This section combines the experimental results for all mix designs under pre-fire and post-fire conditions. We examine how partial replacement of Portland cement with GGBFS, biochar, and hydrochar influences mechanical performance, thermal degradation, and mass stability. The presentation follows the methodological order and connects qualitative fracture evidence (crack patterns) with quantitative metrics (strength retention). To enhance understanding, the results are discussed with reference to known hydration mechanisms (e.g., clinker dissolution, latent hydraulic/pozzolanic reactions) and porosity development, while keeping reference to the figures and tables produced in this study. When relevant, we highlight expected sensitivities to curing and temperature history, variability in specimens, and microstructural factors such as the interfacial transition zone (ITZ). Overall, the analysis combines visual observations with measured strengths to offer a clear account of how each additive influences the load-bearing structure before and after thermal exposure.

7.1. Pre-Fire Compressive Strength Testing

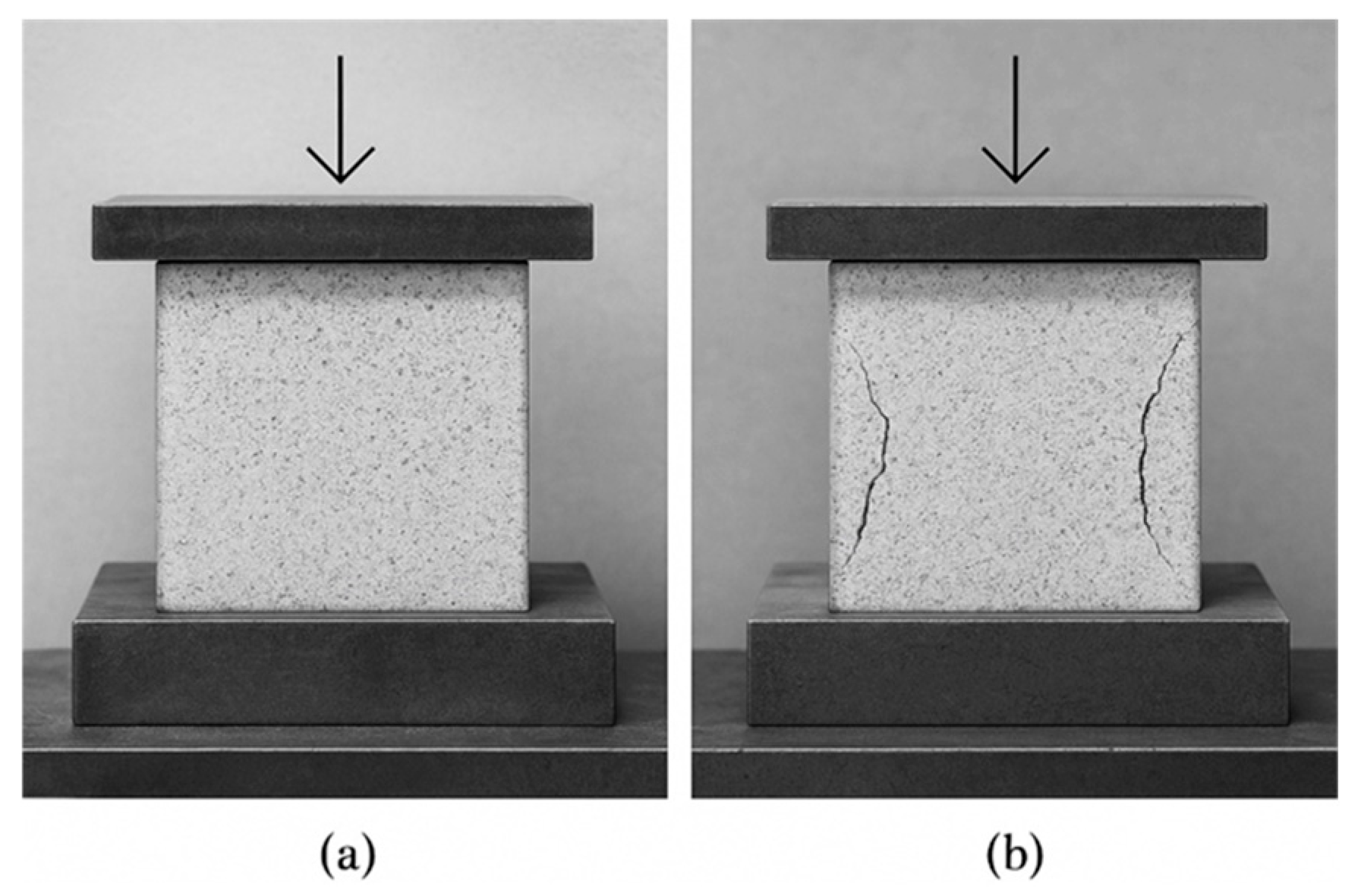

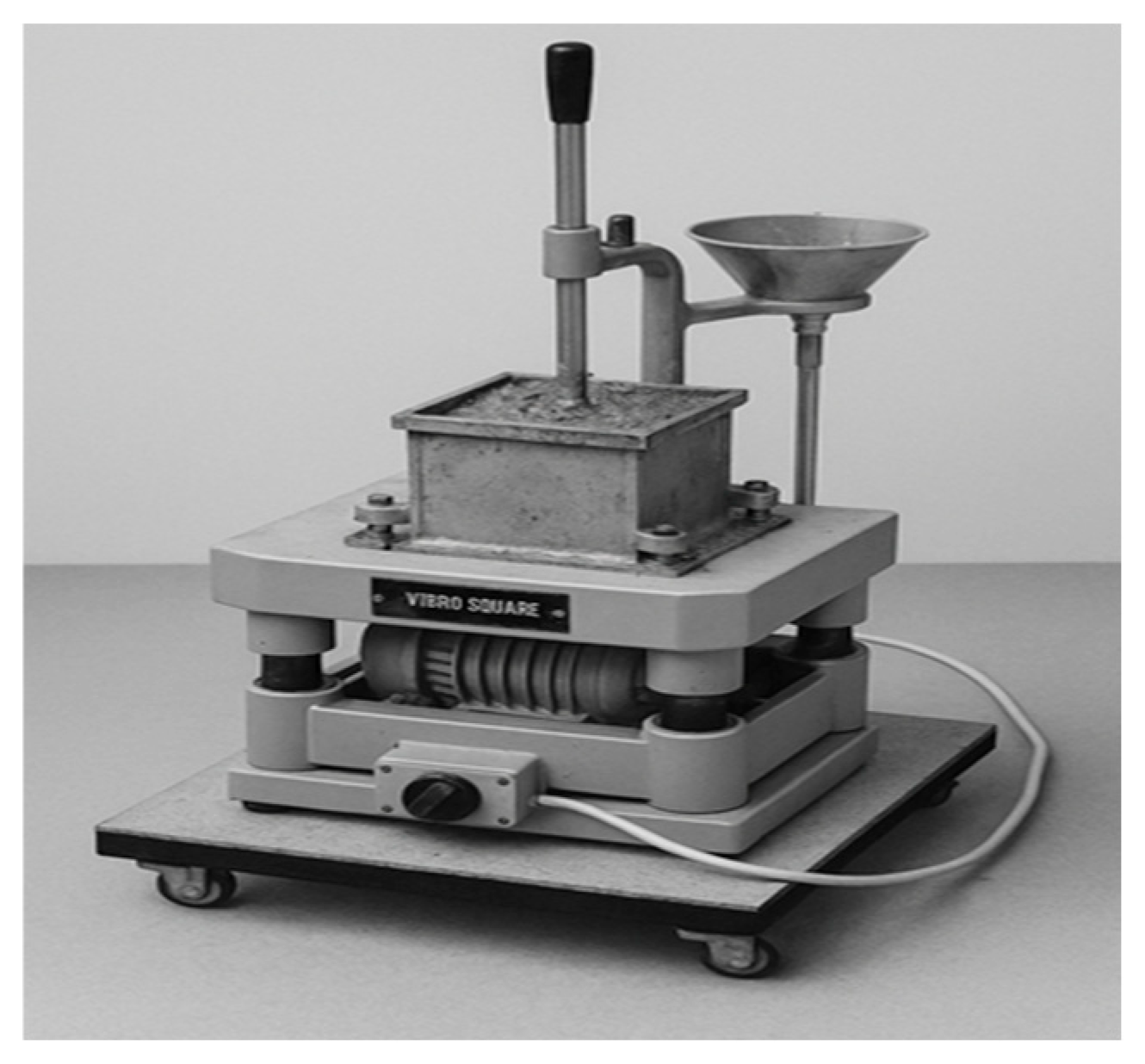

Pre-fire compressive strength was measured according to EN 12390-3 [

37].

