Abstract

Accurate 3D medical image segmentation is crucial for knowledge-driven clinical decision-making and computer-aided diagnosis. However, current deep learning methods often fail to effectively integrate local structural details from Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) with global semantic context from Transformers due to semantic inconsistency and poor cross-scale feature alignment. To address this, Progressive Query Aggregation Network (PQAN), a novel framework that incorporates knowledge-guided feature interaction mechanisms, is proposed. PQAN employs two complementary query modules: Structural Feature Query, which uses anatomical morphology for boundary-aware representation, and Content Feature Query, which enhances semantic alignment between encoding and decoding stages. To enhance texture perception, a Texture Attention (TA) module based on Sobel operators adds directional edge awareness and fine-detail enhancement. Moreover, a Progressive Aggregation Strategy with Forward and Backward Cross-Stage Attention gradually aligns and refines multi-scale features, thereby reducing semantic deviations during CNN-Transformer fusion. Experiments on public benchmarks demonstrate that PQAN outperforms state-of-the-art models in both global accuracy and boundary segmentation. On the BTCV and FLARE datasets, PQAN had average Dice scores of 0.926 and 0.816, respectively. These results demonstrate PQAN’s ability to capture complex anatomical structures, small targets, and ambiguous organ boundaries, resulting in an interpretable and scalable solution for real-world clinical deployment.

1. Introduction

Medical image segmentation is a critical step in medical image analysis, aiming to automatically and accurately extract anatomical structures or lesion regions from medical images. In clinical practice, physicians often need to conduct preliminary assessments of medical images before radiologists can issue formal diagnostic reports. This requirement is especially urgent in the treatment of critically ill and emergency patients. However, severe diseases, trauma, and certain chronic conditions frequently cause significant changes in organ anatomy, making image interpretation more complex and difficult for physicians. Furthermore, while imaging examinations help rehabilitation specialists accurately assess the long-term prognosis of patients with functional impairments, a variety of confounding factors may still influence diagnostic accuracy. Additionally, limitations in frontline clinical equipment and physicians’ lack of experience with image interpretation may have an impact on diagnosis accuracy and timeliness, potentially delaying treatment and negatively affecting patient outcomes. Therefore, medical image segmentation technology plays a crucial role in assisting clinical diagnosis and surgical planning [1,2,3]. In recent years, as deep learning has advanced rapidly, 3D semantic segmentation models based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [4,5] and Transformers [6,7] have demonstrated exceptional performance in medical image processing. These models not only allow for accurate segmentation of anatomical structures and lesion regions, but they also significantly improve diagnostic efficiency. They provide strong support for early disease screening, precision treatment, and dynamic disease assessment, significantly increasing the intelligence and accuracy of clinical workflows [8,9,10].

However, existing medical image segmentation methods still face several challenges in practical applications. Previous approaches relied heavily on CNN-based network architectures for segmentation, which excel at capturing local details and texture information but struggle to effectively model long-range dependencies [11,12]. To address this issue, some studies have attempted to integrate Transformer architectures, relying on their self-attention mechanism to better capture global contextual information [13,14,15]. Nevertheless, these approaches often encounter semantic incompatibility when fusing CNN and Transformer features. Specifically, semantic deviations frequently occur during cross-scale feature fusion, resulting in suboptimal segmentation accuracy, especially for fine structures, complex anatomical boundaries, and small target regions [16,17]. Additionally, some studies have proposed using Non-Local mechanisms [18] as an alternative to Transformers to reduce computational costs and improve CNN compatibility [19,20,21]. However, while Non-Local mechanisms help to mitigate Transformers’ high computational overhead, they have significant limitations in capturing complex texture information, target structural features, and cross-scale information interaction. As a result, they struggle to distinguish structural details and boundary features in medical images [22,23]. These limitations are especially noticeable in medical image segmentation tasks, where high-precision structural representation is required. In summary, while CNNs and Transformers each have distinct advantages, excelling at capturing local details and modeling global semantic context, respectively, existing research has struggled to achieve stable and effective deep integration between the two. Semantic inconsistency, feature misalignment, and structural detail loss are especially common during cross-scale feature interaction, severely limiting segmentation performance for complex anatomical structures, small-volume targets, and ambiguous boundaries. Therefore, developing a new fusion mechanism that fully leverages the complementary strengths of CNNs and Transformers, while ensuring semantic consistency and precise feature alignment, has emerged as a critical challenge in 3D medical image segmentation and serves as the primary motivation for this study.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a Progressive Query Aggregation Network (PQAN). The core of PQAN is the design of two feature query mechanisms: Structural Feature Query and Content Feature Query, which allow for precise feature interaction and fusion at various stages of the encoding–decoding network. Specifically, Structural Feature Query focuses on extracting structural contours and boundary features of target regions. By introducing the Backward Cross-stage Attention (BCA) mechanism, PQAN effectively propagates deep-stage global structural information to the shallow feature space, compensating for the lack of fine-structure representation in traditional CNN-Transformer fusion. Meanwhile, Content Feature Query uses randomly initialized and learnable query features to actively select and align features at various scales using the Forward Cross-stage Attention (FCA) mechanism, gradually aggregating multi-scale semantic information. This design effectively addresses the semantic inconsistency and deviation issues encountered in traditional cross-scale fusion methods, significantly improving semantic compatibility between features at different scales. This study also introduces a Texture Attention (TA) mechanism that explicitly captures local texture details and edge information within feature maps using horizontal and vertical Sobel operators. This enhancement improves the feature representation of complex local structures in medical images, addressing the limitations of existing methods for local detail perception. Additionally, a Progressive Aggregation Strategy is proposed, which uses the FCA mechanism to gradually align and integrate high-level semantic information with low-level features. This hierarchical integration process ensures that global contextual information is gradually incorporated into local features, reinforcing semantic consistency and improving the precise perception of small target regions and complex anatomical structures. Consequently, PQAN effectively achieves multi-scale semantic feature fusion while retaining the benefits of both CNN and Transformer architectures.

In summary, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- (1)

- A Texture Attention (TA) mechanism is developed, which employs the Sobel operator to effectively capture local texture details, improving the structural representation capability of feature maps.

- (2)

- Structural Feature Query and Content Feature Query mechanisms are proposed to allow for precise interaction between structural and semantic information at various stages.

