Abstract

Transmission tower guy wires are critical flexible tension members ensuring the stability and safe operation of overhead power transmission networks. However, these components are vulnerable to external impacts from falling rocks, ice masses, and other natural hazards, which can cause excessive deformation, anchorage loosening, and catastrophic failure. Current design standards primarily consider static loads, lacking comprehensive models for predicting dynamic impact responses. This study presents a theoretical model for predicting the peak impact response of guy wires by modeling the impact process as a point mass impacting a nonlinear spring system. Using an energy-based elastic potential method combined with cable theory, analytical solutions for axial force, displacement, and peak impact force are derived. Newton–Cotes numerical integration solves the implicit function to obtain closed-form solutions for efficient prediction. Validated through finite element simulations, deviations of peak displacement, peak impact force, and peak axial force between theoretical and numerical results are within ±4%, ±18%, and ±4%, respectively. Using the validated model, parametric studies show that increasing the inclination angle from 15° to 55° slightly reduces peak displacement by 2–4%, impact force by 1–13%, and axial force by 1–10%. Higher prestress (100–300 MPa) decreases displacement and impact force but increases axial force. Longer lengths (15–55 m) cause linear displacement growth and nonlinear force reduction. Impacts near anchorage points help control displacement risks, and impact velocity generally has a more significant influence on response characteristics than impactor mass. This model provides a scientific basis for impact-resistant design of power grid infrastructure and guidance for optimizing de-icing strategies, enhancing transmission system safety and reliability.

1. Introduction

Globally, electricity transmission relies more and more on high-voltage transmission lines. Particularly in China, as of the end of 2024, the total length of transmission lines rated at 35 kV and above has reached 2.477 million kilometers, crisscrossing the country from east to west and north to south [1]. All of these transmission lines are supported by transmission towers. Since the lines cut through a variety of terrains, the associated transmission towers are exposed to complex geographical and climatic conditions.

In transmission towers, guy wires, as critical components for ensuring the safe and stable operation of power transmission networks, are widely used flexible tension members in power systems [2]. Throughout their service life, these members are continuously exposed to natural environments and vulnerable to various external impacts [3]. For example, in mountainous regions, transmission towers may be impacted by falling rocks or uprooted trees, which can cause significant stress on tower foundations and potentially lead to structural failure [4]; in high-altitude areas, by falling ice and snow; in strong winds, by wind-borne debris [5]; and in coastal regions, by hard objects carried by typhoons, which annually attack the coastal areas of South China and cause varying degrees of damage to overhead lines [2]. Such impacts can induce excessive tensile deformation in guy wires and loosening of anchorage components [1]. In severe scenarios, these effects may result in fractures at tower nodes and overall structural instability, thereby threatening transmission reliability [6].

Current designs of transmission towers mainly adhere to static load specifications (e.g., DL/T 5486-2020 [7]), with insufficient attention paid to the dynamic mechanical behavior under transient impact loads [8]. Developing a theoretical model for the impact response of transmission tower guy wires and quantifying key parameters during impact processes [4] is therefore essential to address the gap between static design and actual service conditions, which is of practical value for enhancing the impact-resistant design [6] and improving the overall safety of power grid infrastructure.

As a typical type of flexible cable structure, the impact response of transmission tower guy wires can be examined within the broader framework of cable structure dynamics research. Currently, in terms of theory, studies on the impact response of cable structures largely rely on finite element simulations. For instance, Judge et al. [8] revealed the influence of impact angle on fracture risk through simulations of bullet impacts on steel cables. Wu Zhijie [9] demonstrated that increased prestress enhances the impact resistance of steel strands via simulations. Hakim et al. [10] discovered that larger hammer diameters lead to higher impact forces and shorter impact durations through numerical studies of drop-weight impacts on composite materials. Nevertheless, they lack universal theoretical models tailored to the specific components and operating conditions of power guy wires. Experimentally, tests like Feng Junzhu et al.’s [11] on lateral impacts on steel wire ropes have accumulated data. However, for the response of cable-stayed structures under impact, theoretical derivations remain scarce.

In the field of cable structure theory and modeling methods, Irvine’s nonlinear analysis of flat cables [12] and Wu Qingxiong’s [13] derivation of concentrated force configurations for stay cables concurrently laid the foundation for mechanical modeling of cable structures. However, both theoretical frameworks [12,13] are strictly limited to static loading scenarios, with no consideration of dynamic behavior under transient impact loads. This lack of dynamic analysis represents a critical limitation for power guy wires, which operate under distinct conditions not fully addressed by existing theories. Power guy wires are typically installed at specific inclinations from horizontal, operate with initial prestress levels within a certain range, have specific span lengths, and are frequently exposed to impact loads from falling rocks, ice masses, and de-icing operations. These specific operating conditions introduce gravitational effects, stiffness modulation, and geometric nonlinearities that create complex dynamic behaviors requiring specialized theoretical treatment beyond the static equilibrium approaches of Irvine [12] and Wu Qingxiong [13].

Recent advances in nonlinear spring models for flexible body collisions provide valuable insights for simplified modeling of cable impact responses. Specifically, tether element models [14] and mass-spring-damper systems [15] have demonstrated effective approaches for capturing dynamic interactions in flexible structures. These modeling techniques, when integrated with the static cable mechanics principles established by Irvine [12] and Wu Qingxiong [13], offer a promising pathway to develop a comprehensive theoretical framework for power guy wire impact responses. This integration of static cable theory with dynamic spring modeling approaches forms the conceptual basis for the theoretical development presented in this study.

