Abstract

Deformation bands provide a microscale record of strain localisation within sandstones and offer key insights into deformation mechanisms and conditions. This study integrates detailed field observations with optical microscopy and three-dimensional X-ray microtomography (µCT) to characterise deformation bands in thick-bedded sandstones of the Krosno Formation (Silesian Nappe, Outer Carpathians). Two sections within a regional first-order fold were examined: an upper, mudstone-rich and mechanically weak unit, and an underlying sandstone-dominated competent unit. The contrasting kinematics of the deformation bands reflect layer-parallel strain partitioning during the onset of folding. Normal-shear bands developed in the weaker upper unit, whereas compaction bands formed pervasively in the competent unit. Microstructurally, shear bands are sharply bounded, organised in arrays, and dominated by grain rearrangement with local cataclasis, while compaction bands exhibit diffuse margins, tight grain packing, and disaggregation through progressive cataclasis. These features indicate that the bands formed under shallow-burial (<500 m) conditions. µCT imaging reveals the bands as darker, low-attenuation zones relative to the host rock, reflecting post-deformational cementation and the absence of cement within the bands. This diagenetic contrast enhanced mechanical heterogeneity and promoted later reactivation and fracture development. The study provides a three-dimensional microstructural assessment of early strain localisation in mechanically layered rocks in the buckle fold limb.

1. Introduction

Folding in layered sedimentary rocks produces a spectrum of deformation structures that accommodate strain at different scales, e.g., [1,2,3]. Among these, deformation bands have gained increasing attention for their systematic occurrence and distinctive microstructural and kinematic features, e.g., [4,5,6]. Deformation bands are millimetre- to centimetre-wide, tabular strain localisation structures that form within porous granular rocks [7]. They are regarded as geological discontinuities alongside fractures [8]. Unlike fractures, however, deformation bands preserve the continuity of the host rock, remaining cohesive while exhibiting distinct physical properties that reflect the microstructures generated during their formation and subsequent evolution. Because individual bands can accommodate only limited displacement, they commonly occur in clusters forming dense networks, e.g., [9].

The microstructural classification of deformation bands proposed by Fossen et al. [10] distinguishes several types that reflect different deformation mechanisms. Disaggregation bands form by granular flow involving frictional sliding and grain rotation, whereas phyllosilicate bands result from the smearing of clay minerals. Cataclastic bands develop through grain crushing, while pressure-solution and cementation bands form by dissolution and reprecipitation of mineral phases. Among the microstructural types, disaggregation and cataclastic deformation bands are the most common and have been the focus of most recent studies, e.g., [11,12]. The mechanism responsible for the formation of deformation bands depends largely on burial depth (confining pressure) and the induration of the host strata, e.g., [10,13,14]. Disaggregation bands are typically expected to form under shallow burial conditions within poorly lithified sediments, whereas increasing burial depth and host rock induration promote the development of cataclastic bands [11,13].

The kinematics of deformation bands are governed by both the orientation and magnitude of the principal stress axes cf. [15]. They are therefore classified into three main kinematic types: dilation, shear, and compaction, e.g., [10,11]. Hybrid bands are also found, showing transitional behaviour between these end-member types, such as shear-enhanced dilation or shear-enhanced compaction. Deformation band orientation is systematically related to the principal stress field: dilation bands form parallel to the maximum principal stress (σ1) and perpendicular to the minimum (σ3), compaction bands develop perpendicular to σ1, and shear bands typically occur at an angle of about 30° to σ1. The orientation of hybrid bands varies progressively according to the relative contribution of shearing versus compaction or dilation [8].

Deformation bands form across the entire range of tectonic regimes, from extensional to contractional, and are associated with both thrusting and strike-slip faulting [11]. They have been documented in fold-and-thrust systems such as the Outer Carpathians [4,16], the Pyrenees [17], and the Qaidam Basin [18], as well as accretionary prisms such as the Nankai [19,20]. Results of these studies show that the distribution and types of deformation bands can be controlled by large-scale tectonic structures. Although deformation bands have been widely investigated, their localisation within folds, particularly during the earliest stages of deformation, remains incompletely understood. Much of the existing research focuses on deformation bands in hinge zones, where strain is most strongly expressed, e.g., [18,21,22], or track their progressive evolution along fold limbs, e.g., [6,23], while early localisation within limbs is captured only rarely, e.g., [24]. The Outer Carpathians provide an appropriate setting for this study, as deformation bands are common within folded sandstone–mudstone successions [4,16,25,26]. The mechanical contrast between these lithologies introduces an additional control on band development. These conditions allow a direct assessment of how structural position and mechanical layering influence the character of deformation bands. Accordingly, deformation bands formed in mechanically competent and incompetent units are expected to display measurably diverse strain localisation modes and microstructural features.

To advance this understanding, the present study employs a multi-scale, high-precision approach that integrates field studies, optical microscopy with three-dimensional X-ray microtomography to characterise deformation bands in sandstones of the Krosno Formation in the back limb of the first-order fold within the Silesian Nappe, Outer Carpathians. The aims of the study are to (1) document the architecture and microstructural types of deformation bands formed in sandstone beds within competent and incompetent lithostratigraphic units of a fold limb, (2) characterise their internal fabric using high-resolution X-ray microtomography, and (3) decipher how variations in mechanical competence controlled strain localisation and deformation conditions during the early stages of folding. The results provide new insights into the microstructural record of deformation bands in sandstones and illustrate how integrating three-dimensional imaging with conventional petrography can reveal the style and distribution of strain partitioning within mechanically layered folds. This study provides the first three-dimensional, high-resolution microscale characterisation of deformation bands in the Outer Carpathians.

2. Geological Background

The Outer Carpathians are characterised by a complex lithology dominated by deep-marine turbiditic successions consisting mainly of alternating sandstone, mudstone, and conglomerate layers deposited from the Early Cretaceous to the Miocene, e.g., [27]. The belt developed through progressive shortening associated with subduction of the European Platform beneath the ALCAPA and Tisza–Dacia microplates, followed by their subsequent collision [28,29,30,31]. The Outer Carpathians represent the frontal accretionary wedge of this orogenic system and display the characteristic architecture of a fold-and-thrust belt [32,33,34]. In Poland, the belt comprises a series of outward-verging nappes, arranged from internal to external as follows: Magura, Dukla, Silesian, Subsilesian, Skole, and Borislav–Pokuttia [35,36] (Figure 1a).

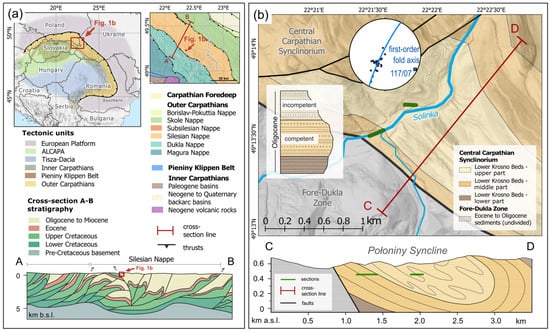

Figure 1.

Location and geological framework of the study area: (a) Regional tectonic context within the Outer Carpathians, simplified after [31,37,38]; (b) geological setting of studied sections modified after [39,40].

The study is located in the Silesian Nappe within the Central Carpathian Synclinorium. The Central Carpathian Synclinorium is composed of kilometre-scale, NW–SE-trending folds that are cut by several longitudinal faults. The age of the strata in this part of the Silesian Nappe ranges from the Late Cretaceous to the Early Miocene. At the surface, however, nearly the entire section is composed of deposits traditionally referred to as the Lower Krosno Beds [41], of Oligocene to Early Miocene age [42]. The Lower Krosno Beds represent synorogenic deposits comprising three lithologically distinct parts that differ in the proportion of sandstone to mudstone intercalations [39,43]. The upper and lower parts are dominated by mudstones with thin sandstone interbeds, whereas the middle part consists mainly of thick-bedded sandstones, one to several metres thick, locally forming complexes up to 200 m thick [41,44,45,46]. Mechanically, the middle sandstone-dominated part represents a competent lithostratigraphic unit, whereas the upper mudstone-rich part is incompetent. In the formal lithostratigraphic scheme, the Lower Krosno Beds are a part of the Krosno Formation.

