Abstract

The main purpose of the article is to demonstrate how large language models (LLMs) can enhance and automate the Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) method to improve the identification, assessment, and management of operational risk in modern technological systems. The study aims to show that integrating AI into FMEA increases the efficiency, precision, and reliability of detecting potential failures and evaluating their consequences, provided that expert supervision and model transparency are maintained. The research combines a literature review with a case study using OpenAI’s model to generate an automated FMEA for a manufacturing process. The methodology defines process components, identifies potential failure modes, and evaluates their risk impact. Five specialized libraries—structure, function, failure, risk, and optimization—serve as structured inputs for the LLM. A feedback mechanism allows the system to learn from previous analyses, improving future risk assessments and supporting continuous process optimization. The developed platform enables engineers to initiate projects, input data, generate and validate AI-based FMEA reports, and export results. Overall, the study demonstrates that the integration of LLMs into FMEA can transform operational risk management, making it more intelligent, adaptive, and data-driven.

1. Introduction

One of the traditional and most popular quality management methods that plays a key role in identifying and minimizing potential threats to the quality and reliability of products and processes is Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA). By analyzing each step and evaluating the results, solutions can be implemented that effectively eliminate the root causes of failures. Nowadays, the rapid development of digital technologies—including artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), data analytics, and digital twins—is creating new opportunities to transform the classic FMEA risk analysis approach into a more intelligent one. Research confirms that the FMEA method ranks among the most critical challenges in intelligent machine manufacturing and should be given unquestionable priority [1].

This article examines how emerging technologies are influencing the evolution of FMEA, making it an even more effective risk analysis method that has been widely used in various industries for many years. The main purpose of this article is to demonstrate how large language models (LLMs) can be used to enhance and automate Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) in the context of modern technologies. The hypothesis assumes that integrating large language models into the FMEA process can improve the efficiency and accuracy of failure cause and effect analysis in systems based on emerging technologies, provided that appropriate expert oversight and model transparency are ensured. Despite many studies on AI applications in FMEA, they do not exhaust the subject. A research gap has been noticed—the focus is only on individual AI techniques, and there is a lack of detailed analyses of AI implementation barriers in a real environment.

2. Literature Review

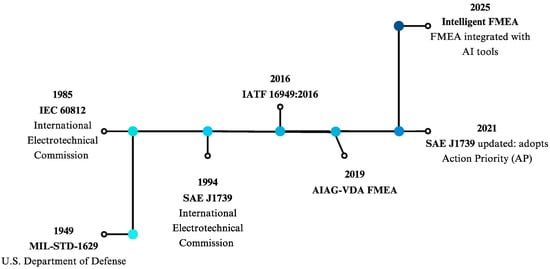

The first mentions of the FMEA method date back to the 1950s and 1960s, when the aerospace and defense industries began focusing on identifying potential failure modes in complex systems. During this period, the American military standard MIL-STD-1629 was developed. In 1985, the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) published the IEC 60812 standard, followed by SAE J1739 in 1994, which formalized the guidelines for the FMEA methodology. Today, standards such as IATF 16949:2016 mandate the use of FMEA to ensure product safety and quality, particularly in the automotive industry [2,3]. The use of Large Language Models (LLMs), such as GPT, in FMEA is a relatively new trend that has emerged in recent years. The application of modern AI tools and LLMs in this area began to develop only in the 21st century, especially at the end of the 2010s, when artificial intelligence started to gain significance. Figure 1 shows key dates and standards related to the development of the FMEA method, selected subjectively. Intelligent FMEA highlights the use of AI tools to improve the traditional FMEA process, making it more efficient and predictive.

Figure 1.

Key FMEA standards; source: own study based on [2].

However, the traditional manual approach to FMEA is time-consuming, susceptible to human error, and often inadequate for analyzing increasingly complex system [4]. These limitations underscore the growing need for more efficient, accurate, and technology-enhanced methods of conducting FMEA [5]. Like Lean, FMEA requires consistency and coherence [6].

A new standard AIAG & VDA FMEA for prioritizing FMEA introduces AP. An increasing number of studies are examining whether the number of improvement actions required increases, decreases, or remains the same when AP is used instead of RPN. One study used statistical software (Minitab https://www.minitab.com/en-us/ accessed on 13 December 2025) to simulate 10,000 combinations of both AP and RPN. The results showed a statistically significant difference between RPNs when sorted into high, medium, and low AP categories. Using an RPN threshold of 100 or higher would not change the number of required actions when prioritizing by high and medium, but would result in fewer required actions when only high values are considered. By using AP categorization instead of RPN and focusing on high APs, efforts can be reduced while targeting the elements with the greatest impact on the severity and occurrence of the problem. These elements, when improved, will have the most significant effect, making this tool even more effective [7]. The mathematical principles behind the AP table in the research standard form a framework for interpretability, offering a dependable foundation for classifying FMEA risk levels across various objects [8]. To date, there is no specific transition period for the adoption of the AIAG/VDA FMEA 2019 framework, especially for IATF certified organizations [9].

FMEA evaluation introduces a new hybrid Failure Modes, Effects, and Criticality Analysis (FMECA) model for prioritizing failure modes using the Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) method, which can serve as an alternative to the traditional Risk Priority Number (RPN) approach. This hybrid FMECA model combines the strengths of subjective assessments such as expert judgment and qualitative data with objective, quantifiable statistical information. The findings suggest that the hybrid FMECA approach offers a more robust management tool for applying risk prioritization, making it a valuable technique for engineers and risk managers [10,11].

