Abstract

Sport horse feeding robots face significant challenges in achieving precise navigation within complex stable environments. Uneven terrain and frequently moist ground often cause drive wheel slippage, resulting in path deviation and cumulative pose errors that compromise feeding accuracy and operational efficiency. To address this challenge, an enhanced Dynamic Window Approach (DWA) path planning framework, which integrates an automatic drift correction module based on an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) and a two-stage cascade proportional–integral–derivative (PID) controller, is proposed in this paper. This enhanced DWA enables precise yaw adjustment while preserving the native velocity sampling and trajectory evaluation framework of conventional DWA. Field validations were conducted through ten independent trials along a fixed 28 m feeding route in an actual sport horse feeding environment to quantitatively evaluate the robot’s path deviation and yaw angle stability. The results demonstrated that the enhanced algorithm reduced the standard deviation of path deviation from 0.161 m to 0.144 m (10.56% improvement) and decreased yaw angle standard deviation from 2.19° to 1.74° (20.55% reduction in angular oscillation). These improvements validated the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm in mitigating slippage-induced pose drift and significantly improving the locomotion capability of robots for sport horse feeding within stable environments.

1. Introduction

With the continuous growth of the global population and the rapid increase in food demand, traditional agriculture is facing prominent issues such as labor shortages and low production efficiency. To effectively address these challenges, agriculture is progressively transitioning into a digital and intelligent era, known as smart agriculture. Agricultural robots are capable of replacing a large number of repetitive and labor-intensive tasks in agricultural production, such as environmental monitoring, precision operations, and automated farming [1,2]. Particularly in the livestock field, intelligent feeding robots have emerged as a research hotspot. Their applications can significantly improve animal welfare, reduce labor costs, and drive the livestock industry towards enhanced efficiency and automation [3].

Agricultural environments demonstrate significantly greater unstructured complexity than industrial environments, featuring variable terrain, irregular infrastructure arrangements, and dynamic obstacles (including humans and animals) [4,5,6]. Consequently, the autonomous operation of agricultural robots critically relies on robust navigation technology [2,7]. A typical navigation framework comprises localization, mapping, and path planning modules [3,6,8]. Path planning, which directly determines a robot’s ability to reach target locations safely and efficiently in complex environments, is widely recognized as the pivotal element of navigation.

Path planning methods for current agricultural robots can be broadly classified into global path planning and local path planning [3,7]. Global path planning computes the globally optimal route on pre-built or known static maps, and three principal algorithms include Dijkstra, A*, and Rapidly-exploring Random Tree (RRT). Dijkstra obtains the strict global shortest path by traversing all reachable nodes in weighted graphs and has been applied in scenarios such as a pesticide-spraying robot that must visit every greenhouse lane [9] and a mountain vineyard transporter negotiating terraced terrain while minimizing travel cost [10]. A* reduces redundant node expansion by incorporating heuristic functions based on Dijkstra and has been widely used for rapid replanning in orchard mowers that need full-coverage cutting while circumnavigating trees [11] and in steep-slope vineyards where trajectories account for center-of-mass stability [12]. RRT and its variants, which incrementally expand a tree from a start point toward randomly sampled configurations, are suitable for open environments with undulating terrain or incomplete maps; representative applications include an orchard robot that shortens trajectories on uneven ground with HPS-RRT* [13], a Quick-RRT*-derived method that trims both path length and planning time for obstacle-dense orchards [14], and the IKB-RRT algorithm [15], which enhances path planning for nonholonomic orchard robots by incorporating an improved artificial potential field, a kinematically constrained node expansion strategy, and a dual-tree path-smoothing method to generate shorter, smoother, and faster-planned trajectories in unstructured environments. Local path planning relies on on-board sensors to perceive the surrounding environment in real time, generating collision-free trajectories over a limited prediction window. Widely used algorithms are the artificial potential field (APF) [16], Dynamic Window Approach (DWA) [17], and timed elastic band (TEB) [18]. The APF constructs a composite potential field by treating the goal as an attractive source and obstacles as repulsive sources. Its agricultural applications include enabling an apple-picking manipulator to weave through dense foliage without bruising fruit [19], allowing a greenhouse inspection vehicle to follow waypoints while smoothly avoiding crop rows and irrigation pipes by coupling the APF with Hector-SLAM [20], enhancing UGV navigation through a learning-based APF algorithm [21], which integrates a lightweight convolutional neural network with a classical APF to enable strategy-selectable and adaptable local navigation in dynamic agricultural environments, and improving real-time collision avoidance in cluttered orchards via an APF method that incorporates harmonic potential fields with dynamic window constraints [22]. The DWA comprehensively addresses kinematic constraints by sampling candidate linear velocity and angular velocity commands in velocity space and evaluating them with a weighted objective. This enables a greenhouse mobile platform to follow a Dijkstra-based global path and dodge emergent obstacles among tomato rows [23]; it also facilitates precise path tracking and obstacle avoidance for a multifunctional pepper-harvesting robot operating in structured greenhouse environments [24] and supports smoother and more efficient navigation of electric crawler tractors via an improved A*–DWA fusion framework tailored for constrained greenhouse conditions [25]. The TEB optimizes motion plans by transforming a global path into a time-stamped elastic band that balances spatial deformation and temporal consistency. Typical applications include coordinating two heterogeneous vineyard robots that generate smooth S-shaped paths in narrow grape rows [26], an improved TEB local planner that lets an autonomous ground vehicle hug warehouse walls during sharp turns, cutting planning time and energy consumption [27], and a greenhouse pepper-harvesting robot that integrates perception with TEB-based local planning to navigate efficiently and safely through dense crop rows [28]. The path planning methods discussed above are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Path planning methods in agricultural robots.

