Medium-Chain Fatty Acid Products Derived from Agriculture and Food Production Sidestreams Decrease Cattle Greenhouse Gas Emissions In Vitro

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Diet Composition and Analysis

2.2. Medium-Chain Fatty Acid Preparation

2.3. In Vitro Fermentation, Gas Collection, and Analyses

2.4. Volatile Fatty Acid Analysis

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Dry Matter Digestibility and pH

3.2. CH4 and CO2 Volume and Percentage

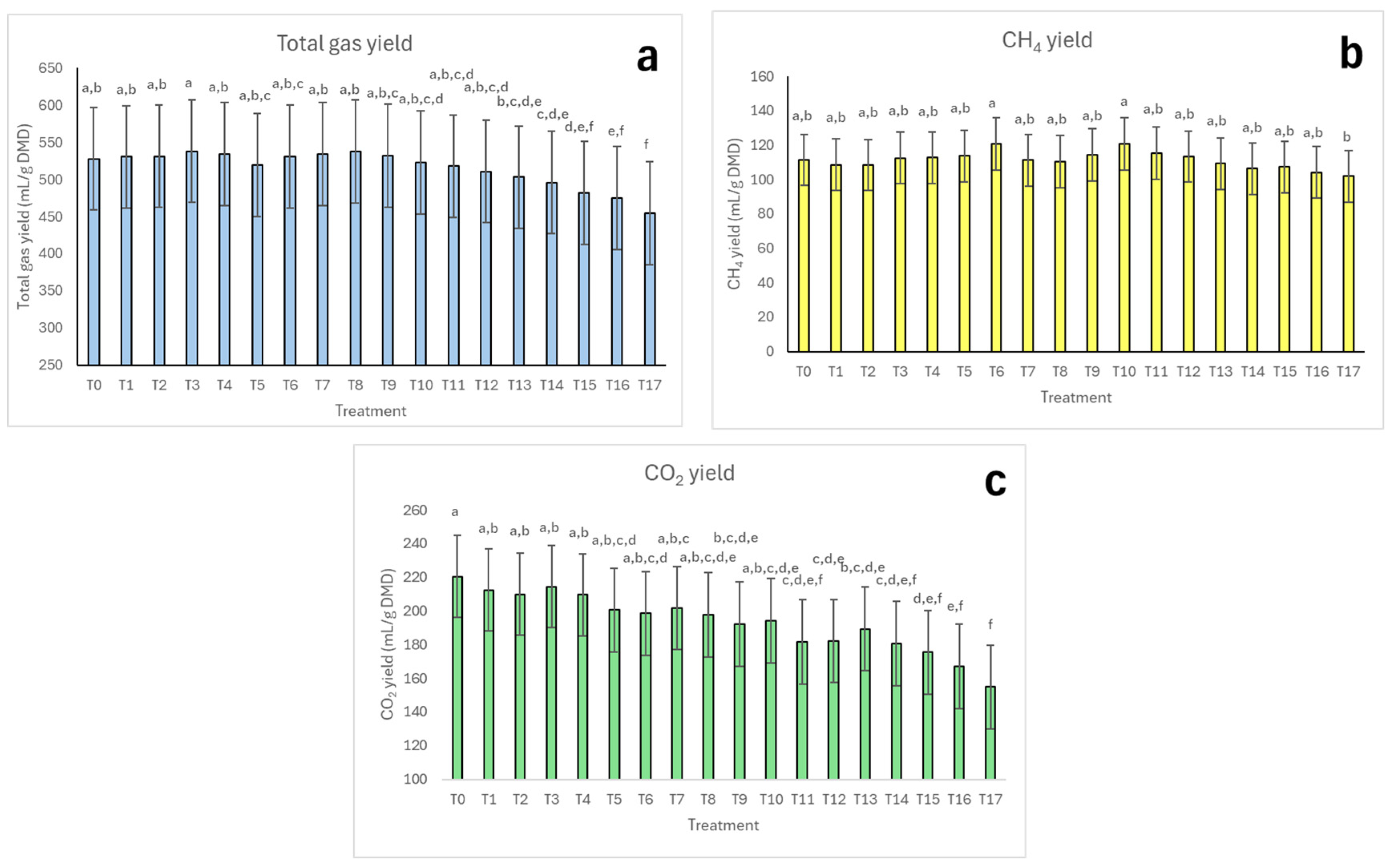

3.3. Total Gas, CH4, and CO2 Yields

3.4. Volatile Fatty Acids

4. Discussion

4.1. Diet Digestibility and pH

4.2. Gas Volume, Percentage, and Yield

4.3. Volatile Fatty Acid Production

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CH4 | Methane |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| VFA | Volatile fatty acid |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| DMD | Dry matter digestibility |

| 3-NOP | 3-nitrooxypropanol |

| MCFA | Medium-chain fatty acid |

| FR | Fast release |

| SR | Slow release |

| DM | Dry matter |

| DDG | Dried distiller’s grains |

| A:P | Acetate/propionate ratio |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acid |

