Abstract

Conveyor belts are among the most critical components of material transport systems across various industrial sectors, including mining, energy, cement production, metallurgy, and logistics. Their reliability directly affects the continuity and operational costs. Traditional methods for assessing belt condition often require downtime, are labor-intensive, and involve a degree of subjectivity. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in non-destructive and remote diagnostic techniques that enable continuous and automated condition monitoring. This paper provides a comprehensive review of current diagnostic solutions, including machine vision systems, infrared thermography, ultrasonic and acoustic techniques, magnetic inspection methods, vibration sensors, and modern approaches based on radar and hyperspectral imaging. Particular attention is paid to the integration of measurement systems with artificial intelligence algorithms for automated damage detection, classification, and failure prediction. The advantages and limitations of each method are discussed, along with the perspectives for future development, such as digital twin concepts and predictive maintenance. The review aims to present recent trends in non-invasive diagnostics of conveyor belts using remote and non-destructive testing techniques, and to identify research directions that can enhance the reliability and efficiency of industrial transport systems.

1. Introduction

Conveyor belts are among the most essential components of industrial material handling systems, used in mining, power generation, cement production, metallurgy, agriculture, and logistics [1,2]. Their efficiency, safety, and reliability directly determine process continuity and operational costs. In open-pit mining, the length of a single conveyor route can exceed several kilometers [3,4], and a single belt failure can result in financial losses amounting to millions of Polish zlotys [5,6].

During operation, conveyor belts are exposed to intense mechanical and environmental stresses, leading to wear and the development of various types of damage. The most common failures include surface wear, cuts, longitudinal tears, delamination of cover layers, damage to the steel cord core, and localized overheating caused by friction [7,8,9]. Early detection of such defects is essential to prevent serious failures and unplanned downtime. Figure 1 presents an Ishikawa (fishbone) diagram summarizing the technical, environmental, and operational factors affecting conveyor belt reliability. The rate of cumulative degradation processes (e.g., abrasion, fatigue mechanisms) is proportional to the conveyor length, whereas sudden events (such as punctures, cuts, or belt/joint ruptures) are correlated with the frequency of belt passes under loading points (operational cycles), where such failures most commonly occur [10].

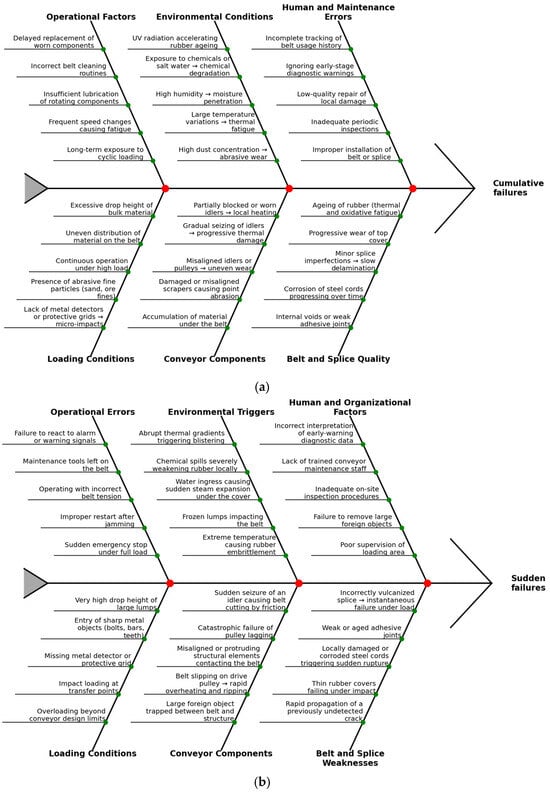

Figure 1.

Ishikawa diagrams illustrating the main technical, environmental, operational and human factors contributing to conveyor belt failures. Diagram (a) summarizes the drivers of cumulative, progressive degradation mechanisms such as wear, fatigue and delamination. Diagram (b) presents the factors associated with sudden, catastrophic failures including punctures, longitudinal tears and splice ruptures.

The operation of belt conveyor systems is inherently affected by a combination of mechanical, environmental, and operational factors that influence their reliability and durability. Failure mechanisms in conveyor belts can generally be classified into two fundamental groups according to the rate and nature of damage progression:

- cumulative (progressive) failures, and

- sudden (catastrophic) failures.

Cumulative failures develop gradually as a consequence of long-term operational stresses, material fatigue, and environmental exposure. These mechanisms typically involve the accumulation of minor, subcritical defects—such as local wear, surface cracking, or corrosion—that, over time, lead to a measurable reduction in belt performance or structural integrity. Such degradation processes are often difficult to detect in their early stages and may remain latent until a critical threshold is reached.

As illustrated in Figure 1a, cumulative failures are driven by a combination of technical, environmental and operational factors, including progressive wear of the cover layers, material fatigue, corrosion of steel cords, humidity variations and repeated loading cycles. The diagram visualizes how these factors accumulate gradually over time and interact to initiate internal degradation mechanisms such as delamination or reinforcement weakening.

In contrast, sudden failures are characterized by a rapid and severe loss of function resulting from the instantaneous exceedance of material strength or critical operating conditions. Examples include tearing, splice rupture, detachment of covers, or large-scale belt separation. These events typically require immediate intervention, cause unplanned downtime, and may pose safety hazards.

Figure 1b summarizes the dominant root causes of sudden failures, such as sharp foreign objects, structural misalignment, local overstressing and splice defects. These contributing factors act abruptly, exceeding the belt’s strength limits and resulting in immediate rupture or tearing. The diagram therefore complements the textual classification by providing a visual overview of the mechanisms associated with catastrophic, non-progressive damage.

To better distinguish these two categories of failure mechanisms, two Ishikawa diagrams (Figure 1) were developed—one for progressive degradation and the other for sudden structural failures. Each diagram (Figure 1) identifies the main categories of root causes—technical, environmental, human, and organizational—that contribute either to progressive deterioration or to abrupt structural failure.

This dual analytical approach facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of the degradation mechanisms and supports the development of targeted maintenance and diagnostic strategies for conveyor belt systems.

Conventional inspections, based on periodic visual checks, are time-consuming, require conveyor shutdown, and depend heavily on operator experience [2,11,12].

The ongoing digital transformation of industry, consistent with the principles of Industry 4.0, promotes a shift from time-based maintenance toward predictive diagnostics and real-time condition monitoring [13,14,15]. Non-destructive testing (NDT) methods, such as ultrasonic testing [16,17], acoustic emission [18,19,20,21], and the magnetic flux leakage (MFL) technique [22,23,24,25,26,27,28], are increasingly applied to conveyor belt inspection, enabling the detection of structural defects without the need for disassembly [2,29]. At the same time, optical sensor systems, high-resolution cameras [30,31,32], and infrared thermography are rapidly advancing, allowing for the automatic identification of surface anomalies [30,31,32].

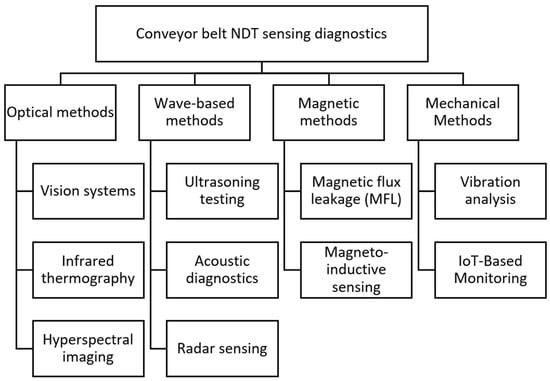

Figure 2 presents a hierarchical classification of non-destructive and sensor-based diagnostic methods used for conveyor belt condition assessment.

Figure 2.

Hierarchical classification of non-destructive and remote sensing methods for conveyor belt diagnostics according to their underlying physical principle.

The integration of sensor systems with advanced data processing and artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms is becoming increasingly important for automated fault detection and prediction [33,34,35,36,37,38]. Machine learning and deep neural networks enable automatic feature extraction, damage classification, and remaining useful life (RUL) prediction [39,40,41,42,43]. Another significant trend is multi-sensor data fusion, which improves diagnostic robustness, reduces uncertainty, and enhances predictive accuracy [6]. Recent literature also highlights the growing role of digital twin technology, which enables real-time synchronization between the physical conveyor and its virtual model [44,45,46].

The objective of this article is to provide a comprehensive review of non-destructive diagnostic methods for conveyor belts based on advanced sensing technologies, highlighting their principles, practical applications, advantages, and limitations. The paper discusses systems based on machine vision, infrared thermography, ultrasonic and acoustic methods, magnetic techniques, vibration analysis, as well as radar and hyperspectral imaging solutions. Furthermore, it highlights the role of artificial intelligence and data integration in the automatic detection of defects. The article concludes with a comparison of diagnostic methods and the identification of future research directions, including the integration of hybrid systems, the development of predictive approaches, and the implementation of digital twin technology.