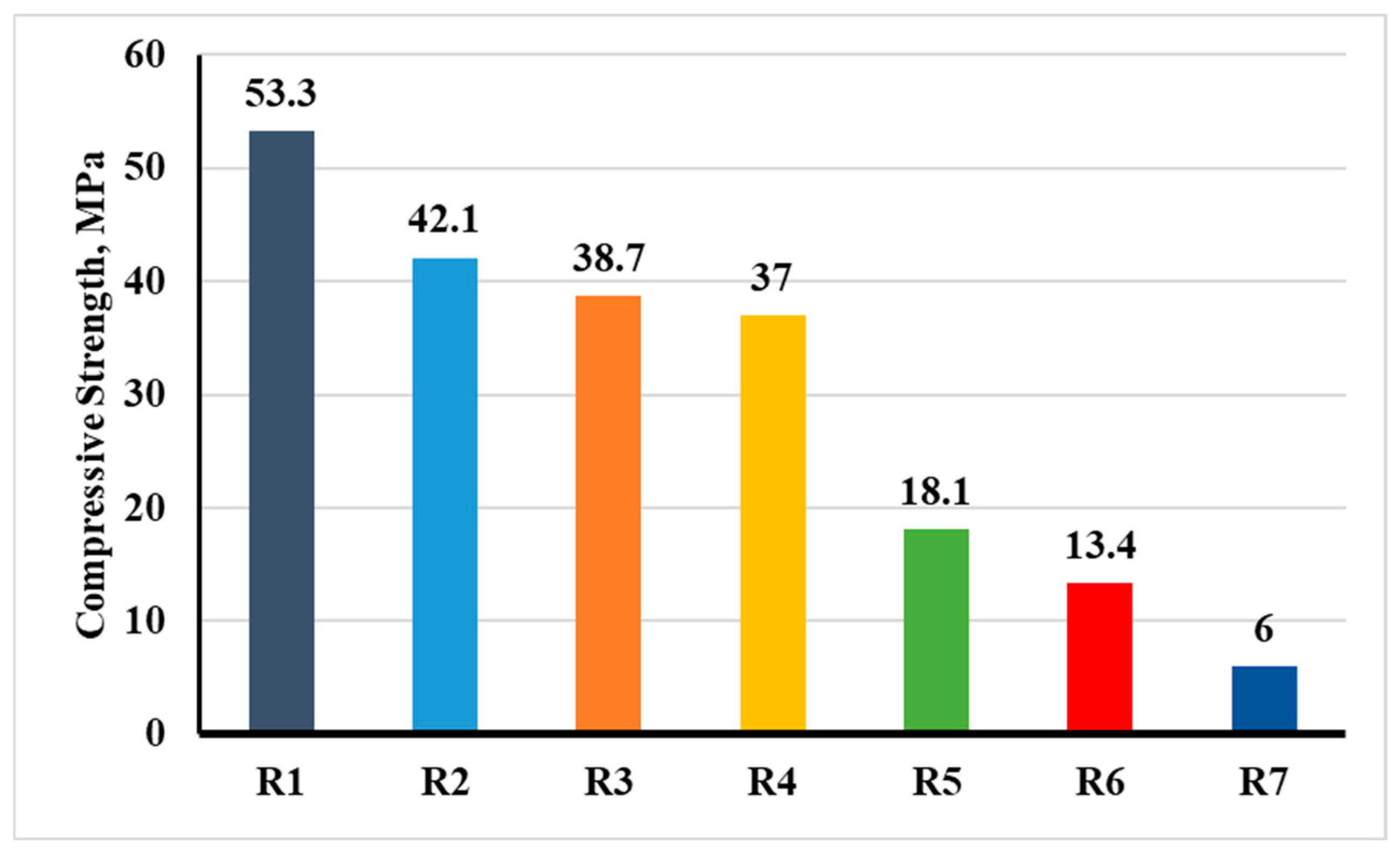

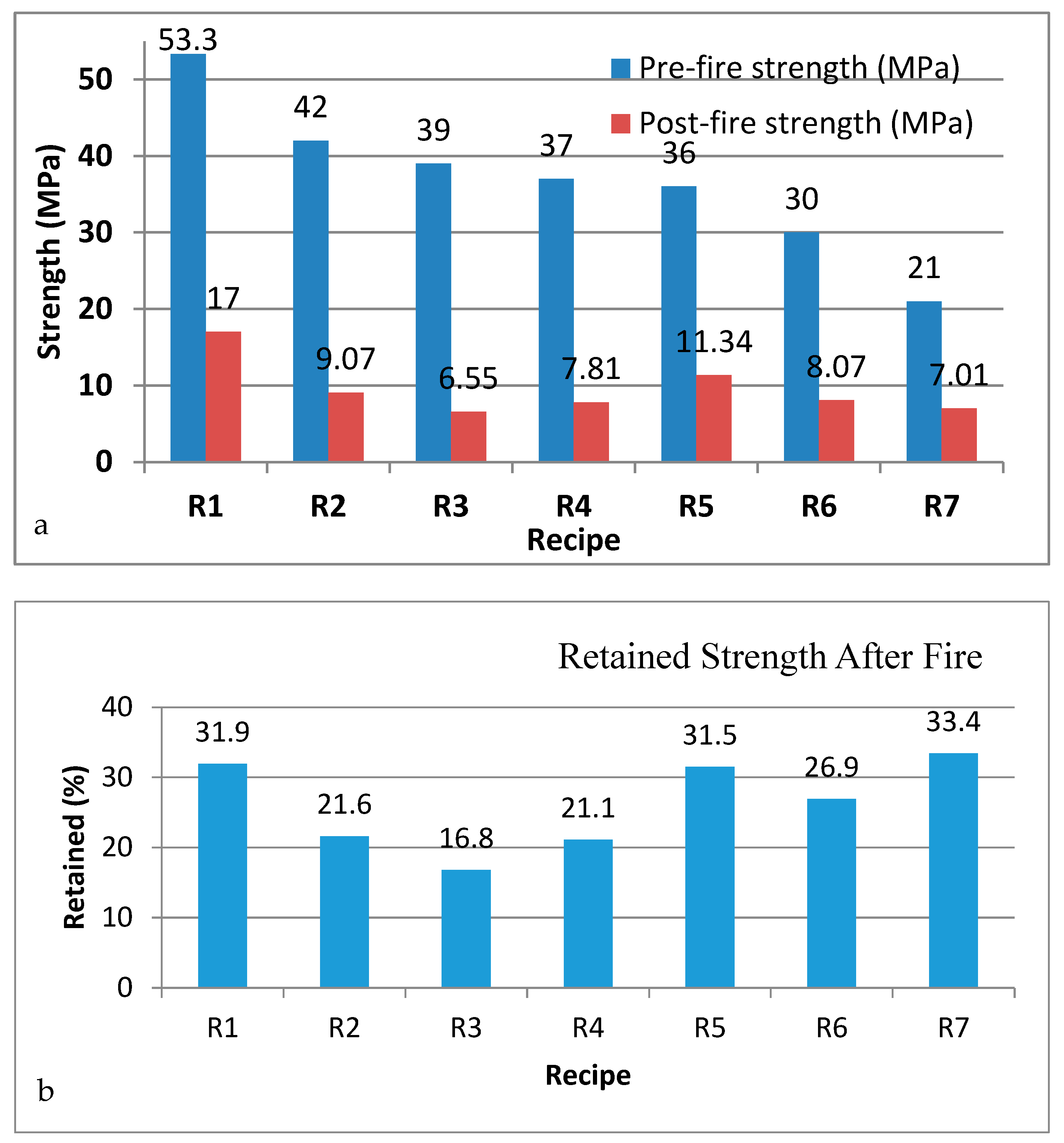

Figure 12 and

Table 4, compares the seven mixes at the test age. As expected, the control R1 (cement–aggregate–water only) achieved the highest strength (53.3 MPa), consistent with Portland-cement systems where a low water/cement ratio promotes a dense hydrate network, limited capillary porosity, and thus high load-bearing capacity. R1’s performance sets a benchmark for evaluating the effects of cement substitution. In contrast, the hydrochar series showed a steady decline with increased replacement. R5 (5%), R6 (10%), and R7 (20%) registered progressively lower strengths, with R7 showing the lowest among all mixes. This trend aligns with reduced hydraulic bonding when a mostly non-hydraulic, carbon-rich filler displaces clinker: at the tested dosages, hydrochar does not provide enough pozzolanic reactivity to produce additional C–S–H, and its high specific surface area can increase water demand, worsen internal porosity, and disrupt particle packing. Any potential micro-filler benefits seem to be outweighed by the decrease in reactive cement and the resulting weakening of the percolated hydrate network. The decline also matches expectations that the nucleation/seed effects of carbonaceous particles are limited at these replacement levels and curing conditions. The GGBFS-blended R2 (50% replacement) showed about 21% lower strength than R1, reflecting the slower early hydration kinetics of slag. This behavior is typical at 28 days for mixes with significant slag content and depends on the curing regime and temperature [

73]. In such systems, the latent hydraulic reactions of GGBFS need adequate alkalinity and time to significantly contribute to C–S–H formation. Before these conditions are achieved, early-age stiffness and strength may remain suppressed compared to pure Portland cement. The addition of PP fibers in R4 (with 50% GGBFS) did not offset this early-age shortfall, and its measured strength also lagged behind the control. This finding aligns with the understanding that micro-fibers mainly influence crack control and ductility rather than increasing intrinsic compressive strength at low strains. Similarly, R3 (10% biochar) underperformed compared to R1, consistent with the expected early-age response of composite binders containing high-surface-area carbonaceous fillers that modify water distribution and pore structure without delivering comparable pozzolanic benefits within the tested timeframe. Collectively, these observations indicate that, at the examined replacement levels and curing schedule, strength development is governed by (i) the balance between reactive clinker and latent hydraulic/pozzolanic constituents, (ii) the evolution of porosity (capillary and interfacial), and (iii) the extent to which additives act as inert diluents versus reactive binders. The ranking across R1 > R2/R4/R3 > R5 > R6 > R7 mirrors this balance and provides a baseline for interpreting strength retention after thermal loading.