| ADF | Acid detergent fiber |

| NDF | Neutral detergent fiber |

References

- Perez, H.G.; Stevenson, C.K.; Lourenco, J.M.; Callaway, T.R. Understanding Rumen Microbiology: An Overview. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.B. Rumen Microbiology and Its Role in Ruminant Nutrition; Department of Microbiology, Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, P.J. Tackling Climate Change Through Livestock: A Global Assessment of Emissions and Mitigation Opportunities; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013; ISBN 9789251079201. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K.A.; Johnson, D.E. Methane Emissions from Cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 1995, 73, 2483–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, J.A.; Richardson, E.C.; Herd, R.M.; Arthur, P.F. Potential for Selection to Improve Efficiency of Feed Use in Beef Cattle: A Review. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1999, 50, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin, K.A.; Ungerfeld, E.M.; Eckard, R.J.; Wang, M. Review: Fifty Years of Research on Rumen Methanogenesis: Lessons Learned and Future Challenges for Mitigation. Animal 2020, 14, S2–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-García, P.A.; Anderson, R.C.; Arévalos-Sánchez, M.M.; Rodríguez-Almeida, F.A.; Félix-Portillo, M.; Muro-Reyes, A.; Božić, A.K.; Arzola-Álvarez, C.; Corral-Luna, A. Astragallus Mollissimus Plant Extract: A Strategy to Reduce Ruminal Methanogenesis. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujani, S.; Piyasena, T.; Seresinhe, T.; Pathirana, I.; Gajaweera, C. Supplementation of Rice Straw (Oryza Sativa) with Exogenous Fibrolytic Enzymes Improves in Vitro Rumen Fermentation Characteristics. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2017, 41, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.; Kebreab, E. Recent Advances in Feed Additives with the Potential to Mitigate Enteric Methane Emissions from Ruminant Livestock. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2023, 78, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupo, M.R.; Ferraretto, L.F.; Nicholson, C.F. Effects of Feeding 3-Nitrooxypropanol for Methane Emissions Reduction on Income over Feed Costs in the United States. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 5061–5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Montoya, J.; De Campeneere, S.; Van Ranst, G.; Fievez, V. Interactions between Methane Mitigation Additives and Basal Substrates on in Vitro Methane and VFA Production. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2012, 176, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijaard, E.; Abrams, J.F.; Juffe-Bignoli, D.; Voigt, M.; Sheil, D. Coconut Oil, Conservation and the Conscientious Consumer. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R757–R758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijaard, E.; Brooks, T.M.; Carlson, K.M.; Slade, E.M.; Garcia-Ulloa, J.; Gaveau, D.L.A.; Lee, J.S.H.; Santika, T.; Juffe-Bignoli, D.; Struebig, M.J.; et al. The Environmental Impacts of Palm Oil in Context. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 1418–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Lee, S.Y. Microbial Production of Short-Chain Alkanes. Nature 2013, 502, 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Teixeira, P.G.; Pereira, R.; Chen, Y.; Siewers, V.; Nielsen, J. Multidimensional Engineering of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae for Efficient Synthesis of Medium-Chain Fatty Acids. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, N.; Taiwo, K.J.; Usack, J.G. Decarbonizing the Food System with Microbes and Carbon-Neutral Feedstocks. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 236, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angenent, L.T.; Richter, H.; Buckel, W.; Spirito, C.M.; Steinbusch, K.J.J.; Plugge, C.M.; Strik, D.P.B.T.B.; Grootscholten, T.I.M.; Buisman, C.J.N.; Hamelers, H.V.M. Chain Elongation with Reactor Microbiomes: Open-Culture Biotechnology to Produce Biochemicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 2796–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girotto, F.; Alibardi, L.; Cossu, R. Food Waste Generation and Industrial Uses: A Review. Waste Manag. 2015, 45, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenco, J.M.; Froetschel, M.A.; Segers, J.R.; Tucker, J.J.; Stewart, R.L. Utilization of Canola and Sunflower Meals as Replacements for Soybean Meal in a Corn Silage-Based Stocker System. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2017, 1, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; Bannink, A.; Dijkstra, J.; Kebreab, E.; Morgavi, D.P.; O’Kiely, P.; Reynolds, C.K.; Schwarm, A.; Shingfield, K.J.; Yu, Z.; et al. Design, Implementation and Interpretation of in vitro Batch Culture Experiments to Assess Enteric Methane Mitigation in Ruminants—A Review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2016, 216, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goering, H.K.; Van Soest, P.J. Forage Fiber Analyses; USDA Agricultural Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for Dietary Fiber, Neutral Detergent Fiber, and Nonstarch Polysaccharides in Relation to Animal Nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, T.J.; Hancock, D.W.; Tucker, J.J.; Maia, F.J.; Lourenco, J.M. Ensiling Alfalfa and Alfalfa–Bermudagrass with Ferulic Acid Esterase-Producing Microbial Inoculants. Crop Forage Turfgrass Manag. 2021, 7, e20093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, E.I. Studies on Ruminant Saliva 1. The Composition and Output of Sheep’s Saliva. Biochem. J. 1942, 36, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenco, J.M.; Callaway, T.R.; Kieran, T.J.; Glenn, T.C.; McCann, J.C.; Lawton Stewart, R. Analysis of the Rumen Microbiota of Beef Calves Supplemented during the Suckling Phase. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenco, J.M.; DiLorenzo, N.; Stelzleni, A.M.; Segers, J.R.; Stewart, R.L. Use of By-Product Feeds to Decrease Feed Cost While Maintaining Performance of Developing Beef Bulls. Prof. Anim. Sci. 2016, 32, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, D.D.; Ruiz-Moreno, M.; Ciriaco, F.M.; Kohmann, M.; Mercadante, V.R.G.; Lamb, G.C.; DiLorenzo, N. Effects of Chitosan on Nutrient Digestibility, Methane Emissions, and In Vitro Fermentation in Beef Cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 3539–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenco, J.M.; Kieran, T.J.; Seidel, D.S.; Glenn, T.C.; Da Silveira, M.F.; Callaway, T.R.; Stewart, R.L. Comparison of the Ruminal and Fecal Microbiotas in Beef Calves Supplemented or Not with Concentrate. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervajio, G. Fatty Acids and Derivatives from Coconut Oil. In Kirk-Othmer Chemical Technology of Cosmetics; Seidel, A., Ed.; Whiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 445–482. [Google Scholar]

