Abstract

This study investigates the use of fungal strains as an eco-friendly and cost-effective approach to enhance the protein content of sugarbeet pulp (SBP) via semi-solid fermentation (SmF). The effects of ultrasonication (US) and hydrothermal (HT) pretreatments, combined with SmF, were evaluated with respect to the nutritional and technological characteristics of the resulting SBP fungal biomass. Fermentation using filamentous fungi, such as Aspergillus nidulans CCF2912, Botrytis cinerea CCF2361, and Rhizopus arrhizus CCF1502, increased the protein content of SBP fungal biomass from 53.7 to 93.82–134.11 mg/g d.w. and improved the essential amino acid (EAA) ratio from 0.81 to 1.96. Nucleic acid (NA) content in the end product was decreased by 20.3–31.5% following additional sterilisation at 90 °C for 30 min, while mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids increased from 2.36 to 4.93% and from 5.11 to 10.16% of total fatty acids, respectively. Tryptic digestion of SBP fungal biomass proteins allowed in silico prediction of peptides (up to 2 kDa) with potential DPPH, hydroxyl, and ABTS•+ radical scavenging activities. Among the tested fungi, R. arrhizus CCF1502 grown on US-treated SBP substrate showed the highest protein biomass yield and overall nutritional quality. These findings demonstrate that integrating thermal pretreatment with SmF provides a sustainable and efficient strategy to enhance the protein yield and nutritional value of SBP, supporting its potential application as a functional ingredient in food and feed applications.

1. Introduction

Global food production faces increasing pressure to reduce waste and identify sustainable sources of protein. Agro-industrial by-products represent a growing global challenge, as their valorisation is essential for advancing circular economy strategies and developing sustainable protein alternatives. Therefore, these residues represent a significant resource for the development of sustainable bioproducts and bioenergy [1]. Among these crops, sugar beet has an annual yield of approximately 80 Mt, with each ton producing around 500 kg of wet sugar beet pulp (SBP) as a by-product of sugar manufacturing through shredding and extraction [2]. SBP, due to its heterogeneous composition, represents a promising substrate for generating value-added bioproducts such as microbial protein, offering both economic and environmental advantages [3,4].

Global protein consumption has increased significantly over the past five decades, raising concerns regarding the environmental impact of animal-based protein production. This has spurred considerable interest in alternative protein sources. Since the middle of the 20th century, there have been ongoing efforts to identify innovative protein sources, including plant-derived proteins, insect-based meals, and single-cell proteins, produced from waste biomass and food industry by-products [5,6,7]. Plant-based foods, particularly legumes and cereals, could be a viable protein alternative to animal-based foods [8,9]; however, from another perspective, they can have limitations, including lower digestibility and imbalances in essential amino acid content [10,11].

Research on fungi as an alternative protein source and as an option for sustainable bioactive peptide production has future prospects, considering the diversity of non-toxic and non-pathogenic species and strains that require minimal nutrients. Only a small portion of fungi (about 2%) are truly toxic, while a small part (about 4–5%) is recognised as suitable for food consumption [12]. Sugar beet pulp possesses a nutritional composition that supports its suitability as a substrate for fungal growth. It is rich in fermentable carbohydrates, including pectins, hemicellulose, and residual sugars, which fungi can readily utilise as carbon sources [13]. In addition, SBP contains moderate levels of proteins, minerals, and trace nutrients that further contribute to fungal metabolism and biomass formation. This combination of readily accessible carbon, supportive nutrients, and high moisture content provides a favourable environment for fungal cultivation. Fungal biomass derived from edible filamentous fungi through fermentation is a promising alternative protein source [14,15,16]. These proteins are characterised by a high protein-to-carbohydrate ratio, balanced amino acid composition, and low-fat content [17]. Several microorganisms, including bacteria (e.g., Rhodobacter capsulatus), yeasts (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia pastoris, Candida utilis, Torulopsis glabrata, and Geotrichum candidum), and filamentous fungi (e.g., Aspergillus oryzae, Fusarium venenatum, Trichoderma, and Rhizopus), are categorised as GRAS (generally regarded as safe) and have been studied for protein production [18,19,20,21]. Furthermore, the ability of fungi to produce amylolytic, cellulolytic, and lipolytic enzymes allows them to thrive on a wide range of substrates, including food-processing residues [22,23]. Thus, selecting an appropriate substrate for fungal biomass production intended for human consumption poses a challenge, as it must provide sufficient nutrients for optimal fungal growth while meeting safety standards.

Fungal proteins obtained through cost-effective and sustainable fermentation processes have applications in food production as meat analogues, enzymes, and food additives [5,18,21]. Moreover, fungal biomass has a protein-digestibility-corrected amino acid score similar to that of milk protein (0.996:1), higher than chicken and beef; thus, mycoprotein likewise promises to be a novel alternative protein source of better quality than plant proteins [24]. Despite these advantages, the growth rates of fungi and protein yield are generally lower compared to other microorganisms, and fungal biomass often contains moderate levels of nucleic acids [16]. Furthermore, fungal-derived bioactive peptides are increasingly attracting significant academic research interest due to their high-quality protein content and environmentally friendly potential. Fungi encompass a diverse range of species, some of which remain underexplored and have demonstrated the ability to synthesise complex peptides with potent bioactivities [25,26]. Previous studies reveal that the antioxidant capacity of peptides is related to amino acid composition and sequences in which they are present [27]. Bioactive peptides can be produced through protein hydrolysis and microbial fermentation. These peptides are protein fragments, typically consisting of 2–20 amino acid residues and remain inactive while encrypted within the parent protein. The most extensively studied method for bioactive peptide production is considered in vitro enzymatic hydrolysis employing pepsin, chymotrypsin, and especially trypsin [28].

Research on the nutritional valorisation of sugar beet pulp has thus far been scarcely explored. The present study aims to evaluate the potential of new fungal strains of Aspergillus nidulans CCF2912, Botrytis cinerea CCF2361, and Rhizopus arrhizus CCF1502 for biomass production on pretreated SBP substrates via semi-solid fermentation, identifying the most promising strain in terms of biomass yield and nutritional quality. Specifically, analyses were conducted on the protein content, amino acid composition, fatty acid profile, nucleic acid content, antioxidant-active peptide sequences, as well as the morphological and technological properties of the resulting protein-rich products. The relevance of the work is highlighted by the sustainable bioconversion of agro-industrial residues into value-added nutritional resources for food and feed applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material

Wet sugar beet pulp (SBP) was obtained from the company SC “Nordic Sugar Kėdainiai” (Kėdainiai, Lithuania). The SBP material was dried in a convection oven at 40 °C to a constant weight and ground using a laboratory mill (A10, IKA-Werke, Staufen, Germany) to powder (315–500 µm particles). The dried raw material was stored at 4 °C in a tightly closed plastic bag during the experiment. The chemical composition of SBP raw material was analysed in a previous study [29].

2.2. Fungal Strains

Six fungal strains of Aspergillus spp., Fusarium spp., Botrytis spp., Penicillium spp., Rhizopus spp., and Verticillium spp., kindly provided by the Culture Collection of Fungi (CCF) of the Department of Botany of Charles University (Prague, Czech Republic) for research purposes, were used in the experiment. Each fungal strain was maintained on agar slants, containing 0.2% malt extract, 0.2% yeast extract, 2% glucose, and 2% agar. Freshly inoculated slants were incubated at 25 °C for 5 days and then stored at 4 °C.

2.3. Fungal Inoculum Preparation

A fungal spore suspension was prepared from a 5-day-old, freshly sporulated culture, as described by Aberkane et al. [30]. To obtain spores, the fungal colonies were covered with 2–3 mL of a 1% Tween 20 (Sigma-Aldrich, Hamburg, Germany) solution in sterile distilled water (pH 8.0). The conidia were agitated with a sterile spatula and transferred to sterile tubes. The cell suspension was then vortexed at 2200× g for 20 s using a VWR Reax Top Mixer (VWR International, Orange, CA, USA). Spore concentrations were adjusted to 106 CFU/mL by counting with a haemocytometer (BLAUBRAND® Neubauer chamber; Merck, Madrid, Spain) and used for further experiments.

2.4. Fungal Biomass Production

Fungal fermentation was performed in a 1 m3 sterilised (121 °C; 20 min) fermenter under semi-solid fermentation (SmF) conditions. The fermentation medium, containing SPB powder in distilled water (80 g/L; pH 7), was transferred to the vessel and sterilised (121 °C; 15 min) before inoculation with 5 mL of fungal spores’ suspension (5.6 × 106 spores/mL), pre-cultured in 0.5 L shake flasks. For the second experiment, SBP medium was autoclaved at 121 °C for 30 min (Systec, Linden, Germany) or sonicated in an ultrasonic bath (Ulsonix Ultrasonic cleaner Proclean 3.0 DSP, Ulsonix, Teltow, Germany) at 70 °C for 40 min (100% US intensity) before fermentation, After cooling to 25 °C, samples were inoculated with selected fungal suspensions and subjected to fermentation at the same conditions as described. Fermentations were performed for 9 days at a controlled temperature of 25 °C without pH adjustment; the initial pH was 5, and after fermentation, pH dropped to a range between 4.2 and 3.9. Fermented SBP biomass samples were collected after 72, 120, 168, and 216 h; lyophilised (Alpha 1-2 LDplus, Christ, Osterode, Germany); and subjected to further analysis.

