Abstract

This paper presents a comprehensive and hybrid control framework for the real-time regulation of drillstring systems that are subject to complex nonlinear dynamics, including torsional stick–slip oscillations, coupled axial vibrations, and intricate bit–rock interactions. The model also accounts for parametric uncertainties and external disturbances typically encountered during rotary drilling operations. A robust sliding mode controller (SMC) is designed for inner-loop regulation to ensure accurate state tracking and strong disturbance rejection. This is complemented by an outer-loop model predictive control (MPC) scheme, which optimizes control trajectories over a finite horizon while balancing performance objectives such as rate of penetration (ROP) and torque smoothness, and respecting actuator and operational constraints. To address the challenges of partial observability and noise-corrupted measurements, an Ensemble Kalman Filter (EnKF) is incorporated to provide real-time estimation of both internal states and external disturbances. Simulation studies conducted under realistic operating scenarios show that the hybrid MPC–SMC framework substantially enhances drilling performance. The controller effectively suppresses stick–slip oscillations, provides smoother and more stable bit-speed behavior, and improves the consistency of ROP compared with both open-loop operation and SMC alone. The integrated architecture maintains robust performance despite uncertainties in model parameters and downhole disturbances, demonstrating strong potential for deployment in intelligent and automated drilling systems operating under dynamic and uncertain conditions.

1. Introduction

Drilling systems in oil and gas exploration are becoming increasingly complex and automated. One of the fundamental challenges in such systems is the suppression and control of drill string vibrations, which can negatively impact the rate of penetration (ROP), tool longevity, wellbore quality, and overall operational safety. These vibrations arise due to the long, flexible nature of the drill string and the complex, often nonlinear interaction between the drill bit and rock formation. Understanding and controlling such dynamic behavior is crucial for modern intelligent drilling systems.

1.1. Drill String Models and Existing Vibration Control Methods

The drill string is a slender mechanical structure that operates in highly uncertain and dynamic downhole environments. While transmitting torque and weight to the bit, it is subject to severe vibrational modes, typically categorized into axial (longitudinal), torsional, and lateral vibrations. Among these, torsional stick–slip and axial bit bounce are the most destructive. These phenomena arise due to the highly nonlinear interaction between the bit and the rock, especially under intermittent contact or heterogeneous formation layers.

Many studies [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14] have attempted to characterize these vibrations using various models. Early studies on bit–rock interaction established the mechanical foundations needed to describe drilling dynamics. Classical models such as those by [1] introduced phenomenological and experimentally validated cutting laws that remain central to modern TOB and ROP formulations. Subsequent works expanded the understanding of drillstring dynamics by incorporating friction uncertainty, nonlinear bit–rock coupling, and multi-mode interactions, including stick–slip, bit bounce, and coupled axial–torsional vibrations. Representative examples include stochastic friction models and nonlinear drag-bit vibration analyses by [2,3], as well as coupled axial–torsional stability and vibration modeling by [4,5,6,7]. A number of works have further advanced the understanding of coupled drillstring dynamics by examining nonlinear stability mechanisms and multi-mode vibration interactions. For example, [8] provided field-supported characterization of torsional behavior during bit-off-bottom conditions. In addition, [9] introduced a nonsmooth axial–torsional–lateral vibration model capable of capturing complex mode interactions relevant to real drilling environments. More recent studies have extended these frameworks to include fluid–structure interactions, lateral/whirl dynamics, and wellbore stability effects [13,14], providing high-fidelity models suitable for control development. In addition, early works [15,16] employed continuous beam models and simplified lumped-mass representations, capturing basic wave propagation and resonance behavior. Modern nonlinear and stochastic modeling approaches further deepen this foundation. [17] introduced stochastic nonlinear formulations for horizontal drillstrings, [18] presented dynamic friction-based torsional oscillation models, and [19] proposed component-based modeling for modular simulation. Recent contributions, such as those by [20], highlight data-driven model-selection strategies, whereas [21] demonstrated the influence of hydraulic oscillators on drag-reduction efficiency, illustrating how structural vibration-mitigation devices complement active control strategies.

Various control strategies have been proposed over the years to address the challenge of suppressing torsional and axial vibrations in drillstring systems. These strategies range from classical PID controllers to advanced sliding mode and predictive control approaches. In [22] a -synthesis controller is used to improve robustness against time delay and model uncertainties, though performance degraded for higher-DOF (degree of freedom) models due to its complexity. In [23], the authors applied a linear–quadratic–Gaussian control framework with Kalman estimation to control stick–slip, yielding high estimation accuracy but requiring statistical knowledge of system noise.

PID controllers are widely used in industry due to their simplicity and ease of implementation. In [24], the authors introduced a PD controller capable of suppressing stick–slip and tuning speed, but its performance was highly dependent on specific operating conditions. In [25], a PI control is combined with Luenberger and Kalman filters for active damping with auto-tuning, showing good robustness to weight on bit (WOB) variation but vulnerability to modeling errors at low bit inertia. Field validation was provided by [26] using PI control on a 35-DOF system, although settling time remained high. A PID-based stick–slip mitigation strategy was tested by [27], revealing strong performance under delay and uncertainty but lacking validation for WOB robustness. Moreover, both experimental studies [28] and field-scale implementations [29] have demonstrated the application of PID controllers. However, classical PID controllers often struggle under model uncertainties and time delays. To improve their robustness and tuning flexibility, several variations have been proposed. Fuzzy PID control [30] and fractional-order PID control [31] have demonstrated improved performance under variable operating conditions.

SMC techniques have shown strong robustness to model uncertainties, external disturbances, and parameter variations, making them attractive for vibration suppression. For instance, the authors successfully applied SMC to suppress stick–slip vibrations, though issues such as chattering and overshoot were noted, see [32,33]. The authors [34] proposed an enhanced SMC approach combined with an Extended Kalman Filter to estimate all 12 states of a nonlinear coupled drillstring model, achieving superior performance over traditional SMC and pole-placement designs. Furthermore, the authors [35] introduced a predictor-based SMC capable of mitigating torsional vibrations with input delay and external disturbances, showing clear robustness to parameter changes like weight-on-bit variation. A recent contribution by [36] developed an adaptive sliding mode controller with real-time auto-tuning gains, validated via hardware-in-the-loop experiments, confirming its superior vibration suppression compared to conventional techniques.

Recent work has focused on predictive and optimal control to handle complex nonlinear dynamics and constraints. A discrete-time MPC with friction compensation and input constraints was demonstrated in [37], showing excellent performance in stabilizing torsional oscillations. In [38], the authors developed a nonlinear MPC (NMPC) that uses balanced truncation and an advanced-step strategy for real-time execution. Their method suppresses stick–slip effectively and eliminates reliance on high-frequency torque measurements, outperforming the commercial ZTorque controller under various conditions. In terms of output-feedback strategies, in [39], an optimal static output feedback controller is introduced, achieving linear quadratic regulator-level performance with fewer sensors.

In addition to surface-based control strategies, a considerable body of research has focused on downhole vibration-mitigation devices and structural damping mechanisms integrated into the bottom-hole assembly. Smart downhole vibration controllers have been proposed to monitor and regulate shock loads in the lower part of the drillstring, providing localized suppression of axial and torsional oscillations [40,41]. Shell-type elastic shock absorbers have been investigated for their adaptive stiffness and damping behavior under varying external load amplitudes, demonstrating the ability to attenuate high-frequency axial shocks and improve bit–rock stability [42]. Furthermore, analytical models of structural damping in friction-based energy-dissipation modules, often implemented as spring–friction systems within shock-absorber shells, have been shown to reduce vibration transmission along the BHA and enhance drilling efficiency [43]. These developments highlight the complementary nature of downhole mechanical mitigation tools and active control strategies such as the hybrid MPC–SMC architecture proposed in this paper.