Such a theoretical framework is urgently needed because transmission tower guy wires are vital to grid operational safety, yet current research on their impact responses mostly relies on numerical simulations [8,9,10], lacking theoretical models that can accurately predict peak indices (e.g., axial force, displacement) critical for anti-impact design. Moreover, existing standards (e.g., DL/T 5486-2020 [7]) only consider static loads, ignoring dynamic behavior under transient impacts, leading to blind spots in engineering design and elevated accident risks.

To address the above critical gaps, this study is driven by the need to establish a quantitative theoretical framework for guy wire impact responses. The specific objectives are as follows: to develop a theoretical model integrating cable theory with energy-based elastic potential methods; to derive closed-form analytical solutions for key response parameters including axial force, displacement, and peak impact force; to validate the theoretical model through systematic finite element simulations; to analyze the influence of key parameters such as inclination angle, prestress level, and impact conditions on response characteristics; and to provide practical guidance for engineering anti-impact design optimization.

To achieve these research objectives, this paper focuses on the impact response characteristics of guy wires, equivalently modeling the impact process as a point mass impacting a nonlinear spring system. By solving for equivalent stiffness using cable theory and combining energy methods to derive calculation formulas for axial force, displacement, and peak impact force, this study provides theoretical support for the impact-resistant design of guy wire structures in power systems.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the development of the theoretical model for guy wire impact response. Section 3 describes the numerical validation and parametric analysis, where finite element simulations are conducted to verify the theoretical model, followed by systematic investigations of how guy wire characteristics (inclination angle, prestress, length) and impact conditions (position, mass, velocity) influence the dynamic response. Finally, Section 4 summarizes the key findings and discusses the practical implications of this research.

2. Development of a Theoretical Model for the Impact Response of Transmission Tower Guy Wires

2.1. Theoretical Model for Guy Wire-Impactor Collisions

2.1.1. Development of the Theoretical Calculation Model for Guy Wires

As mentioned above, research on guy wires remains scarce. Given the similar structural characteristics between transmission tower guy wires and stay cables, studies on the latter serve as a valid reference herein. In engineering practice, stay cables primarily sustain high axial tensile forces, are typically fabricated from high-toughness steel strands (composed of twisted steel wires) with inherently low bending stiffness, and their deformation under impact loading is predominantly governed by axial stretching, which is consistent with findings in [10,13,16,17,18], leading to their common approximation as flexible cable chains with negligible bending stiffness, as shown in Figure 1. Meanwhile, the load on the cable is uniformly distributed along the tangent direction [13]. As a result, two factors can be neglected [13]: first, the impact force perpendicular to the secant direction; second, the deformation of the infinitesimal element along the secant direction.

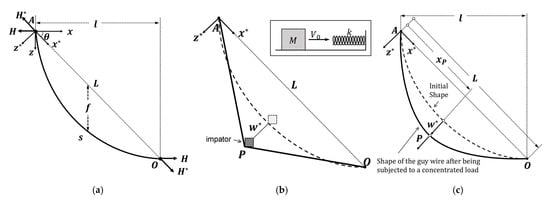

Figure 1.

(a) A theoretical model of guy wire; (b) impact of the impactor on the guy wire (sub-figure: simplified model of impact by the impactor on the guy wire); (c) configuration of the guy wire under concentrated load.

In Figure 1a, and represent the anchor point and intersection point of the guy wire, respectively. The distance between and is , with a horizontal distance of . and denote the inclination angle and curvature of the guy wire, respectively. Furthermore, the direction of OA is defined as the tangent direction. Establish a global coordinate system with origin at , the horizontal plane containing the guy wire as the -axis, and the plumb line downward as the -axis direction. Simultaneously, establish an -axis along the OA direction with origin at , and define the -axis perpendicular to OA and pointing downward, establishing the secant coordinate system . Let denote the horizontal component of axial force, and denote the tangent-direction component of axial force.

2.1.2. Simplified Model of Impactor Collision

Let the mass of the impactor be and its initial velocity be . Under the impact of the above impactor, the maximum displacement of the guy wire is (see Figure 1b). During the impact process, the following four assumptions are made.

First, the guy wire primarily undergoes axial deformation along the tangential direction. Thus, it is assumed that regardless of the impactor’s direction, the force exerted on the guy wire is perpendicular to its tangential direction. For vertical impacts (e.g., falling rocks, ice masses), this assumption is implemented by decomposing the impact direction into perpendicular and parallel components relative to the tangent—only the perpendicular component drives axial deformation.

Second, the stiffness of the impactor (e.g., a rolling rock) is far greater than that of the guy wire. Therefore, the impactor is treated as a rigid body.

Third, radial deformation of the guy wire (e.g., diameter contraction) has a negligible effect on axial force transmission. Accordingly, radial deformation is ignored.

Fourth, the impact duration is extremely brief, with negligible contributions from damping dissipation and thermal energy loss. Therefore, it is approximated that the entire mechanical energy of the impactor is converted into elastic potential energy of the guy wire.

Based on the above considerations, the impacted guy wire can be simplified as a nonlinear spring with continuously varying stiffness. Let the equivalent stiffness of the guy wire be denoted as . During the impact, the change in mechanical energy of the impactor, , is equated to the change in potential energy of the guy wire (nonlinear spring), . Consequently, the peak axial force of the guy wire, the peak displacement at the impact point, and the peak impact force can be determined.

2.2. Configuration of a Guy Wire Under Concentrated Loads

As shown in Figure 1c, a concentrated load acts at position perpendicular to the direction of the guy wire’s secant line. Since the additional movement of the guy wire caused by the concentrated force is negligible, the sag of the guy wire is small. Therefore, it can be assumed that the tension in the guy wire still satisfies the flat guy wire assumption. In the secant coordinate system , under its own weight, the initial vertical coordinate of point P on the stay guy wire is , and the horizontal axial force is . Under the concentrated load, the incremental vertical displacement at this point is , the axial displacement is neglected, and the incremental horizontal axial force is . Therefore, the total vertical displacement is , and the total horizontal axial force is .

