Abstract

Abdominal muscles play a crucial role in spinal stability which may be altered by muscular fatigue. To assess the extent of current fatigue, subjective and objective parameters can be used. The aim of the present study was to investigate whether different perceived exertion levels correspond with changes in fatigue-associated electrophysiological parameters of abdominal muscles. For this, 34 healthy participants (17 women) underwent a 10 min static endurance task of their abdominal muscles at 50% upper body weight. Every elapsed minute, perceived exertion was assessed together with changes in electro-physiological parameters. Based on the perceived exertion levels, participants were divided into a “good end” and a “bad end” group. Independent of group, muscular fatigue was identified in all abdominal muscles. In the rectus abdominis muscle this was most pronounced, with different levels between groups and satisfactory correlations between perceived exertion levels and electrophysiological parameters. Thus, electrophysiological signs of fatigue and RPE levels are interchangeable for the rectus abdominis. In contrast and therefore of utmost importance, fatigue of the oblique abdominal muscles is largely unrelated to perceived exertion. Given the key role of these muscles in maintaining trunk stability, prolonged submaximal loads appear to affect their function regardless of mild or intense exertion level.

1. Introduction

It has been demonstrated in various studies that the abdominal muscles contribute to spinal stabilization [1,2,3,4,5]. In particular, the intra-abdominal pressure generated by these muscles plays a crucial role [6,7]. Not only the magnitude of this pressure but also the appropriate timing of its development is of critical importance [8,9,10,11]. The concept of spinal stabilization is based on this premise [12,13,14]. Consequently, effective approaches for treating back pain always incorporate the entire trunk musculature rather than focusing solely on the back muscles [15].

Conversely, this implies that the abdominal muscles are engaged even in situations that primarily load the back. Vulnerable situations may arise when external perturbations affect weakened or unprepared trunk muscles [16]. In addition to morphological weaknesses caused, for example, by deconditioning [17], a functional and thus temporarily reversible loss of strength can also occur. Besides coordinative deficits [18], muscular fatigue is the most likely factor responsible for this condition [19,20,21].

Any relevant physical exertion [22] will lead to fatigue if sustained for a sufficiently long duration without adequate recovery. From a biomechanical perspective, fatigue resulting from prior physical activity manifests as a reduction in maximal force output [23]. During typical submaximal exertion, this leads to a continuous increase in perceived exertion over time until it eventually reaches an individual’s maximum, even when the external load remains constant [24]. If the exertion persists beyond this point, physical failure ensues.

A characteristic feature of this reversible fatigue process in the submaximal load range is the increasing recruitment of motor units [25]. As exertion continues, recruitment initially occurs in the slow-contracting type I fibers and gradually shifts to the fast-contracting type II fibers until maximum activation is eventually reached [26].

The energy deficit not only leads to a reduction in force-generating capacity but also affects the cell membrane. This causes a progressive slowing of the depolarization wave triggered by synaptic activation [25,26,27]. Both effects can be detected using electromyography (EMG), where the EMG signal is characterized by an increase in amplitude and a decrease in frequency. This fundamental relationship was described in 1996 by Luttmann and colleagues in the so-called JASA model (Joint Analysis of Spectrum and Amplitude [28]).

Muscular fatigue processes are by no means exclusively peripheral in origin or limited to the periphery. Instead, a distinction is made between central and peripheral fatigue [23]. Central fatigue is primarily characterized by a reduced firing rate of motor units, which in turn leads to a decrease in generated force. The differentiation between central and peripheral fatigue can be achieved through instrumental methods by applying supramaximal electrical stimulation to the affected areas—if such a stimulation results in an increase in force, it indicates the presence of central fatigue [23].

In practice, however, such methods are often only partially applicable or not feasible at all. Nevertheless, indications of at least partial central fatigue can be inferred if intrinsic factors, such as autosuggestion, or extrinsic stimuli, such as verbal encouragement, lead to at least temporary improvements in motor function.

Without electrophysiological assessments, the evaluation of fatigue ultimately remains subjective. For this, scales of ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) are applied [29,30,31]. However, it remains uncertain whether these subjective assessments actually align with or correlate with established fatigue-associated electrophysiological parameters such as amplitude and frequency.

Previously published findings regarding both the abdominal and back muscles have demonstrated that, based on initial RPE values, a high predictive validity could be proven for the abdominal muscles, whereas this was not the case for the back muscles under investigation [32]. These results were unexpected, given that endurance loading of the back musculature occurs frequently and is therefore assumed to be familiar and, accordingly, well assessable. However, analyses of changes in electrophysiological parameters were not conducted in that context. While various studies have examined the endurance capacity of the back muscles [33,34], we were unable to identify investigations that included RPE assessments in parallel. Nevertheless, there is evidence suggesting that the endurance capacity of the abdominal muscles, in particular, is significantly influenced by psychosocial rather than physical factors [35]. The critical role of adequate functionality of the abdominal muscles—especially in relation to back pain—is well established [36]. Accordingly, an accurate assessment of the functional status of the abdominal musculature is of considerable importance.

