Abstract

Stainless steels are commonly used in coastal structures and in seawater desalination and treatment systems, so understanding their corrosion behaviour under different salinity conditions is important to ensure the durability and reliability of the material. In this study, the behaviour of AISI 304L, AISI 316L, and 2205 duplex stainless steels (DSS) was tested in three media with different salinities: brackish water (BSW), seawater (SW), and concentrated seawater bittern (CSW). Testing was conducted using classical electrochemical methods (open circuit potential, linear, and potentiodynamic polarization) supplemented by surface analyses (optical microscopy, SEM/EDS, and optical profilometry). Corrosion resistance increased in the order AISI 304L < AISI 316L < 2205 DSS. Duplex steel 2205 performed best in all media: it exhibited the most positive open circuit potential, the highest polarization resistance, the lowest corrosion current density, and the widest passive range. Unexpectedly, CSW showed improved corrosion resistance compared to SW, which is explained by the reduced chloride content characteristic of seawater bittern after NaCl crystallisation and the presence of magnesium, calcium, and sulphate ions that promote the formation of protective deposits on the metal surface. Pronounced pitting was observed on AISI 304L steel in seawater, while surface degradation in brackish and concentrated seawater was significantly less, and 2205 DSS remained almost unchanged. The results obtained can serve as guidelines for the design and selection of materials for equipment and structures in industries operating in aggressive marine and coastal environments, such as desalination plants, shipbuilding, and energy systems.

1. Introduction

Stainless steels are important engineering materials for marine and coastal applications. They are characterized by high mechanical strength, good ductility and toughness, wear resistance, good thermal and electrical properties, excellent weldability and resistance to corrosion in aggressive environments. They are widely used in oil and gas platforms, seawater pipelines, desalination plants and heat exchangers, where seawater (due to its high thermal conductivity and availability) serves as a natural and efficient cooling medium [1,2,3,4,5]. However, long-term exposure to seawater makes these materials susceptible to localized corrosion processes, including pitting corrosion, crevice corrosion, and microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC), which may occur even under passive conditions. Consequences include high maintenance costs and security risks [6,7,8,9,10].

Extensive research to date has primarily examined the corrosion behaviour of stainless steels in NaCl solutions and seawater with constant salinity. The main focus has been on chloride-induced pitting corrosion and repassivation [3,6,8,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. These studies have established the key role of chloride ions as aggressive species and highlighted the beneficial influence of alloying elements such as chromium, molybdenum, and nitrogen on the stability of the passive layer [15,16,17]. However, natural seawater is much more complex than NaCl solutions: in addition to chloride, it contains magnesium, calcium, potassium, sulphates and bicarbonates, as well as dissolved organic compounds and microorganisms [18,19,20,21,22]. The interaction of these components creates a dynamic electrochemical environment that cannot be fully simulated in the laboratory.

In real marine conditions, microbial communities, including sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) and marine biofouling organisms, can form biofilms that locally alter pH, oxygen concentration, and redox potential near the metal surface, thereby strongly influencing corrosion processes [10,22,23,24]. These biofilms can have a dual effect: they may inhibit corrosion by forming a physical barrier or accelerate localized attack by producing corrosive metabolites, such as hydrogen sulphide (H2S) and organic acids [24]. Despite their recognised importance, the combined effects of organic and inorganic constituents of seawater on corrosion kinetics remain poorly understood.

Although numerous studies of stainless steels in seawater have been conducted, most assume a constant salinity level (approximately 3.5% NaCl equivalent), overlooking the natural variability of marine environments. However, salinity can vary greatly in real systems, from brackish waters (low chloride content) to concentrated brines (post-evaporation seawater), each with distinct ionic balances and biological activity [25,26,27]. This variability is particularly relevant for offshore structures and desalination plants, where components are often simultaneously exposed to seawater, brackish inflows, and concentrated outflows. Changes in salinity affect not only the activity of chloride ions, but also the concentrations of Mg2+, Ca2+, and SO42−, which can form surface deposits (e.g., Mg(OH)2, CaSO4) or alter the conductivity and composition of the passive layer [28,29].

Under such conditions, different stainless steel grades commonly used in marine and coastal engineering are exposed to non-uniform and dynamically changing salinity levels, making material selection and corrosion assessment under variable seawater compositions particularly relevant for real service environments.

Research on duplex stainless steels (DSS) in natural seawater environments remains relatively limited compared to that on austenitic grades. Although DSS alloys, such as 2205, offer superior resistance to pitting and stress corrosion cracking due to their two-phase microstructure, there are few systematic studies assessing their performance in real seawater of varying salinity and composition [30,31,32,33,34]. Given their increasing use in offshore pipelines, subsea structures, and seawater-cooled heat exchangers, understanding how salinity, biofilm formation, and organic species jointly influence their corrosion behaviour is of both scientific and industrial significance.

This work aims to examine the corrosion behaviour of AISI 304L, AISI 316L, and 2205 DSS steels in seawater of different salinities: brackish (BSW), natural (SW), and concentrated (CSW, seawater bittern). The research was conducted by combining classical electrochemical methods, open circuit potential (EOC), linear and potentiodynamic polarisation (LP and PD), with advanced surface analyses (optical microscopy, SEM/EDS, and 3D profilometry). This approach linked electrochemical data with surface morphology and chemical composition, enabling an understanding of corrosion and passivation processes under real marine conditions.

The novelty of this research lies in the systematic assessment of the behaviour of stainless steels in marine environments with varying salinity levels (brackish water, natural seawater, and seawater bittern), an aspect largely neglected in corrosion research to date. While numerous studies have focused mainly on synthetic chloride solutions and natural seawater of constant salinity, the impact of changing salinity in natural seawater on the corrosion of stainless steels remains insufficiently investigated. This knowledge gap is particularly pronounced for duplex stainless steels, despite their increasing use in key marine infrastructure. The unexpectedly improved resistance in CSW highlights the important role of ion-induced surface deposits in stabilising the surface (metal/environment phase boundaries) and provides mechanistic insight crucial for material selection and durability assessment in coastal structures, desalination plants, and heat exchange systems exposed to variable salinity conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

Corrosion investigations were conducted on two austenitic stainless steels, AISI 304L and AISI 316L, and one duplex stainless steel, 2205 DSS. Their nominal chemical compositions are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the investigated stainless steels (wt.%).

The test materials, manufactured by Ronsco Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China), were supplied as cylindrical bars, 15 cm in length and 6 mm in diameter. The steels were supplied in accordance with standard AISI specifications and are typically delivered in the solution-annealed condition for corrosion-resistant applications. Each bar was sectioned into 1.5 cm long cylinders, which were subsequently used to prepare the working electrodes. Electrical contact was established by mechanically fixing an insulated copper wire to one end of the cylinder via a threaded joint. All surfaces, except for one circular area of 0.5 cm2, were insulated with epoxy resin (Presi, Eybens, France). The exposed area served as the active surface in contact with the electrolyte during testing.

Before each electrochemical experiment, the electrode surfaces underwent mechanical and chemical pretreatment. Mechanical preparation was performed using a Metkon Forcipol 1V polishing unit (Metkon, Bursa, Turkey). The samples were ground under water with SiC papers of increasing fineness (P180 to P2000) and then polished with a 0.3 µm alumina suspension (Presi, France) to achieve a mirror-like finish. The electrodes were then ultrasonically degreased in ethanol for 5 min and rinsed with deionised water to remove surface contaminants.