1.2. Proposed Method

The core of vibration suppression lies in accurate modeling of the drill string system. Our work builds on a discrete lumped-mass formulation that captures the essential characteristics of axial and torsional dynamics, along with the boundary interaction at the bit–rock interface. The model was originally presented by [44]. The axial domain includes gravitational effects, spring-damper coupling between segments, and penetration mechanics governed by a rate-of-penetration model. Torsion is treated similarly, with segmental inertia, torsional stiffness, and a friction-dependent torque-on-bit (TOB) model. An important feature of this model is the use of a nonlinear kinematic coupling at the bit–rock interface, where the axial penetration is defined as a function of the bit’s rotational position. This formulation enables the simulation of irregular rock surfaces, asymmetric cutting profiles, and stochastic formations. Contact status at the bit is managed via a switching system that differentiates between contact and lift-off states based on the WOB and the displacement threshold defined by the profile function. This coupled, nonlinear system provides a more realistic basis for developing estimators and controllers than traditional decoupled or linearized models.

The objective of vibration control is to suppress undesirable oscillations while maximizing drilling efficiency and adhering to safety limits. To this end, we propose a hierarchical control architecture composed of three main components:

- Ensemble Kalman Filter: for estimating unmeasured states, such as internal friction variables, drill bit velocities, and system parameters, based on partial and noisy sensor data;

- Model Predictive Control: for generating optimal reference trajectories that obey physical and operational constraints, such as actuator torque limits, axial displacement ranges, and speed profiles;

- Sliding Mode Control: for robust low-level tracking of the MPC trajectories with high disturbance rejection and finite-time convergence, particularly suitable for systems with uncertainties and nonlinearities.

The SMC operates at a high frequency and ensures accurate tracking under unknown disturbances and parameter mismatches. Meanwhile, MPC runs on a slower cycle and handles the constraint satisfaction and trajectory shaping based on the EnKF-provided state estimates.

The main contributions of this study are outlined below, emphasizing both theoretical development and practical relevance in the domain of intelligent drilling control systems:

- A comprehensive coupled axial–torsional dynamic model of the drillstring is considered, incorporating stochastic bit–rock interaction and switching behavior between contact and lift-off states. This model captures critical nonlinearities and transient effects observed in real drilling operations.

- A rate-of-penetration (ROP) model is integrated together with a nonlinear friction-based torque-on-bit formulation. These subsystems jointly represent stick–slip oscillations and bit bounce phenomena, enabling realistic reproduction of downhole vibrations.

- A hybrid control architecture is proposed, combining MPC, SMC, and EnKF. The EnKF provides real-time estimation of hidden states and external disturbances; MPC generates constraint-satisfying reference trajectories; and SMC robustly tracks these trajectories under uncertainty and model mismatch.

- A complete simulation framework is constructed, enabling systematic validation of the proposed control strategy. The framework accounts for actuator saturation, sensor noise, and modeling uncertainty, reflecting realistic field constraints.

- Simulation case studies are conducted to demonstrate the robustness, adaptability, and vibration mitigation capabilities of the controller under dynamically varying operating conditions.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is among the first works to present a fully integrated approach to realistic modeling, state estimation, and hybrid control for suppressing drillstring vibrations. The proposed system is particularly suited for applications in real-time drilling automation, digital twin platforms, and intelligent rig control design.

2. Drillstring System Modeling

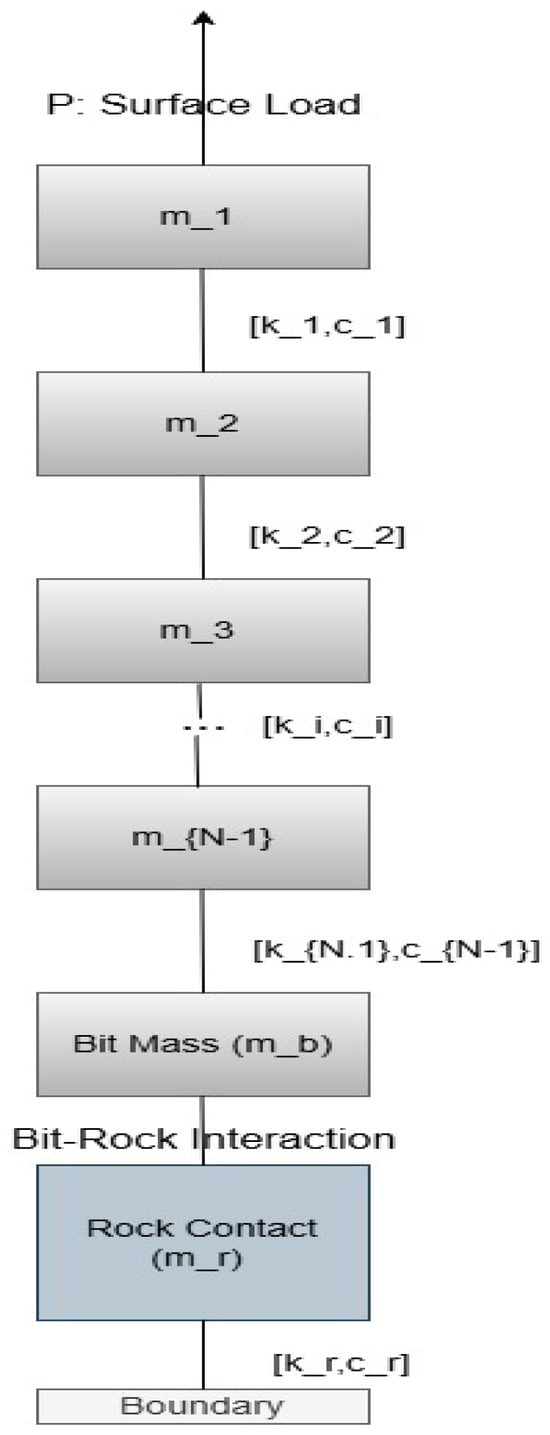

Our study selects a mathematical model of the coupled axial–torsional dynamics of the drill string presented by [44,45] in the MPC–SMC control framework. The model is formulated using lumped mass principles and includes nonlinearities due to bit–rinteraction on, and kinematic coupling. Figure 1 shows the drillstring schematic. The model details and the parameter notations are provided below.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the drill string with concentrated masses.

2.1. Axial Vibration Dynamics

The axial dynamics of the drill string are modeled as a series of N lumped masses connected via linear spring-damper elements. The axial position of the i-th mass is denoted , and its velocity . The axial dynamics capture the wave propagation, damping, and bit–rock contact force dynamics. For top mass :

where P is the applied surface load and g is the gravitational acceleration; is mass of the i-th node (or element) in the axial direction, is axial stiffness between node i and node , and is Damping coefficient between node i and node . For interior masses ,

The equation at the N-th mass (the drill bit) is

The contact force is the instantaneous weight on the bit and represents the axial interaction force at the bit–rock interface, and is the bit mass. At the bottom boundary, the rock formation is modeled as a lumped mass connected to the drill bit through a nonlinear contact law. The interaction includes both elastic and damping components, governed by stiffness and damping coefficient , respectively. The relative motion between the rock interface position and the boundary contact displacement governs the contact force. This yields thefollowing dynamic equation:

The terms and simulate the rock’s resistance to penetration and its viscoelastic deformation under dynamic loading. Physically, this model captures how the rock reacts to axial impacts from the bit, allowing simulation of realistic phenomena like bit bounce and soft/hard rock transition. The rock mass can be tuned to reflect different formation types. For very stiff formations, and may be large, simulating an almost rigid boundary. For soft formations or fractured zones, may be reduced, allowing greater compliance and oscillation at the bit–rock boundary. Additionally, the penetration boundary is itself time-varying and determined by a function of WOB and bit RPM, introducing kinematic coupling between the axial and torsional subsystems. In this framework, it is formulated as a nonlinear function [44]:

where is the angular velocity of the drill bit; is the cutting efficiency coefficient capturing formation type and bit sharpness, and is the background rate. This model reflects the physical principle that deeper and faster cutting occurs when both axial load and rotational speed are high. Alternative ROP models can also be substituted depending on the specific application or available data. The integral of gives the total penetration depth over time:

This displacement is dynamic and time-varying, forming a boundary condition in the axial dynamics. It governs when contact is established or broken at the bit–rock interface, playing a central role in status switching logic.