- (3)

- Mechanisms for forward cross-stage attention (FCA) and backward cross-stage attention (BCA) are introduced in order to achieve precise interaction and fusion of multi-scale features.

- (4)

- A Progressive Aggregation Strategy is developed to gradually integrate semantic features at various scales, effectively reducing semantic deviations in cross-scale fusion.

2. Related Work

2.1. Feature Fusion Paradigms of CNN and Transformer

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) were the primary tools used in early medical image segmentation. For instance, U-Net, which is known for its simple structure and high performance, has been widely used in the medical imaging domain. To further enhance the feature extraction capability of CNN models, Shu et al. [4] proposed the CSCA U-Net network, which includes a Channel and Spatial Composite Attention (CSCA) mechanism in the network bottleneck layer. However, CNNs inherently suffer from a limited receptive field, making them inadequate for capturing long-range dependencies.

With the introduction of Transformers in natural image processing, Perera et al. [24] pioneered the use of Vision Transformers in 3D medical image segmentation tasks, proposing the lightweight SegFormer3D model. This model enhances global semantic perception by utilizing a multi-scale Transformer structure, while reducing computational complexity and improving generalization. Despite Transformers’ superior global context modeling capabilities, they are still computationally expensive, and their fixed attention windows limit flexible long-range information interaction. To address these issues, Fu et al. [25] developed the SSTrans-Net model, which uses Smart Sliding Window Multi-head Self-Attention (SSW-MSA) to selectively capture long-range dependencies across different channels, thereby improving segmentation accuracy and computational efficiency in multi-organ segmentation tasks.

Furthermore, to balance CNNs’ local feature representation and Transformers’ global context modeling capability, Liu et al. [26] proposed CSWin-UNet, which embeds a Cross-shaped Window Self-Attention mechanism within the U-Net framework and designs a content-aware feature reassembly decoder. However, these methods still lack sufficient semantic information fusion.

Recently, Wu et al. [27] proposed the integration of Diffusion Probabilistic Models with Transformer mechanisms, introducing the MedSegDiff-V2 framework. Using diffusion models, they improved feature generalization and achieved precise feature fusion through Transformer mechanisms, effectively addressing the semantic bias issue in traditional CNN-Transformer hybrid models. However, such methods have limitations for fine-grained segmentation of complex anatomical structures. Consequently, resolving the semantic inconsistency of cross-scale features in CNN-Transformer fusion remains a critical research focus.

2.2. Cross-Scale Semantic Alignment Methods

Researchers have proposed a number of cross-scale semantic alignment strategies to address the semantic inconsistency of cross-scale features in CNN-Transformer fusion. Benabid et al. [28] highlighted the issue of information redundancy in U-Net architectures when integrating multi-scale features, which impedes the effective capture of discriminative features near target boundaries. They proposed a cross-stage attention mechanism that reduces redundant information while achieving precise multi-scale feature fusion. They also introduced Bidirectional Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (BiASPP) to improve the network’s perception of multiscale targets. Despite achieving promising cross-scale semantic fusion, this method has limitations in handling fine anatomical boundaries.

To address this limitation, Sui et al. [29] proposed a cross-scale prior-aware Transformer decoder that combines a cross-scale prior perception module and a pattern-aware module to improve the model’s ability to capture target boundary information while suppressing background noise. This significantly improved the efficiency of semantic fusion across different scales. However, these approaches still face challenges in precisely aligning semantic information when dealing with medical images containing small lesion regions. Dai et al. [30] addressed the problem of small target region information loss in medical images by developing a Transformer-CNN hybrid network specifically for small target segmentation. While this method effectively compensates for the limitations of traditional CNN models in small target recognition, it still struggles with complex texture regions. To achieve more precise multi-scale semantic feature fusion, Wang et al. [31] proposed CRMEFNet, which combines refinement and exploration fusion strategies. This method uses a multi-scale aggregation attention mechanism to enable adaptive cross-level feature fusion, which significantly improves the ability to differentiate between target and background regions. However, further improvements are needed in spatial structural representation. Building on these advancements, Sun et al. [32] introduced the CasUNeXt network, which employs a cascaded Transformer architecture and incorporates an inter-scale interaction channel attention mechanism, allowing for effective cross-scale feature aggregation and significantly improving multi-scale contextual data integration.

Unlike existing CNN–Transformer hybrid architectures, structure-aware models, and cross-scale attention methods, the proposed Progressive Query Aggregation Network (PQAN) introduces a new paradigm for feature interaction. PQAN uses structural and content feature queries to enable clearer and more semantically consistent interactions between different encoding and decoding stages, rather than simply concatenating CNN and Transformer features. At the same time, to compensate for the limitations of structure-aware methods in texture modeling, PQAN includes a Texture Attention module that improves perception of local texture details and boundary information. In addition, by combining forward and backward cross-stage attention with a progressive aggregation strategy, PQAN achieves more effective cross-scale semantic alignment and alleviates semantic deviations during feature fusion.

3. Proposed Method

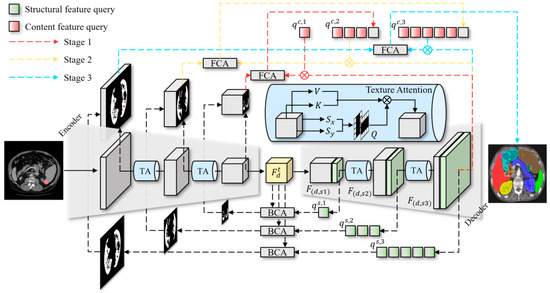

In medical image segmentation tasks, we aim to predict the segmentation mask from the input image , i.e., learning a mapping function . To achieve this, we propose the Progressive Query Aggregation Network (PQAN), which uses an encoder–decoder architecture and includes cross-stage feature query and attention mechanisms. The overall pipeline of PQAN is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The pipeline of the Progressive Query Aggregation Network.

