Retinal Tortuosity Biomarkers as Early Indicators of Disease: Validation of a Comprehensive Analytical Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Background on Tortuosity Metrics

- 1.

- Arc-to-Chord Ratio-Based Features: These features rely on the ratio between the arc length and the chord length of a blood vessel segment, providing a measure of the relative length increase due to tortuosity [18].

- 2.

- Local Curvature-Based Features: These features are derived from curvature measurements at stationary points along blood vessel segments, capturing local variations in curvature [8].

- 3.

2.2. Proposed Methodology

- 1.

- Segment retinal blood vessels, select segments of similar length and caliber, and order vessels by increasing tortuosity or adopt an existing dataset (as in Section 2.3)

- 2.

- Design or adopt a suitable resampling method and evaluate its effectiveness (as described in Section 2.5).

- 3.

- Develop or adopt an ensemble of tortuosity features, then estimate them utilizing the dataset from step 1 (as described in Section 2.4.1 and Section 2.4.2).

- 4.

- Test the invariability of tortuosity features to scaling (as in Section 2.6).

- 5.

- Evaluate tortuosity features using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient on the dataset from step 1 (as shown in Section 3.1).

- 6.

- Expand dataset from step 1, using data augmentation and repeat the evaluation of tortuosity features and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient analysis (as illustrated in Section “Augmentation Strategy” and results shown in Appendix C and Appendix D).

- 7.

- Analyze the performance of the tortuosity features ensemble using Gaussian process regression, using dataset from step 6 (as in Section 3.2).

- 8.

- Perform feature selection to identify the most relevant features for accurate tortuosity assessment (as described in Section 3.2).

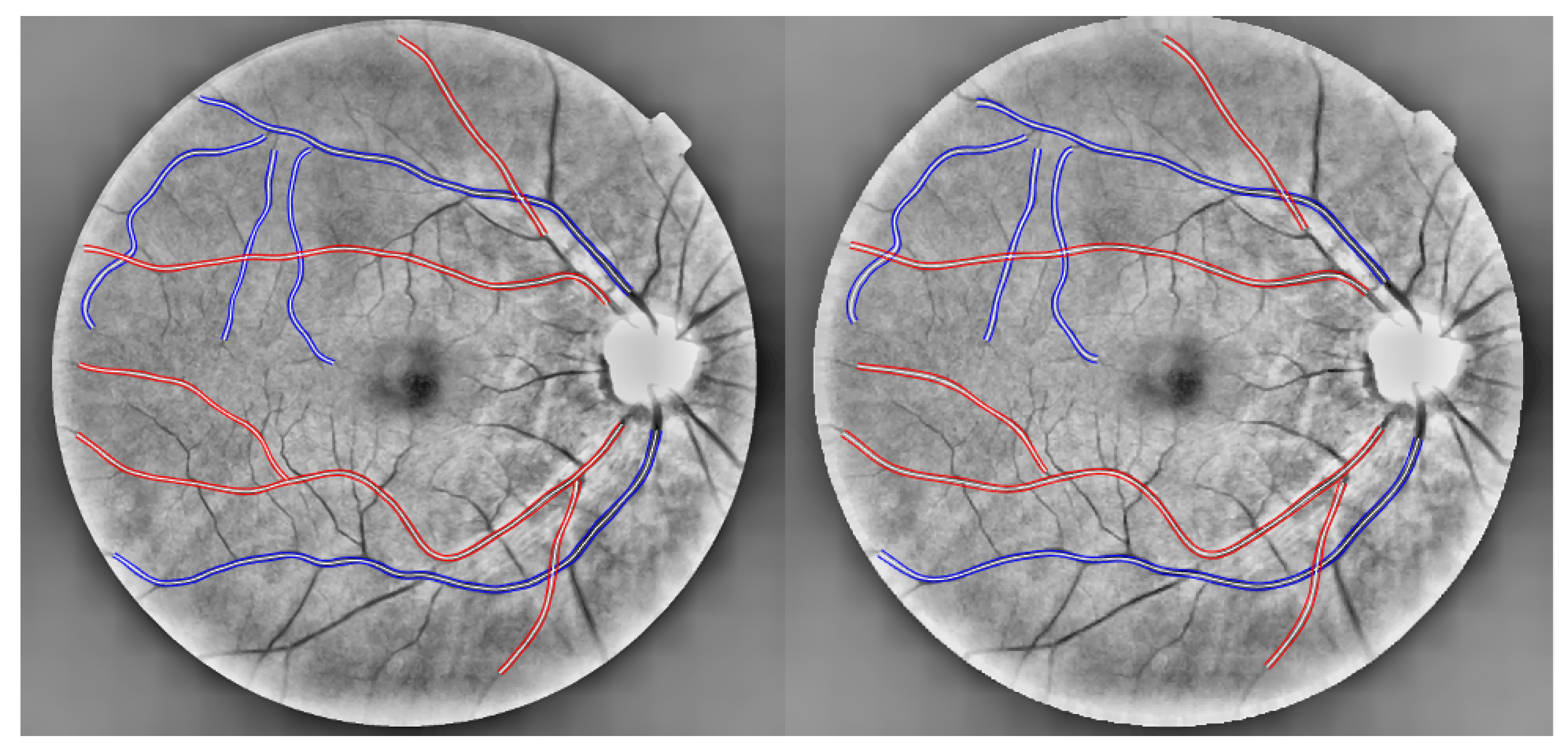

2.3. Datasets

Augmentation Strategy

2.4. Proposed Framework

2.4.1. Tortuosity Feature Ensemble

Structural Approach Features (S)

Distance Approach Features (D)

Curvature Approach Features (C)

Combined Approach Features (Co)

Signal Approach Features (Si)

- 1.

- The displacement points: the distances between each point in the vessel segment and its chord.

- 2.

- The first derivative of the x-coordinates along the centerline of the vessel segment.

- 3.

- The second derivative of the x-coordinates along the centerline of the vessel segment.

- 4.

- The signed curvature at each point along the vessel segment.