The present study follows a structured narrative review methodology appropriate for engineering-focused technological synthesis. Relevant publications were identified through targeted searches in Scopus, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore and MDPI databases using combinations of keywords, including: conveyor belt diagnostics, conveyor belt damage, non-destructive testing, magnetic flux leakage, MFL, infrared thermography, thermal imaging, acoustic emission, ultrasonic inspection, machine vision, AI-based inspection, sensor-based monitoring, and distributed sensing.

To complement database searches, a bibliometric query was carried out using the Publish or Perish tool to identify highly cited foundational and recent influential works in the domain. Additional relevant publications were incorporated through backward citation screening. Priority was given to peer-reviewed studies presenting methodological advances, industrial implementations, comparative analyses, or representative case studies. This procedure ensured broad and balanced coverage of the main diagnostic technologies without imposing systematic review protocols inappropriate for the technological scope of this work.

2. Typical Failures and Diagnostic Needs

In industrial applications, conveyor belts are exposed to combined mechanical, thermal, and environmental stresses that accelerate material degradation. In mining and power generation systems, they operate continuously, often in dusty environments with variable humidity and temperature [2]. As a result, gradual structural degradation occurs, affecting both the rubber cover layers and the load-bearing elements, such as fabric plies or steel cord reinforcements [6]. Cumulative wear processes typically progress undetected until a critical failure occurs due to fatigue, abrasion, or material aging. Belts may also suffer sudden failures caused by punctures, cuts, or complete ruptures. In such cases, continuous condition monitoring using non-destructive sensing technologies plays a crucial role—enabling early defect detection, hazard alerting, and automatic shutdown to minimize failure consequences.

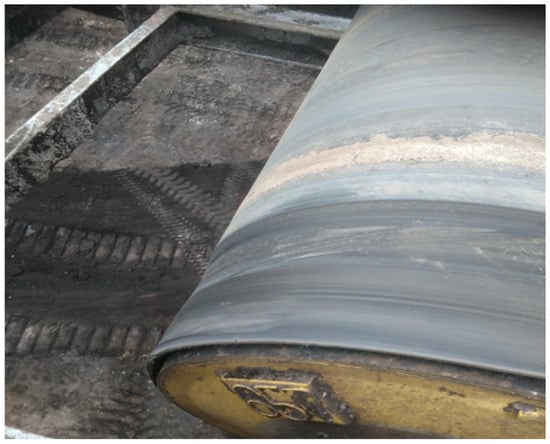

Surface wear is the most common type of damage, resulting from contact between the belt and the conveyed material, idlers, or contaminants. Over time, it leads to a reduction in the thickness of the cover layer, which affects adhesion, sealing capability, and belt durability [7,47,48]. An example of surface wear on a conveyor belt is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Surface wear of a conveyor belt—abrasion at the interface with sealing elements [49].

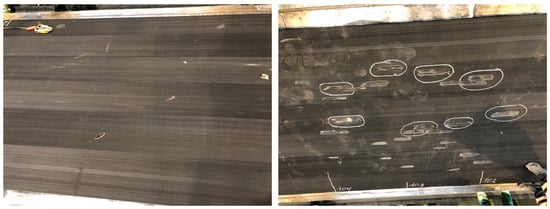

Cuts and longitudinal tears may occur when a sharp object (e.g., a stone or a piece of metal) becomes trapped between the belt and a roller or another structural component of the conveyor. Such damage is typically sudden and severe, often resulting in the need to replace an entire section of the belt [9,32,50]. Representative examples of this type of failure are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Cuts and longitudinal tears of a conveyor belt: (a) caused by a structural element of the conveyor frame; (b) caused by a jammed stone.

Delamination refers to the separation of the cover layers from the core, or separation between fabric plies. In the early stages, such defects are not visible on the surface, but they cause local stiffness variations and may eventually lead to detachment of cover fragments [12]. Diagnostics of these defects require methods capable of assessing internal structure, such as ultrasonic testing, magnetic techniques, or thermal imaging. An example of delamination damage in a multi-ply belt is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Delamination in a multi-ply conveyor belt.

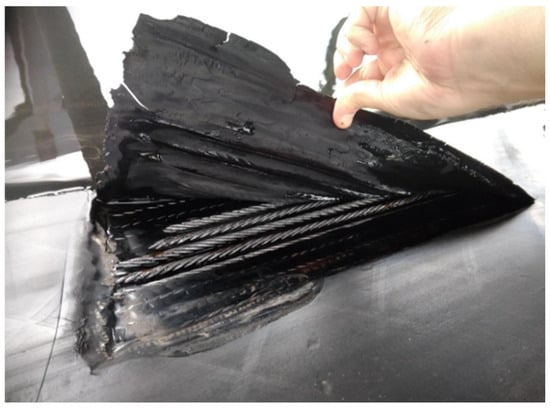

In steel cord conveyor belts, the most critical failures concern the belt core. Fracture or corrosion of the steel cords leads to a loss of tensile strength, which can result in belt rupture during operation [43,51]. Examples of steel cord core damage detected during belt preparation for regeneration (after cover removal by milling) are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Damage to the core of a steel cord conveyor belt (St type) detected during preparation for refurbishment after cover milling.

Non-destructive testing (NDT) methods, such as the magnetic flux leakage (MFL) technique, enable the detection of local magnetic field anomalies corresponding to damage in the steel cords of the belt core [7]. In modern diagnostic systems, signals from multi-channel magnetic sensors are processed in real time and spatially correlated with the belt position, enabling localization of defects with centimeter-level precision [2]. The literature highlights the importance of early corrosion detection, which can be achieved using magnetoacoustic or ultrasonic techniques even before visual symptoms appear [12].

Local overheating of the belt is one of the key symptoms of mechanical degradation or improper operation of the conveyor system. It may result from excessive friction between the belt and structural components, misalignment of idlers, or slippage on the drive pulley [8]. An increase in temperature accelerates rubber degradation and delamination, and in extreme cases may even lead to ignition. Infrared thermography (IR) has proven to be an effective non-destructive method for detecting thermal anomalies (“hot spots”) and identifying early signs of friction-related damage [1,8]. An example of belt damage resulting from overheating and blistering of the rubber cover is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Blistering of rubber belt covers caused by overheating [52].

Functional and Technical Requirements for Diagnostic Systems

In modern industrial plants, conveyor belt diagnostic systems should meet several fundamental requirements [53]:

- Early damage detection—the system should identify anomalies at an early stage, allowing maintenance or repair to be performed during planned downtime.

- Continuous on-line operation—measurements must be performed without interrupting conveyor operation.

- Environmental robustness—the system must operate reliably in the presence of dust, vibrations, humidity, and temperature variation.

- Integration with predictive and AI-driven analytics—enabling defect classification, risk assessment, and estimation of remaining useful life (RUL) [46].

- Easy integration with control and maintenance systems (SCADA, MES)—to support rapid decision-making regarding maintenance actions or conveyor shutdown.

Fulfilling these requirements necessitates the integration of non-destructive sensing techniques—vision, magnetic, acoustic, and thermal—into a unified diagnostic and monitoring framework. Such solutions align with the concept of sensor-based monitoring and the development of digital twin systems for conveyor transportation [12,46].

Given the diversity of conveyor belt failure mechanisms, different diagnostic methods are suited to detecting specific types of defects. Progressive damage processes such as wear, delamination, corrosion, and thickness loss require methods capable of quantitative internal assessment, whereas sudden failures including cuts, punctures, and longitudinal tears rely on fast surface-oriented or thermal detection techniques. The subsequent sections therefore present non-destructive diagnostic methods in an order that reflects their relevance to the respective failure categories, linking the typical fault mechanisms discussed above to the sensing principles introduced in Section 3.

3. Non-Destructive and Sensor-Based Diagnostic Methods

The development of sensor-based, operator-independent and non-destructive methods represents one of the most important research directions in conveyor belt condition assessment. Unlike traditional manual inspections, these techniques enable the acquisition of information on the technical condition of the belt without interrupting its operation, while offering significantly higher accuracy and eliminating operator subjectivity. These methods rely on diverse physical principles—image analysis, thermal radiation, acoustic and ultrasonic waves, magnetic flux variations, or microwave sensing—yet share a common goal: enabling continuous, automated, and real-time belt condition assessment [2]. Effective failure prevention requires autonomous operation and real-time response capability. Cumulative degradation processes can be analyzed periodically or continuously, either automatically or under operator supervision.