- Dohme, F.; Machmüller, A.; Wasserfallen, A.; Kreuzer, M. Ruminal Methanogenesis as Influenced by Individual Fatty Acids Supplemented to Complete Ruminant Diets. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 32, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadroňová, M.; Šťovíček, A.; Jochová, K.; Výborná, A.; Tyrolová, Y.; Tichá, D.; Homolka, P.; Joch, M. Combined Effects of Nitrate and Medium-Chain Fatty Acids on Methane Production, Rumen Fermentation, and Rumen Bacterial Populations In Vitro. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ruchel, A.; Britos, A.; Alvarado, A.; Fernández-Ciganda, S.; Gadeyne, F.; Bustos, M.; Zunino, P.; Cajarville, C. Impact of Adding Tannins or Medium-Chain Fatty Acids in a Dairy Cow Diet on Variables of in Vitro Fermentation Using a Rumen Simulation Technique (RUSITEC) System. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2023, 305, 115763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdick, M.; Zhou, M.; Guan, L.L.; Oba, M. Effects of Medium-Chain Fatty Acid Supplementation on Performance and Rumen Fermentation of Lactating Holstein Dairy Cows. Animal 2022, 16, 100491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, K.; Nan, X.; Cai, M.; Yang, L.; Xiong, B.; Zhao, Y. Synergistic Effects of 3-Nitrooxypropanol with Fumarate in the Regulation of Propionate Formation and Methanogenesis in Dairy Cows In Vitro. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e0190821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, T.; Zheng, T.; Li, T.; Wu, B.; Li, T.; Bao, W.; Qin, W. The Effects of Different Doses of 3-NOP on Ruminal Fermentation Parameters, Methane Production, and the Microbiota of Lambs In Vitro. Fermentation 2024, 10, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, J.; Feng, X.; Yang, D.; Yang, M.; Zhou, J.; Geng, C. Effects of Medium-Chain Fatty Acids (MCFAs) on in Vitro Rumen Fermentation, Methane Production, and Nutrient Digestibility under Low- and High-Concentrate Diets. Anim. Sci. J. 2023, 94, e13818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliva, C.R.; Meile, L.; Cieślak, A.; Kreuzer, M.; Machmüller, A. Rumen Simulation Technique Study on the Interactions of Dietary Lauric and Myristic Acid Supplementation in Suppressing Ruminal Methanogenesis. Br. J. Nutr. 2004, 92, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elghandour, M.M.Y.; Vallejo, L.H.; Salem, A.Z.M.; Salem, M.Z.M.; Camacho, L.M.; Buendía, R.G.; Odongo, N.E. Effects of Schizochytrium Microalgae and Sunflower Oil as Sources of Unsaturated Fatty Acids for the Sustainable Mitigation of Ruminal Biogases Methane and Carbon Dioxide. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.F.O.; Terry, S.A.; Holman, D.B.; Breves, G.; Pereira, L.G.R.; Silva, A.G.M.; Chaves, A.V. Tucumã Oil Shifted Ruminal Fermentation, Reducing Methane Production and Altering the Microbiome but Decreased Substrate Digestibility within a Rusitec Fed a Mixed Hay—Concentrate Diet. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzola-Alvarez, C.; Ruiz-Barrera, O.; Castillo-Castillo, Y.; Ontiveros, M.; Fonseca, M.; Jones, B.W.; Smith, W.B.; Hume, M.E.; Harvey, R.; Poole, T.L.; et al. Effects in Air-Exposed Corn Silage of Medium Chain Fatty Acids on Select Spoilage Microbes, Zoonotic Pathogens, and in Vitro Rumen Fermentation. J. Environ. Sci. Health B 2023, 58, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, J.A.; Boyd, R.D.; Elrod, C.C. Medium-Chain Fatty Acids and Monoglycerides as Feed Additives for Pig Production: Towards Gut Health Improvement and Feed Pathogen Mitigation. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatopoulou, P.; Malkowski, J.; Conrado, L.; Brown, K.; Scarborough, M. Fermentation of Organic Residues to Beneficial Chemicals: A Review of Medium-Chain Fatty Acid Production. Processes 2020, 8, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo-Briones, R.; Xu, J.; Spirito, C.M.; Usack, J.G.; Trondsen, L.H.; Guzman, J.J.L.; Angenent, L.T. Near-Neutral pH Increased n-Caprylate Production in a Microbiome with Product Inhibition of Methanogenesis. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Diet for Trial 1 | Diet for Trials 2 & 3 | |

