Research on STA/LTA Microseismic Arrival Time-Picking Method Based on Variational Mode Decomposition

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. STA/LTA Method

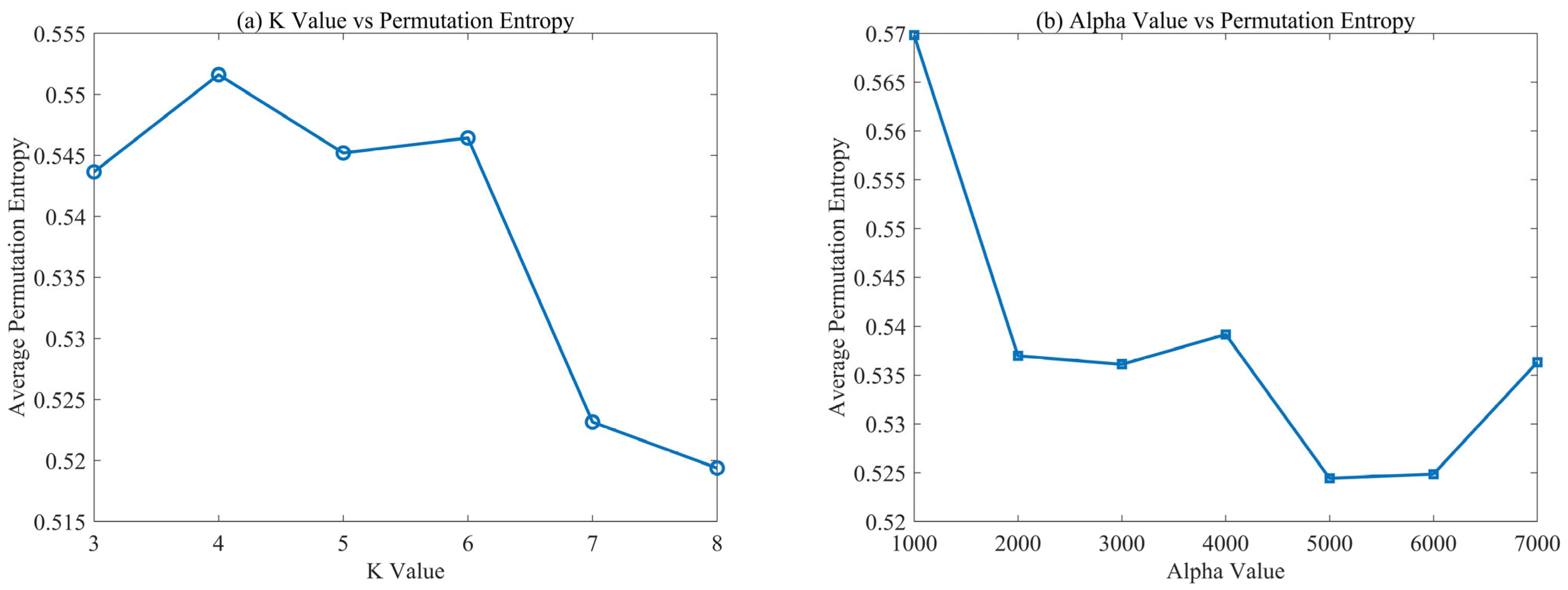

2.2. VMD Method

2.3. The Proposed Method

- (1)

