Abstract

Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer (DWPT) systems require analytical models capable of capturing time-varying coupling and multi-transmitter interactions. However, most existing formulations address only static Wireless Power Transfer (WPT) or single-transmitter configurations, offering limited applicability to realistic DWPT scenarios. This paper addresses this gap by developing a comprehensive analytical framework for Series–Series (SS) compensated DWPT systems, supporting general n-transmitter/m-receiver architectures. The model is derived from coupled RLC circuit equations and expressed in normalized time- and frequency-domain forms, enabling analysis of resonance behavior, transient dynamics, and mutual-inductance variations during vehicle motion. To represent the continuous receiver motion, we establish a coupling-coefficient distribution covering the operating range of to . The framework is then applied to three representative cases: a dynamic baseline, sequential transmitter activation, and simultaneous multi-transmitter activation. The study investigates system performance across varying operating frequencies and receiver positions to evaluate efficiency characteristics for , , and wireless power transfer configurations. The proposed analytical framework provides a scalable basis for control development, transmitter coordination, and future real-time DWPT implementation.

1. Introduction

The global push for decarbonized transportation has significantly accelerated the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs), consequently intensifying the demand for robust and scalable charging infrastructure. Despite notable advancements in battery energy density and range, conventional plug-in charging continues to present substantial bottlenecks. Challenges such as limited charging station availability, extended recharge times, and the inconvenience of frequent stops pose considerable hurdles, particularly for high-mileage fleets like public buses, taxis, and logistics vehicles [1,2,3,4].

In response, Wireless Power Transfer (WPT) has emerged as a transformative technology, facilitating contactless energy transfer through magnetic coupling and eliminating the need for physical connectors [5,6,7,8]. Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer (DWPT), a subset of WPT enabling in-motion charging, has garnered significant interest due to its potential to extend vehicle range, reduce battery size, and optimize charging demand distribution over time and geographical areas [9,10,11,12,13]. DWPT systems operate via a network of transmitting coils embedded in the road, which transfer energy to a vehicle’s receiving coils through resonant inductive coupling. This approach promises enhanced vehicle uptime, more efficient grid utilization, and improved user convenience.

At their core, Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer (DWPT) systems leverage resonant inductive coupling, where both transmitter and receiver coils are tuned to a common frequency. This tuning minimizes reactive losses and enables efficient energy transfer over moderate distances, which has been demonstrated in foundational studies on strongly coupled magnetic resonances and inductive charging for electric vehicles. However, the overall performance of DWPT systems is highly dependent on the precise control and coordination of transmitter segments. This is particularly critical in dynamic scenarios, where the vehicle’s receiving coil moves continuously across multiple roadway-embedded transmitters, causing variations in mutual inductance, phase relationships, and coupling coefficients [3,14,15,16].

Over the past decade, a wide range of strategies have been developed for transmitter control in DWPT systems. Early research was primarily concerned with static WPT configurations, in which a single transmitter coil was aligned with a stationary receiver [17,18,19], and while these static systems were valuable for establishing the theoretical foundations of resonant inductive power transfer and for modeling near-field efficiency [6], they are impractical for moving vehicles because of their discontinuous alignment and inability to maintain continuous power flow. This limitation prompted the transition toward dynamic architectures, where transmitter activation strategies such as sequential and simultaneous coil excitation have been investigated to support uninterrupted charging during vehicle motion [2,20,21].

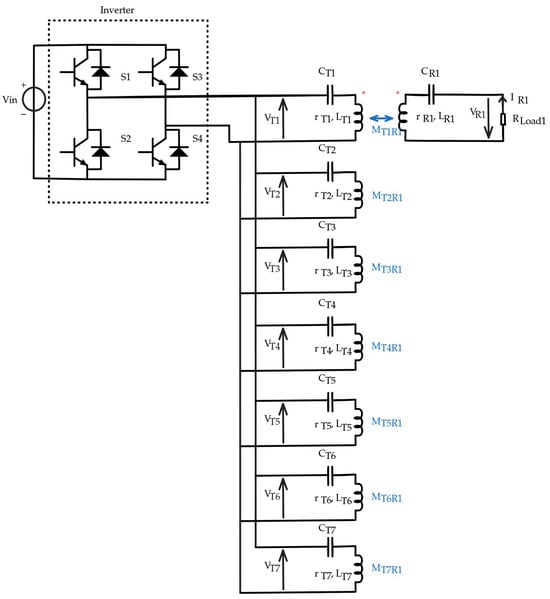

In this article, we have developed an DWPT model for electric vehicles. There are two possibilities for simulation and optimization of the model and its parameters: (1) offline simulation and optimization, and (2) online simulation and optimization (real-time simulation). In this work, the model and its parameters, implemented in MATLAB 2024a Simulink/Simpower as shown in Figure 1, were performed only in offline mode. Real-time optimization and simulation will be investigated and developed in a future work.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of the S–S WPT system. Asterisks (*) denote the dot-convention polarity indicating the relative orientation of the coupled windings.

In modern implementations, DWPT systems are typically designed to operate in the frequency range of 79 kHz to 90 kHz, in accordance with the international standard IEC 61980 [22]. This regulatory framework not only ensures safe electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) but also harmonizes the design of different manufacturers’ systems, paving the way for large-scale interoperability. Studies have shown that operating within this band achieves a balance between efficiency, component size, and reduced electromagnetic interference, making it a practical standard for real-world roadway deployment [20,21].

A particularly important aspect of WPT design is the choice of compensation topology, with the Series–Series (SS) configuration being the most widely studied and implemented in EV applications [23,24]. SS-WPT offers high efficiency, simpler resonance tuning, and improved misalignment tolerance compared with alternative topologies. Because of its central role, the SS-WPT architecture is discussed in detail in its own dedicated section of this work. This work establishes an analytical investigation of multi-transmitter Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer (DWPT) systems based on the Series–Series compensation topology. An n-transmitter/m-receiver model is developed for time-domain analysis under dynamic operating conditions, providing a foundation for systematic performance evaluation. Furthermore, three-dimensional modeling and simulation are conducted to validate the analytical results and offer detailed insights into overall system behavior.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a detailed review of the Series–Series topology and its advantages and limitations in DWPT systems. Section 3 introduces the analytical modeling framework, including both time- and frequency-domain formulations, with extensions to multi-transmitter scenarios. Section 4 outlines the results and discussions, focusing on performance metrics such as efficiency, stability, and transient response. Finally, Section 5 provides the conclusion and identifies future research directions, including control optimization, frequency adaptation, and real-scale experimental validation.

