Abstract

This paper describes an application aimed at discovering cross streets within navigation routes by using the capabilities of the Google Maps API. The application’s core functionality revolves around locating the name of the succeeding cross street in the direction of the user, determined by their current location. To extract this information, the application synergizes the Nearest Roads library with the Geocoding API, utilizing a pair of points situated at an angle within a circular boundary centered on the user’s position, derived through the haversine formula. To ascertain optimal parameters for the circle’s radius and angle, a thorough sampling process encompassing 100 real-world instances from four Greek cities, Athens, Thessaloniki, Patras, and Karystos, was conducted. These cities were selected for their varying urban characteristics, enabling a comprehensive evaluation of the application’s performance across diverse street network complexities. The findings highlight the most effective degrees and radius parameters which exhibit an efficient success rate exceeding 91% in accurately finding the next cross street within navigation routes across the sampled cities. This paper provides a comprehensive account of the solution methodology, the process of sampling locations across diverse urban settings, and the resultant findings.

1. Introduction

The motivation for creating the algorithm highlighted in this paper and the corresponding mobile application originated from the feedback received from Greek blind and visually impaired users who were using a state-of-the-art outdoor blind navigation application that was developed in the framework of the MANTO project [1,2,3,4]. Blind users required information regarding the upcoming cross street in their moving direction [5]. This requirement was considered a must-have feature that any efficient blind outdoor navigation application should provide. Therefore, our team responded with studying the problem and proposing a solution that was integrated in the BlindRouteVision blind navigation application, which was able to discover and announce the name of the upcoming cross street in the direction of the user. In the rest of this paper, the term cross street is considered synonymous with the term intersection and the term perpendicular street/road.

The study outlined in this paper is contextualized within the broader landscape of navigation technologies, mapping APIs, and geographic calculation and road detection methodologies. It aims to contribute to the development of an algorithm and mobile application utilizing the Google Maps API [6] for the specific purpose of locating the upcoming cross streets in navigation routes. This will allow a variety of navigation services using Google Maps to be able to find cross streets and provide detailed information about intersections, including the cross streets’ names. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, up to now, only BlindSquare, a widely used worldwide GPS app developed on iOS for the blind and partially sighted [7], has been able to verbally cue intersections with a good success rate combining GPS and map data from sources like OpenStreetMap (OSM) [8]. OpenStreetMap is an initiative that creates and provides free street maps and label geographic data to anyone. Blind and visually impaired users navigating known routes, as well as our own experiments using the BlindSquare application in Athens, reported a small number of errors in dense data-crowded urbanized areas, which may increase significantly in less data-crowded city areas.

Navigation and mapping technologies have evolved significantly over the years, transforming the way people travel and interact with geographic data. The field has undergone a significant transition toward more efficient and precise methods of route guidance and location identification, moving away from traditional paper maps with the introduction of digital mapping systems and GPS-based navigation software.

In the realm of digital mapping, the utilization of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) has played a pivotal role in enabling developers to integrate robust mapping functionalities into various applications. The success of Maps APIs is attributed to their low-cost policy, extensive data coverage, open specification, simplicity of implementation, dynamic navigation, and querying capabilities [9].

Notably, the Google Maps API has emerged as a cornerstone in modern mapping, providing a range of tools and services for geographic data visualization, route planning, and location-based information retrieval. Several studies have highlighted the significance of Google Maps APIs in facilitating navigation solutions. For instance, [10] used Google Maps API and picture recognition technologies to develop a location-based service for tourism information. The authors of [11] developed a location-based medical service facility selector utilizing the haversine algorithm [12] (see Appendix B) to identify nearby medical facilities within a specific radius, employing the Google Maps API to calculate travel distance and time and employing the TOPSIS algorithm to determine the optimal choice based on these factors. Maps API-based services can also be integrated with verbal personal digital assistants using AI speech interaction, such as in the DALÍ system described in [13], whose goal is to provide the elderly and visually impaired with easy access to online services that make their life easier and encourage their continued participation in the society. The DALÍ system focuses specifically on simplicity of use through verbal speech and functional effectiveness in acquiring online information. The presented Alexa skill, which relies on a yellow pages service, demonstrates the range of potential assistive system capabilities and skills that can be directly verbally available to the elderly and visually impaired, overcoming the technology barrier that blocks them from having significant everyday benefits from the use of online services.

Within this landscape, the Google Maps API has demonstrated its versatility, enabling developers to harness features such as the Geocoding API [14] and the Nearest Roads library [15]. While the Nearest Roads library helps determine the nearest road segment based on a given latitude and longitude, the Geocoding API enables the conversion of addresses into geographic coordinates and vice versa.

To achieve the research objective, the presented application employs a combination of technological tools and algorithms. Specifically, it utilizes the Nearest Roads library in conjunction with the Geocoding API to extract the name of the next cross street based on the user’s current location and direction. The algorithm employs the haversine formula to create a circular boundary around the user’s location, enabling the selection of points positioned at an angle within this circle. These points facilitate the identification of the upcoming cross street in the user’s path.

The selection process for the circle’s radius and angle parameters crucially affects the accuracy and reliability of the application. To determine the most optimal values, a comprehensive sampling process was conducted involving one hundred (100) realistic examples of locations across four diverse cities in Greece: Athens, Thessaloniki, Patras, and Karystos. These cities were chosen due to their varying sizes and street network complexities, ensuring a comprehensive assessment of the application’s performance under diverse urban settings.

The outcomes of this study revealed that an angle of thirty (30) degrees and a radius of twenty-five (25) meters emerged as the most effective parameters, exhibiting a success rate exceeding 91% in accurately identifying the next cross street in navigation routes using Google Maps within the sampled cities. This configuration provides the ability to use the system to walk very large monthly pedestrian distances at no cost. The accuracy of the algorithm can be further improved through increasing the API requests, which might impose a small monthly usage cost to very large monthly distance walkers.

The following sections present a detailed account of the methodology used in creating the application, the process of sampling locations, and the findings obtained. By offering insights into the development and optimization of this application, this research contributes to enhancing navigation systems’ efficiency and usability.

2. Related Work

2.1. Intersection Detection—GPS, Trajectories, Maps

Digital road maps are clearly important for consumers and businesses. Most of these maps are created by companies fielding fleets of specialized vehicles equipped with GPS to drive on roads and record data, which is an expensive process. However, several works propose an alternative method using GPS data from regular vehicles driving their regular routes, aiming to facilitate the reconstruction of high-quality road networks through detecting intersections as the key locations that provide valuable information about the network topology. The authors of [16] used such data in the Seattle, USA, area. They presented a pattern recognition method for finding intersections, and subsequently, they connected the intersections with roads.

Similarly, Ref. [17] proposed a machine learning-based intersection detection approach based on the large-scale, real-world GPS trajectories of drivers from the Grab ride-hailing service [18]. Instead of representing locations with vector descriptors, they proposed a graph representation that models a location together with its local surroundings to improve the descriptiveness of the location descriptors and show that their approach outperforms the conventional multi-scale vector representation by 8.5%. Another study detects road intersections from common sub-tracks shared by different traces, instead of using the road users’ turning behaviors, applying local distance matrixes for pairs of traces and image processing techniques to find all sub-paths in the matrix [19].

The research objective, problem statement, and outcome of these efforts are far from the problem scope and solution presented in this paper.

2.2. Intersection Detection—Imagery, LIDAR, Remote Sensing

The identification and profiling of intersections from satellite images are challenging tasks aiming at understanding road networks and enabling navigation applications such as self-driving vehicles and route planning. The authors of [20] presented a labeled satellite image dataset for the intersection recognition problem consisting of almost 15 K satellite images of Washington DC, US. They used CNN architectures to determine how accurately the existence of intersections can be detected from satellite images, and they concluded that accuracy reaches 94% or greater than 80% if the models are trained with 40% of the dataset. In another relevant work [21], the same authors labeled a dataset of more than 7 K Google images from Washington, covering a region of almost 60 Km2 with 7.5 K intersections. They showed that the accuracy of the model is within 5 m for 88.6% of the predicted intersections (approx. 80% are within 2 m of the ground truth center). The authors of [22] detailed the generation of local datasets for road segmentation using satellite images and the corresponding mask images of Istanbul city through the Google Maps Platform, employing Deep Residual U-Net models trained separately for various zoom levels.

