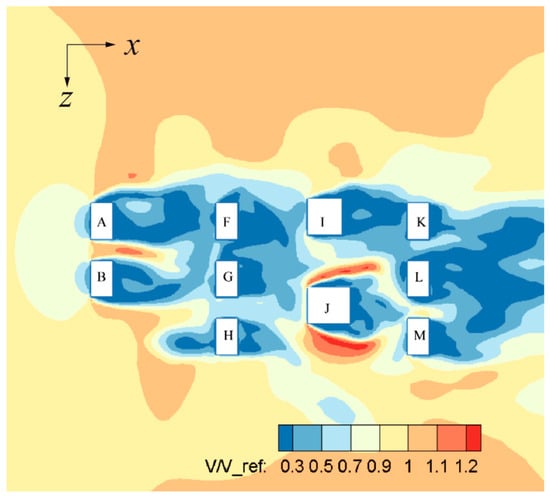

Figure 12 shows the calculation results of the flow field at a ground height of 25 m. It can be observed that with increasing height, the impact of low-rise buildings on the wind field weakens, and the overall wind speed distribution exhibits little change. However, the wind speed acceleration effects are enhanced on both sides of Building J as well as the channel between Buildings A and B, with an increase in wind speed acceleration areas. The flow velocities in the leeward regions of the buildings are higher than those at a height of 10 m.

Figure 12.

Computational result of wind speed ratio at height of 25 m, U10 = 7.9 m/s.

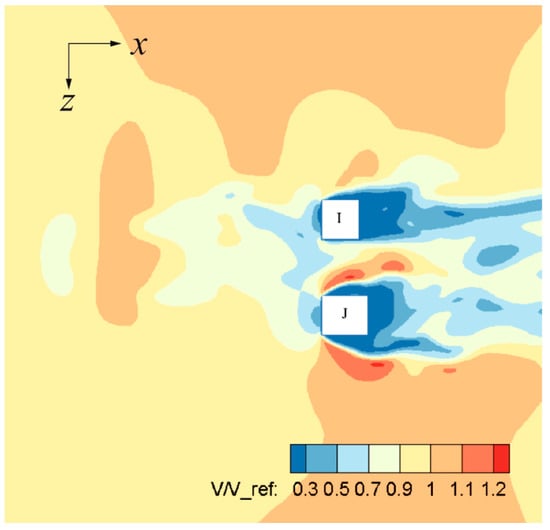

Figure 13 shows the result of the flow field at a height of 50 m. At this altitude, the flight path is less affected by buildings. Since the impact of low-rise buildings on the wind field weakens, the average wind speed across the entire area increases. The area of the wind speed acceleration zone on both sides of Building J remains essentially unchanged, while the area where the wind speed ratio exceeds 1.2 is relatively smaller compared to that at 25 m.

Figure 13.

Computational result of wind speed ratio at height of 50 m, U10 = 7.9 m/s.

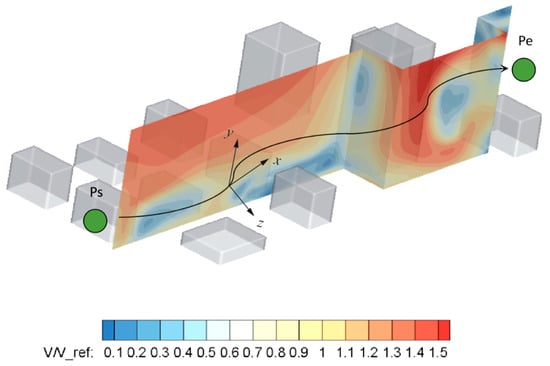

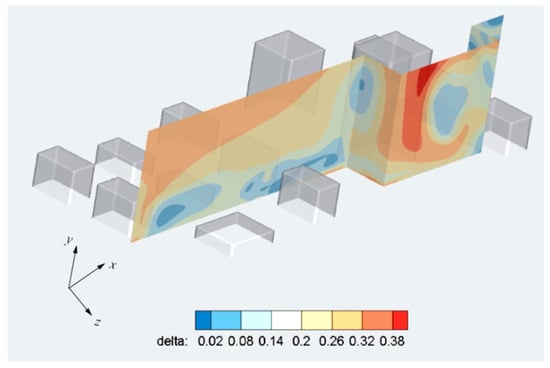

After a preliminary study on the urban wind field structure at different altitude levels, the UAV flight operation is intended to be carried out from point Ps to point Pe. The travel route selected in this paper is illustrated in Figure 14, and wind field cross-sections are extracted along the height above the ground to obtain the wind field distribution counter of the vertical plane along the flight route.