3.1. Vision-Based Methods and Imaging Systems

Machine vision systems are among the most commonly used approaches for non-contact diagnostics of conveyor belts. These systems employ RGB, stereo, or high-resolution industrial cameras to capture images of the belt surface during operation. Image analysis using machine learning algorithms enables the identification of typical surface defects, such as cracks, abrasions, contamination, or irregular wear patterns [54]. Modern systems utilize models based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs)—including YOLO, ResNet, and EfficientNet—which allow for real-time defect classification with an accuracy exceeding 95% [55]. An example implementation is the BECS separator belt monitoring system, where a vision camera was integrated with infrared thermography and an artificial intelligence module, enabling the simultaneous detection of ferromagnetic contaminants and rubber surface damage [54]. The main advantages of vision-based methods are their completely contactless operation and the ability to perform inspections without stopping the conveyor. However, environmental conditions—such as dust, lighting variability, and humidity—may adversely affect image quality. In practice, these systems require regular calibration and integration with analytical software, which filters noise and provides the operator with clear, actionable diagnostic reports.

Machine-vision-based diagnostics face several practical limitations that influence their performance in real industrial environments. A key challenge is the limited availability of publicly accessible datasets, which restricts the generalizability of trained models and complicates transfer learning between different mines or belt types. Strong domain shift effects—caused by differences in belt colour, lighting conditions or camera placement—often require site-specific retraining. Moreover, dust contamination and image blur can significantly degrade segmentation quality and contribute to false positives, especially when detecting small or low-contrast defects. Real-time deployment on high-speed conveyors may also be constrained by computational cost, especially for deep neural architectures requiring high-throughput inference. These factors define the practical boundaries of machine-vision diagnostics and underline the need for robust preprocessing, adaptive models and hybrid sensing strategies.

3.2. Infrared Thermography

Infrared thermography (IRT) is one of the most effective non-destructive techniques for continuous thermal monitoring of conveyor belt systems under industrial conditions. It is based on the detection and recording of thermal radiation emitted by the belt surface and transport system components (such as pulleys and idlers). Temperature variations can indicate localized overheating caused by friction, misaligned idlers, drive pulley slippage, or bearing damage [8]. In the study by Szurgacz et al. (2021) [56], a thermal imaging camera was used to assess the condition of a belt conveyor drive system in a lignite mine. Thermal analysis enabled the detection of thermal anomalies in mechanical components before failure occurred. Similarly, Siami et al. (2024) [57] applied semantic segmentation of thermal images for the automatic identification of overheated idlers, achieving high classification accuracy.

The main advantage of IRT is its ability to perform fully autonomous and continuous monitoring without physical contact. In industrial systems, IR sensors are often integrated with alarm modules, which automatically notify operators when the temperature exceeds the permissible threshold at any point along the belt. The main limitations of this method include the need to ensure adequate thermal contrast and its susceptibility to ambient temperature variations. Nevertheless, infrared thermography is considered one of the most valuable preventive diagnostic tools in the mining and power generation industries [56].

3.3. Ultrasonic and Acoustic Methods

Ultrasonic testing enables the detection of delamination, internal cracks, and rubber degradation within the belt structure [12]. In turn, acoustic signal analysis focuses on the sounds generated during belt operation—variations in their frequency spectrum can indicate damaged idlers, pulleys, or uneven load distribution.

Miao, Wang, and Li (2022) [55] proposed a method for detecting longitudinal belt tears based on acoustic signals analyzed using a DenseNet neural network, achieving high classification accuracy. In another approach, a mobile walking robot was employed to collect acoustic data from conveyor idlers at KGHM Polska Miedź S.A. facilities. This solution enabled autonomous assessment of idler condition without the need to stop conveyor operation [21]. Acoustic methods offer high sensitivity and enable early fault detection; however, they require advanced signal processing to isolate diagnostic features from industrial background noise. However, their main limitation lies in the requirement for advanced signal processing, necessary to distinguish diagnostic sounds from industrial background noise. Currently, there is a growing trend toward integrating acoustic and vibration-based techniques within a single detection system, providing a more comprehensive and robust diagnostic framework [58].

Although acoustic and ultrasonic methods offer valuable capabilities for detecting internal defects, they are subject to several important trade-offs. Ultrasonic inspection provides millimetre-scale resolution, but its performance strongly depends on stable sensor–belt coupling and may degrade in the presence of moisture, dust or surface roughness. Signal attenuation limits the effective penetration depth, and repeatability can be affected by variations in belt tension and temperature. Acoustic and acoustic-emission methods, while attractive due to their non-contact nature, are highly sensitive to industrial background noise, requiring advanced filtering and signal-processing techniques to avoid false alarms. Their defect localization capabilities are limited, and performance depends on the distance between the sensor and the fault source. These constraints highlight the need for hybrid sensing configurations and adaptive algorithms to fully exploit the potential of acoustic and ultrasonic diagnostics.

3.4. Magnetic Methods

Magnetic flux leakage (MFL) inspection is one of the key non-destructive techniques for evaluating the condition of steel-cord conveyor belts. The magnetic field generated by the sensor magnetizes the steel cords, and any cracks or material losses cause local disturbances in the magnetic flux, which can then be recorded and analyzed [26,28,33,59]. Modern MFL systems employ multi-channel Hall sensors and real-time signal analysis, enabling precise mapping of core defects along the belt [2]. This technique is particularly effective in detecting cracks and corrosion of steel cords, which are invisible to vision-based inspection systems. However, the method requires careful calibration, proper sensor alignment relative to the belt surface, and minimization of external magnetic interference to ensure measurement accuracy and reliability.

The performance of MFL systems can also be affected by factors such as magnetization stability, calibration drift of the sensor array and variability in belt construction (e.g., number and spacing of steel cords), which may influence signal interpretation and require periodic recalibration.

3.5. Vibration Analysis and Vibration Sensors

Vibration sensors are increasingly applied for condition monitoring of components associated with conveyor belts, such as idlers, rollers, and drives. Vibration signal analysis enables the early detection of imbalance, bearing defects, and instability in system operation [58]. Vibration data are typically collected using miniature MEMS sensors and then processed locally within IoT modules. These systems offer low implementation costs and high scalability, making them suitable for industrial IoT-based maintenance frameworks. The main limitation of vibration-based diagnostics is the lower precision of damage localization compared to imaging methods. Therefore, vibration data are often integrated with thermal or acoustic information to improve diagnostic reliability and enable comprehensive condition assessment [46].

3.6. Radar and Hyperspectral Methods

The application of radar and hyperspectral imaging technologies in conveyor belt diagnostics remains at the research stage but shows high potential for future industrial implementation. Radar-based measurement systems enable the detection of structural changes beneath the belt surface, while hyperspectral imaging allows for the analysis of the composition of the cover material and the identification of material inhomogeneities [9]. The integration of these methods with optical sensing systems and artificial intelligence may, in the future, enable the creation of comprehensive digital twins that accurately represent the real-time operational state of the conveyor system. The main limitations of these approaches are the high cost of instrumentation and the complexity of data processing. Nevertheless, the advancing development of FMCW radar sensors and VNIR hyperspectral cameras indicates rapid technological progress in this field.

3.7. Commercial Systems and Implementation Solutions

Several advanced diagnostic systems based on remote monitoring methods are already available on the market. For instance, AP Sensing GmbH offers a Distributed Fiber Optic Sensing (DFOS) system that enables the detection of temperature variations and acoustic anomalies along the entire length of a conveyor. This system is used in transport tunnels and open-pit mining operations, where it provides continuous monitoring of multi-kilometer belt sections. At KGHM Polska Miedź S.A. (Lubin, Poland), an autonomous inspection robot has been implemented for automatic monitoring of conveyor idlers, utilizing acoustic and vibration analysis. The research results confirmed the feasibility of replacing manual inspections with a fully automated system, although its functionality is currently limited to idler inspection and does not yet include direct assessment of the conveyor belt condition [21]. Hybrid solutions are also emerging on the market, combining machine vision, infrared thermography, and vibration sensing, with real-time data integration through SCADA platforms. These examples illustrate the ongoing transition toward fully automated, AI-assisted NDT systems in conveyor maintenance.

In industrial applications of the AP Sensing GmbH system, deployments typically involve conveyor routes operating under harsh environmental conditions, including high dust levels, variable temperatures (ranging from sub-zero values to above 40 °C), elevated humidity, and strong structural vibrations. The distributed fibre-optic sensing (DFOS) technology enables continuous acquisition of temperature and acoustic signatures along the entire conveyor length. Published industrial use cases highlight the robustness of the system in such environments and its ability to detect localized thermal anomalies—such as overheated idlers—with spatial resolutions on the order of several meters, enabling early identification of hazardous conditions before mechanical failure becomes apparent.