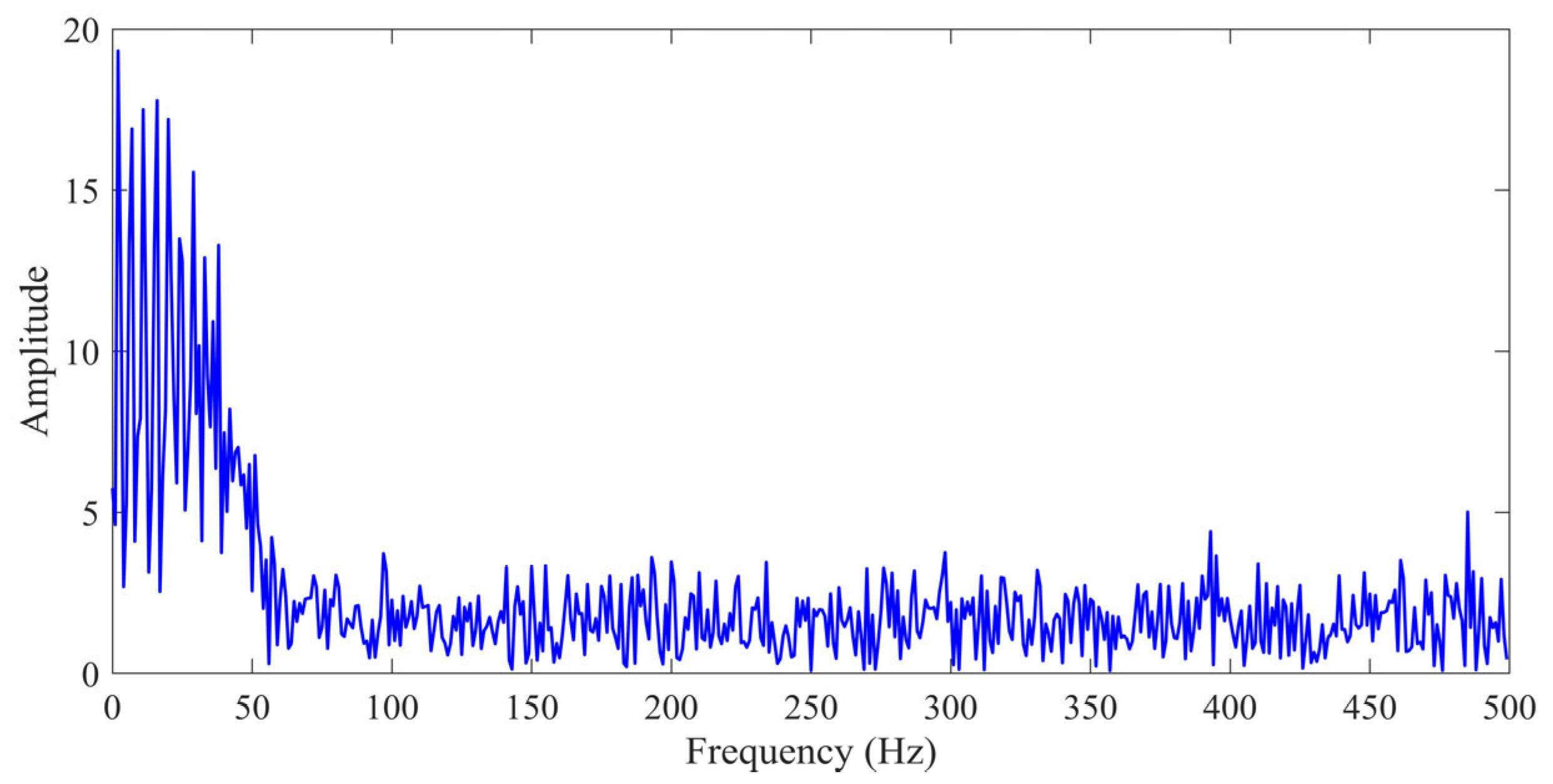

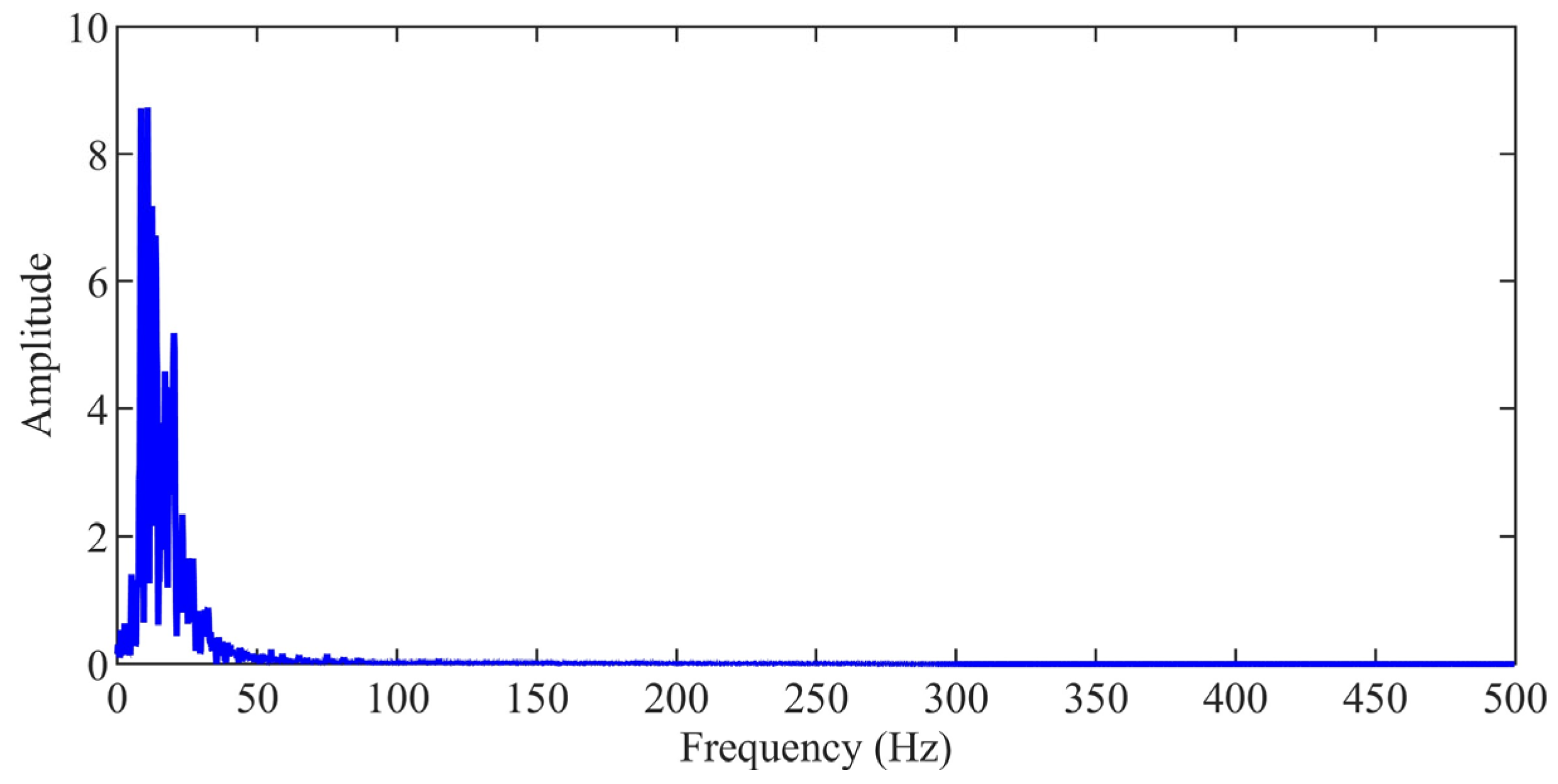

- In order to investigate the dominant frequency distribution characteristics, the frequency spectrum of the microseismic signal is obtained through FFT. The equation can be expressed as

- (2)

