Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and osteoarthritis (OA) are significant global health challenges, fueling the need for innovative therapeutic strategies. Natural polyphenolic compounds, such as green tea catechins, exhibit promising anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties, making them potential adjuncts to rheumatic disease therapy. This review examines the effects of catechins, particularly epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), on key pathophysiological processes associated with RA and OA, such as pro-inflammatory cytokine production, oxidative stress, cartilage degradation, angiogenesis, and immune cell activation and proliferation. This study contains experimental data contained in full-text articles published in open-access indexed journals published only in English. The most important conclusions drawn from the in vitro and in vivo studies available so far, as well as studies on patients, show that green tea catechins modulate pro-inflammatory pathways, reduce the level of pro-inflammatory cytokines and improve the condition of the intercellular matrix in joint tissues, limiting the destruction of joint tissues in animals and patients and reducing pain. Although these studies suggest potential benefits, such as reduced inflammation and improved clinical parameters, the number and scale of studies are insufficient to confirm the clinical efficacy in a broad patient population. Therefore, claims of adjunctive therapy to conventional therapies should be interpreted with caution, and further well-designed and more powerful clinical trials are needed to verify the translation of the promising molecular mechanisms of green tea catechins into clinical practice.

1. Introduction

Musculoskeletal disorders constitute a leading cause of disability worldwide [1]. RA is a chronic autoimmune disease associated with synovial membrane inflammation that often leads to tissue damage and joint deformity, accompanied by swelling, pain, and joint stiffness, and can further impair mobility. Approximately 0.2% of the global population, or over 17.6 million people, suffer from RA [1,2]. According to Global Burden of Diseases Study in 2019, 18 million people worldwide were living with RA and about 70% of people living with RA are women, and 55% are older than 55 years [3]. OA is a chronic condition characterized by progressive deformation of joint cartilage, leading to damage to the subchondral bone and synovial membrane and ultimately impairing mobility. It affects more than 600 million people worldwide, representing over 7% of the global population, and substantially reduces quality of life by limiting daily and social functioning [3].

OA can be treated with non-pharmacological methods (including education, physiotherapy, and weight loss), pharmacological methods (primarily non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), intra-articular injections, and surgical treatment in advanced cases. The most common symptoms of OA and RA are swelling, pain and joint deformities, which are particularly bothersome in everyday life if they affect the joints of the hand and wrist or the knee and hip joints, impairing everyday activities, including movement [2,4]. Treatments are often combined and tailored to the patient’s needs; however, many comorbidities limit the use of pharmacotherapy, necessitating the use of simple painkillers or exclusive physiotherapy [5,6].

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), including biological therapies and molecules that target specific inflammatory pathways, are primarily used to treat RA. Despite their availability, not all patients achieve full disease control, and some therapies carry the risk of adverse effects in the form of nausea, diarrhea, hair loss, abdominal pain and fatigue, which limit the use of these methods in some patients. Therefore, in case of both diseases, there are limitations in the treatment of patients with traditional methods using glucocorticosteroids and biological treatment [5,6].

Given the limitations of current therapies, there is growing interest in natural bioactive compounds with anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective potential. Green tea (Camellia sinensis) has become an area of interest, demonstrating numerous health benefits, primarily due to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, of which EGCG is the most studied compound [7]. Research into the potential health benefits of food components is expanding rapidly, and green tea catechins represent a promising group of compounds that may modulate the key mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of OA and RA.

This article summarizes the available data on their effects in in vitro models, animal studies, and clinical trials, with particular emphasis on their effects on inflammatory processes, oxidative stress, and the potential to slow down disease progression and alleviate symptoms. The literature review was performed by searching databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, for terms: osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, green tea, EGCG, catechins. This study contains only experimental data contained in full-text articles published in open-access indexed journals published only in English. Conference proceedings, data contained in master’s and doctoral theses, and works published in national languages other than English were excluded.

2. Mechanisms of Action of Green Tea Catechins

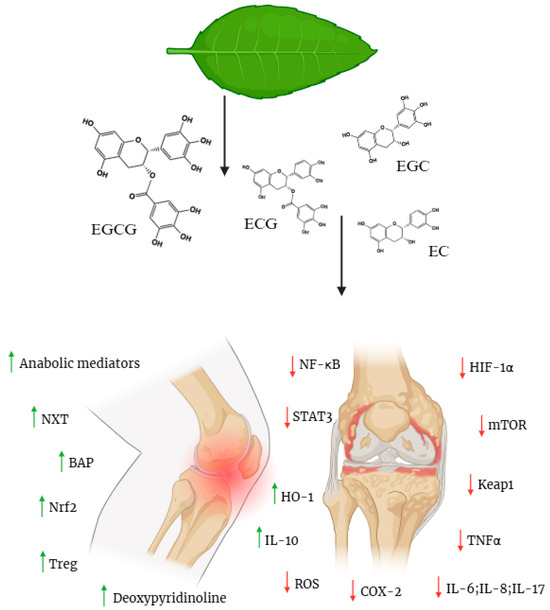

Camellia sinensis contains bioactive polyphenols known as catechins, primarily epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), epigallocatechin (EGC), epicatechin gallate (ECG), and epicatechin (EC) [8] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structural formulas of green tea catechins. Catechins Multi-Target Effects in RA/OA: Protective (Green ↑) Vs. Inhibitory (Red ↓) Pathways. Green tea leaf → source of catechins (EGCG, EGC, ECG, EC); Green arrows (↑): Activation of protective mechanisms; Red arrows (↓): Inhibition of inflammatory/degradative processes; Knee joint arthritis: Target model of therapeutic action. Created in BioRender. Bochniak, O. (2025) https://BioRender.com/5hsfuev.