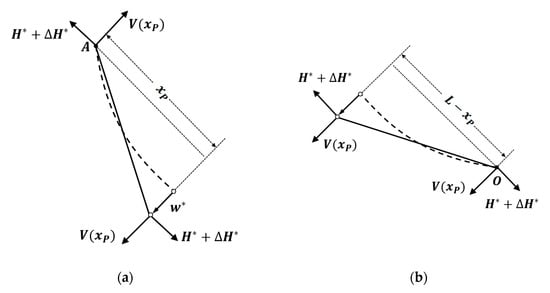

As shown in Figure 2a, when , the reaction force at the left end of the guy wire under its own weight is (vertical secant upward). Within the range , the guy wire’s self-weight load is (perpendicular to the secant line, pointing downward). Under the concentrated force, the reaction at the left end of the guy wire is (perpendicular to the secant line, pointing upward).

Figure 2.

Forces on each section of the guy wire: (a) ; (b) .

As shown in Figure 2b, when , under self-weight, the reaction force at the left end of the guy wire is (vertical tangent upward). For , the self-weight load on the guy wire is (vertical tangent downward). Under the action of a concentrated force, the left-end reaction force of the segment is —P (perpendicular to the secant line and upward).

Under the combined effects of self-weight and concentrated forces, the vertical component of guy wire tension in the segments and is uniformly given by . It is perpendicular to the secant line, pointing upward on the interval and downward on the interval .

Therefore, under self-weight, the vertical equilibrium equation for a flat inclined guy wire is

Therefore, under self-weight, the vertical equilibrium equation for the guy wire is

Combining Equations (1) and (2) and eliminating the self-weight term yield the vertical equilibrium equation, i.e.,

where and . Substituting the latter into Equation (3), the integral yields a dimensionless expression

where the dimensionless vertical displacement is defined as , the dimension-less concentrated load is , ; and .

The relationship between axial force increment and displacement [13] is given by

where . Substituting into Equation (5), we obtain

Rearranging the above equation yields the cubic equation for the horizontal component of the guy wire force under concentrated load

where and .

Equation (7) can be solved by the Newton–Raphson method. This yields the horizontal component of the guy wire force under concentrated loading. Substituting into Equation (4) provides the displacement of the stay guy wire under the concentrated force .

2.3. Solving the Response of a Guy Wire After Impact Using the Energy Method

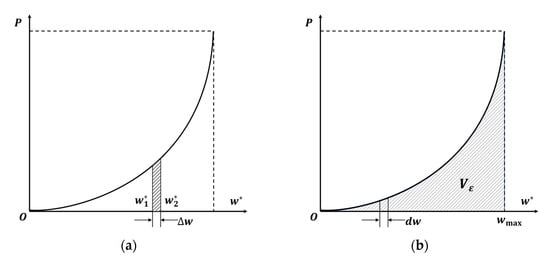

As shown in Figure 2b,c, Figure 3 and Figure 4, under the action of a concentrated force perpendicular to the tangent direction, the displacement of the guy wire’s load point is . Based on the calculation formula for the guy wire configuration under concentrated load, a mapping relationship between the concentrated force and the displacement of the guy wire’s load point is established. The results are shown in Figure 3a.

Figure 3.

(a) Concentrated force vs. the displacement ; (b) solution schematic diagram.

Figure 4.

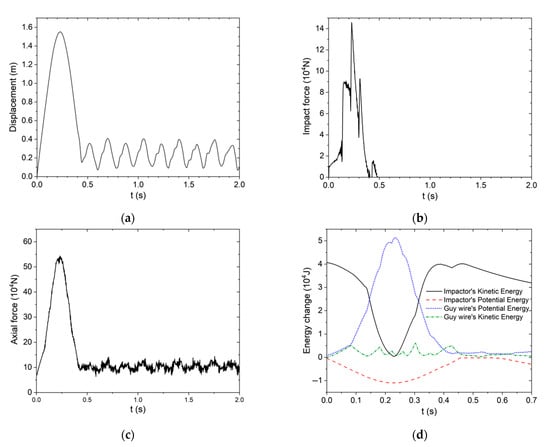

Time–history curve of (a) displacement, (b) impact force, (c) axial force and (d) energy change obtained by the numerical simulation.

In Figure 3a, the curve illustrates the equivalent stiffness of the guy wire. increases with increasing and exhibits a nonlinear relationship. For a small displacement , the work performed by is

When the guy wire undergoes its maximum displacement under the impact of the projectile, the kinetic energy of the projectile perpendicular to the tangent direction is zero. At this point, the change in mechanical energy of the projectile can be expressed as

where represents the mass of the impactor, denotes the impact velocity of the impactor, and is the angle between the impact direction and the tangent direction of the guy wire.

Since the guy wire is a nonlinear elastic material, its stiffness increases with increasing applied force. Therefore, the energy change in the guy wire can be expressed as

According to the law of conservation of energy, we obtain

i.e.,

is an implicit function. As a result, direct integration cannot be used to solve for . Therefore, first, the maximum displacement of the guy wire corresponding to each concentrated force within a certain range is calculated using Equations (4) and (7). Then, the Newton–Cotes integration formula is applied to solve for . Figure 4b illustrates the solution process for the potential energy variation of the guy wire when its maximum deformation is .

