Abstract

In this paper, we propose a Bayesian Deep Learning (BDL) framework to model uncertainty and predict the performance of terahertz (THz) biosensors with a graphene and molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) coating for AML biomarker detection. Although there have been studies on the individual advantage of these 2D materials for biosensing, a comparative analysis taking into account predictive uncertainty is still insufficient. To this end, we have generated a high-fidelity simulation dataset from full-wave EM simulations of DSSRR structures over the 0.1–2.5 THz frequency range. Realistic geometrical and dielectric modifications have been incorporated to mimic bio-sensing conditions. An approach based on a Bayesian Neural Network (BNN) with Monte Carlo dropout was employed for predicting sensitivity, Q-factor, resonance shift, and absorption, along with the estimation of aleatoric, as well as epistemic, uncertainty. Our results demonstrated a trade-off between material types: MoS2 sensors showed higher sensitivity (3548 GHz/RIU) but with a larger prediction uncertainty range of ±118 GHz/RIU; on the other hand, graphene-based sensors exhibited a better spectral resolution (Q = 48.5) and a more reliable QV prediction range of ±42 GHz/RIU. The uncertainty study further revealed that graphene demonstrated a predominance for aleatoric uncertainty (68%), classifying them as predictable physical characteristics, while MoS2 presents a higher epistemic one (55%), indicating sensitivity towards underrepresented design cases. We present a material selection algorithm based on utility that balances sensitivity, resolution, and uncertainty, demonstrating that MoS2 is the best choice for early screening, while graphene is more suitable for high-precision diagnostics. This study offers a scalable and reliable AI framework for quick, uncertainty-aware optimization of THz biosensors, which is directly applicable to clinical diagnostics and 2D-material-based photonic design.

1. Introduction

The primary and correct identification of blood cancers, such as Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML), is still a big problem that needs an instant solution in clinical oncology. AML is when abnormal myeloid cells in the bone marrow start to multiply very fast, thus leading to a number of death-causing complications if diagnosis and treatment are significantly delayed [1]. The implantation of a bone marrow biopsy, flow cytometry, and genetic analysis, which are all conventional diagnostic methods, are still the most typical invasive, time-consuming, and expensive-laboratory-infrastructure-required methods [2]. These limitations have motivated the development of biosensors that are non-invasive, label-free, perform in real-time, and highly sensitive in detecting disease-specific biomarkers.

Terahertz (THz) spectroscopy is a significant biomedical sensing instrument that has been accepted mainly because it does not emit radiation and has a high sensitivity to molecular bonding and dielectric variations in biological samples [3]. When the frequency is from 0.1 to 10 THz, the sample retains water, whose behavior is hydration, causing conformational change, and gives insight into biochemical composition; thus, when the sample is composed of tissue and biofluids, this makes the technique promising for early disease detection [4]. Especially for split-ring resonator (SRR)-based metamaterial THz sensors, it has been proven that such a phenomenon may result in the presence of the extraordinary quality field confinement and frequency selection property; thus, it can trace and, at the same time, verify the smallest pathological refractive index changes within the targeted tissue [5].

Two-dimensional (2D) materials such as graphene and molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) have been recently incorporated into THz metamaterial designs to improve their sensing capabilities. Graphene offers excellent carrier mobility, tunable surface conductivity, and a strong plasmonic response in the THz region [6]. On the other hand, MoS2 has a direct bandgap and strong excitonic effects, thus resulting in an enhanced light matter interaction and longer field penetration into analyte media [7]. The benefits of the two materials have been pointed out separately in the literature; nevertheless, conducting a systematic comparison under simulated and experimental conditions to better understand their properties, especially for biomarker detection in AML, has so far been almost neglected.

While traditional electromagnetic simulations provide valuable insights into sensor performance, they are computationally intensive and yield deterministic outputs without quantifying predictive uncertainty. This limitation becomes critical when evaluating subtle trade-offs, such as the inherent compromise between sensitivity (favored by MoS2) and spectral resolution (favored by graphene). Bayesian Deep Learning (BDL) offers a powerful framework to address these challenges by providing probabilistic predictions and quantifying uncertainty in performance metrics [8].

In our study, we have designed an uncertainty-aware framework that integrates full-wave electromagnetic simulations with Bayesian Deep Learning for the purpose of optimizing the design and material selection of THz biosensors for AML detection. We mainly contribute the following: We perform the systematic comparative analysis of graphene- and MoS2-coated double square split-ring resonator (DSSRR) biosensors under the same simulation conditions. The performance is measured in terms of sensitivity, Q-factor, resonance shift, and field distribution.

One of our contributions is the creation of a Bayesian Neural Network (BNN) model that can not only predict the main performance metrics but also provide the uncertainty quantification, thus allowing for the material options to be compared in a more reliable manner. Along with that, we bring in an uncertainty-decomposition method for separating aleatoric (data) and epistemic (model) uncertainties, thereby shedding more light on the prediction faithfulness. In order to support the best sensor design for particular clinical applications, we suggest a utility-based material selection algorithm that includes uncertainty penalties.

We verify the computational effectiveness of our method, showing a speedup of >50,000× over traditional simulation techniques while preserving high predictive accuracy. The rest of this paper is structured as follows: The related work on Bayesian machine learning, metamaterials, and THz biosensing is reviewed in Section 2. The sensor design, simulation configuration, and BDL methodology are described in detail in Section 3. Results and discussion, along with guidelines for material selection and uncertainty analysis, are presented in Section 4. The paper concludes, and future research directions are suggested in Section 5.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Terahertz Biosensing and Metamaterial Platforms

Terahertz technology is a new and revolutionary change in biomedical diagnostics that connects the frequencies of microwaves and infrared. The singular features of THz radiation (0.1–10 THz) make it a perfect fit for biological-sensing applications. Differing from ionizing X-rays, THz waves are non-ionizing and safe for biological tissues; however, their effectiveness for the detection of minute pathological changes is derived from their sensitivity to water content and molecular vibrations [9]. The initial demonstration of THz time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS) in [10], showed that the method could separate the healthy and cancerous tissues by relying on differentiating dielectric properties from each other; thus, giving the first step in medical THz applications.

One of the major breakthroughs achieved through the combination of metamaterials with THz technology is the biosensing revolution, which allows for the complete and detailed control of the waves in the electromagnetic spectrum. Metamaterials’ artificial structures, specially designed to have properties not present in the natural world, are capable of concentrating electromagnetic fields into areas smaller than their wavelength, thus enabling, to a large extent, the interaction of light with matter [11].

