Abstract

This study aimed to (1) analyse home advantage (HA) and home winning percentage (HW), and (2) examine the impact of team level on HA and HW across major European men’s handball leagues from 2021–2022 to 2024–2025. Match data from 6028 games across seven elite leagues—ASOBAL (Spain), Starligue (France), Bundesliga (Germany), Herre Handbold (Denmark), NB I (Hungary), Superliga (Poland), and Andebol I (Portugal)—were analysed, involving 423 team-seasons. Teams were grouped into three competitive levels using hierarchical clustering: high (HLT), medium (MLT), and low (LLT). Differences between leagues were significant for HA, with the Portuguese league showing the lowest values and falling below those of Denmark and Hungary, while the remaining competitions presented comparable results. Team level displayed a clear gradient, with LLT showing the greatest HA and HLT the smallest. Interaction effects were particularly evident for LLT, which recorded reduced HA in Portugal and France compared with Spain, Denmark, and Hungary. For HW, Portugal again recorded the lowest value, and the pattern across team levels was consistent (high > medium > low). Overall, the findings show that the local performance advantage in men’s elite handball is shaped by both competitive level and league-specific contexts, reflecting structural, organisational, and cultural characteristics of each competition.

1. Introduction

Top-level handball is characterised by its dynamism, physical demand, and tactical complexity, where the analysis of collective performance stands as an essential element for the optimisation of the game and the achievement of competitive targets, especially in official competitions where the pressure and importance of each match are maximum [1,2]. Europe’s top leagues combine the best clubs and encourage innovation in collective preparation and strategy [3]. The exhaustive study of handball game dynamics allows us to identify patterns, strengths, and weaknesses, and to design more effective training interventions and game strategies [4].

Among multiple factors that affect sport performance in team sports, the analysis of home performance, commonly referred to as ‘home advantage’ (HA), and the home win (HW) percentage have historically been two of the most widely studied [5,6]. The phenomenon known as home advantage (HA), defined as the higher probability of winning when a team plays at home, has been broadly documented in different sport disciplines, including football [7] and basketball [8,9]. In handball, although this effect has also been observed, the magnitude and consistency of HA vary considerably between countries and seasons [10,11,12]. Home win percentage (HW), defined as the percentage of wins achieved by home teams over total games played, is a useful and easily comprehensible metric that complements HA [13]. In fact, HW is widely used across a variety of team sports, including football [14] basketball [9], rugby [15], and hockey [16], among others. HW has been increasingly utilised to quantify the competitive behaviour of teams and to assess performance inequalities in different contexts. Its straightforward calculation, easy comparability between competitions, and clear relevance to competitive success make HW a valuable metric for understanding home-related performance. As such, incorporating both HA and HW allows for a more comprehensive analysis of home game dynamics in elite sport settings [10]. In handball, although HA has been more commonly analysed [4], HA and HW studies have grown in the last two decades [6,17,18,19], but there are still few studies that systematically compare different professional leagues over a prolonged period.

Several studies have identified multiple factors that explain home advantage, such as crowd influence, knowledge of the environment, logistical conditions, referee bias, and psychological effects derived from the competitive environment [20,21,22,23,24]. However, the magnitude of HA can be modulated by structural variables of the championship (e.g., number of teams), geographical and cultural aspects, or even media pressure. In terms of the number of teams, this can indirectly influence HA by altering the density of the schedule, the number of home matches, and the frequency of travel, factors that can alter the dynamics of fatigue and preparation throughout the season. In the case of media pressure, media coverage can intensify psychological stress, public scrutiny, and bias in refereeing decisions, all of which can indirectly affect HA [5].

Recent studies highlight that crowd support is perceived as a key factor contributing to HA and HW [19], though its actual impact may vary depending on the league’s level of professionalisation—as seen in the German Bundesliga, where crowd influence was found to be limited [18]. Oliveira et al. [22] also observed that HW tends to increase during close matches and decisive phases of play. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic offered a natural experimental context, where the absence of spectators significantly reduced HW in the Polish Superleague according to Krawczyk et al. [21], emphasising the role of environmental and psychological factors. Despite these insights, comparative analyses across national leagues with differing competitive structures and resources remain scarce, highlighting the need for broader, league-level evaluations of HA and HW.

Despite this scientific evidence, to the best of our knowledge there is not a wide range of comparative studies assessing simultaneously HA and HW in top-level European men’s handball leagues, especially over several recent seasons when the public has been reintroduced to sports facilities following the emergence of COVID-19 [25]. Thus, two clearly distinct objectives can be identified: (1) to analyse the home advantage (HA) and home winning percentage (HW) in each of the main European men’s handball leagues over the last four seasons; (2) to examine the impact of team level on HA and HW across these leagues.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

Data were collected from the seven top handball leagues based on EHF criteria which classify national competitions according to their competitive level, professional structure, international performance, and club ranking in European competitions. The data combine (1) sporting performance of clubs in European competitions over last years, (2) coefficient points assigned by the EHF based on continental results, and (3) national league strength, which considers club consistency and competitive depth [26]: Denmark (Bambuni Herreligaen), France (Liqui Moly Starligue), Germany (DAIKIN HBL-Bundesliga), Hungary (Nemzeti Bajnokság I), Poland (Orlen Superliga), Portugal (Andebol I), and Spain (ASOBAL League). These leagues consistently appear among the highest-ranked leagues in Europe, representing the most stable professional environments and the strongest clubs in EHF competitions over the past five years. Their inclusion ensures a homogeneous level of elite performance, comparable organisational standards, and reliable longitudinal data, making them the most suitable group for a cross-national analysis of home advantage in top-level men’s handball.

