Abstract

The aim of this work is to implement decision tree classifiers (DTCs) capable of distinguishing bee honey by geographical origin. The case study focuses on honeys from the lowland and highland regions of Chiriquí, Panama. Characterization was conducted by analyzing their typical physicochemical and aromatic profiles using AOAC, IHC, and e-Nose methodologies, respectively. Data mining provided insights into the most relevant features, enabling the reduction of an otherwise extensive and resource-intensive dataset. The critical markers identified include reducing sugars, ash, antioxidant capacity, HMF, as well as aromatic, aliphatic, hydrocarbon, and sulfur compounds. This simplified set of features produced an intuitive classification scheme, achieving up to 86% accuracy. This proof-of-concept demonstrates that interpretable models can effectively leverage easily measurable characteristics for regional differentiation, offering a valuable tool for traceability in the Panamanian honey industry.

1. Introduction

Bee honeys exhibit significant variations in composition due to the relationship between botanical, physico-chemical, and environmental factors. The diverse flora characteristic of tropical regions provides bees with a wide range of nectar sources, directly influencing honey’s flavor profile and chemical makeup. Physico-chemical factors, such as temperature and humidity, affect nectar composition and the processing fashion carry out by bees. Environmental conditions, including soil type, altitude, and rainfall, impact plant growth and thus indirectly affect nectar availability and quality.

Honey is commonly classified by blossom type, honeydew source, chemical composition, and geographical origin [1]. This work focuses on exploring how these factors contribute to the unique characteristics of Panamanian honeys. Panama’s diverse microclimates, resulting from its steep topography and creates distinct botanical landscapes that directly impact honey composition [2,3]. The unique flavors and aromatic compounds developed in these honeys contribute to their high market acceptance and often result in premium pricing. Consequently, classification algorithms play a critical role in this process by enabling the accurate identification and grouping of honey based on their Designation of Origin [4,5].

Acknowledging the need for such tools, several approaches have been proposed for the discrimination of honey in the literature [6], Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is among the most popular of them [7,8,9]. However, linear PCA itself is not a classification algorithm, but it can be very useful in preparing data for classification tasks. To tackle the honey classification, it seems reasonable to ask a series of questions, with each subsequent question tailored to the answer of the previous one. This hierarchical structure not only enhances efficiency but also improves the interpretability of the classification model [10]. By tailoring each question to the specific characteristics of the previous response, DTCs can accurately identify the origin and potential crystallization behavior of honey samples, making them a robust choice for this task.

This research work is structured as follows. Firstly, an overview of the problem statement is presented, highlighting the challenges associated with classifying honey samples by origin. Secondly, the experimental component of this study is described and how the typical parameters are measured using physico-chemical and e-Nose analyses. Then, it addresses a statistical learning discussion on how the critical markers are chosen and used for the construction of the DTCs. Finally, the validation of the resulting models.

2. Problem Statement

The classification of honey by its geographical origin represents significant challenges in food science. As reported in the literature [8,11] the task is complicated by the inherent variability in physico-chemical and e-Nose measured features, often characterized by outliers, non-linearity, and noise. Also, some features exhibit overlapping and dominance over others. These attributes do not normally show a clear segregation within the boundary regions [12].

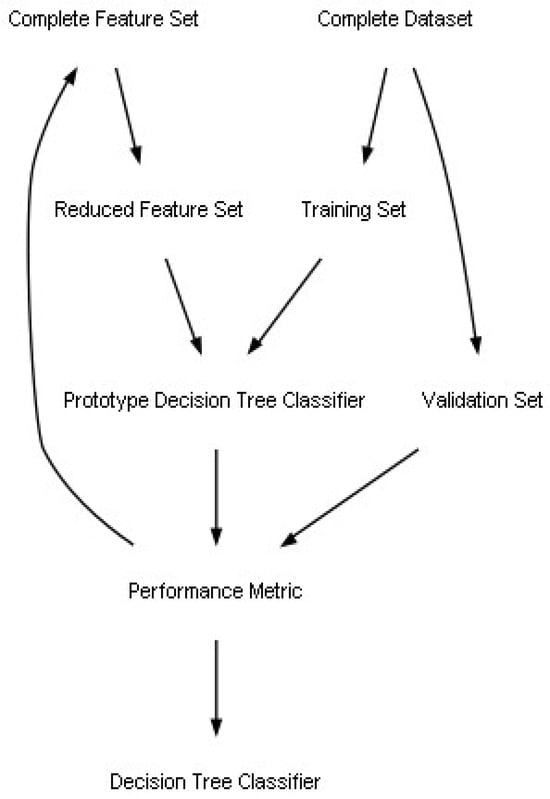

The targets of this work are to construct decision tree classifiers (DTCs) capable of discriminating honey by origin (Figure 1). The first target involves partitioning the complete dataset into training and validation sets, identifying a reduced set of relevant features, and establishing a suitable performance metric to evaluate the merits of the classification model. The second target implies the observation of the bee honeys over a period of 3 months.

Figure 1.

Iterative construction of the honeybee DTCs.

This research makes a significant contribution to creating new knowledge in the field by providing a classification model, contributing directly to improved quality control, traceability, and authenticity verification systems within the honey industry, benefiting producers, consumers, and regulators. This predictive understanding also opens new avenues for research into the manipulation of honey composition to control physical properties, ultimately enhancing the value and market appeal of this natural product.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Collections

A total of 22 sampling locations of multifloral honey from Apis mellifera bees were harvested directly from beekeepers during the months of February to April 2023 in two different zones (Lowland Highland) of Chiriquí province, Republic of Panama (Figure 2). Approximately 300 g of honey samples were collected directly from sealed honey pots of each bee colony and stored at room temperature in the dark until use.

