Abstract

Multi-object tracking (MOT) technology integrates multiple fields such as pattern recognition, machine learning, and object detection, demonstrating broad application potential in scenarios like low-altitude logistics delivery, urban security, autonomous driving, and intelligent navigation. However, in open-world scenarios, existing MOT methods often face challenges of imprecise target category identification and insufficient tracking accuracy, especially when dealing with numerous target types affected by occlusion and deformation. To address this, we propose a multi-object tracking strategy based on multi-cue fusion. This strategy combines appearance features and spatial feature information, employing BYTE and weighted Intersection over Union (IoU) modules to handle target association, thereby improving tracking accuracy. Furthermore, to tackle the challenge of large vocabularies in open-world scenarios, we introduce an open-vocabulary prompting strategy. By incorporating diverse sentence structures, emotional elements, and image quality descriptions, the expressiveness of text descriptions is enhanced. Combined with the CLIP model, this strategy significantly improves the recognition capability for novel category targets without requiring model retraining. Experimental results on the public TAO benchmark show that our method yields consistent TETA improvements over existing open-vocabulary trackers, with gains of 10% and 16% on base and novel categories, respectively. The results demonstrate that the proposed framework offers a more robust solution for open-vocabulary multi-object tracking in complex environments.

1. Introduction

Multi-object tracking (MOT) is a crucial research topic in computer vision. It involves integrating target detection and localization technologies with feature matching and data association algorithms from deep learning to build robust models capable of predicting spatiotemporally continuous trajectories for multiple targets in video sequences, thereby maintaining identity (ID) consistency over time. In recent years, with the widespread adoption of applications such as autonomous driving, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) logistics delivery, intelligent security surveillance, and smart traffic systems, the demand for MOT technology in practical, complex, open environments has grown significantly, accompanied by numerous new challenges.

In traditional application scenarios, MOT primarily focuses on limited categories like pedestrians and vehicles. However, in open environments, tracking targets exhibit high diversity and uncertainty. For instance, wildlife monitoring requires identifying and tracking non-fixed category targets like tigers and leopards; autonomous driving systems need to promptly identify obstacles on the road such as plastic bags or bottles, which are often undefined objects; in low-altitude logistics delivery, UAVs need to achieve the continuous tracking of various dynamic targets in complex urban or rural terrains. In such scenarios, target categories are numerous and morphologically variable, often accompanied by severe occlusion, rapid deformation, illumination changes, and interference from similar appearances, making traditional tracking methods based on closed vocabulary sets difficult to adapt. Particularly in dense, complex-motion low-altitude logistics environments, imaging equipment is affected by flight attitude and ground object occlusion, easily leading to target loss or ID confusion, severely impacting the accuracy and reliability of tracking systems.

To overcome the reliance of traditional MOT methods on predefined category sets, open-vocabulary MOT has emerged. Its core objective is to leverage the powerful semantic understanding and generalization capabilities of vision–language models (e.g., CLIP) to enable the recognition and tracking of novel category targets not seen during training. Open-vocabulary methods divide categories into base classes (known) and novel classes (unknown). By training on the base class label space, the model gains the ability to recognize novel classes, significantly expanding the applicability of tracking systems. However, current research on open-vocabulary MOT is still in its early stages, and representative works like OVTrack have several shortcomings. Especially in practical scenarios with frequent target motion and severe occlusion, existing methods have considerable room for improvement in terms of target association robustness, discriminative feature extraction capability, and cross-category generalization performance. Furthermore, vision–language models themselves are not specifically designed for MOT tasks and have limitations in distinguishing between different targets with similar appearances and handling complex motion patterns and occlusion situations.

Addressing the aforementioned issues, we propose an open-vocabulary multi-object tracking framework based on multi-cue fusion. By fusing appearance features and spatial motion features, combined with the BYTE data association mechanism and a weighted IoU module, the accuracy of target association is enhanced. Simultaneously, an open-vocabulary prompting strategy is introduced, utilizing diverse sentence structures, emotional descriptions, and image quality-related text prompts to enrich semantic expression, thereby strengthening the CLIP model’s ability to recognize and generalize to novel categories, effectively identifying unknown category targets without retraining the model. Experiments on the public TAO dataset show that our method improves the TETA evaluation metric by 10% and 16% for base and novel categories, respectively, validating its good tracking accuracy and robustness in complex scenes.

To address the above challenges, we propose an open-vocabulary multi-object tracking framework that explicitly integrates multi-cue fusion and open-vocabulary prompting. Unlike OVTrack, which relies primarily on appearance cues, and ByteTrack/QDTrack, which emphasize motion-based heuristics, our approach jointly leverages appearance, motion, and spatial cues through a unified association strategy. In particular, we introduce a Height-Weighted IoU (HWIoU) module tailored to open-vocabulary tracking, enabling more reliable matching under scale variation and deformation—capabilities not present in existing MOT pipelines. Furthermore, we designed tracking-oriented prompt templates that incorporate structural, affective, and quality-aware textual variants to enhance the semantic expressiveness of CLIP, thereby improving generalization to unseen categories without retraining. Experiments on the TAO benchmark demonstrate that our approach achieves 10% and 16% TETA improvements on base and novel categories, respectively, validating its effectiveness and robustness in complex open-world scenarios.