3. Dynamic Simulation of Guy Wire Impact Response

In the previous section, the development of the theoretical model for guy wire impact response was presented, including the establishment of the collision model and the derivation of analytical solutions using energy-based methods. Based on Equations (4), (7) and (11), the analytical solutions for key responses of guy wires under impact loads, including axial forces, displacements and impact force peaks, can be directly obtained. Meanwhile, the conversion of impact kinetic energy to elastic potential energy can be quantified. Furthermore, by means of Newton–Cotes numerical integration, the implicit function is solved to obtain a closed-form solution, thus achieving the efficient theoretical prediction of response peaks.

Building upon these theoretical foundations from Section 2, this section presents a comprehensive analysis that integrates both theoretical predictions and numerical simulation results. The numerical simulations, performed using ANSYS LS-DYNA 2022 R1, serve two primary purposes: first, to validate the theoretical model through systematic computational analysis; and second, to provide complementary insights that mutually reinforce the theoretical findings. Ultimately, by synthesizing results from both theoretical investigations and ANSYS-based numerical simulations, and focusing on specific case studies (see Table 1), this section examines how key parameters influence the guy wire’s response to external impacts, ensuring a robust and validated understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

Table 1.

The parameter values of the finite element model.

3.1. Model Establishment and Solution

This subsection validates the theoretical model through energy conversion efficiency analysis, the first step in the integrated theoretical–numerical approach. Energy conversion efficiency is quantified by comparing theoretical predictions of guy wire elastic potential energy with ANSYS LS-DYNA simulation results of impactor mechanical energy, verifying the energy conservation assumption. This analysis validates the theoretical model and establishes a reference benchmark based on specific case parameters (Table 1), enabling systematic comparison of theoretical and numerical results in subsequent subsections.

To implement this validation and establish the reference benchmark, a representative case is defined based on typical material properties of power guy wires and actual engineering conditions [19], the guy wire is set with a inclination angle relative to the ground, a length of 30 m, a radius of 0.0122 m, and a prestress of 150 MPa (overall parameter values are shown in Table 1). The impactor is set with a mass of 1000 kg and a velocity of 9 m/s. It strikes the midpoint of the guy wire.

Using the above parameter values and the finite element method, the dynamic response of the guy wire under impact is simulated by ANSYS LS-DYNA. Figure 4 show the time–history curve of the displacement, the impact force and the axial force (displacement direction corresponds to the impact direction). The latter are obtained by the numerical simulation.

As shown in Figure 4b, the impact force time–history curve exhibits multiple peak points. The peak points appearing before 0.4 s result from the acceleration at the impact point of the tension wire not always matching that of the impactor during the impact process. Specifically, When the acceleration at the tension wire’s force point is less than that of the impactor, the impact force increases; when the acceleration is greater than that of the impactor, the impact force decreases. Repeating this process results in multiple extreme points on the impact force time–history curve. The extreme points appearing after 0.4 s are caused by the brief re-contact between the impactor and the cable after the cable rebounds following separation from the impactor.

In the theoretical derivation, it is assumed that all the kinetic energy and gravitational potential energy of the impactor are converted into the elastic potential energy of the guy wire. To preliminarily verify the accuracy of this theoretical assumption, the energy time–history curves of the impactor and the guy wire are compared. The time–history curves of the energy variation (kinetic energy and gravitational potential energy) for both the impactor and the guy wire are shown in Figure 4d.

As can be seen from Figure 4d, both the kinetic energy and gravitational potential energy of the impactor reach their minimum values around 0.23 s, while the elastic potential energy of the guy wire reaches its maximum around 0.23 s. The kinetic energy of the guy wire changes very little. The initial kinetic energy of the impactor is 40,482 J. At 0.23 s, the change in gravitational potential energy of the impactor is 10,996 J, while the change in elastic potential energy of the guy wire is 50,448 J. From the above analysis, it can be seen that the kinetic energy and gravitational potential energy of the impactor are essentially converted into the elastic potential energy of the guy wire, confirming the validity of the theoretical assumption. Notably, the “near-100% energy conversion” here aligns with the theoretical simplification; in reality, the frictional sliding of the impactor (observed in Section 3.2.1) causes slight energy dissipation, making the actual conversion efficiency marginally lower than 100% and this aligns with the conservative nature of the theoretical assumption.

3.2. Analysis of the Influence of Guy Wire Characteristics on Its Dynamic Response

Based on the above parameter settings, this section of this study investigates how variations in the guy wire’s own parameters (the guy wire’s ground inclination angle, prestress and length) affect the guy wire’s dynamic behavior.

3.2.1. Analysis of the Influence of the Guy Wire’s Ground Inclination Angle

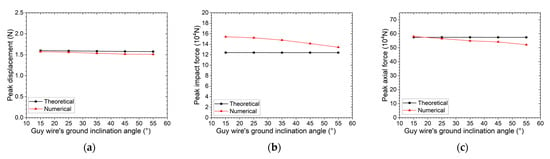

As shown in Figure 5, with the guy wire’s ground inclination angle increasing from 15° to 55°, the simulated results for peak displacement, peak impact force, and peak axial force all decrease significantly, while the theoretical results remain nearly constant with minimal variation.

Figure 5.

(a) Peak displacement, (b) peak impact force, and (c) peak axial force vs. the guy wire’s ground inclination angle.

Quantitatively, the theoretical peak displacement only decreases slightly from 1.5991 m to 1.5734 m (a reduction of approximately 1.6%), and the theoretical peak impact force and axial force change by less than 0.1% (from 124,010 × 104 N to 123,970 × 104 N and 574,450 × 104 N to 573,930 × 104 N, respectively). In contrast, the numerical simulation results show more obvious downward trends: peak displacement decreases from 1.5722 m to 1.5081 m (a reduction of about 4.1%), peak impact force drops from 154,129 × 104 N to 134,304 × 104 N (a reduction of approximately 12.9%), and peak axial force decreases from 580,356 × 104 N to 521,194 × 104 N (a reduction of about 10.2%).

