Abstract

Background: This narrative review synthesizes evidence on AI for orthodontic malocclusion diagnosis across five imaging modalities and maps diagnostic metrics to validation tiers and regulatory readiness, with focused appraisal of Class III detection (2019–2025). Key algorithms, datasets, clinical validation, and ethical/regulatory considerations are synthesized. Methods: PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched for studies published January 2019–October 2025 using (“artificial intelligence”) AND (“malocclusion” OR “skeletal class”) AND “cephalometric.” Records were screened independently by two reviewers, with disagreements resolved by consensus. Eligible studies reported diagnostic performance (accuracy, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), sensitivity/specificity) or landmark-localization error for AI-based malocclusion diagnosis. Data on dataset size and validation design were extracted; no formal quality appraisal or risk-of-bias assessments were undertaken, consistent with a narrative review. Results: Deep learning models show high diagnostic accuracy: cephalogram classifiers reach 90–96% for skeletal Class I/II/III; intraoral photograph models achieve 89–93% for Angle molar relationships; automated landmarkers localize ~75% of points within 2 mm. On 9870 multicenter cephalograms, landmarking achieved 0.94 ± 0.74 mm with ≈89% skeletal-class accuracy when landmarks fed a classifier. Conclusion: AI can reduce cephalometric tracing time by ~70–80% and provide consistent skeletal classification. Regulator-aligned benchmarks (multicenter external tests, subgroup reporting, explainability) and pragmatic open-data priorities are outlined, positioning AI as a dependable co-pilot once these gaps are closed.

1. Introduction

This review synthesizes evidence across cephalograms, photographs, cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), digital models, and panoramic radiographs, linking diagnostic metrics to validation tiers and regulatory context, a perspective largely missing from prior orthodontic AI reviews. Orthodontic adoption of AI began in the mid-2010s with the first fully automated convolutional neural network (CNN) for cephalometric landmark detection [1]. Since 2017, mean radial error fell from 1.87 ± 2.04 mm (success detection rate (SDR) within 2 mm: 73% [2]) to 0.94 ± 0.74 mm on a multicenter model trained on 9870 cephalograms, which also delivered ≈89% skeletal-class accuracy [3]. Detector architecture still matters: on the same dataset, YOLOv3 attains an MRE of ≈ 1.5 mm, clearly outperforming SSD [4].

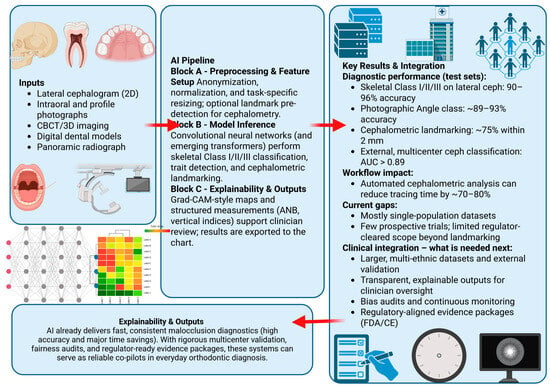

The diagnostic scope (Figure 1) has expanded in tandem. A hybrid random forest combining airway and cephalometric features distinguishes Classes I–III with mid-80% accuracy [5], and a profile-photograph CNN estimates ANB with mean absolute error (MAE) ≈ 1.5° [6]. Independent validations of landmark detectors [7] and a large multicenter oral-pathology CNN confirm cross-site generalizability [8].

Figure 1.

Overview of AI-enabled malocclusion diagnosis. Arrows indicate the information flow from imaging inputs (left) through the AI pipeline (center) to test-set diagnostic performance, workflow impact, and clinical integration requirements (right). Left panel: data inputs (lateral cephalogram, intraoral and profile photographs, CBCT/3D imaging, digital dental models, panoramic radiographs). Center panel: AI pipeline Block A, preprocessing and feature setup; Block B, CNN/transformer inference for skeletal Class I–III classification, trait detection, and cephalometric landmarking; Block C, explainability and structured outputs (Grad-CAM-style maps and measurements such as ANB and vertical indices, shown as an illustrative example rather than an endorsement of a specific method). Right panel: key diagnostic performance metrics, estimated workflow gains, current evidence gaps, and regulator-aligned requirements for clinical integration.

State-of-the-art machine learning techniques such as domain adaptation, cross-domain learning, fused domain-cycling generative adversarial models, multimodal feature-fusion approaches, and collaborative generative models shape the current and future landscape of medical AI. Orthodontic imaging has not yet adopted these methods, but they could improve multi-domain consistency, data harmonization, and generative augmentation to handle variation between devices, datasets, and domains. Better generalization across imaging environments remains one of the main challenges in malocclusion diagnosis.

