Abstract

In the current paper, we study breather propagation and arrest in chains with significantly nonlinear interactions of elements depending on the type of nonlinearity. We extend the consideration of the two-stage propagation of breathers in these chains on the relevant substrates to the general case of power-law nonlinear nearest-neighbor interaction. Our work concerns the effect of the nonlinearity on breather propagation and breather arrest. We exploit the simplified model to predict the main features of breather arrest for a wide range of nonlinearity types, including smooth-function analogs for vibro-impact contact.

1. Introduction

Energy transfer and localization in extended systems have attracted the interest of many researchers in recent decades [1,2,3,4]. The regimes of energy transfer and localization have an intimate connection with the problem of existence and the propagation of solitary waves and breathers in nonlinear lattices and chains [5,6]. The functioning of many systems and structures is deeply connected to the energy-targeted energy transfer in such systems and their wave features. The modern applications of this problem include the development of different devices, such as energy absorbers [7,8,9], actuators and sensors [10,11], and acoustic lenses and waveguides [12,13].

Despite the fact that many different types of nonlinear wave have been studied recently in many mechanical and acoustical systems, including solitons [14] and vector solitons [15], breathers are the most common type of nonlinear excitation observed in lattices of various types and natures [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. The propagation and features of breathers in nonlinear chains are the subject of many experimental [23,24,25] and theoretical [26,27,28] studies. Recent works include new insights into well-known systems [28,29,30,31] and the exploration of breathers in new systems, including nonlinear media and metamaterials [32,33]. A significant portion of these studies concern the effects of dissipation, which cannot be neglected in many real systems. One of these phenomena, referred to as breather arrest (BA), which demonstrates the interplay of two factors within the system, namely, the essential nonlinearity and damping, was recently considered in several works. Breather arrest has been reported in the mass-with-mass chain [34], in the chain with Hertzian nearest-neighbor coupling [35], and without local resonances. BA is defined as abrupt crossover from power-law decay to hyper-exponential amplitude decay [36] during propagation in discrete dissipative media.

In this study, we address breathers in a lattice on a linear substrate with significantly nonlinear nearest-neighbor interaction. This nonlinearity is represented as a force with different values of power in the energy-displacement law. In the limit of the infinite power value, the presented potential corresponds to the vibro-impact interaction [37,38]; the high values of power can serve as its smooth analogue. The nonlinearity of the softened vibro-impact type was also recently suggested to provide energy attenuation in the chain of the soft-walled billiards elements [39]. We consider the effect of significant nonlinearity on the breather propagation and breather arrest. We exploit the simplified model to predict the main features of the breather arrest in a wide range of nonlinearity power values, including smooth-function analogues for vibro-impact contact. The breathers for the chains with vibro-impact interactions were reported by O. Gendelman and others [40,41,42]. However, in these works, the onsite nonsmooth interaction was considered [43]. In our research, we consider breathers with nonlinear smooth analogue of the vibro-impact interparticle potential of interaction, which has not been addressed before.

In our research, we examine a breather’s propagation in an undamped as well as a damped oscillatory chain with nonlinear interparticle interaction. We consider the two-stage process of breather propagation, including amplitude decay and arrest. A power decrease in the breather amplitude is a characteristic of the first stage, while extremely tiny amplitudes with hyper-exponential attenuation are typical in the second stage. A simplified model of two linear oscillators with dissipation coupled by nonlinear contact forces is used to asymptotically explain the numerical results. The form of the breathers for different nonlinearity types is considered using the complexification-averaging method for the initial full system of equations.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, a mathematical model of the chain with nonlinear coupling is introduced. In Section 3, the numerical evidence of the breather propagation depending on the nonlinearity is considered. Section 4 is devoted to the asymptotic study of the reduced system, while Section 5 presents the analysis of the full model of the chain. These sections are followed by a discussion and concluding remarks.

2. Mathematical Model of the System

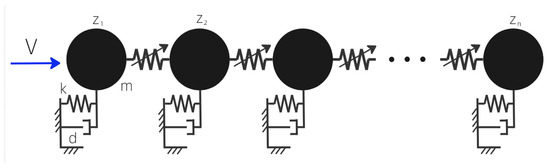

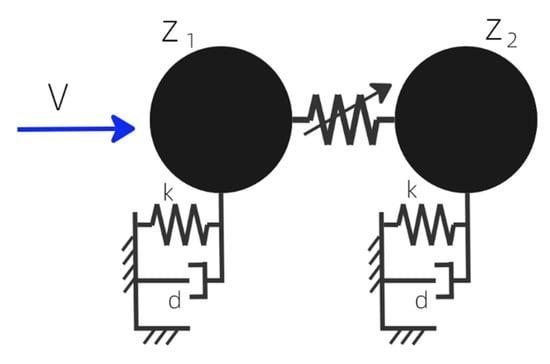

We consider a chain of N identical elements of mass m, connected by nonlinear springs and dampers with elastic stiffness and damping coefficients k and d, respectively; ) is the displacement of the nth oscillator (see Figure 1). It is assumed that the contact interaction between them is essentially nonlinear and can be described by the following force function:

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of the system.

The system is excited by an impact loading on the left edge of the chain, and the element obtains velocity V. Let us transform the system as follows:

where represents dimensionless time, is the displacement of the nth oscillator, is oscillator natural frequency, indicates the scale of the offset, and is a dimensionless dissipation coefficient.