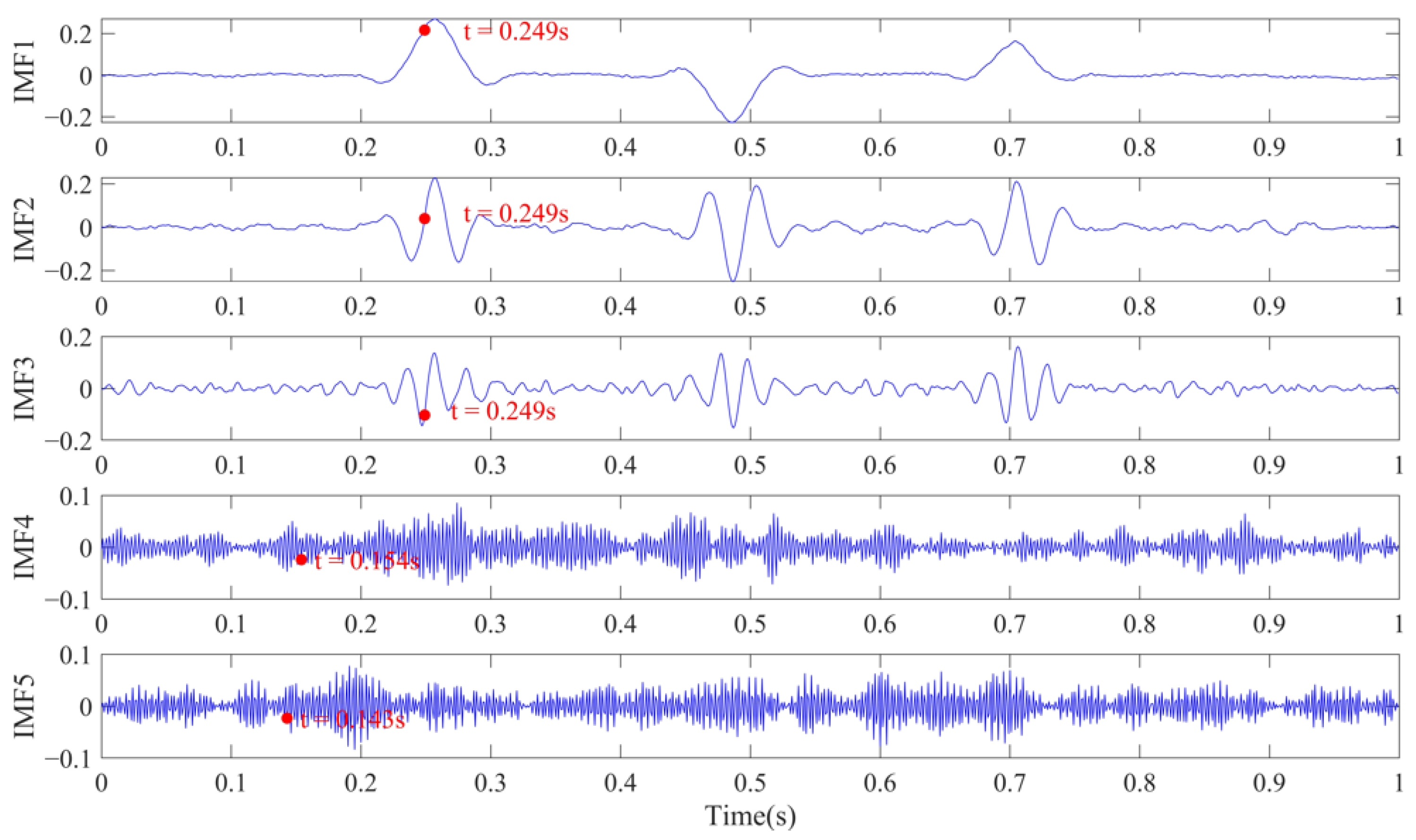

- is decomposed into several mode signals, and a residual term through VMD. Each mode signal represents different frequency components.

- (3)

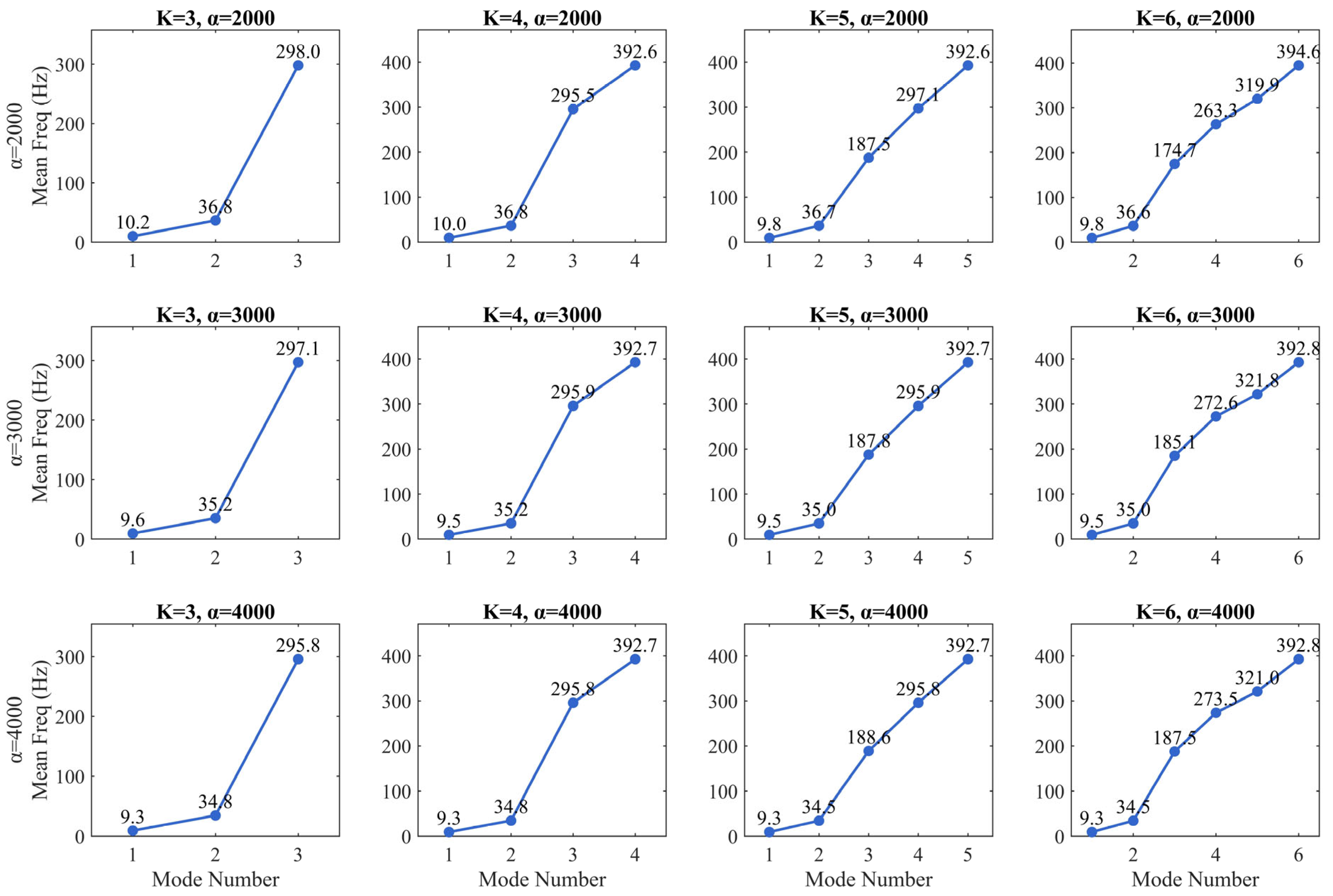

- For selecting the effective modal components according to the frequency distribution of a microseismic signal, we need to calculate the center frequencies of each IMF. This helps differentiate effective signals from noise. Assuming is the frequency spectrum of , the center frequency can be calculated using the following equation:

- (4)

- The proposed method establishes the mean value of IMFs’ center frequencies as the selection criterion, classifying modal components with sub-average center frequencies as the effective signal-bearing elements. STA/LTA is implemented on the selected IMFs to pick arrival time. The STA and LTA are then computed as follows:

- (5)

