Artificial Intelligence in Questionnaire-Based Research: Quality of Life Classification Across Different Population Groups

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Concept of Quality of Life

1.2. The WHOQOL-BREF Instrument

- Physical health—This domain explores aspects such as pain, discomfort, energy, fatigue, mobility, sleep, and activities of daily living.

- Psychological health—Items here assess positive and negative feelings, self-esteem, bodily image, spirituality, and cognitive functions like concentration.

- Social relationships—This dimension focuses on personal relationships, social support, and sexual activity.

- Environmental health—A broad domain that evaluates safety, physical environment, financial resources, access to health services, opportunities for recreation, and transportation.

1.3. Psychometric Robustness and Global Norms

1.4. Research Context: The Retirement Threshold as a Key Application

1.5. Defining the ‘Threshold’ in Multidisciplinary Contexts

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Design

- employees: Individuals currently engaged in employment ().

- retirees1: Retired individuals not participating in U3A activities (; 98 women, 69 men).

- retirees2: Retired individuals who are active students at the U3A (; 67 women, 24 men).

2.2. Data Collection and Features

2.3. Machine Learning Approach: The XGBoost Algorithm

Model Implementation and Training Protocol

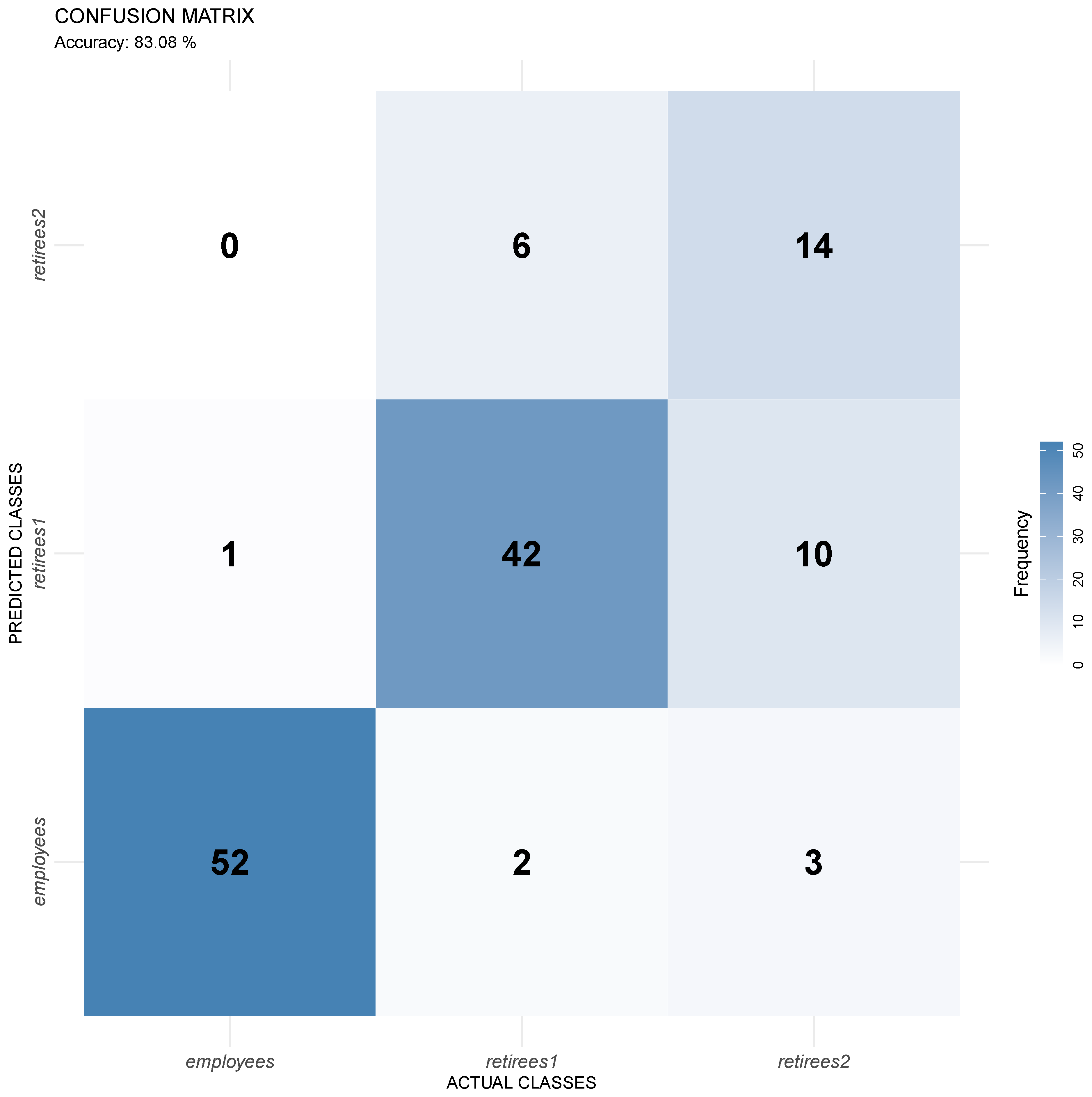

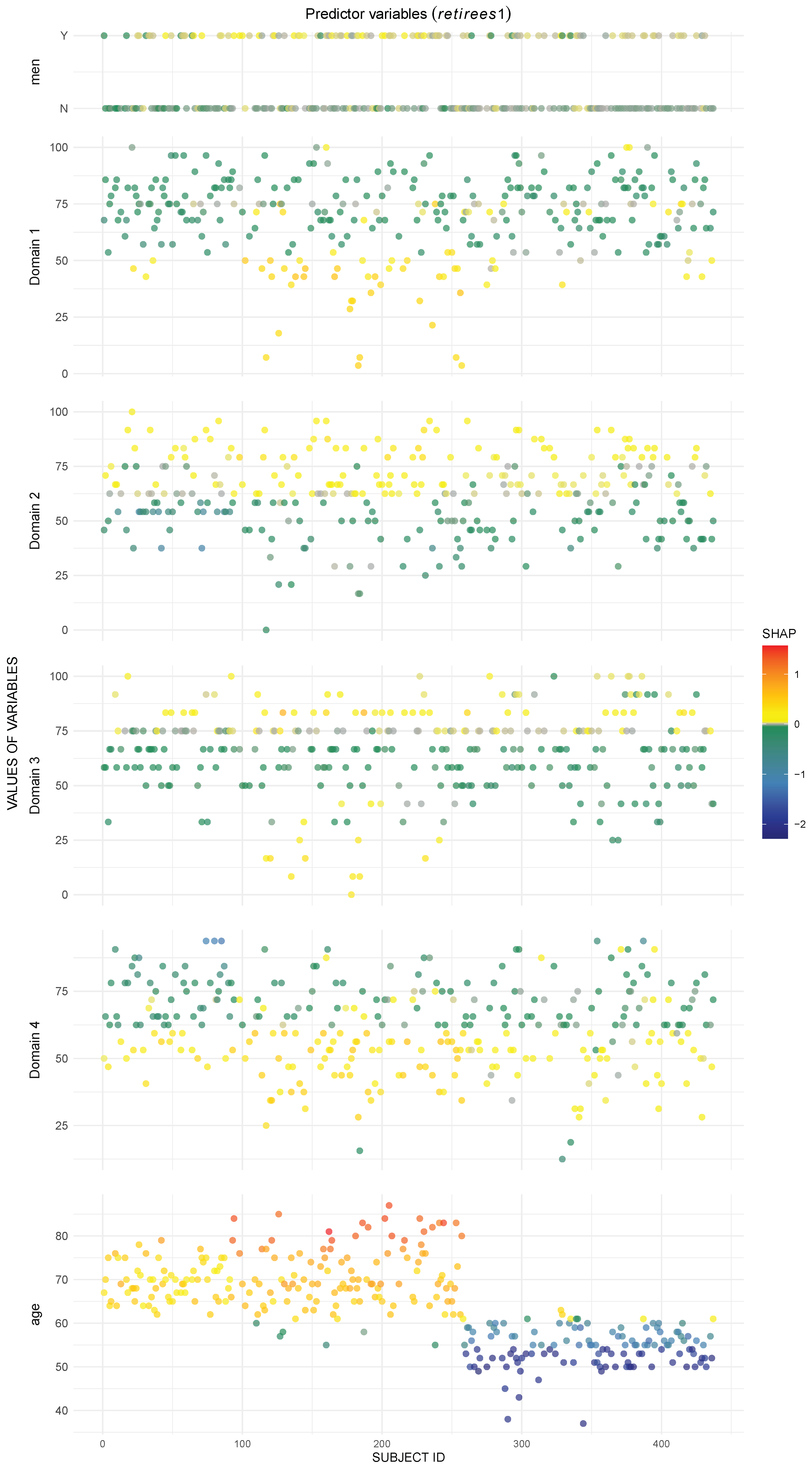

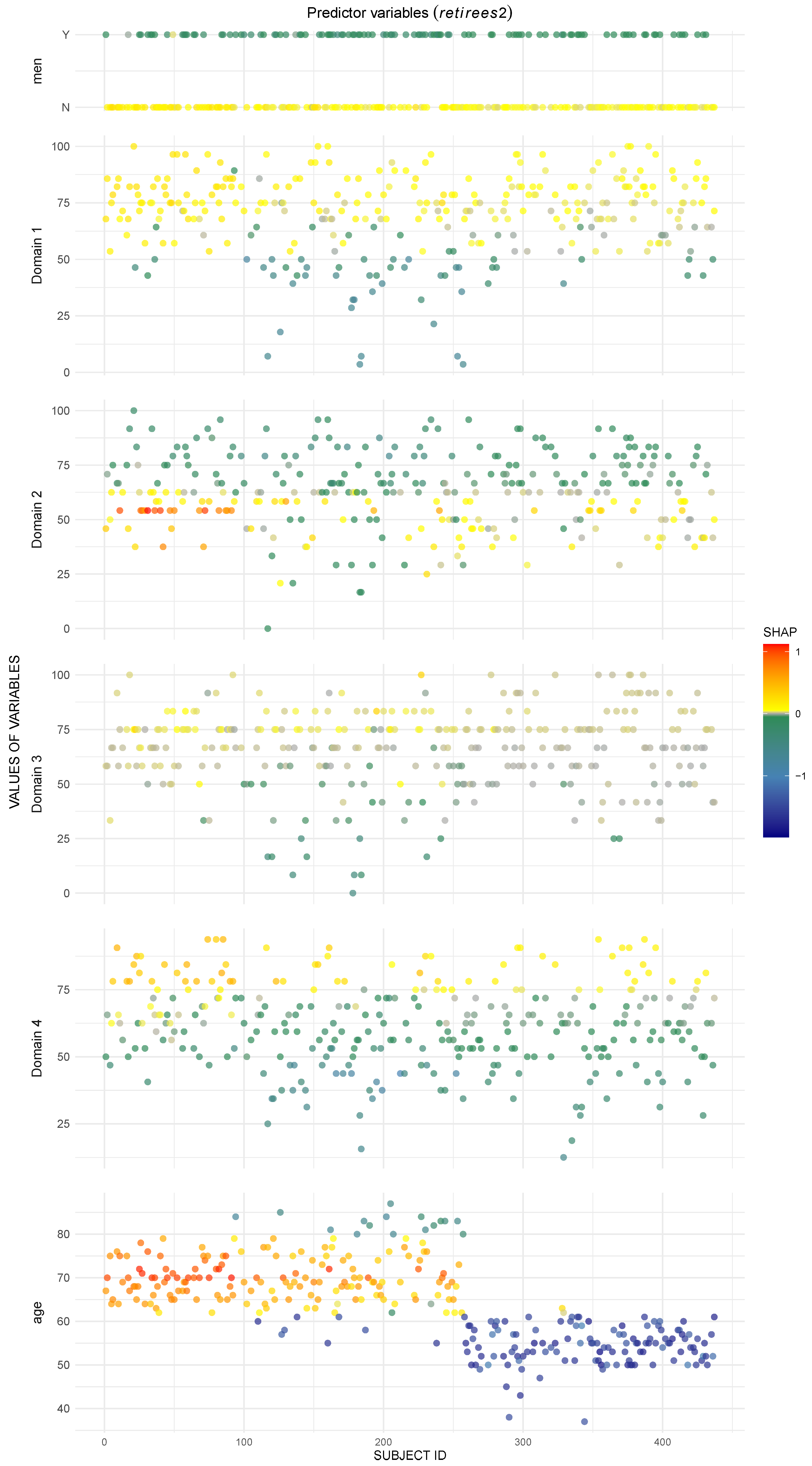

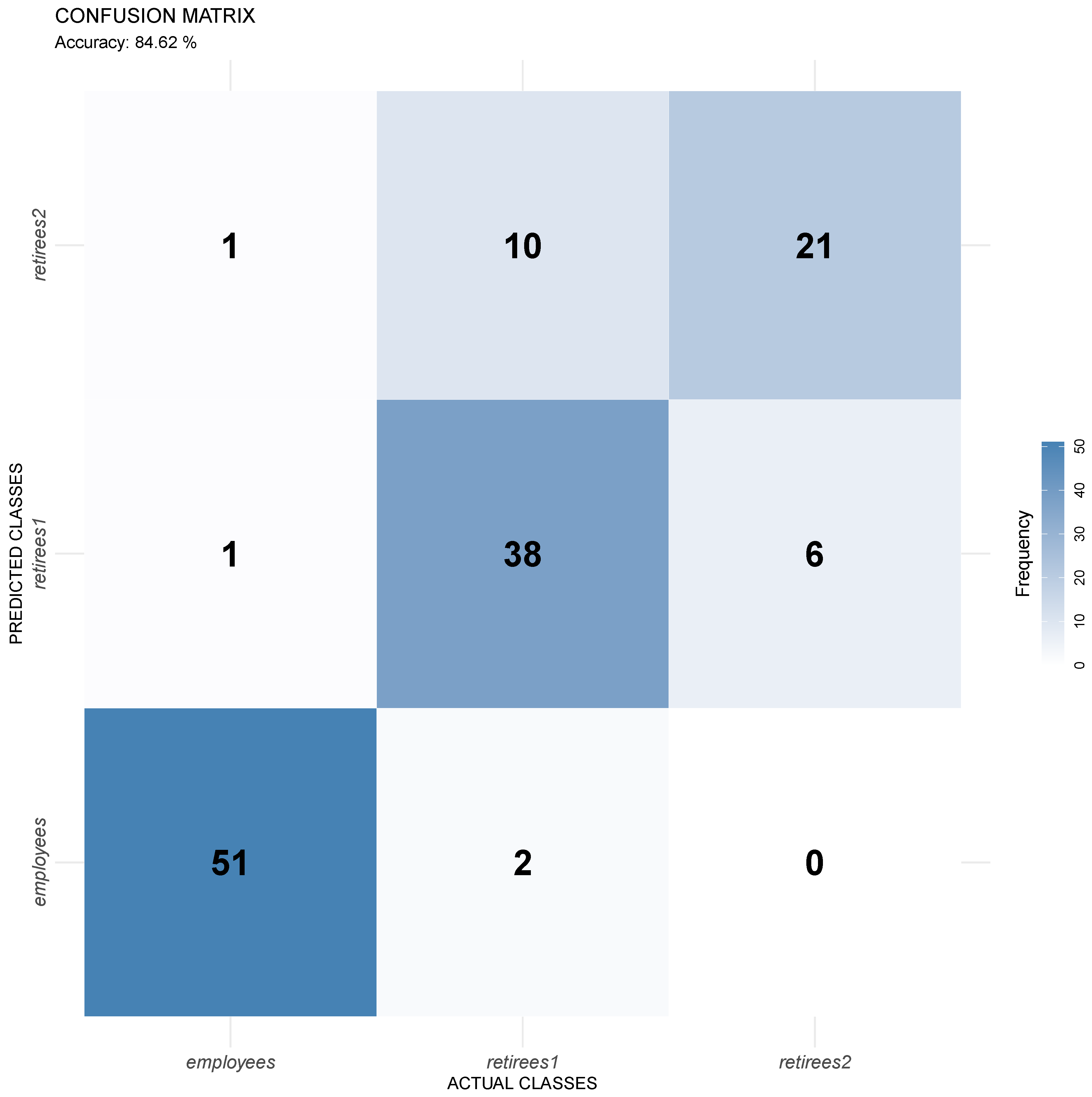