Surface Cracking from Pre-Fire Compression

Surface cracking patterns (

Figure 13a–g) provide qualitative insight into stress redistribution and matrix–aggregate interaction before thermal exposure and, by extension, into how each binder system accommodates inelasticity and microcrack growth:

- −

R1 (Figure 13a): Fine, uniformly distributed hairline cracks, characteristic of a dense matrix near the elastic–inelastic transition, where microcracking initiates but remains well constrained by a strong paste skeleton. The pattern suggests efficient stress diffusion and a relatively robust ITZ.

- −

R2 (Figure 13b): Slightly wider cracking and a detached corner fragment. Early-age slag systems can exhibit altered ITZ chemistry and lower early bond strength, leading to localized stress intensification and more pronounced edge damage under peak load, consistent with observations for slag-blended concretes [

15].

- −

R3 (Figure 13c): Fewer, more diffuse cracks, indicating elevated internal porosity and a softer matrix. While reduced stress concentration may delay coalescence, the concomitant loss of stiffness limits peak strength, matching the measured reduction relative to R1.

- −

R4 (Figure 13d): No visible surface cracking at the specimen faces. PP fibres likely bridged microcracks during loading, restricting surface expression of fracture and promoting a more distributed damage field—behaviour widely reported for fibre-reinforced concretes under compression [

34].

- −

R5 (Figure 13e): No visible cracking at 5% hydrochar, consistent with a matrix still dominated by cement hydration products and with microcracks either below the surface or too fine to resolve visually at the employed documentation scale.

- −

R6 (Figure 13f): Localized detachment of two fragments, indicative of weak interfacial bonding and early microcrack coalescence into shallow surface spalls. This suggests stress concentration at heterogeneities introduced by the additive and a more fragile ITZ.

- −

R7 (Figure 13g): Minimal visible surface cracking despite low strength, suggesting a more ductile, porosity-mediated deformation pathway in which energy is dissipated through distributed microcracking and matrix compaction rather than through large, well-defined macrocracks at the surface.

Taken together, the crack morphologies corroborate the strength hierarchy by revealing how each mix partitions damage between the paste, ITZ, and aggregate. Mixes with greater early-age stiffness and stronger ITZ (e.g., R1) exhibit tight, evenly distributed microcracks, whereas systems with slower hydration or higher porosity (e.g., R2, R6, R7) show either localized spalling or subdued surface cracking consistent with diffuse internal damage. The fibre-modified slag blend (R4) illustrates the role of PP fibres in suppressing visible cracking without necessarily enhancing peak compressive strength. This distinction becomes important when assessing post-fire residual performance.