The study focuses on the Połoniny Syncline. This structure represents the southernmost and structurally innermost fold of the Central Carpathian Synclinorium. It is an overturned buckle fold, with the back limb and the forelimb dipping moderately to the northeast. The fold axis plunges gently (7°) towards 117°. The middle part of the Lower Krosno Beds reaches a stratigraphic thickness up to ~500 m, whereas the upper part in the synclinal core is affected by second-order folding and has an estimated stratigraphic thickness of at least ~200 m. The studied sites are located in the southwestern limb (Figure 1b).

3. Materials and Methods

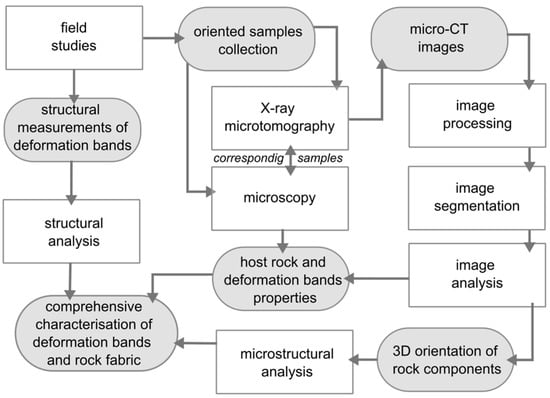

This study employed a multi-scale workflow integrating field observations, optical microscopy and 3D µCT analysis. All hand specimens were collected with precise structural orientation and cut perpendicular to the deformation bands to ensure a consistent geometric reference across methods. This design enabled direct comparison between field-scale structures, thin-section microstructures and three-dimensional fabric metrics derived from the same samples. The detailed procedures are provided below, and the overall workflow is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The workflow.

3.1. Field Observations and Structural Analysis

The study is based on field observations of deformation bands exposed in thick-bedded sandstones at two natural outcrops, representing distinct structural and lithostratigraphic positions. Field measurements included the orientation (strike and dip) of bedding planes and deformation bands. Orientation measurements were obtained from two approaches. In the field, only deformation bands with exposed surfaces were measured. In addition, oriented samples were collected and cut perpendicular to the bands. Based on deformation band traces on different faces of the samples, deformation bands were measured. This dual approach ensured cross-validation between field and laboratory orientations. The procedure ensured a rigorous and precise reconstruction of the true band orientation in three dimensions. Structural data were analysed using WinTensor software version 5.9.2 [47]. The orientations of the principal stress axes were determined using the right dihedron [48] or PBT [49] inversion method, which identifies the best-fitting stress tensor for a given set of structures. Because the deformation bands lack measurable slip lineations, the resulting stress tensors should be regarded as first-order estimates based on plane orientations and apparent offsets, particularly for shear bands. The combined dataset of 44 measurements was grouped by outcrop and by deformation band type. Conjugate sets were treated as joint subset for inversion. Data selection and solution quality assessment followed the standard WinTensor separation procedure based on angular misfit calculation cf. [47]. The stress-inversion solution was accepted when the angular deviation for the given dataset remained below the threshold defined as the mean deviation plus two standard deviations. Data exceeding this threshold were treated as outliers and excluded from the solution. Based on the described criteria, two solutions were prepared using 13 and 21 data points, respectively. A back-tilt test was performed to determine whether the structures are of pre-tilt, syn-tilt, or post-tilt origin. All stereographic projections were presented on equal-area, lower-hemisphere Schmidt nets. The stereographic projections included uncertainty estimates shown as confidence arcs and mean cone angles (standard deviation), together with misfit values of the best-fitting tensors and their corresponding histograms.

3.2. Microscopic Analysis

Thin sections were prepared at the Cutting and Polishing Laboratory, AGH University of Krakow. Microscopic observations and photomicrographs were obtained using a Nikon Eclipse polarising microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Tokyo, Japan) under both transmitted and cross-polarised light. These analyses provided a petrographic characterisation of the host sandstones and the deformation bands. Grain-size measurements were carried out following the method of Folk and Ward [50].

3.3. X-Ray Computed Microtomography (µCT)

X-ray computed microtomography (µCT) is a non-destructive imaging technique that enables high-resolution, three-dimensional visualisation of the internal rock structure, including pore distribution, fractures, and grain fabric, e.g., [51]. Two oriented sandstone samples containing deformation bands were analysed. Each sample measured approximately 2 cm in width, 3 cm in height, and 1 cm in depth. Scanning was conducted at the Laboratory of Micro- and Nano-Tomography, AGH University of Krakow, using a Nanotom S system (GE Sensing & Inspection Technologies GmbH, Wunstorf, Germany) equipped with a nanofocus X-ray tube.

Each sample was rotated through 360° in 1800 steps, using a source voltage of 100 kV and a tube current of 400 µA, producing 2000 image slices at a voxel resolution of 7.5 µm. Image reconstruction was performed using the Feldkamp cone-beam algorithm [52] implemented in GE’s datosX software (v. 2.1.0). The resulting 3D images represent X-ray attenuation, where darker pixels correspond to lower attenuation (e.g., pores) and brighter pixels indicate higher attenuation, e.g., dense mineral phases such as calcite; cf. [53].

The image processing and analysis were performed using the Fiji software version 1.52p [54]. Firstly, the raw image was converted into an 8-bit format. Subsequently, image enhancement was applied by adjusting brightness and contrast. Correction of X-ray attenuation was performed using BaSiC [55] to remove cupping artefacts. Beam-hardening artefacts were not present in the samples, as the rocks lack components with sufficiently contrasting X-ray absorption. The granular components of the rock, i.e., pores and calcite, calibrated with supplementary microscopic analysis, were extracted and binarized using this global thresholding approach. The resulting 3D masks for calcite and pore space represent the only unambiguously distinguishable granular components that could be reliably extracted, as all remaining mineral constituents form a compositionally uniform matrix with insufficient grayscale contrast for phase separation. The binarized image was filtered using a 3D median filter (size 2 × 2 × 2 voxels), and objects at the image edges were removed Finally, a size filter removing objects smaller than 100 voxels was applied to eliminate artefacts and the imprint of the smallest but most abundant features near the resolution limit. The resultant image was then segmented to assign each object a unique label. The prepared image was subjected to measurements: an ellipsoid was fitted to each grain, and the orientations of the ellipsoid axes were determined. Digital measurements were then calibrated by applying rotations that restored the original field orientation of the samples, allowing the µCT-derived fabrics to be directly compared with field-scale structural measurements.

4. Results

4.1. Structural Analysis

Deformation bands were identified in two sections within thick-bedded sandstones of the Lower Krosno Beds—one located in the upper and the other in the middle part of the unit. Both exposures occur on the southern limb of the Połoniny Syncline. The upper part represents a less competent, mudstone-dominated succession, whereas the middle part consists of thick-bedded sandstones forming a mechanically competent unit (Figure 1b).

