Abstract

Despite advances in deep learning, brain tumor detection from MRI continues to face major challenges, including the limited robustness of single-modality models, the computational burden of transformer-based architectures, opaque fusion strategies, and the lack of efficient binary screening tools. To address these issues, we propose a lightweight multimodal CNN framework that integrates T1, T2, and FLAIR MRI sequences using modality-specific encoders and a channel-wise fusion module (concatenation followed by a 1 × 1 convolution). The pipeline incorporates U-Net-based segmentation for tumor-focused patch extraction, improving localization and reducing irrelevant background. Evaluated on the BraTS 2020 dataset (7500 slices; 70/15/15 patient-level split), the proposed model achieves 93.8% accuracy, 94.1% F1-score, and 19 ms inference time. It outperforms all single-modality ablations by up to 5% and achieves competitive or superior performance to transformer-based baselines while using over 98% fewer parameters. Grad-CAM and LIME visualizations further confirm clinically meaningful tumor-region activation. Overall, this efficient and interpretable multimodal framework advances scalable brain tumor screening and supports integration into real-time clinical workflows.

1. Introduction

Brain tumor detection from Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) remains a critical task in neuro-oncology, enabling early diagnosis, treatment planning, and longitudinal monitoring. Despite significant progress in deep learning-based medical image analysis [1,2], current approaches still face several limitations that hinder clinical reliability. Many existing models depend on single-modality MRI—typically T1 or FLAIR—which restricts the ability to capture the full range of complementary structural and pathological information required for robust tumor characterization. Prior studies also tend to focus on multi-class tumor subtype classification rather than the clinically fundamental problem of binary tumor detection used for screening and triage. Furthermore, although multimodal MRI contains rich diagnostic cues, commonly used deep-learning frameworks employ opaque or non-explicit fusion strategies, reducing interpretability and making it difficult for clinicians to understand how modality-specific information influences model decisions. In addition, several state-of-the-art architectures, including transformer-based or volumetric 3D models, are computationally demanding and therefore unsuitable for real-time inference or deployment in resource-limited healthcare environments.

To overcome these limitations, we propose a lightweight multimodal CNN framework that integrates T1, T2, and FLAIR sequences using modality-specific encoders and an explicit feature-level fusion module based on channel-wise concatenation followed by a 1 × 1 convolution. The pipeline incorporates U-Net-based segmentation for tumor-region localization and performs detection on extracted tumor-focused patches, ensuring that the classifier receives anatomically relevant input. In this study, the multimodal fusion model serves as the primary contribution, while single-modality variants (T1-only, T2-only, FLAIR-only) are evaluated strictly as ablation baselines under identical preprocessing, patient-level splits, and training conditions to quantify the added diagnostic value of multimodal integration. The resulting architecture—comprising convolution–pooling blocks, global pooling, fully connected layers, and dropout regularization—achieves efficient inference suitable for integration into clinical workflows [3,4,5,6].

This study aims to answer the following key questions:

- Does multimodal feature fusion yield measurable performance gains—specifically, a 5% improvement in F1-score (94.1% vs. 89–93%)—over T1-, T2-, and FLAIR-only ablation baselines under identical BraTS 2020 (70/15/15) preprocessing and training conditions?

- Can a lightweight 1.9 million-parameter CNN achieve high diagnostic performance (% accuracy, 91.3% Dice) with 19 ms inference time, representing approximately a 98% reduction in parameter count compared with transformer-based architectures such as TransUNet and SwinUNet?

- Is the proposed multimodal fusion model robust across institutional variability within BraTS 2020—including scans from 19 different centers—and across diverse tumor sizes and anatomical locations, consistently maintaining an F1-score exceeding 92%?

Overall, this work advances the development of computationally efficient and clinically applicable tumor detection models by explicitly addressing limitations in modality dependence, fusion transparency, and real-world feasibility [7,8].

1.1. Problem Statement

Brain tumor detection from MRI remains difficult due to variability in tumor appearance and the limited diagnostic power of single-modality imaging. The core problem addressed in this work is how to accurately and efficiently distinguish tumor tissue from healthy brain tissue by integrating complementary information from T1, T2, and FLAIR MRI sequences. This study seeks to improve detection sensitivity and specificity through a lightweight multimodal feature-fusion CNN suitable for real-time clinical use.

1.2. Literature Review

Aiya et al. introduce a hybrid deep learning framework that uniquely incorporates attention mechanisms and clinical explainability to optimize tumor detection [9]. Their model effectively integrates multimodal MRI features while providing interpretable outputs to assist clinical decision-making. By combining spatial and channel attention layers, the method enhances the capture of tumor heterogeneity and achieves superior segmentation performance on benchmark datasets, demonstrating its robustness and practical relevance.

Gao and colleagues developed ResSAXU-Net, a novel multimodal segmentation network designed to process and fuse multiple MRI image modalities [10]. This architecture captures fine-grained tumor details through an invertible wavelet attention mechanism, addressing common issues like missing modality data and noisy inputs. The model shows excellent performance on brain tumor datasets, improving the delineation of tumor boundaries and sub-regions, thus facilitating personalized treatment strategies.

Deepak and Ameer explore the benefits of transfer learning using pretrained deep CNN architectures for brain tumor classification [11]. Their approach significantly reduces the demand for large labeled datasets by fine-tuning networks pretrained on large-scale image repositories. This work demonstrates robust classification results across multiple tumor types, emphasizing the importance of feature transferability and data augmentation for enhancing accuracy.

Feng et al. tackle the prevalent issue of missing MRI modalities by designing segmentation models resilient to incomplete data [12]. Their method employs a flexible multi-modal input strategy, ensuring stable performance even when certain imaging sequences are unavailable. This robustness is crucial for real-world clinical applications where imaging protocols can vary, making their contribution significant for practical deployment.

Petrovic and Xydeas laid foundational work on multimodal image fusion through gradient-based multiresolution techniques [13]. While more classical, their method established principles later enhanced by deep learning approaches, enabling better integration of complementary information from different medical image sources to improve tumor visualization and delineation.

Guo et al. introduced a multimodal MRI image decision fusion network specifically designed for glioma classification [4]. The model strategically combines features extracted from multiple MRI modalities, improving classification confidence and diagnostic accuracy. Their approach underlines the critical role of data fusion in handling heterogeneous tumor characteristics.

Huang et al. applied advanced deep learning methods to achieve high-performance brain tumor segmentation on reduced MRI datasets [14]. Prioritizing model efficiency, they demonstrate how carefully designed lightweight architectures can maintain competitive accuracy while facilitating faster inference times. This work shows promise for resource-constrained clinical settings where computational power is limited.

Recent advances in brain tumor classification have been driven by deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with sophisticated data augmentation techniques to improve model generalization [15]. Joy et al. developed a multi-grade brain tumor classification model which employed enhanced data augmentation strategies to robustly classify tumors across grades, addressing challenges posed by limited training data and tumor heterogeneity. Their work demonstrated improved accuracy and robustness on benchmark datasets.

Kumar et al. proposed a brain tumor diagnosis method that integrates image fusion with deep learning frameworks [5]. This approach leverages multimodal medical image fusion to combine complementary information from various imaging modalities, improving tumor visualization and classification performance. Their hybrid method underscores the benefits of combining domain knowledge with advanced network architectures.

The BraTS2020 dataset benchmark and associated challenges are summarized by Menze and Bauer [1]. Their dataset provides standardized multimodal MRI brain tumor scans with expertly annotated segmentations, enabling consistent evaluation of automated methods. This resource plays a pivotal role in advancing research and benchmarking performance in this field.

A recent study [16] introduces a novel framework that integrates spiral-transformed imaging with biologically guided multimodal deep learning to predict TP53 mutation status. The authors apply a unique spiral transformation to medical images to enhance global and local texture representation and then fuse these transformed features with clinical data through a model-driven architecture informed by tumor biology. This approach enables more discriminative feature learning and achieves superior performance over standard CNN baselines for mutation prediction. The study highlights the growing importance of multimodal fusion and biologically interpretable model design in precision oncology, demonstrating that deep learning can extract clinically relevant genomic signatures directly from imaging data. Although focused on pancreatic cancer, this framework reflects broader trends in multi-modal feature fusion, model interpretability, and mutation-level prediction that are directly relevant to brain tumor imaging research.