Specifically, the input image is first processed by the encoder and decoder to extract multiscale feature representations . To effectively capture local texture details within feature maps, each stage utilizes the Texture Attention (TA) mechanism, which enhances the feature representations as . During the decoding phase, we introduce two query mechanisms: Structural Feature Query and Content Feature Query . The Structural Feature Query is designed to capture morphological characteristics of the target region. It extracts critical structural information from the encoder through the Backward Cross-stage Attention (BCA) mechanism, defined as . Subsequently, a structure-aware mask is computed using the Structural Feature Query ( ), which enhances the boundary and structural information of the segmentation target. Additionally, the Content Feature Query achieves alignment and fusion of multi-scale features using the Forward Cross-stage Attention (FCA) mechanism, expressed as . This mechanism enables the progressive propagation of high-level semantic information toward lower levels. At each decoding stage, the aligned features from the previous stage serve as the content query for the current stage . This process gradually refines and aggregates features, reducing semantic deviations during cross-scale feature fusion. Finally, the predicted segmentation mask is generated as . This approach enhances segmentation accuracy of complex anatomical structures by gradually aggregating multi-scale semantic features while maintaining structural integrity.

3.1. Texture Attention and Structural Features

To effectively enhance the local details and structural information in feature maps, we design the Texture Attention (TA) mechanism and a structural feature extraction method. Specifically, for an input feature map , we first apply two independent convolutional mapping layers to project it into feature representations and , which are formulated as and , where and denote the respective convolution operations.

Based on this, we employ horizontal Sobel operator and vertical Sobel operator to convolve the feature map , capturing its edge and texture details, yielding two texture feature maps and . These two texture feature maps are then concatenated along the channel dimension and subsequently passed through a convolutional layer for dimensionality reduction to obtain the query feature , as expressed in Equation (1):

where represents the dimensionality reduction convolutional layer, and operator [; ] denotes channel-wise concatenation. After obtaining features , and , the standard attention computation is applied to generate the texture attention output, which is formulated as follows:

where denotes the channel dimension of the query and key features, and is used for normalizing the attention weights. The SoftMax function is applied along the row dimension to produce the enhanced texture attention representation .

In the decoder, to further capture rich structural information from the image, we extract structural features based on the feature map. Given an input feature map , we first compute a spatial similarity matrix , where each element in matrix represents the similarity relationship between spatial nodes.

Next, matrix is rearranged along both the row and column dimensions to construct structural feature maps and . Furthermore, and are concatenated along the channel dimension and a convolutional layer is applied for dimensionality reduction to obtain the final global structural feature representation, as defined in Equation (3):

where represents the dimensionality reduction convolutional layer. The obtained structural feature representation encapsulates global structural information, effectively enhancing the decoder’s capability to perceive target region boundaries and morphological details.

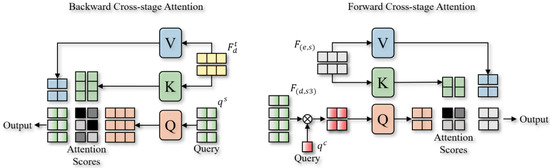

3.2. Cross-Stage Attention

To achieve effective feature fusion across different network stages, a Cross-Stage Attention (CSA) mechanism is developed. The core idea is to use Query-based decomposition to divide large-scale feature maps and align them with features from other stages through progressive aggregation. The detailed process is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The pipeline of Backward Cross-Stage Attention and Forward Cross-Stage Attention.

To achieve feature alignment and fusion in a progressive refinement manner, Cross-Stage Attention, in contrast to conventional cross-attention mechanisms, explicitly introduces Feature Queries to actively select and decompose relationships across different stages. Specifically, two cross-stage attention mechanisms are designed: Backward Cross-Stage Attention (BCA) and Forward Cross-Stage Attention (FCA). The BCA mechanism aims to propagate deep-stage structural information effectively to the shallow stages, ensuring precise structural feature transmission. Given a Structural Feature Query extracted from deep layers, we first map the intermediate-stage feature map into Key (K) and Value (V) spaces and compute multi-scale attention scores is formulated as follows:

where and represent linear projection operations, is the intermediate-stage feature map, and is the feature dimension with used for attention weight normalization. Next, we project the attention-weighted features back to the original spatial resolution and apply channel-wise compression to obtain a Structure-Aware Mask (G), as stated in Equation (5):

where represents the Value transformation matrix, is the final feature compression convolutional layer, and is the Sigmoid activation function, which generates the structure-aware mask .

In contrast to BCA, the FCA mechanism utilizes a randomly initialized, trainable Content Feature Query () to select and aggregate content features from feature maps at different scales. The entire aggregation process is divided into three stages. In the first stage, we consider the large-scale decoder feature map and the small-scale encoder feature map, and perform content selection through attention computation as follows:

where , and are linear projection operations applied to the Query, Key, and Value features, respectively. The selected feature is then mapped to the same feature space as the small-scale encoder feature for progressive aggregation, as formulated in Equation (7):

In the second stage, to match the number of Content Feature Queries with the medium-scale feature map , we take the previously aggregated feature map as the new query feature and randomly generate additional queries to match the required quantity, as indicated in Equation (8):

Similarly, we gradually improve features in the second and third stages through progressive aggregation and attention-based selection, allowing cross-scale feature alignment. This allows high-level semantic information to propagate and refine progressively toward lower levels. Ultimately, the decoder generates the final semantic segmentation output by decoding the feature map from the third stage.

3.3. Loss Function

To effectively train the proposed Progressive Query Aggregation Network (PQAN), we design a jointly supervised loss function. Our overall loss function, which ensures accurate segmentation and efficient perception of complex anatomical structures in medical images, is specifically composed of three components: Structure-Aware Loss (Structure Loss) [33], Dice Loss [34], and Cross-Entropy Loss [35].

To enhance the model’s learning of target boundaries and structural information, we employ the Structure Loss, which optimizes the difference between the generated structure-aware mask and the ground-truth mask . The Structure Loss is defined as follows:

where represents the structure-aware mask output by the model, is the ground-truth mask, and represents the spatial dimensions of the mask. Structure Loss effectively captures the importance of edge regions, enhancing the model’s sensitivity to target contour features.

To further optimize the overall segmentation performance, we incorporate the Cross-Entropy Loss, widely used in semantic segmentation tasks, which is defined in Equation (10):

where represents the predicted segmentation mask, is the ground-truth mask, and denotes the number of pixels. By ensuring efficient pixel-level classification optimization, Cross-Entropy Loss improves the model’s capacity to distinguish between foreground and background.

To further improve the segmentation accuracy of foreground regions in medical images, we introduce the Dice Loss, which is defined as follows:

where is a small constant to prevent division by zero. The segmentation accuracy of small target regions is significantly enhanced by the addition of Dice Loss, especially in medical images where foreground-background imbalance is a common issue.