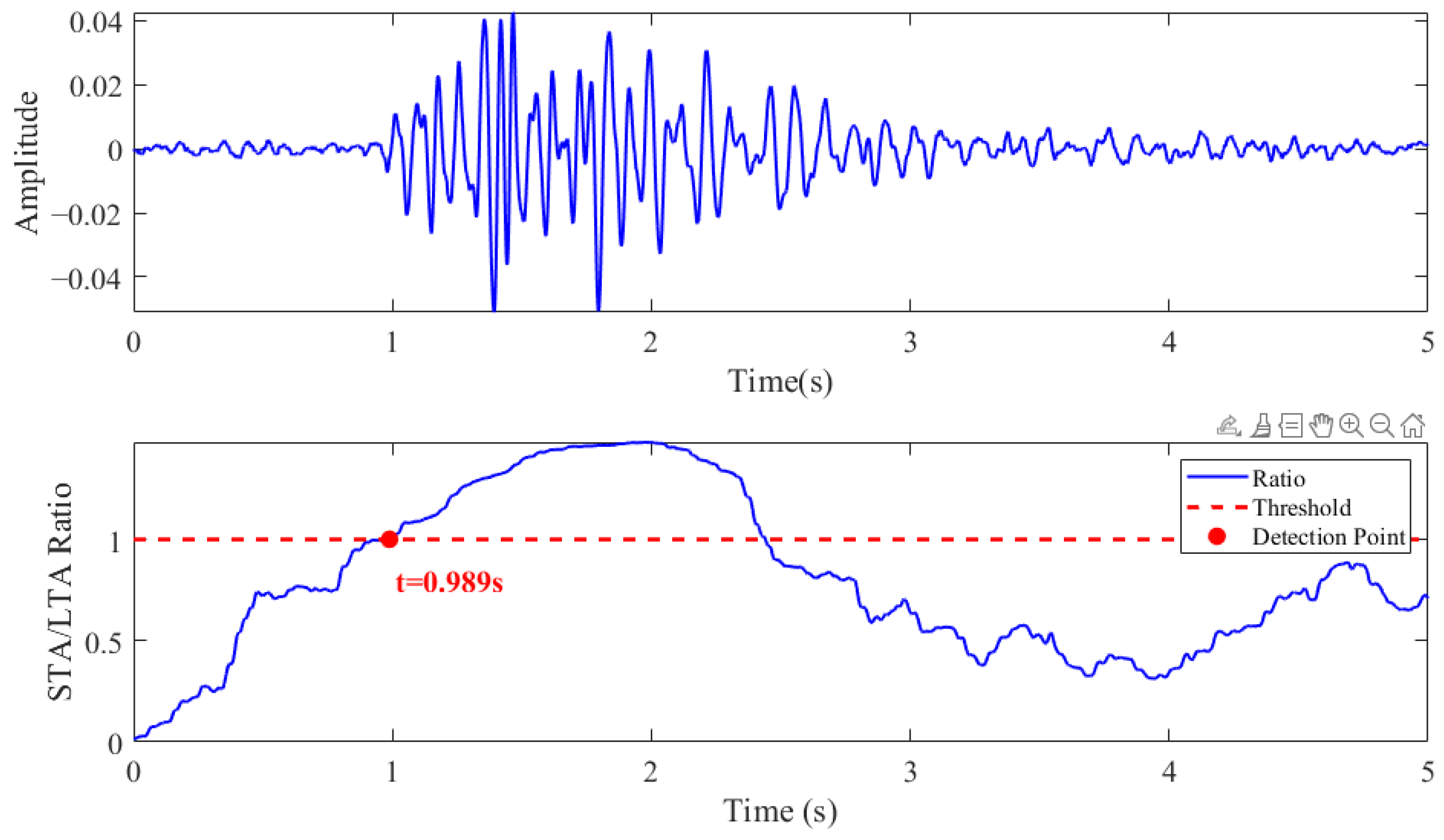

- We calculate the ratio of STA to LTA and manually set a threshold, , to determine whether a microseismic event has occurred.

- (6)

- To fuse the arrival time-picking results from the selected IMFs, an adaptive energy-weighted approach is employed that requires computing the energy value of each selected IMF component as follows:

- (7)

- The final arrival time is obtained by computing the weighted fusion of the arrival picks from the selected components using their corresponding weighting coefficients.

