Abstract

Aquaculture industry is a major contributor to the world’s food supply and therefore provides food security globally. However, many problems exist for the development of the industry; they include poor disease control, lack of sufficient workers, and inefficient use of resources. The advent of big data and Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies presents an opportunity for the aquaculture industry to utilize these technologies to improve operational practices in the entire industry. A proposed framework for a decision-making support system, utilizing a multi-source data hub will be established to enhance current operational practices in aquaculture. This framework will be designed to collect and integrate multiple types of big data from aquaculture (environmental data, trading data, and data from Internet sources), and then create a common platform for accessing and processing the collected data. Four main modules will be created: monitoring environmental factors for shrimp farming, sharing shrimp farming equipment, calculating costs/profits associated with shrimp farming, and predicting price changes. Experimental prototypes of web-based systems will be built and tested to evaluate their performance. Ultimately, the proposed framework will provide users with a user-friendly platform to access the analysis results and recommendations provided to support decisions made during shrimp aquaculture production. Therefore, our work will serve as a reference point for the adoption of leading-edge technologies into aquaculture production management and contribute to sustainable growth of the aquaculture industry.

1. Introduction

Aquaculture industry plays a crucial role in the global food supply by ensuring food security worldwide. Farmers can monitor environmental parameters, predict risks, and optimize production processes in real time, therefore improving productivity through the application of technology [1]. The rise in big data and Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology presents a promising opportunity to transform the whole industry. They enable the gathering and storage of a vast amount of aquaculture information from various sources [2]. Internet of Things (IoT) technologies can gather information about the environment and improve monitoring [3]. Big data and AI can transform this raw data into useful information and actionable suggestions simultaneously. This can help the aquaculture industry improve its production and management processes [2]. In this situation, decision-making support frameworks are needed and are getting a lot of attention. These systems are combined data from various sources, analyzing informative results and providing predictive models or suggestions to support farmers’ decisions [4]. In aquaculture, many decision support systems overlook aspects important to more than one stakeholder group [5]. Additionally, these systems rarely utilize real-time analytics. Another problem is that people involved in aquaculture cannot use and reuse these systems because they lack the technical skills, financial resources, or infrastructure necessary to do so. Lacking knowledge of Information Technology (IT) can hinder the effective use of decision-making support frameworks, resulting in advanced technologies not being utilized to their full potential. For these systems to benefit stakeholders, particularly farmers, more technical work and support are needed to create solutions that are flexible and easily accessible.

Our paper aims to address these gaps in the field of smart aquaculture, adopting big data and AI technologies. First, multiple data sources from aquaculture farming (e.g., farm environmental data, animal health data, satellite data, market data, operational data) are separated and fragmented. The lack of data-integrated systems entails difficulties. To address this issue, the paper proposes an integrated framework that facilitates the connection and analysis of various data streams, which have not been thoroughly explored in prior research. Second, there are distances between data and decisions, particularly in aquaculture domain. The lack of effective applications that transform raw data into valuable information and actionable insights remains a key limitation. We will develop a decision-making support framework to narrow this gap and provide informed decisions. There are four different use cases, including monitoring farm environment, sharing farm equipment data, calculating costs/profits, and predicting prices. This framework is hoped to optimize aquaculture operation practices. The framework is designed to gather, combine, and analyze a wide range of aquaculture big data. Next, we establish a central data sharing hub for sharing and processing various data streams. The research objectives include the following:

Objective 1. Develop an integrated data framework for supporting aquaculture decisions.

Objective 2. Develop an experimental prototype and assess its performance.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we present an overview of existing aquaculture decision support frameworks, focusing on data-driven approaches. Section 3 discusses proposed research models and experimental environment design. Section 4 presents main findings, application prototype, and evaluation discussion. Finally, Section 5 concludes and suggests future research directions.

2. Related Works

2.1. Aquaculture Decision-Making Support Frameworks

The developments and applications of advanced technologies, such as IoT, big data, AI, etc., have recently transformed the aquaculture industry. Applications in aquaculture can include health monitoring [6,7], farming environment management [8,9], nutrition and care optimization [10], and production forecasting [11,12]. Various types of aquaculture big data are generated and can provide valuable insights and practical applications in the industry. Through the application of data analysis methods, farmers can make more accurate and timely decisions, contributing to minimizing risks in production and improving crop productivity. Decision-making support systems are developed to integrate, process, and visualize collected data to provide decision-making recommendations to specific problems [13]. In agriculture, an Agricultural Decision Support System (ADSS) is a computer system that uses data from multiple sources to provide and support informed decisions [14]. In the aquaculture domain, most decision support systems (DSSs) only consider certain aspects and fail to integrate factors relevant to multiple stakeholders [5]. Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of previous DSS in aquaculture.

Table 1.

Comparison of aquaculture DSS frameworks.

Previous studies have developed many DSS in aquaculture, such as CADS_TOOL [15], DDDAS [16], or AQCBR [18]. In the aquaculture domain, most decision support systems only consider certain aspects, such as water quality prediction, site selection, or mortality forecasting. They have not integrated management factors into the same decision-making platform. Additionally, the AkvaVis tool serves as a decision support tool in aquaculture for site selection and management by integrating multiple indicators [19]. These tools use GIS technology and web applications for data visualization and analysis. They also incorporate various environmental and regulatory data relevant to aquaculture operations [20]. Many models still depend on historical data or assumptions and have not effectively utilized real-time data from IoT sensors and modern AI technologies. Therefore, the current research gap lies in building an integrated, dynamic, and intelligent system that can process multi-source data in real time and performing multi-dimensional predictive analysis.