2.5. Chemical Analysis

The total protein content in SBP fungal biomass samples was determined by the Kjeldahl nitrogen method (AOAC method 920.152; nitrogen to protein conversion factor 6.25) [31]. The quantification of soluble (SDF) and insoluble (IDF) dietary fibres was measured by using an integrated total dietary fibre assay procedure (K-TDFR, Megazyme, Co., Wicklow, Ireland), according to the producer protocol. The determination of acid-insoluble lignin was performed according to the methodology described by Gaizauskaite et al. [29].

2.6. Amino Acid Analysis

Amino acids were determined by the Ultrafast Liquid Chromatography (UFLC) LC-20AD coupled with an RF-20A fluorescence detector (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) with automated o-phthalaldehyde (OPA)/9-fluorenylmethyl chloroformate (FMOC) derivatisation. For the analysis, 0.1 g of the dried SBP biomass was placed into a reaction vessel, followed by the addition of 25 mL of 6 M hydrochloric acid. The vessel was sealed and subjected to hydrolysis in a furnace at 110 °C for 24 h. After hydrolysis, the sample was allowed to cool to room temperature and then transferred into a 250 mL volumetric flask. It was subsequently diluted with a 0.2 M citrate with 0.1% phenol buffer solution (pH 2.20). The pH was adjusted to 2.20 by adding 17 mL of 7.5 M sodium hydroxide solution. The mixture was then brought to a final volume of 250 mL using the same citrate buffer. Prior to the analysis, the solution was filtered through a 0.22 μm PVDF membrane filter. The amino acid standards (A9781, Sigma-Aldrich, Schnelldorf, Germany) of 0.5 μmole/mL concentrations, except for L-cystine at 0.25 μmole/mL in 0.2 N sodium citrate (pH 2.20), were analysed. A five-level calibration set with R2 > 0.999 was used, covering a concentration range of 0.006–0.20 μmol/mL, except for alanine and cysteine, each covering a concentration range of 0.06–1.00 μmol/mL.

2.7. Fatty Acid Analysis

Total fatty acid analysis was performed according to Sönnichsen and Müller [32]. Total lipids were extracted from a 0.2 g dried biomass sample with a 5 mL chloroform: methanol (2:1) solution. Samples were incubated in a rotation shaker for 60 min in total, with 5 min sonication every 30 min. Phase separation was obtained by the addition of 1.5 mL milli-Q water and centrifugation (15,000× g, 6 min). The chloroform phase was collected and pooled with a second extract using 4 mL of chloroform. The composition of fatty acids was determined in extracted lipids re-dissolved in hexane. Methylation of fatty acids was performed by adding 0.25 mL of 1.0 N NaOH in methanol and incubating the samples at room temperature for 2 h. Milli-Q water (0.2 mL) was added to stop the reaction, and 2.5 mL petroleum ether: diethyl ether (4:1) solution was used as the extraction solvent for fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs). After centrifugation (15,000× g, 6 min), the ether phase was evaporated under nitrogen, and FAMEs were re-dissolved in hexane. FAMEs were analysed using GC-FID (GC-2010 PLUS, Shimadzu, Inc., Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a RT 2560 column (100 cm × 0.25 mm × 0.22 μm). The reference standard 37 Component FAME Mix (Supelco, Inc., Bellefonte, PA, USA) was used for fatty acids identification. The fatty acids were expressed as a percentage of total fat.

2.8. Nucleic Acid Analysis

For the nucleic acid analysis, the SBP samples after fungal fermentation were additionally heated at 90 °C in a water bath for 15 and 30 min to inactivate fungi and reduce nucleic acids. Sterilised samples were lyophilised (Alpha 1-2 LDplus, Martin Christ, Osterode, Germany) and subjected to the analysis. The analysis of nucleic acids was performed according to Kumar and Mugunthan [33]. Each of the SBP fungal biomass samples (0.5 g) was transferred into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube and mixed with 1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (137 mM NaCl, 10 mM phosphate, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4) using a vortex mixer (Remi, Mumbai, India) followed by centrifugation (UniCen MR, HeroLab, Wiesloch, Germany). After centrifugation, 250 μL of lysis buffer (10% SDS, 0.5 M EDTA, 17.5% NaCl, and 10 M NaOH) was added to the pellet, and the mixture was incubated at 95 °C for 20 min. Following lysis, 500 μL of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) was added, mixing vigorously, and the sample was centrifuged at 10,000× g for 15 min at 4 °C (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The upper aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube, where 480 μL of chloroform and 20 μL of isoamyl alcohol were added. This mixture was again centrifuged under similar conditions. To the recovered supernatant, a 0.1 volume of 0.3 M sodium acetate and 0.7 volume of isopropanol were added. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min, then centrifuged at 10,000× g for 15 min to precipitate the DNA. The resulting DNA pellet was washed twice with 200 μL of chilled ethanol (4 °C), centrifuged at 6000× g for 2 min, and then dried at 60 °C for 5 min. The sample was resuspended in the TE buffer, and optical density was measured at 260 and 280 nm using a spectrophotometer (UV 1800 Shimadzu, Inc., Kyoto, Japan).

2.9. Protein Isolation and Digestion

For protein extraction, 0.2 g of lyophilised SBP fungal biomass was accurately weighed and resuspended in 1 mL of 8 M urea prepared in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0). The suspension was incubated in the dark for 1 h to ensure complete rehydration. Protein solubilisation was facilitated by sonication using a 30 s on/off cycle for a total of 10 min. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 20,000× g for 15 min. The soluble protein fraction of 200 µL was transferred into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. To reduce the urea concentration and allow enzyme activity, samples were diluted with 50 mM Tris-HCl to a final urea concentration of ≤2 M. Proteins were digested with trypsin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) at controlled conditions (37 °C; 16 h; enzyme-to-substrate ratio 1:50). The reaction was stopped and the samples were acidified by addition of 10% formic acid to a final concentration of 1%. Digested samples were clarified by centrifugation at 21,300× g for 10 min and filtered through a 0.22 µm syringe filter. Lastly, digests were ultrafiltered through Millipore filters with 10 kDa MWCO (Pall Corporation, New York, NY, USA), and the flow-through was collected. The flow-through was diluted 2-fold, and Hi3 PhosB standard was added to a final concentration of 0.1 pmol/µL. Samples were transferred to vials and used for LC-MS/MS analysis.

2.10. Peptide Separation by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS/MS)

Liquid chromatography (LC) separation of peptides after trypsin digestion was performed using Dionex Ultimate3000 RSLCnano (Dionex Softron GmbH, Germering, Germany). Peptides were concentrated on an Acclaim PepMap 100, 5 μm, 100 μm × 2 cm (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vilnius, Lithuania) trap column equilibrated with 2% acetonitrile with 0.1% trifluoracetic acid at a 5 µL/min flow rate. Afterwards, peptides were separated on an Acclaim PepMap RSLC 3 μm, 75 μm × 15 cm (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vilnius, Lithuania) analytical column at a flow rate of 0.3 µL/min. The isocratic elution 4% solvent B was set until 10 min, then a linear gradient from 4% to 45% solvent B was set until 70 min, followed by a linear gradient from 45 to 99% solvent B until 85 min, from 99% to 4% solvent B until 86 min and isocratic 4% solvent B until 96 min (solvent A: 0.1% formic acid, solvent B: 80% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid). The column compartment temperature was set to 30 °C. Injection volume was set to 10 µL.

The LC was coupled online with an LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) equipped with a Nanospray Flex ionisation source. Data was acquired using Chromeleon version 6.8 software (Dionex Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and XCalibur version 2.1 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). LC-MS/MS data was collected using data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode for the six most intense ions for 85 min, and dynamic exclusion was set for 120 s. The mass range for full scan was set to 275–2000 Da, resolution for the Orbitrap detector was 30,000, automatic gain control (AGC) was set to 2 × 105 ions, and maximum injection time was set to 10 ms. A normalised collision energy of 35.0 was used for collision-induced dissociation (CID) fragmentation, and a charge state rejection of +1 was enabled. MS/MS spectra were acquired using an Iontrap detector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany), AGC was set to 1 × 104 ions, and maximum injection time was set to 100 ms. The source conditions were set as follows: positive polarity, capillary voltage 1.77 kV, and capillary temperature 200 °C.

2.11. Protein and Peptide Identification

For peptide identification, Thermo.RAW files were analysed using PEAKS Studio version 8.5 (Bioinformatics Solutions, Waterloo, ON, Canada). Protein sequence data used for database construction were obtained from the UniProt Consortium’s Universal Protein Resource (https://www.uniprot.org/) [34]. The identification database was compiled from the amino acid sequences of the sugar beet reference proteome (UniProt ID: UP000035740), rabbit glycogen phosphorylase (UniProt ID: P00489), Aspergillus nidulans (UniProt ID: UP000000560), Rhizopus oryzae (UniProt ID: UP000716291), and Botrytis fuckeliana (UniProt ID: UP000008177). Proteins were reduced with 10 mM DTT for 45 min at 56 °C and alkylated with 20 mM iodoacetamide for 30 min in the dark at room temperature to ensure carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues. A mass error tolerance of 10 ppm was applied for precursor ions and 0.5 Da for fragment ions. Carbamidomethylation of cysteine was set as a fixed modification, while deamidation of asparagine and glutamine, oxidation of methionine, and carbamylation of lysine or the peptide N-terminus were defined as variable modifications. Trypsin was selected as the digestion enzyme, and non-specific cleavage was allowed at both peptide termini. For protein identification, PEAKS automatically generated a decoy database using reversed sequences. Peptide-spectrum matches were filtered at a 1% false discovery rate (FDR). Identification thresholds of −10 lgP > 15 for peptides and −10 lgP > 20 for proteins were applied.