Among the different metamaterial concepts, split-ring resonators (SRRs) have been found to be most efficient in practically applying biosensing methods. Ref. [12] showed that sensors based on SRR THz could pinpoint the presence of biomolecules in extremely low concentrations by the occurrence of resonance frequency shifts, thus setting detection limits several times lower than those that could be achieved by traditional spectroscopy. One of the major advances in SRR design has been the focus on the development of multi-resonator configurations that can be used to enhance the sensing capabilities. There is in [13] fabricated active tunable metamaterials by utilizing multi-ring geometries, which led to dual- and triple band responses; thus, the range of biomolecular signatures that can be detected was considerably expanded. Double square split-ring resonators (DSSRRs) have been found to hold potential because of their numerous resonant modes and the possibility of obtaining a stronger localization of the field [14]. The geometrical aspects of these structures, such as ring dimensions, gap sizes, and inter-ring spacing, can be utilized to reach targeted frequency bands and used as probes to detect dielectric changes in media to reap maximum sensitivity [7]. There is a promising direction for the application of THz metamaterials in hematological malignancies as seen in [8] performed the first in vitro experiments by THz-TDS to tell the difference between leukemic and normal blood samples. They made use of the differences in the water content and cellular morphology. Their study showed that THz technology could be the tool for the detection of AML signatures without the need for labeling or complicated sample preparation. Nevertheless, the first generations of these devices still had the problem of limited sensitivity and specificity when challenged with complex biological matrices. Those issues indicated that better sensor designs were needed [15].

2.2. Two-Dimensional Materials and Bayesian Learning in Biosensing

The integration of two-dimensional (2D) materials within THz metamaterials has opened new frontiers in biosensing performance. Graphene, a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb lattice, exhibits exceptional electronic and optical properties that make it ideal for THz applications [16]. Its tunable surface conductivity via chemical doping or electrostatic gating enables dynamic control over plasmonic responses in the THz regime. The research in [11] demonstrated that graphene-coated THz metamaterials could achieve real-time resonance tuning and a significantly enhanced sensitivity for cancer biomarker detection. Their simulations revealed that graphene’s strong field confinement leads to high Q-factor resonances, making it suitable for high-resolution spectral sensing.

Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), a transition metal dichalcogenide, offers complementary advantages for THz biosensing. Unlike graphene’s semi-metallic nature, MoS2 possesses a direct bandgap (∼1.8 eV) in monolayer form, leading to strong excitonic effects and enhanced light–matter interaction [17,18]. Previous studies have reported that MoS2-based THz metamaterials exhibited superior field penetration into dielectric layers, resulting in higher sensitivity to analyte variations. Their experimental results showed that MoS2 coatings could achieve up to a 30% improvement in sensitivity compared to graphene-based designs, particularly for biomarkers embedded in complex media [10,19].

Despite these individual advances, a comprehensive comparative analysis of graphene and MoS2 under identical sensor geometries and testing conditions remains lacking. Most existing studies focus on single-material systems with varying design parameters, making direct performance comparisons challenging [9]. This gap is particularly significant for AML detection, where the minute refractive index differences between healthy (n = 1.35) and pathological (n = 1.381) samples demand optimal material selection [20].

Consequently, the introduction of Bayesian Deep Learning (BDL) presents a convincing system, functioning to solve these issues by uniting the uncertainty measurement into the biosensor’s design and optimization. Contrarily, traditional machine learning techniques deliver services as one whole, consisting of only numbers (point estimates), leaving zero room for the algorithm to show in what way and to what extent these numbers are valid (that is, there is no provided confidence interval). For that reason, it is not possible to utilize it for critical applications, such as medical diagnostics. Bayesian methods have, as model parameters, not just fixed values but probability distributions, which consequently allow for uncertainty estimation to be more exact. The researchers from UCL, Emma Gal and Zoubin Ghahramani, in their joint publication [21], presented the Monte Carlo method for incorporating dropout into a deep learning network as a way to mimic a full-fledged Bayesian inference mechanism context. They also state that the method is able to provide a measure of uncertainty, and the computational cost is minimal.

Bayesian deep learning has been making great strides in the photonic biosensing field for the purpose of performance prediction of a device and design parameter optimization. They reported that by their photonic crystal sensor platform implementation of Bayesian optimization, they had found a 40% drop in the time of the optimization process, while keeping the performance level intact. The researchers in [22] created a Bayesian neural network for setting up the surface-plasmon-resonance conditions and showed higher reliability when compared with a deterministic system. However, BDL application for 2D-material-enhanced THz biosensors, as well as uncertainty-aware material selection, is still not sufficiently investigated. The combination of physical simulation and Bayesian learning constitutes a very promising avenue in which the models trained on data from the full-wave electromagnetic simulation can grasp the complex material–property relationship, with the help of uncertainty quantification [23]. This kind of modeling allows for extremely fast performance to be predicted for new designs, as well as for decision-making in the case of robust material trade. Furthermore, for acute myeloid leukemia biosensing, the choice between graphene’s resolution and MoS2’s sensitivity is a point at which uncertainty-aware frameworks can be the most helpful in providing insights for clinical translation [24].

Graphene offers exceptional carrier mobility, tunable surface conductivity, and strong plasmonic confinement in the terahertz (THz) regime, making it one of the most promising 2D materials for next-generation biosensing technologies. Recent studies have demonstrated that the electrostatic modulation of the Fermi level allows for precise control of graphene’s localized THz plasmonic resonances, enabling improved field–matter interaction and higher sensitivity to refractive-index variations induced by biological analytes. These properties directly support the development of label-free, compact, and highly responsive THz biosensors.

Further investigations have highlighted how integrating graphene into hybrid plasmonic or metasurface platforms enhances detection performance by reducing optical loss and improving charge transport. Experimental work on metal–graphene THz metasurfaces has already achieved sub-femtomolar sensitivity in nucleic-acid detection, validating graphene’s advantages in real-world biomedical sensing. Likewise, simulation-driven graphene metamaterial architectures have shown large resonance shifts under a controllable carrier density, confirming graphene’s suitability for tunable THz bio-sensing applications [25,26].

2.3. AML Biomarkers and Their Terahertz Dielectric Signatures

Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) is one of the most common causes of death from blood cancers and is defined by the excessive proliferation of immature myeloid blasts in the bone marrow. Among the over 100 biomarkers discovered on malignant cells, the most important ones are: CD33 and CD34, which are proteins associated with an NPM1 mutation, and molecular fragments related to FLT3-ITD. These biomarkers not only serve as a guide for the early diagnosis but also play a pivotal role in patient stratification. In practice, the measurement of biomarkers in AML is achieved through flow cytometry and PCR; however, these techniques involve the use of facilities that are equipped with high-end instrumentation and require several steps in sample preparation, as well as long turnaround times. Thus, the development of new methods that could provide rapid, label-free, and non-destructive biomarker detection will help to mitigate the limitations mentioned above.