By incorporating various criteria and expert perspectives into the development of new FMEA models, a more accurate assessment of AI-related risks can be achieved. One such model combines Picture Fuzzy Sets (PFS) with Grey Relational Analysis-TOPSIS (GRA-TOPSIS) to evaluate and rank seven identified risks. The study also suggests further research on AI risks in education, including the establishment of regulatory bodies to oversee AI usage in educational settings and promoting FMEA as a common framework for assessing AI-related risks [12].

Numerous studies have explored how AI can enhance FMEA and risk assessment. Early work by Wirth et al. [13] proposed using knowledge bases with controlled vocabularies to improve accuracy and knowledge reuse. More recent research includes Liu et al. [2], who applied multi-criteria decision-making methods, and Soltanali & Ramezani [14], who developed a hybrid FMEA model combining uncertainty quantification and machine learning. Na’amnh et al. [15] demonstrated that fuzzy inference and neural networks offer superior performance over traditional risk assessment approaches.

Recent research has leveraged machine learning to update and predict RPNs [16] and used CNNs for automating contract prioritization [17]. Yucesan et al. [18] applied fuzzy methods for risk evaluation, while Filz et al. [19] highlighted the value of combining historical maintenance data with expert input. Hodkiewicz et al. [20] improved FMEA clarity using ontological approaches.

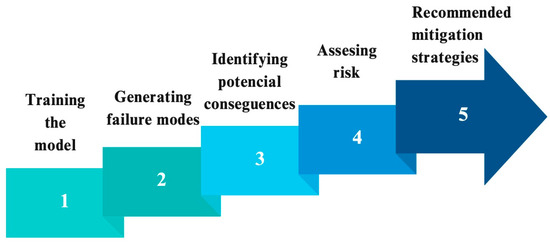

Figure 2 presents an innovative approach to improving failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA) by integrating ChatGPT (https://chatgpt.com accessed on 13 December 2025), a large language model, into the risk assessment process. ChatGPT supports key FMEA stages: generating potential failure modes, identifying consequences, assessing risk levels, and recommending mitigation strategies. Trained on historical FMEA data, the model provides fast, consistent, and intelligent support for decision-making. This AI-assisted method significantly improves the efficiency and precision of traditional FMEA, offering practical value for engineering and manufacturing applications. The findings highlight the potential of AI-human collaboration in advancing reliability and safety analysis [4].

Figure 2.

ChatGPT in FMEA action path. Source: own study based on [4].

These capabilities significantly reduce human effort, minimize errors, and increase design correctness [21]. Utilizing ChatGPT’s extensive knowledge base and advanced natural language processing capabilities, the conventional FMEA process can be substantially automated and optimized. Recent research highlights the potential and advantages of integrating ChatGPT into FMEA through a structured methodology that includes the development of a system hierarchy and the detailed representation of FMEA components using JavaScript Object Notation (JSON). This approach facilitates more accurate identification and evaluation of failure modes, thereby enhancing the precision and comprehensiveness of the overall analysis [21]. Generative Large Language Models (LLMs) have gained considerable interest since ChatGPT’s launch in November 2022. Researchers are exploring various ways to harness the potential of these LLM systems. In the domain of reliability engineering, there is promising potential for effectively applying these models [22]. AI tools like ChatGPT, combined with human expertise, can enhance FMEA, but research on integrating large language models (LLMs) remains limited. Despite progress, a comprehensive AI-based FMEA framework is still lacking, and practical implementation challenges are often ignored. Case studies are needed to explore LLM use across different FMEA phases and contexts [5].

The following part of the article presents in detail and comprehensively discusses the most important research works on AI techniques in the context of FMEA improvement and automation.

3. Materials and Methods

The main method in this article was a systematic literature review. Systematic reviews are a method for identifying and synthesizing all available existing publications [23]. The review addressed the evolution of the FMEA method, the integration of artificial intelligence tools in this process, and the associated challenges, opportunities, and risks. To guide the review, the authors formulated specific research questions aimed at addressing these themes:

- What new features or capabilities do emerging technologies bring to the traditional FMEA analyze?

- What barriers and risks are associated with using LLM in risk analysis, and how can they be mitigated?

- What specific AI techniques are currently being applied in FMEA?

The purpose of the systematic literature review (SLR) was to address the research questions outlined. The results were compiled and analyzed in the paper. As new technologies continue to evolve, so does the FMEA method—transitioning from traditional paper-based tables to spreadsheets, and now to AI-supported processes.

The second method employed in this article is a case study, which serves to deepen the understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. Case study methodology provides a structured framework for assessing and analyzing complex problems and is therefore recommended as a complementary approach to the research topic [24].

The methodology case study starts by defining process components, failure modes, and their impacts. This leads to the creation of three language libraries—components, defects, and impacts—which serve as structured inputs for an API-based query to OpenAI’s LLM that generates a draft FMEA report. APIs are evolving into the essential component of the digital landscape aiming to link companies and economies for the purpose of generating value and enhancing capabilities. The mobile app sector, recognized as one of the rapidly expanding fields within information technology, extensively utilizes APIs. Mobile app developers essentially depend on APIs to create dependable and compatible applications [25,26].

4. Results

4.1. AI-FMEA

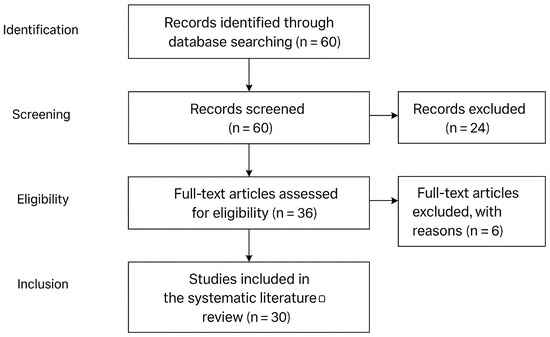

In order to obtain a comprehensive overview of the state of the art concerning the evolution of the FMEA method in the age of artificial intelligence, a systematic literature review was conducted following PRISMA guidelines. The literature search was performed using two main databases: Scopus and Google Scholar.