These compounds vary in their chemical structures and biological effects, contributing synergistically to broader protective benefits. Structurally, catechins have di- or tri-hydroxy substitutions in ring B (the catechol system in EC/ECG and pyrogallol system in EGC/EGCG) and meta-5,7-dihydroxyl groups in ring A. An additional galloyl residue at carbon C-3, characteristic of EGCG and ECG, enhances interactions with antioxidant potential [9,10]. In cell and animal models, catechins modify several axes that are key for cartilage and muscles [11] (Figure 1).

2.1. Anti-Inflammatory Action

In the pathogenesis of OA, inflammation is often triggered by interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), which activate NF-κB and MAPK (including p38 and JNK) signaling pathways, leading to the upregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase (COX-2). In IL-1β-stimulated human chondrocytes, catechins, particularly EGCG, suppress iNOS and COX-2 expression, reducing nitric oxide (NO) and PGE2 (prostaglandin E2) production while inhibiting nuclear translocation of the p65 NF-κB subunit [12]. Proteomic studies have revealed that EGCG broadly inhibits the IL-1β-induced inflammatory response, including IL-6, IL-8, chemokines, and proteases, Via NF-κB- and JNK-dependent mechanisms [13]. Additionally, under metabolic stress, advanced glycation end products (AGEs) activate the RAGE receptor, promoting chondrocyte catabolism and apoptosis. EGCG mitigates this by suppressing TNF-α and MMP-13 (a collagenase that breaks down type II collagen) expression through the inhibition of p38 and JNK, linking metabolic stress to cartilage degradation [14].

In rheumatoid synovial cells, EGCG and EGC inhibit the response to IL-1β (decrease in IL-6/IL-8, COX-2, and MMP-2) more strongly than EC, mediated by TAK1 (TGF-β-activated kinase 1) [9]. In the autoimmune arthritis model, catechins with a dominant role of EGCG shift the Treg/Th17 balance (↓ IL-17, ↑ IL-10) by suppressing STAT3/HIF-1α (HIF-1α: hypoxia-inducible factor) and coupled inhibition of the mTOR pathway, which translates into a weaker inflammatory drive in the joint [15]. Excess IL-17 [16] and active STAT3 are associated with the perpetuation of inflammation, which is why their balance and reduction in Th17 excess are important. Reviews of their mechanisms of action have concluded that in various inflammatory contexts, catechins weaken the Th17 program while supporting Treg/IL-10, consistent with STAT3 axis inhibition [17] (Figure 1).

2.2. Antioxidant Activity

Inflammation causes an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), which damage proteins, lipids, DNA and activate NF-κB. Catechins act in two ways: not only do they “scavenge” reactive species, but they also activate Keap1–Nrf2–ARE (Keap1—a protein that “holds” Nrf2; ARE—antioxidant response sequences), inducing, among others, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and NQO1 (NAD(P)H: quinone reductase 1). In human chondrocytes, EGCG, through Nrf2 activation, alleviates oxidative damage, apoptosis, and cellular aging features, and the pharmacological inhibitor of Nrf2 [11] abolishes this effect, confirming the specificity of the pathway [18]. In practice, this means more stable mitochondrial metabolism and a lower secondary inflammatory drive. The redox mechanism interacts with the anti-inflammatory effect and explains the observed chondroprotection in post-traumatic models [11]. In a randomized crossover study in sprinters, four weeks of GTE (a mixture of catechins) supplementation increased total antioxidant capacity (TAC) and reduced post-exercise malondialdehyde (MDA) levels (a marker of lipid peroxidation) [19]. In another study on overweight men, short-term GTE reduced exercise-induced DNA damage (8-OhdG-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine) with mixed effects on G [20]. The direction of biomarker changes is consistent with Nrf2 activation and the overall antioxidant potential of the catechins (Figure 1).