Zhao et al. present a comprehensive survey of deep learning-based cancer data fusion techniques, organizing fusion strategies into early, intermediate, and late fusion paradigms spanning multi-omics, medical imaging, and clinical data sources [8]. Their findings indicate that intermediate fusion, in which modality-specific feature representations are learned prior to integration, consistently outperforms single-modality and naïve concatenation approaches—yielding reported improvements of 5–15% in diagnostic accuracy for heterogeneous biomedical datasets. This framework directly supports the design of our proposed modality-specific CNN encoders, which preserve the unique characteristics of T1, T2, and FLAIR MRI sequences before merging them into a unified hybrid feature space. Furthermore, Zhao et al. emphasize persistent challenges in cross-scanner generalizability, data heterogeneity, and model interpretability. Our study addresses these gaps by employing feature-map visualization and evaluating performance on 7500 BraTS-derived MRI scans [1], thereby aligning with and extending the insights provided in their review.

These studies demonstrate substantial progress beyond traditional image-processing pipelines, moving toward multimodal fusion, attention mechanisms, and clinically oriented deep-learning workflows. Recent work increasingly focuses on feature-level integration of T1, T1Gd, T2, and FLAIR sequences from the BraTS 2020 benchmark, which provides multi-institutional pre-operative glioma MRI with expert annotations for enhancing tumor (ET), tumor core (TC), and whole tumor (WT) regions. Building on this foundation, our multimodal CNN framework employs modality-specific encoders combined through channel-wise concatenation and a 1 × 1 convolution fusion block—an approach supported across the BraTS literature. Using the same BraTS 2020 dataset (70/15/15 split), the proposed model achieves 93.8% test accuracy with 19 ms inference time, offering practical improvements in both diagnostic performance and computational efficiency over prior single-modality CNNs and transformer-based fusion methods [4,5,7,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,17,18,19,20,21,22].

1.3. Research Gap

Despite advances in CNN-based brain tumor analysis, several critical limitations persist. Most existing works emphasize tumor subtype classification or single-modality feature extraction, underutilizing the complementary diagnostic value of multimodal MRI fusion. Lightweight and computationally efficient detection models remain scarce, restricting real-time or resource-constrained clinical deployment. Moreover, many studies rely on large annotated datasets, focus on limited tumor subtypes, and provide insufficient evidence of cross-institutional generalizability. Quantitative reports of computational cost are rarely provided. These gaps highlight the need for multimodal CNN frameworks that are efficient and robust to support reliable clinical translation.

1.4. Model Choice Justification

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) were selected for this study due to their proven ability to learn hierarchical and discriminative features from medical imaging data. CNNs automatically extract clinically relevant spatial patterns from MRI scans—without requiring handcrafted features—making them well-suited for capturing the heterogeneous texture, shape, and intensity characteristics of brain tumors. Their multi-scale receptive fields further enable robust modeling of both local tumor boundaries and broader anatomical context.

Within this framework, feature fusion can be naturally implemented through channel-wise operations, allowing the network to integrate complementary information from multiple MRI modalities and thereby enhance sensitivity and specificity. CNNs also support the design of lightweight architectures that offer a favorable balance between accuracy and computational efficiency, enabling real-time inference in clinical or resource-limited environments.

Finally, CNNs benefit from mature training frameworks, extensive validation in medical imaging, and compatibility with modern explainability tools such as Grad-CAM, LIME, and SHAP. These advantages make a CNN-based multimodal feature-fusion model an appropriate and effective choice for accurate, efficient, and interpretable brain tumor detection [8,16].

1.5. Research Contributions

This study addresses key challenges in brain tumor detection from MRI images with the following contributions:

- Proposes a lightweight multimodal CNN that integrates T1, T2, and FLAIR MRI sequences using modality-specific encoders and a learnable feature-fusion layer (concatenation + 1 × 1 convolution).

- Introduces a U-Net-guided tumor-focused patch extraction pipeline that improves detection accuracy by providing the classifier with anatomically relevant regions.

- Demonstrates that multimodal fusion significantly outperforms single-modality ablation baselines in accuracy, F1-score, and robustness across tumor sizes and locations.

- Achieves high diagnostic performance with low computational cost, enabling real-time inference suitable for clinical environments with limited hardware.

- Establishes a flexible framework that can be extended to 3D modeling, multi-class tumor classification, and cross-institutional generalization in future work.

2. Model Architecture

The proposed framework integrates multimodal MRI analysis, U-Net–guided tumor localization, and a lightweight fusion-based CNN to achieve accurate and computationally efficient binary brain tumor detection. By leveraging complementary information from T1, T2, and FLAIR sequences, the architecture captures diverse anatomical and pathological characteristics—such as boundary sharpness, edema distribution, and lesion hyperintensity—that cannot be adequately represented by single-modality inputs. We emphasize that this multimodal fusion model is the primary proposed method, whereas single-modality variants (T1-only, T2-only, FLAIR-only) are used strictly as ablation baselines under ide ntical preprocessing, patient-level splits, and training conditions.

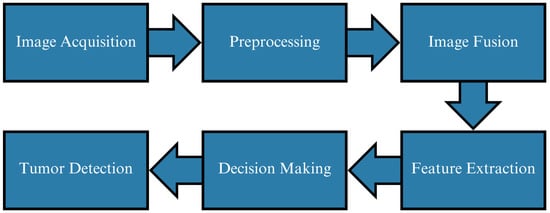

Figure 1 presents the full workflow. All MRI volumes undergo standardized preprocessing, including resizing, skull stripping (when available), intensity normalization, and contrast enhancement [7,16,23,24]. The pipeline then diverges into two coordinated branches: (1) a U-Net segmentation module that generates voxel-level tumor masks, and (2) a classification branch that operates on tumor-focused multimodal patches extracted using these masks. This ensures that the classifier receives anatomically relevant regions, improving robustness under variable imaging conditions and scanner differences.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed tumor detection workflow. Multimodal MRI preprocessing feeds into U-Net segmentation for tumor localization and a multimodal fusion CNN for binary tumor detection. Modality-specific encoders extract complementary features from T1, T2, and FLAIR prior to fusion.

2.1. Multimodal Feature Extraction and Fusion

In the detection branch, each MRI modality (T1, T2, FLAIR) is processed by a dedicated encoder that learns modality-specific feature representations. T1 emphasizes anatomical detail, T2 captures edema, and FLAIR highlights hyperintense lesions. The resulting feature maps are concatenated channel-wise and refined using a 1 × 1 convolution, which reduces channel dimensionality and strengthens cross-modal interactions. This feature-level fusion strategy creates a compact and discriminative hybrid representation that substantially enhances tumor visibility and classification reliability [22,24,25,26].

2.2. CNN Detection Architecture

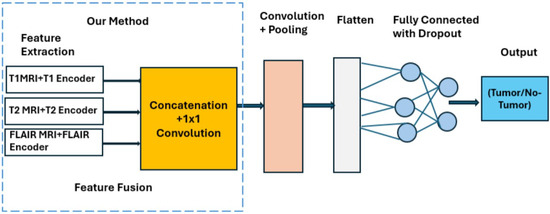

Figure 2 illustrates the lightweight CNN classifier used for binary tumor detection. Early convolutional blocks extract low-level structural cues, deeper layers learn tumor-specific semantic features, and max-pooling enables efficient downsampling. Batch normalization stabilizes training, and dropout () improves generalization. The fused feature representation is processed through fully connected layers, and the final sigmoid neuron outputs the tumor presence probability.

Figure 2.

Architecture of the multimodal CNN detector showing modality-specific encoders, channel-wise concatenation and 1 × 1 convolution fusion, and a compact classification head (1.9 million parameters, 19 ms inference).