To ensure robust and adaptive navigation, agricultural robots commonly employ a hierarchical planning architecture. A global trajectory is initially constructed using an algorithm such as Dijkstra, A*, or RRT. Then, based on real-time sensory input, local planners (e.g., APF, DWA, TEB) refine the path dynamically to address immediate environmental changes. This design enhances responsiveness while preserving global path consistency [24,30,31]. Among commonly used local planners (e.g., APF, DWA, and TEB), the APF is lightweight but may suffer from local minima in cluttered scenes, while the TEB typically yields smoother and time-consistent trajectories through iterative optimization at a higher computational cost. The DWA provides a good balance between real-time feasibility and kinematic constraint handling via velocity sampling, but it can become sensitive to slip-induced pose drift and sensor/odometry errors in irregular, low-friction environments. Global planners such as RRT/RRT* primarily optimize a collision-free global route on a map, but they typically assume reliable execution and do not provide execution-level feedback to correct slip-induced yaw drift; docking-level pose accuracy at feeding stations must be enforced at the local planning/control layer, which motivates our IMU-driven drift correction and cascaded PID enhancement. Therefore, this work focuses on improving DWA for horse-barn feeding tasks by coupling the standard DWA velocity-sampling framework with an IMU-driven drift correction module and cascaded PID control, aiming to enhance robustness on wet/uneven floors while retaining real-time performance.

Sport horses, characterized by superior agility, strength, and responsiveness, are widely used in professional equestrian sports and require strict nutritional management for optimal performance and recovery. This has prompted a growing interest in automated feeding technologies capable of delivering accurate, programmable feeding amounts based on their physiological needs [32]. Feeding robots for sport horses must accurately reach designated feeding points within complex stable environments where uneven terrain and frequent moisture often cause drive wheel slippage, resulting in path deviation and cumulative pose errors [33,34]. Conventional local path planning methods fail to satisfy the rigid pose constraints required for each feeding task [35]. To address this challenge, this paper proposes an enhanced-DWA path planning framework integrating a drift correction module based on an Inertial Measurement Unit and a dual-loop proportional–integral–derivative (PID) controller [36]. This closed-loop mechanism continuously monitors and adjusts the robot’s yaw orientation, thus suppressing slippage-induced pose drift while substantially improving navigation precision and feeding reliability.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the conventional DWA and details the proposed enhancements, including the integration of an IMU-based drift correction module and a cascade PID controller. Section 3 presents the experimental setup, procedures, and results for evaluating path deviation and yaw-angle stability. Section 4 summarizes the conclusions, discusses limitations, and outlines future work to further improve algorithm robustness and generalizability in agricultural environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conventional DWA Algorithm

2.1.1. Algorithm Overview

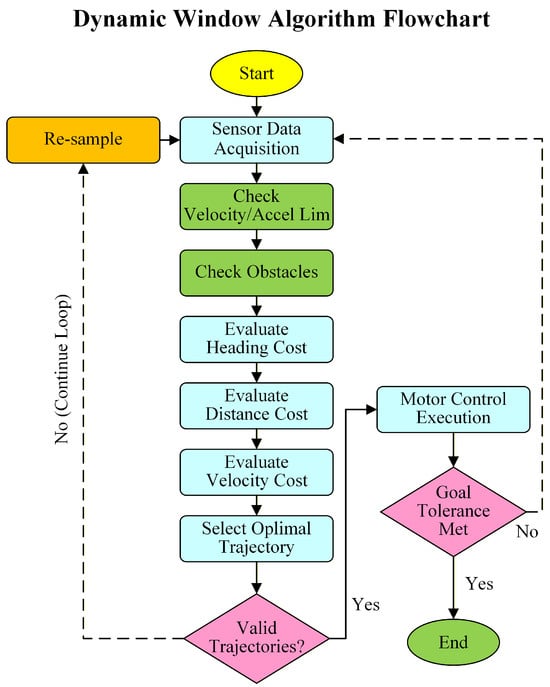

The DWA is a classical local path planning technique widely used in autonomous navigation and obstacle avoidance systems. By continuously adjusting the velocity of a robot in dynamic environments, the DWA streamlines path planning and improves obstacle avoidance performance. The algorithm constructs a velocity window based on the current motion state of the robot and its perceived surroundings, samples candidate velocities within this window, evaluates the resulting trajectories, and selects the most suitable to achieve local path planning.

The core principle of the DWA is to construct a feasible velocity space from the current speed, acceleration, and perceived environmental data of the robot. This space is bounded by constraints that include the maximum speed and acceleration of the robot and its distance from nearby obstacles. By sampling different velocity pairs within this admissible window, the DWA simulates several candidate trajectories and evaluates them with an objective function that balances obstacle avoidance, proximity to the goal, and smoothness of the path. It then executes the trajectory that receives the highest score, which enables the robot to move safely and stably through complex and dynamic environments.

2.1.2. Principle of Algorithm

In the DWA, the admissible velocity set is bounded by the kinematic limits of the robot and by real time environmental constraints. The maximum linear and angular speeds, the acceleration limits, and a specified obstacle clearance margin together define this velocity window and yield the candidate command set shown in Equation (1). Here, v and denote the translational and rotational velocity components, respectively.

Moreover, the admissible velocities must satisfy acceleration constraints. In each time step, the linear velocity v and the angular velocity describe the robot’s forward and rotational motion, respectively. Their derivatives and —representing the robot’s linear and rotational accelerations—must remain within predefined limits, as formalized in Equation (2). Here, denotes the maximum allowable linear acceleration, and denotes the maximum allowable angular acceleration.

Concurrently, the feasible velocity set is further constrained by a minimum safety clearance to surrounding obstacles in order to preclude collisions, as formalized in Equation (3).

Let denote the minimum distance between any candidate command and the nearest obstacle, and let denote the required safety buffer.

The admissible velocity set is therefore defined as the intersection of the three constraint subspaces introduced above, as formalized in Equation (4).

