Comparative Analysis of Anthraquinone Reactive Dyes with Direct Dyes for Papermaking Applicability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

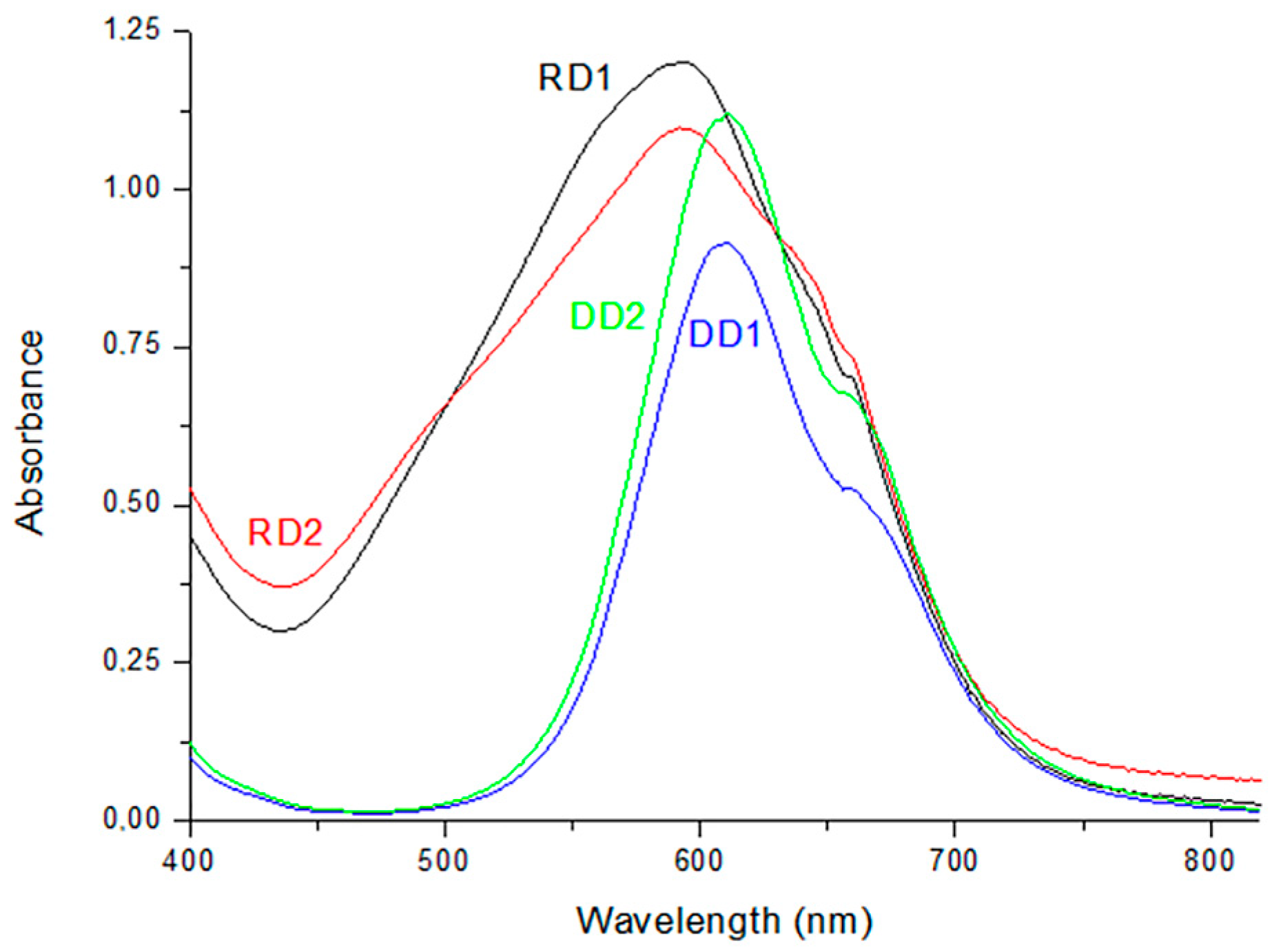

3. Results

3.1. Dyes’ Influence on Paper Slurries’ Characteristics

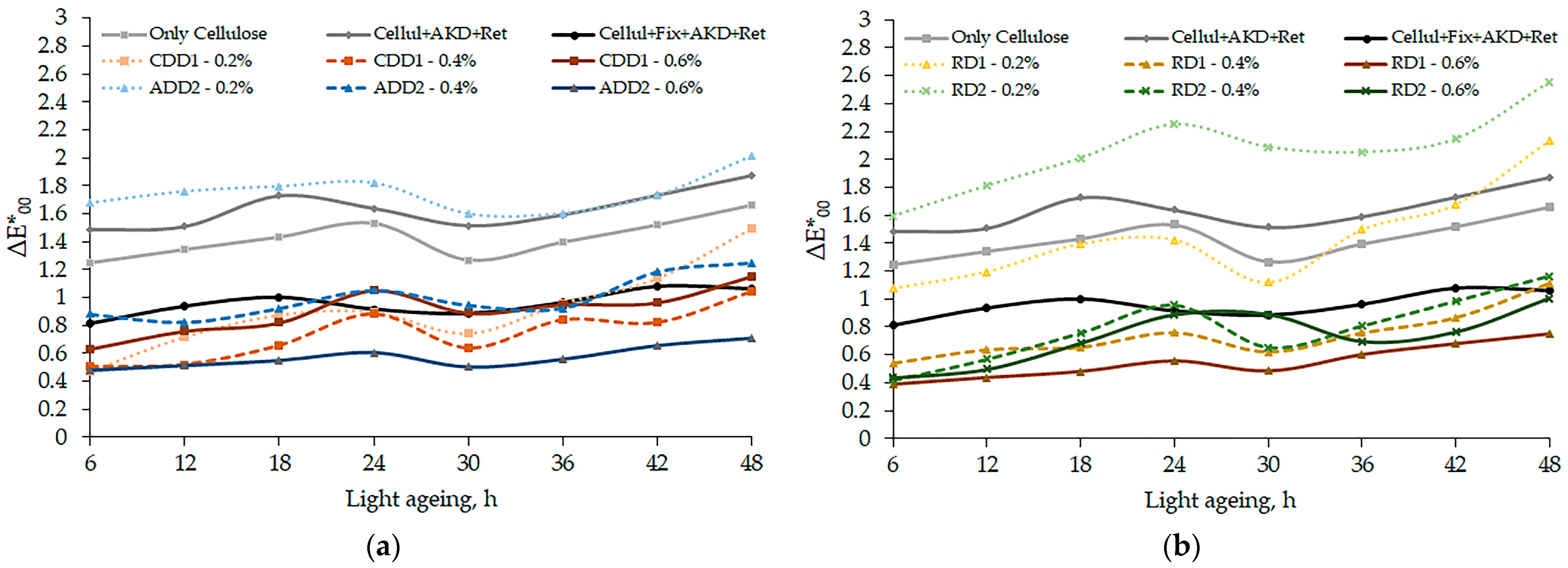

3.2. Dyes’ Influence on Paper Samples’ Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RD | Reactive dye |

| DD | Direct dye |

| AKD | Alkyl ketene dimer |

| Fix | Fixing additive |

| Ret | Retention additive |

| CDD1 | Cationic direct dye 1 |

| ADD2 | Anionic direct dye 2 |

References

- Preliminary Statistics 2024: European Pulp & Paper Industry. Confederation of European Paper Industries (Cepi) 2025. Available online: https://www.cepi.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/FINAL-Cepi-Preliminary-Statistics-2024.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Fu, S.; Farrell, M.J.; Hauser, P.J.; Hinks, D.; Jasper, W.J.; Ankeny, M.A. Real-time dyebath monitoring of reactive dyeing on cationized cotton for levelness control: Part 1–influence of dye structure, temperature, and addition of soda ash. Cellulose 2016, 23, 3319–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclow, B. Chapter 10 Paper Colouration. In Application of Wet-End Paper Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Thorn, I., Au, C.O., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.M. 13-Process control in dyeing of textiles. In Process Control in Textile Manufacturing; Majumdar, A., Das, A., Alagirusamy, R., Kothari, V.K., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Textiles; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 300–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xian, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, M.; Wang, Y.; Yu, D.; Wang, L. Properties of a new nitrogen- free additive as an alternative to urea and its application in reactive printing. Color. Technol. 2022, 138, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Wang, X.; Jiang, X.; Han, Q.; Jiang, F.; Zhu, X.; Xiong, C.; Ni, N. Role of nanocellulose in colored paper preparation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 206, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hou, A.; Xie, K.; Gao, A. Smart color-changing paper packaging sensors with pH sensitive chromophores based on azo-anthraquinone reactive dyes. Sens. Actuators B 2019, 286, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.J.; Tandel, R.C. Application of reactive dyes by dyeing and printing method on cotton fabric and study of antibacterial activity. Egypt. J. Chem. 2022, 65, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.M.; Broadbent, P.J.; Carr, C.M.; He, W.D. Investigation into the reaction of reactive dyes with carboxylate salts and the application of carboxylate- modified reactive dyes to cotton. Color. Technol. 