The equations of motion of a system in dimensionless form are written as follows:

where the dot denotes differentiation with respect to τ. Dimensionless initial conditions for the system are written as follows:

where .

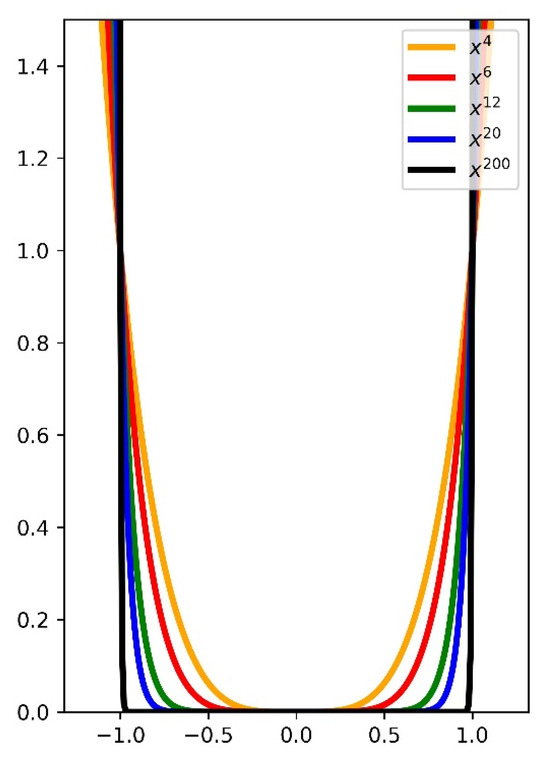

The view of the potential energy of the interparticle interaction form is presented in Figure 2. It is necessary to notice that the potential of the type with high values of power M can be used for modeling smooth analogues of vibro-impact potentials [38]. The limit of in the power-law interaction formally approaches the hard-wall potential of a vibro-impact system (see the case of M = 200 in Figure 2). This fact can be used to approximate the nonsmooth interaction of the vibro-impact type with the smooth function of the type considered in our work.

Figure 2.

Potential energy of the displacement for nonlinearities of different type of power-law.

3. Numerical Evidences

Nonlinear interactions between the nearest-neighbor oscillators and the presence of onsite elastic potentials inside the oscillatory chain suggest the presence of breathers [16,44,45]. At the first stage, we simulate the dynamics of system (3) under initial conditions (4); we perform numerical simulations for systems with nonlinearity power M = 3, 5, 11, and 19 using the Python 3.9.13 programming software. For the numerical solution, the iterative Runge–Kutta method of the built-in library scipy.integrate is used. The Matplotlib 3.5.2 and seaborn libraries are used to visualize the data.

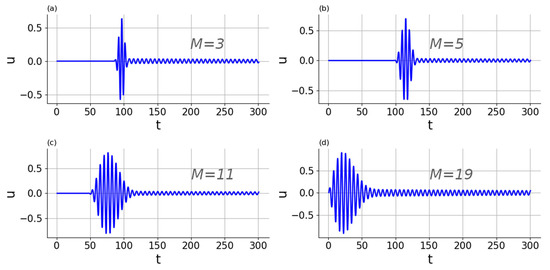

Let us start by presenting the profiles of the breathers; Figure 3 presents a typical response for the chain element for different power values of nonlinearity M, while Figure 4 shows the excitation profile along the chain after impulsive loading of its edge element. Figure 5 reports energy evolution while the process of propagation of breathers along the chain occurs. We study four chains consisting of N = 100 oscillators with the same parameters: initial excitation amplitude A = 0.97 and dissipation coefficient λ = 0.0035, but with different values of the power of the nearest-neighbor interaction force nonlinearity M = 3, 5, 11, and 19, respectively. Initially, the displacement amplitude is near to zero, then it reaches its greatest value, Amax, and then it starts to decline. The maximum breather amplitude is an order of magnitude smaller than the initial excitation value, indicating that the breather propagation is severely hindered. Similar findings about breather propagation in nonlinear chains were documented in previous works for linear oscillators with cubic nonlinearity [36] and for Hertzian-type interparticle interaction [35]. It is seen that part of the energy is irradiated into the oscillatory tail; however, consideration of its role is not the subject of the present study.

Figure 3.

Time response of the element n of the chain with the same parameters and initial conditions for different power values of nonlinearity: (a) ; n = 20; (b) ; n = 15; (c) ; n = 5; (d) ; n = 1. .

Figure 4.

Velocity profiles along the chain for different power of nonlinearity:

(a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) . Initial conditions and parameters are the same as in Figure 3.

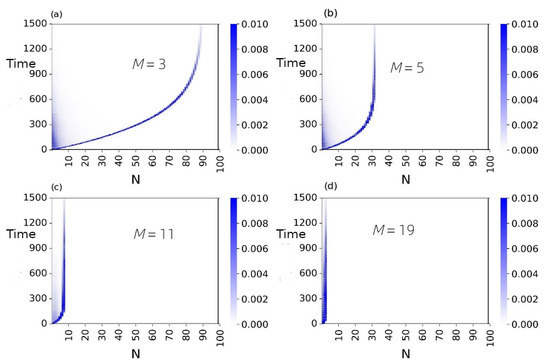

Figure 5.