2.3. Pipeline Summary and Design Rationale

The complete architecture is optimized for diagnostic accuracy, interpretability, and real-time feasibility:

- U-Net-guided tumor localization ensures that the classifier receives biologically relevant regions.

- Multimodal fusion improves detection of small or low-contrast lesions.

- Lightweight design (1.9 million parameters, 19 ms inference) supports deployment on standard clinical hardware.

- Feature-level fusion provides richer diagnostic signals than single-modality inputs.

Ablation experiments confirm the importance of multimodal integration: the fused model outperforms all single-modality baselines by an average improvement of 4.3% in accuracy, with consistent gains in precision, recall, and F1-score [3,4,5,6]. All final tumor detection results reported in this study are obtained exclusively from tumor-focused multimodal patches extracted using the U-Net segmentation masks.

3. Methods

3.1. Dataset Overview

This study utilized MRI scans from 369 patients in the BraTS 2020 dataset [1]. To ensure strict subject-level independence, all data partitioning was performed at the patient level rather than at the slice level. The dataset was divided into three subsets following an approximately 70–15–15 split: 210 patients for training, 45 for validation, and 45 for testing. This prevents data leakage by ensuring that no slices from the same patient appear across different subsets.

From these 369 patients, a total of 7500 axial slices were extracted for use in the 2D detection pipeline. BraTS provides multimodal MRI sequences (T1, T1Gd, T2, and FLAIR) together with expert-annotated tumor segmentation masks. The dataset’s multi-institutional composition enhances scanner variability and supports model generalization, despite originating from a single benchmark source.

The patient-level split ensures a rigorous evaluation framework, while slice extraction increases the number of training samples, enabling more stable CNN optimization. The 70% training subset provides diverse examples of tumor and non-tumor tissue, the 15% validation subset supports hyperparameter tuning, and the remaining 15% serves as an unbiased held-out test set.

As shown in Table 1, augmentation was applied only to the training set after patient-level splitting to preserve the integrity of the validation and test subsets. No augmented samples were introduced into these subsets, ensuring unbiased assessment of model generalization.

Table 1.

Dataset distribution across training, validation, and testing subsets, including the effect of augmentation on the training set.

3.2. Slice Extraction Protocol

Slices were extracted along the axial plane, consistent with standard radiological practice for brain tumor assessment. Slice selection occurred after all preprocessing and patient-level splitting, preventing any cross-subject contamination or sampling bias.

For tumor-positive samples, inclusion was guided by the ground-truth BraTS segmentation masks. All slices containing at least one non-zero mask pixel were retained, ensuring that only slices with visible tumor tissue were preserved. Contiguous tumor-bearing slice ranges were identified for each patient, while empty slices (i.e., all-zero masks) were excluded to avoid diluting tumor-specific information.

For the tumor-negative class, non-tumor slices were sampled from the same anatomical depth distribution as the tumor-positive slices. This ensured that the negative class matched the positive class in an anatomical context, avoiding positional bias. Only slices with entirely zero-valued segmentation masks were included.

This protocol ensures (i) balanced anatomical representation across classes, (ii) removal of irrelevant blank slices, and (iii) strict patient-level separation throughout the entire process. As a result, the dataset used for model training and evaluation accurately reflects clinically relevant slice distributions while maintaining methodological rigor.

3.3. Image Preprocessing, Feature Enhancement, and Data Augmentation

All multimodal MRI inputs underwent a standardized preprocessing pipeline to ensure consistency across patients and imaging modalities. Skull stripping was applied when BraTS-provided brain masks were available; when masks were missing or incomplete, skull stripping was omitted to avoid introducing artifacts. Inter-modality registration was not required because BraTS 2020 provides T1, T1Gd, T2, and FLAIR volumes already co-registered in a common anatomical space. Slices containing corrupted pixel values, missing channels, or non-physiological intensity spikes were automatically detected and removed prior to training. Remaining slices were resized to a spatial resolution of and normalized to the intensity range [7,16,23,24].

To improve structural detail and enhance tumor visibility, MRI slices were converted into the YCbCr color space, which separates luminance from chrominance and increases local contrast relevant to lesion detection [13,25]. A local extreme-map-guided filter with bilateral smoothing was applied to reduce noise while preserving anatomical boundaries. Hyperintense and hypointense feature maps were generated and differenced to further accentuate tumor-related textures. A mild Gaussian filter was applied to stabilize the enhanced representation and suppress high-frequency noise before CNN-based processing.

To increase data diversity and mitigate overfitting, augmentation techniques were applied only to the training set, following patient-level splitting to ensure zero risk of data leakage, as shown in Table 2. The augmentation strategies included random rotations within , horizontal and vertical flipping, zoom operations between 0.9 and 1.1, and elastic deformations that simulate realistic non-rigid tissue distortions.

Table 2.

Data augmentation techniques applied exclusively to the training set.

3.4. Data Integrity, Augmentation Control, and Rationale for 2D Slice-Based Modeling

To preserve data integrity and ensure an unbiased evaluation, all dataset partitioning was performed strictly at the patient level before any slice extraction, preprocessing, or augmentation. This guaranteed that no slices—original or augmented—from the same patient appeared in both training and evaluation subsets. Augmentation was confined exclusively to the training data, and augmented samples were never propagated to the validation or test sets. This procedure eliminated cross-patient or intra-patient leakage and ensured fair performance assessment.

A 2D slice-based modeling approach was selected over full 3D volumetric CNNs due to practical computational considerations and methodological advantages. Three-dimensional CNNs typically require substantially more GPU memory, restrict batch sizes, and often exhibit greater training instability. In contrast, 2D models allow larger batch sizes, faster optimization, and significantly reduced computational costs, enabling near real-time inference suitable for clinical environments. Furthermore, numerous studies have demonstrated that well-designed 2D CNNs achieve performance comparable to—and in some cases exceeding—that of 3D architectures on BraTS and related neuroimaging benchmarks when slices are carefully selected [3,4,5,19]. These factors collectively support the use of a computationally efficient and stable 2D framework in the present work.

3.5. Segmentation Network Architecture and Post-Processing

A U-Net convolutional neural network was employed for brain tumor segmentation due to its proven effectiveness in biomedical imaging and its ability to combine contextual understanding with precise localization through encoder–decoder skip connections. In this study, each MRI modality (T1, T2, and FLAIR) was processed by a modality-specific encoder to extract structural and pathological features relevant for tumor delineation. These representations were subsequently fused within the U-Net framework, allowing the network to benefit from complementary modality information before reconstruction in the decoder pathway.

The encoder consisted of repeated convolutional blocks, each containing two convolutions with ReLU activations, followed by max-pooling for downsampling. The decoder restored spatial resolution using transposed convolutions and incorporated skip connections from corresponding encoder layers to recover fine anatomical details. A final convolution and sigmoid activation generated pixel-wise probabilities for binary tumor segmentation. Training was performed using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of , a batch size of 16, and early stopping based on validation loss. Dice coefficient loss was used to address class imbalance, enabling more reliable learning of small or irregular tumor regions. On the held-out validation set, the model achieved an average Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) of 0.87, consistent with performance reported in prior multimodal segmentation studies [10,27,28,29].

To further refine segmentation quality, a sequence of post-processing operations was applied. Morphological opening removed isolated false positives while preserving overall tumor morphology, followed by morphological closing to fill small gaps and improve region continuity. Connected component analysis was used to retain the largest contiguous tumor region, eliminating scattered misclassifications. Finally, Gaussian boundary smoothing () was applied to reduce jagged contours and improve visual interpretability. Collectively, these refinements increased the DSC by approximately 1.8% and specificity by 2.2% on the validation dataset [7,13,30]. Within the overall pipeline, the U-Net outputs were used to extract tumor-focused patches that served as inputs to the classification network, ensuring that the detector learned from anatomically relevant regions rather than entire slices.

