Abstract

Endogenous selective attention, the cognitive process of selectively attending to non-literal, ambiguous, or multistable interpretations of sensory input, remains poorly understood at the network level. To address this gap, we applied Granger causality (GC) analysis to electroencephalographic (EEG) recordings to characterize effective connectivity during sustained attention to ambiguous visual stimuli. Participants viewed the Necker cube, whose left and right faces were modulated at 6.67 Hz and 8.57 Hz, respectively, enabling objective tracking of perceptual dominance via steady-state visually evoked potentials (SSVEPs). GC analysis revealed robust directed connectivity between frontal and occipito-parietal areas during sustained perception of a specific cube orientation. We found that the magnitude of the GC-derived F-statistics correlated positively with attention performance indices during the left-face orientation task and negatively during the right-face orientation task, indicating that interregional causal influence scales with cognitive engagement in ambiguous interpretation. These results establish GC as a sensitive and reliable approach for characterizing dynamic, directional neural interactions during perceptual ambiguity, and, most notably, reveal, for the first time, an occipito-frontal effective connectivity architecture specifically recruited in support of endogenous selective attention. The methodology and findings hold translational potential for applications in neuroadaptive interfaces, cognitive diagnostics, and the study of disorders involving impaired symbolic processing.

1. Introduction

Understanding how different brain regions interact during cognitive tasks is a central challenge in contemporary neuroscience. Cognitive processes such as attention, memory, and language rely not only on localized neural activity but also on the dynamic coordination of distributed brain networks [1,2]. In this context, the concept of brain connectivity has become a crucial framework for studying neural mechanisms. Three major forms of connectivity are commonly distinguished: structural connectivity (physical anatomical links), functional connectivity (statistical dependencies between neural signals), and effective connectivity (directed causal influences among neural elements) [1,3]. Among these, effective connectivity provides the most direct insight into how brain regions exert influence over one another, thereby offering a mechanistic perspective on information flow in the brain.

Endogenous selective attention, the capacity to selectively stabilize non-literal, ambiguous, or multi-stable interpretations of sensory input (e.g., perceiving a Necker cube as left- or right-facing), represents a high-order cognitive process that transcends basic stimulus-driven attention. Unlike selective attention to unambiguous features, sustained attention to ambiguous stimuli demands the dynamic integration of perceptual inference, executive control, and working memory to resolve ambiguity and maintain a chosen interpretation against competing alternatives [4,5].

Neurophysiologically, attention optimizes the allocation of limited neural resources across competing sensory streams. Electrophysiological studies consistently link attentional engagement to (i) increased mid-frontal theta (4–7 Hz), reflecting top-down control [6]; (ii) suppression of posterior alpha (8–12 Hz), indexing active inhibition of task-irrelevant regions [7]; and (iii) modulation of delta/theta phase–amplitude coupling in frontoparietal circuits during perceptual maintenance [8]. Bistable perception, paradigmatic of endogenous selective attention, further implicates a distributed network: perceptual transitions are associated with transient activation in the right superior parietal lobule (SPL) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) [5,9], whereas perceptual stability correlates with sustained activity in visual and inferotemporal cortices [10,11,12].

While neuroimaging confirms recruitment of occipital and prefrontal regions during endogenous attention task [13,14], a critical question remains unresolved: how do these regions causally interact to enable the flexible reconfiguration of perceptual states? Current evidence largely describes correlates of sustained attention to ambiguous stimuli, static activation patterns or undirected functional connectivity [15]. Yet ambiguity resolution inherently relies on directed, time-varying influences: for instance, does prefrontal cortex drive occipital disambiguation, or do bottom-up prediction errors initiate top-down updating? Without quantifying effective connectivity, we cannot distinguish epiphenomenal co-activation from mechanistic control.

Granger causality (GC) offers a principled framework to address this challenge. Originally formalized in econometrics [16], GC quantifies directed influence by testing whether the past of one neural signal improves the prediction of another, a property ideally suited for capturing the temporal precedence inherent in top-down control [17,18]. Critically, unlike correlation or phase-based metrics, GC provides a frequency-resolved estimate of information flow, enabling dissection of how control signals propagate through neural hierarchies [19,20].

Recent advances underscore GC’s power to reveal behaviorally and clinically meaningful architectures. For example, GC-informed dimensionality reduction achieved % classification accuracy in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) using only eight electroencephalography (EEG) electrodes [21]. While spectral GC uncovered state-specific reconfigurations of frontoparietal flow across meditation practices, demonstrating its sensitivity to cognitive states [22], GC has never been applied to endogenous selective attention, despite its reliance on precisely the kind of dynamic, goal-directed reconfiguration these studies highlight.

This omission is consequential. Although GC has illuminated perceptual selection, visual search, and working memory [23], endogenous selective attention poses a distinct challenge: it requires stabilizing ambiguous interpretations of identical sensory inputs, a process demanding sustained top-down biasing in the face of intrinsic ambiguity. Such computations likely engage a unique effective connectivity signature: not merely altered strength, but a reversal of directional hierarchy (e.g., frontal → occipital dominance) and band-specific functional roles (theta for engagement, alpha for inhibition), as suggested by oscillatory theories of attention [7].

Here, we bridge this gap by applying Region of Interest (ROI)-based GC to steady-state visually evoked potential (SSVEP)-tagged EEG during Necker cube rivalry, a paradigm that isolates endogenous selective attention while enabling frequency-specific causal tracking. We test three hypotheses: (i) Endogenous (top-down) attention engages a distinct effective connectivity architecture, characterized by reversed directional flow relative to exogenous (bottom-up) attention. (ii) This architecture exhibits a frequency-dependent dissociation, with theta-band connectivity promoting, and alpha-band connectivity impairing, perceptual stability. (iii) Individual differences in this network organization predict behavioral indices of attention performance. The findings are expected to advance our understanding of the dynamic neural mechanisms supporting endogenous selective attention and to contribute to the broader effort of linking cognitive theory with network neuroscience.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 details the experimental design, participant cohort, SSVEP-tagged Necker cube paradigm, and preprocessing pipeline. Section 3 presents quantitative indices of endogenous selective attention, derived from occipital SSVEP amplitudes, alongside group-level performance profiles. Section 4 introduces the ROI-based GC networks and reports frequency-specific effective connectivity patterns, directly relating directional network dynamics to individual differences in the attention measures. Section 5 discusses these findings in the context of attention theories and existing literature on bistable perception. Finally, Section 6 synthesizes the core contributions and outlines translational and methodological avenues for future work.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Twenty-eight healthy adults (18 female, 10 male; mean age 30 years, range: 20–58 years) participated in the study. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal visual acuity and reported no history of neurological, psychiatric, or developmental disorders. Participants were recruited from the local community via institutional mailing lists and gave written informed consent prior to data collection. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (Ref: CTB-UPM-2020-096) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Given the methodological focus of this work, namely, the development and validation of a ROI-based GC framework for effective connectivity analysis, the sample size was determined to ensure sufficient statistical power for reliable estimation of directional interactions while balancing practical constraints of EEG acquisition and preprocessing. The sample size aligns with prior exploratory EEG connectivity studies employing multivariate time-series modeling (e.g., [18,24]), and exceeds the minimum recommendation of for stable correlation/GC estimation in moderate-dimensional systems [25,26]. All analyses were conducted at the group level using robust descriptive statistics and non-parametric inference where appropriate.