|---|---|---|

| Ingredient, % dry matter (DM) | ||

| Ground hay, % | 50 | 43 |

| Dried distiller’s grains, % | 13.5 | 15.7 |

| Ground corn, % | 36.2 | 41 |

| Mineral premix, % | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Nutrient, % DM | ||

| Dry matter, % | 92.7 | 90.4 |

| TDN, % | 69.2 | 67.8 |

| Crude protein, % | 11.9 | 12.4 |

| Fat, % | 3.94 | 3.83 |

| NFC, % | 37.5 | 38.6 |

| Fiber, % DM | ||

| ADF, % | 22.8 | 24.0 |

| NDF, % | 42.8 | 42.0 |

| Lignin, % | 3.76 | 4.6 |

| Minerals, % DM | ||

| Calcium, % | 0.86 | 0.94 |

| Phosphorus, % | 0.49 | 0.52 |

| Magnesium, % | 0.22 | 0.23 |

| Potassium, % | 1.52 | 1.07 |

| Sodium, % | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| Calculated Energy Values | ||

| NEM, Mcal/kg | 1.72 | 1.68 |

| NEG, Mcal/kg | 1.10 | 1.06 |

| NEL, Mcal/kg | 1.57 | 1.54 |

| No. of Bottles | Treatment | MCFA Product 1 | Trial |

|---|---|---|---|

| 44 | T0 | Control | 1, 2, 3 |

| 44 | T1 | C6 FR | 1, 2, 3 |

| 44 | T2 | C6 SR | 1, 2, 3 |

| 32 | T3 | C8 FR | 1, 2 |

| 32 | T4 | C8 SR | 1, 2 |

| 20 | T5 | C6 Salt | 1 |

| 20 | T6 | C8 Salt | 1 |

| 24 | T7 | C6 FR, C6 SR | 2, 3 |

| 12 | T8 | C6 FR, C8 FR | 2 |

| 12 | T9 | C6 FR, C8 SR | 2 |

| 12 | T10 | C6 SR, C8 FR | 2 |

| 12 | T11 | C6 SR, C8 SR | 2 |

| 24 | T12 | C8 FR, C8 SR | 2, 3 |

| 16 | T13 | C6 FR, C6 SR, C8 FR | 3 |

| 16 | T14 | C6 FR, C6 SR, C8 SR | 3 |

| 16 | T15 | C6 FR, C8 FR, C8 SR | 3 |

| 16 | T16 | C6 SR, C8 FR, C8 SR | 3 |

| 16 | T17 | C6 FR, C6 SR, C8 FR, C8 SR | 3 |

| Treatment | DMD (%) | pH |

|---|---|---|

| T0 (Control) | 46.89 a,b | 6.74 a,b,c |

| T1 | 47.93 a,b | 6.73 a,b,c,d |

| T2 | 47.80 a,b | 6.74 a,b,c,d |

| T3 | 47.23 a,b | 6.74 a,b,c,d |

| T4 | 47.61 a,b | 6.73 a,b,c,d |

| T5 | 48.40 a,b | 6.74 a,b,c,d |

| T6 | 46.13 b | 6.75 a |

| T7 | 47.95 a,b | 6.73 c,d |

| T8 | 47.61 a,b | 6.72 c,d |

| T9 | 46.63 a,b | 6.72 c,d |

| T10 | 45.94 a,b | 6.73 b,c,d |

| T11 | 46.75 a,b | 6.73 a,b,c,d |

| T12 | 47.32 a,b | 6.73 c,d |

| T13 | 49.52 a,b | 6.72 d |

| T14 | 48.33 a,b | 6.73 a,b,c,d |

| T15 | 48.24 a,b | 6.73 a,b,c,d |

| T16 | 49.74 a | 6.74 a,b,c |

| T17 | 47.85 a,b | 6.75 a,b |

| p-value 1 | 0.02 | <0.001 |

| Treatment | Total Gas Collected (mL) | CH4 (%) | CO2 (%) | CH4 (mL) | CO2 (mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 (Control) | 114.8 a,b | 21.22 b,c | 42.11 a | 24.05 | 47.06 a |

