Abstract

Microalgae are extremely diverse photosynthetic organisms, adapted to live in different habitat conditions, from freshwater to marine environments. This adaptability is also associated with the ability to produce several metabolites. Polyunsaturated aldehydes (PUAs), first identified in 1999 in Thalassiosira gravida and Skeletonema costatum, are known to influence the development of their predators, having teratogenic effects and blocking their development. PUAs have shown several activities, such as antitumor, antimicrobial and antiparasite. Another relevant compound is pheophorbide a (PPBa), a chlorophyll degradation product, which has previously shown properties useful to be considered as a photosensitizer in photodynamic therapy, demonstrating cytotoxic effects on various tumor cell lines. It has also been shown to have activity against some bacteria and fungi. Considering the growing problem of multi-antibiotic resistance of human pathogenic bacteria and the increasing market demand for new drugs, the aim of our work was to screen two PUAs, i. e., 2,4-octadienal and trans,trans-2,4-decadienal, and PPBa against a panel of human pathogenic bacteria and fungi: Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus. The antimicrobial activity was evaluated through MIC (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration) and MFC/MBC (Minimum Fungicidal/Bactericidal Concentration), demonstrating that the two PUAs had a greater antimicrobial activity than PPBa on both bacteria and fungi, except for P. aeruginosa, where the antimicrobial activity was low. The compound 2,4-Octadienal showed extremely high antifungal activity, especially against the fungus A. fumigatus, where the MIC and MFC were 0.001 µL/mL and 0.004 µL/mL, respectively. These results are shedding light on the antimicrobial activity of microalgal compounds and their possible applications for different human infection diseases.

1. Introduction

Microalgae are photosynthetic organisms adapted to live in different habitat conditions, from freshwater to marine environments [1]. They are adapted to grow in very diverse conditions, ranging from high and low temperatures, to different light intensities, pH and salinity concentrations [2]. Marine microalgae have recently attracted the interest of scientific and industrial communities due to the plethora of biomolecules they can produce and the quite easy large-scale cultivation compared to macroorganisms, which allows for obtaining large quantities of biomass [3]. In 1999, Miralto and colleagues [4] isolated for the first time from marine diatoms three polyunsaturated aldehydes (PUAs), namely 2E,4Z,7Z-decatrienal, 2E,4E,7Z-decatrienal and 2E,4E-decadienal (DECA), from the microalgae Thalassiosira gravida (formerly Thalassiosira rotula), Skeletonema costatum (actually named as S. marinoi [5]) (Mediophyceae) and Pseudo-nitzschia delicatissima (Bacillariophyceae). After these first three PUAs, which are long-chain volatile oxylipins, several other oxylipins have been described, both from species cultivated in laboratory conditions and from natural diatom blooms at sea [6]. In fact, regarding their possible roles, they have been suggested to influence planktonic species abundance and distribution, regulating population dynamics and, at a bigger scale, shaping the marine food web. PUAs had the ability to block the embryonic development of their predators, such as copepods, tunicates and sea urchins [7,8]. For instance, it was demonstrated that the ingestion of PUAs by copepods induced a reduction in egg production, hatching success and the birth of abnormal nauplii, avoiding the next generation of predators [4,7].

Oxylipin production in diatoms seems to be triggered by cell membrane damage, and they are rapidly synthesized through the enzymatic oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids [9,10,11]. Although the teratogenic effects of PUAs on the larvae of several organisms were known as a mechanism to ensure the ecological success of microalgae [4,7,12,13,14], other activities have been found for PUAs such as cytotoxicity on different cancer cell lines [4,15], pest control in the aquaculture sector of mollusks infested by polychaeta parasites [16] and antimicrobial activity on marine bacteria isolates [17].

Another interesting compound produced by microalgae shown to have biotechnological applications, especially for the anticancer photodynamic therapy, is pheophorbide a (PPBa). Pheophorbides were known to be formed by the degradation of chlorophyll in plants and fruits that had reached the state of maturity/senescence and were useful for the transfer of nutrients from parts of the plant in senescence to tissues of the growing plant. The formation of PPBa is due to the use of two enzymes, chlorophyllase and the non-yellowing (NYE) and stay-green (SGR) proteins with Mg-dechelatase activity [18], leading to the formation of a tetrapyrole with four methyls, an ethyl, a vinyl, a methoxycarbonyl and a propionyl [19].

