1. Introduction

Soil is a complex ecosystem composed of inorganic and organic matter, water, air, and a diverse community of living organisms including fungi, algae, and bacteria. Soil microorganisms play fundamental roles in nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, and mineral regeneration, while also contributing to pesticide degradation and promoting plant productivity [

1,

2,

3].

The composition, structure, and activity of the soil microbiome are strongly influenced by both biotic factors, such as animals, plants, and microorganisms, and abiotic factors, including organic and inorganic compounds, salinity, drought, temperature, and pH. These environmental variables play a crucial role in determining soil fertility and crop performance [

1,

4].

Within the soil microbial community, bacteria are predominant relative to other microbial groups. Notably, plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) constitute a beneficial subgroup inhabiting the soil, rhizosphere, roots, and other plant tissues [

5]. PGPB enhance plant growth and stress resilience through multiple mechanisms, including phosphate solubilization, nitrogen fixation, siderophore production, synthesis of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), and modulation of ethylene levels via ACC deaminase activity [

2,

6,

7]. Their capacity to sustain plant growth under suboptimal conditions makes them a promising sustainable alternative to traditional chemical agricultural inputs [

1,

3].

The integration of PGPB into agricultural management strategies represents a key approach to mitigate the environmental impact of conventional fertilization under ongoing climate scenarios. The European Green Deal and the Farm to Fork strategy have emphasized the need to reduce the dependency on chemical fertilizers and pesticides by enhancing the ecological services provided by soil microorganisms [

5,

6]. PGPB contribute to this transition through nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration, and the stabilization of soil microbial networks [

8].

However, these plant growth-promoting processes are highly sensitive to environmental parameters, which influence enzyme functionality, membrane fluidity, and the availability of key nutrients in soil [

9]. Additionally, the physiological state of the bacterial biomass at inoculation could play a crucial role in determining the subsequent colonization success and stress tolerance of PGPB formulations [

10].

Among abiotic variables, temperature and pH are particularly significant in regulating microbial growth and function. Bacteria inhabiting environments with different temperature regimes often exhibit a wide range of cardinal growth temperatures (minimum, optimum, and maximum) [

11], but temperature exerts a selective pressure on bacterial communities; larger temperature shifts correspond to stronger selection and enhanced community adaptation [

11,

12].

Additionally, soil pH influences bacterial function since most bacteria prefer near-neutral conditions, as extreme pH alters the structure of proteins and enzymes, impairing bacterial activity and, consequently, soil quality and plant growth [

1,

11,

13].

Despite extensive studies on microbial responses to climate change, the specific responses of key soil bacterial groups to simultaneous shifts in temperature and pH remain insufficiently understood. To harness PGPB as effective biofertilizers, it is essential to evaluate how these factors influence their growth and activity. While it is well known that the production of biomass from bacteria is a critical step and could strongly influence their performance, to the authors’ knowledge, there are no details on this topic regarding PGPB.

While numerous studies have characterized the plant growth-promoting traits of soil bacteria, the technological aspects of PGPB biomass production remain poorly documented. Specifically, the influence of preculture conditions, particularly culture age age, on the subsequent stress tolerance and colonization capacity of PGPB formulations represents a critical knowledge gap, alone or in interaction with some operational variables, like pH and temperature. Understanding how production parameters affect inoculum quality is essential for developing reproducible, industrially scalable biofertilizer products, yet this perspective is rarely integrated into PGPB research.

In the present study, two phylogenetically distinct PGPB strains were selected based on their isolation source and previously demonstrated plant growth-promoting traits.

Bacillus sp. 36 M and

Stenotrophomonas sp. 20P were isolated from the durum wheat rhizosphere in the Mediterranean region [

14], representing two taxonomically different bacterial groups with complementary functional characteristics.

Bacillus and related spore-forming genera are well known for their adaptability, phosphate solubilization, and production of multiple plant growth regulators, making them robust candidates for biofertilizer formulations.

Stenotrophomonas species, conversely, exhibit wide ecological adaptability, stress tolerance, and nutrient cycling capabilities. This strain selection allowed a comparative assessment of how taxonomically distinct PGPB respond to identical production conditions, providing insights relevant to multi-strain biofertilizer development.

Both strains were previously characterized for their plant growth-promoting capabilities [

14];

Bacillus sp. 36 M demonstrated nitrogen fixation potential, phosphate solubilization activity, phosphate mineralization, and low level of indole–3–acetic acid (IAA) production, while

Stenotrophomonas sp. 20P exhibited higher nitrification capacity, siderophore production, and ammonium production. These functional traits contribute to nutrient availability and plant stress mitigation, making both strains promising candidates for biofertilizer development under Mediterranean agricultural conditions.

The main goal of this paper was to study the effects of some operational variables, like culture age at the time of inoculation, and some soil factors, like pH and temperature.

A factorial experimental design was applied to quantitatively assess the main effects and interactions among these variables, as well as correlations between these factors and bacterial viability. Data were analyzed using Multifactorial Analysis of Variance (MANOVA), providing a comprehensive understanding of the relationships and potential interactions among the studied variables. Thus, the main goal was to generate practical knowledge to support the optimization of PGPB-based biofertilizer formulations. Understanding how inoculum physiological state and environmental conditions interact can guide the selection of resilient strains and improve consistency between laboratory efficiency and field performance.

3. Results

The initial statistical assessment was performed using multifactorial ANOVA to evaluate the significance of the tested independent variables (experimental design combination, culture age, and sampling time) on the dependent variable, which was the increase in cellular concentration normalized relative to the initial inoculum (t0); raw data are given in

Supplementary Table S1. The significance of each predictor was assessed with an F-test (F), representing the ratio of variance explained by the predictor to the unexplained variance. For strain 36 M, the table of standardized effects indicated that all predictors were statistically significant, with the highest effect observed for “culture age” (F-test, 509.76), followed by “sampling time” (F-test, 435.38) and the interaction “combination of the design” vs. “sampling time” (F-test, 216.21). However, the table of standardized effects provides qualitative insights, but does not offer quantitative trends, which could be obtained by the decomposition of the statistical hypotheses.