In the Scopus database, 46 records were initially identified as of 12 May 2025 using the keywords “FMEA” AND “AI”. After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, 22 articles were retained for full-text analysis. The Google Scholar search initially returned a higher number of records; however, after relevance verification, 14 articles closely aligned with the research scope were selected, as many others addressed AI or FMEA only tangentially.

Given the rapidly evolving nature of artificial intelligence tools, the review focused primarily on publications from the last five years. Inclusion criteria comprised peer-reviewed journal articles and conference papers written in English and explicitly addressing the application of AI techniques to FMEA or related risk analysis methods. Studies outside this scope were excluded. The final review included nearly 30 publications (Figure 3), which enabled the identification of key advantages, limitations, and best practices of AI-based FMEA approaches [5,24,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

Figure 3.

PRISMA flow diagram for AI-FMEA review; source: own study.

The analyzed studies also provided practical guidelines and recommendations for organizations adopting AI in risk management. The results summarized in Table 1 address the formulated research questions and demonstrate that the most prevalent good practice among AI techniques is the use of historical labeled data. Analysis of the collected evidence further highlights that AI primarily strengthens FMEA by improving precision and insight through automated pattern recognition, particularly in complex or high-dimensional datasets.

Table 1.

Best practices, Strengths and Limitations/Risk of AI Tool/Techniques in FMEA; source: own study based on SLR.

AI tools in FMEA have the potential to be very useful, but it is important to note that they depend heavily on high-quality data and require careful validation and interpretation. The critical importance of monitoring humans for tasks requiring high levels of creativity or technical accuracy is emphasized. These findings underscore the need for strategic integration of LLM with processes such as FMEA [35]. In this process, automation can supplement, but not replace, human knowledge [36]. The above results illustrate the potential of LLM to support structured decision-making processes similar to FMEA by extracting and organizing relevant data. However, achieving these results requires a tailored approach that leverages the power of LLM with the limitations in mind.

4.2. Platform Prototype—Case Study

4.2.1. FMEA Evaluation Table

Our case study presents an FMEA within the manual welding process. According to the new-edition AIAG and VDA FMEA Handbook, to evaluate the process in FMEA, professionals in the cross-functional team evaluate each potential failure mode based on the severity of potential effects (S), the frequency of the occurrence of potential causes (O) and the potential detection (D).

These risk indices are ranked depending on action priority (AP). Partial results are shown in Table 2, the risks are recorded in the high (H—red color), medium (M—yellow color) and in the low range (L—green color).

Table 2.

FMEA evaluation table of the manual welding (extract from PFMEA—source: own study).

After applying the corrective actions, for the optimized, the risks are recorded in the low range (L). To optimize, according to AIAG and VDA FMEA, if the AP was estimated at a high level (priority H) taking action is obligatory. If the AP is estimated at level M or L, the FMEA only recommends taking action.

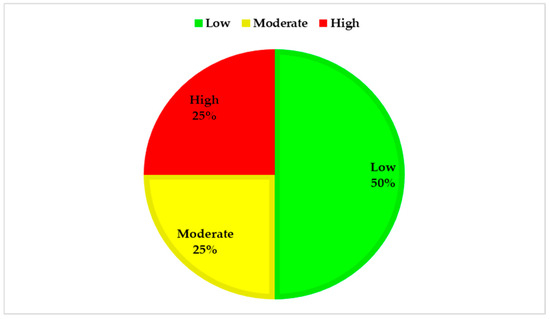

The FMEA of the welding process revealed the distribution of risk levels associated with different failure modes before the implementation of optimization measures. According to the results (Figure 4), half of the analyzed situations (50%) fall within the Low-Risk category, demonstrating that the existing control system ensures a satisfactory level of process stability. This result reflects the effectiveness of preventive maintenance for welding devices, validation of equipment at the start of production, and systematic inspections performed by operators and quality inspectors.

Figure 4.

Risk distribution diagram; source: own study.

However, a considerable proportion (25%) of cases are classified as High Risk, mainly linked to critical welding defects such as porosity and cracks, which originate from improper process parameters (e.g., gas flow rate or cooling speed). These defects can significantly affect the mechanical strength of welded components and may cause major nonconformities during customer assembly.

The Moderate Risk category, also representing 25%, includes dimensional and geometrical nonconformities typically caused by incorrect positioning of components within the welding fixture or the use of non-standard positioning devices. In these cases, the current control measures—preventive maintenance, visual inspections, and workstation audits—help to maintain risks at an acceptable level, yet they do not fully eliminate variability.

Overall, the analysis indicates that while the current control system forms a solid foundation for quality assurance, it remains insufficient for complete prevention and detection of all failure modes. The persistence of medium and high risks highlights the need to strengthen monitoring of technological parameters and to integrate digital validation tools, real-time process supervision, and AI-assisted analysis to achieve higher robustness and reliability in welding operations.

4.2.2. Presentation of the Solution

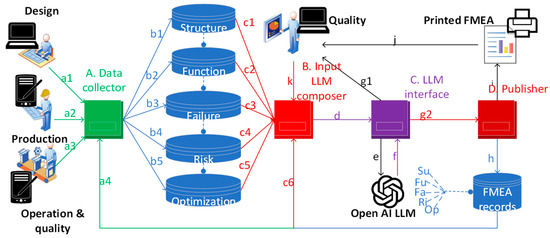

In this section, we present an implementation of an LLM-based solution for generating FMEA, applied to a welding process at an automotive manufacturer. A block diagram of the solution is shown in Figure 5, illustrating both the system components and the implemented data flow.