2.12. Prediction of Peptide Bioactivity

The bioactive potential of peptides identified in the fungal hydrolysates was evaluated in silico, taking into account amino acid composition, hydrophobicity, and post-translational modifications [35]. Predicted activities were cross-referenced with the BIOPEP-UWM database (https://biochemia.uwm.edu.pl/en/biopep-uwm-2/ accessed on 10 November 2025) and the scientific literature to prioritise the most promising bioactive sequences.

2.13. The DPPH Radical-Scavenging Activity Assay

The DPPH radical scavenging activity was measured following Kou et al. [36]. Each protein hydrolysate (see Section 2.9) was diluted with deionised water to a final protein concentration of 5.0 mg/mL, and an aliquot (2.0 mL) of the sample was mixed with DPPH (in 95% ethanol; 2.0 mL, 0.2 mmol/L). The DPPH control was conducted in the same manner, but ethanol was used instead of DPPH. The sample control group contained distilled water instead of the sample. The absorbance was measured after 30 min at 517 nm. The DPPH radicals scavenged by each SBP fungal biomass < 10 kDa peptide fraction. DPPH radical-scavenging activity was calculated as follows: DPPH radical scavenging activity (%): [1 − (Ai − Aj)/A0] × 100, where A0 is the absorbance of the sample; Ai is the absorbance of the sample control; and Aj is the absorbance of the DPPH control. The radical scavenging activity was quantified based on a Trolox calibration curve, and the results were expressed as Trolox equivalent (TE) antioxidant capacity (mg TE/g).

2.14. TEAC Assay

The ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) radical scavenging activity was determined according to Xiaohong et al. [36]. The ABTS•+ radical cation was generated by reacting 7 mmol/L ABTS with 2.45 mmol/L potassium persulfate, followed by incubation in the dark at room temperature for 12 h. Before analysis, the resulting ABTS•+ solution was diluted with phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) to an absorbance of 0.70 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. For the assay, the sample solution was mixed with the diluted ABTS•+ solution at a ratio of 1:100 (v/v), and the absorbance decrease was measured after 30 min. Each measurement included a reagent blank under identical conditions. The radical scavenging activity was quantified based on a Trolox calibration curve, and the results were expressed as Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (mg TE/g).

2.15. The Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Activity Assay

The hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of BHLPE was determined based on Shen et al.’s method [37]. The hydroxyl radical was generated through a Fenton reaction in a system of FeSO4 and H2O2. The reaction mixture consisted of 1.0 mL FeSO4 (9 mmol/L), 1.0 mL H2O2 (8.8 mmol/L), and 1.0 mL of various concentrations of BHLPE and 1.0 mL of salicylic acid (9 mmol/L). The mixture (4.0 mL) was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, and the absorbance of the solution at 510 nm was recorded. Trolox was used as a positive control. The scavenging activity was calculated using the following formula: scavenging activity (%) = [1 − (A1 − A2)/A0] × 100, where A0 is the absorbance of the control (without extract), A1 is the absorbance of the sample, and A2 is the absorbance without hydrogen peroxide.

2.16. Granule Morphology Evaluation

Granule morphology of SBP fungal biomass powder was quantified using a Zeiss Discovery V12 Stereo microscope with PlanApoS 1.5× main object lens, Eyepiece PL 10×/23 Br. Foc, Magnification 12.0–150× and maximum numerical aperture (NA) of 0.144 with object field 19–1.5 mm and free working distance (FWD) of 30 mm. Each powdered sample (0.5 g) was randomly analysed.

2.17. Technological Properties Evaluation

For the determination of the water absorption index (WAI), oil absorption index (OAI), and water solubility index (WSI) of the SBP biomass samples, a gravimetric method was applied. An accurately weighed sample (1.0 g) (m0) was mixed with 5 mL of distilled water or 6 mL of rapeseed oil in a centrifuge tube and incubated for 30 min in a 30 °C water bath. The sample was then centrifuged (8000× g, 15 min) (UniCen MR, HeroLab, Wiesloch, Germany), the liquid part was carefully removed, the wet residue was weighed (m1), and the supernatant was collected and dried at 105 °C until constant weight (m2). WAI, OAI, and WSI were calculated using the equations:

where m0—initial dry weight of the sample (g); m1—weight of the wet residue after centrifugation (g); and m2—weight of dry solids in the supernatant after drying (g).

2.18. Statistical Analysis

All experiments and chemical analyses were performed at least in triplicate. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using SPSS software (ver. 28.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The analysis of variance (ANOVA) using a general linear model was performed on the results and a confidence interval of 95% plus the pairwise comparisons between the data using Fisher’s test were considered.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Biomass Production by Tested Fungi in the SBP-Enriched Medium

Six fungal strains, Rhizopus arrhizus CCF1502, Aspergillus niger CCF3264, Aspergillus nidulans CCF2912, Fusarium solani CCF2967, Penicillium oxalicum CCF3438, and Botrytis cinerea CCF2361, were analysed for their potential for protein biosynthesis and nitrogen accumulation in the differently pretreated sugar beet pulp (SBP)-enriched media (Table 1).

Table 1.

Total amino acid and protein contents (mg/g d.w.) in SBP fungal biomasses.

The filamentous fungi used in this study exhibited complementary cellulolytic activities relevant for sugar beet pulp (SBP) degradation [29]. Among the fungal strains evaluated in this study, clear differences in their polysaccharide-degrading capacities help explain their performance on sugar beet pulp (SBP). Aspergillus nidulans is widely recognised for its extensive repertoire of pectinolytic and hemicellulolytic enzymes, enabling efficient deconstruction of pectin-rich plant biomass [38]. Botrytis cinerea similarly secretes numerous pectin- and hemicellulose-modifying enzymes during plant colonisation, which supports strong growth on complex lignocellulosic substrates [39]. Notably, in our study, R. arrhizus achieved the most pronounced biomass increase on SBP, suggesting that its enzymatic system is well-matched to the carbohydrate profile of this substrate. For efficient fungal growth, the degradation of SBP polymeric carbohydrates is a promising procedure toward increasing the value of this by-product for fermentation [40,41]. Fungi that possess pectinolytic and hemicellulolytic enzyme activities are more able to use SBP as a carbon source and maintain growth, whereas species lacking those enzyme systems show reduced growth [42]. Some fungi, such as Rhizopus spp., are well known for strong pectinolytic and cellulolytic activities and for rapid utilisation of plant pulp biomass [29,43]. Such findings explain why R. arrhizus outperforms growth on the SBP-supplemented medium.

The protein analysis and amino acid (AA) quantification revealed notable variation in both total protein and proteinogenic AA contents and the abundance of individual AA between strains (Table A1, Appendix A). The total protein content in the unfermented SBP was 53.70 mg/g d.w. (Table 2), which is slightly higher than the total amino acid content (52.30 mg/g d.w.) and may be attributed to the presence of non-protein nitrogen. Among the tested fungal strains, B. cinerea showed the highest total protein and amino acid contents (68.31 mg/g and 66.60 mg/g d.w., respectively), followed by A. nidulans (66.65 mg/g and 61.87 mg/g d.w., respectively) and R. arrhizus (59.27 mg/g and 56.90 mg/g d.w., respectively). In contrast, A. nidulans, P. oxalicum, and F. solani produced significantly lower (p < 0.05) protein and amino acid levels (52.74–56.01 mg/g and 47.52–49.01 mg/g d.w., respectively). Although the initial SBP material contained relatively higher total AA levels, the latter strains yielded noticeably lower concentrations. According to previous studies, fungi do not use nitrogen exclusively for protein synthesis; a substantial portion can be incorporated into structural components such as chitin (N-acetylglucosamine) or other nitrogen-containing metabolites [44]. In species like A. nidulans, exhibiting the lowest total AA in our study, nitrogen may be preferentially directed toward these non-protein components, resulting in a lower apparent AA content even if the overall biomass nitrogen is substantial. Additionally, fungal protein synthesis is highly dependent on substrate composition and the availability of specific nutrients. Fungi producing lower AA may require additional nitrogen sources or particular growth conditions to maximise protein accumulation [45]. Therefore, the observed variation in total AA across fungal species likely reflects differences in metabolic priorities rather than reduced growth or activity [46].

Table 2.

Total amino acid and protein contents (mg/g d.w.) in untreated SBP and pretreated SBP fermented by different fungi.

Among the essential amino acids (EAAs), leucine and lysine were found in high concentrations, particularly in B. cinerea and R. arrhizus SBP samples (Appendix A, Table A1). These AAs are vital for cellular structure and metabolic regulation, supporting the suitability of these fungi for biomass and feed production [47]. The presence of other EAAs, such as isoleucine, valine, and phenylalanine, all at the lower levels (1.07–2.89 mg/g d.w.), further reflects the strains’ balanced biosynthetic capabilities.