After delineating the admissible velocity space, the DWA samples each candidate velocity pair and propagates it through the kinematic model of the robot to generate a family of prospective trajectories. For a differential drive platform, the state evolution is predicted by Equations (5)–(7).

Here, , , and denote the pose of the robot in the current time step; is the integration interval; v is the linear velocity; and is the angular velocity. By integrating these kinematic equations forward for each sampled command, the DWA predicts the motion associated with every velocity pair and then evaluates the resulting trajectories.

Trajectory evaluation is a pivotal stage in the DWA. Its purpose is to identify a candidate path that ensures collision avoidance while promoting efficient progress toward the goal. Each predicted trajectory is assigned a composite cost based on several criteria, most commonly the heading error, the minimum obstacle clearance, and the suitability of the commanded linear velocity and angular velocity. The trajectory that minimizes this aggregate cost is selected for execution. A representative cost function is formulated in Equation (8).

In Equation (8), H measures the heading deviation, D denotes the minimum obstacle clearance, and V evaluates the dynamic suitability of the commanded linear velocity and angular velocity. The terms , , and are the weighting coefficients assigned to these respective components.

The heading metric H quantifies the angular deviation between the endpoint of the trajectory and the direction toward the goal, as defined in Equation (9).

Here, and denote the Cartesian coordinates of the goal, and denote the coordinates of the trajectory endpoint, and denotes the orientation at the endpoint.

The distance metric D quantifies the safety clearance between the candidate trajectory and nearby obstacles, as expressed in Equation (10).

Here, denotes the Euclidean distance between trajectory point i and the surrounding obstacles.

The velocity metric V evaluates the kinematic suitability of a candidate trajectory. Greater commanded linear velocity and angular velocity generally reduce the time required to reach the goal, but they also increase the likelihood of collision.

Ultimately, the DWA combines the individual metric scores into a composite cost and selects the trajectory with the lowest overall value as the optimal path. The selected trajectory ensures sufficient obstacle clearance while maintaining efficient movement toward the goal, thereby enabling stable and safe operation of the robot in complex and cluttered environments.

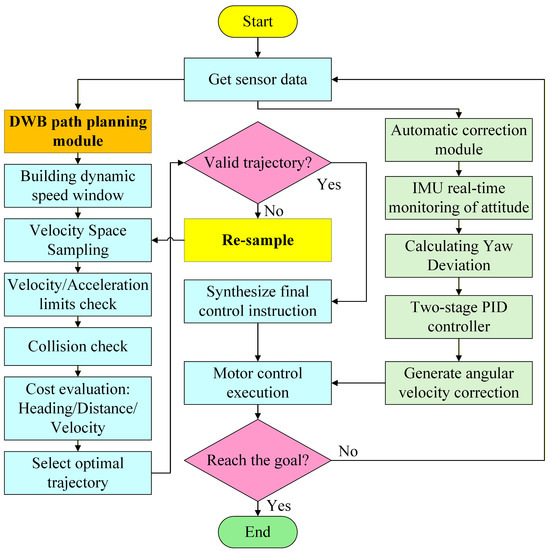

The procedural flow of the conventional DWA algorithm is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of conventional DWA algorithm.

2.2. Enhanced DWA Algorithm

Although the classical DWA is widely applied in robotic path planning, its adaptability in irregular and time-varying environments remains limited. In horse barns, uneven and often wet floors, randomly placed obstacles, and task-driven environmental changes frequently lead to wheel slip and rapid pose drift. Under such conditions, conventional DWA planners rarely meet the centimetre-level pose tolerances required at each feeding station, which compromises both navigation accuracy and operational efficiency. To overcome these limitations, we propose an enhanced DWA framework that integrates an IMU-driven drift correction module and a cascaded PID controller into the standard velocity sampling architecture. This design significantly improves path tracking robustness in highly dynamic and low-friction environments.

Beyond the conventional DWA, existing studies improve local navigation by (i) modifying cost terms/weights in sampling-based planners, (ii) fusing global–local planning strategies, or (iii) adopting optimization-based local planners (e.g., TEB). These approaches are effective in many agricultural settings, yet the slip-induced yaw drift and rapid pose deviation commonly observed in horse barns (wet/uneven floors) may still degrade docking-level accuracy at feeding stations. To isolate the contribution of our IMU-based drift correction and cascaded PID coupling, the experiments in this paper used the conventional DWA as the primary baseline, while a broader comparison with representative planners and studies is provided as a literature-based discussion.

The principal innovation of the enhanced DWA lies in the integration of an automatic drift correction module that fuses IMU feedback with a two-stage cascade PID controller for real-time pose rectification. This integration ensures stable operation on uneven terrain and in dynamic environments.

2.2.1. Algorithm Overview (Enhanced DWA)

Building on the conventional DWA, the proposed variant addresses its path planning deficiencies by embedding an automatic drift correction module. In the classical scheme, a dynamic velocity window is constructed based on the instantaneous linear velocity, angular velocity, and acceleration constraints of the robot. Admissible velocity pairs within this window are then sampled to generate a set of candidate trajectories. Each trajectory is evaluated using a composite cost function, and the one with the lowest cost is selected for execution, thereby ensuring both obstacle avoidance and goal tracking.

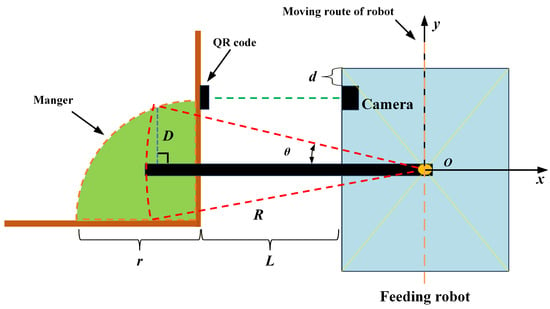

However, the conventional DWA relies on a predefined cost function with fixed weighting factors. In time-varying environments, especially horse barns with irregular terrain and scattered obstacles, this static formulation provides limited adaptability and leads to significant tracking errors. Once the heading deviation exceeds a predefined threshold, the robot fails to deposit feed at the designated location, thereby jeopardizing task completion. The definition of the feeding robot deviation angle is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Determination of heading deviation based on QR code detection in feeding task.