7.2. Heating Testing

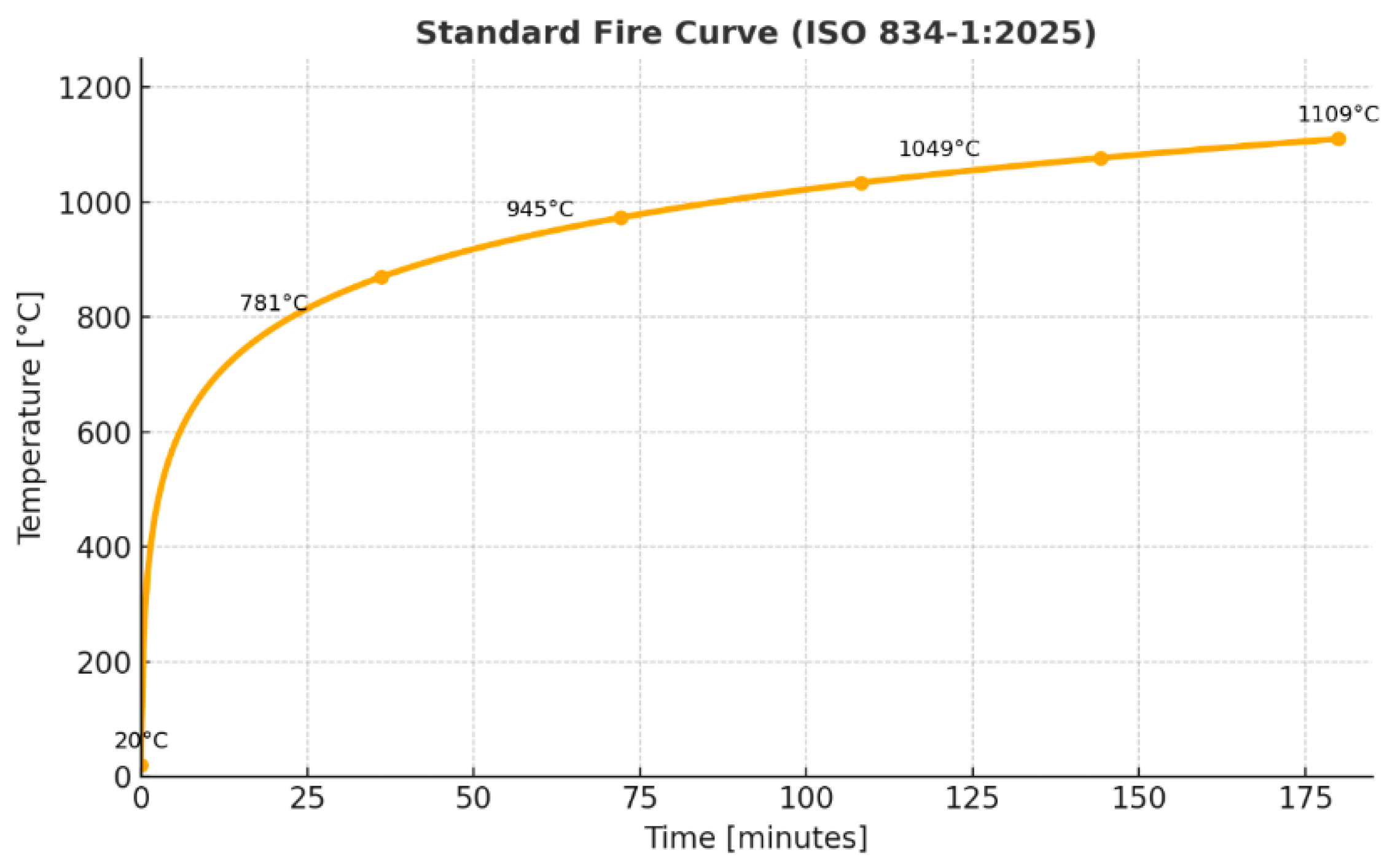

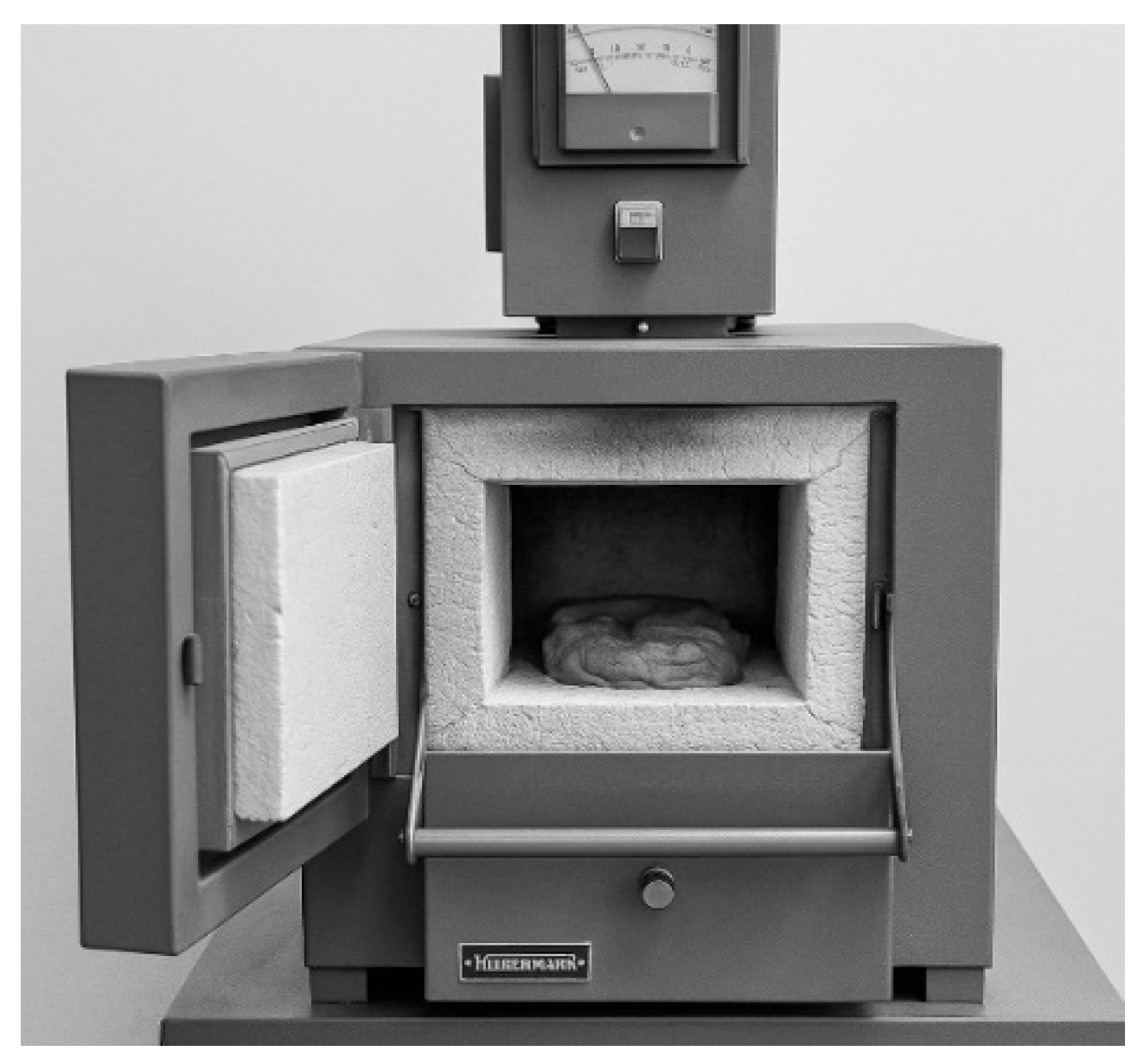

Fire resistance was evaluated using a furnace protocol conforming to the ISO 834-time temperature curve [

70], which reproduces the steep thermal ramp, ensuing thermal shock, and sustained high-temperature plateau characteristic of compartment fires. Specimens were heated to a peak of ≈950 °C to represent fully developed conditions. Both phenomenological responses (spalling, explosive splitting, surface cracking, and visible thermal expansion) and quantitative outcomes (mass loss and qualitative post-fire integrity) were recorded. Mass loss was computed as:

where

and

Denote pre- and post-exposure masses, respectively. Observations for each mixture are provided in

Figure 14a–g, and a consolidated summary is given in

Figure 14 and

Table 5. The cross-recipe trend in mass loss is synthesized in

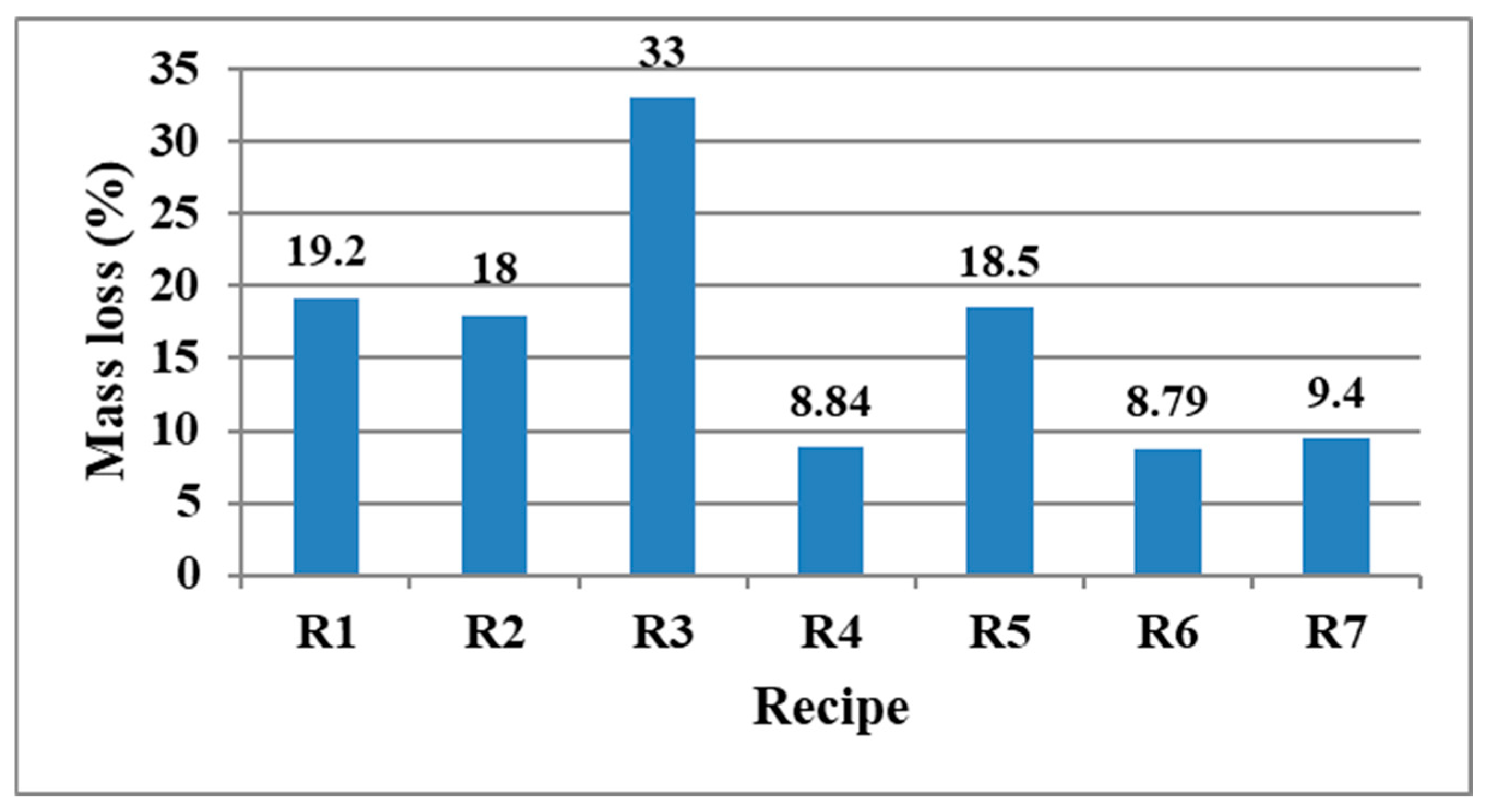

Figure 15 (line diagram) and discussed below.

