Abstract

MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4 were successfully synthesized on a stainless-steel substrate using the hydrothermal method. The structural and morphological characteristics of the spinel samples were investigated using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The electronic and vibrational properties were studied through X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). Electrochemical properties were also evaluated using a three-electrode system associated with an electrochemical workstation. The studies revealed that the inversion of Mn and Co cation distribution between the spinel structure sites not only modifies the crystal structure and morphology but also alters specific functional properties. MnCo2O4 crystallized in a cubic spinel phase, exhibiting spherical particles, pronounced microstrain, and stronger metal–oxygen bonding. In contrast, CoMn2O4 adopted a tetragonal spinel structure with rod-like crystallites, lower microstrain, and more flexible bonding environments. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy further revealed distinct charge-transfer dynamics, indicating differences in surface redox activity. This comparative analysis elucidates how cation site occupancy governs the performance of the synthesized spinel oxides and underscores their potential as efficient catalysts or catalyst supports for redox and energy-related applications.

1. Introduction

Transition metal oxides with a spinel structure are a diverse class of materials that have attracted substantial interest due to their structural flexibility, redox activity, and versatility across a wide range of applications. Among these, manganese cobaltite (MnCo2O4) and cobalt manganite (CoMn2O4) stand out for their potential in catalysis [1,2,3], sensing [4,5,6], and energy storage applications [7,8,9,10], attributable to their unique cation arrangements and to their exceptional optical, electrical, magnetic, electrochemical, and catalytic qualities [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Co-Mn spinels are excellent catalyst candidates owing to their abundant redox-active cations (Co3+/Co2+ and Mn3+/Mn2+) and high structural stability, which facilitate efficient charge transfer and oxygen-related surface reactions. The formula for the spinel structure is typically AB2O4. The A-site cations fill 1/8 of the tetrahedral holes, and the B-site cations fill 1/2 of the octahedral holes. In total, 64 tetrahedral and 32 octahedral are present in the spinel unit cell. Of these, 8 tetrahedral and 16 octahedral sites are occupied by the A and B cations. This results in 56 tetrahedral and 16 octahedral empty sites remaining in the structure’s interstitial space, significantly benefiting electron transfer [17,18,19]. In MnCo2O4, manganese predominantly occupies the tetrahedral A site, while cobalt occupies the octahedral B site, whereas in CoMn2O4, this distribution is reversed [20,21]. This inversion of cation site occupancies affects several properties, including the electronic structure, morphology, and vibrational behavior. Whether it is the first configuration or the second one, the combination of manganese (Mn) and cobalt (Co) in both spinels, MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4, creates synergistic effects that enhance the electrochemical properties through the presence of multiple redox-active metal centers that will facilitate the charge transfer, resulting in improved electrochemical performance [22,23]. The site-specific occupation of cations in a spinel structure is known to impact its electronic conductivity, magnetic interactions, and surface redox characteristics [24,25,26,27,28], which are crucial for applications such as catalysis, energy storage, magnetic data storage, and chemical sensors [27,29,30,31].

The present work investigates the synthesis and characterization of hydrothermally synthesized MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4 directly on a stainless-steel (SS) substrate, providing an adaptable, conductive support for various electrochemical applications. Although other synthesis techniques have been used to obtain those spinels, including co-precipitation [32] and sol–gel [33], hydrothermal synthesis enables precise control over the crystalline and morphological characteristics of the samples [34]. This method is particularly advantageous for preparing spinel oxides on substrates such as SS, as it enables the production of uniform, well-adhered nanostructures under controlled conditions. The SS substrate not only serves as a mechanical support but also provides good conductivity and corrosion resistance, making it an excellent substrate for integrating such materials in electrochemical and sensing devices [35].

By investigating the impact of cation site inversion on these properties, this work elucidates how specific site distributions in spinel oxides can be exploited to optimize multifunctional materials with tunable electronic, vibrational, and electrochemical properties. Using a multi-characterization approach comprising XRD, SEM, FTIR, and EIS analyses, this study correlates cationic site occupancy with structural distortion, bond strength, morphology, and charge-transfer behavior. This research contributes to a deeper understanding of the relationships between structural properties in AB2O4 spinels. As the properties of MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4 are examined, their structural, morphological, vibrational, and electrochemical characteristics are investigated to elucidate the synergistic effects of Mn and Co atoms within the spinel structure, which is crucial for designing catalysts with optimized activity and stability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hydrothermal Synthesis of MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4 on a SS Substrate

All substances used in this work are acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4 spinel particles were synthesized hydrothermally on a stainless-steel substrate (Bolin Metal Wire Mesh Co., Ltd., Hengshui, China), under identical conditions, with the only variation in the initial Co:Mn stoichiometry. The SS substrates (35 µm thick) were cut into 2 cm × 5 cm rectangles and pre-treated prior to hydrothermal deposition. The substrates were briefly immersed in 10−3 M HCl, rinsed, then ultrasonically cleaned in acetone and ethanol for 10 min each. Finally, they were rinsed thoroughly with distilled water and dried at room temperature. Manganese acetate tetrahydrate (Mn(CH3COO)2⋅4H2O) and cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO3)2⋅6H2O) were employed as precursors in a 1:2 M and 2:1 ratios, respectively, for MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4. The solution was composed of the precursors dissolved in 20 mL of distilled water and a 5 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution, which was gradually added until the solution’s pH reached 10. It was then transferred to a Teflon autoclave vessel, where the sample was placed. The reaction temperature and time were set to 180 °C and 24 h, respectively. After being removed from the autoclave, the sample was cleaned with distilled water and annealed for 2 h at 400 °C. The mass loadings of the deposited MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4 layers were determined gravimetrically (MnCo2O4: 1.6 mg cm−2; CoMn2O4: 3.1 mg cm−2). Both coatings remained firmly attached after rinsing and mechanical handling, indicating good interfacial bonding.

2.2. Materials Characterization

A Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Bruker Inc., Billerica, MA, USA) was used to analyze the crystal structure of the material at room temperature using Cu Kα (λ = 1.541 Å) radiation. A PerkinElmer FT-IR spectrometer (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) was employed to perform attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) measurements. A Hitachi model S-2400 scanning electron microscope (Hitachi Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was used to collect scanning electron microscopy images (SEM). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) data were collected using a Kratos XSAM800 non-monochromatic, dual-anode spectrometer (Kratos Analytical Ltd., Manchester, UK). X-rays with the main line Al Kα, with energy equal to 1486.6 eV, were used for sample irradiation. Software programs used for data acquisition and data treatment, as well as the fitting and quantification details, were published elsewhere [36].