The actual study wanted to address this particularly, i.e., to analyze if and how strong ratings of perceived exertion correlate with electrophysiological signs of fatigue during a time-limited isometric submaximal endurance task of the abdominal muscles. Further, the study also wanted to analyze if particularly high or low RPE levels are accompanied by respective differences in fatigue-related changes in electrophysiological parameters.

We hypothesize that subjective estimations of perceived exertion reliably reflect the objectively measurable fatigue of the abdominal muscles and are therefore suitable as a substitute for evaluating load during static flexion tasks. Furthermore, different RPE levels should be associated with distinguishable differences in the fatigue levels of all abdominal muscles.

2. Methods

For this study, a total of 40 healthy control participants (20 women) aged between 25 and 52 years (mean age: 37.7 ± 9.0 years) were recruited. Inclusion criteria required written informed consent, an age between 20 and 55 years, a physically active lifestyle, and the absence of chronic musculoskeletal or neurological disorders. The study protocol was submitted to and approved by the Ethics Committee of Friedrich Schiller University Jena (2021-2373_1-BO) and is therefore in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki in its actual version. The actual analysis shows partial results of a larger study.

Of the 40 recruited participants, 6 had to terminate the trial prematurely due to exhaustion, leaving 34 participants for the final analysis. Anthropometric data of the investigated population were determined and are provided in Table 1. We also determined the upper body weight and isometric maximum flexion force of each participant. This was used to calculate the ratio between both measures and is called upper body torque ratio (UBTR). Maximum flexion force was detected in the untilted device (i.e., in upright body posture). For this, subjects were asked to produce maximum isometric force against a force attachment, positioned over the subject’s shoulder (refer to Figure 1, but not tilted). They were asked to provide three attempts, while the first one was used as a familiarization task. The two remaining tasks were maximum flexion tasks, of which the one with the largest force value was selected. Verbal encouragement was provided [37].

Table 1.

Anthropometric and force related data of the investigated population together with defined subgroups according to sex and RPE levels.

Figure 1.

Subject during the endurance test in the CTT Centaur.

2.1. Procedure

Participants were subjected to a 10 min static endurance load at 50% of their upper body weight (UBW) by being tilted backward while standing in an upright position. For this purpose, they were secured from the hips downward in a computer-assisted test and training device (CTT Centaur, BfmC, Leipzig, Germany), while the upper body remained unrestrained and free to move. The device was equipped with a force attachment positioned over the shoulders. Contact with this attachment resulted in a displacement of the target point in a crosshair displayed on a screen, which was positioned directly within the participants’ field of view (Figure 1). This is similar to other investigations in which back muscles have been investigated [38].

The CTT Centaur allows for adjustable tilt angles between 0° and 90°, exposing participants to Earth’s gravitational field without requiring active flexion or extension movements. For this study, a tilt angle of 30° was used, corresponding to a load of 50% UBW. The participants’ task was to maintain an upright posture throughout the 10 min trial without leaning against the force attachment. Compliance with the correct posture was monitored via the aforementioned display.

2.2. Measured Data and Analysis

Perceived exertion was measured using the established 15-point Borg scale (range 6–20; [39]). Ratings were questioned every elapsed minute, resulting in ten ratings per participant.

To objectively assess muscular fatigue, sEMG was simultaneously recorded from three abdominal muscles on both sides: the rectus abdominis (RA), the internal oblique abdominis (OI), and the external oblique abdominis (OE) muscles. Skin preparation and electrode positioning followed the guidelines of SENIAM and those provided by Ng et al. [40]. For sEMG recording, wireless bipolar amplifiers (Cometa S.r.l., Bareggio, Italy) were used, with a frequency range of 10–500 Hz (sampling rate: 2000/s, resolution: 16 bit (±2.5 mV), CMRR 120 dB, SNR 50 dB).

The sEMG data were first cleaned of physiological artifacts (heart activity: template algorithm [41]). Data quantification was performed as a sliding root mean square (rms) with a window width of 256 ms. Further, the data were cleaned of technical or non-physiological artifacts by fitting a third-order polynomial to the rms signal. This polynomial was subtracted from the original signal, and values with deviations greater than ±2 SD were set to zero. This procedure was then repeated with a threshold of ±3 SD. Subsequently, the polynomial was re-added, restoring the original values while replacing artifacts with the polynomially estimated values. This approach allowed the avoidance of data gaps due to non-physiological disturbances.

Corresponding to the RPE ratings after each completed minute, the mean rms, mean frequency (MF), FInsm2, and FInsm5 [42] values were calculated within a ±3 s window around the respective time point. This particular time window was chosen as a compromise between seeking enough data points to be representative and the desired steadiness of data to be used in the statistical calculations. The relative change in these values compared to the baseline was used as the respective parameter for further analysis. As the investigation involved a static endurance task, we did not apply other parameters to identify muscular fatigue which are especially suited for dynamic tasks [43,44,45].

As already mentioned, in addition to analyzing amplitude and mean frequency, we also incorporated the relatively novel Fatigue Index proposed by Dimitrov [41]. This index reflects fatigue-associated changes in the power spectrum of sEMG signals. As the authors suggest, the range of variation in the index increases with higher values of k (a weighting factor); we specifically conducted our analyses for k = 2 and k = 5 to capture potential differences.