| T1 | 116.3 a | 20.31 c | 40.03 b | 23.66 | 45.52 a,b |

| T2 | 115.3 a,b | 20.33 c | 39.90 b | 23.53 | 44.91 a,b |

| T3 | 116.0 a,b | 20.68 b,c | 40.06 a,b | 24.21 | 45.62 a,b |

| T4 | 115.7 a,b | 20.94 b,c | 39.23 b,c | 24.23 | 44.43 a,b,c |

| T5 | 113.1 a,b | 22.47 a,b | 38.55 b,c,d | 24.62 | 42.78 a,b,c,d |

| T6 | 113.1 a,b | 23.39 a | 36.70 c,d | 25.55 | 41.22 b,c,d,e |

| T7 | 117.1 a | 20.77 b,c | 38.21 b,c,d | 24.63 | 44.07 a,b,c |

| T8 | 118.1 a | 20.43 b,c | 37.27 b,c,d | 24.42 | 43.30 a,b,c,d |

| T9 | 113.7 a,b | 21.31 a,b,c | 36.56 c,d | 24.16 | 40.49 b,c,d,e |

| T10 | 112.3 a,b,c | 22.49 a,b,c | 37.05 b,c,d | 25.01 | 40.30 b,c,d,e |

| T11 | 111.2 a,b,c | 22.13 a,b,c | 35.76 d | 24.18 | 38.27 d,e |

| T12 | 111.0 a,b | 22.02 a,b,c | 36.40 d | 24.39 | 39.49 d,e |

| T13 | 117.0 a | 21.53 a,b,c | 38.36 b,c,d | 25.54 | 43.65 a,b,c,d |

| T14 | 112.4 a,b | 21.25 a,b,c | 37.28 b,c,d | 24.33 | 40.63 b,c,d,e |

| T15 | 108.9 b,c | 21.99 a,b,c | 37.33 b,c,d | 24.77 | 39.87 c,d,e |

| T16 | 112.2 a,b | 21.63 a,b,c | 36.20 c,d | 24.89 | 39.13 c,d,e |

| T17 | 103.4 c | 21.96 a,b,c | 35.30 d | 23.63 | 35.32 e |

| p-value 1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.42 | <0.001 |

| Treatment | Total VFA (mM) | Acetate MP | Propionate MP | Isobutyrate MP | Butyrate MP | Isovalerate MP | Valerate MP | Caproate MP | A:P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 (Control) | 74.78 a | 60.54 a,b | 22.30 a | 0.96 c,d | 12.38 c,d | 1.76 a,b,c | 1.34 | 0.72 e | 2.73 c |

| T1 | 75.69 a | 60.54 a,b | 22.30 a | 0.95 d | 12.32 d | 1.75 b,c | 1.33 | 0.82 d,e | 2.73 c |

| T2 | 74.39 a | 60.44 b | 22.08 a,b | 0.96 c,d | 12.39 c,d | 1.77 a,b | 1.32 | 1.02 c | 2.75 c |

| T3 | 71.20 b | 60.29 b | 22.12 a,b | 0.97 b,c,d | 12.46 c,d | 1.78 a,b,c | 1.33 | 1.07 c | 2.74 c |

| T4 | 75.75 a | 60.40 b | 21.78 b,c | 0.97 b,c,d | 12.69 b,c | 1.78 a | 1.34 | 1.03 c | 2.78 b,c |

| T5 | 74.14 a,b | 60.30 b | 21.27 c | 0.98 a,b | 12.89 a,b | 1.78 a,b | 1.35 | 1.45 a | 2.85 b |

| T6 | 73.52 a,b | 60.91 a | 20.41 d | 1.00 a | 13.25 a | 1.80 a | 1.32 | 1.33 a,b | 3.01 a |