2.2. Aquaculture Data Hub Ecosystem

The term big data refers to large volumes of datasets originating from various sources, including legacy databases, operational files, social networks, sensors, or IoT network devices [21]. Within the aquaculture sector, the rise in advanced technologies such as IoT [22], AI [23,24], machine learning, deep learning algorithms [25], cloud computing facilities [25,26,27], etc., enables the collection of large, diverse data stores from multiple sources. Major difficulties associated with big data will be the need to store and scale it. Therefore, complex data processing systems must be developed as systems that can grow as needed to accommodate future expansion [28] and provide robust and scalable data storage to accommodate the increasing volume of data generated [28]. Processing methods of this type use many advanced tools and algorithms along with extensive technical expertise to process vast amounts of data into useful information [29] and ensure the secure management of data. In addition to the other security aspects described above, data encryption and access controls must also be included as part of the system’s security requirements [30]. As a result of recent advancements in both data storage and processing technologies, there has been an increase in the ability to collect, store, and manage large amounts of data [31]. Data hubs are centralized data platforms that can assist with addressing the problems described above.

A data hub enables users to easily share and transfer data [32] by providing a common data platform for the sharing and transfer of data in all its forms (including pre-processed) and provides a centralized location for connecting multiple data sources. The data hub comprises a central platform with additional components that connect to the central platform; the central platform being the repository of data used by a multitude of applications and services to ensure that the data is accurate and usable. Data hubs enable stakeholders who may not have the technological savvy to track and monitor data through raw data to consumption within data warehouses or data lakes. In the aquaculture and marine domains, previous studies have explored various data hubs to enhance domain understanding and improve economic efficiency. Table 2 summarizes aquaculture data-hub and data ecosystems.

Table 2.

Comparison of aquaculture data hubs.

Data hubs provide substantial benefits to both the economic viability and domain knowledge of the aquaculture industry. In addition, there are other data hubs in the maritime sector. The coastal data hub for the Caribbean was developed to create a centralized database for collecting, processing, and monitoring environmental data across the coastal area [37]. The coastal data hub can gather and integrate data from various sources, including satellite images, sensors, and data collected by governmental agencies. A further example of a platform to collect, preserve, and manage marine spatial data is the Marine Spatial Data Infrastructure [38]. The hub provides a comprehensive view of the coastal environment, supporting the monitoring of ecosystems and tracking climate change.

Data hubs’ benefits can include collecting and processing various data types, generating technical farming manuals, enhancing the technical capabilities of farmers, and promoting international cooperative efforts in aquaculture research. Giuffrida et al. (2025) evaluated how the implementation of the Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) data principles can support decision-making in aquaculture by improving production efficiency [39]. However, the results also demonstrated that the adoption of data sharing principles in the aquaculture industry remains low, as there are limitations regarding the availability of data infrastructures and standards for open data. Sevin and Dikel (2025) surveyed API-based aquaculture research ecosystems that integrated AI, IoT, and open databases [40]. The research results show that combining API and AI can facilitate real-time data sharing. Previous works are limited by the incompatibility between data systems, a lack of API standardization, and data security, and ethics issues when applying AI in research.

Based on the research overview, it can be seen that the major gap in the field lies between data and decision-making. Multiple data sources from aquaculture farming are separated and fragmented. The lack of data-integrated systems entails difficulties. Additionally, developing models to convert raw data into useful information and knowledge for practical operations is also important. Linking data to on-farm production contexts and developing decision support tools remains quite limited, highlighting the urgent need to build a more comprehensive, integrated framework. The development of an aquaculture data hub is important, as the aquaculture sector is transitioning into digitalized transformations. A data hub will enable the centralization of data integration and sharing, linking isolated pieces of information from various data sources. Improved data integration will lead to improved quality, reliability, and traceability of data, providing a basis for data-driven decision-making. We will develop a decision-making support framework to narrow this gap and provide informed decisions. There are four different use cases, including monitoring the farm environment, sharing farm equipment data, calculating costs/profits, and predicting prices.

3. Research Design and Experiment Setup

3.1. Aquaculture Decision-Making Support Framework Design

This paper tries to bridge some important gaps in the field of smart aquaculture by proposing an integrated decision support framework based on a multi-source data hub. The proposed data hub system provides the function of centralization of data integration and sharing, as well as connection between isolated information sources from several sources, such as environmental data, market data, and operational data. In addition, the authors have developed various multidimensional predictive analysis application scenarios. Therefore, it lays the foundations for reliable data-driven decision-making.

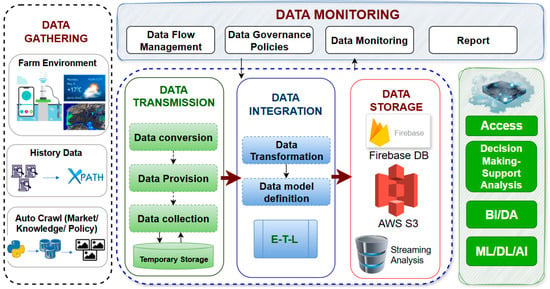

The architecture of our aquaculture decision-making support framework is presented in Figure 1. The design can comprehensively integrate IoT, big data, and AI technologies to collect, process, store, and analyze data for accurate and timely decision-making. We propose a 5-layered functional structure for our proposed smart aquaculture decision support system. These layers are monitored by a data management and monitoring layer that ensures the integrity, security, and synchronization of the information. Firstly, the data collection layer collects information from multiple data sources such as on-farm environmental sensors, historical data, and online information resources for markets, policies, etc. The raw data collected from these multiple data sources will be stored in a temporary database to ensure that all data is collected and transmitted safely. The temporary database allows the system to check, clean, and standardize the data so that the data will be ready for the following processes. The traceability provided by the system will create a solid base for analysis and decision-making in aquaculture management.

Figure 1.

Architecture of aquaculture decision-making support framework.