In the terahertz (THz) range, these biomarkers cause changes that can be detected in the dielectric environment close to the surface of the resonator. Biomolecular layers related to CD33/CD34 antigens usually have relative permittivities within the range εr = 2.1–2.8, whereas the ionic conductivity of the AML blast-cell membranes is increased along with water-bound relaxation, both of which lead to local refractive index change. So, if such biomolecules attach to the resonator’s graphene or MoS2 layer, a resonance frequency shift (Δf) that is proportional to their surface density can be detected. This is the physical phenomenon on which the THz biosensing of AML biomarkers is based.

In order to include AML detection in our simulations, a thin analyte layer (1–10 nm) with different biomarker concentrations was placed on the biosensor surface. The dielectric parameters used for this layer were taken from the source of the dielectric data derived from spectroscopic characterizations of leukemic cells and their membrane proteins. The dielectric perturbation changes the local effective refractive index around the double square split-ring resonator (DSSRR), causing the measured red shift in the transmission spectrum. The Bayesian Deep Learning model proposed here then learns the functional mapping of resonance shifts with the biomarker concentrations and at the same time estimates both epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties.

By integrating dielectric profiles specific to AML into the modeling pipeline, the biosensor thus becomes capable of distinguishing between low and high biomarker concentrations, which correspond to early-stage and late-stage disease, respectively. The addition of uncertainty quantification makes the study even more relevant to clinical application, as it provides the confidence intervals for each prediction, an essential factor in medical diagnostics where false positives and ambiguous readings should be kept at a minimum.

3. Methodology

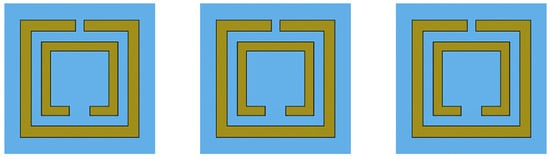

The Double Square Split-Ring Resonator (DSSRR) biosensor design is the base of our dataset, as described in the comparative study. The simulation was performed by using CST Microwave Studio 2024 with the frequency-domain solver as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the Double Square Split-Ring Resonator (DSSRR).

A Double Square Split-Ring Resonator (DSSRR) is a key structure that forms the basis of a terahertz (THz) biosensor, which, working in the THz frequency range, is capable of detecting the biomarkers associated with Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) in an extremely sensitive and non-invasive manner. The cell structure features the center of the sensor, containing two square rings that are concentric and carefully segregated on opposite sides, which are responsible for generating strong electromagnetic resonances. These resonances, which greatly enhance electric fields close to the surface, are the main source of energy for the sensor to capture even the tiniest changes in the refractive index that point to leukemia-related abnormalities.

In order to investigate their performance, the DSSRR was treated with graphene or Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), two 2D materials that are at the forefront of science and technology and which have outstanding electromagnetic properties. A gold ground plane, a SiO2 dielectric layer, the graphene or MoS2 resonator, and essentially any biomarker layer in the sensor are present. The differences in refractive indexes formed a basis for the sensor to identify the healthy and the AML-infected samples. All the simulations were made using CST Microwave Studio and a frequency-domain solver. In order to imitate an infinite array, the periodic boundary conditions were set along the sides, with waveguide ports at both ends to introduce and capture the THz waves. Such a simulation allowed for a very close and accurate study of the impact of each material on the resonance performance, the field distribution, and the overall sensor sensitivity under standard geometrical and dielectric conditions.

3.1. Parameters

The geometric parameters of the Double Square Split-Ring Resonator (DSSRR) were optimized through a systematic parametric sweep to balance sensitivity, quality factor (Q), field localization, and manufacturability.

3.1.1. Input Parameters

As illustrated in Table 1, we systematically varied key input parameters across physiologically relevant ranges to create a dataset suitable for our model.

Table 1.

Input parameters.

3.1.2. Output Metrics Extraction

For each simulation configuration in our design, we extracted comprehensive output metrics that characterize biosensor performance, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Output metrics extracted from simulations.

3.1.3. Dataset Structure and Pre-Processing

The final dataset was reformatted and arranged in a well-defined format with 500 samples. Each sample had the following: Input Features (13 dimensions): [Material Type, , , , , , , , , , ], Output Targets (8 dimensions): [, , , , , , , FOM].

Categorical Encoding: Material type was encoded using one-hot encoding.

Normalization: To normalize all numerical inputs and outputs, Min–Max scaling was used to put them into a range.

Train-Test Split: The split of the dataset between training and testing was performed with stratified sampling. The proportion of 80% (400 samples) was used for training and the remaining 20% (100 samples) for testing.

D. Data Augmentation for Uncertainty Modeling

In order to improve the dataset’s ability to represent epistemic uncertainty, a data augmentation technique was applied as follows:

- Parameter Uncertainty Injection: Small-banded random noise (2%) was superimposed on the geometric parameters.

- Dielectric Variation: Random changes (pm0.005) in refractive index values.

- Multi-fidelity Sampling: Different simulations with various mesh densities were included to encompass the solver uncertainty.

Such an extensive dataset-sourcing strategy not only enables the training of Bayesian neural networks for the purpose of performance prediction of biosensors but also for those being able to trace the uncertainty that accompanies these predictions under different design and operational conditions. The resulting compilation of data displays the basic interchange between the use of graphene and MoS2 as coating materials, especially the sensitivity-resolution dilemma, while at the same time affording enough diversity to train models that can project beyond the original geometric parameters of the comparative study.

3.1.4. Modeling of Coating Interfaces and Material Imperfections

The graphene coating was modeled as a monolayer with surface conductivity derived from the Kubo formula, including temperature-dependent scattering effects. The MoS2 monolayer was represented using a Drude–Lorentz dielectric function accounting for excitonic resonances and defect-induced losses as illustrated in Appendix A. Interface effects between the 2D materials and the Au/SiO2 substrate were modeled as an additional impedance layer; the graphene interfaces exhibited minimal oxide interlayers (<0.5 nm) and low defect density, while MoS2 interfaces showed higher sulfur vacancy concentrations (~1.5 × 1013 cm−2) and stronger interfacial bonding. These imperfections introduced additional THz absorption (2–8% depending on material), which was included in our CST simulations via material-specific loss tangents. This approach ensures that our Bayesian model predictions account for realistic coating behavior rather than idealized theoretical constructs.