2.3. Electrochemical Measurements

A three-electrode system associated with a Squidstat Plus electrochemical workstation (Admiral Instruments, Tempe, AZ, USA) was utilized to evaluate the electrochemical properties of the electrodes. The electrolyte was composed of a 1 M Na2SO4 solution (100 mL). The working electrode was the spinel/SS sample. The counter and reference electrodes were a platinum mesh and a HANNA Instruments HI5412 saturated calomel electrode (SCE), respectively. The electrochemical properties were investigated using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) in the frequency range of 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz with an AC perturbation amplitude of 5 mV. The impedance data were fitted using an appropriate equivalent circuit to extract the charge-transfer resistance and other relevant parameters.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

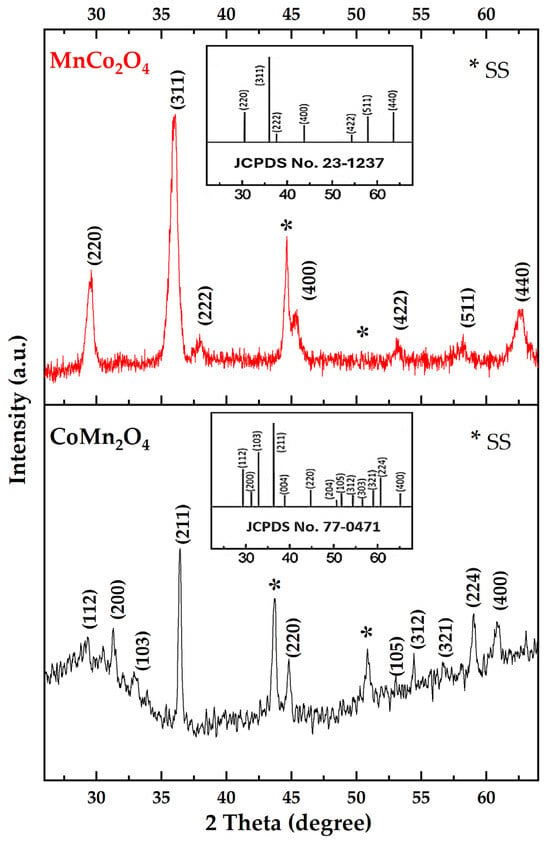

The XRD patterns of the synthesized MnCo2O4/SS and CoMn2O4/SS are shown in Figure 1. From the shape of the diffraction peaks, it can be concluded that both samples are well crystallized. For MnCo2O4, the peaks are sharp and intense. They are assigned to the (hkl) planes (220), (311), (222), (400), (422), (511), and (440), which are characteristic of a spinel cubic phase (JCPDS No. 23-1237), with the Fd-3m space group [14]. In contrast, for CoMn2O4, more complex diffraction features are observed. They are related to (hkl) planes (112), (200), (103), (211), (105), (312), (220), (321), (224), (400), and (305), which are consistent with a tetragonal distortion (JCPDS No. 77-0471), in the I41/AMD space group [14].

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of MnCo2O4/SS and CoMn2O4/SS, with the corresponding reference patterns based on JCPDS cards [23-1237] and [77-0471] included as insets.

The Debye-Scherrer formula was used to calculate the crystallite sizes D of the samples using the following Equation (1) [37],

where D is the average crystallite size, θ represents the Bragg’s angle, λ represents the X-ray wavelength, β represents the XRD peak width at FWHM (full width half maximum), and K is known as the Scherrer constant (K = 0.94). The Williamson-Hall relation was also used to calculate the microstrain ε for both samples using Equation (2) [38].

The lattice parameter a of all samples can be calculated for the cubic structure using Equation (3).

For the tetragonal phase, the c/a ratio can be determined using Equation (4),

where a and c are the lattice parameters, h, k, and l are the Miller indices, and d is the interplanar distance.

Table 1 summarizes the structural and microstructural parameters extracted from XRD using the equations above. MnCo2O4 exhibits a cubic-like average cell (a = 8.40 Å), small coherent domain sizes (D = 12.3 nm) and a high microstrain (ε = 9.11 × 10−3), whereas CoMn2O4 is best described by a tetragonal unit cell (a = 6.156 Å, c = 9.059 Å, c/a = 1.47), larger coherent domains (D = 32.2 nm) and lower microstrain (ε = 3.45 × 10−3).

Table 1.

Lattice parameters, microstrain, average crystallite size, and grain size of MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4.

For Co-rich composition (MnCo2O4), most Co3+ ions stabilize on octahedral sites while Mn2+ tends to occupy tetrahedral sites due to its larger ionic radius and lower charge. This relatively balanced distribution between A and B sites preserves cubic symmetry and isotropy. On the other hand, the observed higher microstrain, correlating with its small crystallite size and finer grain morphology, might be due to Jahn–Teller activity in octahedral coordination, which promotes rapid nucleation of small-strain-rich particles, especially in sol–gel and hydrothermal synthesis methods [39]. Knowing that Co3+ ions reside in octahedral coordination, they can be Jahn–Teller active only if they have a high-spin state (t2g4 e g2), which is not the case, as will be seen in the XPS analysis. However, mixed valence states and possible site disorder, as Co3+ and Mn2+ might be sharing sites [40] can introduce local strain fields due to Jahn–Teller activity in the octahedral coordination of Mn3+, potentially distributed across octahedral sites. The cubic symmetry does not readily accommodate Jahn–Teller distortions, which explains the observed higher strain. MnCo2O4 has a cubic spinel structure, which is more rigid and less tolerant to local distortions, leading to higher microstrain.

In the case of an Mn-rich composition in CoMn2O4, Mn3+ ions are more likely to occupy octahedral sites, where they are Jahn–Teller active. However, the tetragonal distortion in CoMn2O4 already partially accommodates the Jahn–Teller effect, reducing the need for further local distortion. CoMn2O4 adopts a tetragonal spinel structure, which inherently accommodates some distortion due to the elongated C-axis (c/a = 1.472). This structural flexibility allows the lattice to relax internal stress, resulting in lower microstrain. The lower microstrain is therefore primarily due to the tetragonal structure, which provides greater flexibility to accommodate Jahn–Teller distortions from Mn3+ ions. Additionally, a more ordered cation distribution and reduced site disorder contribute to the lower strain. It should be noted that this interpretation is a plausible hypothesis grounded in mechanisms reported in the literature [41,42]. While the present data do not directly resolve local Jahn–Teller distortions, the discussion provides a coherent framework consistent with the observed structural and microstructural trends.