The authors of [23] present an automated computational geometry solution for precise road intersection mapping that eliminates common digitization errors. Unlike approaches that only detect intersection positions, the presented method reconstructs complete intersection geometries while maintaining topological consistency. The technique combines plane surveying principles (including line-bearing analysis and curve detection) with spatial analytics. When evaluated across urban contexts using manual digitization and OpenStreetMap data sources, the method demonstrated consistent performance with a correctness metric of 0.9. This solution was designed to enable transportation agencies to make data-driven maintenance decisions by providing reliable, standardized intersection inventories, as well as smart city applications.

The authors of [24] recognized that intersection detectors either ignore the rich semantic information already computed onboard or depend on scarce, hand-labeled intersection datasets. To close this gap, they presented a LiDAR-based method for intersection detection that fuses semantic road segmentation with vehicle localization to detect intersection candidates in a bird’s eye view representation. The method was evaluated through pairing detections with OpenStreetMap intersection nodes using precise GNSS/INS ground truth poses. The proposed approach achieves a mean localization error of 1.9 m and 89% precision. The same team further studied the critical problem of reliable global localization for autonomous vehicles, especially in environments where the GNSS is degraded or unavailable, and proposed a novel approach to bridge the modality gap between coarse OSM intersection representations and dense sensor-derived data collected by autonomous vehicles aiming at robust vehicle localization [25].

The authors of [26] proposed a variant of a Long-Term Recurrent Convolutional Network to detect road intersections called IntersectNet. Road intersection detection is addressed as a binary classification task over a sequence of image frames.

2.3. Intersection Modeling—OSM, Complex Junctions, Graph Algorithms

The authors of [27] address the problem of lacking turn information and time restrictions at OSM intersections in OSM public digital maps. They propose a new turn information detection method for OSM intersections using dynamic connection information from crowdsourced trajectory data. They extract the OSM intersection structure and project crowdsourced trajectories onto OSM road segments using an improved Hidden Markov Model (HMM) map matching method that explicitly traces the turning connections in road networks and outputs paired with turning rules and turning time restrictions per hour. The study transforms complex turning identification scenarios into simple analyses of traffic connectivity. Furthermore, a voting strategy is used to identify and calculate turning time restrictions. The experimental results, using trajectory data from three cities in China (Shanghai, Wuhan, and Xiamen), show that the turning relationships can be detected at a precision of 90.71%.

The authors of [28] propose an efficient approach to building a fine-grained road network based on sparsely sampled private car trajectory data under a complex urban environment. In order to resolve the difficulties introduced by low-sampling-rate trajectory data, they concentrate sample points around intersections by utilizing the turning characteristics from the large-scale trajectory data to ensure the accuracy of the detection of intersections and road segments. They first layer intersections into major and minor ones and then propose a simplified representation of intersections and a corresponding computable model based on the features of roads, which can significantly improve the accuracy of detected road networks. Extensive evaluations are conducted based on a real-world trajectory dataset from 1345 private cars in Shenzhen city of China. The constructed road network closely matches the one from a public editing map OpenStreetMap, especially the location of the road intersections and road segments, which achieves 92.2% intersections within 20 m and 91.6% road segments within 8 m.

2.4. Outdoor Blind Navigation—Intersection-Aware Method

The authors of [29] focus on the self-localization needs of blind or visually impaired travelers, who are faced with the challenge of negotiating street intersections. These travelers need more precise self-localization to help them align themselves properly to crosswalks, signal lights, and other features such as walk light pushbuttons. To alleviate GPS errors, they propose a computer vision-based localization approach that is tailored to the street intersection domain. The presented technique harnesses the availability of simple, ubiquitous satellite imagery to create simple maps of each intersection. Key to the approach is the integration of IMU (inertial measurement unit) information with geometric information obtained from image panorama stitchings. The authors demonstrate that the localization performance of the proposed algorithm on a dataset of 20 intersection panoramas is better than that when relying solely on the GPS. More specifically, the localization error in the proposed method is measured under 2 m in most cases, with only two errors around 16 m that resulted from either a severely distorted magnetometer reading or the poor segmentation of the aerial image. Instead, GPS localization errors are approx. 10 m on average, with three errors between 16 and 21 m.

The authors of [30] recognize that the navigation systems used to help people with visual impairments lack information regarding crucial crossing points, including intersections. They propose an algorithm that prioritizes safety over distance by recommending a safer route. Unlike conventional methods focusing on finding the shortest path, the proposed algorithm aims to decrease the danger level of the suggested route based on user preferences, such as uncontrolled intersections and parking space entrances. The authors utilize their own image recognition machine learning-based intersection detection algorithm to accurately identify the spatial coordinates and degree of each intersection [21].

The authors of [31] present an impractical solution to the problems involved in announcing the name of the current intersection to people with visual impairments. The goal was to present necessary information in clear, concise language transmitted from Bluetooth Beacons through their smartphones upon reaching the intersection. The objective of this study was to determine the feasibility and effectiveness of providing information to visually impaired pedestrians in a simpler and more native format. Clearly, this method suffers from the major problems of the limited availability of this capability only at signalized intersections and having to deploy and maintain several thousands of IoT devices across several thousands of city road intersections.

The authors of [32] intend to provide blind and low-vision people with real-time, precise information about their location and surroundings, which is crucial for safe navigation. They propose the use of a street camera-based navigation system that provides real-time auditory feedback to help users know exactly when to cross the street. The system will use street-level view cameras which have been deployed in NYC in the framework of a wireless edge-cloud server. However, they have not yet evaluated their proposed system. This solution will clearly suffer from the same problems as the previous one.

The authors of [33] proposed a mobile-cloud collaborative approach for context-aware outdoor navigation, which uses the computational power of resources made available by cloud computing providers for real-time image processing. The system architecture has minimal infrastructural reliance, thus allowing for wide usability. The developed outdoor navigation application with integrated support for pedestrian crossing guidance is promising for real-time crossing guidance for blind pedestrians. This solution is different than the system proposed in this paper, as it is unable to announce the names of cross streets and help the user create and maintain an accurate mental representation of the sequential structure of the route.

2.5. Blind Navigation—Map/OSM/StreetView-Based Method

The authors of [34] recognize that unlike car-based services where instructions generally comprise distance and road names, pedestrian instructions should instead focus on the delivery of landmarks to aid in navigation. The authors present a prototype navigation service that extracts landmarks suitable for navigation instructions from the OSM dataset based on several metrics. This is coupled with a short comparison of landmark availability within OSM and differences in routes between locations with different levels of OSM completeness and a short evaluation of the suitability of the landmarks provided by the prototype. Landmark extraction is performed on a server-side service, with the instructions being delivered to a pedestrian navigation application running on an Android mobile device. It is worth mentioning that the process is not without its shortcomings. Testing has shown limitations based on underlying OSM completeness in less urbanized areas and areas being less well mapped in OSM, also including the road names derived from OSM, but the road networks tend to be much better documented in OSM than other features.