2.3. Regulation of Cartilage Degradation Processes

Preserving the cartilage matrix is a critical therapeutic goal in patients with OA. Studies on human and bovine cartilage explants have demonstrated that EGC, ECG, and EGCG, especially gallic acid catechins, effectively inhibit the degradation of proteoglycans and type II collagen at micromolar concentrations without cytotoxicity, indicating the chondroprotective nature of this class of compounds, not just EGCG [21,22]. Accordingly, in a mouse model of post-traumatic OA, green tea polyphenol administration attenuated cartilage matrix loss, downregulated inflammatory markers, and reduced pain-related behaviors [23]. Similarly, in a rat model, intra-articular injections of EGCG improved cartilage histology and joint function [24]. Matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13) is the primary enzyme responsible for type II collagen degradation in OA, with MMP-1 and MMP-2 also contributing to cartilage breakdown. EGCG and, to a lesser extent, EGC, reduce MMP-13/MMP-1 expression stimulated by interleukin-1β (IL-1β) or advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) via the p38/JNK signaling pathway [14]. In RA synoviocytes, catechins differentially suppress MMP-2 and inflammatory mediators (EGCG/EGC > EC) [4]. A common effect is the slowing of matrix degradation observed In Vivo [20,21,22] (Figure 1).

2.4. Regulation of Autophagy and Apoptosis in Joint Cells

Autophagy is a natural protective mechanism of the cartilage that weakens with age. It supports cartilage homeostasis, and its age-related decline is associated with apoptosis and OA progression [25]. In the anterior cruciate ligament transection (ACLT) rat model, intra-articular dosing of EGCG increases autophagy markers, including microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3), autophagy-related protein beclin-1, and ubiquitin-binding protein p62, while inhibiting the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) and reducing chondrocyte apoptosis, which correlates with a better histological picture [24]. Pharmacological reviews have highlighted that various phytochemicals, including catechins, converge on the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-mTOR axis to restore a beneficial autophagic balance [26]. As previously noted, catechins modulate stress and inflammatory responses by activating Nrf2 through interaction with Keap1 and inhibiting pro-inflammatory and metabolic pathways (STAT3/HIF-1α, mTOR), which shifts the signaling network towards equilibrium: less inflammatory transcription, lower apoptosis, and better matrix maintenance [15,17,18,24,25]. At the molecular level, this translates into increased expression of cytoprotective genes (HO-1, NQO1; Keap1–Nrf2–ARE pathway) and activation of the autophagy program (↑ LC3/MAP1LC3, ↑ BECN1, ↑ p62) with simultaneous suppression of mTOR. The balance of survival shifts towards anti-apoptotic (changes in the BCL-2/BAX axis) [18,24,27]. From the perspective of the “class of compounds” the effect is complementary: EGCG/ECG dominate in STAT3/mTOR inhibition and anti-catabolic effects, and EGC clearly supports Nrf2/redox; in GTP/GTE mixtures, the effects are functionally additive [9,11,22]. These complementary mechanisms highlight the potential of catechins as multi-targeted agents in OA; however, clinical trials are needed to validate their efficacy (Figure 1).

3. Animal Models

In recent years, scientists worldwide have increasingly focused on preclinical studies conducted using animal models. These studies play a crucial role in assessing the therapeutic potential of natural compounds. Furthermore, animal studies enable a detailed understanding of the mechanisms of action of bioactive substances, allowing assessment of their efficacy and safety before clinical trials in humans. Animal models are widely used to analyze the effects of catechins contained in green tea on inflammatory processes, oxidative stress, joint cartilage degeneration, and the immune response. The results of these studies provide valuable data confirming the potential of these compounds to alleviate symptoms and slow the progression of diseases, such as OA and RA. A summary of studies on green tea catechins in animal models is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Studies involving green tea catechin in animal models of OA and RA.

3.1. Osteoarthritis

Studies conducted so far have shown that EGCG and polyphenols found in green tea can effectively alleviate inflammation, limit joint cartilage degradation, and improve functionality in various animal models of OA.

A study by Huang et al. using a Sprague-Dawley rat model with induced ACLT injury demonstrated that intra-articular administration of EGCG significantly limited the development of posttraumatic OA. Furthermore, overall function improved, and joint cartilage damage was reduced. This is due to the anti-inflammatory effects of EGCG on cartilage and synovial tissues. This compound inhibited the generation of COX-2 and MMP-13 levels. Furthermore, EGCG reduces mTOR expression while increasing Beclin1, LC3, levels, which may contribute to the stimulation of autophagy [24]. In a rabbit model of OA injected intraarticularly with green tea extract, Susmiarsih et al. observed a reduction in knee joint degradation along with a decrease in NO levels [28]. Huang et al., in a study using an intra-articular model of aging-related OA based on Dunkin-Hartley guinea pigs, demonstrated that EGCG administration positively affected joint cartilage health by limiting proteoglycan loss and joint surface destruction. Furthermore, EGCG reduced the apoptosis rate. EGCG treatment was associated with an increase in type II collagen protein [29] and a decrease in MMP-13 and p16 Ink4a. This was further confirmed by in vitro studies [29]. Leong et al. used a C57BL/6 mouse model that underwent surgical destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) or sham surgery. EGCG treatment reduced the loss of Safranin O and cartilage erosion. Furthermore, the levels of IL-1β, TNFα, and MMP-1, -3, -8, and -13 were reduced in the articular cartilage of the mice. However, increased expression of the MMP regulator Cbp/p300 Interacting Transactivator 2 (CITED2) was observed. The mice demonstrated improved mobility, that is, distance traveled, which may indicate reduced pain sensation associated with OA [23].