2.2. Stimuli

Participants viewed bistable Necker cube stimuli, presented as white line drawings (RGB: 255, 255, 255) on a black background (RGB: 0, 0, 0). Stimuli were displayed centrally on a 22-inch LCD monitor (resolution: px; refresh rate: 60 Hz; mean luminance: 100 cd/) at a fixed viewing distance of 80 cm. Each cube subtended of visual angle (10 cm × 10 cm at screen), ensuring engagement of central and parafoveal vision (Figure 1).

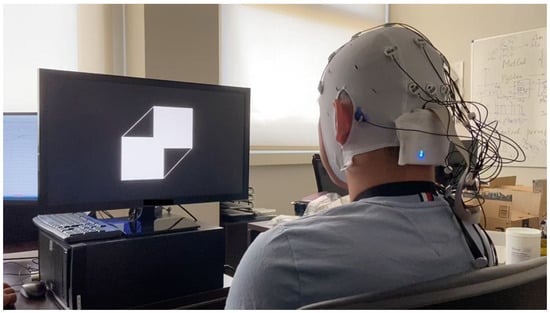

Figure 1.

Experimental setup: a participant performing the endogenous attention task while viewing a Necker cube with independently flickering left (6.67 Hz) and right (8.57 Hz) faces. EEG activity is recorded using a 16-channel wireless actiCAP system (Brain Products), with active electrodes placed according to the extended 10–20 system. Central fixation is maintained on a central red dot to minimize ocular artifacts.

The Necker cube was selected for its well-characterized perceptual bistability: despite being a 2D line drawing, it spontaneously alternates between two mutually exclusive 3D interpretations, left-facing (front face oriented leftward) and right-facing (front face oriented rightward), due to ambiguous depth cues (e.g., absence of occlusion, symmetric junctions) [27]. This property enables objective quantification of perceptual dominance via SSVEPs.

To tag each perceptual interpretation neurophysiologically, independent flicker modulation was applied to the left and right cube faces using square-wave luminance oscillations (100% contrast, 50% duty cycle). Specifically, the left face was modulated with Hz (theta band) and the right face with Hz (low-alpha band). These frequencies were chosen to: (i) be harmonically unrelated (minimizing cross-frequency interference in the Fourier domain), (ii) fall within canonical cognitive bands (theta for engagement, alpha for inhibition), and (iii) permit unambiguous identification of perceptual state via frequency-specific SSVEP power [28]. The resulting SSVEP responses served as objective neural biomarkers for tracking the temporal dynamics of endogenous selective attention.

2.3. Experimental Procedure and EEG Acquisition

Participants performed three counterbalanced tasks while fixating a central red dot ( diameter) to minimize eye-movement artifacts:

- Modulated Involuntary (MI): Passive viewing of the Necker cube without intentional stabilization of either percept.

- Modulated Left Voluntary (MLV): Active maintenance of the left-face cube interpretation.

- Modulated Right Voluntary (MRV): Active maintenance of the right-face cube interpretation.

Each task block lasted 30 s, separated by 20-s rest intervals to mitigate fatigue and ocular artifacts. Participants were instructed to suppress blinks during stimulation epochs, with blink breaks permitted during rest intervals.

EEG was recorded using a BrainAmp DC amplifier (Brain Products GmbH, Gilching, Germany) and a 16-channel wireless actiCAP slim system (EASYCAP GmbH, Wörthsee, Germany), positioned according to the extended 10–20 system (channels: Fp1, Fp2, F7, F3, Fz, F4, F8, FC1, Cz, FC2, P3, Pz, P4, O1, Oz, O2). Electrode impedances were maintained below 10 k using conductive gel (SuperVisc, EASYCAP). A common reference (FCz) and ground (AFz) were employed. Data were digitized at 500 Hz with a hardware bandpass filter (0.1–250 Hz) and notch filter (50 Hz).

Real-time monitoring was performed using BrainVision Recorder v1.2 (Brain Products GmbH) to ensure signal quality. Offline preprocessing and analysis were conducted in MATLAB R2022b (MathWorks) using the Brainstorm toolbox [29] and custom Python 3.9 scripts (MNE-Python [30], SciPy v1.16.2, NumPy 2.1.0).

2.4. Data Preprocessing

Raw EEG data were preprocessed to attenuate physiological and environmental artifacts while preserving stimulus-locked neural responses. The pipeline comprised the following steps:

Epoch segmentation: Continuous data were segmented into 30-s task epochs aligned to stimulus onset.

- –

- Trend removal: A global linear trend was regressed out from each channel using the robust detrending method of [31], minimizing slow drifts without distorting event-related dynamics.

- –

- Filtering: Zero-phase, 4th-order Butterworth IIR filters were applied: (i) a dual-notch filter (bandwidth: 0.1 Hz) at 50 Hz (mains) and 60 Hz (monitor refresh harmonic); (ii) a bandpass filter (4–20 Hz) to retain frequencies of interest while attenuating high-frequency muscle artifacts and low-frequency drift. All filters were applied bidirectionally (via filtfilt) to avoid phase distortion.

- –

- Ocular artifact correction: Eye movement and blink artifacts were identified using independent component analysis (ICA; runica in EEGLAB) and removed based on component topography, time course, and spectral profile [32].

2.5. Frequency-Band Selection and Spectral Analysis

To identify stimulus-relevant neural dynamics, we first conducted a time–frequency analysis of occipital EEG (O1, Oz, O2) using the continuous wavelet transform (CWT) with a complex Morlet wavelet [33]. The CWT provides a joint time–frequency representation of signal energy, enabling tracking of spectral power fluctuations associated with perceptual stabilization and switching [13,34,35].

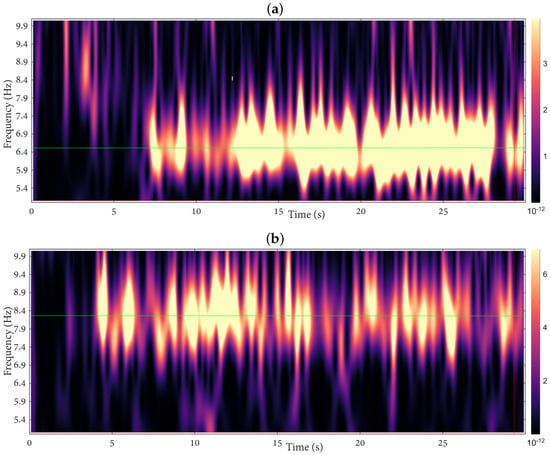

Figure 2a and Figure 2b display the wavelet energy at O1 for subject #4 during MLV and MRV tasks, respectively. During MLV, sustained enhancement in Hz (targeting Hz) indicates stable entrainment to the left-face flicker and successful maintenance of the left-facing percept; conversely, MRV shows dominant Hz activity (targeting Hz), reflecting right-face stabilization. Transient energy drops (cool tones) correspond to perceptual switches, while brief co-activation of both bands (warm tones) signifies moments of rivalry-induced ambiguity. Critically, the dominant frequency band remains stable for the majority of each 30-s epoch, confirming effective task-driven perceptual biasing.