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bielińska, A.; Wąż, P.; Bielińska-Wąż, D. A Computational Model of Similarity Analysis in Quality of Life Research: An Example of Studies in Poland. Life 2022, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielińska, A.; Bielińska-Wąż, D.; Wąż, P. Classification Maps in Studies on the Retirement Threshold. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielińska, A.; Majkowicz, M.; Bielińska-Wąż, D.; Wąż, P. A New Method in Bioinformatics—Interdisciplinary Similarity Studies. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2116, 450013. [Google Scholar]

- Bielińska, A.; Majkowicz, M.; Wąż, P.; Bielińska-Wąż, D. A New Computational Method: Interdisciplinary Classification Analysis. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2116, 450014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielińska, A.; Majkowicz, M.; Bielińska-Wąż, D.; Wąż, P. Classification Studies in Various Areas of Science. In Numerical Methods and Applications; Nikolov, G., Kolkovska, N., Georgiev, K., Eds.; Conference Proceedings NMA 2018, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11189, pp. 326–333. [Google Scholar]

- Bielińska, A.; Majkowicz, M.; Wąż, P.; Bielińska-Wąż, D. Mathematical Modeling: Interdisciplinary Similarity Studies. In Numerical Methods and Applications; Nikolov, G., Kolkovska, N., Georgiev, K., Eds.; Conference Proceedings NMA 2018, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11189, pp. 334–341. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/whoqol/whoqol-bref (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Karnofsky, D.A.; Burchenal, J.H. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents in Cancer; New York Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1948; p. 634. [Google Scholar]