In underground operations at KGHM Polska Miedź S.A., an autonomous inspection robot equipped with an RGB camera, a thermal imaging camera, microphones, and accelerometers has been deployed to monitor conveyor components under conditions of limited visibility and substantial airborne dust. Field studies demonstrated that the platform can effectively identify early symptoms of idler faults and locate sources of abnormal vibration and noise during conveyor operation. The capability to perform such inspections without stopping the conveyor system represents a significant practical advantage in demanding industrial environments.

3.8. Integration and Sensor Fusion

Integration of heterogeneous data sources—commonly referred to as sensor fusion—is gaining growing attention in NDT and industrial metrology. Combining information from vision cameras, thermal sensors, acoustic sensors, and magnetic sensors enhances diagnostic accuracy and reduces the number of false alarms. A review of the literature indicates that the combination of ultrasonic, vibration, and thermographic data provides the most comprehensive assessment of the conveyor belt’s technical condition. This multi-sensor approach also forms the foundation for developing digital twins of conveyor transport systems, where sensor data are continuously synchronized with a simulation model, enabling real-time representation of the belt’s operational state.

3.9. Milestones in the Development of Conveyor Belt Diagnostic Methods

The evolution of non-destructive conveyor belt diagnostics has progressed through several key technological stages, each enabling increasingly precise and automated monitoring of belt condition. Early diagnostic practices relied solely on periodic human inspections, which were subjective and required conveyor downtime [2,11]. A foundational shift occurred with the introduction of magnetic flux leakage (MFL) sensors in conveyor belt monitoring. Early work by Harrison (2000) [1] demonstrated the feasibility of online magnetic inspection for detecting steel-cord damage, while later developments by Błażej et al. (2018) [22] and Mazurek et al. (2018) [28] improved sensor sensitivity, multi-channel measurements, and defect localization accuracy. These advances established MFL as the core technology for evaluating the internal condition of steel-cord belts.

A major milestone in the assessment of belt surfaces was achieved with the emergence of machine vision systems. High-resolution imaging combined with neural network–based classifiers enabled automated detection of cuts, abrasion, and surface anomalies. Early AI-enhanced implementations—such as the two-layer neural network proposed by Kirjanów-Błażej and Rzeszowska (2021) [35]—paved the way for more advanced deep learning architectures. Recent studies using CNN and YOLO-based detectors [38,57] demonstrated accuracy exceeding 95%, enabling real-time defect classification under industrial conditions.

Infrared thermography (IRT) marked another breakthrough by allowing continuous monitoring of thermal anomalies associated with idler damage, friction, or improper belt tracking. Pioneering work by Bagavathiappan et al. (2013) [31] established IRT as a versatile tool for condition monitoring, later adapted for conveyor systems by Siami et al. (2021, 2024) [8,57] and Szurgacz et al. (2021) [56], who demonstrated effective detection of overheated elements and drive system failures.

Ultrasonic and acoustic sensing technologies further extended diagnostic capabilities into subsurface degradation mechanisms. Research by Miao, Wang, and Li (2022) [55] introduced deep learning for acoustic-based detection of longitudinal tears, while Ericeira et al. (2020) [17] and Krampikowska and Świt (2019) [18] showed the usefulness of acoustic emission and ultrasonic propagation for identifying internal delamination and component faults. These approaches represent an important complement to visual and thermal inspection techniques.

Recent advances include radar and hyperspectral imaging, which offer the possibility of detecting previously inaccessible structural irregularities. Work by Semrád and Draganová (2022, 2023) [7,60] demonstrated the potential of magnetic microwire-based sensing and magnetic marker techniques for tracking belt degradation. Emerging FMCW radar and VNIR hyperspectral sensors [60] are considered promising technologies for next-generation diagnostics.

The most recent milestone is the integration of AI-driven multisensor data fusion and the emergence of digital twin concepts. Studies by Pulcini and Modoni (2024) [46] and Mafia et al. (2024) [45] demonstrated that combining vibration, thermal, and acoustic data within machine-learning-supported digital twins enables accurate prediction of remaining belt life and early fault forecasting. These developments reflect a shift from passive monitoring toward predictive and prescriptive maintenance strategies, fully aligned with Industry 4.0 principles.

Overall, these key milestones illustrate the technological transition from manual inspection to automated, multimodal, and AI-enhanced diagnostic ecosystems, where hybrid sensing architectures and digital twins form the foundation for future predictive maintenance in conveyor systems.

To provide a clearer hierarchical structure of the existing research and to emphasize key technological achievements in the development of conveyor belt diagnostics, a summary of milestone advances is presented in Table 1. This overview highlights the evolutionary transition from early manual inspections, through the introduction of magnetic and thermal sensing, to modern AI-enhanced and multisensor predictive systems. The table also organizes major diagnostic methods chronologically, clarifying their contribution to the current state of the art.

Table 1.

Technological milestones in the development of non-destructive diagnostic methods for conveyor belts.

3.10. Detection Capabilities of Diagnostic Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Assessment, Accuracy and Limitations

The sensing technologies used for conveyor belt inspection differ significantly in whether they provide qualitative or quantitative information, in their achievable measurement accuracy, and in the types of damage they can reliably detect.

Machine vision systems (RGB cameras and AI models) primarily offer qualitative assessment, such as identifying the presence, shape, orientation, and severity category of surface defects including cuts, cracks, abrasions and contamination. However, when combined with calibrated image-processing algorithms, these systems can also yield quantitative measurements, such as defect length, width, area, and wear progression over time. Their detection accuracy typically reaches the sub-millimetre level, but their reliability depends strongly on lighting conditions, dust levels, optical contrast, and camera calibration. These limitations make vision systems excellent for real-time detection of sudden surface failures, but less effective for diagnosing subsurface or internal structural degradation.

Infrared thermography (IR) provides both qualitative and quantitative temperature-based diagnostics. Qualitatively, IR imaging is used to identify “hot spots,” friction-induced overheating, misaligned idlers, and drive pulley slippage. Quantitatively, IR cameras allow estimation of absolute and differential temperature fields with a typical thermal resolution of 0.1–0.2 °C, enabling precise assessment of thermal gradients associated with mechanical degradation processes. The main limitations include reliance on sufficient thermal contrast and sensitivity to environmental temperature variability; however, IR remains one of the most effective methods for early detection of developing mechanical faults.

Ultrasonic and acoustic techniques provide inherently quantitative diagnostic information. Ultrasonic inspection enables measurement of internal defect dimensions, delamination depth, and material attenuation with millimetre-scale resolution. Acoustic emission and acoustic signal analysis enable quantitative extraction of spectral and temporal parameters associated with idler or pulley faults. These techniques are therefore particularly suitable for detecting cumulative, subsurface degradation processes invisible on the belt surface. Their main limitations include sensitivity to background industrial noise, signal dispersion, and the need for careful calibration.

Magnetic flux leakage (MFL) methods provide the highest level of quantitative precision among internal inspection techniques for steel-cord belts. MFL sensors quantify cross-section loss, corrosion severity, broken cord length, and magnetic field asymmetry with centimetre-level spatial resolution, enabling accurate defect localization. The method is capable of detecting early-stage internal degradation long before visual or thermal symptoms appear. However, its accuracy depends on proper sensor alignment, belt position stability, and minimization of electromagnetic interference, which may complicate use in heavily industrial environments.

Vibration-based techniques using MEMS or IoT accelerometers deliver quantitative metrics such as RMS vibration levels, spectral peak amplitudes, and characteristic fault frequencies. These parameters allow identification of idler imbalance, bearing degradation, and structural instability. Although these systems are low-cost and scalable, their primary limitation is the difficulty in localizing the exact defect position and distinguishing between multiple simultaneous vibration sources.

Radar and hyperspectral imaging offer emerging diagnostic capabilities that can be both qualitative (material heterogeneity mapping) and quantitative (spectral signature analysis, subsurface depth estimation). Radar-based methods provide centimetre-to-millimetre penetration depending on frequency, while hyperspectral imaging enables quantitative detection of chemical changes, rubber aging, and material inhomogeneity. Their current limitations include high equipment cost, complex data processing, and limited industrial implementation.

Finally, hybrid diagnostic systems and multisensor fusion approaches combine vision, thermal, magnetic, acoustic and vibration data to deliver both qualitative and quantitative evaluation across multiple degradation mechanisms. These systems compensate for the limitations of individual sensors and improve reliability through measurement redundancy. Such hybrid solutions form the methodological foundation for predictive maintenance frameworks and digital twin architectures.