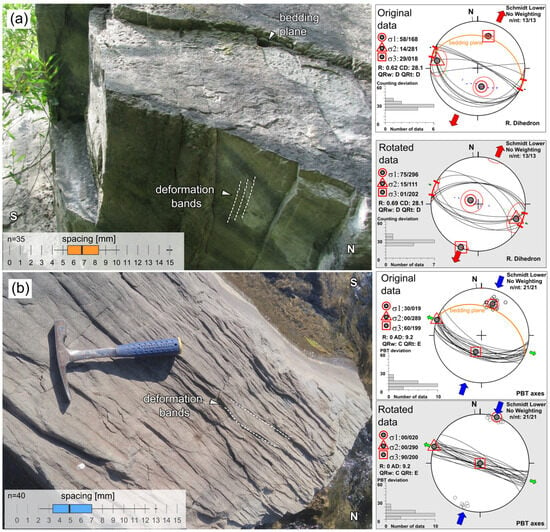

In the upper part of the Lower Krosno Beds, deformation bands occur within 1–2 m thick sandstone interbedded by mudstone layers, which are typically ~1 m thick but locally reach several metres. The strata dip approximately 25° towards the NE and are overturned, forming second-order folds that exceed the scale of the outcrop. Within these beds, deformation bands are unevenly distributed and tend to form clusters. They occur as conjugate sets intersecting at angles of about 60°, with an average strike of ca. 120°. One set dips gently (25–35°) towards the SW, whereas the other is subvertical to vertical. When restored to the original horizontal bedding orientation, the deformation bands dip at about 60° to bedding, showing normal-shear kinematics, indicating extension in the 22° direction. Quantitatively, normal-shear bands show spacings between 4 and 15 mm (mean 7.2 mm), corresponding to estimated densities of 65–140 bands/m (using average and maximum spacing), and they are spatially restricted to a zone of roughly 10 m along the exposure. (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Field view of the studied outcrops showing thick-bedded sandstones of the Lower Krosno Beds with deformation bands. Lower-hemisphere equal-area stereographic projections show the orientation of bedding and deformation bands at the present position and after backtilting to the original horizontal bedding (grey background): (a) Normal-shear deformation bands; (b) Compaction deformation bands.

In the middle part of the Lower Krosno Beds, deformation bands are developed pervasively within thick-bedded sandstones, 1–4 m thick, intercalated with thin mudstone layers. They form a regular, closely spaced network of tabular structures striking approximately 120°, oriented perpendicular or nearly perpendicular to bedding. Their consistent orientation, planar geometry, and lack of measurable shear offset indicate compaction kinematics, recording contraction in the 20° direction. Compaction bands are more densely developed than the normal-shear bands, with spacings ranging from 2 to 13 mm (mean 5.4 mm), corresponding to estimated densities of 75–185 bands/m. Unlike the normal-shear bands, compaction bands occur continuously across several outcrops over a distance of roughly 100 m (Figure 3b).

The contrasting orientation and kinematics of deformation bands reflect strain partitioning across mechanically heterogeneous strata, with layer-parallel extension recorded in the upper part and layer-parallel contraction in the middle part of the Lower Krosno Beds. These field observations provide the structural framework for subsequent microstructural analyses.

4.2. Microscopic Analysis

The sandstones hosting deformation bands are composed predominantly of quartz and lithic fragments (58–70%), with minor feldspars (2–6%), micas (4–20%), and calcite (9–20%) occurring as both grains and cement. The matrix content varies from 1 to 6% in sandstones from the competent middle part to 15–25% in those from the less competent upper part. Grains are angular, poorly sorted, and show low sphericity. Intergranular porosity is generally below 1%. Primary sedimentary stratification (S0) is evident in several samples as a bedding-parallel grain alignment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Petrographic characteristics of the host rocks and deformation bands (values in mm).

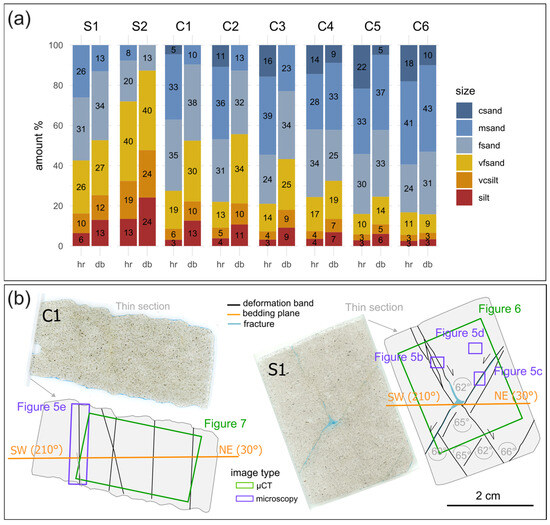

Deformation bands are consistently finer-grained than their host rocks, with average grain diameters reduced by a factor of 1.1–1.9 (0.06–0.24 mm). Their width ranges from 0.2 to 1.6 mm and broadly increases with host grain size (Table 1, Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

(a) Grain-size distribution of the granular framework in the host rocks (hr) and deformation bands (db). Abbreviations: csand—coarse sand (0.5–1.0 mm), msand—medium sand (0.25–0.50 mm), fsand—fine sand (0.125–0.250 mm), vfsand—very fine sand (0.063–0.125 mm), vcsilt—very coarse silt (0.040–0.063 mm), silt (<0.04 mm). Bars show the proportion (%) of each grain-size fraction; sample identification numbers are indicated above the bars; (b) Thin section scans documenting the photomicrographs presented in this study.

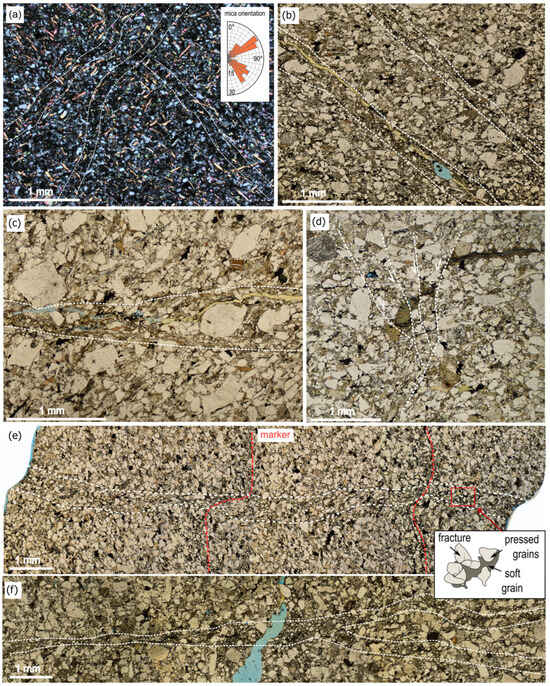

Normal-shear bands are densely developed within very fine-grained sandstone rich in micas. They form networks of closely spaced arrays, composed of multiple narrow, parallel bands (Figure 5a). Microscopically, they appear as slightly darker bands with a higher clay content than the host rock. Cross-cutting relationships between individual bands are indistinct. Shear offsets reach up to 1 mm, and although grains within the bands are smaller than those in the host rock, intragranular fracturing is absent (Figure 5b). The microstructure indicates grain rearrangement by disaggregation and granular flow as the dominant deformation mechanism. A pervasive reorientation of mica flakes forming an x-shaped pattern mirrors the geometry of the conjugate sets. Microscale measurements show that the acute angles between the two conjugate sets range from 60° to 66°, matching the geometry inferred at outcrop scale (Figure 4b). In coarser-grained sandstones, the bands typically occur as subparallel strands, each comprising several closely spaced bands, with at least one sharp boundary with the host rock (Figure 5b). The thickest bands, which exhibit the largest shear offsets (up to 2 mm), display intense cataclasis, manifested by grain-size reduction and rounding caused by grain rolling (Figure 5c). Due to the scarcity of clear correlatable markers, systematic measurements of displacements were not possible. The cataclastic bands are characterised by a brown-coloured matrix, and in several cases, fractures are developed along their traces. Additionally, structureless slip surfaces, a few to several grains long, are pervasively developed within the host sandstone. These simple slip planes locally form complex intersecting networks and probably represent the earliest stage of deformation band development (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Microphotographs of deformation bands: (a) Shear deformation bands in very fine-grained sandstone showing pronounced reorientation of mica flakes; cross-polarised light; (b) Deformation bands in fine-grained sandstone with closely spaced, subparallel strands; the lower band displays more intense cataclasis and fracturing; (c) Deformation band with pronounced cataclasis and rounded grains within the band core; (d) Discrete slip-surfaces of limited extent; (e) Disaggregation–compaction bands in sandstone with well-developed sedimentary foliation, showing microfolding; (f) Cataclastic deformation band with narrow crushing zones and branching geometry. White dashed lines indicate the extent of the deformation bands.