Data were extracted from an open-access website (www.flashscore.es), widely used for sport results. To collect the data, no permission was required from the entities responsible for the competitions or from the participants, because the data are in the public domain and freely accessible. To ensure reliability, a random sample of matches was cross-checked against official federations records, confirming full consistency.

The data set included 4 regular seasons (from the 2021–2022 season to the 2024–2025 season) excluding matches played in the pre-season, playoffs, and permanence phase. The data set (n = 423) was divided into the different leagues for each season, analysing a total of 6028 matches. Analysing these leagues over the last four seasons (2020/21 to 2024/25) allows us to study the recent behaviour of HA and HW under regular competition conditions, without exceptional alterations.

2.2. Procedures

Variables collected included season, year, and competition, as well as the number of home wins/draws/losses, away wins/draws/losses, total wins/draws/losses, total games played at home, total home points, and total points for each team in each season. These data were entered into custom Microsoft Excel spreadsheets (version 24, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) for further analysis. In these spreadsheets, calculations were performed to determine the HA and the HW for each team in each season. Specifically, HA (%) was calculated as follows: [(total home points/total points) × 100], while HW (%) was calculated as [(total home wins/total home games) × 100] [27].

In addition, the teams in each competition were ranked according to their performance (i.e., team level) in each season, which was determined by the number of points scored over the course of the season relative to the total possible points that could be scored in each season (e.g., a team scoring 32 points out of a possible 60 points would have a winning percentage of 32/60 = 53.34%).

Thus, a hierarchical clustering was carried out according to the squared Euclidean distance [28] to stratify the teams according to their points obtained, providing the following results: (1) High level teams (HLTs) (n = 61; 14.42% of the total data set; points range = 90.41% ± 6.25%, minimum = 77.78%, maximum = 100%); (2) Medium level teams (MLTs) (n = 175; 41.37% of the total data set; points range = 59.58% ± 8.50%, minimum = 46.15%, maximum = 75%); or (3) Low level teams (LLTs) (n = 187; 44.21% of total data set; points range = 32.66% ± 9.48%, minimum = 7.69%, maximum = 45.59%).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Normality was analysed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The homogeneity of the variances was analysed using Levene tests (Table 1). To determine the interaction of HA and HW as a function of league and team level, a 2-factor ANOVA was performed, making a posteriori comparison using the Bonferroni test [29]. Additionally, non-parametric tests such as the Kruskal–Wallis test were used to validate the results obtained. Effect sizes (ES) were also determined for all pairwise comparisons using a partial eta squared (ηp2). Interpretation was based on the following criteria [30]: small = <0.01; moderate = 0.01–0.06; large = >0.06–0.14. For the post hoc analysis, Cohen’s d was calculated and interpreted using Hopkins’ categorization criteria: d > 0.2 as small, d > 0.6 as moderate, d > 1.2 as large, and d > 2.0 as very large [31]. The significance level for all statistical tests was set at p < 0.05. Also, standard deviations and confidence intervals are shown for each of the data provided. Descriptive analyses and inferential tests were performed with the SPSS version 30 statistical software package (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Table 1.

Test of homogeneity of variance based on league and team level.

3. Results

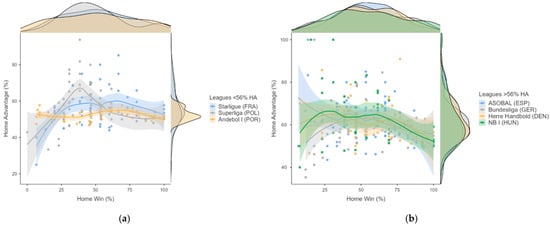

Table 2 shows the descriptive data of HA and HW among the different teams in relation to league and team level. Figure 1 shows the relationship of HA and HW as a function of the league. The relationship between HW and HA is not strictly linear and varies considerably by league. Some leagues show a positive trend (e.g., ASOBAL (ESP), Herre (DEN)), where higher HW aligns with higher HA. Others, such as Andebol I (POR) and Starligue (FRA), show flatter or even U-shaped trends. The top marginal density graph shows that Bundesliga (GER) and Herre (DEN) have a high density around HW = 60–70%, indicating a more consistent home performance. The marginal graph on the right shows that NB I (HUN) and Herre (DEN) have peaks at higher HA values, suggesting a higher home advantage. Andebol I (POR) and Starligue (FRA) show flatter HA distributions, consistent with less pronounced home effects.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for home advantage (HA) and home win (HW) percentage based on league and team level.

Figure 1.