Spatio-temporal diagram of energy distribution along the chain for different power of nonlinearity: (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) . Initial conditions and parameters are the same as in Figure 3.

Figure 5 shows the spatio-temporal diagrams of energy in the chain corresponding to the breather propagation for the described systems; the color on the diagrams indicates the energy level of each element at a given time. The diagrams show that the breather does not penetrate deep into the chain but stops. Moreover, the higher the power of nonlinearity, the faster the breather arrest appearance and the shallower the depth of penetration of the wave into the chain.

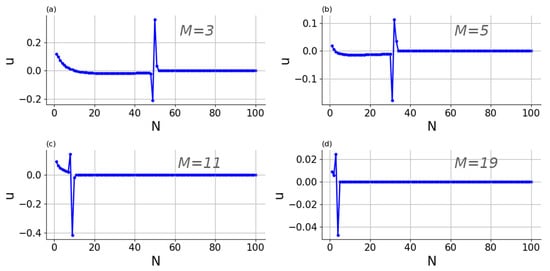

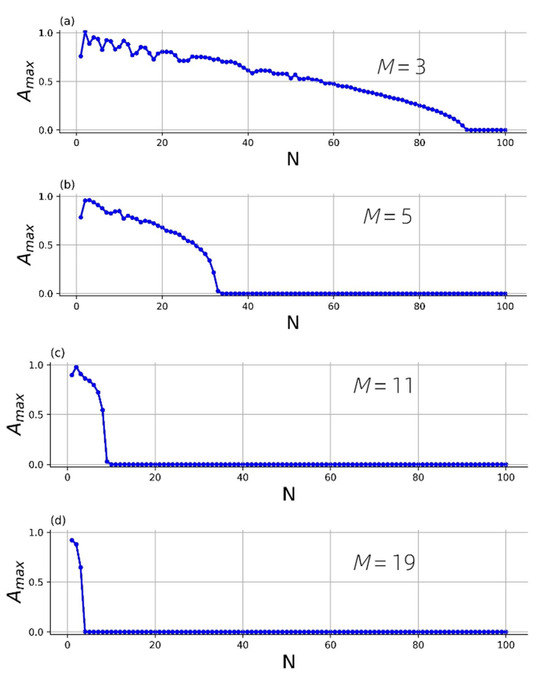

The traveling breather’s maximum amplitude Amax decays as it moves along the chain, as seen in Figure 6. At a particular penetration depth, the abrupt change from steady decay to nearly zero amplitude is readily visible. The breather arrest phenomenon is demonstrated in this simulation. Typically for any crossover effect, it is difficult to pinpoint the exact value of the arrest site. To provide some initial estimate criteria, we define the breather arrest as occurring when the maximum amplitude Amax drops below a specified threshold, which we designate as Aarrest = A/1000. We report from numerical simulations that breathers are only initiated when the initial excitation is relatively small; specifically, A should not be greater than unity. Furthermore, simulations indicate that the outcomes remain largely unchanged if the breather arrest threshold is modified by a factor of ten. Subsequently, we will explore a more precise method for numerically identifying the breather arrest, utilizing an asymptotic approximation for the amplitude decay of the breather.

Figure 6.

Maximal amplitude vs. number of the element along the chain for different power of nonlinearity: (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) . Initial conditions and parameters are the same as in Figure 3.

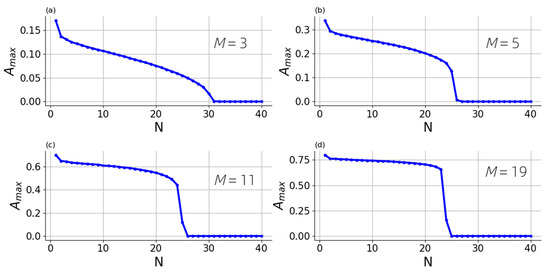

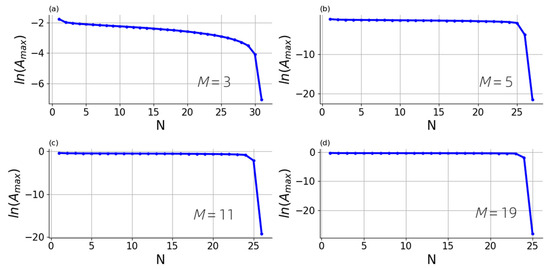

To illustrate the features of the breather evolution with different nonlinear potentials, we consider the propagation of breathers in a chain of 40 oscillators for different values of the power of nonlinearity M = 3, 5, 11, and 19, but under different conditions. We choose such initial amplitudes and dissipation parameter values so that the breather arrest appears at approximately the same penetration depth. The figures obtained (see Figure 7) show that the maximum amplitude of oscillators for higher powers of nonlinearity changes more sharply. Now let us represent the same figures on a logarithmic scale along the ordinate axis (see Figure 8). In the pictures, two main stages in the propagation of the breather are clearly visible; the first stage demonstrates power-law amplitude decrease, and the second corresponds to hyper-exponential decay. On a logarithmic scale, the first stage looks almost linear, and as the degree of nonlinearity of the system increases, the lines are closer to the abscissa axis, as damping occurs more sharply.

Figure 7.

Maximal amplitude of the oscillator on the number of element of the chain. Initial conditions and the dissipation are taken to reform similar length of the breather path for the chain of length : (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) .

Figure 8.