This discrepancy arises because during numerical simulations, the impactor slides downward along the guy wire under gravity immediately upon contact—this sliding motion induces frictional dissipation of the impact energy’s parallel component (relative to the cable tangent), which aligns with the theoretical assumption that only the perpendicular component contributes to the guy wire’s axial deformation. As the inclination angle increases, this downward sliding tendency becomes more pronounced, leading to greater energy loss through friction between the impactor and the guy wire.

The results above indicate that axial force, impact force, and displacement are all minimally affected by changes in the ground inclination angle of the guy wires in theoretical predictions, while numerical simulations reflect more significant sensitivity due to friction effects. Increasing the ground inclination angle of the guy wires on the guyed tower can relatively enhance the guy wires’ ability to resist impact loads. This finding holds significant practical reference value for real-world applications. In addition, Figure 5 reveals a negative correlation between the ground inclination angle of the guy wire and the peak response values for displacement, impact force, and peak axial force. This implies that in areas susceptible to external impact loads, the safety of guy wires can be enhanced by moderately increasing their inclination angle (e.g., from 15° to 55°), which can reduce the simulated peak impact force by over 10% and peak axial force by around 10% without significant changes in theoretical prediction stability.

3.2.2. Analysis of the Effects of Prestressing

While inclination angle influences stiffness through geometric force redistribution, prestress directly modulates the initial axial stiffness of guy wires. These two parameters interact synergistically to determine the fundamental mechanical properties governing impact resistance. Whereas inclination angle affects the spatial distribution of forces, prestress provides a direct means to adjust the baseline stiffness, making it a more controllable parameter in engineering design.

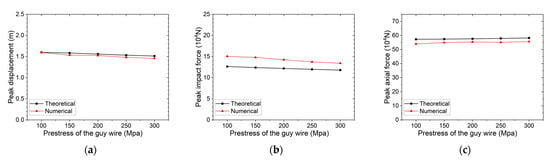

Figure 6 illustrates the effects of guy wire prestress (100–300 MPa) on peak displacement, peak impact force, and peak axial force. Quantitatively, as prestress increases from 100 MPa to 300 MPa, theoretical and numerical results consistently show: peak displacement decreases by approximately 5.4% (theoretical) and 8.6% (simulation), peak impact force reduces by around 6.7% (theoretical) and 10.8% (simulation), while peak axial force increases by only 1.7% (theoretical) and 3.1% (simulation). This trend arises because higher prestress enhances the guy wire’s initial equivalent stiffness, improving impact resistance and reducing deformation; the more significant response changes in simulations align with the friction-induced energy dissipation observed in Section 3.2.1, as stiffer guy wires amplify friction’s influence on response variation.

Figure 6.

(a) Peak displacement, (b) peak impact force, and (c) peak axial force vs. the prestress.

The results above indicate peak axial force is minimally sensitive to prestress, while peak impact force and displacement show notable reductions—this differential sensitivity stems from stable total energy conversion (constant impactor mass/velocity) and stiffness-mediated force-deformation redistribution. In summary, increasing prestress effectively enhances impact resistance (over 8% displacement reduction and 10% impact force reduction in simulations) with only slight axial force growth, offering a controllable way to balance deformation control and structural safety in engineering design, complementing the geometric stiffness effects of inclination angle.

3.2.3. Analysis of the Effects of Guy Wire Length

Prestress establishes the initial stiffness baseline, but guy wire length further modifies the effective stiffness distribution along the span, and this modification aligns with the load–displacement relationship derived for concentrated forces (Section 2.2) and energy conservation verification (Section 2.3). These two theoretical foundations together indicate that length-induced stiffness variation significantly alters dynamic response characteristics, and this effect becomes more pronounced when combined with prestress adjustments to tune initial stiffness.

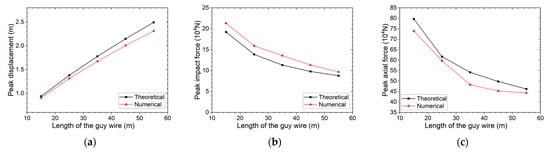

Figure 7 illustrates the effect of guy wire length (15–55 m) on peak displacement, peak impact force, and peak axial force. Quantitatively, as length increases from 15 m to 55 m, theoretical and numerical results consistently show: peak displacement increases by approximately 165.3% (theoretical) and 155.1% (simulation) in a nearly linear trend, while peak impact force reduces by around 54.4% (theoretical) and 54.5% (simulation), and peak axial force decreases by about 42.0% (theoretical) and 39.0% (simulation)—both forces exhibit nonlinear reduction with gradually slowing decay rates.

Figure 7.

(a) Peak displacement, (b) peak impact force, and (c) peak axial force vs. the length of the guy wire.

The results above indicate that length adjustment offers a practical trade-off in engineering design: moderately increasing guy wire length can cut peak impact force by over 50% and axial force by nearly 40% (simulation data), but displacement must be constrained by safety codes to avoid interphase flashover. This quantitative rule complements the stiffness modulation effects of inclination angle and prestress, forming a comprehensive optimization framework for balancing force control and deformation limits in guy wire impact-resistant design.

3.3. Analysis of the Impact of Impact Factors on the Dynamic Response of the Guy Wire

3.3.1. Analysis of the Influence of Impact Position

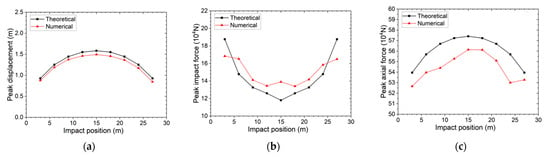

Having examined how inherent guy wire characteristics determine the overall stiffness distribution, we now shift focus to how external impact conditions interact with this stiffness field. Impact position is particularly significant as it determines which segment of the stiffness distribution is primarily engaged during impact, thereby influencing local deformation patterns and force transmission efficiency.