In compaction bands, the most distinctive feature is the reorientation of grains (Figure 5e). Disaggregation causes the grains to align parallel to the long axis of the bands, producing a subtle preferred orientation. In addition to disaggregation, microcracking, pore collapse, and local grain crushing are also observed in some bands (Figure 5f). In cataclastic bands, grain size typically decreases towards the band core. Grain fracturing is more frequent and intense in compaction bands with uniform grain size, whereas in the host rock it remains minor and confined to individual clasts. Locally, stiffer grains are indented into adjacent plastic ones within the deformation bands. The boundaries of the bands show a gradual transition, with deformation intensity decreasing toward the core. Compaction bands are most distinct in sandstones with well-marked sedimentary stratification (S0); in more weakly stratified sandstones, they display irregular widths and may be reduced to a narrow core zone. Shear offset within compaction bands is rare, typically not exceeding 0.8 mm. Microfolding is particularly prominent in samples with strong sedimentary layering (Figure 5e).

In summary, normal-shear bands are characterised by grain-size reduction, sharp boundaries, regular geometry, and grain rearrangement through disaggregation, whereas compaction bands display diffuse margins, irregular geometry, and progressive cataclasis associated with tight grain packing as well as grain-size reduction.

4.3. X-Ray Microtomography Assessment

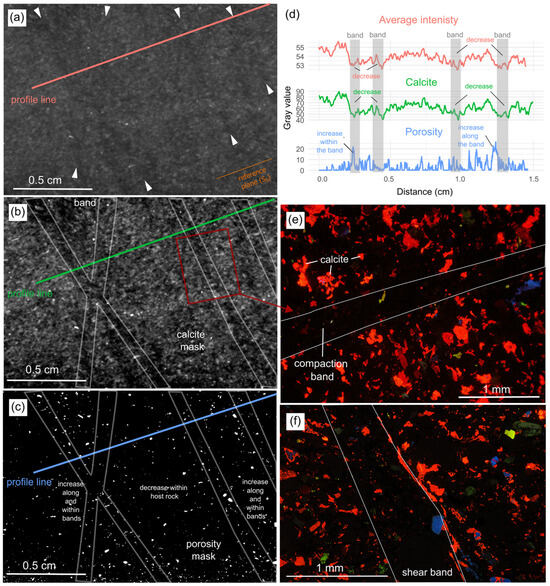

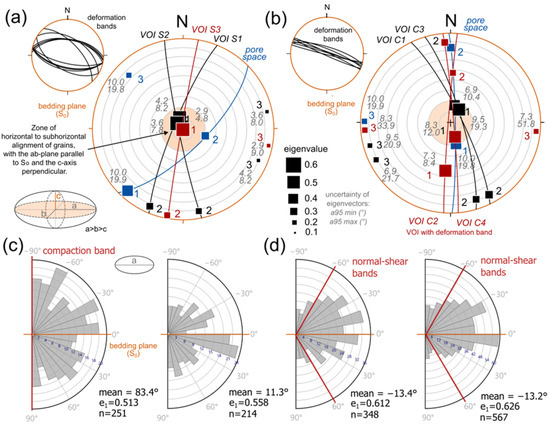

Two samples with deformation bands were subjected to X-ray microtomography analysis (Figure 3b): the sample with the normal shear bands (S1) and compaction bands (C1).

The µCT volume of the host sandstone (S1) displays variable voxel intensities corresponding to differences in X-ray absorption. The host rock shows moderate intensity (purple tones in Figure 6a), whereas deformation bands appear as narrow, darker zones with lower absorption. Although the overall contrast between the bands and the matrix is subtle, their visibility improves when visualised relative to high-absorption components (pink/orange tones), which are largely absent within the bands (Figure 6b). Porosity within the scanned volume occurs in two forms: (1) granular pores, rounded and evenly distributed, and (2) fracture-related pores, developed locally along the shear bands (Figure 6c). Some deformation bands remain unfractured. Fracture surfaces exhibit a wavy morphology with linear features marking intersections between conjugate sets of bands (Figure 6d). Orientation analysis of granular components reveals two main trends (Figure 6e). Granular pores are preferentially aligned parallel to the shear-band planes, while the long axes of grains (ab planes) are oriented parallel to the primary sedimentary fabric (S0), expressed by near-vertical c-axes. Locally, grains are slightly tilted toward N–S (VOI-volume of interest S2) or SW–NE (VOI S1 and VOI S3) directions, consistent with the inferred shear kinematics in the microscopic studies.

Figure 6.

µCT images of the sample illustrating normal shear deformation bands. (a) General view of the scanned specimen, with deformation bands indicated by white lines. (b) The same volume rendered at 70% transparency, emphasising components exhibiting higher X-ray absorption than quartz. (c) Distribution of pore space within the scanned volume. (d) Fracture surface morphology showing gently undulating lineations resulting from interactions between conjugate bands (arrowed). (e) Lower-hemisphere stereographic projections of deformation bands, pore space, and grain orientations plotted as c-axes of fitted ellipsoids (poles to ab planes). VOI—volume of interest. The scanned volumes are oriented relative to the deformation bands in the back-tilted position.

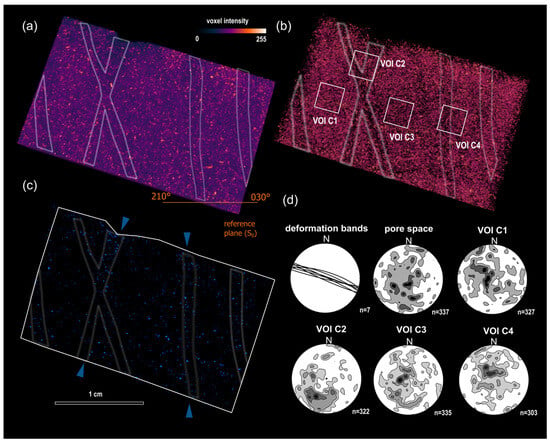

The µCT images of the compaction bands show broadly similar patterns. The bands appear darker than the host rock, reflecting lower X-ray absorption and a reduced content of high-attenuation components (Figure 7a,b). Porosity occurs in granular form and is distributed across the rock, though a slightly higher concentration of pores is observed along the compaction bands (Figure 7d). The orientation of both pores and grains indicates a general alignment parallel to the bedding; however, the pattern is weaker and more irregular than that observed in the normal-shear band sample. In the VOI C2, located near a compaction band affected by microfolding and shearing, the tilting of grains is clearly visible. Overall, the fabric defines weak but consistent alignment trends emphasising the trace of the bands and the layer-parallel shortening direction (~NE-SW).

Figure 7.

µCT images of the sample showing compaction bands. (a) General view of the scanned specimen, with deformation bands indicated by white lines. (b) The same volume rendered at 70% transparency, highlighting components with higher X-ray absorption than quartz. (c) Pore space distribution within the scanned volume. (d) Lower-hemisphere stereographic projections of deformation bands, pore space, and grain orientations plotted as c-axes of fitted ellipsoids (poles to ab planes) with a contouring interval of 1% per 1% area. VOI—volume of interest. The scanned volumes are oriented relative to the deformation bands in the back-tilted position.

Overall, the µCT observations reveal that normal-shear bands are more sharply defined and structurally coherent, whereas compaction bands display a more diffuse internal fabric and irregular porosity patterns.