Figure 1 presents a conceptual diagnostic pipeline rather than current routine practice. In reality, landmark detection, cephalometric measurement, and malocclusion classification remain separate tools and are not yet integrated into a fully automated system. The diagram is intended to illustrate a possible AI-enabled workflow, not to claim that end-to-end automation is already feasible or validated. Readers should interpret it as an explanatory framework, not as a depiction of existing clinical workflows.

Despite strong technical results, evidence for orthodontic workflow impact remains limited. Routine clinical adoption lags for four principal reasons: limited data diversity (small, demographically narrow cohorts); scarce prospective multicenter external validation with clinical-outcome endpoints; constrained transparency with subgroup/fairness reporting; and incomplete regulatory readiness and deployment practices (unclear decision thresholds and audit pathways) [9]. Explainability is inconsistently reported. Grad-CAM overlays are feasible and can be clinically informative [7], yet comparative work shows that different saliency methods highlight different anatomy [10]. Heatmaps help indicate general anatomical regions but offer limited diagnostic value in orthodontics, where decisions rely on specific cephalometric landmarks rather than qualitative visualizations. Clinicians need outputs such as computed ANB angles, vertical indices, or landmark-derived measurements that can be checked against accepted diagnostic rules. Structured, rule-based explanations at this level allow clinicians to verify how the AI reached its conclusion. Future orthodontic AI systems will require this type of clinically grounded interpretability to be integrated safely into routine practice. Orthodontic workflow evidence remains preliminary; analogous deployments in other specialties report measurable gains, radiology triage reduced CT reading time by 11 s [11], and a surgical-pathology system cut idle time by 18% [12], while this review focuses on orthodontic diagnosis and regulatory readiness. Regulatory clearances in dental and orthodontic AI currently cover tasks such as cephalometric analysis and orthodontic monitoring; for example, WEBCEPH™ is described as an AI-powered cephalometric and orthognathic platform with KFDA and FDA 510(k) approval, yet to our knowledge no system has secured FDA or CE approval for full, end-to-end malocclusion diagnosis [13].

This review fills a key gap by integrating accuracy, interpretability, efficiency, and fairness across lateral cephalograms, intraoral/extraoral photographs, CBCT scans, 3D digital dental models, and panoramic radiographs, and by mapping these claims to validation tiers and regulator-aligned multicenter validation frameworks. These developments matter directly for clinicians, as AI systems that match expert-level skeletal classification and reduce cephalometric tracing time by ~70–80% could act as reliable co-pilots once validation, fairness, and regulatory gaps are addressed.

2. Materials and Methods

We searched PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (January 2019–October 2025) using (“artificial intelligence”) AND (“malocclusion” OR “skeletal class”) AND “cephalometric.” This narrative review surveys AI-based malocclusion diagnosis across lateral cephalograms, intraoral and extraoral photographs, CBCT scans, digital dental models, and panoramic radiographs published between 2019 and 2025. Two reviewers independently screened titles/abstracts and full texts, resolving disagreements by consensus. We included original studies reporting diagnostic performance (accuracy, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity) or landmark-localization error for AI-based malocclusion diagnosis; reviews, editorials, case reports, and non-orthodontic applications were excluded. We extracted dataset size, validation design, and metrics; no formal quality appraisal or risk-of-bias assessment was undertaken, consistent with a narrative review. In this review, we focus on studies using multicenter datasets, predefined external-test cohorts and transparent reporting of subgroup or device-related performance, and consider these to provide higher-quality and more generalizable data. Conversely, findings derived from single-center, small-sample, or internally validated-only designs are interpreted as preliminary and susceptible to overfitting or limited real-world applicability. These quality distinctions are explicitly noted when summarizing performance ranges and comparing methods. Together, this provides clearer separation between robust evidence and results that should be viewed as exploratory. The final set of eligible studies forms the basis for the narrative synthesis presented in the following sections.

Though descriptions of studies are offered to clarify orientation, readers are referred to the original study for further information, consistent with the nature of narrative reviews. Secondly, after the screening of database candidates and manual searches, the studies not providing a solution to the malocclusion diagnosis, not related to an artificial intelligence-guided diagnostic output, or reporting on specific tasks such as isolated landmark detection, segmentation, or appliance prediction were discarded. Further exclusions were applied to those manuscripts that either did not present sufficient information regarding methodology and diagnostic performance measures or were unsuitable for a useful comparison. Thus, only research containing specific information about the ability to diagnose skeletal class, occlusal classification, or clinically relevant cephalometric diagnostic variables were included in the final set.

Current Capabilities

Current CNN and hybrid models achieve sub-millimeter landmark precision and high discriminative power for skeletal classification (Table 1). Evidence from a large oral-pathology dataset (over 20,000 images) suggests that such deep architectures can generalize across heterogeneous malocclusion phenotypes [8]. Together, these findings provide a strong technical basis for future prospective clinical validation studies.

Table 1.

Diagnostic performance of state-of-the-art AI systems for malocclusion diagnosis (test-set results). Abbreviations: AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; MAE, mean absolute error.

