Tectonic Inversion of the SCS from 3-D Magnetization Vector Clustering: Evidence for Differential Rotation and Ridge Jump

Abstract

1. Introduction

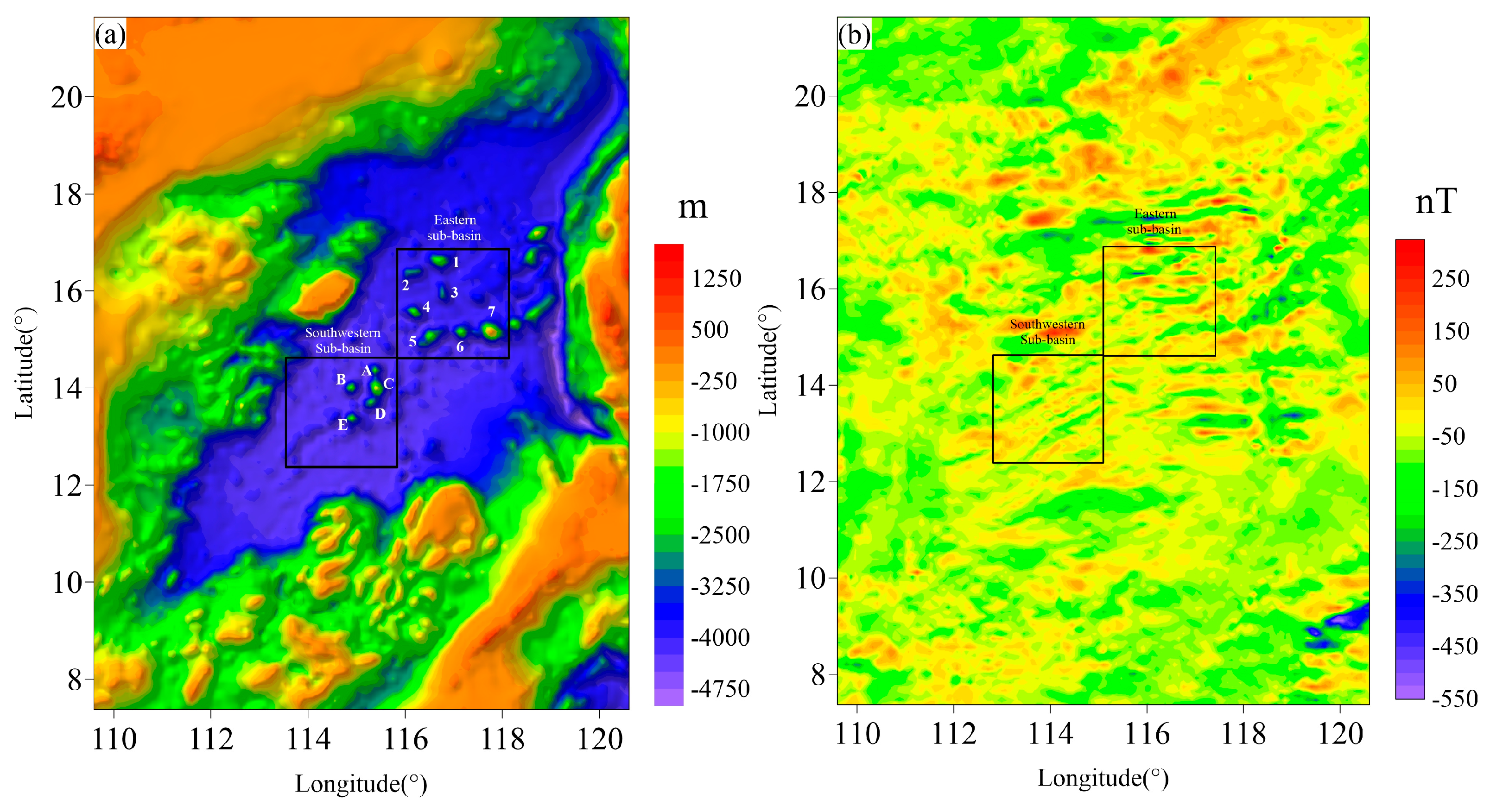

2. Geological Setting

3. Methodology

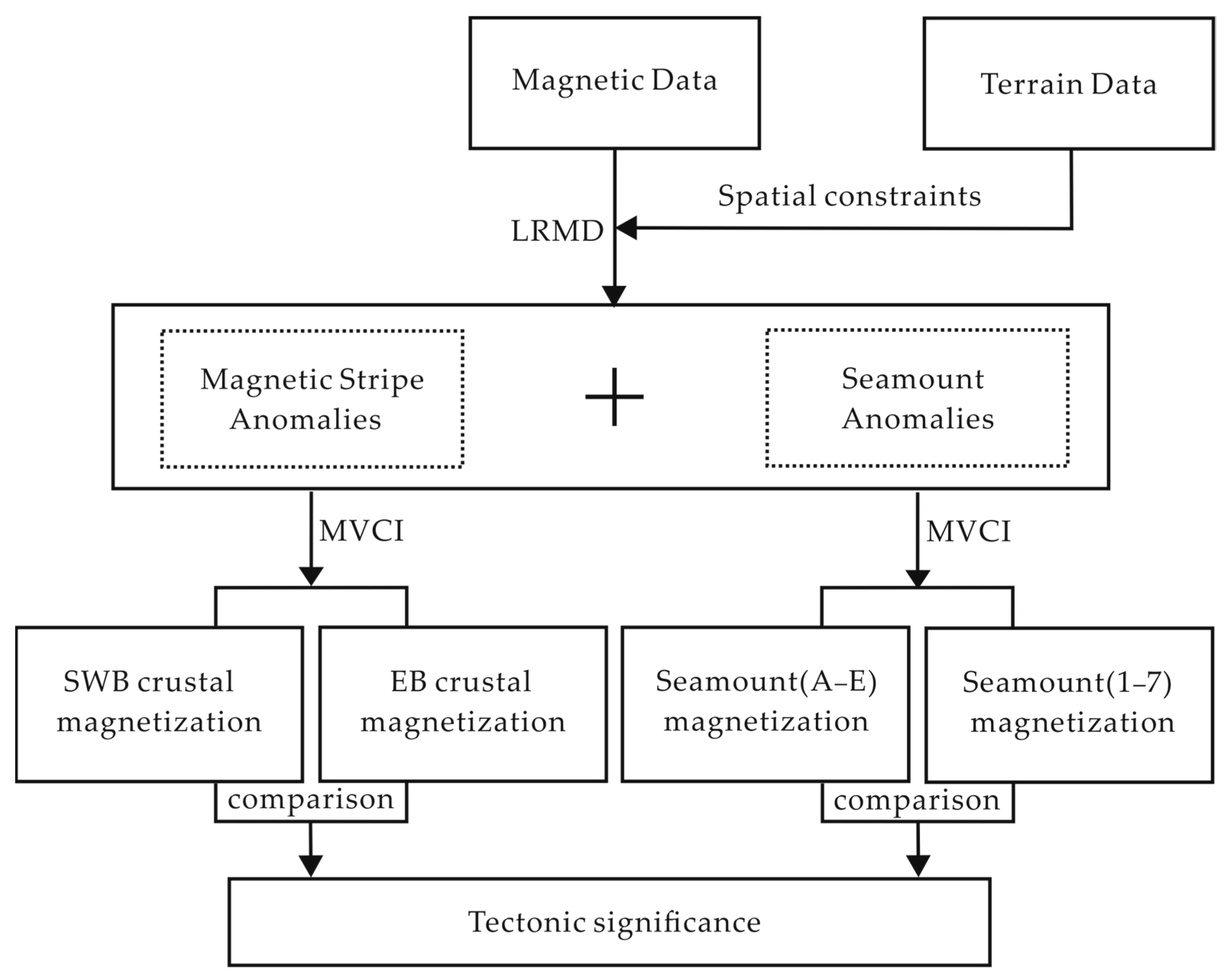

3.1. Workflow Overview

- Low-rank Hankel matrix decomposition (LRMD) disentangles co-located seamount and stripe anomalies originating at comparable depths but exhibiting distinct spatial wavelengths;

- Magnetization-vector inversion (MVCI) recovers 3-D magnetization intensity and direction for each component without a priori orientation constraints;

- Magnetization-based tectonic interpretation compares recovered magnetization vectors between the eastern and southwestern sub-basins to quantify differential geological processes.