2.2. Torsional Vibration Dynamics

Similarly, the torsional model is defined over N rotational masses, each representing a segment of the drillstring, characterized by rotational displacements , angular velocities , and rotational inertias . The connecting shaft elements are modeled as torsional springs and dampers with constants and , respectively. When the drill bit is rotating relative to the rock formation (i.e., in a “slip” state), the torsional dynamics are governed by the following equation:

where

- is the inertia matrix;

- is the state vector of angular positions;

- and are the damping and stiffness matrices;

- is the external torque vector;

- is the torque applied at the surface by the top drive;

- is the torque exerted by the rock formation on the drill bit;

The torque-on-bit, , depends on the bit’s angular velocity and the axial weight-on-bit force :

Here, is the effective bit radius, and is the friction coefficient between the bit and the rock. The negative sign ensures that the formation resists bit rotation. The dynamic friction coefficient switches between two regimes depending on the bit’s angular velocity:

where is the dynamic friction coefficient during continuous rotation, is the static friction coefficient when the bit is nearly stationary, and is the threshold angular velocity defining the transition between stick and slip. This piecewise function enables the model to capture stick–slip behavior, a common cause of torsional oscillation in drilling.

2.3. Compact Matrix Form

The system can be expressed in matrix form as a set of second-order differential equations governing the axial and torsional dynamics:

Here, is the vector of axial displacements, and is the vector of torsional angular displacements. Matrices , and can be easily derived from the above model equations, see the details in [44]. is external force vector, which includes gravity, weight-on-bit , and bit–rock coupling force contributions.

2.4. Discussions

The accuracy of a discretized drillstring model depends critically on several parameter groups, including geometric properties, material characteristics, configuration data, and operational conditions. Variations in drillpipe and BHA geometry, cross-sectional stiffness, damping distributions, friction coefficients, and bit–rock interaction parameters can significantly influence the predicted dynamic response. Such changes affect the severity and frequency of nonlinear phenomena such as stick–slip, bit bounce, and axial shock propagation. These dependencies highlight the importance of performing careful sensitivity and uncertainty analyses when applying high-fidelity drillstring models to control design or operational planning.

A detailed investigation of parameter sensitivity, including the effects of discretization level, was conducted in our earlier work. These studies showed that the model response can vary markedly when geometric, material, or operational parameters are perturbed, and that sufficiently fine discretization is required to capture high-frequency axial–torsional interactions. Although such analyses are essential for comprehensive model validation, the present paper focuses primarily on the development of the hybrid MPC–SMC control framework. As future work, further attention will be devoted to model interpretation, validation, and systematic analysis to evaluate performance under varying conditions, including robustness, consistency, stability, computational complexity, and physical interpretability, in addition to accuracy.

3. Hybrid Control Design

In this section, we detail the design, structure, and integration of a dual-layer control strategy that combines an SMC for fast and robust inner-loop stabilization with an MPC as the outer-loop trajectory planner. This hybrid control architecture aims to mitigate nonlinear drillstring vibrations, manage hardware constraints, and anticipate system dynamics across a prediction horizon.

3.1. Design Motivation

SMC is known for its robustness against model uncertainties and external disturbances, making it an ideal candidate for real-time control in harsh environments such as downhole drilling. However, SMC does not inherently incorporate future state predictions or input/output constraints, which can limit its performance in constrained scenarios such as actuator saturation or delay compensation. MPC, in contrast, uses a dynamic system model to optimize a control trajectory over a finite horizon, subject to constraints on state and control inputs. By integrating MPC into the outer loop, we gain the ability to shape the SMC’s target trajectory in a constraint-aware and disturbance-predictive manner.

3.2. Notational Consistency for Control Design

To ensure consistency with the MPC–SMC control framework, the key parameters and their corresponding notations are summarized as follows:

- ,

- ,

- P: appears as an input in SMC design

- : appears in equivalent control term of torsional SMC

- , : reference bit trajectories generated by MPC.

These definitions ensure consistent variable usage throughout the control design, estimation, and simulation sections.

3.3. Sliding Mode Control Design

The core principle of SMC is to drive the system states onto a predefined sliding surface and maintain motion along this surface thereafter, despite disturbances or modeling inaccuracies. For the drillstring system, we define two sliding surfaces: one for torsional vibration control and one for axial vibration control. The sliding surface for the torsional (rotational) subsystem is defined as follows:

where

- is the angular velocity tracking error;

- is the actual angular velocity of the drill bit;

- is the desired angular velocity trajectory;

- is a scalar gain that determines the convergence rate.

Similarly, for the axial (longitudinal) dynamics, the sliding surface is defined as follows:

where

- is the axial velocity tracking error;

- is the actual drill bit velocity in the axial direction;

- is the desired axial velocity trajectory;

- is a gain for axial sliding dynamics.

The sliding variables and represent the deviation from the desired system behavior in both subsystems. The parameters and control the convergence speed of the tracking error. Driving these variables to zero ensures that the actual system state closely tracks the desired trajectory. Once the state reaches the sliding surface ( or ), the system behaves like a reduced-order dynamic system whose motion is constrained to that surface. These sliding surfaces are used to formulate the following SMC law:

where u is the control input, k is the control gain, and is a boundary layer width used to mitigate chattering via the saturation function. is the ideal control input that keeps the system on the sliding surface. It cancels out the known nominal dynamics of the system so that the only remaining part of the control law handles uncertainties and disturbances. To drive and to zero, we define control laws of the following form:

Here, and are the equivalent control inputs that cancel the nominal system dynamics, and and are gains controlling the robustness against disturbances. The saturation function with boundary layer width reduces chattering compared to the sign function. The robustness of the SMC depends critically on the proper selection of the switching gains (torsional subsystem) and (axial subsystem). These gains must be sufficiently large to dominate the total uncertainty in the system dynamics, which includes parameter variations, unmodeled nonlinearities, and external disturbances. To ensure the reachability of the sliding surface, the gain should satisfy the following:

where is an upper bound on the lumped uncertainty and is a small positive margin. In practice, the following steps are recommended:

- Estimate the maximum expected disturbance from experimental data or conservative system modeling.

- Choose , where is typically 5–10% of the maximum actuator capability.

- Validate the performance through simulation and tune based on observed trade-offs:

- If the system exhibits excessive chattering, reduce k or increase the boundary layer width .

- If convergence to the sliding surface is too slow or weak under disturbance, increase k.

This gain selection process balances robustness and control smoothness, ensuring stable tracking even under model uncertainties and communication delay. SMC ensures finite-time convergence and high robustness to parameter variations and disturbances, particularly important in drilling environments where rock interactions and bit friction are highly nonlinear and uncertain.

3.4. Model Predictive Control Design

MPC is employed to generate reference trajectories and for the SMC to track. These reference trajectories are optimized not only for setpoint tracking but also for minimizing harmful drillstring vibrations such as torsional stick–slip. A more general discrete-time prediction model, consistent with the structure of Equations (10) and (11), is adopted:

where denotes the system states at time k, including drill bit angular position , angular velocity , axial displacement , penetration rate and other variables, and . The control input vector consists of motor torque and axial force P. At each control step, MPC solves the following constrained finite-horizon optimization problem:

where N is the predictive window size, and the control input sequence is defined as , with denoting the control input at step i. The optimization problem includes the following:

- Q and R are weighting matrices for tracking error and control effort, respectively;

- is a scalar weight penalizing stick–slip severity;

- , defined in [46], represents the Stick–Slip Severity Index at step i, defined as:computed over a local sliding window.