In the data integration stage, the Extract-Transform-Load (ETL) model is used to extract the data, transform the data, and load the data into the system. At this point, all raw data is temporarily stored in a staging area to ensure safety and availability for the next processing stage. Afterward, the data transformation phase will clean the data sets, remove the missing, incorrect, or duplicate data values. High-frequency collected data will be aggregated by a certain time frame, such as hour, day, and week, which reduces the burden on the system and facilitates higher level analysis models. The data will also be semantically mapped to the attributes (such as pond location, index type, collection time), which ensures that the data can be consistently integrated with other datasets. Finally, during the data loading stage, the processed data will be loaded into the respective storage layers, based on the intended use. Real-time operational data is stored in the Operational Data Store (ODS) for quick querying and instant analysis. Stabilized or periodically aggregated data is transferred to a central data warehouse (image data in AWS S3 or structured data in Firebase) for in-depth analysis using business intelligence, machine learning, deep learning, or AI. Other unstructured data is stored in its raw form in the data lake for future use. The entire process is monitored through data governance policies and continuous monitoring mechanisms, creating a unified, transparent, and flexible system that supports smart aquaculture practices.

3.2. Data Collection

Data collection layer receives information from multiple data sources, including farm environmental sensors, historical data, and online information sources on markets, policies, or professional knowledge.

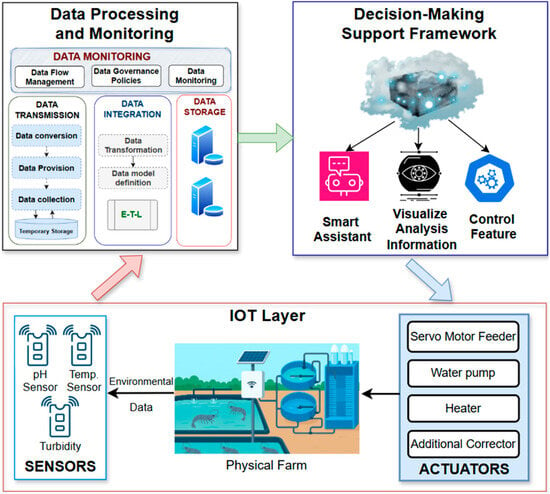

IoT data collection diagram is presented in Figure 2. IoT sensor data is the core component of the data collection layer of this decision support system. In ponds, sensors are arranged at various locations and depths to measure key parameters, including water temperature, salinity, pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), turbidity, ammonia, nitrate, conductivity, and flow velocity. These sensors are connected to a microcontroller, which collects, encodes, and transmits data periodically via wireless communication protocols. The data is then sent to a central gateway or cloud server using standard protocols to ensure information security. Data is temporarily stored in local memory or a staging area to prevent loss in the event of connection interruptions.

Figure 2.

IoT data collection.

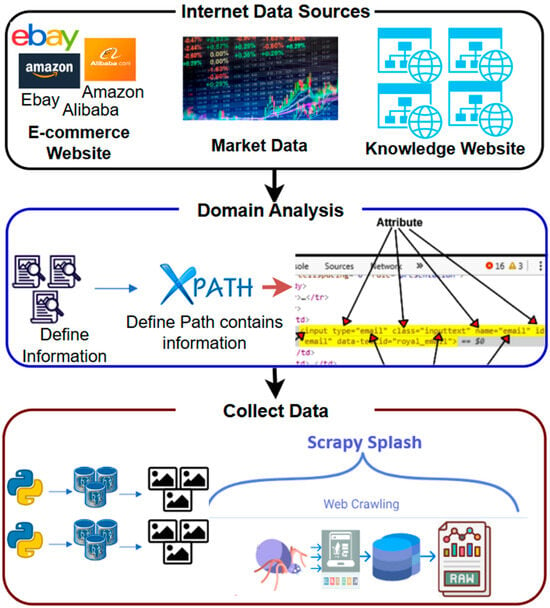

Online data sources include market transaction data, weather forecasts, agricultural equipment information, and farming knowledge collected automatically through automatic gathering and transmission service, as shown in Figure 3. This service operates continuously to collect and update data from various online platforms.

Figure 3.

Internet data sources collection.

The process of automatic online data collection in the decision support system includes three main stages: identifying Internet data sources, analyzing domains, and web scraping. Internet data sources are identified from various groups. E-commerce websites (eBay, Amazon, Alibaba) collect information on agricultural equipment and market prices. Financial websites provide transaction data and price trends. Knowledge websites or specialized portals contain articles, regulations, or technical instructions related to aquaculture. In the domain analysis phase, it is performed to determine the exact path containing the required information. This process uses XPath techniques to extract the HTML structure and determine the specific location of the target data. This allows the system to establish a consistent data pathway, reducing the likelihood of error as the site evolves. Python 3.10 with crawler tools (Scrapy and Selenium) were also used to collect, download, and store information on the sites that were identified during the web scraping process. The data was collected in the forms of text, images, and table formats and then converted into the standard JSON format and temporarily placed in a database. The system is configured to continue crawling the data daily, so it has an active and reliable data source available for the other systems to use for their analysis.

3.3. Decision-Making Support Use Cases

The various types of data within the system are subject to varying levels of complexity due to differences in the structure and characteristics of the data. As such, to maintain the most efficient and accurate process possible, different analytical approaches are used based on the type of data. Real-time IoT sensor data is analyzed through time-series analysis and anomaly detection to monitor changes occurring in the farm’s environment. Real-time data is integrated into an image-based system utilizing natural language processing (NLP) to analyze news and industry reports to gather pertinent information and create a virtual aquaculture assistant. Historical data is analyzed using regression models that assist in identifying the relationship between farm conditions and productivity to enable the system to make productivity estimations. Market data is analyzed through price-forecasting models to support business decision-making and production planning. The flexibility of this approach allows the system to perform a comprehensive analysis and generate accurate recommendations for informed decision-making in aquaculture. A detailed presentation of the prototype implementation for each use case will follow in Section 4.

3.4. Research Environment

In this paper, we built our experiment on low-cost infrastructure that employs open-source software or cloud services, which can significantly reduce the initial financial investment. The research environment is summarized in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Research environment.