(a) Graph showing HA percentages below 56%. (b) Graph showing HA percentages higher than 56%. Joint plot shows the relationship between home win percentage (HW) on the x-axis and home advantage percentage (HA) on the y-axis, across seven professional men’s handball leagues: ASOBAL (Spain); Andebol I (Portugal); Bundesliga (Germany); Herre Handbold (Denmark); NB I (Hungary); Starligue (France); and Superliga (Poland). Each dot represents a team-season data point, coloured by league. The plot includes the following: (1) Scatter points for each observation; (2) Smoothed trend lines (with confidence intervals) for each league; (3) Marginal density plots (top and right), showing the distribution of HW and HA, respectively, by league.

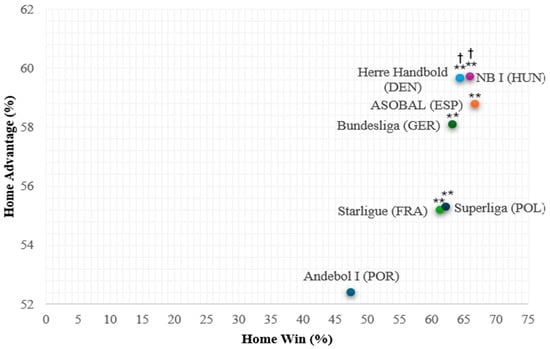

The ANOVA test analysis revealed moderate differences between leagues in both HA (F6,402 = 3.47; p < 0.01; ηp2 = 0.049) and large differences in HW (F6,402 = 11.18; p < 0.001; ηp2 = 0.143). Andebol I (POR) is ranked lowest in the HA and HW values, showing significant differences in HA with respect to Herre Handbold (DEN) (p < 0.05; d = 0.66; dif. 7.26%) and NB I (HUN) (p < 0.05; d = 0.86; dif. 7.32%). In HW, it shows very large differences compared to the rest of the six leagues (p < 0.001; d = 2.66; in all conditions with differences between 13.79% and 19.28%). Herre Handbold (DEN) and NB I (HUN) show higher HA values, while ASOBAL (ESP) is the league with the highest HW (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Scatter plot between HA and HW for each of the leagues. ‘†’ shows significant differences in HA (p < 0.05). ‘**’ shows significant differences in HW (p < 0.001). Significant differences are represented according to Andebol I (POR).

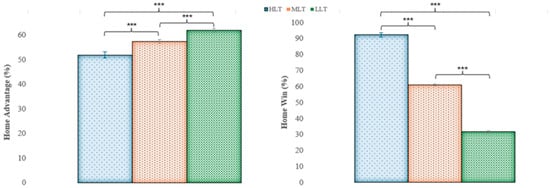

Figure 3 shows the comparison of HA and HW according to team level. The ANOVA results showed significant large differences for both HA (F2,402 = 23.50; p < 0.001; ηp2 = 0.105) and HW (F2,402 = 541.15; p < 0.001; ηp2 = 0.729). Post hoc multiple comparisons revealed significantly greater large differences in HA in LLTs compared to MLTs (+5.41%; p < 0.001; d = 1.36) and very large in HLTs (+10.78%; p < 0.001; d = 2.43). Also, MLTs showed larger differences in HA than HLTs (+5.37%; p < 0.001; d = 1.23). In relation to HW, HLTs exhibited very large differences compared to MLTs (+31.30%) and moderate differences compared to LLTs (+60.59%) (p < 0.001; d = 2.66 and d = 2.97, respectively). Also, MLTs showed very large differences in HW compared to LLTs at 29.30% (p < 0.001; d = 2.43).

Figure 3.

Home advantage (HA) and home win percentage (HW) according to team level (high level team (HLT); medium level team (MLT); and low level team (LLT)). Notes: Description of significance values; ‘***’ = p < 0.001.

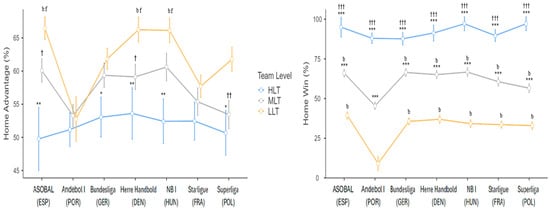

With regard to the interaction between league and team level (Figure 4), there was a significant moderate effect on HA (F12,402 = 1.03; p < 0.05; ηp2 = 0.030) and HW (F12,402 = 2.21; p < 0.05; ηp2 = 0.062). In HA, the performance obtained with the LLT was large and significantly lower in the Andebol I (POR) than in the ASOBAL (ESP) (dif. 13.70%; p < 0.01; d = 1.89), Herre Handbodl (DEN) (dif. 13.48%; p < 0.05; d = 1.54), and NB I (HUN) (dif. 13.37%; p < 0.05; d = 1.26). Also, HA balance was large and lower in the Starligue (FRA) than in the ASOBAL (ESP) (dif. 8.75%; p < 0.01; d = 1.57), moderate in Herre Handbodl (DEN) (dif. 8.52%; p < 0.05; d = 0.73), and moderate in NB I (HUN) (dif. 8.41%; p < 0.05; d = 0.68), with no differences found in HLTs and MLTs (p < 0.05, both). HW performance was very large and lower in the Andebol I (POR) MLT compared to the other six leagues (NB I (HUN) = dif. 21.24%; p < 0.001; d = 2.13; Bundesliga (GER) = dif. 21.02%; p < 0.001; d = 2.02; large in ASOBAL (ESP) = dif. 20.55%; p < 0.001; d = 1.98; Herre Handbold (DEN)= dif. 19.65%; p < 0.001; d = 1.77; moderate in Starligue (FRA) = dif. 15.21%; p < 0.001; d = 1.15; Superliga (POL) = dif. 11.11%; p < 0.05; d = 0.96).