2. Series–Series Resonant WPT: Topology and Performance Analysis

The Series–Series Wireless Power Transfer (SS-WPT) topology has become the most prevalent compensation structure in both static and dynamic EV charging systems due to its simplicity, high efficiency, and robustness [15,23,24,25]. In WPT systems, the compensation network plays a crucial role in achieving impedance matching and reactive power compensation. If the compensation is poorly designed, even with interoperable coils, it can lead to impedance mismatch and reduced active power transfer to the load. Among the commonly used compensation configurations—series (S), parallel (P), and LCC—studies have shown that only the S–S topology can sustain a stable operating frequency despite variations in load, which explains its widespread adoption in wireless charging applications [18].

Nevertheless, one of the major challenges in EV wireless power transfer is the misalignment between transmitter and receiver coils. Such misalignment alters the magnetic coupling coefficient from its nominal value, which in turn affects system efficiency, output power, input phase angle, and input impedance. Therefore, it is essential to design a compensation network that maintains high efficiency and minimizes sensitivity to coupling variations. Although four fundamental topologies—Series–Parallel (S–P), Parallel–Series (P–S), Series–Series (S–S), and Parallel–Parallel (P–P)—are generally considered, most of them are highly sensitive to misalignment. The Series–Series configuration, however, stands out as it maintains a resonant frequency that is largely independent of coupling and load conditions, making it highly suitable for EV wireless charging applications [25].

In this configuration, both the transmitter and receiver resonant circuits employ series compensation capacitors, ensuring that resonance can be achieved at a fixed operating frequency for a specific load and specific coupling coefficient [19,26]. This characteristic makes the SS-WPT topology particularly attractive for Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer (DWPT) systems, where coil misalignment, air gap variation, and load fluctuations are inevitable [12,16].

The fundamental structure of an SS-WPT system, as detailed in numerous works including [12,16], consists of two magnetically coupled coils, each tuned to a common resonant frequency by a series-connected capacitor. The primary side typically includes a high-frequency AC power source, often generated from a DC source via a full-bridge or half-bridge inverter [26], while the secondary side rectifies the received AC power back to DC for battery charging.

The core of its operation, as illustrated in the equivalent circuit of Figure 1, relies on the principle of resonant inductive coupling. The purpose of each primary capacitor is to allow its corresponding transmitter coil to operate at its most effective frequency, the system’s switching frequency , which is typically designed to be at or near the resonant frequencies for , where here . Similarly, the receiver capacitor serves the same purpose for the receiver coil , whose resonant frequency is . This resonant tuning allows currents to build up to high magnitudes in the coils with relatively small input voltages, enabling efficient power transfer across an air gap through the mutual inductances , each defined by the corresponding coupling coefficient as [3,14,27].

A significant analytical advantage of the Series–Series (SS) topology is that its operational principles can be directly derived from the fundamental equations of the magnetically coupled circuit shown in Figure 1. Using Kirchhoff’s voltage law (KVL), the loop equations for the transmitter and receiver sides are established. When the system operates at the angular frequency , which is the actual operating frequency of the system, the KVL equations can be written as:

The following expressions define the circuit parameters and the corresponding reduced variables:

In these equations, represents the excitation voltage, and are the impedances of the primary and secondary loops, is the characteristic impedance of the primary circuit, and are the damping factors, and are the reduced variables of the loop currents, and are the mutual inductances between each transmitter and the receiver. The other terms, including , , , , , , , and , are the corresponding loop currents, self-resistances, self-inductances, and series compensation capacitances.

To simplify the analysis, the original circuit equations are converted into a non-dimensional form. By expressing the variables in a normalized (unit-free) form, the equations become easier to analyze and compare. Specifically, the reduced voltage is defined as , where v is the dipole voltage; the reduced current is defined as , where i is the dipole current; and the reduced power is defined as , where P is the dipole power in watts. This process leads from the initial circuit equations to the reduced set of equations shown below.

where , and .

Additionally, , , and .

This representation clearly shows how the SS-WPT topology enables resonance-based power transfer between the primary and secondary sides. Furthermore, this mathematical framework is essential for analyzing the system’s performance under real-world constraints, such as coil misalignment, which directly affects M and can detune the system, and load variation, which impacts the power transfer profile and efficiency. This foundational modeling is critical for designing robust control strategies to maintain high efficiency across the operating range of an EV wireless charging system [21,28,29].

3. Dynamic Modeling of Wireless Power Transfer Systems

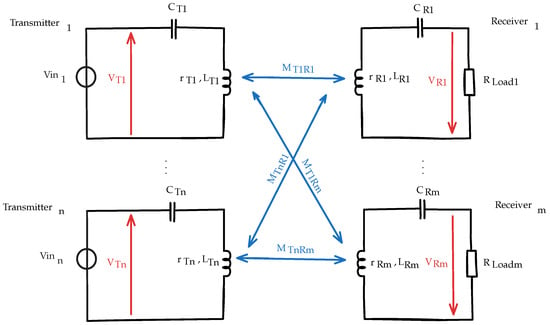

For a system with multiple transmitters and receivers, the voltage across each coil is influenced not only by its own self-impedance but also by the induced voltages from all nearby coils. As illustrated in Figure 2, the analytical model for the DWPT system consists of transmitter coils () with self-inductance and self resistance , each connected in series with a capacitor , and excited by an AC voltage source . Similarly, receiver coils () with self-inductance and self resistance are connected to capacitors , and load resistances . The mutual inductance between transmitter and receiver is denoted by . For a transmitter coil , the KVL equation includes the voltage across its series capacitor , the voltage drop across its self-inductance , the induced voltages from all receiver coils through the mutual inductances , and the resistive voltage drop due to the self resistance . Similarly, each receiver coil experiences voltage contributions from its own tank impedance (including , , and ), the resistive load , and mutual interactions with all transmitting coils through [9,30,31,32]. These coupled relations form a system of linear differential equations that fully describe the dynamic behavior of the DWPT system.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the proposed analytical model.

The analytical model for the DWPT system can be described by the following voltage equations.

- The voltage equation for a transmitter coil i () is:

- Similarly, the voltage equation for a receiver coil j () is:

In the receiver Equation (Equation (14)), the total resistance is now explicitly included as the sum of the coil’s resistance and the load resistance that models the power drawn by the vehicle.

Extending the above coupled equations, the complete dynamic model for a Series–Series compensated WPT system in a configuration—comprising two transmitter coils (, ) and one receiver coil ()—can be expressed in a normalized matrix form. This formulation is a specific case of the general system where transmitters and receiver.

where , , and are the normalized self-inductances of the coils, and the normalized mutual inductances are defined as , , and , and , , and .

The reduced damping and capacitance matrices are defined as:

The complete reduced state-space representation of the resonant circuit is then:

where the normalized input voltage vector is

representing the normalized voltage applied to the transmitter coils.