Figure 2.

Time–frequency wavelet energy at O1 for subject #4 during (a) MLV and (b) MRV tasks. Warm colors indicate high energy. Sustained entrainment is observed in Hz during MLV and Hz during MRV, with transient drops reflecting perceptual switches.

These wavelet-derived spectral profiles guided our selection of and as analysis bands, ensuring subsequent metrics isolate stimulus-locked neural responses. We thus quantified endogenous selective attention via: (i) occipital SSVEP amplitudes (O1, Oz, O2), computed with Welch’s method (1-s Hanning windows, 50% overlap), and (ii) frequency-domain GC, inferred via F-statistics.

SSVEP amplitude, integrating power across the full epoch, was chosen over switch-counting or epoch duration to provide a robust, frequency-specific index of sustained attentional bias, minimizing sensitivity to transient fluctuations.

3. Attention Measures

We propose two criteria for quantifying endogenous selective attention: the Frequency Independent Criterion (FIC) and the Frequency Dependent Criterion (FDC). Both criteria are based on SSVEPs of the EEG signals recorded from the occipital area. The SSVEP corresponding to involuntary attention (MI task) serves as a baseline for calculating attention performance indices for both left-face (MLV task) and right-face (MRV task) perceptions.

3.1. Frequency Independent Criterion (FIC)

The FIC is based on the difference in SSVEP amplitudes between voluntary and involuntary attention tasks, computed separately for each frequency range ( and ), and for each perceived cube orientation (left-face or right-face). Specifically, by subtracting the SSVEP amplitude observed during involuntary attention from that obtained during voluntary attention, we aimed to emphasize the relative enhancement of the corresponding spectral amplitudes during voluntary attention. To allow comparison across participants, these difference values are normalized with respect to their respective individual mean amplitudes. Thus, endogenous selective attention, quantified by the FIC, for the left-face and right-face percepts can be assessed using the following two variables:

where and represent SSVEP amplitudes at for MLV and MI tasks, respectively, and and denote SSVEP amplitudes at for MRV and MI tasks, respectively.

The FIC denotes the normalized discrepancies in the SSVEP amplitudes between tasks pertaining to endogenous (MLV and MRV tasks) and involuntary (MI task) attention. This criterion assesses the participant’s ability to concentrate attention on a particular cube orientation and enables a distinct analysis of their preference for either the left or right cube orientation. As evident from Equations (1) and (2), and are independent of the modulation frequencies, since each of them is measured within one frequency range, for and for . Therefore, they indicate the extent to which the spectral energy changes when the participant focuses attention on a specific cube orientation. In essence, these indices reflect the individual’s proficiency in sustained attention, signifying their capacity to voluntarily attend to the interpreted cube orientation.

3.2. Frequency-Dependent Criterion (FDC)

In contrast to the FIC, the FDC is derived from the difference in SSVEP amplitudes measured in two frequency ranges ( and ) within the same attentional task. Thus, endogenous selective attention, as quantified by the FDC, for the left-face and right-face interpretations can be estimated using the following two variables, respectively:

The FDC bears resemblance to the approach proposed by Chholak et al. [36], who gauged voluntary and involuntary attention using 40 channels of MEG. Unlike their approach, our study applies this criterion to EEG signals obtained from only three channels in the occipital area. By employing the FDC, we discern disparities in spectral energy across two flicker frequencies when participants perceive left-face and right-face orientations.

While both FIC and FDC criteria serve as metrics for endogenous selective attention, they encapsulate distinct perceptual abilities. A fundamental disparity lies in how they evaluate attention: the FIC assesses attention toward the left-face and right-face percepts separately, whereas the FDC estimates the individual’s capacity for switching between these two distinct percepts.

As evident from Equations (1)–(4), all attention performance indices are bounded within the interval . Positive values reflect successful engagement of sustained attention (i.e., enhanced neural response during attentive relative to non-attentive conditions), whereas negative values indicate either poor attentional engagement or attention directed toward the incorrect cube orientation. Values near zero suggest no systematic distinction between attentive and non-attentive task performance. To objectively classify participants based on their attentional profiles, we employed bagging (bootstrap aggregating) analysis.

3.3. Bagging Analysis

The bagging procedure introduced by Rousseeuw et al. [37] addresses the instability of results that often arises when applying complex models to relatively small datasets. A core component of bagging analysis is the bagplot (or starburst plot), which is based on the concept of Tukey depth (also known as location depth). Introduced by John Tukey [38], this metric quantifies how central or extreme a point is within a distribution. Formally, for a set of n points in a two-dimensional space, the Tukey depth of a point x is defined as the smallest fraction of data points contained within any closed half-plane that contains x.

Mathematically, the Tukey depth of x with respect to point cloud is expressed as

where denotes the indicator function, equaling 1 if the argument is true and 0 otherwise. This measure provides a non-parametric, geometrically intuitive way to assess the centrality of a point within a multivariate distribution.

To characterize inter-subject variability in sustained attention to the ambiguous stimulus, we applied bagplot analysis, a robust, depth-based method ideal for bivariate data (i.e., right-face vs. left-face attention performance indices) and particularly advantageous for datasets with high within-group heterogeneity [39]. For each participant, we computed the FIC and FDC indices by Equations (1)–(4) across occipital channels (O1, Oz, O2), yielding scalar metrics of sustained attentional bias.

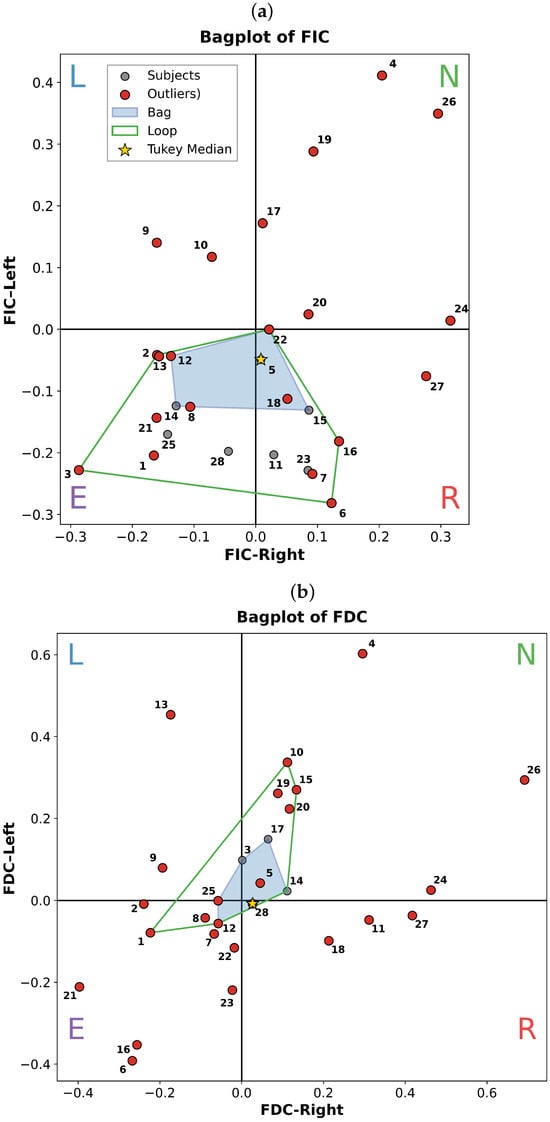

Figure 3 presents the resulting bivariate distributions. The central region (bag, dark polygon) captures the 50% most typical participants, while outliers (outside the fence) indicate atypical attentional strategies. Four interpretable clusters emerge:

Figure 3.