3.2. Rheumatoid Arthritis

Several animal model studies have investigated the beneficial effects of catechins in RA. Yang et al. used BALB/c mice in a knockout model of autoimmune arthritis with the IL-1 receptor antagonist RaKO. Osteoclast markers were reduced both In Vivo and in vitro. In tests performed on mouse spleens, they found an increase in the number of Foxp3 Treg cells, whereas the percentage of Th17 cells decreased. Furthermore, in vitro, EGCG administration reduced the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and proteins associated with oxidative stress. Furthermore, a decrease in p-STAT-3, mTOR, and HIF-1α, a metabolic checkpoint for Th17/Treg differentiation, was observed, supporting the therapeutic potential of EGCG in RA [15]. Kim et al. evaluated the protective potential of polyphenolic compounds isolated from green tea [30] in rats against RA and their impact on specific immune mechanisms. Rats treated with green tea polyphenols (GTP) demonstrated reduced arthritis severity compared to the control group. Furthermore, GTP administration reduced the concentration of pro-inflammatory IL-17 and increased the concentration of anti-inflammatory IL-10 [30]. Haqii et al., using an experimental model of collagen-induced inflammation (CIA) in mice, demonstrated that administration of GTP reduced the index of joint inflammation. Western blot analysis revealed a reduction in the expression of inflammatory mediators, such as COX-2, IFNγ, and TNFα, within the joint. Furthermore, histological and immunohistochemical studies confirmed these observations. There was a decrease in IgG concentration in the serum of animals treated with GTP [31].

Although animal studies provide valuable preclinical data, they have significant limitations. In some of the analyzed experiments, statistical power calculations were not performed, and the animal group sizes were small, limiting the strength and generalizability of the results. Furthermore, the bioavailability of EGCG poses a challenge to its interpretation. Although doses up to 800 mg daily for 4 weeks are well tolerated in humans, the compound is extensively metabolized in the small intestine, which reduces its effective concentration after oral administration [23]. These factors should be considered when assessing the reliability and translatability of the results in clinical settings.

4. In Vitro Studies

In vitro studies are key to developing new drugs and therapies. They enable efficacy and safety testing of the proposed method. A major advantage of in vitro studies is the ability to precisely control the experimental conditions and limit the need for animal experiments. This approach allows for faster initial results and significantly reduces the research costs. To confirm the obtained results, In Vivo and clinical trials are necessary, as laboratory results do not always directly translate into effects in the entire body.

A study conducted by Adcocks et al. on nasal and metacarpophalangeal cartilage in cattle, as well as on human OA and rheumatoid cartilage, showed that catechins had a positive effect on the studied structures. Initially, the tissues were cultured in the presence or absence of factors associated with accelerated cartilage matrix degradation. Specific catechins and type II collagen were introduced into individual cultures. In bovine cartilage, EGCG (20 μmol/L) effectively reduced proteoglycan degradation induced by rnTNF. No significant changes were observed after stimulation with rhIL-1α and all-trans retinoic acid. Slightly different effects were observed with ECG and EV (20 μmol/L), as they significantly reduced IL-1α-induced proteoglycan degradation but did not limit the destruction induced by rhTNF and all-trans retinoic acid. In human cartilage from both OA and RA, ECG (20 μmol/L) positively influenced the inhibition of proteoglycan degradation and the release of proteoglycans in cells exposed to IL-1β and TNF. Similar results have been observed for EGCG [22].

Akhtar et al., using cultured human chondrocytes with OA, demonstrated that EGCG activity at 50 and 100 μM concentrations primarily focused on inhibiting the activation of NF-κB transcription factors, including c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) from the MAPK family (Table 2). Furthermore, it inhibits IL-1β-induced granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor production by chondrocytes. It also affects IL-6, IL-8, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), MCP-3, macrophage inflammatory protein-1β (MIP-1β), granulocyte chemotactic protein-2 (GCP-2), MIP-3α, and interferon-γ-inducible protein-10 (IP-10) [13].

Table 2.

In vitro studies with green tea catechin in OA and RA.

Fechtner et al. used primary human rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts (RASF) to examine the modulation of various signaling pathways by EGCG, EGC, and EC at various concentrations (5–20 µM). EGCG and EGC effectively reduced the release of IL-6, IL-8, and MMP-2. In the case of COX-2 expression, these catechins selectively inhibited the expression of COX-2, whereas EC did not exhibit any inhibitory properties. Molecular docking analysis confirmed that EGCG occupies the largest binding site in the TAK1 kinase domain, exhibiting the greatest inhibitory effect. Furthermore, EGCG can inhibit the expression of p38 kinase and the transcription factor NF-κB in the cell nucleus, whereas EC and EGC showed no significant effects in this regard [9].