Figure 2.

Geographical distribution of the sampled honeys in Chiriquí Province.

Apiculture in Panama is strongly determined by its climatic and geographic conditions. As a tropical country, it consistently exhibits elevated temperatures and humidity which is ideal for the growth of nectar-producing plants and for the activity of honeybees. Furthermore, Panama’s position as a narrow and steep land bridge connecting North and South America plays a significant role in shaping the botanical diversity of the regions, which in turn influences the composition of the honey produced.

The annual cycle is divided into two key seasons: the rainy season (May to November) provides the necessary rainfall for vegetation development and flowering. Following this, the dry season (December to April) with more sun and heat, allows the bees to collect and concentrate nectar. The samples analyzed in this work were exclusively collected during this dry season period. The variety of microclimates, formed due to differences in altitude, enables beekeepers to strategically select the best areas for their hives, thus ensuring a constat supply of resources and optimizing the final quality of the apicultural product [13].

- Sampling Logistics

To fully address the distribution of the samples and rule out seasonal mix-up, the exact sampling logistics are detailed in Table 1. All samples were collected during the peak dry season, ensuring a consistent climatic backdrop. The sampling campaign was executed concurrently across both macro-zones (Lowland and Highland) within the established dry season of Panama. Each of these zones was further divided into sub-zones (LL-1, LL-2, LL-3, and HL-1, HL-2, HL-3) reflecting local vegetation types and seasonal flowering patterns. Therefore, collapsing the 22 sampling sites into two main zones, further stratified into sub-zones makes the hierarchy clear and journal-appropriate.

Table 1.

Summary of the sampling distribution by geographical origin and date.

The Lowland zone is characterized by a tropical dry to moist forest, featuring dominant floral sources such as common weeds, palms, and specific tree species. In contrast, the Highland zone experiences lower temperatures, higher rainfall, and frequent cloud cover, supporting montane cloud forests and sub-páramo vegetation, where the predominant nectar sources shift to citrus, coffee, and laurel, which serve as key nectar source. This distinct botanical and climatic divergence results in honey with fundamentally different physicochemical and aromatic profiles [14].

3.2. Physico-Chemical Analysis

Physico-chemical analysis involves water content, pH, ash, electrical conductivity, diastase, HMF, phenols, antioxidant capacity, proline, glucose, fructose and reduced sugar (Table 2). Each sample was analyzed in two replicates, following AOAC methods [15], Harmonized Methods of the European Commission for honey (IHC) [16], and other authors [17,18].

Table 2.

Methods of references employed.

3.3. Instrumental Sensory Analysis—Aromatic Profile with Electronic Nose

The aromatic profile was measured following the conditions described in the literature [5] using a portable electronic nose (Airsense Analytics GmbH PEN3, Schwerin, Germany). For sample treatment, 3 g of honey was weighed in 20 mL glass vials and heated at 40 °C for 20 min in the oven, then the vial was attached to the e-Nose connection to obtain its respective aromatic profile. At the end of the measurements, the data were exported to the Win-Muster (v.1.6.x) software and subjected to the determination of the mean differential coefficient value (mcdv), considered as a distinctive value of the profile of each sensor and each of the samples.

4. Statistical Analysis

To gain insights of the relationship and structure between features in the complete experimental dataset, the task begins by conducting an exploratory data analysis. Initially, the data is segregated into lowland and highland, and for each sub-region, the features are characterized by their mean and standard deviation. This provides a foundational understanding of the feature distributions across these distinct geographical origins. Following this, an exploratory data analysis is performed, which involves detecting the main characteristics of the data through the inspection of scatter plots in 2D and histograms. This helps to identify clusters, and outliers within the data that will guide the subsequent construction of the DTCs. The development of DTCs for honeybee discrimination by geographical origin, involves the use of the data mining paradigm for feature discovery. Then the complete experimental dataset is normalized and divided using a bootstrapping algorithm into training and validation sets with a 70% to 30% split respectively. It follows the use of a Random Tree algorithm (RTA) that builds a prototype DTC which is constrained to be not deeper than 3 levels. The RTA is implemented using the Random Forest Classifier function library in the Scikit-learn 1.3.0 Package for Python 3.11.4.

4.1. Feature Discovery for Honeybee from Panama Classification

This methodology involves the gathering, and transformation of the bee honey data for the two-geographical regions. Thus, the set of characterization data is made up of 22 features which are split in physico-chemicals (16) and e-Nose (6). The magnitude order for typical experimental figures varies, therefore a normalization of data to a comparable range [0, 1] is carried out. This re-scaling helps the visualization and numerical analysis of the gathered data. The data cleaning was not performed, and the outliers were allowed to validate the robustness of the proposed DTCs discussed in the next section. To gain an insight of the data that we are dealing with, histograms and scatter plots between some typical physico-chemical and e-Nose features are depicted in the following sections.

4.2. Decision Tree Classifiers

A Decision Tree Classifier (DTC) is a machine learning model that, in this context, would learn a set of “if-then-else” rules from the honey data to classify a new sample as either Lowland (LL) or Highland (HL). It works by creating a flowchart-like structure, where each internal node represents a “question” about a honey’s features, each branch represents the answer to that question, and each leaf node at the end represents a final classification (LL or HL).