Electrochemical measurements were conducted in three natural aqueous media with different salinity levels:

- Brackish seawater (BSW), collected at the mouth of the Jadro River in Solin (Croatia);

- Seawater (SW), sampled at Stobreč, near Split (Croatia);

- Seawater bittern (concentrated seawater, CSW), obtained from the Ramova saltworks (Krvavica–Makarska, Croatia) following NaCl harvesting. CSW, also known as bittern, is the residual solution remaining after salt crystallisation and is characterised by high ionic strength and a marked enrichment in Mg2+, Ca2+, and SO42− ions relative to Na+ and Cl− [20].

The physical parameters of the electrolytes were determined using a YSI PRO 1030 multiparameter probe (Xylem Inc., Yellow Springs, OH, USA) and presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Physical characteristics of the electrolytes. The ionic composition of seawater and seawater bittern has been extensively reported in the literature [20]; the parameters listed here are intended to provide a general physical characterization of the test media rather than a detailed ionic analysis.

The dilution was used exclusively for physicochemical measurements, as the undiluted CSW exceeded the measurement range of the multiparameter probe. All electrochemical corrosion measurements were carried out in undiluted CSW.

Salinity represents the total mass of dissolved salts (g/kg), predominantly Na+, Cl−, SO42−, Mg2+, Ca2+, and K+. The total dissolved solids (TDS) value expresses the combined concentration of inorganic and organic substances (mg/L or ‰). In seawater, salinity and TDS are numerically comparable because dissolved salts constitute nearly the entire solid fraction.

All electrochemical measurements were performed in a 200 mL double-walled glass electrochemical cell equipped with a Pt-mesh counter electrode and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference. The electrolyte temperature was maintained at 24 ± 1 °C using a Huber Kiss thermostatic bath (Huber, Offenburg, Germany) to ensure reproducibility. The experimental setup was connected to a PAR 273A potentiostat/galvanostat (Princeton Applied Research, Oak Ridge, TN, USA). The following electrochemical procedures were conducted sequentially for each sample:

- Open-circuit potential (EOC) was monitored for 60 min, with measurements recorded every 15 s;

- Linear polarisation (LP) in the range of ±20 mV vs. EOC, at a scan rate of 0.2 mV s−1. For clarity, the potential range is defined relative to EOC; therefore, when EOC is negative for all samples (vs. SCE), the LP scan may still fall within a negative absolute potential window. The applied potential sweep in this narrow range yielded a linear relationship between current density and potential for all tested materials and electrolytes. The polarization resistance (Rp) was determined from the slope of this linear region (ΔE/Δi), where the current was expressed as current density normalized to the exposed geometric electrode area of 0.50 cm2. Accordingly, Rp values are reported in units of kΩ·cm2. All numerical Rp values were obtained directly from the instrument software.

- Potentiodynamic polarization (PD) from −0.4 V vs. EOC to +0.7 V at a scan rate of 1 mV s−1. For 2205 DSS, the anodic potential limit was extended to +1.2 V vs. SCE due to its significantly higher resistance to localized corrosion, ensuring that to ensure that the depassivation region could be reached and properly characterized.

All electrochemical measurements, including open circuit potential, linear, and potentiodynamic polarization measurements, were repeated several times to ensure reproducibility under short-term corrosion conditions. Measurements were initiated after 60 min of open-circuit potential stabilization. After PD measurement, the electrodes were rinsed with deionized water and dried in a desiccator. Surface characterization was then performed using

- Optical microscopy (MXFMS-BD, Ningbo Sunny Instruments Co., Ningbo, China),

- Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) (Quattro ESEM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and

- Optical profilometry (Profilm 3D, KLA Corporation, Milpitas, CA, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Electrochemical Behaviour

The corrosion behaviour of stainless steels AISI 304L, AISI 316L, and 2205 DSS was examined in aqueous environments of different salinity—BSW, SW, CSW—by monitoring the open-circuit potential (EOC) and performing linear (LP) and potentiodynamic (PD) polarisation tests. Surface degradation of the tested electrodes was evaluated using optical microscopy, profilometry, and SEM/EDS analysis.

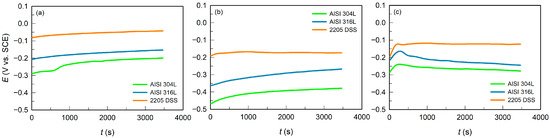

Figure 1 shows the time evolution of the EOC for each stainless steel sample in the three test media. The EOC represents a characteristic potential value for a given electrochemical system and is influenced by anodic and cathodic processes occurring at the electrode/electrolyte interface.

Figure 1.

Variation in open circuit potential for AISI 304L, AISI 316L, and 2205 DSS in: (a) BSW, (b) SW, and (c) CSW.

All steels showed a similar trend in EOC behaviour across the different media. Immediately after immersion, the potential of each specimen shifted towards more positive values, then stabilised at nearly constant levels (Table 3). The positive shift in potential is associated with the spontaneous formation of a passive oxide film on the steel surface, which reduces electrochemical activity and slows corrosion reactions.

Table 3.

Open circuit potential (EOC) values of AISI 304L, AISI 316L, and 2205 DSS after 60 min of stabilisation in media of different salinity.

Regardless of the salinity level of the test solutions, the evolution of EOC showed a consistent trend among all examined alloys, following the order AISI 304L < AISI 316L < 2205 DSS. This sequence directly reflects the influence of alloying elements on corrosion resistance. Molybdenum in AISI 316L contributes to improved resistance to localized corrosion, while the combined and increased content of chromium and molybdenum in 2205 DSS results in the most positive EOC values and the highest stability in chloride media.

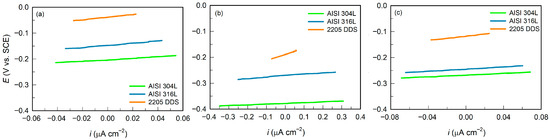

The corrosion stability of the steel samples was further tested using the LP method to determine the polarisation resistance (Rp). The results are shown in Figure 2, and the corresponding Rp values are given in Table 4.

Figure 2.

Linear polarisation curves of AISI 304L, AISI 316L, and 2205 DSS in: (a) BSW, (b) SW, and (c) CSW.

Table 4.

Polarisation resistance of AISI 304L, AISI 316L, and 2205 DSS determined by the LP method in electrolytes of varying salinity.

In all tested cases, a linear current density–potential (i–E) dependence was observed within the applied polarization range, confirming stable system behaviour in the linear polarization domain. The polarization resistance (Rp) values reported in Table 4 were derived from the slope of the linear region of the LP curves, as described in the Experimental section. Higher Rp values indicate improved corrosion resistance. Based on the obtained results obtained, Rp increased in the following order: SW < CSW < BSW, with 205 DSS exhibiting the highest Rp values in all investigated environments.

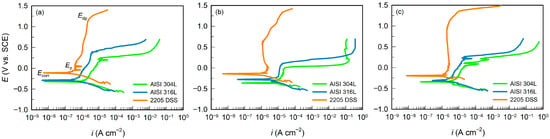

The anodic behaviour of stainless steels was studied using the PD technique. Measurements were performed over a wide potential range, and the resulting curves (Figure 3) provide detailed insight into the active and passive behaviour of the material in the tested environments.

Figure 3.

Potentiodynamic polarization curves for AISI 304L, AISI 316L, and 2205 DSS in: (a) BSW, (b) SW, and (c) CSW.

The analysis of PD curves begins by determining the corrosion potential (Ecorr), defined as the potential at which anodic and cathodic currents are equal. This characterises the thermodynamic tendency of a material to corrode, rather than the energy required to initiate corrosion [35]. A more positive Ecorr indicates a lower tendency to corrode. At potentials more negative than Ecorr (cathodic region), the PD curve shows the reaction of hydrogen evolution or oxygen reduction.