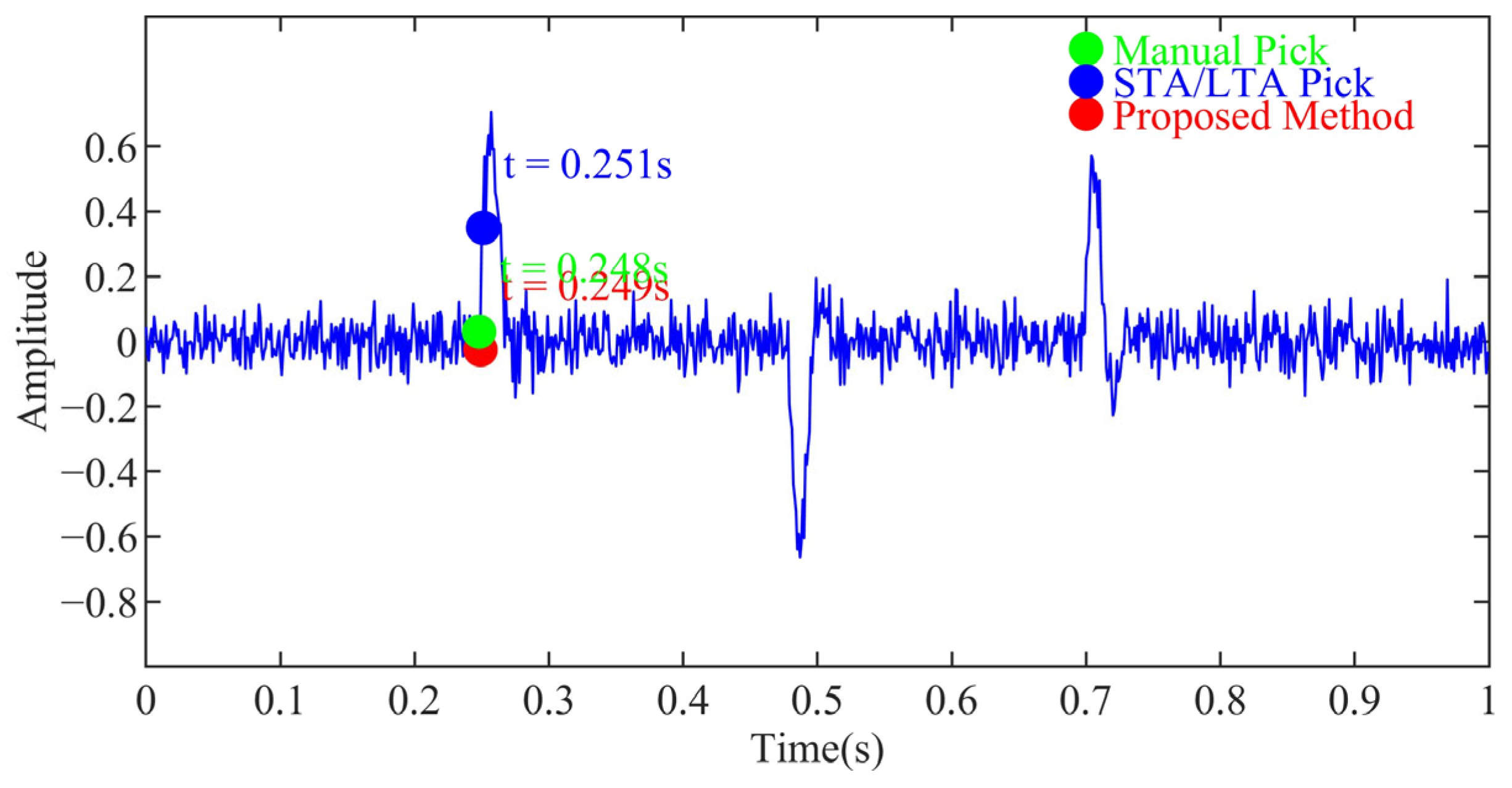

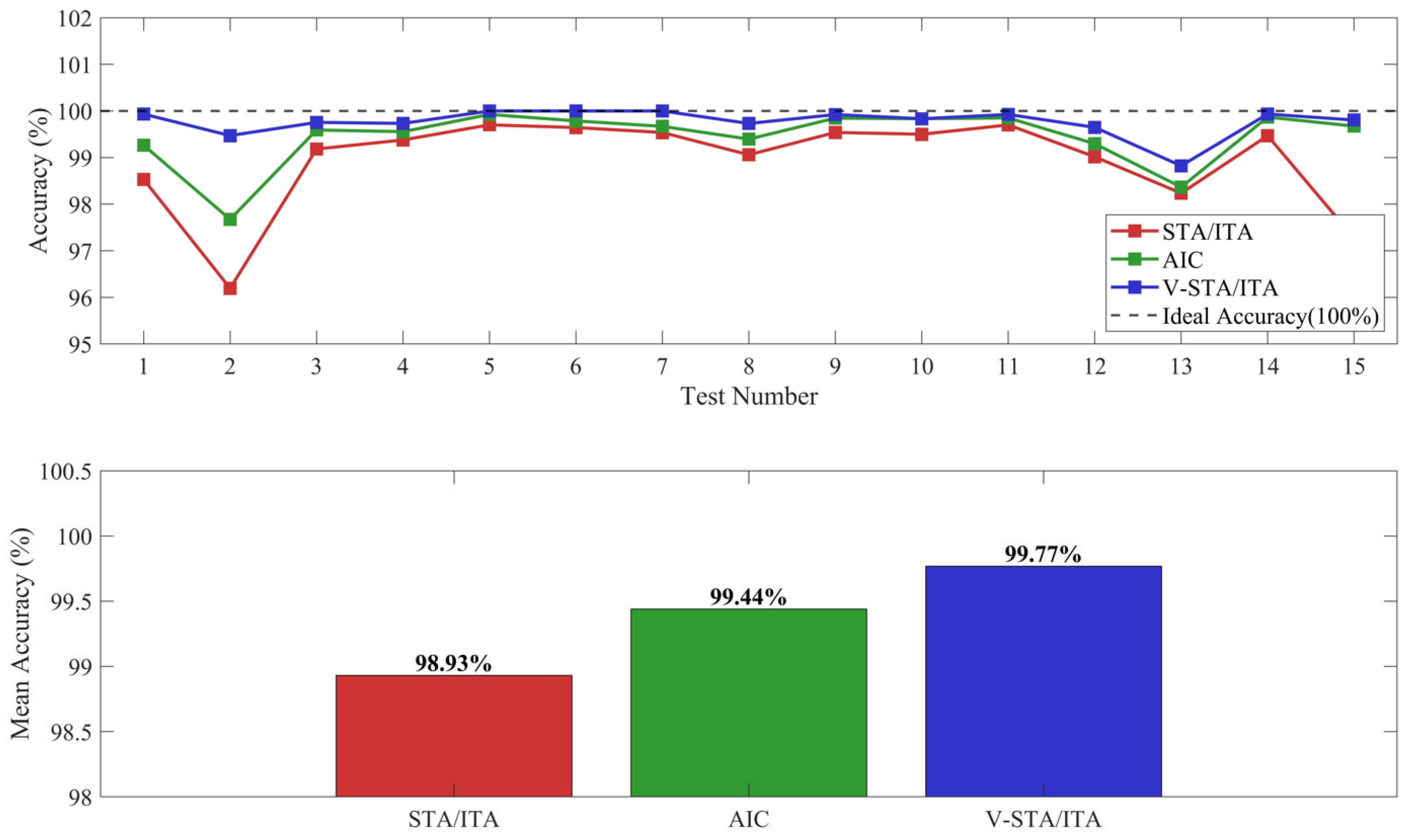

3. Simulation Experiment

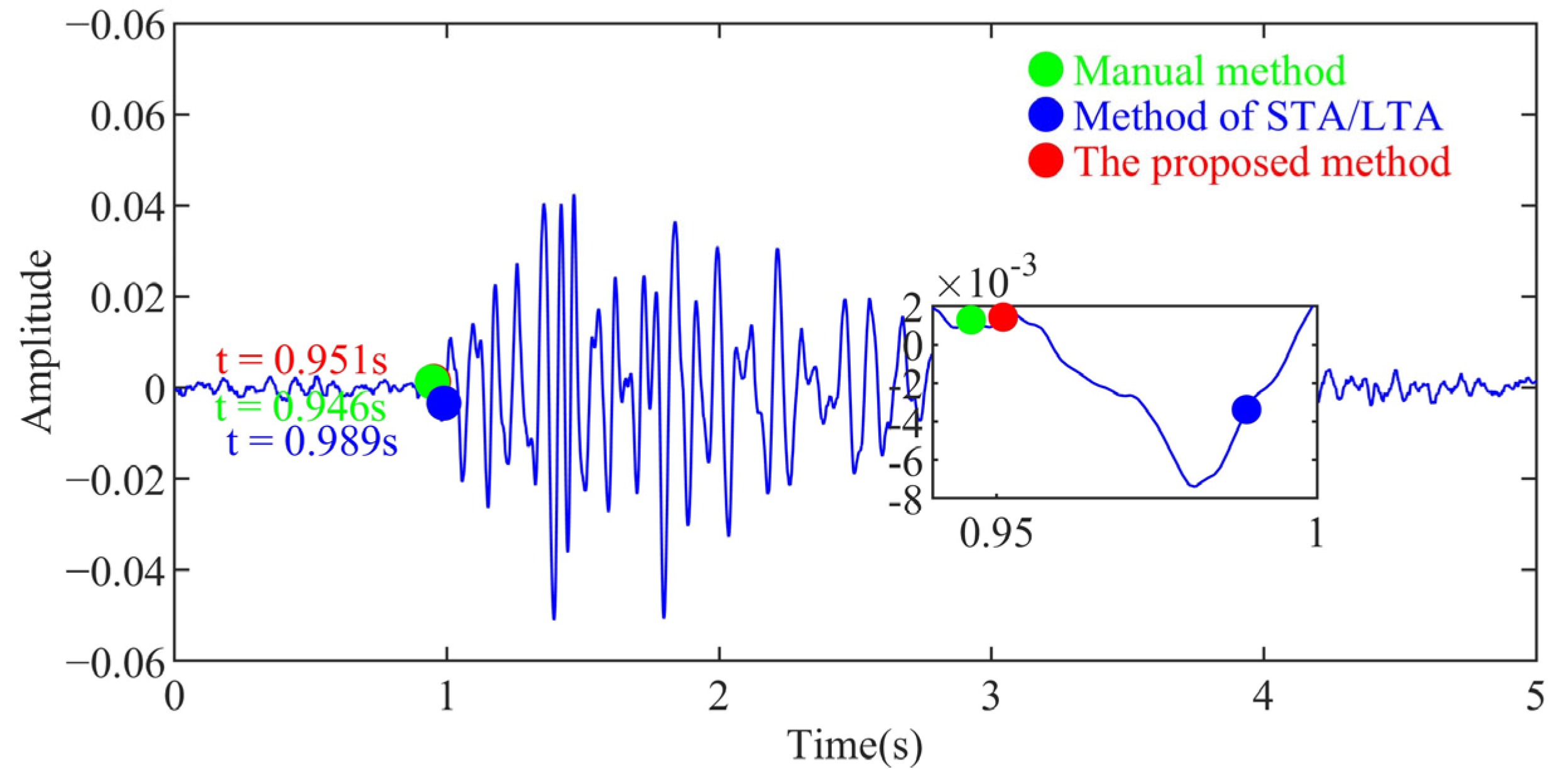

4. Field Data Examples

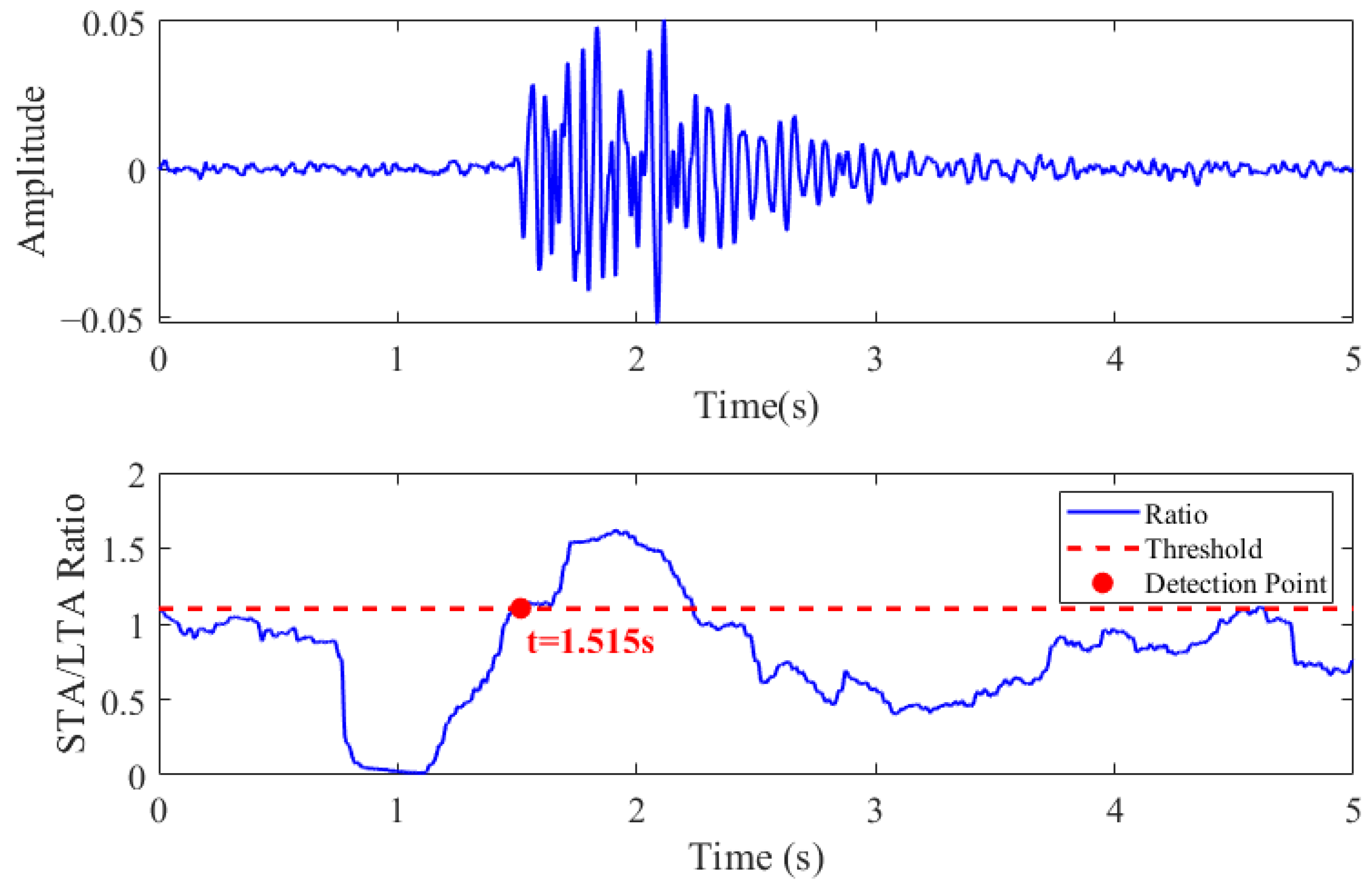

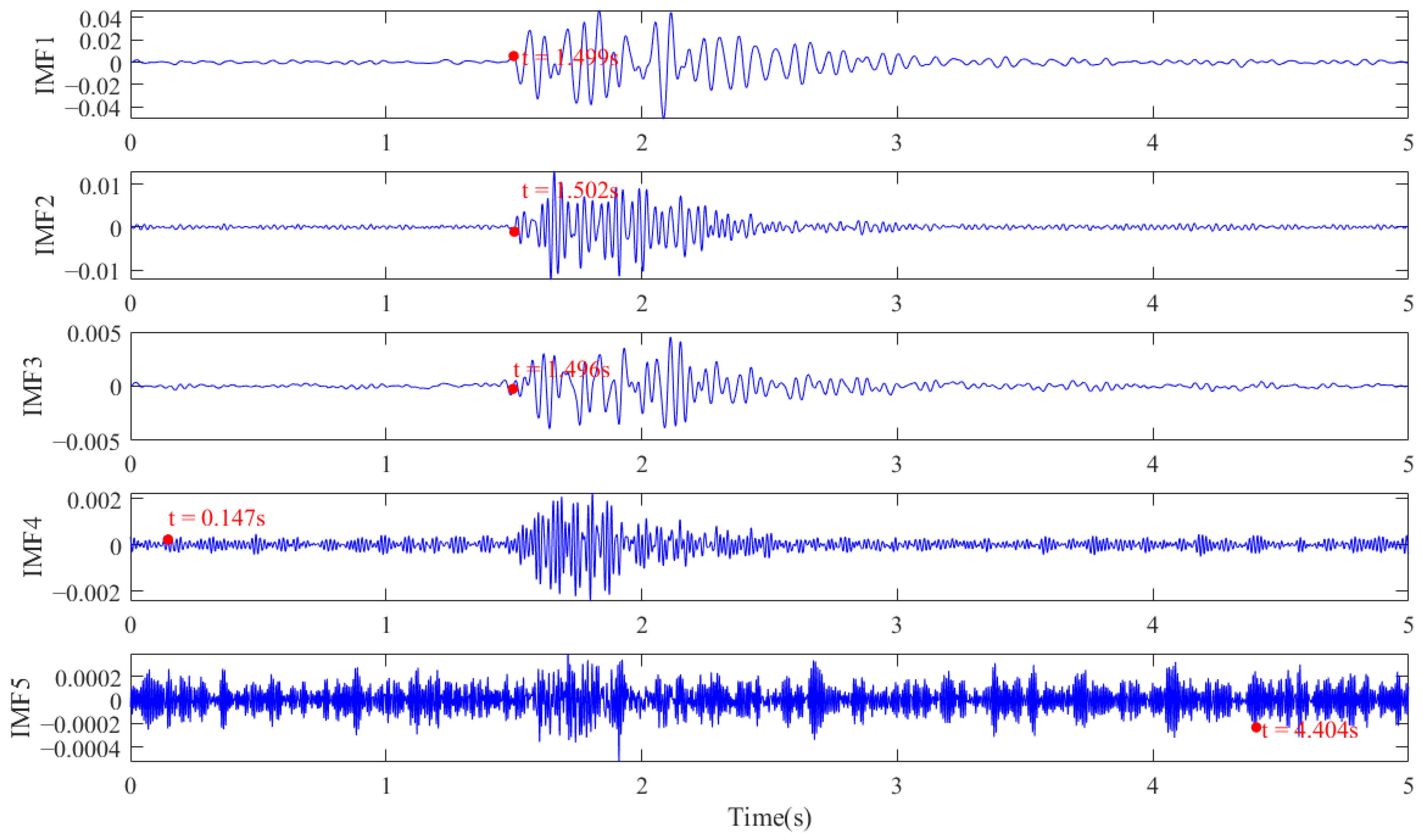

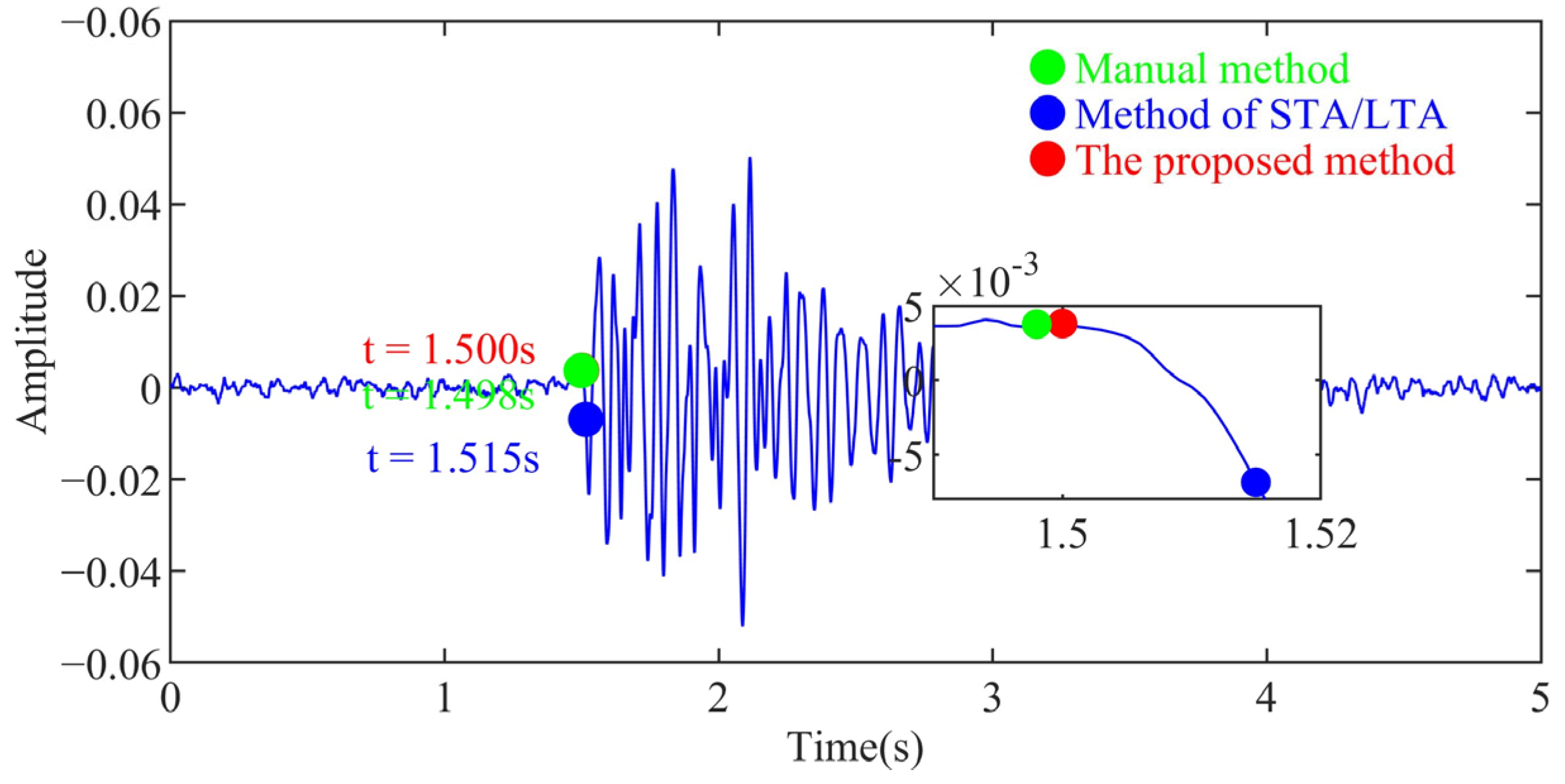

4.1. Instances 1

4.2. Instances 2

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ranjith, P.G.; Zhao, J.; Ju, M.H.; De Silva, R.V.; Rathnaweera, T.D.; Bandara, A.K. Opportunities and challenges in deep mining: A brief review. Engineering 2017, 3, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamriew, D.; Dorhjie, D.B.; Bogoedov, D.; Pevzner, R.; Maltsev, E.; Charara, M.; Pissarenko, D.; Koroteev, D. Microseismic Monitoring and Analysis Using Cutting-Edge Technology: A Key Enabler for Reservoir Characterization. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtecki, Ł.; Mendecki, M.J.; Zuberek, W.M.; Knopik, M. An attempt to determine the seismic moment tensor of tremors induced by destress blasting in a coal seam. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2016, 83, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, Y.; Kou, M.; Liang, C. Applications of Microseismic Monitoring Technique in Coal Mines: A State-of-the-Art Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, M.; Ge, M. Enhancing manual P-phase arrival detection and automatic onset time picking in a noisy microseismic data in underground mines. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2018, 28, 691–699. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D.; Liu, K.; He, X. Topographic effects of the cliff at Majiishan Grottoes based on microseismic monitorin. China Earthq. Eng. J. 2025, 47, 979–990. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y. Study on the Method of Arrival Automatic Pickup of Microseismic P-wave Phase. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University of Science and Technology, Qingdao, China, 2018. Volume 37. pp. 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, D. Development of software for analyzing anchorage parameters of anchor rods based on wavelet transform and STA/LTA. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2025, 25, 1850–1855. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.; Li, L.; Cheng, S. Time-arrival pickup method of tunnel water inrush microseismic signals based on kurtosis value and AIC method. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 154, 106135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.V. Automatic earthquake recognition and timing from single traces. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 1978, 68, 1521–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayad, A.; Tarik, T. Lithostratigraphic and seismic investigation of the weathered zone in the exploration of deep petroleum structures (Boujdour area, Morocco). Egypt. J. Pet. 2024, 33, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-C.; Cheng, S.; Li, L.-P.; Shi, S.-S.; Zhang, M.-G. Identification and Location Method of Microseismic Event Based on Improved STA/LTA Algorithm and Four-Cell-Square-Array in Plane Algorithm. Int. J. Geomech. 2019, 19, 04019067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Stewart, R.R. A multi-window algorithm for real-time automatic detection and picking of P-phases of microseismic events. CSPG Natl. Conv. Abstr. 2006, 18, 335–358. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, J. Automatic P-wave Arrival Time Picking Method for Seismic and Microseismic Data [Conference Abstract]. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Geophysical Exploration, Calgary, AB, Canada, 9–11 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. Automatic Picking of Microseismic Events P-wave Arrivals Based on Improved Method of STA/LTA. J. Northeast. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2017, 38, 740–745. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. Automatic P-Wave Arrival Detection and Picking with Multiscale Wavelet Analysis for Single-Component Recordings. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2005, 93, 1904–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Z. Automatic signal detection based on support vector machine. Earthq. Sci. 2007, 20, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. An automatic seismic signal detection method based on fourth-order statistics and applications. Appl. Geophys. 2014, 11, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X. Enhancing micro-seismic P-phase arrival picking: EMD-cosine function-based denoising with an application to the AIC picker. J. Appl. Geophys. 2018, 150, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Xie, J.; Zu, S.; Gan, S.; Chen, Y. Multiple-Reflection Noise Attenuation Using Adaptive Randomized-Order Empirical Mode Decomposition. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2017, 14, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yang, J.; Cao, Y.; Fu, W.; Cao, Y. A new method for arrival time determination of impact signal based on HHT and AIC. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2017, 86, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shang, X.; Morales-Esteban, A.; Wang, Z. Identifying P phase arrival of weak events: The Akaike Information Criterion picking application based on the Empirical Mode Decomposition. Comput. Geosci. 