The use of PPBa has gained great success after the discovery of photodynamic therapy, especially in the treatment of cancer [20]. Photodynamic therapy consists of the use of combined therapeutic molecules, a photosensitizer drug and light. When combined, these two elements cause oxygen-mediated cellular and tissue damage. The photosensitizer is able to transfer the energy of light to oxygen for the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [21]. As reviewed by Saide et al. [19], PPBa has been shown to have multiple bioactivities: antitumor (against Burkitt lymphoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, uterine sarcoma, breast adenocarcinoma, oral squamous cell carcinoma, glioblastoma and melanoma [22]), antiviral, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiparasitic and immunostimulatory [19].

Considering the increase in infectious diseases and resistance to current antibiotics, we urgently need new solutions. Antibiotic resistance has become a plague that afflicts humanity and poses a huge threat to public health. The improper use of antibiotics has favored the development of resistance in pathogenic organisms [23]. In the literature, several resistance mechanisms have been identified and described, such as (1) decreased membrane permeability and increased efflux pumps, (2) modifications and adaptations of antibiotic receptors and (3) the synthesis of enzymes that inactivate or deactivate antibiotics [23,24,25]. For this reason, new compounds or new targets with antimicrobial activity are needed. Regarding PUAs and PPBa, to our knowledge, there is not much information in this field. In particular, PUAs have found application in agriculture thanks to their ability to inhibit the growth of plant pathogenic fungi. For example, three volatile aldehydes, octanal, nonanal and decanal, have been shown to have activity against the fungus Aspergillus flavus [26]. In addition, Bisignano’s group [27] tested eight different long-chain aliphatic aldehydes (hexanal, nonanal, (E)-2-hexenal, (E)-2-eptenal, (E)-2-octenal, (E)-2-nonenal, (E)-2-decenal and (E,E)-2,4-decadienal) against different bacterial strains that can be agents of infections: Haemophilus influenzae ATCC 9006, Moraxella catarrhalis ATCC 10541, Escherichia coli ATCC 10538, Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 7540, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538, Streptococcus pyogenes ATCC 12348, Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 7070, Salmonella enteritidis ATCC 6017, Salmonella typhi ATCC 7521, Bacillus cereus ATCC 10876 and Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 7646. In addition, they have used eighty-eight strains isolated from the upper respiratory tract in humans (H. influenzae, 12 strains; M. catarrhalis, 12 strains; S. pyogenes erythromycin S, 11 strains; S. pyogenes erythromycin R, 15 strains; S. pneumoniae, nine strains; S. aureus methicillin S, 18 strains; S. aureus methicillin R, 11 strains) and three strains isolated from contaminated food (toxin B-producing S. aureus, S. enteritidis, L. monocytogenes) to demonstrate that saturated and unsaturated aldehydes have good antimicrobial activity [27]. PPBa was used against the fungus Diaporthe mahothocarpus, showing an ability to inhibit mycelial growth and spore germination, demonstrating through electron microscopy that PPBa had the ability to inhibit hyphal growth. Transcriptomic analyses showed that PPBa had the ability to modify the expression of genes involved in membrane permeability and oxidative stress [28]. In a work by Stermitz et al. [29], it was demonstrated that PPBa had activity as an inhibitor of the efflux pumps of the pathogenic bacterium S. aureus, inhibiting the efflux of antibiotics that could compromise the antimicrobial activity [29]. In another study, light-activated PPBa was used on mice infected with S. aureus. Photodynamic therapy with PPBa was shown to have antimicrobial activity against S. aureus MRSA. It was also suggested that light-activated PPBa is able to inhibit P-glycoprotein which is a major class of efflux pump implicated in antibiotic resistance [30].

The aim of this study was to study two PUAs and PPBa for possible antibacterial and antifungal activities against human pathogens, particularly against the bacteria E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and S. aureus and the fungi Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Testing Reagents

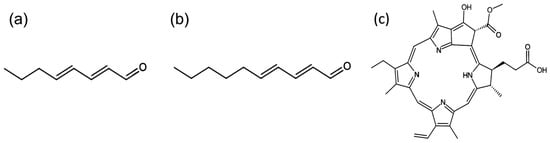

2,4-octadienal, predominantly trans,trans > 95%, FG Kosher was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, SAFC (St. Louis, MO, USA); trans,trans-2,4-decadienal, 85%, technical grade purchase from Sigma-Aldrich. Pheophorbide a was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(a) 2,4-octadienal; (b) trans,trans-2,4-decadienal; (c) pheophorbide a.