2022, 138, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqua, U.H.; Ali, S.; Hussain, T.; Iqbal, M.; Masood, N.; Nazir, A. Application of multifunctional reactive dyes on the cotton fabric and conditions optimization by response surface methodology. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 1094–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sheikh, J. Novel combination of trisodium citrate and trisodium phosphate in reactive dyeing of cotton: An attempt to reduce environmental impact. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2021, 55, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senguttuvan, S.; Janaki, V.; Senthilkumar, P.; Kamala-Kannan, S. Polypyrrole/zeolite composite–A nanoadsorbent for reactive dyes removal from synthetic solution. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 132164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junejo, R.; Jalbani, N.; Kaya, S.; Serdaroglu, G.; Şimşek, S.; Memon, S. Experimental and DFT modeling studies for the adsorptive removal of reactive dyes from wastewater. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, B.; Abdollahzadeh-Sharghi, E.; Bonakdarpour, B. Anaerobic-aerobic processes for the treatment of textile dyeing wastewater containing three commercial reactive azo dyes: Effect of number of stages and bioreactor type. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 39, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.; Singh, S.S.J.; Rose, N.M. Optimization of reactive dyeing process for chitosan treated cotton fabric. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2022, 56, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, S.M.; Andrade, R.S.; Torres Chiari-Andreo, B.G.; Veloso, G.B.R.; Gonzalez, C.; Iglesias, M. Eco-friendly technology for reactive dyeing of cationized fabrics: Protic ionic liquids as innovative media. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2022, 56, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, N.; Govindan, N. Cotton cellulose modified with urea and its dyeability with reactive dyes. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2022, 54, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanaphol, M.; Klaichoi, C.; Rungruangkitkrai, N. Reactive dye printing on cotton fabric using modified starch of wild taro corms as a new thickening agent. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2021, 55, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Jamal, M.; Wang, R.; He, Q.; Sun, F.; Lin, H.; Su, X. Anaerobic biodegradation of anthraquinone dye reactive black 19 by a resuscitated strain Bacillus sp. JF4: Performance and pathway. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Pan, A.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, C.; Sun, F.; Su, X. A novel strategy for enhancing anaerobic biodegradation of an anthraquinone dye reactive blue 19 with resuscitation-promoting factors. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 127922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, J.; Wang, Q.; Zou, J.; Wang, K.; Xiao, H.; Huang, Z.; Rahaman, M.d.H.; Habineza, A. Decolorization of anthraquinone dye Reactive Blue 4 by natural manganese mineral. Desalin. Water Treat. 2017, 63, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Gao, B.; Fan, Z.; Li, M.; Hao, H.; Wei, X.; Zhong, M. Degradation of anthraquinone dye reactive blue 19 using persulfate activated with Fe/Mn modified biochar: Radical/non-radical mechanisms and fixed-bed reactor study. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 758, 143584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurti, S.; Racchi, O.; Spinoso, V.; Bussolari, A.; D’Altri, G.; Gualandi, I.; Di Maiolo, F.; Sissa, C.; Caretti, D. Symmetric azobenzene-substituted diketopyrrolopyrroles dyes as acid-base switchable molecular-probe for colorimetric paper-based sensors. Dye. Pigm. 2026, 245, 113288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharyya, S.; Sarkar, B.; Lekhashree, L.K.; Mukherji, S. Efficacious paper-based colorimetric detection of bacterial contamination in vegetables utilizing indicator dyes and machine learning. Food Chem. 2025, 495, 146408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Xia, X.; Luo, Y.; Men, D.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Hou, C.; Huo, D. Nanozyme and dye-driven paper-based sensor array: A novel convenient solution for crude baijiu quality discrimination. Food Chem. 2025, 492, 145504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinova, T.; Miladinova, P. Dyes and pigments with ecologically more tolerant application. In Dyes and Pigments-New Research; Lang, A.R., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 3, pp. 383–402. [Google Scholar]