3.2. Low-Rank Hankel Matrix Separation

3.3. Magnetization-Vector Cluster Inversion

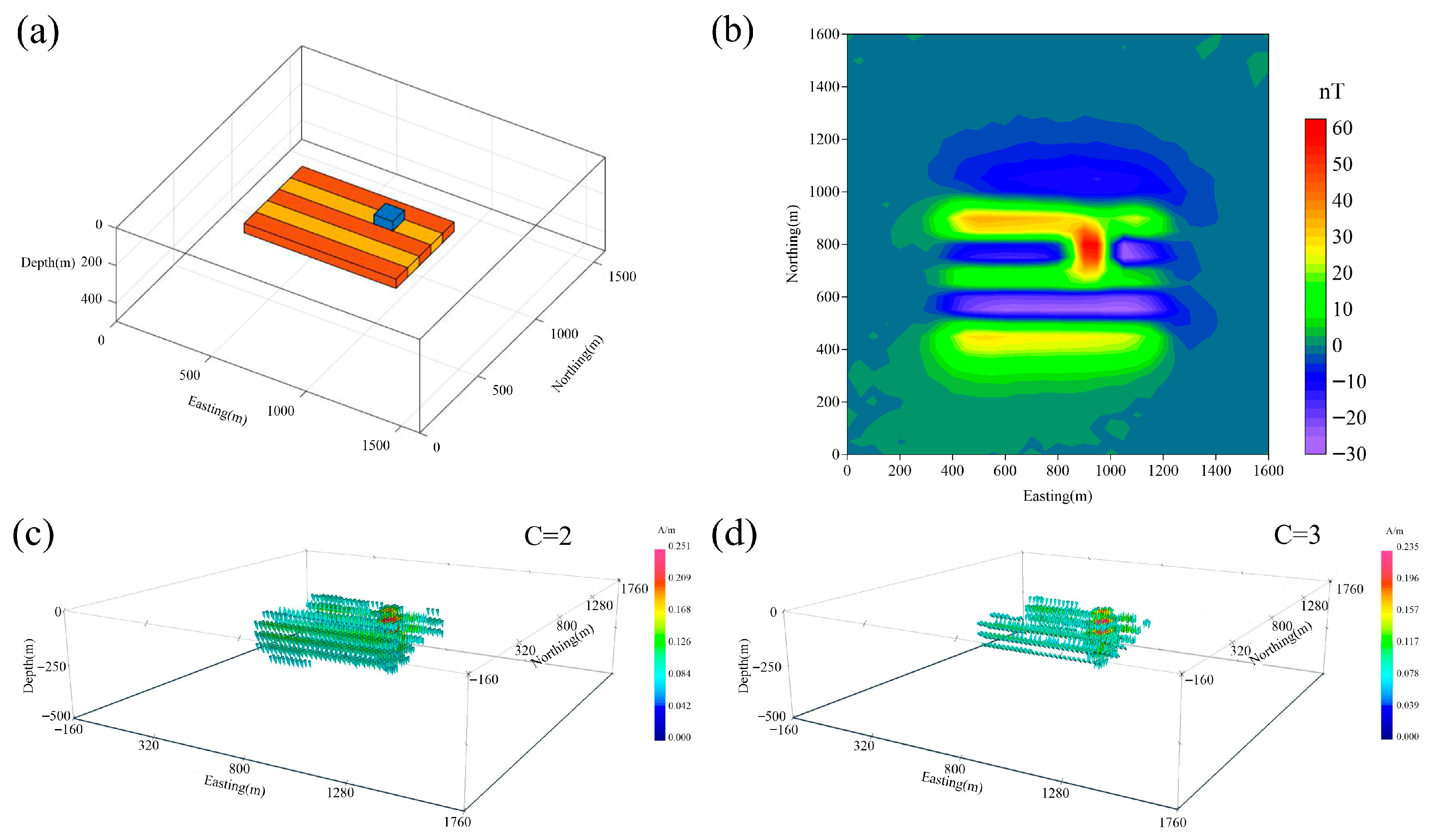

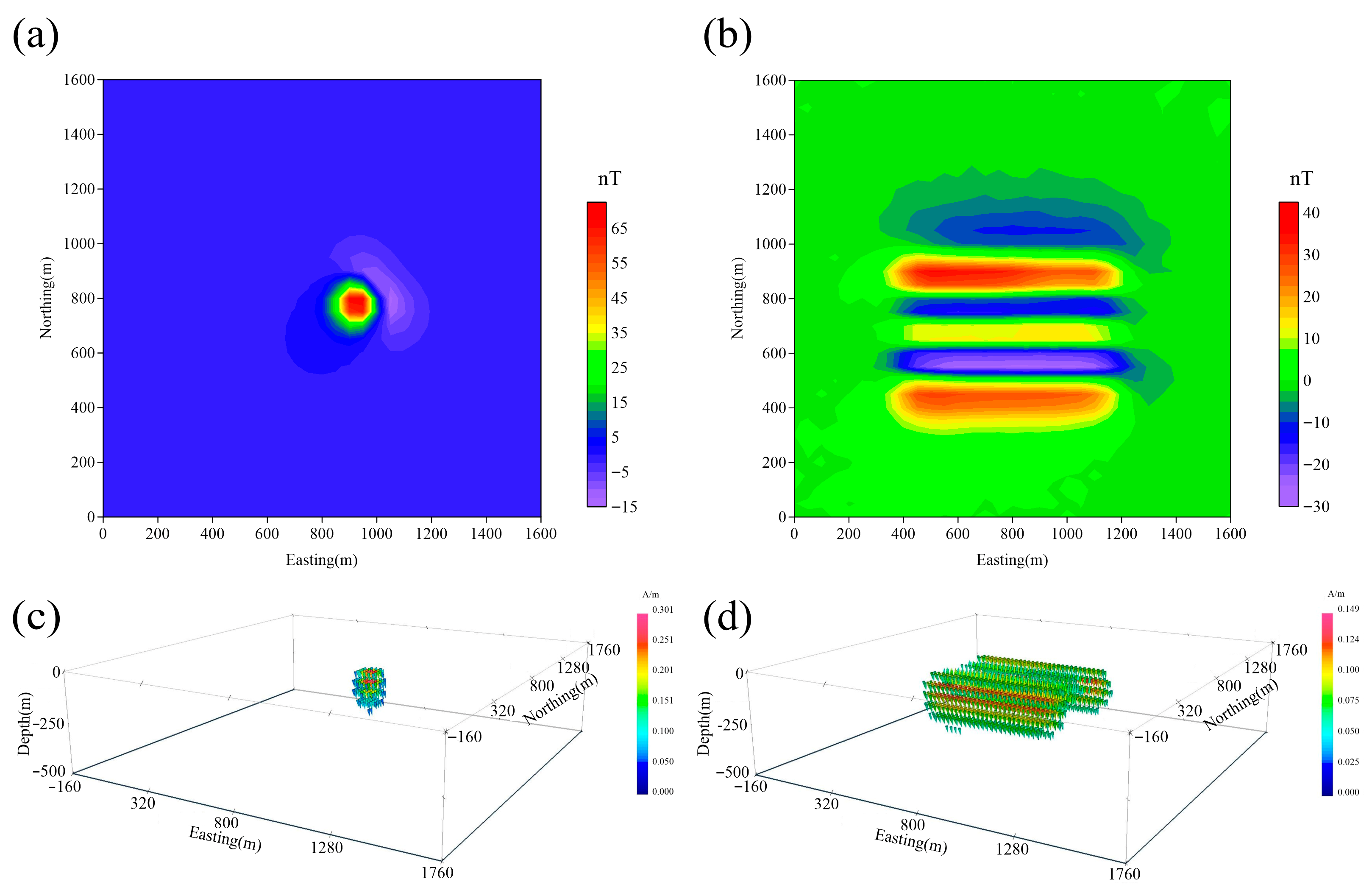

4. Synthetic Tests

5. Application to the South China Sea

5.1. Low-Rank Anomaly Separation

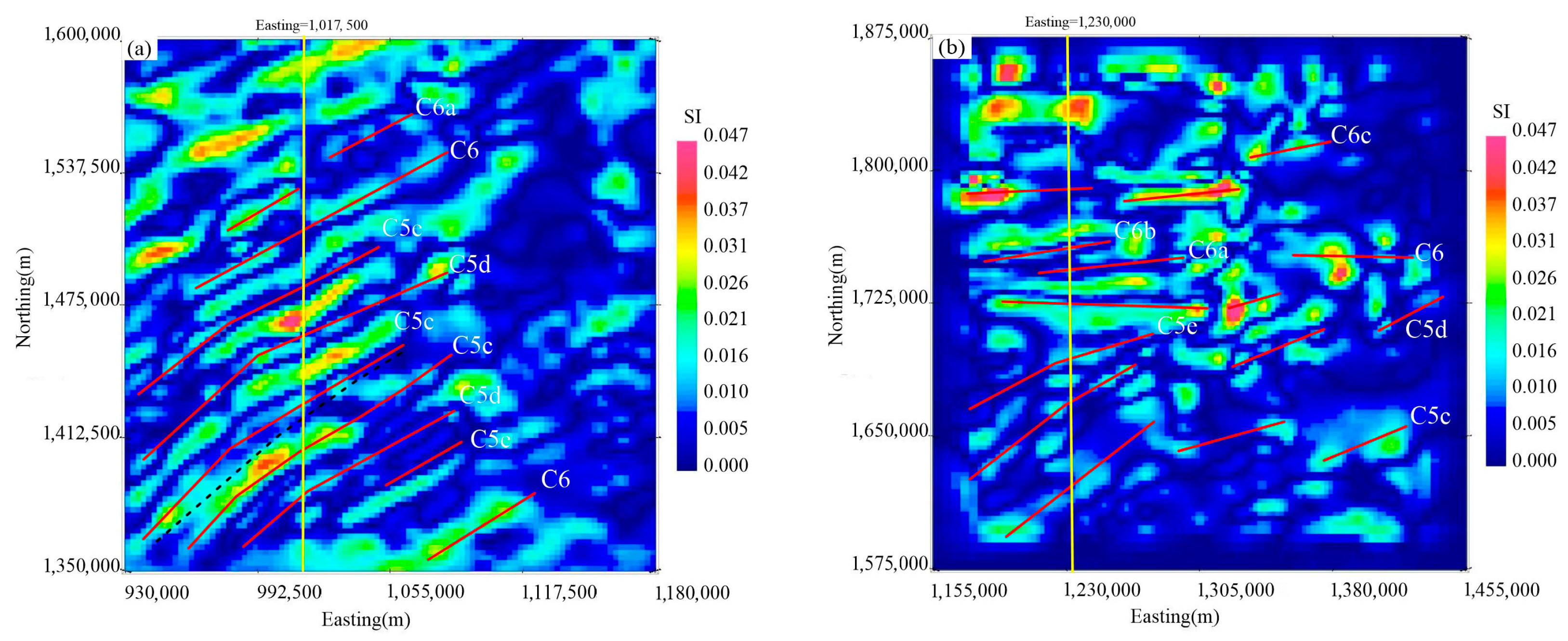

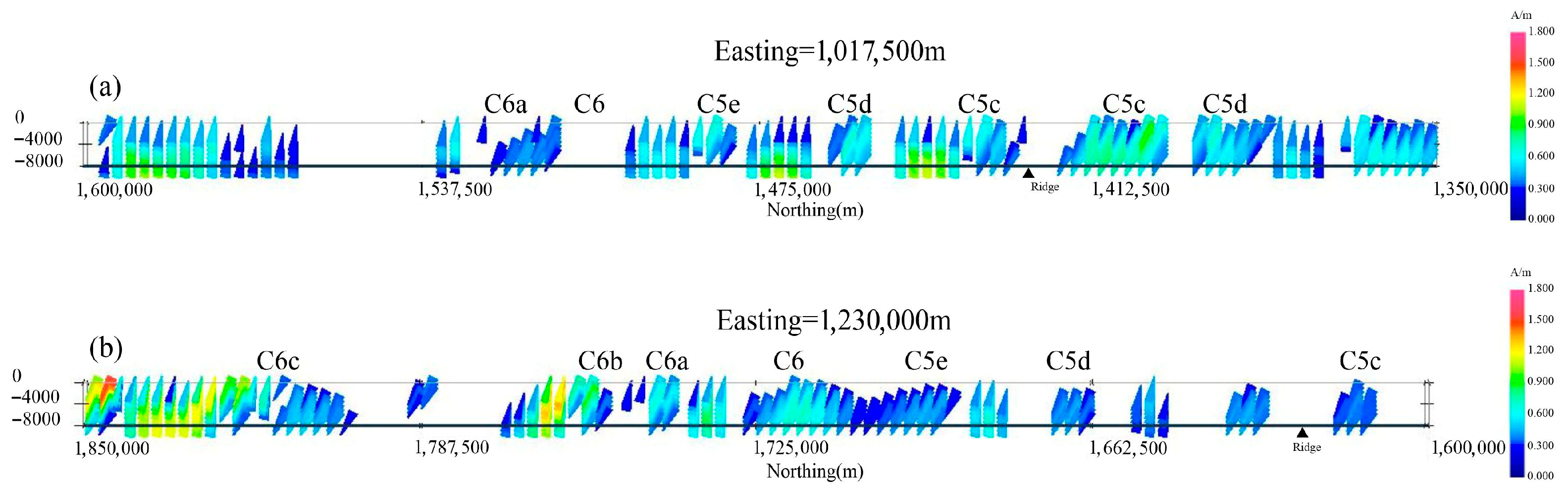

5.2. Oceanic-Crust Inversion Results

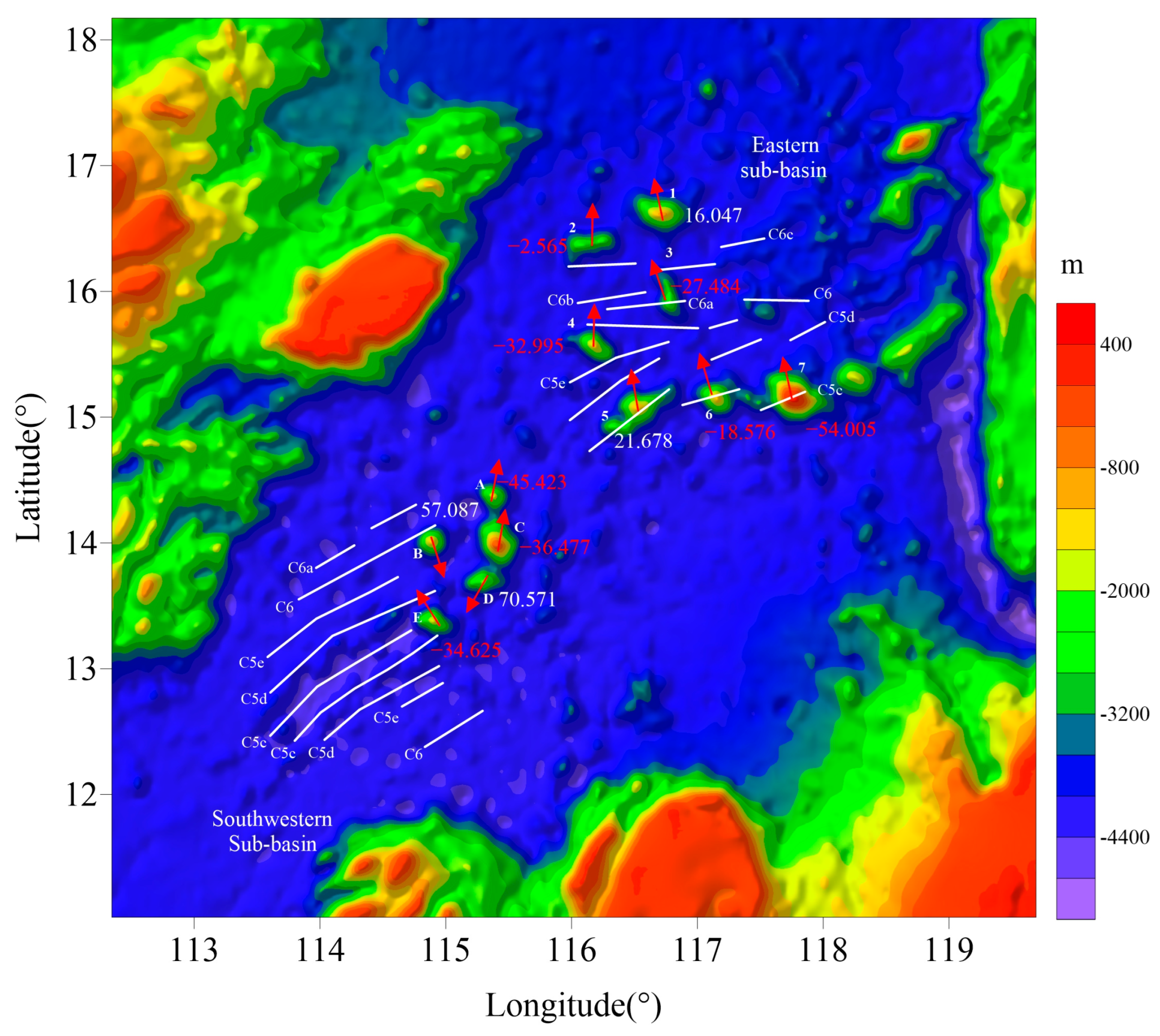

5.3. Seamount Inversion Results

6. Discussion

6.1. Interpretation of Inverted Magnetization

6.2. Inter-Sub-Basin Comparison

6.3. Seamount Magnetization Patterns

6.4. Uncertainty Assessment

6.5. Tectonic Evolution Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taylor, B.; Hayes, D.E. The tectonic evolution of the South China Sea Basin. In Geophysical Monograph Series; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 1980; Volume 23, pp. 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Briais, A.; Patriat, P.; Tapponnier, P. Updated interpretation of magnetic anomalies and seafloor spreading stages in the South China Sea: Implications for the Tertiary tectonics of Southeast Asia. J. Geophys. Res. 