2. Related Work

2.1. Detection-Based Multi-Object Tracking Methods

The mainstream paradigm for multi-object tracking based on deep learning is Tracking by Detection (TBD). Object detection, as a key initial step in MOT, involves identifying and precisely locating regions of interest in images. There are two general approaches to object detection: two-stage and one-stage detection. Typical two-stage detectors include the R-CNN series algorithms, such as R-CNN [1], Fast R-CNN [2], and Faster R-CNN [3]. These methods improve detection accuracy by introducing a Region Proposal Network (RPN) but at the cost of increased computational overhead. One-stage detectors treat object detection as a regression problem, directly predicting object locations and categories from images. The main idea is to slide a detection network over multiple scales to predict target size, location, and category. Representative one-stage detectors include the YOLO [4] (You Only Look Once) series and SSD [5] (Single-Shot MultiBox Detector), which offer faster detection speeds.

In the feature extraction stage of MOT, features can be categorized into strong and weak features. Strong features include appearance and motion features. Appearance features are extracted from regions of interest via detection networks, reflecting the visual appearance of targets—exemplified by models like QDTrack [6]. Motion features are obtained by predicting the motion state of targets, revealing dynamic changes between frames, as seen in classic models like DeepSORT [7]. Weak features mainly include confidence information and detection box location information. Confidence information can indicate whether a target has undergone deformation, while detection box locations help infer spatial depth information.

In complex scenarios such as occlusion, pure appearance features often exhibit significant variation. In such cases, motion features can capture the spatial movement of targets. For example, the Simple Online and Real-time Tracking (SORT) algorithm [8] first performs object detection, then uses Kalman filtering to predict target position and velocity after obtaining bounding boxes, and finally employs the Hungarian algorithm to associate detection boxes with predicted trajectories. This method requires less computation than appearance-based methods and offers better real-time performance. Wojke et al. [7] improved SORT to propose DeepSORT, which combines appearance and motion features to enhance robustness in occluded and complex motion scenarios. Recent works such as ByteTrack [9] and Tracktor [10] have further promoted the application of motion features in MOT. ByteTrack uses Kalman filtering and multi-level matching strategies to significantly reduce missed detections and trajectory fragmentation, while Tracktor simplifies the tracking process through continuous regression of detection boxes and motion models while maintaining high tracking accuracy.

Target classification plays a vital role in MOT. Traditional MOT benchmarks [11] typically define a fixed set of semantic categories for training and testing. To address MOT in open-world scenarios, researchers have extended traditional frameworks. A. Ošep et al. [12] proposed a universal tracking method based on scene segmentation, performing tracking before classification to follow arbitrary objects. Other studies have used category-agnostic locators to track arbitrary objects [13].

Recently, Liu et al. [14] defined the open-world tracking task, focusing on evaluating the model’s ability to track unseen objects. This task requires tracking before classification, presenting two main challenges: the high cost of dense annotation for all objects in open-world scenes, and the lack of a predefined category system that blurs the definition of object concepts. Liu et al. used a recall-based evaluation method, which has limitations: it does not penalize false positives (FP), thus failing to fully measure tracker precision, and its category-agnostic nature prevents the assessment of the tracker’s ability to infer semantic categories. Open-vocabulary multi-object tracking [15] aims to track multiple objects outside the training dataset, focusing on the classification problem in tracking. It uses a recall-based evaluation method and assumes that test targets are equipped with corresponding category labels. Under this premise, researchers can use existing closed-set tracking evaluation metrics [16], which capture both precision and recall and assess the tracker’s ability to follow arbitrary objects during inference. With the emergence of OVTrack [15], which replaces traditional classifiers with an embedding head to measure semantic similarity between targets and categories—specifically by aligning image features from object detection with image and text embeddings from CLIP [17]—knowledge from CLIP is integrated into the tracking framework.

In MOT, similarity measurement methods can be broadly divided into traditional metrics and deep learning-based predictive metrics. Traditional methods rely on specific distance functions to compute feature similarity, with performance heavily dependent on the chosen feature representation and distance metric. A typical example is Intersection over Union (IoU) [17,18], which evaluates target similarity between frames by calculating the overlap between detection boxes. Although computationally efficient, IoU struggles in complex scenarios with occlusion and overlapping targets due to its reliance solely on spatial information. In contrast, deep learning-based methods use models like convolutional neural networks to learn feature representations and compute similarity based on these representations. These methods capture deep semantic information, better handling appearance variations and complex background interference, and often exhibit superior performance in MOT tasks.

2.2. Appearance-Only Multi-Object Tracking Strategies

In MOT, existing research typically adopts two main technical approaches to enhance tracking robustness and achieve target re-identification using instance appearance similarity: building independent appearance feature extraction models or integrating additional embedding heads into end-to-end trainable detection frameworks. However, these methods essentially rely on image similarity learning strategies to model appearance similarity. Metrics such as cosine distance are commonly used to compute feature similarity between instances.

Appearance similarity learning is formalized into two typical paradigms: one treats the number of identities N in the training set as the classification dimension to construct an N-class classification task; the other uses triplet loss functions to constrain the feature space. Both paradigms have significant limitations in practice: the former faces scalability issues in large-scale datasets, while the latter struggles to establish discriminative relationships in the global feature space with only triplet constraints.

Unlike these methods, QDTrack [6], as a pure appearance-based algorithm, employs a dense similarity learning method, densely sampling hundreds of regions on image pairs for contrastive learning. This approach can be combined with existing detection methods to form quasi-dense tracking without relying on displacement regression or motion priors. The resulting unique feature space allows efficient target matching via simple nearest-neighbor search during inference.