In summary, the in vitro studies discussed demonstrate a relatively consistent effect of catechins, especially EGCG and ECG, primarily on inhibiting catabolic processes in cartilage and synovial tissue. This is achieved through the modulation of inflammatory mediators and key signaling pathways, such as NF-κB, JNK, and TAK1. Although the modes of action of these compounds are generally similar (reduction in matrix degradation, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and metalloproteinases), differences are observed between individual catechins. For example, EGCG has greater efficacy against TNF-induced degradation, and ECG is selective in human cartilage models, demonstrating that these effects depend on both the type of compound and inflammatory stimulus. The main limiting factor is the still very small number of published experiments. These studies primarily concern chondrocytes, with only one study based on synoviocytes. The EGCG doses used also varied from 5 to as much as 100 µM, making drawing common conclusions difficult. Furthermore, none of the authors compared the doses used in in vitro studies to the doses used in laboratory animals or in human studies. The use of simple monolayer models or isolated tissues remains also a significant limitation. Studies using more complex physiological models, such as chondrocyte and synoviocyte co-cultures or three-dimensional models, are lacking. These gaps hinder the full transfer of results to In Vivo conditions and indicate the need to develop more advanced research platforms that allow for a better assessment of the translational potential of catechins.

5. Clinical Trials

Inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and reduced autophagy are the main adverse processes occurring in chondrocytes in individuals with OA and RA. These impair their function and promote catabolic processes associated with aging and chondrocyte death [32]. Due to the high morbidity of older adults associated with pain and various dysfunctions, interventions that modify these signaling axes may have clinical significance. Therefore, research is crucial, as proper treatment of inflammation in OA and RA is essential for restoring chondrocyte function and integrity, alleviating pain, improving quality of life, and controlling the progression of both diseases. Green tea catechins (especially EGCG) may affect the health of patients and their joints by reducing the expression of inflammatory signaling mediators, thereby demonstrating anti-inflammatory effects, increasing the expression of anabolic mediators, reducing oxidative stress, and regulating autophagy, which results in reduced chondrocyte death, collagen degradation, and cartilage protection [33]. Regular consumption of green tea may positively impact the physical and mental health of patients.

5.1. Osteoarthritis

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in the use of dietary supplements and functional foods for the treatment of chronic diseases, especially among patients with OA [34,35,36]. Green tea is one of the main herbal remedies considered for the treatment of OA, as it contains numerous catechins that are responsible for controlling inflammation and repairing bone and cartilage tissues in OA [35,37]. Due to the lack of clinical trials confirming the effectiveness of green tea in the treatment of OA, Hashempur et al. conducted a randomized trial in 2018 to evaluate its effect on the treatment of this disease. This study included women and men aged 40–75 years and excluded individuals with severe OA, coronary heart disease, liver and kidney failure, pregnant and breastfeeding women, and individuals unable to take their own medications. Eligible patients were divided into two groups: one group received green tea tablets and diclofenac, and the other (control group) received diclofenac alone. Additionally, the patients were required to maintain a diet and be physically active throughout the study. Significant improvements were observed in all scores in the green tea group, whereas only one pain indicator, the WOMAC scale, improved in the control group. No adverse events were observed in the green tea group. However, this study was limited by the small patient population and the lack of objective measures of participant functionality, which may also be subject to bias. The lack of a placebo comparison group and dose adjustments are additional methodological issues in this study that should be addressed [38]. Therefore, longer studies that address these shortcomings are necessary to obtain a more reliable assessment of the use and safety of green tea in clinical practice.

5.2. Rheumatoid Arthritis

In recent years, new strategies based on non-drug therapies, such as exercise and physical activity, along with natural plant products, have gained significant attention in the treatment of RA [39,40,41]. Currently, clinical data evaluating the efficacy of green tea catechins (e.g., EGCG) as an adjunct to standard disease-modifying treatment for RA are limited. Alghadir et al. conducted a study in elderly individuals in which participants were assigned to one of the following groups: green tea, a supervised exercise program, or infliximab. Combinations (e.g., green tea + exercise) were also analyzed separately. After 6 months, the green tea groups both in monotherapy and in combination with exercise or infliximab, showed significant improvements in disease activity markers (CRP, ESR, number of swollen and tender joints, and mHAQ score) and increased bone remodeling markers (deoxypyridinoline, NTX, and BAP). The authors reported that EULAR/ACR assessments indicated greater clinical improvement in patients receiving green tea plus exercise than in those receiving infliximab alone [42]. However, it is difficult to directly correlate bone markers with RA activity in such a short time, and the study did not include a placebo or a controlled comparable dose of polyphenols. This study provides a hypothesis-based approach but does not provide RCT-level evidence for the efficacy of catechins as an adjunct to disease-modifying treatment in RA. Green tea may be considered an adjunct in patients with OA and RA, but it does not replace standard treatment-to-target therapy, and caution is warranted with highly concentrated preparations. Although green tea infusion is usually well tolerated, the use of EGCG-rich concentrates/extracts has been sporadically associated with hepatotoxicity, with the risk increasing with the dose (especially in the fasting state). The EFSA recommends caution in supplementation; doses up to 800 mg/day have been considered safe. In tea infusions, a dose of 90–300 mg/day of EGCG is permitted. Animal studies have shown EGCG’s liver toxicity at very high doses. However, with daily use of tea infusions, it is difficult to reach a toxic dose, as one cup of tea (270 mL) contains approximately 50–100 mg of EGCG, depending on the type of tea; with longer-term use, ALT/AST monitoring is worth considering [43,44,45].