Figure 5.

LLM FMEA solution block diagram; source: own study.

The solution consists of four modules: Data Collector, LLM Input Composer, LLM Interface, and Publisher.

A. The Data Collector is responsible for gathering information from expert teams. In this case, the contributors include design engineers, production engineers, operators, and quality team members who monitor the production flow. The data entry form enables categorization by these five areas, which are then stored in five corresponding data collections (tables) within a database. Relationships between tables are established using linking keys. For example, a single process structure may correspond to multiple functions, and one function may involve several failure modes. The mapping between failure, risk, and optimization is one-to-one.

All input is provided through structured forms that allow the data to be organized into five main categories:

- Process Structure—includes the name of the process, its individual steps, and the work elements (execution components) involved;

- Process Function—describes each component of the process, the function of each step, and the function of the work element;

- Failure—documents the failure mode, cause of failure, and its effects, including the input or import of the severity coefficient (S);

- Risk—captures preventive and detection control types, along with the input or import of two FMEA parameters: occurrence rate (O) and detection rate (D);

- Optimization—refers to the proposed prevention and detection actions, the responsible parties, and the updated FMEA indicators.

In Another feature of this module is its ability to retrieve validated data from previously completed FMEA reports. Using a lexical matching approach (based on similarity of names via a “LIKE” mechanism), the system searches the FMEA record collection to suggest potentially relevant entries. This helps experts by offering recommendations for failure modes or similar historical processes, including the option to import prior information and indicators.

B. The LLM Input Composer is a non-AI module that connects multiple data sources and assembles them according to a predefined logic, in order to construct the input request to be sent to the LLM. Its main role is to lexically build a clear and concise phrase that accurately describes the problem for the AI module.

At the core of this phrase is the request to “perform an FMEA analysis”, based on the data collected and categorized into the five groups for the current process, as well as any relevant historical FMEA records, whether validated or not.

For validated entries, the module generates sentences like the following:

“As in process X, failure mode M with indicators I was associated with PFMEA AP.” For invalidated entries, the formulation changes to: “In process X, failure mode M with indicators I should not be associated with PFMEA AP.” This module also receives user feedback through a form confirming the validity of the currently generated FMEA report. If the report is marked as invalid, the input phrase is automatically reformulated to include: “The previously generated report is incorrect because M (reason).”

C. The LLM Interface is the module responsible for interacting with the OpenAI LLM component (ChatGPT). It receives the input prompt from the previous module and sends it to the OpenAI LLM via an API built around the Python OpenAI library version 2.9.0. The communication is asynchronous—once the response is received, it is immediately forwarded either to the quality assurance team for direct validation or to the Publisher module. Our proposed solution uses the LLM’s response in a text format structured to allow easy field separation, as described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Fields of the response provided by LLM OpenAI; source: own study.

The text response is displayed in a form for direct validation by the quality assurance team and then forwarded to the Publisher module. This approach avoids potential issues from file conversion using OpenAI libraries, relying instead on a dedicated module specifically designed for report generation.

D. The Publisher is responsible for generating the FMEA report in a printable format (.xlsm) and storing the corresponding records in the FMEA history table. This storage occurs in both cases—whether the report is validated or not—since even non-validated entries can be useful as future input references for the LLM. The Publisher generates the FMEA report, which can also serve for indirect validation. This report is sent to the quality assurance team, where it undergoes the validation process.

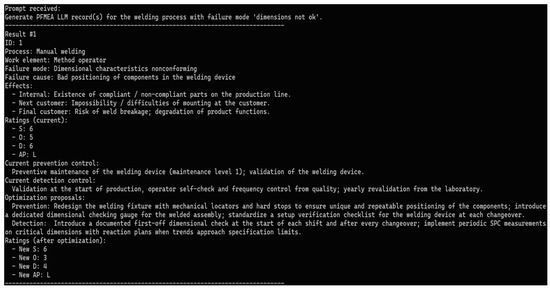

The solution uses a structured multi-role prompt consisting of Developer/System role—specifying strict behavioral constraints for the LLM (scope restricted to PFMEA reasoning, prohibition of content fabrication outside the JSON knowledge base, enforced output formatting); user role—containing the domain-specific query expressed freely by the human expert; knowledge base injection—the PFMEA records (in JSON form) are supplied to the model to anchor the reasoning process and prevent speculative hallucinations. This strategy ensures that the LLM performs semantic mapping between informal expert terminology (“customer cannot mount”, “dimensions not ok”, etc.) and the canonical PFMEA taxonomy (“Impossibility/difficulties of mounting at the customer”, “Dimensional characteristics nonconforming”), without inventing new failure modes or controls.

Our solution implements multiple layers of error handling: prompts are wrapped in an output-validation step where the model’s reply must be valid JSON containing only items matched from the knowledge base; otherwise, the result is discarded and the model is re-prompted with an explicit correction request; ambiguous or overly generic user inputs (“Generate”, “Problem with welding”) trigger a fallback clarification message; string matching is not used, instead, the solution relies on LLM semantic reasoning, which is both validated syntactically (JSON schema) and semantically (entry IDs must exist in the knowledge base).

Hallucinations are constrained through three mechanisms:

- -

- Closed-world restriction: the LLM is explicitly instructed to only return records present in the PFMEA JSON knowledge base.

- -

- Anchored retrieval: the entire base is included in the prompt, removing ambiguity about available failure modes, causes, and effects.

- -

- Output JSON schema enforcement: replies must follow a strict structure containing only existing PFMEA entries. Any deviation is treated as invalid and regenerated.