This reduced matrix representation clearly illustrates how the dynamic 2 × 1 Series–Series Wireless Power Transfer (SS–WPT) configuration enables resonance-based power transfer between the two transmitter coils (, ) and the receiver coil (). By employing normalized inductance, capacitance, and damping matrices, together with the normalized input voltage vector , the model compactly captures the coupled dynamics of the system and serves as a foundation for analyzing multi-transmitter Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer (DWPT) architectures. This matrix-based framework enables evaluation of performance under practical conditions such as coil misalignment—affecting the mutual inductances and —and load variations, which modify the power transfer profile and overall efficiency. The eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the reduced state-space matrix are computed to characterize the transient and steady-state behavior, from which coil currents, voltages, output power, and overall transfer efficiency are obtained under varying operating conditions. This frequency-domain formulation is indispensable for analyzing resonance conditions, determining power transfer efficiency, and designing robust control strategies that maintain high efficiency across the dynamic operating range of electric vehicle wireless charging systems [21,28,29].

One of the key complexities in DWPT modeling is the time-varying nature of mutual inductance as vehicles move along the charging track. The coupling coefficient k is no longer a fixed parameter but changes with the vehicle’s lateral and longitudinal position, air gap variations, and coil misalignment [27,33,34,35]. Analytical frameworks have been extended to incorporate this dynamic coupling, often through the introduction of position-dependent mutual inductance matrices. These models allow engineers to predict how variations in alignment and speed affect the instantaneous power transfer and the efficiency of the system.

In this study, two cases were considered: one including mutual inductance between the transmitter coils and one neglecting it. The results showed that the presence of mutual inductance between transmitters had a negligible effect on the overall system behavior, as further discussed in Section 5.5.

Another critical aspect is the development of control-oriented reduced-order models that simplify the full multi-coil system for real-time implementation. These models condense the complex network of coils into an equivalent system that captures the dominant dynamics while reducing computational load, enabling real-time adaptive control for power delivery, resonance tracking, and misalignment compensation [36,37]. Such reduced-order formulations are particularly important when designing vehicle-side controllers that must respond to fast changes in coupling and load without causing instability or excessive power losses.

The analytical model supports both time-domain and frequency-domain analyses. In the time domain, it enables the study of transient responses during transmitter switching and the behavior of resonant tanks under time-varying excitations [24,38]. In the frequency domain, it aids in identifying optimal operating points, estimating power transfer efficiency, and assessing the stability margins of the system.

The model has also been extended to simulate the simultaneous contribution of multiple transmitters, a more advanced and realistic scenario for DWPT. Here, the power received by the vehicle is a superposition of contributions from nearby active coils, each with its own phase, amplitude, and mutual coupling profile. Accurate representation of this scenario requires solving the resulting coupled matrix Equations [30,39].

Overall, the analytical model provides a critical tool for system-level optimization, real-time control, and transition to embedded controller implementation. It allows engineers to simulate a wide range of scenarios, verify controller performance, and ensure that the DWPT system can operate reliably under varying environmental and operational conditions [9,13].

4. System Configuration and Operational Modes

The design of a Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer (DWPT) system is a complex integration of multiple interdependent electrical and control subsystems, which must be carefully co-designed to ensure safe, efficient, and continuous energy transfer to moving electric vehicles [12,40]. Unlike static Wireless Power Transfer (WPT), DWPT has to deal with time-varying coupling, rapid transients, and the logistical challenge of energizing a moving target, necessitating a full design approach.

At its core, the DWPT system comprises a primary (transmitter) subsystem embedded in the road infrastructure and a secondary (receiver) subsystem mounted on the vehicle underbody [8,21]. The primary subsystem consists of an array of transmitter (Tx) coils, often constructed with Litz wire to minimize AC resistance [41].

The fundamental challenge in DWPT design stems from the vehicle’s motion, which causes continuous and often unpredictable variation in the mutual inductance (M) and coupling coefficient (k) between the transmitter and receiver coils [3,4,14,16]. This variation directly impacts the reflected impedance seen by the inverter, leading to fluctuations in power transfer capability and potential deviation from the optimal resonant point.

System Architecture

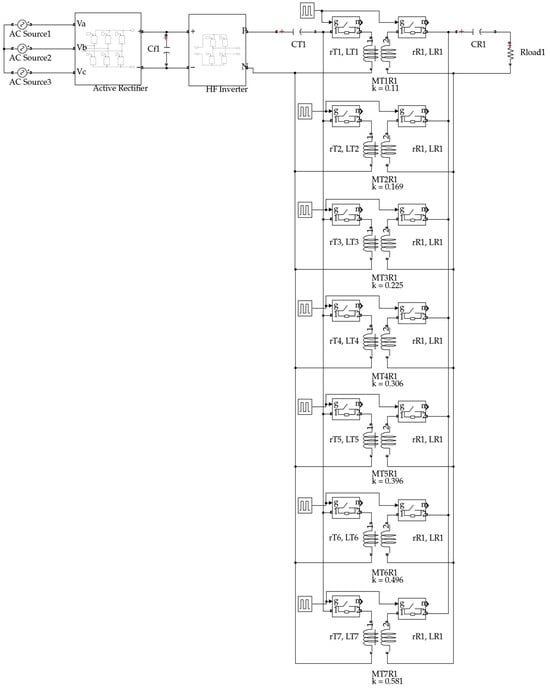

The complete DWPT system operates as a multi-stage power conversion chain, beginning with the three-phase grid supply and ending with the vehicle’s battery, as illustrated in Figure 3. Conceptually, the system includes an AC/DC rectifier with a filter stage that generates a stable high-voltage DC bus (around 600 V). This bus supplies the resonant transmitter subsystem embedded in the roadway. On the vehicle side, the resonant receiver coil captures the transmitted energy, which in practice is processed by a rectifier and filter before reaching the battery pack, but in the analytical model this stage is represented by an equivalent load resistance on the secondary side.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the proposed model.

A key practical consideration in this architecture is the large voltage step-down required between the roadway DC bus and the vehicle battery; while the infrastructure typically operates at about 600 V, many electric vehicles—particularly those using low-voltage platforms—require only 48–50 V at the battery. Achieving this conversion solely through the coil turns ratio would demand an excessively high ratio, which would introduce losses and create design challenges. In practice, an isolated DC/DC converter is usually employed to handle this voltage adaptation efficiently [13].

However, the central focus of this work is the resonant wireless power transfer subsystem itself, which forms the core of the DWPT energy link. Converter design and optimization, although important, remain outside the scope of this paper.

The following section develops the mathematical models and simulation framework used to evaluate the DWPT configurations introduced previously. Starting from the equivalent circuit representation of the resonant link, we derive the governing equations that capture the time-varying mutual inductance, coil parameters, and power electronic interfaces. These models are then implemented in a simulation environment to assess system behavior under different operating conditions, forming the basis for the performance results presented in the subsequent subsections. In our schematic diagram of the proposed model, we consider seven transmitters interacting with only a single receiver.

5. Modeling and Simulation

This section builds upon the previously introduced modeling framework by providing a comprehensive description of the Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer (DWPT) system representation and the methodology employed for its numerical analysis. The primary objective is to convert the conceptual architecture of the DWPT system into a rigorous set of mathematical equations and parameters that accurately characterize energy transfer as the vehicle moves over the transmitter array. The model serves as a predictive tool for evaluating system performance, optimizing design parameters, and identifying potential limitations before experimental implementation.