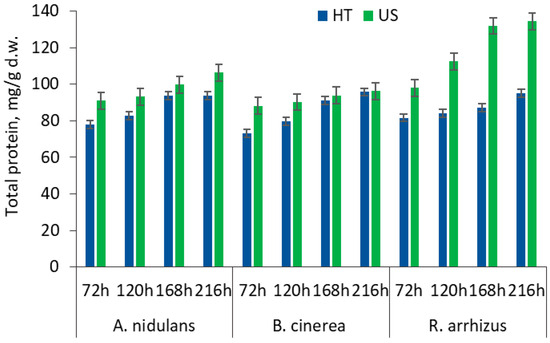

3.2. The Effect of SBP Pretreatments on Fungal Growth Dynamics

Prolonged hydrothermal treatment (HT) (30 min; 121 °C) and sonication (US) (40 min; 70 °C) were applied for the SBP pretreatment before SmF. Figure A1 (Appendix B) presents the results of protein biomass production by A. nidulans, B. cinerea, and R. arrhizus strains in the untreated and pretreated SBP-based medium during a 216 h cultivation period. Table 2 presents the amino acid profile and total protein contents in the differently pretreated SBP fungal biomass after fermentation.

The study indicated that protein contents significantly (p < 0.05) differed between tested fungal strains due to their specific metabolic adaptation in an HT-SBP or US-SBP-based medium (Table 2), according to the literature [48]. Also, the increase in protein content with increasing fermentation time was determined in all SBP samples, depending on the strain used and SBP treatment method (Appendix B, Figure A1).

The maximum protein content was obtained in the US-SBP sample fermented with R. arrhizus (from 97.98 to 134.11 mg protein/g SBP d.w.) during 72–216 h, as the HT-SBP substrate initiated significantly lower (p < 0.05) biomass production during the same period (81.64–94.87 mg/g d.w.) The A. nidulans produced from 90.98 mg/g d.w. to 106.21 mg/g d.w. and from 78.06 mg/g d.w. to 93.71 mg/g protein biomass in the UT-SBP and HT-SBP media, respectively. At the end of fermentation, the protein content in the HT-SBP and US-SBP B. cinerea biomasses was 93.69 and 96.18 mg/g d.w., respectively.

The results suggest that R. arrhizus most successfully adapted to all SBP substrates over the fermentation period, potentially utilising pectinolytic and cellulolytic enzymes to access available nutrients in SBP [49], and the effectiveness of R. arrhizus was enhanced by ultrasonication, increasing the nutrient utilisation [50]. According to the literature, R. arrhizus is especially important in the industrial production of proteins because of the high yield in processes that require the accumulation of biomass within a short time period [8]. However, a depletion of essential nutrients or accumulation of metabolic by-products can inhibit further protein synthesis. These fungal species are an example of how pretreatment methods can enhance or limit the enzymatic system of SBP degradation, as evident from differing protein yield trends.

Overall, the findings indicate that SBP can be an effective substrate for the cultivation of fungi for protein biomass production. The results also suggest that ultrasonication enhances protein content in the SBP fungal biomass more effectively than hydrothermal pretreatment, particularly for R. arrhizus.

The analysis of AAs in the pretreated SBP fungal biomasses after 168 h of fermentation confirmed a significant increase (p < 0.05) in protein nitrogen accumulation (Table 2). The total AA content after the fermentation period was determined to be 2.45- and 1.7 times higher for R. arrhizus, 1.9 and 1.5 times higher for A. nidulans, and on average 1.8-fold higher for B. cinerea in the US-SBP and HT-SBP fungal biomass samples, respectively, compared to the initial AA content in the SBP substrate (52.3 mg/g d.w.).

The US-SBP substrate initiated more efficient growth of R. arrhizus and A. nidulans (protein content was higher by 30.6% and 20.2%, respectively) compared to the HT-SBP samples (Table 2), except for B. cinerea, whose growth was not significantly (p ≥ 0.05) affected by the substrate pretreatment method. This may be due to the double action of the US, as a mechanical force, and temperature compared to only thermal treatment during autoclaving. Ultrasonication at 70 °C enhances the accessibility of nutrients in SBP by mechanically disrupting cell walls and partially depolymerising complex carbohydrates while minimising thermal degradation of heat-sensitive compounds [50,51]. In contrast, hydrothermal treatment (>100 °C), though effective at breaking down structural barriers and sterilising the substrate [52], can lead to a partial loss of simple sugars and amino acids due to heat-induced degradation [53].

The most abundant AAs in all SBP fungal biomasses were aspartic and glutamic acids, following lysine and valine, while asparagine and tryptophan were not detected (Table 2). Aspartic and glutamic acids are important for nitrogen metabolism and carbon flux regulation, and their high abundance reflects active protein biosynthesis and cellular proliferation. The essential amino acids (EAA) content was significantly improved in the SBP samples after fungal fermentation, with an increase ranging between 28.7% and 53.8% in the US-SBP samples and between 20.9% and 37.7% in the HT-SBP samples.

With reference to the FAO recommendations [54], all US-processed SPB fungal biomass samples demonstrated nutritionally favourable protein characteristics, with balanced EAA and NEAA profiles indicative of acceptable protein quality and potential relevance as an alternative nutritional protein source.

3.3. Reduction in Nucleic Acid Content in the SBP Fungal Biomass

The nucleic acid (NA) content in protein biomass is a critical quality parameter, especially when the biomass is intended for food or feed applications. In the production of fungal protein biomass, the selection of substrate has a significant impact on the nutritional value of the final product as well as the presence of potential contaminants.

In this study, the effect of thermal treatment on the elimination of NA in SBP fungal biomass was evaluated (Table 3). The NA contents ranged from 260.5 to 271.0 mg/g in the US-SBP and from 225.4 to 262.2 mg/g in the HT-SBP fungal biomass products. Sterilisation for 15 min (samples S15) allowed a significant (p < 0.05) reduction in the NA contents in all samples (they decreased by 14.2–18.7% in the US-SBP samples and by 9.6–18.2% in the HT-SBP samples fermented with the tested fungi). With an extended treatment time of 30 min, the reduction in the NA levels was even more pronounced (20.3–31.5%), particularly for B. cinerea, where the NA contents decreased substantially, representing a 26.5–31.0% decrease compared to the untreated samples.

Table 3.

Nucleic acid (NA) contents (mg/g) in the unsterilised and sterilised SBP fungal biomasses.

The A260/280 absorbance ratio, which indicates nucleic acid purity, remained relatively stable across all treatments, consistently ranging from 1.8 to 1.9. This suggests that the nucleic acids retained acceptable purity and that the observed reductions are attributed to actual degradation or reduced synthesis rather than extraction inefficiency or contamination [55].

According to Commission Regulation (EU) No 68/2013, crude protein products derived from fungi, such as Saccharomyces spp., Kluyveromyces spp., and Candida utilis, are approved for use in animal feed. To ensure product safety, yeast and fungal cells must be inactivated most effectively through heat treatment of the SBP fungal biomass.

In the case of the NA contents, regular consumption of foods high in nucleic acids may contribute to health issues, such as kidney stones [56]. Importantly, the final NA concentrations fall within the lower range typically reported for fungal single-cell protein and are well below the upper values (up to 18% of dry matter) historically associated with potential safety concerns due to purine load [54,55]. For human consumption, the recommended intake of nucleic acids is below 2% (w/w) [57]. Upon ingestion, nucleic acids are catabolised, producing purines, subsequently elevating plasma uric acid levels, which can lead to health complications [58]. Furthermore, excessive nucleic acid intake has been linked to other risks, such as allergies and toxicity; therefore, reducing the NA levels in the SBP fungal biomass is important for their commercial viability [59].

In addition to nutritional considerations, safety requirements, environmental protection measures, and regulatory aspects must be addressed. These include operational licencing, legal protection of novel production processes and microbial strains, and authorisation of products for specific applications [60]. Excessive intake of nucleic acids by animals or humans can lead to elevated purine levels, which are metabolised into uric acid and may contribute to health issues such as gout or kidney stone formation [61]. Therefore, reducing the nucleic acid content in fungal biomass is essential for enhancing its nutritional profile and ensuring its safety for feed and food applications.

3.4. Fatty Acid Contents in SBP Fungal Biomass

The analysis of saturated (SFA), monounsaturated (MUFA), and polyunsaturated (PUFA) fatty acids, as well as omega-fatty acids (ω-FA), showed that the fermentation of SBP with different filamentous fungi significantly altered the substrate’s overall fatty acids (FA) profile (Table 4). Both US-SBP and HT-SBP samples fermented with R. arrhizus, A. nidulans, and B. cenerea contained significantly lower average SFA levels (84.69–85.15%) compared to the untreated SBP (92.17%), but significantly higher average MUFA (3.78–4.97%), PUFA (9.51–10.14%) and total ω-FA (12.96–14.67%) contents compared to SBP.

Table 4.

Fatty acid contents (% from the total fat) in SBP biomass after fermentation with different fungal strains.