The authors of [35] present an accessible street view tool, StreetViewAI, which combines context-aware, multimodal AI; accessible navigation controls; and conversational speech. With StreetViewAI, blind users can virtually examine destinations, engage in open-world exploration, or virtually tour any of the over 220 billion images and 100+ countries where Google StreetView is deployed. The system was designed iteratively with a mixed-visual ability team and was evaluated by eleven blind users. The study demonstrates the value of an accessible street view in supporting POI (point of interest) investigations and remote route planning. With StreetViewAI, visually impaired users can interactively pan and move between panoramic images; learn about nearby roads, intersections, and places; hear real-time AI descriptions; and dynamically converse with a live, multimodal AI agent about the scene and local geography. The visually impaired users involved in the requirement analysis suggested to add a key shortcut for “What is the next intersection?”. Therefore, two relevant shortcut keys were added to the system features: a location information key (Alt + I) to obtain information about the current and next intersections (if any) and a movement control key (Alt + J) to jump to the next intersection. To implement the action for jumping to the nearest intersection, since the Google Maps API does not provide road intersection data, the StreetViewAI team implemented an intersection detection algorithm casting a ray from the user’s current location projected along their current heading and incrementally checking each point for an intersection with a specified step size (15 m), search grid size (20 × 20 m), and maximum distance (70 m). To detect intersections at each step, they use the Google Roads API to request roads and their geometry within the search grid. This closely resembles the method we propose in this paper. The developers of StreetViewAI report that it works well in practice; however they do not provide any evidence to support this statement.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Request Point Selection

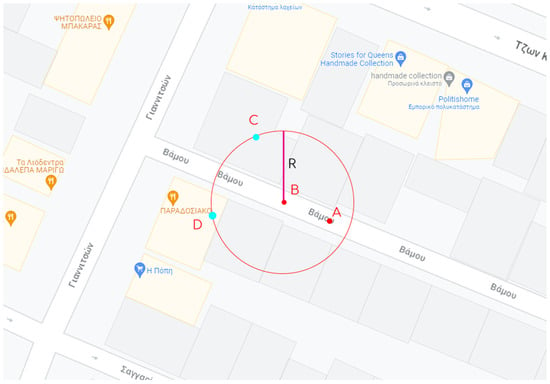

The goal of this process is to identify the name of the subsequent cross street using the map API. An appropriate method is essential to pinpoint one or more points situated at a shorter distance from the next intersecting road compared to any other road. The input dataset comprises both the present location of the user and their location ten (10) seconds earlier. The user’s prior location is necessary to determine their direction. The points need to be selected as follows (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Guidance on point selection methodology.

- Point A is the location where the user was located ten (10) seconds ago.

- Point B is the user’s current location.

- Centered at point B, a circle with radius R is created.

- On the circumference of the circle and in the direction of the user, two points C and D are selected, at specific angles, which are used as input to the Nearest Roads API and next to the Geocoding API library. The results are expected to be the name of the next nearest cross street in the user’s direction.

This point selection method consists of two variables. These are the following:

- The radius R of the circle centered on the user’s current location.

- The degrees of the angle that determines at which point on the circumference of the circle points C and D will be selected.

To find the most appropriate values for these variables, many examples in different cities were sampled.

3.2. User Movement Direction

The abovementioned points are points on the earth surface. The distance calculations will be performed using the haversine formula (see Appendix B) using the latitude and longitude of the points of interest. The user’s movement direction is used to pick a desired angle for the point selection process. To find the bearing, the change in latitude and longitude is calculated.

Then the bearing (user’s direction) is calculated with the following formula:

3.3. Point Selection on Circle Given Angle

The creation of a circle with a given center point is performed using an adaptation of the haversine formula. This known process is presented in Appendix B. To select a point on the circle at some given degrees, the desired angle theta is converted to radians.

Then the latitude and longitude of the selected point are calculated.

Δlat and Δlong represent the changes in latitude and longitude, and lat1 and long1 are the latitude and longitude of the center point of the circle. By substituting the desired angle (theta) into the equations, we can obtain the latitude and longitude coordinates of the circle point at the given angle.

3.4. Sampling Method and Cross Street Detection Algorithm

The optimal detection of the next cross street requires a comprehensive sampling of multiple coordinates to determine the most suitable values for two crucial parameters: (1) the radius of the circular boundary centered at the user’s most recent known position; (2) the angle utilized for the selection of points along the circle’s circumference. These points serve as input for identifying the cross street through the API.

To evaluate these parameters, a sampling of one hundred (100) coordinate pairs was undertaken. Each pair comprises the geographic coordinates of the user’s location ten (10) seconds before their last known position and their current position. The sampled coordinate pairs encompass diverse cities across Greece, providing examples of varied urban environments and street networks to ensure representative and accurate results. Specifically, sixty-seven (67) pairs are situated in Athens, the crowded capital city; twenty-two (22) pairs in Thessaloniki in northern Greece, the second largest city and capital of the geographical region of Macedonia; ten (10) pairs in the city of Patras in western Greece, the third largest city hosting a large commercial hub and a busy port at a nodal point for trade and communication; and one (1) pair in the small town of Karystos in Evia island, encompassing cities with varying sizes and road network densities. Obviously, the single sample in Karystos cannot be considered an adequate sample set; however it represents a direction for a future trial involving rural areas. Appendix A presents in detail the randomly selected 100 city points that were used to validate the proposed cross street detection algorithm.

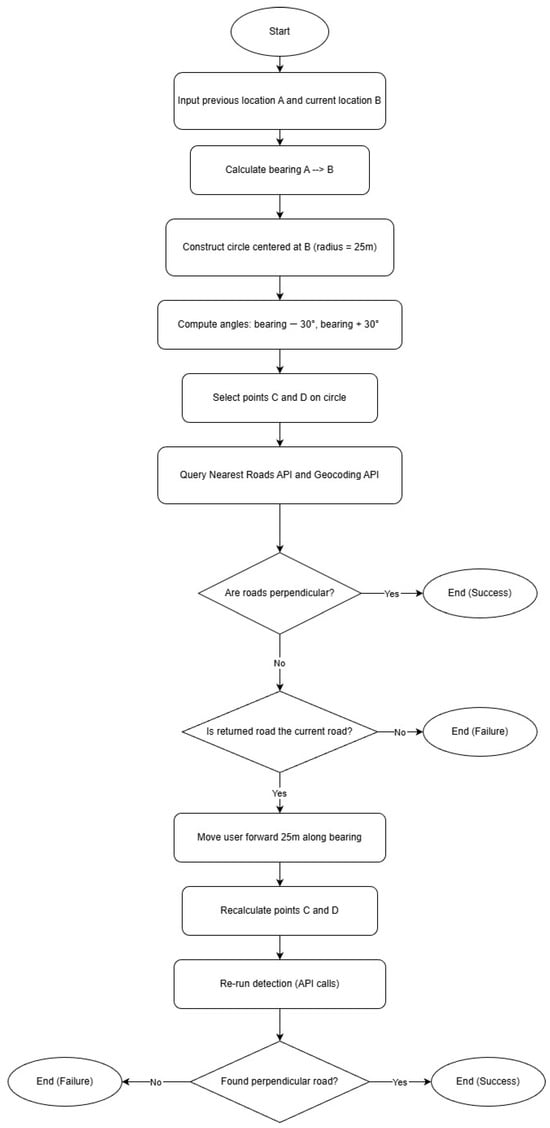

These coordinate pairs, along with different combinations of circle radiuses (twenty-five (25), thirty-five (35), and fifty (50) meters) and angle parameters (twenty (20), thirty (30), and forty (40) degrees), serve as input data for the algorithm illustrated in Figure 2. The algorithm outputs the name of a road, with success defined as correctly identifying the subsequent cross street in the user’s direction. An acceptable outcome also includes recognizing the road upon which the user is currently traveling, signifying that the next cross street is still a distance away, necessitating a repeated algorithm execution shortly for proximity refinement. Any deviation from these expected outcomes or inability to retrieve data is considered a failure.

Figure 2.

Cross street detection algorithm.

The results obtained from all coordinate samples are analyzed by comparing the success rates associated with each combination of circle radius and angle. The combination exhibiting the highest success rate and the lowest probability of error is chosen for optimal application performance. An error probability exceeding five percent (5%) is deemed unacceptable, as it would introduce excessive navigation errors for the user.