1993, 98, 6299–6328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppers, A.A.P. On the 40Ar/39Ar dating of low-Potassium Ocean crust basalt from IODP Expedition 349, South China Sea. In Proceedings of the AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, San Francisco, CA, USA, 15–19 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Xu, X.; Lin, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Q.; Kulhanek, D.K.; Wang, J.; et al. Ages and magnetic structures of the South China Sea constrained by deep tow magnetic surveys and IODP Expedition 349. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2014, 15, 4958–4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Xia, S.; Huang, X.; Jie, X.; Li, C.; Ding, W.; Zhou, Z. New breakthroughs in ocean drilling and frontier research on marine geology and geophysics in the South China Sea. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2019, 41, 125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, B. Magnetic anomalies due to prism-shaped bodies with arbitrary polarization. Geophysics 1964, 29, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Oldenburg, D.W. 3-D inversion of magnetic data. Geophysics 1996, 61, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, S.; Liu, S.; Zhu, R.; Xu, X.; Gao, H.; et al. Tectonic Geology of the South China Sea and Adjacent Areas; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Shearer, S.; Haney, M.; Dannemiller, N. Comprehensive approaches to 3D inversion of magnetic data affected by remanent magnetization. Geophysics 2010, 75, L1–L11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelièvre, P.; Oldenburg, D. A 3D total magnetization inversion applicable when significant, complicated remanence is present. Geophysics 2009, 74, L21–L30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, J. 3D magnetization inversion using fuzzy c-means clustering with application to geology differentiation. Geophysics 2016, 81, J61–J78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, Y. Magnetization clustering inversion—Part 1: Building an automated numerical optimization algorithm. Geophysics 2018, 83, J61–J73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, Y. Magnetization clustering inversion—Part 2: Assessing the uncertainty of recovered