This research delves into the application of DTCs, exploring techniques to harness their power and minimize their shortcomings. These classifiers can handle various clustering, outliers, and high variance scenarios observed in bee honey features. They assist in diagnosing the origin of honey based on their chemical profile and VOCs. This approach employs a top-down recursive partitioning strategy, splitting data at each node based on the feature that best maximizes the split criterion (minimizing Gini Impurity). Randomizing features ensures that no single feature dominates the splits, which is particularly useful in datasets with strong but redundant features. Then, by introducing randomness, DTCs are less likely to memorize the training data and avoid overfitting.

4.2.1. DTC Based-On Physico-Chemical Features

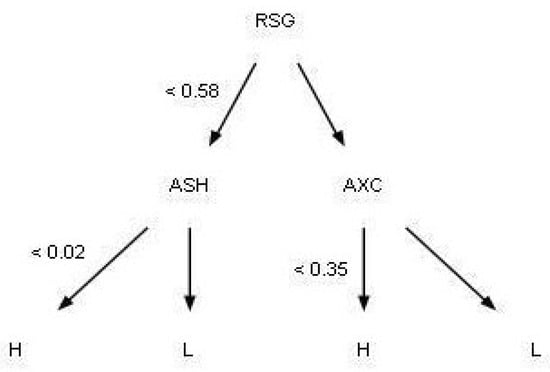

The classification of honeys depending on their origin for lowland and highland is achievable in practical terms using DTCs. The nodes in the decision trees are a reduced set of critical physico-chemical parameters with the necessary information for the classification algorithm. The chosen subset maximizes the classification score of the validation set. The process of building a DTC (Figure 3) is as follows:

- First Layer: Root Node.

The primary goal of the “root node” is to start with the feature that best separates the LL honeys from the HL honeys. For instance, the most informative parameter based-on the physico-chemical is RSG.

- Conditional Branching: Is the value of RSG below 0.58?

Note that this threshold value is computed by minimizing a Gini Index that measures the impurity of a dataset.

- If “yes”: Is the value of ASH below a certain threshold?

- If ASH < 0.02 then the honey sample is likely HL else LL.

- If “no”: Is the value of AXC below a certain threshold?

- If AXC < 0.35 then the honey sample is likely HL else LL.

After the initial split, the tree will ask further questions to refine the classification within each subgroup. This is where it would use the carefully curated features mentioned above. This hierarchical, interpretable structure, utilizing RSG, ASH, and AXC as critical features, is a key advantage of the DTC approach for this application.

Figure 3.

DTC based-on physico-chemical features. Classification score of 86%.

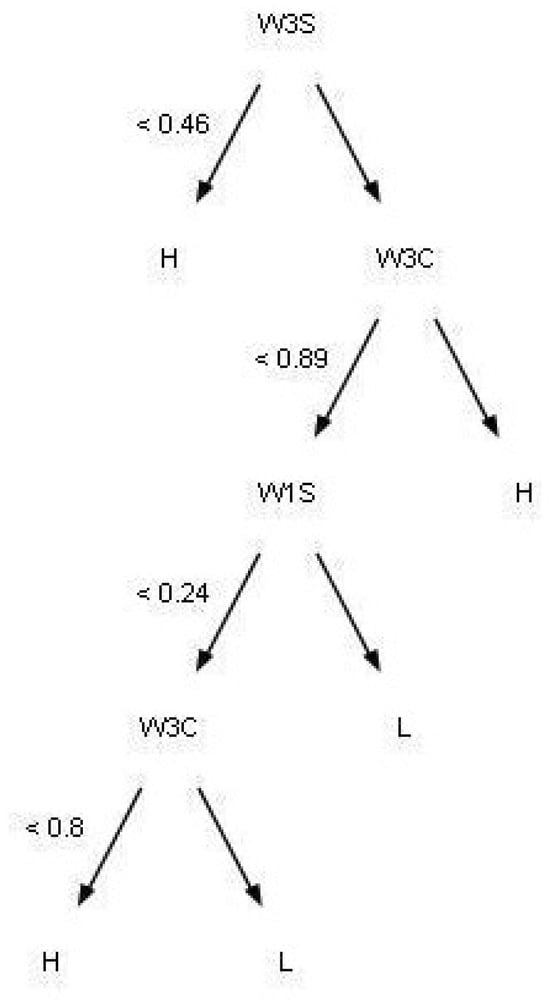

4.2.2. DTC Based-On e-Nose Features

The e-Nose presents a low cost, efficient and user-friendly system for the detection of multiple volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in honey samples. The e-Nose assembles the characteristic VOCs in up to ten kinds of features, however for this study only six of them were selected. These are labeled as follows: W3C, W5C, W1S, W1W, W2S and W3S. Each feature is alike a built-in Principal Component (PC) already given as a composite measurement. The DTC for the e-Nose depicted in Figure 4, performs a classification score of 86%. For this case, the same classification power is depicted in Figure 3. Therefore, the e-Nose could be a suitable replacement for the conventional physico-chemical analysis.

Figure 4.

DTC based-on e-Nose features. Classification score of 86%.

During the production of VOCs by means of thermic and enzymatic decomposition, short-chain hydrocarbons (W1S) can be formed because of the breakdown of larger molecules like sugars (RSG). It also produces short-chain aliphatic compounds (W3S) and others that contribute to the aroma (W3C) of honey. Since ash (ASH) is directly correlated with the mineral composition, the formation of VOCs like aldehydes, ketones, esters and furans are formed through the interaction with sugars and organic acids. Thus, there is a fundamental similarity between both decision trees.