Maximal amplitude in logarithmic scale on the oscillator number for different values of nonlinearity power: (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) . Parameters and initial conditions are the same as in Figure 7.

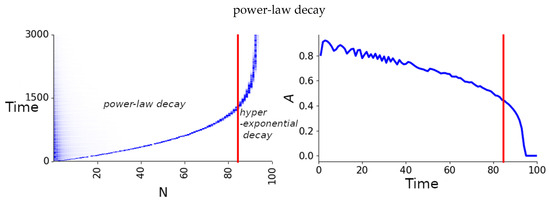

Let us illustrate a correspondence between the space–time diagram and the dependence of the maximal amplitude of the oscillator on its number, presented in Figure 9. The evolution to the left of the red line corresponds to power-law decay; the propagation of the breather energy on the space–time diagram is almost linear. The second stage is attenuation; it is depicted in the picture to the right of the red line, and then the breather is arrested.

Figure 9.

Correspondence of the spatio-temporal energy diagram to the figure of the dependence of maximum amplitudes on the number of the oscillator for .

4. Reduced System

In order to describe the phenomenon of breather arrest from a theoretical point of view and explain numerical results, we will consider a simplified model that simulates the propagation of a breather in a chain with a strongly nonlinear coupling. In a rough approximation, it can be assumed that the propagation of a breather can be understood as a sequence of energy transfers between particles. Moreover, due to the strong localization, it can be assumed that only two neighboring particles participate in each energy transfer act. Such simplification seems to be appropriate due to the extreme localization of the breather in the chain.

Such a reduction of the system was already used by M. Strozzi and O. Gendelman [25] in their study of the breathers in a granular chain with Hertzian interaction. They demonstrated that the chain of beads with Hertzian and cubic nonlinear asymmetric potentials of particle interactions may be effectively approximated using the sequence of interactions of consecutive pairs of particles. Because the breathers in the chain are highly localized, we also employ the same approximation. As a result, in a rough approximation, it is conceivable to assume that the breather propagation can be interpreted as a series of energy transfers between neighboring particle pairs while ignoring the impact of other particles on each of these transfers. Therefore, in a simpler model with only two oscillators, a back-and-forth energy transfer can be considered to characterize the breather propagation prior to the arrest.

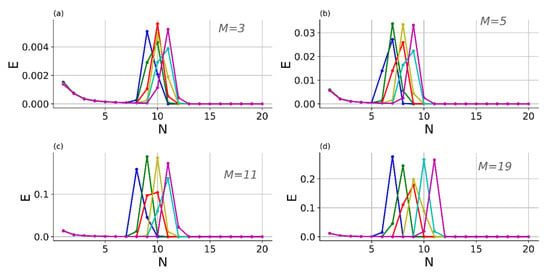

In Figure 10, we consider the energy profiles of the system for different values of the power of nonlinearity M = 3, 5, 11, and 19 for the set of parameters and initial conditions corresponding to Figure 8. It is evident that the most of the energy is localized on the three or two sites of the chain when the rest of the chain is barely excited. The localization is increased with the growth of the nonlinearity power M. We will approximately consider the process of the energy transfer along the chain like a process of the subsequent excitation of the unexcited element by the excited one, while the rest of the chain does not take part in the interaction.

Figure 10.

Energy profiles of the chain for consequent time moments for different nonlinearity power values M: (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) . Parameters and initial conditions are the same as in Figure 7.

The reduced system is presented in Figure 11. It consists of two particles of the same type as in the full model. The interaction between the two oscillators is essentially nonlinear. We study the effect of the nonlinearity power on the energy transfer from one particle to another.

Figure 11.

Scheme of the reduced system.

One of the particles is excited with an initial velocity V, and then the beats appear between the oscillators. Thus, each run-out is associated with the propagation of the breather on one particle. We will demonstrate that the number of such beats will be finite due to the strong nonlinearity of the coupling. The equations of motion for the simplified 2DOF model are written as follows:

Let us proceed to modal variables:

where is the center of mass of the system, and is the internal displacement of the system. In modal coordinates, the equations of motion and the initial conditions take the following form:

With initial conditions:

We consider the case of sufficiently weak damping to describe several interactions between the neighboring elements. The main steps of the analysis are analogous to those presented in [35] for the Hertzian type of interaction. However, for clarity of presentation, we reproduce them below. In the main approximation up to order O(λ), the solution for the center of mass R can be written as follows [35]:

To obtain an approximate solution for the internal movement of the system , we first perform a conversion to action-angle variables [46]:

The dependence between the energy of continuous motion and action is determined by the following well-known relation:

where E is the energy of continuous motion, and and , are the maximum and minimum values of displacement, respectively. The canonical transformation reduces the equation on to the form

Assuming a weak dissipation, we can perform averaging of the system (13) to obtain

The following equations can be solved:

Here, J0 is the initial value of the averaged action.