The weighting coefficients in the MPC objective function were selected to balance vibration suppression, rate-of-penetration performance, and actuator limitations in a physically meaningful way. The tracking term promotes stable bit-speed regulation, the vibration-related term penalizes torsional oscillations associated with stick–slip, and the control-effort term limits overly aggressive surface actuation. Initial values were chosen based on engineering judgment and refined through iterative simulation to maintain low stick–slip severity while preserving satisfactory ROP performance. Parametric variations confirmed that increasing the vibration-related weight yields smoother operation at the cost of slightly reduced productivity, whereas decreasing it favors ROP but increases oscillatory behavior. Additional tests under different drillstring geometries, loading regimes, and formation parameters indicate that the selected weights maintain robust performance across a range of operating conditions. A more comprehensive multi-scenario and multi-objective optimization of the weighting structure will be pursued in future work to further strengthen controller adaptability and performance characterization.

This structure ensures that the control input anticipates and mitigates harmful vibrations while satisfying operational constraints. The constraints explicitly considered include the following:

- Torque limits: to ensure actuator safety and feasibility;

- Axial displacement limits: to prevent excessive mechanical stresses;

- Velocity and acceleration bounds: Constraints on and to avoid abrupt transitions and protect structural integrity.

- State soft constraints: Slack variables can be included for flexible enforcement, with corresponding penalties in the objective function;

- Input bounds: P and are restricted within operational ranges to prevent actuator saturation and excessive wear.

Incorporating the stick–slip severity into the MPC framework enables proactive suppression of torsional vibrations. The predictive nature of MPC, combined with vibration-aware cost design, enhances the operational safety, drilling performance, and system robustness under realistic, uncertain conditions.

4. Ensemble Kalman Filter Design

4.1. Measurements

In the design of the EnKF for the drillstring system, the choice of state variables and measurable outputs is critical to ensure accurate state estimation under nonlinear dynamics, time delay, and sensor noise. The EnKF is employed to estimate both directly measurable and unmeasurable system states, including angular and axial velocities, frictional states, and drill bit interaction forces. The measurement vector, based on available surface and downhole sensors, is

This reflects typical measurement availability in a drilling setup where surface (top drive) rotation and some limited axial feedback are accessible, while bit dynamics require estimation.

4.2. EnKF Equations

The EnKF extends the traditional Kalman framework by representing the state distribution with a finite ensemble of realizations. Instead of explicitly calculating Jacobians, the EnKF relies on Monte Carlo approximations of forecast error statistics and measurement update corrections. This makes it well-suited to strongly nonlinear systems like the string. Given an ensemble of particles at time step k, the update procedure is shown below. Each ensemble member is propagated forward through the nonlinear process model f:

The forecast mean and covariance are computed from the ensemble:

Each ensemble member is updated using the noisy measurement and a perturbed observation:

Here, is the output function. The Kalman gain is approximated from the ensemble statistics:

where and are sample cross-covariance and measurement covariance matrices estimated from the ensemble. EnKF handles high-dimensional, nonlinear states and improves resilience to sensor noise, bit–rock interaction irregularities, and delayed or missing data. represents process noise, capturing model uncertainty and stochastic effects in friction and formation variability. is measurement noise covariance matrix, based on sensor accuracy and noise characteristics. And ensemble size is a trade-off between estimation accuracy and computational cost; typical values range from 20 to 100.

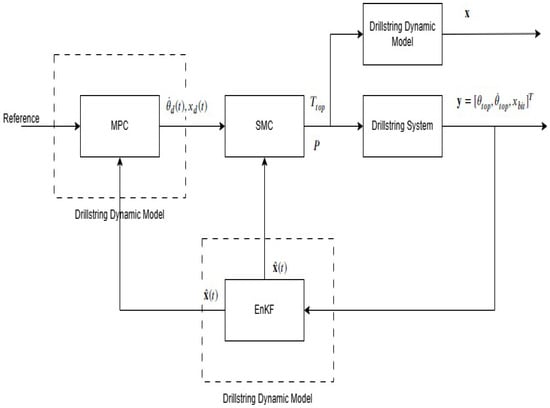

5. Hybrid Control Framework

In Figure 2, the integration of SMC with MPC forms a hybrid architecture capable of handling both fast local dynamics and global system constraints in real-time drilling operations. This dual-layer framework leverages the strengths of each control approach-robustness from SMC and prediction and constraint-handling from MPC-to achieve resilient, high-performance control in the presence of complex dynamics, noise, delays, and hardware limits. The typical control cycle proceeds as follows:

Figure 2.

Overall control and estimation architecture for the drillstring system.

- EnKF state estimation: The EnKF processes real-time sensor data and estimates the current system state vector , including velocities and internal states;

- MPC trajectory generation: The MPC uses estimated from EnKF as its starting point to solve a constrained optimization problem over a prediction horizon N. The resulting optimal reference trajectories and their derivatives are computed;

- Reference delivery: The predicted reference trajectory is sent to the SMC as the target to track at time t;

- SMC control synthesis: The SMC computes control inputs and P based on the predicted sliding surfaces and , and outputs the signal to the actuators at time t.

This coordination ensures that, despite actuation delay, the applied control aligns with the future system state when it becomes effective. The hybrid control structure provides several technical advantages over conventional approaches:

- Robust tracking and stability: SMC enforces convergence to reference trajectories even under bounded uncertainties and unmodeled nonlinearities such as bit-rock interactions and friction hysteresis;

- Constraint-aware optimization: MPC optimizes trajectories under hard constraints (torque, displacement, rate) and soft constraints (vibration suppression, smoothness), ensuring safe and efficient operation;

- Delay and disturbance mitigation: Predictive planning in MPC combined with state forecasting allows real-time delay compensation. The SMC switching law handles abrupt disturbances with high responsiveness;

- Separation of roles: The outer MPC layer shapes long-term behavior and respects system limits, while the inner SMC ensures fast and stable error correction in real time.

Effective performance of the integrated system depends on careful tuning of control and estimation parameters:

- SMC gains must be selected to ensure fast convergence without excessive chattering. Gains should exceed the maximum disturbance estimate by a safety margin;

- MPC horizon N and weight matrices determine optimization fidelity versus computational load. Longer horizons improve foresight, while higher penalty weights suppress excessive actuation;

- Boundary layer width in SMC should reflect actuator resolution and delay robustness. A wider boundary layer reduces chattering but may increase steady-state error.

The system is modular and suitable for deployment on embedded or distributed real-time systems. Each module operates at a different frequency to balance responsiveness and computational cost:

- SMC controller: Runs at high frequency (e.g., 1–2 Hz) to provide immediate reaction to state deviations;

- MPC optimizer: Executes at a lower frequency (e.g., 0.01–0.1 Hz), suitable for online quadratic programming solvers or convex approximations;

- EnKF estimator: Runs synchronously with sensor data acquisition (e.g., 1–2 Hz), updating state predictions for both control modules.

Parallel scheduling and non-blocking communication between modules ensure real-time feasibility. The modularity also allows for plug-and-play testing and selective upgrades.

6. Practical Considerations

6.1. Handling Data Quality Issues

In real-world drilling environments, sensor data is often affected not only by noise but also by errors and occasional data unavailability due to signal loss, latency, or hardware failure. These imperfections can significantly degrade the performance of estimation and control layers if not properly addressed.