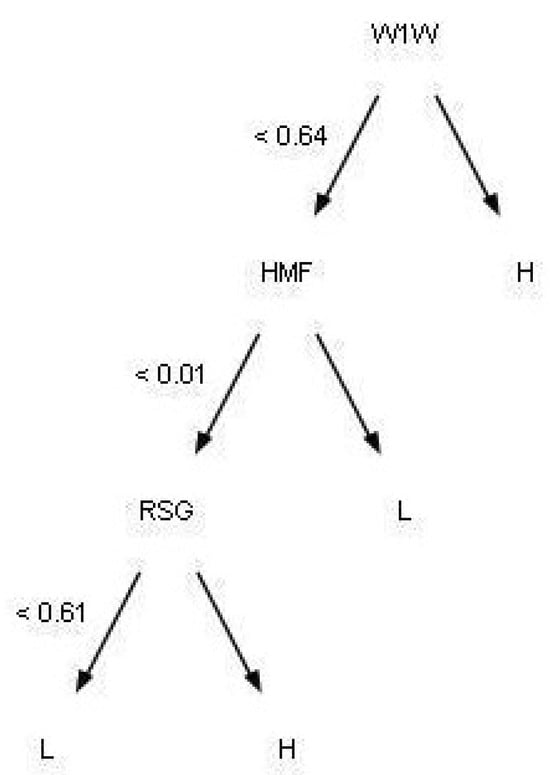

4.2.3. DTC Based-On Hybrid Features

For sake of completeness, a hybrid set of physico-chemical and e-Nose features (W1W, HMF, and RSG) was used to train a decision tree (Figure 5), achieving a 90% classification score. While this feature set is commonly used for honey quality discrimination, the combination of both approaches resulted in 4% enhancement in the classification that may be meaningful in some applications.

Figure 5.

DTC based-on hybrid features. Classification score of 90%.

5. Results

The physico-chemical characterization of honeys collected across the Chiriquí Province is summarized in Table 3, with segregation into lowland (LL, 5–750 m) and highland (HL, 940–1500 m) sub-zones. The water content (WTR) in LL honeys generally showed slightly higher water content, consistent with warmer, more humid lowland conditions. Sugars (GLC, FRC, RSG) both zones complied with Codex Alimentarius standards, but HL honeys tended toward higher reducing sugars, reflecting floral sources at altitude. Minerals (ASH, CVT): HL honeys exhibited higher ash and conductivity, indicating stronger soil–nectar mineral transfer in montane ecosystems. Phenolics (TPH): HL honeys clustered toward higher antioxidant content, consistent with diverse montane flora. These differences suggest that altitude influences nectar chemistry, though overlapping between categories remains substantial.

Table 3.

Summary of physico-chemical features of honeys from the Chiriquí Province, Panama.

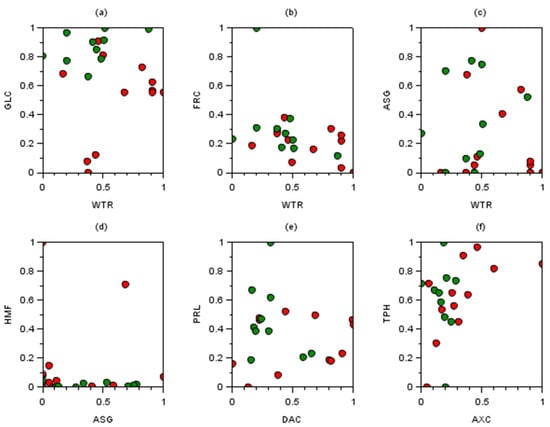

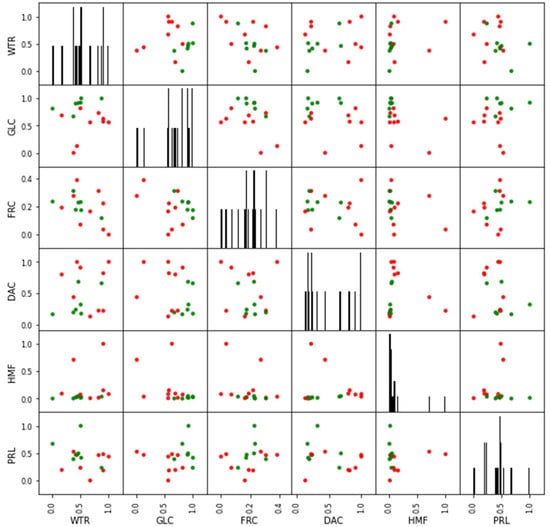

Figure 6 presents comparisons of selected physico-chemical features. WTR–GLC/WTR–FRC: The overlapping distributions indicate that water content and sugar ratios are not sufficient for clear discrimination. Physically, this reflects the fact that nectar dilution and sugar composition are strongly influenced by bee processing rather than geography alone. WTR–ASG/ASG–HMF: Highland honeys show lower apparent sucrose and HMF, suggesting fresher samples with less thermal degradation. DAC–PRL: Highland honeys exhibit higher enzyme activity and proline, pointing to stronger protein content and freshness. AXC–TPH: Highland honeys cluster toward higher phenolic content, reflecting antioxidant-rich flora.

Figure 6.