2.3. Spatially Based Multi-Object Tracking Strategies

Spatially based MOT strategies are widely used, particularly in high-frame-rate real-time tracking tasks. When the inter-frame interval is short, object motion is minimal and can be approximated as linear, making spatial information an important and accurate indicator for short-term association. ByteTrack [9] is a widely used spatially based MOT method that improves upon DeepSORT [7]. Instead of simply discarding low-confidence detection boxes, ByteTrack retains them for continued matching, reducing identity switches caused by object motion or occlusion. The tracking process of ByteTrack involves inputting video frames, performing object detection to obtain detection boxes, dividing boxes into high- and low-confidence sets, using Kalman filters to predict the current positions of existing trajectories, matching high-confidence detection boxes with predicted trajectories using the Hungarian algorithm, matching unmatched trajectories with low-confidence detection boxes, creating new trajectories for unmatched high-confidence boxes with sufficient confidence, and updating or discarding unmatched low-confidence boxes based on requirements. The updated trajectory set represents the tracking paths of all targets in the video. These improvements allow ByteTrack to effectively handle occlusion, motion, and identity switches, significantly enhancing tracking stability and accuracy. Recent HybridSORT [19] leverages both representation and motion information for MOT.

2.4. Open-Vocabulary Multi-Object Tracking

Open-vocabulary multi-object tracking [15] primarily uses open-vocabulary learning to extend the tracker’s capability to novel categories beyond the training set, including both seen and unseen classes during training. Open-vocabulary trackers are initially trained on known categories and leverage large amounts of additional image–text data to acquire rich knowledge for handling open-vocabulary scenarios. This knowledge is extracted and integrated into the MOT framework to further optimize training and alignment, transforming closed-set MOT trackers [6] into open-vocabulary trackers capable of effectively detecting both seen and unseen objects. Open-vocabulary MOT not only tracks seen objects but also handles entirely new, unseen categories. It combines open-vocabulary object detection [20] with traditional MOT methods [6]. Current open-vocabulary MOT frameworks generally adopt a staged approach, decoupling open-vocabulary detection and MOT into independent processing modules.

Unlike existing MOT methods, we propose a multi-cue fusion strategy combining appearance, motion, and spatial information to better handle complex scenarios such as occlusion and deformation. Traditional methods often rely on single features, limiting their performance in dynamic and complex environments. The proposed method also introduces an open-vocabulary prompting strategy, enhancing the model’s ability to recognize unseen targets through a vision–language model without retraining. This allows the model to adapt more flexibly to new target categories in open-world scenarios. Compared to traditional detection-based MOT methods, the proposed approach demonstrates higher accuracy and robustness, promising practical applications in areas such as low-altitude logistics delivery and urban security.

3. Multi-Object Tracking Based on Open Vocabulary and Multi-Cue Fusion

3.1. Algorithm Architecture

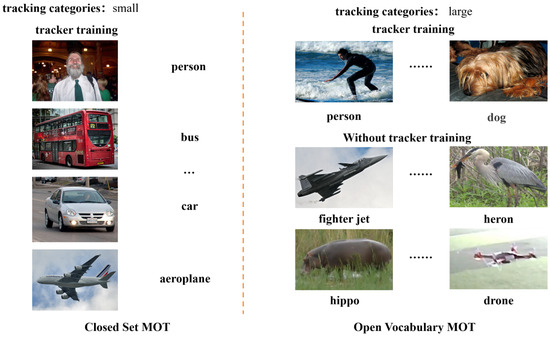

As illustrated in Figure 1, open-vocabulary MOT involves a substantially richer set of category-level textual descriptions compared to conventional closed-set tracking. To effectively utilize this information, we first introduce a caption parser that extracts candidate category phrases using a scene parser [21], followed by a pre-trained vision–language model that computes image–text similarity for open-vocabulary detection. Building on this, our tracker performs multi-cue joint association—integrating appearance, motion, and spatial cues—to robustly assign identities, as depicted in Figure 2. This formulation enables open-vocabulary tracking without requiring category-specific model retraining.

Figure 1.

Category differences between open-vocabulary and traditional multi-object tracking. The open-world scenarios involve more category text information than closed-set MOT. By introducing a caption parser, category information is extracted from captions using a scene parser [21], and a pre-trained vision–language model is used to process similarity information between images and categories.

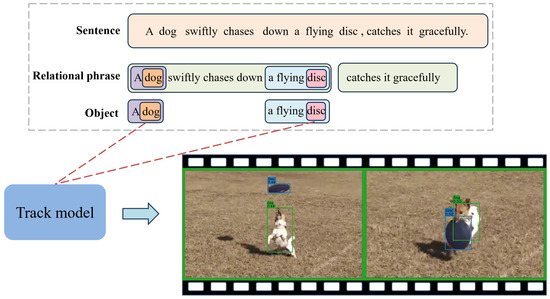

Figure 2.

Open-vocabulary tracking framework based on multi-cue fusion. A tracker associates targets to achieve MOT for the specified categories.

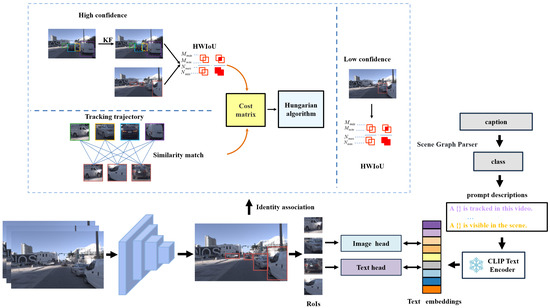

To address deformation and occlusion in open scenarios, a multi-cue fusion association strategy is introduced, with prompts adjusted for the MOT context. The detailed overall algorithm architecture is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Overall algorithm architecture. The proposed method builds on object detection, pre-trained vision–language model classification, and multi-cue fusion association. It uses a Faster R-CNN [2] detector to detect objects in videos and the CLIP vision–language model to obtain category labels and combines strong motion–appearance cues with weak bounding box height cues for target association.