Quantitative data on fatty acid (FA) content in sugar beet biomass or beet pulp are largely unavailable in the literature, likely due to the intrinsically low total lipid fraction of this substrate. Our study demonstrates a very high proportion of saturated fatty acids (SFA) in untreated sugar beet pulp (SBP) biomass (approximately 92%), indicating that the native lipid profile is predominantly saturated. Following fungal fermentation, the SFA fraction consistently decreases to around 84–86%, while the proportions of monounsaturated (MUFAs) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) increase. Notably, the PUFA/SFA ratio rises from 0.055 in untreated SBP to 0.12 in all fungal-treated SBP biomasses, reflecting an approximate doubling of PUFA and ω-fatty acid levels. MUFA levels increase from 2–3% to 4–5%. These changes suggest that fungal lipid accumulation and fatty acid profiles are influenced by strain-specific characteristics, growth parameters, and substrate composition, although SFA often remains a significant fraction of microbial lipid content [62,63].

The results of our study align with trends reported in the literature, which indicate that fungus-derived biomass typically contains a mixture of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. Under nutrient- or substrate-driven conditions, the relative proportion of unsaturated fatty acids (MUFA and PUFA) tends to increase compared to SFA [64]. Fungal strains that produce biomass rich in PUFAs and ω-fatty acids are particularly desirable for applications in the food, nutraceutical, and pharmaceutical industries [65,66]. This represents a nutritionally beneficial attribute, as higher proportions of PUFA have been associated with improved health-related lipid metabolism [67].

These changes are consistent with internationally recognised nutritional recommendations. FAO/WHO dietary lipid guidelines emphasise increasing PUFA intake, particularly ω-3 and ω-6-FA, while reducing SFA to improve lipid quality and lower cardiometabolic risk [54]. Ratios of PUFA/SFA above 0.45 are generally considered beneficial; although fungal-treated samples do not fully reach this benchmark, they demonstrate a marked improvement over unfermented SBP. The observed increase in MUFAs, especially ω-9, is also consistent with AHA and EFSA recommendations advocating the substitution of SFA with cis-MUFAs and PUFAs. Collectively, these shifts indicate that fungal fermentation generates a more nutritionally favourable lipid profile, with a higher proportion of essential unsaturated fatty acids and a reduced saturated fraction.

These findings demonstrate that fungal fermentation can effectively enrich agro-industrial by-products like sugar beet pulp with nutritionally valuable lipids, making them more suitable for applications in food or feed industries.

3.5. Nutritional Composition of Different SBP Fungal Biomasses

In this study, the SBP fungal biomass was produced through semi-solid fermentation (SmF) of the SBP flour using A. nidulans, R. arrhizus, and B. cinerea fungal strains. Fermentation with fungi significantly altered the chemical composition of SBP (Table 5). Protein content increased in all SBP fungal biomasses from 5.4% to 9–13%, with the highest enrichment observed in R. arrhizus SBP biomass (12.9 g/100 g d.w.), showing a 2.5-fold increase compared to SBP. Sugars decreased significantly, indicating their utilisation as a carbon source during fungal growth. Total dietary fibre remained at the same level, while the SDF/IDF ratio significantly decreased from 0.32 to 0.15–0.18, most notably for the R. arrhizus sample, which showed the highest proportion of SDF. Lignin content remained relatively stable.

Table 5.

The chemical composition (g/100 g d.w.) of SBP and SBP fungal biomasses.

The differences in protein levels among the fungal biomasses are consistent with known fungal-specific metabolic characteristics reported in the literature. Aspergillus nidulans is known for strong hydrolytic enzyme secretion and efficient nitrogen assimilation during growth on plant polysaccharides, resulting in higher cellular protein levels [68]. Also, the study by Ruslan et al. demonstrated Rhizopus oligosporus efficiently transforming vegetable waste into protein-rich biomass, increasing by 4.3-fold protein yield [69]. According to previous studies, B. cinerea typically exhibits slower growth and increased investment in cell-wall-associated polymers, such as β-glucans and chitin, which proportionally reduce intracellular protein content [70]. These patterns align with previously described nutrient-partitioning strategies in filamentous fungi, where carbon and nitrogen flow is differentially directed toward enzyme production versus structural polymer synthesis depending on species physiology and ecological adaptation [71].

Semi-solid fermentation with edible filamentous fungi, such as A. niger, R. arrhizus, and B. cinerea, improved the nutritional value of SBP material and converted it to a valuable product with potential for being utilised at least in the feed industry after toxicity evaluation.

3.6. Evaluation of the Antioxidant Capacities of SBP Fungal Biomass Protein Fractions from Controlled Digestion with Trypsin

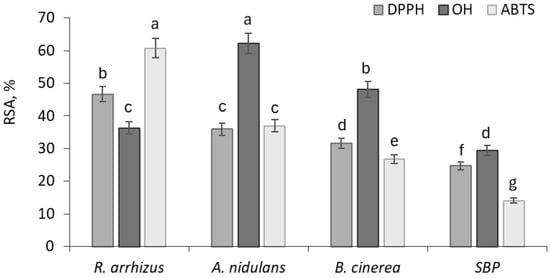

In our study, the <10 kDa peptide fractions obtained after controlled digestion of the US-SBP fungal biomass protein with trypsin were analysed for their antioxidant capacity using ABTS and DPPH radical-scavenging assays, as well as hydroxyl radical-scavenging measurements (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The DPPH, ABTS, and OH• radical-scavenging activities (RSA), corresponding to the <10 kDa peptide fractions from A. niger, R. arhizzus, and B. cinerea SBP biomass.

As shown in Figure 1, the scavenging of DPPH radical by <10 kDa peptide fractions of different SBP fungal biomasses ranged from 31.64% to 46.68%, which were equivalent to 203.85 μg TE/g and 319.87 μg TE/g SBP biomass dry powder, respectively. After fungal fermentation, the DPPH radical scavenging capacity of SBP increased by about 1.5–1.9 times, compared to untreated SBP peptide (Figure 1).

The ABTS•+ radical scavenging activity of analysed peptide fractions was measured in the range between 26.85% and 60.76%, which were equivalent to 721.63 μg TE/g and 1818.25 μg TE/g d.w., confirming an increase in ABTS•+ radical scavenging capacity by 1.9–4.3 times. In the case of hydroxyl radical scavenging activity, the levels ranged from 36.32% to 62.18%.

Based on the obtained results, R. arrhizus exhibited the highest ABTS radical-scavenging activity and a comparatively strong DPPH scavenging capacity, while its hydroxyl radical (•OH) scavenging activity was the lowest among the three fungal strains. A. nidulans showed the strongest •OH radical-scavenging activity overall, whereas its DPPH and ABTS activities were lower. B. cinerea demonstrated intermediate antioxidant activities, with •OH scavenging higher than its DPPH and ABTS values. In general, raw SBP peptides showed significantly (p < 0.05) lower antioxidant activity levels (24.67% DPPH radical scavenging, 14.08% ABTS radical scavenging, and 29.39% hydroxyl radical scavenging) (Figure 1), confirming the enhancing effect of fungal cultivation on antioxidant potential.

The higher antioxidant capacity observed in certain fungal strains may be related to the greater abundance of hydrophobic and aromatic amino acids in the peptides generated from their protein fractions [72,73]. Although non-peptidic compounds such as phenolics are expected to be largely removed during protein isolation and fractionation, minor non-peptidic components cannot be completely excluded.

3.7. Identification of Potential Bioactive Peptides in SBP Fungal Biomass Peptide Fractions

To specifically generate and investigate bioactive peptide sequences, a controlled proteolysis with trypsin was applied to the proteins extracted from SBP fungal biomasses. This targeted enzymatic treatment allows systematic cleavage of protein precursors and facilitates the production of peptide fragments with potential antioxidant activity. According to the peptidomic research, endogenous peptides in vivo are primarily formed due to physiological enzymatic or non-enzymatic breakdown, and other enzymatic gene-independent processes [74]. In general, bioactive peptides are inactive within their native parent protein conformation, when cleaved by proteolytic enzymes, these proteins can generate bioactive peptide fragments [74,75].

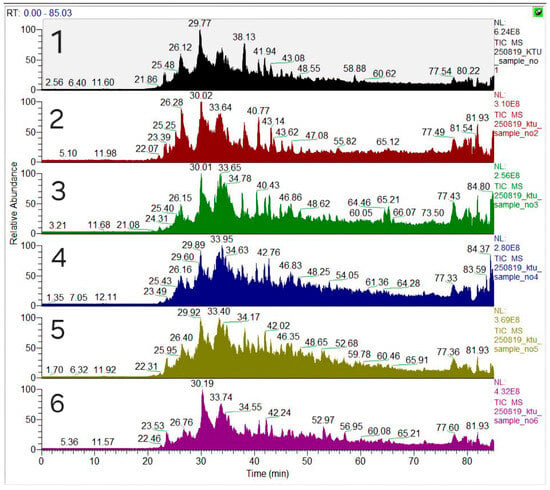

Chromatographic analysis of all SBP fungal biomass protein tryptic hydrolysates showed hundreds of plant-origin and fungal-origin peptides produced (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Base peaks-chromatograms (LC-MS/MS) for peptides of A. niger (samples no 1–2), R. arrhizus (samples no 3–4), and B. cinerea (samples no 5–6) fermented SBP biomass samples, treated with US and HT, respectively.