Correlations between the unlimited changes in the sEMG parameters and the 15-point Borg scale, especially in the extreme ranges of high exertion, are problematic, as a ceiling effect may occur, leading to negatively distorted values. This accounts for the bad end group, as in some cases the maximum rating of 20 already was reached before task completion. Therefore, to particularly address this issue, and also to detect if different exertion levels are accompanied by different electrophysiological signs of fatigue, we formed two subgroups based on subjective exertion levels: one with particularly low (n = 10) and one with high (n = 9) perceived exertion. The 10 min static load generated considerable exertion, with participants reporting values above 14 (hard) on the Borg scale at the end of the trial. Participants who reported RPE values < 17 (very hard) after the 10 min static endurance task were assigned to the “good end.” A total of nine participants reported the maximum value of 20 (very, very hard) after the 10 min and were therefore assigned to the “bad end” (for group characteristics see Table 1). The remaining group with values between these extremes was deliberately not included in order to achieve a clear separation between the extreme groups.

2.3. Statistics

The change values (as relative differences from baseline) of the aforementioned parameters (rms, MF, FInsm2, and FInsm5) were compared between the two subgroups for each minute elapsed muscle by muscle. Since normal distribution could not be confirmed for the data, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test for independent samples was applied as the statistical test. To account for the effects of multiple comparisons at the repeated time points for each full minute, the results were Bonferroni-Holm corrected [46] separately per parameter and muscle. Additionally, the respective effect sizes are reported. Values ≥ 0.5 are considered large effects [47].

Correlations between RPE ratings and the electrophysiological parameters were calculated as Spearman correlations for all participants and also separately for both groups. These results will be shown as r values together with their 95% CI Intervals to directly display the explained variability [48].

3. Results

Correlations between electrophysiological parameters and the RPE ratings for all subjects were strong (r > 0.5) except for FInsm5 in the oblique abdominal muscles, indicating good agreement between RPE and electrophysiological parameters. However, analyses per group revealed generally lower correlations in the good end group, whereas in the bad end group correlations were even stronger than for the whole group (Table 2). In addition, correlations differed between muscles: for rectus abdominis frequency-based correlations were superior, whereas in the oblique abdominal muscles amplitude-based correlations showed best results.

Table 2.

Spearman’s correlations between RPE ratings and electrophysiological parameters.