3.5. Very Precise GPS Positioning

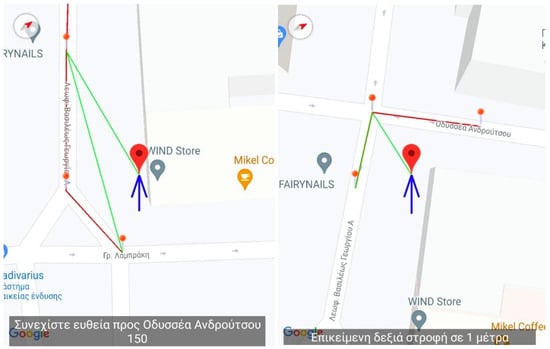

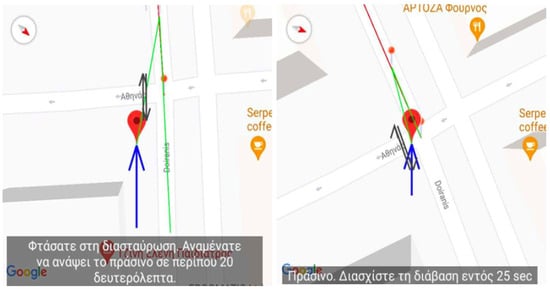

The MANTO RTD project [1,2,3,4] developed and validated the BlindRouteVision outdoor navigation application addressing the autonomous safe pedestrian outdoor navigation of blind people and the visually impaired. Building upon very precise (centimeter-level) positioning, it aims to provide an accessibility walking aid for blind people. The application operates on smartphones exploiting Google Maps to implement a real-time, precise user tracking and voice-guided navigation service (see Figure 3). The smartphone application is supported by an external embedded Bluetooth device integrating a microcontroller, a high-precision GPS receiver, and an optional servo-motorized ultrasonic sensor for the real-time recognition and bypassing of obstacles along the route of the blind [4]. Application features include voice-selected route destinations and supported functions, precise synchronization with traffic lights (see Figure 4) [3], the exploitation of dynamic telematic information regarding public transportation timetables and bus stops for building composite routes, which may include public transportation segments in addition to pedestrian segments, emergency notifications for carers, etc. The developed application establishes many state-of-the-art features regarding blind navigation, enhancing the independent living of blind people in Greece and all over the world.

Figure 3.

BlindRouteVision navigation. (Left): Move forward towards Odyssea Androutsou Str. (Right): Turn right in 1 m. Navigation route and user position and tracking lines are overlaid on the maps.

Figure 4.

BlindRouteVision navigation for traffic-light crossing. (Left): Stop. Traffic light crossing reached. Wait for 20 s. (Right): Green. Total of 25 s remaining to cross. Navigation route, traffic-light crossing, and user position and tracking lines are overlaid on the maps.

Figure 5 illustrates the external Bluetooth device which is paired with the mobile BlindRouteVision navigation application. This device is powered by an ATmega328P microcontroller (Atmel, San Jose, CA, USA) and integrates the U-Blox NEO-8M GPS Receiver (u-blox, Thalwil, Switzerland), which demonstrates very high precision in reporting the user position. This device offers a unique advantage in blind navigation, reporting the accurate user position to the mobile application every second, typically with a centimeter-level positioning error, typically less than 1 m in almost all cases, and this is the basis for the robust operation of the proposed cross street detection algorithm. This is different than the typical smartphone that integrates a cost-effective GPS receiver with a small antenna surface to fit size restrictions, leading to inaccuracies from a few meters to much worse in dense urban environments. The phone hardware itself, due to its low GPS antenna quality and phone case obstruction, is a common cause of positioning errors, demonstrating typical error ranges of 2–10 m in good open-sky conditions and even exceeding 20–40 m in poor conditions with tall buildings, signal reflections, cheap/bad receivers, and an insufficient number of satellites.

Figure 5.

External Bluetooth device of mobile BlindRouteVision navigation application integrating very precise GPS receiver for centimeter-level positioning.

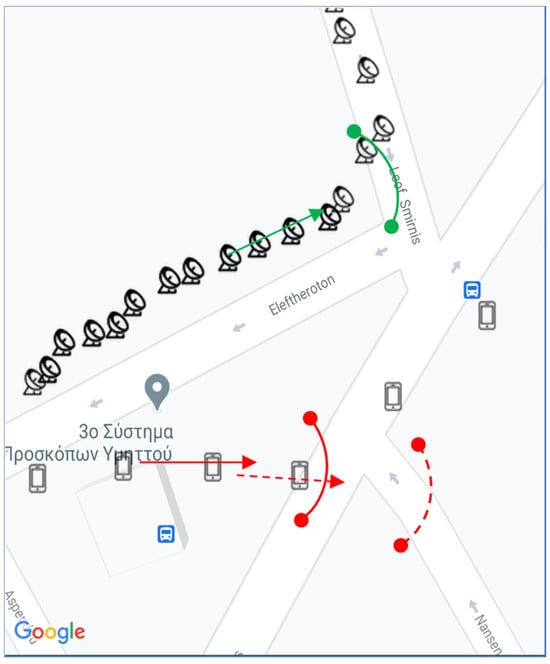

Figure 6 illustrates the significant positioning error introduced in the navigation application by a typical smartphone GPS receiver compared to using the external device in Figure 5 and its integrated very-high-precision GPS receiver. A Nokia 8.1 Android One smartphone (HMD Global, Espoo, Finland), was used in this measurement. The phone’s small overlay icons illustrate the highly inaccurate sparse user positions reported by the smartphone GPS receiver, while the satellite dish icons represent the highly accurate user positions densely reported by the external GPS receiver along the user path on the left pavement of Eleftheroton Str. (the user is moving from left to right). Due to the positioning error of the smartphone GPS receiver, the upcoming cross street that is falsely detected by the proposed algorithm is Konstantinoupoleos Str. (red scenario), whose name is missing in the picture, instead of the correct Smirnis Ave. (green scenario), which is reported by the algorithm under very precise GPS user positioning. Next, false detection (dashed red scenario) is even worse, detecting Nansen Str., which is very far from the user, as the upcoming cross street in the user path. The reason for a considerable rate of false cross street detections in urban blind navigation when using a smartphone GPS receiver and map-based APIs is clearly illustrated in this real-world paradigm, which is highlighted as no other than the typical, often significant, user positioning error reported by the smartphone GPS.

Figure 6.

Example of how GPS errors (red path) can lead to failed upcoming cross street detections.