Figure 8 illustrates the effect of impact position (3–15 m, from anchorage point to midpoint) on peak displacement, peak impact force, and peak axial force. Quantitatively, as impact position moves from 3 m to 15 m: peak displacement increases by approximately 71.0% (theoretical) and 70.2% (simulation) in a decelerating growth trend; peak axial force increases by about 6.4% (theoretical) and 6.6% (simulation) with gradually slowing growth; peak impact force shows a nonlinear trend—theoretical values decrease by 37.1% (from 187,630 × 104 N to 118,000 × 104 N), while simulation values first decrease then slightly rise (from 168,318 × 104 N to 139,004 × 104 N), with both showing reduced variation near the midpoint.

Figure 8.

(a) Peak displacement, (b) peak impact force, and (c) peak axial force vs. the impact position.

The results above indicate that impact position significantly affects local response: impacts near anchorage points (e.g., 3 m) yield 70% lower displacement than midpoint impacts, helping control safety distance risks; midpoint impacts exhibit larger deformation but stable force transmission. In engineering design, priority should be given to protecting midpoint regions with impact-resistant baffles, while leveraging the high stiffness of anchorage ends to constrain displacement. This quantitative rule complements the stiffness modulation effects of inclination angle, prestress, and length, providing targeted guidance for impact-resistant optimization based on potential impact positions.

3.3.2. Analysis of the Impact of Mass Quantity

Impact position defines where the impact energy is initially applied, but the magnitude of that energy depends on the impactor’s physical properties. Mass is a fundamental parameter determining impact energy (), and its linear relationship with momentum makes it a key factor in force transmission dynamics. Unlike position effects which are localized, mass influences the global energy input to the system.

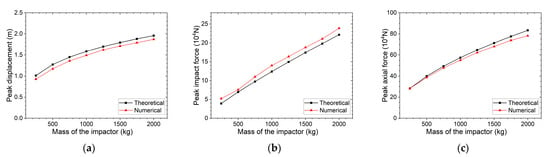

Figure 9 demonstrates the effect of impactor mass on peak displacement, peak impact force, and peak axial force. Quantitatively, as mass increases from 250 kg to 1250 kg: peak displacement exhibits nonlinear growth with slowing rates, increasing by approximately 67.7% (theoretical, from 1.0126 m to 1.6976 m) and 74.6% (simulation, from 0.928 m to 1.62 m); peak axial force also shows nonlinear growth, rising by about 129.5% (theoretical, from 281,700 × 104 N to 646,600 × 104 N) and 120.9% (simulation, from 281,340 × 104 N to 621,770 × 104 N); while peak impact force increases approximately linearly, with theoretical values growing by 281.3% (from 39,190 × 104 N to 149,410 × 104 N) and simulation values increasing by 213.6% (from 52,110 × 104 N to 163,410 × 104 N).

Figure 9.

(a) Peak displacement, (b) peak impact force, and (c) peak axial force vs. the mass of the impactor.

The results above indicate that impactor mass exerts differential influences on responses: linear control over peak impact force, and nonlinear modulation of peak displacement and axial force with diminishing growth rates. For large-mass impacts (e.g., ≥1000 kg), higher prestress is required to constrain displacement (which increases by over 70% in simulations), while careful attention must be paid to axial force limits to avoid material failure. This quantitative rule complements the influence of impact position and guy wire inherent parameters (inclination angle, prestress, length), providing targeted guidance for impact-resistant design in areas prone to large-mass falling objects (e.g., mountainous regions)—such as prioritizing stiffness optimization to balance force control and deformation limits.

3.3.3. Analysis of the Impact of Impactor Velocity

Mass and velocity jointly determine impact energy through the kinetic energy relationship, but their influences differ fundamentally due to velocity’s quadratic effect. This mathematical relationship means velocity exerts a more dominant influence on impact severity: doubling velocity increases energy fourfold, while doubling mass only doubles energy. For example, increasing velocity from 3 m/s to 11 m/s (≈3.67-fold increase) boosts theoretical kinetic energy by ≈13.4-fold, whereas increasing mass from 250 kg to 1250 kg (5-fold increase) only raises energy by 5-fold—this velocity dominance has critical implications for impact protection strategy prioritization.

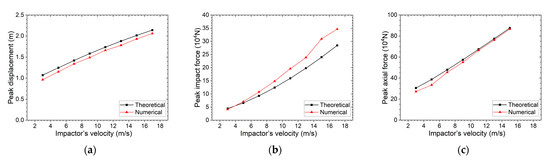

As shown in Figure 10, both peak axial force and peak displacement exhibit near-linear growth with increasing impactor velocity. Quantitatively, as velocity rises from 3 m/s to 11 m/s: peak displacement increases by approximately 62.5% (theoretical, from 1.0691 m to 1.7363 m) and 72.6% (simulation, from 0.962 m to 1.66 m); peak axial force rises by about 120.6% (theoretical, from 305,130 × 104 N to 673,200 × 104 N) and 144.1% (simulation, from 271,569 × 104 N to 662,833 × 104 N).

Figure 10.

(a) Peak displacement, (b) peak impact force, and (c) peak axial force vs. the impactor’s velocity.