2.2. Antimicrobial Assays

2.2.1. Minimal Inhibitory Concentration Assay (MIC)

To test the possible activity against bacteria and fungi of PPBa and the two PUAs, samples were inserted in 96-well plates, and a two-fold serial broth microdilution method was used. Initial concentration was 1.25 mg/mL for PPBa and 0.25 mL/mL (corresponds to 0.219 mg/mL for 2,4-octadienal and 0.218 mg/mL for trans,trans-2,4-decadienal) for PUAs. Microorganisms were obtained from the Microbial Strain Collection of Latvia (MSCL), University of Latvia, MIRRI-ERIC Consortium. Five strains of microorganisms were used: Gram-negative bacteria E. coli MSCL 332 (ATCC 25922) and P. aeruginosa MSCL 331 (ATCC 9027), Gram-positive bacterium S. aureus MSCL 334 (ATCC 6538P), and fungi C. albicans MSCL 378 (ATCC 10261) and A. fumigatus MSCL 1323. Mueller-Hinton broth (Biolife, Italy) was used for cultivation of bacteria, and Malt extract broth (Millipore, Germany) was used for the cultivation of fungi. The inoculum of each microorganism was prepared in sterile water with a density of 0.09 ± 0.01 at A625 and diluted 100-fold in appropriate broth. Microorganism in culture medium was used as a positive control, and growth medium without microorganism was used as a negative control. Since one compound (PPBa) was dissolved in DMSO, a DMSO serial dilution was used as an appropriate control. MIC for DMSO was 12.5%. DMSO toxicity has been taken into account, and the activity was due to the molecules themselves, not DMSO. The reference antibiotics gentamicin (KRKA, Novo Mesto, Slovenia) and fluconazole (Diflucan, Pfizer Ltd., Kent, UK) were used as positive controls.

Because the compounds studied were highly volatile (2,4-octadienal and 2,4-decadienal), the wells of the 96-well plates were tightly covered with parafilm immediately after filling. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h for bacteria and 48 h for fungi. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of test material that showed no visible growth. Results are expressed as the median of three replicates.

2.2.2. Minimal Bactericidal/Fungicidal Concentration (MBC/MFC) Assay

From the wells where no microbial growth was detected, 4 μL of the liquid was plated on appropriate solidified bacterial or fungal medium to determine Minimal Bactericidal/Fungicidal Concentration (MBC/MFC). The MBC/MFC was defined as the lowest concentration of test material that prevents growth of the organism on the agar plate. Results are expressed as the median of three replicates.

3. Results

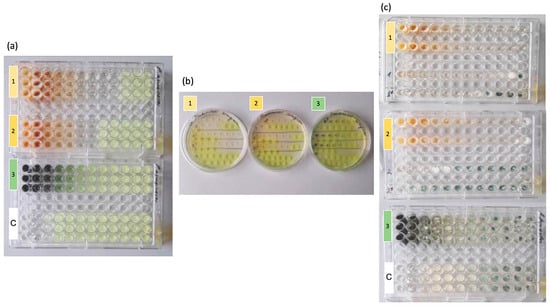

The antimicrobial activity of the three compounds was evaluated by comparing the MIC (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration) and MFC/MBC (Minimum Fungicidal/Bactericidal Concentration) values on a panel of five microorganisms: E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, C. albicans and A. fumigatus (Figure 2; Table 1). The 2,4-octadienal sample showed inhibitory activity against E. coli and S. aureus (MIC = 0.122 µL/mL) but was less effective against P. aeruginosa (MIC = 1.95 µL/mL). On the contrary, PPBa maintained a constant activity on E. coli and P. aeruginosa (MIC = 0.625 mg/mL). The MIC value for these samples also corresponded to the MBC value. The compound trans,trans-2,4-decadienal, although showing similar values to those of sample 2,4-octadienal against E. coli and S. aureus, was less effective against P. aeruginosa (MIC = 3.90 µL/mL). For this sample, the MBC values were double the MIC value for all bacteria. For pathogenic fungi, however, the 2,4-octadienal sample clearly stood out for its antifungal efficacy, with extremely low MIC values against C. albicans (0.031 µL/mL) and A. fumigatus (0.001 µL/mL). The trans,trans-2,4-decadienal sample showed an intermediate activity (MIC = 0.122 µL/mL for C. albicans and 0.244 µL/mL for A. fumigatus), while PPBa showed a less potent activity than the other two samples tested (MIC >0.313 mg/mL on both fungal strains). It should also be noted that the MFC value for the compound 2,4-octadienal is extremely low, 0.004 µL/mL, for the fungus A. fumigatus. The DMSO concentration tested in these experiments ranged from 25% to 0.01%. Figure 2 shows that the MIC for DMSO was 12.5% in the case of P. aeruginosa and A. fumigatus, and this did not affect the MIC of the test substances itself in the case of either these or the other microorganisms.