Finally, the overall loss function is optimized by a weighted combination of the three loss functions, as defined in Equation (12):

where represents the final optimized loss function, and and are weight coefficients for the different loss functions. The model is urged to more precisely capture boundary, content, and structural information through joint optimization, significantly enhancing the final semantic segmentation performance.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Environment and Setup

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed Progressive Query Aggregation Network (PQAN), we conduct a series of experiments. All experiments are performed on an Ubuntu 20.04 operating system. The server is equipped with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6240 CPU @ 2.60 GHz processor, 256 GB of RAM, and two NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPUs with 24 GB memory. We use PyTorch 1.10.0 and Python 3.8 for the software environment in which we conduct our experiments.

In terms of hyperparameter settings, we train the model for 200 epochs. To optimize the model, we use the AdamW optimizer, with an initial learning rate of 0.0001 and a weight decay coefficient of 0.01. Additionally, we adopt the Cosine Annealing Learning Rate Scheduler to stabilize the training process and accelerate convergence. The Texture Attention (TA) mechanism in PQAN uses a Sobel operator kernel size of 3 × 3 with padding = 1. For the loss function, the weight coefficients of Cross-Entropy Loss , Dice Loss , and Structure Loss are set to 1.0, 1.0, and 0.5, respectively. During training, all 3D images are resized to 128 × 128 × 128, and the batch size is set to 4.

4.2. Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

Two publicly accessible medical image segmentation datasets, BTCV [36] and FLARE [37], are used in our experiments. The BTCV dataset consists of 30 contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scans, with each case meticulously annotated for 13 abdominal organs by professionals at Vanderbilt University Medical Center under the supervision of clinical radiologists. There are 80–225 slices in each CT scan volume, each with a thickness of 1–6 mm and a resolution of 512 × 512 pixels. During preprocessing, image intensities within the range [−1000, 1000] Hounsfield Units (HU) are normalized and mapped to [0, 1]. Additionally, every image is resized to 1.0 mm isotropic voxel spacing. A single-channel 3D semantic segmentation problem with 13 categories is used to formulate the multi-organ segmentation task on BTCV. The FLARE dataset is provided by the organizers of the abdominal organ segmentation challenge and includes 13 abdominal organs, consisting of 2000 unlabeled cases and 50 labeled cases for model training and evaluation. We used all 50 labeled cases and the first 1000 unlabeled cases in this study. In order to improve the model’s initial feature representation capability, we used the unlabeled data for unsupervised pre-training. We employed an unsupervised learning strategy based on reconstruction and consistency constraints, enabling the model to learn the underlying structural features and anatomical priors of abdominal CT images without any annotations. During the unsupervised pre-training phase, we updated only the parameters of the encoder and decoder within the backbone network, and the features—without passing through any additional modules—were directly used for image reconstruction. This design ensured that the backbone network could sufficiently learn effective and stable feature representations. Specifically, the model was optimized by minimizing the reconstruction error, where the reconstruction loss was defined as an L2 loss, encouraging the decoder to faithfully reconstruct structures consistent with the input images.

Subsequently, the 50 labeled cases were divided into 40 for supervised training and 10 for performance evaluation. The model gains greater feature extraction skills prior to moving on to the supervised learning phase by utilizing the unsupervised pre-training on unlabeled data. This significantly improves the model’s segmentation and convergence stability on the labeled dataset.

To quantitatively assess segmentation performance, we adopt the Dice Similarity Coefficient (Dice Score), which is widely used in medical image segmentation tasks. The Dice Score effectively measures the overlap between the segmentation result and the ground truth, and is defined as follows:

where represents the predicted segmentation, and denotes the ground-truth mask. A Dice score closer to 1 indicates higher segmentation accuracy.

4.3. Results and Analysis

4.3.1. Ablation Study

We perform ablation experiments by gradually eliminating the Texture Attention (TA) mechanism, Structural and Content Feature Queries (Query), Forward and Backward Cross-Stage Attention (FCA/BCA), and the Progressive Aggregation Strategy (Prog. Agg) in order to assess the contribution of each module in PQAN. The segmentation performance of each model is evaluated across several organs, and Table 1 shows how various ablated models performed on the BTCV dataset in comparison to the full PQAN model.

Table 1.

Impact of different PQAN modules on segmentation performance.

It is evident that the complete PQAN model achieves the best performance across all organs, with an average Dice score of 0.926. When the Texture Attention (TA) mechanism is removed, the model’s ability to capture local texture and edge information is weakened, leading to a drop in average Dice to 0.918. By eliminating the Structural and Content Feature Queries, the average Dice score drops to 0.912 due to imprecise feature alignment and fusion across stages, underscoring the critical role that cross-stage feature interaction plays in improving semantic consistency. The absence of Forward and Backward Cross-Stage Attention (FCA/BCA) significantly weakens multi-scale feature fusion, causing the average Dice to drop to 0.910. Moreover, the average Dice drops to 0.908 when the Progressive Aggregation Strategy is eliminated due to a significant reduction in the ability to gradually align small target regions and complex structures. Specifically, the removal of TA results in blurred edges in organs such as the gallbladder and pancreas. The lack of Structural and Content Feature Queries introduces semantic inconsistencies during cross-stage feature interaction. The segmentation performance of small target organs is adversely affected by the removal of the Progressive Aggregation Strategy, which restricts top-down information propagation and fine-grained alignment, and the lack of FCA/BCA results in inadequate multi-scale feature fusion.

In addition, we conducted a statistical significance analysis to compare the performance differences between each ablation setting and the complete PQAN model. The results demonstrate that eliminating any module results in a significant drop in Dice score performance (p < 0.01). The detailed results are not included in the main text due to table space constraints. Nevertheless, the findings demonstrate that the absence of any component, whether the Texture Attention mechanism, the Structural and Content Feature Queries, the Forward and Backward Cross-Stage Attention (FCA/BCA), or the Progressive Aggregation Strategy, leads to a statistically significant negative impact on segmentation performance, further validating the importance of each module.