The number of published studies on catechins in the context of OA and RA found in the publicly available English-language literature is one for each of these conditions. This demonstrates how much research remains to be performed on catechins’ anti-inflammatory potential and possible applications in joint and muscle disorders. Despite growing interest in studying substances naturally occurring in commonly available food products as green tea, this field remains a black spot on the map of In Vivo research on laboratory animals and clinical trials.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Data from in vitro studies, animal models, and preliminary randomized controlled trials indicate that green tea catechins, particularly EGCG, have significant therapeutic potential in the treatment of OA and RA. In vitro studies have consistently confirmed their ability to modulate key inflammatory pathways, including NF-κB, MAPK, and TAK1, and to inhibit cartilage matrix degradation by limiting the activity of metalloproteinases and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Animal models have extended these observations, suggesting that intra-articular administration of EGCG may improve joint function and reduce the severity of degenerative changes. Although the agreement between different levels of evidence is clear, the consistency in clinical effects is less clear due to differences in dosage, route of administration, and experimental conditions.

The greatest challenge remains the low oral bioavailability of catechins, which significantly hinders the translation of effective doses from experimental models to realistic clinical settings. In animal studies, the doses used are much different than those considered effective in humans, and the lack of detailed pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies in patients with OA and RA prevents a precise assessment of whether the concentrations corresponding to the effects observed in the laboratory are achievable in practice. Although regular consumption of green tea is considered safe and moderate doses of EGCG are well tolerated, the optimal dosage parameters for adjunctive therapy remain unknown.

This study contains experimental data contained in full-text articles published in open-access indexed journals published only in English. Available data from randomized trials, while promising, are sparse, based on small patient groups, and often lack standardized dosing regimens and objective endpoints. A reliable assessment of the risk of bias is also lacking, significantly limiting the ability to draw firm conclusions regarding the efficacy, safety, and potential synergistic effects of catechins when used with conventional therapies. The current results suggest that catechins may reduce inflammation, improve the quality of life, and potentially slow disease progression; however, the magnitude of these effects remains uncertain. The existing literature lacks a coherent and comprehensive analysis of the main research gaps. Currently available studies only sporadically address the issue of low bioavailability, the limited number of clinical trials, or the lack of safety data for higher doses of EGCG, but they do not provide a complete synthesis of the problems. There are also new, interesting approaches to the evaluation of EGCG and catechins in pharmacology that go beyond traditional methods of testing active substances in cellular systems or animal models. The authors of one of the latest studies used a bioinformatics approach and conducted network pharmacology analyses to identify associations between tea components and genes key to the pathogenesis of OA and RA [1]. These studies broaden the cognitive perspective by identifying potential molecular targets and signaling pathways that may be modulated by green tea polyphenols, emphasizing the need for further integration of experimental data with systemic analyses.

Given these limitations, further advanced research is necessary, including well-designed preclinical and clinical studies and thorough methodological analyses. This will not only allow for a better understanding of the mechanisms of action of catechins but also for assessing their true therapeutic potential and developing strategies to increase their bioavailability of catechins. Since the recommended daily dose of EGCG for healthy individuals has already been determined, there is a need for further detailed studies on laboratory animals and extensive clinical trials to determine the method of administration, frequency of use and pharmacological formulation of EGCG in order to obtain the best possible clinical effects. There is still a lack of robust randomized clinical trials in OA assessing structural changes in the joint, well-designed studies in RA considering adjunctive or equivalence therapy, and detailed pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analyses of these drugs. Knowledge of the interactions between catechins and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and NSAIDs is also limited, even though such combinations are common in clinical practice.

In the long term, green tea and its polyphenols may prove to be valuable, low-toxicity treatment options for OA, RA, and perhaps other musculoskeletal conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.P.; Investigation, O.B. and P.P.; Resources, O.B. and P.P.; Data Curation, O.B. and P.P.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, O.B. and P.P.; Writing—Review and Editing, K.P.; Visualization, O.B. and P.P.; Supervision, K.P.; Funding Acquisition K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACLT | Anterior cruciate ligament transection |

| AGE | Advanced glycation end-product |

| ARE | Antioxidant response element |

| CIA | collagen-induced inflammation |

| CITED2 | Interacting Transactivator |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase 2 |

| DMARDs | Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs |

| DMM | The surgical destabilization of the medial meniscus |

| EC | Epicatechin |

| ECG | Epicatechin gallate |

| EGCG | Epigallocatechin gallate |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor alpha |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| IL | Interleukin |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IP-10 | Interferon-γ-inducible protein-10 |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| RA | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| TAC | Total antioxidant capacity |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