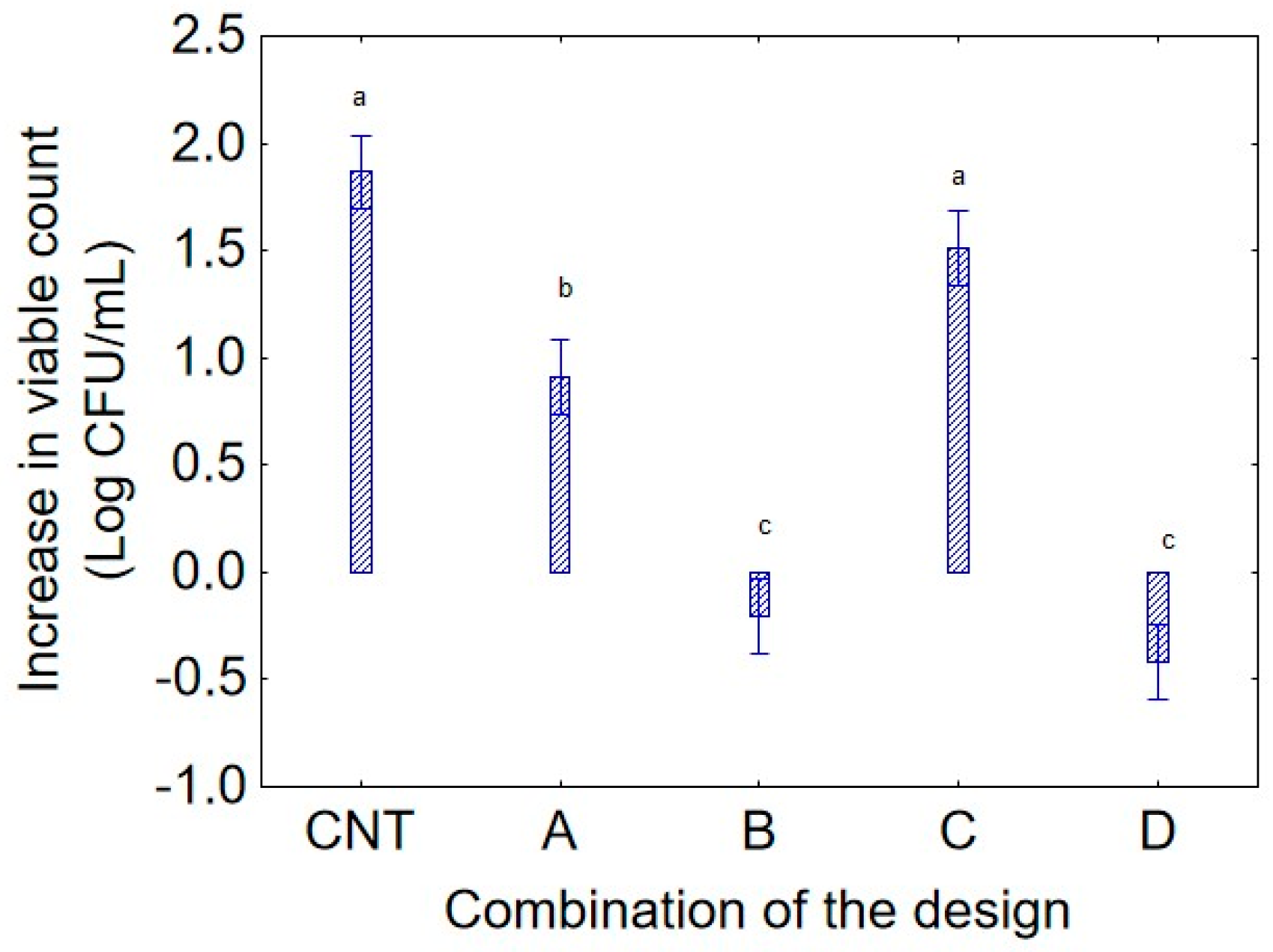

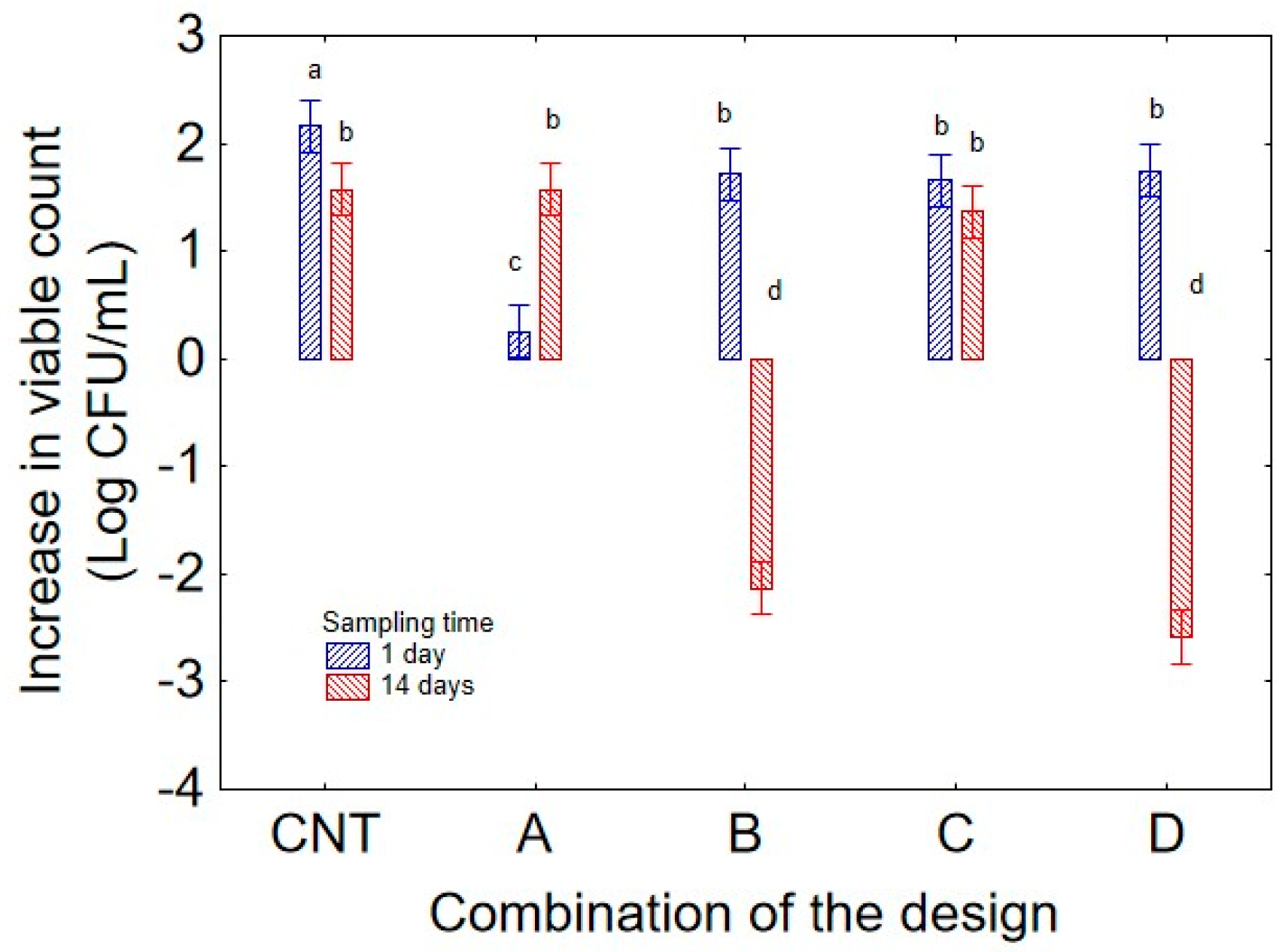

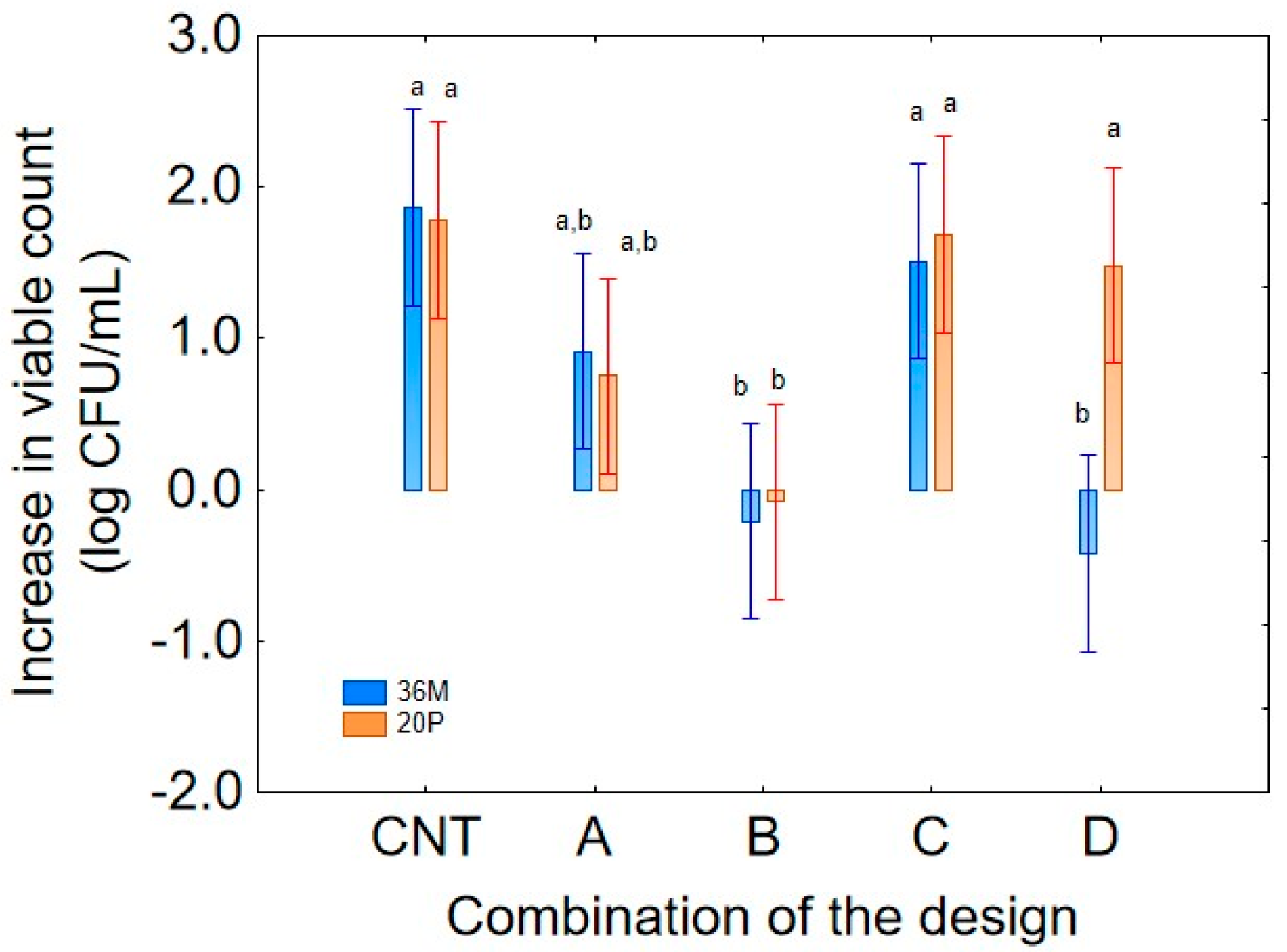

Figure 1 shows the effect of the predictor “combination of the design” on the increase in the viable count of strain 36M. Combination C (pH 7.5; temperature 15 °C) exhibited a similar contribution to the control (CNT), with an increase in cellular concentration of 1.75 Log CFU/mL. Conversely, combinations B (pH 5; temperature 35 °C) and D (pH 7.5; temperature 35 °C) negatively affected bacterial growth, resulting in a decrease in cellular concentration of 0.3–0.5 log CFU/mL. Finally, also in combination A (pH 5.0, and 15 °C), the strain 36M exhibited a general increase in the viable count with a mean increase of 0.8 log CFU/mL. It is worth mentioning that the decomposition of the statistical hypothesis does not show actual values but the mean contribution of each variable, in this case, the predictor “combination of the design”, independently of culture age (24 or 72 h) and sampling time (1 or 14 days).