To overcome this limitation, the enhanced DWA incorporates an automatic drift correction module that continuously fuses real-time feedback from the Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU; CMP10A, Shenzhen Yahboom Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) with a two-stage cascade PID controller to fine-tune the heading of the robot. This augmentation significantly improves path tracking accuracy and ensures stable operation on uneven terrain and in dynamic environments.

2.2.2. Enhanced Method

Within the enhanced DWA, the primary innovation is the integration of an automatic drift correction module, which is essential for maintaining path fidelity over irregular terrain. This module combines an IMU with a two-stage cascade PID controller. The fusion of sensor data and control logic continuously monitors pose deviations caused by surface unevenness or moving obstacles and compensates for them in real time. As a result, the robot is able to follow its prescribed path with improved stability throughout task execution.

IMU processing and synchronization: The IMU streams the yaw angle and yaw rate at 200 Hz. To reduce high-frequency noise and ensure consistent timing with the controller loop, the raw yaw/yaw rate signals are (i) filtered using a first-order low pass, (ii) unwrapped to avoid discontinuities, and (iii) time-aligned to the DWA control cycle by downsampling to the controller rate.

In the proposed scheme, an onboard IMU first provides real-time estimates of roll, pitch, and yaw to the cascaded PID loop. These measurements serve as feedback for computing corrective commands for both orientation and angular velocity. The precisely tuned PID controllers enable the robot to respond almost instantaneously to pose disturbances caused by uneven terrain or moving obstacles, thereby preserving path accuracy and ensuring uninterrupted task execution.

(1) IMU module

Acting as the keystone of the automatic drift correction module, the IMU uses its onboard accelerometers and gyroscopes to monitor attitude changes in real time. It streams orientation, angular velocity, and linear acceleration data—measurements that are essential for the attitude compensation layer of the planning loop. Guided by this continuous feedback, the controller adjusts the motion of the robot in proportion to the detected pose deviation, thereby maintaining the correct attitude throughout execution.

The IMU provides not only real-time attitude feedback but also continuous monitoring of motion deviations during path execution, supplying critical input to the downstream PID controller. In doing so, it enables effective compensation for errors caused by uneven terrain or dynamic obstacles encountered during transit.

(2) Two-stage cascade PID algorithm

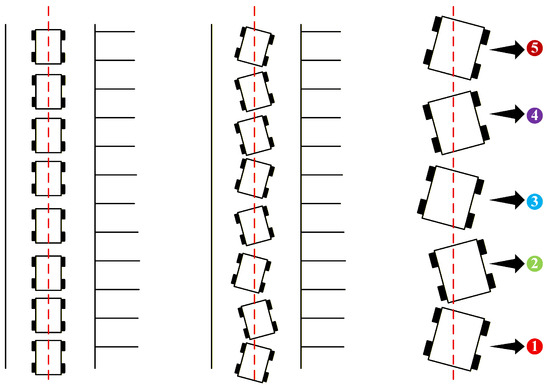

In the current horse feeding mission, the desired pose evolution of the robot is illustrated in Figure 3 left. However, the uneven and low-friction floor of the barn, along with the constantly changing layout of obstacles, highlights the limited drift rejection capability of the classical DWA, resulting in significant trajectory deviation during execution. As a result, the robot is unable to follow the prescribed path accurately; its actual motion is shown in Figure 3 center.

Figure 3.

(left) Desired path-following pose of robot. (center) Actual path-following pose of robot. (right) Actual tracking process diagram. The red line denotes the reference trajectory; numbers indicate the sampling order.

As summarized in Table 2, we compare the proposed method with representative baselines.

Table 2.

IMU signal filtering and synchronization settings.

Figure 3 right illustrates a simplified tracking sequence: red denotes nominal tracking, green marks the onset of deviation, blue indicates the moment when the maximum deviation threshold is exceeded, and purple shows the subsequent reduction in error. In practice, the conventional DWA does not initiate correction at the onset of deviation; instead, it responds only after the threshold is crossed. This delay leads to excessive overshoot and oscillation, significantly reducing tracking efficiency.

To mitigate this deficiency, an automatic drift correction module is inserted between the navigation layer and the chassis velocity interface. This module continuously streams gyroscope data from an onboard IMU and analyzes the instantaneous attitude—angles and angular rates—to detect heading deviations. Once a deviation is detected, the system promptly activates the correction routine to steer the robot back toward the planned path. In terms of implementation, a two-stage cascade PID controller is tightly integrated with the DWA local planner, significantly improving path tracking precision and stability in complex and irregular environments.

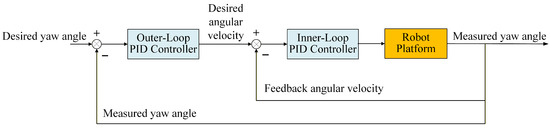

The cascaded PID scheme uses inner and outer control loops to regulate both the transient response and the steady-state performance of the system, thereby stabilizing the attitude of the robot. The controller architecture is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Two-stage cascade PID control.

To suppress attitude drift during path following, a two-stage cascade PID scheme is adopted. Working in coordination, the outer and inner loops provide complementary regulation. The inner loop aggressively tracks the commanded angular velocity, delivering a fast dynamic response, while the outer loop shapes the attitude by driving the robot toward its desired orientation. Together, the dual controllers enable simultaneous control of angular velocity and attitude, ensuring rapid and stable convergence to the target pose.

