Abstract

Physical fitness and psychomotor performance can play a crucial role in decision-making ability, reaction time, and movement time among female handball players at different age levels. Our study aimed to compare the physical fitness performance and psychomotor abilities among trained young female handball players from different age groups (U14 vs. U16). The study group included 61 female handball players (U14 = 26; ) and U16 = 35; ). The Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare the performance of physical fitness and psychomotor abilities between groups (U14 and U16). Afterward, the Pearson product-moment correlation was used to explore the relationship between physical fitness and psychomotor abilities performance among all participants. Results showed that zig-zag with the ball (s) had a significant correlation with movement time (ms) in the Spatial Attention Test (SPANT) (r = 0.30). The plate tapping test (s) emerged as a strong indicator of psychomotor speed (ms), showing significant correlations with a range of variables, including Simple Reaction Time Test (SIRT) movement time (r = 0.48), Choice Reaction Time Test (CHORT) movement time (r = 0.57), Hand–Eye Coordination Test (HECOR) reaction time (r = –0.48), HECOR movement time (r = 0.69), SPANT reaction time (r = 0.63), and SPANT movement time (r = 0.52). These findings have implications for the development of trained young female handball players. Training programs may benefit from age-specific emphasis, focusing more on fundamental coordination and reaction-based exercises in younger athletes and progressively incorporating cognitively demanding drills for older adolescents.

1. Introduction

Handball is a high-intensity, multidimensional sport that demands a blend of strength, speed, agility, coordination, and rapid decision-making [1]. Many studies consistently show that structured training leads to significant improvements in sprinting, jumping, change of direction, upper and lower limb strength, and repeated sprint ability [2,3]. Therefore physical fitness is fundamental for the development and performance of youth female handball players, particularly in the U14 and U16 age groups [4]. Well-developed physical fitness enhances game performance, supports technical and tactical skill execution [5,6]. Additionally, physical fitness qualities like agility, coordination, and muscle mass are positively associated with technical skills such as throwing, dribbling, and defensive actions [7,8,9].

On the other hand psychomotor abilities among trained young female handball players have garnered attention within sports science, particularly considering the sport’s unique physiological and psychological demands [10,11]. Psychomotor abilities encompass a range of skills, including coordination, speed, agility, and strength, all of which are essential for successful handball performance [10,12]. Moreover many studies show that players competing at higher levels exhibit significantly faster reaction times and superior psychomotor abilities. Notably, there is also evidence of a relationship between body composition (e.g., BMI, body fat percentage) and psychomotor test results, with higher BMI and fat content associated with slower reaction and movement times [13,14,15,16].

In terms of psychomotor abilities, research indicates that these skills tend to develop significantly with both age and experience in sports activities [17]. Other studies have shown that coordination-related tasks improve as children grow, and these improvements are accentuated through participation in organized sports [18]. Specifically, differences in psychomotor skills become apparent between 12–29 years old, with older groups typically demonstrating superior cognitive-motor integration during competitive scenarios [19]. Moreover, Lander et al. that less experienced female athletes tend to exhibit enhanced speed and agility compared to their more experienced counterparts, as supported by the literature on age-related performance benchmarks [20]. In handball, age-related declines in physical fitness have been documented, with U15 players demonstrating superior sprinting and jumping abilities, which are essential for the high-intensity demands of the sport [21]. Furthermore, physical fitness differences among age cohorts of female athletes often relate to physiological and developmental factors. It has been established that as girls transition from adolescence to adulthood, improvements in muscular strength, endurance, and aerobic capacity are evident. For instance, data show that female athletes in various age groups, such as U18 and U20, exhibit higher muscular strength compared to normative data, potentially due to the competitive nature of sports necessitating higher strength levels. Furthermore, research indicates that older female athletes tend to perform better in agility and precision tasks, as motor skills and nervous system development improve with age [18]. This assertion is supported by findings from [22], who highlighted performance differences based on age and sex, observing that physical fitness attributes, such as strength, tend to improve as athletes mature. Additionally, a review comparing fitness levels in youth athletes noted significant gains in muscular endurance across age groups [22,23].

Consideration should also be given to reaction time, movement time, and decision-making abilities among youth handball players, which can be understood in the context of their development across various age groups. These psychomotor abilities are critical in handball, where rapid responses and efficient movement execution can significantly influence game play outcomes. For instance, ref. [6] analyzed the psychomotor abilities of professional handball players and noted that athletes with less training seniority typically exhibit slower reaction times compared to the group of handball players with more than 14 years of training experienced. This pattern may be attributed to the development of the central nervous system, which affects how quickly athletes can respond to stimuli. However, notable variability remains among youth players, with younger age groups generally demonstrating longer reaction times due to less developed motor skills and cognitive processing capabilities [24]. Moreover, previous research has reported that younger players often take longer to execute movements than older and more experienced athletes. Therefore, training at younger ages should focus on skills that enhance both motor time and movement efficiency [12].