To evaluate the antioxidant potential of the peptides derived from SBP fungal biomass, the complete set more than 400 identified peptides was screened according to the MM < 2 kDa and the established molecular determinants of antioxidant activity, including the presence of hydrophobic (A, V, L, I, M, P) and aromatic (F, W, Y, H) amino acid residues, which promote radical interaction and electron transfer processes. Based on this criterion, a subset of peptides with the highest content of such residues was selected as the most promising bioactive candidates (Table 6).

Table 6.

Examples of fungal and plant origin common peptides identified in the three SBP fungal biomasses after controlled trypsin digestion.

The majority of peptides identified in this study may have originated from fungal structural and metabolic proteins rather than from plant-derived storage proteins within the A. nidulans and R. arrhizus peptide fractions (<10 kDa). This indicates that trypsin-mediated proteolysis primarily fragmented fungal biomass proteins accumulated during SBP fermentation. In contrast, in the B. cinerea peptide fraction, a greater proportion of peptides were found to be sugar-beet-derived. This observation suggests reduced fungal self-proteolysis and a comparatively higher release of plant-derived peptides in this system, which aligns with previous reports showing that fermentation and enzymatic hydrolysis can liberate peptides from plant storage proteins [73,76,77].

The peptide profiles obtained from A. nidulans-, R. arrhizus-, and B. cinerea-fermented SBP biomass reveal a structurally diverse range of AA sequences with potential antioxidant activity of low to high and strongly high capacity. Across all three fermented SBP biomasses, aromatic residues, particularly tyrosine (Y), tryptophan (W), phenylalanine (F), and histidine (H), were strongly represented, which are known to contribute to radical scavenging and antioxidant activity [76,78].

Among the identified peptides, those enriched in aromatic and hydrophilic residues exhibited particularly strong antioxidant potential. Specifically, Y(+43.01)HHTYPR, Y(+43.01)HPGYFGK, HAFGDQYR, ILAEEYGWDK, and A(+43.01)VVSQYGK displayed structural features associated with reactive oxygen species (ROS) neutralisation and redox modulation [79]. A recurring structural motif in these peptides is the presence of aromatic residues at either the N-terminus or within central regions of the sequence, which may enhance antioxidant activity [80].

Across the three fermentation systems, the peptides demonstrated favourable hydrophilicity, indicated by negative or moderately negative GRAVY values, supporting good aqueous solubility and effective ROS interactions. The combination of aromatic and hydrophilic residues suggests that these peptides may exert multiple bioactive functions, including antioxidant, metal-chelating, and potential anti-inflammatory effects [77,81]. For example, HAFGDQYR and ILAEEYGWDK integrate aromatic residues (Y, W, H) with acidic or basic hydrophilic residues (E, D, K, R, Q), facilitating ROS neutralisation and stabilisation of oxidative intermediates [79].

These findings align with established models of peptide-mediated antioxidant mechanisms, where N-terminal aromatic residues serve as primary radical scavengers, while internal hydrophilic residues contribute to proton transfer and metal-chelation pathways [82,83]. Therefore, the combination of aromatic amino acids and polar hydrophilic residues emerges as a predictive structural motif for antioxidative activity [83,84].

Additionally, hydrophobic residues such as Leu, Val, and Ile, present in several identified peptides, may enhance interactions with lipid bilayers, providing membrane protection and stabilising the peptide structure against enzymatic degradation. When these hydrophobic residues co-occur with aromatic amino acids and histidine, the peptides may efficiently function in both aqueous and lipid environments, strengthening their biological activity as free radical scavengers [78,85,86]. Moreover, post-translational modifications, such as acetylation or oxidation (+43.01 Da mass shifts), may further improve peptide solubility, structural stability, and redox reactivity under oxidative conditions [87].

3.8. SBP Fungal Biomass Technological and Morphological Properties

The analysis of the technological properties confirmed that all SBP substrate pretreatments considerably impacted the water retention and solubility of the resulting product (Table 7). Hydrothermal pretreatment of SBP substrate resulted in a higher WAI (6.57–7.62 g/g) and higher WSI values (1.16–1.26%) of the fermented SBP biomass powder, compared to control sample (5.12 g/g and 0.85%, respectively), indicating the partial depolymerisation of insoluble structural components and increased solubility possibly due to pectin solubilisation [88]. On the other hand, US treatment considerably increased WAI (7.23–9.04 g/g) and WSI (1.45–1.63%), indicating cavitation-mediated breakdown of the cell matrix, increased porosity, and opened hydrophobic and hydrophilic surface [89]. The untreated SBP showed the lowest absorption properties and solubility, indicating the substrate’s intrinsic hydration capacity.

Table 7.

Absorption and solubility properties of fermented SBP biomass powdered products.

These findings correspond to the work that other researchers have conducted. According to Li et al., the hydrothermal pretreatment of bamboo between 120 and 240 °C influenced a rise in crystallinity index (CrI) primarily linked to the elimination of hemicelluloses, rather than alterations in the cellulose crystalline structure or partial lignin removal [90], thus altering original substrate structure and increasing water holding capacity. It was also shown that ultrasound increases the water absorption by waves that are made up of alternating compression and rarefaction cycles that travel through solids, liquids, or gases, causing molecules to be displaced and shifted from their original positions, as shown by Pingret et al. [91]. After fungal fermentation, the water solubility of thermally pretreated SBP may decrease due to microbial utilisation of soluble carbohydrates and the accumulation of insoluble fungal biomass [92]. Similar findings were reported for thermochemically pretreated pulp, where pectin solubilisation was followed by the persistence of insoluble cellulose fractions [3].

In the case of oil absorption (Table 7), all pretreated, fermented, and freeze-dried SBP samples showed higher oil absorption capacity compared to the untreated substrate. The untreated SBP exhibited the lowest OAI value (3.75 g/g), reflecting its dense structure and limited availability of hydrophobic binding sites [89]. Hydrothermally pretreated samples showed a moderate increase in OAI, ranging from 7.76 g/g for A. nidulans and B. cinerea to 8.13 g/g for R. arrhizus. In contrast, ultrasonicated samples demonstrated the highest oil absorption, reaching up to 10.45 g/g for A. niger and, on average, 9.88 g/g for other strains. This increase is likely due to the development of a porous structure during US treatment and incorporation of fungal biomass rich in hydrophobic cell wall components, enhancing the affinity for oil binding [90].

High WAI and OAI values obtained by ultrasonication might have a special advantage, where swelling, viscosity, or water-holding and oil-holding capacity are a greater requirement, e.g., in texturising of food or moisture retention of feed [13,93]. Alternatively, higher dry matter retention after hydrothermal pretreatment might find a special use where structural integrity and nutrient concentration are of interest, e.g., where high-fibre feed is formulated or where a solid support is needed for a solid-supported fermentation system.

In summary, hydrothermal treatment and sonication of SBP can be potentially applied in the production of fungal protein to enhance fungal growth and biomass production by improving nutrient availability by breaking down the complex structure of SBP. SBP is a sustainable, economical source of carbon and nitrogen, and ultrasound acts as a “green” technology to increase nutrient release and cell permeability.

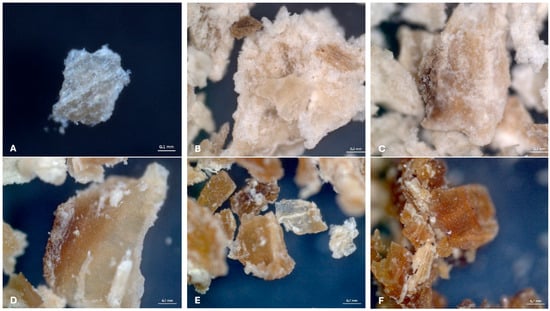

The morphological changes in SBP subjected to different pretreatments and fermentation were assessed under microscopic evaluation. Raw SBP particles (Figure 3A) appear compact and relatively homogenous. After ultrasonication (Figure 3B), the structure becomes more fragmented and porous, similar to what was previously observed in US-treated sugar-beet pectin, where scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed increased surface roughness, fragmentation, and irregular edges compared with native SBP [94].

Figure 3.

Microscopic evaluation (×97.5) of powdered samples of sugar beet pulp (SBP): untreated (A), ultrasonicated (B), hydrothermally treated (C), and fermented with A. nidulans CCF2912 (D), R. arrhizus CCF1502 (E), and B. cinerea CCF2361 (F).

Hydrothermal pretreatment (Figure 3C) results in a softened and slightly swollen morphology, which aligns with reports that thermal or hydrothermal processing can alter the compact structure of lignocellulosic biomass and make physical disruption (e.g., subsequent ultrasonication or enzymatic treatment) more efficient [95].

Following fermentation with filamentous fungi, such as A. nidulans (Figure 3D), R. arrhizus (Figure 3E), and B. cinerea (Figure 3F), the SBP structure becomes noticeably altered. These samples display an increased brittleness and disrupted microstructure that are consistent with the literature demonstrating that biological or mechanical–chemical pretreatments increase substrate accessibility by disrupting the cell wall matrix, thereby facilitating microbial or enzymatic degradation [29,96]. These observations highlight that both physical pretreatments and biological fermentation significantly changed SBP biomass functional properties, enhancing its functionality and potentially increasing its biotechnological applications.

4. Conclusions

The production of innovative products through fermentation using safe microscopic fungi is a promising approach to producing sustainable and valuable food/feed products. Ensuring the nutritional quality, safety, and accumulation of bioactive components in sugar-beet-pulp-based fungal biomass is essential to meet nutritional requirements and achieve the desired bio-functional properties.

