Abstract

The rising incidence of skin cancer necessitates the development of automated, reliable diagnostic tools to support clinicians. While deep learning models, particularly from the YOLO family, have shown promise, their application in real-world scenarios is limited by challenges such as class imbalance and the inability to process images of healthy skin, leading to potential false positives. This study presents a comprehensive comparative analysis of 32 object detection models, primarily from the YOLO architecture (v5–v12) and RT-DETR, to identify the most effective solution for skin lesion detection. We curated a novel, balanced dataset of 10,000 images based on the ISIC archive, comprising 10 distinct lesion classes (benign and malignant). Crucially, we introduced a dedicated ‘background’ class containing 1000 images of clear skin, a novelty designed to enhance model robustness in clinical practice. Models were systematically evaluated and filtered based on performance metrics (mAP, Recall) and complexity. Through a multi-stage evaluation, the YOLOv9c model was identified as the superior architecture, achieving a mAP@50 of 72.5% and a Recall of 71.6% across all classes. The model demonstrated strong performance, especially considering the dataset’s complexity with 10 classes and background images. Our research establishes a new benchmark for skin lesion detection. We demonstrate that including a ‘background’ class is a critical step towards creating clinically viable tools. The YOLOv9c model emerges as a powerful and efficient solution. To foster further research, our curated 10-class dataset with background images will be made publicly available.

1. Introduction

With ongoing global warming, the incidence of skin cancer is also increasing, becoming a growing problem affecting a larger part of the human population [1]. This problem arises because global warming causes a greater amount of UVA and UVB radiation to reach the Earth’s surface. Studies clearly indicate [2] that the amount of ultraviolet radiation affecting human skin is linked to the appearance of cancerous lesions. The World Health Organization (WHO) has officially recognized UV radiation as a carcinogen.

There are many types of skin lesions, including those that are harmful to life and health, as well as harmless ones that pose no health threat to the individual. The increase in skin cancer occurrence also leads to a growing demand for qualified dermatologists who can conduct examinations, make diagnoses, and recommend treatment. The earlier a cancerous lesion is detected, the greater the patient’s survival rate and chance of a full recovery [3,4,5]. A serious problem accompanying the rising trend of skin cancer occurrence is the insufficient number of qualified medical personnel available for patient consultations. Modern, rapidly developing technology, such as machine learning algorithms from the YOLO (You Only Look Once) family, offers a solution. These models can be used to create programs that support the work of dermatologists, making it possible to diagnose a larger number of patients more quickly and precisely.

Despite the rapid development of deep learning methods, previous research on automatic skin lesion diagnosis has certain limitations. First, most existing models are trained on datasets that do not include images of healthy skin, which makes it impossible for them to reliably distinguish between the presence and absence of a lesion. Second, there is a lack of comprehensive comparative analyses of the latest architectures, such as newer YOLO generations, which would help identify the most optimal solution. Finally, many studies focus on classification, ignoring the key diagnostic aspect of precise lesion location.

Consequently, the primary objective of this study is to perform a rigorous comparative analysis of 32 modern object detection architectures—specifically from the YOLOv5 to YOLOv12 families and RT-DETR—to identify the most robust solution for dermatological diagnostics. Unlike previous benchmarks, this study aims to bridge the gap between technical performance and clinical utility by evaluating models on a novel dataset that explicitly includes healthy skin images to mitigate false positives.

The main contributions and novelty of this work are as follows:

- Creation and public release of a novel, comprehensive dataset for skin lesion detection. The dataset is the first of its kind to include a dedicated and balanced ‘background’ class of 1000 healthy skin images, which is critical for training robust models that can minimize false positives in a real-world clinical setting.

- A large-scale benchmark of 32 state-of-the-art object detection models. This study provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of modern architectures, primarily from the YOLO family (v5–v12) and RT-DETR, establishing their true effectiveness on a challenging, multi-class medical imaging task.

- Development of a systematic, multi-stage evaluation methodology. An original approach to model selection was presented, which considers not only performance metrics like mAP and Recall but also computational complexity, ensuring that the recommended solution is both accurate and efficient for practical deployment.

- Introduction of a novel scoring system for model selection. To objectively identify the superior architecture, we developed a unique scoring system based on per-class recall performance, which allowed for a granular and fair comparison between the final candidate models.

- Establishing a new benchmark and identifying the best-performing model. Based on the rigorous analysis, the YOLOv9c model was identified as the most powerful and efficient solution. Its performance on our custom dataset establishes a new, more realistic benchmark for future research in automated dermatological diagnosis.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a review of related works in the field of skin lesion detection and classification. Section 3 describes the materials and methods used in this study, including the details of our novel dataset, the data preparation process, the evaluation metrics, and an overview of the YOLO architecture. Section 4 presents the multi-stage model evaluation and selection process, where we systematically narrow down the 32 initial models to the single best performer. Section 5 contains a detailed presentation of the results achieved by the selected YOLOv9c model and outlines future directions for this research. Finally, Section 6 provides a discussion of these results, compares them with the findings of other authors, and concludes the paper.

2. Related Works

To provide a rigorous context for our study, we conducted a targeted literature review of scientific articles published between 2019 and 2025. The search was performed using major academic databases, including IEEE Xplore, PubMed, and Google Scholar, utilizing keywords such as ‘skin lesion detection’, ‘YOLO’, ‘deep learning in dermatology’, and ‘object detection in medical imaging’. The primary objective of this review was threefold: (1) to identify the most prevalent deep learning architectures currently employed in dermatological diagnostics; (2) to analyze the composition and limitations of standard datasets; and (3) to pinpoint specific gaps in existing methodologies, particularly regarding the handling of healthy skin images and the comparative benchmarking of recent model generations. Most authors rely on public datasets like ISIC (International Skin Imaging Collaboration) or HAM10000 (Human Against Machine), although some use private or less common sets. It is worth noting that while authors using HAM10000 consistently include all 7 available classes, other researchers do not always use all classes from larger datasets.

