Abstract

Introduction: This systematic review evaluates the application of motion capture analysis (MCA) in assessing postoperative functional outcomes in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) patients treated with spinal fusion. Material and Methods: A comprehensive search of PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and Cochrane Library was conducted for studies published between January 2013 and September 2024. Eligible studies included original research examining AIS patients’ post-spinal fusion, specifically assessing kinematic outcomes via MCA. Key outcomes included gait parameters, range of motion (ROM), and trunk–pelvic kinematics. Results: Nine studies comprising 216 participants (81.5% female), predominantly with Lenke 1 and 3 curve types. MCA revealed significant improvements in gait symmetry, stride length, and trunk–pelvic kinematics within one year of surgery. Enhanced mediolateral stability and normalized transverse plane motion were commonly observed. However, persistent reductions in thoracic–pelvic ROM and flexibility highlight postoperative limitations. Redistributing mechanical loads to adjacent unfused segments raises concerns about long-term compensatory mechanisms and risks for adjacent segment degeneration. Conclusions: While spinal fusion effectively restores coronal and sagittal alignment and improves functional mobility, limitations in ROM and dynamic adaptability necessitate targeted rehabilitation. Future research should standardize MCA methodologies and explore motion-preserving surgical techniques to address residual functional deficits.

1. Introduction

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is a complex three-dimensional spinal deformity characterized by lateral curvature and axial rotation of the spine, with no identifiable etiology [1]. It affects approximately 1–3% of adolescents worldwide, with a higher prevalence in females, particularly during periods of rapid growth [2]. AIS can lead to cosmetic deformity, pain, psychological distress, and, in severe cases, respiratory and cardiac complications due to thoracic insufficiency [3,4]. Early detection and management are crucial to prevent curve progression and mitigate long-term adverse outcomes. Although the precise etiology of AIS remains unknown, current evidence suggests a multifactorial origin involving genetic predisposition, abnormal melatonin signaling, asymmetric growth modulation, and neuromuscular control dysfunction [5]. Genetic studies indicate that AIS may have a heritable component, with loci associated with scoliosis susceptibility identified in genome-wide association studies. Additionally, alterations in proprioception, vestibular function, and central nervous system processing have been hypothesized to contribute to the three-dimensional spinal deformity [6]. Furthermore, biomechanical theories suggest that asymmetric spinal loading and differential vertebral growth rates may influence the progression of scoliotic curves. These factors collectively contribute to the characteristic spinal rotation and lateral curvature observed in AIS patients. AIS predominantly affects females, with a female-to-male ratio of approximately 4:1 for curves requiring intervention. The severity of the condition is commonly assessed, with surgical intervention considered for major curves angles exceeding 45–50 degrees [2]. Conservative management, including bracing and physiotherapy, is generally recommended for mild-to-moderate cases, while spinal fusion remains the current standard for progressive and severe curves. Modern diagnostic modalities, such as EOS low-dose stereoradiographic imaging, allow for three-dimensional assessment of spinal deformities while minimizing radiation exposure. Functional evaluation, including MCA and gait analysis, is increasingly used to complement radiographic findings and provide dynamic insights into the biomechanical impact of AIS and its surgical correction [7].

Surgical intervention is often indicated for patients with severe curvature, typically those with major curve angles exceeding 45–50 degrees, to halt progression, correct deformity, and improve quality of life [8,9]. Advances in surgical techniques, such as segmental spinal instrumentation (SSI), primarily using pedicle screws, have significantly enhanced the ability to achieve optimal coronal and sagittal plane correction [10]. However, achieving satisfactory radiographic outcomes does not necessarily correlate with the restoration of normal functional abilities or improvements in daily activities [11]. Therefore, assessing postoperative functional outcomes has become increasingly important to fully understand the impact of surgical interventions on patients’ lives.