2.4.2. Framework’s Features Estimation

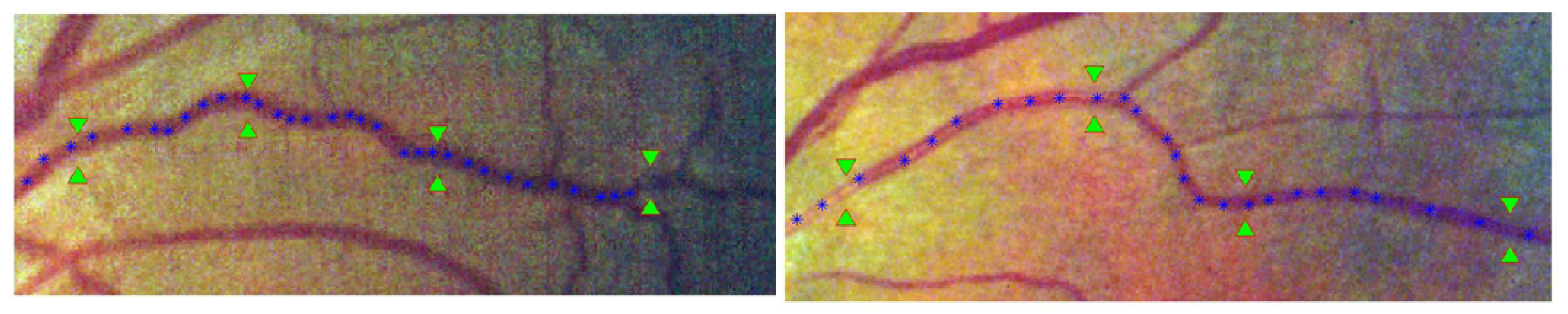

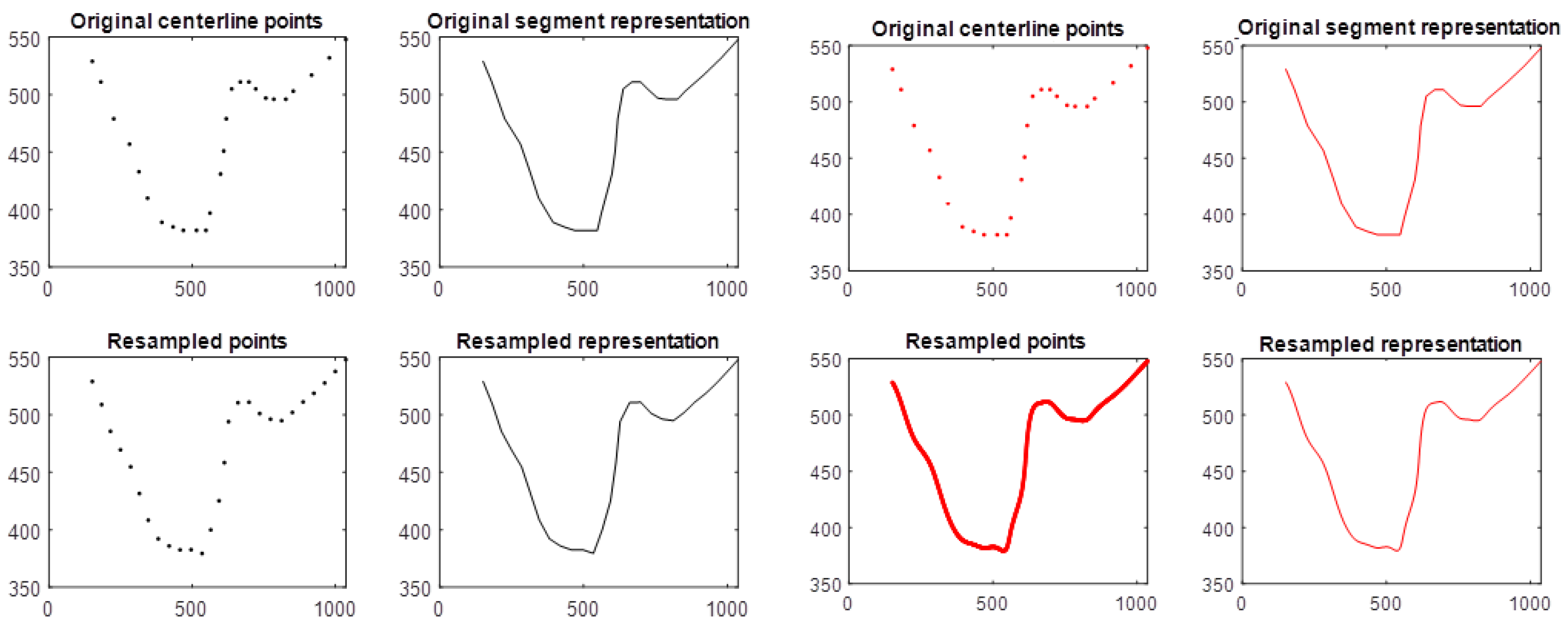

Centerline Points Resampling

Length Measurement

Feature Groups

2.5. Resampling Approach

Shape-Fidelity Evaluation of the Resampling Approaches

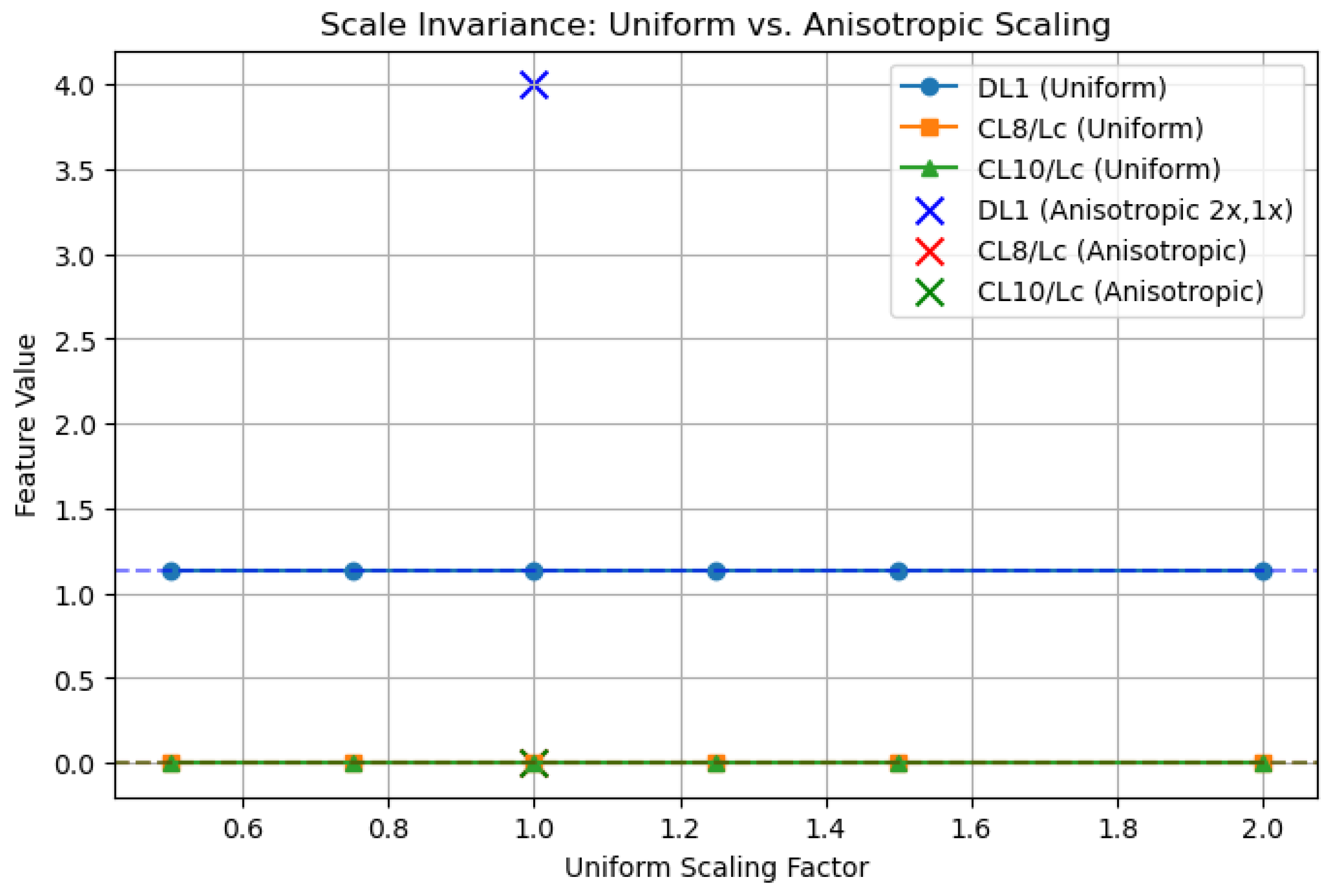

2.6. Scale Variation

- Invariant/Stable features

- Sensitive features

- Extra-sensitive features

- Extremely-sensitive features

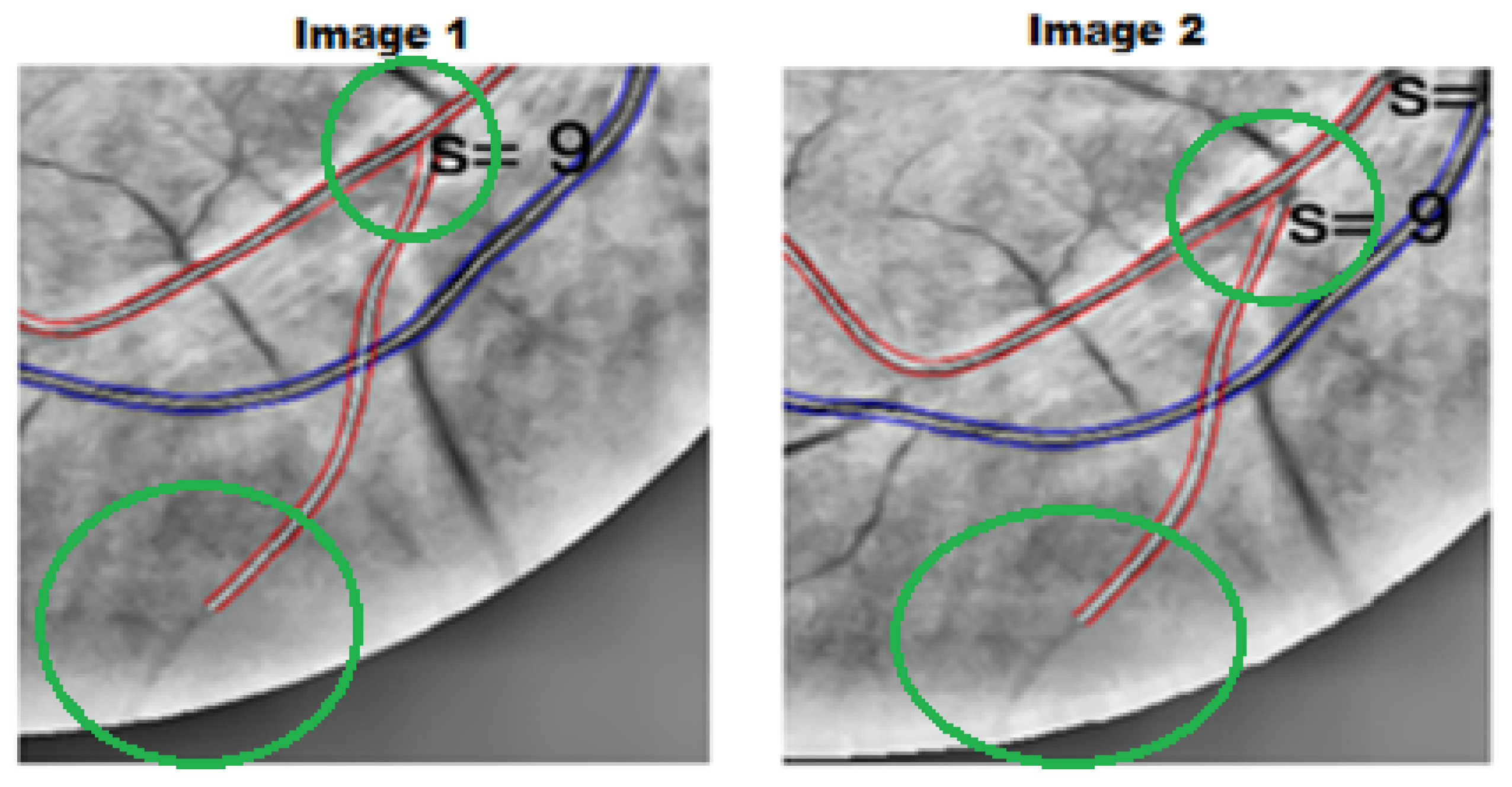

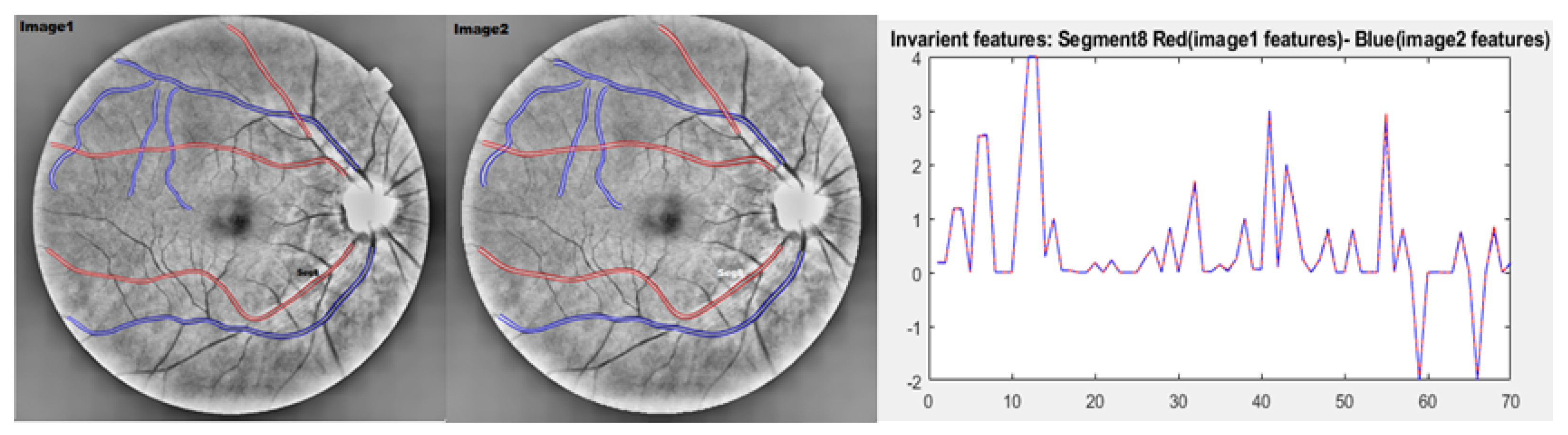

2.6.1. Evaluation of the Absolute Differences Between Image 1 and Image 2 Features

2.6.2. Validation of Scale-Invariant Features

- DL1: Defined as a ratio of distances within the vessel, DL1 = . Under uniform scaling by factor s, and , yielding = = = DL1.

- CL8/Lc and CL10/Lc: Normalized by chord length , these features satisfy CL8n = CL8/ and CL10n = CL10/. Uniform scaling by s gives and similarly for CL10n.

2.7. Spearman’s Correlation and Gaussian Process Regression Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient Analysis

- Structural Features: Arterial correlations were significant for SP1 and SP2 ( = 0.810 and = 0.806), while SP4 showed a strong negative correlation ( = −0.842). Veins exhibited weaker correlations overall, with SP5 achieving the highest ( = 0.353).

- Distance-Based Features: DL1 demonstrated strong performance for both arteries ( = 0.855) and veins ( = 0.644).

- Combined Features: CoL1 achieved the highest correlations for arteries and veins ( = 0.863 and = 0.541, respectively). Other features such as CoP1 and CoP3 also performed well in the arteries, with moderate correlations ( = 0.733 and = 0.729).