4. Results

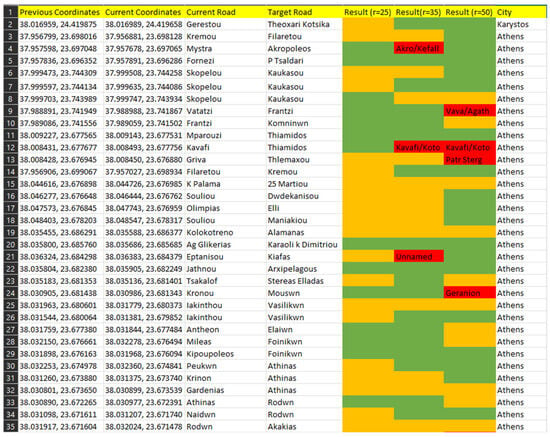

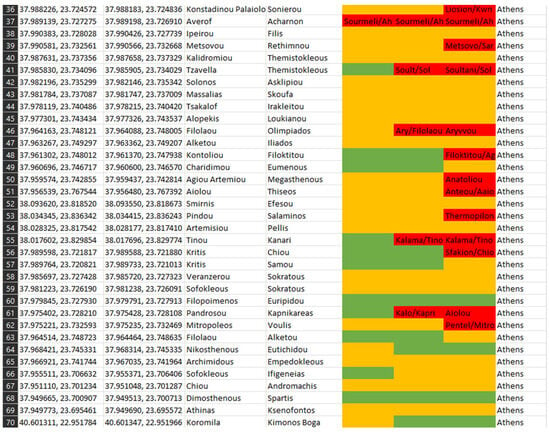

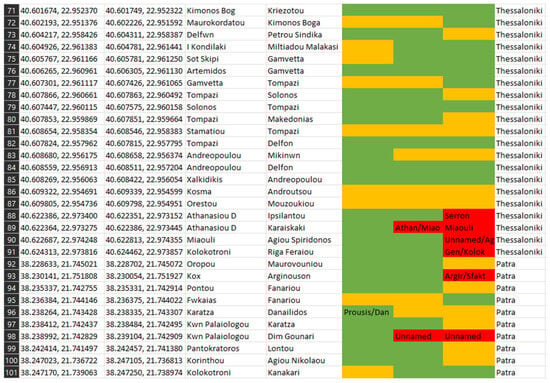

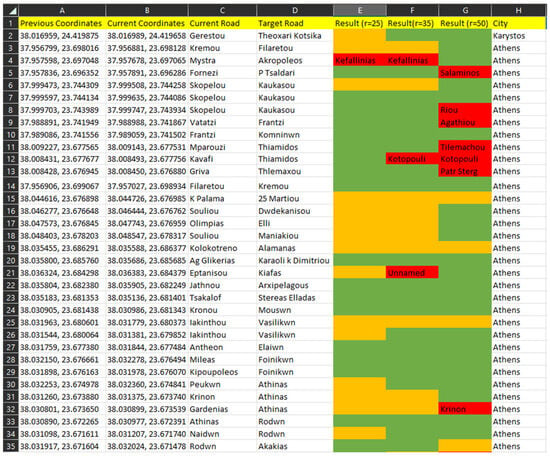

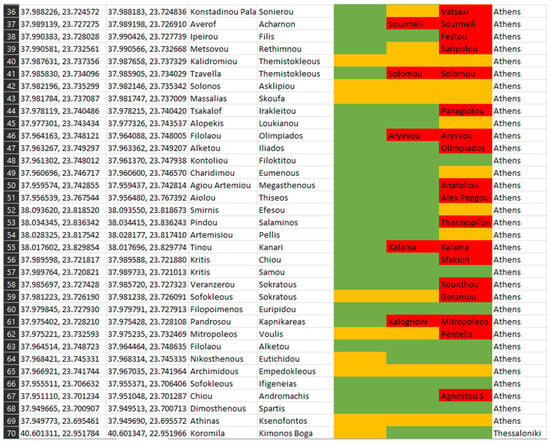

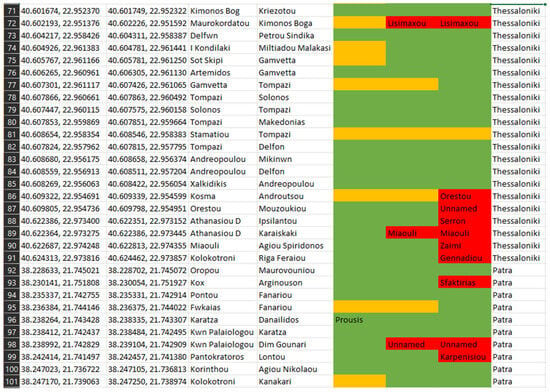

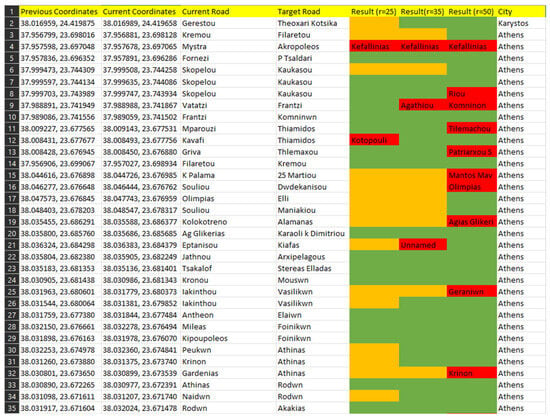

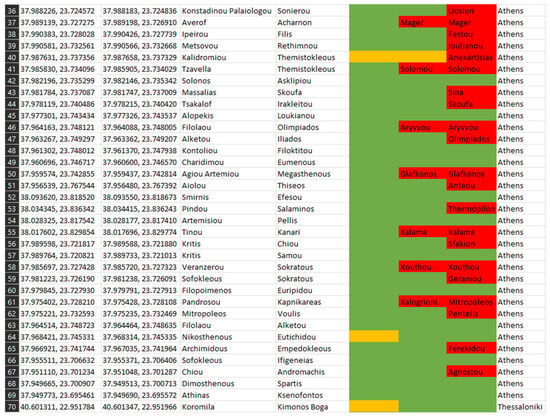

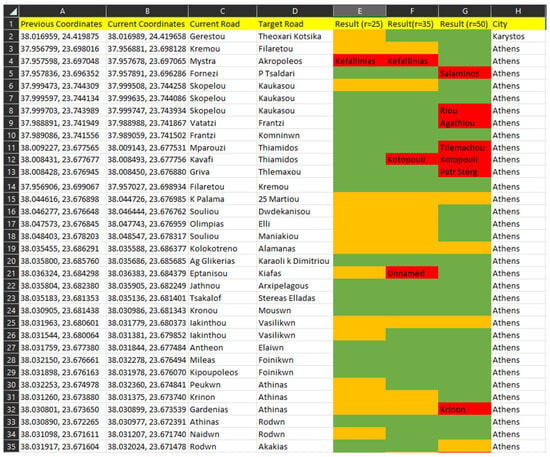

The analytic tables in Appendix A (Figure A1, Figure A2, Figure A3, Figure A4, Figure A5, Figure A6, Figure A7, Figure A8 and Figure A9) show the results of executing the next cross street algorithm with the input being the sample combinations detailed in the previous section.

- The first column contains the longitude and latitude of the position where the user was ten (10) seconds before reaching their current position.

- The second column contains the longitude and latitude of the user’s current position.

- The third column names the road on which the user is moving.

- The fourth column names the ‘target’ street, i.e., the next cross street in the direction in which the user is currently moving.

- The next three columns show the result of the detection algorithm when it takes as input the coordinates from the first two columns and compares it with the fourth column, i.e., the expected cross street. Green cells mark a successful answer, i.e., that the correct cross street was found. Yellow cells mark an acceptable answer that the road found is the road on which the user is currently moving. Finally, red cells indicate a failed answer, i.e., either the road found is another irrelevant road or no data was found. Each column refers to the different radiuses of the circle centered on the current position of the user. The first refers to a radius of twenty-five (25) meters, the second refers to thirty-five (35) meters, and the third refers to fifty (50) meters.

- The eighth column indicates the city in which the coordinates of the first columns are located, i.e., Athens, Thessaloniki, Patras, or Karystos.

From the detailed results listed in Appendix A regarding the execution of the proposed algorithm on one hundred (100) city point examples, the pass, fail, and acceptable result rates for all combinations of radiuses and degrees of angles are extracted and presented in the tables below. Each column shows the results for different radius lengths, i.e., twenty-five (25), thirty-five (35), and fifty (50) meters.

Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 show the percentage results for twenty (20)-, thirty (30)-, and forty (40)-degree angles on the circle, respectively.

Table 1.

Results for 20-degree angle.

Table 2.

Results for 30-degree angle.

Table 3.

Results for 40-degree angle.

Summarizing the experiment results, we come to the following conclusions:

- At a twenty (20)-degree angle, both the thirty-five (35)- and fifty (50)-meter radiuses exhibit high failure rates of twenty-three percent (23%) and ten percent (10%), respectively. However, the twenty-five (25)-meter radius demonstrates a forty-seven percent (47%) success rate, fifty-two percent (52%) acceptability, and only one percent (1%) failure, establishing it as an acceptable combination.

- With a thirty (30)-degree angle, the thirty-five (35)- and fifty (50)-meter radiuses show high failure rates of thirty-five percent (35%) and eleven percent (11%), respectively. Conversely, the twenty-five (25)-meter radius showcases a sixty-seven percent (67%) success rate, thirty-two percent (32%) acceptability, and a mere one percent (1%) failure, thus constituting another acceptable combination.

- Employing a forty (40)-degree angle, the thirty-five (35)- and fifty (50)-meter radiuses reveal considerable failure rates of forty-one percent (41%) and fourteen percent (14%), respectively. Conversely, the twenty-five (25)-meter radius presents a seventy-one percent (71%) success rate, twenty-five percent (25%) acceptability, and four percent (4%) failure rate, establishing it as an acceptable choice.

Considering the existence of three (3) acceptable combinations, all featuring the twenty-five (25)-meter radius, it is evident that this radius length is the optimal choice for the application’s cross street identification. Regarding the angle selection for determining the points defining the vertical path, the angle of thirty (30) degrees emerges as the preferred choice due to its highest success rate (67%) and lowest failure rate (1%).

5. Discussion

5.1. Handling Acceptable Results

In the sampling procedure presented in the previous section, the algorithm outputs were categorized into three types: successful, acceptable, and failed. While successful outputs indicated that the application correctly identified the next cross street, acceptable outputs occurred when the algorithm returned the current road instead. This typically implies that the next cross street is still too far from the user’s current position to be detected within the selected radius.