However, the most important data are obtained by analysing the anodic part of the PD curve, at potentials more positive than Ecorr. As the potential gradually increases in the positive direction, the sample acts as an anode, either causing metal dissolution or forming a protective oxide film. In the anodic part of the PD curve, three characteristic regions are observed: active, passive, and depassivation regions.

The characteristic shape of anodic polarisation curves and the definition of the active, passive, and depassivation regions are well established in electrochemical corrosion literature and have been extensively described for stainless steels in aqueous and marine environments [36,37].

- In the active potential region, the metal dissolves rapidly, and the current increases sharply with increasing potential.

- In an aqueous electrolyte solution, metal ions react with hydroxide ions (OH−) formed by water ionisation. Metal hydroxides form and deposit on the metal surface, creating a protective layer that slows further dissolution. Over time these metal hydroxides dehydrate and form more stable oxides, further enhancing surface protection.

- By anodic polarisation, the passivation potential (Ep) is defined as the potential at which the limiting passivation current (ip) is reached. At this point, the rate of metal dissolution equals the rate of protective oxide film formation. With further increase in potential, the metal dissolution rate is significantly slowed by the formation of the oxide film. Eventually, the metal surface becomes fully covered by the oxide film and the current stabilises, becoming less dependent on changes in potential. On the polarisation curve, this appears as a “current plateau” or a slow increase in current [38]. The independence (or slow growth) of current despite a constant increase in potential is associated with the thickening of the oxide film under the influence of strong electric fields. Depending on experimental conditions–such as steel type, water salinity, and so on–this region extends to different anodic potentials.

- Upon further increase in the anodic potential, the depassivation potential or pitting potential (Edp), defined as the potential at which breakdown of the passive film and stable pit initiation occur. In brackish seawater, the values found were: 0.243 V for AISI 304L, 0.375 V for AISI 316L, and for 2205 DSS it is much higher, reaching 1.185 V. At Edp the protective oxide film breaks down and the metal locally dissolves, which is manifested on the potentiodynamic curve as a sharp rise in anodic current. The difference between the depassivation potential and the corrosion potential, ΔE = Edp − Ecorr, indicates the material’s resistance to pitting corrosion [37,38]. The larger this difference, the lower the tendency of the material to local corrosion.

By analysing the PD curves, the following were determined: corrosion current (icorr), passivation current (ip), characteristic potentials Ecorr, Ep, Edp, and the potential difference ΔE = Edp − Ecorr. The obtained values are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Corrosion parameters for AISI 304L, AISI 316L, and 2205 DSS in media of different salinity.

The results confirm that 2205 DSS exhibits the lowest corrosion current density and the most positive Ecorr values in all electrolytes, as well as the widest passive region and the highest Edp, demonstrating its outstanding resistance to localised corrosion. Overall, icorr and ip decrease, while Ecorr, Ep, and Edp increase in the order AISI 304L < AISI 316L < 2205 DSS, matching the expected trend based on alloy composition and microstructure.

The observed trends are fully consistent with literature data describing the beneficial effects of alloying elements on corrosion resistance [1,2,3,4,12,15,16,17,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]:

- Chromium (Cr) ensures passivation above 12 wt.% and, at higher levels, produces a thicker and more stable oxide film [12,17,39,40,41,42].

- Molybdenum (Mo) enhances resistance to pitting by stabilising the passive layer and inhibiting pit propagation [15,16,17,43,44,45,46].

The corrosion resistance order AISI 304L < AISI 316L < 2205 DSS is therefore in complete agreement with theoretical expectations. Interestingly, corrosion resistance also depends on the overall ionic composition of seawater, not only on chloride concentration. Although CSW has higher salinity, its reduced Cl− and Na+ content and increased Mg2+, Ca2+, and SO42− levels contribute to the formation of protective surface deposits, which enhance passivity [19,28,29]. This explains the unexpectedly improved corrosion behaviour of all steels, especially 2205 DSS, in CSW compared with natural seawater.

These findings emphasise that salinity should not be interpreted solely as a function of chloride concentration, but rather as a complex variable reflecting the combined effects of all dissolved species, including ions and organic compounds, which can stabilise the passive layer and inhibit metal dissolution.