- Curvature-Based Features: Group 1: CL3 and CL4 showed the strongest correlations for both arteries and veins ( = 0.807 and = 0.792). Group 2: CL8 and CL9 stood out, with values of 0.818 (arteries) and 0.802 (veins). Group 3: CL11 achieved the highest correlation overall ( = 0.896 for arteries, = 0.766 for veins). Group 4: CP3 performed best among the group, with ( = 0.895) for arteries and ( = 0.773) for veins.

- Signal-Based Features: Group 1: SiP3, SiP5, and SiP8 exhibited strong performance, with all equally reporting ( = 0.794) for veins and SiP6 reporting ( = 0.855) the highest for arteries. Group 2: SiP14 had the highest correlation for arteries ( = 0.833), while SiP11 was most effective for veins ( = 0.711). Group 4: SiP20 performed well across both vessel types ( = 0.725 for arteries, = 0.711 for veins).

3.2. Gaussian Process Regression Analysis Feature Selection Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient Analysis on RET-TORT Dataset and Augmented RET-TORT Dataset

4.2. Resampling Approaches

4.3. Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) Performance

4.4. Innovation and Clinical Relevance

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

- Feature Effectiveness: Structural and distance-based features excelled in detecting arterial tortuosity, while curvature and signal-based features were particularly effective for veins. Top-performing features included DL1, CL11, CP3, and SiP6, with the latter two features proposed in this study.