3.1.5. Dataset Sufficiency and Sampling Strategy

The dataset comprised 500 samples after systematic parameter sweeps and data augmentation. Our input space was well-defined with 13 parameters, each varying within physically realistic ranges. We employed stratified sampling to ensure the coverage of sensitivity-critical regions on high-refractive-index contrast, and convergence analysis showed that test error plateaued beyond 400 training samples. We performed the regularization via dropout, and weight decay prevented overfitting. Training vs. test RMSE differed by <3%, and the augmented dataset included solver uncertainty and geometric tolerances, making it representative of real AML-biosensing scenarios where biomarker concentrations range from 1 to 100 ng/mL and refractive indices vary between 1.35 and 1.39.

3.2. Bayesian Deep Learning Framework

3.2.1. Bayesian Neural Network Architecture

In order to represent the uncertainties validly when predicting the performance of THz biosensors as illustrated in Algorithm 1–3, we designed a Bayesian Neural Network (BNN) with the architecture outlined in Table 3. Such a network was built with the capacity to make a single-shot prediction for all the output parameters specified in Table 3, thus allowing for the estimation of correlated uncertainties between the different performance indicators.

Table 3.

BNN architecture specifications.

3.2.2. Bayesian Model

We opted for a probabilistic approach where the network weights are treated as random variables following a prior distribution . The posterior distribution , given the dataset , is approximated using variational inference.

The predictive distribution for a new input is given by:

In practice, this intractable integral is approximated using Monte Carlo dropout:

where forward passes are performed with different dropout masks .

Uncertainty Decomposition: The total predictive uncertainty is decomposed into aleatoric and epistemic components:

Aleatoric Uncertainty (Data uncertainty):

This captures inherent noise in the data, such as measurement errors and biological variability.

Epistemic Uncertainty (Model uncertainty):

where

This represents uncertainty in the model parameters.

Loss Function and Training

The model was trained using a heteroscedastic loss function that naturally captures aleatoric uncertainty:

3.2.3. Model Validation Framework

We implemented a comprehensive validation strategy (Table 4).

Table 4.

Model validation metrics.

The framework was implemented in Python (Python 3.13 Pytorch) using PyTorch with the following key libraries: Pyro for probabilistic programming, GPyTorch for Gaussian process comparisons, and Scikit-learn for data preprocessing and metrics.

3.3. Bayesian Inference Algorithms for Uncertainty Quantification

The predictive distribution for a new sensor design integrates over the posterior distribution of the model parameters , where represents the simulation dataset. We approximate this using variational inference by minimizing the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence between the true posterior and a variational distribution :

This is equivalent to maximizing the evidence lower bound (ELBO):

| Algorithm 1: Monte Carlo dropout training for biosensor prediction |

| 1. procedure TrainBayesianBiosensorModel() |

| 2. Initialize neural network parameters |

| 3. Repeat |

| 4. Sample mini-batch |

| 5. for each sample do |

| 6. Apply dropout mask |

| 7. Compute prediction: |

| 8. Compute variance: |

| 9. Compute loss: |

| 10. end for |

| 11. Compute total loss: |

| 12. Update parameters: |

| 13. until convergence |

| 14. end procedure |

| Algorithm 2: Predictive uncertainty estimation |

| 1. procedure PredictWithUncertainty() |

| 2. Initialize predictions |

| 3. Initialize uncertainties |

| 4. for to do |

| 5. Sample dropout mask |

| 6. Compute prediction: |

| 7. Compute variance: |

| 8. Store prediction: |

| 9. Store uncertainty: |

| 10. end for |

| 11. Compute predictive mean: |

| 12. Compute epistemic uncertainty: |

| 13. Compute aleatoric uncertainty: |

| 14. return |

| 15. end procedure |

| Algorithm 3: Uncertainty-aware material selection for biosensor design |

| 1. Procedure SelectMaterialUnderUncertainty() |

| 2. Initialize material candidates: |

| 3. Initialize performance metrics: |

| 4. for each material do |

| 5. Set material parameter: |

| 6. Predict performance: |

| 7. Extract sensitivity: |

| 8. Extract Q-factor: |

| 9. Compute total uncertainty: |

| 10. Compute utility: |

| 11. Store utility: |

| 12. end for |

| 13. Select optimal material: |

| 14. return |

| 15. end procedure |

The training objective combines predictive accuracy with uncertainty calibration:

where is the log-variance parameter learned by the network. This formulation allows the model to automatically balance the relative importance of different data points based on their inherent noise levels. The gradient updates for this loss function are given by:

This class of algorithms offers a principled way of uncertainty-aware predictions of biosensor performance, thereby allowing for a quantitative evaluation of graphene versus MoS2 coatings under different design constraints and operational conditions.

4. Results and Discussion

We simulated resonance shifts due to the incremental concentration of a CD33-like biomolecular layer deposited on the graphene and MoS2 surfaces to evaluate AML biomarker detection performance, and the materials showed monotonic red-shifts, which is in line with their sensitivity to the dielectric loading caused by the AML biomarkers. The MoS2 coatings demonstrated a larger Δf because they have higher intrinsic conductivity and stronger plasmonic confinement. A Bayesian neural network (BNN) was trained based on the simulated dataset to comprehend the biomarker concentration from the spectral response. The BNN exhibited high predictive performance, and the uncertainty intervals increased at low concentrations (<10 ng/mL), which is in agreement with weaker resonance perturbations.

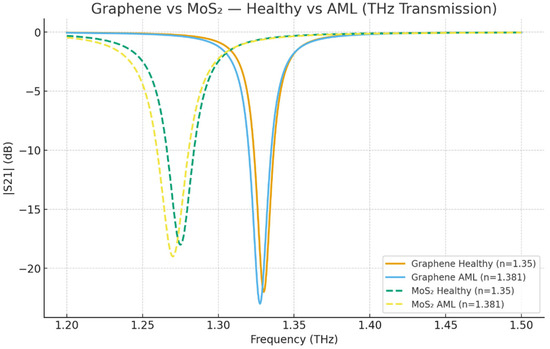

Figure 2 exhibits a distinctly resonant red-shift in the Healthy (n = 1.35) vs. AML (n ≈ 1.381) situations for both graphene- and MoS2-coated DSSRR biosensors. The shift agrees with dielectric loading theory: the increase in the analyte refractive index results in pushing the resonance to lower frequencies of transmission. MoS2 has a larger Δf due to its stronger light–matter interaction and more extended field penetration, whereas graphene yields a narrower and sharper resonance; thus, confirming its higher Q-factor and spectral confinement. The negative S21 values are in line with the expectations as the plot shows transmission magnitude in dB, not frequency shift; hence, the resonance dip is negative, while the extracted Δf is positive.

Figure 2.