4. Implementation Results and Discussion

The development and testing of the prototypes for all use cases are provided in this part. Shrimp are a major fishery product that has a very high level of productivity and economic significance. Shrimp farming can provide farmers and entrepreneurs with a steady source of income and can contribute to increasing export volume, creating other economic opportunities (such as processing, feed, and logistics). However, shrimp farming has its own set of challenges, which include environmental variability, disease, and market risk. The objective of our work is to create a decision support tool for aquaculture focused on shrimp farming that provides farmers and managers with access to real time information about their environment, production, and market conditions. This will enable them to monitor, analyze, and make informed decisions about their operations. The overall goal of this research is to develop data analytics tools to help increase the production efficiency of shrimp farms, reduce the potential for environmental risk, and increase the effectiveness of shrimp farm management.

4.1. Smart Shrimp Farm Assistant

4.1.1. Farm Assistant Dataset

The research dataset has been divided into two separate subsets, each corresponding to the functions of the two layers of the farm monitoring assistant.

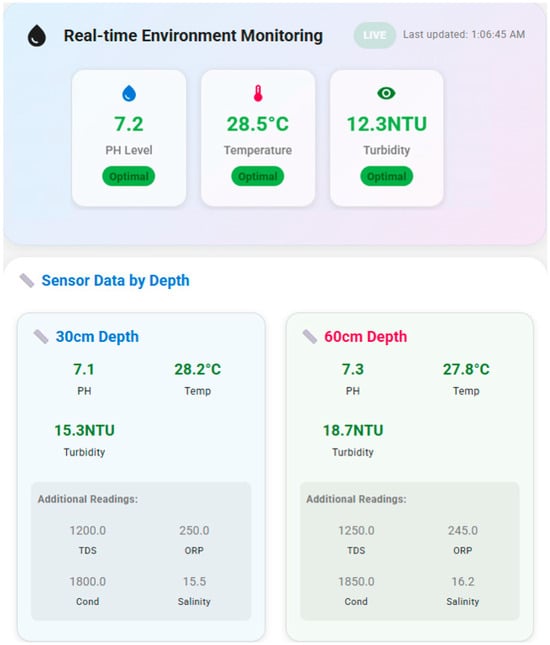

At the IoT layer, we utilize an experimental dataset on water quality monitoring, collected directly from a fishpond by Arafat et al. [41]. The basic quality factors include temperature, pH, and turbidity. The dataset is collected continuously over many days. The paper utilizes data from three sensors, with water levels at 30 cm and 60 cm, recorded continuously for 24 h from 15 to 22 January 2020, at an average rate of one dataset per minute. All sensors collect data simultaneously, while the Arduino Mega microcontroller board serves as the central processor. The first file contains sensor data for a 30 cm depth, comprising 9623 records that include temperature, pH, and turbidity. The second file contains data for 60 cm, comprising 9623 records that include temperature and turbidity.

At the assistant layer, we collect and create a knowledge base dataset related to aquaculture farming operations. By adopting the Internet data sources collection process, multiple farming guidelines, aquaculture production reports, statistics, global monitoring data, and scientific advice are retrieved from Oceans and Fisheries (https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/index_en) [42], Agriculture Organization (https://www.fao.org/home/en) [43], World Fish Center (https://worldfishcenter.org/) [44], etc. We also transform this data into the form of ‘prompt’ and ‘completion’ for training and deploying the GPT model.

4.1.2. Farm Monitoring Assistant Implementation

The real-time Shrimp Farming Environment Monitoring Interface, as shown in Figure 4, provides a means for users to continuously monitor important environmental parameters in the pond. The data automatically collected from IoT sensors installed at various locations and at different depths within the pond help instantaneously determine the current conditions for shrimp growth. The system shows these real-time synthetic indicators (pH, temperature, and turbidity). The lower part shows sensor data by depth at 30 cm and 60 cm. Measurements at multiple water layers help assess thermal and oxygen stratification, factors that greatly affect shrimp health. The system also records additional indicators such as turbidity, salinity, ORP, TDS, and conductivity to help users assess the overall water quality.

Figure 4.

Farming environment monitoring interface. Abbreviations: NTU, Nephelometric Turbidity Units; TDS, Total Dissolved Solids; ORP, Oxidation-Reduction Potential; Cond, Conductivity.

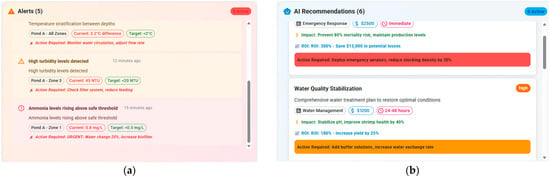

The interface in Figure 5 displays warnings and recommendations per actual farm environmental conditions. The system operates based on real-time sensor data collected in the ponds, then analyzes it, detects abnormalities, and automatically recommends optimal solutions for farm operators. In Figure 5a, Warnings, the system detects environmental problems in the pond. These warnings help farmers recognize early signs of environmental instability and take timely corrective actions. In Figure 5b, the recommendations are calculated by the system based on the level of risk, cost, profit, and intervention effectiveness.

Figure 5.

Farming environment recommendation interface: (a) alerts notification; (b) environment recommendation.

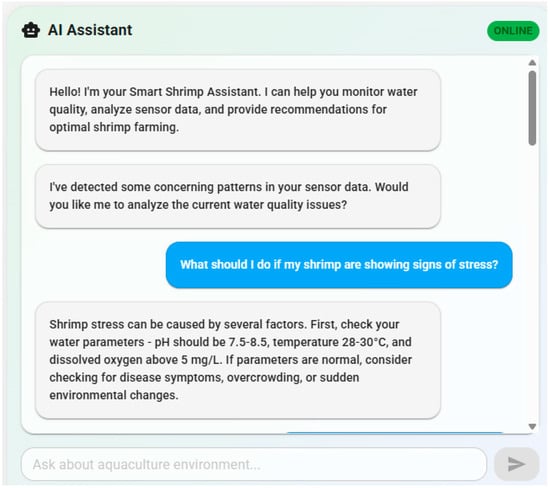

Additionally, we offer an assistant that utilizes a fine-tuned GPT-3.5 model to our aggregated knowledge base, which is relevant to aquaculture practices. The assistant can deliver responses and pertinent information regarding shrimp farming practices (see Figure 6). Recommendations and guidance can be provided through the pre-set-up rules and user context. These recommendations can serve as guidelines for farmers in selecting shrimp species, implementing disease preventive strategies, identifying diseases, and analyzing data from IoT systems. These proposals aim to provide farmers with suitable assistance.