The EnKF depends heavily on accurate and continuous measurements to update its internal state estimates. Noisy data increases estimation variance, and erroneous measurements (e.g., sensor spikes or outliers) can introduce large correction errors, particularly when the Kalman gain is high. During periods of data unavailability—such as sensor dropout or delayed transmission—the EnKF must operate in open-loop prediction mode, which increases the risk of divergence. To mitigate these challenges, several strategies can be employed. First, robust covariance tuning involves adjusting the measurement noise covariance matrix R to reflect the reliability of each sensor, thereby limiting overreaction to corrupted data. Second, outlier rejection techniques, such as statistical thresholding or Mahalanobis distance-based checks, can be used to identify and discard abnormal measurements before they are assimilated. Third, when measurements are missing, the filter can skip the update step and rely solely on model propagation; alternatively, missing values may be estimated through imputation methods such as last-value hold, linear interpolation, or model-driven prediction.

MPC relies on accurate state estimates as initial conditions for trajectory planning. When these estimates are noisy, biased, or partially missing, the resulting control actions may become suboptimal or even destabilizing. For instance, incorrect axial displacement estimates can lead to constraint violations or reactions to nonexistent bit bounce. To address this, one can preprocess state inputs using filtering techniques (e.g., low-pass or smoothed EnKF outputs), apply constraint softening via slack variables, and perform consistency checks to validate state integrity before optimization.

SMC is inherently robust to bounded disturbances but can be sensitive to measurement errors, particularly in fast-changing variables. Noise or transient dropout in velocity or acceleration estimates can result in incorrect computation of the sliding variable , leading to excessive chattering or degraded convergence. Additionally, inaccurate estimates of bit position or torque may misdirect control effort, especially when high gains are used. To mitigate these effects, filtered state observers can replace raw numerical differentiation for more reliable derivative estimation. The sliding surface design may also be adjusted by widening the boundary layer or introducing an adaptive gain to suppress the impact of transient noise. In scenarios of data unavailability, fallback control mechanisms—such as frozen control or last-known-good control—can be employed to maintain system stability.

A resilient control system should anticipate and mitigate data quality issues through a layered approach:

- Sensor fusion from redundant measurements (e.g., multiple encoders or accelerometers);

- Online monitoring of data quality metrics and automatic reconfiguration of EnKF gains;

- Transition to more robust estimation methods such as the Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) or particle filters for nonlinear and uncertain environments;

- Periodic recalibration and health checks of sensors during drilling pauses or transitions.

These strategies ensure that the MPC–SMC framework remains functional, stable, and reliable even under degraded or partial sensing conditions commonly encountered in downhole operations.

6.2. Adaptive Inputs Adjustment Under Vibration Detection

In real-world drilling operations, the pre-defined setpoints (same as the reference shown in Figure 2) for WOB, RPM, or ROP may not always lead to optimal or safe performance. Particularly during severe torsional or axial vibrations—such as stick–slip or bit bounce—these nominal setpoints may exacerbate dynamic instability or even cause mechanical failure. Therefore, an adaptive mechanism to adjust setpoints based on real-time vibration detection is crucial to improving system robustness and longevity.

The proposed hybrid control system can incorporate vibration-aware logic to adaptively modify the MPC reference trajectories and based on feedback from the EnKF-estimated state vector and its derivatives. Specifically, a vibration index defined as is computed from high-frequency variations in and :

where and are weighting factors determined based on the relative severity of torsional vs. axial oscillations. Thresholds and are then defined to guide adaptive behavior:

- If , the nominal setpoints are used;

- If , the system begins ramping down and increasing damping gain in the SMC;

- If , the system reduces WOB (if controllable) and switches to a vibration mitigation mode.

This strategy allows the MPC to generate more conservative trajectories during critical vibration events. For example, RPM setpoints may be lowered to avoid entering resonance zones, and ROP targets may be adjusted downward to prevent bit bounce. These adjusted setpoints are then fed to the SMC controller, which continues to ensure tight tracking while rejecting disturbances.

To avoid unnecessary setpoint oscillations due to measurement noise, a hysteresis band and time filter are applied to the vibration index . Additionally, the EnKF plays a key role in accurately estimating the vibration state and filtering out sensor noise, which directly supports more reliable triggering of adaptive logic. This closed-loop feedback structure not only improves safety but also increases system autonomy. Operators or supervisory controllers can configure the vibration thresholds and tuning weights according to formation properties or operational risk levels. Such adaptive control features are vital for the next generation of intelligent drilling systems, where responsiveness to downhole conditions is a key performance metric.

7. Case Study and Results

In this section, we conduct a series of simulation studies to evaluate the performance of the proposed hybrid control framework. Three scenarios are compared:

- Open-loop (No Control): Constant surface torque and WOB inputs are applied without any feedback control;

- Sliding Mode Control Only: A robust SMC tracks fixed references for the rotational velocity;

- MPC–SMC Hybrid Control: MPC optimizes time-varying reference trajectories, while SMC robustly tracks these references.

The drillstring model includes coupled axial-torsional dynamics and stochastic bit–rock interactions, and sensor noise. Measurement outputs are , and an EnKF is deployed for real-time state estimation. All simulations are carried out over a period of 100 s, with a system update time step of s.

7.1. Simulation Setup

The drillstring parameters used in the simulations are listed in Table 1. The surface drive torque is limited to Nm, and the axial force is constrained between 0 and 250 kN. The initial conditions represent a drillstring under pre-load with minor initial perturbations. The reference trajectory for bit RPM is initially set to 60 RPM.

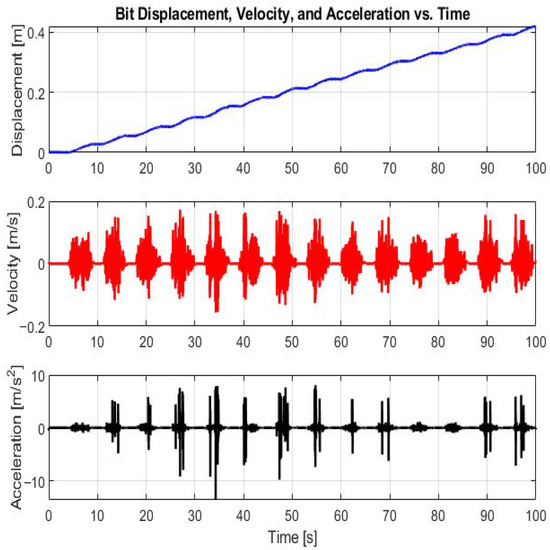

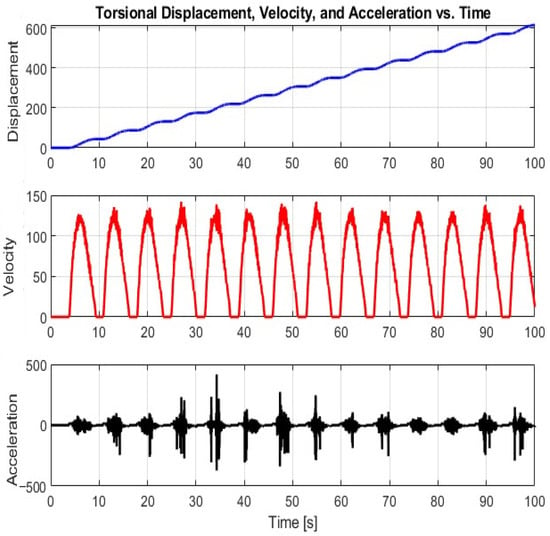

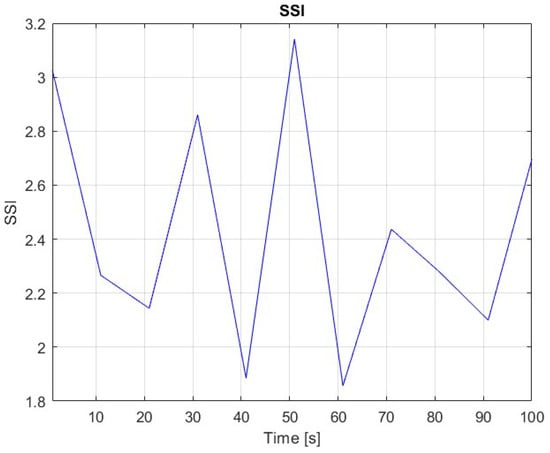

7.2. Open-Loop Behavior: Severe Stick–Slip

Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the bit rotational speed without any feedback control. Figure 4 shows the torsional dynamics under open-loop conditions, where pronounced stick–slip oscillations are evident in the bit’s rotational speed. The rotational velocity drops sharply towards zero and then abruptly increases, highlighting the chaotic behavior caused by the nonlinear interaction between the bit and the rock formation. The Stick–Slip Severity Index in this scenario reaches values above 3.2, indicating extremely unstable drilling conditions. These results emphasize the critical need for robust control strategies, such as sliding mode control and model predictive control, to mitigate harmful vibrations and ensure safe and efficient drilling operations.