The operating principle of the cascaded inner and outer PID control loop is formalized by the following equations:

To compensate for slip-induced attitude drift on wet/uneven barn floors, we introduce an IMU-driven cascaded PID controller to generate a yaw rate correction that is fused with the DWA command before execution. Let denote the measured yaw angle from the IMU, and let denote the desired yaw angle implied by the selected DWA trajectory (i.e., the heading direction of the optimal local trajectory).

The outer-loop PID regulates the yaw angle tracking error and outputs a reference yaw rate:

The inner-loop PID then tracks this reference yaw rate using the measured yaw rate (from IMU/filtered estimate) and outputs the yaw rate correction:

Here, , , and denote the proportional, integral, and derivative gains, respectively. The proportional term responds to the instantaneous error, the integral term compensates accumulated bias (e.g., slip-induced drift), and the derivative term dampens fast oscillations. In our implementation, represents an angular velocity compensation (yaw rate correction, in rad/s) that is fused with the yaw rate command generated by the DWA:

where denotes saturation with respect to the platform yaw rate limits.

We keep the original velocity sampling, trajectory rollout, and scoring functions of the (Nav2-based) DWA local planner unchanged. The only modification is applied after the best command is selected: the drift correction module computes from IMU feedback and the cascaded PID and then fuses it into the outgoing angular command as before publishing cmd_vel (Equation (15)). The correction runs on Jetson Orin Nano (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA), while low-level execution is handled by the real-time controller (ESP32-S3-N8R8; Espressif Systems, Shanghai, China).

We adopt cascaded PID due to its low computational overhead and ease of field tuning for real-time control. Model-based alternatives (e.g., MPC) can explicitly handle constraints but typically require a more accurate system model and higher computation, which is beyond the scope of this work.

We tuned the cascaded PID in two stages. First, the inner loop (yaw rate loop) was tuned to track step changes in ref with minimal overshoot under no-load/bench conditions. Second, the outer loop (yaw angle loop) was tuned on site to correct steady slip-induced yaw drift while maintaining stable transient response. The final gains used in all experiments are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Final gains of cascaded PID controller.

With this architecture, the inner loop rapidly adjusts the angular velocity of the robot in response to instantaneous attitude error, while the outer loop drives the yaw angle to asymptotically converge on the target pose. This ensures precise path tracking. The fine-grained regulation provided by the cascaded PID pair enables the robot to maintain high-accuracy motion even over irregular terrain and in the presence of dynamic obstacles.

The algorithmic flowchart of the enhanced DWA is depicted in Figure 5. This flowchart integrates the enhanced drift correction mechanism into the classical DWA framework, highlighting the collaboration between the motion planning module and the real-time attitude correction system. On the left, the IMU continuously monitors the robot’s posture, computes the yaw deviation, and activates a two-stage cascade PID controller to generate corrective angular velocity commands. These corrections are fused with the standard DWA outputs on the right, which involve velocity sampling, trajectory prediction, and evaluation. Together, the combined syste m ensures more stable and accurate path tracking even under challenging terrain conditions.

Figure 5.

Flowchart of enhanced DWA algorithm.

3. Results

The effectiveness and advantages of the proposed enhanced algorithm were validated through experimental testing. The primary objective of these experiments was to evaluate improvements in path deviation, trajectory smoothness, and angular stability under real-world conditions, using empirical data and practical scenarios.

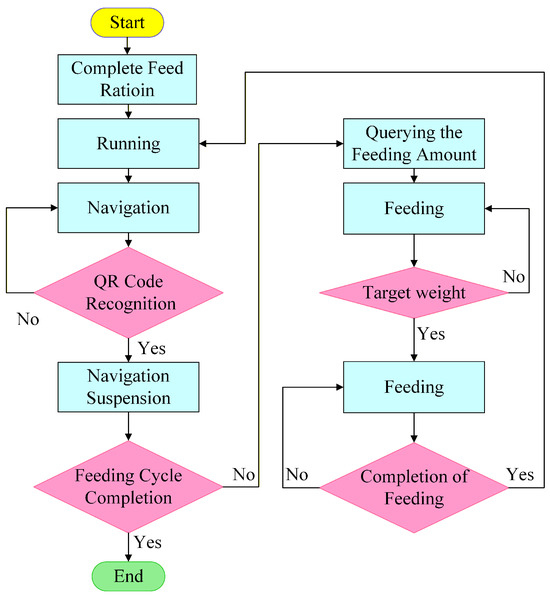

The operational workflow of the horse feeding robot is as follows. The robot first completes feed loading and then begins its task upon activation. Using the navigation module, it performs path planning and autonomously executes obstacle avoidance when necessary. If navigation proceeds without interruption, the robot identifies a QR code located at the barn entrance to verify the designated feeding station. Upon successful recognition, it transitions into the feeding routine and dispenses feed at the confirmed target location.

After completing the initial feeding attempt, the robot verifies task completion by comparing the delivered feed quantity against the predefined target using sensor feedback. If the dispensed amount is insufficient, the robot continues operation until the required quantity is achieved. Once the feeding task is fulfilled, the system returns to its initial state, marking the successful completion of the routine.

The feeding workflow of the horse feeding robot is illustrated in Figure 6. This workflow outlines the complete feeding cycle, from task initiation to feeding completion. The process begins with the robot preparing the full feed ration and entering the navigation state. Upon recognizing the QR code at the feeding site, it halts navigation and initiates feeding. The system then verifies whether the dispensed quantity meets the target weight; if not, the feeding continues iteratively. Once the task criteria are fulfilled, the robot returns to its initial state, ready for the next cycle. The diagram also highlights the conditional transitions that ensure task reliability and autonomous control throughout the process.

Figure 6.

Feeding workflow diagram of horse feeding robot.