To address acceptable cases effectively, we implemented a re-evaluation mechanism. The idea is to rerun the algorithm at a projected forward position, assuming the user continues along the same path. This anticipatory rerun is grounded in the assumption that if a cross street is not yet within the detection radius, it might become so after the user has moved further along their route.

5.2. Iterative Forward Simulation

The proposed solution is to simulate movement along the user’s direction of travel by advancing their position in discrete steps, each 25 m forward, aligned with their current bearing (as calculated using the haversine-based bearing formula). At each simulated position, the algorithm is executed again using the established parameters (angle: 30 degrees; radius: 25 m).

This process is repeated up to a maximum of three iterations (i.e., 75 m forward) or until a successful cross street identification is achieved. If the correct cross street is not located, the result is marked as “failed”.

5.3. Experimental Results from Iterative Simulation

From the original 100 test cases, 32 were classified as acceptable in the initial run. When subjected to the iterative re-evaluation mechanism described above, the following outcomes (see Table 4) were observed.

Table 4.

Iterative simulation.

This means that 75% of initially acceptable cases eventually resulted in a successful identification of the next cross street through at most three forward iterations. Only eight cases (25%) failed to resolve into successful detections, often due to issues such as complex or irregular street geometries, sparse road networks with no clear intersections within 75 m, and GPS inaccuracies or poor address data in the Geocoding API response.

5.4. Advantages and Implications

This iterative approach adds robustness and adaptability to the algorithm by introducing a fallback mechanism when the initial result is inconclusive. Rather than returning potentially misleading or incomplete information, the system proactively refines its prediction, improving the user experience without relying on additional user input.

Moreover, this mechanism is computationally lightweight and API-efficient, as each step involves a small number of requests (just two coordinate points per rerun). Since only acceptable cases are retried, the additional cost remains low and predictable.

5.5. Final Evaluation

By incorporating the iterative error-handling mechanism, we effectively resolved the ambiguity of acceptable cases. Out of the original 100 test cases, 67 were immediately successful, 32 were initially acceptable, and 1 failed outright. After applying the forward re-evaluation procedure to the 32 acceptable cases, 24 of them were upgraded to successful identifications, and 8 were ultimately classified as failures.

This refinement updates the overall outcome distribution as follows:

- Final successful detections: 67 (initial) + 24 (resolved) = 91%;

- Final failures: 1 (initial) + 8 (from acceptable) = 9%.

This demonstrates a significant improvement in the algorithm’s reliability, elevating the initial 67% direct success rate to a total effective success rate of 91%, with minimal failure. These results confirm the robustness of the proposed algorithm when combined with the iterative forward-checking approach, making it suitable for real-world navigation scenarios with high accuracy and resilience.

We consider this a novel contribution that efficiently solves the problem of discovering the upcoming cross streets in a real-world Google Maps blind navigation scenario. The proposed navigation application can run efficiently on cost-effective Android smartphones. On the other hand, BlindSquare, which can detect the intersections in navigation routes using OSM’s available road intersection data, is dependent on the crowdsourced OSM data completeness, and its behavior can be poor in less urbanized areas and also because of the typical GPS positioning error. Furthermore, it is only available on more expensive iPhone devices. The analysis of the relevant research literature revealed only one relevant effort [35], which faces the problem of discovering the name of the upcoming intersections in offline virtual-world Google StreetView navigation. The authors propose a method to resolve the problem with the Google Maps API, which does not provide road intersection data; however they do not present any evidence to support their claim that their detection method works well in practice.

Other relevant highly computationally intensive works perform either unnamed imagery intersection detection using machine learning training on large image datasets or intersection detection addressing autonomous driving using large datasets of GPS trajectories from regular vehicles or intersection modeling using graph algorithms in public map data, mainly OSM. For all these efforts, it is difficult to adapt the methods to the problem of detecting the names of the upcoming cross streets in blind navigation, imposing high computation requirements and autonomy limitations on end user mobile navigation devices or necessitating the deployment of complex server-side or cloud infrastructures. At the same time, the reported detection performance is worse or equal to that of our method, as detailed in Section 2. The remaining OSM-based navigation and blind navigation efforts resemble the BlindSquare case, while they fail to evaluate the performance of intersection detection.

5.6. Real-World Route Execution and API Cost Estimation

To evaluate the feasibility of using the application during real-life navigation, we must consider how frequently the algorithm needs to run in order to detect every cross street encountered in the user’s direction. Since intersections are not typically predictable at a distance, the application must periodically check for the next cross street as the user moves forward.

5.6.1. Interval Frequency and User Movement

A key factor in determining how often the algorithm should run during real-world use is the walking speed of the user. For standard pedestrian navigation, the average walking speed is approximately 1.4 m per second, meaning that the user covers roughly 25 m every 18 s. Since the algorithm’s detection radius is also 25 m, this interval serves as a useful baseline: the algorithm can be scheduled to run approximately every 15 to 20 s to detect new cross streets in a timely manner.

However, it is important to recognize that walking speed can vary significantly among users, particularly for individuals with disabilities. For example, a visually impaired person or someone with limited mobility may walk more slowly, averaging 0.7 to 1.0 m per second. In such cases, the interval between algorithm executions should be dynamically increased to prevent unnecessary API calls and reduce costs and battery and data usage. Table 5 presents the algorithm scheduling details depending on the user type. Appendix C details the implied usage cost regarding the relevant API calls.

Table 5.

Algorithm scheduling per user type.

By adapting the timing of the algorithm to match the user’s actual movement, the system becomes more efficient and inclusive, avoiding excessive API usage while still ensuring that cross streets are detected at the right moment. This adaptability is particularly important in contexts where the application might be designed to assist blind or low-vision users, offering them reliable and context-aware navigation support.

System performance is adequate for operation intended for real-time navigation, in which latency is a critical parameter. The algorithm’s response, including the Google Maps API execution time, is prompt, and it typically takes 1 s. Considering pedestrian speed, the system has enough time to notify the user about the upcoming cross street.

5.6.2. Cost Estimation for Real-World Navigation

To estimate the cost of using the application during a real navigation session, we consider the frequency of API calls discussed in the previous section. Assuming an average pedestrian walks at 1.4 m/s and the algorithm runs every 25 m, a 1 km route would require approximately 40 iterations of the algorithm. This results in 40 requests to each API per kilometer. Using the standard pay-as-you-go pricing model [36,37], the free usage tier (see Appendix C) can accommodate 5000/40 = 125 monthly pedestrian kilometers at no cost. The majority of blind and visually impaired users would not exceed the aforementioned monthly free usage limit. Assuming the application has exceeded the free usage tier, the estimated cost per additional Km would be as follows:

- Roads API: 40 requests × USD 10.00/1000 = USD 0.40;

- Geocoding API: 40 requests × USD 5.00/1000 = USD 0.20;

- Total per 1 Km route after 125 free Km: USD 0.60.

This makes the system affordable for low-volume use. However, for applications operating at scale or supporting many users concurrently, these small per-user costs can accumulate rapidly, highlighting the importance of optimization strategies.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper presented an algorithm for discovering the cross streets within navigation routes using Google Maps. The algorithm discovers the name of the upcoming cross street in the direction of the user and was designed to support blind navigation. Since this information is not directly provided by the Google Maps API, a mechanism was proposed to formulate proper Geocoding API and Nearest Road API requests that return the name of the upcoming cross street in the user direction. The fine tuning of the algorithm parameters that decide the optimal request points was based on a random sampling process encompassing 100 real-world city points reflecting varying urban characteristics and enabling a comprehensive evaluation of the algorithm’s performance across diverse street network complexities. The algorithm demonstrates an efficient success rate of 91% in accurately finding the upcoming cross street within navigation routes across the sampled cities with the completely free use of the Google Maps Nearest Road and Geocoding APIs.

The mentioned performance meets the strictest requirement set forward by numerous blind and visually impaired users involved in the MANTO project regarding a must-have upcoming cross street announcement functionality when using a smartphone-based outdoor blind navigation application, an important feature that significantly improves the user experience. They demanded correct upcoming cross street announcements in nine out of ten cases, which is better than their established experience with the iOS BlindSquare blind navigation application.