- Małachowska, E.; Pawcenis, D.; Dańczak, J.; Paczkowska, J.; Przybysz, K. Paper Ageing: The Effect of Paper Chemical Composition on Hydrolysis and Oxidation. Polymers 2021, 13, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vibert, C.; Fayolle Ricard, D.; Dupont, A.-L. Decoupling hydrolysis and oxidation of cellulose in permanent paper aged under atmospheric conditions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 310, 120727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizáro-vá, K.; Kirschnerová, S.; Kačík, F.; Briškárová, A.; Šutý, S.; Katuščák, S. Relationship between the decrease of degree of polymerisation of cellulose and the loss of groundwood pulp paper mechanical properties during accelerated ageing. Chem. Pap. 2012, 66, 1124–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 5264-3:1979; Pulps—Laboratory Beating—Part 3: Jokro Mill Method. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 1979.

- ISO 5267-1/AC:2004; Pulps—Determination of Drainability—Part 1: Schopper-Riegler Method. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- ISO 5269-2:2005; Pulps—Preparation of Laboratory Sheets for Physical Testing—Part 2: Rapid-Köthen Method. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- ISO 7027-1:2016; Water Quality—Determination of Turbidity—Part 1: Quantitative Methods. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 7888:1985; Water Quality—Determination of Electrical Conductivity. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 1985.

- ISO 1924-2:2008; Paper and Board—Determination of Tensile Properties—Part 2: Constant Rate of Elongation Method (20 mm/min). International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- ISO 5630-7:2014; Paper and Board—Accelerated Ageing—Part 7: Exposure to Light. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO/CIE 11664-4:2019; ColorimetryPart 4: CIE 1976 L*a*b* colour space. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Commission Internationale de l’Éclairage (CIE). CIE 015:2018—Colorimetry, 4th ed.; CIE Technical Report; CIE: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecho, O.E.; Ghinea, R.; Alessandretti, R.; Pérez, M.M.; Della Bona, A. Visual and instrumental shade matching using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulas. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alava, M.; Niskanen, K. The physics of paper. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2006, 69, 669–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anovitz, L.M.; Cole, D.R. Characterization and analysis of porosity and pore structures. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2015, 80, 61–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbrecht, C.; Langhans, M.; Meckel, T.; Biesalski, M.; Schabel, S. Analyses of the effects of fiber diameter, fiber fibrillation, and fines content on the pore structure and capillary flow using laboratory sheets of regenerated fibers. Nord. Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2023, 38, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klanènik, M. Kinetics of hydrolysis of halogeno-s-triazine reactive dyes as a function of temperature. Chem. Biochem. Eng. Q. 2008, 22, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