The modeling process begins with a detailed formulation of the equivalent circuit parameters, including self-inductances, mutual inductances, resonant capacitances, and coil resistances. These parameters are selected to accurately capture the electromagnetic interactions between the transmitter and receiver coils, which are central to the resonant power transfer mechanism. Mutual inductance is treated as a position-dependent quantity to represent the continuous variation in coupling as the vehicle moves over the transmitter coils, enabling realistic modeling of dynamic charging scenarios. In addition, damping effects and load characteristics are incorporated to account for energy dissipation, impedance mismatches, and variations in the connected electrical load.

These physical relationships are then systematically translated into a set of coupled differential equations describing the temporal evolution of currents and voltages in both the transmitter and receiver coils. The equations are expressed in a state-space form to facilitate numerical solution and allow for eigenvalue-based analysis of system stability, resonant modes, and power transfer dynamics. The model is further extended to include multi-coil and multi-transmitter configurations, which introduce additional interactions and cross-coupling effects, providing a more realistic representation of advanced DWPT architectures.

Once formulated, the complete system model is implemented in a simulation environment to evaluate both steady-state and transient responses under different operating scenarios. Simulations are conducted across three representative configurations: (1) a dynamic baseline configuration with a single transmitter and receiver, serving as a reference; (2) sequential transmitter activation and (3) multi-transmitter operation. Each configuration presents distinct trade-offs in efficiency, complexity, cost, and robustness, which are systematically examined through model-based simulation.

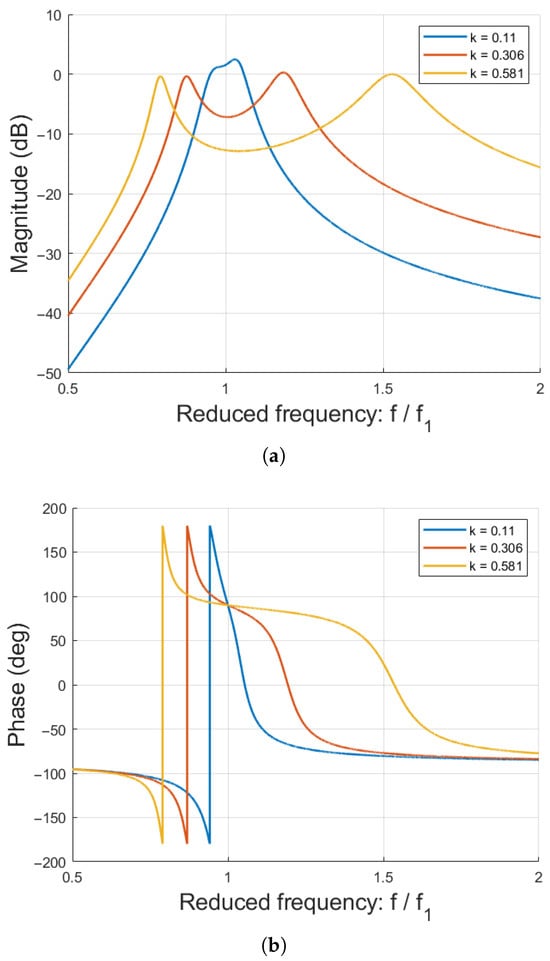

5.1. Frequency-Domain Validation

To complement the time-domain analysis, the frequency response of the Series–Series compensated WPT system is examined using the Bode diagram shown in Figure 4, which is derived from the analytical model established in Section 2. The magnitude response, shown in Figure 4a, and the phase response, shown in Figure 4b, are traced with respect to the reduced frequency , where the reference frequency corresponds to the resonant frequency of transmitter 1 and is defined as

with and . This representation clearly identifies the resonant frequency and bandwidth of the system, providing a direct means of validating the modeled parameters obtained from the laboratory benchmark and confirming the expected resonant behavior prior to dynamic simulation.

Figure 4.

Bode diagram of the Series–Series compensated WPT system: (a) Magnitude response vs. Reduced frequency. (b) Phase response vs. Reduced frequency.

5.2. Simulation Parameters

In dynamic wireless charging scenarios, the longitudinal displacement of the vehicle during motion should be considered. For an inverter operating frequency in the range of 50–, the distance required for the system to reach steady state (with a maximum of 100 periods) depends on both the vehicle speed and the operating frequency. At a speed of , this distance ranges from to , whereas at , it ranges from to . Accurate consideration of these displacement intervals is essential for modeling the spatial–temporal evolution of the coupling during dynamic operation.

The coupling coefficient k is highly sensitive to both vertical separation and lateral misalignment between the transmitter and receiver coils. Earlier studies in this research line [16] have shown that for a vertical gap of with perfect alignment, the coupling reaches approximately , whereas a lateral misalignment of under the same spacing reduces it to about . At a larger vertical distance of , the coupling decreases to around for perfect alignment and further to roughly with a misalignment. The main simulation parameters used for modeling the dynamic wireless power transfer system are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Simulation parameters for the dynamic wireless power transfer system.

Using these published results as a basis [4,16], a coupling-coefficient distribution was constructed to represent the continuous variation of k as a function of lateral misalignment over the range . As illustrated in Section 5.6, this distribution is approximated analytically through a Gaussian-based model. The resulting formulation yields a smooth coupling profile along the receiver’s path and is subsequently used to evaluate dynamic power-transfer performance in simulation.

5.3. Dynamic Configuration Results

The analytical and simulation framework for any complex Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer (DWPT) system must be built upon a thorough understanding of its dynamic behavior. In this study, the system was initially evaluated using a 1 × 1 (one transmitter–one receiver) configuration, providing critical insights into resonance tuning, efficiency curves, and transient responses, forming the foundation for more complex dynamic analyses.

This simplified model, illustrated in Figure 1, isolates the core physics of resonant inductive coupling by eliminating the complexities introduced by multiple transmitters, movement, and complex switching logic.