The success rate of the algorithm can be further improved by increasing the frequency of API requests, but this may accumulate some API usage cost for very large monthly distance walkers. It is estimated that with radius and angle settings of 15 m and 40 degrees, respectively, which increases API requests by 80%, the accuracy of the algorithm can exceed 96%, providing a free monthly pedestrian distance budget of 75 Kms. This capability was integrated on our state-of-the-art mobile BlindRouteVision blind navigation application, which was initially designed and implemented for Android smartphones. The algorithm’s performance relies on precise GPS positioning, which is always achieved in our system using a very precise GPS receiver demonstrating centimeter-level positioning errors, as detailed in Section 3.5. The proposed method, like many other efforts, would face limitations under the existence of significant GPS errors, as explained in Section 3.5.

Future work will involve the introduction of a new mechanism which will demonstrate a completely robust zero failure rate in discovering upcoming cross streets during blind navigation using the Google Maps API, with much fewer Nearest Road API and Geocoding API requests and zero cost for the user. Furthermore, the proposed algorithm will be made available using the open OpenStreetMaps and OSRM [38] APIs, not being restricted to Google Maps alone and contributing to the long-term sustainability of the proposed solution. Finally, the proposed method’s performance will be evaluated against the classical road name method of navigation in OSM, including an evaluation of how well the road networks are documented in OSM, especially in less urbanized areas or rural areas or where OSM completeness is low.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.; methodology, A.M.; software, G.M.; validation, A.M. and G.M.; formal analysis, A.M. and G.M.; investigation, G.M.; resources, A.M.; data curation, G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M. and G.M.; writing—review and editing, A.M.; visualization, G.M.; supervision, A.M.; project administration, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

To increase transparency and scientific value and to allow other researchers to verify the results and validate the algorithm in other cities, the used dataset (geographic coordinates of 100 points) and the algorithm’s source code are made available to the research community via the GitHub open repository: https://github.com/gmantzoros/MantoPerpendicularRoad (accessed on 12 December 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Costas Filios for his unique contribution regarding the design and implementation of the mobile BlindRouteVision navigation application, including the application’s external Bluetooth device for centimeter-level GPS positioning.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| INS | Inertial Navigation System |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| OSM | OpenStreetMap |

| OSRM | Open Source Routing Machine |

| POI | Point of Interest |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LRCN | Long-Term Recurrent Convolutional Network |

| HMM | Hidden Markov Model |

| USD | United States Dollar |

| DOI | Digital Object Identifier |

Appendix A. Detailed Data and Results of Algorithm Execution on 100 City Map Points

Figure A1.

Results for points 1–34 and 20-degree angle.

Figure A2.

Results for points 35–69 and 20-degree angle.

Figure A3.

Results for points 70–100 and 20-degree angle.

Figure A4.

Results for points 1–34 and 30-degree angle.

Figure A5.

Results for points 35–69 and 30-degree angle.

Figure A6.

Results for points 70–100 and 30-degree angle.

Figure A7.

Results for points 1–34 and 40-degree angle.

Figure A8.

Results for points 35–69 and 40-degree angle.

Figure A9.

Results for points 70–100 and 40-degree angle.

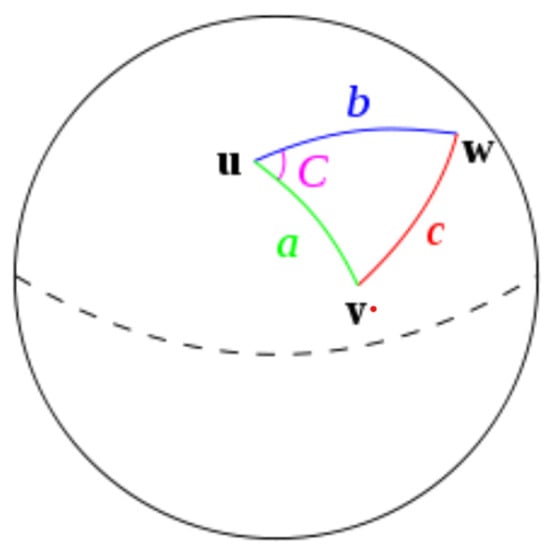

Appendix B. Haversine Formula

Appendix B.1. Haversine Formula

The cosine–haversine formula is a widely used trigonometric formula used in celestial navigation to compute the altitude of a celestial body for the accurate determination of the position of a ship or plane [12].

The haversine method computes the distance between two coordinates in a straight line, ignoring any hills or valleys on the surface. This technique takes latitude and longitude as input. The result is the distance between the two locations. Essentially, the earth’s shape is slightly elliptical. The haversine formula determines the distance of a circular object by providing three locations. It is part of the trigonometry formula formation model. The haversine formula is quite similar to that for the shape of a triangle drawn on the sphere’s surface [39].

Figure A10 is a depiction of the haversine method applied to the earth. There are three coordinates: “u”, “v”, and “w”. These three coordinates form the distance builder in the haversine calculation. Haversine calculations can be formulated into the following equation.

where Φ = latitude; λ = longitude; R = earth radius.

Figure A10.

Haversine’s law.

Appendix B.2. Creation of Circle with Given Center Point

The next cross street detection algorithm presented in this paper must be able to calculate the longitudes and latitudes of points on the circumference of a circle using the coordinates of its center and its radius. This can be performed with the following adaptation of the haversine formula:

The change or difference in latitude (Δlat) and longitude (Δlong) between the center point and the boundaries of the circle needs to be calculated. The change in latitude, Δlat, is determined by dividing the variable radius by the radius R of the earth. This gives the angular distance covered in latitude. The change in longitude, Δlong, is determined by dividing the variable radius by the product of the earth’s radius R and the cosine of the latitude of the central point lat1. This takes into account the shrinkage of longitude lines as we move away from the equator.

Then the maximum and minimum values of latitude and longitude that define the boundaries of the circle are set. By adding and subtracting the corresponding changes in latitude and longitude from the latitude (lat1) and longitude (long1) of the center point, we obtain the limits of the latitude and longitude of the circle.

Appendix C. Google Maps Platform Pricing Overview

The presented project utilizes two core services from the Google Maps Platform: the Roads API (specifically, the Nearest Roads feature) and the Geocoding API. These services operate under a tiered, pay-as-you-go pricing model that includes free usage quotas and progressive rate adjustments based on monthly volume. This flexible structure makes the APIs accessible for both prototype-level applications and large-scale production systems.

Appendix C.1. Roads API—Nearest Roads

The Roads API is employed to determine the nearest navigable roadway to a given set of geographic coordinates which is used for road identification in this project. According to the official Google Maps Platform pricing documentation [36,37], the cost structure for the Nearest Roads endpoint requests is as follows.

Table A1.

The cost structure for the Nearest Roads endpoint requests.

Table A1.

The cost structure for the Nearest Roads endpoint requests.

| 0–5000 | 5–100 K | 100–500 K | 500 K–1 M | 1–5 M | 5 M+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free | USD 10 per 1 K requests | USD 8 per 1 K requests | USD 6 per 1 K requests | USD 3 per 1 K requests | USD 0.76 per 1 K requests |

For illustrative purposes, a system making 50,000 Nearest Roads queries in a month would consume the first 5000 requests at no cost and incur a charge for the remaining 45,000 requests at a rate of USD 10.00 per 1000. The total cost in this scenario would be USD 450.00.

Appendix C.2. Geocoding API

The Geocoding API is responsible for translating place identifiers or latitude/longitude coordinates into structured human-readable addresses. This service is crucial for presenting road data to users in a meaningful way. Its pricing tiers [36,37] are defined as follows.

Table A2.

The cost structure for the Geocoding API requests.

Table A2.

The cost structure for the Geocoding API requests.

| 0–5000 | 5–100 K | 100–500 K | 500 K–1 M | 1–5 M | 5 M+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free | USD 5 per 1 K requests | USD 4 per 1 K requests | USD 3 per 1 K requests | USD 1.50 per 1 K requests | USD 0.38 per 1 K requests |

As an example, a monthly usage of 25,000 requests would include 10,000 free calls. The remaining 15,000 requests would be billed at USD 5.00 per 1000, yielding a total cost of USD 75.00.