Many contemporary works use the YOLO architecture for skin lesion detection and classification tasks. Aishwarya et al. applied YOLOv3 and YOLOv4 for classifying 9 classes from the ISIC dataset, achieving an mAP of 88.03% and 86.52%, respectively [6]. They noted that network speed is crucial in detection tasks. Nasser A AlSadhan et al. focused on detecting 3 classes from ISIC, testing YOLOv3, v4, v5, and v7 [7]. YOLOv7 proved to be the best model, achieving an mAP of 75.4% and an F1-Score of 80%. In a similar approach, Stefan Ćirković et al. used YOLOv8 to classify lesions on a balanced, private dataset [8]. This model achieved a precision of 78.2% and an F1-Score of 0.80. Munawar A Riyadi et al. applied YOLOv8n to detect and classify 9 classes from ISIC, with results for precision, recall, and F1-Score all at 93.5% [9]. Interestingly, Nayim A Dalawal et al. explored YOLOv8m for the real-time detection of 35 skin diseases from private datasets, achieving an mAP50-95 of just 0.0661, which highlights the scale and difficulty of the task [10].

Some researchers have chosen to enhance standard YOLO architectures. Manar Elshahawy et al. created a hybrid model combining YOLOv5 with ResNet50, achieving exceptionally high results on HAM10000 (99.0% precision, 98.7% mAP@0.5–0.95) [11]. Their system integrated detection and classification into a single stage. Other researchers focused on combining detection with segmentation. Takashi Nagaoka proposed a hybrid architecture called SAM-enhanced YOLO, which integrates the SAM model with YOLO, resulting in an F1-score of 0.833 [12]. A similar solution, YOLOSAMIC, was described by Sevda Gül et al., where YOLOv8 handles detection and SAM performs segmentation [13]. Their use of YOLOv8 on public databases yielded an mAP of 98.3%, providing a strong baseline for further analysis.

Many works have also investigated other deep learning architectures and innovative approaches. K. Aljohani et al. compared the performance of ResNet, VGG16, and SqueezeNet on the HAM10000 dataset, with SqueezeNet achieving the highest accuracy of 99.8% [14]. In a study by Salha M. Alzahrani, the SkinLiTE model achieved a high F1-Score of 0.9064 on the ISIC19 and ISIC2020 datasets [15]. In hybrid approaches, S. Oswalt Manoj et al. combined YOLOv3 with a DCNN and classic feature extraction methods, achieving 95% accuracy [16]. Abdullah Khan et al. developed the CAD-Skin system, which merges convolutional neural networks with Quantum Support Vector Machine (QSVM), achieving 98–99% accuracy on various datasets [17].

Some authors focused on optimizing specific processes. Fei Wang et al. introduced GRNet50, which used Geometric Algebra (GA) and an attention mechanism to reduce model parameters while achieving 98.5% accuracy [18]. Javed Rashid et al. used a transfer learning approach with the MobileNetV2 model for melanoma classification, achieving 98.2% accuracy and 98.1% F1-Score while minimizing computational costs [19]. Furthermore, Adekunle Ajiboye’s systematic review compared CNN and XGBoost models, finding that the latter performed better with an accuracy of 86.46% [20]. Finally, Rehan Ashraf demonstrated that using a Region of Interest (ROI) and the k-means algorithm significantly improved melanoma detection results, increasing recall and F1-Score by more than 20% on the DermQuest dataset [21].

The analysis of these works shows that while YOLO architectures are dominant, other methods still offer significant value. Innovative hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of different techniques represent a promising direction for research in skin lesion detection and classification.

Critically, a common limitation observed across the analyzed studies [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21] is the exclusive use of on datasets containing only pathological samples (e.g., ISIC, HAM10000). None of the reviewed works incorporated a dedicated class for healthy skin to test the model’s resistance to false positives in non-clinical settings. Furthermore, while individual newer architectures like YOLOv8 have been tested [8,9,10,21], there is a lack of a systematic benchmark comparing the full spectrum of recent YOLO iterations (v5 through v12) on a unified medical task. This study aims to address these specific gaps.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Dataset

The International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC) is a pioneering initiative that maintains a comprehensive, publicly available database of skin images to support research and the development of diagnostic technologies in dermatology. The dataset is notable for its diversity, including a wide variety of dermoscopic images of skin lesions, such as pigmented nevi, skin cancers (melanoma, basal cell carcinoma), and inflammatory conditions, often supplemented with detailed clinical documentation like patient history and diagnoses. To ensure high quality and reliability, data submission is restricted to qualified specialists, and all images undergo a rigorous expert verification process, adhering to strict ethical standards. As an open-access resource, the ISIC dataset is an invaluable tool for the scientific community, fostering innovation and enabling the development of advanced artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms for dermatological diagnostics.

3.2. Dataset Preparation

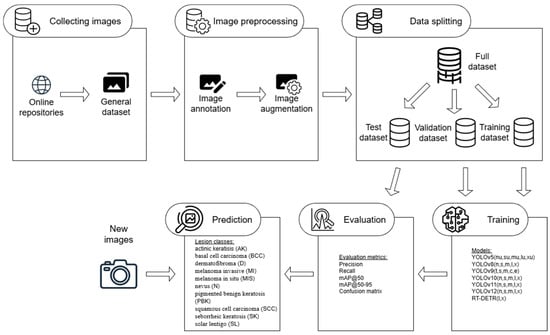

Every image chosen from the ISIC dataset was marked with bounding boxes using website computing vision tools from Roboflow company. Images were pre-labeled by licensed dermatologists and this way it was known what lesion contained the given image. Background images were obtained by cropping fragments of healthy skin without any lesions from skin images with high resolution. Background images often contain short hair from different body parts like legs or arms. Originally numbers of images per class varied from 662 to 1001. Therefore, classes dermatofibroma (662 images) and solar lentigo (711 images) were augmented using the Albumentations 1.3.1 library to increase the number of images from each class to 1000. The transformations performed during augmentation were SafeRotate and ShiftScaleRotate. The entire process flow of the research, including data collection, annotation, augmentation, and splitting, followed by model training and evaluation, is presented schematically in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The processes flow of the research performed.

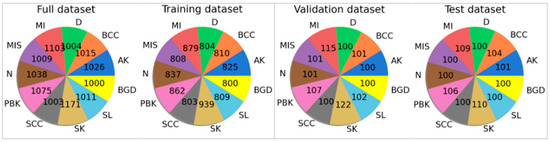

The dataset used consists of 10 classes, of which 5 represent images of harmful skin lesions, 5 represent harmless lesions, and 1000 background images. The benign classes are: PBK—pigmented benign keratosis, D—dermatofibroma, SL—solar lentigo, SK—seborrheic keratosis, N—nevus. The malignant classes are: MI—melanoma invasive, BCC—basal cell carcinoma, AK—actinic keratosis, MIS—melanoma in situ, SCC—squamous cell carcinoma. The class containing background images is labeled as BGD. The dataset containing background images is particularly important and necessary for the algorithm to know how to behave when a user provides a photo that does not contain any skin lesion, thereby adding to its reliability. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no previously published study on skin lesion detection has included this possibility. This is especially important considering the potential perspective of using the best model from this study to create a tool that could be used by regular users without medical education to be able to initially identify their own skin lesions. All classes contain between 1000 and 1103 photos and were divided into training, validation, and test subsets in proportions of 80–10–10%. The exact division of the sets is presented in Figure 2. The dataset was made available on the Zenodo platform (https://zenodo.org/records/17479143, assessed on 30 October 2025).