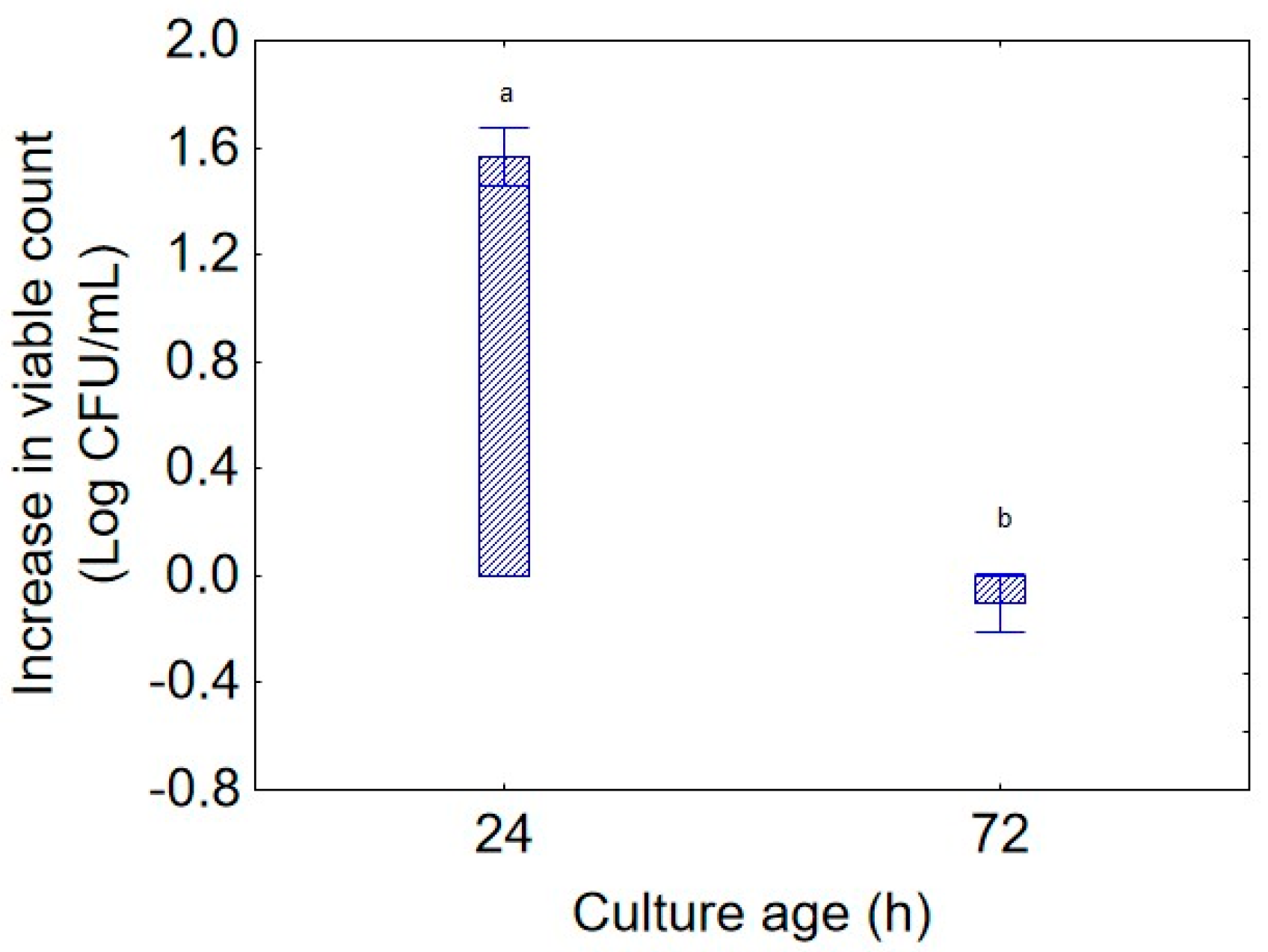

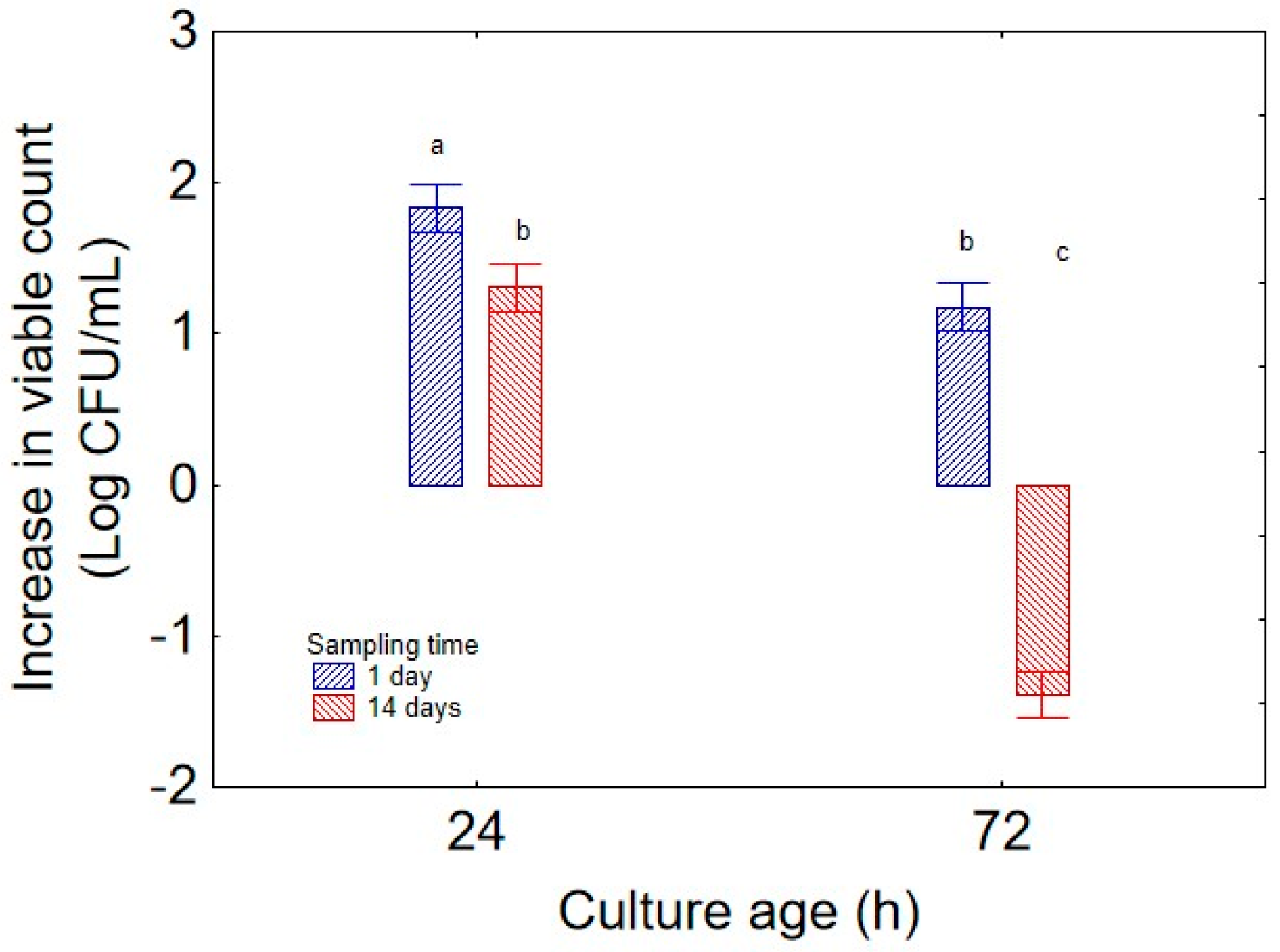

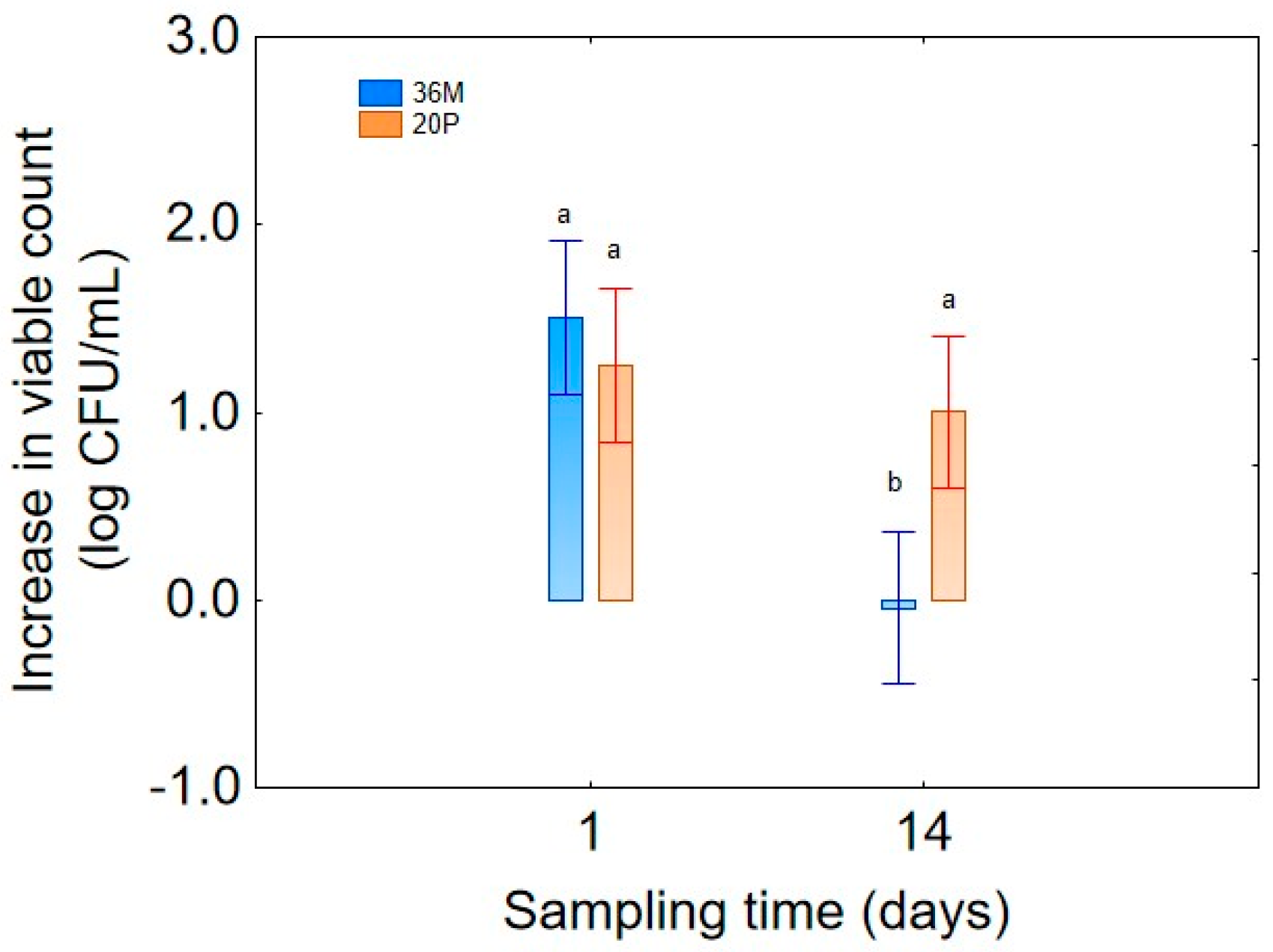

The second predictor of the Design of Experiments was “culture age”, whose impact is shown in