Furthermore, some research highlights that U8-U9 players often struggle with decision-making, as they may lack the practical experience necessary to respond optimally in situational contexts [17]. It has been observed that the decision-making speed and accuracy of U8-U9 players improve with increased exposure to competitive play, which fosters a better understanding of game dynamics and enhances situational awareness [17]. Moreover, adapting the training framework to include game-specific scenarios and small-sided games can dramatically strengthen decision-making skills. Jurišić et al. found that these formats not only improve physical performance but also enhance cognitive functions necessary for making quick decisions during matches [3]. Overall, psychomotor abilities, such as reaction time, movement time, and decision-making, exhibit notably different developmental trajectories across age groups in youth handball players. Younger players typically exhibit longer reaction and movement times, as well as slower and less effective decision-making capabilities. For this reason, the connection between physical fitness performance and psychomotor abilities can be foundational to success in young female handball players, underpinning both their athletic and psychomotor development. Therefore the interplay between physical fitness and psychomotor abilities forms the cornerstone of performance in trained young female handball players [5].

However, the literature on psychomotor abilities and performance in young female handball players is still scarce, as most previous studies have primarily focused on male participants. On the other hand, there is a lack of details on the relationship between physical fitness components and psychomotor abilities, which might be relevant at the early stages of handball players’ development. Addressing this gap is essential, as scientific research in this area is crucial for deepening our understanding of developmental processes and for informing handball evidence-based training.

Therefore, the aims of the current study were twofold: (1) to analyze and compare psychomotor abilities and physical fitness performance among trained young female handball players from different age groups (U14 vs. U16), and (2) to examine the relationship between psychomotor abilities and physical fitness components. Moreover, we have formulated hypotheses for our research: (1) U16 handball players achieve better results in complex psychomotor tests than U14 players, (2) In contrast, U14 handball players achieve better results in simple Hand–Eye Coordination tasks than U16 players and (3) components of physical fitness show significant correlations with psychomotor abilities in both age groups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study included 61 young trained female handball players aged years, divided into two age categories: U14 (n = 26) and U16 (n = 35). All female players were competing in a handball youth competition, with a mean of four training sessions per week plus one match during the weekend. To participate in the study, players must have at least two years of training experience, attend a minimum of three training sessions per week, and be free from injury for the last two weeks prior to data collection. All procedures implemented in this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Madeira (151/CEUMA/2024, 21 November 2024), and written informed consent was obtained from the participants and their respective legal guardians. A priori, the Mann–Whitney U test indicated a total sample size of 56 participants to achieve 80 % power to detect an interaction effect of 0.70 at the 0.05 significance level. Afterward, a priori correlation analysis showed a total sample size of 59 participants to achieve 75 % power at a 0.05 significance level.

2.2. Body Composition

Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer (SECA 213, Microgate, Hamburg, Germany). Body composition was assessed using hand-to-foot bioelectrical impedance analysis (InBody 770, InBody, Cerritos, CA, USA). On the platform, participants stood barefoot with their arms positioned at a 45-degree angle from their trunk and their feet on the designated spots. During the measurement, the participants were fasting and using only their underwear. The assessment was conducted in the early morning in laboratory settings. Body mass (kg), body fat (kg), body fat percentage (%), fat-free mass (kg), and body mass index (kg/m2) were retained for analysis.

2.3. Psychomotor Fitness

2.3.1. Linear Speed

Participants performed maximal sprints at distances of 5, 10, and 30 m to assess speed (s). Sprint time was recorded in seconds using Witty-Gate photocells (Microgate, Bolzano, Italy), and the best of two trials was retained for analysis. Participants recovered between sprints by walking back to the start line for 2 min between trials.

2.3.2. Agility

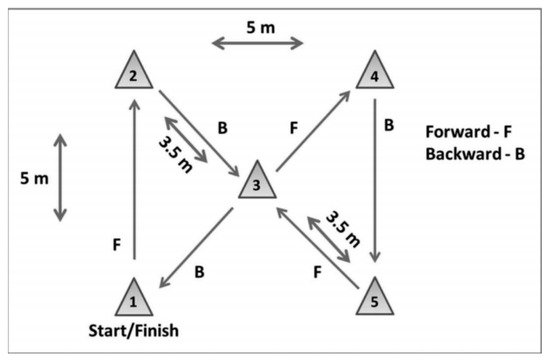

Agility was measured using a zig-zag test performed with and without a ball. The agility test incorporates handball-specific movements, including running forward and backward, as well as changing direction both with and without the ball (s) [25,26]. Figure 1 shows the arrangement of the markers in a rectangle (A–B–C–D) with 5 m between A–D and B–C, and 3.5 m between A–B and C–D, with another marker located at the center of the square (E). Players had to start the course on the left side of marker A, run with and without dribbling from A to B, around E, from C to D, around E, and finish at A. Players had to complete the course three times [25]. Each player’s time (in seconds) to run the course with and without a ball was recorded for analysis using Witty-Gate photocells (Microgate, Bolzano, Italy).