3.2. Surface Characterisation (Microscopy and Profilometry)

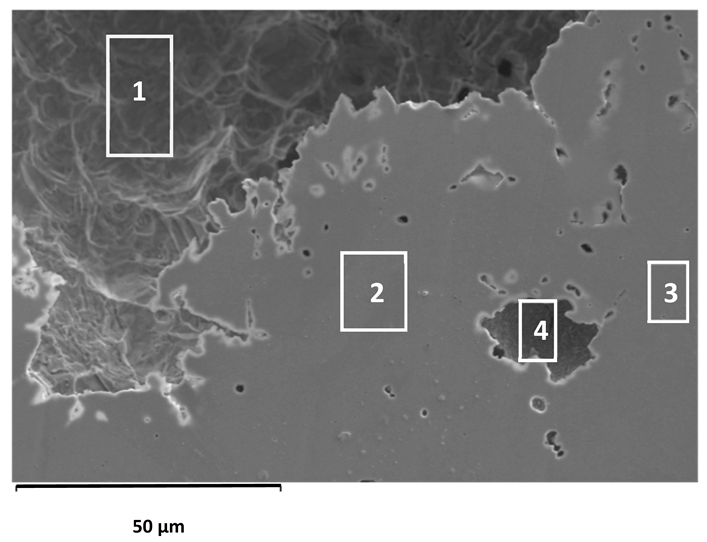

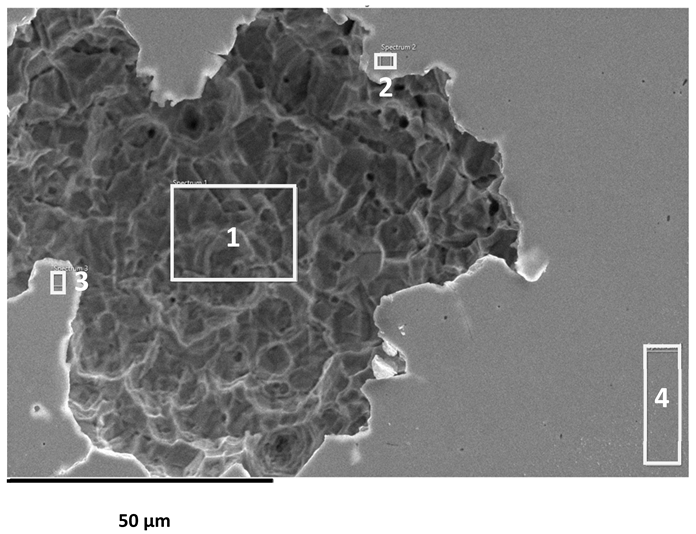

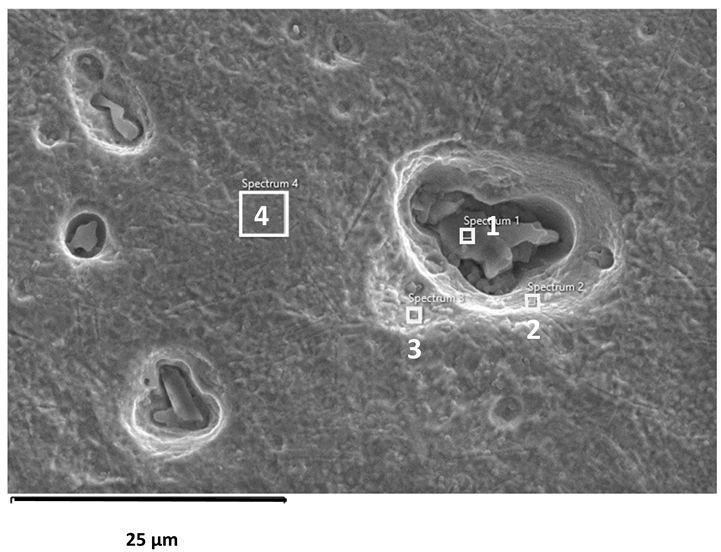

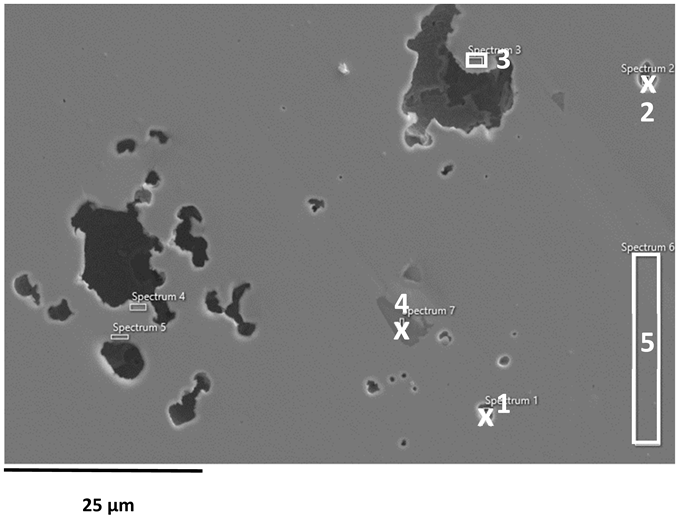

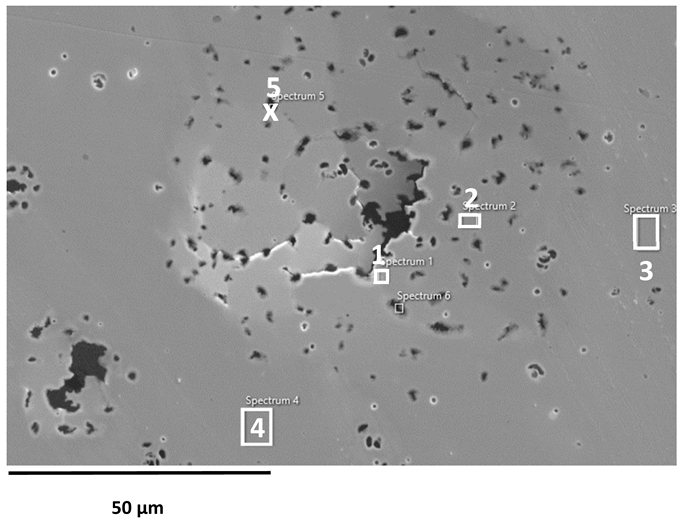

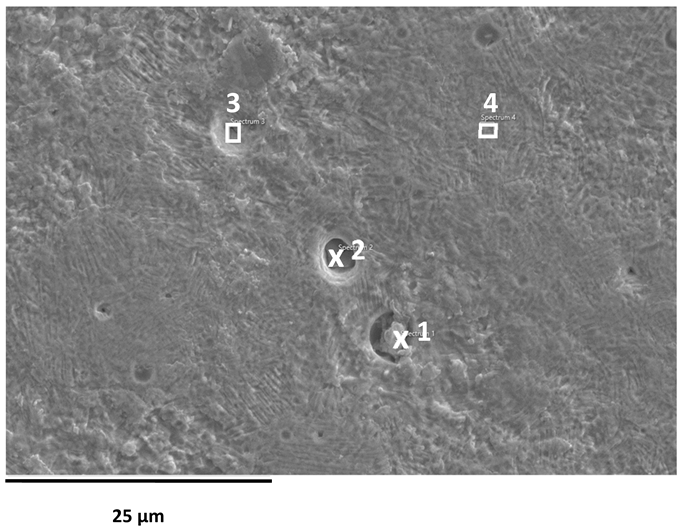

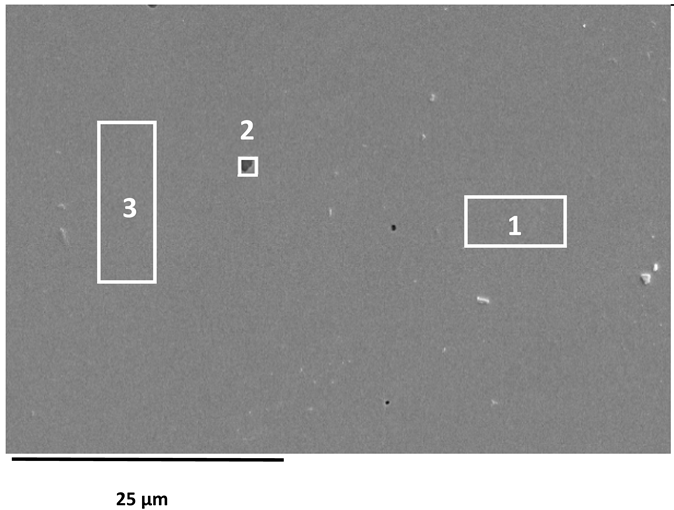

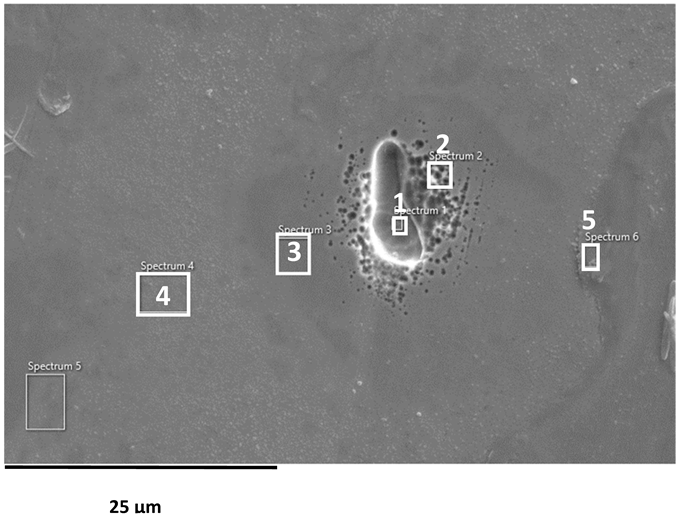

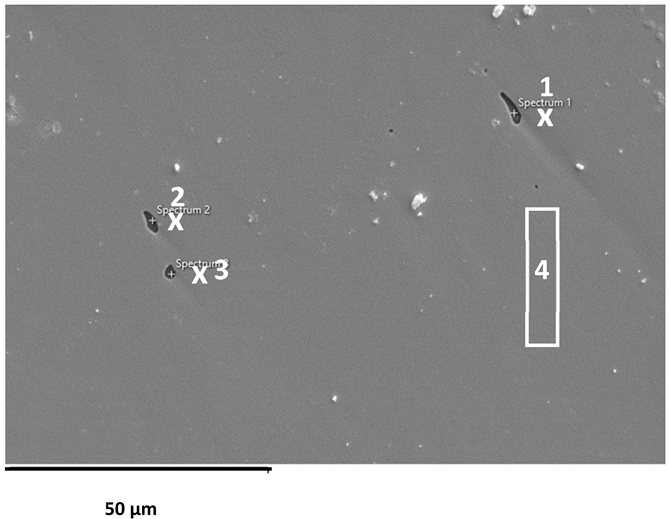

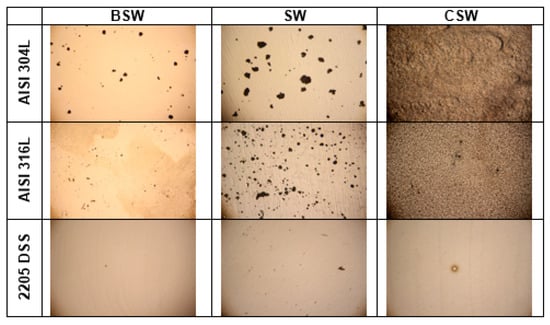

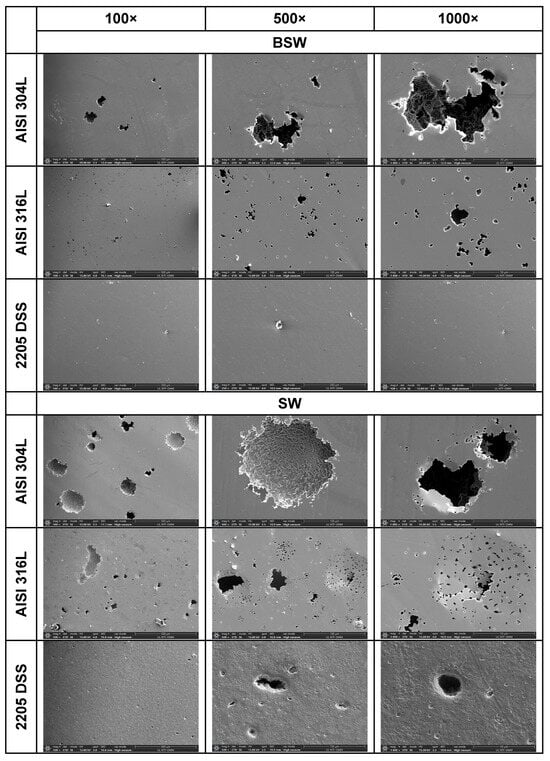

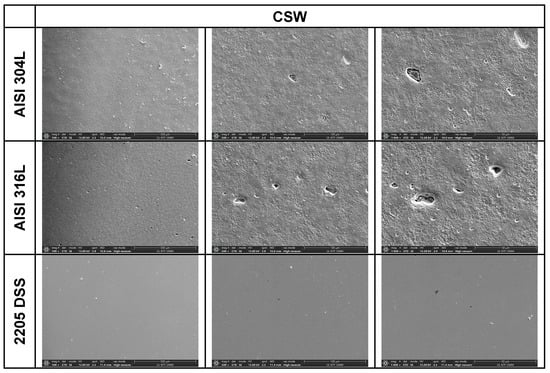

After reaching the upper limit of anodic polarisation (0.7 V for AISI 304L and AISI 316L, and 1.2 V for 2205 DSS), the electrode surfaces were examined using optical microscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at various magnifications. Representative micrographs are shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Optical microscope images of the AISI 304L, AISI 316L, and 2205 DSS surfaces after anodic polarisation in seawater of varying salinity (100×).

Figure 5.

SEM images of the AISI 304L, AISI 316L, and 2205 DSS surfaces after anodic polarisation in seawater of different salinities.

Anodic polarisation resulted in distinct surface modifications across the studied alloys. Both AISI 304L and AISI 316L exhibited localised corrosion damage in the form of small but relatively deep pits, with AISI 316L showing less severe attack. In contrast, the duplex 2205 DSS alloy displayed no significant degradation.

A clear correlation between surface degradation, alloy type, and medium salinity was identified. Samples exposed to BSW showed only minor localised features, consistent with a stable passive film in the low-chloride environment. In natural SW, both AISI 304L and AISI 316L exhibited pronounced pitting, consistent with the well-documented chloride sensitivity of austenitic stainless steels [3,6,8,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,28,29,30,31,47,48]. Interestingly, exposure to CSW resulted in fewer visible corrosion defects. This behaviour reflects the reduced concentrations of Na+ and Cl− ions in the CSW by-product of salt production after NaCl precipitation–thus reducing the availability of the most aggressive species responsible for passive-film breakdown. It should be noted that the tests were conducted in natural waters, where the presence of organic matter and microorganisms was not controlled, reflecting realistic marine exposure conditions.

Furthermore, CSW-exposed surfaces often displayed deposits that partially obscured the underlying corrosion morphology. These deposits are likely composed of slightly soluble salts such as Mg(OH)2 and CaSO4, which can act as a physical barrier and retard further corrosion propagation [19,28,29]. SEM imaging revealed a more detailed view of these deposits and confirmed the presence of distinct pitting primarily on SW-exposed surfaces.

It should be noted that the thickness and internal structure of the protective surface films were not quantitatively determined in the present study. Such characterization would require advanced surface-sensitive techniques, such as X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy or transmission electron microscopy, which were beyond the scope of this work. The protective role of the surface deposits is therefore inferred from the consistent trends observed in electrochemical behaviour, SEM/EDS analysis, and surface topography obtained by optical profilometry.

