A Lightweight Spatiotemporal Skeleton Network for Abnormal Train Driver Action Detection

Abstract

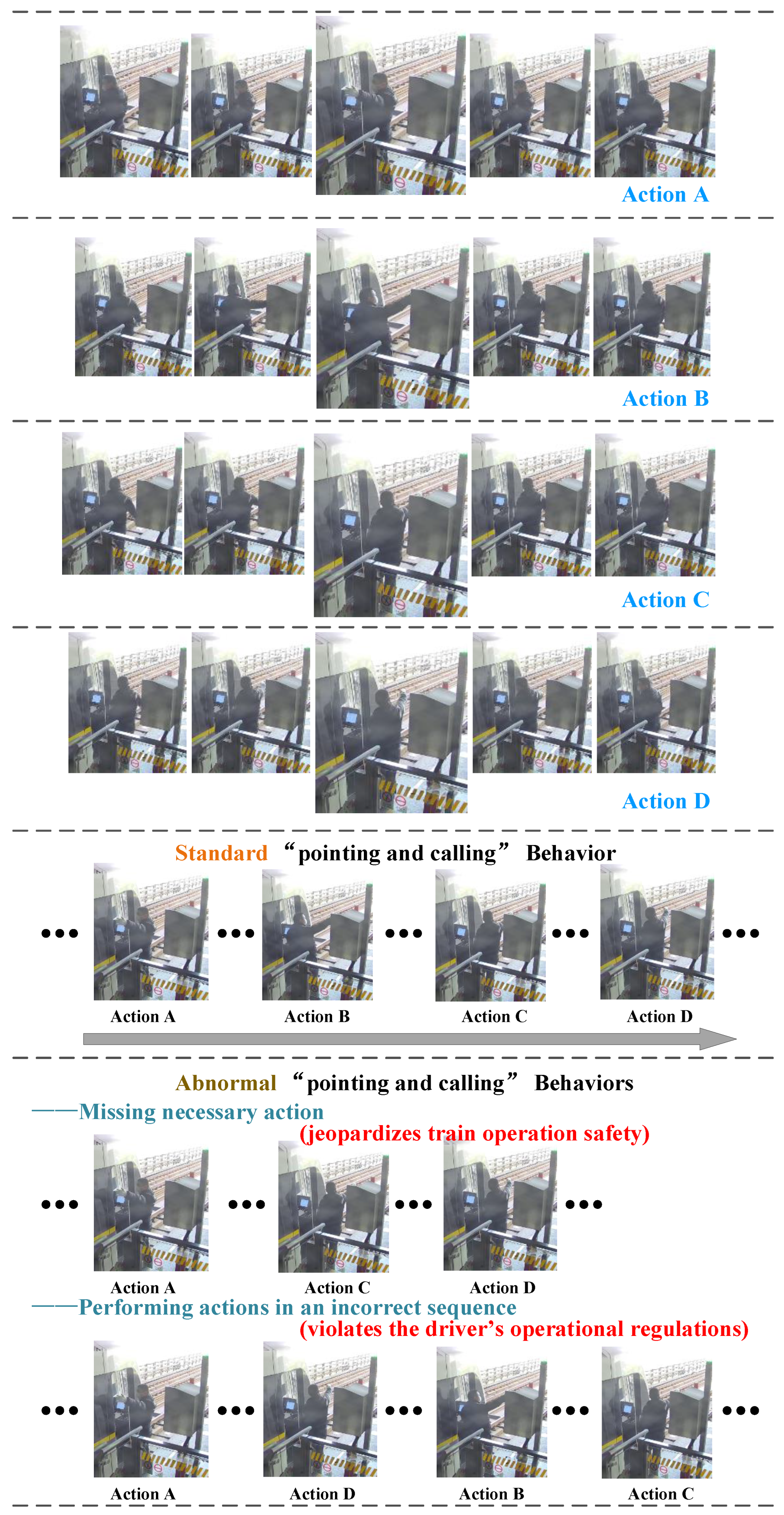

1. Introduction

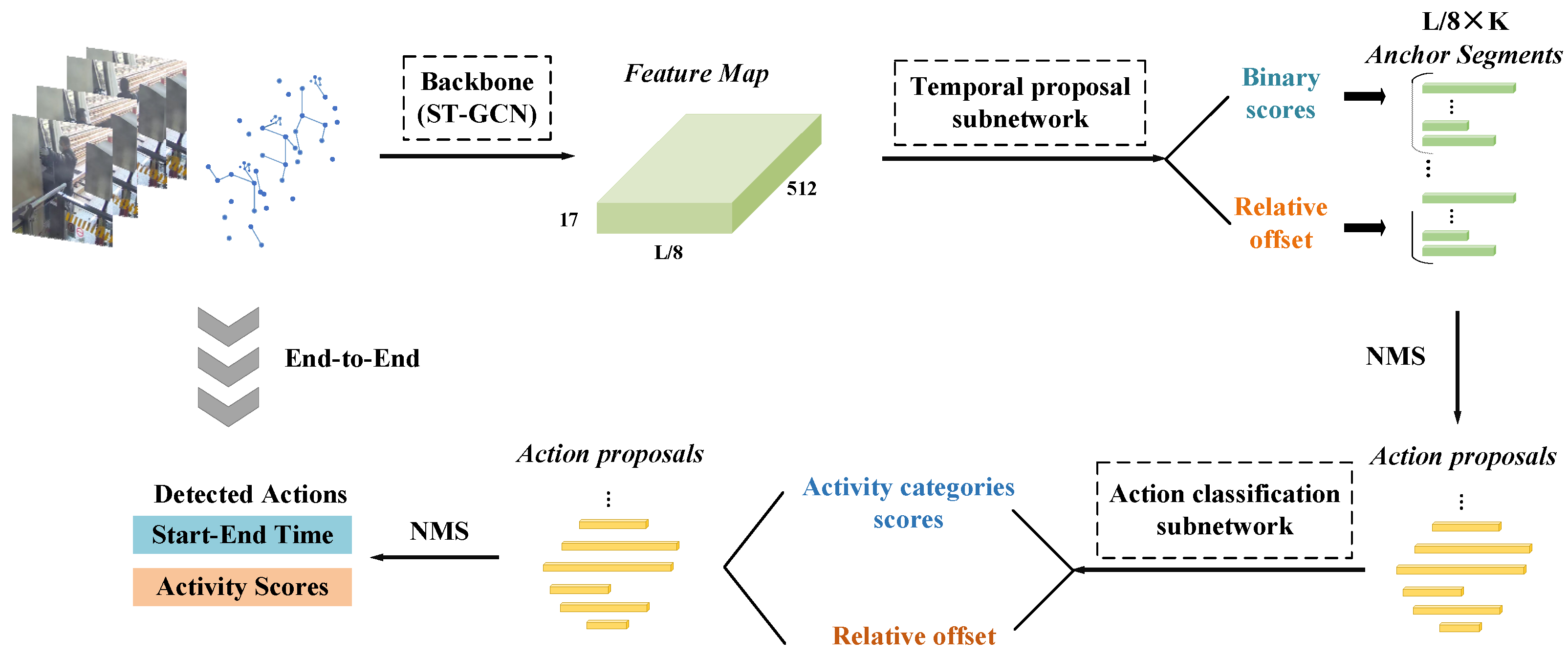

- A skeleton-based temporal action detection method is proposed for identifying abnormal behaviors of urban rail train drivers. The method utilizes 2D skeleton sequences and applies spatiotemporal graph convolution for feature extraction, thereby reducing model parameters and computational overhead while improving speed and equipment adaptability. Moreover, a tailored skeleton topology, designed according to the characteristics of driver actions, enhances the model’s ability to discriminate similar actions in 2D skeleton data.

- An end-to-end detection framework adapted from R-C3D network is developed for skeleton data. The feature propagation layers are distinctly redesigned for classification and boundary regression, enabling the models to focus on task-relevant information and achieve efficient end-to-end detection with improved deployment feasibility.

- An effective training and validation strategy is introduced. To overcome the absence of pretrained models and the limitations of small-scale datasets, a partial pre-training followed by joint optimization scheme is adopted. The proposed approach demonstrates strong performance on a custom dataset, and ablation experiments further validate the effectiveness of the task-specific feature layer design.

2. Related Work

2.1. Skeleton-Based Action Recognition

2.2. Temporal Action Detection

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Feature Extraction Subnetwork