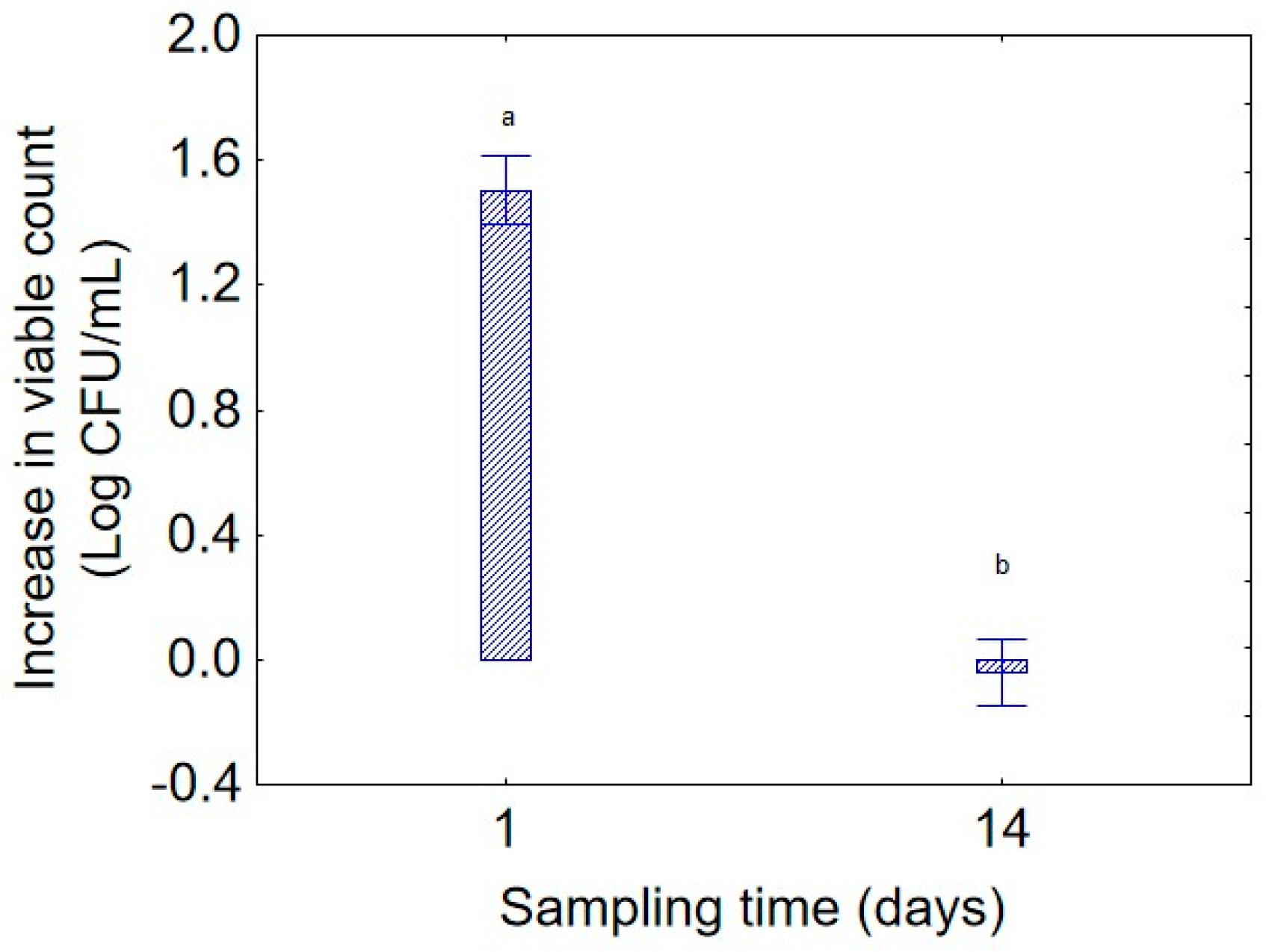

Figure 2. As expected, the highest increase in bacterial concentration was observed with a 24 h preculture (1.5 log CFU/mL) while the contribution of a biomass of 72 h to the increase in viable count was near 0.0 log CFU/mL; this result is an extrapolation of biomass weight on the total experimental variance and does not consider the other variables, but it suggests that the microorganism was more vigorous when inoculated from a younger culture. Regarding “sampling time” (

Figure 3), the microorganism demonstrated maximal growth at day 1 (1.5 log CFU/mL), followed by a clear decline after 14 days, confirming the typical kinetics of microbial decline following the growth phase, a possible growth phase of the strain 36M after 1 day, and a death phase after 2 weeks.