2017, 100, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. The Filtering Algorithm for Rock Fracture Signal Based on Improved VMD. Noise Vib. Control 2023, 43, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Dragomiretskiy, K.; Zosso, D. Variational Mode Decomposition. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2014, 62, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incremona, A.; Nicolao, D.G. Spectral Characterization of the Multi-Seasonal Component of the Italian Electric Load: A LASSO-FFT Approach. IEEE Control Syst. Lett. 2020, 4, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Wu, S.; Wang, J. Methods of P-onset picking of acoustic emission compression waves and optimized improvement. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2016, 35, 1754–1766. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Q.; Cai, H. STA/LTA method for picking up the first arrival of natural seismic waves and its improvement analysis. Prog. Geophys. 2023, 38, 1497–1506. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, B.; Han, D. Multi-channel Short-Term Power Load Prediction Model Based on VMD Data Decomposition. Fluid Meas. Control 2024, 5, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, G. Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Crane Rolling Bearings Based on RMS Trend Consistency. Port Oper. 2024, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Ma, H.; Zhang, Y. Remaining useful life prediction method of lithium-ion batteries is based on variational modal decomposition and deep learning integrated approach. Energy 2023, 282, 128984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, H. Application Research on Random Noise Removal Method of Micro-Seismic Data Based on VMD-TFPF. Met. Mine 2022, 12, 170–176. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Chang, X.; Wang, X.; Du, W.; Duan, N.; Dang, C. Gearbox fault diagnosis based on permutation entropy optimized variational mode decomposition. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2018, 34, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Yan, K.; Lei, W.; Xue, Y. Lost circulation detection method through transient pressure wave based on STA/LTA analysis. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 240, 213082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SNR (dB) | Manual Picking Result (s) | STA/LTA Picking Results (s) | Absolute Error of STA/LTA (s) | AIC Picking Result (s) | Absolute Error of AIC (s) | V-STA/LTA Picking Result (s) | Absolute Error of V-STA/LTA (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.248 | 0.253 | 0.005 | 0.251 | 0.003 | 0.2484 | 0.0004 |

