1. Introduction

Reinforced concrete structures are the most commonly used construction solution worldwide, combining the advantages of two materials—steel and concrete. Concrete effectively carries compressive forces, while steel carries tensile forces, which makes reinforced concrete applicable in almost every type of structural system. Despite well-established engineering knowledge and continuous development of material and execution technologies, the construction process of reinforced concrete structures remains susceptible to the occurrence of construction execution errors [

1]. Irregularities arising during execution may lead to serious technical consequences—including reduced load-bearing capacity, loss of structural stability, or even structural failure—before the completion of construction works [

2]. The execution phase is considered the most critical stage of a structure’s life cycle, during which the highest number of failures is reported.

The literature indicates that failures occurring during construction constitute approximately one-third of all reported cases, whereas design errors account for about one-quarter of construction failures [

3]. The most common execution errors involve improper reinforcement execution, improper formwork execution, and concreting errors. Although these errors are often local in nature, they may, in the long term, lead to concrete degradation, reinforcement corrosion, and even loss of load-bearing capacity in structural elements. Therefore, assessing the significance of execution errors is a key component of quality management systems and risk prevention in reinforced concrete works [

4]. Eliminating such errors directly contributes to improving structural reliability, durability, and safety. Accordingly, there is a need to develop tools that enable the identification, evaluation, and prioritization of execution errors in terms of their impact on structural performance and repair costs.

This study presents an analysis of execution errors occurring during the three critical stages of reinforced concrete construction: reinforcement installation, formwork assembly, and concreting. The aim of the study is to determine the significance of individual execution errors using a multi-criteria decision-making method that allows for their systematic assessment. The results may serve as a basis for developing effective quality and risk management strategies in construction processes and may contribute to improving the technologies and organization of reinforced concrete works.

Execution errors in reinforced concrete structures constitute a significant problem affecting the durability, reliability, and safety of buildings. The literature widely describes various irregularities occurring during the execution phase, which lead to the degradation of structural elements and, in some cases, complete structural failure.

Buitrago et al. [

1] analyzed 66 cases of reinforced concrete failures during construction, identifying key execution errors such as improper concrete preparation and compaction, premature formwork removal, incorrect reinforcement placement and splicing, and insufficient stability of formwork components. Their study provided one of the most comprehensive classifications of failure causes during the construction phase, highlighting areas where technical supervision must be strengthened. The authors demonstrated that more than 50% of the investigated failures resulted from execution deficiencies, particularly the improper consolidation of concrete, inadequate anchorage lengths, and incorrect reinforcement layout, which led to cold joints and loss of load-bearing capacity.

Abdul-Ameer and Alhafeiti [

2] reported that poor-quality concrete works and incorrect reinforcement detailing significantly reduce the durability of reinforced concrete bridges. Premature degradation manifested as reinforcement corrosion, cracking, and concrete delamination. Their study offered in-depth insight into the relationship between workmanship quality and long-term bridge performance. The most critical execution problems included inaccurate reinforcement placement, lack of control over concrete consistency, and improper mix preparation.

Kaltakci et al. [

5] examined failures of reinforced concrete buildings in Turkey, identifying numerous construction errors—including the use of concrete with strength lower than specified, excessive stirrup spacing, and improperly executed beam–column joints. Their analysis provided valuable documentation of recurrent patterns of deficiencies observed in real failure cases. The study revealed that inadequate material properties, insufficient reinforcement, and incorrect joint construction often compromised structural stability.

Kung [

6] investigated the causes of cracking and damage in reinforced concrete structures, showing that degradation was driven not only by corrosion but also by execution and technological errors such as incorrect mix composition and insufficient compaction. The work successfully integrated environmental, material, and workmanship-related factors, offering practical diagnostic guidance. The identified execution errors, including suboptimal concrete composition and inaccuracies in installation, contributed to microcracking and accelerated deterioration.

Szymczak-Graczyk et al. [

7] described execution errors in reinforced concrete joints of an industrial hall, identifying issues such as excessively dense reinforcement and insufficient concrete cover. Their study demonstrated the practical value of professional structural diagnostics conducted under real construction conditions. The improper reinforcement arrangement led to reduced load-bearing capacity and increased susceptibility to corrosion.

Shannag and Higazey [

8] examined the degradation of a reinforced concrete building in Riyadh, showing that the primary causes of structural deterioration were inadequate concrete strength, improper compaction, and water infiltration resulting in severe reinforcement corrosion. Their detailed assessment of an existing structure highlighted the real-world consequences of execution errors. Deficiencies in concrete properties, improper curing, and moisture penetration resulted in cracking and significant loss of structural performance.

Viegas and Real [

9] incorporated construction-related geometric and material uncertainties into the reliability assessment of reinforced concrete slabs. They demonstrated that deviations in reinforcement placement, slab thickness, and concrete cover can substantially affect structural capacity. Their probabilistic approach effectively captured realistic variability in construction quality. The most common execution-related issues included dimensional inconsistencies and uncontrolled variations in concrete properties.

In summary, the literature clearly shows that execution errors are among the most frequent causes of damage and degradation in reinforced concrete structures. Improper concreting, incorrect reinforcement placement, premature formwork removal, and lack of quality control reduce the durability of concrete, accelerate reinforcement corrosion, and decrease load-bearing capacity, which in extreme cases may lead to structural failure. Therefore, this issue constitutes an important research area within civil engineering, with direct implications for improving construction safety, work organization, and the reliability of modern reinforced concrete structures.

To date, research on execution errors in reinforced concrete structures has focused mainly on analyzing the causes of failures and describing the consequences of execution irregularities. The literature provides numerous case studies describing failures or degradation of elements caused by execution errors. However, limited attention has been paid to the quantitative assessment of the relative importance of individual execution errors in terms of their impact on safety, durability, and economic performance. There is no methodological approach that allows the comparison of different types of execution errors while simultaneously accounting for multiple technical, organizational, and economic factors. Most existing studies are descriptive or case-based and do not incorporate tools capable of objective, multi-criteria assessment. The literature lacks clearly defined criteria that would enable the prioritization of execution errors based on their significance for the reliability and quality of reinforced concrete structures. This research gap is particularly evident in the absence of comprehensive analysis that simultaneously considers factors such as the consequences of error occurrence, repairability, probability of occurrence, detectability, and cost of removal.

Multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods are widely used to address complex decision problems in construction, where technical, economic, organizational, and environmental factors are evaluated. The literature emphasizes that construction is a domain characterized by a high level of decision uncertainty, where the consequences of poor decisions may directly affect structural safety and worker health.