A large oral-pathology CNN (>20,000 images) was transferred to unseen classes, indicating scalability beyond orthodontics [8].

3. Discussion

The limitation of the search strategy is that it was focused on concepts directly related to malocclusion diagnosis and skeletal classification. This means that research specifically shrink-wrapped around the same task, i.e., support for decision-making on extractions, cephalometric landmarking, and orthodontic measurement prediction, among others, may not have been obtained if these words did not appear in either the title or the abstract. To expand the search, it would be necessary to look for the scope of the research beyond the diagnosis of malocclusion, which is not possible within the purpose of this study. Thus, the reader should consider this evidence as indicative of AI systems specifically designed for diagnostic classification, rather than encompassing all existing orthodontic AI applications, or all technologically possible ones.

Beyond pooling accuracies, the clinical meaning of “90–96%” becomes clearer when reported metrics are linked to study design (external versus internal testing), subgroup performance, and clinician-facing explainability. Contemporary AI models perform on par with expert orthodontists; on lateral cephalograms, deep CNNs typically achieve 90–96% accuracy [14]. A CNN trained on ~1500 images reached 96% accuracy (Cohen’s κ ≈ 0.91), outperforming automated cephalometry (κ ≈ 0.78) [14]. These headline results were obtained from single-country datasets with predominantly internal validation, so they should be regarded as optimistic upper bounds rather than as expected performance in heterogeneous real-world clinical populations. These models operate end-to-end, identifying malocclusion patterns directly from images without requiring manual landmark input. CNNs also generalize complex patterns. A multicenter South Korean study reported AUC > 0.89 and accuracy > 0.80 when simultaneously classifying anteroposterior skeletal class, vertical pattern, and bite type on external radiographs [15]. Performance is often highest for pronounced phenotypes. Class III cases (prognathism) yielded the best detection rates, with an external test AUC ~0.99 in one study [15], indicating that AI is very reliable at identifying severe malocclusions.

AI also performs well on photographic data. In one prospective trial, a CNN analyzing intraoral photographs (three views per patient) achieved 93% accuracy (F1 ≈ 0.90) in the Angle molar classification, matching expert orthodontist performance [16]. Notably, the AI was more precise than the human examiner for molar classes (precision 88.6% vs. 80.4%) [17], suggesting greater consistency in applying classification criteria. However, clinicians outperformed the AI on continuous measurements (e.g., overjet and overbite), with human errors ~1.3 mm vs. AI ~2.0 mm [16]. This indicates that 2D CNNs (without depth cues) struggle with sub-millimeter accuracy.

AI also detects specific malocclusion traits. Noëldeke et al. reported >98% accuracy for crossbite detection in intraoral photographs, with all CNNs (ResNet, MobileNet, etc.) achieving recall >90% and the best model (Xception) reaching 100% specificity [18]. These results show that subtle occlusal discrepancies can be learned from 2D images given adequate data. Machine learning models trained on panoramic radiographs have also diagnosed Class III malocclusions in children, indicating that panoramic imaging can support malocclusion-related prediction tasks despite the lack of large public malocclusion datasets. Together with AI systems that categorize crowding severity and support extraction decisions from intraoral photographs, these findings suggest that crossbite and crowding can both be modeled as trait-level malocclusion patterns in photographic data.

Cephalometric landmark detection has reached clinically acceptable accuracy. Modern detectors locate ~75–85% of landmarks within 2 mm of the true position [19]. An evaluation of a YOLOv3-based cephalometric model reported an average landmark error of ~1.8 mm and SDR within 2 mm: 75.5% [19]. Many errors approach the level of human intra-observer variability, supporting automated cephalometry. Indeed, recent AI models achieve cephalometric measurements (angles and distances) comparable to experienced orthodontists [19]. This implies that AI can effectively reproduce complete diagnostic work-ups (ANB angle, vertical indices, etc.) with minimal clinician input. The current landscape of AI-driven malocclusion diagnosis is further synthesized in Table 2, which summarizes state-of-the-art performance metrics, explainability approaches, workflow impacts, fairness considerations, and regulatory readiness, together with their key supporting references [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29].

Table 2.

Evidence grid: AI-driven malocclusion diagnosis.

Ethnic craniofacial differences make multi-ethnic datasets essential for safe orthodontic AI implementation [23,24,25,26,27]. A model trained on predominantly Caucasian norms may misclassify skeletal relationships in Asian or African populations, where features such as bimaxillary protrusion represent normal variation rather than pathology. This can lead to systematic overcalling of Class II or III patterns and embed incorrect diagnostic standards into automated systems [25,26]. Population-specific data and calibration are therefore necessary to avoid clinically significant errors.