The linear stiffness is contained in the modal Equation (7) for despite the substantially nonlinear coupling. Furthermore, in system (7), where the frequencies of and are almost the same, we deal with the regime of relatively low-amplitude beatings when talking about breather arrest. Consequently, it implies that the quasilinear approximation allows for the treatment of internal displacement. The well-known action-angle transformation for linear oscillators is used to perform this [35,46]. We proceed using the following transformations:

From the expressions (14)–(16), setting the initial phase θ0 equal to 0, the following expression can be obtained for internal displacement in the simplified model:

To evaluate frequency, one needs to proceed with more accurate analysis. Assuming small amplitudes in Equation (11), it is possible to obtain the following ([24]; see also Appendix A):

Here, H.O.T. stands for terms of a higher order, . Equation (18) is general and is suitable for any nonlinear function, provided that the integral is not zero, and , which means the low-energy limit. If the integral in Equation (18) turns out to be zero, then these higher-order terms should be analyzed more carefully, as they provide the main effect. However, in the case of a power function, this is not the case:

By substituting (19) into (18) and performing the integration, we obtain the following expression:

where

The expression for the instantaneous frequency is obtained by simply differentiating the following expression (20):

where

By substituting and performing a simple integration, we obtain the following approximate expression for the dependence of internal displacement on time depending on the parameters of the system:

The expressions for the variables of the initial reduced model (u1, u2) can be easily obtained:

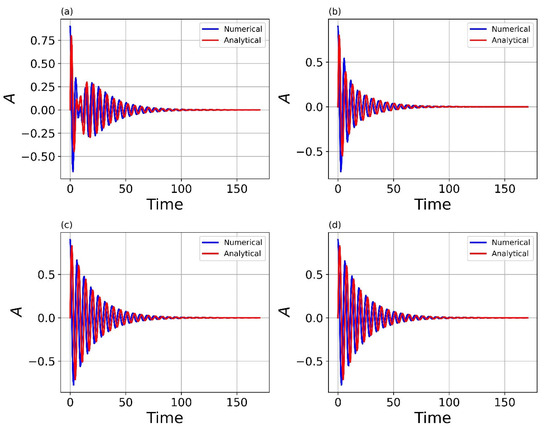

To check the applicability of the solution received, we compare the theoretical and numerical results for different potential types with nonlinearity power values M = 3, 5, 11, and 19. For this purpose, we present the approximate solutions for the mentioned cases (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Approximate solution for different values of power nonlinearity M = 3, 5, 11, 19.

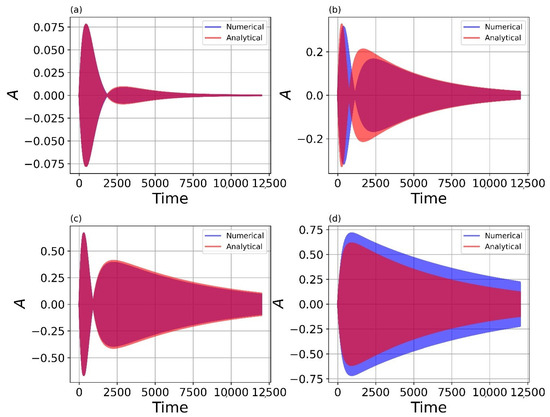

In Figure 12, we show the comparison of the numerical solution and the obtained approximate solution for a simplified system. It can be seen that the higher the power of nonlinearity, the more accurate the approximate analytical solution is compared to the numerical one. This is due to the fact that we solved the problem in the approximation of small amplitudes, and, as we found out earlier, the higher the degree of nonlinearity, the faster the initial amplitude decays. The higher the degree of nonlinearity, the lower the potential value for the amplitudes approaching unity (see Figure 2), so the approximate solution is more accurate.

Figure 12.

Comparison of analytical and numerical solutions u1 for different degrees of nonlinearity under the same conditions: : (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) .

The response of the 2DOF system has two characteristic timescales, the “fast” oscillations period and the “slow” evolution of the envelopes. The solution for (22) and (23) consists of two terms, the exponentially decaying term and a term with beatings, i.e., periodic energy exchanges between the two oscillators. The number of beatings is finite, as the beating term is also bounded by the exponentially decaying envelope.

The discrepancies between the numerical and analytical results are definitely visible. They can appear due to the roughness of the 2DOF approximation of the system, as the analysis ignores the excitation of the rest of the chain except the two elements in each moment of time. While the localization of the breather in the chain increases for higher powers of nonlinearity, the approximation better fits the numerical results of the full system for low amplitudes. However, to achieve the same penetration depth for different powers of nonlinearity, we have to take higher initial velocity amplitudes, as seen in Figure 8 and Figure 9. For the case, the higher amplitude leads to the higher discrepancies between the analytical solution and numerical one. The errors appear due to the low-amplitude limitations of approximation in our analysis.

It is now possible to discuss the optimal starting circumstances for the breather excitation. Based on Equations (21) and (22), the characteristic frequency of the beatings can be estimated as follows:

To obtain a well-formed breather, we have to assume beatings that can be featured as energy exchange in the timescale larger than the typical time of the oscillations. Therefore, the natural frequency ωn of the onsite potential should be significantly higher than the beating frequency ΩB. Consequently, it is possible to infer from (24) that breathers are only anticipated for moderate excitation amplitude values, i.e., if |A| ≤ 1. These results are consistent with the numerical simulation evidence.

The formation of the breather requires several beating cycles to appear. The number of them can be estimated from the final form of the analytical solution (23). The depth of penetration of the breather into the chain before arrest and dependence of the amplitude on the number of the element of the chain can be estimated [35] as follows:

In [35], the calculations were provided for the Hertzian type of interaction. However, a more general expression for nonlinear asymmetric potential was also presented. We note that (25) and (26) hold also for different values of nonlinearity power values M.