3.2. Open-Vocabulary Object Detection

3.2.1. Object Detector

This study uses a backbone network based on ResNeXt-50 [22] and a Feature Pyramid Network, with Faster R-CNN as the detector. Faster R-CNN is a two-stage detector. In the first stage, it generates numerous candidate regions (proposals) with a Region Proposal Network (RPN). To localize objects of arbitrary and potentially unknown classes in videos, the Region Proposal Network and regression loss defined in [3] are used. This localization detection process [23] generalizes well to object classes unknown during training. During training, the RPN is used as the object proposer M to achieve greater diversity, while during inference, the R-CNN output is used as the object proposals. Each proposal is defined by a confidence score and a bounding box . The detector’s final stage is connected to the pre-distilled vision–language model CLIP for classification.

3.2.2. Open-Vocabulary Object Detection Pre-Training

This study used the DetPro [24] method combined with ViLD to extract the vision–language model CLIP and its pre-trained prompts. The CLIP model consists of a text encoder T and an image encoder I. T takes prompts representing classes as input and outputs corresponding text embeddings (class embeddings). I takes an image resized to 224 × 224 as input and outputs the corresponding image embedding.

The method [23] distills a two-stage object detector (student model) using a pre-trained open-set classification model as the teacher model. Specifically, the teacher model is used to encode category text and generated proposals, training the student detector to align text and region features. Let denote the region embedding, where is the backbone model and is a lightweight head generating the region embedding (the output before the classification layer).

The classifier of Faster R-CNN [3] is replaced with a text embedding processing module. The goal of this module is to train the region embeddings to enable classification via text embeddings. The loss function for the text embedding processing module can be written as

Here, softmax is the loss function for the text embedding processing module. The text embedding processing module uses only the text embeddings of the base categories for training. Regions that do not match any ground truth label in are assigned to a background category. Since the word “background” may not well represent these unmatched regions, the background category learns its own embedding . The cosine similarity between each region embedding and all category embeddings (including and ) is computed. A softmax activation function with temperature is applied to calculate the cross-entropy loss. To train the first stage (RPN) of the two-stage detector, regions extracted by the detector are utilized, and the detector is initialized and trained using the text embedding processing module.

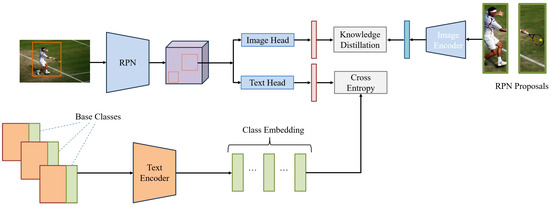

The overall detector training framework is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Open-vocabulary detector training and data distillation process. Text encoder distillation is performed only from base classes. Category names are input into the pre-trained text encoder to obtain text embeddings, and the inferred text embeddings are used to classify the detected regions. Image encoder distillation is performed from both base and novel classes because the proposal network might detect regions containing novel classes. First, the object proposal regions are filtered using the NMS algorithm [3], and then cropped from the original image. The cropped regions are fed into the image encoder of the CLIP model. The output of the vision–language model’s image encoder serves as the teacher region features. Subsequently, a Faster R-CNN detector is trained to learn the output of the teacher network, aligning the student output with the teacher image feature embeddings.

Image encoder distillation is introduced to extract image embeddings, aiming to distill knowledge from the pre-trained vision–language model image encoder V (teacher model) into the object detector (student model). is used for distillation.

Here, the method aims to align the region embedding with the introduced image embedding . To improve training efficiency, M regions are extracted for each training image, and the corresponding M image embeddings are precomputed. The candidate regions can contain objects from both base and novel categories. In contrast, the text encoder can only learn from base categories . An L1 loss is applied between the region and image embeddings to minimize their distance.

3.3. Multi-Cue Fusion Target Association Strategy

In open-world scenarios, target motion is complex and variable, prone to deformation, making methods relying solely on appearance matching ineffective under complex conditions like occlusion and deformation [24]. For example, in pedestrian and vehicle MOT scenarios (e.g., MOT17 [25]), target color changes are insignificant and displacement is small. However, in open-world scenarios, targets may undergo significant appearance changes due to their own motion, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Appearance variations in traditional MOT scenes vs. open-vocabulary MOT scenes.

To alleviate these problems, introducing a multi-cue fusion target association strategy can effectively mitigate the aforementioned challenges. This involves using strong cues like motion mixed with appearance, and weak cues like candidate bounding box height for target association. Appearance-based matching methods primarily use category-sample-based matching to find candidate associations for a query object within tracklets.

The BYTE method is adopted to obtain motion cues, tracking targets by associating every detection box in the video, not just high-score boxes. This method excels in addressing issues of missed detections and track fragmentation caused by target occlusion or blurring, significantly enhancing track completeness and accuracy. Almost all detection boxes are retained and categorized into high-score and low-score boxes. In the processing pipeline, high-score boxes are first associated with previous tracks. Due to factors like occlusion, motion blur, or target size changes, some previous tracks might not find suitable high-score matches. Low-score boxes are then associated with these unmatched tracklets, recovering target objects from low-score boxes while effectively filtering out background information.

The association IoU is calculated using the Height-Weighted IoU (HWIoU) method. This method combines the maximum and minimum heights of the predicted box and the detection box from the previous frame to assess the intensity of target motion, weighting the motion cue accordingly to judge its reliability. After obtaining the motion cue, it is combined with the appearance cue to obtain the final target object similarity value. The Hungarian algorithm is then used for ID assignment.