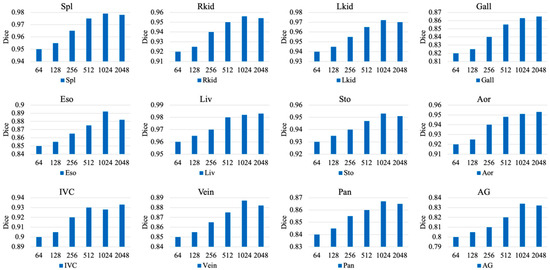

4.3.2. Hyperparameter Study

We compare the model’s performance and perform experiments across a wide range of values to investigate the effect of the intermediate feature space dimension on segmentation accuracy within the Forward Cross-Stage Attention (FCA) and Backward Cross-Stage Attention (BCA) modules. The experimental results are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Impact of Intermediate Feature Dimension on Model Performance in Backward Cross-Stage Attention (BCA) and Forward Cross-Stage Attention (FCA) Modules.

As shown in Figure 3, as the feature dimension gradually increases, the segmentation accuracy across most organs exhibits an initial improvement followed by a slight decline. The Dice scores for organs such as the liver (Liv), right kidney (Rkid), left kidney (Lkid), and spleen (Spl) continue to improve as the dimension increases from 64 to 1024. This indicates that a larger feature space allows the BCA and FCA modules to capture richer contextual and cross-scale information, which improves the learning of complex anatomical structures and boundary features. This effect is particularly pronounced for small organs, such as the pancreas (Pan) and adrenal glands (AG), where increasing the dimension from 64 to 1024 significantly improves the model’s ability to capture and represent fine-grained local regions, resulting in a substantial boost in Dice scores.

The Dice scores for some small-volume or structurally complex organs, such as the stomach (Sto) and adrenal glands (AG), start to decrease when the feature space dimension reaches 2048. This phenomenon can be attributed to the overfitting risk associated with excessive network capacity. On the one hand, the larger feature space is more likely to memorize noise or redundant local patterns from the training data because these organs have intrinsically complex anatomical structures or hazy boundaries with neighboring tissues. On the other hand, when trained on a small dataset, the increased dimensionality makes optimization more difficult and results in inadequate generalization, which ultimately leads to local structural misidentifications and lowers the segmentation accuracy on the test set.

4.3.3. Comparative Study

We perform comparative experiments against several state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods on the BTCV and FLARE public datasets in order to further validate the efficacy and generalization capability of the proposed PQAN for multi-organ segmentation in 3D medical images. The experimental results are presented in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

Comparison of PQAN with SOTA models on the BTCV dataset.

Table 3.

Comparison of PQAN with SOTA models on the FLARE dataset.

It can be observed that PQAN significantly outperforms existing SOTA methods on the BTCV dataset. Although CMAST uses an attention fusion module and cross-modal pseudo-label self-training to achieve competitive segmentation performance in multi-modal scenarios, it is not very good at aligning and fusing cross-scale features, which makes it challenging to fully utilize multi-level feature information, particularly in single-modal settings or datasets without registration. The A-Eval method focuses on cross-dataset and cross-modal evaluation, revealing that domain shifts cause performance variations across different datasets. However, A-Eval still lacks an effective strategy for uniformly fusing multi-scale features. Similarly, DPC-Net uses decoupled pixel attention and self-attention mechanisms to improve small-target recognition, but it does not use a fine-grained fusion strategy for cross-scale features. By adding Structural Feature Query and Content Feature Query, which enable accurate interactions between the encoding and decoding stages, our suggested PQAN successfully combines the benefits of CNN and Transformer-based features. Moreover, the integration of Forward and Backward Cross-Stage Attention (FCA/BCA) reduces semantic deviations during cross-scale fusion by gradually aligning and aggregating multi-scale features. This design ensures a tighter integration of high-level global semantics and low-level local details, strengthening the model’s representation capability for complex anatomical structures and small-volume organs. PQAN consequently performs better in segmentation on BTCV and other datasets.

Similarly, our proposed PQAN has the best performance on the FLARE dataset. In contrast, EVIL focuses primarily on pseudo-labeling but does not place enough emphasis on structural semantic feature extraction and representation. This limitation is particularly evident when dealing with morphologically complex organs or blurred organ boundaries, as EVIL lacks dedicated mechanisms for capturing fine-grained structural details. BASIC, on the other hand, addresses the class imbalance issue via Subclass Segmentation (SCS) and Semantic Conflict Penalty mechanisms, but it does not provide a comprehensive strategy for fine-grained structural modeling or cross-hierarchical feature alignment. As a result, BASIC struggles to handle organs with large-scale variations, often resulting in local detail loss and incomplete boundary recognition. Our proposed PQAN has a significant advantage in structural semantic feature extraction. The model accurately captures and improves the morphology and boundary details of target organs across different encoding–decoding stages by combining Structural Feature Query with Texture Attention (TA). Meanwhile, Content Feature Query collaborates with TA during the semantic integration process to effectively align local structural representations with global contextual information. This design ensures robust segmentation performance across multi-scale and morphologically diverse organs.

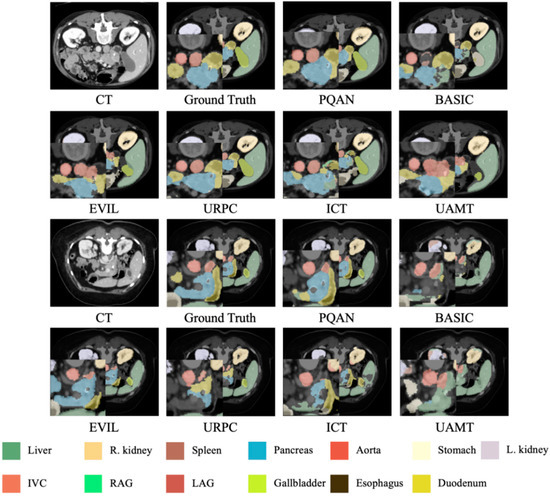

4.3.4. Visualization Study

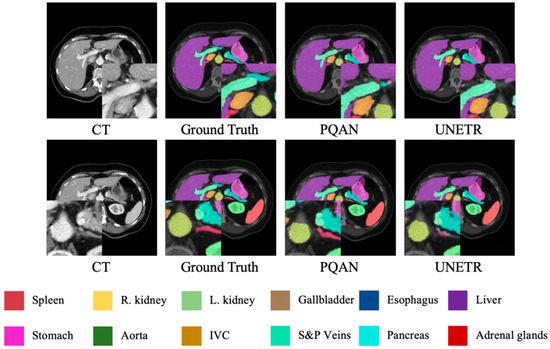

To demonstrate PQAN’s segmentation capability across various organs and complex anatomical structures, we perform a visual analysis of the segmentation results on the test set. The segmentation results of various methods on the FLARE dataset are compared, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Visualization Comparison of Segmentation Results on the FLARE Dataset Using Different Methods.