More significantly, a comparison of Figure 9 and Figure 10 reveals the following: for equivalent energy input, the rate of change in peak responses induced by velocity is substantially greater than that induced by mass. Simulation results show velocity-induced displacement growth (72.6%) is nearly equivalent to mass-induced growth (74.6%) despite a 30% lower velocity multiple (3.67-fold vs. 5-fold mass); meanwhile, velocity-induced impact force growth (375.1%) is 1.8-fold that of mass-induced growth (213.6%). This velocity-dominant influence arises from an energy mechanism: since kinetic energy is proportional to the square of velocity, velocity has a far greater influence on response than mass.

These distinct characteristics reveal the dominant role of the velocity component in impact kinetic energy regarding the damage potential to guy wire structures. In high-speed impact risk areas (such as mountainous regions), velocity control measures (e.g., buffer devices) should be prioritized over simply increasing guy wire strength. This provides a clear optimization direction for impact-resistant protection design. For instance, in scenarios prone to high-speed impacts (such as mountain rockfalls or high-speed falling objects), controlling impact velocity should be a key focus. Specifically, installing buffer deceleration devices and optimizing the energy absorption characteristics of protective structures can more effectively mitigate impact hazards. This prevents guy wire breakage or tower instability caused by excessive axial force and displacement resulting from high impact speeds. Such measures further enhance the impact-resistant safety redundancy of transmission networks.

3.4. Integrated Analysis and Key Findings Summary

Building upon the systematic investigations presented in Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 3.3 this section synthesizes the fundamental insights into guy wire impact behavior, revealing the interconnected relationships between parameters and their combined effects on dynamic response. By integrating individual parameter analyses into a cohesive framework, this synthesis addresses the complex interplay of factors governing impact resistance and response characteristics.

3.4.1. Model Validation and Foundation Establishment

The theoretical model validation confirmed effective energy conversion, with the kinetic and gravitational potential energy of the impactor being essentially converted into the elastic potential energy of the guy wire. This validation establishes the model’s reliability for predicting peak responses, with theoretical and numerical results showing consistent trends across all parameter configurations. Specifically, deviations between theoretical and numerical results are strictly controlled within ±4% for peak displacement and peak axial force, and within ±18% for peak impact force. This level of agreement validates the model’s accuracy for engineering applications. The larger deviation in peak impact force primarily arises from friction-induced energy dissipation during impactor sliding (observed in Section 3.2.1), which is simplified in the theoretical model but fully captured in numerical simulations.

Despite these discrepancies, the parametric trend consistency is maintained: for example, increasing the guy wire’s ground inclination angle from 15° to 55° leads to theoretical reductions of 2–4% in peak displacement, 1–13% in peak impact force, and 1–10% in peak axial force, which aligns closely with numerical simulation trends (displacement reduction ~4.1%, impact force reduction ~12.9%, axial force reduction ~10.2%). This consistency further confirms the model’s validity for guiding parameter optimization.

3.4.2. Parameter Influence Hierarchy

A clear influence hierarchy emerges from the comprehensive investigation. Impact velocity dominates response severity due to its quadratic relationship with kinetic energy, exerting a substantially greater influence than mass for equivalent energy input. Guy wire stiffness, collectively determined by prestress, length, and inclination angle, governs energy absorption capacity.

Prestress offers the most direct means of stiffness control, with increasing prestress reducing displacement while increasing axial force. Length exhibits a linear inverse relationship with displacement, while inclination angle demonstrates nonlinear effects due to friction in numerical simulations. Impact position influences local response distribution but has minimal effect on global energy absorption, with midspan impacts producing significantly greater displacement than anchorage impacts due to substantial stiffness variation between these regions.

3.4.3. Critical Parameter Interactions

Several key parameter interactions amplify or mitigate individual effects. Higher prestress is particularly effective in mitigating high-velocity impacts, reducing velocity-induced displacement growth compared to low-prestress configurations. Longer spans exhibit more pronounced position effects due to amplified stiffness gradients. The geometric nonlinearity of guy wires creates a self-limiting effect for large-mass impacts, with stiffness increasing during deformation to constrain displacement growth despite increasing impact energy.

3.4.4. Response Trade-Offs and Design Implications

The integrated analysis reveals inherent response trade-offs that guide engineering design. Increasing stiffness via prestress or inclination angle reduces displacement but increases internal forces, requiring careful balance to avoid material failure. Velocity control is far more efficient than mass control for energy reduction due to the quadratic relationship between velocity and kinetic energy. Midspan protection is critical for displacement control, while anchorage zones provide natural stiffness advantages for force management.

This synthesis establishes a comprehensive understanding of guy wire impact behavior, moving beyond isolated parameter effects to reveal the interconnected mechanisms governing response. The findings provide a systematic basis for impact-resistant design, with clear guidance on parameter prioritization and interaction management, forming a cohesive foundation for the engineering implications discussed in Section 4.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

To address the gap of insufficient quantitative models for transmission tower guy wire impact responses, this study’s core contributions to the topic are reflected in its integrated theoretical–numerical framework and engineering insights: we proposed a targeted theoretical model—analogizing impact as a “point mass-nonlinear spring system”, integrating cable theory with an energy-based elastic potential method to derive closed-form solutions for peak axial force, displacement, and impact force; introduced Newton–Cotes numerical integration to efficiently solve the implicit energy function for rapid response prediction; validated the model via ANSYS LS-DYNA, quantifying deviations to ensure reliability; systematically revealed parametric influence laws for engineering optimization; and bridged theory with practice to support impact-resistant design of power grids and de-icing strategy optimization.

While theoretical and numerical results show minor discrepancies (due to omitted guy wire kinetic energy and impactor slip dissipation), their parameter influence trends remain highly consistent. Notably, the perpendicular impact force assumption works best for 15–55° guy wires (typical in engineering) and may have minor errors for rarely used near-vertical ones (>80°). Additionally, the “no energy loss” assumption (Section 2.1.2), though simplifying derivation, may slightly over-predict peak displacement and force, and this conservatism aligns with safety-focused engineering principles. Future work will add damping/frictional models to quantify real energy losses and improve accuracy. Despite these assumption limitations, their consistent trends still clearly reveal key guy wire parameters’ impacts on displacement, axial force, and peak impact force. Furthermore, the theoretical model offers a more direct way to illustrate impact response patterns than simulations, acting as an effective complement and providing key quantitative references for engineering practice.