Figure 2.

(a) The 96-well plates with (1) 2,4-octadienal, (2) trans,trans-2,4-decadienal, (3) pheophorbide a and (C) DMSO control tested against P. aeruginosa. The concentration gradient tested was from 0.625 mg/mL to 0.0003 mg/mL for pheophorbide a and from 125 µL/mL to 0.061 µL/mL for 2,4-octadienal and 2,4-decadienal. It is shown that all three tested compounds stain the medium at high concentrations. P. aeruginosa growth manifests itself with a yellowish color; (b) determination of MBC of (1) 2,4-octadienal; (2) trans,trans-2,4-decadienal and (3) pheophorbide a against P. aeruginosa; (c) 96-well plates with (1) 2,4-octadienal, (2) trans,trans-2,4-decadienal, (3) pheophorbide a and (C) DMSO control tested against A. fumigatus. The concentration gradient tested was from 0.625 mg/mL to 0.0003 mg/mL for pheophorbide a and from 125 µL/mL to 0.0000015 µL/mL for 2,4-octadienal and 2,4-decadienal. Green mycelial growth is observed at the highest dilutions. The DMSO concentration tested in these experiments ranged from 25% to 0.01%.

Table 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal/fungicidal concentration (MBC/MFC) of samples. The results are expressed in µL/mL for sample 2,4-octadienal and trans,trans-2,4-decadienal, in mg/mL for pheophorbide a and in µg/mL for gentamicin and fluconazole. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of test material that showed no visible growth. The MBC/MFC was defined as the lowest concentration of test material that prevents growth of the organism on the agar plate after microdilution assay. ND stands for not determined.

4. Discussion

Considering the increasing number of emerging infectious diseases and antibiotic-resistant pathogens, there is an urgent need for new active compounds or improvements of the ones in use. Actually, microalgal-derived products available on the market are all applied to the cosmeceutical and nutraceutical sectors [31,32]. There are not microalgal compounds in use for pharmaceutical applications. However, in the past 20 years, several studies have shown that microalgae can produce potent marine natural products with bioactivities in vitro and in vivo for different diseases, from oxidative stress to inflammation and cancer [33], and researchers are trying to proceed with them further in pre-clinical trials.

The potential of microalgae as a source of novel drugs has recently generated great interest, especially because some of them have already received the GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe; [34]) status. Oxylipins have been shown to have anti-inflammatory [35], antimicrobial (against the terrestrial plant pathogens P. syringae, X. campestris and E. carotovora; [36]) and anticancer activities [15]. To our knowledge, there are no studies demonstrating oxylipin activities on the pathogenic microbes tested in the current paper (while antimicrobial activites are known for terrestrial plant oxylipins on plant pathogens).