Bagplots visualizing inter-subject variability in attention performance. Right-face versus left-face attention capacity according to (a) FIC and (b) FDC computed via Equations (2) and (3). Each point represents one participant, labeled by subject #. Quadrants reflect perceptual bias: N (normal), L (left-dominant), R (right-dominant), and E (erroneous/incoherent perception). The bag (dark polygon) encloses the 50% most central observations, defined as the convex hull of the deepest points [37]. The fence (dashed loop) inflates the bag by a factor of 3 about the Tukey median; points outside this loop are flagged as potential outliers in a distribution-free, data-depth-based framework. This robust visualization emphasizes multivariate centrality and dispersion, minimizing sensitivity to extreme values.

- –

- Quadrant N (Normal): High FIC and FDC (>0), indicating robust, unbiased stabilization of both percepts. These participants show strong frequency-specific entrainment: left-face percepts elevate power, right-percepts elevate power.

- –

- Quadrants L/R (Left/Right Bias): Asymmetric profiles, elevated / or /, reflect stable but lateralized attentional preference.

- –

- Quadrant E (Erroneous): Negative FIC/FDC values across both dimensions, suggesting failure to engage endogenous attention tasks. This may arise from task misunderstanding, fatigue, or non-neural artifacts (e.g., excessive blinking, poor signal quality).

Critically, bagplots move beyond group averages to reveal qualitatively distinct subgroups, enabling stratification by attentional strategy rather than mere performance magnitude. This is essential for regression-based modeling of continuous indices (FIC/FDC), where outliers can disproportionately influence parameter estimates. By identifying and contextualizing outliers, the approach ensures robust inference while preserving individual differences, a key advantage over univariate summarization.

Analysis of Figure 3 reveals distinct subgroups among 28 participants based on FIC and FDC indices. Six individuals (Subjects #4, #17, #19, #20, #24, #26) exhibited robust endogenous selective attention, occupying quadrant N in both / and / spaces, indicating strong, balanced capacity to stabilize either perceptual interpretation. Within this group, Subjects #4 and #26 were the most extreme outliers (Tukey depth ), reflecting exceptionally high SSVEP entrainment fidelity across both frequency bands.

A second subgroup (Subjects #3, #5, #10, #14, #15) fell within quadrant N only for FDC, but not FIC, suggesting preserved perceptual discrimination despite reduced integration strength. Notably, no participants exhibited strong performance in FIC alone.

Conversely, Subjects #1, #2, #8, #12, #21, and #25 consistently occupied quadrant E (FIC < 0, FDC < 0), indicating a failure to establish frequency-specific SSVEP entrainment for either perceptual state. Notably, Subject #21 self-reported a history of strabismus during post-experiment debriefing, a condition associated with disrupted binocular integration and altered depth perception [28]. This provides a plausible mechanistic account for their atypical neural responses, as monocular viewing or anomalous rivalry dynamics may prevent stable perceptual binding.

Further, a subset of participants exhibited rigid perceptual biases: Subject #9 exclusively stabilized the left-bias percept ( > 0, < 0), while Subjects #11, #18, and #27 showed the converse right-bias pattern. These individuals resided in quadrants L and R, respectively, reflecting intact but lateralized attention capacity rather than global impairment.

Collectively, these stratifications demonstrate that endogenous selective attention comprises dissociable components: (i) integration strength (FIC), reflecting the ability to bind sensory input into a coherent percept, and (ii) discrimination fidelity (FDC), indexing sensitivity to frequency-tagged evidence. The observed profiles, balanced (N), lateralized (L/R), deficient (E), or dissociated (/), suggest distinct underlying mechanisms rather than a unidimensional continuum.

We should note that the presentation of these four distinct patterns serves a descriptive and illustrative purpose, not a comparative statistical one. In this regard, our primary aims were twofold: (i) to demonstrate that our quantitative attention metrics capture a spectrum of behavioral outcomes, where distinct performance patterns (perfect maintenance, right/left bias, lapses) correspond to visibly separable configurations in metric space, and (ii) to compactly visualize the central tendency and dispersion of these metrics within each pattern. This provides an intuitive, graphical proof-of-concept for how such metrics can be used to characterize attentional states.

While these patterns are robust within our cohort, replication in larger, clinically diverse samples is warranted to establish generalizability. Future work should incorporate objective measures of ocular alignment (e.g., synoptophore testing) and control for interocular suppression, particularly when studying populations with known visual or attentional anomalies. Nevertheless, the bagplot framework proves highly effective for visualizing multidimensional individual differences, and provides a principled basis for stratifying participants in subsequent connectivity analyses (Section 4).

3.4. Composite Attention Performance Index

Individual profiles revealed dissociations between FIC and FDC with some participants exhibiting stronger integration (FIC) than discrimination (FDC), or vice versa. Such heterogeneity aligns with evidence that sustained attention and perceptual discrimination rely on partially distinct neural mechanisms [40,41]. To capture overall attention capacity while preserving sensitivity to both processes, we define a composite index:

where quantifies the total attention performance across both perceptual states and both cognitive dimensions. This linear aggregation assumes additive contributions of integration and discrimination to overall performance, a principle supported by hierarchical models of attention [42].

Figure 4 displays alongside its FIC and FDC components for all 28 participants. Critically, in 13 participants (54%), indicating net positive entrainment to the instructed percept, consistent with group-level task compliance in a healthy cohort. The distribution of shows no significant deviation from normality (Shapiro–Wilk , ), and ranked scores follow a near-linear decay (Spearman’s , ), confirming unimodal variation without evidence of discrete subpopulations. This pattern reflects expected interindividual variability in top-down control, modulated by transient factors (e.g., vigilance, motivation) and stable traits (e.g., working memory capacity) [43,44].