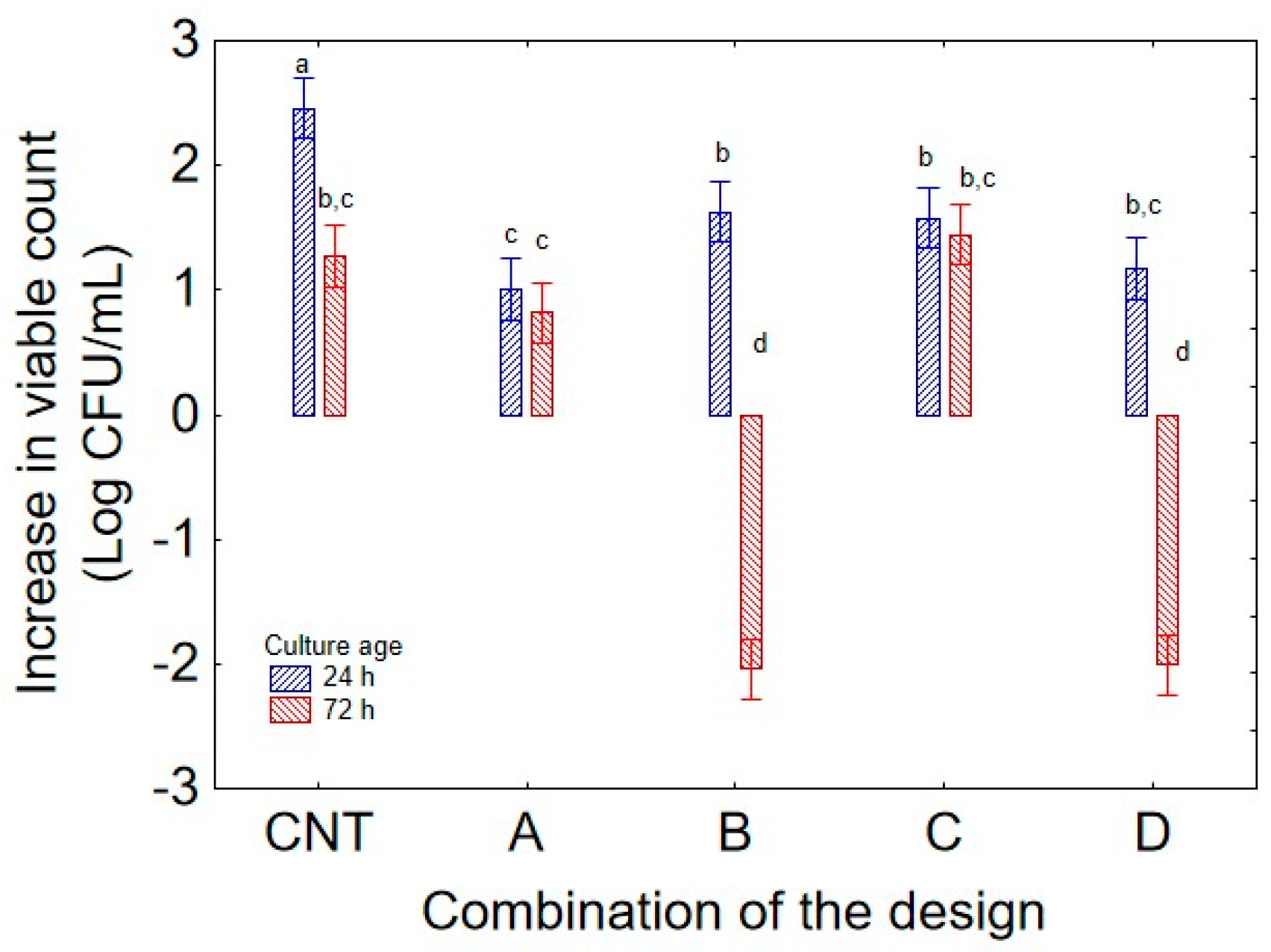

While the decomposition of the statistical hypothesis for the individual terms clearly points out the contribution of each predictor, it does not consider the effect of interactions occurring on microbial growth, and the fact that the quantitative contribution of each variable could be strongly modified by other variables, which could enhance or reduce the individual weight of each predictor. Therefore, the analysis of interactive terms further clarified the complex relationships among factors for strain 36 M. The interaction between “culture age” and “combination of the design” (

Figure 4) showed that cells aged 72 h negatively affected the performance of the strain under thermal stress conditions (35 °C), as showed by the reduction in the viable count (ca. 2 log CFU/mL) in the combinations B (pH 5) and D (pH 7.5) when 72 h old cells were used, while in the same combinations but with 24 h cells, the microorganisms experienced a general increase in viable count (1.6 log CFU/mL in the combination B, and 1 log CFU in the combination D); the negative effect of culture age was also evident in the control, where the strain always experienced an increase, but the extent of this change was lower with 72 h cells (2.4 log CFU/mL with 24 h cells and 1.2 log CFU/mL with 72 h biomass). This finding supports the hypothesis that a 24 h culture age confers a higher resilience to higher temperature, whereas at low temperature, the effect of culture age was not significant at 15 °C, as the increase in viable count was ca. 1 log CFU/mL in combination A and 1.6 log CFU/mL in combination B, independently of culture age.

In line with the evidence of the importance of interactive terms, the interaction between “combination of the design” and “sampling time” (

Figure 5) added some information on the growth kinetic of the strain 36M, and the effect of the variables, mainly pH and temperature, on the growth profile. Data, in fact, indicated that growth decline at 14 days was strong at higher temperatures (combinations B and D, with a decrease in the viable count of ca. −2.0 and −3.0 log CFU/mL). As expected, a lower temperature (15 °C) resulted in different kinetics, probably depending on the lower growth rate; in particular, in the combination A, also characterized by a lower pH (5.0), the viable count did not increase after 1 day while increasing after 14 days (1.6 log CFU/mL), as the combination of low temperature and low pH resulted in slowed growth. In the combination C (15 °C and pH 7.5) the microorganism experienced enhanced survival, as showed by the not significant effect of the predictor “sampling time”. Finally, the interaction “culture age” vs. “sampling time” (

Figure 6) confirmed the inverse relationship of viable count and culture age, revealing that microbial concentration increased more rapidly and remained even higher after 14 days when using a 24 h culture, while a strong decrease was found after 14 days when the systems had been inoculated with a 72 h biomass (decrease of −1.5 log CFU/mL).