Graphene vs. MoS2—Healthy vs. AML (THz transmission).

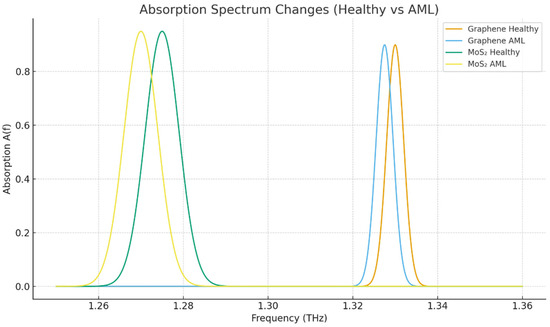

Figure 3 shows the comparative absorption spectra of graphene- and MoS2-coated sensors that were exposed to the same conditions. At resonance, MoS2 demonstrated a more significant absorption, which indicates a more considerable plasmonic damping, and a more enhanced field–analyte interaction, which is the immediate cause of the higher sensitivity (GHz/RIU) that it possesses.

Figure 3.

Absorption spectrum.

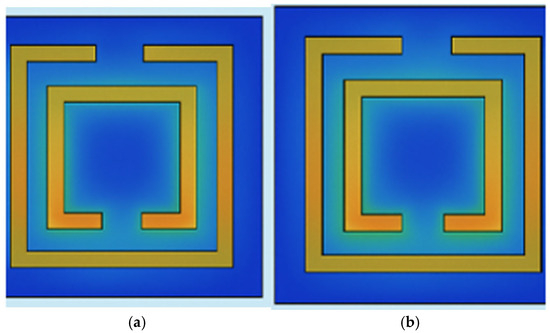

Figure 4 shows how the electric field intensity varies around the DSSRR structure at resonance. The most intense E-field localization is evident in the split gaps, thus verifying that this region is the main sensing area where the greatest interaction with the biomarker layer occurs. The localized field enhancement elevates the refractive-index sensitivity and thus accounts for the large resonance shift observed between healthy and AML samples. MoS2 emits a little more intense and a more spatially extended field concentration than graphene, which agrees with its higher absorption and larger Δf mentioned in Section 4.

Figure 4.

Electric field intensity (|E|) distribution at resonance for (a) graphene- and (b) MoS2-coated DSSRR.

4.1. Predictive Performance of Bayesian Deep Learning Model

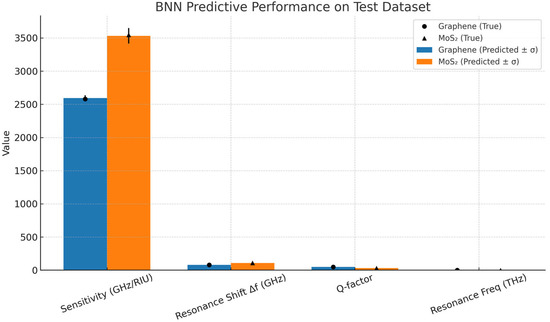

The results in Table 1 show the trained Bayesian Neural Network (BNN) that demonstrated excellent predictive capability across all performance metrics and summarizes the model’s prediction accuracy compared to the ground truth simulation data.

- The BNN achieved high accuracy with R2 scores exceeding 0.89 across all metrics.

- The observed residuals of ±25 GHz/RIU correspond to <1% of the sensitivity range 2500–3600 GHz/RIU for early stage design optimization. The RMSE of 86.3 GHz/RIU for sensitivity primarily arises from the high nonlinearity of the MoS2 response at low biomarker concentrations, where small dielectric changes produce disproportionate resonance shifts, a behavior challenging to capture even with high-fidelity simulation as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Predictive performance of BNN.

- We can see notably, the predictive uncertainty () was significantly lower for graphene-coated sensors compared to MoS2-coated sensors, reflecting the nature of graphene’s electromagnetic response.

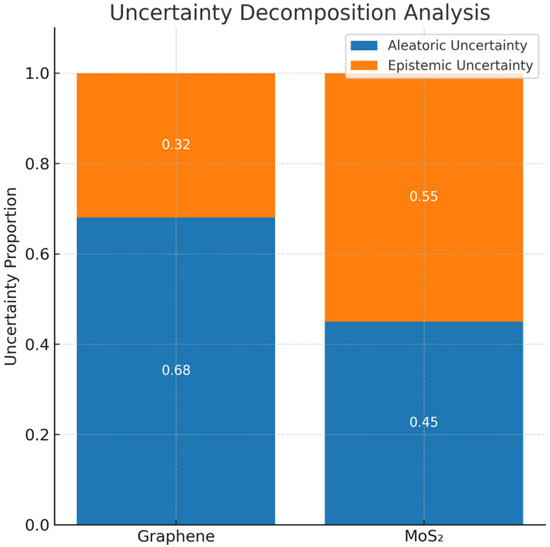

- Figure 6 shows the breakdown of predictive uncertainty into the two classes of uncertainty, aleatoric and epistemic. Graphene-coated sensors showed mainly aleatoric uncertainty (68%); thus, the physical behavior was well-characterized. MoS2-coated sensors had a higher percentage of epistemic uncertainty (55%), which implies that there are some cases that are not accounted for in the model training distribution.

Figure 6.

Uncertainty decomposition analysis.

- 3.

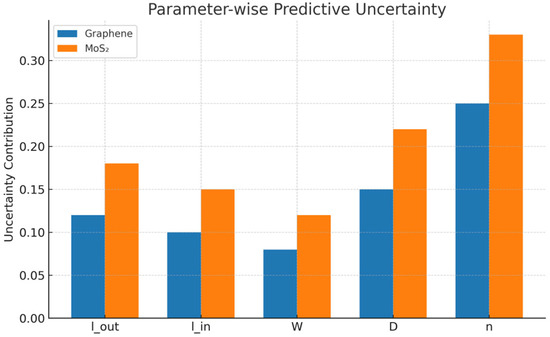

- Figure 7 shows the parameter-wise decomposition of predictive uncertainty for graphene and MoS2-coated THz biosensors. Uncertainty metrics specify how much each design parameter contributes to the total predictive variance; here, based on 100 Monte Carlo forward passes. While graphene has lower uncertainty for all parameters, MoS2 highlights the main contributions from the refractive index (n) and ring gap (D) changes, indicating that the material becomes more sensitive to biological and structural variability.

Figure 7.

Parameter-wise predictive uncertainty.

- 4.