5. Discussion

5.1. Strain Partitioning

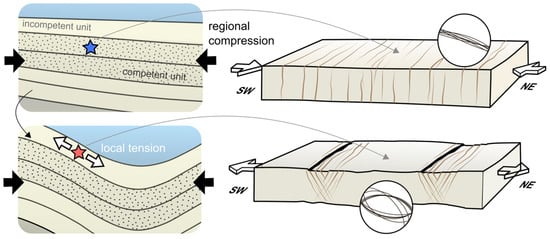

The deformation bands formed under contrasting strain regimes. The normal-shear bands record layer-parallel extension, whereas the compaction bands developed under layer-parallel shortening. Their differing kinematics reflect variations in mechanical stratigraphy and associated modes of strain accommodation. The compaction bands occur within the mechanically competent strata of the middle part of the Lower Krosno Beds, which exerted primary control on the regional folding style [56,57]. In contrast, the normal shear bands formed within the less competent, mudstone-dominated upper part of the same unit. Both types of deformation bands record extension (~022°) and contraction directions (~020°) consistent with the regional shortening direction of the first-order fold (~027°; Figure 1b). The trigger for their origin is the onset of the shortening and folding in the studied section. The compaction bands reflect layer-parallel shortening, a process characteristic of buckle folding that operates from its very onset, even before any tilting of the strata occurs [1,58,59]. As buckling and fold growth progress, the overlying strata experience outer-arc extension that may promote the formation of normal-shear bands. These microstructural strain patterns indicate incipient tangential longitudinal strain partitioning during early buckle folding. The alternation of thick-bedded sandstones and several metres thick mudstone interbeds likely enhanced this mechanical decoupling, facilitating layer parallel extension within sandstone layers as well as second-order folding, e.g., [60]. Although the upper part of the Lower Krosno Beds underwent substantial bedding rotation—about 150° around a horizontal axis, the formation of deformation bands was already possible during the incipient stage of folding, at low tilting angles. However, given the structural complexity, marked by the presence of second-order folds and the local character of the structures, the formation of the normal-shear bands during the later stages of first-order fold growth cannot be entirely ruled out. Second-order folding within less competent, mudstone-rich intervals of the upper Lower Krosno Beds is common in the region [40,56]. Consequently, while the compaction bands reflect regionally developed layer-parallel shortening within the competent unit, the normal-shear bands record more localised strain adjustments in the less competent strata. These structures capture the earliest stages of deformation associated with the folding in the Silesian Nappe (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Schematic model illustrating the development of compaction and shear deformation bands during early folding.

5.2. Microstructure and Deformation Conditions

The microstructural characteristics of deformation bands are governed not only by their kinematic type but also by the lithological properties of the host rock, e.g., [11]. This lithological control is particularly evident in the case of normal-shear bands. In very fine-grained sandstones rich in micas, deformation bands are pervasively developed and dominated by granular flow and grain rearrangement leading to the formation of disaggregation bands. In contrast, in coarser-grained sandstones, the deformation is more localised, forming clustered cataclastic bands. These cataclastic bands exhibit mutual crosscutting relationships, as revealed by µCT imaging, suggesting multiple slip events consistent with the geometrical model of Nicol et al. [61]. The predominance of disaggregation and weak cataclasis indicates shallow burial and limited induration of the host strata, e.g., [10,13]. The microstructures of compaction bands are consistent with deformation dominated by compaction and are characterised by grain disaggregation, microfolding, cataclasis, and pore collapse. Experimental studies show that compaction bands typically form as narrow zones of strain localisation, only a few grain diameters wide, particularly in homogeneous granular rocks [62,63]. In less homogeneous aggregates, however, deformation may propagate diffusely by cataclastic flow [64]. This explains the observed variability in microstructures, including microfolding within bands developed in stratified sandstones and cataclasis dominating in structureless sandstones. Minor shear offsets observed along some compaction bands may reflect progressive deformation during bedding rotation and folding. They may also result from slight deviations from perpendicularity to the shortening direction, which introduce a small shear component superimposed on dominant compaction. The shearing accommodated within these bands is negligible and occurs rarely. It reflects either the compactional process itself, cf. [5], or local strain partitioning within a mechanically heterogeneous material, as expected in poorly sorted, immature sandstones. The branching and anastomosing geometries observed in some compaction bands can similarly be attributed to local lithological heterogeneities, consistent with the ‘wiggly’ geometries described by [65,66]. Considering the pre-tilt stratigraphic thickness of the Oligocene–Miocene succession, the structural position of the studied sections (with an overburden of approximately 200–500 m), and the microstructural indicators of shallow burial and poor induration, the observations support an early origin of the deformation bands. This interpretation is consistent with field evidence reported from comparable settings and observations, e.g., [13,67,68]. For instance, observations from the Pannonian Basin indicate that disaggregation bands typically form at ~0–300 m depth, weakly cataclastic bands at ~50–425 m, and moderately cataclastic bands at ~250–620 m [13].

5.3. µCT Record and Implications

The µCT images of deformation bands, irrespective of their type, display a generally lower voxel intensity compared to the surrounding host rock. The lower intensities, expressed as darker tones in the images, reflect reduced X-ray absorption within the deformation bands (Figure 9a,b). This contrast results primarily from calcite cementation, cf. [69]. Calcite is abundant in the parts of the host rock that lack deformation bands. The contrast is further enhanced by the elevated porosity within and along the deformation bands. (Figure 9b,c). Consequently, the cemented host rock shows higher voxel intensities and appear brighter in the µCT images, while the deformation bands occur as narrow, dark streaks. Calcite exhibits a higher X-ray absorption coefficient than other rock-forming components such as quartz and clays in the analysed samples [70] (Figure 9d). The lack of calcite cement within deformation bands is supported by cathodoluminescence imaging, which reveals near complete absence of calcite inside the bands and implies that cementation postdates deformation (Figure 9e,f). This stems from the fact that early calcite precipitation would have lithified the sandstone, inhibited granular flow, and prevented the formation of disaggregation bands. Only minor calcite cement entered the bands later because they were already tightly packed. As a result, later cementation was limited to small secondary pores formed by the dissolution or replacement of less stable grains (Figure 9e,f).

Figure 9.

µCT–based visualisation and complementary cathodoluminescence imaging. (a) Averaged grayscale density map of sample S1, where deformation bands appear as relatively dark, low-attenuation streaks (arrowed). (b) Calcite-segmentation mask overlain on band boundaries, illustrating the markedly lower calcite content within deformation bands compared to the cemented host sandstone. (c) Porosity mask showing enhanced and band-parallel pore concentrations both within and adjacent to the deformation bands. (d) Numerical intensity profiles extracted from 3 mm-wide transects across the sample. (e) Cathodoluminescence microphotograph of a compaction band, showing the near absence of calcite cement. (f) Cathodoluminescence microphotograph of a normal-shear band, showing strongly reduced calcite content relative to the host rock.

The expected µCT response of deformation bands relative to the host rock depends on the dominant deformation mechanisms. Previous studies have shown that compaction or cataclastic bands commonly appear brighter than the host rock due to increased density and reduced porosity, e.g., [71]. However, when the density contrast is insufficient, deformation bands may show an intensity similar to that of the host rock, e.g., [62,72]. In the present case, the opposite relationship is observed, i.e., deformation bands appear darker than the host sandstone (Figure 9a). This reflects post-deformational diagenetic modification. The dominant factor controlling the µCT contrast is calcite cementation, which is pervasive in the host sandstone but largely absent within the deformation bands. This contrast is further enhanced by elevated porosity along some deformation bands, which locally reduces X-ray absorption, e.g., [73] (Figure 9c).

Locally, opening-mode fractures are observed along several normal-shear bands, indicating their partial reactivation under later stress conditions (Figure 5). This reactivation was likely facilitated by the mechanical contrast between the uncemented bands and the surrounding calcite-cemented host rock. The contrast is particularly pronounced due to the finer grain size and preferential grain alignment within the bands. Additionally, the presence and mechanical behaviour of mica may further intensify this contrast by reducing material strength and promoting instability within the granular framework, e.g., [74,75]. The locally increased number of pores along with compaction bands could be linked with the origin of secondary porosity, resulting from the dissolution of less stable grains within and along deformation bands. The orientation of pores, aligned with the orientation of deformation bands, further support this interpretation and indicate dissolution of rotated within deformation band grains. Similar observations of pores aligning within the deformation band by Rodrigues et al. [76] and Strzelecki et al. [77].