- Resampling Benefits: The study demonstrated that the proposed resampling method 2 (1EPS) produces more representative vessel segments and therefore produces more accurate tortuosity evaluations compared to approaches such as method 1. Spearman’s correlation analysis confirmed that the choice of resampling method significantly impacts vessel measurements and tortuosity estimation. While Method 1 showed higher performance for specific features (e.g., CL11 and SiP1), Method 2 outperformed Method 1 in terms of performance and, presumably, greater accuracy, especially for distance-based features such as DL1.

- Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) Modelling: The use of MRMR-selected features and Squared Exponential kernels achieved high predictive accuracy of the clinical order of both arteries and veins, demonstrating practical applicability for detecting specific early structural changes along the course of blood vessels.

6. Recommendations and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Feature Groups

Features Estimation

- Feature : Combines (arc-over-chord ratio) and (number of maxima points).

- Feature : Combines and (sum of areas under sub-curves).

- Feature : Combines and (average height of sub-curves).

- first differences between the points

- Displacement points: The distances between the underlying chord (straight line connecting the endpoints) and each point along the blood vessel segment.

- First derivative: The rate of change of the x-coordinates of the segment centerline points.

- Second derivative: The rate of change of the first derivative, providing information about curvature changes.

- Signed curvature: The curvature values at each point along the blood vessel segment.

| Index | Type | Code | Description | Source | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Combined | CoP2 | Path-over-chord: Adds sub-curve heights (VP1). | Proposed | EXTRA-SENSITIVE |

| 2 | Combined | CoP1 | Arc-over-chord combined with the number of maxima points along a blood vessel segment. | Proposed | INVARIANT |

| 3 | Combined | CoP3 | Path-over-chord: Adds sub-curve under-spaces (VP2). | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 4 | Curvature G4 | CP2 | Sum of the absolute first derivatives along a blood vessel segment, normalized by the sample interval. | Proposed | INVARIANT |

| 5 | Curvature G4 | CP3 | Sum of the absolute second derivatives along a blood vessel segment, normalized by the sample interval. | Proposed | INVARIANT |

| 6 | Curvature G4 | CP4 | Sum of the absolute third derivatives along a blood vessel segment, normalized by the sample interval. | Proposed | INVARIANT |

| 7 | Curvature G4 | CP1 | Sum of combined unsigned curvature and absolute differences of gradients along a segment. | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 8 | Signal G1 | SiP2 | FFT measure using the displacement points and the curvature. | Proposed | EXTRA-SENSITIVE |

| 9 | Signal G1 | SiP4 | FFT measure using the second derivatives and path over the chord. | Proposed | INVARIANT |

| 10 | Signal G1 | SiP6 | FFT measure using curvature and path over the chord. | Proposed | INVARIANT |

| 11 | Signal G1 | SiP7 | FFT measure using slopes and paths over the chord. | Proposed | INVARIANT |

| 12 | Signal G1 | SiP1 | FFT measure using displacement points and path over the chord. | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 13 | Signal G1 | SiP3 | FFT using the first derivatives and curvature. | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 14 | Signal G1 | SiP5 | FFT measure using the second derivatives and curvature. | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 15 | Signal G1 | SiP8 | FFT measure using slope and curvature. | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 16 | Signal G2 | SiP11 | Sum of the magnitude using second derivatives. | Proposed | INVARIANT |

| 17 | Signal G2 | SiP12 | Sum of the magnitude using curvature. | Proposed | INVARIANT |

| 18 | Signal G2 | SiP9 | Sum of the magnitude using displacement points. | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 19 | Signal G2 | SiP10 | Sum of magnitude using first derivatives. | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 20 | Signal G2 | SiP13 | Sum of the magnitude norm by path length using slope. | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 21 | Signal G2 | SiP14 | Sum of magnitude using slope. | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 22 | Signal G3 | SiP15 | Sum of the abs angles of first derivatives norm by path length. | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 23 | Signal G3 | SiP16 | Sum of the abs angles of curvature points norm by path length. | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 24 | Signal G3 | SiP17 | Sum of the abs angles of slopes along segment norm by path length. | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 25 | Signal G4 | SiP18 | Magnitude variance using first derivatives. | Proposed | INVARIANT |

| 26 | Signal G4 | SiP19 | Magnitude variance using first derivatives and norm by path length. | Proposed | INVARIANT |

| 27 | Signal G4 | SiP20 | Magnitude variance using curvature. | Proposed | INVARIANT |

| 28 | Structural | SP4 | Sum of sub-curves spaces. | Proposed | EXTRA-SENSITIVE |

| 29 | Structural | SP1 | Sub-curves number. | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 30 | Structural | SP2 | Maxima points. | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 31 | Structural | SP3 | Minima points. | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 32 | Structural | SP5 | Curves heights. | Proposed | SENSITIVE |

| 33 | Combined | CoL1 | Tortuosity measure by Grisan. | Literature | INVARIANT |

| 34 | Combined | CoL2 | Inflection count metric 1. | Literature | SENSITIVE |

| 35 | Curvature G1 | CL4 | Total squared unsigned curvature. | Literature | SENSITIVE |

| 36 | Curvature G1 | CL1 | Total signed curvature. | Literature | SENSITIVE |

| 37 | Curvature G1 | CL2 | Total squared signed curvature. | Literature | SENSITIVE |

| 38 | Curvature G1 | CL3 | Total unsigned curvature. | Literature | SENSITIVE |

| 39 | Curvature G2 | CL10 | Total squared unsigned curvature over chord length. | Literature | INVARIANT |

| 40 | Curvature G2 | CL6 | Total squared signed curvature over chord length. | Literature | INVARIANT |

| 41 | Curvature G2 | CL7 | Total unsigned curvature over arc length. | Literature | INVARIANT |

| 42 | Curvature G2 | CL8 | Total unsigned curvature over chord length. | Literature | INVARIANT |

| 43 | Curvature G2 | CL9 | Total squared unsigned curvature over arc length. | Literature | INVARIANT |

| 44 | Curvature G2 | CL5 | Total squared signed curvature norm by arc length. | Literature | INVARIANT |

| 45 | Curvature G3 | CL11 | Tortuosity measure by Rashmi. | Literature | EXTREMELY-SENSITIVE |

| 46 | Curvature G3 | CL12 | Tortuosity coefficient. | Literature | INVARIANT |

| 47 | Curvature G3 | CL13 | Mean direction angle change. | Literature | INVARIANT |

| 48 | Distance | DL1 | Arc over chord. | Literature | INVARIANT |

| 49 | Distance | Lc | Arc Length measured using differentiation. | - | - |

| 50 | Distance | Lc2 | Path length using the sum of the geodesic distances between each two consecutive points along the segment. | - | - |

| 51 | Distance | Lx | Chord length measured using the Euclidean distance. | - | - |

Appendix B. Scale Variation

| Feature Sensitivity | Feature Index | Min | Max | Range | Mean | Std |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invariant | SiP4 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| SiP20 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | |

| SiP11 | 0.0000 | 0.0011 | 0.0011 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | |

| CoL1 | 0.0000 | 0.0020 | 0.0020 | 0.0005 | 0.0007 | |

| CL12 | 0.0000 | 0.0014 | 0.0014 | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | |

| CP4 | 0.0000 | 0.0015 | 0.0015 | 0.0006 | 0.0005 | |

| SiP12 | 0.0000 | 0.0054 | 0.0054 | 0.0008 | 0.0016 | |

| SiP19 | 0.0002 | 0.0018 | 0.0016 | 0.0008 | 0.0004 | |

| SiP7 | 0.0000 | 0.0075 | 0.0075 | 0.0012 | 0.0023 | |

| CP3 | 0.0004 | 0.0071 | 0.0067 | 0.0020 | 0.0027 | |

| CoP1 | 0.0002 | 0.0062 | 0.0060 | 0.0020 | 0.0021 | |

| CL7 | 0.0001 | 0.0092 | 0.0092 | 0.0028 | 0.0032 | |

| CL8 | 0.0002 | 0.0104 | 0.0102 | 0.0031 | 0.0036 | |

| CL5 | 0.0002 | 0.0161 | 0.0159 | 0.0033 | 0.0048 | |

| CL6 | 0.0002 | 0.0181 | 0.0179 | 0.0037 | 0.0054 | |

| CL13 | 0.0004 | 0.0136 | 0.0132 | 0.0052 | 0.0053 | |

| DL1 | 0.0009 | 0.0212 | 0.0203 | 0.0067 | 0.0073 | |

| CP2 | 0.0001 | 0.0183 | 0.0182 | 0.0083 | 0.0055 | |

| SiP6 | 0.0012 | 0.0230 | 0.0217 | 0.0084 | 0.0072 | |

| SiP18 | 0.0005 | 0.0248 | 0.0243 | 0.0097 | 0.0079 | |

| CL9 | 0.0018 | 0.0434 | 0.0417 | 0.0135 | 0.0133 | |

| CL10 | 0.0022 | 0.0484 | 0.0461 | 0.0148 | 0.0147 |

| Feature Sensitivity | Feature Index | Min | Max | Range | Mean | Std |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitive | CP1 | 0.0002 | 0.0945 | 0.0944 | 0.0192 | 0.0288 |

| SiP1 | 0.0001 | 0.0964 | 0.0963 | 0.0232 | 0.0387 | |

| SiP10 | 0.0100 | 0.0865 | 0.0765 | 0.0370 | 0.0276 | |

| SP5 | 0.0000 | 0.3888 | 0.3888 | 0.0477 | 0.1209 | |

| CoP3 | 0.0013 | 0.3866 | 0.3853 | 0.0549 | 0.1182 | |

| SiP15 | 0.0019 | 0.6899 | 0.6880 | 0.0964 | 0.2096 | |

| SiP13 | 0.0009 | 0.9550 | 0.9541 | 0.2269 | 0.3391 | |

| CoL2 | 0.0018 | 1.7117 | 1.7100 | 0.2707 | 0.5841 | |

| SiP14 | 0.0049 | 1.0886 | 1.0837 | 0.2826 | 0.3948 | |

| SP1 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.3000 | 0.4830 | |

| CL2 | 0.0899 | 0.8216 | 0.7318 | 0.3969 | 0.2589 | |

| SP3 | 0.0000 | 2.0000 | 2.0000 | 0.4000 | 0.8433 | |

| SiP17 | 0.0082 | 1.6611 | 1.6529 | 0.4985 | 0.5462 | |

| SP2 | 0.0000 | 2.0000 | 2.0000 | 0.5000 | 0.8498 | |

| SiP16 | 0.0147 | 1.3279 | 1.3132 | 0.5625 | 0.4673 | |

| CL1 | 0.0341 | 3.7711 | 3.7370 | 0.6257 | 1.1236 | |

| SiP3 | 0.7370 | 3.3020 | 2.5650 | 1.4851 | 0.8409 | |

| CL3 | 0.7840 | 3.3770 | 2.5930 | 1.5090 | 0.8632 | |

| SiP5 | 0.7949 | 3.3890 | 2.5941 | 1.5172 | 0.8644 | |

| SiP8 | 0.0449 | 3.3935 | 3.3486 | 1.5919 | 0.9456 | |

| CL4 | 2.4414 | 32.5369 | 30.0955 | 12.2729 | 9.7811 | |

| SiP9 | 0.0035 | 56.9894 | 56.9859 | 13.2256 | 20.3982 | |

| Extra-sensitive | SiP2 | 1.2150 | 423.095 | 421.8799 | 134.13 | 138.67 |

| CoP2 | 0.001 | 1320.095 | 1320.094 | 217.030 | 408.17 | |

| SP4 | 0.000 | 1320.077 | 1320.0772 | 217.031 | 408.17 | |

| Extremely-sensitive | CL11 | 1.61 | 1433.52 | 1431.9 | 382.32 | 562.79 |

| Feature Sensitivity | Feature Index | Min | Max | Range | Mean | Std |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invariant | SiP4 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| SiP20 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| CP4 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | |

| SiP11 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

| SiP12 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

| SiP7 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

| CL12 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | |

| CoL1 | 0.0000 | 0.0010 | 0.0010 | 0.0005 | 0.0006 | |

| CP3 | 0.0005 | 0.0012 | 0.0008 | 0.0007 | 0.0003 | |

| SiP19 | 0.0006 | 0.0010 | 0.0003 | 0.0008 | 0.0002 | |

| CL5 | 0.0009 | 0.0026 | 0.0017 | 0.0019 | 0.0007 | |

| CL7 | 0.0009 | 0.0032 | 0.0023 | 0.0020 | 0.0010 | |

| CL6 | 0.0009 | 0.0029 | 0.0020 | 0.0021 | 0.0008 | |

| CL8 | 0.0009 | 0.0037 | 0.0028 | 0.0022 | 0.0012 | |

| CoP1 | 0.0005 | 0.0062 | 0.0057 | 0.0026 | 0.0025 | |

| SiP13 | 0.0009 | 0.0083 | 0.0074 | 0.0044 | 0.0030 | |

| CL13 | 0.0006 | 0.0109 | 0.0103 | 0.0044 | 0.0045 | |

| CL9 | 0.0018 | 0.0106 | 0.0088 | 0.0048 | 0.0041 | |

| CL10 | 0.0022 | 0.0123 | 0.0101 | 0.0055 | 0.0047 | |

| DL1 | 0.0009 | 0.0172 | 0.0162 | 0.0065 | 0.0076 | |

| SiP6 | 0.0012 | 0.0181 | 0.0168 | 0.0073 | 0.0077 | |

| CP1 | 0.0029 | 0.0183 | 0.0154 | 0.0077 | 0.0071 | |

| CP2 | 0.0049 | 0.0183 | 0.0135 | 0.0094 | 0.0060 |

| Feature Sensitivity | Feature Index | Min | Max | Range | Mean | Std |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitive | SiP18 | 0.0049 | 0.0248 | 0.0199 | 0.0134 | 0.0083 |

| SiP1 | 0.0001 | 0.0964 | 0.0963 | 0.0244 | 0.0480 | |

| SiP15 | 0.0019 | 0.0533 | 0.0514 | 0.0289 | 0.0258 | |

| SiP14 | 0.0077 | 0.0948 | 0.0870 | 0.0392 | 0.0382 | |

| SiP10 | 0.0102 | 0.0614 | 0.0513 | 0.0406 | 0.0240 | |

| SP5 | 0.0000 | 0.3888 | 0.3888 | 0.1089 | 0.1874 | |

| CoP3 | 0.0013 | 0.3866 | 0.3853 | 0.1152 | 0.1826 | |

| CL2 | 0.1038 | 0.8216 | 0.7178 | 0.3514 | 0.3360 | |

| SiP16 | 0.0147 | 1.1476 | 1.1329 | 0.4184 | 0.4993 | |

| CoL2 | 0.0018 | 1.7117 | 1.7100 | 0.4313 | 0.8536 | |

| SiP17 | 0.0082 | 1.6611 | 1.6529 | 0.4925 | 0.7883 | |

| SP1 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.5000 | 0.5774 | |

| SP3 | 0.0000 | 2.0000 | 2.0000 | 0.5000 | 1.0000 | |

| SP2 | 0.0000 | 2.0000 | 2.0000 | 0.7500 | 0.9574 | |

| CL1 | 0.0341 | 3.7711 | 3.7370 | 1.1565 | 1.7683 | |

| SiP3 | 0.7370 | 2.1459 | 1.4089 | 1.4338 | 0.6781 | |

| SiP8 | 0.7691 | 2.2151 | 1.4459 | 1.4391 | 0.6755 | |

| CL3 | 0.7938 | 2.1892 | 1.3954 | 1.4670 | 0.6703 | |

| SiP5 | 0.7949 | 2.2074 | 1.4124 | 1.4743 | 0.6751 | |

| CL11 | 1.6062 | 19.2774 | 17.6712 | 6.5067 | 8.5260 | |

| CL4 | 2.4414 | 25.3618 | 22.9204 | 13.3971 | 9.5436 | |

| SiP9 | 0.0035 | 56.9894 | 56.9859 | 19.5890 | 26.8732 | |

| Extra-sensitive | SiP2 | 46.67 | 423.095 | 376.42 | 162.42 | 176.23 |

| Extremely-sensitive | SP4 | 0 | 1320.077 | 1320.08 | 460.7 | 594.25 |

| CoP2 | 0.0013 | 1320.1 | 1320.094 | 460.70 | 594.26 |

Appendix C. Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient Analysis on the RET-TORT