Recipe 1 (R1) (100% Cement), underwent explosive spalling upon heating. One face remained largely intact while the others fragmented, with blocky pieces breaking from the edges and corners. This pattern, along with a mass loss of 19.2% (see

Table 5), indicates a failure caused by trapped steam vapor pressure and stress concentration at the aggregate-paste interface. The dense, low-permeability matrix of this plain Portland cement concrete, which lacked fibers or pores to provide pressure relief, explains its severe spalling compared to modified mixes.

Recipe 2 (50% Cement, 50% Slag), (R2) experienced extensive surface spalling, especially on corners, with an 18.0% mass loss. Despite GGBFS improving long-term durability, it created a tight matrix at this testing age that trapped steam pressure, leading to failure similar to R1. High temperatures also weakened the slag-modified hydrates, making the matrix brittle. The refined porosity from slag was insufficient for pressure release during rapid heating, offering no spalling benefit.

Recipe 3 (90% Cement, 10% Biochar), (R3) showed the most severe damage, with catastrophic corner loss and deep erosion, resulting in the highest mass loss of 33.0%. This extreme spalling is due to biochar’s highly porous and water-absorbent nature. Upon heating, the trapped moisture rapidly turns to steam, creating intense internal pressure, especially at corners. Biochar’s low thermal conductivity and hydrophilic properties worsened the pressure build-up, leading to explosive failure dominated by pore pressure rather than gradual softening.

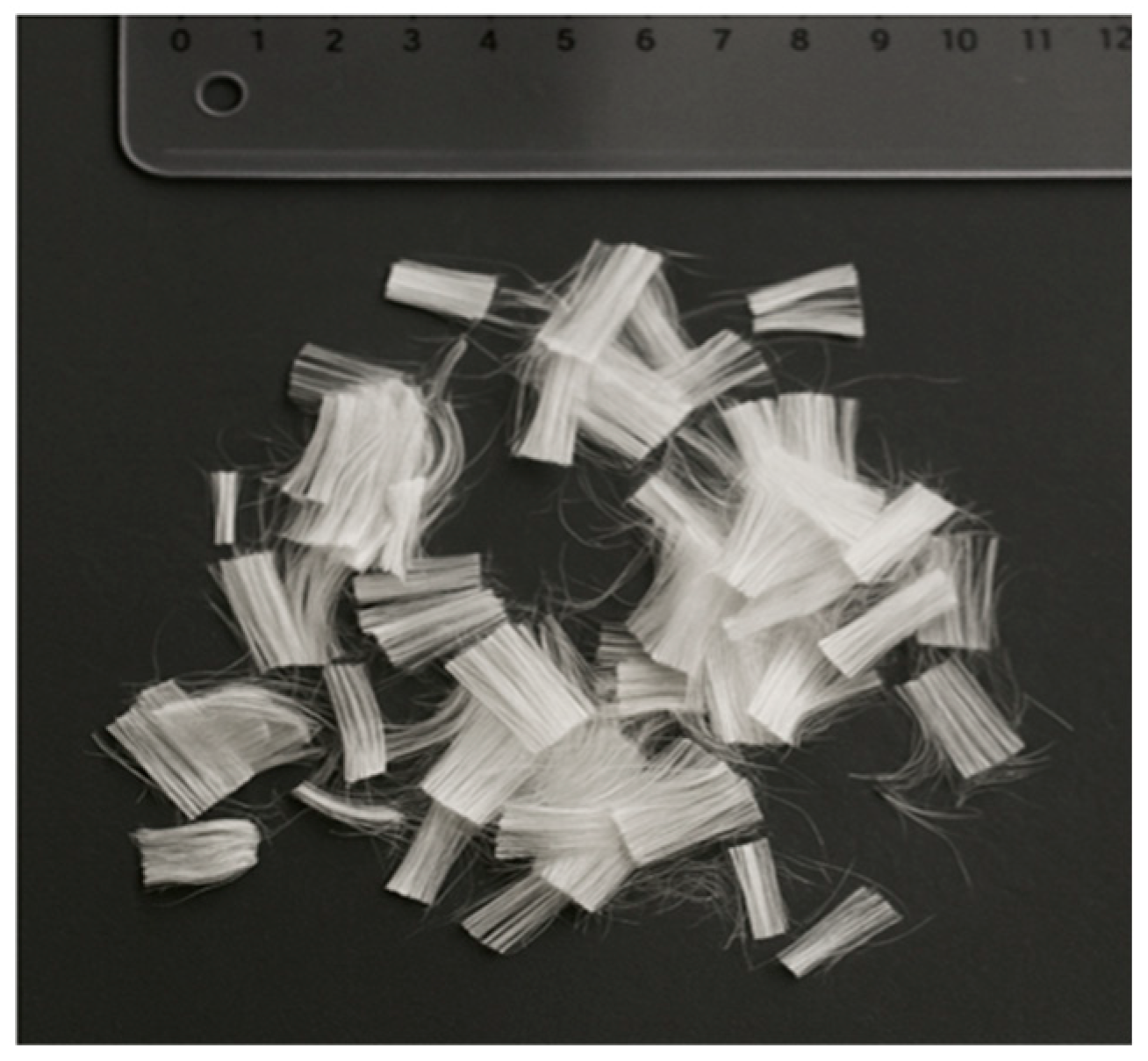

Recipe 4 (50% Slag + PP Fibre), (R4) resisted explosive spalling, developing only a network of thermal cracks while maintaining its overall shape. Its mass loss was low at 8.84%. This performance is due to the polypropylene fibres, which melt and create channels that release internal steam pressure, preventing violent failure. The damage was thus structurally contained, demonstrating the efficacy of fibres in providing pressure relief and significantly improving spalling resistance.

Recipe 5 (95% Cement, 5% Hydrochar), R5 showed significant surface cracking but no explosive spalling, with a mass loss of 18.5%. The 5% hydrochar replacement likely introduced limited permeability and stress-absorbing zones, which helped vent some vapor pressure and prevented violent failure. However, this small dosage was insufficient to fully prevent major cracking. The similar mass loss to plain mixes suggests that low hydrochar content offers only partial mitigation and does not fundamentally alter the material’s response under severe thermal stress.

Recipe 6 (90% Cement, 10% Hydrochar), (R6) exhibited no spalling, with only thermal cracking observed. The specimen expanded and softened during heating, resulting in minimal mass loss of 8.79%. This superior performance is attributed to the higher hydrochar content, which increased microporosity and provided effective vapor escape routes. The balance between permeability for pressure relief and matrix cohesion prevented explosive failure, indicating that the higher hydrochar fraction shifted the material beyond a critical threshold into a damage regime dominated by controlled cracking.

Recipe 7 (80% Cement, 20% Hydrochar), (R7) demonstrated superior fire resistance with no cracking or spalling, only thermal expansion, and a low mass loss of 9.4%. This performance is attributed to the high hydrochar content, which creates interconnected pores for vapor release and disrupts heat conduction, reducing internal pressure buildup. However, this enhanced fire tolerance coincided with the lowest pre-fire compressive strength, highlighting a key trade-off between fire resilience and ambient strength that requires balanced design considerations.