Motion capture analysis (MCA) is a sophisticated biomechanical tool that quantitatively evaluates human movement by tracking markers placed on anatomical landmarks [12]. These markers are recorded by high-speed infrared cameras, allowing for three-dimensional reconstruction of movement patterns. MCA provides kinematic parameters such as joint angles, range of motion, and spatiotemporal gait characteristics, while kinetic analysis (if integrated with force plates) assesses ground reaction forces and joint moments. In AIS patients, MCA can offer valuable insights into how spinal deformities and their surgical correction affect movement dynamics [13,14].

Previous studies have utilized MCA to assess gait abnormalities in AIS patients, revealing alterations such as reduced pelvic rotation, asymmetrical step lengths, and compensatory mechanisms to maintain balance [15,16]. For instance, AIS patients exhibit significant differences in lower limb kinematics compared to healthy controls, highlighting the impact of spinal deformity on gait [17,18]. Postoperatively, some studies have reported improvements in gait parameters, while others have noted persistent abnormalities despite surgical correction [17,18]. However, the application of MCA in evaluating postoperative outcomes remains underexplored, and existing studies often have small sample sizes and varying methodologies [18,19].

For several reasons, a comprehensive systematic review of the current evidence on the use of MCA in surgically treated AIS patients is warranted. First, it can synthesize available data to provide a clearer understanding of postoperative functional outcomes, which is essential for optimizing rehabilitation protocols and enhancing surgical techniques [20]. Second, identifying gaps in the literature can guide future research efforts to address unresolved questions. Finally, given the global prevalence of AIS and the widespread adoption of surgical interventions, this review can offer valuable insights for an international audience. It can facilitate the exchange of knowledge across different healthcare systems and cultural contexts, ultimately contributing to improved patient care worldwide [21,22].

This systematic review aims to evaluate the current evidence on motion capture analysis in surgically treated adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients. By synthesizing available data, we seek to determine how MCA has been utilized to assess postoperative functional outcomes, identify patterns and discrepancies in findings, and highlight areas for future research.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

This systematic review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Eligible studies included those examining adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) patients who underwent surgical correction, specifically spinal fusion, and assessed postoperative functional outcomes exclusively through motion capture analysis (MCA). Only original research, such as clinical trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies, published in English between January 2013 and September 2024, were included. Only studies with a minimum follow-up of one year postoperatively were included to ensure adequate assessment of functional recovery. While gender-specific and severity-based subgroup analyses would be valuable, inconsistencies in data reporting across studies limited our ability to conduct such comparisons. Exclusions encompassed non-original research, case reports, and studies lacking MCA-based outcome data.

2.2. Information Sources

A comprehensive search was performed across four databases: PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and the Cochrane Library. The final search was conducted in December 2024. Additional relevant records were identified through reference lists of included studies to ensure a thorough literature capture.

2.3. Search Strategy

Search terms targeted AIS, surgical interventions like spinal fusion, and motion capture analysis. Search strategies for each database incorporated a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords to ensure precision and comprehensiveness. Filters limited results to studies on human subjects published in English and within the specified date range. Complete search strings are detailed in Appendix A.

2.4. Study Selection

Two independent reviewers (both orthopedic surgeons specializing in spinal deformities) screened all studies for inclusion. Both reviewers had prior experience with motion analysis methodologies and AIS research. In cases of disagreement, a senior researcher with expertise in scoliosis biomechanics adjudicated the decision.

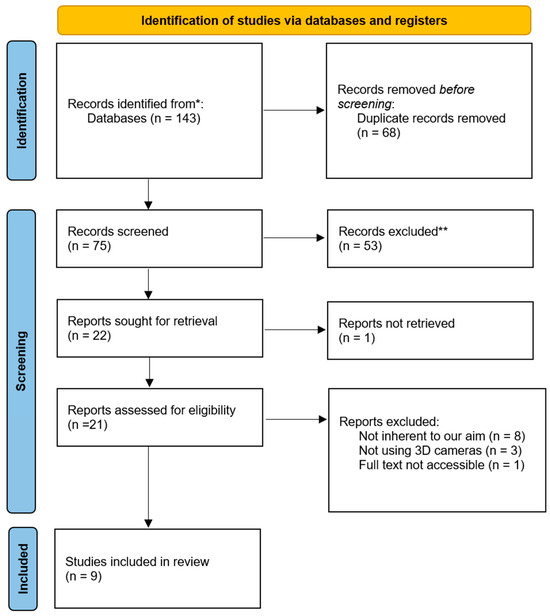

Two full texts were obtained for studies that met initial criteria or appeared eligible upon abstract review. A PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the study selection process and exclusion reasons at each stage (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