References

- Xie, X.; Fu, J.; Gou, W.; Qin, Y.; Wang, D.; Huang, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, X. Potential mechanism of tea for treating osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1289777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X. Rheumatoid arthritis: Pathogenesis and therapeutic advances. Medcomm 2024, 5, e509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liang, J.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, G.; Jing, Z.; Lv, L.; Nan, K.; Dang, X. The Burden of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Findings from the 2019 Global Burden of Diseases Study and Forecasts for 2030 by Bayesian Age-Period-Cohort Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgino, R.; Albano, D.; Fusco, S.; Peretti, G.M.; Mangiavini, L.; Messina, C. Knee Osteoarthritis: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Mesenchymal Stem Cells: What Else Is New? An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa, B.R.; Pereira, T.V.; Saadat, P.; Rudnicki, M.; Iskander, S.M.; Bodmer, N.S.; Bobos, P.; Gao, L.; Kiyomoto, H.D.; Montezuma, T.; et al. Effectiveness and safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioid treatment for knee and hip osteoarthritis: Network meta-analysis. BMJ 2021, 375, n2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerschbaumer, A.; Sepriano, A.; Bergstra, S.A.; Smolen, J.S.; van der Heijde, D.; Caporali, R.; Edwards, C.J.; Verschueren, P.; de Souza, S.; E Pope, J.; et al. Efficacy of synthetic and biological DMARDs: A systematic literature review informing the 2022 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 82, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Akhtar, N.; Haqqi, T.M. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechi3-gallate: Inflammation and arthritis. Life Sci. 2010, 86, 907–918, Erratum in Life Sci. 2010, 87, 196.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fechtner, S.; Singh, A.; Chourasia, M.; Ahmed, S. Molecular insights into the differences in anti-inflammatory activities of green tea catechins on IL-1β signaling in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2017, 329, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatoniene, J.; Kopustinskiene, D.M. The Role of Catechins in Cellular Responses to Oxidative Stress. Molecules 2018, 23, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Tang, H.; Cao, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Ma, D.; Guo, C. Epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate ameliorates oxidative stress-induced chondrocyte dysfunction and exerts chondroprotective effects via the Keap1/Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2022, 100, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhong, Y.; Rajabi, S. Polyphenols and post-exercise muscle damage: A comprehensive review of literature. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Rahman, A.; Hasnain, A.; Lalonde, M.; Goldberg, V.M.; Haqqi, T.M. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits the IL-1 beta-induced activity and expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and nitric oxide synthase-2 in human chondrocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, N.; Haqqi, T.M. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate suppresses the global interleukin-1beta-induced inflammatory response in human chondrocytes. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011, 13, R93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, Z.; Anbazhagan, A.N.; Akhtar, N.; Ramamurthy, S.; Voss, F.R.; Haqqi, T.M. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits advanced glycation end product-induced expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and matrix metalloproteinase-13 in human chondrocytes. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009, 11, R71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.-J.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, E.-K.; Moon, Y.-M.; Jung, Y.O.; Park, S.-H.; Cho, M.-L. EGCG attenuates autoimmune arthritis by inhibition of STAT3 and HIF-1α with Th17/Treg control. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, K.; Holstein, J.; Laurence, A.; Ghoreschi, K. Targeting JAK/STAT signalling in inflammatory skin diseases with small molecule inhibitors. Eur. J. Immunol. 2017, 47, 1096–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegazzi, M.; Campagnari, R.; Bertoldi, M.; Crupi, R.; Di Paola, R.; Cuzzocrea, S. Protective Effect of Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) in Diseases with Uncontrolled Immune Activation: Could Such a Scenario Be Helpful to Counteract COVID-19? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, F.; Massaro, A.; Mauro, M.; Allegra, M.; Arizza, V.; Tesoriere, L.; Restivo, I. Cooperative Interaction of Hyaluronic Acid with Epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate and Xanthohumol in Targeting the NF-κB Signaling Pathway in a Cellular Model of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jówko, E.; Długołęcka, B.; Makaruk, B.; Cieśliński, I. The effect of green tea extract supplementation on exercise-induced oxidative stress parameters in male sprinters. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 54, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, R.; Falahi, Z. Effect of green tea extract on exercise-induced oxidative stress in obese men: A randomized crossover study. Asian J. Sports Med. 2017, 8, e55438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Umar, S.; Riegsecker, S.; Chourasia, M.; Ahmed, S. Regulation of Transforming Growth Factor β-Activated Kinase Activation by Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate in Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovial Fibroblasts: Suppression of K(63)-Linked Autoubiquitination of Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor-Associated Factor 6. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016, 68, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adcocks, C.; Collin, P.; Buttle, D.J. Catechins from green tea (Camellia sinensis) inhibit bovine and human cartilage proteoglycan and type II collagen degradation In Vitro. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, D.J.; Choudhury, M.; Hanstein, R.; Hirsh, D.M.; Kim, S.J.; Majeska, R.J.; Schaffler, M.B.; Hardin, J.A.; Spray, D.C.; Goldring, M.B.; et al. Green tea polyphenol treatment is chondroprotective, anti-inflammatory and palliative in a mouse post-traumatic osteoarthritis model. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2014, 16, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-T.; Cheng, T.-L.; Ho, C.-J.; Huang, H.H.; Lu, C.-C.; Chuang, S.-C.; Li, J.-Y.; Lee, T.-C.; Chen, S.-T.; Lin, Y.-S.; et al. Intra-Articular Injection of (-)-Epigallocatechin 3-Gallate to Attenuate Articular Cartilage Degeneration by Enhancing Autophagy in a Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis Rat Model. Antioxidants 2020, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramés, B.; Taniguchi, N.; Otsuki, S.; Blanco, F.J.; Lotz, M. Autophagy is a protective mechanism in normal cartilage, and its aging-related loss is linked with cell death and osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Z.; Zhang, X.; Sun, M. Phytochemicals Mediate Autophagy Against Osteoarthritis by Maintaining Cartilage Homeostasis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 795058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinatier, C.; Domínguez, E.; Guicheux, J.; Caramés, B. Role of the Inflammation-Autophagy-Senescence Integrative Network in Osteoarthritis. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susmiarsih, T.P.; Hadi, R.S.; Sofwan, A.; Kuslestari, K.; Razari, I. Effect of Green Tea Extract to the Degree of Knee Joint Damage and Nitric Oxide Levels in the Rabbit Osteoarthritis Model. Proc. ISETH 2019, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-T.; Cheng, T.-L.; Yang, C.-D.; Chang, C.-F.; Ho, C.-J.; Chuang, S.-C.; Li, J.-Y.; Huang, S.-H.; Lin, Y.-S.; Shen, H.-Y.; et al. Intra-Articular Injection of (-)-Epigallocatechin 3-Gallate (EGCG) Ameliorates Cartilage Degeneration in Guinea Pigs with Spontaneous Osteoarthritis. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Rajaiah, R.; Wu, Q.-L.; Satpute, S.R.; Tan, M.T.; Simon, J.E.; Berman, B.M.; Moudgil, K.D. Green tea protects rats against autoimmune arthritis by modulating disease-related immune events. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 2111–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haqqi, T.M.; Anthony, D.D.; Gupta, S.; Ahmad, N.; Lee, M.-S.; Kumar, G.K.; Mukhtar, H. Prevention of collagen-induced arthritis in mice by a polyphenolic fraction from green tea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 4524–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeser, R.F.; Collins, J.A.; Diekman, B.O. Ageing and the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2016, 12, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk, H.-Y.; Appell, C.; Chyu, M.-C.; Chen, C.-H.; Wang, C.-Y.; Yang, R.-S.; Shen, C.-L. Impacts of Green Tea on Joint and Skeletal Muscle Health: Prospects of Translational Nutrition. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijlsma, J.W.; Berenbaum, F.; Lafeber, F.P. Osteoarthritis: An update with relevance for clinical practice. Lancet 2011, 377, 2115–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Cimmino, M.A.; Scarpa, R.; Caporali, R.; Parazzini, F.; Zaninelli, A.; Atzeni, F.; Marcolongo, R. Do physicians treat symptomatic osteoarthritis patients properly? Results of the AMICA experience. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 35, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.U.; Jamshed, S.Q.; Ahmad, A.; Bidin, M.A.; Siddiqui, M.J.; Al-Shami, A.K. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine among Osteoarthritic Patients: A Review. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, JE01-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katiyar, S.K.; Raman, C. Green tea: A new option for the prevention or control of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011, 13, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashempur, M.H.; Sadrneshin, S.; Mosavat, S.H.; Ashraf, A. Green tea (Camellia sinensis) for patients with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized open-label active-controlled clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, I.E.; Nader, G.A. Molecular effects of exercise in patients with inflammatory rheumatic disease. Nat. Clin. Pract. Rheumatol. 2008, 4, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegsecker, S.; Wiczynski, D.; Kaplan, M.J.; Ahmed, S. Potential benefits of green tea polyphenol EGCG in the prevention and treatment of vascular inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Life Sci. 2013, 93, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotte, H.; Ruth, J.H.; Campbell, P.L.; Koch, A.E.; Ahmed, S. Green tea extract inhibits chemokine production, but up-regulates chemokine receptor expression, in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts and rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. Rheumatology 2009, 49, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghadir, A.H.; Gabr, S.A.; Al-Eisa, E.S. Green tea and exercise interventions as nondrug remedies in geriatric patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 2820–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS); Younes, M.; Aggett, P.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Dusemund, B.; Filipič, M.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; Gott, D.; et al. Scientific opinion on the safety of green tea catechins. EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee on Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and the Environment (COT). Statement on the Hepatotoxicity of Green Tea Catechins [Internet]; Food Standards Agency: London, UK, 2024. Available online: https://cot.food.gov.uk/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]; National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2012; Green Tea; Updated 20 November 2020. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547925/ (accessed on 16 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).