Within this context, the improved corrosion resistance observed in CSW can be explained by the synergistic action of Mg2+, Ca2+, and SO42− ions. High ionic strength and reduced chloride activity favour CaSO4 precipitation, while local alkalisation at the metal–electrolyte interface promotes Mg(OH)2 formation. The coexistence of these deposits is consistent with thermodynamic tendencies reported for concentrated brines and is kinetically supported by suppressed chloride-induced localized corrosion, resulting in a composite protective barrier [15,17,28,29].

It should be noted that EDS provides semi-quantitative elemental information and does not allow unambiguous phase identification due to peak overlap and the influence of surface morphology. Therefore, corrosion products discussed in this study are considered as probable phases inferred from the combined analysis of elemental composition, electrochemical behaviour, surface morphology, and relevant literature.

EDS analysis of corroded stainless steel surfaces revealed a complex elemental composition, including both alloying elements and those originating from the seawater environment (Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8). In addition to the primary alloy elements (Fe, Cr, Ni, Mn, Si, Mo, Cu), significant amounts of oxygen and smaller amounts of sodium, chlorine, magnesium, calcium, and sulphur were detected. The increased oxygen content confirms the presence of a passive oxide film, predominantly composed of chromium and iron oxides, formed during exposure to the electrolyte. This phenomenon is especially pronounced in samples exposed to BSW, indicating the formation of a more stable and resistant passive layer in moderately aggressive, yet still oxidising, conditions [25,47]. The highest oxygen content was recorded for 2205 DSS, which is consistent with electrochemical test results confirming its increased corrosion resistance in BSW media.

Table 6.

EDS-analysis of AISI 304L steel surfaces after anodic polarisation in seawater of different salinity levels. “–” indicates elements not detected or present below the detection limit.

Table 7.

EDS-analysis of AISI 316L steel surfaces after anodic polarisation in seawater of different salinity levels. “–” indicates elements not detected or present below the detection limit.

Table 8.

EDS-analysis of 2205 DSS steel surfaces after anodic polarisation in seawater of different salinity levels. “–” indicates elements not detected or present below the detection limit.

A chlorine signal appears in all EDS spectra, indicating that chloride ions from seawater adsorb onto or penetrate the surface films. Chloride ions are known to be the most aggressive species, causing pitting corrosion in stainless steels. Advanced microscopic studies have directly confirmed that chloride ions can penetrate the nanometre-thin passive layer and concentrate at the interface between the metal and the film, impairing its protective properties [48,49]. Accordingly, AISI 304L steel, which, according to electrochemical results, shows the lowest resistance to pitting corrosion in SW, has a higher surface chlorine content than molybdenum-enriched 2205 DSS, which shows a surface with higher oxygen content and reduced chlorine content, confirming its higher resistance to pitting corrosion.