Janowska-Renkas et al. [

10] applied a hybrid EA FAHP–fuzzy TOPSIS approach to identify the optimal composition of high-performance concrete, integrating technical, economic, and environmental criteria. Their study demonstrated the effectiveness of hybrid MCDM methods in balancing multiple competing requirements in material design. One of the strengths of this work was the clear structuring of decision criteria and the use of fuzzy logic to capture uncertainty in expert judgment. However, the model remained highly dependent on subjective assessments, and the authors did not extend their findings to evaluate the impact of execution-related variability on material performance.

Du et al. [

11] evaluated lightweight cement mortars containing nano-additives and combined Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) with TOPSIS to support sustainable material selection. Their study illustrated the potential of integrating environmental assessment with multi-criteria decision-making and offered valuable insights into material environmental performance. Nonetheless, the analysis was limited to laboratory conditions and did not consider execution-related errors or variability occurring during real construction processes.

Mach and Wałach [

12] investigated ground improvement and piling technologies using the DEMATEL method to analyze the influence of noise, vibration, and worker safety, including social and environmental aspects. Their contribution demonstrated that DEMATEL can effectively identify interdependencies among risk-related factors in construction processes. The study, however, focused on environmental and safety issues and did not explicitly address execution deficiencies or their technical consequences.

A hybrid DEMATEL–ANP approach was employed by Wang et al. [

13] to identify relationships among safety, quality, and organizational factors. In a related study, the same authors used an HFACS–ANP model to analyze fall-from-height accidents. These works showcased the capability of hybrid MCDM frameworks to model complex causal relationships in safety management. Yet, the analyses were centered on organizational and human factor issues rather than on technical execution errors within concrete construction.

Ren et al. [

14] proposed a hybrid SNA–DEMATEL method for assessing risks in railway projects, incorporating both technical and organizational uncertainties. Their approach demonstrated strong potential in mapping network-based dependencies among risk factors. The study, however, did not address material-related or execution-related uncertainties specific to reinforced concrete structures.

Gałek-Bracha [

15] developed a hybrid fuzzy WINGS–ANP method for assessing negative impacts occurring during the sinking of caisson wells. The model enabled a detailed determination of interactions among impacts and their relative significance. Although the work presented an innovative hybrid framework with strong analytical capabilities, it focused on environmental and geotechnical effects rather than execution errors in structural elements.

Marović et al. [

16] used AHP and SAW to select the optimal formwork system for reinforced concrete structures, comparing technological options based on capacity, assembly time, and labor demand. Their results confirmed that MCDM techniques support transparent and rational decision-making in construction technology selection. The study, however, did not extend the analysis to identify or prioritize execution errors within formwork operations.

Zhang et al. [

17] developed a hybrid framework integrating machine learning with multi-criteria optimization for designing low-carbon concrete mixtures. Their study demonstrated that such an approach can effectively balance compressive strength, CO

2 emissions, and material costs while achieving high prediction accuracy.

However, the method relies heavily on large experimental datasets and does not account for execution-related uncertainties, which remain outside the scope of material-based optimization. The authors also highlighted that even optimally designed mixtures may not perform as intended if construction execution errors occur—indicating the need for methodological tools that assess workmanship-related risks.

These studies demonstrate that MCDM methods and their fuzzy extensions are effective tools for analyzing risk, quality, and safety in construction. However, no previous work has applied these methods to the assessment and prioritization of execution errors in reinforced concrete structures, despite the fact that such errors are a major source of technical and organizational risk during construction. Applying a multi-criteria approach enables the systematic evaluation and comparison of the significance of execution errors, thus addressing the existing research gap in integrated risk and quality assessment of reinforced concrete construction, and providing a useful tool for supporting quality management, organizational planning, and safety decision-making in construction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification and Characterization of Execution Errors in Reinforced Concrete Works

Execution errors in reinforced concrete structures were identified based on many years of professional experience in the construction of reinforced concrete elements, which constitutes the primary area of the author’s technical specialization. This process was supplemented with direct on-site observations from construction projects, consultations with industry experts, analyses of real failure case studies, and an extensive review of the national and international literature.

The identified execution errors were classified into three groups corresponding to the main stages of reinforced concrete construction, which enabled their systematic evaluation and detailed assessment. Three major categories of irregularities were distinguished as follows: improper reinforcement execution, improper formwork execution, and concreting errors.

This classification reflects the sequence of construction activities and allows for a structured analysis of errors according to their nature, mechanisms of occurrence, and potential consequences for structural performance.

- ❖

Improper Reinforcement Execution

- -

Insufficient concrete cover (ICC)—The primary function of concrete cover is to protect reinforcing steel against corrosion, fire exposure, and chemical attack, as well as to ensure an adequate bond between steel and concrete.

- -

Non-compliance of reinforcement layout with design documentation (NRL)—The actual spacing, quantity, or diameter of reinforcing bars differs from that specified in the design documentation; this includes excessive or insufficient spacing, missing bars, bars of incorrect diameter, incorrect orientation, or reversing the main reinforcement direction.

- -

Omission of required additional reinforcement (OAR)—Failure to install supplemental reinforcement required by the design, such as corner reinforcement, support zone reinforcement, reinforcement around openings, or supplemental bars within regions of maximum bending moments, including missing stirrups or insufficiently dense stirrup spacing.

- -

Discontinuity of reinforcing bars; insufficient lap splice length (DRB)—Reinforcing bars are not properly lapped or anchored in the splice regions; bars overlap over insufficient lengths, splices are missing where required, the anchorage length is inadequate, or splices are incorrectly arranged.

- -

Prefabrication of reinforcement not compliant with design (RPN)—Prefabricated bars do not match the required dimensions, shape, or geometry; examples include incorrect bar length, improper bend radius, wrong bending angle, missing or undersized anchorage hooks, or deformation of bars during fabrication.

- -

Insufficient number of spacer/distance bars (ISB)—Too few spacers connecting adjacent layers of reinforcement mats, resulting in improper positioning during concreting and insufficient separation between reinforcement layers.

- -

Inadequate closing (transverse) reinforcement (ICR)—Use of an insufficient number, inappropriate diameters, or improper arrangement of closing reinforcement, such as stirrups, perimeter bars, or confinement bars.

- -

Insufficient anchorage in support zones (IAS)—Failure to meet the required anchorage length or form in support regions, including insufficient embedment or excessively short anchorage of bars into the support zone.

- -

Excessive concentration of lap splices (“sheet effect”) (ELS)—Clustering of too many lap splices in a single cross-section or short segment of the structure, leading to local steel congestion and reduced concrete compactability.