2.5. Data Collection Process

Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers using a standardized form. Extracted information included study characteristics (authors, year, design), participant demographics, surgical intervention specifics, MCA protocols, and outcome measures. Each data entry was cross-verified by a second reviewer to ensure accuracy and completeness.

2.6. Data Items

Primary outcomes were MCA-derived kinematic parameters related to postoperative functional performance, focusing on parameters like joint angles, range of motion, and symmetry in dynamic movement. Secondary data items included participant demographics, surgical intervention characteristics, and follow-up duration. Assumptions were minimized and based solely on details explicitly reported in each study.

2.7. Risk of Bias Assessment

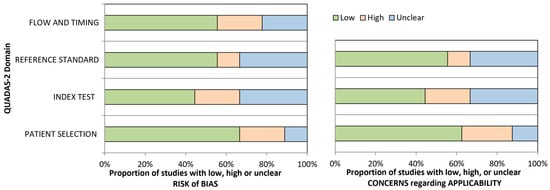

The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) tool, chosen for its suitability in assessing diagnostic accuracy and reliability in studies involving motion capture analysis [23]. Two reviewers independently evaluated each study across four key domains: patient selection, execution of the motion capture test, reference standards, and timing and flow of data collection. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through consensus. Studies were categorized by their risk of bias level, as summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

QUADAS-2 Risk of Bias.

2.8. Summary Measures and Data Synthesis

The primary summary measure focused on differences in kinematic parameters captured by MCA pre-and post-surgery. Outcomes were summarized as mean differences or percentages where applicable. Due to the included studies’ heterogeneity, it was impossible to perform a meta-analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics and Design

A total of nine studies were considered eligible for this systematic review. The included studies predominantly consisted of prospective cohort studies (n = 6) and cross-sectional comparative studies (n = 3), with an overall mean level of evidence of II. No randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were identified in the current literature. A summary of the levels of evidence for each included study is provided in Table 1. A total of 216 patients were included across nine studies, with a mean sample size of 23 ± 9 participants per study (range: 14–44). They were mostly females (81.5%). Studies primarily assessed Lenke types 1 and 3 curves, though subtypes varied. Three cross-sectional studies and six prospective studies were included. Study characteristics are resumed in 1. The analysis of motion capture data revealed consistent patterns in postoperative functional improvements and residual limitations, which are categorized below.

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

3.2. Motion Capture Timing

Preoperative MCA assessments were conducted in the majority of included studies. MCA characteristics were reported in Table 2. These evaluations revealed characteristic AIS-related gait deviations, including reduced pelvic rotation, asymmetrical step lengths, and altered trunk–pelvic coordination. Postoperatively, MCA demonstrated significant improvements in these parameters, although residual limitations in thoracic–pelvic range of motion persisted. Measurements were taken preoperatively and at follow-ups ranging from 3 months to 2 years, with most studies conducting final evaluations around 12 months. Vicon motion capture systems were the most employed technology, with marker sets ranging from 23 to 56 retro-reflective markers. Study variables and results are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 2.

Mocap characteristics.

Table 3.

Study variables and quantitative results.

Table 4.

Study qualitative results and conclusions.

3.3. Spatiotemporal Gait Parameters and Symmetry

Postoperative MCA demonstrated consistent improvements in gait symmetry among AIS patients following spinal fusion. Several studies reported increased stride length and normalized step cadence within one year post-surgery [27]. Gait speed, a frequently assessed parameter, also showed a tendency to improve, with some studies indicating a return to near-normal levels compared to age-matched healthy controls [24].