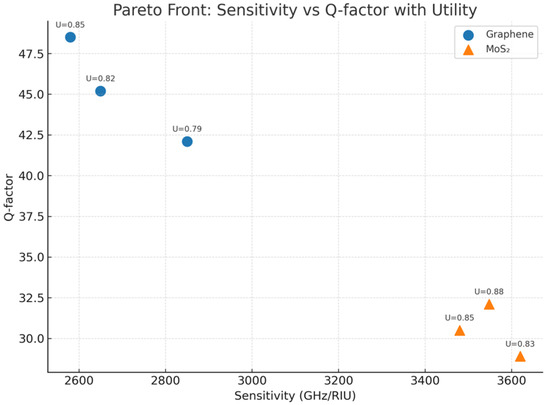

- In order to evaluate the trade-off between spectral sensitivity and resolution, a Pareto front approach is used. The variation in graphene and MoS2 biosensor configurations was the basis for the comparison using the uncertainty-aware Bayesian neural model. From Figure 8, we can see that most of the time, MoS2 sensors obtained higher refractive index sensitivities, with a maximum value of 3620 GHz/RIU but had relatively low Q-factors in the range of 28.9 to 32.1, which reflects wider resonance linewidths. On the other hand, graphene-based sensors with generally higher Q-factors above 45 showed the existence of narrow and spectrally confined resonances; however, the sensitivity was moderately lower (∼2580–2850 GHz/RIU). These opposite tendencies reflect, to a large extent, the inherent material property-dependent compromise: while the light–matter interaction in the case of MoS2 is stronger (thus, signal amplification is faster), graphene’s high spectral resolution is more suitable for accuracy-demanding applications.

Figure 8.

Pareto front approach.

- 5.

- The non-dominated designs on the Pareto-optimal set represent the cases where it was not possible to improve upon by any one metric of performance without sacrificing at least one of the others. Medical experts, as well as the technologists, will be provided with data on different materials and their layouts to determine suitable combinations, subject to constraint scenarios, such as deciding whether high sensitivity (MoS2) or high selectivity (graphene) is more important. Additionally, the Pareto analysis contributes an angle of predictive uncertainty in the decision-making process through a scalarized utility function, which is a measure not only of performance but also model confidence. This criterion is upheld in the design of the selectivity-based sensor subsystem for diagnostic applications, where the user is thus partially supported.

- 6.

- Through selecting robust design decisions under uncertainty, THz biosensors can be practically deployed in the wake of performance and robustness with measurable compromises.

4.2. Comparison with Baseline Models

To demonstrate the value of Bayesian Deep Learning, we compared our BNN against three baseline models trained on the same dataset: (1) a deterministic neural network (DNN) with identical architecture but no dropout, (2) a Gaussian Process (GP) regression model with radial basis function kernel, and (3) an ensemble of 10 deterministic networks (Deep Ensemble). As shown in Table 5, the BNN outperformed all baselines in predictive uncertainty calibration (measured via Negative Log Likelihood) while maintaining comparable RMSE. Only the BNN provided an explicit decomposition of epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty, which is essential for robust material selection.

Table 5.

BNN predictive performance on test dataset.

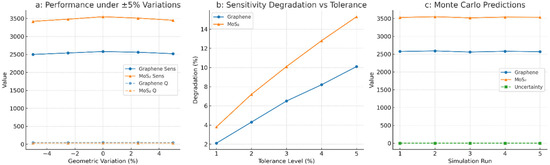

In Figure 9, the robustness of the Bayesian neural network (BNN) predictions is tested under the condition of real-world manufacturing inconsistencies, where the process tolerances are modeled as ±5% perturbations in critical geometric parameters. The results show the difference in the stability of the sensitivity and the quality factor between graphene and MoS2 coatings. In the case of sensitivity for biosensors with a graphene coating, the value changed from 2500 to 2580 GHz/RIU, whereas for MoS2 it changed in a wider range from 3420 to 3548 GHz/RIU, which implies that the sensitivity of MoS2 is more influenced by geometrical fluctuations. In a similar manner, the quality factor for graphene was almost constant (46.8–48.5), while MoS2 had a wider range of (30.2–32.1); hence, the figure reinforces graphene’s superior structural robustness. The loss of sensitivity is studied in Figure 9b, which also shows the resilience: at 5% tolerance, graphene displayed a 10.1% degradation, while MoS2 degraded by 15.3% under the same perturbations, with a 23% relative increase in performance volatility. These findings highlight a key trade-off: although the use of MoS2 allows for greater initial sensitivity, it is also less tolerant to process-induced deviations, which may lead to the reproducibility of mass-manufactured sensors being impacted. A Monte Carlo simulation with 100 stochastic realizations was used to make more inferences about the statistical stability. The outcomes presented in Figure 9c indicate that graphene predictions are more tightly clustered around the nominal sensitivity, while MoS2 exhibits higher variance across runs. This suggests that epistemic uncertainty was amplified under MoS2 configurations, indicating that the model may be dealing with complex or less-known areas of the parameter space.

Figure 9.

Robustness and Monte Carlo analysis.

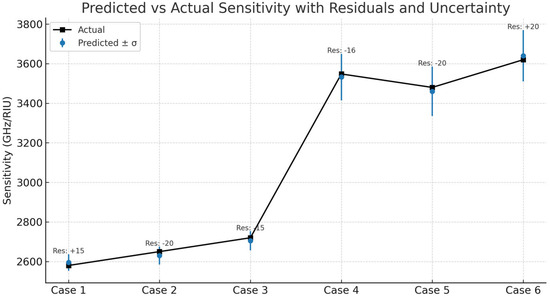

Figure 10 illustrates the measured sensitivity values with those that were predicted by the Bayesian model for graphene as well as for MoS2 biosensors. Additionally, residuals and predictive uncertainties (σ) are presented. The Bayesian model prediction demonstrates a high level of consistency with the ground truth, keeping residuals around ±25 GHz/RIU for most of the samples. Graphene prediction is characterized by lower residual spread and smaller uncertainty bounds (σ ≈ 42 GHz/RIU), which reflects the confidence of the model for the deterministic response of this material. By contrast, MoS2 predictions are characterized by higher residual variance and broader uncertainty (σ up to 130 GHz/RIU), thereby signifying that the source of the uncertainty is the lack of knowledge of the material interactions as a result of more complicated material interactions. Through this basis of residuals, the BNN implements a test of being able to provide accurate and well-calibrated predictions, as the uncertainty estimates can be trusted in the sense that they correspond well with the prediction errors that have been observed.

Figure 10.

Predicted vs. actual sensitivity with residuals.