Figure 3.

Bit axial behavior under open-loop control (no feedback).

Table 1.

Drillstring simulation parameters.

Table 1.

Drillstring simulation parameters.

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Young’s Modulus (E) | 220 GPa |

| Poisson’s Ratio () | 0.29 |

| Shear Modulus (G) | 85.3 GPa |

| Density () | 7800 kg/m3 |

| Pipe Outer Radius | 70 mm |

| Pipe Inner Radius | 59.5 mm |

| Collar Outer Radius | 70 mm |

| Collar Inner Radius | 38 mm |

| Pipe Length | 4733.6 m |

| Collar Length | 466.4 m |

| Bit Mass | 66.9 kg |

| Equivalent Bit Radius () | 0.0961 m |

| Friction Coefficient () | 0.4 |

| Number of Borehole Waves () | 4000 |

| Axial Damping Coefficients () | 0.15, 0.15 |

| Torsional Damping Coefficients () | 0.30, 0.30 |

| Sampling Time () | 0.01 s |

| Surface Stall Torque () | 10,000 Nm |

| Base Surface RPM | 60 RPM |

7.3. SMC Performance: Partial Suppression

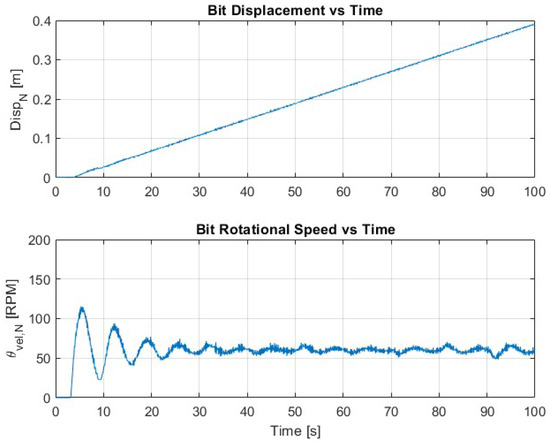

Figure 5 shows the bit behavior when the sliding mode controller is engaged. Compared to the open-loop case, SMC significantly reduces the amplitude and frequency of stick–slip. The SSI drops below 0.5 after an initial transient. The rotational speed stabilizes more effectively, demonstrating the robustness of SMC against unmodeled disturbances and nonlinearities. However, the axial displacement of the bit remains relatively low throughout the simulation, resulting in a reduced ROP compared to the desired trajectory. This limitation arises because SMC, while effective at suppressing high-frequency oscillations, lacks a predictive mechanism to adjust its control actions proactively based on future dynamics. As a result, the system fails to fully utilize its operational envelope, particularly in terms of axial advancement. Additionally, noticeable overshoots are observed following changes in the surface RPM setpoint, a consequence of the abrupt switching nature of sliding control. These observations highlight the need for an outer-loop trajectory planner, such as MPC, to complement SMC with smoother reference generation and constraint-aware optimization.

Figure 4.

Bit torsional behavior under open-loop control (no feedback). Severe stick–slip oscillations are observed.

Figure 5.

Bit depth and rotational speed under SMC only. Oscillations are partially suppressed, but transient overshoot remains.

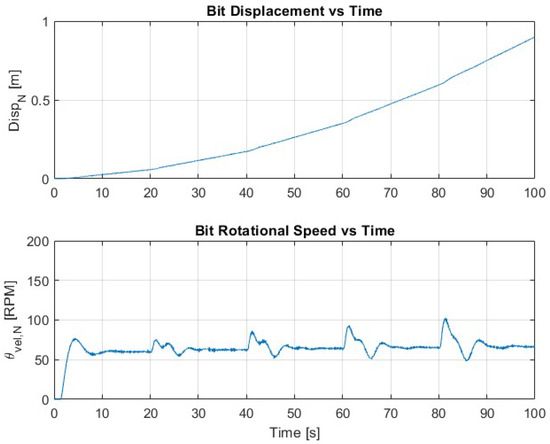

7.4. MPC–SMC Hybrid Control: Optimal Performance

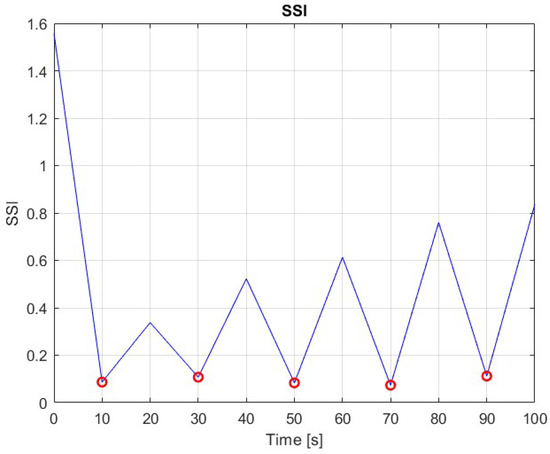

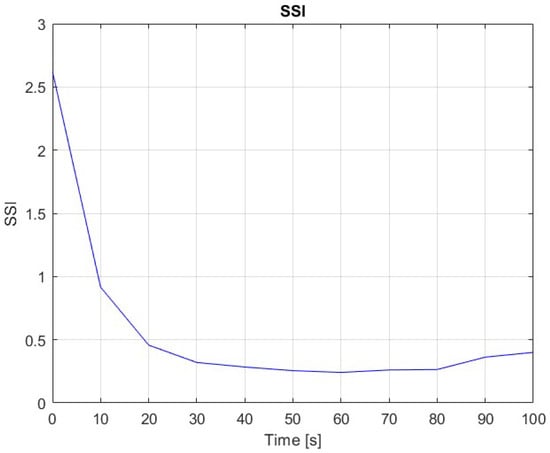

Figure 6 illustrates the system behavior under the hybrid MPC–SMC control scheme, where model predictive control provides optimized reference trajectories and sliding mode control ensures their robust execution. In this configuration, the system achieves near-ideal bit motion, with both axial and torsional oscillations effectively eliminated. The bit rotational speed follows a smooth and gradually increasing profile, as the MPC adapts the RPM setpoints over time in response to changing drilling conditions and predicted system dynamics. This adaptive modulation of surface RPM contributes directly to vibration suppression and improved operational safety. In parallel, the axial displacement of the bit increases steadily, reflecting a continuous and stable ROP that is significantly higher than in the SMC-only case. The coordinated behavior between the predicted trajectories and low-level control leads to efficient energy usage and minimized mechanical stress. Throughout the simulation, the Stick–SSI remains consistently below 0.2 (after the initialization, after each setpoint adjustment, see red circles in Figure 7), indicating a substantial reduction in harmful vibrations and confirming the effectiveness of the hybrid controller. By shaping feasible trajectories that respect physical constraints and optimizing system performance over a prediction horizon, MPC enhances not only the vibration mitigation but also the drilling efficiency. Meanwhile, SMC provides high-frequency disturbance rejection and ensures tight tracking of those reference commands despite external uncertainties and nonlinear bit–rock interactions. The result is a control strategy that combines robustness with foresight, offering a promising solution for real-time drilling automation.

Figure 6.