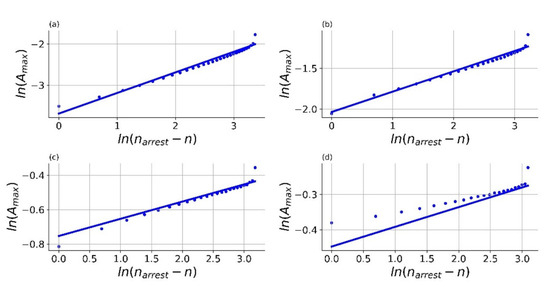

The comparison between the analytical estimation of the Amax(n) and the numerical results obtained for different values of nonlinearity M is presented in Figure 13 and Figure 14. The correspondence is very sufficient up to the nonlinearity values M = 11. However, for value M = 19 the estimation (26) does not work very well; this is due to the accuracy limitations for higher amplitudes discussed above.

Figure 13.

Comparison of analytical and numerical solutions u2 for different degrees of nonlinearity, : (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) . Initial conditions and parameters are the same as in Figure 7.

Figure 14.

Breather maximum amplitude Amax(n) vs. (n − narrest) in logarithmic scale. Comparison of analytical results for the reduced system (5) (solid line) and numerical solutions of the full system (3) for different degrees of nonlinearity, : (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) . Initial conditions and parameters are the same as in Figure 7.

5. Complete System Analytical Solution by Complexification-Averaging Method

There are several works devoted to the problem of the breathers’ propagation in different nonlinear chains. The evolution of the breathers in conservative chains was documented in previous works for linear oscillators with cubic nonlinearity [36] and for Hertzian-type interparticle interaction [35]. Unfortunately, the form of the solution for different nonlinearity types was not addressed in the studies mentioned. Below, we discuss the form of the breather solution while the damping is significantly weak and does not much affect the form of the breather.

We consider the equation of the system with nonlinear coupling:

In all numerical experiments, the attenuation coefficient is of the order of –, while the initial amplitude is about unity. Such small parameter values allow us to make a rescaling , k > 1. Such a consideration makes it possible to take into account the influence of dissipation in equations of higher orders of small parameter. The Appendix A has a more detailed description of this procedure.

To solve this problem, we will use the CX-A method, and we proceed to new complex variables:

where .

Let us express the initial variables in terms of new complex variables:

From which it immediately follows that

Let us substitute the systems into the initial equations and obtain

To separate the dynamics into slow and fast timescales, we introduce a small parameter . This small parameter allow the scaling of dependent variables based on their responses and derivatives. Therefore, we also define a fast timescale and a slow timescale .

We represent as a series with respect to powers of the parameter :

It is worth noting that the terms of even degrees of do not appear in the initial terms of the expansion due to the symmetry of nonlinearity. As we have defined a new set of timescales, the usual derivative τ will also be perturbed as follows:

By substituting Equations (28)–(31) into Equation (2) and assembling the terms in order of powers, we obtain the following zero-order equations (see Appendix A for more details):

The solution of equations of first order can be written in the following form:

where is slowly modulated amplitude, which is the envelope limiting the rapidly modulated oscillating term , oscillating with a fast frequency . To identify a term , we introduce into equations corresponding to the following order, and average the frequency terms quickly to keep our solution constrained. This step leads to the following equation for changing envelopes on a slow timescale:

where is defined in the Appendix A.

Let us write down the equations of slow flow in a simplified form using the relative response of neighboring generators :

For an infinite chain, the particle number n is rewritten as follows: n = 0, ±1, ±2, … Based on our observations in the previous section, we define an analog for traveling waves as follows:

where is a dimensionless amplitude of traveling waves, is slow frequency associated with modulation of a traveling wave of high frequency, and is a dimensionless wavenumber. By introducing Equation (18) into Equation (17) and performing some algebraic manipulations, we obtain

The approximate corrected nonlinear frequency of the system can be written as a combination of fast and slow frequencies:

Next, we obtain the equation for the function :

where T is a time shift between two breathers on adjacent oscillators. By substituting the obtained expression into the equation of slow flow in a simplified form, it is possible to obtain a system of equations for :

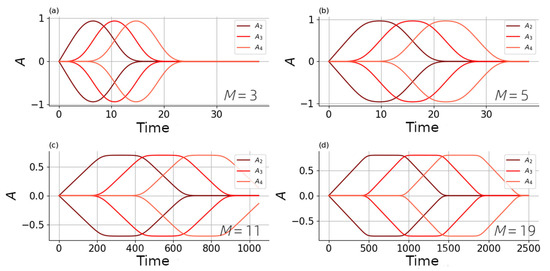

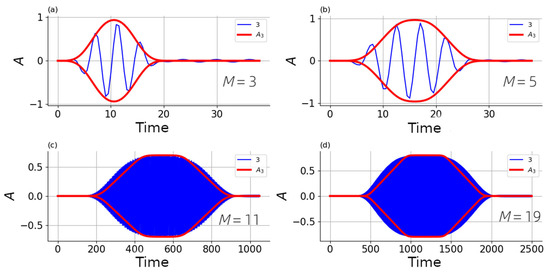

Let us compare the types of envelopes for different powers of nonlinearity (see Figure 15). For all considered cases, the envelopes have a similar character, we consider the time shift between breathers to be constant, and the results obtained correspond to the expected assumptions. At the same time, for higher powers, the resulting envelopes have a less smooth form.