Figure 1.

Zig-Zag - change of direction ability test.

2.3.3. Upper Limb Speed and Coordination

The plate tapping test aims to evaluate the motor component associated with the speed and coordination of the upper limbs with a back-and-forth movement of the hands (s). Two circles and a rectangle were fixed to the table, with the rectangle positioned between the circles, forty centimeters apart. The athletes faced the table with their legs apart, their non-dominant hand resting on the rectangle, and their dominant hand resting on the circle on the opposite side. At the assessor’s signal, each participant moved their dominant hand as quickly as possible, reached the circle on the other side, and then returned to the circle of origin, thus completing one cycle. The test consisted of performing 25 complete cycles, i.e., 50 beats, in the shortest time possible. Each athlete performed the test twice, and the best result (i.e., the shortest time) was recorded.

2.4. Psychomotor Abilities

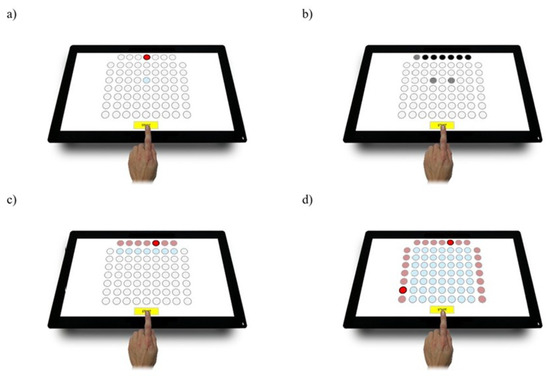

Psychomotor abilities were evaluated using the Test2Drive system (ALTA, Siemianowice Śląskie, Poland) [27,28]. Four tests were assessed to measure the indicators of psychomotor abilities [29]:

- Simple Reaction Time Test (SIRT)—reaction time (RT, ms), movement time (MT, ms), and the percentage of correct responses (%) assessed basic stimulus-response processing. The participant began the evaluation by placing a finger on the “START” box. Once a red signal appeared at the top of the screen presented at variable intervals, the task was to move the finger to the designated blue field as rapidly as possible.

- Choice Reaction Time Test (CHORT)—participants responded to multiple stimuli with corresponding responses. RT (ms), MT (ms), and accuracy (%) were recorded to evaluate decision-making speed and movement execution under choice conditions. One of three bar patterns (horizontal, vertical, or diagonal) was displayed at the top of the screen. Depending on the stimulus, the participant was required to move the finger from the “START” box to either the horizontal or vertical target box. When the diagonal pattern appeared, the correct response was to maintain the finger on the “START” box.

- Hand–Eye Coordination Test (HECOR)—This test measured sensorimotor processing speed with RT, MT, and correct response rate (%), which served as key indicators. After a red impulse appeared in the top row, the participant was required to move the finger from the “START” box to the blue field as quickly and accurately as possible, and then return the finger to the starting position.

- Spatial Attention Test (SPANT)—Assessed attentional visuospatial processing, with RT, MT, and accuracy (%) recorded. During each trial, one box in the row and one in the column changed color simultaneously, indicating a target location. The participant’s task was to identify and point to the intersection of the two highlighted boxes, and subsequently return the finger to the starting field.

The panels illustrating the (a) SIRT, (b) CHORT, (c) HECOR, and (d) SPANT tests can be seen in Figure 2 in their respective order.

Figure 2.

Reaction panel of the Test2Drive system; (a) SIRT—Simple Reaction Time Test, (b) CHORT—Choice Reaction Time Test, (c) HECOR—Hand–Eye Coordination Test, (d) SPANT—Spatial Anticipation Test.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to explore the data, including means and standard deviations. The data normality was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and non-normal distribution was identified for most of the variables under evaluation. Therefore, the Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare the performance of physical fitness and psychomotor abilities between groups (U14 and U16). Effect size was calculated and interpreted according to the following criteria: 0.1 = small effect, 0.3 = medium effect, and 0.5 = large effect [30]. Afterward, the Pearson product-moment correlation was respectively used to explore the relationship between physical fitness and psychomotor abilities performance among all participants. The strength of the correlation was interpreted following Cohen’s guidelines as small (0.1 < r < 0.3), moderate (0.3 < r < 0.5), and large (0.5 < r < 1.0). All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 29.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). GraphPad Prism, version 10 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA), was used for illustration. The significance level was set at .