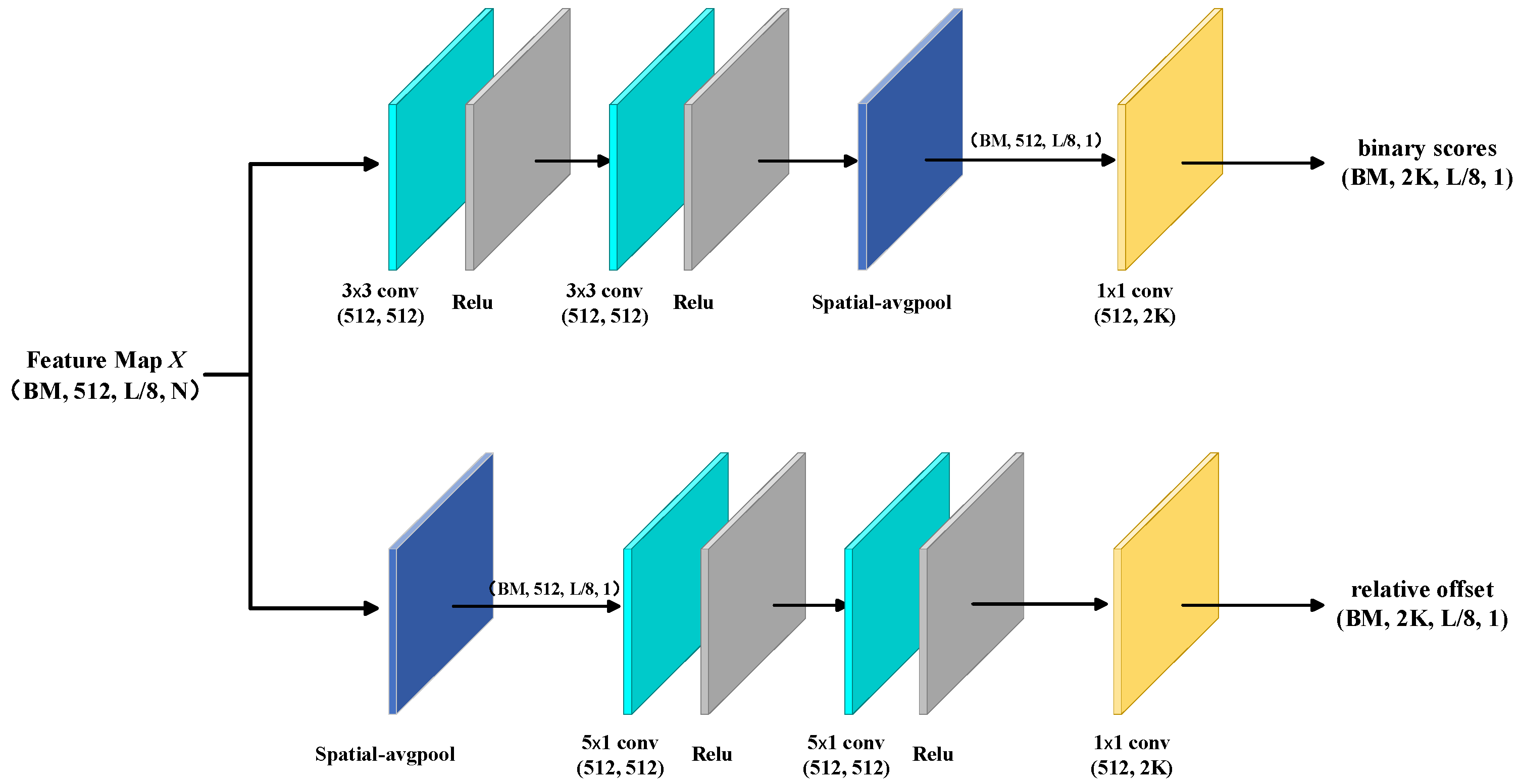

3.2. Temporal Proposal Subnetwork

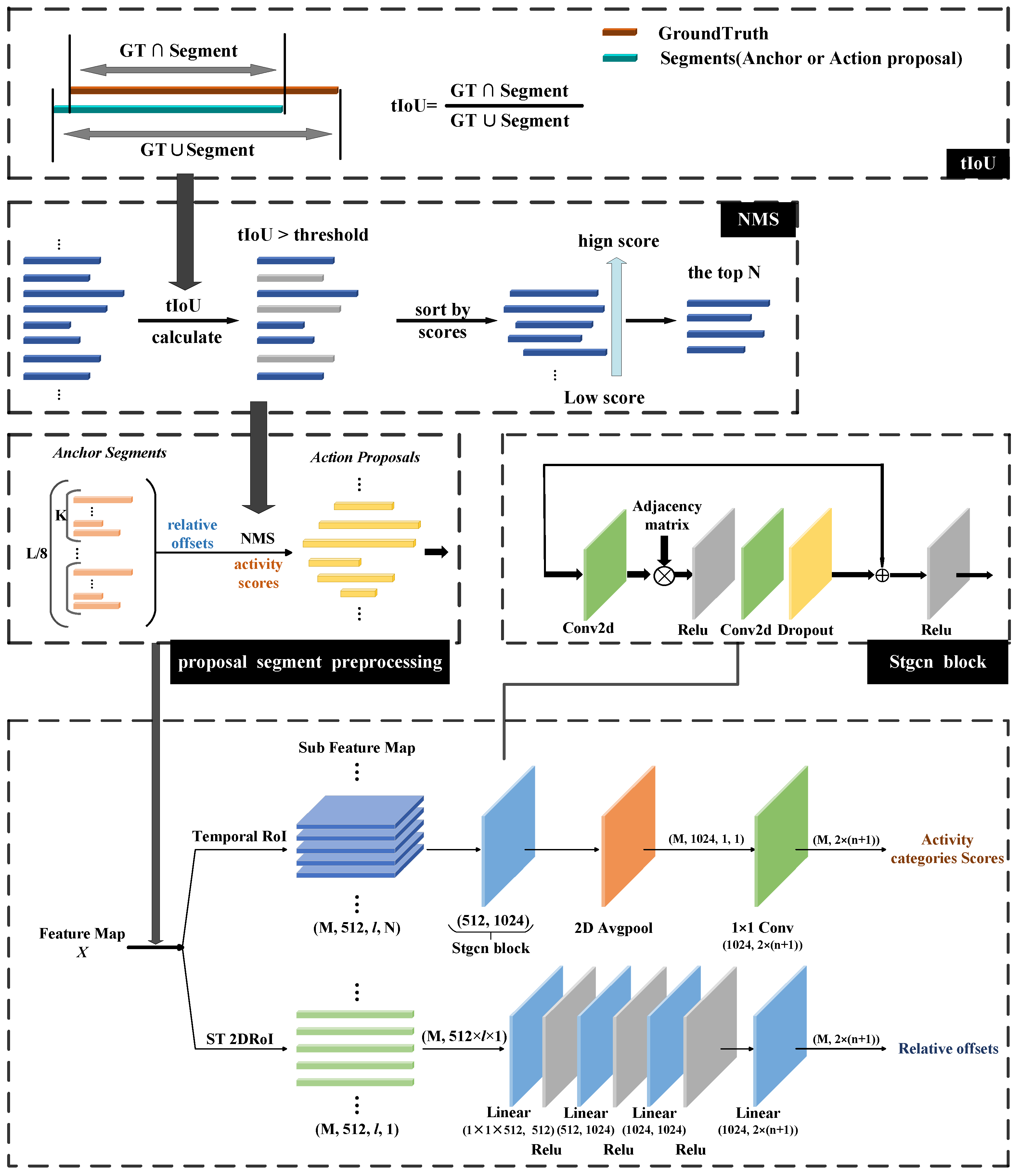

3.3. Action Classification Subnetwork

3.4. Prediction Process

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Data

4.1.2. Loss Function

4.1.3. Training Setup and Procedure

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

- Compute the tIoU values between all detected actions and ground-truth segments according to Equation (7), forming an matrix, where and denote the numbers of detected actions and ground-truth segments, respectively.

- For each detected action, identify the maximum tIoU value and the corresponding ground-truth index, thereby generating an matrix that stores the matched ground-truth index and the associated tIoU value.