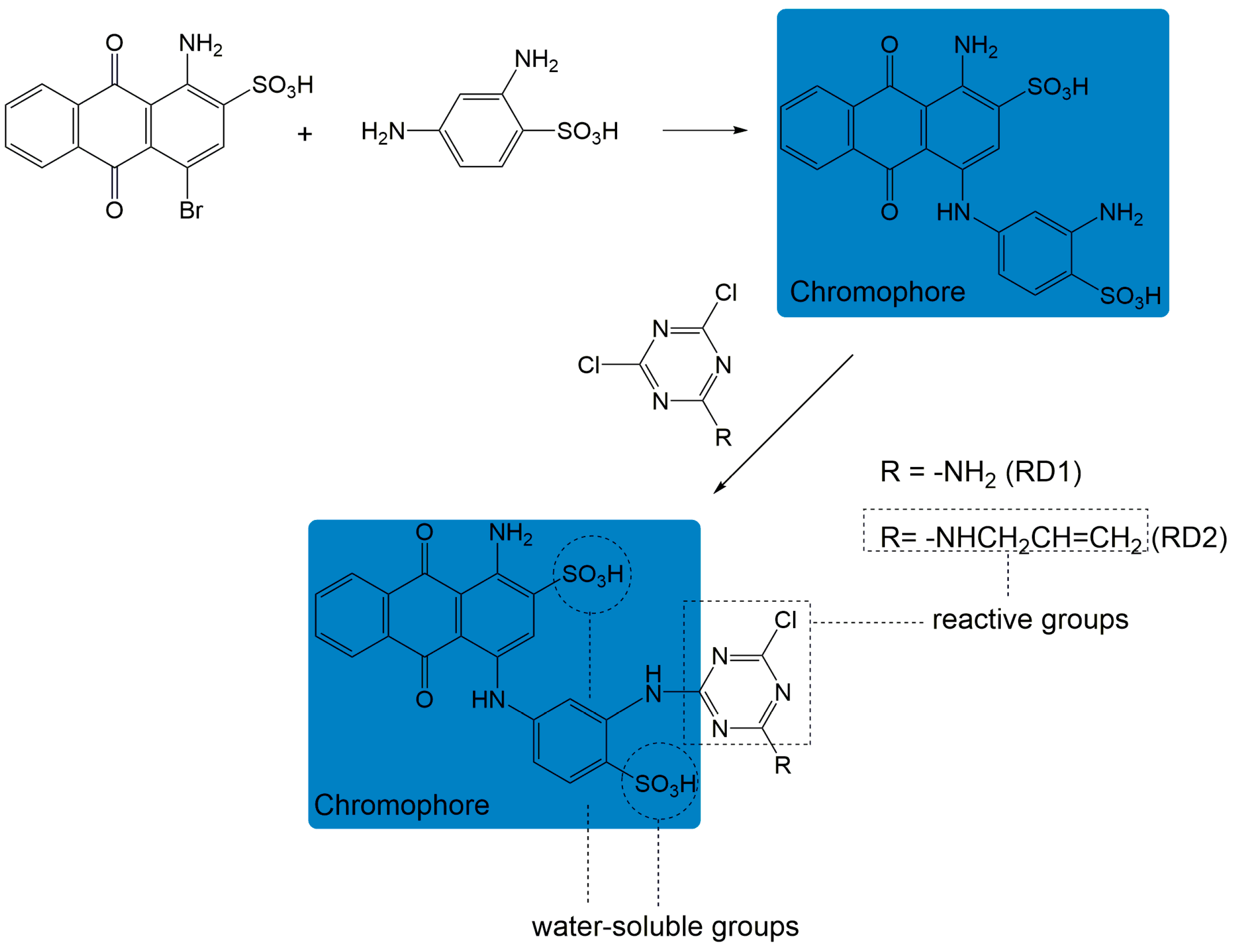

- Konstantinova, T.; Petrova, P. On the synthesis of some bifunctional reactive triazine dyes. Dye. Pigment. 2002, 52, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinova, T.; Miladinova, P. On the synthesis of some reactive triazine azodyes containing tetramethylpiperidine fragment. Dye. Pigment. 2005, 67, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miladinova, P.; Todorova, D. Synthesis, characterization, and application of new reactive triazine dye on cotton and paper. Fibers Polym. 2023, 23, 1614–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miladinova, P.; Todorova, D. synthesis and application of new homobifunctional reactive triazine dyes containing UV absorber. Fibers Polym. 2024, 6, 2245–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlert, M.; Benselfelt, T.; Wågberg, L.; Furó, I.; Berglund, L.A.; Wohlert, J. Cellulose and the role of hydrogen bonds: Not in charge of everything. Cellulose 2022, 29, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.R.; Arias, T.E.; García, M.R.B.; Escolano, A.; Hernández, N.G. Under the spotlight: A new tool (artificial light radiation) to bleach paper documents. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 52, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, R.L. Accelerated Aging: Photochemical and Thermal Aspects; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Area, M.C.; Cheradame, H. Paper aging and degradation: Recent findings and research methods. BioResources 2011, 6, 5307–5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, H. A review of accelerated test methods for predicting the image life of digitally-Printed photographs–Part II. In Proceedings of the IS&T’s NIP20: 2004 International Conference on Digital Printing Technologies, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 31 October–5 November 2004; Volume 20, pp. 664–669. [Google Scholar]