- -

Contamination of reinforcement with anti-adhesive agents (CRA)—Anti-adhesive substances create an oily film on the steel surface, reducing the bond between reinforcing bars and concrete.

- -

Incorrect or insufficient tying of reinforcement with binding wire (ITR)—Too few ties between bars, loose or improperly twisted ties, incorrect tie locations, or the use of wire that is too thin or corroded.

- -

Incorrect positioning of starter bars (IPS)—Misalignment relative to the design axes, incorrect angle of placement, insufficient anchorage length, or excessive spacing between starter bars.

- ❖

Improper Formwork Execution

- -

Insufficient stiffening and support of formwork (SSF)—Incorrect installation of supports, bracing, and stiffeners; missing wedges or anchoring; or improper preparation of the base supporting the formwork.

- -

Formwork leakage (FLK)—Gaps or insufficient sealing between formwork elements causing leakage of fresh concrete during pouring.

- -

Exceeding allowable geometric tolerances of formwork (EGT)—Incorrect assembly resulting in deviations in dimensions, levels, planes, or angles beyond those permitted by standards and design documentation.

- -

Use of inappropriate or worn-out formwork elements (UFE)—Application of formwork components that do not meet strength, geometric, or quality requirements.

- -

Contamination of formwork (CWF)—Inadequate cleaning of formwork prior to concreting, including the presence of sawdust, binding wire fragments, or remnants of old concrete.

- ❖

Concreting Errors

- -

Discontinuity of concreting; excessive intervals between concrete deliveries (DCC)—Interruption of continuous placement due to long delays between concrete truck arrivals.

- -

Improper compaction of fresh concrete (PCC)—Insufficient, excessive, or incorrect vibration or compaction of the concrete mix.

- -

Incorrect execution of construction joints (ECJ)—Construction joints executed contrary to technological guidelines or design specifications.

- -

Improper placing of concrete (IPC)—Placement that causes segregation, air voids, excessive settlement, or non-uniformity; includes dropping concrete from excessive heights, uneven distribution, placing overly thick layers, or failing to adjust procedure to structural requirements.

- -

Lack of concrete curing or inadequate curing procedures (LCC)—Neglecting or improperly performing curing of fresh concrete; insufficient curing duration, lack of surface protection (foils, mats), failure to maintain moisture, or exposure of fresh concrete to sun, wind, or low temperatures.

- -

Premature formwork removal (PFR)—Removing formwork before the concrete has reached the required strength.

- -

Failure to adapt concreting technology to weather conditions (FWA)—Lack of protective measures against adverse environmental effects, such as wind, heat, sunlight, or precipitation, including failure to use covers, chemical admixtures, heating/cooling methods, or proper planning.

- -

Improper preparation of concrete mix (IPM)—Fresh concrete produced with excessive water, uncontrolled consistency, or improper performance parameters such as strength class, frost resistance, or watertightness.

- -

Exceeding the allowable time for concrete placement (ETP)—Placement occurring after the maximum permissible time from mixing.

Execution errors in reinforced concrete structures vary greatly in terms of their impact on structural safety and long-term durability. Some of them are minor and reversible, limited to aesthetic imperfections or small dimensional deviations that can be corrected during routine inspection. Others, however, may lead to serious technical consequences, such as reduced load-bearing capacity, loss of stability, accelerated material degradation, and in extreme cases even structural failure. These errors directly influence key deterioration mechanisms in concrete structures: they can accelerate carbonation, increase the likelihood of reinforcement corrosion, promote the formation of technological cracks, and impair the overall resistance of concrete to environmental actions. As a result, execution errors significantly shorten the service life of reinforced concrete structures and increase the long-term maintenance and repair costs.

It is important to stress that many execution errors are not immediately detectable. Some become visible only after prolonged service, and their identification requires engineering expertise, experience, and appropriate diagnostic techniques. Therefore, the identification, classification, and assessment of execution errors constitute a crucial step in improving construction processes for reinforced concrete structures. Such analysis not only enhances the understanding of mechanisms leading to execution-related defects but also provides the foundation for developing effective prevention and mitigation strategies. Ultimately, these efforts contribute to improving the quality, durability, and safety of reinforced concrete structures throughout their life cycle.

2.2. Identification and Definition of the Decision-Making Problem

The evaluation and comparison of execution errors in reinforced concrete structures involve addressing a multi-aspect decision-making problem that incorporates several hard-to-measure factors. Such analysis must take into account qualitative criteria, which are often imprecise, uncertain, or difficult to quantify. Factors of this nature cannot be effectively evaluated using experimental methods; therefore, expert-based assessment is widely used for their analysis [

18,

19]. Expert judgments may contain subjectivity and uncertainty, which necessitate the application of fuzzy logic elements [

20,

21].

To meet the requirements associated with the assessment of execution errors, a hybrid approach was adopted—combining the fuzzy WINGS method with the fuzzy TOPSIS method. The proposed hybrid model enables the evaluation and comparison of execution errors in reinforced concrete structures, while the incorporation of fuzzy logic allows for handling imprecise variables and uncertainty inherent in expert assessments. The core principle of hybrid methods is the ability to exploit the strengths of both combined approaches while reducing the impact of their limitations [

22].

Although the developed hybrid method was designed specifically for the assessment of execution errors in reinforced concrete works, its structure enables broader applicability and adaptation to other engineering decision-making problems.