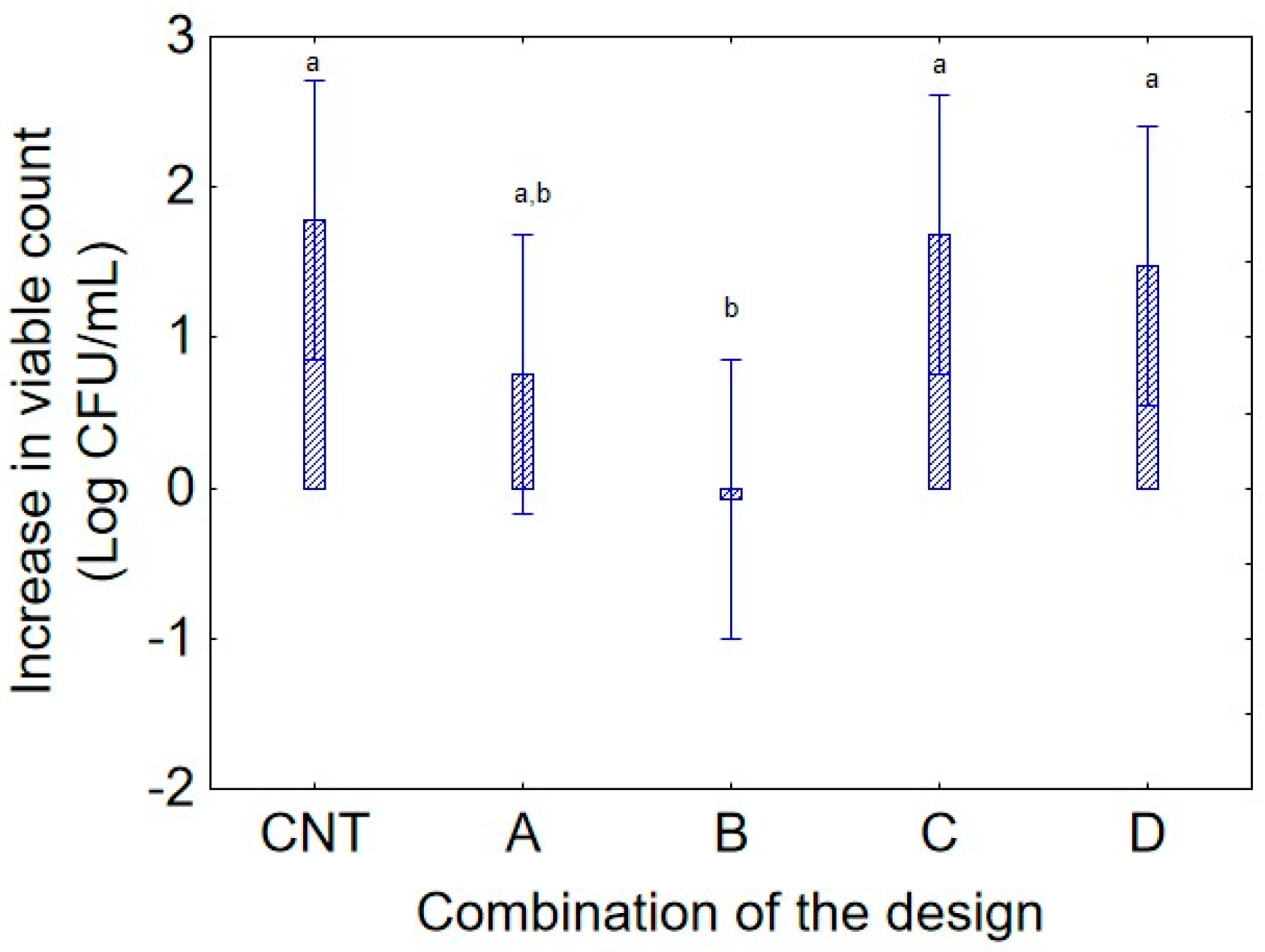

The weight of the variables was similar for the strain 20P, and the decomposition of the statistical hypothesis also provided relevant insights, confirming the evidence collected with the strain 36M, or showing some differences, mainly due to the different growth kinetics over time or for the age of culture. First, the decomposition of the predictor “culture age” showed that, in contrast to strain 36 M, the maximal increase in bacterial concentration was observed with a 72 h culture, indicating a remarkable capacity for viability and persistence over time. The analysis of “combination of the design” (

Figure 7) confirmed that combination C was a favorable condition for strain 20P, displaying a growth trend like the control (CNT) with an average increase of 1.6 log CFU/mL, while growth was not significant in combination B (37 °C and pH 5.0).

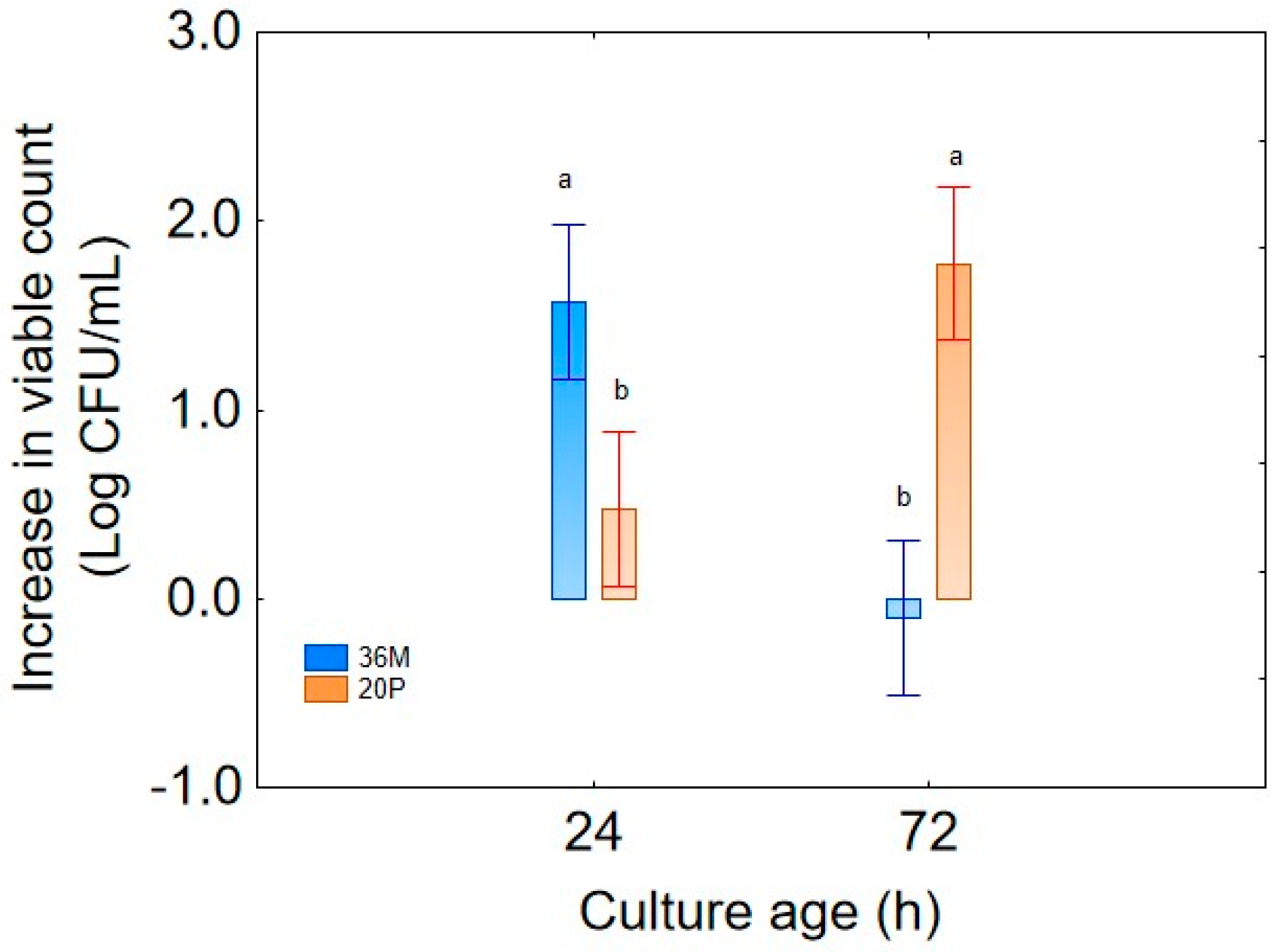

For the first step of the research, the prediction “strain” was not used as an independent variable, as the use of high number of predictors in MANOVA could complicate the interpretation of the results or lead to statistical artifacts. However, some evidence suggested the existence of possible differences depending on the strain, rather than on the other predictors (culture age, sampling time, combination of the design). Therefore, as a second step of this research, MANOVA was run again, also including the strain as a categorical predictor; the aim of this second approach was to focus on the resilience and stress resistance of the two strains. While all predictors, as single or interactive terms, were significant, the decomposition of the statistical hypothesis for some interactions pointed out the different robustness of the strains.

Figure 8 shows the different weights of culture age, highlighting that the strain 36M showed better performances with 24 h cultures (a mean increase in biomass of 1.6 log CFU/mL with no increase for the strain 20P), while the other microorganism had an opposite trend, with a generally higher increase in the viable count with 72 h cultures (a mean increase of 1.8 log CFU/mL, with no increase for the strain 36M). Also, the decomposition of the interactive term “strain” vs. “sampling time” confirmed the higher technological robustness of strain 20P, at least if intended as strain survival over time; in fact, after 14 days, the mean increase in viable count was higher than for 20P (1.0 log CFU/mL), while its was not significant for 36M (0 log CFU/mL). At day 1, differences were not recorded between the two strains as they both experienced a mean increase in viable count of 1 log CFU/mL (

Figure 9). Finally, strain effect was also evident in the trend for the different combinations of the design. In the decomposition of the statistical hypothesis for the interaction “strain” vs. “combination of the design”, the strains 36M and 20P showed the same trend in the combination B (no increase in viable count), while in combination D (incubation at 35 °C in a medium at pH 7.5), the strain 20P showed an increase (1.5 log CFU/mL) while 36M experienced a general slight decrease (−0.5 log CFU/mL). The differences were not significant for combinations A and C (an increase in the viable count of ca. 1.0 and 1.7 log CFU/mL, respectively) (

Figure 10).