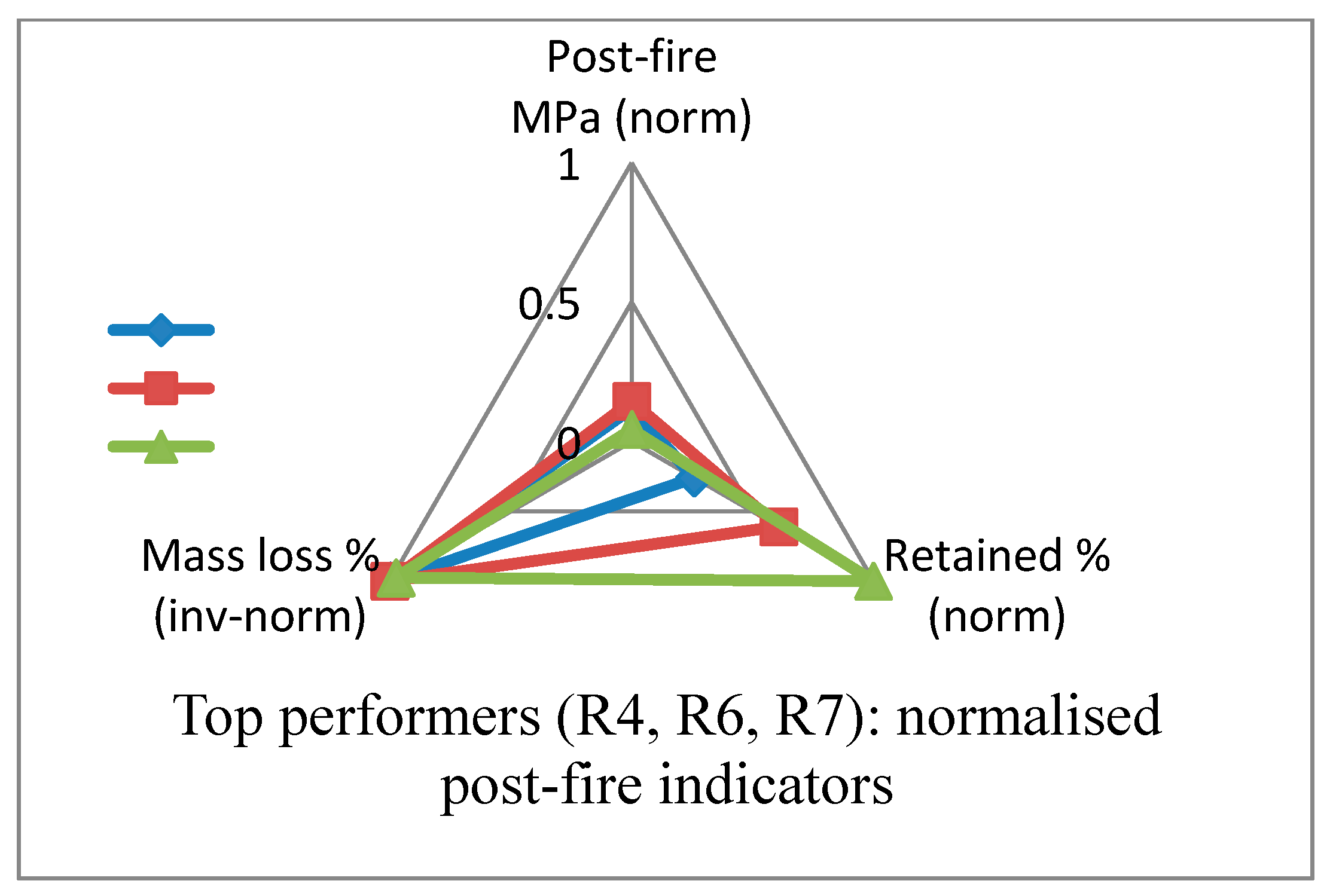

Cross-Recipe Synthesis and Implications, the mixes separate into two distinct groups based on fire performance. R4, R6, and R7 show low mass loss (8.8–9.4%) and non-explosive, crack-dominated failure. In contrast, R1–R3 and R5 exhibit higher mass loss and explosive spalling. The performance ranking (R7 ≈ R6 ≈ R4 ≫ R2 ≈ R5 ≈ R1 ≫ R3) directly correlates with each mix’s capacity for steam venting during rapid heating. The results confirm that fire resistance depends primarily on creating connected pathways for steam release (via fibers or high hydrochar content), not on ambient density, though this often involves a trade-off with pre-fire compressive strength.

7.4. Cracking from Compression Test After Fire

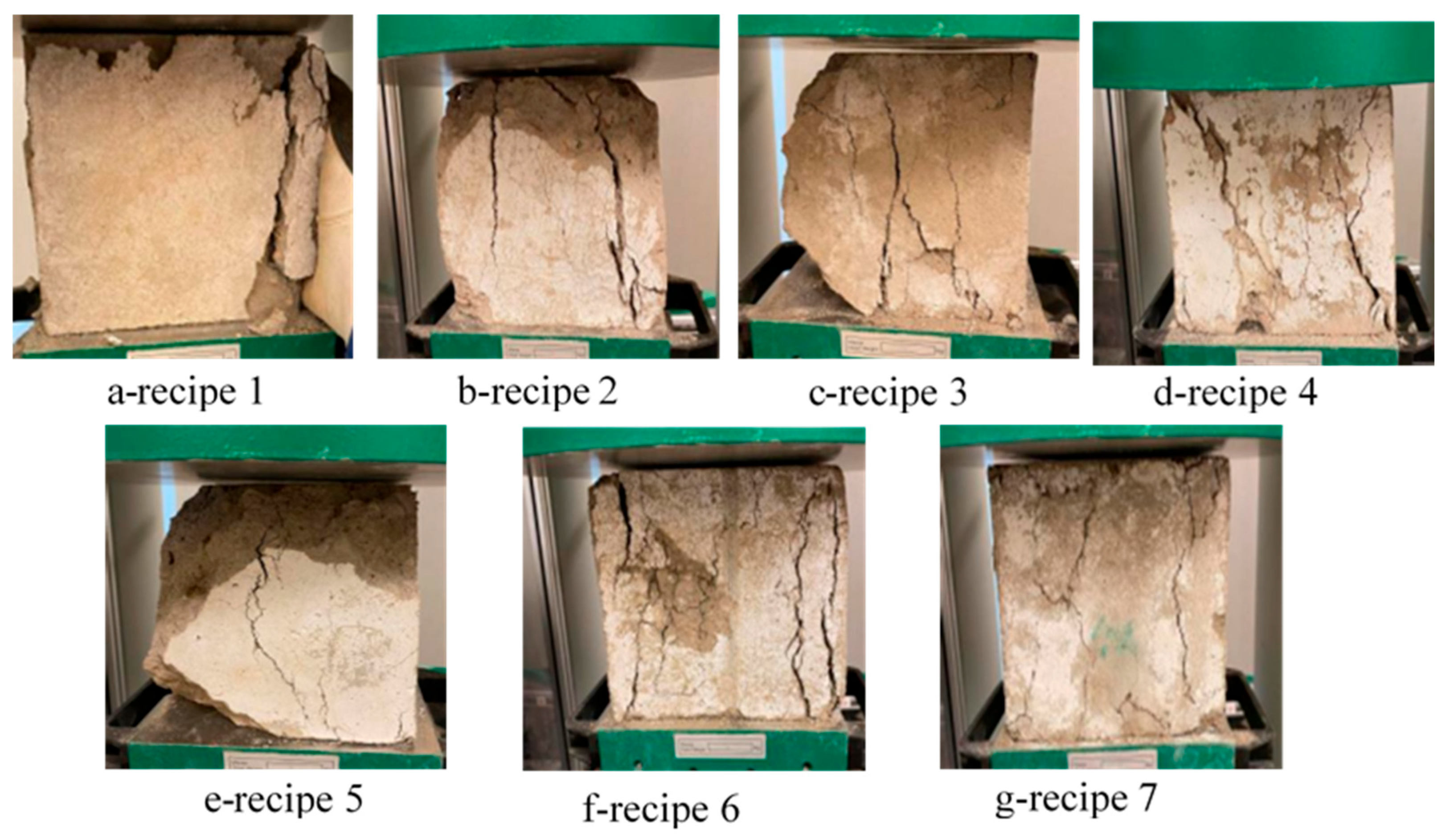

Representative post-fire cracking observed after uniaxial compression is documented in

Figure 17a–g. Following thermal exposure, the specimens predominantly failed by through-thickness splitting accompanied by spalling, with crack apertures sufficiently large to release sizable fragments from the core. In Recipe 1 (

Figure 17a), the dominant feature was a wide, continuous fracture that traversed the section and precipitated the detachment of large pieces; a pronounced vertical crack was also evident along the right face. Recipe 2 (

Figure 17b) exhibited a clear escalation in severity relative to Recipe 1, with deeper and wider fractures, greater crack multiplicity, and more extensive material loss, indicating a more brittle post-fire response under compression. For Recipe 3 (

Figure 17c), deep primary fractures were again present, but these were accompanied by finer, randomly oriented fissures that suggest additional microcrack coalescence beyond that seen in the earlier mixes.