3. Results

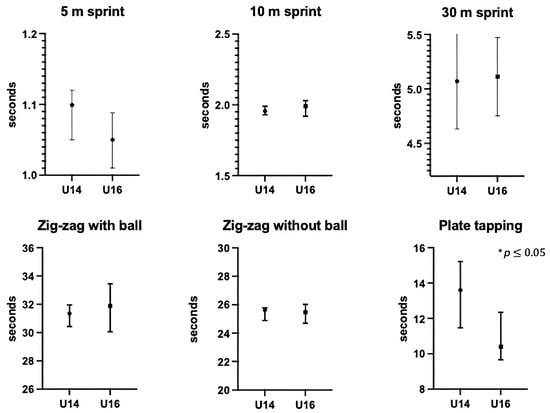

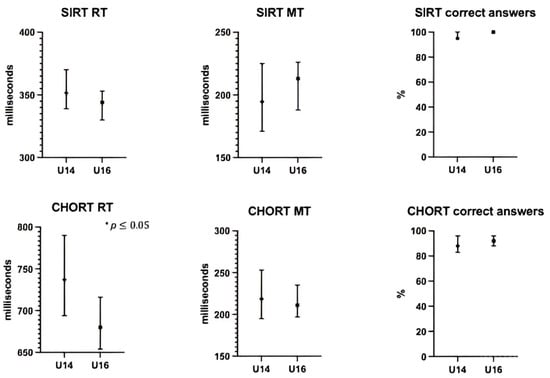

The present study aimed to compare physical fitness and psychomotor abilities between two adolescent age groups, U14 and U16, committed to regular sports training. The findings highlight age-related differences in psychomotor abilities performance, despite comparable physical characteristics and somatic profiles. Anthropometric data revealed no significant differences between the groups in terms of height, body mass, BMI, FFM, or BF % (Table 1), indicating a relatively homogeneous body composition among participants. Moreover, in physical performance tests, there was evidence of no significant differences in linear sprint performance (5 m, 10 m, 30 m) or agility tests (zigzag with and without the ball), indicating similar levels of speed and agility across both groups. However, U16 participants achieved better results than U14 young athletes in the tapping test, suggesting enhanced neuromuscular coordination and faster upper-limb motor execution. In contrast, psychomotor assessments showed more pronounced differences between the groups. In the SIRT, both groups performed similarly, with no significant differences in reaction time, movement time, or accuracy. However, in the Choice Reaction Test (CHORT), the U16 group demonstrated significantly faster reaction time. The Spatial Attention Test (SPANT) also favored the U16 group across all variables, suggesting superior visuospatial attention and sensorimotor integration. Interestingly, the Hand–Eye Coordination Test (HECOR) yielded better performance from the U14 group in terms of reaction time and accuracy, potentially reflecting faster but less strategic or less cognitively demanding responses.

Table 1.

Comparison of body composition, physical and cognitive performance between the U14 and U16 groups.

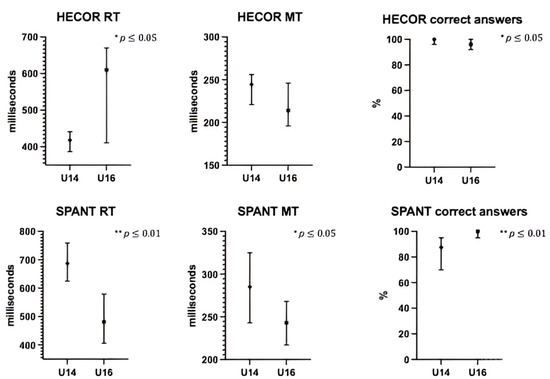

Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate the comparison between groups in terms of physical fitness and psychomotor abilities. No statistically significant differences were observed in body composition variables. When analyzing speed (sprints) and agility (zigzag), no significant effect was found between the U14 and U16 groups. U16 female handball players outperformed their U14 peers significantly in the plate-tapping test, indicating higher upper-body speed (p = 0.006, r = 0.35, medium effect size). Regarding psychomotor performance, substantial statistical differences were observed in CHORT RT (p = 0.014, r = 0.31, medium effect size), SPANT RT (p < 0.001, r = 0.45, medium effect size), SPANT MT (p = 0.047, r = 0.25, small effect size), and SPANT correct answers (p < 0.001, r = 0.43, medium effect size), with the U16 group outperforming the U14 group. In contrast, the U14 presented a significantly better performance in HECOR RT (p = 0.005, r = 0.36, medium effect size) and HECOR correct answers (p = 0.014, r = 0.31, medium effect size).

Figure 3.

Comparison of physical fitness performance between age groups.

Figure 4.

Comparison of psychomotor abilities SIRT, CHORT performance between age groups.

Figure 5.

Comparison of psychomotor abilities HECOR, SPANT performance between age groups.