The EDS results for the CSW-exposed samples showed significant enrichment in Mg, Ca, S, and O, providing valuable insight into the altered corrosion mechanisms operating in this highly saline yet chloride-reduced environment. The presence of Ca and S strongly indicates the precipitation of calcium sulphate (CaSO4), a thermodynamically favoured phase in sulphate-rich bittern solutions. This finding aligns with previous studies reporting CaSO4 formation on steel surfaces under similar ionic conditions [28,29].

In contrast, magnesium can form several compounds; however, the low solubility of magnesium hydroxide (Mg(OH)2) under alkaline interfacial conditions and its frequent observation in high-salinity media make it the most probable corrosion product [19]. Although hydrogen cannot be detected by EDS, the Mg–O signal is consistent with literature-reported Mg(OH)2 formation [19,28]. The presence of MgSO4 cannot be excluded, but due to its high solubility, significant surface precipitation is unlikely [29]. Overall, the EDS findings confirm the coexistence of protective CaSO4 deposits and Mg-based hydroxide films, which jointly diminish chloride activity, enhance passive film stability, and suppress deep pitting. This behaviour explains the improved electrochemical stability observed in CSW relative to SW, and highlights the key role of polyvalent ions (Mg2+, Ca2+, SO42−) in modifying corrosion pathways. Instead of the expected localised corrosion with deep pits observed in SW, the corrosion in CSW becomes more uniform, with shallower and smaller surface damage [34,49].

The behaviour described above was further supported by surface microscopy and profilometry (see below): AISI 304L developed only broad, shallow corrosion grooves in CSW, unlike the deep pits formed in natural seawater. AISI 316L exhibited markedly reduced pitting, while duplex stainless steel 2205 remained essentially corrosion-free under the same conditions. EDS analysis confirmed Ca- and Mg-rich deposits on surfaces exposed to CSW, directly reinforcing the interpretation of a shifted corrosion mechanism.

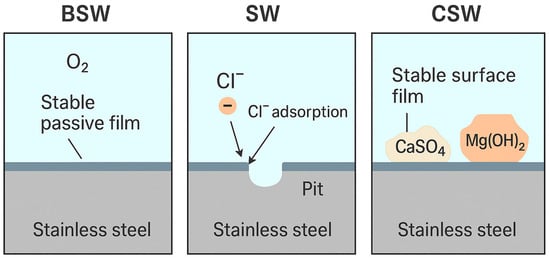

Overall, the EDS findings provide a crucial link between electrochemical measurements and surface morphology, capturing the interplay between oxidation, chloride-induced attack, and deposit formation–each influenced by both the electrolyte composition and alloy microstructure. To illustrate the proposed corrosion mechanisms across different natural seawater environments, a schematic comparison of surface processes in BSW, SW, and CSW is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the dominant corrosion mechanisms in BSW, SW, and CSW. Figure prepared with the assistance of AI-based graphical tools.

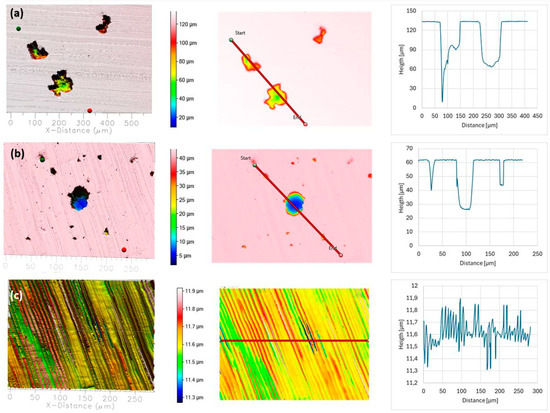

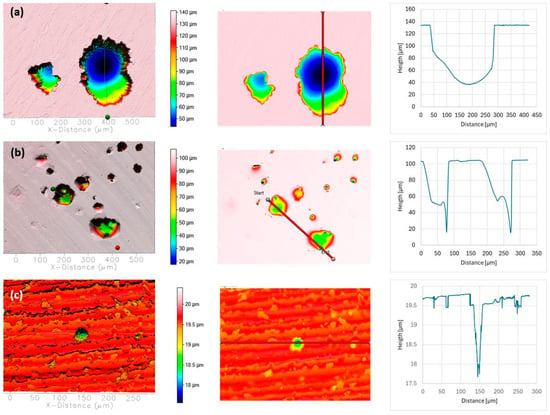

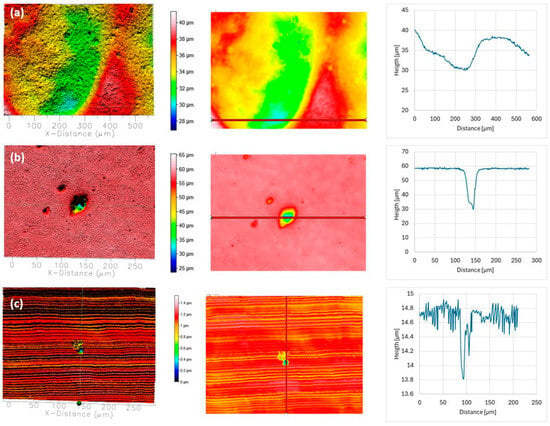

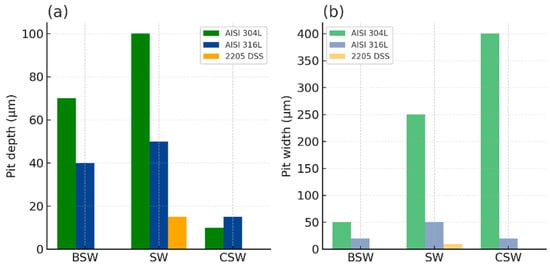

To further assess the effect of seawater salinity on corrosion damage, the post-polarisation surfaces were analysed using optical profilometry. Representative three-dimensional (3D) surface maps are shown in Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, and the corresponding defect dimensions are summarised in Figure 10 and Table 9.

Figure 7.

Surface topography of AISI 304L (a), AISI 316L (b), and 2205 DSS (c) after potentiodynamic polarisation in BSW. Pit depth and width were determined along the red line.

Figure 8.

Surface topography of AISI 304L (a), AISI 316L (b), and 2205 DSS (c) after potentiodynamic polarisation in SW. Pit depth and width were determined along the red line.

Figure 9.

Surface topography of AISI 304L (a), AISI 316L (b), and 2205 DSS (c) after potentiodynamic polarisation in CSW. Pit depth and width were determined along the red line.

Figure 10.

Average pit depth (a) and width (b) for AISI 304L, AISI 316L, and 2205 DSS in media of different salinity. Figure prepared with the assistance of AI-based graphical tools.

Table 9.

Selected quantitative parameters derived from the profilometry data.

In BSW, all alloys exhibited relatively mild surface alteration. AISI 304L developed moderate pits (maximum depth ≈ 70 µm, width ≈ 50 µm), while AISI 316L showed fewer and smaller defects (maximum depth ≈ 40 µm, width ≈ 20 µm). No measurable corrosion features were observed on duplex 2205 DSS.

In SW, the higher chloride concentration created a substantially more aggressive environment. AISI 304L exhibited deep and wide pits (up to ≈100 µm deep and ≈250 µm wide). AISI 316L also experienced localised breakdown, with typical pits ≈50 µm deep and ≈50 µm wide, and occasional defects reaching ≈120 µm depth. 2205 DSS again showed only shallow, isolated features (≈15 µm depth, ≈10 µm width).

In CSW, the overall high salinity combined with reduced chloride concentration produced atypical degradation patterns. Instead of classical pit morphology, AISI 304L developed broad, shallow grooves (≈10 µm deep and ≈400 µm wide), suggesting erosion-assisted or deposit-mediated degradation. AISI 316L exhibited minor irregularities (≈15 µm depth, ≈20 µm width), and 2205 DSS remained essentially unaffected.