| Feature Group Index | Arteries- | Veins- |

|---|---|---|

| SP1 | 0.810 | 0.234 |

| SP2 | 0.806 | 0.230 |

| SP3 | 0.760 | 0.256 |

| SP4 | −0.842 | −0.213 |

| SP5 | 0.24 | 0.353 |

| Feature Group Index | Arteries- | Veins- |

|---|---|---|

| DL1 | 0.855 | 0.644 |

| Lx | - | - |

| Lc | - | - |

| Lc2 | - | - |

| Feature Group Index | Arteries- | Veins- |

|---|---|---|

| CoL1 | 0.863 | 0.541 |

| CoL2 | 0.361 | 0.015 |

| CoP1 | 0.733 | 0.489 |

| CoP2 | 0.131 | 0.299 |

| CoP3 | 0.729 | 0.481 |

| Curvature-Group | Feature Group Index | Arteries- | Veins- |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | CL1 | 0.201 | 0.238 |

| G1 | CL2 | 0.390 | 0.207 |

| G1 | CL3 | 0.807 | 0.792 |

| G1 | CL4 | 0.807 | 0.792 |

| G2 | CL5 | 0.309 | 0.192 |

| G2 | CL6 | 0.375 | 0.240 |

| G2 | CL7 | 0.750 | 0.797 |

| G2 | CL8 | 0.818 | 0.797 |

| G2 | CL9 | 0.773 | 0.802 |

| G2 | CL10 | 0.815 | 0.799 |

| G3 | CL11 | 0.896 | 0.766 |

| G3 | CL12 | 0.487 | 0.664 |

| G3 | CL13 | −0.138 | 0.126 |

| G4 | CP1 | 0.797 | 0.793 |

| G4 | CP2 | −0.858 | −0.628 |

| G4 | CP3 | 0.895 | 0.773 |

| G4 | CP4 | 0.739 | 0.731 |

| Signal-Group | Feature Group Index | Arteries- | Veins- |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | SiP1 | −0.089 | 0.145 |

| G1 | SiP2 | −0.481 | −0.448 |

| G1 | SiP3 | 0.824 | 0.794 |

| G1 | SiP4 | 0.642 | 0.691 |

| G1 | SiP5 | 0.824 | 0.794 |

| G1 | SiP6 | 0.855 | 0.644 |

| G1 | SiP7 | 0.643 | 0.595 |

| G1 | SiP8 | 0.830 | 0.794 |

| G2 | SiP9 | −0.044 | 0.173 |

| G2 | SiP10 | −0.135 | −0.065 |

| G2 | SiP11 | 0.710 | 0.711 |

| G2 | SiP12 | 0.446 | 0.551 |

| G2 | SiP13 | 0.519 | 0.646 |

| G2 | SiP14 | 0.833 | 0.619 |

| G3 | SiP15 | −0.255 | −0.031 |

| G3 | SiP16 | −0.013 | −0.420 |

| G3 | SiP17 | −0.105 | 0.310 |

| G4 | SiP18 | −0.845 | −0.633 |

| G4 | SiP19 | −0.820 | −0.509 |

| G4 | SiP20 | 0.725 | 0.711 |

Appendix D. Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient Analysis on the Augmented RET-TORT Dataset

| Feature Group Index | Arteries- | Veins- |

|---|---|---|

| SP1 | 0.614 | 0.257 |

| SP2 | 0.512 | 0.315 |

| SP3 | 0.570 | 0.118 |

| SP4 | −0.453 | 0.092 |

| SP5 | 0.135 | 0.043 |

| Feature Group Index | Arteries- | Veins- |

|---|---|---|

| DL1 | 0.626 | 0.400 |

| Lx | - | - |

| Lc | - | - |

| Lc2 | - | - |

| Feature Group Index | Arteries- | Veins- |

|---|---|---|

| CoL1 | 0.420 | 0.180 |

| CoL2 | 0.462 | 0.249 |

| CoP1 | 0.557 | 0.359 |

| CoP2 | 0.19 | 0.391 |

| CoP3 | 0.479 | 0.277 |

| Curvature-Group | Feature Group Index | Arteries- | Veins- |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | CL1 | 0.108 | 0.118 |

| G1 | CL2 | 0.235 | 0.101 |

| G1 | CL3 | 0.596 | 0.468 |

| G1 | CL4 | 0.561 | 0.409 |

| G2 | CL5 | 0.180 | 0.109 |

| G2 | CL6 | 0.245 | 0.123 |

| G2 | CL7 | 0.526 | 0.422 |

| G2 | CL8 | 0.560 | 0.477 |

| G2 | CL9 | 0.408 | 0.428 |

| G2 | CL10 | 0.547 | 0.4019 |

| G3 | CL11 | 0.277 | 0.288 |

| G3 | CL12 | 0.320 | 0.490 |

| G3 | CL13 | −0.034 | 0.094 |

| G4 | CP1 | 0.448 | 0.577 |

| G4 | CP2 | −0.615 | −0.431 |

| G4 | CP3 | 0.587 | 0.547 |

| G4 | CP4 | 0.522 | 0.381 |

| Signal-Group | Feature Group Index | Arteries- | Veins- |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | SiP | 0.049 | 0.022 |

| G1 | SiP2 | 0.272 | −0.290 |

| G1 | SiP3 | 0.560 | 0.439 |

| G1 | SiP4 | 0.370 | 0.419 |

| G1 | SiP5 | 0.700 | 0.494 |

| G1 | SiP6 | 0.526 | 0.459 |

| G1 | SiP7 | 0.245 | 0.328 |

| G1 | SiP8 | 0.591 | 0.617 |

| G2 | SiP9 | 0.042 | 0.062 |

| G2 | SiP10 | −0.151 | −0.100 |

| G2 | SiP11 | 0.474 | 0.431 |

| G2 | SiP12 | 0.337 | 0.375 |

| G2 | SiP13 | 0.283 | 0.288 |

| G2 | SiP14 | 0.291 | 0.305 |

| G3 | SiP15 | −0.169 | 0.0310 |

| G3 | SiP16 | 0.001 | −0.277 |

| G3 | SiP17 | 0.050 | 0.222 |

| G4 | SiP18 | 0.576 | 0.381 |

| G4 | SiP19 | 0.512 | −0.349 |

| G4 | SiP20 | 0.525 | 0.339 |

References

- Eisalo, A.; Raitta, C.; Kala, R.; Halonen, P.I. Fluorescence angiography of the fundus vessels in aortic coarctation. Br. Heart J. 1970, 32, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Crowe, R.J.; Kohner, E.M.; Owen, S.J.; Robinson, D.M. The retinal vessels in congenital cyanotic heart disease. Med. Biol. Illus. 1969, 19, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kanski, J.J.; Bowling, B. Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach, 7th ed.; Elsevier Health Sciences: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Longmuir, S.Q.; Mathews, K.D.; Longmuir, R.A.; Joshi, V.; Olson, R.J.; Abràmoff, M.D. Retinal arterial but not venous tortuosity correlates with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy severity. J. AAPOS 2010, 14, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahe, F.; Sharfaei, S.; Pitliya, A.; Jafarizade, M.; Seifirad, S.; Habibi, S.; Chi, G. Coronary artery tortuosity: A narrative review. Coron. Artery Dis. 2020, 31, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, M.; Panuccio, G.; Bisdas, T.; Berekoven, B.; Torsello, G.; Austermann, M. Tortuosity is the significant predictive factor for renal branch occlusion after branched endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2016, 51, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, M. Evaluating Retinal Blood Vessels’ Abnormal Tortuosity in Digital Image Fundus. Master’s Thesis, University of Lincoln, Lincoln, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, W.E.; Goldbaum, M.; Côté, B.; Kube, P.; Nelson, M.R. Measurement and classification of retinal vascular tortuosity. Int. J. Med. Inform. 1999, 53, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grisan, E.; Foracchia, M.; Ruggeri, A. A novel method for the automatic grading of retinal vessel tortuosity. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2008, 27, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onkaew, D.; Turior, R.; Uyyanonvara, B.; Nishihara, A.; Sinthanayothin, C. Automatic retinal vessel tortuosity measurement using curvature of improved chain code. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electrical, Control and Computer Engineering (InECCE), Kuantan, Malaysia, 21–22 June 2011; pp. 183–186. [Google Scholar]