Scatter plots of the physico-chemical features for lowland (red dot; 5–750 m) and highland (green dot; 940–1500 m). Decision Boundaries may not be clearly defined. (a) WTR-GLC; (b) WTR-FRC; (c) WTR-ASG; (d) ASG-HMF; (e) DAC-PRL; (f) AXC-TPH.

These distributions reveal correlated biochemical processes (e.g., enzyme activity vs. proline) but also highlight that natural variability blurs decision boundaries. Because bulk physico-chemical features showed substantial overlap, we next examined volatile profiles using the e-Nose, which are more altitude-sensitive.

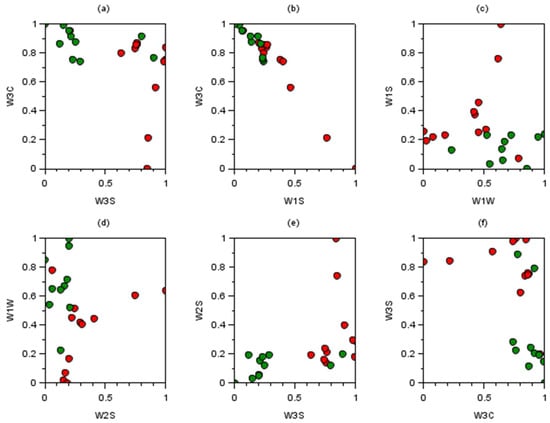

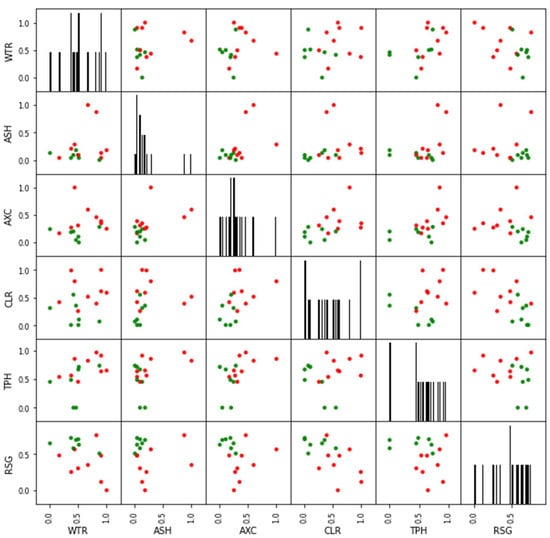

Figure 7 shows correlations among the e-Nose features. LL honeys cluster with stronger W3C responses, while HL honeys show higher W1W and W3S signals. Physically, this reflects volatile compound differences: montane flora produces distinct aromatic profiles, captured by orthogonal sensor responses.

Figure 7.

Scatter plots of the e-Nose features for lowland (red dot; 5–750 m) and highland (green dot; 940–1500 m). Decision Boundaries may not be clearly defined. (a) W3S–W3C, (b) W1S–W3C, (c) W1W–W1S, (d) W2S–W1W, (e) W3S–W2S, (f) W3C–W3S.

The e-Nose detects volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that are more altitude-dependent than bulk physico-chemical parameters, suggesting stronger discriminatory power.

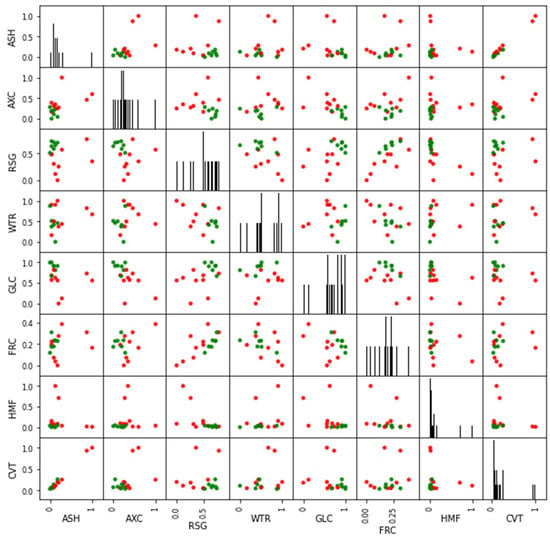

Figure 8 illustrates key correlations of typical physico-chemical features. ASH–CVT: The linear correlation reflects ionic conductivity as a direct function of mineral content. This is a physical property of dissolved salts in honey. FRC–GLC: Since FRC is derived from RSG–GLC, both follow similar trends with a bias. No single feature alone provides clear separation. Orthogonality among features is required to minimize error. These correlations highlight fundamental chemical relationships (e.g., conductivity and mineral ions) but also show that natural overlap limits classification accuracy.

Figure 8.

Histograms and scatter plots of typical physico-chemical features. Two-zone geographical categories, lowland (red dot; 5–750 m) and highland (green dot; 940–1500 m). ASH and CVT present a highly linear correlation. Since FRC is calculated out the subtraction between RSG and GLC, then they follow the same behavior plus a bias. The chosen set should be as orthogonal as possible. Also, that not a single feature by itself, serves unambiguously to classify between the two categories. Therefore, there is a trade-off between the categories to make the classification error the smallest possible.