In contrast, sagittal pelvic mobility remained reduced postoperatively (mean reduction: 10–15%, p < 0.05), suggesting persistent limitations in dynamic adaptability despite improved coronal and sagittal plane alignment [24]. Additionally, pelvic tilt and obliquity alterations persisted in some patients, particularly in cases of asymmetric spinal fusion constructs.

3.4. Trunk–Pelvic Coordination and Range of Motion (ROM)

AIS patients exhibited postoperative improvements in mediolateral stability, with studies reporting a significant reduction in center of mass (COM) displacement by 30–40% (p < 0.001), indicating improved balance and weight distribution [26]. However, transverse plane motion remained compromised, with a 10–15% persistent reduction in thoracic–pelvic ROM compared to controls [27,28].

Notably, trunk rotation abnormalities seen preoperatively improved post-surgery but did not fully normalize in all cases. One study highlighted that trunk transverse ROM decreased from 9.6° to 7.5° postoperatively (p < 0.001), reinforcing the notion that spinal fusion inherently limits axial rotation [29], potentially affecting sports performance and activities requiring trunk mobility [30].

3.5. Postoperative Compensatory Mechanisms and Adjacent Segment Biomechanics

One of the key concerns in post-fusion AIS patients is the potential for compensatory adaptations in adjacent, unfused spinal segments. While the studies in this review did not directly measure adjacent segment disease (ASD), motion capture data revealed no significant compensatory mechanisms in lower limb kinematics (hip, knee, ankle) in response to reduced thoracic–pelvic mobility [29].

However, an increased reliance on lumbar and pelvic movements to compensate for restricted thoracic mobility was noted in certain studies, with some patients demonstrating higher-than-expected sagittal pelvic rotation, particularly at faster walking speeds. These findings suggest that while spinal fusion improves global postural alignment, adjacent segment function and long-term adaptations warrant further investigation [30].

3.6. Respiratory Function and Thoracic Expansion

Only Xun et al. assessed thoracic kinematics during respiration, but available data indicated that thoracic expansion improved postoperatively by 25–30% compared to untreated AIS patients [31]. This suggests that spinal fusion may have a positive impact on respiratory mechanics, particularly in patients with preoperative restrictive lung patterns.

3.7. Summary of Findings and Clinical Implications

The findings of this systematic review reinforce the efficacy of spinal fusion in restoring coronal and sagittal alignment and improving gait mechanics in AIS patients. However, limitations in transverse plane mobility and thoracic–pelvic coordination persist, raising important considerations for long-term functional adaptations and rehabilitation strategies.

3.8. Risk of Bias

The risk of bias across studies was assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool, covering four key domains: Patient Selection, Index Test, Reference Standard, and Flow and Timing. Overall, studies demonstrated low-to-moderate risk, with some notable areas of concern:

- Patient Selection: Most studies had low risk and high applicability regarding patient selection, reflecting the target population of adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis undergoing spinal fusion. However, two studies presented a high risk of bias due to selection methods that may limit generalizability.

- Index Test: Motion capture protocols were generally consistent, showing low risk and good applicability. Nonetheless, a few studies showed moderate risk and uncertain applicability due to variations in data acquisition protocols, impacting comparability.

- Reference Standard: The majority adhered to valid reference standards for assessing postoperative functional outcomes, yielding low bias and high applicability. However, some studies showed unclear applicability due to variations in the criteria used for outcome classification, which could affect uniformity in results interpretation.

- Flow and Timing: This domain exhibited the most significant variability, with specific studies rated as high risk due to incomplete follow-up or inconsistent assessment timing, potentially impacting longitudinal robustness.

The majority of studies demonstrated moderate methodological quality based on the QUADAS-2 assessment, with limitations primarily related to sample size heterogeneity, standardization of MCA protocols, and variations in follow-up duration.