Figure 2.

The structure of the datasets used. The pie charts provide information on the number of skin lesions belonging to a specific class.

3.3. Metrics

Here are the basic terms needed to understand the formulas:

- TP (True Positives)—Cases where the model correctly predicted the positive class.

- TN (True Negatives)—Cases where the model correctly predicted the negative class.

- FP (False Positives)—Cases where the model incorrectly predicted the positive class (a false alarm).

- FN (False Negatives)—Cases where the model incorrectly predicted the negative class (an oversight or a miss).

- IoU is a value from 0 to 1 that measures how much the predicted bounding box overlaps with the actual bounding box (1). A higher IoU value means a better, more precise detection.

Average Precision (AP) is a metric used to evaluate models for object detection and balanced data classification. AP summarizes a model’s performance in a single number by combining both precision and recall. It is the area under the precision-recall curve. This curve shows how precision and recall change as the model’s confidence threshold is varied. The larger the area under this curve, the higher the AP value, which means the model is capable of achieving high precision at high recall.

mAP is the most important metric used to evaluate the performance of object detection models (2). It is a single number that gives a comprehensive view of how well a model detects objects. The AP is calculated for each class by averaging the precision at different recall levels. Then, the mAP is the average of the AP scores across all classes. This makes it a great metric for multi-class detection tasks, as it accounts for both precision and recall across every object type the model is trained to find.

The numbers at the end of the mAP metric (like @50 or @50–90) refer to the IoU threshold.

The mAP@50 calculates the mAP score with a fixed IoU threshold of 0.50. This means a prediction is considered correct only if its bounding box has an overlap of at least 50% with the ground truth box. This is a relatively lenient threshold and is used to quickly assess if a model can generally find the location of objects.

The mAP@50–90 calculates the mAP score by averaging the AP scores across multiple IoU thresholds, specifically from 0.50 to 0.95, in increments of 0.05. This is a much stricter and more robust metric. A prediction needs to be accurate not just in its classification but also in its precise location and size. A model that performs well on mAP@50–90 is strong across a range of precision levels, from a rough box to a perfectly fitted one.

The core difference between mAP@50 and mAP@50–90 is that mAP@50 is a good measure of whether a model can roughly locate an object, whereas mAP@50–90 is a much better measure of whether a model can precisely locate and size an object.

Recall tells how well the model finds all the objects it is supposed to find (3). Out of all the real objects in an image, how many did the model successfully detect. A high recall score means the model does not miss many objects.

Precision tells how accurate positive predictions are (4). Out of all the objects the model detected, how many were actually correct. A high precision score means the model does not generate many false alarms.

The F1 Score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall (5). It provides a balance between these two metrics, which makes it particularly useful for imbalanced datasets, where accuracy alone can be misleading. A high F1-Score indicates that the model has both high precision and high recall.

3.4. The YOLO Family of Models

While the YOLO family has evolved significantly since its inception [22,23], this study specifically evaluates versions v5, v8, v9, v10, v11, and v12 [24,25,26,27,28,29]. These architectures were selected to represent different stages of the algorithm’s evolution: from the established stability of YOLOv5, through the widely adopted YOLOv8, to the most recent experimental iterations (v11, v12).

A summary of the key innovations for the models used in this study is presented in Table 1. Older versions (v1–v4, v6–v7) have been omitted from detailed analysis as they have been largely superseded by the architectures tested herein [30,31,32,33,34].

Table 1.

Key characteristics of the YOLO architectures evaluated in this study.

Our primary focus is on identifying an architecture that balances the detection of minute lesion details with computational efficiency. While newer models like YOLOv10 and v12 introduce novel mechanisms (NMS-free inference and attention modules, respectively), YOLOv9 was selected as a primary candidate for optimization due to its unique Programmable Gradient Information (PGI) concept [26]. In medical imaging, where lesions (e.g., Melanoma in situ) often share subtle visual features with healthy skin, the problem of “information bottleneck” in deep networks is critical. YOLOv9’s ability to preserve deep feature information via PGI makes it theoretically superior for distinguishing between malignant and benign classes compared to purely speed-oriented architectures.

3.5. RT-DETR Architecture

RT-DETR (Real-Time DEtection TRansformer), developed by Baidu, represents a different paradigm in object detection compared to the YOLO family. While YOLO models are single-stage detectors that rely on dense predictions and require a Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) post-processing step, RT-DETR is a pioneering end-to-end, real-time architecture based on the Transformer framework. The core innovation of RT-DETR is its ability to eliminate the need for NMS, which simplifies the detection pipeline. It achieves this by treating object detection as a set prediction problem, drawing inspiration from the original DETR (DEtection TRansformer) model. The architecture uses a conventional CNN backbone (e.g., ResNet) to extract multi-scale feature maps, which are then fed into a key component: the Efficient Hybrid Encoder. This encoder efficiently processes the multi-scale features by decoupling intra-scale feature interaction and cross-scale feature fusion, building a rich feature representation without excessive computational cost. Subsequently, the Transformer Decoder receives a small, fixed set of object queries, which are refined through self-attention and cross-attention mechanisms to analyze the global context. Finally, the prediction heads map each refined query to a single prediction (a class label and a bounding box) in a one-to-one manner. During training, a Hungarian matching algorithm performs this one-to-one assignment between the model’s predictions and the ground truth objects. This end-to-end approach, which avoids the thousands of overlapping predictions generated by YOLO, is the primary differentiator. The model also introduces innovations like IoU-aware query selection to improve query initialization and supports flexible inference speed by adjusting the number of decoder layers without needing to be retrained [35].

4. Results

4.1. Training Progress

During the model training and testing processes the API provided by Ultralytics was used [36]. All models were pre-trained on the COCO dataset, which contains 80 object categories. A transfer learning technique was applied, through which the original weights were fine-tuned for 10 classes of skin lesions. To ensure result comparability, all models were trained using identical default hyperparameter values. In addition, this approach provided a compromise between training quality and speed. Table 2 provides a description and values of selected hyperparameters used during the model training process.