- Zubrod, C.O.; Scheidemann, M.; Frei, E., III; Brindley, C.; Gold, G.L.; Shnider, B.; Oviedo, R.; Gorman, J.; Jones, R.; Jonsson, U.; et al. Appraisal of methods for the study of chemotherapy of cancer in man: Comparative therapeutic trial of nitrogen mustard and triethylene thiophosphoramide. J. Chronic Dis. 1960, 11, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, H. Quality of Life: Principles of the Clinical Paradigm. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 1990, 8, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISOQOL—International Society for Quality of Life Research. Available online: https://www.isoqol.org (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Baday-Keskin, D.; Ekinci, B. The relationship between kinesiophobia and health-related quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A controlled cross-sectional study. Jt. Bone Spine 2022, 89, 105275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moitra, S.; Foraster, M.; Arbillaga-Etxarri, A.; Marín, A.; Barberan-Garcia, A.; Rodríguez-Chiaradia, D.A.; Balcells, E.; Koreny, M.; Torán-Monserrat, P.; Vall-Casas, P.; et al. Roles of the physical environment in health-related quality of life in with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Environ. Res. 2022, 203, 111828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, T.T.; Mei, S.L.; Li, M.Z.; O’Donnell, K.; Caron, J.; Meng, X.F. Impulsivity mediates the relationship between childhood maltreatment and quality of life: Does social support make it different? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 184, 111208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, S.; Van den Boom, W.; Higgs, P.; Dietze, P.; Erbas, B. The association between depression and oral health related quality of life in people who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 229, 109121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooth, L.R.; Moss, K.M.; Mishra, G.D. Screen time and child behaviour and health-related quality of life: Effect of family context. Prev. Med. 2021, 153, 106795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Tebar, A.; Ruiz-Hermosa, A.; Martinez-Vizcaino, V.; Martin-Espinosa, N.M.; Notario-Pacheco, B.; Sanchez-Lopez, M. Health-related quality of life in developmental coordination disorder and typical developing children. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 119, 104087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggart, R.; Polter, E.; Ross, M.; Kohli, N.; Konety, B.R.; Mitteldorf, D.; West, W.; Rosser, B.R.S. Comorbidity Prevalence and Impact on Quality of Life in Gay and Bisexual Men Following Prostate Cancer Treatment. Sex. Med. 2021, 9, 100439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long-Meek, E.; Asay, G.L.; Cope, M.R. Clarifying Community Concepts: A Review of Community Attachment, Community Satisfaction, and Quality of Life. Societies 2025, 15, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksana, A.L.; Hertanti, N.S. Concept analysis of diabetes-related quality of life. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2025, 23, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandarakutty, S.; Arulappan, J. Health-related quality of life of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease: An evolutionary concept analysis. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2024, 80, 151862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saputra, F.; Sutrisna, E.; Ardilla, A.; Fauziah. Quality of life among Indonesian school-aged children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A concept analysis. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2024, 15, 348–356. [Google Scholar]

- Raymundo, C.; Asare, C.; Chen, J.N.F.; Shabbir, A.; Yoon, I.C.; Kim, E.; Perez-Chada, L.; Thornton, S.; Larocca, C.; Shinohara, M. Generation of Concepts for a Core Domain Set to Assess Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma: A Mixed Methods Study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2025, 93, AB213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, C.; Chen, J.N.F.; Naidoo, P.; Raymundo, C.; Tawa, M.; Khan, N.; Olsen, E.; Ottevanger, R.; Scarisbrick, J.; Thornton, S.; et al. Defining Core Concepts for Health-Related Quality of Life for Patients with Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome: A Systematic Literature Review. JEADV Clin. Pract. 2025, 4, 907–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remon, H.; Philippe, L.; Daniel, S.; Lothar, S.; Raja, P. Hypophosphatasia (HPP) Patient & Caregiver Disease Burden, Quality of Life & Treatment Experience: A Mixed Methods Study Concept. Value Health 2025, 28, S347. [Google Scholar]

- Bunn, D.; Zhang, W.J.; Smith, N.; Jimoh, O.; Greenstock, J.; Edoo, M.; Towers, A.M. Minimising the impact of infectious outbreaks on resident quality of life: A qualitative proof of concept study using the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT). PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0316424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsolami, M.F.; Bettaieb, D.; Malek, R. The Challenges of Achieving WELL Standards in Residential Apartment Design and Enhancing the Concept of Quality of Life: An Analytical Study in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Archit. Plan.-King Saud Univ. 2025, 37, 123–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.F.; Mao, Z.X.; Yang, Z.H.; Feng, S.L.; Busschbach, J. The EQ-5D and EQ-HWB fit the perceptions of quality of life from a Chinese perspective: A concept mapping study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2025, 23, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, K.; Hayashi, F.; Kuriyama, A.; Nakayama, T.; Suzukamo, Y. Change in the General Public’s Concept of Quality of Life Over Time in Three National Surveys: Part 1: Awareness and Concept. Qual. Life Res. 2024, 33, S148. [Google Scholar]