From a reservoir-quality perspective, these microstructural features have key implications. First, deformation bands represent mechanically weak surfaces that are prone to reactivation and opening, which can enhance fracture porosity during reservoir stimulation. Their orientation may also facilitate vertical connectivity within individual beds. Second, the µCT volumes reveal locally enhanced porosity along some bands, suggesting that they may act as preferential micro-pathways for fluid migration. Overall, their presence is likely to enhance reservoir quality. Such behaviour is relevant in the microporous fracture type reservoir represented by the Krosno Formation [78], where band networks can influence permeability and mechanical behaviour. Published laboratory data show that deformation bands formed at shallow burial (<1 km) typically reduce permeability by 0–3 orders of magnitude relative to highly porous host rock [79]. However, the studied sandstones are fully cemented. Such cementation alone is known to reduce permeability by an additional 2–3 orders of magnitude relative to an uncemented framework [80]. After acidizing treatments, the sandstones commonly attain 7–15 mD [81], implying that pre-treatment values may have been well below these values, probably <0.1 mD. However, precise estimates require dedicated, petrophysical measurements. Nonetheless, the presented microstructural data can serve as input for numerical models that digitally reproduce the rock sample and simulate microscale permeability evolution. When combined with deformation band spacing and orientation, such models may also be extended to reservoir scale flow behaviour.

The µCT data reveal subtle but systematic variations in grain orientation, with tilted and rotated grains maintaining a general alignment parallel to the deformation bands (Figure 6e and Figure 7d). This pattern indicates diffusive band growth through progressive granular reorganisation rather than discrete fracturing, consistent with the pervasive grain disaggregation observed in thin sections. Comparable grain rearrangement patterns in µCT data have also been described in previous studies cf. [69,81]. The Bingham distribution analysis performed on each VOI provides a quantitative statistical assessment of how grain orientations are preserved or modified within the scanned volumes (Figure 10). In the normal-shear band sample, the VOIs define a well-clustered fabric. It is characterised by eigenvalues of 0.53–0.57 (e1), 0.27–0.30 (e2) and 0.15–0.17 (e3). The high e1 values denote tightly clustered c-axes that remain aligned with the primary S0 foliation (i.e., steep c-axes). The deformation fabric, expressed as the flattening inferred from field-scale stress inversion, overlaps with the S0 foliation. However, the flattening direction (i.e., extension) is clearly highlighted by the fitted great-circle trajectories (NE–SW trends). As a result, the deformation and primary fabrics produce a strongly overlapping orientation signature. These patterns demonstrate that grain tilting associated with normal-shear band is minor and statistically subtle. This is evidenced by the density stereonets (Figure 6e) and angular statistics (Figure 10a). By contrast, the porosity VOI in the same sample displays shallow c-axes and steep ab-planes, reflecting pore alignment subparallel to the normal-shear bands.

Figure 10.

Summary projections illustrating grain arrangement. Bingham-axis distributions for the analysed VOIs are shown on lower-hemisphere stereonets with polar nets for the normal-shear band sample (a) and the compaction band sample (b). Panels (c,d) present 2D grain-orientation distributions derived from two 3 × 2 mm areas within the compaction band and normal-shear band samples, respectively. The 2D fabric analysis is based on grain orientations obtained by fitting ellipses to individual grains, corresponding to the 3D granular components.

In the compaction band sample (C1), c-axis orientations form a moderately dispersed but coherent cluster. The eigenvalues range from 0.44 to 0.51 (e1), 0.26–0.32 (e2) and 0.21–0.24 (e3). The lower e1 values relative to the normal-shear band sample indicate more diffuse fabric. This is also visible as higher dispersion on the density plots (Figure 7d). Despite this, the fabric is still dominated by steep c-axes and subhorizontal ab-planes parallel to S0. Such patterns indicate present but limited in magnitude grain tilting relative to the primary foliation. They also emphasise that the pervasive deformation fabric throughout the sample is expressed by grain rotations related to layer-parallel shortening in the microscale (Figure 10b). Most VOIs conform to this pattern. However, VOI C2, which contains a compaction band, exhibits a more inclined c-axis maximum. This records moderate local grain rotation induced by band-related strain.

The 2D results show similar general trends to the 3D data, but the deviations are greater. The main directions differ from the compaction band trend or from S0 by about 7–13°. The eigenvalues e1 are lower in the compaction band samples, ranging from 0.51 in band-affected areas to 0.56 outside the bands (Figure 10c). In the normal shear band sample, e1 reaches 0.61 to 0.62 (Figure 10d). The overall trend is preserved, but the 2D data exhibit stronger local variability, reflecting their much smaller sampling area relative to the µCT data. Pore orientation cannot be reliably assessed from the optical-microscope microphotographs, as the pores lie at the optical resolution limit, where artefacts cannot be distinguished from true pore geometry.

Combining field observations with 2D petrography and 3D µCT-derived fabric statistics provides a robust and internally consistent characterisation of strain localisation mechanisms. Importantly, the 3D µCT fabric tensors resolve spatial patterns of grain rotation and pore alignment that cannot be adequately captured in 2D sections, underscoring the unique added value of the three-dimensional approach.

6. Conclusions

- This study documents two kinematically distinct types of deformation bands within the thick-bedded sandstones of the Lower Krosno Beds in the back limb of a first-order regional buckle fold. The normal-shear bands developed within the upper and less competent unit, and the compaction bands formed within the underlying, competent unit. The normal-shear bands accommodate localised, layer-parallel extension (NE–SW), whereas the compaction bands record more pervasive layer-parallel shortening (NE-SW). These structures document early strain partitioning during the onset of folding in the Silesian Nappe.

- Microstructural and µCT analyses reveal that the bands formed at shallow burial depths (<500 m) within poorly indurated sandstones, through grain disaggregation and cataclasis. The near absence of calcite cement and the presence of smaller, reoriented grains within the bands created a strong mechanical contrast that favoured their later reactivation as fractures. Notable porosity enhancement along and within the bands is observed.

- These findings demonstrate that deformation bands are sensitive indicators of early strain localisation in folds and highlight the role of mechanical layering in governing microscale deformation mechanisms. The 3D microscale analyses are consistent with field-scale observations, and the deformation mechanisms identified in outcrops are traceable at the grain scale. The study provides geological constraints that may be used in future burial modelling and diagenetic sequence reconstruction and underscores the value of combining X-ray microtomography with petrographic methods. Moreover, the 3D µCT-based fabric analysis offers a promising basis for future numerical quantification of microscale strains.

Funding

This research was funded by National Science Centre, Poland (grant no.: 2018/31/N/ST10/02486) and supported by AGH statutory funds (subsidy no.: 16.16.140.315).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author on request.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges Anna Świerczewska, Antek Tokarski, László Fodor, and Rastislav Vojtko for their valuable guidance, constructive comments, and encouragement at various stages of this work. The anonymous reviewers are thanked for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ramsay, J.G. Folding and Fracturing of Rocks; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrill, D.A.; Smart, K.J.; Cawood, A.J.; Morris, A.P. The Fold-Thrust Belt Stress Cycle: Superposition of Normal, Strike-Slip, and Thrust Faulting Deformation Regimes. J. Struct. Geol. 2021, 148, 104362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Eckert, A.; Connolly, P. Stress Evolution during 3D Single-Layer Visco-Elastic Buckle Folding: Implications for the Initiation of Fractures. Tectonophysics 2016, 679, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świerczewska, A.; Tokarski, A.K. Deformation Bands and the History of Folding in the Magura Nappe, Western Outer Carpathians (Poland). Tectonophysics 1998, 297, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliva, R.; Schultz, R.A.; Ballas, G.; Taboada, A.; Wibberley, C.; Saillet, E.; Benedicto, A. A Model of Strain Localization in Porous Sandstone as a Function of Tectonic Setting, Burial and Material Properties; New Insight from Provence (Southern France). J. Struct. Geol. 2013, 49, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambino, S.; Fazio, E.; Maniscalco, R.; Punturo, R.; Lanzafame, G.; Barreca, G.; Butler, R.W.H. Fold-Related Deformation Bands in a Weakly Buried Sandstone Reservoir Analogue: A Multi-Disciplinary Case Study from the Numidian (Miocene) of Sicily (Italy). J. Struct. Geol. 2019, 118, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A. Small Faults Formed as Deformation Bands in Sandstone. Pure Appl. Geophys. 1978, 116, 913–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, R.A. Deformation Bands. In Geologic Fracture Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 265–331. [Google Scholar]