The pit depth and width profiles highlight

- (i)

- the largest and widest pits for AISI 304L in SW;

- (ii)

- broad but shallow grooves for AISI 304L in CSW; and

- (iii)

- the minimal susceptibility of 2205 DSS, which remained effectively immune under all examined conditions.

In addition to characteristic defect dimensions, the surface roughness parameters Sa and Sq provide complementary quantitative insight into the severity and spatial distribution of surface degradation. The arithmetic mean surface roughness (Sa) reflects the average deviation of surface heights from the reference plane, while the root mean square roughness (Sq), due to its quadratic averaging, is more sensitive to pronounced surface features such as deep pits or grooves. Accordingly, higher Sa and Sq values indicate more severe and localized surface damage, whereas low roughness values are characteristic of shallow, uniform or deposit-covered degradation. In this study, these parameters are useful for distinguishing between classical chloride-induced pitting corrosion in natural SW and the broader, shallow groove-type degradation observed in CSW.

The roughness parameters (Sa and Sq) and maximum pit depths reported in Table 9 are fully consistent with the electrochemical results and surface observations discussed above. Higher roughness values and deeper defects in natural seawater reflect pronounced chloride-induced localized corrosion, while the markedly lower Sa and Sq values in concentrated seawater bittern confirm the transition towards shallower, deposit-mediated surface degradation. The consistently minimal roughness of duplex 2205 DSS across all environments further corroborates its superior corrosion resistance.

These results reinforce the influence of both alloy chemistry and electrolyte composition on corrosion resistance, with duplex 2205 DSS providing superior protection in seawater environments. For marine applications–including offshore structures and heat-exchange systems–duplex 2205 DSS is recommended, while AISI 304L requires additional corrosion protection.

Overall, the combined insights from optical and SEM imaging, EDS surface chemistry, and quantitative profilometry form a coherent mechanistic narrative that directly supports the electrochemical measurements. Localised corrosion in natural seawater is governed by aggressive chloride-induced depassivation, while in seawater bittern, the reduced chloride activity together with elevated Mg2+, Ca2+, and SO42− concentrations promotes the formation of adherent surface deposits that stabilise the passive film.

This salinity-driven shift in corrosion morphology—from deep, well-defined pitting in natural seawater to broad, shallow groove-type degradation in bittern environments–validates the observed ranking of alloy performance. Importantly, the near-immunity of duplex 2205 DSS across all investigated real seawater matrices represents a key novel contribution of this study and addresses a critical knowledge gap in understanding stainless steel durability under variable marine conditions.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the corrosion behaviour of AISI 304L, AISI 316L, and 2205 duplex stainless steel in natural seawater environments with different salinity levels, including brackish seawater, natural seawater, and concentrated seawater bittern. The corrosion resistance of the materials increased consistently in the order AISI 304L < AISI 316L < 2205 DSS, confirming the beneficial role of alloying elements such as chromium and molybdenum in stabilising the passive film and enhancing resistance to localized corrosion.

Natural seawater promoted the most severe pitting corrosion, particularly on AISI 304L, due to high chloride activity. In contrast, despite its high overall salinity, concentrated seawater bittern exhibited improved corrosion resistance compared to natural seawater. This unexpected behaviour is attributed to reduced chloride availability following NaCl precipitation and to the synergistic action of Mg2+, Ca2+, and SO42− ions, which promote the formation of protective CaSO4 and Mg(OH)2 surface deposits and suppress deep localized attack.

Surface characterisation by optical microscopy, SEM/EDS, and optical profilometry confirmed the electrochemical trends, revealing a transition from pronounced localised pitting in natural seawater to shallower and more uniform surface degradation in concentrated seawater bittern. Duplex stainless steel 2205 demonstrated superior performance in all tested environments, showing minimal surface degradation even under highly concentrated brine conditions.

The novelty of this work lies in the systematic assessment of stainless steel corrosion behaviour in real natural seawater systems characterised by variable salinity, an aspect largely neglected in previous studies focused on synthetic NaCl solutions or seawater of constant salinity. By linking electrochemical behaviour with realistic seawater chemistry and surface analyses, this study provides new insight into the combined influence of chloride depletion and multivalent ions on corrosion mechanisms.