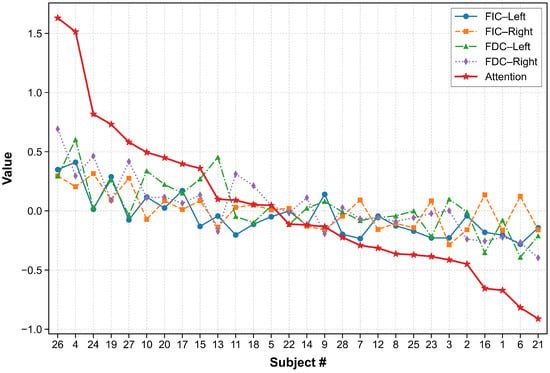

Figure 4.

Individual attention profiles. Signs show , , , and contributions (color-coded) for each participant; red stars indicate the composite index .

The two top-performing participants (Subjects #26 and #4) exhibited values exceeding above the group mean (, ), placing them among the most extreme positive outliers (Tukey depth ). Post-hoc debriefing indicated both reported high task engagement and explicit goal-setting strategies (e.g., “I focused on locking the cube in place”; “I treated each block like a challenge to beat”). While self-report data must be interpreted cautiously due to potential demand characteristics, these accounts are consistent with neurocognitive models in which motivation amplifies top-down control signals in frontoparietal networks, thereby stabilizing perceptual representations against intrinsic noise [45,46]. Importantly, their elevated was not driven by a single component but by uniformly high FIC and FDC, suggesting a generalized enhancement in both perceptual integration and discrimination fidelity, rather than a strategy-specific advantage.

Conversely, the lowest-performing participants (Subjects #6 and #21; ) showed negative attention entrainment across all bands, corroborating their quadrant E classification (Section 3.3). As noted earlier, Subject #21’s strabismus provides a plausible physiological explanation, underscoring the importance of screening for binocular vision anomalies in SSVEP-based paradigms.

In sum, provides a continuous, behaviorally grounded metric of endogenous selective attention capacity that: (i) integrates complementary cognitive dimensions (integration and discrimination), (ii) reflects expected population-level variability, and (iii) identifies extreme performers whose neural and behavioral profiles warrant targeted investigation.

4. Granger Causality

4.1. Definition

GC is a statistical method for determining whether one time series can predict another. While not proving true causation, it identifies directional predictive relationships between signals. The key properties of GC are (i) predictive (not causal): only measures if X’s past improves prediction of Y; (ii) asymmetric: ; (iii) regression-based: uses linear autoregressive models; (iv) frequency-aware: can analyze specific bands (e.g., alpha, beta, or gamma bands).

GC quantifies the strength of effective connectivity between two time series and , which is evaluated by comparing the prediction performance of two autoregressive models. The restricted model includes only the past values of :

where are autoregressive coefficients and denotes the residual error.

The full model additionally incorporates the past of :

where are the coupling coefficients and denotes the residual error for the full model.

The GC statistic is defined via an F-test:

where and are the residual sum of squares of the restricted and full models, respectively, m is the number of additional parameters in the full model, N is the number of samples, and p is the model order (number of lags).

The F values are non-negative and quantify the predictive influence of X on Y:

A value of indicates that X does not improve the prediction of Y, while indicates a directed influence from X to Y, with larger values reflecting stronger predictive power. Statistical significance is determined by comparing F to the critical value of the F-distribution with degrees of freedom.

4.2. Network Construction

The GC network was computed using a vector autoregressive (VAR) model of order 5 (lag order), selected via the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to balance model fit and complexity. Across all experimental tasks (MI, MLV, and MRV), a total of 240 statistically significant directed functional connections were identified using GC analysis (significance threshold: , ).

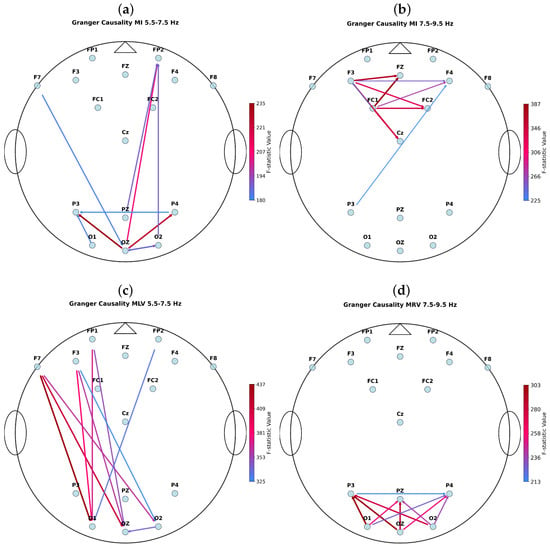

Figure 5 represents the top 10 strongest connections during MI, MLV, and MRV tasks for subject #4.

Figure 5.

Top 10 strongest connections during (a,b) MI, (c) MLV, and (d) MRV tasks in the (a,c) and (b,d) spectral ranges for subject #4. The arrows indicate causality directions and their color indicate the corresponding F-statistic values.

The strongest GC links per task/frequency band were: MI, : Oz → P3 (F = 234.55), MI, : FC1 → Fz (F = 386.57), MLV: F7 → O1 (F = 437.04), and MRV: Oz → P3 (F = 302.60). Notably, during the MLV task, we observed robust bidirectional (forward and feedback) information flow between frontal (F7/F3/FP1) and occipital (O1/Oz/O2) regions, consistent with top-down attentional modulation of visual imagery. In contrast, during the MRV task, while strong intra-occipito-parietal coupling was present, the dominant directional links did not involve frontal areas; instead, the strongest connections were confined within posterior cortices, suggesting a more bottom-up or perceptually anchored processing mode.

These results reveal a hemifield-dependent reversal of effective connectivity hierarchy: mental stabilization of the left-facing cube engages a top-down fronto-occipital control loop (frontal → occipito-parietal), consistent with goal-directed executive modulation; in contrast, right-facing stabilization recruits a bottom-up occipito-parietal dominance (occipito-parietal → frontal), reflecting stimulus-driven visuospatial integration.

4.3. ROI-Based Granger Causality Analysis

Since the SSVEP-driving (flicker) frequencies primarily entrain early visual areas, predominantly the occipital cortex, we focused our GC analysis on directional interactions between occipito-parietal and frontal regions, which jointly support attentional selection and perceptual stabilization. To characterize these large-scale effective interactions in a neuroanatomically principled manner, we selected four interpretable ROIs in the cortical surface (Figure 6): occipito-parietal, central, left-frontal, and right-frontal. This parcellation was guided by two key considerations: (i) the occipital cortex serves as the primary entry point for visual input and a critical substrate for attentional performance monitoring; and (ii) occipital and parietal regions exhibit strong structural connectivity and functional coupling, forming the posterior node of the dorsal attention network, which interfaces with frontal control regions to mediate top-down attentional biasing [47,48].