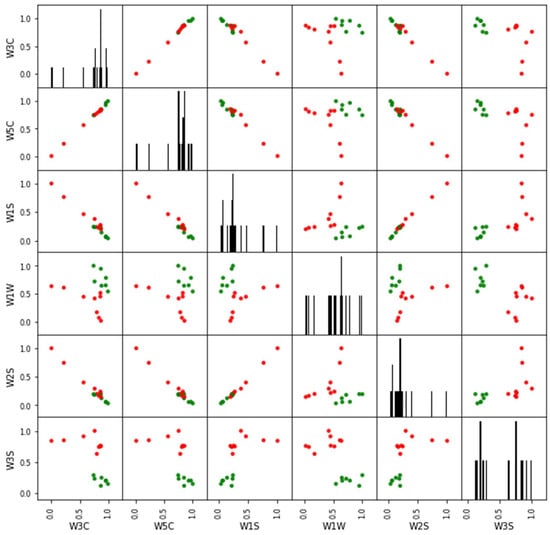

While physico-chemical correlations highlight fundamental chemistry, sensor-based volatile analysis provides stronger separation, as shown in Figure 9. It demonstrates clear distinctions across e-Nose sensors. W3S and W1W form an orthogonal base, capturing independent volatile information. Physically, this suggests that different sensor coatings respond to distinct VOC families (e.g., alcohols vs. terpenes), enabling multidimensional discrimination. Volatile profiles provide orthogonal chemical signatures, making e-Nose data more robust for geographical classification.

Figure 9.

Histograms and scatter plots of e-Nose analysis are useful visual tools for data mining. Two-zone geographical categories, lowland (red dot; 5–750 m) and highland (green dot; 940–1500 m). Clearly separation across multiple sensors. W3S and W1W are an orthogonal base suggesting that they capture independent information about the samples.

Figure 10 integrates quality-related physico-chemical and e-Nose features. Despite combining datasets, clusters remain diffused. Physically, this reflects that bulk composition (sugars, moisture) is not strongly altitude-dependent, while volatiles are—but mixing them dilutes discriminatory power. Hybrid sets must be carefully curated; otherwise, overlapping variables mask altitude-driven differences.

Figure 10.

Histograms and scatter plots of hybrid analysis of quality related features. Two-zone geographical categories, lowland (red dot; 5–750 m) and highland (green dot; 940–1500 m). There are not clear segregated clusters or well-defined decision boundaries between categories, therefore classification by geographical origin is not feasible.

Although mixed datasets dilute discriminatory power (Figure 10), carefully curated orthogonal combinations (Figure 11) restore clear clustering by capturing complementary chemical dimensions. It explores alternative hybrid feature sets. RSG–AXC–ASH combinations yield clear clusters and decision boundaries. Physically, this reflects that reducing sugars (RSG), ASH (minerals), and antioxidants (AXC) together capture complementary aspects of honey chemistry: carbohydrate metabolism, soil mineral transfer, and floral acid profiles. Orthogonal feature selection enables classification by geographical origin, demonstrating that altitude influences honey chemistry in multiple independent dimensions.

Figure 11.

Histograms and scatter plots of hybrid analysis of alternative quality features. Two-zone geographical categories, lowland (red dot; 5–750 m) and highland (green dot; 940–1500 m). There are clear segregated clusters or well-defined decision boundaries between categories (RSG–AXC–ASH), therefore classification by geographical origin is feasible.

Therefore, the key implications are identified. Linear correlations (ASH–CVT) confirm ionic conductivity as a mineral proxy. Diastasa activity (DAC) vs. proline (PRL) reflects freshness and protein content, higher in HL honeys. Volatile profiles (e-Nose) provide orthogonal chemical signatures, more altitude-sensitive than bulk composition. Hybrid feature sets must avoid redundancy; orthogonal combinations (RSG–AXC–ASH) succeed where mixed sets fail.

6. Discussion

The mean and standard deviation values in Table 3 analyzed by sub-regions demonstrate variations in honey composition. This summarizes and highlights the importance of geographical and botanical origin as key determinants of honey’s unique characteristics. The physico-chemical features measured were within national and international standards of honey quality defined by Codex Alimentarius [19]. The following section provides an explanation of the parameter ranges and their significance for honey quality.

The water content was consistently below 20%, a threshold indicating proper maturity [1]. The pH between 3.75–4.11, considered a normal range by different authors [7,8,9], as well as the acidity levels of 50 meq/kg. The high conductivity in lowland samples suggests elevated mineral and acid content, while the more consistent values in highland samples indicate a uniform floral source [20]. Color of honeys slightly varies within clear Ambar Pfund scale. Lowland honeys are darker due to their high conductivity and ash values [21]. It was also observed that there is a strong linear correlation between these features. In addition, the antioxidant properties of honey are also related to its color, which aligns with a richer source of phenolic compounds [22].

Regarding the concentration of glucose and fructose, the samples satisfied the minimum requirement of 60 g/100 g. Additionally, all honeys exhibited sucrose levels below the stipulated maximum of 5 g/100 g. Furthermore, the higher proline content indicates the adequate processing from honeybees to honey, and while influenced by floral source, contributes to honey’s unique profile [23]. Although all features are within typical ranges, it is nonetheless a complex undertaking task to select a feature set that allows for the definition of decision boundaries capable of distinguishing honeys based on their geographical origin. As preliminary work to develop a combined RTA and DTC strategy for overcoming this challenge, a statistical analysis of the dataset structure was carried out.

The data evaluation of the geographical zones revealed that distinct, well-segregated clusters for critical features were not readily apparent (Figure 6 and Figure 7). This indicates overlapping characteristics between honeys from the two regions, necessitating the application of data mining and classification techniques.