- Suzukamo, Y.; Miyazaki, K.; Hayashi, F.; Kuriyama, A.; Nakayama, T. Changes in the General Public’s Concept of Quality of Life Over Time in Three National Surveys: Part 2: Conceptual Structure. Qual. Life Res. 2024, 33, S147. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, J.; Villettaz-Robichaud, M.; Dubuc, J.; Santschi, D.; Roy, J.P.; Fecteau, G.; Buczinski, S. Graduate Student Literature Review: Integrating concepts of animal welfare and health-related quality of life for preweaning dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 3868–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiana, L.; Sánchez-Ruiz, J.; Vidal-Blanco, G.; Sansó, N. Validation of the Spanish Version of the Nursing Self-Concept Instrument: Psychometric Properties and Study of Its Relations with Clinical Practice and Professional Quality of Life in Nursing Students. Nurs. Health Sci. 2025, 27, e70173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabcová, D.B.; Otáhalová, A.; Kohout, J.; Suleková, M.; Masková, I.; Belohlávková, A.; Krsek, P. Quality of life, academic self-concept, and mental health in children with epilepsy: The possible role of epilepsy comorbidities. Epilepsy Behav. 2025, 170, 110471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagna, A.; Schwartz, C.; Huffmann, B.; Hitzl, W.; Kristof, R.A.; Clusmann, H.; Blume, C. Analysis of quality of life and outcomes of vestibular schwannoma patients after resection and radiosurgery in an interdisciplinary treatment concept. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaglauer, K.; Kunsorg, A.; Jakob, V.; Görg, L.; Oehlschlägel, A.; Riedel, R.; Marschall, U.; Welsink, D.; Schuhmacher, H.; Wittmann, M. Effect of a Multimodal Pain Therapy Concept Including Intensive Physiotherapy on the Perception of Pain and the Quality of Life of Patients with Chronic Back Pain: A Prospective Observational Multicenter Study Named “RütmuS”. Pain Res. Manag. 2025, 2025, 6693678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost-Engl, J.; Ketter, R.; Brandt, R.; Völker, K.; Gerss, J.; Jetschke, K.; Lucas, C.W.; Baumann, F.T.; Lepper, P.M.; Urbschat, S.; et al. Enhancing cardiorespiratory fitness and quality of life in high-grade glioma through an intensive exercise intervention during chemotherapy: Proof of concept. Neuro-Oncology 2025, noaf176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.L.; Lv, L.J.; Zhang, Q.W. Impact of Empowerment Education Concept Plus Humanistic Care on Moods and Quality of Life in Lung Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy. Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2025, 35, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Gong, L. Effect of Enhanced Recovery after Surgery Concept Combined with Roy’s Adaptation Model on Perioperative Mental Health, Quality of Life, Recovery Conditions, and Postoperative Complications in Patients Undergoing Radical Prostatectomy: A Retrospective Study. Arch. Urol. 2024, 77, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shen, Z.Y.; Zhong, X.L.; Chen, M. Effect of graded nursing based on risk early warning concept on the incidence of pressure injury, quality of life, and negative affect of long-term bedridden patients. Am. Transl. Res. 2024, 16, 5454–5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmeister, S.; Ferentzi, H.; Schmitt, K.R.L. Electronic patient-reported outcome measures in pediatric cardiology. Health-related quality of life as a useful concept for holistic care. Monatsschrift Kinderheilkd. 2025, 173, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allgaier, K.; Veríssimo, S.; Tan, S.; Orlikowski, M.; Hartung, M. LLOD-Driven Bilingual Word Embeddings Rivaling Cross-Lingual Transformers in Quality of Life Concept Detection from French Online Health Communities. In Further with Knowledge Graphs; Alam, M., Groth, P., de Boer, V., Pellegrini, T., Pandit, H.J., Montiel, E., Doncel, V.R., McGillivray, B., Meroño-Peñuela, A., Eds.; Studies on the Semantic Web; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 53, pp. 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Barwais, F.A. Associations between Physical Activity Levels and Quality of Life Dimensions among Saudi Female University Students: A Cross-Sectional Analysis Using WHOQOL-BREF and IPAQ-SF. Phys. Educ. Stud. 2025, 29, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-H.; Lin, C.-C.; Wu, Z.-Z.; Wu, A.-B.; Chang, Y.-T.; Lin, C.-Y.; Wang, J.-D.; Sung, J.-M. Validating Psychometric Properties of Generic Quality-of-Life Instruments (WHOQOL-BREF (TW) and EQ-5D) among Non-Dialysis Chronic Kidney Disease: Rasch and Confirmatory Factor Analyses. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2025, 124, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamad, M.; Smadi, S.A.; Arabiat, D. A Multivariate Analysis of Reported Quality of Life among Medical Students in Jordan Using the WHOQOL-BREF. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2025, 14, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, F.M.A. Gender Difference in Domain-Specific Quality of Life Measured by Modified WHOQoL-BREF Questionnaire and Their Associated Factors among Older Adults in a Rural District in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangwanrattanakul, K.; Kulthanachairojana, N. Modern Psychometric Evaluation of Thai WHOQOL-BREF and Its Shorter Versions in Patients Undergoing Warfarin in Thailand: Rasch Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzykowski, M.O.; Vranceanu, A.M.; Macklin, E.A.; Mace, R.A. Minimal Clinically Important Difference in the World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief (WHOQOL-BREF) for Adults with Neurofibromatosis. Qual. Life Res. 2024, 33, 1233–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bat-Erdene, E.; Hiramoto, T.; Tumurbaatar, E.; Tumur-Ochir, G.; Jamiyandorj, O.; Yamamoto, E.; Hamajima, N.; Oka, T.; Jadamba, T.; Lkhagvasuren, B. Quality of Life in the General Population of Mongolia: Normative Data on WHOQOL-BREF. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagliardi, J.; Brettschneider, C.; König, H.H. Health-Related Quality of Life of Refugees: A Systematic Review of Studies Using the WHOQOL-Bref Instrument in General and Clinical Refugee Populations in the Community Setting. Confl. Health 2021, 15, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, L.A.; Zynda, A.J.; Tracey, A.J.; Pollard-McGrandy, A.M.; Davis, E.R.; Loftin, M.C.; Covassin, T. A-12 Relationship Between Risk Propensity and Perceived Concussion Retirement Thresholds in College-Aged Athletes Following Concussion. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2025, 40, i12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bär, M.; Gatzert, N.; Ruß, J. Optimal Asset allocation in Retirement Planning: Threshold-Based Utility Maximization. J. Risk Financ. 2021, 22, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.; Cruwys, T.; Haslam, C.; Wang, V. Social Group Memberships, Physical Activity, and Physical Health Following Retirement: A Six-Year Follow-Up from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 505–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulakka, A.; Leskinen, T.; Suorsa, K.; Pentti, J.; Halonen, J.I.; Vahtera, J.; Stenholm, S. Physical Activity Across Retirement Transition by Occupation and Mode of Commute. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2020, 52, 1900–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrouste, C.; Perdrix, E. The Effect of Retirement on Health. MS-Med. Sci. 2020, 36, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Pulakka, A.; Leskinen, T.; Koster, A.; Pentti, J.; Vahtera, J.; Stenholm, S. Daily Physical Activity Patterns Among Aging Workers: The Finnish Retirement and Aging Study (FIREA). Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 76, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, A. At the Threshold of Retirement: From All-Absorbing Relations to Self-Actualization. J. Women Aging 2017, 29, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syse, A.; Veenstra, M.; Furunes, T.; Mykletun, R.J.; Solem, P.E. Changes in Health and Health Behavior Associated with Retirement. J. Aging Health 2017, 29, 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olds, T.S.; Sprod, J.; Ferrar, K.; Burton, N.; Brown, W.; van Uffelen, J.; Maher, C. Everybody’s Working for the Weekend: Changes in Enjoyment of Everyday Activities Across the Retirement Threshold. Age Ageing 2016, 45, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kail, B. The Mental and Physical Health Consequences of Changes in Private Insurance Before and After Early Retirement. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 71, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S.K.; Evans, K. The learning cultures of Third Age participants: Institutional management and participants’ experience in U3A in the UK and SU in Korea. KEDI J. Educ. Policy 2007, 4, 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hebestreit, L. The role of the University of the Third Age in meeting needs of adult learners in Victoria, Australia. Aust. J. Adult Learn. 2008, 48, 547–565. [Google Scholar]