The visualization results in Figure 4 show that PQAN has higher detail fidelity when segmenting small target organs and complex anatomical structures. It accurately detects organ boundaries and local textures while minimizing adhesion artifacts and tissue misclassification. In contrast, other methods struggle with small organ segmentation, often introducing holes or boundary misclassifications. Additionally, when processing large organs and vascular junctions, they show blurred contours and semantic misalignments. PQAN overcomes these challenges by combining Structural Feature Query and Texture Attention, which extract morphological and edge information at various stages. Furthermore, PQAN uses FCA and BCA to gradually align cross-scale features, ensuring high consistency and accuracy in both local and global segmentation performance.

We also performed segmentation visualization on the BTCV dataset, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Visualization Comparison of Segmentation Results on the BTCV Dataset Using Different Methods.

Unlike the FLARE dataset, which emphasizes small-volume organs and inconsistent annotations, the BTCV dataset focuses on accurately segmenting abdominal organs with significant shape and size variations within the same CT scan. As shown in Figure 5, PQAN has superior differentiation and contour consistency, especially in organs with complex boundaries and overlapping anatomical structures, such as large organs and vascular systems. In contrast, UNETR occasionally shows minor adhesions or misclassifications in the transition regions between adjacent organs, particularly in densely clustered structures such as the liver, stomach, and pancreas, where fine edges are more likely to be lost. By leveraging Structural Feature Query and Content Feature Query, PQAN establishes a more comprehensive multi-scale structural-semantic representation across encoding and decoding stages. Furthermore, the Texture Attention (TA) mechanism specifically improves boundary texture recognition, resulting in higher segmentation accuracy and sharper contours even in large-scale, multi-organ abdominal CT images. This further validates PQAN’s adaptability to complex anatomical structures.

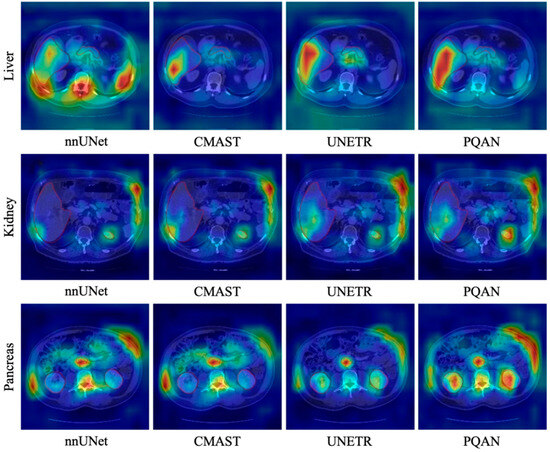

Additionally, we used heatmap visualizations for organs with noticeable segmentation differences to investigate the internal mechanisms of various models. The experimental results are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Heatmap Visualization Comparison of Different Methods on the BTCV dataset.

It can be observed that different models exhibit distinct activation distributions when focusing on organ regions. nnUNet demonstrates a dispersed activation pattern for the liver, kidney, and pancreas, with some blurred edges and high activation in non-target regions. CMAST, despite its advantages in cross-modal pseudo-labeling and feature fusion, exhibits missing activations at some organ boundaries, resulting in an imbalance between internal and peripheral feature areas. UNETR demonstrates a more centralized activation distribution, but it fails to capture fine morphological variations in peripheral regions, resulting in local activation loss at organ edges. In comparison, PQAN produces a more defined and concentrated heatmap distribution within the target organ regions. Whether in the large-area outer boundary of the liver or in the complex structures of the kidneys and pancreas, PQAN consistently demonstrates higher activation and boundary continuity, reinforcing its effectiveness in precise anatomical structure segmentation.

These differences originate from PQAN’s hierarchical modeling of structural and content features. On the one hand, the Structural Feature Query enhances the model’s perception of overall morphological contours, allowing the heatmap to focus more accurately on the main organ regions. On the other hand, the Content Feature Query and Texture Attention (TA) refine local texture information during multi-scale feature fusion, assisting the network in distinguishing ambiguous regions and complex boundaries. Additionally, the Forward and Backward Cross-Stage Attention (FCA/BCA) algorithm gradually aligns features across different resolutions, allowing the network to refine target regions from top to bottom. This results in more continuous and complete boundary activations in the heatmaps, leading to greater stability and accuracy in organ segmentation.

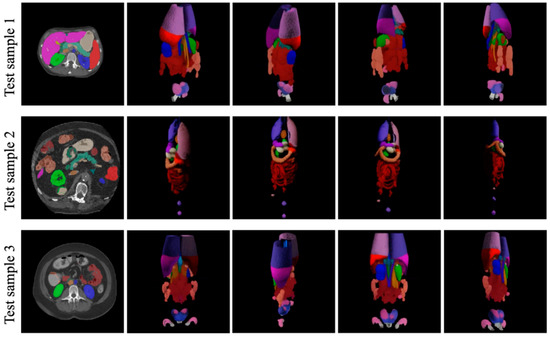

To further validate PQAN’s generalization capability, we tested it on CT images outside of the training datasets, and the results are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Generalization Performance of PQAN on Unseen CT Images.

PQAN accurately identifies and segments abdominal organs in previously unseen data, maintaining segmentation quality comparable to that observed in training datasets. Despite variations in organ positions, shapes, and scanning ranges, PQAN produces complete and well-defined predictions for major organs such as the liver, kidneys, spleen, and pancreas, as well as accurate recognition of small target organs. These results confirm that the structural and content feature query mechanisms, combined with multi-stage attention fusion strategies, effectively capture both global and local anatomical information, resulting in strong generalization performance in previously unseen anatomical variations and imaging conditions.