The correlation analysis in the Table 2 among speed, agility, and psychomotor abilities tests revealed several meaningful relationships, highlighting the measures’ internal consistency and interconnected nature. The 5 m, 10 m, and 30 m sprint tests showed strong positive correlations (r = 0.67–0.75), confirming their coherence as reliable indicators of linear speed. Additionally, sprint performance correlated with zig-zag test results without the ball, and, to a lesser extent, with tapping time and selected psychomotor indicators such as CHORT reaction time and HECOR movement time. These findings suggest that general speed may influence both agility and cognitive-motor responsiveness. The research results related to the zig-zag test with and without a ball were moderately correlated (r = 0.51). Moreover, zig-zag performance with the ball showed a low but significant correlation with movement time in the SPANT test (r = 0.30), suggesting that visuomotor coordination plays a role in the execution of technical agility. The plate tapping test emerged as a powerful indicator of psychomotor speed, showing significant correlations with a range of variables, including SIRT movement time (r = 0.48), CHORT movement time (r = 0.57), HECOR reaction time (r = −0.48), HECOR movement time (r = 0.69), SPANT reaction time (r = 0.63), and SPANT movement time (r = 0.52). These results confirm tapping as a robust predictor of general neuromuscular speed and psychomotor efficiency. Further analysis of attention and reaction time tests revealed high correlations between movement time in the SIRT and CHORT tests (r = 0.82) and between movement time in the HECOR and SPANT tests (r = 0.64). Additionally, negative correlations between HECOR reaction time and SPANT reaction and movement time suggest that a shorter Hand–Eye Coordination Test is associated with improved spatial attention performance.

Table 2.

Significant correlation coefficients for physical fitness and psychomotor abilities performance.

4. Discussion

The study compared the psychomotor abilities and physical performance of U14 and U16 trained young female handball players, examining the relationship between these abilities. Regarding the hypotheses put forward, the findings partially supported the first hypothesis, as U16 players demonstrated superior performance in complex psychomotor tasks, including the CHORT and SPANT tests, although these differences were not consistent across all examined variables. The second hypothesis was supported, as U14 players achieved better outcomes in the simple hand–eye coordination task (HECOR). The third hypothesis was likewise supported, with several significant correlations observed between physical fitness components and psychomotor performance across the entire cohort. While both groups showed similar physical characteristics and performance in sprinting and agility, U16 players generally outperformed U14 players in psychomotor abilities tasks such as reaction time and spatial attention, indicating age-related cognitive and neuromuscular development. Interestingly, U14 athletes performed better in the Hand–Eye Coordination Test, suggesting faster, but possibly less complex, responses. In addition, correlation analyses showed strong relationships between speed, agility, and psychomotor metrics, highlighting the integrated physical and cognitive-motor functions of young athletes.

In the CHORT Test, the U16 group demonstrated significantly faster reaction time, indicating more efficient stimulus processing and decision-making. The SPANT also favored the U16 group across all variables, suggesting superior visuospatial attention and sensorimotor integration. These results align with previous research showing that reaction time tends to decrease with age and training experience [31]. This can be justified by neural maturation and the development of sport-specific tactical understanding. Younger players often exhibit longer reaction times due to less refined motor skills and cognitive processing abilities, which can impede performance during critical game moments [31]. Many researches across sports and cognitive tasks consistently shows that younger players demonstrate lower levels of perceptual-cognitive skills, strategic thinking, and decision-making complexity than older or more experienced peers [32,33]. De Waelle et al. [34] in youth volleyball, anticipation skills begin to improve around age 11, pattern recall around age 13, and optimal decision-making emerges closer to age 16, indicating a clear developmental progression in cognitive complexity and strategy use. Similarly, in soccer, older youth players generate better options, show improved inhibition and cognitive flexibility, and make more accurate, contextually appropriate decisions than younger players [35]. Furthermore, research by Sheppard et al. [36] demonstrated that the ability to make quick yet informed decisions is developed through experience and cognitive training, and is well-suited to the handball environment. The importance of these skills is supported by the findings of Jamel and Majeed [37], who described that focused training on psychomotor tasks, including decision-making under pressure, can enhance overall responsiveness and performance in young female players. This was confirmed by the results obtained in CHORT RT and SPANT RT.

Moreover interesting results were observed in the HECOR RT test, which evaluates Hand–Eye Coordination. The U14 group achieved better results in both reaction time and accuracy, potentially reflecting faster but less strategic or less cognitively demanding responses. These findings may indicate developmental differences in attention or cognitive control strategies between younger and older adolescents. The psychological skills pertinent to high-contact sports, such as handball, are crucial in shaping an athlete’s performance capabilities and coping strategies, further contributing to the understanding of psychomotor abilities in young athletes [38].

Therefore research supports that youth handball players, especially those at higher competition levels or with targeted training, achieve better results in complex psychomotor tests than non-athletes or lower-level peers. These findings highlight the importance of structured psychomotor and coordination training in youth handball development [5,6,39].