Table 2.

Selected hyperparameters used during the models training process.

In this study, 32 models were trained, with 30 belonging to the YOLO family and 2 to the RT-DETR family. A list of the models and their achieved results is presented in Table 3. Five versions were used for each of the following architectures: YOLOv5, YOLOv8, YOLOv9, YOLOv10, YOLOv11, and YOLOv12. For the RT-DETR architecture, we decided to use two model versions. It is important to define the differences between the individual model versions to better understand the results discussed in the next section. The construction of the models was carried out on the NVIDIA DGX A100 computing platform, the main components of which were as follows: CPU—Dual AMD Rome 7742, 256 cores, 1 TB; GPU—8 × NVIDIA A100 SXM4 80 GB Tensor Core; OS: Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS. The torch 2.3.0 platform and Python 3.10.12 programming language were used to build the models.

Table 3.

Performance metrics for all tested models.

The symbol ‘n’ stands for the “Nano” version of a model. It is the smallest and fastest variant. It has the lowest depth_multiple and width_multiple. It is ideal for real-time applications on edge devices, mobile phones, or embedded systems where computational resources and power are highly constrained, though with lower accuracy. The symbol ‘s’ stands for “Small” and is step up from nano, it is still very fast and efficient. It is a popular choice for many applications where a good balance of speed and decent accuracy is required. The symbol ‘m’ stands for “Medium” version which offers a better trade-off between speed and accuracy compared to the smaller variants. It is suitable for applications that require higher accuracy but still need reasonable inference speeds. The symbol ‘l’ stands for “Large” version and is larger and slower than the medium variant but provides significantly higher accuracy. It is often used when accuracy is a higher priority and computational resources are more abundant. The symbol ‘x’ stands for “Extra Large” version and is the largest and most accurate variant. It is the slowest but designed for applications where maximum detection performance is critical and substantial computational power (e.g., powerful GPUs) is available. Letter ‘u’ added to each version symbol for YOLOv5 architecture refers to “anchor-free” versions of these models. YOLOv9 architecture has different symbols for two of its versions. The symbol ‘t’ stands for “Tiny” and is the equivalent of “Nano” versions in other architectures from YOLO family. The symbol ‘c’ stands for “Compact” or “Conventional” and is equivalent of other models’ “Large” version.

4.2. Initial Performance Benchmark

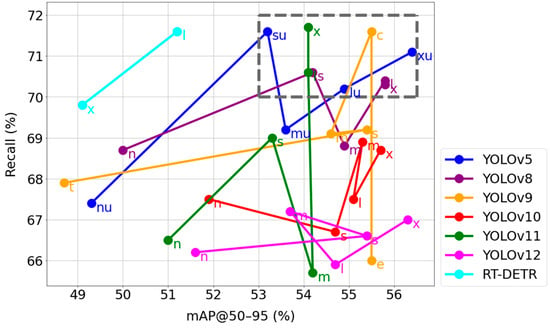

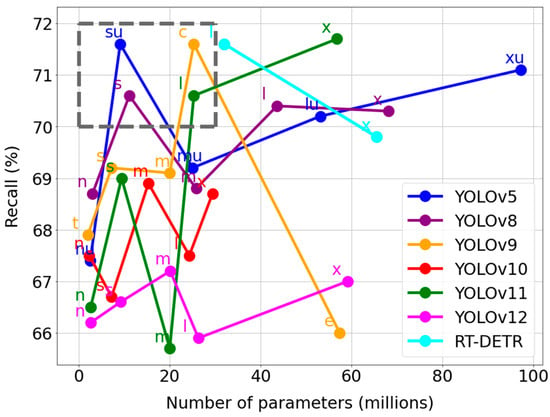

Table 3 shows performance of all trained models based on recall and mAP@50–95 metrics values for all skin lesion classes, as these metrics are the most important indicators in task of object detection. Each dot on a line represents a version of the respective model. Dots placed in the box on the top right side of the diagram represent versions of models with the higher scores in both metrics. These are YOLOv5su, YOLOv5lu, YOLOv5xu, YOLOv11l, YOLOv11x, YOLOv8s, YOLOv8l, YOLOv8x and YOLOv9c. Further research is based on the best models chosen from this diagram. Thus, models not placed in the box are disqualified. RT-DETR, YOLOv10 and YOLOv12 especially did not meet the expectations. RT-DETR has high recall but low mAP, whereas YOLOv10 and YOLOv12 both have low recall with high mAP.

The multi-stage selection procedure for the optimal model begins with an evaluation of key performance metrics that are fundamental to object detection tasks. Figure 3 presents a graphical comparative analysis of all 32 tested models, plotting their ability to detect existing lesions (Y-axis: Recall, %) against the precision of their localization (X-axis: mAP@50–95, %). In this metric space, the most desirable models are those positioned in the top-right corner of the plot, as they offer the best trade-off between high sensitivity and precision. Based on this analysis, a region was delineated (marked with a dashed line) that groups the models with the most balanced and promising characteristics. This initial filtering stage allowed for the selection of nine candidates for further, more detailed investigation: YOLOv5su, YOLOv5lu, YOLOv5xu, YOLOv8s, YOLOv8l, YOLOv8x, YOLOv9c, YOLOv11l, and YOLOv11x. Equally important was the rejection of architectures that did not meet these balanced criteria. For example, the RT-DETR models demonstrated high recall at the expense of low mAP, while the YOLOv10 and YOLOv12 models showed the opposite, equally undesirable, trend. This step was crucial for narrowing the analysis down to the models with the greatest practical potential, which will now be subjected to a detailed evaluation based on the metrics presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Recall and mAP@50–95 metrics values of built models for all classes together.

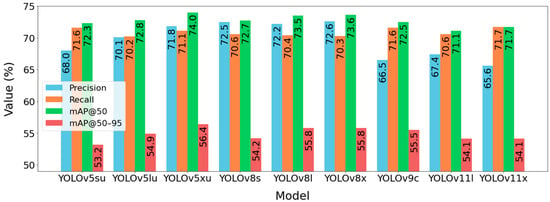

The detailed metrics for the nine selected models are presented in Figure 4. Overall, the YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 architectures demonstrated the strongest performance. YOLOv5xu achieved the highest overall mAP@50 (74.0%) and mAP@50–95 (56.4%). However, several other models showed competitive Recall scores, including YOLOv11x (71.7%), YOLOv5su (71.6%), and YOLOv9c (71.6%).