From a practical perspective, the results indicate that 2205 duplex stainless steel is a robust material choice for marine and desalination applications where exposure to non-uniform and fluctuating salinity conditions is common in service. It should be noted that the experiments were conducted using natural waters collected from a specific geographic location and that the composition of seawater bittern may vary depending on source and season. Furthermore, organic matter and microbial activity were not controlled, reflecting realistic marine exposure conditions. This work represents a first phase of investigation focused on short-term electrochemical behaviour; long-term exposure effects will be addressed in future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G., L.V. and J.K.; methodology, S.G., M.Ć., L.V., A.N. and J.K.; software, L.V., A.N., J.K., A.N. and J.J.; validation, S.G., M.Ć., L.V., A.N., J.K. and J.J.; formal analysis, S.G., A.N. and J.K.; investigation, S.G., L.V., M.Ć., A.N. and J.K.; resources, L.V., A.N., J.K. and J.J.; data curation, S.G., M.Ć., L.V., A.N. and J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G., A.N. and J.K.; writing—review and editing, S.G., M.Ć., L.V., A.N., J.K. and J.J.; visualization, S.G., A.N. and J.K.; supervision, S.G., M.Ć., L.V., A.N., J.K. and J.J.; project administration, S.G.; funding acquisition, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Union under the NextGenerationEU instrument through the project ANTARES (IP-UNIST-28), implemented by the Ministry of Science, Education and Youth of the Republic of Croatia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Artificial intelligence (AI)-based language tools (ChatGPT-4–based model, OpenAI, accessed January–March 2025) were used for language refinement and text shaping in certain parts of the manuscript. The authors reviewed, verified, and take full responsibility for all content and interpretations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- McGuire, M.F. Stainless Steels for Design Engineers; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jessen, C.Q. Stainless Steel and Corrosion; Damstahl: Skanderborg, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kožuh, S.; Gojić, M.; Vrsalović, L.; Ivković, B. Corrosion failure and microstructure analysis of AISI 316L stainless steels for ship pipeline before and after welding. Kovove Mater. 2013, 51, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juraga, I.; Stojanović, I.; Ljubenkov, B. Experimental research of the duplex stainless steel welds in shipbuilding. Shipbuilding 2014, 62, 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Sarode, D.; Saharakar, U.; Ahire, H.H.; Darade, M.M.; Chougule, S.M.; Dalvi, S.A.; Kurhade, A.S. Corrosion-resistant materials for ocean structures: Innovations, mechanisms, and applications. Sustain. Mar. Struct. 2025, 7, 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.-P.; Tsai, K.-C.; Huang, J.-Y. Influence of chloride concentration on stress corrosion cracking and crevice corrosion of austenitic stainless steel in saline environments. Materials 2020, 13, 5640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo, B.; Lacalle, R.; Álvarez, J.A.; Cicero, S.; Moreno-Ventas, X. Analysis of unexpected leaks in AISI 316L stainless steel pipes used for water conduction in a port area. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudić, S.; Vrsalović, L.; Matošin, A.; Krolo, J.; Oguzie, E.E.; Nagode, A. Corrosion behavior of stainless steel in seawater in the presence of sulfide. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukelić, A.; Mihaljec, B.; Ivošević, Š. Marine environment effect on welded additively manufactured stainless steel AISI 316L. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakai, S.; Eno, N.; Mizukami, H.; Sunaba, T.; Miyanaga, K.; Miyano, Y. Microbiologically influenced corrosion of stainless steel independent of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 982047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.A.M.; Abd El Rehim, S.S.; Hamza, M.M. Corrosion behavior of some austenitic stainless steels in chloride environments. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2009, 115, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudić, S.; Kvrgić, D.; Vrsalović, L.; Gojić, M. Comparison of the corrosion behavior of AISI 304, AISI 316L and duplex steel in chloride solution. Zaštita Mater. 2018, 59, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loto, R.T.; Oladipupo, S.; Folarin, T.; Okosun, E. Impact of chloride concentrations on the electrochemical performance and corrosion resistance of austenitic and ferritic stainless steels in acidic chloride media. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, M.; Asnavandi, M.; Koshy, P.; Sorrell, C.C. Corrosion investigation of duplex stainless steels in chlorinated solutions. Steel Res. Int. 2015, 86, 1080–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, C.-O.A. The influence of nitrogen and molybdenum on passive films formed on austenoferritic stainless steel 2205 studied by AES and XPS. Corros. Sci. 1995, 37, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, V.; Marcus, P. Molybdenum effects on the stability of passive films unraveled at the nanometer and atomic scales. npj Mater. Degrad. 2024, 8, 8084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Paschalidou, E.-M.; Seyeux, A.; Zanna, S.; Maurice, V.; Marcus, P. Mechanisms of Cr and Mo enrichments in the passive oxide film on 316L austenitic stainless steel. Front. Mater. 2019, 6, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Wu, F.; Xia, J.; Huang, K.; Zhang, B.; Wu, J. A comparison study of crevice corrosion on stainless steels under biofouling and artificial configurations. npj Mater. Degrad. 2022, 6, 6754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loto, C.A. Calcareous deposits and effects on steel surfaces in seawater—A review and experimental study. Orient J. Chem. 2018, 34, 2332–2341. Available online: http://www.orientjchem.org/?p=50086 (accessed on 15 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Millero, F.; Feistel, R.; Wright, D.G.; McDougall, T.J. The composition of standard seawater and the definition of the reference-composition salinity scale. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2008, 55, 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donik, Č.; Kocijan, A. Comparison of the corrosion behaviour of austenitic stainless steel in seawater and in a 3.5% NaCl solution. Mater. Technol. 2014, 48, 937–942. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, H.; Fan, Y.; Xu, D. Microbially influenced corrosion of steel in marine environments: From mechanisms to prevention. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Mathivanan, K.; Wang, F.; Duan, J.; Hou, B. Advances in understanding biofilm-based marine microbial corrosion. Corros. Rev. 2025, 43, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Gong, L.; Chen, X.; Gadd, G.M.; Liu, D. Dual role of microorganisms in metal corrosion: A review of mechanisms of corrosion promotion and inhibition. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1552103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huttunen-Saarivirta, E.; Rajala, P.; Marja-aho, M.; Maukonen, J.; Sohlberg, E.; Carpén, L. Ennoblement, corrosion, and biofouling in brackish seawater: Comparison between six stainless steel grades. Bioelectrochemistry 2018, 120, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasnodebska-Ostrega, B.; Drwal, K.; Sadowska, M.; Bluszcz, D.; Miecznikowski, K. Corrosion process of stainless steel in natural brine as a source of chromium and iron—The need for routine analysis. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 28834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrsalović, L.; Gudić, S.; Talijančić, A.; Jakić, J.; Krolo, J.; Danaee, I. Corrosion behavior of Ti and Ti–6Al–4V alloy in brackish water, seawater, and seawater bittern. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2024, 5, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmad, M. Factors affecting scale formation in seawater environments—An experimental approach. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2008, 31, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Anezi, K.; Hilal, N. Scale formation in desalination plants: Effect of carbon dioxide solubility. Desalination 2007, 204, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, R.; Byrne, G.; Warburton, G. The corrosion of superduplex stainless steel in different types of seawater. In Proceedings of the CORROSION 2011, Dallas, TX, USA, 13–17 March 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Larché, N.; Thierry, D.; Debout, V.; Blanc, J.; Cassagne, T.; Peultier, J.; Johansson, E.; Taravel-Condat, C. Crevice corrosion of duplex stainless steels in natural and chlorinated seawater. Rev. Métallurgie 2011, 108, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucko, F.; Ringot, G.; Thierry, D.; Larché, N. Fatigue behavior of super duplex stainless steel exposed in natural seawater under cathodic protection. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 826189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, R.; Hebdon, S. The corrosion of cast duplex stainless steels in seawater and sour brines. Corrosion 2019, 75, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, E.; Li, H.; Yang, C.; Wang, J.; Xu, D.; Zhang, D.; Gu, T. Accelerated corrosion of 2304 duplex stainless steel by marine Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2018, 127, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Huang, J.; Lin, C.; Pan, C.; Chen, S.; Yang, T.; Lin, D.; Lin, H.; Jang, J. Anisotropic response of Ti–6Al–4V alloy fabricated by selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 682, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, W.S. An Introduction to Electrochemical Corrosion Testing for Practicing Engineers and Scientists; Pair O’ Docks Publications: Racine, WI, USA, 1994; pp. 65–67. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D.C. Electrochemical techniques—Simple tests for complex predictions in the chemical process industries. Corros. Rev. 1992, 10, 31–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.E.; Wright, G.A. Nucleation and growth of anodic oxide films on bismuth—Part I: Cyclic voltammetry. Electrochim. Acta 1976, 21, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brajković, T.; Juraga, I.; Šimunović, V. Influence of surface treatment on corrosion resistance of Cr–Ni steel. Eng. Rev. 2013, 33, 129–134. Available online: https://engineeringreview.org/index.php/ER/article/view/258 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Kocijan, A.; Donik, Č.; Jenko, M. The electrochemical study of duplex stainless steel in chloride solutions. Mater. Technol. 2009, 43, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hakiki, N.E.; Boudin, S.; Rondot, B.; da Cunha Belo, M. The electronic structure of passive films formed on stainless steels. Corros. Sci. 1995, 37, 1809–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramya, S.; Anita, T.; Shaikh, H.; Dayal, R.K. Laser Raman microscopic studies of passive films formed on type 316LN stainless steels during pitting in chloride solution. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 2114–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihrzo, A.; Segui, Y.; Bui, N.; Dabosi, F. On the conduction mechanisms of passive films on molybdenum-containing stainless steel. Corrosion 1986, 42, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegrelius, L.; Falkenberg, F.; Olefjord, I. Passivation of stainless steels in hydrochloric acid. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1999, 146, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.U.; Siddiqi, N.A.; Ahmad, S.; Andijani, I.N. The effect of dominant alloy additions on the corrosion behavior of conventional and high-alloy stainless steels in seawater. Corros. Sci. 1995, 37, 1521–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, A.; Merino, M.C.; Coy, A.E.; Viejo, F.; Arrabal, R.; Matykina, E. Pitting corrosion behavior of austenitic stainless steels—Combining effects of Mn and Mo additions. Corros. Sci. 2008, 50, 1796–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromaa, J.; Forsén, O. Corrosion behaviour of stainless steels and titanium in brackish seawater in the Gulf of Finland. Int. J. Electrochem. 2016, 2016, 3720280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, Z.; Wu, F.; Xia, J.; Huang, K.; Zhang, B.; Wu, J. Unmasking chloride attack on the passive film of metals. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Koyama, M.; Tsuzaki, K.; Wang, Z. In Situ Investigation of the Degradation of Passive Film on Stainless Steel in NaCl Solution Using a Synchrotron Radiation X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 330, 135212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.