Figure 6.

Aquaculture assistant interface.

4.2. Shrimp Farm Equipment Data Sharing

4.2.1. Farm Equipment Dataset

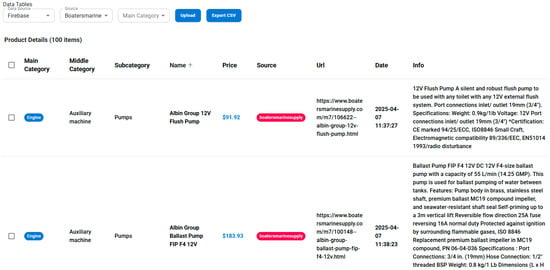

During the construction and operation of shrimp farms, equipment such as aerators, environmental sensors, pumping systems, automatic feeders, and water treatment devices play an essential role in maintaining stable farming conditions and optimizing productivity. To assist farmers in making informed decisions, we provide a function for sharing shrimp equipment data, offering a comprehensive view of available hardware options. We collect detailed information on these devices from reputable e-commerce platforms such as Amazon, Alibaba, eBay, and BestBuy, including equipment names, selling prices, illustrations, technical specifications, supplier links, function descriptions, and user reviews. This data is automatically updated in the system, stored, and displayed on a web interface, enabling farmers to easily compare prices and select products that meet their needs and budget, thereby saving time on their search.

The aquaculture farming equipment industry encompasses a wide range of products, including water pumps, aerators, water filtration systems, and devices for measuring environmental indicators. The product information captured from e-commerce websites is stored for further processing and analysis, using AWS S3 for image or video data and Firebase for comprehensive product data management. This integration allows us to maintain an up-to-date database that supports efficient decision-making for shrimp farmers.

4.2.2. Farm Equipment Data Sharing Implementation

Figure 7 illustrates the shrimp farming equipment data management interface. This interface allows users to access, search, filter, and export equipment data. The interface contains filters and data manipulation tools, including data source options, main categories, and two functions, which allow users to import or extract data for analysis. The data table displays a detailed list of equipment products with main information fields. The displayed information includes name, price, short description, and original link to help users easily access product details, compare prices, and choose equipment.

Figure 7.

Farm equipment data sharing interface.

4.3. Farm Cost and Profit Calculator

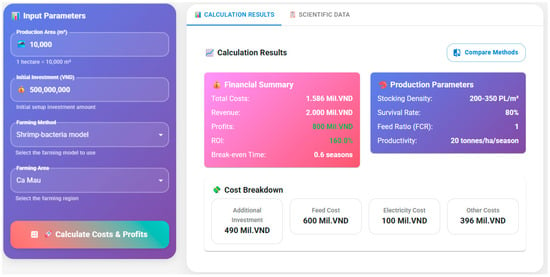

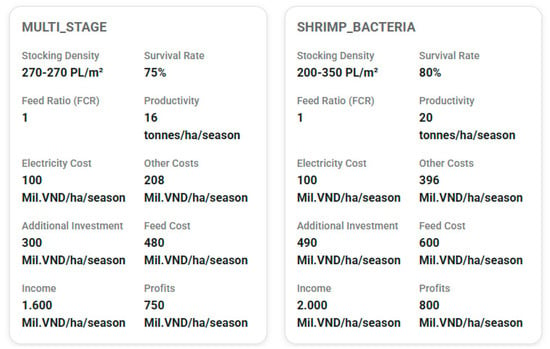

The farm cost and profit calculator helps farmers estimate the financial efficiency of shrimp farming models based on input parameters. The input indicators and calculation parameters in the model are built based on the evaluation report of the status of shrimp farming technology in Vietnam [45]. Our system enables users to calculate the total investment cost, expected revenue, profit, return on investment (ROI), and payback period using data inputs. Farmers can select the farming method, farming area, and production scale. After that, farmers can compare the efficiency between different models, thereby making a reasonable investment plan and optimizing operating costs. Our system also provides detailed analysis of cost structures such as equipment investment costs, feed costs, electricity, and other costs, helping users understand the proportion of each item in terms of total production cost. In addition, typical production indicators (such as stocking density, survival rate, yield, and feed conversion ratio) are also analyzed.

The shrimp farm cost and profit calculator interface is shown in Figure 8. On the left side of the interface are the user input areas, where the user can enter all the input parameters necessary to run a simulation based upon the type of shrimp farm and the location of that farm. The input parameters include the production area (in m2) and the initial investment capital (VND). The user can select one of three farming methods and select the farming area (location). Once all the input values have been entered by the user, the system will automatically perform an analysis of all costs associated with the shrimp farm and calculate both revenue and profits. The right portion of the screen shows the detailed results from the calculations performed by the system, which includes total investment costs, expected revenue, estimated profits, and return on investment. The system also provides users with typical production parameters (e.g., stocking density, survival rate, feed conversion ratio, average yield). In addition, the system performs a detailed cost analysis, providing users with information about how the capital has been allocated among the different categories of costs, including equipment investment costs, feed costs, electricity costs, and other costs.

Figure 8.

Farm cost and profit calculator.

Figure 9 shows the interface to compare shrimp farm investments with different methods. This interface compares in detail the differences between variables including stocking density, survival rates, yield per crop, electricity costs, feed costs, additional investment, etc. In addition to that, this interface calculates the total income and profit to be able to make an accurate comparison of both options. The comparison interface also allows the farmer to compare his or her actual production conditions and find out which production method is best suited for those conditions.

Figure 9.

Farm Investments Comparison.