Oxylipins are known to be intracellular mediators in eukaryotic cells but are poorly studied as mediators in prokaryotic cells. The relatively low activity of 2,4-octadienal and trans,trans-2,4-decadienal compounds in the pathogenic bacterium P. aeruginosa could be due to the presence of diol synthase that catalyzes the stereospecific oxygenation of oleic acid [37]. It was discovered by Martínez and his group that P. aeruginosa was capable of producing and detecting oxylipins from the surrounding environment. Indeed, several oxylipins such as (10S)-hydroxy-(8E)-octadecenoic acid (10-HOME) and 7S,10S-dihydroxy-(8E)-octadecenoic acid (7,10-DiHOME) produced by diol synthase were able to activate a new quorum sensing system called ODS (oxylipin-dependent quorum sensing system) through which the diol synthase is able to mediate cell–cell communication and activate several biological processes such as movement, biofilm formation and virulence in P. aeruginosa [38,39]. This is perfectly in line with the results obtained. The bacterium P. aeruginosa is the only one of the panel of pathogenic bacteria that is relatively resistant to the two PUAs used, and this could be explained by the fact that 2,4-octadienal is produced by P. aeruginosa [40] and the trans,trans-2,4-decadienal could be analogue of the oxylipins produced by the bacterium and that they would therefore favor the activation of quorum sensing with a consequent increase in vitality thanks to the formation of biofilm or other survival mechanisms. On the contrary, for E. coli and S. aureus, no activity related to the presence of oxylipins is reported in the literature; in fact, the results show that they are sensitive to these compounds. For Gram-positive bacteria such as S. aureus, it has been reported that unsaturated fatty acids have an antibiofilm activity and this activity is stronger on Gram-positive bacteria than on Gram-negative bacteria [41]. Regarding A. fumigatus, it is the most common cause of infections in humans [42] and is reported by the World Health Organization (WHO) in the fungal priority pathogens list, in particular, in the Critical Priority Group (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060241; accessed on 12 June 2025), established based on average case fatality rate, annual incidence, current global distribution, trends in the last 10 years, average length of hospital stay required for treatment following initial diagnosis antifungal resistance, complications and sequelae, antifungal resistance, preventability, access to diagnostic tests and evidence-based treatments [43]. Even if voriconazole and isavuconazole are known to be among the preferred drugs for the treatment of aspergillosis, resistance to azole has been reported, and new drugs have been suggested [44,45] and are in clinical trials, such as F901318 (FTG Ltd., Cheshire, United Kingdom), E1210 (Eisai Company, Tokyo, Japan), ASP2397 (Vical Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and Biafungin (CD101). For instance, the compound F901318 has a MIC ≤ 0.06 µg/mL [46], E1210 a MIC of 0.03 μg/mL [44] and ASP2397 a MIC range of 1 to 4 μg/mL [47], while CD101 demonstrated potent in vitro activity against A. fumigatus strain ATCC 13073 with a MEC value of 0.0078 µg/mL [48,49]. The most active compound in our study was 2,4-octadienal with a MIC of 0.001 µL/mL (corresponding to 0.0009 µg/mL).

A novel triazole antifungal, named PC1244, reported in pre-clinical studies, has shown potent in vitro activity against A. fumigatus, including some emerging azole-resistant strains. For susceptible clinical isolates, the MIC90 ranges from 0.016 to 0.25 µg/mL, significantly lower than the range of 0.25–0.5 µg/mL for voriconazole.

In multidrug-resistant strains (e.g., TR34/L98H, TR46/Y121F/T289A), PC1244 maintains clinically relevant activity with a geometric mean MIC of 1.0 mg/L compared to 15 mg/L for voriconazole, illustrating up to 15-fold greater potency. Even at high concentrations, the efficacy of PC1244 is preserved, suggesting that it has a broad therapeutic range. The low MIC makes PC1244 ideal for inhalation therapies due to the high and sustained lung concentration. Its activity remains unchanged against posaconazole-resistant Aspergillus spp. This MIC profile distinguishes it from conventional azoles. Therefore, PC1244 could provide a new therapeutic option for resistant aspergillosis [50].