Figure 4.

Differences in HA and HW in relation to team level between each league. Symbols differentiate leagues: ASOBAL (ESP); Andebol I (POR); Bundesliga (GER); Herre Handbold (DEN); NB I (HUN); Starligue (FRA); Superliga (POL). Symbols differentiate between team levels: “*” indicates significant differences vs. LLT. “†” indicates significant differences vs. MLT. Significance level is indicated by the number of symbols: one symbol for p < 0.05, two for p < 0.01, and three for p < 0.001.

Furthermore, HW values were very large and lower in the Andebol I (POR) LLT compared to the other six leagues (ASOBAL (ESP) = dif. 30.26%; p < 0.001; d = 2.63; Herre Handbold (DEN) = dif. 27.82%; p < 0.001; d = 2.56; Bundesliga (GER) = dif. 26.53%; p < 0.001; d = 2.44; NB I (HUN) = dif. 25.09%; p < 0.001; d = 2.30; Starligue (FRA) = dif. 24.45%; p < 0.001; d = 2.22; Superliga (POL) = dif. 23.87%; p < 0.001; d = 2.16).

Furthermore, in HA comparing the internal team level of each league, the LLTs of ASOBAL (ESP) (dif. 16.70%; p < 0.01; d = 1.56), Bundesliga (GER) (dif. 8.80%; p < 0.05; d = 0.92), Herre Handbol (DEN) (dif. 12.63%; p < 0.01; d = 1.33), NB I (HUN) (dif. 13.71%; p < 0.01; d = 1.49), and Superliga (POL) (dif. 11.10%; p < 0.05; d = 1.22) had significantly large higher values than the HLTs. Also, ASOBAL (ESP) LLTs (dif. 6.38%; p < 0.05; d = 0.74), Herre Handbol (DEN) (dif. 7.11%; p < 0.05; d = 0.81) and Superliga (POL) (dif. 8.33%; p < 0.01; d = 1.12), had significantly moderate higher values than MLTs. In Andebol I (POR) and Starligue (FRA), there were no significant differences between their team levels (p > 0.05). In the variable HW, HLTs obtained significantly very large higher values than MLTs and LLTs (p < 0.001; d = 2.77; in all conditions and leagues). Also, MLTs obtained significantly very large higher values than LLTs (p < 0.001; d = 2.31; in all leagues).

4. Discussion

The most relevant findings were as follows: first, Andebol I (POR) recorded the lowest HA and HW values compared to the other leagues; second, LLTs showed higher HA values, while HLTs obtained the highest HW values; third, there were differences in HA in the LLTs of Andebol I (POR) and Starligue (FRA), and In the case of HW, there were differences between all leagues with respect to HLTs; and fourth, HA levels (ASOBAL (ESP), Bundesliga (GER), Herre (DEN), NBI (HUN), Superliga (POL)) were higher in LLTs than in HLTs. In HW, there were differences between all leagues at all three team levels, with HLTs winning more matches than MLTs and LLTs.

4.1. General Differences in Home Advantage (HA) and Home Win (HW) Between Leagues

These results, and the lack of significant differences between the other leagues, highlight possible contextual differences between countries. Previous research in team sports such as football and basketball have shown geographical variations in the HA, attributable to country-specific contextual and organisational factors where the differences between European leagues are evident, with higher data for LLTs in HA and HLTs in HW [7,13,32]. Other research in European handball also reports regional variations, with leagues with higher investment and attendance (e.g., Bundesliga (GER)) showing more pronounced HA than those with less commercial tradition [11,33]. The difference in HA could be influenced by the lower impact of the public or locality in Portugal, due to structural factors such as smaller average hall size, lower average attendance, short distances between locations, and a very tight competitive balance [34,35]. In Denmark, handball has a long-standing tradition, strong institutional support, and a consolidated fan culture, although attendance levels vary considerably across clubs. In Hungary, despite the historical success of several elite teams, spectator interest is generally moderate, as documented in national reports, and recent investment in facilities has been uneven, depending heavily on public funding rather than commercial revenue streams. This structural model—characterised by state-supported clubs and a competitive hierarchy dominated by two teams for decades—shapes both the sporting environment and the expression of home advantage.

By contrast, in Portugal, handball has grown substantially over the last two decades, but many top clubs operate as multi-sport sections of football institutions (e.g., FC Porto, Sporting CP, SL Benfica), where the handball-specific fan base is comparatively smaller. The heterogeneity across these countries in financial structures, infrastructural development, and club organisation may influence the magnitude of HA, not through generalised crowd factors but through the broader ecosystem in which teams compete [19,36,37,38].