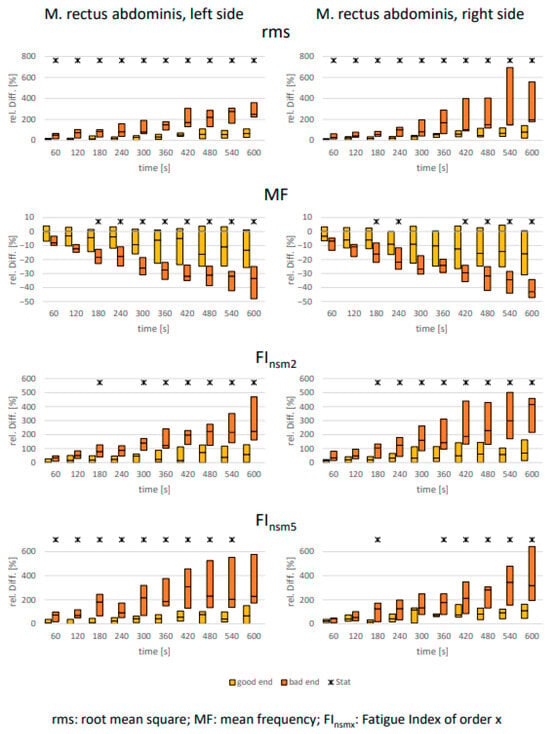

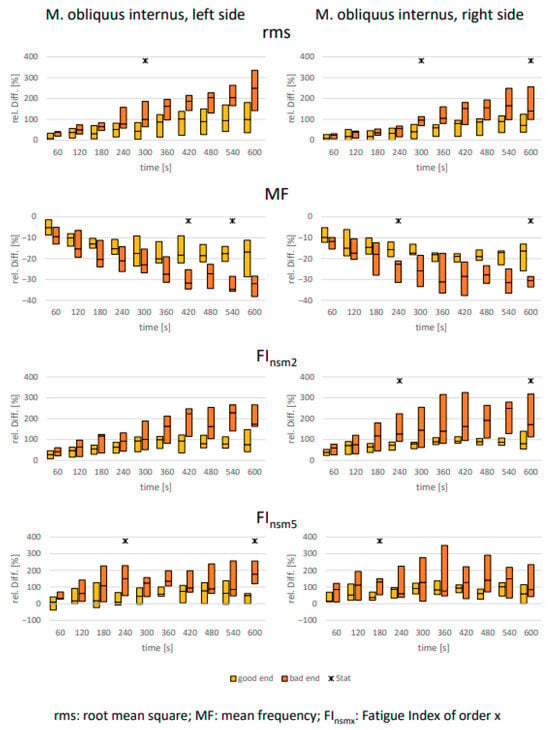

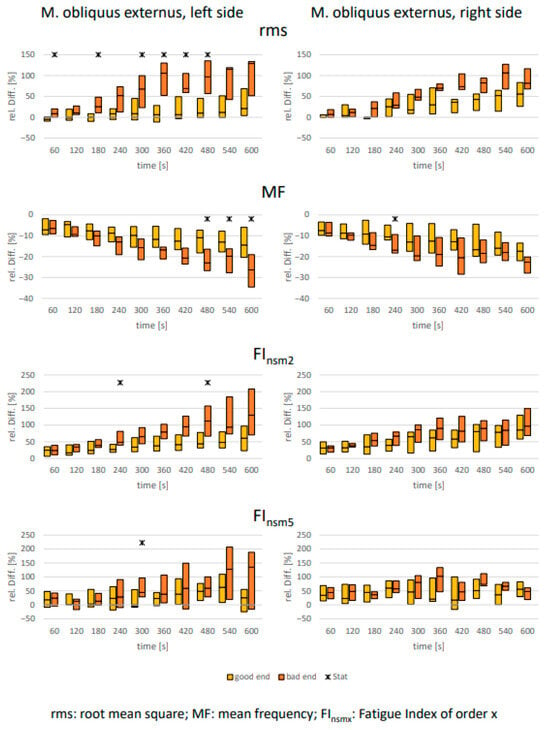

As expected, clear signs of muscular fatigue were observed for all abdominal muscles in all analyzed parameters over the 10 min holding period (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4). However, differences between the defined “good end” and “bad end” groups for the changes in fatigue-associated electrophysiological parameters were consistently detectable only for the rectus abdominis. For the two oblique abdominal muscles, only sporadic significant differences between the groups with differently perceived exertion were observed. This was true not only for the statistical tests but also equally applicable to the calculated effect sizes (Table 3).

Figure 2.

M. rectus abdominis: Comparison of electrophysiological relative changes between “good end” and “bad end” based on the Borg scale during a 10 min static endurance test of the abdominal muscles at 50% of the upper body weight (UBW). The values are presented as median ± upper and lower quartile range. Asterisks denote significant differences between the groups with p < 0.05 (U-test, Bonferroni–Holm corrected [46]).

Figure 3.

M. obliquus internus: Comparison of electrophysiological relative changes between “good end” and “bad end” based on the Borg scale during a 10 min static endurance test of the abdominal muscles at 50% of the upper body weight (UBW). The values are presented as median ± upper and lower quartile range. Asterisks denote significant differences between the groups with p < 0.05 (U-test, Bonferroni–Holm corrected [46]).

Figure 4.

M. obliquus externus: Comparison of electrophysiological relative changes between “good end” and “bad end” based on the Borg scale during a 10 min static endurance test of the abdominal muscles at 50% of the upper body weight (UBW). The values are presented as median ± upper and lower quartile range. Asterisks denote significant differences between the groups with p < 0.05 (U-test, Bonferroni–Holm corrected [46]).

Table 3.

Effect sizes for comparing electrophysiological change parameters between “good end” and “bad end” based on the Borg scale during a 10 min static endurance test of the abdominal muscles at 50% of the upper body weight. Fields containing values > 0.5 colored green.

Between both groups no significant nor relevant differences in anthropometric data could be proven, but maximum relative upper body force was significantly higher in the good end group (good end: 1.61, (SD ± 0.18), bad end: 1.43 (SD ± 0.19), relative difference: 11.2%; Table 1).

4. Discussion

The applied load was capable of inducing a relevant fatigue situation for the examined abdominal muscles. This was clearly demonstrated by the RPE levels (values > 14) and the analyzed electrophysiological parameters. Therefore, all parameters are suitable for identifying muscular fatigue.

Across the entire sample, and particularly within the “bad end” subgroup, a notably stronger correlation with RPE values was identified compared to the “good end” group. Although the latter also exhibited a clear increase in perceived exertion, the corresponding changes in electrophysiological parameters were less pronounced—albeit still substantial in magnitude.

The relatively strong correlation coefficients observed in the bad end group were unexpected, as the ceiling effect would typically lead to attenuated associations. This finding implies that individuals reporting particularly high RPE scores tend to exhibit notably pronounced electrophysiological indicators of fatigue.

Another observation warrants further discussion: for the rectus abdominis, correlations consistently showed the strongest values for the relationship between frequency-based sEMG parameters and ratings of perceived exertion (RPE). This pattern was not observed for the oblique abdominal muscles, where the strongest correlations were predominantly found between amplitude values and RPE. These findings are in good agreement with the results reported by Cruz-Montecinos and colleagues [49], who demonstrated similar correlation patterns.

Surprisingly, the FInsm5 did not demonstrate convincing results in any of the correlations and consistently exhibited the weakest values across all analyses. For the oblique abdominal muscles in particular, the correlations dropped to an irrelevant level. Accordingly, the FInsm5 appears to be unsuitable for identifying fatigue-related behavior in the abdominal muscles.