- Chavan, A.; Mago, G.; Balaji, J.J.; Lakshminarayanan, V. A new method for quantification of retinal blood vessel characteristics. In Ophthalmic Technologies XXXI; SPIE: Bellingham, DC, USA, 2021; Volume 11623, pp. 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, W.; Handayani, A. Retinal blood vessels tortuosity measurement. In Proceedings of the IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 31 October–3 November 2023; pp. 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan, A.; Aurell, E.; Tibblin, G. Signs in the fundus oculi and arterial hypertension: Unconventional assessment and significance. Bull. World Health Organ. 1967, 36, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, M.; Hunter, A.; Al-Diri, B. Quantifying retinal blood vessels’ tortuosity. In Proceedings of the 2015 Science and Information Conference (SAI), London, UK, 28–30 July 2015; pp. 687–693. [Google Scholar]

- Chetia, S.; Nirmala, S.R. Polynomial modeling of retinal vessels for tortuosity measurement. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 39, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, M.A.P.; Amaral, C.E.V.; Ferreira, M.A.T. Retinal vascular tortuosity: Mechanisms and measurements. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 31, 1497–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, H.E.; Cao, J.; Wasi, M.; Feldon, S.E.; Shahidi, M. Variability of retinal vessel tortuosity measurements using a semiautomated method applied to fundus images in subjects with papilledema. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, W.E.; Goldbaum, M.; Cote, B.; Kube, P.; Nelson, M.R. Automated measurement of retinal vascular tortuosity. In Proceedings of the AMIA Annual Fall Symposium, Nashville, TN, USA, 25–29 October 1997; p. 459. [Google Scholar]

- Grisan, E.; Foracchia, M.; Ruggeri, A. A novel method for the automatic evaluation of retinal vessel tortuosity. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Cancun, Mexico, 17–21 September 2003; pp. 866–869. [Google Scholar]

- Azegrouz, H.; Trucco, E.; Dhillon, B.; MacGillivray, T.; MacCormick, I.J. Thickness dependent tortuosity estimation for retinal blood vessels. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, New York, NY, USA, 30 August–3 September 2006; pp. 4675–4678. [Google Scholar]

- Bullitt, E.; Gerig, G.; Pizer, S.M.; Lin, W.; Aylward, S.R. Measuring tortuosity of the intracerebral vasculature from MRA images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2003, 22, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turior, R.; Uyyanonvara, B. Curvature-based tortuosity evaluation for infant retinal images. J. Inf. Eng. Appl. 2012, 2, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty, G.; Varro, J. A quantitative index for the measurement of the tortuosity of blood vessels. Med. Eng. Phys. 2000, 22, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrinos, K.V.; Pilu, M.; Fisher, R.B.; Trahanias, P. Image Processing Techniques for the Quantification of Atherosclerotic Changes; Technical Report; Department of Artificial Intelligence, University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- D’Errico, J. Interparc. MATLAB Function, MATLAB Central File Exchange. 2023. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/34874-interparc (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Al-Diri, B.; Hunter, A.; Steel, D. An active contour model for segmenting and measuring retinal vessels. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2009, 28, 1488–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosling, J. Introductory Statistics; Pascal Press: Glebe, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nafia, T.; Handayani, A. Quantification of retinal vascular tortuosity: Evaluation on different numbers of sampling points. In Proceedings of the 2018 2nd International Conference on Biomedical Engineering (IBIOMED), Bali, Indonesia, 24–26 July 2018; pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar]

| Group | Sub-Group | Index | Code | Formula | Source | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance-Approach | 1 | DL1 | Equation (A1) | [8] | Invariant | |

| 2 | Lx | Equation (1) | ||||

| 3 | Lc2 | Equation (3) | ||||

| 4 | Lc1 | Equation (2) | ||||

| Structural-Approach | 5 | SP1 | Description in Appendix A | Proposed | Sensitive | |

| 6 | SP2 | Proposed | Sensitive | |||

| 7 | SP3 | Proposed | Sensitive | |||

| 8 | SP4 | Proposed | Extra-Sensitive | |||

| 9 | SP5 | Proposed | Sensitive | |||

| Combined-Approach | 10 | CoL1 | Equation (A2) | [9] | Invariant | |

| 11 | CoL2 | Equation (A3) | [21] | Sensitive | ||

| 12 | CoP1 | Equation (A4) | Proposed | Invariant | ||

| 13 | CoP2 | Equation (A5) | Proposed | Extra-Sensitive | ||

| 14 | CoP3 | Equation (A6) | Proposed | Invariant | ||

| Curvature-Approach | Group 1 | 15 | CL1 | Equation (A8) | [8] | Sensitive |

| 16 | CL2 | Equation (A9) | [8] | Sensitive | ||

| 17 | CL3 | Equation (A10) | [8] | Sensitive | ||

| 18 | CL4 | Equation (A11) | [8] | Sensitive | ||

| Group 2 | 19 | CL5 | Equation (A12) | [8] | Invariant | |

| 20 | CL6 | Equation (A13) | [8] | Invariant | ||

| 21 | CL7 | Equation (A14) | [8] | Invariant | ||

| 22 | CL8 | Equation (A15) | [8] | Invariant | ||

| 23 | CL9 | Equation (A16) | [8] | Invariant | ||

| 24 | CL10 | Equation (A17) | [8] | Invariant | ||

| Group 3 | 25 | CL11 | Equation (A22) | [22] | Extremely-Sensitive | |

| 26 | CL12 | Equation (A23) | [23] | Invariant | ||

| 27 | CL13 | Equation (A24) | [24] | Invariant | ||

| Group 4 | 28 | CP1 | Equation (A18) | Proposed | Sensitive | |

| 29 | CP2 | Equation (A19) | Proposed | Invariant | ||

| 30 | CP3 | Equation (A20) | Proposed | Invariant | ||

| 31 | CP4 | Equation (A21) | Proposed | Invariant | ||

| Signal-Approach | Group 1 | 32 | SiP1 | Equation (A25) | Proposed | Sensitive |

| 33 | SiP2 | Proposed | Extra-Sensitive | |||

| 34 | SiP3 | Proposed | Sensitive | |||

| 35 | SiP4 | Proposed | Invariant | |||

| 36 | SiP5 | Proposed | Sensitive | |||

| 37 | SiP6 | Proposed | Invariant | |||

| 38 | SiP7 | Proposed | Invariant | |||

| 39 | SiP8 | Proposed | Sensitive | |||

| Group 2 | 40 | SiP9 | Proposed | Sensitive | ||

| 41 | SiP10 | Proposed | Sensitive | |||

| 42 | SiP11 | Proposed | Invariant | |||

| 43 | SiP12 | Proposed | Invariant | |||

| 44 | SiP13 | Proposed | Sensitive | |||

| 45 | SiP14 | Proposed | Sensitive | |||

| Group 3 | 46 | SiP15 | Proposed | Sensitive | ||

| 47 | SiP 16 | Proposed | Sensitive | |||

| 48 | SiP 17 | Proposed | Sensitive | |||

| Group 4 | 49 | SiP18 | Proposed | Invariant | ||

| 50 | SiP19 | Proposed | Invariant | |||

| 51 | SiP20 | Proposed | Invariant |

| Resample Approach | Length Metric | Mean Relative Error in Arc Length | Mean Hausdorff Distance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | V | A | V | ||