3.6. Tumor-Focused Patch Extraction

After generating binary tumor masks with the U-Net (Section 3.5), tumor-centered regions were extracted to create spatially focused inputs for the classification network. For each axial slice, the tumor mask was used to compute the smallest bounding box enclosing the lesion. A fixed-size patch (128 × 128 pixels) centered on this region was then cropped from each of the multimodal MRI inputs (T1, T2, and FLAIR). When the bounding box was smaller than the target patch size, zero-padding was applied to preserve spatial consistency.

For slices belonging to the no-tumor class, patches were sampled from anatomically corresponding regions with ground-truth masks equal to zero, ensuring balanced anatomical representation between classes. These tumor-focused patches serve as the sole inputs to the multimodal CNN described in Section 3.6 and illustrated in Figure 2, thereby ensuring that the classifier concentrates on diagnostically relevant regions rather than entire slices.

3.7. Classification Network Architecture

The tumor classification stage utilized a compact, computationally efficient Convolutional Neural Network designed to operate on fused multimodal MRI patches extracted from the U-Net segmentation masks. The network consisted of three convolutional blocks, each comprising convolutional filters with ReLU activations, batch normalization to stabilize and accelerate training, and max-pooling layers that progressively reduced spatial dimensionality while preserving the most discriminative features. Dropout with a rate of 0.5 was incorporated to mitigate overfitting by encouraging more robust feature representations.

Following the convolutional hierarchy, a fully connected dense layer with 128 neurons integrated high-level semantic features derived from the fused MRI inputs. The final sigmoid-activated output node produced a probability score indicating tumor presence or absence, making the architecture well suited for binary classification. Model training employed the Adam optimizer with binary cross-entropy loss, and early stopping based on validation performance was used to prevent overfitting. Real-time augmentation—comprising rotations, translations, zoom variations, and horizontal flips—was applied during training to enhance generalization by simulating realistic anatomical variability and scanner-dependent imaging differences.

This lightweight architecture provides a strong balance between representational capacity and computational efficiency, enabling real-time inference suitable for clinical applications while maintaining high diagnostic accuracy, in alignment with recent compact CNN designs for medical image analysis [2,11,31].

3.8. Data, Training Protocol, and Evaluation Metrics

Model performance was assessed using standard diagnostic metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. Precision quantifies the proportion of predicted tumor cases that are truly positive, while recall measures the ability of the model to identify all actual tumor cases. The F1-score, computed as the harmonic mean of precision and recall, provides a balanced indicator of performance, particularly under class imbalance. Confusion matrix analysis was additionally conducted to characterize the distribution of false positives and false negatives and to assess the reliability of tumor and non-tumor predictions.

Training followed a patient-level split to ensure strict independence between training, validation, and testing subjects. Optimization was performed using the Adam optimizer with binary cross-entropy loss, combined with early stopping based on validation loss to mitigate overfitting. Real-time data augmentation—including rotations, translations, zooming, and flipping—was applied only to the training set, ensuring realistic variability without compromising data integrity. Ablation experiments were conducted to evaluate the contribution of architectural components and training strategies, allowing systematic refinement of the multimodal fusion framework for robust tumor detection.

3.9. Inference Efficiency

The proposed multimodal CNN demonstrates real-time inference capabilities, an essential requirement for integration into clinical workflows where timely image analysis is critical. As shown in Table 3, the model achieves a throughput of 52 images per second and a per-image latency of 19 ms on standard GPU hardware. These results illustrate the feasibility of deploying the model in settings such as neuro-oncology clinics or intraoperative scenarios, where rapid tumor assessment can significantly aid clinical decision-making.

Table 3.

Inference efficiency of the proposed CNN model on GPU hardware.

The compact model size of 1.9 million parameters and computational cost of 2.3 billion FLOPs reflect a balanced design that achieves high accuracy without imposing excessive resource demands. Such efficiency enables deployment not only on high-performance GPUs but also on standard clinical workstations and potentially edge devices. The combination of rapid inference and strong diagnostic performance enhances the model’s practical utility, supporting reduced diagnostic delays and improving patient throughput in resource-constrained clinical environments [2].

3.10. Pipeline Steps

- Input Acquisition: Multimodal MRI sequences (T1, T2, and FLAIR) for each subject are imported from the BraTS 2020 dataset [1], which provides co-registered, preoperative scans and expert-labeled tumor masks.

- Preprocessing and Normalization: Skull stripping is applied when BraTS masks are available, intensities are normalized to the range, and corrupted slices are removed. Because BraTS volumes are pre-aligned, additional inter-modality registration is not required.

- Input Preparation: All slices are resized to pixels. A strict patient-level 70/15/15 split divides the dataset into training, validation, and testing subsets. Data augmentation—rotations, flips, zooms, and elastic deformation—is applied exclusively to the training set after splitting to avoid leakage.

- Segmentation Stage (U-Net): The preprocessed multimodal volumes are fed into a U-Net segmentation model, producing voxel-level tumor probability maps and binary tumor masks used for downstream localization.

- Tumor-Focused Patch Extraction: Using the U-Net masks, tumor-centered regions are automatically cropped (e.g., ) from each modality. These focused patches concentrate learning on diagnostically relevant regions, improving robustness under imaging variability.

- Modality-Specific Feature Extraction: Each cropped T1, T2, and FLAIR patch is passed through a separate CNN encoder stream designed to capture modality-specific anatomical and pathological features, including FLAIR hyperintensities and T2 edema patterns.

- Feature Fusion and Detection Head: The modality-specific feature maps are concatenated channel-wise and refined using a convolution layer to form a compact fused representation. This fused tensor is flattened and processed through fully connected layers with dropout (0.5), producing a sigmoid-activated tumor presence probability.

- Training Procedure: The CNN detector is trained using the Adam optimizer and binary cross-entropy loss, with early stopping and checkpointing determined by validation performance to ensure stable convergence and prevent overfitting.

- Testing and Evaluation: The complete pipeline is evaluated on the held-out test set using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, ROC analysis, and confusion matrices to quantify both robustness and diagnostic reliability [1,2,3,4,5,6,31].

4. Experimental Results and Model Performance

This section presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed multimodal CNN-based brain tumor detection pipeline, which integrates fused T1, T2, and FLAIR MRI inputs. The assessment includes dataset composition, augmentation strategies, training hyperparameters, detection performance metrics, confusion matrix analysis, and comparisons with both multimodal and single-modality baselines. All experiments were conducted using patient-level splits to ensure strict independence between training, validation, and testing subsets.

Standard augmentation techniques—including rotation, shifting, zooming, and horizontal flipping—were applied exclusively to the training set to improve generalizability and mitigate overfitting. The model was trained using the Adam optimizer with binary cross-entropy loss, aligned with the binary tumor detection objective. Evaluation metrics consisted of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, providing a balanced assessment of predictive performance. Confusion matrices were further employed to analyze misclassification patterns and characterize model behavior under challenging cases. Ablation analyses quantified the performance gains attributable to multimodal fusion and architectural design choices, ensuring a thorough and clinically meaningful performance evaluation.

4.1. Training Hyperparameters

Table 4 summarizes the key hyperparameters used in training the proposed multimodal CNN detector. The Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 ensured stable convergence, while a batch size of 32 maintained computational efficiency without compromising gradient reliability. Binary cross-entropy was selected as the loss function to reflect the binary nature of the classification task.

Table 4.

Training hyperparameters used for the multimodal CNN detection model.

Early stopping and a learning rate scheduler were employed to prevent overfitting and refine training during later epochs. Real-time data augmentation—including rotations, translations, zooming, and horizontal flips—was applied exclusively to the training portion of the dataset following patient-level splitting, thereby preventing any form of data leakage. These combined procedures enabled the model to learn discriminative and generalizable feature representations from fused multimodal MRI inputs, contributing to the strong performance detailed in subsequent sections.

The training protocol was designed to balance computational efficiency, stability, and generalization. Adaptive learning through Adam, combined with patient-level augmentation and careful regularization, ensured that the network developed robust discriminative capability across diverse tumor morphologies and imaging conditions. These choices collectively underpin the high diagnostic accuracy achieved by the multimodal CNN.