- Canle, L.M.; Ferna’ndez, M.I.; Santaballa, J.A. Developments in the mechanism of photodegradation of triazine-based pesticides. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2005, 18, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusic, H.; Koprivanac, N.; Loncaric Bozic, A. Environmental aspects on the photodegradation of reactive triazine dyes in aqueous media. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2013, 252, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Paper Slurries and White Water Properties | Paper Slurry with Added Direct Dyes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without Dye | Cationic DD1 | Anionic DD2 | |||||||

| Only Pulp | Pulp+AKD+ Ret | Pulp+Fix+ AKD+Ret | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.6% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.6% | |

| FV, mL | 430 | 430 | 443 | 420 | 453 | 415 | 425 | 430 | 443 |

| SI, % | 5.19 | 2.25 | 4.04 | 4.06 | 2.93 | 0 | |||

| T700, s | 17.35 | 13.25 | 17.55 | 12.02 | 11.82 | 11.83 | 14.73 | 12.25 | 12.55 |

| Dye concentration, % | - | - | - | 1.535 × 10−6 | 1.416 × 10−6 | 1.469 × 10−6 | 2.578 × 10−6 | 1.683 × 10−6 | 1.388 × 10−6 |

| Turbidity, NTU | 10.03 | 8.38 | 15.31 | 5.81 | 5.32 | 4.64 | 9.41 | 10.12 | 11.67 |

| Conductivity, µS | 123.3 | 123.2 | 129.1 | 124.5 | 125.5 | 125.5 | 123.7 | 124.3 | 130.7 |

| pH | 7.49 | 7.47 | 7.49 | 6.85 | 6.83 | 6.96 | 7.12 | 6.94 | 7.01 |

| Paper Slurries and White Water Properties | Paper Slurry with Added Reactive Dyes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without Dye | RD1 | RD2 | |||||||

| Only Pulp | Pulp+AKD+ Ret | Pulp+Fix+ AKD+Ret | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.6% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.6% | |

| FV, mL | 430 | 430 | 443 | 430 | 445 | 450 | 430 | 490 | 460 |

| SI, % | 2.93 | 0.45 | 1.58 | 2.93 | 10.61 | 3.84 | |||

| T700, s | 17.35 | 13.25 | 17.55 | 13.85 | 11.36 | 11.35 | 13.52 | 11.85 | 11.15 |

| Dye concentration, % | - | - | - | 1.653 × 10−6 | 1.733 × 10−6 | 2.347 × 10−6 | 1.845 × 10−6 | 1.824 × 10−6 | 1.806 × 10−6 |

| Turbidity, NTU | 10.03 | 8.38 | 15.31 | 10.46 | 7.89 | 5.88 | 12.51 | 8.03 | 7.39 |

| Conductivity, µS | 123.3 | 123.2 | 129.1 | 129.7 | 133.2 | 136.2 | 131.5 | 132.5 | 134.1 |