4. Data Processing and Artificial Intelligence in Sensor-Based Diagnostics

With the advent of next-generation sensing technologies and the ongoing digital transformation of industry, the volume of diagnostic data from conveyor belt systems has grown exponentially. These data include visual, thermal, vibration, acoustic, and magnetic signals, creating an environment characteristic of big data systems. As a result, the application of advanced data processing and artificial intelligence (AI) techniques has become essential, enabling the extraction of diagnostic and predictive information from large, heterogeneous datasets [2,53].

4.1. Preprocessing and Signal Analysis

The first stage of diagnostic data processing involves signal conditioning and preprocessing, including filtering, denoising, normalization, and segmentation. For acoustic and vibration signals, commonly used techniques include the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT), and Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC) extraction, which describe the frequency-domain characteristics of defects [55,58]. Figure 8 presents a data processing workflow for AI-assisted conveyor belt diagnostics.

Figure 8.

Data processing scheme in AI-assisted conveyor belt diagnostics.

For visual and thermal images, key steps include region-of-interest (ROI) extraction, illumination normalization, and dust-related noise removal. In the study by Siami et al. (2024) [57], semantic segmentation using the U-Net architecture was applied for the automatic detection of overheated conveyor idlers, achieving an accuracy exceeding 96%.

For magnetic data from MFL sensors, filter-based signal processing and anomaly detection are employed, typically based on statistical indicators such as peak-to-peak amplitude and flux variance [7]. These results are then further analyzed to identify the type and location of damage along the belt.

4.2. Application of Machine Learning

Machine learning (ML) algorithms form the analytical core of modern conveyor-belt diagnostic systems. Classification models such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests (RF), k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), and Gradient Boosting are widely used for defect classification and component condition prediction [58]. For example, Pulcini and Modoni (2024) [46] developed a machine learning–based digital twin of a conveyor belt, utilizing temperature, vibration, and acoustic sensor data for real-time condition prediction. The model achieved a 92% accuracy rate in degradation forecasting, confirming the effectiveness of ML approaches in industrial applications. In another study, Miao, Wang, and Li (2022) [55] presented a DenseNet-based system that analyzed acoustic signals from a conveyor and classified longitudinal belt tears in real time. The application of transfer learning reduced model training costs and improved detection performance, even under noisy industrial conditions. Recently, hybrid ML models integrating multi-sensor features (vision, acoustics, vibration) have demonstrated improved robustness and prediction accuracy [54].

4.3. Deap Learning and Neural Networks

The application of deep learning (DL) methods has revolutionized the approach to conveyor belt diagnostics. Unlike traditional machine learning (ML) techniques, DL models automatically learn feature representations, eliminating the need for manual feature extraction. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are primarily used for image analysis [8,54,57], while Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), including Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and transformer architectures are applied to the analysis of time-series signals [55].

A practical implementation was presented by Martinez-Rau et al. (2024) [53], who developed an on-device anomaly detection system capable of identifying vibration anomalies directly on an edge device. This approach enables real-time data analysis without transferring large data volumes to the cloud, thereby reducing latency and enhancing system security.

Autoencoders (AE) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are also employed for detecting abnormal patterns and generating synthetic defect data to expand training datasets and improve classifier performance [12,37].

4.4. Multi-Sensor Data Fusion

Multi-sensor data fusion—integrating information from vision, thermal, acoustic, magnetic, and vibration sensors—enables a multidimensional and redundant assessment of system condition.

In the study Combining Multi-Sensor Conveyor System Intelligence (2025), it was demonstrated that integrating ultrasonic, acoustic, and vibration data into a single decision model reduced the number of false alarms by more than 30% compared to systems based on a single sensing modality. In the context of distributed sensor-based monitoring, data fusion provides measurement redundancy that improves system robustness and fault tolerance [54].

In practice, two main approaches are employed:

- Data-level fusion—integration of raw, unprocessed signals from multiple sensors;

- Decision-level fusion—combination of classification results derived from different information sources.

Modern diagnostic platforms combine both fusion strategies within edge–cloud architectures, where data are preprocessed locally and aggregated in the cloud for global optimization [53].

4.5. Digital Twin Concept

One of the most promising research directions is the implementation of Digital Twin (DT) technology for conveyor-belt diagnostics. A digital twin is a dynamic virtual replica of a physical system that mirrors its real-time behavior through continuous synchronization of sensor data, simulation, and predictive algorithms [46].

Pulcini and Modoni (2024) [46] developed a digital twin for a conveyor system that integrated vibration, temperature, and acoustic emission sensor data into a machine learning–based simulation environment. The digital twin enabled dynamic updating of the belt’s technical condition and prediction of remaining useful life (RUL) with an accuracy of ±5%.

Another study [61] proposed an open-architecture system using the OPC UA standard and MQTT protocol, allowing communication between digital models and real-world sensors. This approach creates a feedback loop between the physical and virtual domains, forming the foundation of Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS).

The key benefits of implementing a digital twin include:

- Continuous synchronization between the real and simulated system states,

- The ability to perform “what-if” scenario testing for potential failures,

- Predictive optimization of maintenance schedules.

However, challenges include integration of heterogeneous data, high computational demands, and the need for standardized data exchange models across different platforms [60].

The combination of machine learning, deep learning, and multi-sensor data fusion forms the foundation of modern sensor-based monitoring systems for conveyor belts. Artificial intelligence enables automatic defect classification, anomaly detection, and material degradation prediction, while the development of the digital twin concept facilitates the transition from reactive to predictive diagnostics. This direction aligns fully with the Industry 4.0 paradigm and digital maintenance systems, integrating sensing, AI, and simulation technologies into a unified predictive and metrological ecosystem.

5. Comparison of Diagnostic Methods

The rapid advancement of sensor-based monitoring and non-destructive testing (NDT) techniques has led to a wide spectrum of tools for assessing conveyor belt condition. However, the selection of an appropriate technology depends on several factors, including belt type, operating environment, required measurement precision, and implementation cost. This section summarizes the main diagnostic methods discussed in the previous chapters, analyzing their capabilities, limitations, and technological maturity levels.

Machine vision–based systems are characterized by high versatility and relatively low implementation costs. They are ideal for detecting surface defects such as abrasions or cuts, but they do not provide information about the internal structure of the belt. Their effectiveness increases significantly when artificial intelligence algorithms are applied to automate image classification [54].

Infrared thermography (IR) enables the identification of thermal anomalies and damage caused by friction. IR systems operate in a fully contactless manner and are insensitive to variable lighting conditions, but they require adequate thermal contrast to ensure measurement reliability [56,57].

Ultrasonic and acoustic methods enable detection of internal degradation and delamination. Their main limitation lies in high sensitivity to noise and the need for precise calibration. Acoustic approaches are effective for detecting idler and pulley defects, while ultrasonic testing is particularly suitable for identifying delamination and cracking. The main drawbacks of these methods are their sensitivity to environmental noise and the need for precise calibration [55,58].

Magnetic flux leakage (MFL) techniques are indispensable for steel-cord belt inspection, offering accurate detection of fractures and corrosion but requiring complex calibration and specialized equipment [2,7,45].

Vibration analysis is a cost-effective and robust approach, well-suited for distributed monitoring through MEMS and IoT modules. However, their main limitation lies in the difficulty of unambiguously locating the defect source [58].

In contrast, radar and hyperspectral methods remain largely experimental, yet they offer strong potential for detecting subsurface structural defects. When combined with AI models and the digital twin concept, these methods may in the future form the foundation for real-time predictive diagnostics [9,46].

Industrial practice shows a growing trend toward multi-sensor integration, combining visual, acoustic, and thermal modalities into unified diagnostic frameworks. Fusion of data from vision cameras, acoustic sensors, and thermal sensors enhances detection reliability and enables the early identification of potential failures. Examples include systems developed by AP Sensing GmbH and KGHM Polska Miedź S.A., which integrate fiber-optic and acoustic sensors for remote conveyor belt condition monitoring [21].

Following the failure classification introduced in Section 1, it is important to clarify how individual diagnostic methods correspond to cumulative (progressive) and sudden (catastrophic) failure mechanisms in conveyor belts. Cumulative failures—such as surface wear, fatigue-related degradation, gradual delamination, and corrosion of steel cords—develop over long periods and typically require high-resolution, trend-oriented sensing methods. Techniques such as magnetic flux leakage (for internal steel-cord degradation), ultrasonic testing, acoustic emission analysis, infrared thermography, and machine vision–based wear measurements are well suited for observing progressive structural changes and thermal anomalies associated with long-term degradation processes.

In contrast, sudden failures—including cuts, punctures, jams, and longitudinal tears—occur abruptly and require sensing systems capable of real-time anomaly detection. Machine vision systems, infrared thermography, and acoustic monitoring are particularly effective in identifying rapid changes in the belt’s condition, such as sharp discontinuities or localized overheating caused by mechanical jamming. Methods relying on fast imaging or acoustic signatures are therefore essential for emergency detection.