Bit depth and rotational speed under MPC–SMC hybrid control. Oscillations are minimized, and smooth tracking is achieved.

Figure 7.

Stick–Slip Severity Index (SSI) evolution for MPC–SMC controller.

Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 compare the evolution of the SSI across the three control cases: open-loop (no feedback), SMC only, and the proposed MPC–SMC hybrid controller. The SSI serves as a quantitative metric to evaluate the severity of torsional vibrations at the drill bit. High SSI values indicate pronounced stick–slip oscillations, while lower values correspond to smoother and more stable rotational behavior.

Figure 8.

Stick–Slip Severity Index (SSI) evolution for Open-loop.

Figure 9.

Stick–Slip Severity Index (SSI) evolution for SMC controller.

In the open-loop case, the SSI exhibits large and persistent oscillations, with values frequently exceeding 2.5 and peaking above 3.0. These extreme fluctuations are consistent with the uncontrolled bit dynamics shown earlier in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Without feedback, the system is unable to dampen torsional instability, leading to repeated episodes where the bit decelerates to near-zero rotational speed before rapidly accelerating again. The high SSI profile throughout the simulation highlights the inherent instability of operating under open-loop conditions and underscores the necessity for real-time vibration control.

When the sliding mode controller is applied, the SSI drops significantly, demonstrating the robustness and disturbance rejection capabilities of SMC. As shown in Figure 9, the SSI stabilizes below 0.5 shortly after the initial transient phase, marking a dramatic improvement over the open-loop case. This reduction reflects the ability of SMC to drive the system state onto a sliding surface and maintain bounded oscillations despite nonlinearities and model uncertainties. However, the SSI curve in the SMC case still shows minor spikes, particularly around periods of abrupt RPM change. These spikes correspond to transient overshoots observed in Figure 5, where the SMC lacks foresight into future dynamics and cannot proactively adjust to trajectory changes. While SMC alone is effective in stabilizing the system, it does not fully optimize drilling performance in terms of efficiency and smoothness.

In contrast, the MPC–SMC hybrid control achieves the most favorable SSI profile. As illustrated in Figure 7, the SSI remains consistently below 0.2 throughout the stabilization period (red circles). This superior performance results from the predictive capabilities of MPC, which generate reference trajectories that are inherently optimized to reduce torsional resonance and avoid excitation of stick–slip modes. By anticipating the system’s future behavior and enforcing constraints such as torque limits and desired ROP, the MPC component ensures that the references fed to SMC are smooth, feasible, and aligned with operational goals. The inner-loop SMC then robustly tracks these references, maintaining tight regulation even in the presence of disturbances or estimation inaccuracies.

7.5. Discussion

Several important observations arise from the case study. First, the open-loop scenario reveals inherent instability in the system, as the bit undergoes severe stick–slip oscillations and chaotic motion. Without any feedback control, these vibrations persist throughout the operation, making the drilling process both unsafe and inefficient. This result highlights the critical need for active vibration suppression strategies in rotary drilling systems.

When sliding mode control is introduced, the system experiences a significant improvement in stability. SMC effectively suppresses large-amplitude oscillations and robustly regulates bit behavior even in the presence of frictional nonlinearities and model uncertainties. However, its performance is not without limitations. Due to the discontinuous nature of its control law, SMC often introduces high-frequency chattering and noticeable overshoots, particularly during abrupt changes in the surface RPM setpoint. These drawbacks limit the controller’s ability to fully optimize performance and efficiency.

The incorporation of model predictive control addresses these challenges by introducing foresight into the control architecture. MPC anticipates future system dynamics and generates smooth, constraint-compliant reference trajectories that are well-suited for real-world drilling constraints. By shaping the desired bit motion in a predictive manner, the MPC reduces the likelihood of abrupt control actions and better accommodates actuator limitations. When used in conjunction with SMC as a tracking layer, the hybrid MPC–SMC framework achieves an excellent balance between robustness and performance. This layered control strategy leverages MPC’s optimization capabilities and SMC’s strong disturbance rejection to deliver superior results across a range of operating conditions. Quantitatively, the hybrid approach leads to a dramatic reduction in vibration severity. The SSI is reduced by over compared to the open-loop baseline, indicating a substantial improvement in bit–rock interaction stability and suggesting a potential increase in drilling efficiency and equipment longevity.

While vibration-hazard indices such as the Stick–Slip Severity Index are central to the control objectives in this study, their broader relevance lies in their strong operational and economic implications. Elevated torsional and axial vibrations are closely associated with accelerated bit wear, increased BHA failure probability, unplanned tripping events, and reduced drilling efficiency, all of which contribute directly to non-productive time and overall run cost. Consequently, reductions in vibration severity provide a practical and widely accepted proxy for improved operational performance. Nonetheless, vibration metrics alone do not fully capture the economic dimension of drilling. As future work, the control framework will be extended to incorporate energy-efficiency terms, bit-wear or life-cycle degradation models, and probabilistic failure indicators into the MPC cost function, enabling a more explicit balance between vibration suppression, drilling efficiency, and techno-economic objectives.

8. Conclusions and Future Work

This study presents a hybrid control framework that combines MPC and SMC to suppress drillstring vibrations and improve bit stability in rotary drilling operations. The results demonstrate that while open-loop control leads to severe stick–slip behavior and instability, the introduction of SMC substantially enhances robustness and damping capability. However, SMC alone exhibits limitations such as chattering and a lack of foresight during setpoint transitions. By integrating MPC as an outer loop for predictive trajectory generation, the hybrid MPC–SMC controller overcomes these shortcomings and achieves near-ideal performance. The system not only minimizes stick–slip oscillations—reducing the SSI by over 90%—but also improves the rate of penetration and operational safety. The EnKF, though not visualized explicitly, plays a critical role in enabling state estimation from noisy surface data, making the framework implementable in realistic field settings.