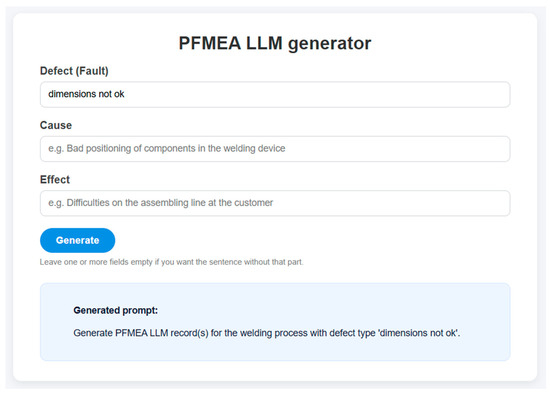

A capture from the web interface of the Input LLM composer is represented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Capture from web interface. Experts can insert fault, cause or effect in a web form and a prompt is generated—in full demo version the prompt is illustrated but in production version is automatically transmitted directly to LLM interface.

The generated prompt is sent to the LLM interface, which forwards it to the OpenAI LLM via the API. The response is then returned in the form shown in the listing in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Response from OpenAI LLM—truncated for brevity.

The application is web-based, meaning all user input forms are accessed through responsive web pages optimized for both desktop and mobile devices, including tablets. This ensures streamlined data collection through a unified, user-friendly interface.

4.2.3. Dataflow

In the LLM FMEA solution block diagram. illustrates the data flow of the solution using lowercase letters, where the order of the letters corresponds to the chronological sequence of steps.

The process begins with FMEA participants entering data through web forms. The solution allows a user with the Quality Team role to initiate a project associated with a specific process and assign specialized contributors to it. In this scenario, the contributors come from three key areas:

- Design and Development—marked as a1 in Figure 5. LLM FMEA solution block diagram.

- Production Engineering—a2.

- Operators and Quality Supervisors along the production line—a3.

Additionally, during this data collection stage, the system pulls in previous records containing similar names of processes, work elements, or failure modes (a4). All inputs are then categorized into five major analytical fields of FMEA: Structure (b1), Function (b2), Failure (b3), Risk (b4), Optimization (b5).

The data stored in these five tables then serves as input for constructing the current problem statement (c1 to c5). In parallel, the solution also incorporates information from previous FMEA records with similar content—both validated and invalidated (c6). This data is automatically provided to the LLM Input Composer, which initially performs a fully automated composition of the AI input. The formulated input is then forwarded to the LLM Interface in the form of a textual request (d), which in turn automatically sends the request to OpenAI’s LLM (e). The LLM returns a response (f), which is structured into a table-style form and routed for: direct validation by the Quality Team (g1) and storage and printable report generation by the Publisher module (g2).

The response is stored in the database (h) and used to generate a printable report (i). Optionally, the printed report may also be used for indirect validation by forwarding it to the Quality Team. In this case, the client may be involved in the validation process—the Quality Team delivers the FMEA report to the client, and validation is also expected from their side. Whether validation is performed directly (g1) or indirectly (j), the Quality Team must issue a decision (k) accepting or rejecting the report. If the report is invalidated, then after step k (and potential updates to c1...c5), the LLM Input Composer is instructed to rebuild the problem input. All subsequent input generations are initiated via k.

Steps i and j represent the final output in cases where the FMEA report is validated during step k.

4.2.4. Experimental Results

The solution was implemented as an experimental model for generating FMEA analyses applied to welding processes on truck chassis. The experiment involved five participants: a process design engineer, a production engineer (welder), a welding operator, a process quality assurance specialist, and a quality manager.

A critical aspect of the implementation was the fine-tuning of the LLM Input Composer to ensure accurate formulation of the problem input for OpenAI’s LLM. There were four initial invalid attempts for the first process, but these proved valuable in calibrating how the input prompt was constructed. These were added to the existing FMEA history, which initially included analyses for 8 welding processes on bus chassis and 12 welding processes on concrete mixer chassis, similar but not identical processes with the current one.

Once the correct input format was established, FMEA reports for the next three welding processes (also on truck chassis) were successfully generated and validated by the quality manager. This outcome highlights the potential for further development of a pilot version or even the transition to a production-ready solution. The use of LLM to determine the PFMEA Action Priority (AP) for each identified risk led to very promising results and stands out as one of the key strengths of the proposed solution—especially in the context of modern FMEA, where the traditional numeric RPN has been replaced by linguistic values. The specialists involved in the experiment greatly appreciated this outcome, reinforcing the idea that the solution has strong potential for future adoption. Table 4 illustrates an example of generated output formatted by Publish module.

Table 4.

Risk assessment using AP after recommended actions (extract from PFMEA generated—own study).

Following the implementation of the corrective and preventive actions proposed in the PFMEA, all previously identified risks were successfully reduced to the Low Risk (L) category, where 100% of the analyzed failure modes are classified as low priority (Table 5). The optimization focused on the most critical failure modes—dimensional nonconformities, missing components, porosity, and cracks—by adding advanced control and verification methods. Dimensional issues caused by non-standard welding fixtures were reduced through a Poka Yoke system, visually differentiated masks, and added self-checks and audits, lowering occurrence from 6 to 3 and keeping risk in the Low range. Missing components were addressed with AR guidance via the Supar APP, providing real-time assembly visualization and automatic verification of component presence and position. The combined AR–checklist and model-to-scan comparison reduced ratings to O = 2 and D = 2. Porosity risk was lowered through gas regulator calibration, defined gas-flow parameters, and operator training (“Welding Dojo”), supported by macrographic and leak tests that brought detection to D = 4. Cracks—identified as the most severe defect—were mitigated using automated parameter control integrated into welding equipment, locking validated settings and enabling full traceability (QR/lot). Together with visual and penetration tests and infrared temperature monitoring, occurrence and detection dropped to O = 3 and D = 4.