The interplay between physical fitness and psychomotor performance is critical in the context of trained young female handball players. Various components of physical fitness, including strength, speed, and agility, can contribute to improving psychomotor performance, such as reaction time, decision-making, and the execution of skills, across different age groups [40,41,42]. The plate tapping test emerged as a powerful indicator of psychomotor speed, showing significant correlations with key reaction and movement parameters.

Anthropometric data revealed no significant differences between the groups in terms of height, body mass, BMI, FFM, or BF %, indicating a relatively homogeneous body composition among participants. There were no significant differences in linear sprint performance (5 m, 10 m, 30 m) or agility tests (zigzag with and without the ball), indicating similar levels of speed and agility across both groups. However, U16 participants achieved better results than U14 young athletes in the tapping test. According to the literature, strength and speed training are crucial as they enhance the overall physical capability of players, facilitating powerful movements required during gameplay [43]. A study by Mijalković et al. [13] emphasized that physical condition and motor abilities are interrelated, although they found no significant correlation within their sample.

The observed correlations between physical and psychomotor performance support the integrated nature of these systems. Sprint performance correlated with zig-zag tests and selected psychomotor indicators such as CHORT reaction time and HECOR movement time. This suggests that general speed may influence both agility and cognitive-motor responsiveness. These findings align with the existing literature emphasizing the importance of integrating agility, strength, and speed training with the development of cognitive skills through game-specific scenarios [43]. Such integrative approaches may contribute to holistic player development.

Research consistently demonstrates a significant correlation between physical fitness and psychomotor abilities such as reaction time, coordination, and vigilance—in team sports athletes. Higher levels of physical fitness are associated with better motor skills, faster reaction times, and improved technical execution in sports like football, rugby, and volleyball [17,29,44,45,46].

This study presents limitations that should be recognized. First, this is a cross-sectional analysis, which might limit the generalization of the results. A longitudinal assessment would provide a more detailed analysis of the relationship between psychomotor abilities and physical fitness components. Second, the players’ maturity status was not considered, which could particularly affect physical performance among the U14 group.

5. Conclusions

The results of the study are of practical importance for coaches and specialists working with young female handball players: (1) In U14, it is advisable to increase the emphasis on training basic coordination, simple reactions, and exercises with low cognitive complexity. (2) In U16, more decision-making tasks, spatial attention exercises, and time-pressured tasks should be introduced. (3) The plate tapping test can be a quick and practical tool for monitoring fast upper limb movements. (4) Speed and agility did not differ between age groups; an individual training approach is recommended in these areas. (5) Combining cognitive elements with technique and tactics (e.g., small games, perception–decision exercises) can accelerate the development of psychomotor functions that are key to handball match situations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M., C.F., M.Ś. and É.R.G.; Methodology, F.M., C.F. and M.Ś.; Validation, K.P. and É.R.G.; Formal analysis, F.M. and C.F.; Investigation, F.M., M.Ś., K.P., É.R.G. and M.Ś.; Resources, K.P., É.R.G. and M.Ś.; Writing original draft preparation, F.M., C.F. and M.Ś.; Writing review and editing, M.Ś., K.P. and É.R.G.; Visualization, F.M. and É.R.G.; Project administration, K.P. and É.R.G.; Funding acquisition, É.R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