- Trusz, S.; Fabiś, A.; Berek, T.; Kempa, S.; Zaremba-Żółtek, B.; Sitko, A.; Augustyn, D.; Dendek, K. The Structure of Seniors’ Needs and Their Level of Fulfillment at Universities of the Third Age in Poland. Eur. J. Educ. 2025, 60, e70219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonati, J.G.; Modeneze, D.M.; Vilarta, R.; Maciel, É.S.; Boccaletto, E.M.A.; da Silva, C.C. Body composition and quality of life (QoL) of the elderly offered by the “University Third Age” (UTA) in Brazil. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2011, 52, e31–e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackowicz, J.; Wnek-Gozdek, J. It’s never too late to learn—How does the Polish U3A change the quality of life for seniors? Educ. Gerontol. 2016, 42, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bužgová, R.; Kozáková, R.; Bobčíková, K.; Matějovská Kubešová, H. The importance of the university of the third age to improved mental health and healthy aging of community-dwelling older adults. Educ. Gerontol. 2023, 50, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- XGBoost Developers. XGBoost Documentation. 2016. Available online: https://xgboost.readthedocs.io/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Bentejac, C.; Csörgő, A.; Martínez-Muñoz, G. A Comparative Analysis of XGBoost. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2021, 54, 1937–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M. Building Predictive Models in R Using the caret Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 28, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; He, T.; Benesty, M.; Khotilovich, V.; Tang, Y.; Cho, H.; Chen, K.; Mitchell, R.; Cano, I.; Zhou, T.; et al. xgboost: Extreme Gradient Boosting. R Package Version 1.7.11.1. 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=xgboost (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Just, A. SHAPforxgboost: SHAP Plots for ’XGBoost’. R Package Version 0.1.3. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=SHAPforxgboost (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Hadley, W. Reshaping Data with the reshape Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Men | Domain 1 | Domain 2 | Domain 3 | Domain 4 | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Importance Measures | |||||||