Appendix C.3. Monthly Cost Evaluation Projections

- Small-scale application:

- An application that makes approximately 2000 requests per month to each API falls entirely within the respective free usage tiers. Thus, the total cost incurred would be USD 0 per month.

- Mid-sized application:

- For a more resource-intensive application processing 100,000 requests per month for both APIs, the total estimated monthly cost is USD 1450:

- Roads API cost:

- (100,000 − 5000)/1000 × USD 10 = USD 950.

- Geocoding API cost:

- (100,000 − 10,000)/1000 × USD 5 = USD 450.

This cost model demonstrates that while Google Maps services are cost-effective at low volumes, usage at scale can result in substantial monthly expenditures, necessitating careful budgeting and optimization.

References

- Theodorou, P.; Tsiligkos, K.; Meliones, A.; Filios, C. An Extended Usability and UX Evaluation of a Mobile Application for the Navigation of Individuals with Blindness and Visual Impairments Outdoors—An Evaluation Framework Based on Training. Sensors 2022, 22, 4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The MANTO Project Webpage. Available online: https://manto.ds.unipi.gr (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Theodorou, P.; Meliones, A.; Filios, C. Smart traffic lights for people with visual impairments: A literature overview and a proposed implementation. Br. J. Vis. Impair. 2022, 41, 697–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meliones, A.; Filios, C.; Llorente, J. Reliable Ultrasonic Obstacle Recognition for Outdoor Blind Navigation. Technologies 2022, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lighthouse for the Blind of Greece. Available online: https://fte.gr/en/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Google Maps Platform. Available online: https://developers.google.com/maps (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- The BlindSquare Webpage. Available online: https://www.blindsquare.com (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- OpenStreetMap. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Chow, T.E. The Potential of Maps APIs for Internet GIS Applications. Trans. GIS 2008, 12, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Hsu, C.L. A location-based services and Google maps-based information master system for tour guiding. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2016, 54, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harja, Y.D.; Sarno, R. Determine the best option for nearest medical services using Google maps API, Haversine and TOPSIS algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Information and Communications Technology (ICOIACT), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 6–7 March 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 814–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robusto, C.C. The Cosine-Haversine Formula. Am. Math. Mon. 1957, 64, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meliones, A.; Maidonis, S. DALÍ: A Digital Assistant for the Elderly and Visually Impaired using Alexa Speech Interaction and TV Display. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM International Conference on Pervasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments, Corfu, Greece, 30 June–3 July 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Maps API, Geocoding API. Available online: https://developers.google.com/maps/documentation/geocoding/overview (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Google Maps API, Nearest Roads Library. Available online: https://developers.google.com/maps/documentation/roads/nearest (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Fathi, A.; Krumm, J. Detecting Road Intersections from GPS Traces. In Geographic Information Science; Fabrikant, S.I., Reichenbacher, T., van Kreveld, M., Schlieder, C., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 6292, pp. 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, X.; Sun, C.; Zheng, S.; Hu, B.; Varadarajan, J.; Yin, Y.; Zimmermann, R.; Wang, G. Sextant: Grab’s Scalable In-Memory Spatial Data Store for Real-Time K-Nearest Neighbour Search. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Mobile Data Management, Hong Kong, China, 10–13 June 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Philips, W. Road Intersection Detection through Finding Common Sub-Tracks between Pairwise GNSS Traces. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Sunderrajan, A.; Huang, X.; Varadarajan, J.; Wang, G.; Sahrawat, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zimmermann, R.; Ng, S.K. Multi-scale Graph Convolutional Network for Intersection Detection from GPS Trajectories. In Proceedings of the 3rd ACM SIGSPATIAL International Workshop on AI for Geographic Knowledge Discovery (GeoAI 20’19), Chicago, IL, USA, 5 November 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-taher, F.; Taha, A.; Courtney, J.; Mckeever, S. Using Satellite Images Datasets for Road Intersection Detection in Route Planning. Int. J. Comput. Syst. Eng. 2022, 16, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltaher, F.; Miralles-Pechuán, L.; Courtney, J.; Mckeever, S. Detecting Road Intersections from Satellite Images using Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 38th ACM/SIGAPP Symposium on Applied Computing (SAC’23), Tallinn, Estonia, 27–31 March 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, O.; Isik, M.S.; Sariturk, B.; Seker, D.Z. Generation of Istanbul road data set using Google Map API for deep learning-based segmentation. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43, 2793–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senousi, A.M.; Ahmed, W.; Liu, X.; Darwish, W. Automated Digitization Approach for Road Intersections Mapping: Leveraging Azimuth and Curve Detection from Geo-Spatial Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.H.K.; Berrio, J.S.; Shan, M.; Ming, Z.; Worrall, S. LiDAR-based Intersection Localization using Road Structure. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.00512v1. Available online: https://arxiv.org/html/2505.00512v1 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Tran, N.H.K.; Berrio, J.S.; Shan, M.; Worrall, S. InterKey: Cross-modal Intersection Keypoints for Global Localization on OpenStreetMap. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.13857v1. Available online: https://arxiv.org/html/2509.13857v1 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Bhatt, D.; Sodhi, D.; Pal, A.; Balasubramanian, V.; Krishna, M. Have i reached the intersection: A deep learning-based approach for intersection detection from monocular cameras. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 September 2017; pp. 4495–4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xiang, L.; Jiao, F.; Wu, H. Detecting Turning Relationships and Time Restrictions of OSM Road Intersections from Crowdsourced Trajectories. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Yu, X.; Wang, D.; Havyarimana, V.; Bai, T. Road Network Construction with Complex Intersections Based on Sparsely Sampled Private Car Trajectory Data. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2019, 13, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, G.; Shen, H.; Coughlan, J.M. Self-Localization at Street Intersections. In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer and Robot Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 6–9 May 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltaher, F.; Miralles-Pechuán, L.; Courtney, J.; Mckeever, S. SafeRoute: A Safer Outdoor Navigation Algorithm with Smart Routing for People with Visual Impairment. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Pervasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments (PETRA ’24), Crete, Greece, 26–28 June 2024; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, W.; Tikkun, S.R.; Thurman, J. IOT Solutions for Near Horizon Challenges in Smart City Pedestrian Travel (Task 2.3). North Carolina Central University, Project FHWA/NC/2020-60. August 2023. Available online: https://connect.ncdot.gov/projects/research/RNAProjDocs/IOT%20Solutions%20for%20Near%20Horizon%20Challenges%20in%20Smart%20City%20Pedestrian%20Travel%20final.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Jain, G.; Hindi, B.; Xie, M.; Zhang, Z.; Srinivasula, K.; Ghasemi, M.; Weiner, D.; Xu, X.; Paris, S.; Tedjo, C.; et al. Towards Street Camera-based Outdoor Navigation for Blind Pedestrians. In Proceedings of the 25th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers & Accessibility, New York, NY, USA, 22–25 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, B.; Angin, P.; Duan, L. A Mobile-Cloud Pedestrian Crossing Guide for the Blind, International Conference on Advances in Computing & Communication (ICACC-11), NIT Hamirpur. April 2011. Available online: https://www.cs.purdue.edu/homes/bb/pedestrian_crossing.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Rousell, A.; Zipf, A. Towards a Landmark-Based Pedestrian Navigation Service Using OSM Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, J.E.; Fiannaca, A.J.; Jaber, N.M.; Tsaran, V.; Kane, S.K. StreetViewAI: Making Street View Accessible Using Context-Aware Multimodal AI. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST ‘25), Busan, Republic of Korea, 28 September–1 October 2025; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Maps Platform Pricing. Available online: https://mapsplatform.google.com/pricing/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Google Maps Platform Pay-as-you-go. Available online: https://developers.google.com/maps/billing-and-pricing/pay-as-you-go (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Open Source Routing Machine (OSRM). Available online: https://project-osrm.org/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Prasetya, D.A.; Nguyen, P.T.; Faizullin, R.; Iswanto, I.; Armay, E.F. Resolving the Shortest Path Problem Using the Haversine Algorithm. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 62–64. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).