Figure 4.

Global evaluation metrics of models selected from Figure 3.

4.3. Efficiency-Based Selection

Following the detailed analysis of the performance metrics for the nine leading models, the next stage is to evaluate their computational efficiency, which is critical from the perspective of practical clinical implementation. Figure 5 illustrates the relationship between detection effectiveness (Y-axis: Recall, %) and model complexity, expressed in millions of parameters (X-axis). In this context, we aim to select models located in the top-left corner of the plot, which combine high performance with low complexity, thereby ensuring efficiency and a reduced demand for hardware resources. To perform an objective and systematic reduction in the number of candidates, a strict criterion was established: a model had to achieve a Recall of at least 70% while simultaneously having a parameter count not exceeding 30 million. The area that meets these conditions has been clearly marked on the plot with a dashed line. Applying this filter to the nine models qualified in the previous stage allowed for the selection of a final four that best balance high performance with low complexity. Thus, the models that qualified for the final comparative analysis were: YOLOv5su, YOLOv8s, YOLOv9c, and YOLOv11l.

Figure 5.

Global recall metrics and complexity of built models.

4.4. Per-Class Performance Analysis

We then compared the per-class Recall scores for the four remaining models (Figure 6). A general trend emerged where models performed significantly better on benign lesions (D, N, PBK, SL) than on malignant ones. However, the benign class SK proved challenging for all models (Recall 57.8–62.3%). Among malignant classes, MIS was detected most reliably (74.7–77.0%), while AK was the most difficult, with all models failing to reach 50% Recall (46.0–49.1%). This disparity highlights the challenge of detecting certain malignant lesions.

Figure 6.

Recall of detection of individual skin lesions by models selected from Figure 5.

4.5. Final Model Selection Using a Scoring System

Based on the recall results of the models for each lesion class, we decided to apply a scoring system to select the most effective model. For each lesion class, we will select the 2 models with the best recall score. The model with the highest score will receive 2 points, and the second in order will receive 1 point. Table 4 was developed in this way.

Table 4.

Established points system for models based on their performance.

The results presented in Table 5. clearly indicate that the YOLOv9c model is the most effective for both malignant and benign lesions, as it achieved the highest score in both of these categories.

Table 5.

Results of the scoring system: (a) Models with points obtained for malignant lesion classes. (b) Summarized points number for each model.

4.6. Results of the Best Model

The YOLOv9c model, selected through the multi-stage evaluation process, achieved an overall performance of 72.5% mAP@50 and 71.6% Recall, with a precision of 66.5% (Table 6). A notable disparity was observed in the model’s effectiveness between benign and malignant lesion classes.

Table 6.

YOLOv9c metrics scores.

Benign lesions were generally detected with higher accuracy. For instance, classes D (Dermatofibroma), N (Nevus), and PBK (Pigmented Benign Keratosis) consistently showed strong performance across all metrics, with PBK achieving the highest scores (Recall: 95.3%, mAP@50: 95.8%). Conversely, SK (Seborrheic Keratosis) proved more challenging within the benign group, obtaining a mAP@50 of only 64.2%.

The detection of malignant lesions presented significantly greater difficulty. While MIS (Melanoma in situ) achieved the highest recall among malignant classes (77.0%), the overall performance for this group was notably lower. The most problematic class was AK (Actinic Keratosis), which consistently underperformed across all metrics (Precision: 44.8%, Recall: 48.5%, mAP@50: 44.4%). This indicates that the visual features distinguishing AK were the most difficult for the model to learn effectively.

The localization accuracy, measured by mAP@50–95, was 55.5% overall. The significant drop from mAP@50 (72.5%) suggests that while the model is generally capable of locating lesions, the precision of the bounding box placement at higher IoU thresholds requires improvement. This trend is consistent across most classes, although localization accuracy is markedly better for benign lesions like PBK (80% mAP@50–95) compared to malignant ones like AK (27.5% mAP@50–95).

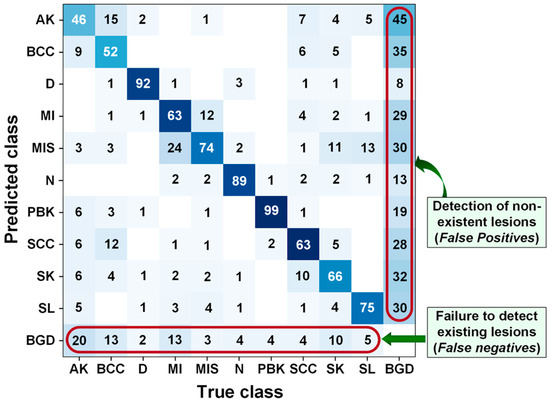

Figure 7 presents the confusion matrix with the errors made by the model. Starting with the AK class, the model detected and correctly classified the lesion in 46 cases, failed to detect it in 26 cases (marking it as background), and misclassified it in 35 cases. For the BCC lesion, the model correctly detected and classified it in 52 cases, marked it as background in 13 cases, and misclassified it in 39 cases. For the D lesion, the model correctly detected it in 92 cases, marked it as background in 2 cases, and misclassified it in 6 cases. The model correctly detected the MI lesion in 63 cases, detected a lesion in 13 images that did not contain one, and misclassified the lesion in 33 cases. For MIS, the model correctly detected the lesion in 74 images, did not detect a lesion in 3 images, and misclassified it in 23 images. For N, the model correctly detected the lesion in 89 images, marked 4 as background, and misclassified the lesion in 7 images. For PBK, the model correctly detected the lesion in 99 cases, failed to detect a lesion in 4 cases, and misclassified it in 3 cases. For SCC, the model correctly detected the lesion in 63 images, marked 4 images as BGD, and incorrectly classified 33 images. For the SK lesion, the model correctly detected it in 66 images, failed to detect it in 10 images, and misclassified it in 34. Finally, for the SL lesion, the model correctly detected it in 75 images, did not detect any lesion in 5, and misclassified 20 images. As we can see, the model performed best on the PBK lesion, detecting and correctly classifying it in 99 cases with 7 mistakes. It performed worst on the AK lesion, detecting it in only 46 cases with 55 mistakes.

Figure 7.

YOLOv9c model confusion matrix built for the test set.