Certain sensing approaches serve both categories. Hybrid and multisensor diagnostic systems that combine vision, thermal, magnetic, and acoustic modalities provide redundancy and enable simultaneous monitoring of slow-progressing degradation and sudden disruptive events. These systems form the basis of modern predictive maintenance frameworks and offer a more complete representation of belt health.

To reflect these distinctions more clearly, Table 2 has been revised to include an additional column specifying the failure types for which each diagnostic method is most applicable.

Table 2.

Comparison of conveyor belt diagnostic methods.

The analysis confirms that no single diagnostic method provides a complete assessment of conveyor belt condition. Vision and thermal methods are the most widely used due to their simplicity and low implementation cost, whereas magnetic and ultrasonic techniques offer a deeper insight into the internal structure of the belt. Increasing attention is being given to AI-based solutions and multi-sensor data fusion, which enable the development of self-learning diagnostic systems with high efficiency and predictive capabilities.

In the context of sustainable maintenance and Industry 4.0 transformation, hybrid systems combining multiple NDT and sensing techniques within a unified digital ecosystem appear the most promising. Integration with the digital twin paradigm enables a shift from reactive to predictive maintenance, reducing failure risk and operational costs while improving measurement reliability.

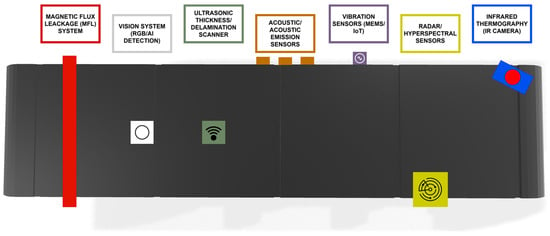

To complement the analytical summary of non-destructive techniques presented in this review, Figure 9 illustrates a generalized deployment layout of multisensor diagnostic systems along a conveyor belt. The schematic provides a practical overview of where individual sensing modalities are typically installed in industrial applications and clarifies how each system interacts with the belt and conveyor components.

Figure 9.

Generalized deployment layout of non-destructive diagnostic systems used for conveyor belt monitoring. The diagram illustrates typical installation locations of magnetic flux leakage (MFL) sensors, vision cameras, ultrasonic probes, acoustic emission sensors, vibration MEMS modules, radar/hyperspectral units, and infrared thermography systems along the conveyor structure.

Magnetic flux leakage (MFL) systems are commonly mounted below the belt (return strand), where the sensor head can maintain a constant proximity to the steel-cord core. Vision-based systems equipped with RGB or high-resolution cameras are installed above the upper belt surface, enabling continuous inspection of visible defects such as cuts, wear, or contamination. Ultrasonic probes for delamination or thickness measurement are deployed in close contact with the belt surface, typically at dedicated maintenance sections. Acoustic emission sensors are mounted on the conveyor frame near idlers, where they capture characteristic impact and friction signatures. Vibration MEMS sensors are directly attached to idler housings, enabling the detection of bearing degradation. Radar and hyperspectral imaging modules are positioned laterally or obliquely above the belt, where their field of view covers surface and subsurface structures. Infrared thermography cameras are commonly installed at an angle near drive stations or loading points to monitor friction-induced heating and idler failures.

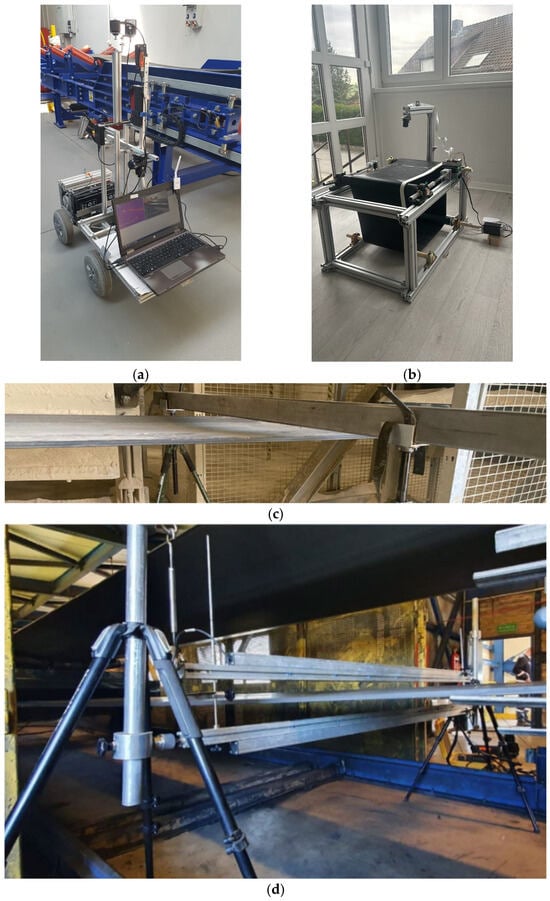

To complement the generalized deployment scheme presented in Figure 9, Figure 10 shows representative examples of real industrial installations of conveyor-belt diagnostic systems. Panels (a) and (b) illustrate vision-based and robotic inspection solutions deployed in operational environments, whereas panels (c) and (d) present non-destructive testing systems used for internal belt condition assessment. Specifically, the DiagBelt magnetic flux leakage system (Figure 10c) is installed beneath the return strand, enabling continuous detection of broken steel cords, corrosion and splice defects in steel-cord belts [62]. The BeltSonic ultrasonic device (Figure 10d), mounted in direct contact with the belt surface, provides high-resolution thickness measurement and delamination detection [6]. Together, these examples illustrate how different sensing principles are implemented in practice and demonstrate the diversity of installation configurations in modern conveyor-belt monitoring systems.

Figure 10.

Examples of industrial installations of diagnostic systems for conveyor belt monitoring: (a) Vision-based monitoring unit installed above a BECS conveyor belt for continuous detection of foreign objects and surface anomalies [54]; (b) Autonomous inspection robot equipped with RGB and infrared cameras for underground conveyor monitoring [63]; (c) Magnetic flux leakage (MFL) head of the DiagBelt system installed beneath the return strand for real-time inspection of steel-cord conveyor belts [62]; (d) Ultrasonic BeltSonic module mounted in contact with the belt surface for thickness measurement and delamination detection [6].

Multidimensional Comparison of Diagnostic Techniques

To enhance the engineering relevance of this review, the diagnostic methods were evaluated using a multidimensional set of criteria reflecting practical deployment considerations in industrial environments. In addition to defect type and operating mode, the comparison now incorporates (i) detection accuracy, indicating the achievable spatial, thermal, or signal-based resolution; (ii) environmental applicability, describing operational robustness under dust, variable lighting, humidity, vibration and temperature fluctuations typical of mining conditions; (iii) implementation cost, expressed qualitatively as a relative investment level; and (iv) Technology Readiness Level (TRL), assessing the maturity of each method from experimental research to industrial deployment.

This extended comparison (Table 3) provides a more comprehensive framework for selecting appropriate diagnostic approaches, supporting practical decision-making in conveyor belt maintenance and monitoring.

Table 3.

Multidimensional comparison of conveyor belt diagnostic methods.

6. Discussion

The reviewed literature confirms that non-invasive conveyor belt diagnostics have emerged as a key research and industrial development direction in modern bulk material transport systems. Over the past decade, a clear shift has occurred from manual and periodic inspections toward sensor-based, AI-assisted, and data-fusion-driven solutions. This trend is consistent with the global evolution of industrial digitalization and the Industry 4.0 paradigm.

Analysis of available technologies indicates that the highest diagnostic reliability is achieved by combining multiple sensing and NDT techniques, such as machine vision, infrared thermography, ultrasonics, and acoustics. Each of these methods provides unique insights into the belt’s condition—from surface-visible defects to internal structural faults and thermal anomalies. Examples of systems integrating vision and thermal sensors demonstrate that hybrid approaches enable early fault detection—before damage escalates into failure.

Despite the increasing number of research studies and pilot implementations, most reported systems still operate at a laboratory or semi-industrial scale. The full integration of remote diagnostic methods into industrial environments continues to face challenges related to sensor durability in dusty or humid conditions, lighting variability, and communication infrastructure scalability.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become an indispensable element of modern conveyor diagnostics. The use of neural network architectures (CNN, LSTM, GAN) enables automatic defect classification, reduction in human errors, and trend analysis of material degradation based on large sensor datasets. Recent literature reveals a transition from traditional ML classifiers (SVM, k-NN) to deep learning architectures and edge-AI implementations, where data are processed directly on edge devices, minimizing latency and bandwidth use.