F.M. acknowledges support from the Foundation for Science and Technology under a doctoral scholarship 2023-2027 (2023.01187.BD). F.M., C.F., and E.R.G. acknowledge support from LARSyS—Portuguese national funding agency for science, research, and technology (FCT) pluriannual funding 2020–2023 (Reference: UIDB/50009/2020). This research was funded by the Portuguese Recovery and Resilience Program (PRR), IAPMEI/ANI/FCT under Agenda C645022399-00000057 (eGamesLab).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Madeira (151/CEUMA/2024, 21 November 2024), and followed the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki for Medical Research in Humans (2013) and the Oviedo Convention (1997).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from all players and their respective legal guardians to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants and their respective guardians for their participation in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rios, M.; Fernandes, R.J.; Cardoso, R.; Monteiro, A.S.; Cardoso, F.; Fernandes, A.; Silva, G.; Fonseca, P.; Vilas-Boas, J.P.; Silva, J.A. Physical Fitness Profile of High-Level Female Portuguese Handball Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaamouri, N.; Hammami, M.; Cherni, Y.; Oranchuk, D.J.; van den Tillaar, R.; Chelly, M.S. Rubber Band Training Improves Athletic Performance in Young Female Handball Players. J. Hum. Kinet. 2024, 92, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurišić, M.V.; Jakšić, D.; Trajković, N.; Rakonjac, D.; Peulić, J.; Obradović, J. Effects of small-sided games and high-intensity interval training on physical performance in young female handball players. Biol. Sport 2021, 38, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dyachenko, M.; Tyshchenko, V. Physical and Functional State of Female Handball Players in the Preparation Period of the Stage for Maximizing Individual Capabilities. Sports Games 2025, 1, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Spieszny, M.; Kamys, Z.; Kasicki, K.; Wąsacz, W.; Ambroży, T.; Jaszczur-Nowicki, J.; Rydzik, Ł. The impact of coordination training on psychomotor abilities in adolescent handball players: A randomized controlled trial. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przednowek, K.; Śliż, M.; Lenik, J.; Dziadek, B.; Cieszkowski, S.; Lenik, P.; Kopeć, D.; Wardak, K.; Przednowek, K.H. Psychomotor abilities of professional handball players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Fenta, B.G.; wase Mola, D. Effect of eight-week callisthenics exercise on selected physical fitness quality and skill performance in handball. J. SPORTIF J. Penelit. Pembelajaran 2023, 9, 550–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronijević, M.; Ohnjec, K.; Dopsaj, M. Differences in Contractile Characteristics Among Various Muscle Groups in Youth Elite Female Team Handball Players Compared to a Control Group. Sports 2025, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barahona-Fuentes, G.; Hinojosa-Torres, C.; Espoz-Lazo, S.; Zavala-Crichton, J.P.; Cortés-Roco, G.; Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R.; Alacid, F. Impact of Training Interventions on Physical Fitness in Children and Adolescent Handball Players: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntianu, V.A.; Abalașei, B.A.; Nichifor, F.; Dumitru, I.M. The correlation between psychological characteristics and psychomotor abilities of junior handball players. Children 2022, 9, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakšić, D.; Trbojević Jocić, J.; Maričić, S.; Miçooğullari, B.O.; Sekulić, D.; Foretić, N.; Bianco, A.; Drid, P. Mental skills in Serbian handball players: In relation to the position and gender of players. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 960201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalsik, L.; Aagaard, P.; Madsen, K. Locomotion characteristics and match-induced impairments in physical performance in male elite team handball players. Int. J. Sport. Med. 2013, 34, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijalković, S.; Antonijević, M.; Lilic, A.; Stanković, A.; Stanković, D. Body composition and motor abilities in 8-year-old children: A pilot study. J. Anthropol. Sport Phys. Educ. 2024, 8, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śliż, M.; França, C.; Martins, F.; Marszałek, P.; Gouveia, É.R.; Przednowek, K. Psychomotor abilities, body composition and training experience of elite and sub-elite handball players. Appl. Sci. 2024, 15, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasković, M. Influence of body composition on basic motor abilities in handball players. Facta Univ. Ser. Phys. Educ. Sport 2022, 20, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q. Body mass index and sport type as predictors of strength, power, and agility in adolescent athletes: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2025, 4, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Paśko, W.; Śliż, M.; Paszkowski, M.; Zieliński, J.; Polak, K.; Huzarski, M.; Przednowek, K. Characteristics of cognitive abilities among youths practicing football. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutios, S.; Fiorilli, G.; Buonsenso, A.; Daniilidis, P.; Centorbi, M.; Intrieri, M.; Di Cagno, A. The impact of age, gender and technical experience on three motor coordination skills in children practicing taekwondo. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beavan, A.; Spielmann, J.; Ehmann, P.; Mayer, J. The development of executive functions in high-level female soccer players. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2022, 129, 1036–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, B.S.; Duffy, E.Y.; Hennessey, J.A.; Tolani, S.; Patel, N.; Bohnen, M.S.; Hsu, J.J.; Danielian, A.; Shah, A.B.; Goolsby, M.; et al. Electrocardiographic Findings in Female Professional Basketball Athletes. JAMA Cardiol. 2024, 9, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Fernandez, J.; Granacher, U.; Martinez-Martin, I.; Garcia-Tormo, V.; Herrero-Molleda, A.; Barbado, D.; Garcia-Lopez, J. Physical fitness and throwing speed in U13 versus U15 male handball players. BMC Sport. Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 14, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, D.A.; He, W.; Fleeton, J.R.; Orr, R.; Sanders, R.H. Effects of Age and Sex on Aerobic Fitness, Sprint Performance, and Change of Direction Speed in High School Athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2023, 37, e325–e331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermassi, S.; Sellami, M.; Fieseler, G.; Bouhafs, E.G.; Hayes, L.D.; Schwesig, R. Differences in body fat, body mass index, and physical performance of specific field tests in 10-to-12-year-old school-aged team handball players. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 9022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rubia, A.; Lorenzo, A.; Bjørndal, C.T.; Kelly, A.L.; García-Aliaga, A.; Lorenzo-Calvo, J. The relative age effect on competition performance of Spanish international handball players: A longitudinal study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 673434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanković, M.; Katanić, B.; Govindasamy, K.; Badau, A.; Badau, D.; Masanovic, B.; Bojić, I. Seasonal Changes in Body Composition, Jump, Sprint, and Agility Performance Among Elite Female Handball Players. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, F.; Veiga, V.; Carita, A.; Petroski, E. Morphological and physical fitness characteristics of under-16 Portuguese male handball players with different levels of practice. J. Sport. Med. Phys. Fit. 2013, 53, 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Tarnowski, A. System Test2Drive w badaniach psychologicznych kierowców. Transp. Samoch. 2014, 2, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Tarnowski, A. The Test2Drive system in driver assessments: Relationships between theory, law and practice. Przegląd Psychol. 2021, 64, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliz, M.; Pasko, W.; Dziadek, B.; Ziajka, A.; Poludniak, N.; Marszalek, P.; Krawczyk, G.; Przednowek, K. Relationship between body composition and cognitive abilities among young female handball players. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2023, 23, 1650–1659. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; Volume 412. [Google Scholar]