For HW, the results showed that Andebol I (POR) also had the lowest HW, with significant differences compared to all other leagues. This result reinforces the HA data, confirming that Portuguese teams have fewer home wins. This could be explained by factors related to overall league competitiveness and league parity [39]. More balanced leagues tend to show less pronounced HW effects due to less quality disparity between home and away teams [40]. In the case of Andebol I (POR), it is important to consider the lower average budget of Portuguese clubs, but which is equal among teams, factors that directly influence the homogeneity of the league. The best teams in Portugal (Porto, Sporting, Benfica) have much higher budgets, as is the case in Spain with Barcelona. Excluding these big teams, there may be greater budgetary balance among the other teams. In contrast, leagues such as the German or French leagues have clubs with greater financial capacity and a large disparity between them [41].

4.2. LLTs Score More Points at Home, but HLTs Win More Matches at Home Overall Without Neglecting Away Performance

This trend has been reported in research on handball and other sports, where teams with greater resources, deeper squads, and international experience tend to maximise home field advantage without neglecting away performance [10,42]. These data suggest that more successful teams are better able to capitalise on the factors associated with HA and HW. Possible causes include greater environmental pressure in favour [43], refereeing influence (more favourable to dominant teams playing at home), superior tactical ability, as well as better hostile management of more experienced players [44]. In addition, HLTs tend to have a larger squad, which allows them to maintain consistent performance both at home and away [45,46]. In addition, the greater professionalisation and logistical resources of HLTs can reduce the negative impact of travel [47] and optimise tactical preparation at home [48]. On the other hand, LLTs may be more vulnerable to structural disadvantages because performance at critical moments of the match is more favourable for HLTs, possibly because of their ability to manage pressure and take advantage of crowd support in decisive situations [12]. In many of these teams, the quality of travel is quite poor, for example, for many of the ASOBAL (ESP) teams, and, curiously, this is the league with the highest percentage of HW. Thus, it can be clearly stated that teams are affected by travel. Lower-budget and fewer professional teams are forced to maximise familiarity and crowd support to compensate for tactical and physical inferiorities [49]. These patterns reinforce the idea that HA and HW do not operate uniformly but are modulated by the internal characteristics of teams.

4.3. Interaction Between League and Team Level

These data indicate that the protective effect of playing at home is more diluted in leagues such as the Portuguese and French leagues. In the Portuguese case, this could be related to more centralised structures, shorter distances, and smaller crowds [41]. In France, although the level of the Starligue is high, the difference between the top and bottom teams might be smaller, creating a more balanced environment where HA has less effect [50]. In more competitive leagues, LLTs might benefit from more professionalised infrastructures and environments, which could explain the higher HA values in these leagues [51].

The significant differences in HA and HW values between sport levels in Andebol I (POR) compared to the other leagues reinforce the idea that the organisational and cultural context of each league modulates the impact of team level. Leagues such as the Bundesliga (GER), ASOBAL (ESP), or NB I (HUN) operate within more professionalised structures, where even medium and low level teams typically benefit from greater resource stability, more developed youth systems, and stronger institutional organisation. These conditions provide MLTs and LLTs with a more supportive competitive environment that facilitates higher HW percentages. In contrast, the structural characteristics of Andebol I—marked by lower budgets outside the top clubs, reduced commercial capacity, and less stable professional frameworks—limit the ability of MLTs and LLTs to capitalise on contextual advantages. These findings reinforce the importance of cultural and organisational dimensions such as the economic model, fan culture, media relevance, facility quality, and institutional stability, all of which shape how different competitive levels convert the home environment into performance outcomes [52,53,54].

4.4. Internal League Differences According to Team Level

This reinforces the idea that home amplifies the performance of the most competitive teams. The Bundesliga (GER), considered the strongest league today [55], showed a clear pattern of higher HA in dominant teams. These results may be linked to economic power, environmental pressure in high-capacity halls, and the intimidating effect on opponents and referees. In contrast, in leagues such as Starligue (FRA) and Andebol I (POR), no such differences were observed, which might suggest greater competitive homogeneity [23,56,57]. Despite representing two successful but distinct models of elite European handball, a more nuanced interpretation is required that takes into account the specific characteristics of each league. In the French case, the Starligue is one of the most professional and competitive leagues in Europe, with teams that have high budgets, first-class infrastructure, and an average attendance of over 2000–3000 spectators for the top teams. This extreme professionalisation, combined with the highly competitive balance documented in previous studies, could explain the lesser influence of HA: the homogenisation of resources, the international experience of the squads, and the efficient management of travel neutralise the contextual differences between playing at home and playing away [50,58]. For its part, Portugal has experienced extraordinary growth in recent years, with clubs such as FC Porto, Sporting CP, and Benfica establishing themselves as European benchmarks. In recent seasons, these teams have always occupied the top positions, far ahead of the rest. It should also be noted that for the last two seasons, the Portuguese league has only had 12 teams (previously 14), which may explain the results. Apart from the ‘big three’, there seems to be a fair amount of parity among the other Portuguese teams. In this context of increasing competitiveness, the absence of HA in Andebol I could be explained by a more pronounced internal competitive balance, where technical and tactical quality prevails over environmental factors, similar to the phenomenon observed in other leagues that have achieved a high degree of professionalisation (Federação de Andebol de Portugal, 2025 [59]; Ferrari et al., 2022 [60]). In both cases, although for different reasons, the structural development of the leagues seems to have minimised the influence of the local environment on performance.