4. Discussion

This systematic review synthesizes current evidence on the use of MCA in evaluating functional outcomes following spinal fusion for AIS. While significant progress has been made in correcting spinal deformity and restoring biomechanical symmetry, our findings illuminate critical areas where surgical outcomes could be optimized further. MCA provides an objective, high-resolution assessment of postoperative functional recovery in AIS patients, allowing for quantification of gait symmetry, trunk–pelvic kinematics, and joint range of motion. Compared to radiographic methods such as EOS imaging [7], MCA offers a functional, real-time evaluation without ionizing radiation. However, it does not provide direct structural measurements of spinal alignment and relies on external markers that may introduce variability due to soft tissue artifacts. Other functional assessment tools, such as three-dimensional gait analysis with force platforms, provide ground reaction force data but lack the detailed joint kinematics offered by MCA [26]. Similarly, sEMG allows for the assessment of muscle activation patterns, which can complement MCA findings but does not provide a full biomechanical profile of post-surgical adaptations [32]. The integration of MCA with these complementary modalities may enhance the precision of postoperative functional assessment in AIS patients.

4.1. Functional Gait Restoration: Achievements and Limitations

MCA studies have consistently highlighted significant gait symmetry and stability improvements following spinal fusion. Delpierre et al. [27] and Nishida et al. [33] demonstrated enhancements in stride length, mediolateral stability, and pelvic and trunk kinematics within one year of surgery. These findings suggest that surgical realignment effectively addresses preoperative biomechanical asymmetries, enabling structural corrections and adaptive neuromuscular adjustments in the lower limbs.

Nevertheless, not all aspects of gait return to normal levels. Persistent deficits in sagittal plane motion and restricted thoracic–pelvic mobility have been documented by Holewijn et al. [28] and Wong-Chung et al. [27]. Such limitations may arise from the inherent rigidity of fused spinal segments, which constrain global spine mobility. These findings underline the need for further research into compensatory adaptations in unfused spinal segments and adjacent musculoskeletal regions to better understand their role in mitigating functional deficits.

4.2. Respiratory Function and Thoracic Mechanics

Beyond kinematic outcomes, thoracic cage function is crucial in overall quality of life post-surgery. As shown by Xun et al., improvements in thoracic expansion during deep and quiet breathing represent a significant advancement for AIS patients undergoing fusion [31]. These findings are clinically relevant, given the association between severe scoliosis and restrictive lung disease. However, reduced flexibility in fused segments may pose limitations in adapting to physical activities requiring dynamic thoracic mobility, such as aerobic sports or high-intensity exercise.

4.3. Postoperative ROM and Adjacent Segment Biomechanics

An essential concern following spinal fusion is the redistribution of mechanical loads to adjacent unfused segments, as reduced transverse thoracic–pelvic ROM may lead to compensatory hypermobility. This adaptation, noted in studies like Holewijn et al., raises the risk of adjacent segment disease (ASD), which can manifest as pain, instability, or deformity over time [28]. Moreover, these limitations directly impact dynamic movements such as bending, twisting, or rapid directional changes, which are crucial for functional independence and physical activities, particularly in adolescents. The altered biomechanics of the spine can also affect the pelvis and lower limb joints, potentially disrupting gait patterns and increasing the risk of overuse injuries in the hips and knees. Rehabilitation strategies should prioritize flexibility and core stabilization while addressing potential imbalances across the kinetic chain. Longitudinal assessments, combined with advancements in surgical techniques such as hybrid constructs or motion-preserving devices, may offer solutions to reduce the burden on adjacent segments while maintaining effective deformity correction [33].

These insights highlight the need for a multidisciplinary approach to mitigate long-term biomechanical challenges and optimize overall functional outcomes.

4.4. Rehabilitation as a Cornerstone of Functional Recovery

Rehabilitation strategies are pivotal in addressing these postoperative limitations. The early implementation of targeted physical therapy programs focusing on core stabilization, flexibility, and proprioceptive training can significantly enhance recovery trajectories. Notably, Wong-Chung et al. reported that early rehabilitation efforts correlated with rapid improvements in trunk and pelvic symmetry [30]. Targeted rehabilitation should focus on improving core stability, proprioception, and flexibility to compensate for the restricted range of motion following spinal fusion. Strengthening exercises targeting deep spinal stabilizers (e.g., multifidus, transverse abdominis) may enhance postural control, while proprioceptive training can improve neuromuscular coordination [34]. Additionally, controlled mobility exercises, such as dynamic stretching and aquatic therapy, may help preserve thoracic and pelvic mobility without overloading adjacent spinal segments. Future research should explore the efficacy of rehabilitation programs tailored to specific MCA findings