Figure 14.

Wind field distribution of UAV flight path with H from 0 to 100 m, U10 = 7.9 m/s.

Based on the wind field results along the UAV’s flight path, a comprehensive assessment can be conducted according to different wind field safety impact factors, obtaining the spatial wind field safety level results of this UAV model. This paper proposes a calculation method for the operational UAV wind field safety level δ, which is the product of three impact factors: the meteorological factor δ1, the wind direction factor δ2, and the aerodynamic factor δ3. The meteorological factor is the ratio of the wind speed at a specific point to the maximum operational wind speed of the UAV. The wind direction factor is the ratio of the aerodynamic moment corresponding to the wind direction angle at a specific point to the maximum aerodynamic moment of the UAV model, as illustrated in Figure 6. The aerodynamic factor is the ratio of the aerodynamic moment corresponding to the wind speed at a specific point to the aerodynamic moment at the UAV’s resistance wind speed, as shown in Figure 8. Finally, the value range of the safety level δ is divided to define different risk levels, which are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Evaluation factors for wind field safety level of UAV flight stability.

Based on the safety level calculation method, a safety assessment is conducted on the wind field along the UAV flight path illustrated in Figure 14, resulting in the safety risk contour map shown in Figure 15. The safety level distribution presented in Figure 15 can provide a reference for planning the flight altitude of logistics UAVs.

Figure 15.

Wind field safety level of UAV flight path with H from 0 to 100 m, U10 = 7.9 m/s.

6. Conclusions

This paper conducts research on the influence of urban wind field structures on UAV flight stability and proposes a safety level assessment method for urban wind fields in UAV flight airspace. First, the study of the aerodynamic characteristics of rotor UAVs with sideslip angles and wind speeds is simulated. It is found that a sideslip angle of 60° corresponds to the peak yawing moment of the UAV model. However, the combined moment reaches its maximum at a 150° sideslip angle.

Then, through the research on urban wind field structures, a qualitative analysis of different wind field-affected areas is performed. Under heavy wind conditions, the large wind speed acceleration zones emerge on either side of the high-rise building, and the acceleration area reaches its maximum at 25 m above ground.

Combined with the variation laws of aerodynamic characteristics of UAVs, the wind field safety level is calculated. Finally, multi-dimensional evaluation factors can effectively characterize the safety level of the vertical wind field on the UAV’s flight route. The wind field safety level distribution in the flight path can ultimately guide the urban flight path planning of UAVs and improves flight stability.

The limitations of this study’s text mainly include the following two aspects. First, there are various methods for generating urban wind field environments, such as flow around buildings of different heights, street canyon wind effects, thermal circulation effects, and the accuracy of ground roughness selection in the calculation cases caused by different underlying surfaces. Second, the physical model adopted is singular. Currently, there are a wide variety of UAV types available on the market. The UAV risk factor δ proposed in this paper is more suitable for small and light UAVs, which have short fuselage frames and small moment arms. In contrast, for UAVs with large aspect ratios, their force-bearing conditions are more complex. In the future, it is necessary to conduct research on different UAV models and ultimately establish a target database, which provides a data basis for planning flight routes for different models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W. and J.L.; methodology, J.L.; software, J.L. and Y.L.; validation, J.L., H.Y., and Q.Q.; formal analysis, J.L.; investigation, J.L. and Y.L.; resources, J.L. and Q.Q.; data curation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.W.; visualization, Q.Q.; supervision, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds of CASTC (funding number is x242060302237) “Research on the Influence of Low Altitude Complex Wind Environment on the Stability of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All authors of articles are willing to share our research data. Please email the corresponding author to obtain detailed data information.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all authors for their helpful discussions and collaborative efforts in numerical simulations. And Jianghao Wu, with profound knowledge in aerodynamic stability and rigorous academic attitude, has been a constant inspiration to us. Additionally, we thank the editors and reviewers for their careful review and valuable comments that enhanced the clarity and completeness of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UAVs | Unmanned Aerial Vehicles |

| UAM | Urban Air Mobility |

| CAAC | Civil Aviation Administration of China |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| ABL | Atmospheric Boundary Layer |