| 5 | 0.251 | 0.003 | 0.250 | 0.002 | 0.249 | 0.001 | |

| 10 | 0.252 | 0.004 | 0.247 | 0.001 | 0.2488 | 0.0008 | |

| 15 | 0.250 | 0.002 | 0.248 | 0 | 0.248 | 0 | |

| Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | 0.0015 | 0.0011 | 0.0005 | ||||

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | 0.0035 | 0.0015 | 0.00055 | ||||

| Standard Deviation (SD) | 0.0013 | 0.0012 | 0.0004 | ||||

| Method | Manual (s) | STA/LTA (s) | AIC (s) | V-STA/LTA (s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | |||||||

| 1 | 1.498 | 1.515 | 1.487 | 1.500 | |||

| 2 | 0.946 | 0.989 | 0.968 | 0.951 | |||

| 3 | 1.225 | 1.235 | 1.230 | 1.228 | |||

| 4 | 1.125 | 1.132 | 1.12 | 1.128 | |||

| 5 | 1.344 | 1.348 | 1.345 | 1.344 | |||

| 6 | 1.405 | 1.410 | 1.408 | 1.405 | |||

| 7 | 1.514 | 1.521 | 1.519 | 1.514 | |||

| 8 | 1.490 | 1.504 | 1.499 | 1.494 | |||

| 9 | 1.302 | 1.308 | 1.304 | 1.303 | |||

| 10 | 1.201 | 1.207 | 1.203 | 1.199 | |||

| 11 | 1.339 | 1.343 | 1.341 | 1.340 | |||

| 12 | 1.424 | 1.438 | 1.434 | 1.429 | |||

| 13 | 1.53 | 1.557 | 1.555 | 1.548 | |||

| 14 | 1.509 | 1.517 | 1.511 | 1.508 | |||

| 15 | 1.540 | 1.582 | 1.545 | 1.543 | |||

| Mean error | 0.0121 | 0.0087 | 0.0021 | ||||

| Mean absolute error (MAE) | 0.0153 | 0.0115 | 0.0050 | ||||

| Root mean square error (RMSE) | 0.0192 | 0.0143 | 0.0063 | ||||

| Standard deviation (SD) | 0.0198 | 0.0147 | 0.0065 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, Z.; Cheng, H.; Wang, X.; Luo, C. Research on STA/LTA Microseismic Arrival Time-Picking Method Based on Variational Mode Decomposition. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13220. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413220

Fang Z, Cheng H, Wang X, Luo C. Research on STA/LTA Microseismic Arrival Time-Picking Method Based on Variational Mode Decomposition. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13220. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413220

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Zhiyong, Hao Cheng, Xiannan Wang, and Chenghao Luo. 2025. "Research on STA/LTA Microseismic Arrival Time-Picking Method Based on Variational Mode Decomposition" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13220. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413220

APA StyleFang, Z., Cheng, H., Wang, X., & Luo, C. (2025). Research on STA/LTA Microseismic Arrival Time-Picking Method Based on Variational Mode Decomposition. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13220. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413220