Table 5.

Comparison between our solution PFMEA with LLM and classic solution used before (experts with BD); source: own study.

Overall, the optimized FMEA demonstrates a stable, low-risk process supported by digital tools such as AR-based verification, automated parameter locking, and smart monitoring. These enhancements improve prevention, traceability, and operator support. OpenAI tools were also used for tasks such as generating FMEA reports in .xlsx format. Some test outputs contained irrelevant error messages (e.g., file-loading limitations), which were not recorded. To prevent recurrence of such issues, a dedicated local report-generation engine was implemented.

5. Discussion

Recent advances have transformed traditional Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) from a purely manual, spreadsheet-based method into more intelligent, data-driven workflows. A number of works have demonstrated that combining structured knowledge representations (e.g., ontologies or knowledge graphs) with AI models can significantly enhance reasoning, consistency, reusability, and automation in failure analysis [20].

With the increasing availability of sensor data and operational feedback, integrating AI into the AIAG & VDA FMEA framework offers substantial benefits. AI can support early failure detection, cluster related issues, predict emerging risks, and recommend mitigation actions based on historical data. Rather than replacing engineering judgment, AI serves to augment it—enabling systems to learn from previous FMEAs, generate preliminary analyses, and update assessments in near real time. This evolution positions FMEA as a more dynamic, continuously improving process [37,38]. What is more, AI enhances project management in automotive engineering by streamlining workflows, supporting informed decisions, and forecasting obstacles. Tools like natural language processing, machine learning, and predictive analytics enable faster development, time savings, and cost reduction [39]. Next important aspect is Smart Manufacturing and Predictive Maintenance—the integration of AI with IoT enables real-time monitoring, predictive upkeep, and automation in production. This synergy boosts operational efficiency and strengthens quality assurance across manufacturing systems [32,40]. Notably, Autonomous Driving and Road Safety—AI is pivotal in advancing autonomous vehicle technologies and safety systems. Using sensors, GPS, radar, and cameras, AI-driven systems interpret surroundings to assist or automate driving, reduce crashes, and improve overall road safety [41,42,43].

Existing research highlights that artificial intelligence possesses a transformative potential in the field of risk management. These findings reinforce the need for continued investigation into how AI can be effectively integrated into established risk assessment frameworks to enhance accuracy, efficiency, and contextual understanding [44]. Next contentious issue—Sustainability and Data Security—balancing environmental impact and data privacy is a major concern. AI can help reduce waste and energy use, contributing to sustainability goals. Ensuring compliance with global data protection standards is essential for handling information from smart vehicles [45].

A recent survey—AI- and Ontology-Based Enhancements to FMEA for Advanced Systems Engineering: Current Developments and Future Directions—shows that hybrid AI–ontology methods, combining symbolic knowledge representation with AI-driven automation, are becoming a dominant approach in modern FMEA research. This reflects an industry shift from purely manual expert-based analysis to dynamic, model-integrated, and data-rich systems [46].

Recent research shows that integrating AI—particularly in combination with structured knowledge representations such as ontologies or knowledge graphs—is transforming FMEA from a static, manual practice into a dynamic, data-driven process. Within the AIAG & VDA FMEA framework, AI enhances early failure detection, risk prediction, workflow efficiency, and continuous learning while complementing engineering judgment rather than replacing it. This evolution aligns with broader advances in smart manufacturing, predictive maintenance, sustainability, and automotive safety, highlighting AI’s growing role in modern risk management systems [47,48].

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, AI and large language models (LLMs) offer significant potential to enhance the efficiency, comprehensiveness, and objectivity of the FMEA process. The LLM-based FMEA system innovates by structuring all input into five linked categories, enabling traceable mapping between processes, functions, and failures. It leverages historical FMEA data through lexical matching to suggest relevant entries, while the Input Composer generates context-aware AI prompts with feedback-driven reformulation. Combined with asynchronous LLM interaction and automated report generation, the system supports continuous improvement and seamless expert validation.

However, it is essential to recognize their limitations and ensure that human expertise remains central to FMEA activities. By leveraging their ability to process and analyze large volumes of data, these technologies can support the identification of potential failure modes, improve risk assessment, and provide more effective and timely recommendations for corrective actions. The objectives of this article have been achieved through the implementation of a complete experimental model for FMEA report generation using OpenAI’s large language models (LLMs). Such a tool clearly streamlines the quality reporting process, which under traditional methods is often labor-intensive and time-consuming. In the current context, where numerical RPN scores are increasingly being replaced by linguistic assessments—introducing additional subjectivity and complexity into FMEA development—an LLM-based solution proves valuable not only for intelligently structuring data to produce accurate reports, but also for supporting informed risk assessment decisions for each failure mode.

Furthermore, the AI system can offer meaningful recommendations to domain specialists by leveraging knowledge derived from previously analyzed cases. In an era where the overwhelming volume of information has become increasingly difficult for humans to fully process, AI powered by LLMs emerges as a crucial and practical tool—not only for quality management, but also for broader decision-making processes. The optimized FMEA reduced all major failure modes to a stable Low-risk level through enhanced controls, AR guidance, and automated parameter monitoring. These improvements strengthened defect prevention, process stability, and traceability, while a dedicated report engine ensured reliable documentation.

The capability to automatically generate FMEA analyses in real time would enable dynamic calibration of the impact variables associated with each failure mode, allowing severity, occurrence, and detection factors to be continuously adjusted as the operating conditions of the analyzed system evolve. Such an approach would not only enhance the overall accuracy of the model, but also support early-warning mechanisms, more timely preventive actions, and continuous optimization processes, ultimately transforming operational risk management practices.