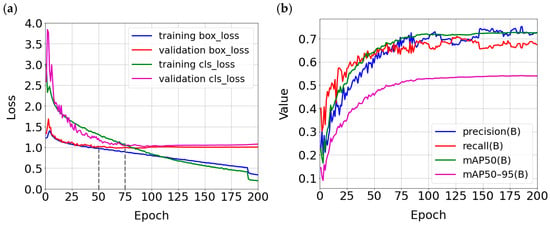

Figure 8a shows the detection and validation loss for the box, as well as the loss and validation for the classification of diseases. As we can see, the box validation loss decreases until epoch 50 and then does not change, so this is the optimal point for box detection. For classification, the validation loss decreases until epoch 75 and then slightly increases, so the most optimal number of epochs is 75. Figure 8b shows the values of individual metrics based on the number of epochs. The values of these metrics grow sharply until epoch 50, after which their rate of improvement slows slightly until epoch 75. After this number of epochs, the values no longer grow as quickly, so the best choice is 75 epochs.

Figure 8.

Plots of training and validation losses (a) and plots of basic detection quality metrics for the validation set (b) built for the YOLOv9c model.

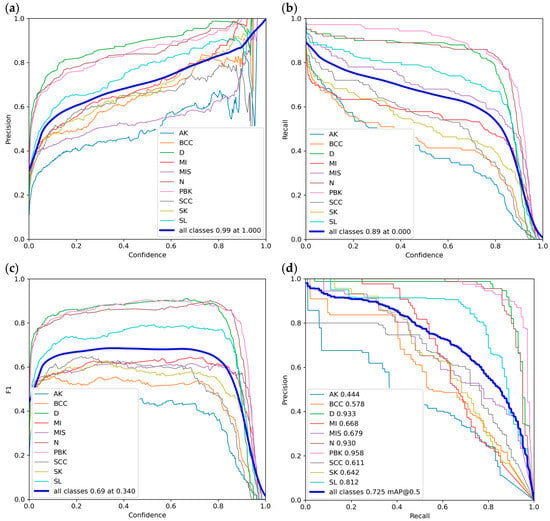

Figure 9a shows the change in precision based on confidence. As we can see, at a confidence threshold of 1.000, the model reaches a precision of 0.99 for all classes. This means that when the model is 100% certain, it has almost no false positives, but it also means that many objects will be missed. Figure 9b shows the change in recall based on confidence. At a threshold of 0.000, the model achieves a very high recall (0.89), which means it failed to indicate a skin lesion in only 11% of cases. However, this comes with a very large number of false positives because the model accepts all predictions, even uncertain ones. Figure 9c shows the change in F1 score based on confidence. As we can see, at a threshold of 0.340, the model gets an F1 score of 0.69, which means that at this point, the model achieves the best balance between recall and precision. Figure 9d shows the change in precision based on recall. And as we can see, the model achieved an mAP of 0.725 for all classes, assuming an IoU of 0.5.

Figure 9.

Plots of the YOLOv9c model detection quality metrics for the test set: (a) precision—confidence; (b) recall—confidence; (c) F1 score—confidence; (d) precision—recall.

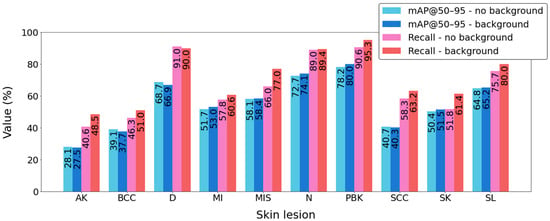

At the final stage of the research, the impact of background images on the obtained results was determined. For this purpose, the model considered to be the best (YOLOv9c) was trained without background images and then evaluated using the test set. During the evaluation, the same quality metrics were taken into account as in the previous analyses, namely mAP@90–95 and Recall. Regarding mAP@90–95, the use of background images caused a slight increase in this index, from 55.3% to 55.5%. A significant improvement, however, was observed in the case of Recall, which increased from 66.7% to 71.6% (an increase of 7.4%). Such a change is of considerable importance for patients from a medical standpoint. Figure 10 shows the impact of background images on mAP@90–95 and Recall for individual classes of skin lesions. Among the ten examined classes, as many as nine showed an increase in Recall after including background images.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the mAP@90–95 and Recall metrics of the YOLOv9c model depending on whether background images are included in the training process.

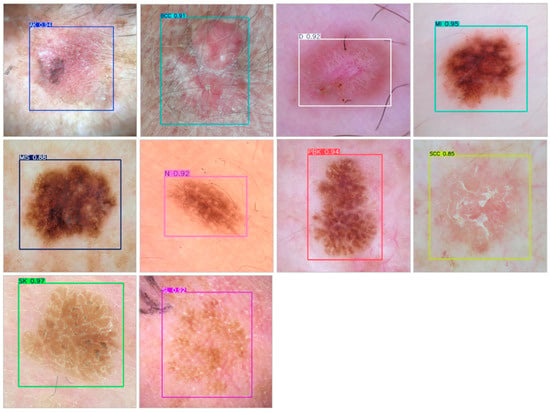

To provide a qualitative assessment of the YOLOv9c model’s performance, Figure 11. presents a selection of example images from the test set with their corresponding correct predictions. These examples were chosen to illustrate the model’s robustness across a variety of lesion classes and visual characteristics.

Figure 11.

Example results of correct skin lesion detection by the YOLOv9c model. The images subjected to prediction had different resolutions. To facilitate observation of the results, they were cropped with an aspect ratio of 1:1.

The model demonstrates high confidence in its predictions, with most scores exceeding 0.85. It successfully identifies lesions with well-defined, regular borders such as Melanoma Invasive (MI) and Melanoma in situ (MIS), as well as lesions with more ambiguous, textured, and irregular appearances, like Seborrheic Keratosis (SK) and Pigmented Benign Keratosis (PBK). Furthermore, the model proves effective in detecting lesions against diverse skin tones and textures, as seen in the examples for Nevus (N) and Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC). These visual results corroborate the strong quantitative metrics reported earlier, providing tangible evidence of the model’s capability to serve as a reliable diagnostic support tool.

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison of Results with Those of Other Authors

The performance of our YOLOv9c model was contextualized by comparing it with other relevant studies, as summarized in Table 7. A direct comparison of results is challenging due to significant variations in datasets, the number of classes, and the specific task (detection vs. classification). However, this broader analysis provides valuable insights into the performance of our model within the current landscape of dermatological AI research.