5. Conclusions

To address the limitations of existing deep learning approaches in integrating CNN and Transformer features, particularly in local detail representation and cross-scale semantic inconsistency, this paper proposes a Progressive Query Aggregation Network (PQAN). Extensive experiments demonstrate that PQAN is effective at facilitating efficient feature interaction and fusion at various stages of the encoder–decoder network using Structural and Content Feature Queries. Additionally, the Texture Attention (TA) mechanism improves local texture and boundary detail representation, whereas Forward and Backward Cross-Stage Attention (FCA/BCA), when combined with a Progressive Aggregation Strategy, significantly reduces semantic deviation in multi-scale fusion. Experimental results show that PQAN significantly improves segmentation accuracy on BTCV, FLARE, and other public datasets, particularly in small-target recognition and complex boundary segmentation, demonstrating robustness and strong generalizability. However, PQAN does have some limitations. The model’s precision in extreme deformations or complex pathological regions could be improved further. Future work will include integrating additional medical imaging modalities and evaluating larger-scale, multi-center medical image databases to improve the model’s ability to recognize fine-grained structures and heterogeneous lesions.

Author Contributions

W.P.: Conceptualization, Validation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing; G.H.: Project Administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing; J.L.: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation; C.L.: Software, Data Curation, Visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, S.; Ren, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Qiao, S.; Liu, T.; Pang, S. TPFIANet: Three path feature progressive interactive attention learning network for medical image segmentation. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 323, 113778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayed, M.E.; Islam, S.S.; Niha, S.I.; Jim, J.R.; Kabir, M.M.; Mridha, M.F. Deep learning for medical image segmentation: State-of-the-art advancements and challenges. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2024, 47, 101504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, R.; Aghdam, E.K.; Rauland, A.; Jia, Y.; Avval, A.H.; Bozorgpour, A.; Karimijafarbigloo, S.; Cohen, J.P.; Adeli, E.; Merhof, D. Medical image segmentation review: The success of u-net. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 10076–10095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, A.; Shi, J.; Wu, X.J. CSCA U-Net: A channel and space compound attention CNN for medical image segmentation. Artif. Intell. Med. 2024, 150, 102800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allaoui, M.L.; Allili, M.S.; Belaid, A. HA-U3Net: A Modality-Agnostic Framework for 3D Medical Image Segmentation Using Nested V-Net Structure and Hybrid Attention. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 327, 114127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mei, J.; Li, X.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Wei, Q.; Luo, X.; Xie, Y.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; et al. TransUNet: Rethinking the U-Net architecture design for medical image segmentation through the lens of transformers. Med. Image Anal. 2024, 97, 103280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wu, T.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, J.; Wu, J. EDGE: Edge distillation and gap elimination for heterogeneous networks in 3D medical image segmentation. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 314, 113234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Ye, T.; Yang, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhu, L. Segmamba: Long-range sequential modeling mamba for 3d medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Marrakesh, Morocco, 6–10 October 2024; pp. 578–588. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Miao, J.; Wu, D.; Zhong, A.; Yan, Z.; Kim, S.; Hu, J.; Liu, Z.; Sun, L.; Li, X.; et al. Ma-sam: Modality-agnostic sam adaptation for 3d medical image segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 2024, 98, 103310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isensee, F.; Wald, T.; Ulrich, C.; Baumgartner, M.; Roy, S.; Maier-Hein, K.; Jaeger, P.F. nnu-net revisited: A call for rigorous validation in 3d medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Marrakesh, Morocco, 6–10 October 2024; pp. 488–498. [Google Scholar]

- Saifullah, S.; Dreżewski, R. Enhancing breast cancer diagnosis: A CNN-based approach for medical image segmentation and classification. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science, Malaga, Spain, 2–4 July 2024; pp. 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Tamilmani, G.; Phaneendra Varma, C.H.; Devi, V.B.; Ramesh Babu, G. Medical image segmentation using grey wolf-based u-net with bi-directional convolutional LSTM. Int. J. Pattern Recognit. Artif. Intell. 2024, 38, 2354025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, L.; Gao, Q.; Du, M.; Tan, T.; Zhang, X.; Tong, T. HTC-Net: A hybrid CNN-transformer framework for medical image segmentation. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 88, 105605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Lin, X.; Yang, X.; Yu, L.; Cheng, K.T.; Yan, Z. UCTNet: Uncertainty-guided CNN-Transformer hybrid networks for medical image segmentation. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 152, 110491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.; Cai, P.; Jiang, L.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Brau-net++: U-shaped hybrid cnn-transformer network for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.00722. [Google Scholar]

- Ao, Y.; Shi, W.; Ji, B.; Miao, Y.; He, W.; Jiang, Z. MS-TCNet: An effective Transformer–CNN combined network using multi-scale feature learning for 3D medical image segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 170, 108057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Peng, Y.; He, J.; Tian, C.; Sun, X.; Wang, R. HmsU-Net: A hybrid multi-scale U-net based on a CNN and transformer for medical image segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 170, 108013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Girshick, R.; Gupta, A.; He, K. Non-local neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7794–7803. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Chen, S.; Pan, Z.; Zeng, S.; Yang, W. Perspective+ Unet: Enhancing Segmentation with Bi-Path Fusion and Efficient Non-Local Attention for Superior Receptive Fields. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Marrakesh, Morocco, 6–10 October 2024; pp. 499–509. [Google Scholar]

- Song, E.; Zhan, B.; Liu, H. Combining external-latent attention for medical image segmentation. Neural Netw. 2024, 170, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Nguyen, T.D.C. Medical Images Enhancement by Integrating CLAHE with Wavelet Transform and Non-Local Means Denoising. Acad. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 7, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria Nancy, A.; Sathyarajasekaran, K. SwinVNETR: Swin V-net Transformer with non-local block for volumetric MRI Brain Tumor Segmentation. Automatika Časopis za Automatiku Mjerenje Elektroniku Računarstvo i Komunikacije 2024, 65, 1350–1363. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, S.; Yuan, Q.; Lei, X.; Huang, R.; Guo, L.; Liu, K.; Chen, R. BFNet: A full-encoder skip connect way for medical image segmentation. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1412985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, S.; Navard, P.; Yilmaz, A. Segformer3d: An efficient transformer for 3d medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 4981–4988. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Chen, Y.; Ji, W.; Yang, F. SSTrans-Net: Smart Swin Transformer Network for medical image segmentation. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2024, 91, 106071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gao, P.; Yu, T.; Wang, F.; Yuan, R.Y. CSWin-UNet: Transformer UNet with cross-shaped windows for medical image segmentation. Inf. Fusion 2025, 113, 102634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ji, W.; Fu, H.; Xu, M.; Jin, Y.; Xu, Y. Medsegdiff-v2: Diffusion-based medical image segmentation with transformer. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 38, pp. 6030–6038. [Google Scholar]