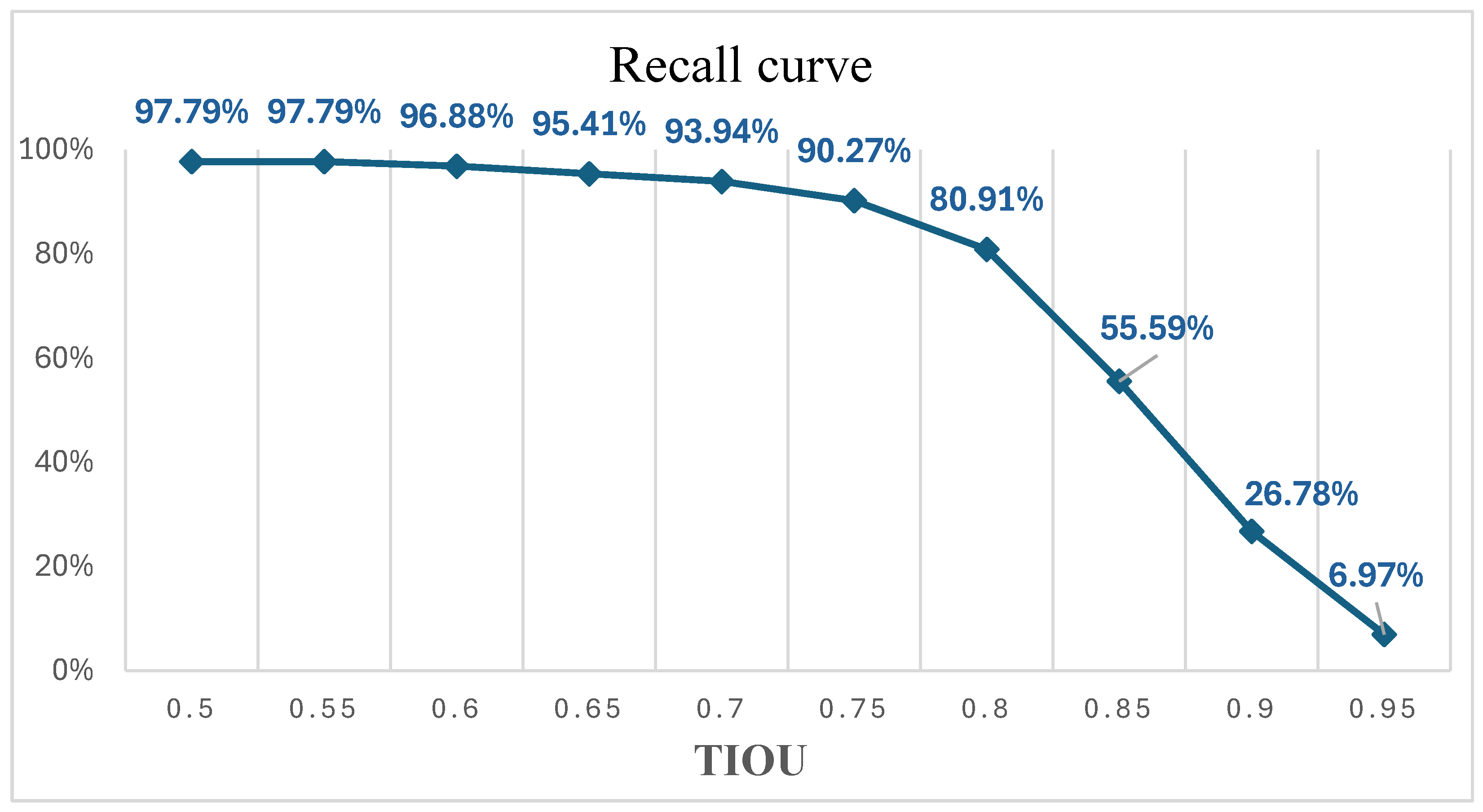

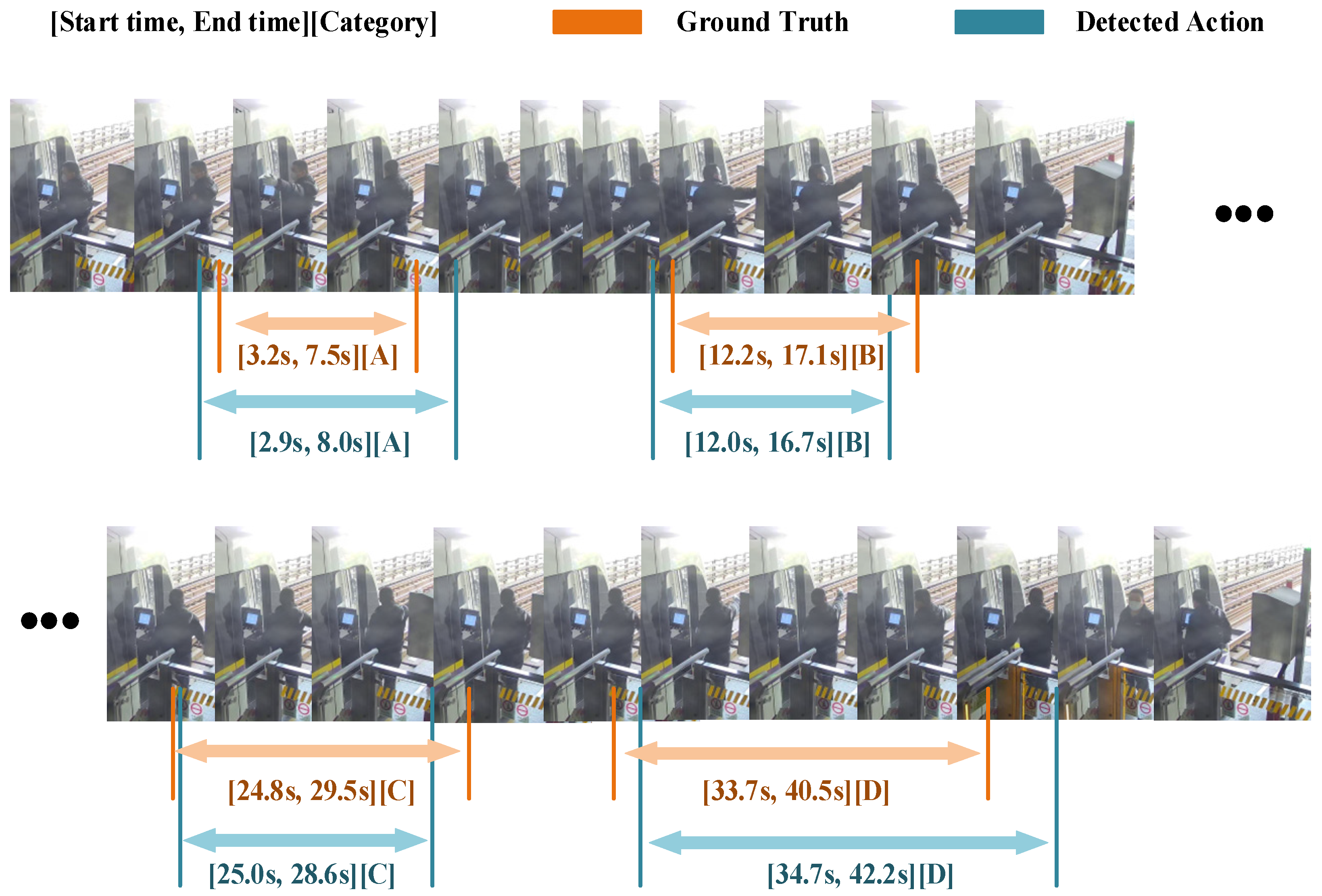

4.3. Experimental Results

4.4. Ablation Experiment

4.4.1. Effectiveness of the Proposed Skeleton Topology

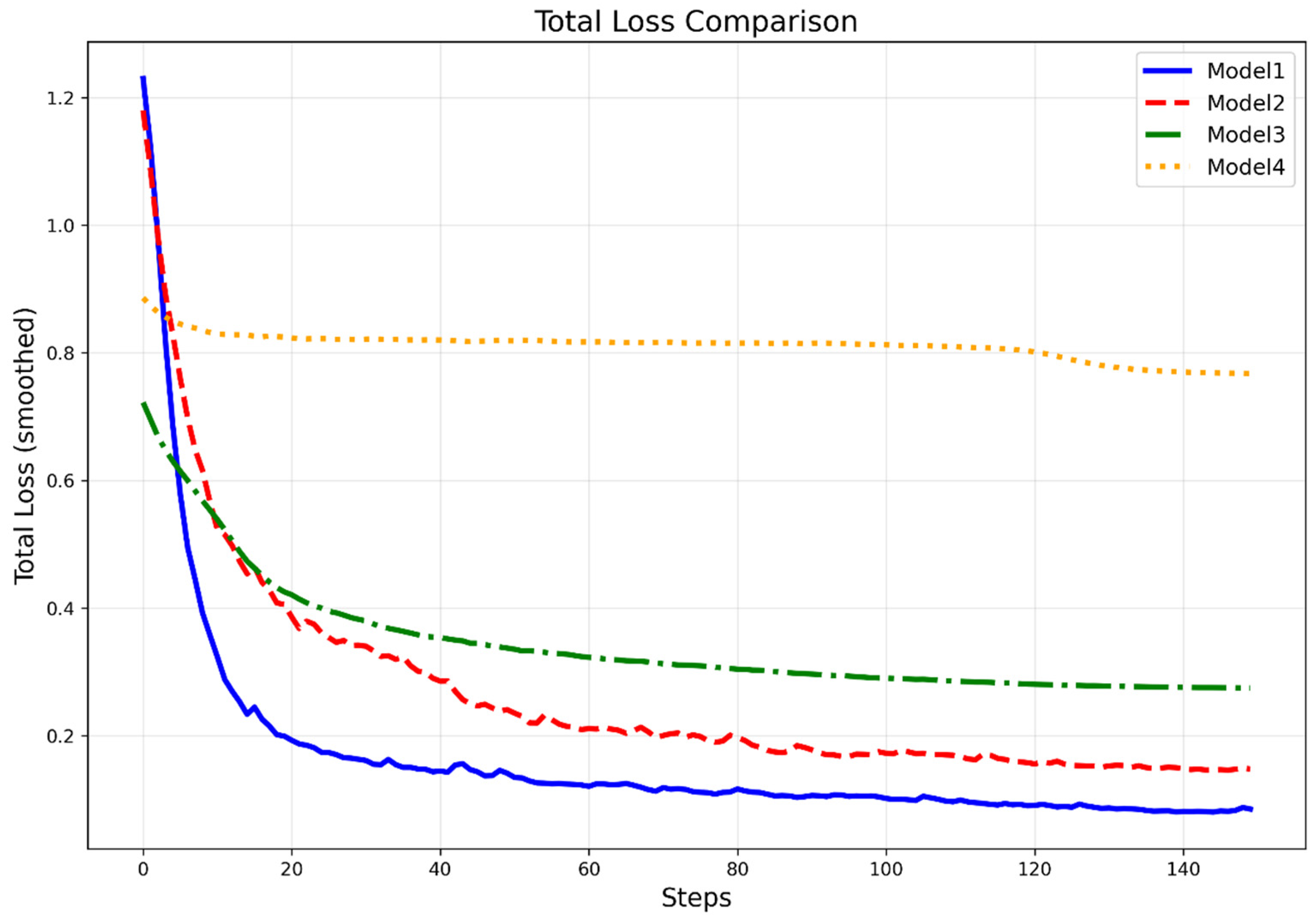