The histograms (Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11) illustrate a high degree of variance across most features, indicating significant variability within the dataset. However, certain quality-related features, including ash content, conductivity, and HMF, exhibit a narrow and left-skewed distribution, suggesting a more constrained range of values. In contrast, proline demonstrates a more centralized distribution. These data characteristics are likely attributed to the natural variability inherent in bee honey. The scatter plots further highlight the clustering of different honey characteristics, with complex decision boundaries separating these clusters.

The DTCs based on the RTA turned out to be quite simple and intuitive against noisy data, high variance, overfitting and outliers. The RTA reduced the physico-chemical and e-Nose features from 22 to 3 with a maximum branching depth of 4. The performance of the DTC models, with scores ranging from 86% to 90%, suggests a high degree of tuning and the selection of a considerably informative feature subset.

Rivera-Mondragón et al., [24] conducted a detailed physicochemical and palynological analysis of Panamanian honeys harvested in different seasons and ecological zones including the tropical dry forest and coastal/mangrove-influenced areas, geographically identified as lowlands. Their findings provide concrete evidence that these zones represent meaningful ecological differences relevant to honey composition. Thus, the Dry Forest Zone (DFZ) is characterized by a pronounced dry season, reduced rainfall, and drought-adapted vegetation. Therefore, the honey mineral composition is mainly potassium, but its concentration varies seasonally. Also, honeys from the DFZ showed lighter color and lower electrical conductivity, consistent with lowland, drought-adapted floral sources.

However, honeys from coastal/mangrove areas tended to be darker, with higher electrical conductivity, reflecting greater mineral content. Also, the pollen diversity shifted significantly between February and April harvests, reflecting seasonal flowering pulses typical of dry forests. It implies that seasonal DFZ and vegetation phenology strongly influence nectar chemistry and pollen spectrum, producing honeys with it implies that salinity and tidal influences shape nectar mineral profiles, producing honeys with stronger flavor and higher conductivity. Lowlands honeys often show higher antioxidant activity, linked to diverse floral sources and phenolic compounds typical of costal vegetation. This confirms that vegetation and environmental conditions in these zones are directly reflected in honey quality and composition, making them ecologically and commercially distinct. Note that in Panama, moving inland from the coasts often means ascending quickly into montane or sub-montane zones. As a result, areas away from the coast are frequently synonymous with “highland” zones, since most non-coastal land rises into hills or mountains. Studies in other tropical highland regions (e.g., Colombia, Ecuador) show altitude strongly influences honey composition, with montane honeys exhibiting distinct antioxidant and mineral profiles compared to lowland honeys [25,26].

In conclusion, this study presents preliminary evidence of distinct physicochemical and e-Nose profiles among Panamanian honeys from various geographical regions, suggesting that geographical origin may influence certain measurable characteristics. This research, framed as a proof-of-concept, prioritizes the development of a practical classification framework tailored to the available data and domain constraints, rather than benchmarking across a wide range of machine learning algorithms. The model design focused exclusively on Decision Tree Classifiers (DTCs), which offer clear advantages in terms of interpretability and transparency. Similar approaches emphasizing interpretability have been highlighted in food authentication studies where transparent models are valued for regulatory and industrial adoption [10].

It is acknowledged that even preliminary studies benefit from situating their methodological choices within the context of prior work. In food origin and honey authentication research, classifiers such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forests, and Neural Networks have been widely applied, often demonstrating strong performance in terms of accuracy, robustness, and generalization [27,28]. This study did not include comparative validation against these models; it is recognized that such comparisons would provide a more comprehensive assessment of the relative strengths and limitations of DTCs.

Ongoing work is therefore directed toward addressing this limitation through the integration of comparative model validation. In particular, SVMs represent a compelling direction for future exploration given their capacity to handle high-dimensional feature spaces and their potential to outperform tree-based classifiers in scenarios involving limited sample sizes [29]. Furthermore, it is anticipated that enriching the feature set with complementary analytical methodologies—such as pollen grain profiling or CG-MS markers—will significantly improve discriminatory capabilities and contribute to a more comprehensive characterization of honey origin [30].

Author Contributions

A.D.G.: Conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft. C.D.-M.: project administration, supervision, resources. N.J.: formal analysis, methodology. R.G.: formal analysis, project administration, supervision, resources. O.G.: Conceptualization, software, data curation, investigation, writing—original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Secretaría Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación de Panamá (SENACYT), under the Programa de Movilidad Académica, Grant number MOV-2022-09.

Data Availability Statement

The experimental dataset used in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Due to the context-specific nature of the data and its collection in collaboration with local honey producers, access may be granted for academic or non-commercial purposes.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge at the Instituto de Ciencia y Tecnología de Alimentos—ICTA of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, the Centro de Investigación en Productos Naturales y Biotecnología—CIPNABIOT, and the Instituto Interdisciplinario de Investigación e Innovación—i4 of the Universidad Autónoma de Chiriquí for all the support provided for the completion of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

ELV: elevation; LL; lowlands, HL; highlands, WTR, water; ASH, ash; CVT, conductivity; AXC, antioxidant capacity; CLR, color; GLC, glucose; FRC, fructose; ASG, apparent sucrose; RSG, reducing sugar; TPH, total phenols; PH, potential of hydrogen; FAC, free acidity; TAC, total acidity; DAC, diastase activity; HMF, hydroxymethylfurfural; PRL, proline; DTCs, decision tree classifiers; W3C, aromatic ammonia compounds; W5C, aromatic and aliphatic compounds; W1S, short chain hydrocarbons; W1W, sulfur organic compounds; W2S, alcohols and partially polar compounds; W3S, short chain aliphatic compounds.