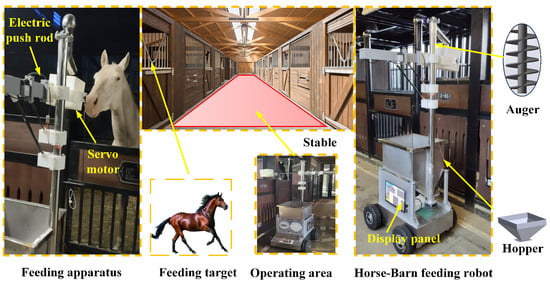

Figure 7 presents the horse feeding robot and its operational environment, including the feeding apparatus, activity area, and representative navigation paths within the barn. The figure illustrates key components of the experimental setup in the horse barn. On the left, the feeding apparatus employs an electric push rod and servo motor to dispense precise feed quantities. In the center, the stable environment is characterized by narrow corridors and uneven flooring, posing challenges for reliable robot navigation. The feeding target is a representative sport horse, highlighting the real-world application context. On the right, the autonomous horse-barn feeding robot is shown, equipped with a QR-code-based positioning system, onboard display unit, auger, and hopper—supporting accurate identification, navigation, and feed delivery. This comprehensive configuration forms the foundation for testing the proposed enhanced DWA algorithm under practical operating conditions.

Figure 7.

Stable feeding robot and actual feeding environment.

3.1. Experimental Setup and Environment

Based on the experimental environment and hardware/software setup summarized in Table 4, the following experiments were designed. The first experiment, focused on path deviation, evaluated the ability of the robot to follow a predefined trajectory under complex and dynamic conditions, particularly on uneven terrain typical of equestrian facilities. The second experiment, targeting yaw angle stability, assessed the ability of the enhanced DWA algorithm to maintain consistent heading control in dynamic environments, ensuring that the robot sustained a stable motion direction throughout task execution.

Table 4.

Summary table of experimental setup and environment.

The stable floor presented spatially varying contact conditions (unevenness and intermittently moist/low-friction patches), which could cause wheel slip and rapid yaw drift during execution. To reflect realistic environmental variability while keeping the route and hardware unchanged, we conducted 10 independent trials and randomized the obstacle placement/configuration in each trial. Ten trials were selected as a practical trade-off between field-test cost and statistical robustness under real stable conditions.

3.2. Path Deviation Experiment

To assess the path tracking accuracy of the enhanced algorithm, ten independent trials were conducted along a fixed 28 m feeding route, extending from the feed silo exit to the designated feeding point. In each trial, only the positions of the obstacles were randomly adjusted, while all other conditions remained constant. The robot recorded its actual trajectory at a frequency of 25 Hz. A least squares method was used to fit the ideal reference line of the route, expressed as . The perpendicular distance from each recorded trajectory point to this line was then calculated.

The path deviation for each individual trial was quantified using the standard deviation metric , and the average value across all ten trials was computed to evaluate overall performance. The results showed that the conventional DWA produced an average deviation of 0.161 m, while the enhanced algorithm reduced it to 0.144 m—an overall improvement of 10.46%. The long-tail distribution of deviation errors also contracted significantly toward the 0–0.10 m range, effectively suppressing oscillations at the source.

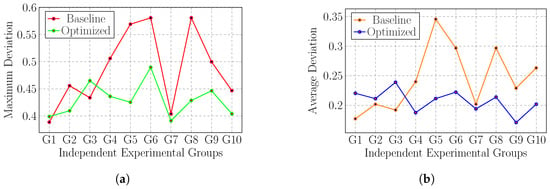

Figure 8 compares the path deviation performance of the baseline and optimized models over ten independent trials –. The maximum absolute deviation for trial j is defined as

where denotes the perpendicular distance from the i-th sample point to the ideal reference path in trial j, N is the total number of sampled points in that trial, is the absolute value of that distance, and is the largest such absolute deviation among all N points. The mean absolute deviation for trial j is given by

where represents the arithmetic mean of the absolute deviations over all sample points. From Figure 8, it is clear that the optimized DWA algorithm reduced both and in most of the trials, indicating smoother trajectories, closer adherence to the reference path, and effective suppression of oscillations at the source.

Figure 8.

Trajectory comparison between the conventional DWA baseline and the proposed enhanced DWA with IMU-based drift correction. (a) Maximum deviation comparison between baseline and optimized methods. (b) Average deviation comparison between baseline and optimized methods.

As summarized in Table 5, we compare the proposed method with representative baselines.

Table 5.

Trial-wise summary of path deviation and yaw stability.

As summarized in Table 6, we compare the proposed method with representative baselines.

Table 6.

Cross-trial statistics with 95% confidence intervals and paired tests.

3.3. Yaw Angle Stability Experiment

To further validate the effectiveness of attitude control, ten additional trials were conducted along the same route, with the heading angle of the robot recorded in real time. IMU data were filtered and temporally aligned with the trajectory points at 25 Hz. The standard deviation of the yaw angle, , was computed for each trial. The results showed that the conventional DWA produced an average of 2.19°, whereas the enhanced algorithm reduced it to 1.74°, reflecting a 20.55% decrease in angular fluctuation. These findings highlight the ability of the cascaded PID–IMU controller to suppress both low-frequency drift and high-frequency noise in robot orientation.

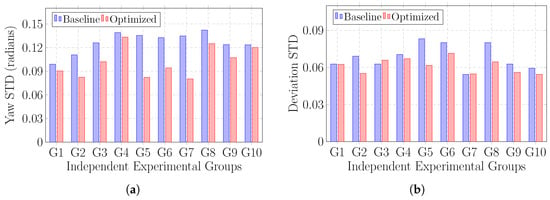

The experimental results demonstrate that the enhanced DWA significantly reduced yaw angle fluctuations, thereby improving the attitude stability of the robot during path tracking. A comparative analysis of the yaw angle standard deviations under both algorithms shows that the enhanced DWA produced markedly lower variation than the conventional method, confirming its superior performance in maintaining directional stability. The ten groups labeled G1 to G10 represent the individual experimental trials conducted under identical conditions. Figure 9a,b presents the standard deviation comparison for path deviation angle and yaw angle, respectively, under both algorithms—clearly illustrating the substantial improvement in yaw stability achieved by the proposed approach.