However, the differentiation between the two groups with different RPE levels was only clearly achievable for the rectus abdominis (RA). While side differences were observed, the differentiation was consistently possible across all parameters equally (with strongest correlations with RPE for MF). This was also reflected in the calculated effect sizes, which predominantly reached values > 0.5, indicating large effects [47].

The cause of this differing change behavior could lie in the significantly different fiber composition between abdominal and back muscles. For the back muscles, a Type I fiber proportion of approximately 62–68% can be assumed [50,51], which corresponds with a cross-sectional area (CSA) of 66% (women) and 73% (men) [50]. The Type I fiber proportion in the abdominal muscles, particularly the RA, is considerably lower: here, the proportion is approximately 55–58% [52], with an estimated CSA of about 54% [52]. This means that the functional Type II fiber area is significantly larger in the abdominal muscles than in the back muscles. As a result, abdominal muscles fatigue more quickly. This likely requires a much stronger recruitment of additional motor units to compensate for the load. This is accompanied by changes, especially in the amplitude characteristics, as observed here [53,54].

The increase in the amplitude of the EMG interference pattern, i.e., the measured sEMG amplitude during muscular fatigue, is also attributed to the fatigue-induced prolongation of the action potential of the muscle fibers [55,56].

However, it is important to note that no systematic differences for the Electromyographic parameters between the extreme groups of differently perceived exertion were detectable for the two oblique abdominal muscles. One initial consideration could be the fact that even the “good end” group already had RPE values > 14. The 15-point Borg scale [39] has a range from 6 to 20. Thus, the applied load already led to considerable exertion. It should be discussed whether the difference between the “good end” and the “bad end” group was too small for differentiation. However, this assumption is contradicted by the fact that corresponding differences were detectable for the RA.

Another possible reason for this could be that the two oblique abdominal muscles were not loaded in their primary force direction during the applied sagittal load [57]. This direction is approximately 32° laterally rotated for the OE. For the OI, the lateral deviation is even about 45° [57]. Therefore, the perceived exertion may primarily result from the fatigue behavior of the RA. Nevertheless, both oblique abdominal muscles also fatigued considerably. This (i.e., fatigue) is accompanied by a change in force production capacity [58] and a prolonged reaction time [59]. These fatigue-induced changes occur regardless of whether the person belongs to the “good end” or the “bad end” group of perceived exertion. Therefore, both oblique abdominal muscles show comparable fatigue-related changes.

As already mentioned, the actual results are supported by the investigation of Cruz-Montecinos and colleagues [49] who found good correlations between neuromuscular fatigue and RPE ratings in the rectus abdominis muscle but not for both oblique abdominal muscles. Although they performed the test until exhaustion, the similarities between results are remarkable. Thus, the actual investigation could be expanded towards the finding that in less strained subjects there is an only weak correlation between strain level and objectively detectable signs of fatigue in the oblique abdominal muscles.

This finding is significant because the role of both oblique abdominal muscles in generating the intra-abdominal pressure is anatomically much more important than that of the RA [60]. Thus, both little and highly fatigued individuals seem to experience similar fatigue-related functional changes in trunk stability [61,62]. Therefore, it cannot be assumed that less fatigued individuals have better trunk stability than those who are more fatigued. Quite clearly, the RA is primarily responsible for the perceived level of exertion.

Theoretically, an explanation for the interaction between the “good end” and “bad end” groups could arise from anthropometric data or data related to strength performance. As can be taken from Table 1, the anthropometry did not show any relevant difference. But a significant difference of about 11% in favor of the good end group could be proven for the upper body torque ratio. In this regard, it has to be stated that the found upper body torque ratio even of the bad end is somewhat superior to what was measured earlier in healthy but physically inactive subjects [63]. Unfortunately, we were unable to find any article that examined the relationship between maximum flexion force capacity and abdominal muscle endurance.

Although the UBTR is a meaningful parameter due to its anthropometric normalization, there are currently no established normative values available that would allow for a clear interpretation of these findings. Previously published data from our group [64,65] reported UBTR values that were even slightly higher than those observed in the good end group for both women (1.52–1.59) and men (1.94–1.95). However, other published data on back muscles from our group indicate that solely strength-focused training can have the opposite effect, impairing muscular endurance capacity [38,63,66]. Whether this finding can be directly transferred to the abdominal muscles remains uncertain.

Gender distribution showed no significant imbalance between the groups (“good end” group: 4 women, “bad end” group: 4 women) and can thereby be excluded as a biasing factor.

In summary, the presented results, both for the entire group and for the defined subgroups [39], showed consistently high correlations between perceived exertion and fatigue-related changes in electrophysiological parameters exclusively for the M. rectus abdominis. At the same time, only this muscle demonstrated consistently distinct variations in these objective fatigue-associated changes between the extreme RPE subgroups. Thus, the RPE level most accurately reflects the fatigue behavior of this muscle during untwisted flexion loading. The extent of fatigue-related changes in electrophysiological parameters was most pronounced for the rectus abdominis. Accordingly, it serves as a key indicator muscle for such loading conditions, with its fatigue level clearly correlating with reported levels of perceived exertion. Therefore, RPE ratings can effectively represent its fatigue state and are considered interchangeable in this context. This, however, does not apply to the fatigue levels of the examined oblique abdominal muscles.