References

- Da Silva, P.M.; Gauche, C.; Gonzaga, L.V.; Costa, A.C.O.; Fett, R. Honey: Chemical composition, stability and authenticity. Food Chem. 2016, 196, 309–323, Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruoff, K.; Luginbühl, W.; Künzli, R.; Iglesias, M.T.; Bogdanov, S.; Bosset, J.O.; von der Ohe, K.; von der Ohe, W.; Amadò, R. Authentication of the Botanical and Geographical Origin of Honey by Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 6873–6880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Matute, A.I.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, S.; Sanz, M.L.; Martínez-Castro, I. Detection of adulterations of honey with high fructose syrups from inulin by GC analysis. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2010, 23, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angiogi, R.; Morrin, A.; White, B. Advantages of a Multifaceted Characterization of Honey, Illustrated with Irish Honey Marketed as Heather Honey. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga, C.; Díaz, A.; Quicazán, M. Nariz Electrónica. Fundamentos, Manejo de Datos y Aplicación en Productos Apícolas (Primera Edición); Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo, F.; Tarazona, A.; Mateo, E.M. Comparative Study of Several Machine Learning Algorithms for Classification of Unifloral Honeys. Foods 2021, 10, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maione, C.; Barbosa, F.; Barbosa, R.M. Predicting the botanical and geographical origin of honey with multivariate data analysis and machine learning techniques: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 157, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacholczyk-Sienicka, B.; Ciepielowski, G.; Modranka, J.; Bartosik, T.; Albrecht, Ł. Classification of Polish Natural Bee Honeys Based on Their Chemical Composition. Molecules 2022, 27, 4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharin, S.N.; Sani, M.S.A.; Jaafar, M.A.; Yuswan, M.H.; Kassim, N.K.; Manaf, Y.N.; Wasoh, H.; Zaki, N.N.M.; Hashim, A.M. Discrimination of Malaysian stingless bee honey from different entomological origins based on physicochemical properties and volatile compound profiles using chemometrics and machine learning. Food Chem. 2021, 346, 128654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E. Detection of honey adulteration using machine learning. PLoS Digit. Health 2024, 3, e0000536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.E.A. Factors Affecting the Physicochemical Properties and Chemical Composition of Bee’s Honey. Food Rev. Int. 2022, 38, 1330–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justavino, A.M.; Gamboa, W.G. Situación actual y perspectivas de la apicultura en Panamá. Acta Académica 2020, 38, 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Roubik, D.W. An apibotanical study of Panama: Harvest and pollen sources. J. Apic. Res. 1984, 23, 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Methods of Analysis; AOAC International: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bognadov, S.; Martin, P.; Lüllmann, C. Harmonized Methods of the European Honey Commission. Apidologie 2004, 35, S38–S81. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Boxin, O.U.; Prior, R.L. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silici, S.; Sagdic, O.; Ekici, L. Total phenolic content, antiradical, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Rhododendron honeys. Food Chem. 2010, 121, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codex Alimentarius. Codex Standard for Honey; Codex Alimentarius: Rome, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alqarni, A.S.; Owayss, A.A.; Mahmoud, A.A.; Hannan, M.A. Mineral content and physical properties of local and imported honeys in Saudi Arabia. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2014, 18, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Farsi, M.; Amri, A.; Hadhrami, A.; Belushi, S. Color, flavonoids, phenolics and antioxidants of Omani honey. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, S.; Gunnoo, J.; Marques Passos, T.; Stout, J.C.; White, B. Physicochemical properties and phenolic content of honey from different floral origins and from rural versus urban landscapes. Food Chem. 2019, 272, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guler, A.; Garipoglu, A.V.; Onder, H.; Biyik, S.; Kocaokutgen, H.; Ekinci, D. Comparing Biochemical Properties of Pure and Adulterated Honeys Produced by Feeding Honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) Colonies with Different Levels of Industrial Commercial Sugars. Kafkas Univ. Vet. Fak. Derg. 2017, 23, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Mondragón, A.; Marrone, M.; Bruner-Montero, G.; Gaitán, K.; de Núñez, L.; Otero-Palacio, R.; Añino, Y.; Wcislo, W.T.; Martínez-Luis, S.; Fernández-Marín, H. Assessment of the quality, chemometric and pollen diversity of Apis mellifera honey from different seasonal harvests in Panama. Foods 2023, 12, 3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Sharma, K.; Kumar, R. A review of physico-chemical and biological properties of honey. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2024, 12, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafere, D.A. Chemical composition and uses of honey: A review. J. Food Sci. Nutr. Res. 2021, 4, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürbüz, S.; Kıvrak, Ş. Comparative evaluation of machine learning models for discriminating honey geographic origin based on altitude-dependent mineral profiles. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-H.; Gu, H.-W.; Li, R.-J.; Qing, X.-D.; Nie, J.-F. A comprehensive review of the current trends and recent advancements on the authenticity of honey. Food Chem. X 2023, 19, 100850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prerna, C.; Shanfeng, H.; Matthew, P.; Sadaat, A.; Dominykas, B. Honey authentication using AI-based pollen analysis: A UK review. Br. Food J. 2025. advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Jović, M.; Ristivojević, P.; Lušić, D.; Milojković-Opsenica, D.; Trifković, J. Authenticity assessment of honeydew honey based on phytochemical profile. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2025, 19, 2449–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).