Table 7.

Comparison of our model results with results obtained by other authors.

When comparing our work to other detection studies, we observe that models trained on datasets with fewer classes or less complexity often report higher metrics. For instance, Elshahawy et al. and Gül et al. achieved outstanding mAP scores of over 98% using YOLOv5 and YOLOv8, respectively [11,13]. Similarly, Aishwarya et al. reported a high mAP of 86.52% on a 9-class subset of ISIC [6]. Our model’s mAP@50 of 72.5% may seem lower, but it is important to note that our task was significantly more complex, involving 10 distinct lesion classes plus a ‘background’ class designed to challenge the model under realistic conditions. Our result is highly competitive with that of AlSadhan et al., who achieved an mAP of 75.4% on a simpler 3-class detection task [7].

To provide a more comprehensive comparison, Table 7 also includes high-impact studies focused on classification, which report Precision and Recall metrics. Works by Aljohani & Turki and Rashid et al. demonstrate Precision scores exceeding 98% for classification tasks [14,19]. While our model’s primary goal is detection, its per-class precision for more distinct benign classes like Dermatofibroma (86.3%) and Pigmented Benign Keratosis (82.3%) is strong, though understandably lower for visually ambiguous malignant classes like Actinic Keratosis (44.8%).

In summary, while some studies report higher individual metrics, they often do so on less complex tasks (e.g., fewer classes, no background images, or classification instead of detection). Our work establishes a new, more realistic benchmark. The results demonstrate that the YOLOv9c model provides a robust and effective solution for the challenging, multi-class detection of skin lesions, especially when accounting for the added complexity and clinical necessity of correctly identifying healthy skin.

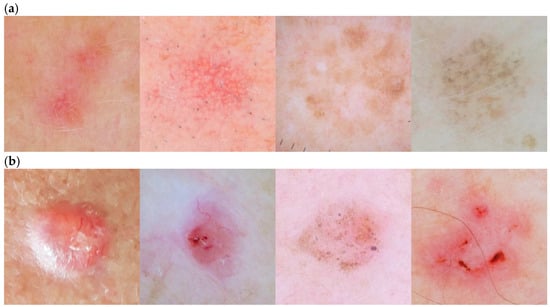

5.2. Possibilities for Improving the Model’s Effectiveness

The skin lesions with the poorest detection rates were Actinic Keratosis (Recall 48.5%) and Basal Cell Carcinoma (Recall 51%). A significant factor contributing to this issue was the large number of misclassifications of AK lesions as BCC (9 errors), as well as the even higher number of cases in which BCC lesions were incorrectly identified as AK (15 errors). This situation resulted from the fact that both lesion classes (AK and BCC) are visually very similar. This is clearly illustrated in Figure 12, which presents typical images of both aforementioned lesion types. AK cases most often appear as blurred, barely visible spots with irregular shapes, dominated by shades of red and brown. In contrast, BCC lesions are more distinct areas with relatively well-defined contours and coloration predominantly in shades of red.

Figure 12.

Typical images of the two most poorly detected skin lesions: (a) Actinic Keratosis; (b) Basal Cell Carcinoma.

In the course of further research, attempts will be made to improve the model’s effectiveness with respect to the analyzed cases. In the authors’ opinion, several courses of action are worth considering. In the first one, a characteristic feature of both classes of lesions—the high proportion of the color red in forming their appearance—can be leveraged. Applying appropriate filtering as part of the image preprocessing stage (before feeding the images into the network) could yield interesting results. The second option involves providing the model with a larger number of training images, which can be generated, for example, using augmentation or with the help of Generative Adversarial Networks. A greater number of examples belonging to the AK and BCC classes would enable more effective extraction of features characteristic of these classes. The third way to improve the model’s performance requires modifying the network architecture. In this approach, the feature maps from the last convolutional layer would be hybridized with feature descriptors derived from texture analysis in RGB mode by a dedicated image-analysis module. Fusing features from both sources could improve the recognition performance not only for the AK and BCC classes but also for other skin lesions. Regardless of the strategy chosen to improve the model’s performance, the issue raised is not trivial and requires separate, large-scale research efforts.

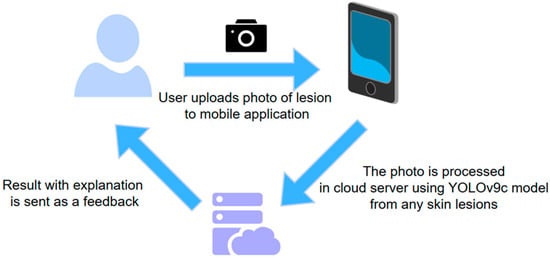

5.3. Future Directions

The findings of this benchmark study, particularly the development of a robust object detection model trained on a dataset that includes healthy skin images, have significant practical implications. This methodology moves beyond theoretical models towards clinical tools by ensuring the model can reliably distinguish between the presence and absence of a lesion. The inclusion of the ‘background’ class makes this model uniquely suitable for teledermatology and mobile health applications. The future direction would be developing smartphone-based application utilizing our chosen model that could enable patients to perform self-examinations and pre-screening. Crucially, by reliably identifying healthy skin, the application minimizes unnecessary patient anxiety and prevents the overload of medical facilities with false alarms—a common drawback of automated tools trained only on lesion images. In regions with limited access to specialized dermatological care, this technology could also serve as a vital, cost-effective screening tool. The application would be available for a broad variety of smartphone operating systems, allowing users to upload their photos. The photos would be sent and analyzed on a cloud server, then returned to a user with explanation. The workflow of the proposed application is depictured on Figure 13.

Figure 13.