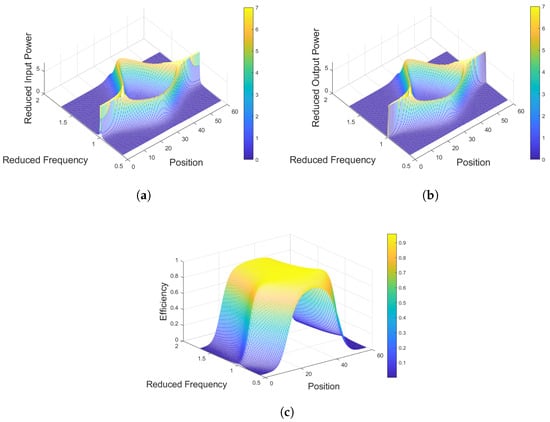

The simulation results for the dynamic 1 × 1 configuration, detailed in Figure 5, provide a comprehensive overview of the system’s power behavior under resonant conditions. Figure 5a illustrates the reduced input power drawn from the DC source, showing its stability and the minimal fluctuations under steady-state operation, which is characteristic of a well-tuned resonant system. Figure 5b depicts the reduced output power transferred to the load, demonstrating the effective power transfer capability of the coupled coils, with the magnitude directly reflecting the strength of the magnetic coupling and the efficiency of the compensation topology. Finally, Figure 5c charts the overall power transfer efficiency, calculated as the ratio of output to input power, highlighting the peak performance achievable at the designed resonant point and providing a critical baseline for evaluating losses and optimizing the system before introducing dynamic complexities. Together, these figures quantify the core power metrics—input, output, and efficiency—that are essential for validating the fundamental design and operational readiness of the WPT system. In addition, the reduced output power is defined as , where the reference power , with representing the excitation voltage and denoting the characteristic impedance of the primary circuit, yielding ; similarly, the reduced input power is defined as .

Figure 5.

Simulation results for the dynamic baseline configuration: (a) Reduced input power vs. position and Reduced frequency. (b) Reduced output power vs. position and Reduced frequency. (c) Power transfer efficiency vs. position and Reduced frequency.

5.4. Sequential Transmitter Results

Building on the dynamic model, a key design element for practical Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer (DWPT) is the transmitter arrangement and activation strategy. In this work, we consider a 2 × 1 configuration with two transmitters and one receiver, which allows the study of interactions between multiple active coils and the receiver dynamics. This setup also provides insight into the effects of coil positioning and dynamic movement on power transfer efficiency.

The sequential transmitter strategy activates only the transmitter closest to the receiver at any time, offering simplicity and efficiency. By doing so, it eliminates two major sources of energy loss, (1) circulating currents in idle transmitters, and (2) inter-coil interference, since deactivating adjacent transmitters prevents mutual coupling that can reduce overall system efficiency. While this approach enables near-optimal performance when the receiver is well-aligned, it introduces a risk of power discontinuities during handover, requiring precise switch-off/switch-on control as the receiver moves between transmitters. This limitation highlights the trade-off between simplicity and dynamic performance in practical DWPT systems.

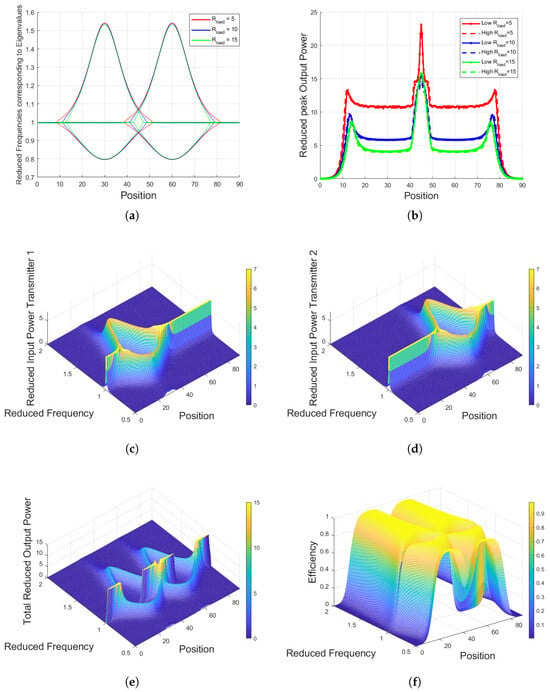

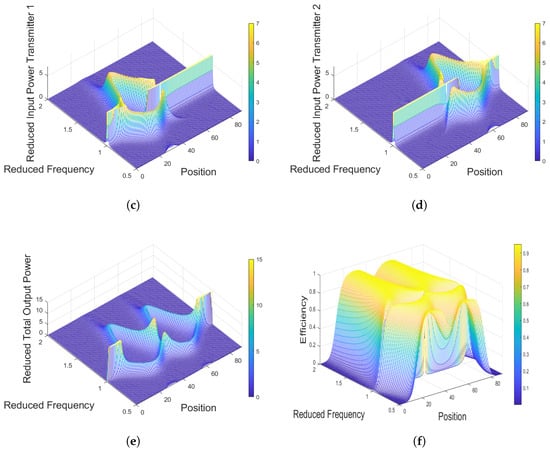

The results of the sequential transmitter activation scheme are presented in Figure 6, illustrating the system response as the receiver moves along the track. To better understand the dynamics of the sequential transmitter system, an eigenfrequency analysis was performed. Figure 6a shows the eigenvalues of the system matrix for different values of , which represent the resonant modes of the two-transmitter, one-receiver configuration. The system eigenvalues are represented in the form , where denotes the damping factor and denotes the angular oscillation frequency, as shown in Figure 6a. The corresponding eigenvector shows how the transmitter current and the compensation voltage are distributed. It is observed that the eigenvalues are slightly shifted when is varied, although the overall mode structure remains largely unchanged. This analysis allows the coupled system to be viewed as a set of independent single-input–single-output subsystems, highlighting the modes that contribute most to power delivery. Figure 6b presents the reduced peak output power as a function of receiver position for different values. This figure illustrates how the power transferred to the load varies across the track under different load values. The comparison highlights the influence of on the reduced peak output power achievable at different positions, providing insight into the performance limits of the sequential transmitter strategy.

Figure 6.

Sequential transmitter activation and new analysis results: (a) Eigenvalues of the system matrix for different values. (b) Reduced peak output power as a function of receiver position for different values. Sequential transmitter activation strategy results: (c) Reduced input power to first transmitter. (d) Reduced input power to second transmitter. (e) Total reduced output power trasnferred to the load. (f) Overall system efficiency.

For the following analysis, the reduced input power, reduced output power, and overall efficiency of the system are computed for a load resistance of . Figure 6c,d show the reduced input power distributions for the first and second transmitters, respectively. As expected, each transmitter dominates within its local coupling region, with only one coil actively supplying power at a time. This selective activation effectively suppresses parasitic losses and prevents unnecessary energy circulation in idle transmitters, highlighting the inherent efficiency advantage of the sequential strategy.

Figure 6e presents the total reduced output power transferred to the load during the transition between transmitters. The overall power envelope follows the coupling profile predicted by the dynamic model; however, distinct behavior emerges near the boundary where the fields of the two transmitters overlap. In this region, when both coils are partially active around the resonant frequency, noticeable power peaks appear due to constructive magnetic coupling, which temporarily enhances the power transferred to the receiver.

Despite this local increase in power, Figure 6f shows that the corresponding efficiency at these points is reduced. The system exhibits high instantaneous power but lower energy conversion efficiency, making these regions less practical for sustained operation.

Overall, the sequential activation strategy is simple and reduces cross-coupling losses, but its performance is limited near the transmitter switching region by power discontinuities and less efficient resonance. These limitations motivate the adoption of simultaneous multi-transmitter activation, which can provide smoother and more consistent power delivery.