4.4.2. Contributions of Training Strategy

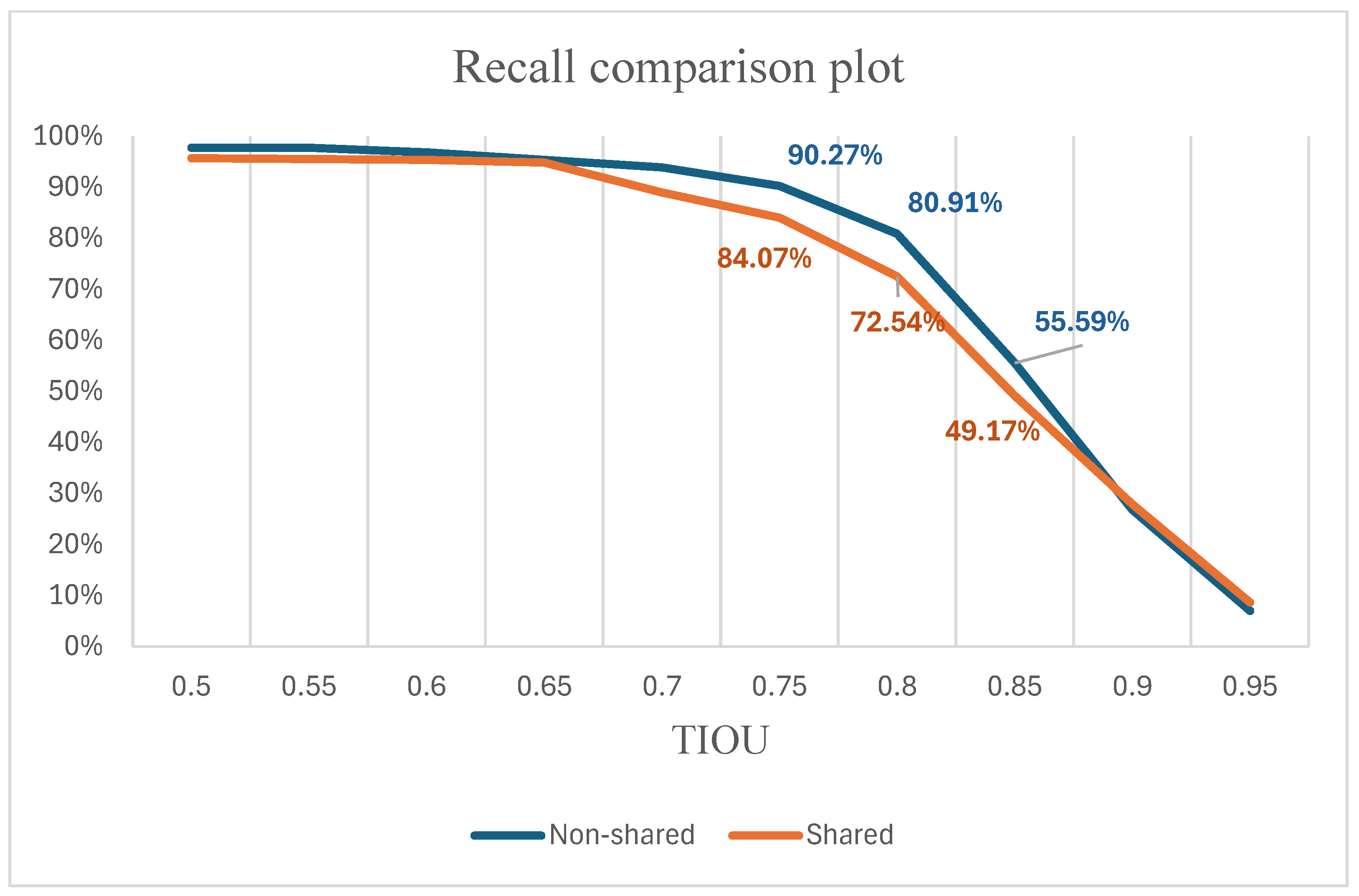

4.4.3. Ablation on Non-Shared Feature Propagation Design

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCTV | Closed Circuit Television |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| GCN | Graph Convolutional Network |

| mAP | Mean Average Precision |

| tIoU | Time Intersection over Union |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| TAD | Temporal Action Detection |