XRD patterns alone do not allow a quantitative determination of the inversion parameter because Mn and Co have similar scattering factors. Therefore, the cation distribution discussed here is inferred from the observed symmetry, the literature, and the correlation with vibrational/electrochemical properties.

3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

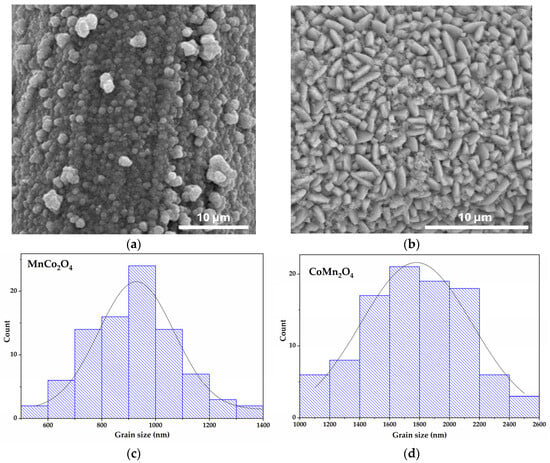

Both MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4 coatings exhibited very similar surface color and appearance, due to their comparable Co–Mn oxide composition and the uniformity of the hydrothermal deposition on stainless steel. No delamination, cracks, or exposed metal regions were observed, confirming strong adhesion and uniform deposition on the SS substrate. While the macroscopic appearance of both films is similar, the SEM images of MnCo2O4/SS and CoMn2O4/SS, shown in Figure 2, reveal full and homogeneous coverage of the SS substrate and clearly distinguish morphologies that reflect the influence of structural symmetry on the growth habits of the two spinels. In the case of MnCo2O4 (Figure 2a), the surface is composed of densely packed spherical particles, forming a continuous granular coating. In contrast, CoMn2O4 (Figure 2b) shows a distinct morphology, characterized by needle-like crystallites distributed uniformly over the surface. These anisotropic structures suggest preferential growth along specific crystallographic directions and may exhibit lower surface roughness than MnCo2O4. For both samples, the homogeneous coverage of the substrate demonstrates the adequacy of the hydrothermal synthesis technique used. On the other hand, the clear morphological contrast between the two compositions underscores the significant influence of stoichiometry on nucleation and growth mechanisms during synthesis. The distinct morphologies originate from the interplay between cationic distribution, redox kinetics, and surface energy effects [43]. Particle size distributions (Figure 2c,d) are extracted from SEM images using the ImageJ software (v. 1.54i) by averaging the Feret diameters of at least 80 grains per sample. While XRD analysis confirms that the primary crystallites are nanosized (12–32 nm), the observed SEM features of ~900–1800 nm correspond to agglomerated grains, clusters of many crystallites. This is completely expected for hydrothermally grown spinel oxides, where nanosized crystallites often self-assemble into much larger secondary structures [44].

Figure 2.

SEM micrographs at a magnification of ×3000 of (a) MnCo2O4 and (b) CoMn2O4, and grain size distribution of (c) MnCo2O4 and (d) CoMn2O4.

MnCo2O4 exhibits a dense layer of spherical particles forming a continuous granular coating. This is consistent with its high microstrain and small crystallite size, suggesting rapid nucleation and limited directional growth. This isotropic morphology aligns with the cubic symmetry of MnCo2O4, and the strain-induced fragmentation is likely driven by Jahn–Teller-active Mn3+ ions. In MnCo2O4, Mn3+ ions at octahedral sites, possibly due to mixed valence states and possible site disorder, introduce Jahn–Teller distortions and higher defect concentrations [42], while the fast Mn2+/Mn3+ redox kinetics promote rapid isotropic nucleation [45]. Combined with similar surface energies across crystallographic planes, these factors yield uniformly distributed spherical particles [32]. In contrast, CoMn2O4, with more Co ions occupying octahedral positions, exhibits slower hydrolysis kinetics and a preferential stabilization of specific planes. MnCo2O4 favors isotropic nucleation, resulting in spherical particles [46]. CoMn2O4 exhibits needle-like crystallites with pronounced anisotropy, indicating preferential growth along specific crystallographic directions. This behavior correlates with its tetragonal structure, lower microstrain, and larger crystallite size, which favor directional crystal growth [47]. The morphological contrast between the two samples highlights the influence of redox behavior and crystal symmetry on nucleation and growth mechanisms during hydrothermal synthesis. This difference in morphology is expected to affect the materials’ performance, as spherical MnCo2O4 may enhance surface-related processes and reactivity. In contrast, anisotropic CoMn2O4 could provide advantages in directional transport and structural stability. The uniform substrate coverage in both cases confirms the effectiveness of the synthesis method in producing adherent and homogeneous coatings.

3.3. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

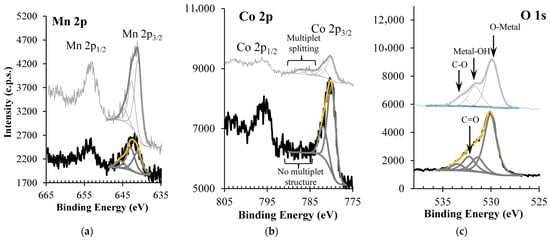

XPS analyses were used to assess the oxidation states of the metals and the overall composition of the (Mn, Co)-based spinel structure. Figure 3 shows the detailed regions Mn 2p, Co 2p, and O 1s. The qualitative and quantitative analyses of both CoMn2O4 and MnCo2O4 are shown in Table S1 (Supporting Information).

Figure 3.

XPS regions of (a) Mn 2p, (b) Co 2p, and (c) O 1s of MnCo2O4 (in black). The spectrum of CoMn2O4 (studied previously in [36]) is also shown for comparison purposes (in gray).

Mn 2p is a doublet peak with a spin–orbit split equal to 11.5 ± 0.1 eV (Figure 3a). The Mn 2p3/2 component of the MnCo2O4 sample was fitted with three peaks centered at 641.2 ± 0.1 eV, 642.9 ± 0.1 eV, and 645.5 ± 0.1 eV.