In summary, these results confirm that home advantage and home win percentage are multifactorial phenomena, modulated both by contextual variables (culture, league structure, crowd size) and by the team levels, in line with the previous literature on team sports [5].

This study has several limitations that must be taken into account when interpreting the results. Firstly, it has not been possible to accurately control for the influence of the structural elements of sports facilities, such as the number of stands (one, two, three, or four) and the total capacity of the arenas. Secondly, the distance travelled by the visiting team was not included as an analytical variable. Furthermore, the relationship between the population of the team’s home city and HA was not specifically addressed. Future lines of research should incorporate contextual variables such as the architecture of the arenas, actual attendance per game, the distance and travel time of visiting teams, and the size of the local population, thus allowing for a more multifactorial and accurate analysis of HA and HW.

In terms of practical applications, the results of this study suggest that clubs and federations should consider the influence of structural and contextual factors when interpreting home performance. Optimising the spectator experience, encouraging attendance, and improving travel logistics could help maximise HA. For coaches and analysts, understanding how these elements interact can aid tactical preparation and strategic decision-making, especially in key matches or against direct rivals. Finally, fairness in the organisation of competitions, ensuring comparable conditions between teams in terms of facilities and travel, can contribute to a more competitive and fairer environment in European professional handball.

5. Conclusions

The results indicate that HA and HW differ across the major European men’s handball leagues, with Portugal consistently presenting the lowest values. Competitive team level strongly influences both variables, as HLTs show greater success at home compared with medium and low level teams. Differences between leagues are especially pronounced among LLTs, suggesting that organisational structure, competitive balance, local culture, and fan engagement shape the ability of less competitive teams to benefit from playing at home.