Recipe 4 (

Figure 17d) exhibited a spatially distributed crack network that closely resembled that of Recipe 3, characterized by widely propagated, deep cracks that liberated large fragments from multiple faces. In Recipe 5 (

Figure 17e), deep, wide fractures and associated spalling were still observable; however, the overall extent and dispersion of damage were comparatively lower, making this mix the least susceptible to cracking under the combined effects of fire and subsequent compression in the present series. Recipe 6 (

Figure 17f) marked the upper bound of damage severity, with the highest observed crack density. Fractures were both deep and widely distributed, and large sections disengaged from the body, consistent with extensive loss of load-carrying integrity after heating. Finally, Recipe 7 (

Figure 17g) mirrored the behavior of Recipes 5 and 6: long, well-distributed fractures traversed the specimen, the entire cross-section displayed visible cracking, and sizeable chunks detached. Taken together, the qualitative ranking of crack severity increased from Recipe 1 to a peak at Recipe 6, with Recipe 5 demonstrating relative resistance, and Recipe 7 presenting a widely distributed, cross-section-spanning crack pattern comparable to the more damage-prone mixes.

7.5. In-Depth Analysis of Temperature Effects on Concrete Behavior

The thermochemical and mechanical degradation of concrete under elevated temperatures follows well-established mechanisms that provide critical context for interpreting the experimental results. As temperature rises, key transformations occur that directly explain the performance variations observed across mixes R1–R7.

Thermo-Chemical Degradation Progression:

100–300 °C: Evaporation of free water and initiation of C-S-H gel dehydration begins, leading to initial strength reduction and microcrack formation [

54,

61].

400–600 °C: Decomposition of Portlandite (Ca(OH)

2) occurs around 450 °C, releasing chemically bound water and creating additional porosity. Concurrently, advanced C-S-H degradation causes significant strength loss and increased permeability [

51,

61]. 700–900 °C: Complete decomposition of hydration products and quartz transformation in aggregates (α- to β-quartz at 573 °C) results in substantial mechanical deterioration and color changes observed in our specimens [

54].

Thermo-Mechanical Damage Mechanisms:

The differential thermal expansion between aggregate (typically 6–12 × 10

−6/°C) and cement paste (approximately 18 × 10

−6/°C) generates internal stresses that initiate microcracking, particularly evident in the crack patterns of R1-R3 (

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 17). This thermal incompatibility is exacerbated in dense matrices like R1, where restrained expansion leads to tensile failure at the interfacial transition zone (ITZ).

Pore Pressure Development:

The rapid heating rate of the ISO 834-1 curve (reaching approximately 840 °C in 30 min) creates steep moisture gradients. In low-permeability mixes (R1, R2), vapor migration cannot keep up with steam production, leading to critical pore pressure buildup that exceeds the tensile strength of the matrix—explaining the explosive spalling behavior. This phenomenon is well-documented in literature, where pressures can reach 2–8 MPa under similar conditions [

12,

68].

Additive-Specific Thermal Responses:

The superior performance of R4 (PP fibers) aligns with established pressure relief mechanisms, where fiber melting at approximately 165 °C creates interconnected void networks for vapor escape [

15,

58]. Similarly, hydrochar’s effectiveness in R6–R7 can be attributed to its microporous structure providing pre-existing venting pathways, reducing the vapor pressure peaks that drive explosive spalling. These fundamental temperature-dependent processes provide the mechanistic foundation for understanding the comparative performance ranking (R7 ≈ R6 ≈ R4 ≫ R2 ≈ R5 ≈ R1 ≫ R3) and underscore the importance of engineered permeability in fire-resistant concrete design. The evidence across all recipes confirms three robust tendencies. First, partial clinker substitution—whether with GGBFS, biochar, or hydrochar—reduces baseline compressive strength at the tested age, with the extent depending on the degree of substitution and the reactivity of the additive. Second, fire exposure amplifies these differences by activating transport- and pressure-controlled degradation processes (moisture migration, vapor pressure buildup, and microcrack coalescence), which in turn influence spalling propensity and mass loss. Third, measures that reconfigure the pore network—either through engineered venting (PP fibers) or meso-porosity (higher hydrochar dosages)—reliably suppress explosive fragmentation but do not automatically guarantee better residual capacity; the latter depends on how much of the load-bearing hydrate skeleton survives the thermal cycle. These general patterns reconcile the mass-loss data (