- Soliva, R.; Ballas, G.; Fossen, H.; Philit, S. Tectonic Regime Controls Clustering of Deformation Bands in Porous Sandstone. Geology 2016, 44, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen, H.; Schultz, R.A.; Shipton, Z.K.; Mair, K. Deformation Bands in Sandstone: A Review. J. Geol. Soc. 2007, 164, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen, H.; Soliva, R.; Ballas, G.; Trzaskos, B.; Cavalcante, C.; Schultz, R.A. A Review of Deformation Bands in Reservoir Sandstones: Geometries, Mechanisms and Distribution. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2018, 459, 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, C.; Tanner, D.C.; Fossen, H.; Halisch, M.; Müller, K. Disaggregation Bands as an Indicator for Slow Creep Activity on Blind Faults. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beke, B.; Fodor, L.; Millar, L.; Petrik, A. Deformation Band Formation as a Function of Progressive Burial: Depth Calibration and Mechanism Change in the Pannonian Basin (Hungary). Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 105, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beke, B.; Szőcs, E.; Hips, K.; Schubert, F.; Petrik, A.; Milovský, R.; Fodor, L. Evolution of Deformation Mechanism and Fluid Flow in Two Pre-Rift Siliciclastic Deposits (Pannonian Basin, Hungary). Glob. Planet. Change 2021, 199, 103434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A.; Borja, R.I.; Eichhubl, P. Geological and Mathematical Framework for Failure Modes in Granular Rock. J. Struct. Geol. 2006, 28, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, P.J.; Świerczewska, A. Wpływ Więźby Skały Na Mechanizm Deformacji: Studium Przypadku Wstęg Deformacyjnych w Piaskowcach Otryckich (Bieszczady). Przegląd Geol. 2023, 71, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballas, G.; Soliva, R.; Sizun, J.P.; Fossen, H.; Benedicto, A.; Skurtveit, E. Shear-Enhanced Compaction Bands Formed at Shallow Burial Conditions; Implications for Fluid Flow (Provence, France). J. Struct. Geol. 2013, 47, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, Y. Characteristics and Formation Process of Contractional Deformation Bands in Oil-Bearing Sandstones in the Hinge of a Fold: A Case Study of the Youshashan Anticline, Western Qaidam Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 189, 106994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujiie, K.; Maltman, A.J.; Sánchez-Gómez, M. Origin of Deformation Bands in Argillaceous Sediments at the Toe of the Nankai Accretionary Prism, Southwest Japan. J. Struct. Geol. 2004, 26, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiguchi, Y.; Ogawa, Y. Dark Bands in the Submarine Nankai Accretionary Prism—Comparisons with Miocene–Pliocene Onshore Examples from Boso Peninsula. In Accretionary Prisms and Convergent Margin Tectonics in the Northwest Pacific Basin. Modern Approaches in Solid Earth Sciences; Ogawa, Y., Anma, R., Dilek, Y., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 229–246. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhasli, S.; Zeynalov, G.; Shahtakhtinskiy, A. Quantifying Occurrence of Deformation Bands in Sandstone as a Function of Structural and Petrophysical Factors and Their Impact on Reservoir Quality: An Example from Outcrop Analog of Productive Series (Pliocene), South Caspian Basin. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2022, 12, 1977–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaji, H.; Takeshita, T. Development of Deformation Bands and Deformation Induced Weathering in a Forearc Coal-Bearing Paleogene Fold Belt, Northern Japan. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga, L.F.; Fossen, H.; Rotevatn, A. Progressive Evolution of Deformation Band Populations during Laramide Fault-Propagation Folding: Navajo Sandstone, San Rafael Monocline, Utah, U.S.A. J. Struct. Geol. 2014, 68, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, R.; Robion, P.; Souloumiac, P.; David, C.; Saillet, E. Deformation Bands, Early Markers of Tectonic Activity in Front of a Fold-and-Thrust Belt: Example from the Tremp-Graus Basin, Southern Pyrenees, Spain. J. Struct. Geol. 2018, 110, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solecki, M.L. Deformation Bands-Migration Pathways or Barriers for Hydrocarbons in Sedimentary Rocks-Mini Review. J. Geotechnol. Energy 2023, 40, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandrowski, P. Step-like Tectonic Lineation in the Magura Flysch (Western Outer Carpathians). Ann. Soc. Geol. Pol. 1980, 50, 329–339. [Google Scholar]

- Poprawa, P.; Malata, T. Model Późnojurajsko-Wczesnomioceńskiej Ewolucji Tektonicznej Karpat Zewnętrznych. Przegląd Geol. 2006, 54, 1066–1080. [Google Scholar]

- Tomek, C.; Hall, J. Subducted Continental Margin Imaged in the Carpathians of Czechoslovakia. Geology 1993, 21, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, L.; Csontos, L.; Bada, G.; Gyorfi, I.; Benkovics, L. Tertiary Tectonic Evolution of the Pannonian Basin System and Neighbouring Orogens: A New Synthesis of Palaeostress Data. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1999, 156, 295–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperner, B.; Ratschbacher, L.; Nemčok, M. Interplay between Subduction Retreat and Lateral Extrusion: Tectonics of the Western Carpathians. Tectonics 2002, 21, 1–1-1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, S.M.; Bernoulli, D.; Fügenschuh, B.; Matenco, L.; Schefer, S.; Schuster, R.; Tischler, M.; Ustaszewski, K. The Alpine-Carpathian-Dinaridic Orogenic System: Correlation and Evolution of Tectonic Units. Swiss J. Geosci. 2008, 101, 139–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golonka, J.; Krobicki, M.; Oszczypko, N.; Ślaczka, A.; Słomka, T. Geodynamic Evolution and Palaeogeography of the Polish Carpathians and Adjacent Areas during Neo-Cimmerian and Preceding Events (Latest Triassic-Earliest Cretaceous). Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 2003, 208, 138–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golonka, J.; Waśkowska, A.; Ślączka, A. The Western Outer Carpathians: Origin and Evolution. Z. Dtsch. Ges. Geowiss. 2019, 170, 229–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Książkiewicz, M. The Tectonics of the Carpathians. In Geology of Poland, IV, Tectonics; Pożarski, W., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Geologiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Oszczypko, N.; Ślączka, A.; Żytko, K. Regionalizacja Tektoniczna Polski—Karpaty Zewnętrzne i Zapadlisko Przedkarpackie. Przegląd Geol. 2008, 56, 927–935. [Google Scholar]

- Oszczypko, N. Late Jurassic-Miocene Evolution of the Outer Carpathian Fold-and-Thrust Belt and Its Foredeep Basin (Western Carpathians, Poland). Geol. Q. 2006, 50, 169–194. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski, L.; Kopciowski, R.; Wojciech, R. Geological Map of the Outer Carpathians: Borderland of Ukraine and Romania 1:200,000; Polish Geological Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 2007.

- Roure, F.; Sassi, W. Kinematics of Deformation and Petroleum System Appraisal in Neogene Foreland Fold-and-Thrust Belts. Pet. Geosci. 1995, 1, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślączka, A.; Żytko, K. Geological Map of Poland 1:200,000 (Map of Surface Deposits), Łupków Sheet; Wydawnictwo Geologiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 1978.

- Kuśmierek, J. Deformacje Grawitacyjne, Nasunięcia Wsteczne a Budowa Wgłębna i Perspektywy Naftowe Przedpola Jednostki Dukielskiej w Bieszczadach. Pr. Geol. PAN 1979, 113, 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Opolski, Z. O Stratygrafii Warstw Krośnieńskich. Spraw. Państwowego Inst. Geol. 1933, 7, 565–636. [Google Scholar]

- Bąk, K. Foraminiferal Biostratigraphy of the Egerian Flysch Sediments in the Silesian Nappe, Outer Carpathians, Polish Part of the Bieszczady Mountains. Ann. Soc. Geol. Pol. 2005, 75, 71–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ślączka, A. Explanations to the Geological Map of Poland 1:200,000; Łupków Sheet; Wydawnictwo Geologiczne: Warsaw, Poland, 1980.