4.4. Aquaculture Market Analysis

Business and production planning are supported using price forecasting models analyzing market data. The Minneapolis Grain Exchange (MGE) is the only exchange trading a seafood commodity futures contract, specifically frozen shrimp. This helps producers or farmers of this commodity to protect and secure their profits, while at the same time reduce their exposure to risk when it comes to their financials. In addition to helping farmers financially, these futures contracts also attract additional investment and provide financing for the growth of the U.S. aquaculture industry. However, they can carry risks such as price fluctuations and supply chain uncertainty. The system uses raw financial data as input to predict price changes.

The research dataset covers daily Kanex frozen shrimp futures. Daily data has been gathered from 2010 to 2024, encompassing Date, Open Price, High Price, Low Price, Close Price, Adjusted Close Price, and Trading Volume. The dataset comprises 2805 usable data points spanning nearly 15 years, from January 2010 to October 2025. The dataset was divided into three segments: the final model testing dataset, comprising around 1.2%; the validation dataset, accounting for about 14.7%; and the training dataset, which constitutes roughly 84.1%. The training dataset encompasses the period from January 07 to April 16; the validation dataset extends from 17 April 2024 to 10 September 2025; and the testing dataset ranges from 11 September 2025 to 22 October 2025. This segmentation technique enables the incorporation of recent data, including the volatility surge in July 2022, during the validation and model-tuning phase.

The building of an aquaculture price prediction model process includes preprocessing price data, training and testing models, and comparing and selecting the best-performing model. First, data undergoes several preprocessing techniques, such as data augmentation, normalization, and raw feature extraction. Eliminating outliers is a crucial process in the purification of time series data. The methodology employs z-score and box-plot analysis to identify and eliminate outliers. Anomalously high or low data points are excluded to enhance the precision of time series forecasting models. Furthermore, the impact of elevated volatility is addressed through variance modification. The data is normalized by dividing it by the square root of the variance, thereby mitigating the excessive influence of extremely volatile values. The moving average filtering method is employed to enhance the data and stabilize the time series. Thereafter, the data is normalized and divided into three segments: training, testing, and validation data. The training data is employed during the model training phase. This paper utilizes GARCH models and neural network models. Two evaluation metrics, Root Mean Square Percentage Error (RMSPE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), are employed to assess the models. Table 4 summarizes the evaluation of aquaculture price prediction models.

Table 4.

Evaluation of aquaculture price prediction models.

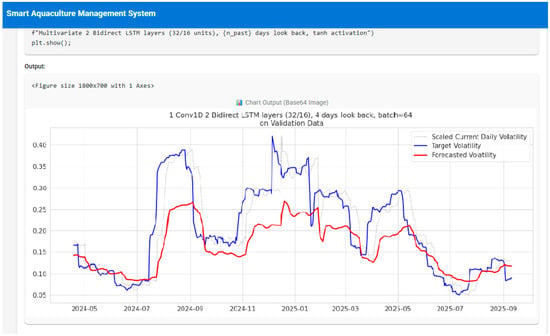

Among the models, the Conv1D model with two bidirectional LSTM layers achieved the best performance, with an RMSPE of 0.291624 and RMSE of 0.073509, demonstrating its strong ability to capture temporal dependencies in price data. The Bootstrap TARCH(1,2,1) model also performed well, with an RMSPE of 0.311185 and RMSE of 0.058731, although it was lower than the Conv1D model. The GJR-GARCH(1,1,1) model had an RMSPE of 0.341383 and RMSE of 0.081698, which was helpful for volatility analysis. The simpler LSTM model, with one layer and 20 units, performed worse, with an RMSPE of 0.441610 and RMSE of 0.059256, indicating that it was unable to capture the complexities of the time series. Finally, the multivariate LSTM model with three layers did not improve performance, with an RMSPE of 0.458288 and RMSE of 0.105380, possibly due to overfitting resulting from the complex architecture. These results suggest that the 1 Conv1D 2 Bidirect LSTM can help to predict aquaculture prices. In contrast, statistical models, although useful for volatility analysis, are not flexible enough to capture changes in the aquaculture market. The final model is constructed to analyze and predict aquaculture market trends, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Aquaculture market analysis interface.

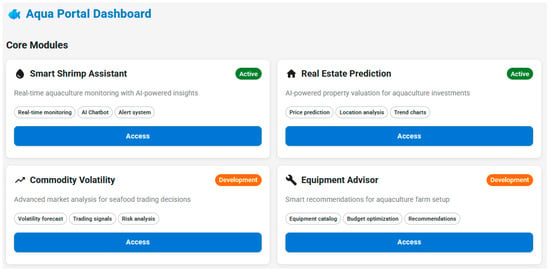

4.5. Evaluation Performance Discussion

Our paper proposes and develops an integrated decision-making support framework using a multi-source data hub. Our developed system has focused on four main core modules, as managed and visualized in the system dashboard (see Figure 11). First, the system provides real-time shrimp farming environment monitoring through automatic IoT sensor data. We provide an assistant that utilizes a fine-tuned GPT-3.5 model for aggregated knowledge base relevant to aquaculture practices.

Figure 11.

Aquaculture core modules.

Next, the sharing shrimp equipment module provides a function that enables farmers to access a comprehensive view of information and select the appropriate hardware equipment for production. Additionally, the farm cost and profit calculator in this module allows farmers to estimate the financial efficiency of shrimp farming models based on specific input parameters.

Finally, market data is analyzed by price forecasting models to support business decisions and production planning. The results show that the best model, the Conv1D model with two bidirectional LSTM layers, achieved an RMSPE of 0.291624 and RMSE of 0.073509, demonstrating its strong ability to capture temporal dependencies in price data. Our system can analyze and predict aquaculture market trends.

In this research, we present a four-module integrated decision-making model. Our model is unique in that it combines various factors from multiple stakeholders into a single framework that can process data in near real-time. This model therefore has the potential to provide better decision support than current models, such as CADS_TOOL [15], DDDAS [16], and AQCBR [18], which focus on specific areas, such as water quality, cage fish farming, etc., and lack the ability to combine data and make decisions across multiple stakeholder groups.