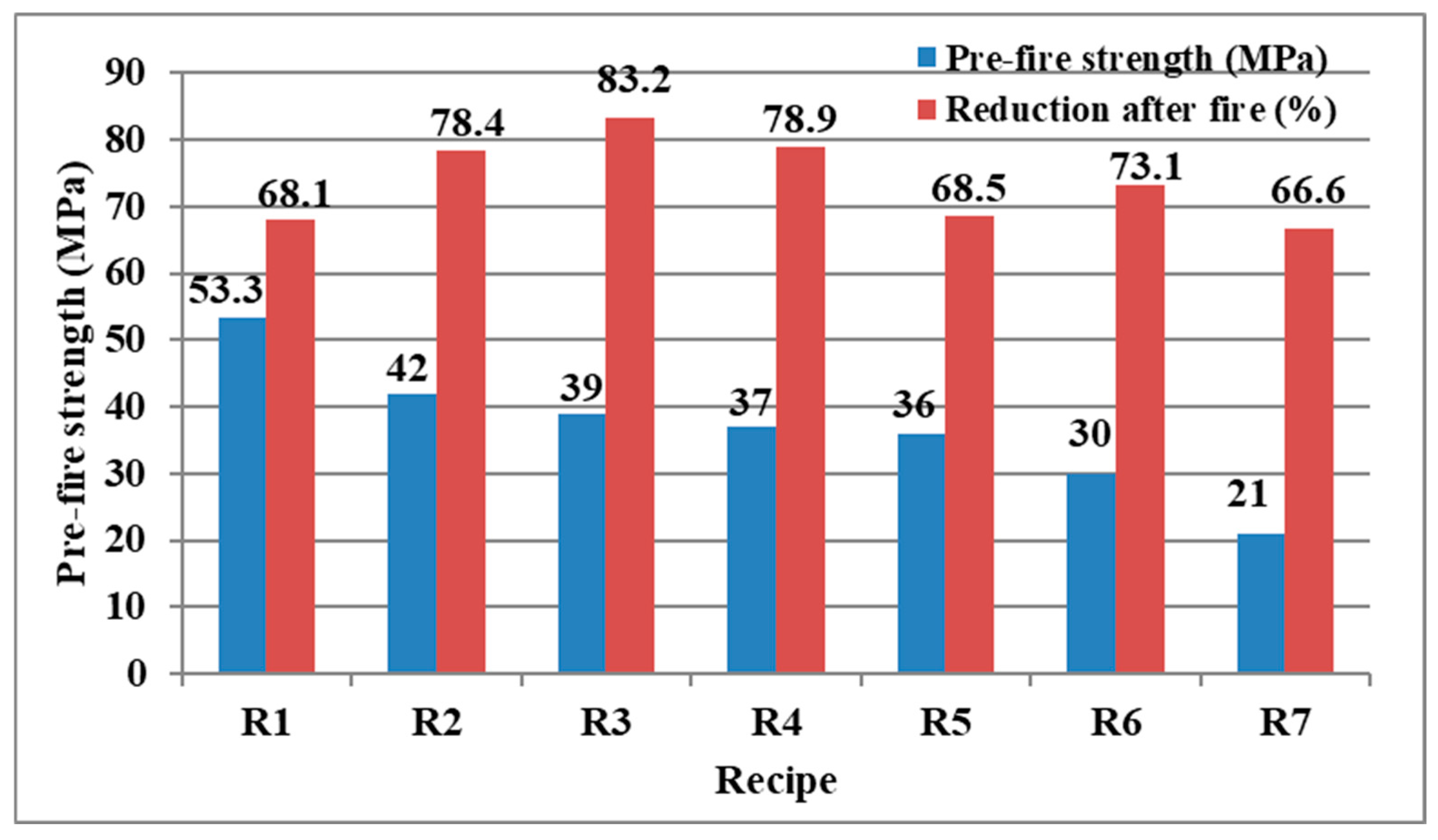

Figure 16), the absolute and normalized strength results (

Figure 16a,b), and the additional cross-checks below. The purpose is to show how retained strength correlates with loss (calculated as 100 minus retained). R3 exhibits the largest reduction (about 83.2%), while R7 has the smallest (about 66.6%), defining the upper and lower bounds of proportional loss. This visualization highlights the trade-off between high initial capacity and vulnerability to thermal damage. Mixes with higher pre-fire MPa (e.g., R1) tend to experience larger proportional losses, whereas hydrochar-rich mixes (R6–R7) have lower initial capacity but smaller proportional losses.

7.5.1. Mix-Wise Interpretation in Light of Cross-Metric Trends

R1 (100% cement). The elevated pre-fire capacity results from a dense hydrate network with low capillary connectivity; however, the same permeability limitation causes vapor entrapment during the ISO 834-1 ramp. The resulting pressure transients appear macroscopically as explosive spalling (see

Figure 14a), extensive material detachment (

Figure 15), and a significant loss of residual capacity (

Figure 16a,b). The post-fire compression response shows a through-section fracture with notable fragment release (

Figure 17a). In the cross-metric view, R1 falls into the “high pre-fire MPa/high proportional reduction” quadrant of

Figure 18, aligning with its position near the upper envelope of the figure.

R2 (50% slag). Replacing 50% of clinker with GGBFS reduces early-age strength compared to R1, consistent with the slower kinetics of slag hydration at the tested maturity [

73]. Although the overall mass loss is slightly lower than in R1 (

Figure 15), the proportional capacity loss is higher (

Figure 18), indicating that the slag-bearing matrix remained vulnerable to thermally induced damage under rapid heating. The fracture pattern, characterized by shallow delaminations overlaid on corner loss (

Figure 14b), and the more brittle response after fire (

Figure 17b), suggest that the ITZ and matrix lacked sufficient pressure-relief pathways at higher temperatures. In

Figure 19, R2 plots at intermediate pre-fire MPa levels still show a significant reduction, emphasizing the maturity sensitivity of slag systems at this age.

R3 (90% cement, 10% biochar). Despite having acceptable pre-fire strength, R3 shows the worst fire-stage performance, marked by the highest mass loss (

Figure 15), the largest proportional reduction (

Figure 18), and severe corner and edge deterioration (

Figure 14c). This outcome aligns with a microporous, water-retentive carbon phase that increases internal surface area and moisture storage; during rapid heating, this causes localized pore-pressure surges and erosive detachment, diverging from the benefits sometimes seen at lower biochar doses [

11]. The post-fire compression pattern (

Figure 17c), with deep primary fractures and fine, randomly oriented fissures, indicates widespread microcrack coalescence layered on top of dominant failure planes. In

Figure 19, R3 is consistent with the high-reduction regime, even though it only had moderate pre-fire MPa.

R4 (50% slag + PP fibres). PP fibres reduce explosive spalling by melting to create temporary venting channels, as shown by the relatively low mass loss (

Figure 15) and the lack of violent detachment in

Figure 14d. However, the retained strength remains limited (

Figure 16b), and the post-fire compression response displays a network of distributed cracks rather than catastrophic fragmentation (

Figure 17d). This decoupling lessens fragmentation without a proportional preservation of load-bearing capacity, placing R4 at a moderate pre-fire MPa, but with a significant reduction, as indicated in

Figure 19, and in the mid-range of

Figure 18.

R5 (95% cement, 5% hydrochar). Even a small hydrochar fraction decreases the baseline capacity, but the mass-loss behavior remains close to R1–R2 (

Figure 15). The proportional reduction occurs in the middle range (

Figure 18), indicating that the pore-network modification is not enough to reach the threshold needed for significant pressure relief during the most intense heating phase. Morphologically,

Figure 14e shows clear surface degradation without ejection, and

Figure 17e confirms relatively limited cracking compared to the most damage-prone mixes. In

Figure 19, R5 is at a lower pre-fire MPa with an intermediate reduction.

R6 (90% cement, 10% hydrochar). Increasing hydrochar seems to push the system past a permeability or compliance threshold: explosive spalling is not seen (

Figure 14f), mass loss remains among the lowest (

Figure 15), and the retained fraction improves (

Figure 16b) despite the lower baseline MPa (

Figure 16a). The post-fire compression pattern (

Figure 17f) is characterized by controlled cracking rather than widespread detachment. Consequently,

Figure 19 shows R6 at the lower MPa/lower reduction point, and

Figure 18 verifies a reduction smaller than that of R1–R4.

R7 (80% cement, 20% hydrochar). The highest hydrochar replacement results in the smallest proportional loss (

Figure 18) and low mass detachment (

Figure 15), with minimal visible cracking during fire exposure (

Figure 14g) and a widespread but non-catastrophic crack pattern under post-fire compression (

Figure 17g). The trade-off is a lower absolute pre-fire capacity (

Figure 16a); however, the retained fraction remains the best in the series (

Figure 16b). In

Figure 19, R7 represents the corner of “low pre-fire MPa/low proportional reduction,” illustrating a robustness-focused design approach where microporosity and controlled gradients shift failure from explosive fragmentation to managed cracking. Overall, the analysis across

Figure 15,

Figure 16a,b,

Figure 18, and

Figure 19 reveals two performance groups: (i) dense or maturity-limited systems (R1–R3, partly R5) with higher initial MPa but weaker thermal robustness, and (ii) vented/mesoporous systems (R4, R6, R7) that minimize fragmentation and, for hydrochar-rich mixes, reduce proportional loss—even if they compromise pre-fire strength.

7.5.2. Cross-Metric Implications for Testing and Design

Taken together,

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 18 and

Figure 19 suggest two practical strategies for fire-resistant design. The first is engineered venting, exemplified by PP fibres (R4), which reliably prevents explosive failure and minimizes mass loss. The second involves tuning the pore network through hydrochar (R6–R7), which not only limits fragmentation but also reduces proportional strength loss in this dataset. Neither method alone guarantees high absolute residual strength: achieving that requires a baseline capacity sufficient to meet service demands after the expected percentage loss. Therefore, the design should focus on post-fire performance targets, combining (i) minimum pre-fire MPa, (ii) maximum allowable reduction (%), and (iii) acceptable damage mode (fragmentation vs. controlled cracking). When safety margins depend on residual capacity—such as in columns with limited redundancy—hybrid strategies that combine moderate hydrochar with low-dose fibres seem promising, provided curing and maturity are carefully controlled to prevent early-age deficits.

7.5.3. Robustness Checks and Sources of Uncertainty

Interpretation must recognize several constraints inherent to small-scale testing. Variability between specimens, local temperature gradients within the furnace, and moisture content fluctuations introduce noise into mass-loss and strength measurements. Additionally, some specimens (notably R1–R3 and R5) were subjected to post-fire compression in a damaged state due to splitting, which reflects real-world post-fire assessment but diverges from ideal protocols that test intact cubes. The mass-loss metric combines material detachment with evaporated moisture, so low mass loss does not necessarily indicate high residual MPa unless considered alongside

Figure 16a,b and

Figure 19. Finally, slag systems (R2, R4) are known to be sensitive to maturity; later ages or activation strategies may alter their position on the strength–robustness spectrum, requiring targeted follow-up.