- Sikora, W. Uwagi o Stratygrafii i Paleogeografii Warstw Krośnieńskich Na Przedpolu Otrytu Między Szewczenkiem a Polaną. Kwart. Geol. 1959, 3, 569–582. [Google Scholar]

- Koszarski, L.; Ślączka, A.; Żytko, K. Stratygrafia i Paleogeografia Jednostki Dukielskiej w Bieszczadach. Kwart. Geol. 1961, 5, 551–578. [Google Scholar]

- Haczewski, G.; Kukulak, J.; Bąk, K. Budowa Geologiczna i Rzeźba Bieszczadzkiego Parku Narodowego; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Pedagogicznego: Krakow, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Delvaux, D.; Sperner, B. New Aspects of Tectonic Stress Inversion with Reference to the TENSOR Program. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 2003, 212, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelier, J.; Mechler, P. Sur Une Methode Graphique de Recherche Des Contraintes Principales Egalement Utilisables En Tectonique et En Seismologie: La Methode Des Diedres Droits. Bull. Société Géologique Fr. 1977, 7, 1309–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperner, B.; Ratschbacher, L.; Ott, R. Fault-Striae Analysis: A Turbo Pascal Program Package for Graphical Presentation and Reduced Stress Tensor Calculation. Comput. Geosci. 1993, 19, 1361–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folk, R.L.; Ward, W.C. Brazos River Bar: A Study in the Significance of Grain Size Parameters. J. Sediment. Res. 1957, 27, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mees, F.; Swennen, R.; Van Geet, M.; Jacobs, P. Applications of X-Ray Computed Tomography in the Geosciences. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2003, 215, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldkamp, L.A.; Davis, L.C.; Kress, J.W. Practical Cone-Beam Algorithm. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1984, 1, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guntoro, P.; Ghorbani, Y.; Koch, P.-H.; Rosenkranz, J. X-Ray Microcomputed Tomography (ΜCT) for Mineral Characterization: A Review of Data Analysis Methods. Minerals 2019, 9, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, T.; Thorn, K.; Schroeder, T.; Wang, L.; Theis, F.J.; Marr, C.; Navab, N. A BaSiC Tool for Background and Shading Correction of Optical Microscopy Images. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarski, A.K. Geologia i Geomorfologia Okolic Ustrzyk Górnych (Polskie Karpaty Wschodnie). Stud. Geol. Pol. 1975, 48, 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinkiewicz, J. Fold-Thrust-Belt Geometry and Detailed Structural Evolution of the Silesian Nappe—Eastern Part of the Polish Outer Carpathians (Bieszczady Mts.). Acta Geol. Pol. 2007, 57, 479–508. [Google Scholar]

- Biot, M.A. Theory of Folding of Stratified Viscoelastic Media and Its Implications in Tectonics and Orogenesis. Bull. Geol. Soc. Am. 1961, 72, 1595–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudleston, P.J.; Treagus, S.H. Information from Folds: A Review. J. Struct. Geol. 2010, 32, 2042–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabavi, S.T.; Fossen, H. Fold Geometry and Folding—A Review. Earth Sci. Rev. 2021, 222, 103812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, A.; Childs, C.; Walsh, J.J.; Schafer, K.W. A Geometric Model for the Formation of Deformation Band Clusters. J. Struct. Geol. 2013, 55, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, L.; Wong, T.F.; Baud, P.; Tembe, S. Imaging Strain Localization by X-Ray Computed Tomography: Discrete Compaction Bands in Diemelstadt Sandstone. J. Struct. Geol. 2006, 28, 762–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.F.; Baud, P. Grain Crushing, Pore Collapse and Strain Localization in Porous Sandstone. In Mechanics of Natural Solids; Kolymbas, D., Viggiani, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Chen, Y.; Wong, T.F. A Discrete Element Model for the Development of Compaction Localization in Granular Rock. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2008, 113, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhubl, P.; Hooker, J.N.; Laubach, S.E. Pure and Shear-Enhanced Compaction Bands in Aztec Sandstone. J. Struct. Geol. 2010, 32, 1873–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollema, P.N.; Antonellini, M.A. Compaction Bands: A Structural Analog for Anti-Mode I Cracks in Aeolian Sandstone. Tectonophysics 1996, 267, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, R.A. Scaling and Paleodepth of Compaction Bands, Nevada and Utah. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2009, 114, B03407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, R.; Souloumiac, P.; Robion, P.; David, C. Numerical Simulation of Deformation Band Occurrence and the Associated Stress Field during the Growth of a Fault-Propagation Fold. Geosciences 2019, 9, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, P.J.; Świerczewska, A.; Kopczewska, K.; Fheed, A.; Tarasiuk, J.; Wroński, S. Decoding Rocks: An Assessment of Geomaterial Microstructure Using X-Ray Microtomography, Image Analysis and Multivariate Statistics. Materials 2021, 14, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bam, L.C.; Miller, J.A.; Becker, M. A Mineral X-Ray Linear Attenuation Coefficient Tool (MXLAC) to Assess Mineralogical Differentiation for X-Ray Computed Tomography Scanning. Minerals 2020, 10, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, L.; Baud, P.; Wong, T.F. Microstructural Inhomogeneity and Mechanical Anisotropy Associated with Bedding in Rothbach Sandstone. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2009, 166, 1063–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baud, P.; Schubnel, A.; Heap, M.; Rolland, A. Inelastic Compaction in High-Porosity Limestone Monitored Using Acoustic Emissions. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2017, 122, 9989–10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennberg, O.P.; Rennan, L. A Brief Introduction to the Use of X-Ray Computed Tomography (CT) for Analysis of Natural Deformation Structures in Reservoir Rocks. In Geological Society Special Publication; Geological Society of London: London, UK, 2018; Volume 459, pp. 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Gao, H.; Pan, Y. Stabilization of Micaceous Residual Soil with Industrial and Agricultural Byproducts: Perspectives from Hydrophobicity, Water Stability, and Durability Enhancement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 430, 136450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Gao, H.; An, R.; Yan, L. Engineering Geological Characterization of Micaceous Residual Soils Considering Effects of Mica Content and Particle Breakage. Eng. Geol. 2023, 327, 107367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Rodrigues, M.C.N.; Trzaskos, B.; Lopes, A.P. Influence of Deformation Bands on Sandstone Porosity: A Case Study Using Three-Dimensional Microtomography. J. Struct. Geol. 2015, 72, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, P.J.; Radzik, N.; Tarasiuk, J.; Wroński, S. Spatial Orientation and Shape of Pores in a Sandstone: A Case Study from the Outer Carpathians Based on X-Ray Computed Microtomography. SGEM Conf. Proc. 2018, 18, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machowski, G.; Kuśmierek, J. Influence of Fracturing on Oil- and Gas-Productivity of Microporous Flysch Sandstones. Geologia 2008, 34, 385–403. [Google Scholar]

- Ballas, G.; Fossen, H.; Soliva, R. Factors Controlling Permeability of Cataclastic Deformation Bands and Faults in Porous Sandstone Reservoirs. J. Struct. Geol. 2015, 76, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.M.; Roy, N.D.; Mozley, P.S.; Hall, J.S. The Effect of Carbonate Cementation on Permeability Heterogeneity in Fluvial Aquifers: An Outcrop Analog Study. Sediment. Geol. 2006, 184, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, P.J.; Solecki, M.L. Wpływ Mikrotekstury i Procesu Kwasowania Skały Na Jej Parametry Zbiornikowe: Studium Przypadku Piaskowców Krośnieńskich z Rejonu Dwernika, Bieszczady. Przegląd Geol. 2021, 69, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).