3.1. Algorithms and Techniques

Deep CNNs remain the dominant algorithms due to their success in image recognition. Common architectures (ResNet, VGG, DenseNet, EfficientNet) have all been applied to malocclusion classification or feature detection [30]. ResNet-50, ResNet-18, MobileNet, Xception, and DenseNet were evaluated for crossbite detection, each achieving high AUC (>0.95) on cross-validation [18]. Model choice depends on data size and compute resources: lighter models like MobileNet can be competitive (F1 ~0.98) while offering faster inference [18]. Vision Transformers (ViTs) are emerging alternatives. A transformer model with masked pretraining on unlabeled cephalograms achieved ~90% accuracy on multi-attribute diagnosis (e.g., Class III with open bite) [31], showing strong generalization. These results suggest that transformers can capture global craniofacial patterns, though they demand large datasets and are early in dental AI research [32]. Although Vision Transformers have demonstrated strong performance in large-scale medical imaging, their practical value in orthodontics remains limited by the comparatively small size and homogeneity of available datasets [31,32]. ViTs typically require extensive pretraining or very large labeled cohorts to outperform convolutional models, conditions that are rarely met in dental AI research [32]. As a result, current ViT-based orthodontic systems should be viewed as exploratory rather than clinically mature, with their reported generalization reflecting potential rather than proven real-world robustness [31]. Until larger, diverse orthodontic datasets become widely available, CNNs are likely to remain the more reliable and data-efficient option.

Hybrid strategies are also reported: Ryu et al. (2023) combined CNN-based tooth landmark detection with classification networks to categorize crowding severity and predict extraction need [33]. Such multi-step pipelines (first measuring arch length discrepancy via landmarks, then decision-modeling extraction) add interpretability and structure to the AI’s reasoning. Interestingly, some classical machine learning methods hold their own. In a skeletal Class III classification study, a Gaussian process regression (GPR) model slightly outperformed deep networks (reportedly highest AUC ~0.98) in classifying Class III vs. normal, highlighting that, with the right features, non-deep algorithms can excel [34]. Similarly, Paddenberg-Schubert et al. found that no single algorithm was intrinsically superior for skeletal class prediction; simpler linear models achieved ~99% accuracy when fed a few key cephalometric features (e.g., SNB, jaw length ratio) [35]. Such near-perfect accuracies arise in tightly controlled, well-separated samples without external testing or formal risk-of-bias assessment and are likely to overestimate true diagnostic performance in routine practice.

3.2. Datasets and Open Initiatives

A critical concern in orthodontic AI is the size and diversity of training data. Many early studies used small, homogeneous samples of a few hundred single-center patients, which limits generalizability. More recent work uses larger, more varied datasets: Kim et al. (2022) trained a CNN on ~1334 cephalograms [14], and Yim et al. (2022) used >2000 cephalograms from 10 hospitals, improving robustness to differing image quality and patient demographics [15]. Photographic datasets have also expanded, with Bardideh et al. generating 7500 intraoral images from ~948 adults [16] and Ryu et al. training on ~1300 annotated occlusal photos per arch [33].

A recent review still identified only 16 unique open dental image datasets, with panoramic X-rays most common and no large public malocclusion datasets as of 2023 [36]. New comprehensive resources begin to fill this gap: the OMNI dataset provides thousands of intraoral, extraoral, and radiographic images for benchmarking malocclusion models, and Wang et al. (2024) released a 3D dataset of 1060 pre- and post-treatment dental models with segmentation labels across multiple malocclusions [37]. These open datasets support validation, fair algorithm comparison, and inclusion of diverse populations, as OMNI aggregates multi-ethnic patient images to mitigate bias, yet most current models still train and test on ethnically homogeneous cohorts (for example East Asian or Middle Eastern single-country studies), which raises concerns about performance in other ethnic and age groups.

AI systems for malocclusion diagnosis therefore still rely predominantly on lateral cephalograms and intraoral or extraoral photographs, with panoramic radiographs and 3D dental models only beginning to appear in the literature and remaining comparatively underexplored [36]. Such data are starting to become available through collaborations, e.g., an orthodontic grand challenge based on RSNA’s Machine Learning Challenge, as community challenges are public competitions on medical images organized by the RSNA. Thus, while the size and representativeness of datasets have improved over the last five years, more needs to be performed in terms of international data sharing and standardized benchmarks to create broadly generalizable and non-biased AI models.

A critical limitation in the current literature is the risk of data leakage and overfitting, which can substantially inflate reported accuracies, particularly when values approach the 96–99% range. In several published studies, train-test separation relies on image-level rather than patient-level splits, allowing different images from the same individual to appear in both sets. This undermines the validity of “90%+” performance claims, as models may learn patient-specific features rather than clinically meaningful patterns. In addition, some datasets mix sequential radiographs or photographs from the same treatment episode, further increasing the chance of inadvertent overlap. Without strict patient-level separation and transparent documentation of splitting protocols, results may overestimate real-world generalization. Readers should therefore interpret high accuracy values cautiously and prioritize studies that explicitly implement robust leakage-prevention strategies. Future orthodontic AI research will require standardized reporting of dataset partitioning to ensure reliability and reproducibility. The main architectural families used in AI-based malocclusion diagnosis and their comparative strengths and limitations are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparative characteristics of major AI architectures used in malocclusion diagnosis.