| SHAP Global Importance | 0.0556 | 0.1215 | 0.1044 | 0.0714 | 0.1402 | 1.2920 | |

| SHAP Importance employees | 0.0386 | 0.0662 | 0.0127 | 0.0903 | 0.0455 | 1.9376 | |

| SHAP Importance retirees1 | 0.0248 | 0.1582 | 0.1438 | 0.0896 | 0.1938 | 0.9356 | |

| SHAP Importance retirees2 | 0.1033 | 0.1400 | 0.1565 | 0.0344 | 0.1813 | 1.0028 | |

| Gain | 0.0166 | 0.0758 | 0.0556 | 0.0314 | 0.0667 | 0.7538 | |

| Cover | 0.0296 | 0.1250 | 0.1383 | 0.0705 | 0.1544 | 0.4823 | |

| Frequency | 0.0443 | 0.1907 | 0.1508 | 0.1131 | 0.1663 | 0.3348 | |

| Variables | Men | Domain 1 | Domain 2 | Domain 3 | Domain 4 | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Importance Measures | |||||||

| SHAP Global Importance | 0.0830 | 0.2040 | 0.1095 | 0.0588 | 0.0848 | 1.3431 | |

| SHAP Importance employees | 0.1263 | 0.1769 | 0.0331 | 0.0045 | 0.0096 | 2.2182 | |

| SHAP Importance retirees1 | 0.0000 | 0.2372 | 0.1371 | 0.0821 | 0.1087 | 0.8731 | |

| SHAP Importance retirees2 | 0.1225 | 0.1981 | 0.1583 | 0.0897 | 0.1360 | 0.9380 | |

| Gain | 0.0188 | 0.0767 | 0.0416 | 0.0286 | 0.0403 | 0.7941 | |

| Cover | 0.0408 | 0.1548 | 0.1185 | 0.0574 | 0.1083 | 0.5201 | |

| Frequency | 0.0474 | 0.1565 | 0.1654 | 0.0920 | 0.1160 | 0.4228 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wąż, P.; Bielińska-Wąż, D.; Bielińska-Kaczmarek, A. Artificial Intelligence in Questionnaire-Based Research: Quality of Life Classification Across Different Population Groups. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13123. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413123

Wąż P, Bielińska-Wąż D, Bielińska-Kaczmarek A. Artificial Intelligence in Questionnaire-Based Research: Quality of Life Classification Across Different Population Groups. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13123. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413123

Chicago/Turabian StyleWąż, Piotr, Dorota Bielińska-Wąż, and Agnieszka Bielińska-Kaczmarek. 2025. "Artificial Intelligence in Questionnaire-Based Research: Quality of Life Classification Across Different Population Groups" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13123. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413123

APA StyleWąż, P., Bielińska-Wąż, D., & Bielińska-Kaczmarek, A. (2025). Artificial Intelligence in Questionnaire-Based Research: Quality of Life Classification Across Different Population Groups. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13123. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413123