Figure 9.

Standard deviation analysis of yaw angle and path deviation with and without DWA enhancement. (a) Yaw STD (radians) comparison between baseline and optimized methods. (b) Deviation STD comparison between baseline and optimized methods.

We report the mean across 10 trials with 95% confidence intervals (t-distribution; ). To evaluate whether the improvement was consistent across trials, we conducted a paired test between baseline and enhanced methods on and (paired t-test; additionally, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed as a non-parametric check).

3.4. Section Summary

As shown in Table 7, the enhanced DWA algorithm—augmented with the automatic drift correction module—achieves notable improvements in both key metrics: path deviation and yaw angle stability. This advancement enables more accurate path tracking and pose control in dynamic and unstructured environments such as horse barns, laying a solid foundation for precise feeding and future multi-robot collaboration.

Table 7.

Performance comparison between the enhanced and conventional DWA algorithms.

As summarized in Table 8, we compare the proposed method with representative baselines.

Table 8.

Literature-based comparison between the proposed method and representative local planners.

4. Conclusions

This study addresses the limited adaptability of the conventional DWA in horse barn feeding scenarios by proposing an enhanced DWA algorithm that relies solely on IMU-based pose sensing and incorporates an automatic drift correction mechanism. While retaining the original velocity sampling and evaluation framework, the enhanced algorithm feeds high-frequency yaw data from the IMU into a cascaded PID closed-loop controller, thereby achieving real-time coupling between the velocity commands issued by the planner and the pose regulation at the execution level.

Field experiments conducted across ten trials with identical start and goal positions demonstrated that the enhanced algorithm reduced the standard deviation of path deviation from 0.16 m to 0.144 m, representing a 10.46% improvement, and decreased the yaw angle standard deviation from 2.19° to 1.74°, corresponding to a 20.55% reduction in angular oscillation. These results confirm the robustness and high-precision capabilities of single-IMU closed-loop control in complex and dynamic environments.

The key innovation of this study lies in the integration of IMU data and PID control into the DWA path planning framework, establishing a closed-loop control system. By continuously acquiring the pose of the robot and applying real-time corrections, the proposed algorithm effectively addresses challenges such as attitude drift and wheel slip in dynamic environments. This enhancement enables robust and high-precision path tracking under complex conditions. The series of experiments confirmed the practical effectiveness of the algorithm, particularly in unstructured settings such as horse barns, where irregular terrain and dynamic obstacles are prevalent.

4.1. Limitations and Challenges

Despite the enhanced DWA algorithm achieving notable improvements in path planning accuracy and stability, certain limitations persist in specific scenarios. For example, under extreme terrain conditions—such as steep inclines or densely cluttered environments—the current automatic drift correction module may require additional tuning to maintain reliable performance.

Furthermore, although the IMU- and PID-based control system effectively compensates for pose deviations, a delay in attitude correction may still occur at higher speeds, which can impact real-time responsiveness and tracking precision. Extending the adaptability of the algorithm to broader agricultural contexts with more complex terrain and greater environmental variability remains an important direction for future research.

4.2. Future Work

Although the proposed method improves docking-level accuracy, residual drift may still occur under extreme low-friction conditions or at higher speeds, which can lead to small positioning offsets at feeding stations. In practice, this suggests using conservative speed limits near docking and motivates future multi-sensor fusion to further reduce residual errors. In future research, we aim to further optimize the enhanced DWA algorithm to better handle increasingly complex and dynamic environments. One promising direction is the integration of advanced sensor fusion techniques, combining LiDAR and IMU data to improve both the real-time responsiveness and precision of the planning process through more efficient data processing. To address the latency in pose correction, we also plan to incorporate more responsive attitude estimation algorithms, thereby reducing delay in PID control feedback. These improvements are expected to further enhance path tracking accuracy and overall system stability.

In addition, to enhance the generalizability and adaptability of the algorithm, future work will focus on developing its self-adaptive capabilities, particularly the dynamic adjustment of control parameters across varying scenarios, to ensure robust performance in diverse and changing environments. Integrating the enhanced local planner with global path planning frameworks will also be a key research direction, aiming to further improve the overall navigation performance of the robot in complex and unstructured settings.

Through these optimizations and enhancements, the proposed algorithm is expected to play a more significant role in a broader range of real-world applications, particularly in domains such as smart agriculture and intelligent livestock farming. These advancements will help accelerate the deployment of robotics in dynamic and complex environments.