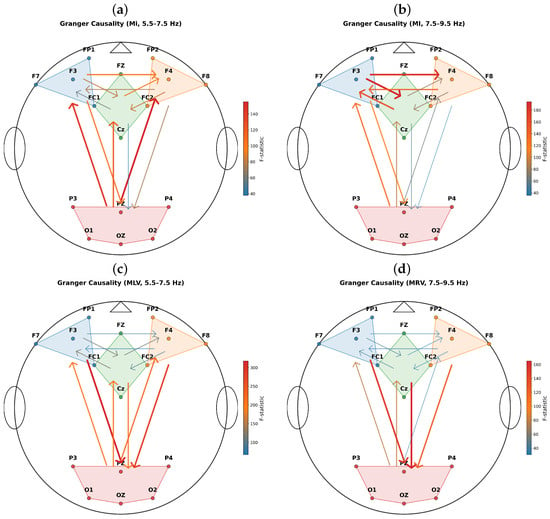

Figure 6.

Effective connectivity between cortical ROIs during (a,b) involuntary attention (MI task), (c) mental left-visualization (MLV task), and (d) mental right-visualization (MRV task) in subject #4. The GC was measured in the frequency region (a,c) Hz and (b,d) Hz. Arrow direction indicates the causal influence (Granger-causal flow), while color and line width encode the associated F-statistic magnitude (see colorbar).

The ROIs were defined as follows:

- Occipito-parietal: O1, Oz, O2, P3, Pz, P4—encompassing primary visual and posterior parietal cortices;

- Central: Cz, FC1, FC2, Fz—covering sensorimotor and supplementary motor areas;

- Left-frontal: F7, F3, Fz, FC1—representing left dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal regions;

- Right-frontal: F4, F8, FP2, FC2—representing right homologous prefrontal regions.

Note that FC1 and FC2 were assigned to both central and frontal regions to reflect their transitional anatomical position at the frontal–central junction (Brodmann areas 6/8/44).

Effective connectivity between ROIs was quantified using time-domain GC in the vicinity of the modulation frequencies: Hz and Hz. GC significance was assessed via F-statistics (SSR-F test, , corrected for multiple comparisons where applicable), with arrow width and color scaled proportionally to the F-value, emphasizing the strength of directed influence.

Figure 6 reveals a frequency- and task-dependent reconfiguration of large-scale effective connectivity. Notably, in the band, the MLV task (Figure 6c) exhibits markedly enhanced effective connectivity from frontal to occipito-parietal regions compared to MI (Figure 6a), whereas the MRV task (Figure 6d) shows attenuated bidirectional coupling relative to MI in the band (Figure 6b). Critically, the dominant causal direction shifts across tasks: during MI (involuntary attention), top-down influences from occipito-parietal to frontal regions prevail (Figure 6a,b), consistent with stimulus-driven attentional orienting [47]. In contrast, during MLV/MRV (endogenous attention task), a reversal occurs, the causality from frontal to occipito-parietal area dominates (Figure 6c,d), suggesting active top-down control of visual perception [49].

4.4. Relationship Between Attention Performance and Effective Connectivity

Table 1 reports Pearson correlation coefficients (r) and associated p-values (FDR-corrected for multiple comparisons) between attention performance indices (FIC and FDC) and GC metrics derived from occipito-parietal ↔ frontal interactions.

Table 1.

Correlation coefficients r and p-values between attention performance and GC.

A striking frequency-dependent dissociation emerges:

- During the MLV task (left-cube orientation; Hz, theta band), both and show positive correlations with Sum GC, indicating that stronger bidirectional effective connectivity supports enhanced left-percept stabilization.

- During the MRV task (right-cube orientation; Hz, alpha band), both and exhibit negative correlations with Sum GC, suggesting that increased connectivity impedes right-percept maintenance.

This oppositional pattern aligns with the canonical functional roles of theta and alpha oscillations in attention: theta-band interactions facilitate top-down engagement and working memory maintenance [50], whereas alpha-band activity mediates active inhibition of task-irrelevant representations [7]. Thus, enhanced theta-mediated GC promotes perceptual integration (MLV), while heightened alpha-mediated GC may reflect inhibitory top-down processes that paradoxically reduce right-face percept stabilization (MRV).

5. Discussion

The objective of this study was to quantify endogenous selective attention and identify its neural correlates. We proposed that spectral energy at the flicker frequencies within the occipital cortex provides a reliable biomarker for sustained attentional control of bistable perception, specifically, for the voluntary maintenance of a selected interpretation (left- or right-oriented) of a flickering Necker cube. By deriving attention measures from occipital activity, we aimed to isolate attentional processes directly tied to the perceptual relevance of visual information.

Although endogenous attention to ambiguous stimuli constitutes a form of sustained attention, it is distinguished by its object. Unlike maintaining focus on a stable feature (e.g., color or location), it requires the active, volitional stabilization of one perceptual interpretation against a competing alternative. This “maintenance” is inherently dynamic, involving the continuous suppression of the rival percept. Furthermore, this process differs from working memory, which typically maintains a representation in the absence of sensory input. Here, the stimulus is continuously present, placing the mechanism within the domain of online perceptual selection—a real-time attentional biasing of competing neural populations. The sustained neural signal we measured likely reflects this ongoing competitive biasing operation rather than the passive retention characteristic of working memory.

While previous research has predominantly associated decision-making processes with the frontoparietal cortex [5,51], emerging studies highlight the significant involvement of the visual cortex, not only in the interpretation of sensory stimuli, but also in facilitating subsequent decision-making [8,52,53,54]. This evolving perspective suggests that visual processing is not solely driven by feedforward neural mechanisms. Rather, it reflects a dynamic, high-order interaction that incorporates feedback from frontal to occipito-parietal regions. Such an integrated, bidirectional network supports a more complex and adaptive system of perception and decision-making, underscoring the crucial role of feedback loops in sensory interpretation and action planning.

Our study was designed to delve into the intricacies of effective connectivity due to the growing importance of such networks in contemporary neuroscience. Since the frequency Hz applied to the left face of the cube belongs to the theta-band (4–7 Hz), its activity is consistently associated with enhanced top-down attentional engagement, working memory maintenance, and inter-regional communication in fronto-occipital networks [55]. Our results demonstrate that endogenous selective attention is associated with enhanced effective connectivity between occipito-parietal and frontal regions during the left-face cube interpretation task (MLV), suggesting top-down modulation of sensory processing during ambiguous interpretation. Increased theta-mediated GC thus reflects adaptive recruitment of control resources, supporting better performance. Notably, a similar pattern of effective connectivity between frontal and occipito-parietal areas has been reported during short-term memory maintenance [50], raising the possibility that sustained attention to ambiguous stimuli relies on overlapping neural machinery, particularly the prolonged preservation and manipulation of internal representations. However, while this overlap is suggestive, it does not imply identity: endogenous selective attention may recruit short-term memory mechanisms without being reducible to them.

Conversely, the frequency Hz applied to the right face of the cube belongs to the alpha-band (8–12 Hz) activity, which is widely interpreted as an active inhibitory mechanism that suppresses task-irrelevant regions or distractors [7,56]. In visual tasks, elevated occipital/parietal alpha power, and by extension, stronger alpha-band GC, typically reflects disengagement from the stimulus or inhibition of competing spatial locations [57,58]. Thus, higher alpha-band GC from frontal to occipito-parietal regions during right-face viewing may indicate increased top-down suppression of the non-attended hemifield or internal noise, paradoxically correlating with reduced performance when task demands require sustained encoding of the alpha-driven stimulus.