3.3. Clinical Validation and Utility

Most clinical evidence for orthodontic AI remains concentrated at early Fryback and Thornbury tiers (technical and diagnostic accuracy), with encouraging but limited advances toward real-world validation. Multicenter external testing has shown generalization across sites (AUC > 0.85) while revealing weaknesses on subtler distinctions, and a prospective head-to-head study found that AI matched expert accuracy and surpassed clinician consistency for occlusion classification. Concordance on extraction decisions is substantial (κ ≈ 0.8) with high AUCs (93–96%), though ground-truth variability persists in borderline cases. To date, one workflow study reached level 5 validation by reducing analysis time without compromising diagnostic accuracy; however, no large-scale randomized trials have evaluated patient outcomes, underscoring the need for prospective multicenter studies [15,17,33,38,39].

Validation tiers and endpoints are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Validation tiers and endpoints for AI in orthodontics.

Next steps (evidence gaps): Prospective multicenter trials—e.g., deploying AI for preliminary malocclusion triage in new patients and comparing treatment plans or outcomes with controls—would provide the strongest evidence; until such trials are completed, clinical-benefit claims remain inferential [15,38].

3.4. Regulatory and Ethical Considerations

As AI diagnostic tools near clinical use, regulators and clinicians emphasize explainability, validated performance across sites and subgroups, secure lifecycle management, and clear human oversight. Recent U.S. authorizations in dental AI (e.g., cephalometric analysis 510 (k), radiographic pathology detection, and a 2024 De Novo for orthodontic monitoring) show a viable pathway but do not constitute approval for end-to-end malocclusion diagnosis; submissions must evidence multicenter external validation with prespecified endpoints, subgroup reporting, safe-update mechanisms, cybersecurity, transparent labeling, and a clinician-in-the-loop model [13,33,38,39,40,41]. Regulatory and deployment requirements are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Regulatory-readiness checklist for AI in orthodontics.

Legal liability in AI-assisted diagnostics remains centered on the principle that such systems function as decision support rather than autonomous diagnostic agents [38,41]. Under both FDA SaMD and EU MDR frameworks, primary responsibility for diagnostic decisions continues to rest with the clinician, who must override system outputs when inconsistent with clinical findings [13]. Manufacturers carry liability when errors stem from flawed algorithms, insufficient validation, or unsafe software updates, whereas institutions may be accountable for improper deployment, lack of oversight, or failure to maintain post-market monitoring [41]. Documenting instances of AI–clinician disagreement and recording the reasoning behind final decisions is increasingly viewed as an essential safeguard. Emerging regulatory guidance also emphasizes that safe-update mechanisms and transparent labeling are prerequisites for assigning responsibility when model performance changes over time [38,41].

3.5. Future Directions

Future priorities and actions are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Future directions for AI in orthodontics.

Orthodontic AI should now shift from small, single-site studies to coordinated, multi-institution efforts that expand diverse datasets (including 3D/CBCT) with subgroup metadata for bias monitoring, while running prospective trials to document workflow and outcome effects in real clinics. Hybrid, rule-aware models can improve transparency for clinicians (e.g., explanations tied to cephalometric features), and fairness must be planned from the outset with subgroup reporting and privacy-preserving collaboration such as federated learning. Regulatory readiness will hinge on multicenter validation, safe-update processes, and institutional oversight, as applications broaden from diagnosis toward treatment planning where AI has already shown high performance in selected decisions (e.g., surgery vs. orthodontics in Class III) [33,36,38,42,43].

3.6. Conflicting AI Outputs and Clinical Decision Pathways

If algorithms are based on heterogeneous data, use different ground-truth labeling standards, or are validated differently, AI systems will make divergent recommendations [4,7,15]. This should not be read as a failure of systems, but as a yardstick that raises the need for further attention. In cases of outlying outputs, the initial action taken is to confirm the finding from a second diagnostic source, for instance, the AI cephalometric analysis will have to be cross confirmed with intraoral photos or digital dental models. Medical practitioners should also promote systems that can give understandable confidence or measures for uncertainty that also can help to see where the predictions are unreliable. The tool with the greatest regulatory-grade validation and established generalizability across populations should be utilized where more than one AI tool is deployed [33]. The discrepancy as well as the rationale that eventually led to a specific interpretation must be recorded by the clinician for the interpretation to be traced back to it, which is emerging as a requirement by the developing pressure to start regulating algorithmic diagnostic devices. When there is a significant difference between continued indices of discrepancy, there is a need for the clinician’s expertise and decision to discard suggestions from the system. This helps avoid deterministic thinking based on what we can extrapolate from algorithms and focuses again on the primacy of human choice. The goal is for AI systems to serve as diagnostic aides that support, but do not usurp, the authority of the clinician to diagnose.