| pH | 7.49 | 7.47 | 7.49 | 7.11 | 7.15 | 7.15 | 7.2 | 7.18 | 7.12 |

| Light Aging, Hours | Only Cellulose | Cellul+AKD+Ret | Cellul+Fix+AKD+Ret | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | L* | a* | b* | L* | a* | b* | |

| 0 | 92.95 | −0.82 | 5.82 | 92.3 | −0.83 | 6.24 | 91.66 | −0.53 | 10.28 |

| 6 | 93.23 | −0.28 | 7.03 | 92.67 | −0.22 | 7.76 | 91.00 | −0.01 | 10.35 |

| 12 | 93.11 | −0.23 | 7.13 | 92.57 | −0.19 | 7.77 | 90.91 | 0.07 | 10.42 |

| 18 | 93.03 | −0.22 | 7.27 | 92.47 | −0.18 | 8.13 | 90.80 | 0.07 | 10.65 |

| 24 | 93.03 | −0.26 | 7.48 | 92.47 | −0.21 | 8.02 | 90.87 | 0.04 | 10.42 |

| 30 | 93.18 | −0.24 | 7.01 | 92.58 | −0.19 | 7.78 | 90.91 | 0.03 | 10.25 |

| 36 | 93.01 | −0.20 | 7.18 | 92.46 | −0.16 | 7.88 | 90.85 | 0.08 | 10.19 |

| 42 | 92.93 | −0.21 | 7.40 | 92.39 | −0.14 | 8.09 | 90.72 | 0.14 | 10.45 |

| 48 | 92.95 | −0.23 | 7.65 | 92.37 | −0.14 | 8.32 | 90.76 | 0.12 | 10.61 |

| Light Aging, Hours | CDD1–0.2% | CDD1–0.4% | CDD1–0.6% | ADD2–0.2% | ADD2–0.4% | ADD2–0.6% | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | L* | a* | b* | L* | a* | b* | L* | a* | b* | L* | a* | b* | L* | a* | b* | |

| 0 | 81.44 | −20.33 | −9.32 | 76.86 | −25.18 | −15.01 | 73.55 | −27.43 | −18.95 | 82.73 | −17.05 | −8.05 | 79.93 | −19.3 | −12.29 | 75.02 | −23.53 | −14.54 |

| 6 | 81.60 | −20.31 | −8.65 | 76.97 | −24.64 | −14.15 | 73.72 | −26.81 | −17.75 | 82.92 | −16.01 | −5.72 | 80.36 | −18.92 | −10.95 | 74.87 | −22.80 | −13.85 |

| 12 | 81.69 | −19.96 | −8.27 | 76.92 | −24.60 | −14.12 | 73.78 | −26.68 | −17.52 | 82.94 | −15.87 | −5.63 | 80.31 | −18.97 | −11.03 | 74.89 | −22.78 | −13.77 |

| 18 | 81.72 | −19.80 | −8.04 | 76.98 | −24.48 | −13.89 | 73.80 | −26.64 | −17.41 | 82.92 | −15.85 | −5.58 | 80.33 | −18.90 | −10.87 | 74.86 | −22.71 | −13.74 |

| 24 | 81.75 | −19.75 | −8.02 | 77.07 | −24.30 | −13.51 | 73.83 | −26.48 | −16.97 | 82.96 | −15.87 | −5.54 | 80.37 | −18.87 | −10.67 | 74.84 | −22.71 | −13.61 |

| 30 | 81.75 | −19.91 | −8.25 | 77.05 | −24.49 | −13.94 | 73.79 | −26.58 | −17.27 | 82.98 | −15.94 | −5.86 | 80.41 | −18.80 | −10.86 | 74.81 | −22.83 | −13.80 |

| 36 | 81.79 | −19.73 | −7.93 | 77.14 | −24.30 | −13.61 | 73.83 | −26.50 | −17.17 | 82.98 | −15.89 | −5.87 | 80.37 | −18.84 | −10.88 | 74.83 | −22.71 | −13.73 |

| 42 | 81.84 | −19.58 | −7.68 | 77.14 | −24.29 | −13.65 | 73.84 | −26.54 | −17.14 | 82.96 | −15.81 | −5.69 | 80.37 | −18.67 | −10.45 | 74.81 | −22.67 | −13.53 |