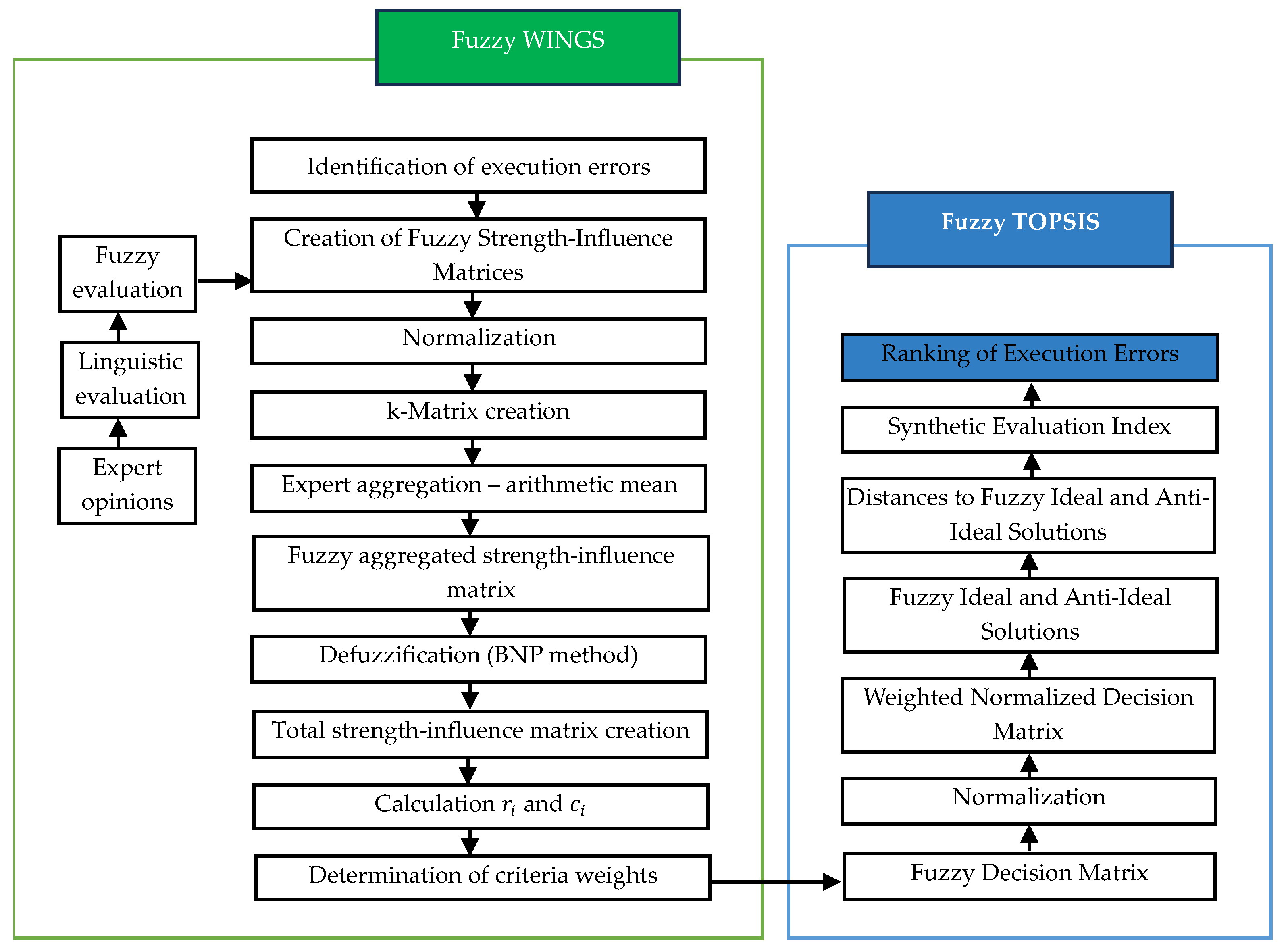

2.3. Evaluation Method

The proposed evaluation method for assessing and comparing execution errors in reinforced concrete works integrates expert-based judgment with multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) and fuzzy logic. The method determines the significance of execution errors from technical, organizational, and economic perspectives. The overall approach consists of a two-stage evaluation model. Stage I involves determining the weights of the evaluation criteria using the fuzzy WINGS method. Stage II focuses on evaluating and comparing execution errors using the fuzzy TOPSIS method.

The methodological framework introduces several key assumptions:

It enables the assessment of multi-faceted and complex decision-making problems typical for construction processes;

It allows the analysis of hard-to-measure, qualitative, or subjective factors;

It can be combined with expert-based approaches;

It adopts a simplified evaluation model—preferences are expressed through linguistic terms, which significantly streamlines data collection;

It incorporates group evaluation by aggregating expert opinions;

It supports analysis in an uncertain environment using fuzzy logic;

It provides a comprehensive evaluation and comparison of execution errors.

The hybrid use of fuzzy WINGS and fuzzy TOPSIS offers several methodological advantages over traditional MCDM techniques such as DEMATEL or AHP. While DEMATEL effectively identifies causal relationships, it does not incorporate non-linear influence propagation or an internal weighting mechanism. AHP assumes full consistency in expert judgments and a strictly hierarchical structure, which is rarely applicable to construction errors that interact across technological and organizational dimensions.

In contrast, fuzzy WINGS captures both direct and indirect influences between criteria using a non-linear gauge system, allowing for more realistic modeling of interdependencies such as how “repairability” affects the perceived severity and cost of errors. This makes WINGS particularly suitable for construction error analysis, where criteria are strongly coupled. Fuzzy TOPSIS complements WINGS by enabling the ranking of alternatives based on their similarity to the ideal solution, providing a clear and interpretable measurement of error criticality. The hybrid model therefore improves robustness, reduces subjective bias, and enhances the precision of decision-making under uncertainty.

The individual stages of the hybrid method are illustrated in

Figure 1.

In the first stage, the fuzzy WINGS (Weighted Influence Non-linear Gauge System) method [

23] was applied to determine the importance of the evaluation criteria. This method is used to identify the mutual relationships and internal significance of the criteria. The significance and influence of the criteria were assessed using an expert-based approach that relied on the knowledge and professional experience of the previously appointed experts. Expert evaluations were used to construct the direct influence map [

24,

25], which reflects the interactions and dependencies between the selected criteria.

A group aggregation procedure was applied to the expert ratings, which required the use of expert assessment throughout the analysis. To appropriately address the uncertainty inherent in expert-based evaluation, a fuzzy extension of the method was adopted. In this extension, triangular fuzzy numbers and a linguistic rating scale were used to model the imprecise and uncertain nature of expert judgments. The linguistic scale facilitates the experts’ assessment process, and in subsequent steps, these linguistic terms are transformed into corresponding triangular fuzzy numbers.

The linguistic rating scale with the associated triangular fuzzy numbers used in the study is as follows:

No influence—(0, 0, 1);

Low influence—(0, 1, 2);

Medium influence—(1, 2, 3);

High influence—(2, 3, 4);

Very high influence—(3, 4, 4).

The linguistic scales and corresponding triangular fuzzy numbers used in this study were derived following widely accepted fuzzy MCDM practices [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Similar parameterizations have been applied in engineering decision-making where expert uncertainty must be modeled. The adopted triangular numbers preserve monotonicity and equal linguistic spacing, ensuring comparability between linguistic grades. Their structure is consistent with fuzzy AHP, fuzzy DEMATEL, and fuzzy TOPSIS applications in civil engineering, where five-level linguistic scales are the dominant standard.

Based on the expert evaluations, a set of fuzzy direct influence matrices , for where , are constructed; these are triangular fuzzy numbers with a membership function representing the fuzzy assessment of the relationship between criterion i and criterion j, as evaluated by the k-th expert. The main diagonal of the matrix consists of the elements , which represent the intrinsic importance of each criterion.