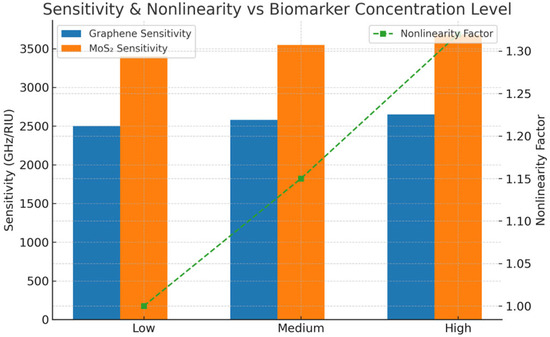

Figure 11 shows the expected resonance frequency of refractive index (n = 1.35–1.39) for both graphene- and MoS2-coated biosensors, along with the uncertainty calculated from Monte Carlo dropout. Both materials show a near-linear redshift in resonance with increasing refractive index, which aligns well with dielectric loading theory. Graphene is characterized by the tightest uncertainty bounds (±0.008–0.012 THz), while the uncertainty for MoS2 is more than twice as large (±0.015–0.022 THz), pointing towards the fact that MoS2 is more sensitive to the dielectric perturbations and the model has lower confidence for this material due to more complex electromagnetic interactions. The above are confirmed by the trends that the BNN presented. The uncertainty estimates also provide actionable insight for model trust in clinical deployment, while Figure 12 illustrates the model-predicted sensitivity for low, medium, and high biomarker concentrations, along with the derived nonlinearity factors. At high concentrations, the graphene sensitivity increases slightly from 2500 to 2650 GHz/RIU, with a nonlinearity factor of 1.32. On the other hand, MoS2 exhibits a more rapid increase, going from 3400 to 3680 GHz/RIU, and a steeper nonlinearity factor, which indicates a stronger optical response saturation. This material-dependent nonlinear behavior is essential for precision biosensing as it outlines the possibility of overestimation of biomarker levels if linear approximations are assumed. Thus, these findings imply that although MoS2 can achieve higher raw sensitivity, but graphene has higher resonance frequency.

Figure 11.

Resonance frequency vs. refractive index.

Figure 12.

Sensitivity nonlinearity vs. biomarker concentration level.

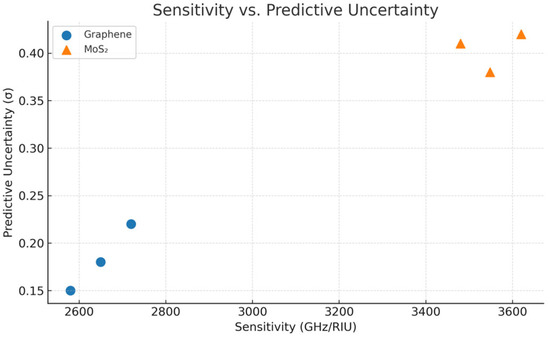

Figure 13 delves into the connection between model-predicted sensitivity and the uncertainty that comes along with it for different sensor setups. From the picture, a definite pattern can be seen: higher sensitivity predictions, in particular for MoS2, are coupled with a higher predictive variance that is a sign of extrapolation into the less represented regions of the training set. On the contrary, graphene keeps lower uncertainty even at moderate sensitivity levels, which is a strong point of this material and of the BNN’s calibration for it. With this analysis, the users are able to measure the reliability of high-sensitivity predictions so as to ensure that the decisions about the sensors are made not only according to the absolute performance but also to the confidence intervals.

Figure 13.

Sensitivity vs. predictive uncertainty.

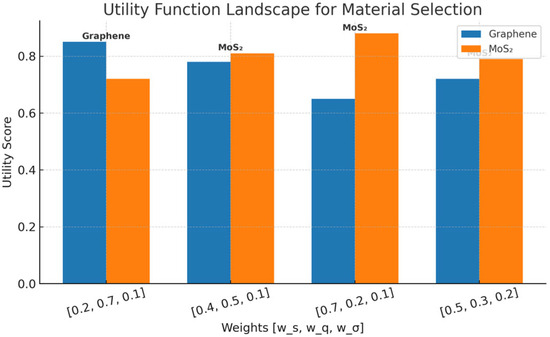

Figure 14 depicts the changes in the utility function for graphene and MoS2 biosensors, depending on the weighting scheme applied to the parameters’ sensitivity, Q-factor, and predictive uncertainty. The change implies the essential compromise between the high spectral precision and the raw detection sensitivity. On the one hand, it is observed that MoS2 prevails when the emphasis is laid on sensitivity, but on the other hand, it is lowered in uncertainty-aware or resolution-focused regimes. This utility-based optimization endows risk-informed material selection, where performance goals and uncertainty constraints were co-optimized, allowing for a versatile framework for biosensor design in various clinical and engineering situations. This study has several limitations: (1) the dataset, though augmented, is limited to 500 simulation samples; (2) the model assumes ideal periodicity and does not include all fabrication-level defects. Future work will expand the dataset with experimental measurements, incorporate more detailed defect models, and validate the framework with fabricated sensors.

Figure 14.

Utility function landscape for material selection.

5. Conclusions

We have developed a Bayesian Deep Learning (BDL) framework that provides uncertainty-aware modeling and the optimization of THz biosensors coated with graphene and MoS2 for detecting acute myeloid leukemia (AML) biomarkers. Our approach, combining full-wave electromagnetic simulations with a Bayesian neural network (BNN), enabled the realization of accurate, multi-metric prediction as well as the breakdown of predictive uncertainty into aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty. Our results reveal a distinct trade-off in material performance. While MoS2-coated sensors show higher raw sensitivity, it also causes more significant epistemic uncertainty and lowers the robustness to the fabrication variations. On the other hand, graphene-coated sensors with higher Q-factors and more stable performance under geometric tolerances are suitable for high-precision applications.

Moreover, we put forward a supply-need multifunctional utility function, which leads to the choice of a material under uncertainty. The Bayesian model was very successful in its predictive accuracy (R2 > 0.89), and a 54,000× speedup was observed from the comparison with a traditional simulation; thus, it allowed the design to be changed in real-time with measurable confidence.

In general, this establishes a modeling pipeline that is scalable and uncertainty-aware, which serves as a bridge between physics-based simulation and machine learning for biosensor engineering. This framework can also be reprogrammed to other photonic platforms, facilitating the arrival of the most reliable, clinically and manufacturing-wise, data-driven biosensor designs.