5.5. Multi-Transmitter System Analysis

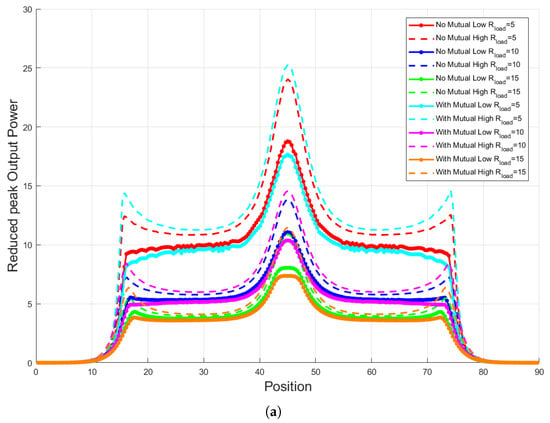

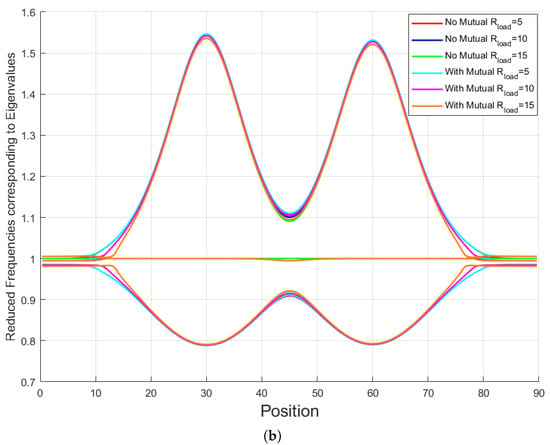

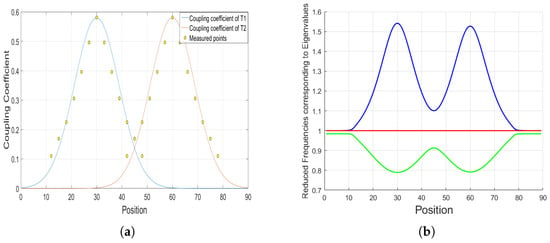

In order to investigate the influence of multiple transmitters on the DWPT system, a detailed analysis was conducted considering different values of the load resistance and the presence or absence of mutual inductance between the transmitter coils. Two specific cases were examined: (i) including mutual inductance between transmitters, and (ii) neglecting mutual inductance. The corresponding mutual inductance values were obtained in accordance with previously reported studies in this research line [16]. Figure 7a shows the reduced peak output power as a function of receiver position for the two cases and for varying values. As can be observed from the curves, the inclusion of mutual inductance between transmitters had a negligible effect on the output power for the same load resistance. Similarly, Figure 7b presents the reduced frequencies corresponding to the eigenvalues of the state-space matrix as a function of position. The comparison indicates that while the eigenfrequencies are slightly shifted when including mutual inductance, the overall impact remains minor. These results indicate that, for the configurations considered, the interaction between transmitters does not significantly alter the system behavior.

Figure 7.

Analysis of the multi-transmitter DWPT system for different values: (a) Reduced peak output power as a function of receiver position for cases with and without mutual inductance; (b) Reduced eigenfrequencies corresponding to the system eigenvalues as a function of receiver position.

5.6. Multi-Transmitter Results

The simultaneous multi-transmitter activation strategy is introduced to overcome the limitations associated with sequential activation. In the sequential approach, only one transmitter is active at a time, and when the active transmitter is switched, the system experiences temporary discontinuities in power transfer. These discontinuities manifest as fluctuations in the input and output power profiles, leading to efficiency variations and potential instability at the load. By contrast, in the simultaneous configuration, multiple neighboring transmitters are activated simultaneously, and each contributes a fraction of the total transmitted power. This continuous operation ensures that the receiver coil consistently couples with more than one transmitter, producing a smoother and more continuous power profile.

The advantages of this approach are evident in the three-dimensional power profile shown in Figure 8. Having established that the mutual inductance between transmitters has only a minor effect, the subsequent analysis focuses on the multi-transmitter system with while neglecting mutual interactions. Figure 8a presents the coupling coefficient as a function of position for two transmitters, illustrating fitted curves based on seven representative coupling values corresponding to different misalignment scenarios. The individual data points used for the fitting are also indicated in figure [4,16]. To further understand the underlying dynamics governing power transfer, an eigenfrequency analysis of the system model was performed. In this context, the eigenvalues of the system matrix represent its resonant modes. Physically, each eigenvalue corresponds to a resonant frequency at which the system can efficiently transfer power, while the associated eigenvector describes the current distribution, or “mode shape,” across the transmitter coils. This analysis enables a transformation from the original coupled system to a set of decoupled single-input–single-output systems, where each system’s optimal resonant frequency is determined by its eigenvalue. Figure 8b illustrates the evolution of these eigenvalues with respect to the receiver position. In our analysis, the eigenvalue equal to 1 is excluded. This mode corresponds to a weak or ineffective resonant condition and leads to very low output power over most positions. Although it may exhibit higher power at certain edge positions where the coupling becomes small, the efficiency in these regions remains extremely low, making the mode unsuitable for practical wireless power transfer. Therefore, only the remaining eigenvalues are considered, as they represent the physically meaningful resonant modes that contribute significantly to power transfer and are essential for optimizing system performance. Figure 8c,d show the reduced input power contribution from each transmitter as a function of reduced frequency and position. Unlike the sharp discontinuities observed in sequential activation, the input power surfaces here remain continuous, indicating that both transmitters maintain active participation across the operating range. This translates to a more uniform power flow to the receiver, which is particularly beneficial for dynamic wireless power transfer (DWPT), where vehicle misalignment and varying coupling conditions are inevitable.

Figure 8.

Simulation results for multi-transmitter activation strategy: (a) Coupling coefficient variation along the vehicle position for two transmitters. (b) Eigenvalues with respect to position. (c) Reduced input power to first transmitter. (d) Reduced input power to second transmitter. (e) Total reduced output power transferred to load. (f) Overall system efficiency.

The resulting effect on the load is evident in Figure 8e, where the output power profile demonstrates smoother variation and higher stability compared with sequential operation. Rather than experiencing dips during the transition between transmitters, the simultaneous strategy provides overlapping contributions that reinforce each other, thus reducing sensitivity to spatial boundaries between transmitters. Similarly, Figure 8f illustrates the efficiency map, which remains relatively flat and robust over a wide range of frequencies and coupling values. This robustness is a clear improvement over sequential activation, where efficiency can degrade significantly during switching intervals.