The off-diagonal elements

,

describe the cause–effect relationships between the analyzed criteria.

The fuzzy direct-relation influence matrix

requires normalization as follows:

where

denotes the normalization factor,

Next, the elements of the normalized fuzzy direct-relation influence matrix are defined using the vector:

The next step of the method consists of determining the fuzzy total influence matrix

, which is calculated according to the following formula:

denotes the identity matrix:

If a group of k experts participates in the analysis, k total influence matrices must be determined.

The matrices are introduced separately, bounded on the left (l), at the apex (m), and on the right (u).

To obtain an unambiguous solution, the arithmetic mean method is used for aggregating expert evaluations [

18]. This approach can be applied when the experts’ assessments do not exhibit tendencies toward overestimation or underestimation. The fuzzy arithmetic mean operator is determined as follows [

31]:

The aggregated fuzzy total influence importance matrix is expressed as follows:

where

denotes the triangular fuzzy numbers with the membership function

In the subsequent steps of the method, the fuzzy matrix

is defuzzified using the BNP (Best Non-fuzzy Performance) method [

32,

33].

After the defuzzification process, the total influence matrix

is obtained. This matrix is then used to calculate the total influence

of the

-th factor and the total dependence (susceptibility)

of the

-th factor.

where

denotes the elements of the matrix

. Subsequently, the sum

and the difference

are calculated.

In the second stage of the proposed model, the fuzzy TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution) method [

34] was applied to evaluate and compare construction execution errors in reinforced concrete works. The fuzzy TOPSIS method enables the analysis of multiple decision alternatives (execution errors) while considering multiple criteria and the uncertainty inherent in expert-based assessments.

The essence of fuzzy TOPSIS lies in determining the ideal and anti-ideal solutions and subsequently evaluating the similarity or dissimilarity of each alternative to these reference points. In the fuzzy environment, these reference points are defined using triangular fuzzy numbers, which makes it possible to account for ambiguity, imprecision, and gradation in expert judgments.

Similar to the previous stage, the intensity of influence assessments was established using an expert analysis. Expert evaluations were aggregated to obtain a collective assessment. To facilitate the rating process, a linguistic scale was introduced. The linguistic terms were then transformed into corresponding triangular fuzzy numbers. The linguistic rating scale and its associated triangular fuzzy numbers are defined in

Table 1.

Based on the expert evaluations, a fuzzy decision matrix is constructed, in which all assessments are expressed as triangular fuzzy numbers with a triangular membership function .

The rows of the decision matrix represent the decision alternatives (i.e., the construction execution errors), while the columns correspond to the evaluation criteria.

In the next step, the fuzzy decision matrix is normalized as follows:

Next, the normalized weighted decision matrix must be constructed. The weights are introduced according to the following formula:

for , …. m; , …. n.

Next, the distances of each alternative from the ideal and anti-ideal solutions are calculated as follows:

The final stage consists of determining the synthetic evaluation measure and establishing the ranking of the assessed alternatives.

3. Application of the Fuzzy WINGS–Fuzzy TOPSIS Method for the Evaluation and Comparison of Construction Errors in Reinforced Concrete Works

3.1. Identification of the Set of Factors

The set of factors used in the analysis consists of the previously identified and defined execution errors occurring in reinforced concrete works, namely the following:

- ❖

Improper reinforcement execution:

- -

Insufficient concrete cover (ICC)—Inadequate thickness of cover protecting reinforcement against corrosion, fire, chemical exposure, and ensuring a proper bond between steel and concrete.

- -

Non-compliance of reinforcement layout with design documentation (NRL)—Actual spacing, quantity, or bar diameters differ from the design; excessive or insufficient spacing, missing bars, incorrect diameters, misplacement, or improper direction of main reinforcement.

- -

Omission of additional reinforcement required in the design (OAR)—Failure to install supplemental bars such as corner reinforcement, support reinforcement, opening reinforcement, beam–slab joint reinforcement, concentrated stirrups, etc.

- -

Discontinuity of reinforcing bars; insufficient lap splice length (DRB)—Bars not properly overlapped or anchored; insufficient lap length, missing splices, inadequate embedment, or misplaced splice zones.

- -

Prefabrication of reinforcement not compliant with design specifications (RPN)—Reinforcement fabricated with incorrect dimensions or geometry: improper cutting lengths, incorrect bending radius, wrong bend angle, missing or incorrect hooks, deformation of bars.

- -

Insufficient number of spacer/distance bars (ISB)—Too few spacers ensuring proper separation of reinforcement layers and maintaining the designed positioning during concreting.

- -

Inadequate closing (transverse) reinforcement (ICR)—Insufficient number, incorrect diameters, or improper arrangement of stirrups, perimeter, or tying bars.

- -

Insufficient anchorage in support zones (IAS)—Failure to provide required anchorage length and shape in support regions; insufficient embedment of bars.

- -

Excessive concentration of lap splices in one location (“sheet effect”) (ELS)—Accumulation of many spliced bars in one section, causing local congestion and ineffective load transfer.

- -

Contamination of reinforcement with anti-adhesive agents (CRA)—Presence of oils or form-release agents reducing the bond between steel and concrete.

- -

Incorrect or insufficient tying of reinforcement with binding wire (ITR)—Loose, inadequate, incorrectly placed, or insufficient wire ties; use of corroded or undersized tying wire.

- -

Incorrect positioning of starter bars (IPS)—Misalignment with design axes, improper embedment length, incorrect spacing or angle of starter bars.

- ❖

Improper formwork execution:

- -

Insufficient stiffening and support of formwork (SSF)—Improper bracing, shoring, or stabilization; missing wedges, anchors, or insufficient substrate preparation under supports.

- -

Formwork leakage (FLK)—Insufficient tightness of joints leading to leakage of fresh concrete.

- -

Exceeding allowable geometric tolerances of formwork (EGT)—Deviations in dimensions, levels, planes, or angles exceeding limits defined in standards and design documentation.

- -

Use of inappropriate or worn-out formwork elements (UFE)—Use of elements that do not meet strength or geometric requirements.

- -

Contamination of formwork (CWF)—Presence of sawdust, binding wire fragments, hardened concrete residues resulting from inadequate cleaning.

- ❖

Concreting errors:

- -

Discontinuity of concreting; excessive intervals between concrete trucks (DCC)—Interruption of concreting due to long time gaps between concrete deliveries.