4. Discussion

This study contributes to the understanding of how key environmental factors including temperature and pH could interact with an operational variable, like culture age, that is, the age of microbial biomass at the time of inoculation in the soil, and how this variable could affect the growth and resilience of PGPB strains isolated from the durum wheat rhizosphere. It is worth mentioning that soil is characterized by many variables, not only by pH and temperature. However, this study is aimed at preliminary investigating how an operational variable, like culture age, could interact strongly with soil variables and modify the persistence and viability of PGPB in soil.

The factorial experimental design combined with multifactorial ANOVA analysis provided insights into both individual and interactive effects, revealing distinct responses for

Bacillus sp. 36M and

Stenotrophomonas sp. 20P. The findings emphasize the crucial role of soil pH and temperature in bacterial growth performance, which is consistent with the broader literature indicating pH as a major determinant of microbial community structure and function [

15,

16]. As Kumar et al. reported, soil bacteria can tolerate a broad pH range, but they generally prefer values close to neutral and grow over a wide range of pH values [

1]. Soil pH is, therefore, a critical factor in field bacterial applications, as strains viable only within narrow pH ranges have limited applicability, as also demonstrated by Chari et al. [

17] for

Bacillus spp. isolates under different abiotic stress. Temperature is another key environmental factor affecting PGPB adaptation and efficacy outside their native habitats [

10,

18,

19,

20].

In our study, maximal growth was observed at under a near-neutral pH (7.5) and moderate temperatures (15 °C), which aligns with known preferences of many soil bacteria for a near-neutral pH and moderate thermal regimes for optimal metabolic activity [

9,

16]. The negative effect of high temperature (35 °C) combined with acidic or neutral pH on bacterial viability particularly highlights thermal stress as a strong selective pressure, impacting microbial network complexity through increased negative interactions [

15,

21]. This effect likely reflects enzymatic instability and the disruption of cellular homeostasis under extreme pH and thermal stress, limiting bacterial growth [

22].

Extending these observations,

Bacillus sp. 36M and

Stenotrophomonas sp. 20P exhibit distinct physiological strategies that probably arise from differences in their taxonomy and functional traits.

Bacillus species are well known for their adaptability, spore formation, and strong metabolic capabilities, including phosphate solubilization and production of IAA, siderophores, and ACC deaminase, which help plant growth and stress mitigation [

23,

24]. Conversely,

Stenotrophomonas spp., Gram-negative bacteria with wide ecological niches, are notable for sulfur and nitrogen cycling, pollutant degradation, and resilience under environmental extremes [

25]. The contrasting responses to culture age, where

Bacillus sp. 36M thrived from younger cultures while

Stenotrophomonas sp. 20P showed better growth with older cultures, may stem from differences in growth dynamics, metabolic activity, and stress tolerance mechanisms such as biofilm formation and secondary metabolite production [

26].

These findings may suggest physiological adaptations typical of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. While we did not directly measure sporulation or biofilm formation in this study, the superior performance of

Bacillus sp. 36M under moderate conditions is consistent with the literature describing endospore formation capabilities of this genus [

27]. Similarly, the persistence of

Stenotrophomonas sp. 20P with older biomass could be hypothetically associated with quorum-sensing regulation and biofilm maturation [

25], though these mechanisms require direct experimental confirmation in future studies. Such traits underline that PGPB survival is not only determined by environmental parameters but also by intrinsic regulatory networks that control energy allocation, membrane fluidity, and production of protective exopolysaccharides.

Furthermore, the decline in bacterial viability after 14 days across both strains, with differential persistence patterns, reinforces the necessity to consider temporal dynamics when evaluating PGPB efficacy. The sustained viability of

Stenotrophomonas sp. 20P at late sampling times aligns with its ecological role in maintaining soil microbial community stability under stress, supporting its candidacy as a durable biofertilizer component [

25].

These encouraging laboratory results should be cautiously extrapolated to field applications. Beyond pH and temperature, multiple abiotic and biotic variables can affect PGPB performance in situ. For example, competition with the native soil microbiome may inhibit colonization or activity of inoculated strains; moreover, soil moisture and nutrient availability are critical parameters that influence bacterial metabolism and survival but are often variable and difficult to control in field settings. Additionally, soil texture, organic matter content, and farming practices can modulate the effectiveness of PGPB-based biofertilizers. Therefore, comprehensive field validations considering this wider spectrum of environmental factors are essential to confirm and optimize the agronomic potential of selected PGPB strains [

8]. Apart from its biological relevance, this research introduces methodological innovation by applying a fractional factorial design to explore multivariate abiotic interactions in PGPB viability. This design enables simultaneous evaluation of main effects and two-way interactions with reduced experimental runs, improving statistical power and reproducibility. Unlike conventional one-factor-at-a-time approaches, factorial modeling allows the identification of synergistic or antagonistic effects that more realistically mimic field conditions [

21]. Moreover, the integration of MANOVA gives interpretative robustness, distinguishing individual and combined influences of pH, temperature, and inoculum age. This analytical strategy thus represents a valuable framework for microbial process optimization and can be extended to larger consortia or pilot-scale biofertilizer production.

Given these complexities in environmental interactions, these insights have practical implications for optimizing biofertilizer formulations and applications. Tailoring inoculum age and selecting strains based on environmental conditions may maximize bacterial survival and plant growth promotion under stress scenarios increasingly relevant due to climate change. Future studies integrating genomic and transcriptomic analysis will be valuable in dissecting stress response pathways and identifying molecular markers predictive of PGPB performance in situ [

15,

21]. Field validations across soil types and climates will further bridge laboratory findings and agronomic practicality [

27].

From an industrial and practical point of view, understanding these multifactorial relationships is fundamental for optimizing large-scale production of microbial inoculants. The formulation process—encompassing culture age, carrier selection, drying technology, and storage parameters—directly affects cell integrity and functional retention. Applying factorial experimental designs at the pilot scale could identify the most stable formulation windows, minimizing viability losses during downstream processing. Furthermore, the inclusion of physiological markers (e.g., sporulation rate, membrane integrity, enzymatic profiles) as quality control parameters would enhance reproducibility and standardization across production batches. This alignment between microbiological insight and process engineering represents a key step toward scalable, high-quality biofertilizer technologies suitable for sustainable agriculture.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the 14-day observation period, while sufficient to assess initial stress response and growth kinetics, does not capture long-term survival or adaptation dynamics that may be critical for field persistence. Second, experiments were conducted in nutrient broth under controlled laboratory conditions that do not replicate the complexity of soil ecosystems, including nutrient gradients, moisture fluctuations, and interactions with indigenous microbiota. Third, testing only two discrete levels per factor (pH 5.0 and 7.5; 15 °C and 35 °C; 24h and 72h culture age) allowed identification of significant factors and interactions but precluded determination of true optima, which would require response surface methodology. Fourth, the absence of field validation means that the agronomic relevance of these findings under real agricultural conditions remains to be demonstrated. Finally, while our ANOVA approach successfully identified significant factors and interactions, we did not develop predictive mathematical models. Future research should employ regression-based modeling to generate quantitative equations for predicting PGPB viability under specific conditions, enhancing practical applicability for biofertilizer formulation and industrial quality control.

Future studies should extend this framework by incorporating (i) nutrient availability and fertilizer interactions, which may modulate PGPB metabolic activity; (ii) co-culture systems to evaluate strain interactions; and (iii) soil matrix effects, including texture, organic matter, and indigenous microbial communities. Combining a multifactorial design with predictive modeling and field validation will bridge the gap between controlled laboratory conditions and the complexity of agricultural ecosystems.