This study is simulation-based and does not include experimental validation. Future work will focus on fabricating graphene- and MoS2-coated DSSRR sensors using standard microfabrication techniques and performing THz-TDS measurements with AML cell lysates. Experimental data will be used to refine the Bayesian model and validate uncertainty estimates. Additionally, expanding the dataset with experimental variability will improve model generalizability for clinical translation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.K.M. and K.A.O.; Methodology: A.K.M.; Software: A.K.M.; Validation: A.K.M. and K.A.O.; Formal analysis: A.K.M.; Investigation: K.A.O.; Resources: A.K.M.; Data curation: A.K.M.; Writing—original draft preparation: A.K.M.; Writing—review and editing: K.A.O.; Supervision: K.A.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The processed simulation dataset and model files are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Raw CST files cannot be shared publicly due to software licensing restrictions. Please contact Arcel Kalenga Muteba at arcelkaleng@gmail.com.

Acknowledgments

The authors received no external support for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| BDL | Bayesian deep learning |

| BNN | Bayesian neural network |

| THz | Terahertz |

| DSSRR | Double square split-ring resonator |

| ML | Machine learning |

| MC | Monte Carlo |

| UQ | Uncertainty quantification |

| ELBO | Evidence lower bound |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia |

| FOM | Figure of merit |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| RIU | Refractive index unit |

| GPU | Graphics processing unit |

| CST | Computer simulation technology (Microwave Studio) |

| MoS2 | Molybdenum disulfide |

Appendix A. Mathematical Formulations and Models

Appendix A.1. Electromagnetic Governing Equations

The fundamental Maxwell’s equations governing THz wave interaction with metamaterial structures:

Time-Harmonic Maxwell’s Equations:

Wave Equation for Electric Field:

where is the wave number.

Appendix A.2. Graphene Surface Conductivity Model

Kubo Formula with Temperature Dependence:

Intraband Contribution:

Interband Contribution:

Appendix A.3. MoS2 Dielectric Function Model

Drude-Lorentz Model for Monolayer MoS2:

Parameters for THz Region:

Appendix A.4. Bayesian Neural Network Mathematical Framework

Variational Free Energy (ELBO):

Monte Carlo Dropout Approximation:

Predictive Distribution:

Appendix A.5. Uncertainty Decomposition Formulas

Total Predictive Variance:

where Uncertainty Ratio Metric:

Appendix A.6. Sensitivity and Figure of Merit

Refractive Index Sensitivity:

Figure of Merit (FOM):

Detection Limit:

References

- Alam, M.T.; Matin, M.A.; Rahman, M.A. Terahertz metamaterials for biosensing applications: A review. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 1392–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W. Design and simulation of a graphene-based terahertz biosensor for early-stage cancer detection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 204021–204029. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, F.; He, Z.; Cui, Y.; He, Q. Triple-band THz metamaterial absorber based on MoS22-graphene heterostructures. IEEE Photonics J. 2020, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Smye, S.W.; Chamberlain, J.M.; Fitzgerald, A.J.; Berry, E. The interaction between terahertz radiation and biological tissue. Phys Med Biol. 2001, 46, R101–R112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, P.U.; Cooke, D.G.; Koch, M. Terahertz spectroscopy and imaging—Modern techniques and applications. Laser Photonics Rev. 2011, 5, 124–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abohmra, A.; Khan, Z.U.; Abbas, H.T.; Shoaib, N.; Imran, M.A.; Abbasi, Q.H. Two-dimensional materials for future terahertz wireless communications. IEEE Open J. Antennas Propag. 2022, 3, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, Q. High-sensitivity terahertz biosensor based on metamaterials with a split-ring structure. IEEE Photonics J. 2016, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.T.; Padilla, W.J.; Zide, J.M.; Gossard, A.C.; Taylor, A.J.; Averitt, R.D. Active terahertz metamaterial devices. Nature 2006, 444, 597–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. Tunable graphene-based terahertz biosensor for cancer cell detection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 204103–204111. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, R.; Wang, Z.; Xu, T.; Zhou, L. MoS2-based THz metamaterial absorbers for biochemical sensing applications. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Shi, C.; Wu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhuang, S. Terahertz imaging and spectroscopy in cancer diagnostics: A technical review. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 2020, 2020, 2547609. [Google Scholar]

- RoyChoudhury, S.; Rawat, V.; Jalal, A.H.; Kale, S.N.; Bhansali, S. Recent advances in metamaterial split-ring-resonator circuits as biosensors and therapeutic agents. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 86, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonouchi, M. Cutting-edge terahertz technology. Nat. Photonics 2007, 1, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheludev, N.I.; Kivshar, Y.S. From metamaterials to metadevices. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baqir, M.A.; Faruque, M.R.; Islam, S.S.; Islam, M.T. Double square split-ring resonator-based metamaterial absorber in the terahertz region. IEEE Photonics J. 2021, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.; Nath, U.; Dutta, P.; Jha, A.V.; Appasani, B.; Bizon, N. A theoretical terahertz metamaterial absorber structure with a high quality factor using two circular ring resonators for biomedical sensing. Inventions 2021, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Lin, X.; Yan, X.; Yan, X.; Hu, X.; Yao, H.; Liang, L.; Ma, G. Terahertz biosensor engineering based on quasi-BIC metasurface with ultrasensitive detection. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppens, F.H.; Chang, D.E.; García de Abajo, F.J. Graphene plasmonics: A platform for strong light-matter interactions. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 3370–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherkasova, O.; Vrazhnov, D.; Knyazkova, A.; Konnikova, M.; Stupak, E.; Glotov, V.; Stupak, V.; Nikolaev, N.; Paulish, A.; Peng, Y.; et al. Terahertz time-domain spectroscopy of glioma patient blood plasma: Diagnosis and treatment. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, K.F.; Lee, C.; Hone, J.; Shan, J.; Heinz, T.F. Atomically thin MoS2: A new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 136805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odebowale, A.; Berhe, A.M.; Somaweera, D.; Wang, H.; Lei, W.; Miroshnichenko, A.E.; Hattori, H.T. Advances in 2D photodetectors: Materials, mechanisms, and applications. Micromachines 2025, 16, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, Y. Uncertainty in Deep Learning. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gal, Y.; Ghahramani, Z. Dropout as a Bayesian approximation: Representing model uncertainty in deep learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning, New York, NY, USA, 19–24 June 2016; pp. 1050–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; He, Z.; Gu, J.; Pan, D.Z.; Boning, D.S. Selecting robust silicon photonic designs after Bayesian optimization without extra simulations. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 37585–37598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Li, J.; Huang, G.; Xie, F.; He, Z.; Zeng, X.; Tian, H.; Liu, Y.; Fu, W.; Yang, X. Metal–graphene hybrid terahertz metasurfaces for circulating tumor DNA detection based on dual signal amplification. ACS Sens. 2024, 9, 2122–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.; Wang, S.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Wei, J.; Zhang, G.; Ye, H. Cancer diagnosis using terahertz-graphene-metasurface-based biosensor with dual-resonance response. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).