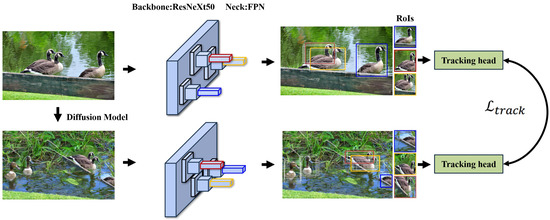

Tracker Module Training: The LVIS dataset [26], a large-scale image dataset with diverse categories and complex scenes, is used as the training set to train the tracker. The training flowchart is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Training flowchart for the multi-cue fusion target association strategy.

For each image in LVIS, a reference image is generated using the DDPM [27] data diffusion method. Instance similarity loss is used, employing the contrastive learning method from [6] for tracking training. The loss functions are calculated as shown in Equations (5)–(7).

Here, Regions of Interest (RoIs) are extracted from the corresponding feature maps of and , and the IoU method is used to match these RoIs with annotations. For each matched RoI in the reference image , an appearance embedding (feature vector) is extracted. In , positive examples are used to cluster objects with the same identity, and negative examples with different identities are separated. An auxiliary loss function is applied to control the output scale of the model’s final layer.

Appearance similarity learning is achieved by increasing the distance between positive and negative examples. Traditional data augmentation techniques like translation, scaling, and rotation are used to simulate video effects.

During testing, the BYTE method and HWIoU module are used, combined with appearance features for MOT. The Height-Weighted IoU calculation is shown in Equations (8) and (9).

Here, and represent the detection box and prediction box, respectively. The input to this method is a video sequence , an object detector , and a detection threshold . For each frame in the video, the detector predicts detection boxes and scores. These are divided into high-confidence detection boxes and low-confidence detection boxes based on , along with existing tracks T. For high-score boxes, a Kalman filter is used to predict the new position of each target from the previous frame in the current frame. In the current frame, corresponding feature embeddings are extracted for these high-score boxes. Cosine similarity and bisoftmax are used to measure the appearance similarity between target embeddings and matching candidates. The formulas for cosine similarity and bisoftmax appearance similarity are shown.

Here, suppose there are H high-confidence targets in the current frame with feature embeddings h and M matching candidates from the past x frames with feature embeddings e. Appearance similarity is used as a re-identification feature, incorporated into the cost matrix, and the Hungarian algorithm is used for matching based on this similarity.

Here, unmatched high-confidence detection boxes are used to generate new tracklets. Unmatched tracks are retained in . For low-confidence detection boxes and the remaining tracks , association is performed using HWIoU matching. Tracks that remain unmatched by both low- and high-confidence boxes are placed into . Tracks in continue to be tracked and matched; they are only deleted if they remain unmatched for a certain duration. was set to be 0.6 in this study.

3.4. Open-Vocabulary Prompting Strategy for Multi-Object Tracking

In research on vision–language models like CLIP, text–image pairs typically consist of complete sentences rather than single words. This pairing method helps improve model performance. To bridge the vocabulary distribution gap in text–image pairing, research has found that using “prompt” text effectively enhances classification performance. For the open-vocabulary MOT task, CLIP’s ability to recognize novel categories is enhanced by adapting the “prompt” text. However, since CLIP’s weights are frozen and retraining requires substantial computational resources, prompt tuning becomes an effective means to improve task adaptability.

This study proposes a new image description template specifically designed for large-vocabulary scenarios. Compared to traditional methods, this template employs more diverse sentence structures, such as “This is a photo of a category” and “This is one category in the scene”. The template also introduces emotional descriptions (e.g., “a photo of a clean category” or “a dark photo of the category”), increasing the expressiveness and personalized characteristics of the text. By refining descriptions related to image quality, such as “a low resolution photo of a category”, the model’s classification ability for novel categories is significantly improved.

3.5. Interaction Between BYTE, HWIoU, Appearance Embeddings, and Prompt-Enhanced CLIP Features

To provide a clearer description of the methodology, we explicitly explain how the different cues interact within the proposed association framework. First, the open-vocabulary detector produces region-level appearance embeddings that have been enriched by our tracking-oriented CLIP prompts, enabling stronger visual discrimination for both base and novel categories. These embeddings form the appearance similarity branch in the association module. Second, the BYTE strategy performs a two-stage matching process, where high-confidence detections are first matched using appearance similarity combined with motion predictions from a Kalman filter. For unmatched trajectories, a second-stage association is conducted using low-confidence detections. In this stage, we introduce the Height-Weighted IoU (HWIoU) as a geometry-aware cue that emphasizes height consistency between predicted and detected boxes, which is particularly beneficial in open-vocabulary scenarios where object shapes and scales vary widely. Finally, appearance similarity, motion cost, and HWIoU are normalized and fused into a unified cost matrix before Hungarian matching. This integrated design ensures that CLIP-enhanced semantics guide the model toward correct category discrimination, while BYTE and HWIoU provide robust spatiotemporal constraints to mitigate occlusion, deformation, and large-scale variations.

4. Experiments and Result Analysis

4.1. Datasets

In the dataset configuration, the training dataset used was the LVIS dataset, a large-scale, fine-grained vocabulary dataset with approximately 2 million high-quality instance segmentation annotations for over 1000 object categories, containing about 164k images. The validation and testing datasets use the TAO dataset. TAO is the first large-scale dataset for general multi-object tracking, including 2907 videos and 833 object categories.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

To quantitatively analyze the open-vocabulary tracking performance of the model, this study adopted the Tracking-Every-Thing Accuracy (TETA) [16] metric from the MOT field. The calculation method is shown in Equation (12).