- -

Improper compaction of fresh concrete (PCC)—Insufficient, excessive, or non-uniform vibration of fresh concrete.

- -

Incorrect execution of construction joints (ECJ)—Construction joints made improperly or contrary to technological and design guidelines.

- -

Improper placing of concrete (IPC)—Placing concrete in a manner causing segregation, voids, excessive drop height, uneven distribution, too thick layers, or lack of adaptation to the structural configuration.

- -

Lack or improper curing of concrete (LCC)—Insufficient or incorrect curing; failure to protect fresh concrete against drying, temperature effects, sun, wind, or frost.

- -

Premature formwork removal (PFR)—Stripping formwork before the concrete reaches the required strength.

- -

Failure to adapt concreting technology to weather conditions (FWA)—Lack of protective measures during concreting under adverse environmental conditions.

- -

Improper preparation of concrete mix (IPM)—Mix produced with incorrect parameters (excess water, incorrect workability, strength class, frost resistance, watertightness).

- -

Exceeding the allowable time for concrete placement (ETP)—Placing the mix after an excessive time from mixing, causing loss of workability and improper bonding.

3.2. Definition of the Set of Criteria

The criteria used to evaluate and compare execution errors in reinforced concrete structures were selected deliberately, taking into account the specificity of the decision-making problem as well as the technical, organizational, and economic consequences associated with execution irregularities. The criteria were identified on the basis of many years of practical experience gained by the author during the execution of reinforced concrete structures, supplemented by consultations with industry experts specializing in concrete construction technology. The selection of criteria aimed to capture the influence of errors on structural safety, their organizational and economic implications, and the detectability of irregularities during construction inspection.

Considering the differing nature and scope of possible remedial actions, the sets of criteria were adjusted to the specificity of each group of execution errors.

For Groups I and II, six evaluation criteria were adopted. Experts emphasized that repair procedures depend strongly on the moment when the error is detected. Therefore, the cost-related criterion was divided into two separate criteria. The criteria used for Groups I and II were as follows:

Consequences—The potential impact of the irregularity on the safety, load-bearing capacity, durability, and functional performance of the structure.

Repairability (inspection stage)—The extent to which the element can be restored to compliance with design requirements once the irregularity is detected.

Probability of occurrence—The frequency or likelihood of the error appearing during reinforced concrete works.

Detectability during inspection—How easily the error can be identified during or after the construction process.

Cost of removal before concreting—The financial, material, and organizational effort required to eliminate the error prior to concrete placement.

Cost of removal after concreting—The financial, material, and organizational effort necessary to eliminate the error once concrete has been placed.

This approach reflects the real decision-making environment on construction sites, where errors related to reinforcement installation and formwork execution may be detected either before or after casting the concrete mix, which significantly affects the associated repair costs.

For the third group of errors—concreting errors—five criteria were adopted. Unlike in the previous groups, the cost criterion was not split into two stages (before and after concreting). This decision results from the fact that concreting errors become visible only after the concrete has set, and therefore the possibility of correction before concreting does not exist. Accordingly, the following evaluation criteria were established:

Consequences—The potential impact of the irregularity on the safety, load-bearing capacity, durability, and functional performance of the structure.

Repairability (inspection stage)—The technical possibility of restoring the element to the required condition after the error is identified.

Probability of occurrence—The likelihood or frequency of the error occurring during concrete works.

Detectability during inspection—The ease with which the error can be identified during or after works.

Cost of removal—The financial, material, and organizational effort necessary to eliminate the consequences of the error.

3.3. Determination of the Expert Sample

An expert-based survey method was adopted in this study, as the assessment and comparison of execution errors in reinforced concrete structures involve complex issues and factors that are difficult to measure directly and cannot be reliably verified using experimental or numerical data alone. Execution errors occur in a dynamic construction environment, where practical conditions, organizational constraints, and the professional experience of the personnel involved play a significant role. In such cases, the most reliable source of information is the specialized knowledge of individuals with long-standing experience in the supervision, design, and execution of reinforced concrete works.

The expert method made it possible to obtain assessments that reflected a practical understanding of the consequences of execution errors, the real detectability of irregularities on construction sites, common technological and organizational constraints, and the challenges associated with repair actions and their economic implications. No normative classification criteria or statistical datasets describing the frequency of execution errors and their structural impact were identified in the literature. Therefore, the use of expert judgment based on extensive industry experience is justified and aligns with widely accepted practices in multi-criteria decision-making and risk assessment. Consequently, the expert method was considered the most appropriate tool for gathering information essential for evaluating and comparing execution errors, particularly in an area that remains insufficiently documented in research and not standardized in engineering practice.

The collection of expert assessments was conducted in two stages: a pilot study and the main survey. This approach ensured high-quality input data for the multi-criteria analysis and allowed verification of the research instrument. The pilot study was carried out with six experts who evaluated the preliminary version of the linguistic rating scale and the formulation of the questionnaire items. The pilot results highlighted the need to refine and extend the rating scale to provide more detailed descriptions and clearer level differentiation. After consultations, modifications were introduced to improve the clarity and precision of the linguistic terms, facilitating subsequent interpretation of fuzzy linguistic values.

Following the pilot phase, the main survey was carried out, again involving six experts who completed the revised questionnaire. The questionnaire, distributed electronically, was provided in the form of a text document. Experts were informed about the purpose of the study, the principles of evaluating each criterion, and received guidance on the assessment methodology.

A purposive sampling strategy was used for expert selection. Random sampling was not applied, as the topic—execution errors in reinforced concrete construction—requires highly specialized, practical knowledge that cannot be ensured through random selection. Purposive sampling enabled the inclusion of individuals with verified competencies, thus increasing the reliability and substantive value of the collected data. Initially, ten experts were nominated; however, four were excluded after evaluating their qualifications. The final group consisted of six experts whose technical knowledge and practical experience in reinforced concrete works ensured the credibility of the assessments.

Experts selected for the study had a minimum of five years of professional experience in reinforced concrete construction, with most having more than ten years of practice. The experience structure was as follows: one expert with 15–20 years of experience, three experts with 10–15 years, and two experts with 5–10 years (specifically 8 and 9 years). The majority were site managers or construction managers (five individuals). One expert represented the group of construction works contractors involved in the supervision and organization of construction processes. The data collected through the questionnaires constituted the basis for further analysis using the fuzzy WINGS and fuzzy TOPSIS methods.

The questionnaire consisted of three sections. The first section addressed execution errors related to improper reinforcement installation and included 12 questions. The second section concerned errors related to improper formwork execution and included five questions. The final section focused on concreting errors and contained nine questions. In total, the questionnaire comprised 26 questions, with each execution error evaluated according to the previously defined criteria.