More importantly, the aforementioned research and conclusions hold significant reference value for de-icing overhead transmission lines. The structure of overhead transmission lines is similar to that of guy wires. During de-icing operations, they are similarly subjected to external impacts from de-icing rods. The patterns revealed in this study regarding how parameters such as ground inclination angle, prestress and length influence impact response can directly provide theoretical support for ground wire de-icing. For instance, by adjusting the suspension angle, pretension and span length of ground wires, the mechanical response characteristics during de-icing can be optimized. This enhances de-icing efficiency while reducing the risk of excessive deformation or breakage of ground wires caused by impact. Consequently, it offers quantitative references for the optimized design of ground wire de-icing solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.-G.Y., J.-G.Y. and L.-Y.L.; methodology, J.-G.Y., B.T. and L.-Y.L.; software, B.T. and W.-G.Y.; validation, S.L. and W.-G.Y.; formal analysis, S.L., C.-G.Z. and W.-G.Y.; investigation, J.-G.Y., S.L. and L.-Y.L.; resources, J.-G.Y., L.-Y.L. and W.-G.Y.; data curation, B.T., W.-G.Y. and S.-H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, B.T. and W.-G.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.-G.Y., C.-G.Z., W.-G.Y. and S.-H.Z.; visualization, C.-G.Z.; supervision, L.-Y.L.; project administration, J.-G.Y.and L.-Y.L.; funding acquisition, J.-G.Y., C.-G.Z. and L.-Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from the scientific and technological project (No. 529500250001) funded by Science and Technology Project of State Grid Power Space Technology Co., Ltd., which has provided essential financial and technical support for the completion of this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Jin-Gang Yang, Shuai Li, Chen-Guang Zhou and Liu-Yi Li were employed by the company State Grid Electric Power Space Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- China Electricity Council (CEC). Annual Development Report of China’s Electric Power Industry 2025; China Electric Power Press: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Yin, H.; Xia, L.; Wan, H.; Kalungi, M.P.; Zhu, A. Study of the Static Performance of Guyed Towers in High-Voltage Transmission Lines. Buildings 2024, 14, 3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.F.; Huang, Y.; Cai, J.L.; Chen, Z.F. A Numerical Analysis on the Wind-Resistance Strengthening with Guy Wires for Distribution Lines. Adv. Eng. 2017, 100, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Jiang, F.; Jiang, H.; Jiang, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Xiong, J.; Wu, T. Dynamic responses of 500-kV transmission line towers under impact force of rockfall in a mountainous area. Front. Mech. Eng. 2022, 8, 927263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, A.Y.; El Damatty, A.A. Behaviour of guyed transmission line structures under downburst wind loading. Wind. Struct. 2007, 10, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, T.B.; Kaminski, J., Jr. Dynamic response due to cable rupture in a transmission lines guyed towers. Procedia Eng. 2017, 199, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DL/T 5486-2020; Technical Specification for Design of Tower and Pole Structures of Overhead Transmission Lines. China Electric Power Planning & Engineering Institute: Beijing, China; China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Judge, R.; Yang, Z.; Jones, S.; Beattie, G.; Horsfall, I. Spiral strand cables subjected to high velocity fragment impact. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2017, 107, 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.J.; Ding, Z.; Sun, C.P.; Zhang, L.M. Finite element analysis of cross-sectional stress and failure modes of steel strands. Chin. Sci. Pap. 2018, 13, 2623–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, M.L.; Nafianto, R.; Nugraha, A.D.; Wiranata, A.; Supriyanto, E.; Nugroho, G.; Muflikhun, M.A. Advanced FEA simulation of GFRP and CFRP responses to low velocity impact: Exploring impactor diameter variations and damage mechanisms. Compos. Part C Open Access 2024, 15, 100541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.J.; Wang, X.L.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.L.; Yao, Y.; Chu, Y.P. Experimental study on dynamic response of wire rope under lateral impact load. J. Vib. Meas. Diagn. 2023, 43, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, H.M. Cable Structures; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.X. Nonlinear Calculation Theory of Cable Structures; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Pang, Z.; He, J.; Guo, J.; Zhao, W.; Du, Z.; Zhu, Z.H. Tensile experiment based nonlinear tether element model for tethered space net. Acta Astronaut. 2025, 228, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Liu, B.; Kang, L.; Fan, W.; Zhao, D.; Wang, T.; He, L.; Xie, J. Numerically efficient analysis of FRP confined CFST members under lateral low-velocity impact loading. Front. Mater. 2024, 11, 1435059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.G.; Wang, G.; Song, X.D.; Deng, X.H.; Zhao, K. Configuration analysis and tension calculation of catenary under vertical concentrated load. Chin. J. Comput. Mech. 2020, 37, 431–438. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.A.; Liu, Z.H. Configuration determination method of suspended cable structure under concentrated force. Spec. Purpose Veh. 2023, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.D.; Deng, X.H.; Jin, X.; Guo, X.G.; Liu, M.L. Horizontal catenary configuration and tension calculation subjected to a vertical concentrated forced as well as test verification. J. Comput. Mech. 2019, 36, 255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Tang, X.Z.; Huang, W. Response Analysis and Simplified Calculation of Impact Force of Transmission Tower in Mountain Area under Rolling Stone Impact. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2022, 22, 12440–12448. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.