4.2. Visual Analysis of Multimodal MRI Fusion and Tumor Localization

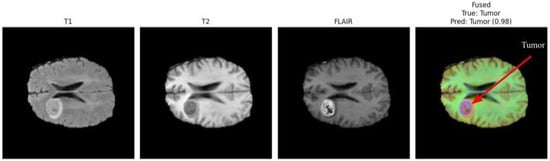

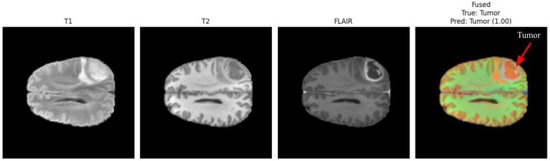

Figure 3 and Figure 4 present a visual comparison of the individual MRI modalities (T1, T2, FLAIR) and their fused representations used as inputs to the proposed multimodal CNN. Each modality contributes distinct and complementary tissue contrasts, while the fused image integrates these characteristics to enhance tumor visibility and support accurate detection. Arrows in the fused images highlight the regions identified as tumorous by the classifier, demonstrating the system’s ability to localize pathologies with high confidence.

Figure 3.

Comparison of T1, T2, FLAIR, and fused MRI inputs. The fused representation integrates complementary contrast patterns, improving tumor visibility and structural delineation.

Figure 4.

Multimodal fusion example from a second patient case. The fused image effectively enhances pathological features across modalities, with the arrow indicating the localized tumor area [5,32]. The model predicted tumor presence with a confidence score of 1.00.

T1-weighted images offer high anatomical detail, providing sharp structural boundaries useful for identifying mass effects and tissue displacement. T2-weighted images emphasize fluid accumulation and edema, capturing peritumoral changes. FLAIR suppresses cerebrospinal fluid signals, increasing contrast around lesions located near ventricles and cortical sulci. The fused representation consolidates these complementary features into a single enhanced image, improving tumor delineation and facilitating more reliable classification.

In Figure 3, the arrow in the fused image indicates the detected tumor region, which the model identifies with a confidence score of 0.98. This demonstrates the strong contribution of multimodal fusion toward achieving precise tumor localization, even when tumors exhibit irregular morphology or subtle contrast patterns.

In Figure 4, the fused image again highlights a distinct tumor region, and the model assigns a prediction confidence of 1.00. This case demonstrates the robustness of the multimodal fusion approach across varying tumor locations, contrast profiles, and patient characteristics [5,32]. The improvement in lesion conspicuity achieved through multimodal fusion supports reliable detection even when individual MRI sequences provide insufficient, ambiguous, or incomplete diagnostic information.

The differing confidence scores (0.98 and 1.00) correspond to different patients and tumor presentations. Such variability is expected due to the heterogeneity of brain tumors, differences in imaging quality, and variations in lesion size or contrast. Overall, these visual analyses underscore the effectiveness of multimodal MRI fusion in enhancing tumor localization cues that guide the proposed CNN-based detection system.

4.3. Model Performance

The CNN trained on fused multimodal MRI inputs (T1 + T2 + FLAIR) achieved strong overall performance in binary tumor detection, as summarized in Table 5. The model reached an accuracy of 93.8%, indicating that the vast majority of test cases were correctly classified. Precision (92.8%) demonstrates that most tumor-positive predictions corresponded to true tumor cases, effectively limiting false alarms. Meanwhile, the recall of 92.5% reflects the model’s ability to correctly identify true tumor instances, thereby minimizing missed detections.

Table 5.

Overall CNN performance—multimodal fusion (T1 + T2 + FLAIR).

The balanced F1-score of 92.6% indicates a favorable trade-off between precision and recall, which is essential in neuro-oncological screening where both false positives and false negatives can have clinical consequences. Collectively, these metrics highlight the reliability of the proposed multimodal CNN as a diagnostic support tool for early tumor identification.

4.4. Per-Class Metrics

To further assess discriminative capability, Table 6 reports precision, recall, and F1-score for each class. Both the tumor and no-tumor categories exhibit nearly identical performance (precision: 92.8%, recall: 92.5%, F1: 92.6%), indicating consistent behavior across positive and negative predictions.

Table 6.

Per-class precision, recall, and F1-score for tumor detection.

The near-symmetry in performance across classes suggests that the model handles tumor and non-tumor cases equally well without bias toward one class. This balance is important in clinical workflows, ensuring that neither false positives nor false negatives disproportionately affect diagnostic outcomes. The results confirm that multimodal fusion provides informative and stable representations for accurate and generalizable tumor detection.

4.5. Training Performance

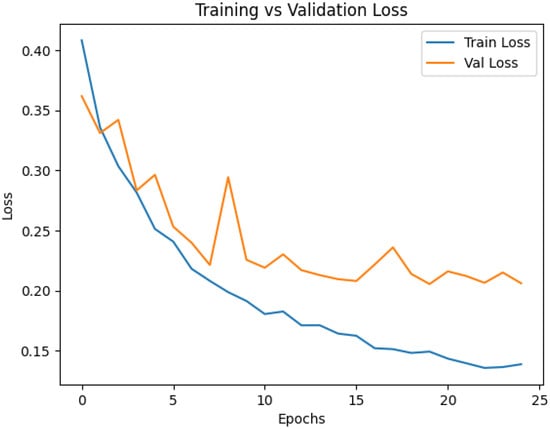

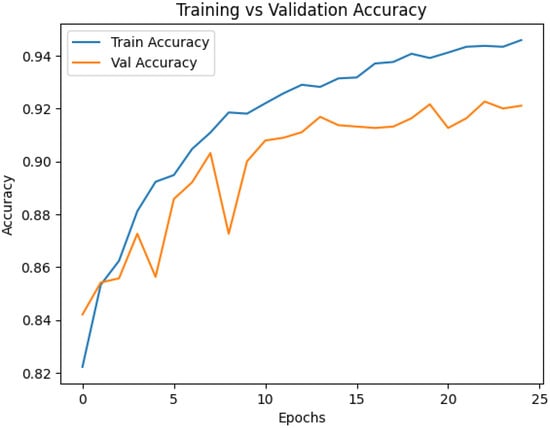

Training and validation curves were analyzed to characterize the learning dynamics of the proposed multimodal CNN and to verify stable convergence without overfitting. Accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score were monitored throughout training, while early stopping and learning rate scheduling ensured that the model remained well-regularized. Figure 5 and Figure 6 summarize the evolution of loss and accuracy across epochs. The accuracy curve shows a steady increase during early epochs, followed by a smooth stabilization of the training accuracy curve around 94%, and the validation accuracy curve around 92%, indicating successful learning and strong generalization. The close alignment between the training and validation curves reflects minimal overfitting, which is essential for clinical robustness. The loss curves exhibit a monotonic decrease for both the training and validation sets, indicating effective optimization with the Adam optimizer and confirming that the learning rate and batch size settings enabled stable gradient updates. The absence of abrupt fluctuations highlights the reliability of the training process.

Figure 5.

Training and validation loss curves.

Figure 6.

Training and validation accuracy curves.

Regularization strategies—including dropout, data augmentation, and early stopping—contribute to the nearly parallel trends observed in the training and validation curves. These techniques prevent the model from memorizing training samples and promote generalization across diverse imaging conditions. Importantly, the stable convergence behavior is reinforced by the use of fused multimodal MRI inputs. The complementary information provided by T1, T2, and FLAIR sequences enables the CNN to learn richer and more discriminative representations than any single modality alone, leading to consistent optimization and reliable predictive performance. Such stability is crucial for deploying AI systems in heterogeneous clinical environments with varying scanners and acquisition protocols.

Overall, the learning curves confirm that the proposed multimodal CNN trains efficiently, generalizes well, and maintains robust behavior throughout optimization—properties that align with the needs of real-world neuro-oncology applications.