Critically, this pattern suggests that the functional valence of fronto-occipital effective connectivity is not fixed, but rather depends on the underlying oscillatory regime: theta-band GC facilitates stimulus encoding, while alpha-band GC implements inhibitory control, consistent with the “gating-by-inhibition” framework [7]. Our findings thus extend the classical view of alpha as a purely idling rhythm, highlighting its active role in dynamic attentional routing.

Our results reveal an apparent paradox: if frontal-to-occipital alpha-band connectivity serves as an inhibitory control signal to maintain the right-face percept, why does greater connectivity correlate with poorer attentional performance? This finding can be explained by two non-mutually exclusive interpretations, challenging the simplistic model equating alpha-band activity with inhibition. To resolve this paradox, we must disentangle two potential factors: the task’s inherent cognitive demand and the specific functional role of alpha-band connectivity.

The Role of Cognitive Demand: A parsimonious explanation might attribute the negative correlation to a greater intrinsic difficulty in maintaining the right-face percept, which could degrade or destabilize neural communication. If this were the case, we would predict either no reliable correlation or highly variable, non-systematic connectivity. The observation of a consistent and significant negative correlation argues against a simple difficulty-driven disruption. Instead, it indicates a specific, albeit inhibitory, neurophysiological relationship, suggesting that the alpha-band connectivity is modulating performance in a systematic, albeit counterintuitive, way.

The Role of the Alpha Rhythm: A more nuanced interpretation centers on the dual functional nature of alpha oscillations in attention. Our hypothesis is that the GC measured within the narrow entrainment band (7.5–9.5 Hz) captures a directed signal, whereas the classic “alpha suppression” phenomenon reflects a global decrease in the power of the broader endogenous alpha rhythm (8–12 Hz). During effortful attentional maintenance, a strong top-down signal (high GC) in the alpha channel might therefore coincide with, or even necessitate, a suppressed endogenous alpha backdrop. The observed negative correlation could thus stem from a trade-off: successful maintenance might be associated with efficient, low-amplitude signaling (lower observed GC in our metric), whereas high GC might reflect an inefficient, high-effort state where the system struggles to suppress the competing percept. This interpretation reframes alpha-band connectivity not as a unitary “inhibition” signal, but as a dynamic component within a larger attentional control system.

To conclusively address the disentangle frequency-specific from task-specific effects, future experiments employing a fully counterbalanced design are essential. Specifically, two conditions should be compared:

Condition A: Left-face cued with 6.67 Hz (theta) modulation; right-face cued with 8.57 Hz (alpha) modulation (as in the current study).

Condition B (Counterbalanced): Left-face cued with 8.57 Hz modulation; right-face cued with 6.67 Hz modulation. Only such a design can statistically isolate the effects of frequency band from those of perceptual interpretation. Alternatively, experiments using modulation frequencies outside the alpha band (e.g., within the gamma band) could further clarify the neural mechanisms of attentional control in bistable perception.

It is also important to clarify that the observed modulation of spectral power at frequencies and associated with left- and right-face oriented Necker cube percepts does not arise from changes in retinal illumination due to eye movements. Under the experimental conditions, the visual stimulus remained fully visible and stable on the retina because: (i) the entire source lies within the eye’s visual field (which holds true for objects smaller than approximately 120°, and especially for those under 10°; (ii) the pupils are sufficiently large to admit all rays arriving from the source (which is almost always the case for typical extended sources under everyday viewing conditions); (iii) there are no obstructions (such as the iris or other ocular structures) blocking part of the light. Thus, any percept-related spectral changes reflect endogenous neural processing, not exogenous variations in retinal input.

6. Conclusions

This study establishes a causal systems-level account of endogenous selective attention, a high-order cognitive process long overlooked in network neuroscience, by integrating ROI-based Granger causality with frequency-tagged SSVEP paradigms. We demonstrate that sustained attention to ambiguous stimuli is not a passive perceptual state, but an active control process mediated by a directionally inverted fronto-occipital hierarchy (frontal ↔ occipito-parietal), distinct from the stimulus-driven flow observed in involuntary attention. Critically, this architecture exhibits a frequency-dependent functional dissociation: theta-band connectivity enhances performance, while alpha-band connectivity impairs it, revealing band-specific roles in top-down facilitation versus inhibitory gating.

These findings move beyond correlational models of symbolic cognition, providing testable mechanisms for how large-scale brain networks dynamically reconfigure to stabilize ambiguous interpretations. By linking directional network dynamics to quantifiable behavioral indices (FIC/FDC), our framework offers a principled pathway toward objective biomarkers for disorders marked by attention processing deficits, including schizophrenia (impaired metaphor comprehension), autism spectrum disorder (literal bias), and semantic dementia. Future work will extend this approach to clinical cohorts and integrate it with real-time neurofeedback, paving the way for mechanism-informed interventions.