magnetization directions. Geophysics 2019, 84, J17–J29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Hu, X.; Liu, S.; Li, H.; Zuo, B. Can targeted source information be extracted from superimposed magnetic anomalies? J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2022JB024279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, A.; Reemst, P.; Henstra, G.; Gozzard, S.; Ray, A. Rifting of the South China Sea: New perspectives. Pet. Geosci. 2010, 16, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, J.; Ding, W.; Franke, D.; Yao, Y.; Shi, H.; Pang, X.; Cao, Y.; Lin, J.; Kulhanek, D.K.; et al. Seismic stratigraphy of the central South China Sea basin and implications for neotectonics. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2015, 120, 1377–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Song, T. Magnetic recording of the Cenozoic oceanic crustal accretion and evolution of the South China Sea basin. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2012, 57, 3165–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shi, X.; Zhou, Z.; Li, J.; Geng, J.; Chen, B. Depths to the magnetic layer bottom in the South China Sea area and their tectonic implications. Geophys. J. Int. 2010, 182, 1229–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Galatu, J.; Dai, X. Investigating the gravity variable-density inversion method in complex geological settings: Application to the South China Sea. J. Geophys. Eng. 2025, 22, 1700–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Xu, S.; Li, Z. Inversion of heterogeneous magnetism for seamounts in the South China Sea. J. Ocean Univ. Qingdao 2002, 32, 926–934. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, N.; Sun, Z.; Lin, J.; Li, C.-F.; Xu, X. Dating seafloor spreading of the southwest sub-basin in the South China Sea. Gondwana Res. 2023, 120, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J. Study on Magnetic Differences in the South China Sea Basin Based on Magnetic Anomaly Vector Clustering Inversion. Master’s Thesis, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Seamount ID | Seamount Name | Sub-Basin | Inclination (°) | Declination (°) | Peak Intensity (A/m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Zhongnanbei | Southwestern | −45.423 | 10.672 | 1.645 |