5. Conclusions

Big data and AI Technology are creating new opportunities for aquaculture to create long-term changes to how aquaculture operates. The current aquaculture industry supports a significant portion of the world’s food supply. Therefore, our research proposed a framework for decision-making support system, utilizing a multi-source data hub, which will be established to enhance current operational practices in aquaculture. This framework will be designed to collect and integrate multiple types of big data from aquaculture (environmental data, trading data, and Internet data sources). Four main modules were developed, including monitoring environmental factors for shrimp farming, sharing shrimp farming equipment, calculating costs/profits associated with shrimp farming, and predicting price changes. Experimental prototypes of web-based systems provide users with a user-friendly platform to access the analysis results and recommendations provided to support decisions made during aquaculture production. The proposed framework can connect, analyze, and convert different aquaculture data streams into valuable information for decision-making, thereby improving operational efficiency in the aquaculture industry.

This framework demonstrates the potential for utilizing big data and AI to enhance aquaculture operations by proposing an aquaculture decision support framework. However, there are certain limitations. First, the research data is limited in scope and quality. The system lacks real-time data, so recommendations cannot adapt to market or environmental changes. The system is tested in an experimental environment without being validated in real-world situations. Therefore, future work will evaluate farmers’ preparedness to adopt technology and assess its operational efficacy in a realistic setting across different real-world farming contexts. In the future, expanding and standardizing multi-source datasets will also be studied. This will involve data from satellite images, behavioral information, and automated water systems to improve the accuracy of the prediction model. Next, we will integrate reinforcement learning, anomaly detection, or adaptive optimization techniques to improve decision-making support. Finally, future work should focus on expanding the system’s interoperability through the full application of FAIR data principles, thereby improving transparency, reusability, and integration with other research platforms. In addition, standardizing APIs according to international specifications will enable the system to easily connect to external data sources, support real-time information exchange, and minimize dependence on individual formats.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.-B.-V.L.; Data Curation, N.-B.-V.L., Y.L. and J.-H.H.; Formal Analysis, N.-B.-V.L.; Funding Acquisition, H.-J.K.; Investigation, N.-B.-V.L., Y.L., H.-D.T., H.-J.K. and J.-H.H.; Methodology, N.-B.-V.L., Y.L., H.-D.T., H.-J.K. and J.-H.H.; Project Administration, H.-J.K. and J.-H.H.; Resources, N.-B.-V.L.; Software, N.-B.-V.L.; Supervision, H.-D.T., H.-J.K. and J.-H.H.; Validation, N.-B.-V.L., Y.L., H.-D.T., H.-J.K. and J.-H.H.; Visualization, Y.L. and H.-D.T.; Writing—Original Draft, N.-B.-V.L., Y.L., H.-D.T., H.-J.K. and J.-H.H.; Writing—Review and Editing, H.-J.K. and J.-H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, and Forestry (IPET) and the Korea Smart Farm R&D Foundation (KosFarm) through the Smart Farm Innovation Technology Development Program, funded by the Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affair (MAFRA) and the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT), Rural Development Administration (RDA) (grant number: RS-2025-02305747).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors. The coding environment employed is Visual Studio, encompassing Python programming capabilities alongside Node.js and React Native. The database management system in use is Firebase. Developing mobile applications uses Expo as a framework for building React Native applications.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Le, N.-B.; Woo, H.; Lee, D.; Huh, J.-H. AgTech: A Survey on Digital Twins Based Aquaculture Systems. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 125751–125767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.W.K. Implementation of artificial intelligence in aquaculture and fisheries: Deep learning, machine vision, big data, internet of things, robots and beyond. J. Comput. Cogn. Eng. 2024, 3, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prapti, D.R.; Shariff, A.R.M.; Man, H.C.; Ramli, N.M.; Perumal, T.; Shariff, M. Internet of Things (IoT)-based aquaculture: An overview of IoT application on water quality moni-toring. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 979–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodashahri, N.G.; Sarabi, M.M.H. Decision support system (DSS). Singaporean J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2013, 1, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathisen, B.M.; Haro, P.; Hanssen, B.; Björk, S.; Walderhaug, S. Decision support systems in fisheries and aquaculture: A systematic review. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.08374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.; Ghosh, A.R. Role of artificial intelligence (AI) in fish growth and health status monitoring: A review on sustainable aquaculture. Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 2791–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuncha, P.; Manoranjini, J.; Sirisha, J.; Bandeela, S.; Penjarla, N.K.; Goud, S.S. Advanced Aquaculture Management: A Smart System for Optimizing Oxygen Levels, Shrimp Health Monitoring. In Smart Factories for Industry 5.0 Transformation; Nidhya, R., Kumar, M., Karthik, S., Anand, R., Balamurugan, S., Eds.; Wiley-Scrivener Publishing: Beverly, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 283–298. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Iwasaki, M.; Guadalupe, G.A.; Pachas-Caycho, M.; Chapa-Gonza, S.; Mori-Zabarburú, R.C.; Guerrero-Abad, J.C. Internet of Things (IoT) Sensors for Water Quality Monitoring in Aqua-culture Systems. Agriengineering 2025, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-P.; Khabusi, S.P. Artificial intelligence of things (AIoT) advances in aquaculture: A review. Processes 2025, 13, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmessery, W.M.; Abdallah, S.E.; Oraiath, A.A.T.; Espinosa, V.; Abuhussein, M.F.A.; Szűcs, P.; Eid, M.H.; El-Shinawy, D.M.; Aljumayi, H.; Mahmoud, S.F.; et al. A deep deterministic policy gradient approach for optimizing feeding rates and water quality management in recirculating aquaculture systems. Aquac. Int. 2025, 33, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yin, J.; Yang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Li, C. Intelligent forecasting model for aquatic production based on artificial neural network. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1556294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ni, M.; Lu, Z.; Ma, L. Prediction and Analysis of Sturgeon Aquaculture Production in Guizhou Province Based on Grey System Model. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terribile, F.; Agrillo, A.; Bonfante, A.; Buscemi, G.; Colandrea, M.; D’ANtonio, A.; De Mascellis, R.; De Michele, C.; Langella, G.; Manna, P.; et al. A Web-based spatial decision supporting system for land management and soil conservation. Solid Earth 2015, 6, 903–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Martínez, J.F.; Beltran, V.; Martínez, N.L. Decision support systems for agriculture 4.0: Survey and challenges. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 170, 105256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halide, H.; Stigebrandt, A.; Rehbein, M.; McKinnon, A. Developing a decision support system for sustainable cage aquaculture. Environ. Model. Softw. 2009, 24, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, S.; McCulluch, J. A dynamic data-driven decision support for aquaculture farm closure. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2014, 29, 1236–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Chen, J.; Wen, J.; Xie, W.; Lin, M. Analysis decision-making system for aquaculture water quality based on deep learning. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1544, 12028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathisen, B.M.; Bach, K.; Aamodt, A. Using extended siamese networks to provide decision support in aquaculture operations. Appl. Intell. 2021, 51, 8107–8118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangnery, A.; Bacher, C.; Boyd, A.; Liu, H.; You, J.; Strand, Ø. Web-based public decision support tool for integrated planning and management in aquaculture. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 203, 105447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, L.; Knight, B.; Symonds, J.; Waddington, Z.; Davidson, I. A decision support system to predict mortality events in finfish aquaculture. Aquac. Environ. Interactions 2025, 17, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seref, S.; Sinanc, D. Big data: A review. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Collaboration Technologies and Systems (CTS), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–24 May 2013; pp. 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, M.; Chana, I.; Clarke, S. A survey on IoT Big Data: Current status, 13 v’s challenges, and future directions. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, D.E. Artificial intelligence and big data. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2013, 28, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Dhunny, Z.A. On big data, artificial intelligence and smart cities. Cities 2019, 89, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RLippmann, R. An introduction to computing with neural nets. IEEE Assp. Mag. 1987, 4, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, D.; Das, S.; El Abbadi, A. Big data and cloud computing: Current state and future opportunities. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Extending Database Technology, Uppsala, Sweden, 21–24 March 2011; pp. 530–533. [Google Scholar]