Experts assessed the execution errors using a five-level linguistic descriptive scale, as described in the preceding section. The linguistic scale simplified the decision-making model. In subsequent stages of the analysis, the verbal assessments were converted into numerical values. It must be emphasized that expert assessments may include uncertainty and subjective judgment, as experts are not always fully confident about the accuracy of the ratings assigned. This inherent uncertainty necessitated the use of fuzzy logic. Therefore, linguistic evaluations were replaced with triangular fuzzy numbers, and group aggregation of expert opinions was performed using the arithmetic mean.

To determine the criterion weights, an expert-based procedure employing fuzzy WINGS was applied. The assessment process consisted of two stages: determining the importance of each criterion and evaluating the interrelations and influences between the criteria. In the first stage, individual interviews were conducted with each expert, during which the significance of all criteria was discussed in the context of execution errors occurring in reinforced concrete structures. Experts assigned importance ratings to the criteria. In the second stage, experts performed pairwise comparisons to assess the mutual influence of the criteria. They evaluated whether a given criterion affects another and, if so, to what extent. The same linguistic scale used in the fuzzy WINGS method (no influence, low influence, moderate influence, high influence, very high influence) was applied, ensuring standardization and facilitating subsequent aggregation.

This process enabled capturing expert knowledge in the form of fuzzy numbers, allowing for modeling uncertainty and subjectivity. Conducting individual consultations ensured that experts could discuss interdependencies between criteria in depth, using their extensive practical experience in reinforced concrete construction. As a result, the collected data reflect real engineering practice rather than abstract hierarchical structures.

The linguistic ratings were then converted into fuzzy numbers and aggregated using a group aggregation operator. The final influence matrix and the criterion importance matrix served as input data for the fuzzy WINGS model, which allowed for the computation of criterion weights accounting for their significance and mutual interdependencies.

3.4. Results and Discussion

In the first stage of the analysis, using the fuzzy WINGS method, the values of the total influence

and total dependence

, as well as their absolute values, were obtained. These quantities were subsequently used to calculate the weights of the individual evaluation criteria. The results are presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

Table 2 contains the criterion weights for Groups I and II of execution errors, i.e., improper reinforcement execution and improper formwork execution.

Table 3 presents the criterion weights for Group III, relating to concreting errors.

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 present the aggregated fuzzy evaluations assigned by the experts for the decision alternatives, expressed within the categories of the individual criteria.

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9 present the distances of the individual construction errors from the ideal and anti-ideal solutions, as well as the synthetic performance scores and the resulting rankings. A separate ranking was developed for each group of construction errors. For clarity of data presentation, the execution errors were denoted using acronyms, which allows the results of the analysis to be presented in a more readable and concise manner.

The conducted analysis made it possible to determine the significance of individual construction errors within the group of errors related to reinforcement installation. The obtained values of the synthetic evaluation index ranged from 0 to 1, enabling an unambiguous assessment of the impact of each error on the safety and quality of the reinforced concrete structure. In this approach, a higher value of the synthetic index indicates greater significance of the error and more severe potential consequences of its occurrence. Numerical values close to 1.0 highlight the highest significance of a given execution error, emphasizing its potentially substantial impact on the development of structural damage. Conversely, values close to 0.0 indicate low significance, suggesting that the error had only a negligible effect on the condition and performance of the reinforced concrete elements. Based on

Table 7 and

Figure 2, it can be concluded that within the group of reinforcement execution errors, the most critical error was insufficient concrete cover (ICC), which achieved a score of 0.89. The insufficient concrete cover (ICC) obtained a score of 0.89, which is close to the ideal value (1.0), indicating that this error has the highest negative impact on structural durability and safety among all reinforcement-related defects. This error promotes reinforcement corrosion and has a significant adverse effect on durability. High significance was also obtained for non-compliant reinforcement layout (NRL)—0.82—and discontinuous reinforcement/improper lap length (DRB)—0.81. These errors directly affect structural behavior under load and may lead to premature cracking or even structural failure.

A group of medium–high significance errors scoring between 0.76 and 0.58 included reinforcement prefabrication not compliant with design (RPN), insufficient anchorage in support zones (IAS), and omitted additional reinforcement (OAR). Errors receiving intermediate significance (0.40–0.50) were those that can typically be detected and corrected before concreting, such as insufficient number of spacers (ISB), excessive concentration of laps (ELS), and contamination of steel with release agents (CRA).

The lowest significance values were assigned to errors that are easy to detect and correct before concreting, such as insufficient closing reinforcement (ICR), incorrect positioning of starter bars (IPS), and improper or insufficient tying of reinforcement (ITR), which scored between 0.19 and 0.40.

In summary, the most critical errors are those relating to the essential structural parameters of reinforcement: cover, anchorage, and continuity. Errors related to local geometric inaccuracies or improper installation achieved medium values. The least significant errors are those that are easily detectable and repairable before concrete placement. The greatest risk is associated with errors that become difficult or impossible to repair once the concrete has hardened.

The analysis of formwork execution errors (

Table 8 and

Figure 3) indicates considerable variation in the significance of individual errors. The synthetic evaluation index ranged from 0.31 to 0.94, reflecting a wide range of effects that these errors may have on the quality and safety of the constructed reinforced concrete elements.

The highest score was obtained for exceeding permissible geometric deviations of formwork (EGT)—0.94. This is a highly significant error because it directly affects the geometry of the constructed element. Excessive geometric deviations may lead to serious structural defects and, in extreme cases, require partial demolition of the element. High significance also characterized insufficient stiffening and support of formwork (SSF)—0.62—as well as formwork leakage (FLK) and use of inappropriate or worn formwork components (UFE)—both scoring 0.57.

Insufficient formwork stiffness is one of the primary causes of permanent deformations and surface defects. Leakage results in reduced concrete durability and material loss. Using worn or inadequate formwork elements increases the risk of deformation and causes difficulties in achieving the required surface quality and element geometry. Despite being frequently associated with cost optimization on construction sites, it may lead to severe quality defects.

The lowest significance was found for contaminated formwork (CWF)—0.31. Although undesirable, its impact on the safety and durability of the element is limited, usually resulting in local or aesthetic defects. It is easily detectable and can be removed before concreting.

In summary, the most significant errors are those related to formwork geometry, stiffness, and load-bearing capacity. The results indicate that ensuring adequate stiffness, stability, and dimensional accuracy of formwork, as well as using components in good technical condition, is essential to achieve high-quality and safe construction.