Author Contributions

W.E.P.d.l.V.: methodology, investigation, data curation, software, formal analysis, validation, writing–original draft preparation; A.N.P.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, validation, visualization, writing–original draft preparation, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (Approval Code: 2020-096).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the subject involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Friston, K.J. Functional and effective connectivity: A review. Brain Connect. 2011, 1, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassett, D.S.; Sporns, O. Network neuroscience. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sporns, O. The structure and function of complex brain networks. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 15, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanai, R.; Bahrami, B.; Rees, G. Cortical network dynamics of perceptual decision-making in the human brain. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brascamp, J.; Sterzaer, P.; Blake, R.; Knapen, T. Multistable perception and the role of the frontoparietal cortex in perceptual inference. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2018, 69, 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yang, K.; Guo, J. Link prediction with hypergraphs via network embedding. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, O.; Mazaheri, A. Shaping functional architecture by oscillatory alpha activity: Gating by inhibition. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2010, 4, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devia, C.; Concha-Miranda, M.; Rodríguez, E. Bi-stable perception: Self-coordinating brain regions to make-up the mind. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 22, 805690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megumi, F.; Bahrami, B.; Kanai, R.; Rees, G. Brain activity dynamics in human parietal regions during spontaneous switches in bistable perception. NeuroImage 2015, 107, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ress, D.; Heeger, D.J. Neuronal correlates of perception in early visual cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2003, 6, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, P.A.; Guggisberg, A.G.; Mottaz, A.; Seeck, M.; Michel, C.M.; Blanke, O. Role of the prefrontal cortex in attentional control over bistable vision. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2006, 18, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Hardstone, R.; He, B.J. Neural oscillations promoting perceptual stability and perceptual memory during bistable perception. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chholak, P.; Maksimenko, V.A.; Hramov, A.E.; Pisarchik, A.N. Voluntary and involuntary attention in bistable visual perception: A MEG study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 597895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña Serrano, N.; Jaimes-Reátegui, R.; Pisarchik, A.N. Hypergraph of functional connectivity based on event-related coherence: Magnetoencephalography data analysis. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, C.; Massimini, M.; Boly, M.; Tononi, G. Neural correlates of consciousness: Progress and problems. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.W.J. Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica 1969, 37, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressler, S.L.; Seth, A.K. Wiener–Granger causality: A well established methodology. NeuroImage 2011, 58, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seth, A.K.; Barrett, A.B.; Barnett, L. Granger causality analysis in neuroscience and neuroimaging. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 3293–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Chen, Y.; Bressler, S.L. Granger causality: Basic theory and application to neuroscience. In Handbook of Time Series Analysis: Recent Theoretical Developments and Applications; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2006; pp. 437–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, A.B.; Barnett, L.; Seth, A.K. Multivariate Granger causality and generalized variance. Phys. Rev. E 2015, 81, 041907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torghabeh, F.A.; Modaresnia, Y.; Hosseini, S.A. EEG-based effective connectivity analysis for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder detection using color-coded Granger-causality images and custom convolutional neural network. Int. Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 10, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolev, V.; Beshkov, K.; Malinowski, P.; Raffone, A.; Yordanova, J. Distinct patterns of directed brain connectivity in focused attention, open monitoring and loving kindness meditation: An EEG Granger causality study with long-term meditators. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, L. Understanding brain networks and brain organization. Phys. Life Rev. 2014, 11, 400–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L.; Seth, A.K. The MVGC multivariate Granger causality toolbox: A new approach to Granger-causal inference. J. Neurosci. Meth. 2014, 223, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadehfar, V.; Ghassemi, F.; Fallah, A. Brain connectivity estimation pitfall in multiple trials of electroencephalography data. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönbrodt, F.D.; Perugini, M. At what sample size do correlations stabilize? J. Res. Personal. 2013, 47, 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, D.A.; Logothetis, N.K. Multistable phenomena: Changing views in perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 1999, 14, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norcia, A.M.; Appelbaum, L.G.; Ales, J.M.; Cottereau, B.R.; Rossion, B. The steady-state visual evoked potential in vision research: A review. J. Vis. 2015, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadel, F.; Baillet, S.; Mosher, J.C.; Pantazis, D.; Leahy, R.M. Brainstorm: A user-friendly application for MEG/EEG analysis. Comput. Intel. Neurosci. 2011, 2011, 879716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramfort, A.; Luessi, M.; Larson, E.; Engemann, D.A.; Strohmeier, D.; Brodbeck, C.; Goj, R.; Jas, M.; Brooks, T.; Parkkonen, L.; et al. MEG and EEG data analysis with MNE-Python. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Bian, G.B.; Tian, Z. Removal of artifacts from EEG signals: A review. Sensors 2019, 19, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.P.; Makeig, S.; Humphries, C.; Lee, T.W.; McKeown, M.J.; Iragui, V.; Sejnowski, T.J. Removing electroencephalographic artifacts by blind source separation. Psychophysiol. 2000, 37, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hramov, A.E.; Koronovskii, A.A.; Makarov, V.A.; Pavlov, A.N.; Sitnikova, E. Wavelets in Neuroscience; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ghuman, A.S.; McDaniel, J.R.; Martin, A. A wavelet-based method for measuring the oscillatory dynamics of resting-state functional connectivity in MEG. Neuroimage 2011, 56, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimenko, V.A.; Hramov, A.E.; Grubov, V.V.; Nedaivozov, V.O.; Makarov, V.V.; Pisarchik, A.N. Nonlinear effect of biological feedback on brain attentional state. Nonlin. Dyn. 2019, 95, 1923–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chholak, P.; Kurkin, S.A.; Hramov, A.E.; Pisarchik, A.N. Event-related coherence in visual cortex and brain noise: A MEG study. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J.; Ruts, I.; Tukey, J.W. The bagplot: A bivariate boxplot. Am. Stat. 1999, 53, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukey, J.W. Mathematics and the picturing of data. In Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians; Canadian Mathematical Congress: Montreal, QC, Canada, 1975; pp. 523–531. [Google Scholar]

- Marquand, A.F.; Rezek, I.; Buitelaar, J.; Beckmann, C.F. Understanding heterogeneity in clinical cohorts using normative models: Beyond case-control studies. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 80, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Liu, K.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, F. Object detection based on an adaptive attention mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, M.; Ling, S.; Read, S. Attention alters appearance. Nat. Neurosci. 2004, 7, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, R.; Duncan, J. Neural mechanisms of selective visual attention. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 1995, 18, 193–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, M.I. Attention in cognitive neuroscience: An overview. In The Cognitive Neurosciences; Gazzaniga, M.S., Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 615–624. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, S.E.; Posner, M.I. The attention system of the human brain: 20 years after. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botvinick, M.M.; Braver, T.S.; Barch, D.M.; Carter, C.S.; Cohen, J.D. Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 108, 624–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, R.M.; Boehler, C.N.; Egner, T.; Woldorff, M.G. The neural underpinnings of how reward associations can both guide and misguide attention. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 9752–9759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbetta, M.; Shulman, G.L. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossel, S.; Geng, J.J.; Fink, G.R. Dorsal and ventral attention systems: Distinct neural circuits but collaborative roles. Neuroscientist 2014, 20, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzaley, A.; Nobre, A.C. Top-down modulation: Bridging selective attention and working memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2012, 16, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, B.; Chang, J.Y.; Postle, B.R.; Van Veen, B.D. Context-specific differences in fronto-parieto-occipital effective connectivity during short-term memory maintenance. NeuroImage 2015, 114, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapen, T.; Brascamp, J.; Pearson, J.; van Ee, R.; Blake, R. The role of frontal and parietal brain areas in bistable perception. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 10293–10301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karten, A.; Pantazatos, S.P.; Khalil, D.; Zhang, X.; Hirsch, J. Dynamic coupling between the lateral occipital-cortex, default-mode, and frontoparietal networks during bistable perception. Brain Connect. 2013, 3, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Sun, B.; Gao, Z. Brain areas activated by uncertain reward-based decision-making in healthy volunteers. Neural Regen. Res. 2013, 8, 3344–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassi, P.R.; Schauer, G.; Dwarakanath, A. The role of the occipital cortex in resolving perceptual ambiguity. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 10508–10509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Fukuda, K.; Woodman, G.F. Cross-frequency coupling of frontal theta and posterior alpha is unrelated to the fidelity of visual long-term memory encoding. Vis. Cogn. 2022, 30, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimesch, W.; Sauseng, P.; Hanslmayr, S. EEG alpha oscillations: The inhibition-timing hypothesis. Brain Res. Rev. 2007, 53, 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worden, M.S.; Foxe, J.J.; Wang, N.; Simpson, G.V. Anticipatory biasing of visuospatial attention indexed by retinotopically specific α-band electroencephalography increases over occipital cortex. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, RC63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capotosto, P.; Babiloni, C.; Romani, G.L.; Corbetta, M. Frontoparietal cortex controls spatial attention through modulation of anticipatory alpha rhythms. J. Neurosci. 2009, 18, 5863–5872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.