- Hashem, I.; Targio, A.; Yaqoob, I.; Anuar, N.B.; Mokhtar, S.; Gani, A.; Khan, S.U. The rise of “Big Data” on cloud computing: Review and open research issues. Inf. Syst. 2015, 47, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oussous, A.; Benjelloun, F.-Z.; Lahcen, A.A.; Belfkih, S. Big Data technologies: A survey. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2018, 30, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandri, V. Enterprise Data Security Measures: A Comparative Review of Effectiveness and Risks Across Different Industries and Organization Types. Int. J. Bus. Intell. Big Data Anal. 2023, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Kung, L.; Byrd, T.A. Big data analytics: Understanding its capabilities and potential benefits for healthcare organizations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 126, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadepally, V.; Kepner, J. Technical Report: Developing a Working Data Hub. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.00190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, O.; Dandurand, L.; Brown, S. On the design of a cyber security data sharing system. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM Workshop on Information Sharing & Collaborative Security, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 3 November 2014; pp. 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, G.L.; O’Connor, W.; Fielder, D.S.; Booth, M.; Heasman, H. Aquaculture Innovation Hub. Final Report Project, 2008; Volume 902. Available online: https://www.frdc.com.au/sites/default/files/products/2008-902-DLD.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Raymond, K.; Stacey, D.; Bernardo, T. Aquaculture Data Management and Governance Strategy. 2021. Available online: https://gbads-documentation.s3.ca-central-1.amazonaws.com/20210418_AquacultureGBADsInformatics.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Sami, J.; Bumbak, M.; Camargo, U.; Rautiainen, T.; Ryhänen, M.; Šermukšnytė-Alešiūnienė, K. Aquahubs-Project: Supporting Aquaculture Innovation Experiments. Case Automatic Estimation of Fish Stock; South-Eastern Finland University of Applied Science, XAMK Development; 2022; Volume 197, pp. 1–45. Available online: https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/755913/URNISBN9789523444416.pdf?sequence=2 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Sivkov, Y.A. Building maritime data hub by using the Arduino IoT platform. In Global Perspectives in MET: Towards Sustainable, Green and Integrated Maritime Transport; 2017; pp. 533–540. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Charlott-Sellberg/publication/320335664_Training_skills_and_assessing_performance_in_simulator-based_learning_environments/links/59df30daa6fdccfcfda315c8/Training-skills-and-assessing-performance-in-simulator-based-learning-environments.pdf#page=533 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Jevrejeva, S.; Matthews, A.; Williams, J. Development of a Coastal Data Hub for Stakeholder Access in the Caribbean Region. 2019. Available online: https://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/523770/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Contarinis, S.; Kastrisios, C. Marine spatial data infrastructure. In The Geographic Information Science & Technology Body of Knowledge, 1st ed.; 2022; Available online: https://gistbok-topics.ucgis.org/DM-07-091 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Giuffrida, R.; de Majo, C.; Giuffrida, M.; Broadbent, I.D. FAIR data management practices to introduce cir-cular economy in aquaculture: Benefits, barriers and a preliminary roadmap. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2025, 20, 4995–5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevin, S.; Dikel, S. Building a Collaborative Aquaculture Research Ecosystem with APIs and AI. Aquat. Sci. Eng. 2025, 40, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahid, A.-A.; Arafat, A.I.; Akter, T.; Ahammed, F.; Ali, Y. KU-MWQ: A dataset for monitoring water quality using digital sensors. Mendeley Data 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oceans and Fisheries Home Page. Available online: https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/fisheries_en (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Available online: https://www.fao.org/home/en/https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/fisheries_en (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- World Fish Center. Available online: https://worldfishcenter.org/ (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. Evaluation of Shrimp Farming Technology and Recommendations on Solutions for the Sustainable Development of Shrimp Industry. Mekong Delta Climate Resilience Programme (MCRP). 2020. Available online: https://mcrp.mard.gov.vn/FileUpload/2021-09/cW7NBvRC1UWmdCVe200821%20Aquaculture%20technology%20EN.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).