However, a major challenge remains the lack of open, standardized, and representative datasets containing real industrial data. Most studies rely on limited proprietary datasets, which hinders method comparability and training of generalized models. A potential solution is the development of open diagnostic data repositories, in line with FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable), to accelerate research and standardize benchmarking procedures.

Despite rapid technological progress, the industrial deployment of remote diagnostic systems still faces practical barriers, including:

- The need for regular calibration and sensor maintenance in dusty environments,

- The diversity of belt types and conveyor constructions, which complicates measurement standardization,

- The cost of implementing multi-sensor systems and their integration with existing SCADA infrastructures,

- The shortage of skilled personnel for diagnostic data interpretation and system operation.

It is worth emphasizing that even a partially automated diagnostic system can deliver significant operational savings. According to Pulcini and Modoni (2024), reducing the number of unplanned downtimes by 10–15% corresponds to a reduction in maintenance labor time by several dozen hours per year in large open-pit mining operations.

The digital twin (DT) concept represents a natural extension of remote diagnostic systems. When combined with AI algorithms, it allows for a dynamic virtual representation of the conveyor’s physical behavior, enabling real-time degradation prediction of components. The adoption of digital twins opens new possibilities for predictive maintenance, allowing systems to analyze sensor data trends and simulate potential failure scenarios. Studies (e.g., Pulcini and Modoni, 2024) have shown that integrating DT with ML models allows the prediction of the remaining useful life (RUL) of a conveyor belt with 5–10% accuracy, which represents a significant improvement over traditional diagnostic methods.

Nevertheless, implementing a digital twin in an industrial environment requires advanced computational infrastructure, high-quality input data, and tight synchronization between physical and virtual domains.

The lack of interoperable data exchange standards (e.g., OPC UA, MQTT) currently remains one of the main obstacles to further development in this field.

The literature analysis highlights several key directions for future research in remote conveyor belt diagnostics:

- Development of open diagnostic databases for training AI models,

- Advancement of environmentally robust sensors capable of operating under dust, humidity, temperature, and vibration extremes,

- Integration of vision, acoustic, thermal, and operational data into a unified sensor fusion ecosystem,

- Industrial deployment and validation of digital twin systems,

- Development of data communication standards and interoperability frameworks between sensors and control systems.

Although the reviewed diagnostic techniques offer significant potential for improving conveyor belt monitoring, their practical implementation is subject to several important limitations. A first obstacle concerns economic feasibility: high-performance magnetic flux leakage systems, hyperspectral sensors and radar-based solutions involve substantial capital costs and may be economically justified only in large-scale operations. In contrast, low-cost sensing such as vibration MEMS often lacks the spatial resolution required for precise localisation of defects.

A second challenge relates to environmental adaptability. Vision-based methods remain sensitive to dust, variable lighting and contamination of the belt surface; ultrasonic inspection requires stable coupling conditions; and acoustic approaches are affected by the high background noise typical of mining environments. Infrared thermography, while robust in low-light conditions, depends on sufficient thermal contrast and may be influenced by ambient thermal gradients.

Another barrier concerns data quality and interpretability. Multisensor systems generate large volumes of heterogeneous data that require advanced processing pipelines and expert configuration. In many cases, the lack of high-quality labelled datasets limits the development of generalisable AI models for defect detection.

Integration complexity also hinders broader adoption. Installation space constraints, the need for precise sensor alignment (e.g., in MFL systems), and maintenance requirements for moving components or optical modules can reduce system reliability and increase operational costs. Furthermore, compatibility with existing SCADA systems and cybersecurity considerations remain important practical issues.

To address these limitations, several directions for further research can be proposed. Cost barriers may be mitigated through modular sensor architectures and hybrid monitoring strategies combining low-cost sensing with periodic high-resolution inspection. Environmental robustness can be enhanced through improved optical shielding, adaptive illumination, noise-resilient acoustic filtering, and machine-learning-based signal cleaning. Advanced data fusion frameworks and self-calibrating algorithms have the potential to simplify system integration while increasing sensitivity to early-stage defects. Finally, the development of open benchmark datasets and digital-twin environments would support more reliable training and verification of diagnostic algorithms in realistic conditions.

This analysis highlights that while state-of-the-art diagnostic technologies offer clear benefits, overcoming their implementation obstacles remains essential for achieving widespread industrial adoption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R. and L.J.; methodology, A.R. and L.J.; software, A.R.; validation, L.J. and R.B.; formal analysis, A.R. and L.J.; investigation, R.B.; resources, A.R. and R.B.; data curation, A.R. and R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R. and L.J.; writing—review and editing, A.R., L.J. and R.B.; visualization, A.R.; supervision, R.B.; funding acquisition, R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Harrison, A. Article Real-Time Conveyor Belt NDT by Telemonitoring. Bulk. Solids Handl. 2000, 20, 313–316. [Google Scholar]

- Błażej, R.; Jurdziak, L.; Rzeszowska, A. Sensor-Based Diagnostics for Conveyor Belt Condition Monitoring and Predictive Refurbishment. Sensors 2025, 25, 3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchorab-Matuszewska, N.; Kawalec, W.; Król, R. Study of Long-Distance Belt Conveying for Underground Copper Mines. Energies 2025, 18, 4872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawalec, W. Przenośniki Taśmowe Dalekiego Zasięgu Do Transportu Węgla Brunatnego. Transp. Przemysłowy I Masz. Rob. 2009, 1, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bugaric, U.; Tanasijevic, M.; Polovina, D.; Ignjatovic, D.; Jovancic, P. Lost Production Costs of the Overburden Excavation System Caused by Rubber Belt Failure. Eksploat. I Niezawodn. 2012, 14, 333–341. [Google Scholar]

- Kirjanów-Błażej, A.; Błażej, R.; Jurdziak, L.; Kozłowski, T.; Rzeszowska, A. Innovative Diagnostic Device for Thickness Measurement of Conveyor Belts in Horizontal Transport. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semrád, K.; Draganová, K. Non-Destructive Testing of Pipe Conveyor Belts Using Glass-Coated Magnetic Microwires. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siami, M.; Barszcz, T.; Wodecki, J.; Zimroz, R. Automated Identification of Overheated Belt Conveyor Idlers in Thermal Images with Complex Backgrounds Using Binary Classification with CNN. Sensors 2022, 22, 10004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, C. Research on the Tear Prevention Monitoring System for Belt Conveyors Based on Multi-Sensor Fusion. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, and Information Engineering (EEIE 2024), Bangkok, Thailand, 16–18 August 2024; Malik, H., Ed.; SPIE: St. Bellingham, WA, USA, 2025; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Bajda, M.; Błażej, R.; Jurdziak, L. Analysis of Changes in the Length of Belt Sections and the Number of Splices in the Belt Loops on Conveyors in an Underground Mine. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 101, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurdziak, L.; Błażej, R.; Kirjanów-Błażej, A.; Rzeszowska, A. Comparison of Different Metrics of Belt Condition Used in Lignite Mines for Taking Decision about Belt Segments Replacement and Refurbishment. In Intelligent Systems in Production Engineering and Maintenance III.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 501–518. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Zhong, S.; Lee, T.-L.; Fancey, K.S.; Mi, J. Non-Destructive Testing and Evaluation of Composite Materials/Structures: A State-of-the-Art Review. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2020, 12, 168781402091376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurdziak, L.; Blazej, R.; Bajda, M. Conveyor Belt 4.0. In Proceedings of the Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Bhubaneswar, India, 21–23 December 2019; Volume 835. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorko, G. Implementation of Industry 4.0 in the Belt Conveyor Transport. MATEC Web Conf. 2019, 263, 01001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, D.; Gaspar, P.D.; Charrua-Santos, F.; Navas, H. Enhanced Real-Time Maintenance Management Model—A Step toward Industry 4.0 through Lean: Conveyor Belt Operation Case Study. Electronics 2023, 12, 3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirjanów-Błażej, A.; Jurdziak, L.; Błażej, R.; Rzeszowska, A. Calibration Procedure for Ultrasonic Sensors for Precise Thickness Measurement. Measurement 2023, 214, 112744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericeira, D.R.; Rocha, F.; Bianchi, A.G.C.; Pessin, G. Early Failure Detection of Belt Conveyor Idlers by Means of Ultrasonic Sensing. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Krampikowska, A.; Świt, G. Acoustic Emission for Diagnosing Cable Way Steel Support Towers. MATEC Web Conf. 2019, 284, 09002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziehl, P.; ElBatanouny, M. Acoustic Emission Monitoring for Corrosion Damage Detection and Classification. In Corrosion of Steel in Concrete Structures; Elsevier: New York, NK, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Pei, D.; Lodewijks, G.; Zhao, Z.; Mei, J. Acoustic Signal Based Fault Detection on Belt Conveyor Idlers Using Machine Learning. Adv. Powder Technol. 2020, 31, 2689–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoczylas, A.; Stefaniak, P.; Anufriiev, S.; Jachnik, B. Belt Conveyors Rollers Diagnostics Based on Acoustic Signal Collected Using Autonomous Legged Inspection Robot. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błażej, R.; Jurdziak, L.; Kozłowski, T.; Kirjanów, A. The Use of Magnetic Sensors in Monitoring the Condition of the Core in Steel Cord Conveyor Belts—Tests of the Measuring Probe and the Design of the DiagBelt System. Measurement 2018, 123, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indrasari, W.; Djamal, M.; Srigutomo, W.; Hadziqoh, N. High Sensitivity Fluxgate Sensor for Detection of AC Magnetic Field: Equipment for Characterization of Magnetic Material in Subsurface. In Proceedings of the Advanced Materials Research, Macau, China, 22–23 January 2014; Volume 896. [Google Scholar]