Here, the TETA metric decomposes tracking measurement into three factors: Localization Accuracy (LocA), Association Accuracy (AssocA), and Classification Accuracy (ClsA). A higher metric indicates better performance. TETA already covers the functional dimensions that traditional metrics measure while additionally incorporating open-set classification, making it better aligned with the goals of this work.

4.3. Experimental Setup

This experiment employed the testing environment based on the PyTorch v2.9.0 deep learning framework, using the Ubuntu 20.04 operating system, a GeForce RTX 4090 GPU accelerated with CUDA 11.1, and an Intel® Xeon® Gold 6430 CPU. With this setup, the proposed framework achieves an average inference speed of 28–33 ms per frame (approximately 30–35 FPS). The open-vocabulary detection module requires approximately 45–55 GFLOPs, while the multi-cue tracking and association components introduce an additional 20–30 GFLOPs, resulting in a total computational cost of around 70–85 GFLOPs.

This study implemented an object tracking model incorporating a ResNeXt-50 backbone network. The backbone was pre-trained on the ImageNet-1K dataset and trained using the LVIS dataset. For the training process, the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer was used with a learning rate of 0.02, momentum of 0.9, and weight decay of 0.0001. A step decay strategy was employed, reducing the learning rate after the third and fifth epochs. (All models were trained for 24 epochs, with the learning rate decaying in a step-wise manner at 2/3 and 5/6 of the total training rounds (i.e., at the 16th and 20th epochs); linear warmup was applied at the beginning of training.) The classification loss used cross-entropy loss, the bounding box regression loss used L1 loss, the tracking loss used multi-positive cross-entropy loss, and the auxiliary tracking loss used L2 loss. During testing, multi-scale flipping augmentation was used, images were resized to (1333, 800), and normalization, padding, and tensor conversion were applied.

4.4. Comparative Experiments

Table 1 lists the training data configurations designed for the TAO validation and test sets. Furthermore, Table 2 presents the experimental evaluation results on the TAO validation set. Table 3 shows the evaluation results on the TAO test set. Categories in the dataset are divided into base and novel categories.

Table 1.

Training data settings on TAO validation and test sets.

Table 2.

Comparative experiments on the TAO validation set.

Table 3.

Comparative experiments on the TAO test set.

The `TAO’ data column indicates training using TAO video sequences, while the `LVIS’ column indicates training using the LVIS dataset. The established baselines include both closed-set trackers and open-vocabulary trackers. Two state-of-the-art closed-set trackers, TETer [16] and QDTrack, which were trained on both novel and base categories, were selected. The off-the-shelf trackers DeepSORT and Tracktor++ [10] combined with the open-vocabulary detector ViLD served as baseline open-vocabulary trackers. These trackers, like OVTrack, were trained only on base categories. Our method and OVTrack used only static images for training, while other methods used video data for training.

Specifically, considering the characteristics of the open-vocabulary scenario, the test samples were divided into two subsets: base (categories seen during training) and novel (categories not seen during training).

On the TAO validation set (Table 2), the tracker utilizing the multi-cue fusion association strategy and MOT prompts improves the TETA metric by 5% on base categories and 15% on novel categories compared to the OVTrack model.

In Table 3, on the TAO test set, the tracker employing a multi-cue fusion association strategy and multi-object tracking prompts achieves a 10% improvement in the TETA metric for base classes and a 16% improvement for novel classes compared with the OVTrack model.

In the open-vocabulary tracking task on the TAO test set, the proposed method demonstrates clear advantages. Compared with the state-of-the-art OVTrack model, the TETA scores for both base and novel classes are improved, validating the generalization effectiveness of the multi-cue fusion strategy and tracking prompt mechanism. The association metric for base classes increases from 35.4 to 39.4, indicating that the multi-cue fusion strategy significantly enhances association performance. Meanwhile, compared with a closed-set tracker combined with an open-vocabulary detector, the proposed method achieves noticeably better classification performance on novel classes. Moreover, by leveraging visual–language model prompts, the model exhibits improved recognition capability for unseen categories compared with closed-set trackers.

4.5. Ablation Studies

Following the comparative experiments above, Table 4 compares the proposed algorithm model using the track prompt against using only a single prompt, CLIP’s prompt mechanism, ViLD’s prompt, OVTrack’s prompt, and a prompt template generated by GPT-4o [28] on the TAO validation set. The experimental results indicate that for the tracking model using only a single prompt template, the classification ability for novel classes significantly decreases compared to the OVTrack work, with its ClsA metric dropping by 0.9. This result highlights the limitations of a single prompt template in open-vocabulary scenarios. After introducing the track prompt, compared to the OVTrack work, the classification metric for base classes increases by 0.2, and for novel classes by 2.6. After incorporating the track prompt, the model shows minor fluctuations in LocA and AssocA metrics, while the ClsA for novel categories is effectively improved, enhancing the model’s generalization ability in open-vocabulary scenarios.

Table 4.

Ablation study on prompt templates on the TAO validation set.

Compared to other prompts, the model using the CLIP prompt shows decreased classification performance on base categories, but improved classification and association performance on novel categories. For the model using the ViLD prompt, classification performance on base categories decreases while association performance increases; classification performance on novel categories improves, but association performance declines. For the model using visual–language prompts generated by the large language model GPT-4o, localization and association effects on base classes decrease significantly, although classification improves; localization and association effects on novel classes also decrease noticeably, but classification performance improves.

In Table 5, using OVTrack as the baseline model, and employing the aforementioned vision–language model tracking prompts, we analyzed the use of only the BYTE method to obtain motion cues combined with appearance cues for target association and then added the HWIoU and WWIoU (Width-Weighted IoU) modules for experiments.