- Živković, M.; Stojiljković, N.; Antić, V.; Pavlović, L.; Stanković, N.; Jorgić, B. The motor abilities of handball players of different biological maturation. Facta Univ. Ser. Phys. Educ. Sport 2019, 17, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisler, S.M.; Lobinger, B.H.; Musculus, L. A developmental perspective on decision making in young soccer players: The role of executive functions. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2023, 65, 102362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijgen, B.C.; Leemhuis, S.; Kok, N.M.; Verburgh, L.; Oosterlaan, J.; Elferink-Gemser, M.T.; Visscher, C. Cognitive functions in elite and sub-elite youth soccer players aged 13 to 17 years. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144580. [Google Scholar]

- De Waelle, S.; Warlop, G.; Lenoir, M.; Bennett, S.J.; Deconinck, F.J. The development of perceptual-cognitive skills in youth volleyball players. J. Sport. Sci. 2021, 39, 1911–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehmann, P.; Beavan, A.; Spielmann, J.; Mayer, J.; Altmann, S.; Ruf, L.; Rohrmann, S.; Irmer, J.P.; Englert, C. Perceptual-cognitive performance of youth soccer players in a 360-environment–Differences between age groups and performance levels. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 59, 102120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, J.; Young, W.B.; Doyle, T.; Sheppard, T.; Newton, R.U. An evaluation of a new test of reactive agility and its relationship to sprint speed and change of direction speed. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2006, 9, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamel, L.; Majeed, W. The Effect of Special Exercises Using the Visual Stimuli Device on the Speed of Motor Response, Visual Tracking, the Skills of Cutting and Dispersing the Ball, and Various Defensive Movements for Young Handball Players. Int. J. Disabil. Sport Health Sci. 2024, 7, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micoogullari, B.O.; Ekmekci, R. Adaptation Study of the Problem Solving Inventory on the Turkish Athlete Population. Sport Montenegrin 2018, 16, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratović, A.; Petković, J.; Bojanić, D.; Vasiljević, I. Comparative analysis of motor and specific motor abilities between handball players and nonathletes in the cadet age from Montenegro. Acta Kinesiol. 2015, 1, 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Stodden, D.F.; Goodway, J.D.; Langendorfer, S.J.; Roberton, M.A.; Rudisill, M.E.; Garcia, C.; Garcia, L.E. A developmental perspective on the role of motor skill competence in physical activity: An emergent relationship. Quest 2008, 60, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Cao, Z.; Ganderton, C.; Tirosh, O.; Adams, R.; Ei-Ansary, D.; Han, J. Ankle proprioception in table tennis players: Expertise and sport-specific dual task effects. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2023, 26, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.; Casanova, N.; Marconcin, P.; Willig, R.; Vidal-Conti, J.; Soares, D.; Flôres, F. Physical fitness as a predictor of reaction time in soccer-playing children. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbar, S.; Geok, S.K.; Bashir, M.; Mohd, N.N.J.B.; Luo, S.; He, S. Effects of Different Exercise Training on Physical Fitness and Technical Skills in Handball Players. A Systematic Review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2024, 38, e695–e705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozina, Z.; Cretu, M.; Safronov, D.; Gryn, I.; Shkrebtii, Y.; Bugayets, N.; Shepelenko, T.; Tanko, A. Dynamics of psychophysiological functions and indicators of physical and technical readiness in young football players aged 12–13 and 15–16 years during a 3-month training process. Physiother. Q. 2019, 27, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trecroci, A.; Duca, M.; Cavaggioni, L.; Rossi, A.; Scurati, R.; Longo, S.; Merati, G.; Alberti, G.; Formenti, D. Relationship between cognitive functions and sport-specific physical performance in youth volleyball players. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Singh, J. Relationship of psychomotor abilities in relation to selected sports skill in volleyball. Sci. J. Educ. 2016, 4, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).