The assignment of each peak beyond any doubt is not a straightforward task, particularly when a mixture of oxidation states seems to exist. The comparison of this Mn 2p region with spectra of manganese oxides and oxyhydroxides from Biesinger et al. [48] reveals that even stoichiometric compounds display broad, complex peaks that are easily misidentified. Nevertheless, the peak at 641.2 ± 0.1 eV coincides with the most intense fitted peak in MnO [48], 642.9 ± 0.1 eV with that of Mn2O3 or MnOOH, and 645.5 ± 0.1 eV with a shake-up satellite, which is more prominent in the Mn2+ oxide. One must bear in mind that comparisons between binding energies obtained from different studies can be misleading, particularly when spectra are corrected for charge shift (resulting from charge accumulation during XPS measurements) using different strategies, as is the case in the present study and the one referred to. A known method to overcome these most probable slight dispersions of values is to rely on the energy distance between the Mn 3s photoelectron and its satellite (ΔBE(Mn 3s: photoelect.-sat.)), which does not depend on the charge shift correction method, and is known to be affected by the Mn oxidation state [49]. In the case of CoMn2O4, ΔBE(Mn 3s: photoelect.-sat.) shows that the predominant oxidation state is Mn (III) [36]. However, in the case of this MnCo2O4 sample, where cobalt is in a larger amount than manganese, the Mn 3s position is between two much more intense cobalt regions (Co 3p at ~61 eV and Co 3s at ~102 eV), and Mn 3s is barely detected, making its assignment doubtful (Figure S1).

Co 2p of MnCo2O4 sample is also a doublet peak with a spin–orbit separation of 15.3 ± 0.1 eV, having two fitted doublet peaks, with 2p3/2 components centered at 779.9 ± 0.1 eV and 781.8 ± 0.1 eV (Figure 3b), and with relative areas (A) obeying to the predicted multiplicity of states (which results in: Area2p3/2 = 2 × Area2p1/2. The same fitting criterion was used to fit Mn 2p). The position of the main peak (779.9 eV) can be either attributed to Co2+ or to a mixture of Co2+ and Co3+, and the low intensity peak (781.8 eV) has also been detected in CoO, Co(OH)2, CoOOH, and Co2O3 [48], showing that none of the peak positions is conclusive regarding the cobalt oxidation state. Yet, the Co 2p profile shows a notable feature: unlike the CoMn2O4 sample (gray spectrum), the MnCo2O4 sample lacks any multiplet structure (see also Figure S2). This multiplet structure, detected roughly between ~785 eV and ~793 eV, is typical of transition metals with unpaired valence electrons. The absence of the multiplet structure in the Co 2p region of MnCo2O4 can arise from a low-spin state, where all valence electrons are paired, which is only possible for Co3+ [50,51,52]

The quantitative analysis reveals that the experimental atomic ratio of Co/Mn is close to the expected value, although a high carbon content and an excess of oxygen are detected (Table 2). Carbon comes most probably from the synthesis’s solvents and/or reagents. Despite its high relative amount, it does not strongly attenuate the XPS regions of interest for this study, most probably because it is discontinuously distributed at the surface and/or is occluded in the outermost spinel material surface. The ratio of [total oxygen] to [oxygen in oxidized species] (O/Ooxides), given by the expression shown in Equation (5), should be equal to 1, confirming the assignments made (cf. Figure 3c). The ratio > 1 is compatible with the presence of hydroxides or oxyhydroxide species, which are not taken into account in this ratio, but were considered in O 1s, Mn 2p, and Co 2p fittings.

Table 2.

Atomic concentrations (%) and atomic ratios in MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4.

In Equation (5), C“C−O” corresponds to the atomic concentration (at.%) of carbon atoms singly bonded to oxygen (detected at 286.4 ± 0.1 eV), C“O−C=O” is the at.% of carbon atoms in ester groups (detected at 288.2 ± 0.1 eV), Mn and Co are the metal atoms in total at.% (assuming the stoichiometries MnCo2O4 or CoMn2O4), S is the residual at.% in sulfate groups (S 2p3/2 detected at 168.4 ± 0.1 eV in CoMn2O4), and Na corresponds to the at.% in NaOH (detected at 1071.2 ± 0.1 eV).

3.4. Attenuated Total Reflectance–Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR)

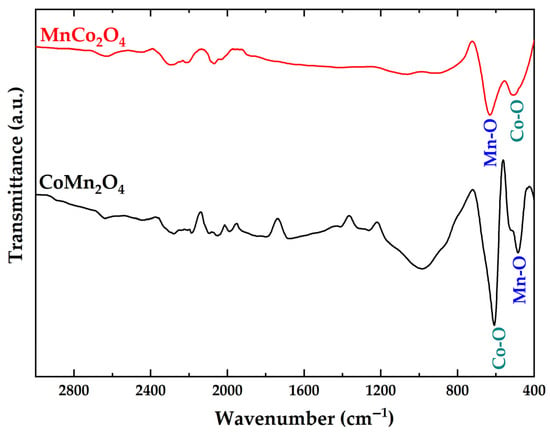

ATR-FTIR spectra of the MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4 (Figure 4) exhibit characteristic vibrational bands associated with metal–oxygen bonding in spinel structures. Both samples exhibit prominent absorption bands below 700 cm−1, corresponding to stretching vibrations of metal–oxygen M-O bonds at tetrahedral and octahedral sites. Specifically, the band near 580–620 cm−1 is attributed to M-O stretching in tetrahedral coordination, while the band around 480–520 cm−1 is associated with M-O vibrations in octahedral sites. The relative intensity and position of these bands differ between the two samples, reflecting variations in cation distribution and crystal symmetry [32]. The FTIR data thus reinforce the structural findings from XRD and SEM, confirming that the cationic arrangement and crystal-field effects significantly influence both vibrational and morphological properties.

Figure 4.

ATR-FTIR spectra of MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4.

FTIR-derived force constants can further reinforce the structural and morphological findings, as they are proportional to the metal ions’ atomic number, the oxygen ions’ atomic number, and to the length of the metal–oxygen bond [53,54]. This force can be calculated using Equation (6),

where F represents the force constant (N m−1), c denotes the velocity of light (2.99 × 108 m s−1), ν signifies the vibration frequency (s−1) observed at both tetrahedral and octahedral sites, and µ stands for the reduced mass (kg) concerning the cations and anions positioned within their respective tetrahedral and octahedral sites.

The evaluated values of the force constants for the stretching vibration of Co-O and Mn-O for MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4 are presented in Table 3. The constant force values change for both spinels, which confirms the occurring exchange in the tetrahedral and octahedral sites [28].

Table 3.

The calculated values of Co-O and Mn-O force constants for MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4.