Beyond smoother power delivery and improved efficiency, the simultaneous activation approach inherently offers fault tolerance. Since multiple transmitters operate together, the system retains redundancy: if one transmitter fails or operates below capacity, the others can still deliver partial power, reducing the risk of total power interruption. However, this advantage comes at the expense of added complexity. Synchronizing multiple resonant transmitters requires precise phase alignment and current balancing to avoid destructive interference or unwanted circulating currents. The control and power electronics architecture is therefore more sophisticated, and additional measures may be required to ensure electromagnetic compatibility.

Despite the increased implementation complexity, its benefits make it a strong candidate for practical deployment in dynamic wireless power transfer systems.

6. Discussion

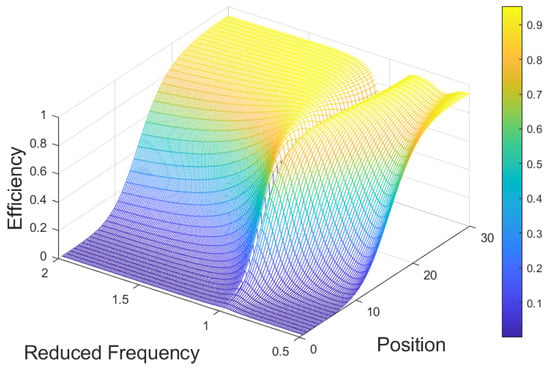

In most wireless power transfer studies, analysis is typically limited to conventional configurations, providing only a partial view of system behavior under dynamic conditions. In contrast, this work presents a generalized modeling framework capable of representing , , and fully scalable DWPT architectures. By considering receiver position and multi-transmitter interactions, the proposed tool accurately captures power transfer variations across different configurations. Additionally, a 3D representation of transmitted power as a function of reduced frequency and receiver position has been developed, enabling clear visualization of resonance behavior and power distribution. Future work will focus on experimental validation for dynamic systems and extending the methodology to a wider range of operating conditions, including coupling values (), to enhance applicability to larger coil separations and more demanding alignment scenarios.

A complementary analysis is presented in Figure 9, showing system efficiency as a function of reduced frequency and receiver position within the range 0–30. This investigation illustrates how efficiency varies with both reduced frequency and position, highlighting the operating conditions that maximize power transfer. As the receiver moves along the track, the optimal frequency for maximum efficiency shifts accordingly, providing insights into the dynamic behavior of the system.

Figure 9.

Efficiency map as a function of reduced frequency and receiver position (0–30).

7. Conclusions

This work has presented a comprehensive study of Series–Series resonant wireless power transfer (SS-WPT) systems in the context of Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer (DWPT) for electric vehicles. Beginning with the dynamic baseline configuration, the analysis established the fundamental behavior of resonant inductive coupling, highlighting how resonance tuning, coil alignment, and compensation topology directly influence input power, output power, and efficiency. These insights provided the foundation for evaluating more complex dynamic scenarios where vehicle motion introduces time-varying mutual inductance and coupling coefficients.

Building upon this foundation, two key operational strategies were examined: sequential transmitter activation and simultaneous multi-transmitter activation. The sequential approach, while simple and efficient under ideal alignment, was shown to suffer from inevitable discontinuities in power transfer during switching events, reducing robustness and efficiency under dynamic conditions. In contrast, the simultaneous multi-transmitter strategy effectively mitigated these issues by enabling overlapping contributions from multiple transmitters, producing smoother power delivery and more stable efficiency characteristics. While all transmitter activation in this study was conducted within the simulation environment without real-time control, the development of fully automated mechanisms capable of dynamically detecting vehicle position and optimally energizing the corresponding transmitter coils remains an important objective for future research.

The analytical modeling framework developed in this study has served as the backbone for evaluating different DWPT operating modes. By formulating coupled voltage equations for both transmitters and receivers, the model captured the essential interactions of resonant inductive systems under static and dynamic conditions. This allowed for precise comparison between sequential and simultaneous activation strategies, revealing how time-varying mutual inductance and coil coupling directly shape input power, output power, and efficiency profiles.

Looking ahead, future research should focus on refining multi-transmitter synchronization strategies, optimizing control methods with explicit performance objectives such as maximizing transferred power and maintaining efficiency under variable coupling, and validating these insights through real-world prototypes. In addition, further investigation is needed for low-coupling conditions, particularly when the coupling coefficient k drops below 0.11. Understanding system performance and control strategies under such extreme misalignment scenarios will be essential for ensuring robust power delivery across the full range of practical vehicle positions. Addressing these challenges will be critical to enabling reliable, efficient, and interoperable DWPT infrastructure capable of supporting the next generation of electric mobility.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to this work. Conceptualization, A.R., and K.E.K.D.; Methodology, A.R.; Software, A.R.; Validation, A.R.; Formal analysis, A.R.; Investigation, A.R.; Resources, A.R., K.E.K.D., C.P. and K.T.; Data curation, A.R.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.R.; Writing—review and editing, A.R., K.E.K.D., C.P. and K.T.; Visualization, A.R.; Supervision, K.E.K.D., C.P. and K.T.; Project administration, K.E.K.D., C.P. and K.T.; Funding acquisition, K.E.K.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Clermont Auvergne Métropole in collaboration with L’Académie des Mobilités Durables (EOTP: 24CD05ORBIMO) and supported by the International Research Center “Innovation Transportation and Production Systems” of the I-SITE CAP 20-25.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DWPT | Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| SS-WPT | Series–Series Wireless Power Transfer |