| Resample 1 | 0.0035 | 0.0023 | 27.9947 | 27.2125 | |

| 0.2520 | 0.2835 | ||||

| Resample 2 (1EPS) | 0.0037 | 0.0037 | 28.6641 | 28.0586 | |

| 0.0270 | 0.0323 | ||||

| Feature | Metric | Original | Resample 1 | Resample 2 (1EPS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | V | A | V | A | V | ||

| Chord length (Lx) | (1) | 886.2037 | 730.1342 | 886.2037 | 730.1342 | 886.2037 | 730.1342 |

| Arc Length (Lc1) | (2) | 999.4621 | 795.0340 | 1001.7 | 799.03 | 1002.3 | 799.163 |

| Arc Length (Lc2) | (3) | 1059.6 | 813.2823 | 1294.8 | 1047.8 | 1003.3 | 800.1698 |

| Author | Framework | Literature (Grisan 2008) [9] | Literature (Chuang 2023 [12]) | Resample Method 1 | Resample Method 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | Artery | Vein | Artery | Vein | Artery | Vein | Artery | Vein | |

| [8] | DL1 | 0.792 | 0.656 | 0.829 | 0.632 | 0.843 | 0.638 | 0.855 | 0.644 |

| [8] | CL3 | 0.922 | 0.837 | 0.818 | 0.881 | 0.822 | 0.775 | 0.807 | 0.792 |

| [8] | CL4 | 0.925 | 0.826 | 0.844 | 0.876 | 0.822 | 0.775 | 0.807 | 0.792 |

| [8] | CL7 | 0.919 | 0.814 | 0.785 | 0.868 | 0.800 | 0.772 | 0.750 | 0.797 |

| [8] | CL9 | 0.917 | 0.773 | 0.823 | 0.871 | 0.804 | 0.773 | 0.773 | 0.802 |

| [8] | CL8 | 0.939 | 0.842 | 0.803 | 0.886 | 0.806 | 0.778 | 0.818 | 0.797 |

| [8] | CL10 | 0.928 | 0.804 | 0.838 | 0.876 | 0.814 | 0.776 | 0.815 | 0.799 |

| [24] | CL13 | 0.920 | 0.814 | 0.675 | 0.842 | −0.708 | −0.692 | −0.138 | 0.126 |

| [21] | CoL2 | 0.648 | 0.575 | 0.009 | 0.493 | 0.440 | 0.345 | 0.361 | 0.015 |

| [9] | CoL1 | 0.949 | 0.853 | 0.723 | 0.834 | 0.917 | 0.753 | 0.863 | 0.541 |

| [22] | CL11 | - | - | - | - | 0.927 | 0.809 | 0.896 | 0.766 |

| [7] | CoP1 | - | - | - | - | 0.756 | 0.485 | 0.733 | 0.489 |

| [7] | CoP3 | - | - | - | - | 0.864 | 0.566 | 0.729 | 0.481 |

| [7] | SiP6 | - | - | - | - | 0.779 | 0.794 | 0.855 | 0.644 |

| [7] | SiP1 | - | - | - | - | 0.919 | 0.703 | 0.710 | 0.711 |

| Model | Training | Testing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MSE | MAE | MAE | MSE | RMSE | |||

| Rational quadratic GPR | 0.00036 | 0.00000 | 1 | 0.00025 | 0.00125 | 0.00000 | 0.00157 | 0.99997 |

| Squared exponential GPR | 0.00022 | 0.00000 | 1 | 0.00016 | 0.00011 | 0.0000000197 | 0.00014 | 1 |

| Exponential GPR | 0.07606 | 0.00579 | 0.93702 | 0.06071 | 0.04802 | 0.00349 | 0.05910 | 0.95931 |

| Model | Training | Testing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MSE | MAE | MAE | MSE | RMSE | |||

| Rational quadratic GPR | 0.0003414 | 0.0000001 | 0.9999987 | 0.0002495 | 0.0001345 | 0.0000000 | 0.0001741 | 0.9999997 |

| Squared exponential GPR | 0.0005840 | 0.0000003 | 0.9999961 | 0.0002643 | 0.0002441 | 0.0000001 | 0.0002550 | 0.9999993 |

| Exponential GPR | 0.1578929 | 0.0249302 | 0.7180713 | 0.1156539 | 0.1077298 | 0.0222542 | 0.1491786 | 0.7609155 |

| Model | Training | Testing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MSE | MAE | MAE | MSE | RMSE | |||

| Rational quadratic GPR | 0.0762 | 0.0058 | 0.9371 | 0.0624 | 0.0694 | 0.0048 | 0.0597 | 0.9417 |

| Squared exponential GPR | 0.0775 | 0.0060 | 0.9350 | 0.0630 | 0.0694 | 0.0048 | 0.0597 | 0.9417 |

| Matern 5/7 GPR | 0.0738 | 0.0054 | 0.9410 | 0.0602 | 0.0694 | 0.0048 | 0.0596 | 0.9418 |

| Exponential GPR | 0.0889 | 0.0079 | 0.9144 | 0.0742 | 0.0899 | 0.0081 | 0.0745 | 0.9024 |

| Model | Training | Testing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MSE | MAE | MAE | MSE | RMSE | |||

| Rational quadratic GPR | 0.1422 | 0.0202 | 0.7715 | 0.1031 | 0.1335 | 0.0178 | 0.1030 | 0.8086 |

| Squared exponential GPR | 0.1422 | 0.0202 | 0.7715 | 0.1031 | 0.1335 | 0.0178 | 0.1030 | 0.8086 |

| Matern 5/7 GPR | 0.1422 | 0.0202 | 0.7715 | 0.1030 | 0.1341 | 0.0180 | 0.1035 | 0.8068 |

| Exponential GPR | 0.1677 | 0.0281 | 0.6819 | 0.1208 | 0.1586 | 0.0252 | 0.1185 | 0.7297 |

| Feature Group | Common Features Between A and V | Unique for A | Unique for V |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural approach | - | SP4, SP3, SP1 | - |

| Distance approach | DL1 | - | - |

| Combined approach | CoL2, CoL1, CP1, CP2 | CoP1, CoP3 | CoP2 |

| Curvature approach | CL12, CL8, CL4, CL10 | CP3, CL4, CL9 | CL3, CP2, CL11, CL13, CL1, CL3, CL5, CL6 |

| Signal approach | SiP12, SiP18, SiP20, SiP11, SiP5, SiP19 | SiP6, SiP2 | SiP3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdalla, M.; Habib, M.; Triantafyllou, A.; Cuayáhuitl, H.; Al-Diri, B. Retinal Tortuosity Biomarkers as Early Indicators of Disease: Validation of a Comprehensive Analytical Framework. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13136. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413136

Abdalla M, Habib M, Triantafyllou A, Cuayáhuitl H, Al-Diri B. Retinal Tortuosity Biomarkers as Early Indicators of Disease: Validation of a Comprehensive Analytical Framework. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13136. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413136

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdalla, Mowda, Maged Habib, Areti Triantafyllou, Heriberto Cuayáhuitl, and Bashir Al-Diri. 2025. "Retinal Tortuosity Biomarkers as Early Indicators of Disease: Validation of a Comprehensive Analytical Framework" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13136. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413136

APA StyleAbdalla, M., Habib, M., Triantafyllou, A., Cuayáhuitl, H., & Al-Diri, B. (2025). Retinal Tortuosity Biomarkers as Early Indicators of Disease: Validation of a Comprehensive Analytical Framework. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13136. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413136