| B | Longbei | Southwestern | 57.087 | 162.215 | 0.755 |

| C | Zhongnan | Southwestern | −36.477 | 9.963 | 1.330 |

| D | Zhongnannan | Southwestern | 70.571 | −150.182 | 1.201 |

| E | Longnan | Southwestern | −34.625 | −32.606 | 0.972 |

| 1 | Xianbei | Eastern | 16.047 | −11.881 | 5.285 |

| 2 | Shixing | Eastern | −2.565 | 0.851 | 2.546 |

| 3 | Xiannan | Eastern | −27.484 | −18.996 | 1.312 |

| 4 | Zhangzhong | Eastern | −32.995 | 1.199 | 2.457 |

| 5 | Zhenbei | Eastern | 21.678 | −9.635 | 2.679 |

| 6 | Huangyan | Eastern | −18.576 | −16.671 | 2.133 |

| 7 | Huangyan island | Eastern | −54.005 | −12.265 | 5.083 |

| Parameter | Southwestern Sub-Basin | Eastern Sub-Basin |

|---|---|---|

| Clustering centers (I, D) | (−79.8°, 148.8°) and (59.3°, −18.2°) | (−69.9°, 172.6°) and (60.7°, −8.6°) |

| Magnetization range | 0.40–1.80 A/m | 0.28–1.52 A/m |

| Modal intensity | 0.40 A/m | 0.35 A/m |

| Lineation strike | NE–SW | NE–SW and E–W |

| Stripe spacing | Narrow | Wide |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wan, J.; Li, S.; Ji, Z. Tectonic Inversion of the SCS from 3-D Magnetization Vector Clustering: Evidence for Differential Rotation and Ridge Jump. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13126. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413126

Wan J, Li S, Ji Z. Tectonic Inversion of the SCS from 3-D Magnetization Vector Clustering: Evidence for Differential Rotation and Ridge Jump. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13126. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413126

Chicago/Turabian StyleWan, Juechang, Shuling Li, and Zhe Ji. 2025. "Tectonic Inversion of the SCS from 3-D Magnetization Vector Clustering: Evidence for Differential Rotation and Ridge Jump" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13126. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413126

APA StyleWan, J., Li, S., & Ji, Z. (2025). Tectonic Inversion of the SCS from 3-D Magnetization Vector Clustering: Evidence for Differential Rotation and Ridge Jump. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13126. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413126