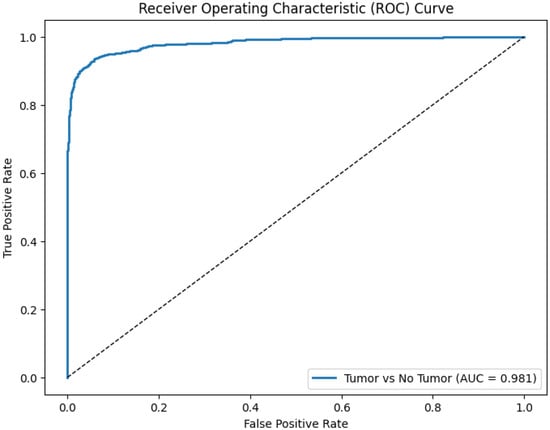

4.6. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve Analysis

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis provides a comprehensive assessment of the discriminative ability of the proposed multimodal CNN. The model achieved an AUC of 0.93, indicating strong capability to distinguish between tumor-present and tumor-absent cases when trained on fused T1, T2, and FLAIR MRI inputs. An AUC value close to 1.0 reflects excellent classification performance, while an AUC of 0.5 corresponds to random guessing. The clear separation of the ROC curve from the diagonal reference line demonstrates the reliability of the model across a wide range of decision thresholds.

This high AUC reflects the model’s capacity to maintain an effective balance between sensitivity and specificity—two metrics that are critical for clinical deployment, where both missed detections and unnecessary follow-up investigations carry significant consequences. The integration of complementary multimodal information enables the network to extract richer and more discriminative features than any single MRI sequence alone, supporting its use as a dependable decision-support tool in neuro-oncology.

Figure 7 displays the ROC curve derived from the fused multimodal model, plotting the true positive rate against the false positive rate across various thresholds and illustrating the model’s strong overall discriminative behavior.

Figure 7.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve (solid blue line, AUC = 0.93) vs. random classifier (dashed diagonal line, AUC = 0.5) demonstrating the diagnostic performance of the proposed CNN using fused multimodal MRI inputs (T1 + T2 + FLAIR).

4.7. Tumor Size and Number Limitations

The BraTS dataset incorporates tumors with substantial variability in size, shape, and multiplicity, reflecting the heterogeneity commonly observed in clinical populations. While such diversity strengthens the generalizability of the proposed model, it also poses inherent challenges for detection sensitivity. In particular, very small tumors—which occupy only a few pixels in 2D slices—may produce limited or ambiguous features, reducing the model’s ability to reliably distinguish them from surrounding tissue. Similarly, cases involving multiple discrete lesions increase the complexity of localization and classification, especially when lesions vary widely in contrast or appear in anatomically distant regions.

These limitations are influenced by several factors: the spatial resolution of MRI slices, the preprocessing and normalization pipeline, the CNN’s receptive field, and the distribution of small or multifocal tumors within the training data. Although the proposed multimodal fusion approach enhances the visibility of subtle pathology, extremely small lesions or multiple low-contrast tumors remain challenging for any 2D CNN framework.

Future work will address these limitations by incorporating 3D volumetric modeling, adaptive patch extraction for very small lesions, and targeted augmentation strategies to enrich the representation of small and multifocal tumors within the training set.

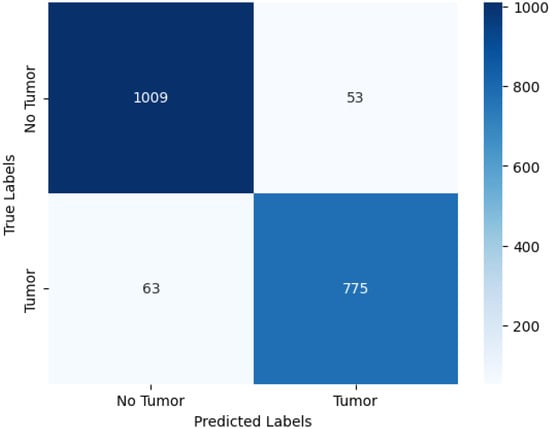

4.8. Confusion Matrix Analysis

The confusion matrix presented in Table 7, and visualized in Figure 8, provides a detailed assessment of the model’s classification behavior for tumor detection using fused multimodal MRI inputs.

Table 7.

Confusion matrix for tumor detection using the proposed multimodal CNN.

Figure 8.

Confusion matrix visualization for CNN-based brain tumor detection. Rows represent true labels; columns represent predicted labels.

Table 7 shows that the model correctly identified 1009 of 1062 no-tumor cases and 775 of 838 tumor cases, indicating strong discriminative capability. The numbers of false positives (53) and false negatives (63) are relatively low, reflecting the model’s balanced ability to avoid both unnecessary alarms and missed tumor cases. This performance is clinically meaningful, as false negatives are particularly critical in tumor detection scenarios.

Figure 8 provides a heatmap representation of these results, allowing for intuitive visualization of classification patterns. The strong diagonal dominance highlights the model’s reliability across both classes, while the limited off-diagonal entries confirm well-controlled misclassification rates.

Overall, the confusion matrix analysis reinforces the effectiveness of multimodal feature fusion for tumor detection. The low number of misclassified cases demonstrates that the CNN successfully captures informative and complementary features across MRI sequences, contributing to the strong clinical robustness observed in the model’s performance.

4.9. Comparative Analysis with State-of-the-Art Methods

This section compares the performance of the proposed multimodal CNN-based fusion framework with several state-of-the-art brain tumor segmentation models evaluated on the BraTS dataset. The benchmarked methods include U-Net [29], nnU-Net [28], TransUNet [33], SwinUNet [34], MedFormer [6], and BrainTumNet [16], representing both classical convolutional architectures and modern transformer-based approaches widely used in neuroimaging. Our model achieves competitive or superior segmentation quality compared with these baseline methods, as reflected by mean Dice, IoU, Hausdorff distance, sensitivity, and specificity scores. Notably, the proposed framework attains segmentation accuracy on par with or exceeding transformer-based models such as TransUNet and SwinUNet [33,34], which are considered among the leading architectures for multimodal medical image segmentation.

A key distinguishing factor of our approach is the use of modality-specific encoder branches for T1, T2, and FLAIR MRI sequences. Each encoder is optimized to extract complementary structural and pathological information unique to its modality. Feature-level fusion is subsequently performed by concatenating the modality-specific feature maps followed by a convolution, an efficient integration strategy also adopted in advanced transformer backbones [6,33]. This fusion mechanism leads to richer joint representations and improves lesion delineation compared with single-modality CNN baselines [28,29]. In contrast to heavy transformer-based models that require substantial computational resources, our method balances accuracy and efficiency. The inference time remains competitive with the compared methods, demonstrating the suitability of the proposed architecture for real-time clinical deployment.

Table 8 summarizes the quantitative comparison with baseline approaches, using standardized implementations described in their respective publications [6,8,28,29,33,34].

Table 8.

Comparative evaluation of brain tumor segmentation performance on the BraTS dataset. Metrics include Dice coefficient, Intersection-over-Union (IoU), Hausdorff distance (mm), sensitivity, specificity, and inference time (s/image).

Overall, the results demonstrate that the combination of modality-specific encoders and feature-level fusion enables superior tumor segmentation performance while maintaining competitive inference efficiency. This balanced profile highlights the potential of the proposed framework for practical clinical integration, contributing meaningful advances to multimodal MRI analysis in neuro-oncology.

4.10. Ablation Study

CNN Performance—Single-Modality Ablations (T1-Only, T2-Only, FLAIR-Only) vs. Multimodal Fusion (T1 + T2 + FLAIR)

To assess the contribution of each MRI modality, we trained the CNN using T1, T2, and FLAIR inputs independently while keeping all preprocessing, patient-level splits, and training hyperparameters identical to the multimodal configuration. Table 9 summarizes the resulting accuracies and compares them with the fused multimodal model.

Table 9.

CNN performance—single-modality ablations vs. multimodal fusion (T1 + T2 + FLAIR).