| 48 | 82.01 | −19.05 | −7.25 | 77.22 | −24.05 | −13.29 | 74.00 | −26.32 | −16.84 | 82.91 | −15.78 | −5.27 | 80.25 | −18.75 | −10.32 | 74.79 | −22.71 | −13.41 |

| Light Aging, Hours | RD1–0.2% | RD1–0.4% | RD1–0.6% | RD2–0.2% | RD2–0.4% | RD2–0.6% | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | L* | a* | b* | L* | a* | b* | L* | a* | b* | L* | a* | b* | L* | a* | b* | |

| 0 | 76.59 | −2.59 | −6.32 | 69.56 | −1.57 | −11.35 | 65.27 | −0.84 | −13.55 | 76.34 | −2.94 | −7.22 | 71.28 | −2.52 | −10.74 | 65.82 | −1.96 | −13.45 |

| 6 | 77.30 | −2.21 | −5.22 | 69.63 | −1.16 | −11.01 | 65.22 | −0.54 | −13.33 | 77.49 | −2.71 | −5.46 | 71.20 | −2.33 | −10.19 | 65.94 | −1.80 | −12.81 |

| 12 | 77.36 | −2.17 | −5.09 | 69.60 | −1.10 | −10.89 | 65.25 | −0.51 | −13.26 | 77.53 | −2.61 | −5.18 | 71.21 | −2.26 | −9.99 | 65.90 | −1.75 | −12.73 |

| 18 | 77.38 | −2.10 | −4.84 | 69.63 | −1.09 | −10.87 | 65.28 | −0.51 | −13.11 | 77.57 | −2.55 | −4.93 | 71.29 | −2.19 | −9.73 | 66.02 | −1.73 | −12.45 |

| 24 | 77.38 | −2.07 | −4.82 | 69.67 | −1.06 | −10.66 | 65.28 | −0.49 | −12.96 | 77.69 | −2.42 | −4.68 | 71.35 | −2.10 | −9.48 | 66.07 | −1.63 | −12.18 |

| 30 | 77.28 | −2.15 | −5.19 | 69.63 | −1.09 | −11.01 | 65.14 | −0.50 | −13.17 | 77.61 | −2.44 | −4.87 | 71.21 | −2.15 | −9.96 | 66.02 | −1.62 | −12.17 |

| 36 | 77.43 | −2.04 | −4.75 | 69.62 | −1.01 | −10.82 | 65.15 | −0.43 | −13.02 | 77.55 | −2.43 | −4.90 | 71.25 | −2.12 | −9.71 | 65.98 | −1.66 | −12.47 |

| 42 | 77.48 | −1.96 | −4.56 | 69.76 | −1.02 | −10.51 | 65.23 | −0.40 | −12.87 | 77.57 | −2.41 | −4.78 | 71.27 | −1.98 | −9.55 | 65.97 | −1.62 | −12.38 |

| 48 | 77.63 | −1.86 | −4.02 | 69.79 | −0.95 | −10.11 | 65.24 | −0.38 | −12.74 | 77.68 | −2.24 | −4.32 | 71.40 | −1.97 | −9.29 | 66.12 | −1.53 | −12.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Todorova, D.; Miladinova, P.; Katevska, B. Comparative Analysis of Anthraquinone Reactive Dyes with Direct Dyes for Papermaking Applicability. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13216. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413216

Todorova D, Miladinova P, Katevska B. Comparative Analysis of Anthraquinone Reactive Dyes with Direct Dyes for Papermaking Applicability. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13216. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413216

Chicago/Turabian StyleTodorova, Dimitrina, Polya Miladinova, and Blagovesta Katevska. 2025. "Comparative Analysis of Anthraquinone Reactive Dyes with Direct Dyes for Papermaking Applicability" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13216. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413216

APA StyleTodorova, D., Miladinova, P., & Katevska, B. (2025). Comparative Analysis of Anthraquinone Reactive Dyes with Direct Dyes for Papermaking Applicability. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13216. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413216