The analysis of concreting errors (

Table 9 and

Figure 4) revealed synthetic evaluation index values ranging from 0.02 to 0.35. The significance of errors in this group is diverse but generally lower than in the case of reinforcement or formwork errors. This results from the fact that many concreting errors can be mitigated through on-site supervision and some of their consequences are surface-related or repairable.

The highest significance was recorded for discontinuity of concreting (DCC)—0.35. This error is particularly dangerous as it leads to weakened interfaces between layers, reduced watertightness, and structural surface defects (cold joints, cracking, scaling, discoloration). A similar value was obtained for improper execution of construction joints (ECJ)—0.34—which may be especially critical in elements subjected to shear or bending forces.

Improper preparation of the concrete mix (IPM) scored 0.29. This affects compressive strength, frost resistance, and watertightness, and its consequences are difficult to reverse. Inadequate compaction of concrete (PCC)—0.19—and improper placement of fresh concrete (IPC)—0.11—received medium significance. These errors may lead to voids, segregation, and an uneven internal structure. Although they reduce durability, they can usually be mitigated by proper supervision.

Lower significance was assigned to lack of curing or improper curing (LCC)—0.07—and premature formwork removal (PFR)—0.04. These errors can cause surface cracking and reduced strength, but the effects are typically local. Failure to adapt concreting to weather conditions (FWA)—0.02—and exceeding allowable placement time of concrete (ETP)—0.10—are relatively easy to monitor and prevent through proper planning.

Overall, the results indicate that the most critical concreting errors are those that compromise structural continuity and integrity, followed by errors related to mix preparation and consistency.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted by modifying the weights of the criteria. The aim was to assess the stability of the ranking of construction errors under varying decision-maker preferences and to determine the extent to which the final classification depends on the adopted weights.

Reinforcement errors with the highest scores (insufficient cover, incorrect placement, and bar discontinuity) are directly linked to fundamental principles of structural mechanics. Insufficient cover accelerates corrosion, leading to loss of the steel area and bond deterioration. Incorrect spacing or misplacement changes the internal lever arm and reduces the bending and shear capacity. Bar discontinuities or inadequate lap lengths interrupt force transmission, which is critical for serviceability and ultimate limit state behavior. These errors are also difficult to repair once concrete is placed, which explains their high ranking. Formwork errors related to geometric deviations scored highest because they directly affect cross-sectional dimensions and, therefore, stiffness and load capacity. In contrast, concreting errors scored lower because many of them can be mitigated through on-site supervision, although discontinuous concreting and poor joint execution remain critical due to their long-term impact on durability and permeability.

The approach consisted of reducing the weight of the most important criterion by 10%. After adjusting and normalizing the weights, the following sets were obtained:

Improper reinforcement and formwork execution: 0.174, 0.173, 0.183, 0.183, 0.183, and 0.102 (

Table 10 and

Table 11). Concreting errors: 0.195, 0.206, 0.196, 0.196, and 0.206 (

Table 12). These sets constituted a modified weight vector used for a repeated fuzzy TOPSIS procedure. The analysis confirmed the stability of the results, as no significant changes were observed across the three rankings. This demonstrates the robustness and reliability of the proposed model, confirming that minor changes in weighting do not significantly affect the classification of construction errors.

4. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive analysis of construction errors occurring during the execution of reinforced concrete structures. The errors were classified into three groups: improper reinforcement execution, improper formwork execution, and concreting errors. A hybrid decision-making model was developed by combining the fuzzy WINGS and fuzzy TOPSIS methods. The proposed model enabled the evaluation of individual construction errors with respect to five or six decision criteria, covering technical, organizational, and economic aspects. The results confirmed that the impact of construction errors on the reliability of reinforced concrete structures is highly differentiated and strongly dependent on the nature of the error.

Within the group of reinforcement-related errors, the highest significance was assigned to irregularities that directly affect structural behavior and reinforcement durability, such as insufficient concrete cover, non-compliant reinforcement layout, and discontinuous reinforcement (including inadequate lap length). For formwork errors, the dominant factor was excessive geometric deviations, which are critical for the shape and load-bearing capacity of structural elements. Within concreting errors, the most significant issues were discontinuity of concreting and improper compaction—both of which can lead to serious structural defects and reduced durability.

The proposed multi-criteria model proved to be an effective tool for identifying the influence of construction errors on structural safety, durability, and the costs of potential repairs. The study addresses a research gap related to the quantitative and systematic evaluation of execution errors in reinforced concrete construction, which have until now been analyzed primarily using descriptive or qualitative methods. The research introduces an innovative hybrid approach by integrating fuzzy WINGS and fuzzy TOPSIS. The model accounts for uncertainty, supports the evaluation of hard-to-measure factors, and incorporates group expert judgment, thereby increasing the reliability of the results. The findings have substantial practical importance.

The developed ranking of construction errors may support site managers, supervision engineers, and designers in quality planning, execution control, and risk management. Identifying the most critical errors enables more effective resource allocation, improved technical supervision, and the implementation of preventive measures.

The study has certain limitations, primarily related to the number of experts involved and the focus on specific groups of errors under conditions typical of reinforced concrete construction. Because the objective of the research was methodological—to develop, structure, and validate a hybrid fuzzy WINGS–TOPSIS model—the analysis relied on expert-based linguistic assessments rather than on-site measurements or quantitative error frequency data. Collecting empirical datasets would require long-term monitoring across multiple construction sites, which falls outside the scope of the present study but is planned as a future research direction. Such longitudinal investigations will enable model calibration, verification of rankings, and refinement of parameterization once sufficient real-world data become available.

Future research could extend the model by adding further decision criteria and considering different structural types and construction technologies. A broader empirical validation will strengthen the model’s practical applicability and support the development of more comprehensive risk assessment frameworks for reinforced concrete works.

Additionally, the sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the hybrid model is highly stable. Modifying the criterion weights did not produce significant changes in the ranking of construction errors, indicating that the model is robust to fluctuations in decision-maker preferences and can be reliably applied in engineering practice.

The hybrid fuzzy WINGS–fuzzy TOPSIS methodology can also be adapted for assessing risks in other construction processes that involve uncertainty and qualitative evaluations. While this study focuses specifically on reinforced concrete structures, the analytical framework itself remains generalizable and may support decision-making in related engineering contexts.

Overall, the results highlight the need for implementing systematic quality assessment methods in construction, particularly in reinforced concrete works, where execution errors may lead to substantial technical and economic losses. The developed hybrid model provides a practical decision support tool for planning, supervision, and quality management, while also indicating clear pathways for further methodological enhancement and empirical validation.