5. Conclusions

In this work, 2,4-octadienal, trans,trans-2,4-decadienal and pheophorbide a were tested on five human pathogenic microorganisms: E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, C. albicans and A. fumigatus. These compounds were well known to have teratogenic effects on copepods and sea urchins, but they have not yet been fully explored as compounds with antimicrobial activity. We showed for the first time that the compound 2,4-octadienal showed significant antimicrobial activity, especially against the fungus A. fumigatus where the MIC value was 0.001 µL/mL and MFC value was 0.004 µL/mL. Further studies need to be carried out to clarify the mechanism of action and open the doors to a possible application of this compound. The current study gave the possibility to identify new interesting activities for oxylipins, give new insights on biotechnological applications of microalgae and open new research lines in microalgal compound applications for antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral and antiparasitic focus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L.; methodology, V.N.; formal analysis, V.N.; data curation, A.C., V.N. and C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C., V.N. and C.L.; writing—review and editing, A.C., V.N. and C.L.; supervision, C.L.; project administration, V.N. and C.L.; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 871129.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Some images of the graphical abstract were provided by/adapted from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com/; accessed on 16 October 2025), licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/; accessed on 16 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hu, Q.; Sommerfeld, M.; Jarvis, E.; Ghirardi, M.; Posewitz, M.; Seibert, M.; Darzins, A. Microalgal Triacylglycerols as Feedstocks for Biofuel Production: Perspectives and Advances. Plant J. 2008, 54, 621–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, K.; Suresh, K.; Anbalagan, S.; Ragini, Y.P.; Kadirvel, V. Investigating the Nutritional Viability of Marine-Derived Protein for Sustainable Future Development. Food Chem. 2024, 448, 139087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.; Geada, P.; Pereira, R.N.; Teixeira, J.A. Microalgae Biomass–A Source of Sustainable Dietary Bioactive Compounds towards Improved Health and Well-Being. Food Chem. Adv. 2025, 6, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralto, A.; Barone, G.; Romano, G.; Poulet, S.A.; Ianora, A.; Russo, G.L.; Buttino, I.; Mazzarella, G.; Laabir, M.; Cabrini, M.; et al. The Insidious Effect of Diatoms on Copepod Reproduction. Nature 1999, 402, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarno, D.; Kooistra, W.H.C.F.; Medlin, L.K.; Percopo, I.; Zingone, A. Diversity in The Genus Skeletonema (Bacillariophyceae). Ii. An Assessment of The Taxonomy of S. costatum-Like Species with The Description of Four New Species. J. Phycol. 2005, 41, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritano, C.; Romano, G.; Roncalli, V.; Amoresano, A.; Fontanarosa, C.; Bastianini, M.; Braga, F.; Carotenuto, Y.; Ianora, A. New Oxylipins Produced at the End of a Diatom Bloom and Their Effects on Copepod Reproductive Success and Gene Expression Levels. Harmful Algae 2016, 55, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianora, A.; Miralto, A.; Poulet, S.A.; Carotenuto, Y.; Buttino, I.; Romano, G.; Casotti, R.; Pohnert, G.; Wichard, T.; Colucci-D’Amato, L.; et al. Aldehyde Suppression of Copepod Recruitment in Blooms of a Ubiquitous Planktonic Diatom. Nature 2004, 429, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, I.; Ercolesi, E.; Romano, G.; Ianora, A.; Palumbo, A. The Diatom-Derived Aldehyde Decadienal Affects Life Cycle Transition in the Ascidian Ciona intestinalis through Nitric Oxide/ERK Signalling. Open Biol. 2015, 5, 140182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A.; d’Ippolito, G.; Cutignano, A.; Miralto, A.; Ianora, A.; Romano, G.; Cimino, G. Chemistry of Oxylipin Pathways in Marine Diatoms. Pure Appl. Chem. 2007, 79, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohnert, G. Diatom/Copepod Interactions in Plankton: The Indirect Chemical Defense of Unicellular Algae. ChemBioChem 2005, 6, 946–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, G.S. The Influence of Bioactive Oxylipins from Marine Diatoms on Invertebrate Reproduction and Development. Mar. Drugs 2009, 7, 367–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrone, V.; Piscopo, M.; Romano, G.; Ianora, A.; Palumbo, A.; Costantini, M. Defensome against Toxic Diatom Aldehydes in the Sea Urchin Paracentrotus lividus. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lettieri, A.; Esposito, R.; Ianora, A.; Spagnuolo, A. Ciona Intestinalis as a Marine Model System to Study Some Key Developmental Genes Targeted by the Diatom-Derived Aldehyde Decadienal. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 1451–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauritano, C.; Carotenuto, Y.; Vitiello, V.; Buttino, I.; Romano, G.; Hwang, J.-S.; Ianora, A. Effects of the Oxylipin-Producing Diatom Skeletonema marinoi on Gene Expression Levels of the Calanoid Copepod Calanus sinicus. Mar. Genom. 2015, 24, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, C.; Braca, A.; Ercolesi, E.; Romano, G.; Palumbo, A.; Casotti, R.; Francone, M.; Ianora, A. Diatom-Derived Polyunsaturated Aldehydes Activate Cell Death in Human Cancer Cell Lines but Not Normal Cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, C.A.; Bentley, M.G.; Caldwell, G.S. 2,4-Decadienal: Exploring a Novel Approach for the Control of Polychaete Pests on Cultured Abalone. Aquaculture 2010, 310, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribalet, F.; Intertaglia, L.; Lebaron, P.; Casotti, R. Differential Effect of Three Polyunsaturated Aldehydes on Marine Bacterial Isolates. Aquat. Toxicol. 2008, 86, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, K.; Shimoda, Y.; Tanaka, A.; Ito, H. Chlorophyll a Is a Favorable Substrate for Chlamydomonas Mg-Dechelatase Encoded by STAY-GREEN. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 109, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saide, A.; Lauritano, C.; Ianora, A. Pheophorbide a: State of the Art. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuitmaker, J.J.; Baas, P.; Van Leengoed, H.L.L.M.; Van Der Meulen, F.W.; Star, W.M.; Van Zandwijk, N. Photodynamic Therapy: A Promising New Modality for the Treatment of Cancer. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 1996, 34, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, S.; Knap, B.; Przystupski, D.; Saczko, J.; Kędzierska, E.; Knap-Czop, K.; Kotlińska, J.; Michel, O.; Kotowski, K.; Kulbacka, J. Photodynamic Therapy—Mechanisms, Photosensitizers and Combinations. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 106, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saide, A.; Riccio, G.; Ianora, A.; Lauritano, C. The Diatom Cylindrotheca Closterium and the Chlorophyll Breakdown Product Pheophorbide a for Photodynamic Therapy Applications. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cai, H.; Xu, B.; Dong, Q.; Jia, K.; Lin, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Qin, X. Prevalence, Antibiotic Resistance, Resistance and Virulence Determinants of Campylobacter jejuni in China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. One Health 2025, 20, 100990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, J.M.A.; Webber, M.A.; Baylay, A.J.; Ogbolu, D.O.; Piddock, L.J.V. Molecular Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, E.; Kaur, P. Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms in Bacteria: Relationships Between Resistance Determinants of Antibiotic Producers, Environmental Bacteria, and Clinical Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhu, X.; Xie, Y.; Liang, J. Antifungal Properties and Mechanisms of Three Volatile Aldehydes (Octanal, Nonanal and Decanal) on Aspergillus flavus. Grain Oil Sci. Technol. 2021, 4, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisignano, G.; LaganÃ, M.G.; Trombetta, D.; Arena, S.; Nostro, A.; Uccella, N.; Mazzanti, G.; Saija, A. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity of Some Aliphatic Aldehydes from Olea europaea L. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001, 198, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.-L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, P.; Zhou, H.-Y.; Chen, Y.-Z. The Photoactivated Antifungal Activity and Possible Mode of Action of Sodium Pheophorbide a on Diaporthe mahothocarpus Causing Leaf Spot Blight in Camellia oleifera. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1403478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stermitz, F.R.; Tawara-Matsuda, J.; Lorenz, P.; Mueller, P.; Zenewicz, L.; Lewis, K. 5‘-Methoxyhydnocarpin-D and Pheophorbide A: Berberis Species Components That Potentiate Berberine Growth Inhibition of Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1146–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, B.C.L.; Dharmaratne, P.; Wang, B.; Lau, K.M.; Lee, C.C.; Cheung, D.W.S.; Chan, J.Y.W.; Yue, G.G.L.; Lau, C.B.S.; Wong, C.K.; et al. Hypericin and Pheophorbide a Mediated Photodynamic Therapy Fighting MRSA Wound Infections: A Translational Study from In Vitro to In Vivo. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchkova, T.V.; Khapchaeva, S.A.; Zotov, V.S.; Lukyanov, A.A.; Solovchenko, A.E. Marine and freshwater microalgae as a sustainable source of cosmeceuticals. Mar. Biol. J. 2021, 6, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Sharma, A.; Bala, S.; Satheesh, N.; Nile, A.S.; Nile, S.H. Microalgae in the Food-Health Nexus: Exploring Species Diversity, High-Value Bioproducts, Health Benefits, and Sustainable Market Potential. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 427, 132424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saide, A.; Martínez, K.A.; Ianora, A.; Lauritano, C. Unlocking the Health Potential of Microalgae as Sustainable Sources of Bioactive Compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdock, G.A.; Carabin, I.G. Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS): History and Description. Toxicol. Lett. 2004, 150, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Reyes, C.; Ávila-Román, J.; Ortega, M.J.; De La Jara, A.; García-Mauriño, S.; Motilva, V.; Zubía, E. Oxylipins from the Microalgae Chlamydomonas debaryana and Nannochloropsis gaditana and Their Activity as TNF-α Inhibitors. Phytochemistry 2014, 102, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prost, I.; Dhondt, S.; Rothe, G.; Vicente, J.; Rodriguez, M.J.; Kift, N.; Carbonne, F.; Griffiths, G.; Esquerré-Tugayé, M.-T.; Rosahl, S.; et al. Evaluation of the Antimicrobial Activities of Plant Oxylipins Supports Their Involvement in Defense against Pathogens. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 1902–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, E.; Hamberg, M.; Busquets, M.; Díaz, P.; Manresa, A.; Oliw, E.H. Biochemical Characterization of the Oxygenation of Unsaturated Fatty Acids by the Dioxygenase and Hydroperoxide Isomerase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa 42A2. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 9339–9345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, E.; Cosnahan, R.K.; Wu, M.; Gadila, S.K.; Quick, E.B.; Mobley, J.A.; Campos-Gómez, J. Oxylipins Mediate Cell-to-Cell Communication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, E.; Campos-Gómez, J. Oxylipins Produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa Promote Biofilm Formation and Virulence. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, H.D.; Rees, C.A.; Hill, J.E. Comparative Analysis of the Volatile Metabolomes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clinical Isolates. J. Breath. Res. 2016, 10, 047102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuyama, K.T.; Rohde, M.; Molinari, G.; Stadler, M.; Abraham, W.-R. Unsaturated Fatty Acids Control Biofilm Formation of Staphylococcus aureus and Other Gram-Positive Bacteria. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenks, J.D.; Hoenigl, M. Treatment of Aspergillosis. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Fungal Priority Pathogens List to Guide Research, Development and Public Health Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- Hata, K.; Horii, T.; Miyazaki, M.; Watanabe, N.; Okubo, M.; Sonoda, J.; Nakamoto, K.; Tanaka, K.; Shirotori, S.; Murai, N.; et al. Efficacy of Oral E1210, a New Broad-Spectrum Antifungal with a Novel Mechanism of Action, in Murine Models of Candidiasis, Aspergillosis, and Fusariosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 4543–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.W.; Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Cornely, O.A.; Perfect, J.R.; Walsh, T.J. Novel Agents and Drug Targets to Meet the Challenges of Resistant Fungi. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216, S474–S483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, J.B.; Rijs, A.J.M.M.; Meis, J.F.; Birch, M.; Law, D.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Verweij, P.E. In Vitro Activity of the Novel Antifungal Compound F901318 against Difficult-to-Treat Aspergillus Isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 2548–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, I.; Ohsumi, K.; Takeda, S.; Katsumata, K.; Matsumoto, S.; Akamatsu, S.; Mitori, H.; Nakai, T. ASP2397 Is a Novel Natural Compound That Exhibits Rapid and Potent Fungicidal Activity against Aspergillus Species through a Specific Transporter. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e02689-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, V.; Hough, G.; Schlosser, M.; Bartizal, K.; Balkovec, J.M.; James, K.D.; Krishnan, B.R. Preclinical Evaluation of the Stability, Safety, and Efficacy of CD101, a Novel Echinocandin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 6872–6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, V.; Bartizal, K.; Miesel, L.; Huang, H.H.; You, W.T.; Miesel, L. Efficacy of CD101, a Novel Echinocandin Antifungal, in a Mouse Model of Disseminated Aspergillosis. In Proceedings of the 7th Advances Against Aspergillosis Conference, Manchester, UK, 3–5 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Colley, T.; Sharma, C.; Alanio, A.; Kimura, G.; Daly, L.; Nakaoki, T.; Nishimoto, Y.; Bretagne, S.; Kizawa, Y.; Strong, P.; et al. Anti-Fungal Activity of a Novel Triazole, PC1244, against Emerging Azole-Resistant Aspergillus fumigatus and Other Species of Aspergillus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 2950–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).