In addition, future research could explore the integration of the proposed framework with advanced streaming data processing architectures, AI models tailored for real-time anomaly detection, digital twins capable of simulating emerging and unexpected scenarios, and online learning systems that allow model parameters to be updated incrementally without full retraining. These advancements would substantially broaden the applicability of the approach across a wide range of domains, including advanced manufacturing, energy systems, automated transportation, logistics, healthcare, and critical infrastructure.

Since the LLM-based approach, supported by specialized libraries, enables the structured identification, evaluation, and mitigation of failure modes, the same underlying logic can be extended to the analysis of risks in complex systems across multiple scientific domains. For instance, in the health sciences it could be applied to assess weaknesses in clinical protocols; in environmental sciences, to model vulnerabilities within ecological systems; in the social sciences, to anticipate risks in organizational and institutional processes; and in computer science, to conduct automated assessments of software reliability and cybersecurity risks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.R., A.-V.O., A.M., N.I., L.M.I. and A.W.; methodology, K.R., A.-V.O., A.M., N.I., L.M.I. and A.W.; software, K.R., A.-V.O., A.M., N.I., L.M.I. and A.W.; validation, K.R., A.-V.O., A.M., N.I., L.M.I. and A.W.; formal analysis, K.R., A.-V.O., A.M., N.I., L.M.I. and A.W.; investigation, K.R., A.-V.O., A.M., N.I., L.M.I. and A.W.; resources, K.R., A.-V.O., A.M., N.I., L.M.I. and A.W.; data curation, K.R., A.-V.O., A.M., N.I., L.M.I. and A.W.; writing—original draft preparation, K.R., A.-V.O., A.M., N.I., L.M.I. and A.W.; writing—review and editing, K.R., A.-V.O., A.M., N.I., L.M.I. and A.W.; visualization, K.R., A.-V.O., A.M., N.I., L.M.I. and A.W.; supervision, K.R., A.-V.O., A.M., N.I., L.M.I. and A.W.; project administration, K.R., A.-V.O., A.M., N.I., L.M.I. and A.W.; funding acquisition, K.R., A.-V.O., A.M., N.I., L.M.I. and A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kałkowska, J. Inteligentne wyzwania technologii i organizacji procesów wytwarzania maszyn. In Wybrane Aspekty Zarządzania Procesami, Projektami i Ryzykiem w Przedsiębiorstwach; OnePress: Athens, Greece, 2020; pp. 67–90. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Xu, D.H.; Liu, H.C.; Song, M.S. A new model for failure mode and effect analysis integrating linguistic Z-numbers and projection method. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 29, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczewska-Kuźma, R.; Misztal, A.; Ratajszczak, K. Classification of Quality Management Methods and Tools in a Functional Approach. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Skłodowska Sect. H–Oeconomia 2024, 58, 171–186. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D. Revolutionizing failure modes and effects analysis with ChatGPT: Unleashing the power of AI language models. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2023, 23, 911–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hassani, I.; Masrour, T.; Kourouma, N.; Tavčar, J. AI-driven FMEA: Integration of large language models for faster and more accurate risk analysis. Des. Sci. 2025, 11, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakrzewska, M.; Jarosz, S. Teoretyczne i Praktyczne Aspekty Gospodarki 4.0; ArchaeGraph Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Lodz, Poland, 2022; pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Barsalou, M. Investigation into a potential reduction of fmea efforts using action priority. Manag. Prod. Eng. Rev. 2022, 4, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, W.; Nie, W. Literature review and prospect of the development and application of FMEA in manufacturing industry. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 112, 1409–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramly, E.F.; Atan, H. FMEA AIAG-VDA-Commentary and Case Study. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 10–12 March 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Belkaid, F.; Kahouadji, H.A. A New Hybrid FMECA Model for Prioritizing Failure Modes Using Multi-Criteria Decision Making. Manag. Prod. Eng. Rev. 2025, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Prajapati, D.R. Implementation of failure mode and effect analysis: A literature review. Int. J. Manag. IT Eng. 2012, 2, 264–292. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Zhang, X. AI in education risk assessment mechanism analysis. Appl. Econ. 2025, 57, 1949–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, R.; Berthold, B.; Krämer, A.; Peter, G. Knowledge-based support of system analysis for the analysis of failure modes and effects. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 1996, 9, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanali, H.; Ramezani, S. Smart failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) for safety–Critical systems in the context of Industry 4.0. In Advances in Reliability, Failure and Risk Analysis; Garg, H., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 151–176. [Google Scholar]

- Na’amnh, S.; Salim, M.B.; Husti, I.; Daróczi, M. Using artificial neural network and fuzzy inference system based prediction to improve failure mode and effects analysis: A case study of the busbars production. Processes 2021, 9, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddi, S.; Lanka, K.; Gopal, P.R.C. Modified FMEA using machine learning for food supply chain. Mater. Today Proc. [CrossRef]