These findings highlight that the magnitude and expression of HA depend on the specific characteristics of each competition. Consequently, league context should be considered when evaluating team performance and when designing tactical, organisational, and logistical strategies. This evidence may support clubs and federations in refining their competitive planning and in developing league models that promote balanced and context-aware decision-making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.N., C.G.-S. and A.d.l.R.; methodology, M.M.N.; software, G.F.G.; validation, G.F.G., C.G.-S. and A.d.l.R.; formal analysis, R.N.-A.; investigation, M.M.N., R.N.-A., R.C.P. and G.F.G.; resources, G.F.G. and R.C.P.; data curation, M.M.N. and G.F.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.N.; writing—review and editing, C.G.-S. and A.d.l.R.; visualisation, M.M.N.; supervision, R.N.-A., C.G.-S. and A.d.l.R.; project administration, M.M.N., C.G.-S. and A.d.l.R.; funding acquisition, R.C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras for their support through the payment of the Article Processing Charge (APC). This contribution enhances the international visibility of our research and reinforces our shared commitment to advancing scientific knowledge and academic collaboration across Latin America.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ferrari, W.R.; Sarmento, H.; Vaz, V. Match Analysis in Handball: A Systematic Review. Montenegrin J. Sports Sci. Med. 2019, 8, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.G.; Merlin, M.; Pinto, A.; Torres, R.d.S.; Cunha, S.A. Performance-Level Indicators of Male Elite Handball Teams. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport. 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovey, O.M.; Mitova, O.O.; Solovey, D.O.; Boguslavskyi, V.V.; Ivchenko, O.M. Analysis and Generalization of Competitive Activity Results of Handball Clubs in the Game Development Aspect. Pedagog. Phys. Cult. Sports 2020, 24, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, J.; Gómez, M.-Á.; Sampaio, J. From a Static to a Dynamic Perspective in Handball Match Analysis: A Systematic Review. Open Sports Sci. J. 2015, 8, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ruano, M.Á.; Pollard, R.; Lago-Peñas, C. Home Advantage in Sport: Causes and the Effect on Performance, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bilalić, M.; Gula, B.; Vaci, N. Revising Home Advantage in Sport—Home Advantage Mediation (HAM) Model. Int. Rev. Sport. Exerc. Psychol. 2024, 18, 1096–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, R.; Gómez, M.A. Comparison of Home Advantage in Men’s and Women’s Football Leagues in Europe. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2014, 14, S77–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.R.; Roebber, P.J. NBA Team Home Advantage: Identifying Key Factors Using an Artificial Neural Network. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Pérez-Chao, E.; Nieto-Acevedo, R.; Scanlan, A.T.; Lopez-García, A.; Lorenzo, A.; Gómez, M.Á. Is There No Place like Home? Home-Court Advantage and Home Win Percentage Vary According to Team Sex and Ability in Spanish Basketball. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport. 2024, 24, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquina Nieto, M.; García-Sánchez, C.; Nieto-Acevedo, R.; de la Rubia, A. Exploring the Home Advantage and Home Winning Effect in Handball: Differences between Sexes and Team Level. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2025, 20, 1617–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago-Peñas, C.; Gómez, M.A.; Viaño, J.; González-García, I.; De Los Ángeles Fernández-Villarino, M. Home Advantage in Elite Handball: The Impact of the Quality of Opposition on Team Performance. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport. 2013, 13, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pic, M. Performance and Home Advantage in Handball. J. Hum. Kinet. 2018, 63, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Pérez-Chao, E.; Martín-Castellanos, A.; Nieto-Acevedo, R.; Lopez-García, A.; Portes, R.; Gómez, M.Á. Examining the Role of Fan Support on Home Advantage and Home Win Percentage in Professional Women’s Basketball. Percept. Mot. Skills 2024, 131, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.Á.; Pollard, R. Calculating the Home Advantage in Soccer Leagues. J. Hum. Kinet. 2014, 40, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.; Reeves, C.; Bell, A. Home Advantage in the Six Nations Rugby Union Tournament. Percept. Mot. Skills 2008, 106, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leard, B.; Doyle, J.M. The Effect of Home Advantage, Momentum, and Fighting on Winning in the National Hockey League. J. Sports Econom. 2011, 12, 538–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodenas, J.; Ferrandis, J.; Moreno-Pérez, V.; Campo, R.L.; Resta, R.; Coso, J. Effect of the Phase of the Season and Contextual Variables on Match Running Performance in Spanish LaLiga Football Teams. Biol. Sport. 2024, 41, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volossovitch, A.; Debanne, T. Home Advantage in Handball. In Home Advantage in Sport: Causes and the Effect on Performance; Gómez-Ruano, M.A., Pollard, R., Lago-Peñas, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 220–227. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew, G.A.; Carron, A. V Crowd Effects and the Home Advantage. Int. J. Sport. Psychol. 1994, 25, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Neave, N.; Wolfson, S. Testosterone, Territoriality, and the ‘Home Advantage’. Physiol. Behav. 2003, 78, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, P.; Smoliński, M.; Labiński, J.; Szczerba, M. Home Advantage in Matches of the Top Polish Men’s Handball League in the Seasons before, during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Biomed. Hum. Kinet. 2024, 16, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Gómez, M.; Sampaio, J. Effects of Game Location, Period, and Quality of Opposition in Elite Handball Performances. Percept. Mot. Skills 2012, 114, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauß, B.; Bierschwale, J. Spectators and the Home Advantage in the German National Handball League. Z. Sportpsychol. 2008, 15, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershgoren, L.; Levental, O.; Basevitch, I. Home Advantage Perceptions in Elite Handball: A Comparison Among Fans, Athletes, Coaches, and Officials. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 782129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.B.; Blackwell, J.; Dolan, P.; Fahlén, J.; Hoekman, R.; Lenneis, V.; McNarry, G.; Smith, M.; Wilcock, L. Sport in the Face of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Towards an Agenda for Research in the Sociology of Sport. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 2020, 17, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Handball Federation (EHF). Place Distribution Men’s EHF Club Competitions 2025–26. 2025. Available online: https://www.eurohandball.com/media/rnoldqze/place-distribution-mens-ehf-club-competitions-2025_26.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Pollard, R.; Gómez, M.-Á. Validity of the Established Method of Quantifying Home Advantage in Soccer. J. Hum. Kinet. 