4.5. Quality of Life and Psychosocial Considerations

While biomechanical outcomes are critical, the broader impact of spinal fusion on psychosocial well-being warrants further exploration. Studies have shown that functional improvements do not always align with patient-reported outcomes, such as satisfaction, body image, or emotional well-being. Integrating validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) into future MCA studies could provide a holistic view of surgical benefits, bridging the gap between objective biomechanical metrics and subjective patient experiences.

5. Study Limitations

The present study has several limitations. Most studies focused on short- to medium-term outcomes, with few evaluating long-term functional changes or complications, such as adjacent segment degeneration. Secondly, the heterogeneity in methodologies, including varying marker placements and motion capture protocols, limits the comparability of results across studies, making it not possible to perform a meta-analysis. Standardizing assessment protocols would enhance the reliability and generalizability of findings.

6. Conclusions

This review highlights the effectiveness of spinal fusion in improving gait symmetry and trunk kinematics in AIS patients. Despite these benefits, limitations in postoperative ROM and compensatory adaptations in adjacent segments remain as concerns. Advancements in surgical techniques are essential to optimize outcomes. Future research should focus on standardizing methodologies and integrating patient-reported outcomes to enhance care and quality of life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.B. and S.D.S.; data curation, P.B., S.D.S. and D.P.; formal analysis, P.B.; methodology, S.S., P.B., S.D.S. and D.P.; supervision, L.O. and P.F.C.; validation, P.F.C.; visualization, L.U.G.; writing—original draft, P.B. and S.D.S.; writing—review and editing, P.B. and S.D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AIS | Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis |

| ASD | Adjacent Segment Disease |

| COM | Center of Mass |

| MCA | Motion Capture Analysis |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROMs | Patient-Reported Outcome Measures |

| QUADAS-2 | Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 |

| ROM | Range of Motion |

Appendix A. Search String

Pubmed

(((“Scoliosis”[MeSH Terms] AND “Adolescent”[MeSH Terms]) OR “adolescent idiopathic scoliosis”[All Fields] OR “AIS”[All Fields]) AND (“Spinal Fusion”[MeSH Terms] OR “surgery”[MeSH Subheading] OR “surgical treatment”[All Fields] OR “operative treatment”[All Fields]) AND (“Biomechanical Phenomena”[MeSH Terms] OR “Gait Analysis”[MeSH Terms] OR “Motion Capture”[All Fields] OR “kinematic analysis”[All Fields] OR “movement analysis”[All Fields])) AND (2013:2024[pdat])

Scopus

(TITLE-ABS-KEY(“adolescent idiopathic scoliosis” OR AIS) AND

TITLE-ABS-KEY(“surgical treatment” OR surgery OR “spinal fusion” OR “surgical correction” OR “operative treatment”) AND

TITLE-ABS-KEY(“motion capture analysis” OR “motion analysis” OR “gait analysis” OR “biomechanical analysis” OR “kinematic analysis” OR “movement analysis” OR “3D analysis” OR “three-dimensional analysis”))

AND PUBYEAR > 2012

AND (LIMIT-TO(LANGUAGE, “English”))

AND (LIMIT-TO(DOCTYPE, “ar”))

Embase

(’adolescent idiopathic scoliosis’/exp OR ’AIS’ OR ’scoliosis’/exp) AND

(’surgical procedure’/exp OR surgery OR ’spinal fusion’/exp OR ’surgical correction’ OR ’operative treatment’) AND

(’biomechanics’/exp OR ’gait analysis’/exp OR ’motion capture analysis’ OR ’kinematic analysis’ OR ’movement analysis’ OR ’three dimensional analysis’) AND