Future investigations should explicitly (i) load the abdominals according to their main force direction and (ii) add pre- and post-exercise spinal stability tests. Measurements of intra-abdominal pressure would be very valuable for this purpose.

5. Conclusions

A 10 min static load of the abdominal muscles at 50% of the UBW evokes clear signs of muscular fatigue, both subjectively (rate of perceived exertion) and in the electrophysiological parameters rms, MF, FInsm2, and FInsm5 in all superficial abdominal muscles. However, the extent of fatigue correlates sufficiently well with RPE levels only for the rectus abdominis muscle. Both oblique abdominal muscles exhibited clear signs of fatigue but showed lower correlation levels and fatigued to a lesser extent. Further, they only sporadically revealed differences between low and high exertion groups. Thus, any perceived exertion during untwisted flexion tasks is mainly caused by fatigue occurring in the rectus abdominis muscle.

Regardless of the subjective perception of exertion, a smaller but similar physiological fatigue level in both oblique abdominal muscles can be assumed during untwisted submaximal endurance loading. Consequently, the extent of fatigue-related changes under load does not differ between individuals with low or high subjective fatigue in both oblique muscles. Based on these findings we conclude that untwisted fatiguing loads on the trunk muscles are limited by the rectus abdominis muscle endurance capacity, evoke muscular fatigue also in the oblique abdominal muscles, and are therefore accompanied by at least a temporary reduction in trunk stability. In short, during such endurance tasks the amount of fatigue in the oblique abdominal muscles does not correlate with the extent of perceived exertion. This perception gap bears the risk of underestimating the amount of fatigue in the oblique abdominal muscles. As adequate functioning of these particular muscles is important to sufficiently stabilize the spine, this temporal but relevant functional compromise should be kept in mind even if subjects do not experience high levels of perceived exertion. This is of practical relevance and should be explicitly taken into account by every professional trainer in order to avoid potentially dangerous exercises when the abdominal muscles have been fatigued beforehand.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A. (Christoph Anders); Methodology, C.A. (Christoph Anders); Software, C.A. (Christoph Anders); Validation, C.A. (Christoph Anders) and C.A. (Christin Alex); Formal analysis, C.A. (Christin Alex); Investigation, C.A. (Christin Alex); Resources, C.A. (Christoph Anders); Data curation, C.A. (Christoph Anders) and C.A. (Christin Alex); Writing—original draft, C.A. (Christoph Anders); Writing—review & editing, C.A. (Christoph Anders) and C.A. (Christin Alex); Visualization, C.A. (Christoph Anders); Supervision, C.A. (Christoph Anders); Project administration, C.A. (Christoph Anders); Funding acquisition, C.A. (Christoph Anders). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Berufsgenossenschaft Nahrungsmittel und Gastgewerbe (German Social Accident Insurance Institution for the foodstuffs and catering industry, Grant: 2.11.11.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Fridrich-Schiller-University Jena (2021-2373_1-BO, 7 December 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tesh, K.M.; Dunn, J.S.; Evans, J.H. The abdominal muscles and vertebral stability. Spine 1987, 12, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner-Morse, M.G.; Stokes, I.A. The effects of abdominal muscle coactivation on lumbar spine stability. Spine 1998, 23, 86–91; discussion 91–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerkefors, A.; Ekblom, M.M.; Josefsson, K.; Thorstensson, A. Deep and superficial abdominal muscle activation during trunk stabilization exercises with and without instruction to hollow. Man. Ther. 2010, 15, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.H.; Vera-Garcia, F.J.; McGill, S.M. Effects of abdominal muscle coactivation on the externally preloaded trunk: Variations in motor control and its effect on spine stability. Spine 2006, 31, E387–E393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caplan, N.; Gibbon, K.; Hibbs, A.; Evetts, S.; Debuse, D. Phasic-to-tonic shift in trunk muscle activity relative to walking during low-impact weight bearing exercise. Acta Astronaut. 2014, 104, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholewicki, J.; Juluru, K.; McGill, S.M. Intra-abdominal pressure mechanism for stabilizing the lumbar spine. J. Biomech. 1999, 32, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, I.A.F.; Gardner-Morse, M.G.; Henry, S.M. Intra-abdominal pressure and abdominal wall muscular function: Spinal unloading mechanism. Clin. Biomech. 2010, 25, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, G.T.; Morris, S.L.; Lay, B. Feedforward responses of transversus abdominis are directionally specific and act asymmetrically: Implications for core stability theories. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. 2008, 38, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebenbichler, G.R.; Oddsson, L.I.E.; Kollmitzer, J.; Erim, Z. Sensory-motor control of the lower back: Implications for rehabilitation. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 1889–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, P.; Cresswell, A.G.; Daggfeldt, K.; Thorstensson, A. In vivo measurement of the effect of intra-abdominal pressure on the human spine. J. Biomech. 2001, 34, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomonow, M. Time dependent spine stability: The wise old man and the six blind elephants. Clin. Biomech. 2011, 26, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, P.W.; Eriksson, A.E.; Shirley, D.; Gandevia, S.C. Intra-abdominal pressure increases stiffness of the lumbar spine. J. Biomech. 2005, 38, 1873–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtarzadeh, H.; Farahmand, F.; Shirazi-Adl, A.; Arjmand, N.; Malekipour, F.; Parnianpour, M. The Effects of Intra-Abdominal Pressure on the Stability and Unloading of the Spine. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2012, 12, 1250014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, C.M. Functional load abdominal training: Part 2. Phys. Ther. Sport 2001, 2, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puntumetakul, R.; Areeudomwong, P.; Emasithi, A.; Yamauchi, J. Effect of 10-week core stabilization exercise training and detraining on pain-related outcomes in patients with clinical lumbar instability. Patient Prefer. Adher. 2013, 7, 1189–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, M.L.; Aleksiev, A.; Wilder, D.G.; Pope, M.H.; Spratt, K.; Lee, S.H.; Goel, V.K.; Weinstein, J.N. European Spine Society--the AcroMed Prize for Spinal Research 1995. Unexpected load and asymmetric posture as etiologic factors in low back pain. Eur. Spine J. 1996, 5, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasseljen, O.; Unsgaard-Tondel, M.; Westad, C.; Mork, P.J. Effect of core stability exercises on feed-forward activation of deep abdominal muscles in chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Spine 2012, 37, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, P.; Twomey, L.; Allison, G.; Sinclair, J.; Miller, K. Altered patterns of abdominal muscle activation in patients with chronic low back pain. Aust. J. Physiother. 1997, 43, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebetrau, A.; Puta, C.; Anders, C.; de Lussanet, M.H.; Wagner, H. Influence of delayed muscle reflexes on spinal stability: Model-based predictions allow alternative interpretations of experimental data. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2013, 32, 954–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grondin, D.E.; Potvin, J.R. Effects of trunk muscle fatigue and load timing on spinal responses during sudden hand loading. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2009, 19, e237–e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, D.E.; Brown, S.H.; Callaghan, J.P. Trunk muscle responses to suddenly applied loads: Do individuals who develop discomfort during prolonged standing respond differently? J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2008, 18, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, K.; Fallentin, N.; Krogh-Lund, C.; Jensen, B. Electromyography and fatigue during prolonged, low-level static contractions. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1988, 57, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gandevia, S.C. Spinal and supraspinal factors in human muscle fatigue. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 1725–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dideriksen, J.L.; Farina, D.; Enoka, R.M. Influence of fatigue on the simulated relation between the amplitude of the surface electromyogram and muscle force. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2010, 368, 2765–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viitasalo, J.H.; Komi, P.V. Signal characteristics of EMG during fatigue. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1977, 37, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtman, C.J.; Stegeman, D.F.; Van Dijk, J.P.; Zwarts, M.J. Changes in muscle fiber conduction velocity indicate recruitment of distinct motor unit populations. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 95, 1045–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merletti, R.; Roy, S.H.; Kupa, E.; Roatta, S.; Granata, A. Modeling of surface myoelectric signals. II. Model-based signal interpretation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1999, 46, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttmann, A.; Jäger, M.; Sökeland, J.; Laurig, W. Electromyographical study on surgeons in urology. II Determination of muscular fatigue. Ergonomics 1996, 39, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodaglio, P. The use of subjective rating of exertion in Ergonomics. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2002, 24, 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Fontes, E.B.; Smirmaul, B.P.; Nakamura, F.Y.; Pereira, G.; Okano, A.H.; Altimari, L.R.; Dantas, J.L.; de Moraes, A.C. The relationship between rating of perceived exertion and muscle activity during exhaustive constant-load cycling. Int. J. Sports Med. 2010, 31, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, D.; Bilodeau, M. Rating of perceived exertion (RPE) in studies of fatigue-induced postural control alterations in healthy adults: Scoping review of quantitative evidence. Gait Posture 2021, 90, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, C.; Mader, L.S.; Herzberg, M.; Alex, C. Are Ratings of Perceived Exertion during Endurance Tasks of Predictive Value? Findings in Trunk Muscles Require Special Attention. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparto, P.J.; Parnianpour, M. Estimation of trunc muscle Forces and Spinal Loads During Fatiguing Repetetive Trunk Exertions. Spine 1998, 23, 2563–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, K.; Nicolaisen, T. Two methods for determining trunk extensor endurance. A comparative study. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1986, 55, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, B.; Stevens, V.; Van Tiggelen, D.; Perneel, C.; Crombez, G.; Danneels, L. Performance based on sEMG activity is related to psychosocial components: Differences between back and abdominal endurance tests. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2014, 24, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, P.W. Core stability exercise in chronic low back pain. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 2003, 34, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNair, P.J.; Depledge, J.; Brettkelly, M.; Stanley, S.N. Verbal encouragement: Effects on maximum effort voluntary muscle action. Br. J. Sports Med. 1996, 30, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anders, C.; Schönau, T. Ten Minutes Extension Endurance Test in Healthy Inactive vs. Active Male People. J. Orthop. Sports Med. 2022, 4, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, G. Perceived exertion as an indicator of somatic stress. J. Rehabil. Med. 1970, 2, 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, J.K.; Kippers, V.; Richardson, C.A. Muscle fibre orientation of abdominal muscles and suggested surface EMG electrode positions. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1998, 38, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mörl, F.; Anders, C.; Grassme, R. An easy and robust method for ECG artifact elimination of SEMG signals. In Proceedings of the XVII Congress of the International Society of Electrophysiology and Kinesiology Aalborg, Aalborg, Denmark, 22–25 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov, G.V.; Arabadzhiev, T.I.; Mileva, K.N.; Bowtell, J.L.; Crichton, N.; Dimitrova, N.A. Muscle fatigue during dynamic contractions assessed by new spectral indices. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006, 38, 1971–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puce, L.; Pallecchi, I.; Marinelli, L.; Mori, L.; Bove, M.; Diotti, D.; Ruggeri, P.; Faelli, E.; Cotellessa, F.; Trompetto, C. Surface Electromyography Spectral Parameters for the Study of Muscle Fatigue in Swimming. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 644765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.K.; Pah, N.D.; Bradley, A. Wavelet analysis of surface electromyography to determine muscle fatigue. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2003, 11, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Tscharner, V. Intensity analysis in time-frequency space of surface myoelectric signals by wavelets of specified resolution. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2000, 10, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand. J. Stat. 1979, 6, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power for the Behavioural Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Montecinos, C.; Bustamante, A.; Candia-Gonzalez, M.; Gonzalez-Bravo, C.; Gallardo-Molina, P.; Andersen, L.L.; Calatayud, J. Perceived physical exertion is a good indicator of neuromuscular fatigue for the core muscles. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2019, 49, 102360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannion, A.F. Fibre type characteristics and function of the human paraspinal muscles: Normal values and changes in association with low back pain. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 1999, 9, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannion, A.F.; Dumas, G.A.; Cooper, R.G.; Espinosa, F.J.; Faris, M.W.; Stevenson, J.M. Muscle fiber size and type distribution in thoracic and lumbar regions of erector spinae in healthy subjects without low back pain: Normal values and sex differences. J. Anat. 1997, 190, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggmark, T.; Thorstensson, A. Fibre types in human abdominal muscles. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1979, 107, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomonow, M.; Baratta, R.; Shoji, H.; D’Ambrosia, R. The EMG-force relationships of skeletal muscle; dependence on contraction rate, and motor units control strategy. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1990, 30, 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Clancy, E.A.; Hogan, N. Probability density of the surface electromyogram and its relation to amplitude detectors. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1999, 46, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrova, N.A.; Dimitrov, G.V. Interpretation of EMG changes with fatigue: Facts, pitfalls, and fallacies. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2003, 13, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabadzhiev, T.I.; Dimitrov, V.G.; Dimitrova, N.A.; Dimitrov, G.V. Interpretation of EMG integral or RMS and estimates of “neuromuscular efficiency” can be misleading in fatiguing contraction. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2010, 20, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, C.; Steiniger, B. Main force directions of trunk muscles: A pilot study in healthy male subjects. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2018, 60, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, F.; Orizio, C.; Veicsteinas, A. Electromyogram and mechanomyogram changes in fresh and fatigued muscle during sustained contraction in men. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998, 78, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder, D.G.; Aleksiev, A.R.; Magnusson, M.L.; Pope, M.H.; Spratt, K.F.; Goel, V.K. Muscular response to sudden load. A tool to evaluate fatigue and rehabilitation. Spine 1996, 21, 2628–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, A.G.; Oddsson, L.; Thorstensson, A. The influence of sudden perturbations on trunk muscle activity and intra-abdominal pressure while standing. Exp. Brain Res. 1994, 98, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, P.; Cresswell, A.G.; Thorstensson, A. Perturbed upper limb movements cause short-latency postural responses in trunk muscles. Exp. Brain Res. 2001, 138, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, P.; Richardson, C.A. Neuromotor dysfunction of the trunk musculature in low back pain patients. In Proceedings of the 12th International Congress of the World Confederation of Physical Therapists, Washington, DC, USA, 25–30 June 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schönau, T.; Anders, C. Force capacity of trunk muscle extension and flexion in healthy inactive, endurance and strength-trained subjects—A pilot study. Ger. J. Exerc. Sport Res. 2024, 54, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, E.; Anders, C.; Walther, M.; Schenk, P.; Scholle, H.C. Force Capacity of Back Extensor Muscles in Healthy Males-Effects of Age and Recovery Time. J. Appl. Biomech. 2014, 30, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anders, C.; Ludwig, F.; Sänger, F.; Marks, M. Eight Weeks Sit-Up versus Isometric Abdominal Training: Effects on Abdominal Muscles Strength Capacity. Arch. Sports Med. 2020, 4, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, C.; Schönau, T. Spatiotemporal characteristics of lower back muscle fatigue during a ten minutes endurance test at 50% upper body weight in healthy inactive, endurance, and strength trained subjects. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).