For MnCo2O4, the vibrational modes appear at 630 cm−1 (Mn-O, tetrahedral site) and 508 cm−1 (Co-O, octahedral site), corresponding to force constants of 290.17 N/m and 191.59 N/m, respectively. In contrast, CoMn2O4 exhibits slightly lower wavenumbers at 608 cm−1 (Co-O, tetrahedral site) and 485 cm−1 (Mn-O, octahedral site), corresponding to reduced force constants of 274.45 N/m and 171.97 N/m, respectively. The results provide direct evidence of differences in bond strength and lattice rigidity between the two spinels. The higher Mn-O force constant in MnCo2O4 indicates stronger tetrahedral bonding consistent with its cubic symmetry, which is intrinsically more rigid and less tolerant to distortion. This rigidity explains the higher microstrain observed from XRD analysis. The enhanced bond strength also aligns with the small crystallite sizes and spherical isotropic morphology observed in SEM, indicating a fast nucleation under high strain and restricting directional crystal growth. By contrast, the lower Mn-O force constant in CoMn2O4 reflects weaker octahedral bonding, in line with the tetragonal distortion revealed by XRD. The reduced Co-O bond strength (274.45 N/m vs. 290.17 N/m in MnCo2O4) further supports this structural flexibility [55].

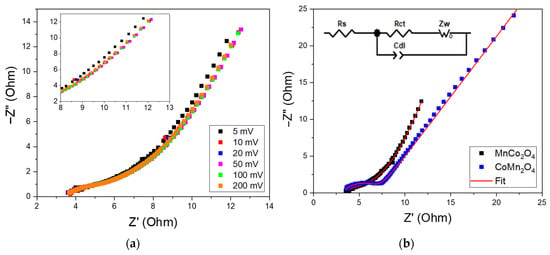

3.5. EIS Measurements

Figure 5a presents the EIS plots of the MnCo2O4 material recorded at different voltages. The analysis of these spectra reveals that the Nyquist plots follow a similar overall trend, with only a slight deviation in the diffusion tail observed at 5 mV. This behavior indicates that the system is generally stable and largely insensitive to changes in voltage, except at 5 mV, where slight alterations in electrochemical processes or interfacial properties emerge at low frequencies. This suggests the predominance of a non-Faradaic process. For comparison between MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4, the EIS plots recorded at 5 mV are shown in Figure 5b.

Figure 5.

(a) EIS Nyquist plot for MnCo2O4 compound with a zoom of the impedance spectroscopy response at low frequency as an inset. (b) Comparison between fitted curves of MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4 materials, with the inset showing the equivalent circuit.

The investigation of the Nyquist plots using ZView software (v. 4.0c) reveals that both compounds exhibit the same equivalent circuit, composed of the following elements: the electrolyte resistance, Rs, determined by the intersection of the impedance spectra with the real axis; a depressed semicircle representing the charge-transfer resistance, Rct, which is governed by electrostatic interactions at the electrode–electrolyte interface; and a constant phase element associated with the double-layer capacitance, Cdl, at the same interface [56]. The inclined line following the semicircle corresponds to the Warburg impedance, Zw, reflecting ion-diffusion kinetics within the porous electrode structure [32,45,57].

Comparing the total resistances of MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4, estimated at 6.06 and 7.21 Ω, respectively, MnCo2O4 displays higher electronic conductivity than the tetragonal CoMn2O4 structure. This enhanced conductivity can be attributed to several factors, notably the more symmetric spinel structure of MnCo2O4, which enables more efficient Co2+/Co3+ electron hopping pathways [58,59].

When comparing the capacitance of these two spinel oxides (Table 4), one can see that MnCo2O4 exhibits a higher capacitance value than CoMn2O4. This behavior can be attributed to morphological effects. In fact, as previously demonstrated by morphological studies, the cubic structure of MnCo2O4 likely provides a larger electrochemically active surface area and more accessible interfacial sites for electrolyte penetration. These structural advantages enhance charge accumulation at the electrode–electrolyte interface, resulting in a higher measured Cdl. The “n” parameter, ranging between zero and one, describes the deviation from an ideal capacitor, and ZCPE is the constant phase element expressed in Equation (7).

Table 4.

Total resistance, Rtot, and double-layer capacitance, Cdl, values for MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4.

These results appear to contradict previously reported data. In fact, the literature shows that the diameter of the semicircle in the Nyquist plot, corresponding to the charge-transfer resistance, Rct, is approximately 380 Ω for MnCo2O4 and 290 Ω for CoMn2O4, indicating a significantly lower interfacial resistance for CoMn2O4. Such discrepancies may arise from differences in crystallite size, microstructure, and electrode preparation, all of which strongly influence charge-transfer kinetics [32]. Another recent study reported that MnCo2O4 electrodes exhibit a total resistance of around 15 Ω after cycling [45], which is still much higher than the values obtained in the present measurements.

Moreover, the literature generally indicates that CoMn2O4 exhibits a more vertical low-frequency line, characteristic of diffusion-controlled behavior, compared to MnCo2O4. This has been attributed to the smaller particle size typically observed in Mn-rich compositions, which enhances capacitive effects. Since the present results show the opposite trend, the inverted diffusion behavior observed may originate from differences in morphology, particle connectivity, or electrode packing density relative to those previously reported [60].

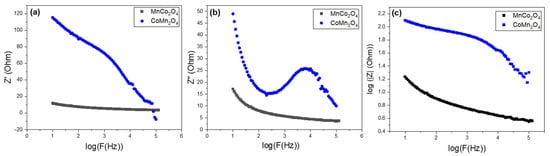

Figure 6 describes the dependence of log|Z| = log(F) with frequency for MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4 spinel oxides. It is observed that CoMn2O4 displays significantly higher ∣Z∣ values than MnCo2O4 in the whole frequency range, indicating that CoMn2O4 has a much greater overall resistance to charge transport. In the low-frequency domain, where ∣Z∣ describes mainly charge-transfer and interfacial processes, CoMn2O4 shows an increase in ∣Z∣, which is consistent with slow interfacial kinetics and a higher Rct. In contrast, MnCo2O4 exhibits a lower impedance, suggesting more efficient charge transfer and superior electrochemical conductivity [61].

Figure 6.

Variation in (a) real part, (b) imaginary part of impedance, and (c) |Z| as a function of frequency for MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4 spinel oxides.

As the frequency increases, the impedance of both materials decreases and tends to stabilize, reflecting the transition from interfacial kinetics to contributions from bulk and solution resistance. However, the ∣Z∣ values of CoMn2O4 remain consistently higher across the full frequency window, confirming that it possesses poorer electrical and ionic transport properties than MnCo2O4. The much lower ∣Z∣ of MnCo2O4 is therefore coherent with its higher electrochemically active surface area, better morphology-induced conductivity, and lower Rct observed in the Nyquist analysis [62,63].

The analysis of Figure 6b shows that the imaginary impedance Z′′ decreases smoothly with frequency for MnCo2O4, indicating fast relaxation and efficient charge transfer. In contrast, CoMn2O4 exhibits much higher Z′’ values and a pronounced relaxation peak, revealing slower interfacial kinetics and stronger diffusion limitations. These results confirm that MnCo2O4 exhibits better electrochemical performance, consistent with its lower total resistance and higher capacitance.