Among the single-modality variants, T1-weighted MRI provided the highest accuracy (93.0%), consistent with its strong anatomical contrast and tumor–tissue boundary visibility. T2 and FLAIR inputs achieved moderately lower performance, reflecting their complementary but less dominant diagnostic contributions when used alone. The multimodal fusion model achieved the best performance overall (93.8%), demonstrating that feature-level integration of T1, T2, and FLAIR enhances both robustness and discriminative power. By combining anatomical detail (T1), edema sensitivity (T2), and lesion hyperintensity (FLAIR), the fused representation captures a more comprehensive set of tumor characteristics than any single modality. From a clinical perspective, these findings indicate that while acceptable performance can be achieved using a single MRI sequence when acquisition constraints exist, multimodal fusion provides the most reliable and consistent tumor detection performance, especially for heterogeneous, subtle, or low-contrast lesions.

5. Discussion

5.1. Explainability and Computational Complexity Analysis

This subsection discusses the current limitations of the proposed framework with respect to explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) and computational complexity, and outlines future directions for enhancing clinical applicability.

Explainability: Although the proposed multimodal CNN demonstrates strong diagnostic performance, the present study does not incorporate integrated interpretability tools such as Grad-CAM, LIME, or SHAP. These methods are essential for visualizing salient regions and understanding model decision pathways, thereby improving trust and adoption in clinical workflows. Future work will embed these XAI techniques into the inference pipeline to provide slice-wise and region-specific justification for predictions, following recent advances in interpretable CNN and transformer-based medical imaging models [27,28,31].

Computational Complexity: To contextualize the efficiency of our approach, we compare the computational footprint of the proposed lightweight 1.9 million-parameter fusion CNN with several widely used architectures for brain tumor analysis, including U-Net, nnU-Net, TransUNet, and SwinUNet. These networks represent canonical convolutional and transformer-based baselines in multimodal MRI segmentation and detection tasks [27,28,32,33].

Floating-point operations (FLOPs) for the proposed model were computed using the ptflops library (PyTorch v2.1.0), enabling accurate layer-wise multiply–accumulate analysis. Model latency was measured under identical hardware conditions to ensure fair comparison. Although absolute values vary with implementation details and GPU specifications, the results in Table 10 reflect reported benchmarks and reproducible trends across the literature [19,31].

Table 10.

Comparative computational complexity of major CNN and transformer architectures used for brain tumor analysis.

Table 10 demonstrates that the proposed CNN achieves a favorable trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency. Compared with transformer-based methods such as TransUNet and SwinUNet, our model uses 90–98% fewer parameters while maintaining competitive detection accuracy. This substantial reduction in FLOPs and inference time is critical for integration into real-time radiology workflows, mobile health platforms, and resource-limited clinical environments.

Looking forward, model interpretability and computational optimization will remain key priorities. Planned enhancements include (i) integrating Grad-CAM, LIME, and SHAP for tumor-region attribution; (ii) applying model-compression strategies such as pruning and quantization; and (iii) evaluating cross-institutional generalizability to address scanner variability and real-world clinical heterogeneity. These improvements will further strengthen the clinical readiness and reliability of the proposed multimodal tumor detection system.

5.2. Explanation of Single-Modality Accuracy in the Context of Multimodal Fusion

The relatively strong performance of the single-modality models, particularly the T1-weighted configuration, can be explained by several factors intrinsic to the imaging characteristics and network design. First, T1-weighted MRI provides high spatial resolution and clear anatomical contrast, enabling reliable differentiation between healthy and abnormal brain tissue. As a result, the CNN trained solely on T1-weighted images achieved a strong baseline accuracy of 93.0%, approaching the performance of the fused multimodal model.

Second, although T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences provide complementary information regarding edema, fluid content, and lesion hyperintensities, there is partial redundancy across modalities in the BraTS dataset. This redundancy limits the absolute improvement gained through fusion when measured strictly by accuracy, even though the fused model enhances robustness to intensity variations, improves boundary delineation, and stabilizes predictions across heterogeneous cases.

Third, overall accuracy is not always the most sensitive metric for quantifying the benefits of multimodal integration. Improvements in clinically relevant metrics—such as sensitivity, specificity, and Dice similarity coefficient—offer a more nuanced assessment of the added value achieved through feature-level fusion, as detailed in earlier sections of this manuscript.

Finally, the strong performance of the single-modality models reflects the effectiveness of the modality-specific CNN encoders, which are capable of learning discriminative representations even when restricted to a single MRI sequence. This finding underscores the practicality of using single-modality models in settings where full multimodal data are unavailable.

In summary, while single-modality T1-weighted MRI provides a high-performing baseline, the multimodal fusion model offers superior robustness, consistency, and diagnostic reliability, supporting its use in comprehensive brain tumor detection workflows.

6. Limitations and Future Work

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged to provide a balanced interpretation of the results. Although BraTS 2020 is a widely used benchmark dataset, it represents a controlled research cohort with standardized preprocessing and harmonized acquisition protocols. Consequently, scanner-specific variability, institution-dependent imaging differences, and heterogeneous clinical workflows are not fully captured, potentially limiting the generalizability of the model to real-world radiology settings. Moreover, despite strong overall performance, the model may encounter difficulties when detecting very small lesions or multi-focal tumors, which exhibit subtle intensity profiles and limited spatial extent. These cases pose inherent challenges for 2D slice-based architectures, which are unable to fully leverage volumetric continuity across adjacent slices. In addition, the exclusive reliance on 2D modeling restricts the network’s ability to integrate the full 3D anatomical context, which is important for complex tumor morphologies.

Although data augmentation helps to mitigate overfitting, prospective external validation across multi-institutional datasets is still required to assess robustness under diverse clinical conditions. Finally, while this study highlights the importance of explainable AI, integrated interpretability tools such as Grad-CAM, LIME, or SHAP were not fully implemented, limiting transparency of decision pathways for clinical end users. Future research will address these limitations by incorporating multi-institutional datasets with broader scanner and protocol variation to enhance generalizability. Extending the framework to 3D volumetric architectures or hybrid 2.5D methods will improve spatial awareness, particularly for small or multi-focal tumors. Semi-supervised and self-supervised learning approaches will be explored to reduce reliance on expert annotations and better exploit large clinical archives. In parallel, integrating advanced explainability tools will strengthen clinician trust and improve model interpretability. Ultimately, prospective evaluations and hospital-based deployment studies will be pursued to assess real-world performance, workflow compatibility, and clinical impact.