2015, 45, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquina Nieto, M.; García-Sánchez, C.; Lorenzo Calvo, J.; López Serrano, C.; de la Rubia, A. Comparative Analysis of Clustering Methods in the Evaluation of Home Advantage in Handball: Implications for Sport Performance. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2025, 17479541251384496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-84787-906-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Science, 2nd ed.; Routledge. Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 0-8058-0283-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, W.G. A Scale of Magnitude for Effect Statistics. In A New View of Statistics; Hopkins, W.G., Ed.; Sportsci: Melbourne, Australia, 2002; p. 502. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, R.; Gómez, M.A. Components of Home Advantage in 157 National Soccer Leagues Worldwide. Int. J. Sport. Exerc. Psychol. 2014, 12, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, H.E.; Schreyer, D.; Jetzke, M. German Handball TV Demand: Did It Pay for the Handball-Bundesliga to Move from Free to Pay TV? Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2020, 20, 618–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debanne, T. Effects of Game Location, Quality of Opposition and Players’ Suspensions on Performance in Elite Male Handball. [Efecto Según El Lugar Del Partido, La Calidad Del Adversario y de Las Exclusiones de Los Jugadores Sobre Las Prestaciones Del Balonmano Masculino de Alto Nivel]. RICYDE Rev. Int. Cienc. Deporte 2018, 14, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, R.; Amaro, N.; Pollard, R. How Best to Quantify Home Advantage in Team Sports: An Investigation Involving Male Handball Leagues in Portugal and Spain. RICYDE Rev. Int. Cienc. Deporte 2015, 11, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garamvölgyi, B.; Dóczi, T. Sport as a Tool for Public Diplomacy in Hungary. Phys. Cult. Sport Stud. Res. 2021, 90, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossing, N.N.; Nielsen, A.B.; Elbe, A.-M.; Karbing, D.S. The Role of Community in the Development of Elite Handball and Football Players in Denmark. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2016, 16, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storm, R.K.; Nielsen, C.G.; Jakobsen, T.G. The Complex Challenge of Spectator Demand: Attendance Drivers in the Danish Men’s Handball League. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2018, 18, 652–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, C.E. The Competitiveness of Games in Professional Sports Leagues. J. Sports Anal. 2017, 3, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, D.; Beaumont, J.; Goddard, J.; Simmons, R. Home Advantage and the Debate about Competitive Balance in Professional Sports Leagues. J. Sports Sci. 2005, 23, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, Ó.; Ruiz, J.L. Data Envelopment Analysis and Cross-Efficiency Evaluation in the Management of Sports Teams: The Assessment of Game Performance of Players in the Spanish Handball League. J. Sport Manag. 2013, 27, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Pérez-Chao, E.; Portes, R.; Ribas, C.; Lorenzo, A.; Leicht, A.S.; Gómez, M.Á. Impact of Spectators, League and Team Ability on Home Advantage in Professional European Basketball. Percept. Mot. Skills 2024, 131, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrell, A.J.; Dietz, B. Fan Support of Sport Teams: The Effect of a Common Group Identity. J. Sport. Exerc. Psychol. 1992, 14, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sors, F.; Grassi, M.; Agostini, T.; Murgia, M. The Influence of Spectators on Home Advantage and Referee Bias in National Teams Matches: Insights from UEFA Nations League. Int. J. Sport. Exerc. Psychol. 2023, 21, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhards, J.; Mutz, M. Who Wins the Championship? Market Value and Team Composition as Predictors of Success in the Top European Football Leagues. Eur. Soc. 2017, 19, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Bassek, M.; Garnica-Caparros, M.; Memmert, D. “Chop and Change”: Examining the Occurrence of Squad Rotation and Its Effect on Team Performance in Top European Football Leagues. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2024, 19, 2467–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, R.; Ortega-Becerra, M.; Tremps, V.; Vicente, A.; Merayo, A.; Mallol, M. Analysis of Sleep Quality and Quantity during a Half-Season in World-Class Handball Players. Biol. Sport 2025, 42, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pott, C.; Spiekermann, C.; Breuer, C.; ten Hompel, M. Managing Logistics in Sport: A Comprehensive Systematic Literature Review. Manag. Rev. Q. 2024, 74, 2341–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inan, T. The Effect of Crowd Support on Home-Field Advantage: Evidence from European Football. Ann. Appl. Sport. Sci. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardeau-Moreau, D. Quand La Logique Bénévole Cède La Place à La Logique Salariale: L’exemple Du Handball Professionnel Français. Loisir Société/Soc. Leis. 2007, 30, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trandel, G.A.; Maxcy, J.G. Adjusting Winning-Percentage Standard Deviations and a Measure of Competitive Balance for Home Advantage. J. Quant. Anal. Sports 2011, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Musa, V.; De Senzi Barreira, C.P.; Gonçalves Madeira, M.; Pereira Morato, M.; Pombo Menezes, R. La Autoorganización Del Balonmano Masculino y Femenino a Alto Nivel. E-Balonmano Com J. Sports Sci. 2023, 18, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, M. Hämmern, Verwandeln Und Entschärfen. Zur Valenz Metaphorischer Verben Des Erzielens Und Verhinderns von Toren Im Handball, Eishockey Und Fußball. Acta Fac. Philos. Univ. Ostrav. Stud. Ger. 2024, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, I.A.; Magyar, M.; Gősi, Z. A Hivatásos Sportszervezeti Rendszer Kialakulása a Magyar Kézilabdában. Gradus 2022, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Handball Federation (EHF). EHF Club Competitions 2024/25. Available online: https://www.eurohandball.com/media/qoznbzmk/eabs-manual-club-competitions-2024_25.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Gómez, M.Á.; Lago-Peñas, C.; Viaño, J.; González-Garcia, I. Effects of Game Location, Team Quality and Final Outcome on Game-Related Statistics in Professional Handball Close Games. Kinesiology 2014, 46, 249–257. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, R.; Prieto, J.; Gómez, M.-Á. Global Differences in Home Advantage by Country, Sport and Sex. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2017, 17, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligue Nationale de Handball (LNH). Budgets des Clubs Français Pour la Saison 24/25. Available online: https://docs.lnh.fr/dp/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Federação de Andebol de Portugal EHF. Champions League: Campanha Histórica do Sporting CP Chega Ao Fim. Available online: https://portal.fpa.pt/2025/04/ehf-champions-league-campanha-historica-do-sporting-cp-chega-ao-fim/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Ferrari, W.; Sarmento, H.; Marques, A.; Dias, G.; Sousa, T.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; Gama, J.; Vaz, V. Influence of Tactical and Situational Variables on Offensive Sequences During Elite European Handball Matches. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 861263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).