| RLC | Resistor–Inductor–Capacitor |

| KVL | Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law |

References

- Nakutis, Ž.; Lukočius, R.; Girdenis, V.; Kroičs, K. A Measurement Method of Power Transferred to an Electric Vehicle Using Wireless Charging. Sensors 2023, 23, 9636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozhi, M.; Mohamed, M.; Gilani, V.N.M.; Amjad, A.; Majid, M.S.; Yahya, K.; Salem, M. A Review of Wireless Pavement System Based on the Inductive Power Transfer in Electric Vehicles. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xiong, X.; Ren, L.; Kong, P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J. Design and Optimization of Quasi-Constant Coupling Coefficients for Superimposed Dislocation Coil Structures for Dynamic Wireless Charging of Electric Vehicles. Prog. Electromagn. Res. M 2023, 116, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Drissi, K.E.K.; Pasquier, C. Frequency Domain Analysis of a Dynamic Wireless Transfer System for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 72777–72793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, A.; Kashyap, A.; Nasab, M.A.; Padmanaban, S.; Bertoluzzo, M.; Kumar, A.; Blaabjerg, F. A Comprehensive Review of the Recent Development of Wireless Power Transfer Technologies for Electric Vehicle Charging Systems. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 83703–83751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wu, C.; Chen, T. Efficiency Improvement for Wireless Power Transfer System via a Nonlinear Resistance Matching Network. Electronics 2023, 12, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Feng, F.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Xie, P. Power Stability Enhancement in Inductive Wireless Power Transfer Systems: A Review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 145968–145987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, A.; Amin, A.A.; Ahmad, M.; Shafique, M.F.; Zafar, M.S. Wireless Power Transfer for Deep Cycle Lithium-Ion Batteries in Electric Vehicles Using Inductive Coupling. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2024, 16, 16878132241289766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noeren, J.; Elbracht, L.; Parspour, N.; Wörner, M.; Spindler, M. An Easily Scalable Dynamic WPT System for EVs. In Proceedings of the 2022 Wireless Power Week (WPW), Bordeaux, France, 5–8 July 2022; pp. 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnamfar, M.; Olowu, T.O.; Tariq, M.; Sarwat, A. Comprehensive Review on Power Pulsation in Dynamic Wireless Charging of Electric Vehicles. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 66858–66882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep, N.T.; Hiep, T.D.; Trung, N.K. Constant Current Charging and Transfer Efficiency Improvements for a Dynamic Wireless Charging System. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2023, 13, 12320–12326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensetti, M.; Kadem, K.; Pei, Y.; Le Bihan, Y.; Labouré, E.; Pichon, L. Parametric Optimization of Ferrite Structure Used for Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer for 3 kW Electric Vehicle. Energies 2023, 16, 5439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubiak, K.; Liang, J.; Cipcigan, L.; Li, C.; Wu, J. Simplified Modelling Techniques for Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer. Electronics 2024, 13, 4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Luo, D.; Li, Z.; Yu, F. Coupling Coefficient Calculation and Optimization of Positive Rectangular Series Coils in Wireless Power Transfer Systems. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.; Song, B.; Shangguan, X.; Liu, H. Optimal Design of Transmission Characteristics for Hexagonal Coil Wireless Power Transfer System Based on Genetic Algorithm. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 2023, 9, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Drissi, K.E.K.; Pasquier, C. Self- and Mutual-Inductance Cross-Validation of Multi-Turn, Multi-Layer Square Coils for Dynamic Wireless Charging of Electric Vehicles. Energies 2023, 16, 7033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, V.; Pakhaliuk, B.; Husev, O.; Vinnikov, D.; Strzelecki, R. Wireless Charging Station Design for Electric Scooters: Case Study Analysis. Energies 2024, 17, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassioui, A.; El Ancary, M.; El Idrissi, Z.; El Fadil, H.; Rachid, K.; Rachid, A. Primary-Side Indirect Control of the Battery Charging Current in a Wireless Power Transfer Charger Using Adaptive Hill-Climbing Control Technique. Processes 2024, 12, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, M.; Farooq-i-Azam, M.; Ni, Q.; Dong, M.; Ansari, E.A. Wireless Charging Systems for Electric Vehicles. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanawa, K.; Imura, T.; Hori, Y.; Mashito, H.; Abe, N. Proposal of Coil Embedding Method in Asphalt Road Surface for Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Wireless Power Technology Conference and Expo (WPTCE), San Diego, CA, USA, 4–8 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özüpak, Y. Analysis and Experimental Verification of Efficiency Parameters Affecting Inductively Coupled Wireless Power Transfer Systems. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IEC 61980-3:2022; Electric Vehicle Wireless Power Transfer (WPT) Systems—Part 3: Specific Requirements for the Magnetic Field Wireless Power Transfer Systems. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- He, L.; Wang, X.; Lee, C.-K. A Study and Implementation of Inductive Power Transfer System Using Hybrid Control Strategy for CC-CV Battery Charging. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, C. Mutual Inductance Estimation of SS-IPT System through Time-Domain Modeling and Nonlinear Least Squares. Energies 2024, 17, 3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnamfar, M.; Tariq, M.; Sarwat, A.I. Novel Autonomous Self-Aligning Wireless Power Transfer for Improving Misalignment. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 56356–56367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, K.; Fang, J.; Tang, Y. Pulse Density Modulated ZVS Full-Bridge Converters for Wireless Power Transfer Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, V.-B.; Ramezani, A.; Triviño, A.; González-González, J.M.; Kadandani, N.B.; Dahidah, M.; Pickert, V.; Narimani, M.; Aguado, J. Operation of Inductive Charging Systems under Misalignment Conditions: A Review for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Transport. Electrific. 2023, 9, 1857–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X. Analysis of Transmission Performance on Wireless Power Transfer System with Metamaterial. Int. J. Microw. Wireless Technol. 2023, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobuchi, D.; Morikawa, H.; Narusue, Y. Automatic Design of Transmitter and Receiver Coils for Wireless Power Transfer Systems by Using Current Distribution Analysis. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 49987–49996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, D. Adaptive Impedance Matching Scheme for Magnetic MIMO Wireless Power Transfer System. Electronics 2021, 10, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Dai, Z.; Yang, Y. A Single-Transmitter Multi-Receiver Wireless Power Transfer System with High Coil Misalignment Tolerance and Variable Power Allocation Ratios. Electronics 2024, 13, 3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Lai, X.; Ma, D.; Tang, H.; Hashmi, K.; Xu, J. Management of Multiple-Transmitter Multiple-Receiver Wireless Power Transfer Systems Using Improved Current Distribution Control Strategy. Electronics 2019, 8, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Shang, J.; Yuan, Z.; Song, M.; Li, C.; Fu, P.; Hao, Z.; Yang, Y.; Hu, A. A New Hybrid Magnetic Coupler in Inductive Power Transfer System for High Misalignment Tolerance. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 72187–72198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abderrazak, F.; Antonino-Daviu, E.; Talbi, L.; Ferrando-Bataller, M. Characteristic Modes Analyses for Misalignment in Wireless Power Transfer System. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 65007–65023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Ma, X.; Wang, R.; Xue, M.; Zhang, P. A Misalignment Tolerate Integrated S-S-S-Compensated WPT System with Constant Current Output. Energies 2023, 16, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, H.; Meira, Z.; Kadem, K.; Damm, G. Modeling and Control of Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer System for Electric Vehicle Charger Application. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2023, 56, 10045–10050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngini, M.A.; Truong, C.-T.; Choi, S.-J. Parameter Identification for Primary-Side Control of Inductive Wireless Power Transfer Systems: A Review. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 15885–15904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, T.; Lyu, S.; Gao, G.; Lei, W. Discrete-Time Modelling and Stability Analysis of Wireless Power Transfer System. IET Power Electron. 2021, 14, 2260–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, R. A Three-Coil Constant Output Wireless Power Transfer System Based on Parity–Time Symmetry Theory. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campi, T.; Cruciani, S.; Maradei, F.; Feliziani, M. Magnetic Field Mitigation in Dynamic Wireless Power Transfer Systems by Double Sided LCC Compensation. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 109750–109758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, D.; Klaus, B.; Leibfried, T. Litz Wire Design for Wireless Power Transfer Coils. In Proceedings of the IEEE PELS Workshop on Emerging Technologies: Wireless Power Transfer (WoW), Taipei, Taiwan, 10–12 May 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).