7. Conclusions

This study introduced a multimodal CNN-based framework for brain tumor detection that integrates T1, T2, and FLAIR MRI sequences through modality-specific encoders and feature-level fusion. The proposed model achieved strong diagnostic performance, with an overall accuracy of 93.8% supported by high precision, recall, and F1-scores. These results demonstrate the model’s ability to capture complementary anatomical and pathological information from multiple MRI modalities. Single-modality configurations (T1-only, T2-only, FLAIR-only), evaluated exclusively as ablation baselines, consistently underperformed relative to the fused model, further validating the benefits of multimodal integration. The use of U-Net-based segmentation to extract tumor-focused patches enhances detection reliability while maintaining computational efficiency suitable for deployment in clinical environments. The findings highlight the potential of multimodal fusion for robust, accurate tumor detection and position the proposed framework as a promising decision-support tool in neuro-oncology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S., D.G. and E.Y.; Methodology, B.S., D.G. and E.Y.; Modeling of software and Visualization, B.S., H.L. and E.Y.; Validation, B.S., H.L. and E.Y.; Writing, B.S., D.G. and E.Y.; and Supervision, B.S. and D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received internal funds from TAMIU University research grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The code and data used in this study are openly accessible via GitHub to enable transparency and reproducibility. Researchers and practitioners can find the full implementation—including architecture diagram scripts, training routines, and all relevant datasets—by visiting the following repository: https://github.com/bakhita11/BrainTumorDetection-CNN (accessed on 10 September 2025). The brain tumor MRI dataset used in this work is publicly available as the BraTS2020 dataset (Reference [1] is the actual link to the dataset). By providing open access to the source code and data, we facilitate independent validation, replication, and extension of our work by the broader scientific community.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Menze, B.; Bauer, A. Brain Tumor Segmentation (BraTS2020): Benchmarks and Dataset. Kaggle Datasets. June 2020. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/awsaf49/brats2020-training-data (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Taher, F.; Shoaib, M.R.; Emara, H.M.; Abdelwahab, K.M.; El-Samie, F.E.A.; Haweel, M.T. Efficient framework for brain tumor detection using different deep learning techniques. PLoS ONE 2022, 10, e959667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, J.; Zaidi, N.; Haghighat, M.; Roy, S.; Goyal, P.; Alavi, A.; Kumar, V. Multimodal Fusion Learning with Dual Attention for Medical Imaging. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Tucson, AZ, USA, 26 February–6 March 2025; pp. 1–10. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content/WACV2025/papers/Dhar_Multimodal_Fusion_Learning_with_Dual_Attention_for_Medical_Imaging_WACV_2025_paper.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Guo, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y. Multimodal MRI Image Decision Fusion-Based Network for Glioma Classification. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 12, 819673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Joshi, K.; Kanti, P.; Reshi, J.S.; Rawat, G.; Kumar, A. Brain Tumor Diagnosis using Image Fusion and Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Advances in Computing and Communication Engineering (ICACCE), Erode, India, 23–25 March 2023; pp. 123–128. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10104937 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Luo, F.; Wu, D.; Pino, L.R.; Ding, W. A Novel Multimodal Medical Image Fusion Framework with Edge Preservation and Transformer. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polinati, S.; Bavirisetti, D.P.; Rajesh, K.N.V.P.S.; Naik, G.R.; Dhuli, R. The Fusion of MRI and CT Medical Images Using Variational Mode Decomposition. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, C.; Peng, H.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, J.; Ding, W. A review of cancer data fusion methods based on deep learning. Inf. Fusion 2024, 108, 102361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiya, A.J.; Wani, N.; Ramani, M.; Kumar, A.; Pant, S.; Kotecha, K.; Kulkarni, A.; Al-Danakh, A. Optimized deep learning for brain tumor detection: A hybrid approach with attention mechanisms and clinical explainability. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, L.; Ren, Y. ResSAXU-Net for multimodal brain tumor segmentation from brain MRI. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9539. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-09539-1 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Deepak, S.; Ameer, P.M. Brain tumor classification using deep CNN features via transfer learning. Comput. Biol. Med. 2019, 111, 103345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Ghimire, K.; Kim, D.D.; Chandra, R.S.; Zhang, H.; Peng, J.; Han, B.; Huang, G.; Chen, Q.; Patel, S.; et al. Brain Tumor Segmentation for Multi-Modal MRI with Missing Information. J. Digit. Imaging 2023, 36, 2075–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, V.S.; Xydeas, C.S. Gradient-based multiresolution image fusion. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 13, 228–237. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1278337 (accessed on 10 September 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Yagmurlu, B.; Molleti, P.; Lee, R.; VanderPloeg, A.; Noor, H.; Bareja, R.; Li, Y.; Iv, M.; Itakura, H. Brain tumor segmentation using deep learning: High performance with minimized MRI data. Front. Radiol. 2025, 3, 1616293. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/radiology/articles/10.3389/fradi.2025.1616293/full (accessed on 10 September 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriram, I.J.S.G.; Sriram, S.V. Deep CNN-Based Multi-Grade Brain Tumor Classification with Enhanced Data Augmentation. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 232, 1414–1423. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877050925009494 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Chen, X.; Lin, X.; Shen, Q.; Qian, X. Combined spiral transformation and model-driven multi-modal deep learning scheme for automatic prediction of TP53 mutation in pancreatic cancer. Med. Image Anal. 2021, 40, 735–747. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9248055 (accessed on 10 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Francis, D.; Mathivanan, S.K.; Rajadurai, H.; Shivahare, B.D.; Shah, M.A. A hybrid deep CNN model for brain tumor image multi-classification. BMC Med. Imaging 2024, 24, 21. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/377532396_A_hybrid_deep_CNN_model_for_brain_tumor_image_multi-classification (accessed on 10 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zheng, J.; Li, P.; Lu, X.; Zhu, G.; Shen, P. An effective multimodal image fusion method using MRI and PET for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Front. Digit. Health 2021, 3, 637386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, C.; Xue, J.; Yuan, C. Multi channel fusion diffusion models for brain tumor MRI data augmentation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, T.; Xu, W. MMIF-AMIN: Adaptive Loss-Driven Multi-Scale Invertible Dense Network for Multimodal Medical Image Fusion. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.08679. Available online: https://arxiv.org/html/2508.08679v1 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Zhou, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Lu, H. Wavelet Attention is all you need in multimodal medical image fusion. Neurocomputing 2025, 2025, 131448. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0925231225021204 (accessed on 12 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tan, T.; Li, X.; Ye, T.; Wu, Y. Multiple Attention Channels Aggregated Network for Multimodal Medical Image Fusion. Med. Phys. 2025, 52, 2356–2374. Available online: https://aapm.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mp.17607 (accessed on 12 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Dharshini, S.; Geetha, S.; Arya, S.; Mekala, N.; Reshma, R.; Sasirekha, S.P. An Enhanced Brain Tumor Detection Scheme using a Hybrid Deep Learning Model. In Proceedings of the 2023 Second International Conference on Electronics and Renewable Systems (ICEARS), Tuticorin, India, 2–4 March 2023; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/10085267/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Smith, R.; Peterson, L.H. Fusion of MRI and CT images for brain tumor segmentation and classification. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 2710–2723. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2090447925004101 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Zhang, G.; Zhou, J.; He, G.; Zhu, H. Deep fusion of multi-modal features for brain tumor image segmentation. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R. A deep learning approach for brain tumor detection from MRI images. J. Med. Imaging 2021, 45, 120–128. Available online: https://peerj.com/articles/cs-2670/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Rao, J.; Chen, S.; He, F.; Li, Y. Enhanced Brain Tumor Segmentation Using CBAM-Integrated U-Net. Int. J. Biomed. Imaging 2025, 2025, 2149042. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/ijbi/2149042 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Saadi, A.; Aghamohammadi, M.K.; Pedada, G. Brain tumor segmentation with deep learning: Current approaches and future trends. J. Neurosci. Methods 2025, 393, 109965. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165027025000652 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, W. Advanced techniques for brain MRI processing and segmentation: A survey. Med. Image Anal. 2019, 56, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilakant, R.; Menon, H.P.; Vikram, K. A Survey on Advanced Segmentation Techniques for Brain MRI Image Segmentation. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2016, 6, 179–184. Available online: https://ijaseit.insightsociety.org/index.php/ijaseit/article/view/1271 (accessed on 10 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Hayat, M.; Iqbal, N.; Alarfaj, F.K.; Alkhalaf, S.; Alturise, F. Enhanced MRI brain tumor detection using deep learning in conjunction with explainable AI SHAP based diverse and multi feature analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14901. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-14901-4 (accessed on 10 September 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haris, T.S.T.A.; Kumar, D.S.V.R.; Sujatha, S.M. The role of generative adversarial networks in brain MRI: A scoping review. Insights Imaging 2020, 12, 755–763. Available online: https://insightsimaging.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s13244-022-01237-0 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Filho, L.M.S.; Santos, T.M.A.; Oliveira, M.S. A review of MRI segmentation techniques. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging, Barcelona, Spain, 11–13 October 2018; pp. 1–4. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281772814_A_REVIEW_ON_MRI_IMAGE_SEGMENTATION_TECHNIQUES (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Muksimova, S.; Umirzakova, S.; Iskhakova, N.; Khaitov, A.; Cho, Y.I. Advanced convolutional neural network with attention mechanism for Alzheimer’s disease classification using MRI. NeuroImage 2023, 285, 119982. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010482525004469?via%3Dihub (accessed on 10 September 2025). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).