The proposed hybrid architecture effectively combines real-time adaptability, robustness, and predictive planning, making it highly suitable for automated drilling systems. Future work will focus on extending this framework to account for time-varying geological conditions and drilling disturbances through adaptive parameter tuning, as well as incorporating real-time bit–rock interaction models and torque-on-bit measurements to enhance estimation fidelity. Another important direction is the integration of energy-efficiency metrics into the MPC cost function, enabling optimization not only for vibration suppression but also for overall energy consumption. Experimental validation using hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) simulation or field data will also be pursued to verify controller performance under real operational constraints. In addition, future research will explore the integration of neural-network-based methods to further enhance system adaptability and computational efficiency. Neural networks offer promising capabilities for approximating complex bit–rock interaction dynamics, providing fast surrogate models for MPC prediction, and enabling online tuning of controller parameters as drilling conditions evolve. They may also serve as high-level decision-making modules within an intelligent drilling automation architecture, representing a natural extension of the presented physics-based control framework. These developments aim to bridge the gap between simulation and practice and further enable the deployment of intelligent, autonomous control in modern drilling operations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S. and J.C.; methodology, D.S.; software, D.S.; validation, D.S. and J.C.; formal analysis, D.S.; investigation, D.S. and J.C.; resources, D.S. and J.C.; data curation, D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S.; writing—review and editing, D.S.; visualization, D.S.; supervision, D.S.; project administration, D.S.; funding acquisition, D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Detournay, E.; Richard, T.; Shepherd, M. Drilling response of drag bits: Theory and experiment. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2008, 45, 1347–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritto, T.; Escalante, M.; Sampaio, R.; Rosales, M. Drill-string horizontal dynamics with uncertainty on the frictional force. J. Sound Vib. 2013, 332, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, J.M.; Yigit, A.S. Modeling and analysis of stick-slip and bit bounce in oil well drillstrings equipped with drag bits. J. Sound Vib. 2014, 333, 6885–6899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Vlajic, N.; Long, X.; Meng, G.; Balachandran, B. Coupled axial-torsional dynamics in rotary drilling with state-dependent delay: Stability and control. Nonlinear Dyn. 2014, 78, 1891–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemloonia, A.; Geoff Rideout, D.; Butt, S.D. A review of drillstring vibration modeling and suppression methods. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2015, 131, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarsnes, U.J.F.; Aamo, O.M. Linear stability analysis of self-excited vibrations in drilling using an infinite dimensional model. J. Sound Vib. 2016, 360, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiari-Nejad, F.; Hosseinzadeh, A. Nonlinear dynamic stability analysis of the coupled axial-torsional motion of the rotary drilling considering the effect of axial rigid-body dynamics. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2017, 88, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarsnes, U.J.F.; Shor, R.J. Torsional vibrations with bit off bottom: Modeling, characterization and field data validation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 163, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moraes, L.P.; Savi, M.A. Drill-string vibration analysis considering an axial-torsional-lateral nonsmooth model. J. Sound Vib. 2019, 438, 220–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabali, F.; Moradi, H.; Vossoughi, G. Coupling analysis and control of axial and torsional vibrations in a horizontal drill string. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 195, 107534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y.M.; Jin, H.S.; Kim, G.S.; Ri, K.S.; Yu, K.S.; Ri, H.G. Axial-torsional mode correlation analysis of a drill string system with non-smooth characteristics. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 218, 110870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Tang, L.; Yang, Y.; Dai, L.; Xiong, C. Drill string dynamics and experimental study of constant torque and stick-slip reduction drilling tool. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2024, 42, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpi, L.; Cayeux, E.; Time, R. Whirling dynamics of a drill-string with fluid–structure interaction. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 232, 212423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghgouei, H.; Lavrov, A.; Nermoen, A. Effect of drill string lateral vibrations on wellbore stability and optimal mud pressure determination. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 247, 213691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayer, F.; Vandiver, J.K.; Lee, H.Y. The Effect of Surface and Downhole Boundary Conditions on the Vibration of Drillstrings. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 23–26 September 1990; p. SPE–20447–MS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.P.; Teodoriu, C. Model Development of Torsional Drillstring and Investigating Parametrically the Stick-Slips Influencing Factors. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2013, 135, 013103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, A.; Soize, C.; Sampaio, R. Computational modeling of the nonlinear stochastic dynamics of horizontal drillstrings. Comput. Mech. 2015, 56, 849–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, P.; Rui, Z.; Jin, F. Modeling Friction Performance of Drill String Torsional Oscillation Using Dynamic Friction Model. Shock Vib. 2017, 2017, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengesdal, N.K.; Holden, C.; Pedersen, E. Component-Based Modeling and Simulation of Nonlinear Drill-String Dynamics. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2021, 144, 021801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castello, D.; Ritto, T. ABC for model selection and parameter estimation of drill-string bit-rock interaction models and stochastic stability. J. Sound Vib. 2023, 547, 117537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijun, N.; Guohao, Y.; Chengyun, M.; Gang, L.; Fei, M.; Kai, Z. Research on the influence factors of hydraulic oscillator on drag reduction efficiency in horizontal well drilling. Meas. Control 2024, 57, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkoub, M.; Zribi, M.; Elchaar, L.; Lamont, L. Robust μ-synthesis controllers for suppressing stick-slip induced vibrations in oil well drill strings. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2010, 23, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Girsang, I.P.; Dhupia, J.S. Identification and control of stick–slip vibrations using Kalman estimator in oil-well drill strings. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2016, 140, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Chavez, J.P.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Kuang, Y. Stick-slip suppression and speed tuning for a drill-string system via proportional-derivative control. Appl. Math. Model. 2020, 82, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavković, D.; Deur, J.; Lisac, A. A torque estimator-based control strategy for oil-well drill-string torsional vibrations active damping including an auto-tuning algorithm. Control Eng. Pract. 2011, 19, 836–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivantürk, C.; Chen, D.; van Oort, E. Torsional drillstring vibration modelling and mitigation with feedback control. In Proceedings of the SPE/IADC Drilling Conference and Exhibition, The Hague, The Netherlands, 14–16 March 2017; OnePetro: Richardson, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, L.; Hu, S. Analysis of stick-slip reduction for a new torsional vibration tool based on PID control. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part K J. Multi-Body Dyn. 2020, 234, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Srivastava, S.; Teodoriu, C.; Stan, M. Experimental Comparison of PID Based RPM Control for Long Horizontal vs. Vertical Drillstring. Preprints 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hichem, Z.A.; Hamza, A.; Mohamed, D.Z.; Madjid, K. PID-Based Kalman Filter Controller Design Stick-Slip Vibrations Suppression in Drill String Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Automatic Control (ICEEAC), Setif, Algeria, 12–14 May 2024; pp. 1–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Lu, C.; Wu, M.; He, Z.; Song, H.; Li, W. Fuzzy PID control for suppressing stick-slip vibration of drill-string system. In Proceedings of the 2022 China Automation Congress (CAC), Xiamen, China, 25–27 November 2022; pp. 5454–5459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meddah, S.; Doghmane, M.Z.; Tadjer, S.A.; Bougueroua, M.; Saighi, O. Fractional-order PID controller design for strongly coupled high-frequency axial–torsional vibrations in drill string system. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2025, 13, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Control of a class of multibody underactuated mechanical systems with discontinuous friction using sliding-mode. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2018, 40, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaziri, V.; Kapitaniak, M.; Wiercigroch, M. Suppression of drill-string stick–slip vibration by sliding mode control: Numerical and experimental studies. Eur. J. Appl. Math. 2018, 29, 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barjini, A.H.; Khoshnazar, M.; Moradi, H. Design of a sliding mode controller for suppressing coupled axial & torsional vibrations in horizontal drill strings using Extended Kalman Filter. J. Sound Vib. 2024, 586, 118477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghimehr, R.; Nikoofard, A.; Khaki Sedigh, A. Predictive-based sliding mode control for mitigating torsional vibration of drill string in the presence of input delay and external disturbance. J. Vib. Control 2020, 27, 2432–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zribi, F.; Sidhom, L.; Krama, A.; Gharib, M. Enhancement of drill string system operations with adaptive robust controller and hardware in-the-loop validation. J. Sound Vib. 2023, 556, 117716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soimu, A.; Stinga, F. Predictive control of torsional drillstring vibrations. In Proceedings of the 2016 20th International Conference on System Theory, Control and Computing (ICSTCC), Sinaia, Romania, 13–15 October 2016; pp. 796–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ni, H.; Wang, R. Feasibility study of nonlinear model predictive control in mitigating stick slip in drilling. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 621, p. 012150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz Neto, H.; Trindade, M. Control of drill string torsional vibrations using optimal static output feedback. Control Eng. Pract. 2023, 130, 105366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobern, M.E.; Perry, C.A.; Barbely, J.A.; Burgess, D.E.; Wassell, M.E. Drilling Tests of an Active Vibration Damper. In Proceedings of the SPE/IADC Drilling Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 20–22 February 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liao, H.; Liu, Y.; Guan, Z. Vibration Analysis of Drill-String with Downhole Shock Absorption Intensifier; SSRN: Rochester, New York, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Velychkovych, A.; Mykhailiuk, V.; Andrusyak, A. Evaluation of the Adaptive Behavior of a Shell-Type Elastic Element of a Drilling Shock Absorber with Increasing External Load Amplitude. Vibration 2025, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gou, W.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Z. Anti-Vibration Method for the Near-Bit Measurement While Drilling of Pneumatic Down-the-Hole Hammer Drilling. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, H.; Liu, C.; Qi, D. A torsional-axial vibration analysis of drill string endowed with kinematic coupling and stochastic approach. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 198, 108157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, L.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Qiao, J.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, D. Dynamic analysis of drill string vibration enhanced by neural network based models. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 246, 213618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, C.; Millwater, H.; Gray, K. Classification of drilling stick slip severity using machine learning. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 179, 1023–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).