- Benabid, A.; Yuan, J.; Elhassan, M.A.; Benabid, D. CFNet: Cross-scale fusion network for medical image segmentation. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 36, 102123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, F.; Wang, H.; Zhang, F. Cross-scale informative priors network for medical image segmentation. Digit. Signal Process. 2025, 157, 104883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Wu, Z.; Liu, R.; Zhou, J.; Wang, M.; Wu, T.; Liu, J. Sosegformer: A Cross-Scale Feature Correlated Network For Small Medical Object Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Athens, Greece, 27–30 May 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, L.; Tian, S.; Huo, X. CRMEFNet: A coupled refinement, multiscale exploration and fusion network for medical image segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 171, 108202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zheng, X.; Wu, X.; Tang, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. CasUNeXt: A Cascaded Transformer With Intra-and Inter-Scale Information for Medical Image Segmentation. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 2024, 34, e23184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kervadec, H.; Bouchtiba, J.; Desrosiers, C.; Granger, E.; Dolz, J.; Ben Ayed, I. Boundary loss for highly unbalanced segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Imaging with Deep Learning, London, UK, 8–10 July 2019; pp. 285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Milletari, F.; Navab, N.; Ahmadi, S.-A. “V-net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation”. In Proceedings of the 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), Stanford, CA, USA, 25–28 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Landman, B.; Xu, Z.; Igelsias, J.; Styner, M.; Langerak, T.; Klein, A. Multi-Atlas Labeling Beyond the Cranial Vault. Available online: https://www.synapse.org (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, S.; Ge, C.; Wang, E.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, Z.; Lyu, P.; He, J.; Wang, B. Automatic organ and pan-cancer segmentation in abdomen ct: The flare 2023 challenge. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.12534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Lu, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Feng, J.; Xiang, T.; Torr, P.H.S.; et al. Rethinking semantic segmentation from a sequence-to-sequence perspective with transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 6881–6890. [Google Scholar]

- Isensee, F.; Jaeger, P.F.; Kohl, S.A.; Petersen, J.; Maier-Hein, K.H. nnU-Net: A self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, M.; Touvron, H.; Misra, I.; Jégou, H.; Mairal, J.; Bojanowski, P.; Joulin, A. Emerging properties in self-supervised vision transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 9650–9660. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shen, C.; Xia, Y. Cotr: Efficiently bridging cnn and transformer for 3d medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2021: 24th International Conference, Strasbourg, France, 27 September–1 October 2021; Volume 3, pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Gao, R.; Lee, H.H.; Han, S.; Chen, Y.; Gao, D.; Nath, V.; Bermudez, C.; Savona, M.R.; Abramson, R.G.; et al. High-resolution 3D abdominal segmentation with random patch network fusion. Med. Image Anal. 2021, 69, 101894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Deng, M.; Zhong, Y.; Cai, J.; Chan, K.K.W.; Dou, Q.; Chong, K.K.L.; Heng, P.-A.; Chu, W.C.-W. Multi-organ Segmentation from Partially Labeled and Unaligned Multi-modal MRI in Thyroid-associated Orbitopathy. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2025, 29, 4161–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Deng, Z.; Ye, J.; Wang, H.; Su, Y.; Li, T.; Sun, H.; Cheng, J.; Chen, J.; He, J.; et al. A-Eval: A benchmark for cross-dataset and cross-modality evaluation of abdominal multi-organ segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 2025, 101, 103499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillot, M.; Baquero, B.; Le, C.; Deleat-Besson, R.; Bianchi, J.; Ruellas, A.; Gurgel, M.; Yatabe, M.; Al Turkestani, N.; Najarian, K.; et al. Automatic multi-anatomical skull structure segmentation of cone-beam computed tomography scans using 3D UNETR. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Ding, L.; Zhang, D.; Wu, J.; Liang, M.; Zheng, J.; Pang, W. Decoupled pixel-wise correction for abdominal multi-organ segmentation. Complex Intell. Syst. 2025, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Sutskever, I.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Chen, G.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Huang, G.; Zhou, J.; Lu, J. Denseclip: Language-guided dense prediction with context-aware prompting. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 18082–18091. [Google Scholar]

- Eslami, S.; de Melo, G.; Meinel, C. Does clip benefit visual question answering in the medical domain as much as it does in the general domain? arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.13906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Huang, X.; Hou, J.; Ren, C.; Jiang, L.; Zhao, R.-W.; Jin, G.; Zhang, Y.; Geng, D. MOSMOS: Multi-organ segmentation facilitated by medical report supervision. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 106, 107743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springenberg, J.T. Unsupervised and semi-supervised learning with categorical generative adversarial networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.06390. [Google Scholar]

- Tarvainen, A.; Valpola, H. Mean teachers are better role models: Weight-averaged consistency targets improve semi-supervised deep learning results. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.01780. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Fu, C.W.; Heng, P.A. Uncertainty-aware self-ensembling model for semi-supervised 3D left atrium segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2019: 22nd International Conference, Shenzhen, China, 13–17 October 2019; Volume 22, pp. 605–613. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, V.; Kawaguchi, K.; Lamb, A.; Kannala, J.; Solin, A.; Bengio, Y.; Lopez-Paz, D. Interpolation consistency training for semi-supervised learning. Neural Netw. 2022, 145, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wang, G.; Liao, W.; Chen, J.; Song, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Metaxas, D.N.; Zhang, S. Semi-supervised medical image segmentation via uncertainty rectified pyramid consistency. Med. Image Anal. 2022, 80, 102517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Shen, C.; Wang, Z.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, Y. EVIL: Evidential inference learning for trustworthy semi-supervised medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 20th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Cartagena, Colombia, 18–21 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.; Wen, L.; Xu, Y.; Yan, B.; Wu, X.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y. BASIC: Semi-supervised Multi-organ Segmentation with Balanced Subclass Regularization and Semantic-conflict Penalty. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.03580. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Safari, M.; Li, Q.; Chang, C.W.; Qiu, R.L.; Roper, J.; Yu, D.S.; Yang, X. Triad: Vision Foundation Model for 3D Magnetic Resonance Imaging. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.14064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Song, H.; Liu, L.; Cui, H. An efficient segment anything model for the segmentation of medical images. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).