- Roskosz, M.; Mazurek, P.; Kwaśniewski, J.; Wu, J. Use of Different Types of Magnetic Field Sensors in Diagnosing the State of Ferromagnetic Elements Based on Residual Magnetic Field Measurements. Sensors 2023, 23, 6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witoś, M.; Zieja, M.; Żokowski, M.; Kwaśniewski, J.; Iwaniec, M. NDE of Mining Ropes and Conveyors Using Magnetic Methods. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Structural Health Monitoring and Nondestructive Testing, Saarbrücken, Germany, 4–5 October 2018; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xin, R. Magnetic Flux Detection and Identification of Bridge Cable Metal Area Loss Damage. Measurement 2021, 167, 108443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błazej, R.; Jurdziak, L.; Kirjanów, A.; Kozłowski, T. Evaluation of the Quality of Steel Cord Belt Splices Based on Belt Condition Examination Using Magnetic Techniques. Diagnostyka 2015, 16, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek, P.; Kwaśniewski, J.; Roskosz, M.; Siwoń-Olszewski, R. The Use of a Magnetic Flux Leakage in the Assessment of the Technical State of a Steel Wire Rope Subjected to Bending. J. KONBiN 2018, 48, 493–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, Q.S. Sensor Selection Approach for Damage Identification Based on Response Sensitivity. Struct. Monit. Maint. 2017, 4, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siami, M.; Barszcz, T.; Wodecki, J.; Zimroz, R. Design of an Infrared Image Processing Pipeline for Robotic Inspection of Conveyor Systems in Opencast Mining Sites. Energies 2022, 15, 6771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagavathiappan, S.; Lahiri, B.B.; Saravanan, T.; Philip, J.; Jayakumar, T. Infrared Thermography for Condition Monitoring—A Review. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2013, 60, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Qiao, T.; Pang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yan, G. Infrared Spectrum Analysis Method for Detection and Early Warning of Longitudinal Tear of Mine Conveyor Belt. Measurement 2020, 165, 107856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-W.; Park, S. Magnetic Flux Leakage Sensing and Artificial Neural Network Pattern Recognition-Based Automated Damage Detection and Quantification for Wire Rope Non-Destructive Evaluation. Sensors 2018, 18, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olchówka, D.; Rzeszowska, A.; Jurdziak, L.; Błażej, R. Statistical Analysis and Neural Network in Detecting Steel Cord Failures in Conveyor Belts. Energies 2021, 14, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirjanów-Błażej, A.; Rzeszowska, A. Conveyor Belt Damage Detection with the Use of a Two-Layer Neural Network. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihnastyi, O.; Ivanovska, O. Improving the Prediction Quality for a Multi-Section Transport Conveyor Model Based on a Neural Network. In Proceedings of the CEUR Workshop Proceedings, Örebro, Sweden, 15–17 June 2022; Volume 3132. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Liu, X.; Królczyk, G.; Sulowicz, M.; Glowacz, A.; Gardoni, P.; Li, Z. Damage Detection for Conveyor Belt Surface Based on Conditional Cycle Generative Adversarial Network. Sensors 2022, 22, 3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, Z.; Sun, H.; Zhu, C.; Yang, Z. Yolox-BTFPN: An Anchor-Free Conveyor Belt Damage Detector with a Biased Feature Extraction Network. Measurement 2022, 200, 111675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, C.; Sikorska, J.; Khan, R.N.; Hodkiewicz, M. Developing and Evaluating Predictive Conveyor Belt Wear Models. Data-Centric Eng. 2020, 1, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, D.; Lodewijks, G.; Pang, Y.; Mei, J. Integrated Decision Making for Predictive Maintenance of Belt Conveyor Systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019, 188, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, P.; Jurdziak, L.; Rzeszowska, A.; Burduk, A. Predictive Modeling of Conveyor Belt Deterioration in Coal Mines Using AI Techniques. Energies 2024, 17, 3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Yin, H.; Wang, K. Prediction of the Remaining Useful Life of Supercapacitors at Different Temperatures Based on Improved Long Short-Term Memory. Energies 2023, 16, 5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirjanów-Błażej, A.; Jurdziak, L.; Burduk, R.; Błażej, R. Forecast of the Remaining Lifetime of Steel Cord Conveyor Belts Based on Regression Methods in Damage Analysis Identified by Subsequent DiagBelt Scans. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 100, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrejiova, M.; Grincova, A.; Marasova, D. Measurement and Simulation of Impact Wear Damage to Industrial Conveyor Belts. Wear 2016, 368–369, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafia, M.M.P.; Ayoub, N.; Trumpler, L.; de Oliveira Hansen, J.P. A Digital Twin Design for Conveyor Belts Predictive Maintenance. In Machine Learning for Cyber-Physical Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Pulcini, V.; Modoni, G. Machine Learning-Based Digital Twin of a Conveyor Belt for Predictive Maintenance. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 133, 6095–6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindyk, E.; Bajda, M.; Jurdziak, L. Tests of Conveyor Belt Resistance to Abrasion. Transp. Przemysłowy I Masz. Rob. 2019, 2, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nins, B.; Penagos, J.J.; Moreira, L.; Münch, D.; Falqueto, P.; Viáfara, C.C.; da Costa, A.R. Abrasiveness of Iron Ores: Analysis of Service-Worn Conveyor Belts and Laboratory Dry Sand/Rubber Wheel Tests. Wear 2022, 506–507, 204439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostrzewa, P. Wykorzystanie Systemu DiagBelt Do Identyfikacji Symulowanych Uszkodzeń Na Stanowisku Badawczym. Master’s Thesis, Wrosław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, J.R.; Cavalieri, D.C.; Prado, A.R. Efficient Monitoring of Longitudinal Tears in Conveyor Belts Using 2D Laser Scanner and Statistical Methods. Measurement 2024, 227, 114225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błażej, R.; Jurdziak, L.; Kirjanów-Błażej, A.; Bajda, M.; Olchówka, D.; Rzeszowska, A. Profitability of Conveyor Belt Refurbishment and Diagnostics in the Light of the Circular Economy and the Full and Effective Use of Resources. Energies 2022, 15, 7632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostrzewa, P. Kwalifikacja i Regeneracja Taśm Przenośnikowych Typu St w BestGum Polska Sp. z o.o. Bachelor’s Thesis, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Rau, L.; Zhang, Y.; Oelmann, B.; Bader, S. On-Device Anomaly Detection in Conveyor Belt Operations. Prepr. Submitt. IEEE OPEN J. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kia, S.; Leiding, B. Intelligent Monitoring of BECS Conveyors via Vision and the IoT for Safety and Separation Efficiency. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, S. Sound-Based Improved DenseNet Conveyor Belt Longitudinal Tear Detection. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 123801–123808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szurgacz, D.; Zhironkin, S.; Vöth, S.; Pokorný, J.; Sam Spearing, A.J.S.; Cehlár, M.; Stempniak, M.; Sobik, L. Thermal Imaging Study to Determine the Operational Condition of a Conveyor Belt Drive System Structure. Energies 2021, 14, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siami, M.; Barszcz, T.; Wodecki, J.; Zimroz, R. Semantic Segmentation of Thermal Defects in Belt Conveyor Idlers Using Thermal Image Augmentation and U-Net-Based Convolutional Neural Networks. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, F.; Luo, S.; Zhang, H.; Shaukat, K.; Yang, G.; Wheeler, C.A.; Chen, Z. A Brief Review of Acoustic and Vibration Signal-Based Fault Detection for Belt Conveyor Idlers Using Machine Learning Models. Sensors 2023, 23, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskosz, M.; Złocki, A.; Kwaśniewski, J. Self Magnetic Flux Leakage as a Diagnostic Signal in the Assessment of Active Stress—Analysis of Influence Factors. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2020, 137, 690–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]