Table 5.

Ablation study on association modules on the TAO validation set.

Experiments on the TAO validation set show that using only the BYTE method improves the association capability for both base and novel classes compared to the baseline model, increasing the AssocA metric for base and novel classes by 13% and 5%, respectively. Using the BYTE method with the Width-IoU module increases the novel class AssocA metric by 2%, while using it with the Height-IoU module increases the novel class AssocA metric by 3%, proving that the width and height information of detection boxes have a certain influence on capturing target motion. Adding the Height-Weighted IoU module has a minor impact on target localization and classification performance. The BYTE method, along with the Height-Weighted and Width-Weighted IoU modules, has a greater impact on the model’s association capability and a weaker effect on classification ability.

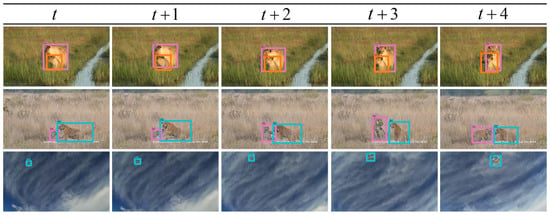

In Table 6, experiments on the TAO test set show that using only the BYTE method increases the AssocA metric for base and novel classes by 8% and 9%, respectively. Using the BYTE method with the Width-IoU module increases the novel class AssocA metric by 3%, and using it with the Height-IoU module also increases the novel class AssocA metric by 3%. These results confirm that the width and height information of candidate boxes positively influences capturing target motion, contributing to improved multi-object tracking performance in open-vocabulary scenarios. Figure 7 shows partial tracking results of the proposed algorithm, including different target categories. It can be observed that the proposed algorithm achieves high accuracy in the open-vocabulary object tracking task, with fewer missed detections and false alarms, effectively tracking the motion trajectories of targets. Notably, even for the untrained ‘drone’ category, the proposed tracker can robustly track its flight trajectory in the air.

Table 6.

Performance comparison on testing set with different methods.

Figure 7.

Partial object tracking results on the TAO dataset.

Figure 7 shows partial tracking results of the proposed algorithm, including different target categories. It can be observed that the proposed algorithm achieves high accuracy in the open-vocabulary object tracking task, with fewer missed detections and false alarms, effectively tracking the motion trajectories of targets. Notably, even for the untrained ‘drone’ category, the proposed tracker can robustly track its flight trajectory in the air.

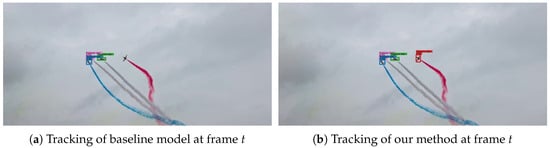

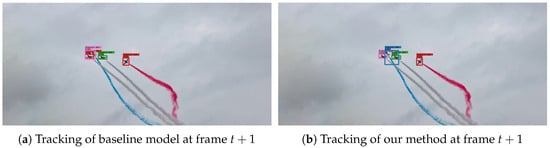

To visually demonstrate the improvement, the proposed method was tested on untrained video data and target categories, compared with the baseline model. Different bounding box colors represent different targets. At frame t Figure 8, the baseline model detects three performing fighter jets, missing one. The fighter jet detected by the blue bounding box is climbing rapidly and is about to be occluded by the fighter jet detected by the pink bounding box. The proposed model detects all four performing fighter jets at frame t. At frame Figure 9, the baseline model, using a pure appearance strategy for target association, misidentifies the fighter jet represented by the blue box at frame t as the fighter jet from the pink box at frame t, resulting in an incorrect ID assignment. Meanwhile, the pink fighter jet from frame t is considered a new appearance and is represented by a red bounding box at frame . In contrast, the proposed model, utilizing the multi-cue fusion target association strategy, maintains the ID assignment (blue box) for the rapidly climbing fighter jet from frame t even after occlusion with the pink-box fighter jet at frame . The ID of the fighter jet represented by the pink box at frame also remains consistent with frame t. There is no ID switch due to deformation and occlusion before and after the event, demonstrating that the multi-cue fusion strategy has a certain effect on mitigating occlusion and deformation.

Figure 8.

Multi-object tracking comparison at frame t.

Figure 9.

Multi-object tracking comparison at frame .

5. Discussion

This paper presents an open-vocabulary multi-object tracking framework that integrates multi-cue fusion with enhanced text–visual alignment. Using a caption parser to extract category-related textual cues and incorporating them into a vision–language model, the method improves the quality of open-vocabulary detection. During tracking, the algorithm jointly leverages appearance, motion, and spatial cues; adopts BYTE-style association; and introduces HWIoU to stabilize matching under scale variation. The high–low confidence separation and secondary matching further improve the utilization of detection results.

The effectiveness of our framework in open-vocabulary settings stems from the complementary strengths of its components. HWIoU provides more stable spatial affinity by mitigating scale drift and deformation, which are common in unseen categories where standard IoU becomes unreliable. Motion cues further compensate for appearance inconsistencies, especially when CLIP features are weak for sparsely supervised or novel classes. In addition, our tracking-oriented prompt templates enhance image–text alignment by enriching contextual descriptions beyond generic CLIP prompts, improving the recognition of rare or unseen categories. Together, these choices yield more robust associations and explain the observed gains on both base and novel categories.