In addition to the specific studies summarized above, several broader reviews and methodological frameworks place these findings in a wider orthodontic- and dental-AI context. Recent scoping and narrative reviews show that AI applications in orthodontics have expanded rapidly, but that study designs remain highly heterogeneous in terms of data types, annotation protocols, and outcome metrics, which complicates direct comparison and synthesis [44,45,46,47,48]. Parallel work on trustworthy AI in dentistry and medical imaging emphasizes that reproducibility, fairness, explainability, and lifecycle monitoring need to be evaluated alongside accuracy [49,50]. Methodological guidance such as the CONSORT-AI extension and analyses of data leakage in deep-learning classification highlights the importance of prespecified endpoints, transparent reporting, strict patient-level data separation, and external validation to avoid inflated performance estimates [51,52]. Related scoping work in adjacent orthodontic AI applications (e.g., clear aligner therapy) further reinforces these general reporting and validation priorities [53].

4. Conclusions

AI-based tools achieve high technical performance in malocclusion diagnosis, with 90–96% accuracy for skeletal Class I/II/III on cephalograms, SDR within 2 mm of ≈73–76% for landmarking and ~70–80% reductions in cephalometric tracing time. Despite this, clinical translation remains limited: evidence beyond retrospective or internal testing is sparse, multicenter external studies are few, and current regulatory authorizations cover cephalometric analysis and orthodontic monitoring rather than end-to-end malocclusion classification. Turning these systems into dependable co-pilots for orthodontists will require prospective multicenter trials with prespecified clinical endpoints, systematic subgroup and fairness reporting, clinician-facing explainability, and diverse, openly benchmarked datasets aligned with regulatory expectations for SaMD. Differences in imaging hardware, operator-dependent image acquisition, and demographic variation can increase errors when models are trained on narrow cohorts and may lead to failure modes such as systematic misclassification in marginalized groups or degraded performance when images do not resemble the training set [15,23,24,25,26,27]. Off-label use, lack of active monitoring for model drift, and limited clinical oversight further increase the risk of misuse; safe and fair application in daily clinics depends on recognizing and managing these weaknesses.

Author Contributions

K.C. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, original draft writing, and review and editing. M.M. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, original draft writing, review and editing, supervision, and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| ANB | A Point-Nasion-B Point (cephalometric angle) |

| CBCT | Cone-Beam Computed Tomography |

| CE | Conformité Européenne (European regulatory marking) |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| F1 | F1 Score (harmonic mean of precision and recall) |

| GPR | Gaussian Process Regression |

| Grad-CAM | Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MRE | Mean Radial Error |

| OMNI | Oral and Maxillofacial Natural Image dataset |

| SaMD | Software as a Medical Device |

| SDR | Success Detection Rate (percentage of landmarks within error threshold) |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once (object-detection neural-network family) |