| NMS | Non-maximum Suppression |

References

- Li, X. Detection of Power System Personnel’s Abnormal Behavior Based on Machine Vision. In Proceedings of the 2024 Boao New Power System International Forum—Power System and New Energy Technology Innovation Forum (NPSIF), Qionghai, China, 8–10 December 2024; pp. 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Geest, R.; Gavves, E.; Ghodrati, A.; Li, Z.; Snoek, C.; Tuytelaars, T. Online Action Detection. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2016; Leibe, B., Matas, J., Sebe, N., Welling, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Kang, H.; Han, S.H.; Yang, M.-H.; Kim, S.J. MiniROAD: Minimal RNN Framework for Online Action Detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 10307–10316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Gao, M.; Chen, Y.-T.; Davis, L.; Crandall, D. Temporal Recurrent Networks for Online Action Detection. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 29 October–2 November 2019; pp. 5531–5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mittal, G.; Yu, Y.; Kong, Y.; Chen, M. GateHUB: Gated History Unit with Background Suppression for Online Action Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 19893–19902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Ren, Z.; Wu, Y.; Hua, G.; Ji, Q. Uncertainty-Based Spatial-Temporal Attention for Online Action Detection. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2022; Avidan, S., Brostow, G., Cissé, M., Farinella, G.M., Hassner, T., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, B.; Xiang, J.; Zheng, W.; Wang, Z.; Ren, W.; Luo, S.; Liu, H. Skeleton-Based Online Action Detection with Temporal Enhancement. In Emotional Intelligence; Huang, X., Mao, Q., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, H. Advancing Driver Behavior Recognition: An Intelligent Approach Utilizing ResNet. Autom. Control Comput. Sci. 2024, 58, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkar, A.; Kulkarni, N.; Raut, A. Driver Drowsiness Detection Using Deep Learning. In Applied Information Processing Systems; Iyer, B., Ghosh, D., Balas, V.E., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darapaneni, N.; Arora, J.; Hazra, M.; Vig, N.; Gandhi, S.S.; Gupta, S.; Paduri, A.R. Detection of Distracted Driver Using Convolution Neural Network. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.-L.; Putro, M.D.; Jo, K.-H. Driver Behaviors Recognizer Based on Light-Weight Convolutional Neural Network Architecture and Attention Mechanism. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 71019–71029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Liu, X.; Luo, M.; Zhang, P.; Wang, W.; Wang, J. Video-Based Abnormal Driving Behavior Detection via Deep Learning Fusions. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 64571–64582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, M.; Asim Husain, A.; Maity, T.; Kumar Yadav, R. Advance Intelligent Video Surveillance System (AIVSS): A Future Aspect. In Intelligent Video Surveillance; Neves, A.J.R., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdani, E.; Tian, Y. Deep Learning-Based Action Detection in Untrimmed Videos: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 4302–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, Z.; Wang, D.; Chang, S.-F. Temporal Action Localization in Untrimmed Videos via Multi-Stage CNNs. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Ding, E.; Wen, S. BMN: Boundary-Matching Network for Temporal Action Proposal Generation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3888–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Das, A.; Saenko, K. R-C3D: Region Convolutional 3D Network for Temporal Activity Detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2017, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 5794–5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Zhang, N.; Xie, H.; Li, S.; Feng, T. MBGNet: Multi-Branch Boundary Generation Network with Temporal Context Aggregation for Temporal Action Detection. Appl. Intell. 2024, 54, 9045–9066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, J.; Zisserman, A. Quo Vadis, Action Recognition? A New Model and the Kinetics Dataset. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4724–4733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Two-Stream Convolutional Networks for Action Recognition in Videos. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 1st ed.; MIT Press: Montreal, QC, Canada; Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 568–576. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, D.; Bourdev, L.; Fergus, R.; Torresani, L.; Paluri, M. Learning Spatiotemporal Features with 3D Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 4489–4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Yao, T.; Mei, T. Learning Spatio-Temporal Representation with Pseudo-3D Residual Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 5534–5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Ke, Q.; Rahmani, H.; Bennamoun, M.; Wang, G.; Liu, J. Human Action Recognition From Various Data Modalities: A Review. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 3200–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Simon, T.; Wei, S.-E.; Sheikh, Y. Realtime Multi-Person 2D Pose Estimation Using Part Affinity Fields. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.-S.; Li, J.; Tang, H.; Xu, C.; Zhu, H.; Xiu, Y.; Li, Y.-L.; Lu, C. AlphaPose: Whole-Body Regional Multi-Person Pose Estimation and Tracking in Real-Time. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 7157–7173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Lu, H. Skeleton-Based Action Recognition With Directed Graph Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 7904–7913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.; Chi, H.-G.; Huang, Q.; Ramani, K. InfoGCN++: Learning Representation by Predicting the Future for Online Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Chen, H.; Chen, Y.; Dai, Y.; He, M. Skeleton Boxes: Solving Skeleton Based Action Detection with a Single Deep Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia & Expo Workshops (ICMEW), Hong Kong, China, 10–14 July 2017; pp. 613–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Han, J.; Xie, R.; Wang, C.; Duan, X.; Rong, Y.; Zeng, X.; Tao, J. MC-LSTM: Real-Time 3D Human Action Detection System for Intelligent Healthcare Applications. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2021, 15, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-T.; Fang, W.-H.; Dai, S.-T.; Lu, C.-C. Skeleton Moving Pose-Based Human Fall Detection with Sparse Coding and Temporal Pyramid Pooling. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th International Conference on Applied System Innovation (ICASI), Chiayi, Taiwan, 24–25 September 2021; pp. 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, W.; See, J.; Xu, N.; Xu, S.; Yan, K.; Yang, C. CFAD: Coarse-to-Fine Action Detector for Spatiotemporal Action Localization. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2020; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J.-M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 510–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Pan, P. RCL: Recurrent Continuous Localization for Temporal Action Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 13556–13565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, D.; Tang, J.; Luo, B. Semi-Supervised Learning With Graph Learning-Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 11305–11312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Lu, H. Two-Stream Adaptive Graph Convolutional Networks for Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 12018–12027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Zhang, Y.; He, X.; Chen, W.; Cheng, J.; Lu, H. Skeleton-Based Action Recognition With Shift Graph Convolutional Network. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Voit, M.; Stiefelhagen, R. Dynamic Interaction Graphs for Driver Activity Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Rhodes, Greece, 20–23 September 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, C.; Sena, J.; Brémond, F.; Dos Santos, J.A.; Schwartz, W.R. SkeleMotion: A New Representation of Skeleton Joint Sequences Based on Motion Information for 3D Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 16th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance (AVSS), Taipei, Taiwan, 18–21 September 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.M.; Inoue, N.; Shinoda, K. A Fine-to-Coarse Convolutional Neural Network for 3D Human Action Recognition. arXiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Ye, F.; Zhong, Q.; Xie, D. Topology-Aware Convolutional Neural Network for Efficient Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2022, 36, 2866–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Kim, D.; Kang, S.; Lee, S. Ensemble Deep Learning for Skeleton-Based Action Recognition Using Temporal Sliding LSTM Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, G.; Hu, P.; Duan, L.-Y.; Kot, A.C. Global Context-Aware Attention LSTM Networks for 3D Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3671–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yan, L.; Li, H.; Wang, Y. Environmental Factors-Aware Two-Stream GCN for Skeleton-Based Behavior Recognition. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2025, 36, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.; Yang, D.; Liu, T.; Li, H.; Zhao, S.; Liu, Q. SparseShift-GCN: High Precision Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2022, 153, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Xiong, Y.; Lin, D. Spatial Temporal Graph Convolutional Networks for Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2018, 32, 7444–7452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Lu, H. Skeleton-Based Action Recognition With Multi-Stream Adaptive Graph Convolutional Networks. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 9532–9545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfattah, M.; Hassan, M.; Alahi, A. MaskCLR: Attention-Guided Contrastive Learning for Robust Action Representation Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 18678–18687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, C.; Tian, Z.; Du, S.; Zeng, W. Advancing Skeleton-Based Human Behavior Recognition: Multi-Stream Fusion Spatiotemporal Graph Convolutional Networks. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xie, W.; Tu, Z.; Li, W.; Jin, L. Multi-Part Adaptive Graph Convolutional Network for Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Padua, Italy, 18–23 July 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, C.; Zou, Y. SpatioTemporal Focus for Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 136, 109231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q. Actional-Structural Graph Convolutional Networks for Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 3590–3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Liu, H.; Jia, Y.; Hou, J. Attention-Driven Graph Clustering Network. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, ACM Conferences, Chengdu, China, 20–24 October 2021; pp. 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.-G.; Ha, M.H.; Chi, S.; Lee, S.W.; Huang, Q.; Ramani, K. InfoGCN: Representation Learning for Human Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 20154–20164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, M.; Lee, D.; Lee, S. Hierarchically Decomposed Graph Convolutional Networks for Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 10410–10419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chai, L. Multi-Attention Graph Convolutional Network for Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2024 36th Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), Xi′an, China, 25–27 May 2024; pp. 6190–6195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Hou, L.; Aktar, M.M. Recognition of Miner Action and Violation Behavior Based on the ANODE-GCN Model. Multimed. Syst. 2024, 30, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ma, F.; Jia, R.; Luo, P.; Dong, X. Skeleton-Based Violation Action Recognition Method for Safety Supervision in Operation Field of Distribution Network Based on Graph Convolutional Network. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 9, 2179–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Lu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Shan, D.; Yang, Y. A Novel Spatial-Temporal Graph for Skeleton-Based Driver Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC), Auckland, New Zealand, 27–30 October 2019; pp. 3243–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Driver-Skeleton: A Dataset for Driver Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC), Indianapolis, IN, USA, 19–22 September 2021; pp. 1509–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, X.; Ren, B.; Guo, G. An Effective Multi-Scale Framework for Driver Behavior Recognition With Incomplete Skeletons. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Yao, S.; Zhao, C.; Hu, D.; Luo, H.; Lu, Y. Lightweight Multimodal Feature Graph Convolutional Network for Dangerous Driving Behavior Detection. J. Real-Time Image Proc. 2023, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Cheng, J.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J. Multi-Scale Spatial–Temporal Convolutional Neural Network for Skeleton-Based Action Recognition. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2023, 26, 1303–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Y.-W.; Vijayanarasimhan, S.; Seybold, B.; Ross, D.A.; Deng, J.; Sukthankar, R. Rethinking the Faster R-CNN Architecture for Temporal Action Localization. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, B.; Shen, Y.; Wang, W.; Lu, W.; Suo, X. Boundary Graph Convolutional Network for Temporal Action Detection. Image Vis. Comput. 2021, 109, 104144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Z.; Guan, W.; Nie, J.; Liu, A.; Wang, M.; Chen, S. A Temporal-Aware Relation and Attention Network for Temporal Action Localization. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 4746–4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Bai, S.; Bai, X. An Empirical Study of End-to-End Temporal Action Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 19978–19987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Shen, C.; Wang, T.; Xu, K.; Xia, Q.; Xia, M.; Cai, C. Overview of Temporal Action Detection Based on Deep Learning. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sooksatra, S.; Watcharapinchai, S. A Comprehensive Review on Temporal-Action Proposal Generation. J. Imaging 2022, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Ma, T.; Wu, F.; Qian, J.; Liao, F.; Huang, J. Application of Temporal Action Detection Technology in Abnormal Event Detection of Surveillance Video. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 26958–26972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-K.; Mak, M.-W.; Li, R.; Chi, Z.; Fu, H. Action Progression Networks for Temporal Action Detection in Videos. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 126829–126844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| mAP @ tIoU (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test Set Type | 0.5 | 0.55 | 0.6 | 0.65 | 0.7 | 0.75 | 0.8 | 0.85 | 0.9 | 0.95 | Avg. |