References

- Tang, J. Can low altitude economy development bring economic and environmental dividends?--evidence from Chinese cities. J. AIR Transp. Manag. 2025, 131, 102919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ran, D.X. China’s low-altitude economy needs to grow with more caution. Nature 2025, 638, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Zhu, F.; Tu, W.; Zhu, H.; Qin, D.; Wang, H.; Zhai, Z. Urban air mobility in the built environment: A review of aerodynamic interactions, thermal effects, and simulation challenges. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 133, 106853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zhu, F.; Tu, W.; Zhu, H.; Qin, D.; Wang, H.; Zhai, Z. Study on the evaluation method of pilot workload in eVTOL aircraft operation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Dai, F. Risk assessment model for UAV operation considering safety of ground pedestrians in urban areas. China Saf. Sci. J. 2020, 30, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Chen, G.; Mao, Y. Study of wind environment around building complex based on CFD. J. Zhejiang Univ. Technol. 2007, 35, 351. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Tian, T.; Feng, O.; Wu, S.; Zhong, G. Research on Public Air Route Network Planning of Urban Low-Altitude Logistics Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Shi, L.; Zhang, D.; Jiao, N. Numerical Simulation of Wind Environment around Complex Building. J. Shenyang Jianzhu Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2011, 4, 731–736. [Google Scholar]

- Behrouzi, F.; Sidik, N.; Malik, A.; Nakisa, M. Prediction of Wind Flow Around High-Rise Buildings Using RANS Models. World Virtual Conf. Adv. Res. Mech. Mater. Eng. 2014, 554, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, E.; Xiang, Q.; Chan, J.; Dong, Y.; Tu, S.; Chan, P.; Ni, Y. Increasing temporal stability of global tropical cyclone precipitation. Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, E.; Dong, Y.; Yue, H.; Ni, Y. Reflections on potential applications of LiDAR for in-situ observations of high-rise buildings during typhoons: Focusing on wind-driven rain and windborne debris. Adv. Wind. Eng. 2024, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, X.-Y.; Deng, E.; Ni, Y.-Q.; Chan, P.-W.; Yang, W.-C.; Tan, Y.-K. Acceleration and Reynolds effects of crosswind flow fields in gorge terrains. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 085143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, R.; Feng, L.; Wu, Y.; Niu, J.; Gao, N. Boundary layer wind tunnel tests of outdoor airflow field around urban buildings: A review of methods and status. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MH/T 6126-2022; Technical Requirements of Multi-Rotor Electric Unmanned Aircraft System (Small and Light) for Urban Logistics. Civil Aviation Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Liu, C.; Wei, Z.; Han, H.; Shan, Z. Aerodynamic response analysis of unmanned aerial vehicle rotor vertical balance under crosswind influence. China Saf. Sci. J. 2021, 31, 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, C.; Suárez, E.; Gil, C.; Baker, C.; Vence, J. Assessment of the methodology for the CFD simulation of the flight of a quadcopter UAV. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2021, 218, 104776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, C.; Suarez, E.; Gil, C.; Baker, C. CFD analysis of the aerodynamic effects on the stability of the flight of a quadcopter UAV in the proximity of walls and ground. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2020, 206, 104378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Wu, H.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Z. Computational Research on Aerodynamic and Noise Characteristics of Variable Pitch Quad rotor Aircraft. Aeronaut. Sci. Technol. 2022, 33, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Le, S.; Zhou, J. Vertical balance aerodynamic performance analysis and experiment of variable pitch rotor UAV. Aeronaut. Sci. Technol. 2014, 25, 104–108. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.; Lin, Y.F.; Chen, J.H. Analysis Simulation of Urban Building Flow-field based on the Safety Conditions of Helicopter Taking Off and Landing. Helicopter Tech. 2017, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sarikaya, B.; Zarri, A.; Christophe, J.; Aissa, M.H.; Verstraete, T.; Schram, C. Aerodynamic and aeroacoustic design optimization of UAVs using a surrogate model. J. Sound Vib. 2024, 589, 118539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marqués, P.; Ronch, A.D. Advanced UAV Aerodynamics, Flight Stability and Control: Novel Concepts, Theory and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, R.; Zhao, Y.; Ren, X. Integrating wind field analysis in UAV path planning: Enhancing safety and energy efficiency for urban logistics. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 39, 103605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB50009-2012; Load Code for the Design of Building Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Liu, P. Turbulent Model Theory; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhdhar, L.; Bouabidi, A.; Snoussi, A. Impact of blade number on the aerodynamic performance of UAV propellers: A numerical and experimental study. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 166, 110594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.