The ultrasonication of sugar beet pulp at 70 °C temperature and semi-state fermentation (SmF) successfully improved the nutritional value of SBP biomass and converted it to a valuable protein-rich product with protein content up to 128 g/kg d.w. Hydrothermal treatment and sonication of SBP can be potentially applied in the production of fungal proteins to enhance fungal growth and protein production by improving nutrient availability by breaking down the complex structure of SBP. SBP is a sustainable, economical source of carbon and nitrogen, and ultrasound acts as a “green” technology to increase nutrient release and cell permeability.

In this study, the SmF processing was used to improve the quality of the SBP fungal biomass, increasing the content of the EAA. The increase in PUFAs, specifically α-linolenic acid, compared to the substrate also contributes to the increased nutritional value. The nucleic acid concentration was successfully reduced by applying additional sterilisation of SBP biomass at 90 °C for 30 min.

In this study, for the first time, the presence of bioactive peptides in fungal biomass derived from sugar processing by-products has been evaluated. Ultrafiltration of tryptic protein hydrolysates and subsequent measurement of antioxidant capacity revealed a pronounced accumulation of peptides with an MM of <2 kDa, possibly indicating medium to high antioxidant activity. Chromatographic peptide separation and amino acid sequence analyses identified peptides enriched in hydrophobic residues (Leu, Val, Ile) along with aromatic or imidazole-containing residues (Tyr, Trp, Phe, His), suggesting at least potential antioxidant effects. Among the fungi tested, R. arrhizus CCF1502 cultivated on US-treated sugar beet pulp (SBP) exhibited the highest biomass yield, peptide fraction antioxidant activity, and overall nutritional quality.

Both theoretical predictions and experimental results indicate that protein-rich SBP fungal biomass has strong potential as a source of functional feed and food ingredients, as well as dietary supplements enriched in bioactive components, making it a promising candidate for nutritional applications in food and feed. Future research should focus on the safety assessment of SBP biomass, including mycotoxin levels, further protein fractionation, and a comprehensive evaluation of bioactivities across different peptide fractions. Additionally, studies on the influence of fermentation conditions on bioactive peptide formation would help fully determine the nutritional value and functional potential of SBP-derived fungal biomass.

Author Contributions

Methodology, formal analysis, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, Z.G.; Conceptualisation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, supervision, resource management, D.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The data presented in this article is a part of Ph.D. work of the first author.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Department of Botany of Charles University (Prague, Czech Republic) for kindly providing fungal strains for the Ph.D. research purposes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Amino acids contents (mg/g d.w.) in untreated SBP and SBP fungal biomass after.

Table A1.

Amino acids contents (mg/g d.w.) in untreated SBP and SBP fungal biomass after.

| Amino Acid | SBP Fungal Biomass | SBP Biomass | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. arrhizus CCF1502 | A. niger CCF3264 | A. niger CCF3264 | F. solani CCF2967 | P. oxalicum CCF3438 | B. cinerea CCF2361 | ||

| Aspartic acid | 7.34 ± 0.45 | 5.62 ± 0.64 | 7.27 ± 0.40 | 5.34 ± 0.48 | 5.33 ± 0.41 | 7.42 ± 0.35 | 5.43 ± 0.10 |

| Glutamic acid | 7.6 ± 0.30 | 6.42 ± 0.48 | 8.50 ± 0.33 | 6.31 ± 0.46 | 6.38 ± 0.47 | 8.43 ± 0.31 | 6.15 ± 0.03 |

| Serine | 3.95 ± 0.16 | 3.34 ± 0.27 | 4.29 ± 0.32 | 3.34 ± 0.28 | 3.35 ± 0.26 | 4.47 ± 0.22 | 3.17 ± 0.05 |

| Histidine | 2.18 ± 0.21 | 1.82 ± 0.13 | 2.01 ± 0.19 | 1.83 ± 0.18 | 1.61 ± 0.12 | 2.00 ± 0.25 | 1.63 ± 0.03 |

| Glycine | 3.22 ± 0.13 | 2.76 ± 0.17 | 3.2 ± 0.26 | 2.81 ± 0.21 | 2.82 ± 0.20 | 3.68 ± 0.21 | 2.45 ± 0.01 |

| Threonine | 3.81 ± 0.21 | 3.18 ± 0.25 | 4.06 ± 0.31 | 3.21 ± 0.26 | 3.27 ± 0.25 | 4.22 ± 0.24 | 2.93 ± 0.02 |

| Arginine | 2.88 ± 0.12 | 2.49 ± 0.16 | 3.30 ± 0.20 | 2.49 ± 0.26 | 2.51 ± 0.18 | 3.33 ± 0.18 | 2.29 ± 0.02 |

| Alanine | 3.51 ± 0.18 | 3.08 ± 0.16 | 3.85 ± 0.20 | 3.06 ± 0.26 | 3.11 ± 0.23 | 4.04 ± 0.21 | 2.84 ± 0.01 |

| Tyrosine | 1.90 ± 0.12 | 1.03 ± 0.14 | 1.98 ± 0.17 | 1.18 ± 0.06 | 1.29 ± 0.27 | 2.21 ± 0.24 | 1.99 ± 0.26 |

| Methionine | 1.39 ± 0.14 | 1.37 ± 0.15 | 1.25 ± 0.14 | 1.07 ± 0.08 | 1.71 ± 0.23 | 2.26 ± 0.30 | 1.60 ± 0.01 |

| Valine | 2.87 ± 0.21 | 1.07 ± 0.12 | 3.11 ± 0.24 | 1.63 ± 0.07 | 1.92 ± 0.12 | 3.64 ± 0.13 | 2.89 ± 0.02 |

| Cysteine | 0.46 ± 0.04 | 0.71 ± 0.04 | 0.50 ± 0.05 | 0.40 ± 0.21 | 0.74 ± 0.07 | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 0.18 ± 0.06 |

| Phenylalanine | 2.46 ± 0.12 | 1.73 ± 0.04 | 2.62 ± 0.12 | 1.83 ± 0.34 | 1.89 ± 0.23 | 2.90 ± 0.18 | 2.28 ± 0.06 |

| Isoleucine | 1.66 ± 0.0.09 | 1.11 ± 0.03 | 1.85 ± 0.14 | 1.3 ± 0.06 | 1.35 ± 0.21 | 2.21 ± 0.13 | 2.01 ± 0.04 |

| Leucine | 4.13 ± 0.18 | 3.37 ± 0.22 | 4.65 ± 0.34 | 3.72 ± 0.41 | 3.50 ± 0.21 | 5.23 ± 0.22 | 3.92 ± 0.03 |

| Lysine | 5.67 ± 0.51 | 4.93 ± 0.24 | 5.71 ± 0.28 | 5.33 ± 0.29 | 5.08 ± 0.43 | 6.40 ± 0.41 | 5.21 ± 0.09 |

| Proline | 1.87 ± 0.09 | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 3.72 ± 0.16 | 3.98 ± 0.15 | 3.15 ± 0.11 | 3.48 ± 0.23 | 5.33 ± 0.28 |

| Total AA | 56.90 c | 44.52 f | 61.87 b | 48.83 e | 49.01 e | 66.60 a | 52.30 d |

AA—amino acids; Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Different superscript letters in the same row represent significant differences at p < 0.05.

Appendix B

Figure A1.

Protein contents (Kjeldahl) produced by tested fungal strains in ultrasonicated (US; 40 min; 70 °C) and hydrothermally treated (HT; 30 min; 121 °C) SBP media during a 72–216 h solid-state fermentation period.