- ul Hassan, F.; Nguyen, T.; Le, T.; Le, C. Automated prioritization of construction project requirements using machine learning and fuzzy failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA). Autom. Constr. 2023, 154, 105013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucesan, M.; Gul, M.; Celik, E. A holistic FMEA approach by fuzzy-based Bayesian network and best-worst method. Complex Intell. Syst. 2021, 7, 1547–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filz, M.A.; Langner, J.E.B.; Herrmann, C.; Thiede, S. Data-driven failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA) to enhance maintenance planning. Comput. Ind. 2021, 129, 103451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkiewicz, M.; Klüwer, J.W.; Woods, C.; Smoker, T.; Low, E. An ontology for reasoning over engineering textual data stored in FMEA spreadsheet tables. Comput. Ind. 2021, 131, 103496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M. Enhancing FMEA with ChatGPT: Structured Outputs, Qualitative Evaluations, and AI-Human Hybrid FMEA. In Proceedings of the Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium (RAMS), Destin, FL, USA, 27–30 January 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Goktas, Y.; Yellamati, D.D.; De Tassigny, C. The use and misuse of pre-trained generative large language models in reliability engineering. In Proceedings of the 2024 Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium (RAMS), Albuquerque, NM, USA, 22–25 January 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, J.; Van Deursen, A.; Scheerder, A. Determinants of Internet skills, uses and outcomes. A systematic review of the second-and third-level digital divide. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1607–1624. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin, J.R.; Sjober, G.; Anthony, M.O. A Case for the Case Study; UNC Press Books: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ofoeda, J.; Boateng, R.; Effah, J. Application programming interface (API) research: A review of the past to inform the future. Int. J. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2019, 15, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomba, F.; Linares-Vásquez, M.; Bavota, G.; Oliveto, R.; Di Penta, M.; Poshyvanyk, D.; De Lucia, A. (Eds.) User reviews matter! tracking crowdsourced reviews to support evolution of successful apps. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on 2015, London, UK, 3–5 September 2015; pp. 291–300. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Acqua, F.; McFowland, E., III; Mollick, E.R.; Lifshitz-Assaf, H.; Kellogg, K.; Rajendran, S.; Lisa, K.; François, C.; Karim, R.L. Navigating the jagged technological frontier: Field experimental evidence of the effects of AI on knowledge worker productivity and quality. Harv. Bus. Sch. Technol. Oper. Mgt. Unit Work. Pap. 2023, 24, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, D.; Krishnamurty, S.; Grosse, I.; White, M.; Blanchette, D. A defect prevention concept using artificial intelligence. In Proceedings of the ASME 2020 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Virtual, 17–19 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Grabill, N.; Wang, S.; Olayinka, H.A.; De Alwis, T.P.; Khalil, Y.F.; Zou, J. AI-augmented failure modes, effects, and criticality analysis (AI-FMECA) for industrial applications. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 250, 110308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, S.; Pereira Pessoa, M.; Sakwe, J.B. A FMEA based method for analyzing and prioritizing performance risk at the conceptual stage of performance PSS design. Proc. Des. Soc. 2021, 1, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommasani, R. On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.07258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A.K.; Mishra, A.K.; Kukreja, S. Role of Artificial Intelligence Enabled Internet of Things (IoT) in the Automobile Industry: Opportunities and Challenges for Society. In Proceedings of Fifth International Conference on Computing, Communications, and Cyber-Security; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chignell, M. FMEA-AI: AI fairness impact assessment using failure mode and effects analysis. AI Ethics 2022, 2, 837–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaujiya, A.K.; Tiwari, V. Addressing Public Health Challenges at Kumbh Mela 2025 in India: An FMEA-Based Resource Management Framework. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. A Phys. Sci. 2025, 95, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meron, Y.; Tekmen, A.Y. Artificial intelligence in design education: Evaluating ChatGPT as a virtual colleague for post-graduate course development. Des. Sci. 2023, 9, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.X.; Boujut, J.F.; Pourroy, F.; Marin, P. Issues and challenges of knowledge management in online open source hardware communities. Des. Sci. 2020, 6, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIAG. VDA, AIAG & FMEA Handbook—Harmonized Edition: Failure Mode and Effects Analysis for Design and Process; Automotive Industry Action Group: Southfield, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardelli, A.E.; Paolo, G. AI Risk Management: A Bibliometric Analysis. Risks 2025, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, M.; Kumar, B.S.; Deevi, D.P.; More, A.B.; Huddar, V.; Turdialiev, M.A. AI-Driven Decision Support Systems for Project Management in Automobile Engineering. In Proceedings of the 2025 First International Conference on Advances in Computer Science, Electrical, Electronics, and Communication Technologies (CE2CT), Bhimtal, Bhimtal, 21–22 February 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kodumuru, R.; Sarkar, S.; Parepally, V.; Chandarana, J. Artificial Intelligence and Internet of Things Integration in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing: A Smart Synergy. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, S.; Yadav, A.; Shazli, A.; Itoo, M.A.; Ajith, A.; Vats, D. Significance of AI in automobiles. In Smart Electric and Hybrid Vehicles: Fundamentals, Strategies and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shaterabadi, M.; Jirdehi, M.A.; Mehrjerdi, H.; Karimi, H. Artificial intelligence for autonomous vehicles: Comprehensive outlook. In Handbook of Power Electronics in Autonomous and Electric Vehicles; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ammal, S.M.; Kathiresh, M.; Neelaveni, R. Artificial Intelligence and Sensor Technology in the Automotive Industry: An Overview. In Automotive Embedded Systems, Key Technologies, Innovations, and Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yazdi, M.; Zarei, E.; Adumene, S.; Beheshti, A. Navigating the power of artificial intelligence in risk management: A comparative analysis. Safety 2024, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihail, T.A.; Emanuel, B.; Daniel, B. Artificial Intelligence Management in Mechatronic Systems in the Automotive Industry: Privacy and Sustainability Challenges. In Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Younus, H.; Kabir, S.; Campean, F.; Bonnaud, P.; Delaux, D. AI-and Ontology-Based Enhancements to FMEA for Advanced Systems Engineering: Current Developments and Future Directions. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.17743. [Google Scholar]

- Spreafico, C.; Sutrisno, A. Artificial intelligence assisted social failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA) for sustainable product design. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K.; Lorenzi, F.; Sheehan, J.D.; Kabakci-Zorlu, D.; Eck, B. Structured Document Generation for Industrial Equipment. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; AAAI Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; Volume 39, pp. 28850–28856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).