Figure 15.

Envelopes for identical oscillators of systems with nonlinearities of different degrees under different conditions : (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) .

We can conclude that the main features of the envelope form can be captured by our reduced model (40) (see Figure 16). However, the numerically realized breather envelopes look smoother. We suggest that this is due to the terms of the higher order which are not captured by our model.

Figure 16.

Comparison of envelopes with numerical solutions for identical oscillators of systems with nonlinearities of different values of nonlinearity power (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) . Parameters and initial conditions are the same as in Figure 15.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

In this work, the propagation of the breathers, as well as their abrupt stopping and exponential decay, in discrete models with a significantly nonlinear interaction of elements depending on the type of nonlinearity was investigated. Numerical simulation of an oscillator chain on a substrate with friction and essentially nonlinear interaction of neighboring elements was carried out. An idea of the stages of propagation and arrest of breathers for a wide range of nonlinearity power values was discussed. An asymptotic model was constructed for the initial stage of breather propagation, while the damping is insignificant, and for the final stage, when it is significantly attenuated and stopped. The analytical predictions obtained using the reduced models are in good agreement with the numerical results of the propagation of breathers in the original model in a wide range of nonlinearity power values, including smooth analogues of vibro-impact interaction. Using a complexification-averaging technique, we also address the dependence of the form of the breather envelope from the nonlinearity power.

In our work, we give explicit form for the amplitude decay and penetration depth of the breathers for different powers of nonlinearity of the intersite coupling. Such a universal and simple approach give the possibility to predict the wave properties of different discrete media and devices based on the nonlinear interacting elements. We extend the study of the breathers’ propagation after impulsive load of the side element to the general case of significant nonlinearity of the nearest-neighbor interaction. This study can be useful for development of the waveguides, energy absorbers, signal transformers, etc. The connected energy transfer can be quite significant in different devices and nonlinear media, including metamaterials.

The discrepancies between the numerical results from the initial full model and analytical results obtained with the help of the reduced system were discussed. The limitations of our approach lie in the low-amplitude approximation. However, it gives very reasonable results even for moderate initial loadings and high powers of nonlinearity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.; methodology, M.K., software, M.K. and S.P.; validation, S.P. and M.K.; formal analysis, S.P.; investigation, S.P. and M.K.; resources, M.K.; data curation, S.P. and M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K.; visualization, S.P. and M.K.; supervision, M.K.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Russian Science Foundation (project no. 24-23-00435).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Consider the equation:

Let us convert the parenthesis:

Let us find out at which k the resonant term is:

Substitute it back and obtain a resonant term of the form:

References

- Vakakis, A.F.; Gendelman, O.V.; Bergman, L.A.; Mojahed, A.; Gzal, M. Nonlinear targeted energy transfer: State of the art and new perspectives. Nonlinear Dyn. 2022, 108, 711–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakakis, A.F.; Gendelman, O.V.; Bergman, L.A.; McFarland, D.M.; Kerschen, G.; Lee, Y.S. Nonlinear Targeted Energy Transfer in Mechanical and Structural Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Seguy, S.; Berlioz, A. On the dynamics around targeted energy transfer for vibro-impact nonlinear energy sink. Nonlinear Dyn. 2017, 87, 1453–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraio, C.; Nesterenko, V.F.; Herbold, E.B.; Jin, S. Energy trapping and shock disintegration in a composite granular medium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 058002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, S.; Kopidakis, G.; Morgante, A.M.; Tsironis, G.P. Analytic conditions for targeted energy transfer between nonlinear oscillators or discrete breathers. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2001, 296, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopidakis, G.; Aubry, S.; Tsironis, G.P. Targeted Energy Transfer through Discrete Breathers in Nonlinear Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 87, 165501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilipchuk, V. Stochastic energy absorbers based on analogies with soft-wall billiards. Nonlinear Dyn. 2019, 98, 2671–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Wierschem, N.E.; Fahnestock, L.A.; Bergman, L.A.; Spencer, B.F., Jr.; AL-Shudeifat, M.A.; McFarland, D.M.; Quinn, D.D.; Vakakis, A.F. Realization of a strongly nonlinear vibration-mitigation device using elastomeric bumpers. J. Eng. Mech. 2013, 140, 04014009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendelman, O.V. Analytic treatment of a system with a vibro-impact nonlinear energy sink. J. Sound Vib. 2012, 331, 4599–4608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, P.; Ni, X.; Nassiri, S.; Vandenbossche, J.M. A solitary Wave-based Sensor to Monitor the Setting of Fresh Concrete. Sensors 2014, 17, 12568–12584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinberg, S.I.; Vakakis, A.F.; Gendelman, O.V. Acoustic diode: Wave non-reciprocity in nonlinearly coupled waveguides. Wave Motion 2018, 83, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadoni, A.; Daraio, C. Generation and control of sound bullets with a nonlinear acoustic lens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 7230–7234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepidi, M.; Bacigalupo, A. Nonlinear Dispersion Properties of Acoustic Waveguides with Cubic Local Resonators. In Developments and Novel Approaches in Biomechanics and Metamaterials; Abali, B., Giorgio, I., Eds.; Advanced Structured Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Romero-García, V.; Theocharis, G.; Richoux, O.; Achilleos, V.; Frantzeskakis, D.J. Bright and gap solitons in membrane-type acoustic metamaterials. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 96, 022214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Raney, J.R.; Bertoldi, K.; Tournat, V. Nonlinear waves in flexible mechanical metamaterials. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 130, 040901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.; Kevrekidis, P.G.; Cuevas, J. Breathers in oscillator chains with Hertzian interactions. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2013, 251, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevrekidis, P.G. Non-linear waves in lattices: Past, present, future. IMA J. Appl. Math. 2011, 76, 389–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, S. Discrete Breathers: Localization and transfer of energy in discrete hamiltonian nonlinear systems. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2006, 216, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikot, I.K.; Rayzan, N.B.; Kovaleva, M.; Starosvetsky, Y. Discrete breathers and discrete oscillating kink solution in the mass-in-mass chain in the state of acoustic vacuum. Comm. Nonl. Sci. Num. Simul. 2022, 107, 106020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstrand, A.; Li, H.; Weinstein, M.I. Discrete Breathers of Nonlinear Dimer Lattices: Bridging the Anti-continuous and Continuous Limits. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2023, 33, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstrand, A. Families of discrete breathers on a nonlinear kagome lattice. Phys. Rev. E 2025, 111, 064212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, C.; Pelinovsky, D.E.; Schneider, G. On the Existence of Generalized Breathers and Transition Fronts in Time-Periodic Nonlinear Lattices. SIAM J. Appl. Dyn. Syst. 2025, 24, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.A.; Cho, S.; Remick, K.; Vakakis, A.F.; McFarland, D.M.; Kriven, W.M. Experimental study of nonlinear acoustic bands and propagating breathers in ordered granular media embedded in matrix Granul. Matter 2015, 17, 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, H.; Cuevas-Maraver, J.; Kevrekidis, P.G.; Vainchtein, A. Discrete breathers in a mechanical metamaterial. Phys. Rev. E 2023, 107, 014220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, G. Travelling breathers and solitary waves in strongly nonlinear lattices. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2018, 376, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, S.; Hong, J.; Bang, J.; Avalos, E.; Doney, R. Solitary waves in the granular chain. Phys. Rep. 2008, 462, 21–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, F.; Bulchandani, V.B.; Benalcazar, W.A. Nonlinear breathers with crystalline symmetries. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 111, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbinin, S.A.; Kazakov, A.M.; Bebikhov, Y.V.; Kudreyko, A.A.; Dmitriev, S.V. Delocalized nonlinear vibrational modes and discrete breathers in β -FPUT simple cubic lattice. Phys. Rev. E 2024, 109, 014215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Maraver, J.; Farrellx, P.E.; Villatoro, F.R.; Kevrekidis, P.G. Discrete breathers in Klein–Gordon lattices: A deflation-based approach featured. Chaos 2023, 33, 113126. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, H.; Cuevas-Maraver, J.; Kevrekidis, P.G.; Vainchtein, A. Moving discrete breathers in a β-FPU lattice revisited. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2022, 111, 106435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Orly, I.; Givli, S.; Starosvetsky, Y. Intrinsically localized modes of bilinear FPU chains: Analytical study. J. Sound Vib. 2024, 591, 118493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattis, J.A.D.; Alzaidi, A.S.M. Asymptotic analysis of breather modes in a two-dimensional mechanical lattice. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2020, 401, 132207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Lacarbonara, W.; Cheng, L. Advances in nonlinear acoustic/elastic metamaterials and metastructures. Nonlinear Dyn. 2022, 113, 23787–23814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, M.A.; Barry, O.R.; Vakakis, A.F. Breather propagation and arrest in a strongly nonlinear locally resonant lattice. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 183, 109623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strozzi, M.; Gendelman, O.V. Breather arrest in a chain of damped oscillators with Hertzian contact. Wave Motion 2021, 106, 102779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J. Universal power-law decay of impulse energy in granular protectors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 108001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manevitch, L.I.; Gendelman, O.V. Oscillatory models of vibro-impact type for essentially non-linear systems. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2008, 222, 2007–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendelman, O.V. Modeling of inelastic impacts with the help of smooth-functions. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2006, 28, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilipchuk, V. Cellular metastructures for elastic wave attenuation using chaotic soft-walled billiard effects. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 23839–23861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perchikov, N.; Gendelman, O.V. Dynamics and stability of a discrete breather in a harmonically excited chain with vibro-impact on-site potential. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2016, 292–293, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinberg, I.; Gendelman, O.V. Localization in finite vibroimpact chains: Discrete breathers and multibreathers. Phys. Rev. E 2016, 94, 032204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinberg, I.; Gendelman, O.V. Localization in Finite Asymmetric Vibro-Impact Chains. SIAM J. Appl. Dyn. Syst. 2018, 17, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempelman, J.R.; Vakakis, A.F.; Matlack, K.H. Spectral energy scattering and targeted energy transfer in phononic lattices with local vibroimpact nonlinearities. Phys. Rev. E 2023, 108, 044214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Fang, C.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Fu, W.; Flach, S.; Huang, L. Impact of on-site potentials on q breathers in nonlinear chains. Phys. Rev. E 2025, 112, 044202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojahed, A.; Vakakis, A.F. Certain aspects of the acoustics of a strongly nonlinear discrete lattice. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020, 99, 643–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Mechanics, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1976. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).