[Shields, #1614]/lim AND

[humans]/lim AND

[2013–2024]/py

Cochrane Library

[adolescent idiopathic scoliosis OR AIS OR scoliosis]:ti,ab,kw AND

[surgical treatment OR surgery OR spinal fusion OR “surgical correction” OR “operative treatment”]:ti,ab,kw AND

[“motion capture analysis” OR “motion analysis” OR “gait analysis” OR “biomechanical analysis” OR “kinematic analysis” OR “movement analysis” OR “three dimensional analysis”]:ti,ab,kw

WITH Publication Year from 2013 to 2024, in Trials, in English

References

- Konieczny, M.R.; Senyurt, H.; Krauspe, R. Epidemiology of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Child. Orthop. 2013, 7, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, S.L.; Dolan, L.A.; Wright, J.G.; Dobbs, M.B. Effects of bracing in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1512–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrini, S.; Donzelli, S.; Aulisa, A.G.; Czaprowski, D.; Schreiber, S.; de Mauroy, J.C.; Diers, H.; Grivas, T.B.; Knott, P.; Kotwicki, T.; et al. 2016 SOSORT guidelines: Orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2018, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reamy, B.V.; Slakey, J.B. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Review and current concepts. Am. Fam. Physician 2001, 64, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Salvatore, S.; Ruzzini, L.; Longo, U.G.; Marino, M.; Greco, A.; Piergentili, I.; Costici, P.F.; Denaro, V. Exploring the association between specific genes and the onset of idiopathic scoliosis: A systematic review. BMC Med. Genom. 2022, 15, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, S.R.; Qiu, G.X.; Zhang, J.G.; Zhuang, Q.Y. Research progress on the etiology and pathogenesis of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Chin. Med. J. 2020, 133, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courvoisier, A.; Vialle, R.; Skalli, W. EOS 3D Imaging: Assessing the impact of brace treatment in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2014, 11, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.S. Evidence-based of nonoperative treatment in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Asian Spine J. 2014, 8, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.; Brenneis, M.; Schönnagel, L.; Caffard, T.; Diaremes, P. Surgical Treatment of Spinal Deformities in Pediatric Orthopedic Patients. Life 2023, 13, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonner, B.S.; Ren, Y.; Bess, S.; Kelly, M.; Kim, H.J.; Yaszay, B.; Lafage, V.; Marks, M.; Miyanji, F.; Shaffrey, C.I.; et al. Surgery for the Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Patients After Skeletal Maturity: Early Versus Late Surgery. Spine Deform. 2019, 7, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuartas, E.; Rasouli, A.; O’Brien, M.; Shufflebarger, H.L. Use of all-pedicle-screw constructs in the treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2009, 17, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, R.; McGinley, J.L.; Schwartz, M.H.; Beynon, S.; Rozumalski, A.; Graham, H.K.; Tirosh, O. The gait profile score and movement analysis profile. Gait Posture 2009, 30, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, K.M.; Garman, C.M.R.; Krzak, J.J.; Graf, A.; Hassani, S.; Tarima, S.; Sturm, P.F.; Hammerberg, K.W.; Gupta, P.; Harris, G.F. Effects of Spinal Fusion for Idiopathic Scoliosis on Lower Body Kinematics During Gait. Spine Deform. 2018, 6, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramers-de Quervain, I.A.; Müller, R.; Stacoff, A.; Grob, D.; Stüssi, E. Gait analysis in patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 2004, 13, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahaudens, P.; Banse, X.; Mousny, M.; Detrembleur, C. Gait in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Kinematics and electromyographic analysis. Eur. Spine J. 2009, 18, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudoin, L.; Zabjek, K.F.; Leroux, M.A.; Coillard, C.; Rivard, C.H. Acute systematic and variable postural adaptations induced by an orthopaedic shoe lift in control subjects. Eur. Spine J. 1999, 8, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Fischer, C.R.; Kim, Y. Selective fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A review of current operative strategy. Eur. Spine J. 2011, 20, 1048–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaudens, P.; Dalemans, F.; Banse, X.; Mousny, M.; Cartiaux, O.; Detrembleur, C. Gait in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Effect of surgery at 10 years of follow-up. Gait Posture 2018, 61, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopf, C.; Scheidecker, M.; Steffan, K.; Bodem, F.; Eysel, P. Gait