The future application workflow.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we addressed the critical need for robust and reliable object detection models in dermatological diagnostics. While the existing literature has explored various deep learning architectures for skin lesion detection, our work introduces several key novelties. We conducted a comprehensive comparative analysis of 32 distinct models to identify the most promising candidates for this task. A primary contribution of our research is the creation and utilization of a novel and expanded dataset. We augmented a substantial collection of 10,000 skin lesion images from the ISIC archive with an additional 1000 images of clear, normal skin (background). This inclusion of negative samples is a critical step that, to our knowledge, has been overlooked in previous works. The presence of these background images is essential for training a model that can robustly differentiate between the presence and absence of a lesion, thereby preventing false positives and ensuring the model does not fail when presented with images of healthy skin. Through a rigorous evaluation process, we first narrowed our selection to the top four performing models. After applying a set of strict criteria, the YOLOv9c model was identified as the superior architecture, demonstrating a balance of high accuracy, precision, and efficiency. This model’s performance on our custom dataset establishes a new benchmark for object detection in this domain. Finally, to foster further research and collaboration within the scientific community, we will make our meticulously curated dataset publicly available on Kaggle. We believe that this accessible resource will serve as a valuable tool for future studies and contribute to the accelerated development of advanced dermatological diagnostic systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K. and Z.O.; methodology, Z.O.; software, N.K.; validation, N.K. and Z.O.; formal analysis, N.K. and Z.O.; investigation, N.K. and Z.O.; writing—original draft preparation, N.K.; writing—review and editing, N.K.; visualization, N.K.; supervision, Z.O.; project administration, Z.O.; funding acquisition, Z.O.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education and Science—Poland, grant number FD-20/EE-2/315.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17479143.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Urban, K.; Mehrmal, S.; Uppal, P.; Giesey, R.L.; Delost, G.R. The global burden of skin cancer: A longitudinal analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study, 1990–2017. JAAD Int. 2021, 2, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- World Health Organization. The Effect of Occupational Exposure to Solar Ultraviolet Radiation on Malignant Skin Melanoma and Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-Related Burden of Disease and Injury; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/350569 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Voss, R.K.; Woods, T.N.; Cromwell, K.D.; Nelson, K.C.; Cormier, J.N. Improving outcomes in patients with melanoma: Strategies to ensure an early diagnosis. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2015, 6, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Naik, P.P. Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma: A Review of Early Diagnosis and Management. World J. Oncol. 2021, 12, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Waseh, S.; Lee, J.B. Advances in melanoma: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and prognosis. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1268479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aishwarya, N.; Prabhakaran, K.M.; Debebe, F.T.; Reddy, M.S.S.A.; Pranavee, P. Skin Cancer diagnosis with Yolo Deep Neural Network. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 220, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSadhan, N.A.; Alamri, S.A.; Ben Ismail, M.M.; Bchir, O. Skin Cancer Recognition Using Unified Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Cancers 2024, 16, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stefan, Ć.; Nikola, S. Application of the YOLO algorithm for Medical Purposes in the Detection of Skin Cancer. In Proceedings of the 10th International Scientific Conference Technics, Informatics and Education-TIE 2024, Čačak, Serbia, 20–24 September 2024; pp. 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyadi, M.A.; Ayuningtias, A.; Isnanto, R.R. Detection and Classification of Skin Cancer Using YOLOv8n. In Proceedings of the 2024 11th International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Computer Science and Informatics (EECSI), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 26–27 September 2024; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalawai, N.; Prathamraj, P.; Dayananda, B.; Joythi, A.; Suresh, R. Real-Time Skin Disease Detection and Classification Using YOLOv8 Object Detection for Healthcare Diagnosis. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Anal. 2024, 7, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshahawy, M.; Elnemr, A.; Oproescu, M.; Schiopu, A.G.; Elgarayhi, A.; Elmogy, M.M.; Sallah, M. Early Melanoma Detection Based on a Hybrid YOLOv5 and ResNet Technique. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Takashi, N. Improved Skin Lesion Segmentation in Dermoscopic Images Using Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2025, 18, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gül, S.; Cetinel, G.; Aydin, B.M.; Akgün, D.; Öztaş Kara, R. YOLOSAMIC: A Hybrid Approach to Skin Cancer Segmentation with the Segment Anything Model and YOLOv8. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, K.; Turki, T. Automatic Classification of Melanoma Skin Cancer with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. AI 2022, 3, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, S.M. SkinLiTE: Lightweight Supervised Contrastive Learning Model for Enhanced Skin Lesion Detection and Disease Typification in Dermoscopic Images. Curr. Med. Imaging 2024, 20, e15734056313837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoj, S.O.; Abirami, K.R.; Victor, A.; Arya, M. Automatic Detection and Categorization of Skin Lesions for Early Diagnosis of Skin Cancer Using YOLO-v3-DCNN Architecture. Image Anal. Stereol. 2023, 42, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, K.; Muhammad, S.; Nauman, K.; Ayman, Y.; Qaisar, A. CAD-Skin: A Hybrid Convolutional Neural Network–Autoencoder Framework for Precise Detection and Classification of Skin Lesions and Cancer. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ju, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, H.; Qian, C.; Wang, R. A Geometric algebra-enhanced network for skin lesion detection with diagnostic prior. J. Supercomput. 2024, 81, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, J.; Ishfaq, M.; Ali, G.; Saeed, M.R.; Hussain, M.; Alkhalifah, T.; Alturise, F.; Samand, N. Skin Cancer Disease Detection Using Transfer Learning Technique. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekunle, A. Hybrid Skin Lesion Detection Integrating CNN and XGBoost for Accurate Diagnosis. J. Ski. Cancer 2025, 53, 14–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, R.; Afzal, S.; Rehman, A.U.; Gul, S.; Baber, J.; Bakhtyar, M.; Mehmood, I.; Song, O.-Y.; Maqsood, M. Region-of-Interest Based Transfer Learning Assisted Framework for Skin Cancer Detection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 147858–147871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R.; Santosh, D.; Ross, G.; Ali, F. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Pedro, F.; Ross, G.; David, M.; Deva, R. Object Detection with Discriminatively Trained Part-Based Models. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2010, 32, 1627–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahima, K.; Muhammad, H. What is YOLOv5: A deep look into the internal features of the popular object detector. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.20892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, D.; Kupec, J.; Hong, J.; Daoudi, A. Real-Time Flying Object Detection with YOLOv8. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.09972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Yeh, I.-H.; Liao, H.-Y. YOLOv9: Learning What You Want to Learn Using Programmable Gradient Information. In Proceedings of the 18th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. YOLOv10: Real-Time End-to-End Object Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv11: An Overview of the Key Architectural Enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. YOLOv12: Attention-Centric Real-Time Object Detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R.; Ali, F. YOLO9000: Better, Faster, Stronger. In Proceedings of the 30th IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 6517–6525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R.; Ali, F. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.-Y.; Liao, H. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A Single-Stage Object Detection Framework for Industrial Applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable Bag-of-Freebies Sets New State-of-the-Art for Real-Time Object Detectors. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, G.; Wei, J.; Cui, C.; Du, Y.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y. DETRs Beat YOLOs on Real-time Object Detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.08069. [Google Scholar]

- Ultralytics Homepage. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.