References

- Ning, P.; Yang, G.; Hu, L.; Sun, J.; Shi, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J. Recent advances in the valorization of plant biomass. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2021, 14, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nap, J.P.; de Ruijter, F.J.; van Es, D.S.; van der Meer, I.M. The case of sugar beet in Europe: A review of the challenges for a traditional food crop on the verge of climate change and circular agriculture. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 24, 102343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlowska, J.; Cieciura, W.; Borowski, S.; Dudkiewicz, M.; Binczarski, M.; Witonska, I.; Otlewska, A.; Kregiel, D. Simultaneous Saccharification and Fermentation of Sugar Beet Pulp with Mixed Bacterial Cultures for Lactic Acid and Propylene Glycol Production. Molecules 2016, 21, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yankov, D. Fermentative lactic acid production from lignocellulosic feedstocks: From source to purified production. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 823005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbacz, K.; Wawrzykowski, J.; Czelej, M.; Czernecki, T.; Waśko, A. Recent trends in the application of Oilseed-Derived protein hydrolysates as functional foods. Foods 2023, 12, 3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisboa, H.M.; Nascimento, A.; Arruda, A.; Sarinho, A.; Lima, J.; Batista, L.; Dantas, M.F.; Andrade, R. Unlocking the potential of Insect-Based Proteins: Sustainable solutions for global food security and nutrition. Foods 2024, 13, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Zannini, E. Recovery, isolation, and characterization of food proteins. Foods 2022, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.; Lins, C.I.M.; Santos, E.R.D.; Silva, M.C.F.; Campos-Takaki, G.M. Microbial Enhance of Chitosan Production by Rhizopus arrhizus Using Agroindustrial Substrates. Molecules 2012, 17, 4904–4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Galand, S.; Asensio-Grau, A.; Calvo-Lerma, J. The potential of fermentation on nutritional and technological improvement of cereal and legume flours: A review. Food Res. Int. 2021, 145, 110398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havemeier, S.; Erickson, J.; Slavin, J. Dietary guidance for pulses: The challenge and opportunity to be part of both the vegetable and protein food groups. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1392, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herreman, L.; Nommensen, P.; Pennings, B. Comprehensive overview of the quality of plant- and animal-sourced proteins based on the digestible indispensable amino acid score. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 5379–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Juhász, A.; Bose, U.; Terefe, N.S.; Colgrave, M.L. Research trends in production, separation, and identification of bioactive peptides from fungi: A critical review. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 119, 106343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptak, M.; Skowrońska, A.; Pińkowska, H.; Krzywonos, M. Sugar beet pulp in the context of developing the concept of circular bioeconomy. Energies 2021, 15, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajić, B.; Vučurović, D.; Vasić, Đ.; Jevtić-Mučibabić, R.; Dodić, S. Biotechnological Production of Sustainable Microbial Proteins from Agro-Industrial Residues and By-Products. Foods 2022, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadar, C.G.; Fletcher, A.; De Almeida Moreira, B.R.; Hine, D.; Yadav, S. Waste to protein: A systematic review of a century of advancement in microbial fermentation of agro-industrial byproducts. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filho, P.F.S.; Nair, R.B.; Andersson, D.; Lennartsson, P.R.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Vegan-mycoprotein concentrate from pea-processing industry byproduct using edible filamentous fungi. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2018, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelechi, M.; Ukaegbu-Obi, K.M. Single cell protein: A resort to global protein challenge and waste management. J. Microbiol. Microb. Technol. 2016, 1, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, M.K.; Kumar, V.; Hellwig, C.; Wikandari, R.; Harirchi, S.; Sar, T.; Wainaina, S.; Sindhu, R.; Binod, P.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Filamentous fungi for sustainable vegan food production systems within a circular economy: Present status and future prospects. Food Res. Int. 2022, 164, 112318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajoka, M.I.; Ahmed, S.; Hashmi, A.S.; Athar, M. Production of microbial biomass protein from mixed substrates by sequential culture fermentation of Candida utilis and Brevibacterium lactofermentum. Ann. Microbiol. 2011, 62, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, F.; Foster, G.D.; Bailey, A.M. Natural products from filamentous fungi and production by heterologous expression. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousta, N.; Hellwig, C.; Wainaina, S.; Lukitawesa, L.; Agnihotri, S.; Rousta, K.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Filamentous Fungus Aspergillus oryzae for Food: From Submerged Cultivation to Fungal Burgers and Their Sensory Evaluation—A Pilot Study. Foods 2021, 10, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.A.; Lennartsson, P.R.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Production of ethanol and biomass from thin stillage using food-grade Zygomycetes and Ascomycetes filamentous fungi. Energies 2014, 7, 4199–4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchami, M.; Ferreira, J.; Taherzadeh, M. Brewing process development by integration of edible filamentous fungi to upgrade the quality of brewer’s spent grain (BSG). BioResour 2021, 16, 1686–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnigan, T.J.; Wall, B.T.; Wilde, P.J.; Stephens, F.B.; Taylor, S.L.; Freedman, M.R. Mycoprotein: The Future of Nutritious Nonmeat Protein, A symposium review. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, nzz021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, Q.; Qiu, C.; Su, G. Effects of solid-state fermentation and proteolytic hydrolysis on defatted soybean meal. LWT 2018, 97, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleria, H.A.R. Valorization of food waste to produce value-added products based on its bioactive compounds. Processes 2023, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.D.; Beverly, R.L.; Qu, Y.; Dallas, D.C. Milk bioactive peptide database: A comprehensive database of milk protein-derived bioactive peptides and novel visualization. Food Chem. 2017, 232, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toldrá, F.; Reig, M.; Aristoy, M.C.; Mora, L. Generation of bioactive peptides during food processing. Food Chem. 2018, 267, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaizauskaite, Z.; Zvirdauskiene, R.; Svazas, M.; Basinskiene, L.; Zadeike, D. Optimised degradation of lignocelluloses by edible filamentous fungi for the efficient biorefinery of sugar beet pulp. Polymers 2024, 16, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aberkane, A. Comparative evaluation of two different methods of inoculum preparation for antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002, 50, 719–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 17th ed.; The Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sönnichsen, M.; Müller, B.W. A rapid and quantitative method for total fatty acid analysis of fungi and other biological samples. Lipids 1999, 34, 1347–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Mugunthan, M. Evaluation of three DNA extraction methods from fungal cultures. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2018, 74, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UniProt Consortium. UniProt: The Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D523–D531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, K.; Reddy, N.; Sunna, A. Exploring the Potential of Bioactive Peptides: From Natural Sources to Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Gao, J.; Xue, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, X. Purification and identification of antioxidant peptides from chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) albumin hydrolysates. LWT 2013, 50, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, L.; Wang, L.; Qian, H.; Qi, X. In vitro and in vivo antioxidant activity of polyphenols extracted from black highland barley. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Morishima, T.; Handa, A.; Tsukagoshi, H.; Kato, M.; Shimizu, M. Biochemical characterization of a pectate lyase AnPL9 from Aspergillus nidulans. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 5627–5643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, T.; Zhang, K.; Shi, H.; Zhang, L.; Zou, G.; Sharon, A. Botrytis cinerea transcription factor BcXyr1 regulates (hemi-) cellulase production and fungal virulence. Msystems 2022, 7, e01042-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjeh, E.; Khodaei, S.M.; Barzegar, M.; Pirsa, S.; Sani, I.K.; Rahati, S.; Mohammadi, F. Phenolic compounds of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.): Separation method, chemical characterization, and biological properties. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 4238–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadollahzadeh, M.; Ghasemian, A.; Saraeia, A.; Resalati, H.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Production of fungal biomass protein by filamentous fungi cultivation on liquid waste streams from pulping process. BioResources 2018, 13, 5013–5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, I.; Coutinho, P.M.; Schols, H.A.; Gerlach, J.P.; Henrissat, B.; De Vries, R.P. Degradation of different pectins by fungi: Correlations and contrasts between the pectinolytic enzyme sets identified in genomes and the growth on pectins of different origin. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaworska, G.; Szarek, N.; Hanus, P. Effect of celeriac pulp maceration by Rhizopus sp. pectinase on juice quality. Molecules 2022, 27, 8610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pánek, M.; Vlková, T.; Michalová, T.; Borovička, J.; Tedersoo, L.; Adamczyk, B.; Baldrian, P.; Lopéz-Mondéjar, R. Variation of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus content in fungi reflects their ecology and phylogeny. Front Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1379825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lonardo, D.P.; van der Wal, A.; Harkes, P.; de Boer, W. Effect of nitrogen on fungal growth efficiency. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2020, 154, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccaron, A.Z.; Stergiopoulos, I. The dynamics of fungal genome organization and its impact on host adaptation and antifungal resistance. J. Genet. Genom. 2025, 52, 628–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brink, J.; de Vries, R.P. Fungal enzyme sets for plant polysaccharide degradation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 91, 1477–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Qiao, K.; Xiong, J.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Y. Nutritional values and bio-functional properties of fungal proteins: Applications in foods as a sustainable source. Foods 2023, 12, 4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukreti, N.; Kumar, P.; Kataria, R. Sustainable biotransformation of lignocellulosic biomass to microbial enzymes: An overview and update. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.L.; Kubo, M.T.K.; Caetano-Silva, M.E.; Augusto, P.E.D. Ultrasound processing of fruits and vegetables, structural modification and impact on nutrient and bioactive compounds: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 4376–4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, C. Effect of ultrasonic pretreatment on fermentation performance and quality of fermented hawthorn pulp by lactic acid bacteria. Food Chem. 2024, 446, 138774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Lv, Z.-W.; Rao, J.; Tian, R.; Sun, S.-N.; Peng, F. Effects of hydrothermal pretreatment on the dissolution and structural evolution of hemicelluloses and lignin: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 281, 119050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitzen, S.; Vogel, M.; Steffens, M.; Zapf, T.; Müller, C.E.; Brandl, M. Quantification of Degradation Products Formed during Heat Sterilization of Glucose Solutions by LC-MS/MS: Impact of Autoclaving Temperature and Duration on Degradation. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leser, S. The 2013 FAO report on dietary protein quality evaluation in human nutrition: Recommendations and implications. Nutr. Bull. 2013, 38, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M.; Zafar, M.H.; Aqib, A.I.; Saeed, M.; Farag, M.R.; Alagawany, M. Single cell protein: Sources, mechanism of production, nutritional value and its uses in aquaculture nutrition. Aquaculture 2021, 531, 735885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Byun, S.H.; Lee, B.M. Effects of chemical carcinogens and physicochemical factors on the UV spectrophotometric determination of DNA. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 2005, 68, 2081–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratosin, B.C.; Darjan, S.; Vodnar, D.C. Single Cell Protein: A Potential Substitute in Human and Animal Nutrition. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, J.; Brightwell, G. Safety of alternative proteins: Technological, environmental and regulatory aspects of cultured meat, plant-based meat, insect protein and single-cell proteins. Foods 2021, 10, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]