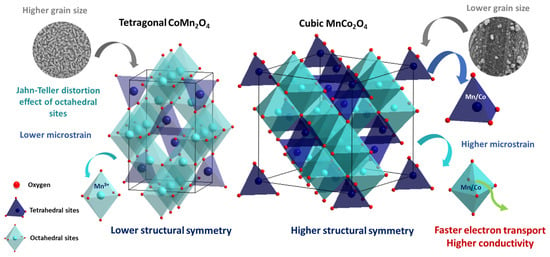

Furthermore, XPS analysis reveals that Mn3+ ions occupy octahedral sites in CoMn2O4, inducing a pronounced Jahn–Teller effect that lowers the structural symmetry and results in an octahedral distortion. This effect reduces electron mobility, leading to higher resistance and lower conductivity. In contrast, the MnCo2O4 spinel retains its highly symmetric cubic structure, despite the presence of Mn ions in both tetrahedral and octahedral sites. This stability is most likely due to the low concentration of Mn ions in the octahedral sites. In addition, this enhanced conductivity is consistent with its granular morphology, smaller crystallite size, and higher microstrain, which collectively promote faster interfacial charge transport across grain boundaries and among active sites. Such efficient charge mobility facilitates redox cycling between metal cations and surface oxygen species, thereby accelerating reaction rates in processes governed by electron- or oxygen-transfer steps, such as oxygen evolution or hydrocarbon oxidation. In contrast, CoMn2O4 shows a larger Rct, reflecting slower charge transfer kinetics, likely due to its needle-like morphology and larger grains, which increase the path length for electron movement. It indicates a more resistive interface, which may limit the rate of surface redox transformations. Figure 7 presents a schematic representation of the main structural and morphological differences between CoMn2O4 and MnCo2O4 and their impact on electron transfer.

Figure 7.

Main structural and morphological variations between CoMn2O4 and MnCo2O4 and their impact on electron transfer.

In the analysis of the diffusion part at low frequencies, one can notice that tetragonal CoMn2O4 exhibits a longer diffusion tail due to its structural anisotropy, which can impede ionic mobility, and its larger particle size, which increases the number of ion diffusion routes. In contrast to the smaller, more conductive, and isotropic cubic MnCo2O4, these physical and structural variables dominate the Warburg behavior observed in EIS, resulting in a more noticeable diffusion resistance despite its lower electronic conductivity. These correlations highlight that electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) parameters can serve as valuable descriptors, reflecting how cation site occupancy modulates charge dynamics at the active interface.

4. Conclusions

MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4 spinels were successfully synthesized on a stainless-steel substrate by hydrothermal processing. Their structural, morphological, vibrational, and electrochemical characteristics were systematically compared. The results showed that cation inversion between Mn and Co has a decisive impact on crystal symmetry, lattice strain, and morphology. MnCo2O4 crystallizes in a cubic phase, producing spherical particles associated with higher microstrain and stronger Mn-O/Co-O bonding. On the other hand, CoMn2O4 stabilizes in a tetragonal phase, producing needle-like crystallites with lower strain and a more flexible bonding environment. These fundamental differences are directly reflected in the electrochemical response: MnCo2O4 shows better charge transfer, whereas CoMn2O4 exhibits higher charge-transfer resistance. This comparative study highlights the roles of cation ordering and crystal symmetry in optimizing the structure, morphology, and electron-transfer behavior of spinel oxides. These findings underscore that understanding cationic distribution in spinel lattices provides a fundamental route towards tailoring the activity, stability, and selectivity of spinels for energy conversion and environmental applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152413267/s1, Table S1. XPS qualitative and quantitative results: binding energies (BE, ±0.2 eV), atomic concentrations (at.%), full width at half maximum (FWHM, ±0.1 eV), and Gaussian-Lorentzian (GL) %; Figure S1. Mn 3s between two very intense cobalt regions in MnCo2O4. CoMn2O4 analysis was published in [31] and is not shown. The relative intensity of Mn 3s in CoMn2O4 is much higher than in MnCo2O4; Figure S2. Normalized (a) Mn 2p3/2 and (b) Co 2p3/2 regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.; methodology, S.A.; validation, D.M.F.S.; investigation, S.A. and A.M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B., A.S. and A.M.F.; writing—review and editing, A.S. and D.M.F.S.; supervision, A.B. and D.M.F.S.; funding acquisition, D.M.F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

D.M.F. Santos would also like to thank Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT, Portugal) for funding a Principal Researcher contract (2023.09426.CEECIND, https://doi.org/10.54499/2023.09426.CEECIND/CP2830/CT0021) in the scope of the Individual Call to Scientific Employment Stimulus—6th Edition.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SS | Stainless steel |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction/X-ray diffractometer |

| ATR-FTIR | Attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transform infrared |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| EIS | Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy |

References

- Ren, Y.; Lei, X.; Wang, H.; Xiao, J.; Qu, Z. Enhanced Catalytic Performance of La-Doped CoMn2O4 Catalysts by Regulating Oxygen Species Activity for VOCs Oxidation. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 8293–8306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Qu, Z.; Qin, Y.; Fu, Q.; Sun, H.; Duan, X. Revealing the Highly Catalytic Performance of Spinel CoMn2O4 for Toluene Oxidation: Involvement and Replenishment of Oxygen Species Using In Situ Designed-TP Techniques. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 6698–6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Gu, Z.; Li, D.; Yuan, J.; Jiang, L.; Xu, H.; Lu, C.; Deng, G.; Li, M.; Xiao, W.; et al. Catalytic combustion of lean methane over MnCo2O4/SiC catalysts: Enhanced activity and sulfur resistance. Fuel 2022, 323, 124399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Liu, S.; Deng, D.; Zhao, H.; Chen, Y. Synthesis of MnCo2O4 nanofibers by electrospinning and calcination: Application for a highly sensitive non-enzymatic glucose sensor. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Nie, Z.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H. Highly sensitive and selective electrochemical sensor based on porous graphitic carbon nitride/CoMn2O4 nanocomposite toward heavy metal ions. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 346, 130539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadivel, S.; Balaji, G.; Rathinavel, S. High performance ethanol and acetone gas sensor based nanocrystalline MnCo2O4 using clad-modified fiber optic gas sensor. Opt. Mater. 2018, 85, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugavadivel, M.; Dhayabaran, V.V.; Subramanian, M. Fabrication of high energy and high power density supercapacitor based on MnCo2O4 nanomaterial. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2019, 133, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-R.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.-F.; Xie, T.; Wu, Y.-C. Integration of urchin-like MnCo2O4@C core–shell nanowire arrays within porous copper current collector for superior performance Li-ion battery anodes. Rare Met. 2024, 43, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Gao, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhuang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Yu, H.; Fu, M. In-situ growth of MnCo2O4 hollow spheres on nickel foam as pseudocapacitive electrodes for supercapacitors. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 587, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Zhou, X.; Yang, Y.; Hu, P.; Ci, L. Ordered porous Mn-Co spinel oxide (CoMn2O4) with vacancies modulation as efficient electrocatalyst for Li-O2 battery. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 670, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Lei, K.; Sun, W.; Li, F.; Cheng, F.; Chen, J. Synthesis of size-controlled CoMn2O4 quantum dots supported on carbon nanotubes for electrocatalytic oxygen reduction/evolution. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 3836–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xiong, S.; Li, X.; Qian, Y. A facile route to synthesize multiporous MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4 spinel quasi-hollow spheres with improved lithium storage properties. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 2045–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, S. Nanostructured mixed transition metal oxide spinels for supercapacitor applications. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 839–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, K.-N.; Hwang, S.M.; Park, M.-S.; Kim, K.J.; Kim, J.-G.; Dou, S.X.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.-W. One-dimensional manganese-cobalt oxide nanofibres as bi-functional cathode catalysts for rechargeable metal-air batteries. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 7665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotalgi, K.; Kanojiya, A.; Tisekar, A.; Salame, P.H. Electronic transport and electrochemical performance of MnCo2O4 synthesized using the microwave-assisted sonochemical method for potential supercapacitor application. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2022, 800, 139660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Xu, L.; Zhai, Y.; Hou, Y. Fabrication of hierarchical porous MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4 microspheres composed of polyhedral nanoparticles as promising anodes for long-life LIBs. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 14298–14306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exarhos, G.J.; Windisch, C.F., Jr.; Ferris, K.F.; Owings, R.R. Cation defects and conductivity in transparent oxides. Appl. Phys. A 2007, 89, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, B.P.; Long, J.W.; Mansour, A.N.; Pettigrew, K.A.; Osofsky, M.S.; Rolison, D.R. Electrochemical Li-ion storage in defect spinel iron oxides: The critical role of cation vacancies. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 1495–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Chen, Z.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, R.; Liu, H.; Tang, P.; Chen, X.; Passerini, S.; Liu, J. The Role of Cation Vacancies in Electrode Materials for Enhanced Electrochemical Energy Storage: Synthesis, Advanced Characterization, and Fundamentals. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 1903780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, P.; Pal, S.; Sreenivas, K.; Kumar, R. Structural and magnetic properties of MnCo2O4 spinel multiferroic. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2015, 21, 2760–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Das, P.; Kuanr, B.K.; Patnaik, S. Multiferroicity in the Presence of Exchange Bias: The Case of Spinel CoMn2O4. Phys. Status Solidi B 2025, e202500233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Gao, T.; Wu, M.; Wei, X.; Yuan, A.; Xu, J. Design and fabrication of flower-shaped MnCo2O4.5/CoSe/MnSe2 heterostructures via incomplete selenization for high-performance cathodes of supercapacitors. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 39, e00802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Noh, G.-H.; Sivagurunathan, A.T.; Kim, D.-H. Atomic surface regulated nanoarchitectured MnCo2S4@ALD-CoOx positrode with rich redox active sites for high-performance supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Liu, J.; Chu, K.; He, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, H.; Peng, Y. Atomic-level cation occupation and magnetic properties of Ce3+-doped ZnFe2O4 spinel ferrite. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 20908–20915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-C.; Lu, Y.-T.; Lee, C.-H.; Gupta, J.K.; Hardwick, L.J.; Hu, C.-C.; Chen, H.-Y.T. The Effect of Degrees of Inversion on the Electronic Structure of Spinel NiCo2O4: A Density Functional Theory Study. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 9692–9699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, R.S.; El-Deen, L.M.S.; Nasr, M.H.; El-Hamalawy, A.A.; Abouhaswa, A.S. Structural, cation distribution, Raman spectroscopy, and magnetic features of Co-doped Cu–Eu nanocrystalline spinel ferrites. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhifallah, I.; Ben Slama, S.; Bardaoui, A.; Chtourou, R. A Combined Experimental and Density Functional Theory Study of Calcination Temperature Effects on the Properties and Photocatalytic Activity of Starch-Mediated Spinel ZnAl2O4. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardaoui, A.; Dhifallah, I.; Daoudi, M.; Aouini, S.; Amlouk, M.; Chtourou, R. Exploring the impact of annealing temperature on morphological, structural, vibrational and electron paramagnetic resonance properties of starch-mediated spinel CoAl2O4: Experimental and DFT study. J. Solid State Chem. 2024, 335, 124732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardaoui, A.; Abdelli, H.; Siai, A.; Ben Assaker, I. Evaluation of Spinel Ferrites MFe2O4 (M = Cu, Ni, Zn, and Co) Photocatalytic Properties in Selective Dehydrogenation of Formic Acid Towards Hydrogen Production. Catal. Lett. 2025, 155, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advani, J.H.; More, G.S.; Srivastava, R. Spinel-based catalysts for the biomass valorisation of platform molecules via oxidative and reductive transformations. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 3574–3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelli, H.; Hamoud, H.I.; Bolletta, J.P.; Paecklar, A.; Bardaoui, A.; Kostov, K.L.; Szaniawska, E.; Maignan, A.; Martin, C.; El-Roz, M. H2 production from formic acid over highly stable and efficient Cu-Fe-O spinel based photocatalysts under flow, visible-light and at room temperature conditions. Appl. Mater. Today 2023, 31, 101771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanad, M.M.S.; Yousef, A.K.; Rashad, M.M.; Naggar, A.H.; El-Sayed, A.Y. Robust and facile strategy for tailoring CoMn2O4 and MnCo2O4 structures as high capacity anodes for Li-ions batteries. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2020, 579, 411889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaddad, M.; Mohamed, R.M.; Mahmoud, M.H.H. Promoting Visible Light Generation of Hydrogen Using a Sol–Gel-Prepared MnCo2O4@g-C3N4 p–n Heterojunction Photocatalyst. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 8717–8725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendale, S.S.; Beknalkar, S.A.; Teli, A.M.; Shin, J.C.; Bhat, T.S. Hydrothermally synthesized aster flowers of MnCo2O4 for development of high-performance asymmetric coin cell supercapacitor. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2023, 932, 117253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Ha, J.; Kim, Y.-T.; Choi, J. Stainless steel: A high potential material for green electrochemical energy storage and conversion. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 440, 135459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouini, S.; Bardaoui, A.; Rego, A.M.B.d.; Ferraria, A.M.; Santos, D.M.F.; Chtourou, R. Synthesis and characterization of CoMn2O4 spinel onto flexible stainless-steel mesh for supercapacitor application. Solid State Sci. 2023, 143, 107283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullity, B.D. Elements of X-Ray Diffraction; Addison-Wesley Publishing: Carrollton, TX, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, G.K.; Hall, W.H. X-ray line broadening from filed aluminium and wolfram. Acta Metall. 1953, 1, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goktas, A.; Modanlı, S.; Tumbul, A.; Kilic, A. Facile synthesis and characterization of ZnO, ZnO:Co, and ZnO/ZnO:Co nano rod-like homojunction thin films: Role of crystallite/grain size and microstrain in photocatalytic performance. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 893, 162334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, M.S.; Ouyang, C.Y. The structural and electronic properties of spinel MnCo2O4 bulk and low-index surfaces: From first principles studies. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 349, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J.; Heo, J.W. Electronic structure and optical properties of inverse-spinel MnCo2O4 thin films. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2012, 60, 1376–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Zhang, W.; Tu, J.; Xia, T.; Chen, S.; Xie, G. Suppressed Jahn–Teller Distortion in MnCo2O4@Ni2P Heterostructures to Promote the Overall Water Splitting. Small 2020, 16, 2001856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, R.S.; Madai, E.; Nair, D.S.; Gonugunta, P.; Armaki, S.M.; Hendrikx, R.; Panneerselvam, T.; Murugan, R.; Kumar, V.V.R.K.; Taheri, P.; et al. Effect of synthesis conditions on morphology, surface chemistry and electrochemical performance of nickel ferrite nanoparticles for lithium-ion battery applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2025, 36, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Durrani, S.K.; Mehmood, M.; Nadeem, M. Hydrothermal synthesis, structural and impedance studies of nanocrystalline zinc chromite spinel oxide material. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2016, 20, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varalakshmi, N.; Narayana, A.L.; Hussain, O.M.; Sreedhar, N.Y. Microstructural analysis and electrochemical performance of MnCo2O4 nanospheres for high efficiency supercapacitors. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2025, 29, 3649–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Tian, L.; Xu, J.; Liu, T.; Liu, D.; Wang, C. MnCo2O4 and CoMn2O4 octahedral nanocrystals synthesized via a one-step co-precipitation process and their catalytic properties in benzyl alcohol oxidation. CrystEngComm 2016, 18, 8887–8897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Yoon, D.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Sharma, A.; Jiang, S.; Muller, D.A.; Abruña, H.D.; et al. Enhanced Oxygen Reduction Performance on {101} CoMn2O4 Spinel Facets. ACS Energy Lett. 2023, 8, 3631–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, M.C.; Payne, B.P.; Grosvenor, A.P.; Lau, L.W.M.; Gerson, A.R.; Smart, R.S.C. Resolving surface chemical states in XPS analysis of first row transition metals, oxides and hydroxides: Cr, Mn, Fe, Co and Ni. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 2717–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilton, E.S.; Post, J.E.; Heaney, P.J.; Ling, F.T.; Kerisit, S.N. XPS determination of Mn oxidation states in Mn (hydr)oxides. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 366, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, M.A.; Graf, A.; Morgan, D.J. XPS Insight Note: Multiplet Splitting in X-Ray Photoelectron Spectra. Surf. Interface Anal. 2025, 57, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitto, S.C.; Langell, M.A. Surface composition and structure of Co3O4(110) and the effect of impurity segregation. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2004, 22, 1690–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, I.G.; Robins, G.A.; Demazeau, G. Multiplet structure of 2p and 3p photoelectron spectra from low-spin and high-spin cobalt (III) compounds. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1981, 14, 3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneesh Kumar, K.S.; Bhowmik, R.N. Micro-structural characterization and magnetic study of Ni1.5Fe1.5O4 ferrite synthesized through coprecipitation route at different pH values. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2014, 146, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.S.; Kuřitka, I.; Vilcakova, J.; Havlica, J.; Masilko, J.; Kalina, L.; Tkacz, J.; Švec, J.; Enev, V.; Hajdúchová, M. Impact of grain size and structural changes on magnetic, dielectric, electrical, impedance and modulus spectroscopic characteristics of CoFe2O4 nanoparticles synthesized by honey mediated sol-gel combustion method. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 8, 045002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, V.; Anupama, A.V.; Kumar, R.V.; Jali, V.M.; Sahoo, B. Correlated vibrations of the tetrahedral and octahedral complexes and splitting of the absorption bands in FTIR spectra of Li-Zn ferrites. Vib. Spectrosc. 2017, 92, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouini, S.; Bardaoui, A.; Ferraria, A.M.; Chtourou, R.; Santos, D.M.F. CuMn2O4 spinel electrodes: Effect of the hydrothermal treatment duration on electrochemical performance. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Eng. 2024, 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puratchimani Mani, V.V.; Suryabai, X.T.; Simon, A.R.; Kattaiyan, T. Cubic like CoMn2O4 nanostructures as advanced high-performance pseudocapacitive electrode: Original scientific paper. J. Electrochem. Sci. Eng. 2022, 12, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.-A.; Heo, Y.-W.; Lee, J.-H. Effect of Zn doping on the structure and electrical conductivity of Mn1.5Co1.5O4 spinel. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 9744–9752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wen, K.; Song, C.; Liu, T.; Dong, Y.; Liu, M.; Deng, C.; Deng, C.; Yang, C. Highly Conductive Mn-Co Spinel Powder Prepared by Cu-Doping Used for Interconnect Protection of SOFC. Coatings 2021, 11, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, K.A.; Wang, C.-C.; Manthiram, A.; Ferreira, P.J. The role of composition in the atomic structure, oxygen loss, and capacity of layered Li-Mn-Ni oxide cathodes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Ahmad, F.; Ibraheem, M.; Shakoor, A.; Ramay, S.M.; Raza, M.R.; Atiq, S. Tuning diffusion coefficient, ionic conductivity, and transference number in rGO/BaCoO3 electrode material for optimized supercapacitor energy storage. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 6308–6323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazanas, A.C.; Prodromidis, M.I. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy—A Tutorial. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2023, 3, 162–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magar, H.S.; Hassan, R.Y.A.; Mulchandani, A. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Principles, Construction, and Biosensing Applications. Sensors 2021, 21, 6578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).