Author Contributions

Resources, X.C.; Writing—original draft, H.Q., H.S., M.L. and W.Z.; Writing—review & editing, X.C., H.Q., P.Y., H.S., S.S., Y.P., X.Z., Z.Q., M.L. and W.Z.; Supervision, X.C., M.L. and W.Z.; Project administration, X.C., H.Q., M.L. and W.Z.; Funding acquisition, X.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Key R&D Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region: 2022B02027-1, 2023B02013-2.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because they were collected in privately operated equine feeding environments.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the anonymous reviewers and the editorial team for their valuable comments and constructive suggestions, which greatly improved the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Agelli, M.; Corona, N.; Maggio, F.; Moi, P.V. Unmanned Ground Vehicles for Continuous Crop Monitoring in Agriculture: Assessing the Readiness of Current ICT Technology. Machines 2024, 12, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etezadi, H.; Eshkabilov, S. A comprehensive overview of control algorithms, sensors, actuators, and communication tools of autonomous all-terrain vehicles in agriculture. Agriculture 2024, 14, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Elangovan, D.; Govindarajan, P.L.; ELnaggar, M.F.; Alrashed, M.M.; Kamel, S. A comprehensive review of path planning for agricultural ground robots. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Nguyen, B.K. Low-Cost Real-Time Localisation for Agricultural Robots in Unstructured Farm Environments. Machines 2024, 12, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, G.; Zheng, Q.; Bai, X.; Ding, Y.; Khan, A. Path planning for wheeled mobile robot in partially known uneven terrain. Sensors 2022, 22, 5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Review on Key Technologies for Autonomous Navigation in Field Agricultural Machinery. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zakaria, M.A.; Younas, M. Path Planning Trends for Autonomous Mobile Robot Navigation: A Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Qiu, Z.; Li, L.; Guo, K.; Li, D. Map Construction and Positioning Method for LiDAR SLAM-Based Navigation of an Agricultural Field Inspection Robot. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, N.; Suzuki, H.; Kitajima, T.; Kuwahara, A.; Yasuno, T. Path planning and traveling control for pesticide-spraying robot in greenhouse. J. Signal Process. 2017, 21, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contente, O.; Lau, N.; Morgado, F.; Morais, R. A path planning application for a mountain vineyard autonomous robot. In Proceedings of the Robot 2015: Second Iberian Robotics Conference: Advances in Robotics, Lisbon, Portugal, 19–21 November 2015; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 347–358. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Jin, L.; Wang, S. A path planning system for orchard mower based on improved A* algorithm. Agronomy 2024, 14, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.; Santos, F.; Mendes, J.; Costa, P.; Lima, J.; Reis, R.; Shinde, P. Path planning aware of robot’s center of mass for steep slope vineyards. Robotica 2020, 38, 684–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Huang, Q.; Cai, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Shi, L. HPS-RRT*: An Improved Path Planning Algorithm for a Nonholonomic Orchard Robot in Unstructured Environments. Agronomy 2025, 15, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Li, J.; Li, P. Improving path planning for mobile robots in complex orchard environments: The continuous bidirectional Quick-RRT* algorithm. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1337638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Wu, F.; Zou, X.; Li, J. Path planning for mobile robots in unstructured orchard environments: An improved kinematically constrained bi-directional RRT approach. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 215, 108453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, O. Real-Time Obstacle Avoidance for Manipulators and Mobile Robots. Int. J. Robot. Res. 1985, 5, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D.; Burgard, W.; Thrun, S. The Dynamic Window Approach to Collision Avoidance. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 1997, 4, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösmann, C.; Hoffmann, F.; Bertram, T. Kinodynamic Trajectory Optimization and Control for Car-Like Robots. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vilamoura-Algarve, Portugal, 7–12 October 2012; pp. 2148–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Wang, X.; Yu, S.; Wang, R.; Song, Z.; Yan, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, Z.; Yu, Z. Research on navigation path extraction and obstacle avoidance strategy for pusher robot in dairy farm. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harik, E.H.C.; Korsaeth, A. Combining hector slam and artificial potential field for autonomous navigation inside a greenhouse. Robotics 2018, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricioppo, P.; Mancini, M.; Capello, E. Learning-Based Artificial Potential Field Path Planning for Agricultural UGVs. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Agriculture and Forestry (MetroAgriFor), Padua, Italy, 29–31 October 2024; pp. 301–306. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Kang, Z.; Xie, H. Collision-free motion planning of a six-link manipulator used in a citrus picking robot. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wang, S.; Yi, Z.; Zhang, M.; Lv, X. Autonomous navigation system of greenhouse mobile robot based on 3D Lidar and 2D Lidar SLAM. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 815218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, W.; Yao, Q.; Nie, J.; Qi, X. Robot path planning navigation for dense planting red jujube orchards based on the joint improved A* and DWA algorithms under laser SLAM. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, T.; Rong, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Huo, Y.; et al. Path planning of greenhouse electric crawler tractor based on the improved A* and DWA algorithms. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytridis, C.; Bazinas, C.; Pachidis, T.; Chatzis, V.; Kaburlasos, V.G. Coordinated Navigation of Two Agricultural Robots in a Vineyard: A Simulation Study. Sensors 2022, 22, 9095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Ma, X.; Peng, T.; Wang, H. An improved timed elastic band (TEB) algorithm of autonomous ground vehicle (AGV) in complex environment. Sensors 2021, 21, 8312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Gu, Q.; Gu, H.; Xia, R.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Luo, K.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Y. Design of Chili Field Navigation System Based on Multi-Sensor and Optimized TEB Algorithm. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, M.; Li, G.; Ding, K. Obstacle avoidance path planning for apple picking robotic arm incorporating artificial potential field and A* algorithm. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 100070–100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Da, C. Global and local path planning of robots combining ACO and dynamic window algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Huang, S.; Li, M. An Improved Global and Local Fusion Path-Planning Algorithm for Mobile Robots. Sensors 2024, 24, 7950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour Arab, D.; Spisser, M.; Essert, C. Complete coverage path planning for wheeled agricultural robots. J. Field Robot. 2023, 40, 1460–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teji, M.D.; Zou, T.; Zeleke, D.S. A survey of off-road mobile robots: Slippage estimation, robot control, and sensing technology. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2023, 109, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Gao, Q.; Bai, Z.; Zhang, L.; Ye, Y. LiDAR-based negative obstacle detection for unmanned ground vehicles in orchards. Sensors 2024, 24, 7929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhu, D.; Zhao, W.; Wang, F.; Liu, Y. A local path planning algorithm for robots based on improved DWA. Electronics 2024, 13, 2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åström, K.J.; Hägglund, T. PID Controllers: Theory, Design, and Tuning, 2nd ed.; Instrument Society of America: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).