References

- Arik, S.Ö.; Ibragimov, B.; Xing, L. Fully automated quantitative cephalometry using convolutional neural networks. J. Med. Imaging 2017, 4, 014501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.N.T.; Kang, J.; Oh, I.-S.; Kim, J.-G.; Yang, Y.-M.; Lee, D.-W. Effectiveness of human-artificial intelligence collaboration in cephalometric landmark detection. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Guo, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, Y.; Cheng, F.; Quan, S.; Feng, Q.; Li, J. Artificial intelligence system for automated landmark localization and analysis of cephalometry. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2023, 52, 20220081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Hwang, H.-W.; Moon, J.-H.; Yu, Y.; Kim, H.; Her, S.-B.; Srinivasan, G.; Aljanabi, M.N.A.; Donatelli, R.E.; Lee, S.-J. Automated identification of cephalometric landmarks: Part 1-Comparisons between the latest deep-learning methods YOLOV3 and SSD. Angle Orthod. 2019, 89, 903–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marya, A.; Inglam, S.; Chantarapanich, N.; Wanchat, S.; Rithvitou, H.; Naronglerdrit, P. Development and validation of predictive models for skeletal malocclusion classification using airway and cephalometric landmarks. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, S.; Mine, Y.; Urabe, S.; Yoshimi, Y.; Okazaki, S.; Sano, M.; Koizumi, Y.; Peng, T.-Y.; Kakimoto, N.; Murayama, T.; et al. Prediction of a cephalometric parameter and skeletal patterns from lateral profile photographs: A retrospective comparative analysis of regression convolutional neural networks. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johannes, T.; Akhilanand, C.; Joachim, K.; Shankeeth, V.; Anahita, H.; Saeed Reza, M.; Mohammad, B.; Hossein, M.-R. Evaluation of AI model for cephalometric landmark classification (TG Dental). J. Med. Syst. 2023, 47, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldivia-Siracusa, C.; de Souza, E.S.C.; da Silva, A.V.B.; Araújo, A.L.D.; Pedroso, C.M.; da Silva, T.A.; Sant’ANa, M.S.P.; Fonseca, F.P.; Pontes, H.A.R.; Quiles, M.G.; et al. Automated classification of oral potentially malignant disorders and oral squamous cell carcinoma using a convolutional neural network framework: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Reg. Health—Am. 2025, 47, 101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, A.C.; Wang, K.H.; Leung, T.I.; Facelli, J.C. Recommendations to promote fairness and inclusion in biomedical AI research and clinical use. J. Biomed. Inform. 2024, 157, 104693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, P.; Della Greca, A.; Amaro, I.; Tortora, A.; Staffa, M. A comparative analysis of XAI techniques for medical imaging: Challenges and opportunities. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Lisbon, Portugal, 3–6 December 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 6782–6788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkayastha, S.; Isaac, R.; Veldandi, A.; Saxena, R.; Singh, P.; Vaswani, P.; Krupinski, E.A.; Danish, J.A.; Gichoya, J.W. Measuring impact of radiologist-AI collaboration: Efficiency, accuracy, and clinical impact. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging, Athens, Greece, 27–30 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacko, R.; Davis, M.J.; Levy, J.; LeBoeuf, M. Integration of a deep learning basal cell carcinoma detection and tumor mapping algorithm into the Mohs micrographic surgery workflow and effects on clinical staffing: A simulated, retrospective study. JAAD Int. 2024, 15, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suara, S.; Jha, A.; Sinha, P.; Sekh, A.A. Is Grad-CAM explainable in medical images? In Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 2009, pp. 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, K.D.; Kim, D.H. Deep convolutional neural network-based skeletal classification of cephalometric images compared with automated-tracing software. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yim, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, I.; Park, J.-W.; Cho, J.-H.; Hong, M.; Kang, K.-H.; Kim, M.; Kim, S.-J.; Kim, Y.-J.; et al. Accuracy of onestep automated orthodontic diagnosis using a CNN and lateral cephalogram images from multihospital datasets. Korean J. Orthod. 2022, 52, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardideh, E.; Alizadeh, F.L.; Amiri, M.; Ghorbani, M. Designing an artificial intelligence system for dental occlusion classification using intraoral photographs: A comparative analysis between artificial intelligence-based and clinical diagnoses. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2024, 166, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, D.; Xu, L. Development and evaluation of a deep learning model for occlusion classification in intraoral photographs. PeerJ 2025, 13, e20140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noëldeke, B.; Vassis, S.; Sefidroodi, M.; Pauwels, R.; Stoustrup, P. Comparison of deep learning models to detect crossbites on 2D intraoral photographs. Head Face Med. 2024, 20, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, H.-W.; Moon, J.-H.; Kim, M.-G.; Donatelli, R.E.; Lee, S.-J. Evaluation of automated cephalometric analysis based on the latest deep learning method. Angle Orthod. 2021, 91, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Rivaz, H.; Xiao, Y. Is visual explanation with Grad-CAM more reliable for deeper neural networks? A case study with automatic pneumothorax diagnosis. In Machine Learning in Medical Imaging; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 14349, pp. 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellano, K.N.; Strümke, I.; Groos, D.; Adde, L.; Alexander Ihlen, E.F. Evaluating explainable AI methods in deep learning models for early detection of cerebral palsy. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 10126–10138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.A.; Eckert, C.; Allen, C.; Kumar, V.; Hu, J.; Teredesai, A. Fairness in healthcare AI. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 9th International Conference on Healthcare Informatics (ICHI), Victoria, BC, Canada, 9–12 August 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 554–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi, N.; Morstatter, F.; Saxena, N.; Lerman, K.; Galstyan, A. A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermeyer, Z.; Powers, B.; Vogeli, C.; Mullainathan, S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science 2019, 366, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Shi, Y.; Hu, J.; Jiang, W. Muffin: A framework toward multi-dimension AI fairness by uniting off-the-shelf models. In Proceedings of the Design Automation Conference (DAC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 9–13 July 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, D.; Kakinuma, T.; Fujita, S.; Kamagata, K.; Fushimi, Y.; Ito, R.; Matsui, Y.; Nozaki, T.; Nakaura, T.; Fujima, N.; et al. Fairness of artificial intelligence in healthcare: Review and recommendations. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2024, 42, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, E. Fairness and bias in artificial intelligence: A brief survey of sources, impacts, and mitigation strategies. Sci. 2024, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhong, Z.; Yang, X. Mitigating racial bias in chest X-ray disease diagnosis via disentanglement learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Athens, Greece, 27–30 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-S.; Ryu, J.-J.; Jang, H.S.; Lee, D.-Y.; Jung, S.-K. Deep convolutional neural networks based analysis of cephalometric radiographs for differential diagnosis of orthognathic surgery indications. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Bai, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Liang, S.; Xie, X. Automated orthodontic diagnosis via self-supervised learning and multi-attribute classification using lateral cephalograms. Biomed. Eng. OnLine 2025, 24, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, P.; Xie, Y.; Han, J.; Zeng, L.; Ning, N.; Zheng, Q.; Li, H.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z. Application of transformers in stomatological imaging: A review. Digit. Med. 2024, 10, e24-00001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.; Kim, Y.H.; Jeong, H.; Ahn, H.W. Evaluation of artificial intelligence model for crowding categorization and extraction diagnosis using intraoral photographs. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Chen, X.; Huang, J.; Mo, S.; Gu, M.; Kang, N.; Song, S.; Zhang, X.; Liang, B.; Tang, M. Machine Learning Algorithms for the Diagnosis of Class III Malocclusions in Children. Children 2024, 11, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paddenberg-Schubert, E.; Midlej, K.; Krohn, S.; Schröder, A.; Awadi, O.; Masarwa, S.; Lone, I.M.; Zohud, O.; Kirschneck, C.; Watted, N.; et al. Machine learning models for improving the diagnosing efficiency of skeletal Class I and III in German orthodontic patients. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribe, S.E.; Issa, J.; Sohrabniya, F.; Denny, A.; Schwendicke, F. Publicly available dental image datasets for artificial intelligence. J. Dent. Res. 2024, 103, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lei, C.; Liang, Y.; Sun, J.; Xie, X.; Wang, Y.; Zuo, F.; Bai, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.-J. A 3D dental model dataset with pre/post-orthodontic treatment for automatic tooth alignment. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, A.; Nooruddin, A.; Umer, F. Concerns regarding deployment of AI-based applications in dentistry: A review. BDJ Open 2025, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Device Software Functions: Lifecycle Management and Marketing Submission Recommendations (Draft Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff). U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 2023. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/artificial-intelligence-enabled-device-software-functions-lifecycle-management-and-marketing (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Stăncioiu, A.-A.; Motofelea, A.C.; Hușanu, A.A.; Vasica, L.; Popa, A.; Nagib, R.; Szuhanek, C. Innovative Aesthetic and Functional Orthodontic Planning with Hard and Soft Tissue Analyses. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, V.; Adewale, B.A.; Huang, C.J.; Nta, M.T.; Ademiju, P.O.; Pathmarajah, P.; Hang, M.K.; Adesanya, O.; Abdullateef, R.O.; Babatunde, A.O.; et al. A scoping review of reporting gaps in FDA-approved AI medical devices. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süer Tümen, D.; Nergiz, M. Federated learning-based CNN models for orthodontic skeletal classification and diagnosis. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taraji, S.; Atici, S.F.; Viana, G.; Kusnoto, B.; Allareddy, V.S.; Miloro, M.; Elnagar, M.H. Novel machine learning algorithms for prediction of treatment decisions in adult patients with Class III malocclusion. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 81, 1391–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monill-González, A.; Rovira-Calatayud, L.; d’Oliveira, N.G.; Ustrell-Torrent, J.M. Artificial intelligence in orthodontics: Where are we now? A scoping review. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2021, 24, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichu, Y.; Gaikwad, R.; Valiathan, A.; Gandhi, S. Applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning in orthodontics: A scoping review. Prog. Orthod. 2021, 22, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Shan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, G. Application of artificial intelligence in orthodontics: Current state and future perspectives. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazimierczak, N.; Kazimierczak, W.; Serafin, Z.; Nowicki, P.; Nożewski, J.; Janiszewska-Olszowska, J. AI in orthodontics: Revolutionizing diagnostics and treatment planning—A comprehensive review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracea, R.S.; Veltri, M.; Grippaudo, C.; Farronato, G. Artificial intelligence for orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning: A scoping review. J. Dent. 2024, 152, 105442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducret, M.; Schwendicke, F.; Meyer, M.; Ortalli, M. Trustworthy artificial intelligence in dentistry. J. Dent. Res. 2024, 103, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L.; Pawlitzki, M.; Renard, B.Y.; Meuth, S.G.; Masanneck, L. The three-year evolution of Germany’s Digital Therapeutics reimbursement program and its path forward. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Rivera, S.C.; Moher, D.; Calvert, M.J.; Denniston, A.K.; Ashrafian, H.; Beam, A.L.; Chan, A.-W.; Collins, G.S.; Darzi, A.; et al. Reporting guidelines for clinical trial reports for interventions involving artificial intelligence: The CONSORT-AI extension. BMJ 2020, 370, m3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampu, I.E.; Eklund, A.; Haj-Hosseini, N. Inflation of test accuracy due to data leakage in deep learning classification. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, D.C.; Paredes-Gallardo, V.; Ortiz-Ruiz, A.J.; Ausina-Molina, N. Artificial intelligence applied to clear aligner therapy: A scoping review. J. Dent. 2025, 154, 105564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).