| All | 96.86 | 96.86 | 95.97 | 94.52 | 92.99 | 89.10 | 79.39 | 54.64 | 18.82 | 2.45 | 72.16 |

| Standard | 95.43 | 95.43 | 93.84 | 92.46 | 91.66 | 89.48 | 75.27 | 52.61 | 17.57 | 0.66 | 70.44 |

| Abnormal | 96.91 | 96.91 | 96.91 | 95.57 | 93.34 | 87.58 | 76.55 | 49.52 | 21.39 | 3.25 | 71.79 |

| Test Set Type | Avg tIoU (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All | 81.17 | 96.72 | 99.66 |

| Standard | 81.96 | 96.19 | 99.36 |

| Abnormal | 80.28 | 97.32 | 99.82 |

| Classification Precision (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Matrix | Action A | Action B | Action C | Action D |

| Matrix A [44] | 99.52 | 99.36 | 91.43 | 94.95 |

| Matrix B [44] | 98.26 | 98.67 | 96.87 | 93.11 |

| Proposed | 99.68 | 99.31 | 98.79 | 99.07 |

| mAP @ tIoU (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network Design | 0.5 | 0.55 | 0.6 | 0.65 | 0.7 | 0.75 | 0.8 | 0.85 | 0.9 | 0.95 | Avg. |

| Shared | 94.55 | 94.34 | 94.21 | 93.81 | 91.87 | 78.44 | 64.99 | 40.26 | 12.82 | 1.28 | 66.66 |

| Non-shared | 96.86 | 96.86 | 95.97 | 94.52 | 92.99 | 89.10 | 79.39 | 54.64 | 18.82 | 2.45 | 72.16 |

| Test Set Type | Network Design | Avg. tIoU (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Shared | 79.37 | 93.41 | 97.31 |

| Non-shared | 81.17 | 96.72 | 99.66 | |

| Standard | Shared | 85.89 | 97.58 | 98.55 |

| Non-shared | 81.96 | 96.19 | 99.36 | |

| Abnormal | Shared | 75.10 | 87.15 | 93.27 |

| Non-shared | 80.28 | 97.32 | 99.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tao, K.; Wang, F.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y. A Lightweight Spatiotemporal Skeleton Network for Abnormal Train Driver Action Detection. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13152. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413152

Tao K, Wang F, Liu Z, Huang Y. A Lightweight Spatiotemporal Skeleton Network for Abnormal Train Driver Action Detection. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13152. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413152

Chicago/Turabian StyleTao, Kaijia, Fen Wang, Zhigang Liu, and Yuanchun Huang. 2025. "A Lightweight Spatiotemporal Skeleton Network for Abnormal Train Driver Action Detection" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13152. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413152

APA StyleTao, K., Wang, F., Liu, Z., & Huang, Y. (2025). A Lightweight Spatiotemporal Skeleton Network for Abnormal Train Driver Action Detection. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13152. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413152