analysis in idiopathic scoliosis before and after surgery: A comparison of the pre- and postoperative muscle activation pattern. Eur. Spine J. 1998, 7, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Watanabe, H.; Goto, R.; Tanaka, N.; Matsumura, A.; Yanagi, H. Effects of gait training using the Hybrid Assistive Limb® in recovery-phase stroke patients: A 2-month follow-up, randomized, controlled study. NeuroRehabilitation 2017, 40, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mohrej, O.A.; Aldakhil, S.S.; Al-Rabiah, M.A.; Al-Rabiah, A.M. Surgical treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Complications. Ann. Med. Surg. 2020, 52, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilke, H.J.; Großkinsky, M.; Ruf, M.; Schlager, B. Range of international surgical strategies for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Evaluation of a multi-center survey. JOR Spine 2024, 7, e1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.; Sterne, J.A.; Bossuyt, P.M.; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.C.; Patel, A.; Bianco, K.; Godwin, E.; Naziri, Q.; Maier, S.; Lafage, V.; Paulino, C.; Errico, T.J. Gait stability improvement after fusion surgery for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is influenced by corrective measures in coronal and sagittal planes. Gait Posture 2014, 40, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holewijn, R.M.; Kingma, I.; de Kleuver, M.; Schimmel, J.J.P.; Keijsers, N.L.W. Spinal fusion limits upper body range of motion during gait without inducing compensatory mechanisms in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients. Gait Posture 2017, 57, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, S.; Studer, D.; Hasler, C.C.; Romkes, J.; Taylor, W.R.; Lorenzetti, S.; Brunner, R. Quantifying spinal gait kinematics using an enhanced optical motion capture approach in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Gait Posture 2016, 44, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpierre, Y.; Vernet, P.; Surdel, A. Effect of preferred walking speed on the upper body range of motion and mechanical work during gait before and after spinal fusion for patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Clin. Biomech. 2019, 70, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong-Chung, D.A.C.F.; Schimmel, J.J.P.; de Kleuver, M.; Keijsers, N.L.W. Asymmetrical trunk movement during walking improved to normal range at 3 months after corrective posterior spinal fusion in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 2018, 27, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holewijn, R.M.; de Kleuver, M.; Kingma, I.; Keijsers, N.L.W. A prospective analysis of motion and deformity at the shoulder level in surgically treated adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Gait Posture 2019, 69, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.; Pivec, R.; Shah, N.V.; Leven, D.M.; Margalit, A.; Day, L.M.; Godwin, E.M.; Lafage, V.; Post, N.H.; Yoshihara, H.; et al. Motion analysis in the axial plane after realignment surgery for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Gait Posture 2018, 66, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xun, F.; Canavese, F.; Xu, H.; Kaelin, A.; Li, Y.; Dimeglio, A. Dynamic 3D Reconstruction of Thoracic Cage and Abdomen in Children and Adolescents With Scoliosis: Preliminary Results of Optical Reflective Motion Analysis Assessment. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2020, 40, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, W.; Wang, S.; Li, Q.; Ren, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Li, M.; Yang, W.; Deng, W. An All-in-One Array of Pressure Sensors and sEMG Electrodes for Scoliosis Monitoring. Small 2024, 20, e2404136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, M.; Nagura, T.; Fujita, N.; Nakamura, M.; Matsumoto, M.; Watanabe, K. Spinal correction surgery improves asymmetrical trunk kinematics during gait in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis with thoracic major curve. Eur. Spine J. 2019, 28, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, X.; Fan, Q.; Liang, J.; Zhang, T.; Chen, Z.; Guo, H.; Cai, L.; Zhou, X.; Du, Q. Comprehensive spinal correction rehabilitation (CSCR) study: A randomised controlled trial to investigate the effectiveness of CSCR in children with early-onset idiopathic scoliosis on spinal deformity, somatic appearance, functional status and quality of life in Shanghai, China. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e085243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).