| T7 | 74.92 a,b | 60.33 b | 21.76 b,c | 0.97 b,c | 12.51 b,c,d | 1.78 a,b | 1.31 | 1.06 c | 2.79 b,c |

| T8 | 75.68 a,b | 60.62 a,b | 21.68 a,b,c | 0.97 a,b,c,d | 12.62 b,c,d | 1.78 a,b,c | 1.28 | 1.06 b,c | 2.82 b,c |

| T9 | 75.87 a,b | 60.56 a,b | 21.68 a,b,c | 0.97 a,b,c,d | 12.65 b,c,d | 1.78 a,b,c | 1.29 | 1.13 b,c | 2.82 b,c |

| T10 | 74.68 a,b | 60.51 a,b | 21.78 a,b,c | 0.97 a,b,c,d | 12.60 b,c,d | 1.78 a,b,c | 1.30 | 1.07 b,c | 2.80 b,c |

| T11 | 74.26 a,b | 60.48 a,b | 21.85 a,b,c | 0.96 b,c,d | 12.58 b,c,d | 1.76 a,b,c | 1.29 | 1.11 b,c | 2.79 b,c |

| T12 | 75.47 a | 60.41 a,b | 21.92 a,b | 0.96 b,c,d | 12.40 c,d | 1.75 a,b,c | 1.31 | 1.13 b,c | 2.78 b,c |

| T13 | 76.24 a | 60.22 b | 22.32 a,b | 0.97 b,c,d | 12.33 c,d | 1.78 a,b,c | 1.34 | 1.02 c,d | 2.72 c |

| T14 | 75.61 a,b | 60.31 a,b | 22.10 a,b | 0.96 b,c,d | 12.43 b,c,d | 1.77 a,b,c | 1.36 | 1.03 c | 2.75 c |

| T15 | 75.31 a,b | 60.34 a,b | 21.94 a,b,c | 0.96 b,c,d | 12.35 c,d | 1.75 a,b,c | 1.37 | 1.101 b,c | 2.77 b,c |

| T16 | 76.36 a | 60.70 a,b | 22.10 a,b | 0.96 b,c,d | 12.22 c,d | 1.73 c | 1.30 | 0.96 c,d | 2.76 b,c |

| T17 | 74.88 a,b | 60.42 a,b | 22.19 a,b | 0.96 c,d | 12.39 b,c,d | 1.76 a,b,c | 1.34 | 0.91 c,d,e | 2.74 c |

| p-value 1 | 0.003 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.24 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arias, N.; Simeonidis, K.; Rooks, A.H.; Dycus, M.M.; Zhou, H.; Pinotti, L.; Pastorelli, G.; Usack, J.G.; Lourenco, J.M. Medium-Chain Fatty Acid Products Derived from Agriculture and Food Production Sidestreams Decrease Cattle Greenhouse Gas Emissions In Vitro. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13154. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413154

Arias N, Simeonidis K, Rooks AH, Dycus MM, Zhou H, Pinotti L, Pastorelli G, Usack JG, Lourenco JM. Medium-Chain Fatty Acid Products Derived from Agriculture and Food Production Sidestreams Decrease Cattle Greenhouse Gas Emissions In Vitro. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13154. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413154

Chicago/Turabian StyleArias, Natalie, Kalliroi Simeonidis, Alexis H. Rooks, Madison M. Dycus, Hualu Zhou, Luciano Pinotti, Grazia Pastorelli, Joseph G. Usack, and Jeferson M. Lourenco. 2025. "Medium-Chain Fatty Acid Products Derived from Agriculture and Food Production Sidestreams Decrease Cattle Greenhouse Gas Emissions In Vitro" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13154. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413154

APA StyleArias, N., Simeonidis, K., Rooks, A. H., Dycus, M. M., Zhou, H., Pinotti, L., Pastorelli, G., Usack, J. G., & Lourenco, J. M. (2025). Medium-Chain Fatty Acid Products Derived from Agriculture and Food Production Sidestreams Decrease Cattle Greenhouse Gas Emissions In Vitro. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13154. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413154