Despite the consistent improvements achieved by our method across both base and novel categories, several limitations merit consideration. First, the qualitative examples included in this study are selective and do not fully illustrate failure cases or long-sequence ID-consistency, which are important for evaluating tracking robustness in challenging scenarios. Second, the method’s performance depends on the quality of CLIP-derived features; suboptimal or misaligned features may limit generalization to certain unseen categories or domains. Third, although the computational overhead of our framework is moderate on contemporary hardware, it remains higher than that of simpler baseline methods, which may constrain deployment in real-time or resource-limited settings. Addressing these limitations—through more comprehensive qualitative analyses, systematic failure case reporting, improved feature adaptation, and optimized computational efficiency—constitutes an important direction for future work.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposed an open-vocabulary multi-object tracking algorithm based on multi-cue fusion. The algorithm uses a caption parser to extract textual information, enhancing the text processing capability of the vision–language model. During the tracking phase, it combines location, motion, and appearance cues, adopts the BYTE data association method and the HWIoU module, categorizes detection boxes into high- and low-confidence levels, and performs secondary matching for unmatched tracks, thereby effectively utilizing detection boxes for target association. Compared with appearance-only baselines, the proposed framework offers more reliable localization and moderate association gains, leading to consistent TETA improvements on both base and novel categories. However, Classification Accuracy for many low-frequency novel classes remains limited, indicating that open-vocabulary recognition in long-tailed settings is still a challenging problem. Overall, the framework provides a stronger and more balanced solution for open-world MOT, while leaving room for future work on improving fine-grained novel-class classification.

In multi-object tracking based on multi-cue fusion and open-vocabulary learning, the model’s generalization ability largely depends on the recognition capability of the vision–language model. However, there is a contradiction between the high computational complexity of vision–language models and the real-time requirements of multi-object tracking. With advancements in vision–language model technology, video-scene-based vision–language models are expected to emerge. Future open-vocabulary multi-object tracking might involve joint end-to-end training with vision–language models. This would allow the algorithm to better leverage spatiotemporal information, demonstrating powerful adaptability and robustness in more complex and open scenarios, while achieving a better balance between computational efficiency and tracking accuracy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.X.; methodology, L.X. and C.L.; software, L.N. and J.B.; formal analysis, C.L.; resources, L.N. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.X.; writing—review and editing, C.L.; visualization, L.N. and J.B.; supervision, C.L.; project administration, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the QinXin Talents Cultivation Program: Beijing Information Science and Technology University, No. QXTCPB202105.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Proceedings, Part I; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, T.; Huang, T.E.; Pang, J.; Qiu, L.; Chen, H.; Darrell, T.; Yu, F. Qdtrack: Quasi-dense similarity learning for appearance-only multiple object tracking. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 15380–15393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojke, N.; Bewley, A.; Paulus, D. Simple online and realtime tracking with a deep association metric. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Beijing, China, 17–20 September 2017; pp. 3645–3649. [Google Scholar]

- Bewley, A.; Ge, Z.; Ott, L.; Ramos, F.; Upcroft, B. Simple online and realtime tracking. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 25–28 September 2016; pp. 3464–3468. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, P.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, D.; Weng, F.; Yuan, Z.; Luo, P.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Bytetrack: Multi-object tracking by associating every detection box. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, P.; Meinhardt, T.; Leal-Taixe, L. Tracking without bells and whistles. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 941–951. [Google Scholar]

- Milan, A.; Leal-Taixé, L.; Reid, I.; Roth, S.; Schindler, K. MOT16: A benchmark for multi-object tracking. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.00831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ošep, A.; Hermans, A.; Engelmann, F.; Klostermann, D.; Mathias, M.; Leibe, B. Multi-scale object candidates for generic object tracking in street scenes. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Stockholm, Sweden, 16–21 May 2016; pp. 3180–3187. [Google Scholar]

- Ošep, A.; Voigtlaender, P.; Weber, M.; Luiten, J.; Leibe, B. 4D generic video object proposals. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; pp. 10031–10037. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zulfikar, I.E.; Luiten, J.; Dave, A.; Ramanan, D.; Leibe, B.; Ošep, A.; Leal-Taixé, L. Opening up open world tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 19045–19055. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Fischer, T.; Ke, L.; Ding, H.; Danelljan, M.; Yu, F. Ovtrack: Open-vocabulary multiple object tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 5567–5577. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Danelljan, M.; Ding, H.; Huang, T.E.; Yu, F. Tracking every thing in the wild. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 498–515. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.; Wu, Y.; Cen, F.; Wang, G. Mdfn: Multi-scale deep feature learning network for object detection. Pattern Recognit. 2020, 100, 107149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Han, G.; Yan, B.; Zhang, W.; Qi, J.; Lu, H.; Wang, D. Hybrid-sort: Weak cues matter for online multi-object tracking. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 6504–6512. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Wei, F.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, M.; Gao, Y.; Li, G. Learning to prompt for open-vocabulary object detection with vision-language model. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 14084–14093. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Mao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Li, L.; Sun, W.; Ma, W.Y. Unified visual-semantic embeddings: Bridging vision and language with structured meaning representations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 6609–6618. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Girshick, R.; Dollár, P.; Tu, Z.; He, K. Aggregated residual transformations for deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1492–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.; Lin, T.Y.; Kuo, W.; Cui, Y. Open-vocabulary object detection via vision and language knowledge distillation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.13921. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Cao, J.; Song, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Yuan, J. Track to detect and segment: An online multi-object tracker. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 12352–12361. [Google Scholar]

- Dendorfer, P.; Ošep, A.; Milan, A.; Schindler, K.; Cremers, D.; Reid, I.; Roth, S.; Leal-Taixé, L. Motchallenge: A benchmark for single-camera multiple target tracking. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 845–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Dollar, P.; Girshick, R. Lvis: A dataset for large vocabulary instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 5356–5364. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).