Abstract

In low-resource speech recognition, the performance of the Whisper model is often limited by the size of the available training data. To address this challenge, this paper proposes a training optimization method for the Whisper model that integrates Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) with the Optuna hyperparameter optimization framework. This combined approach enables efficient fine-tuning and enhances model performance. A dual-metric early stopping strategy, based on validation loss and relative word error rate improvement, is introduced to ensure robust convergence during training. Experimental data were collected from three low-resource languages in Xinjiang, China: Uyghur, Kazakh, and Kyrgyz. Compared to baseline LoRA fine-tuning, the proposed optimization method reduces WER by 20.98%, 6.46%, and 8.72%, respectively, across the three languages. The dual-metric early stopping strategy effectively shortens optimization time while preventing overfitting. Overall, these results demonstrate that the proposed method significantly reduces both WER and computational costs, making it highly effective for low-resource speech recognition tasks.

1. Introduction

Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) technology [1,2,3] serves as one of the cornerstone technologies in human–computer interaction, with extensive applications in smart home systems, healthcare, mobile devices, and automotive technologies. In recent years, companies such as iFlytek, Baidu, Microsoft, and OpenAI have introduced a variety of speech recognition products. These innovations have not only broadened the scope of speech technology applications but have also advanced the field through continuous algorithmic optimization and performance improvement.

However, the development of speech recognition technology remains considerably imbalanced. Most ASR models are tailored for high-resource languages such as English and Chinese, which typically possess large annotated datasets containing hundreds of thousands of samples. These abundant resources have driven rapid advancements in both research and practical applications of speech recognition [4,5,6]. In contrast, low-resource languages, such as the Turkic languages spoken in China’s Xinjiang region (Uyghur, Kazakh, and Kyrgyz) [7], continue to encounter significant challenges due to the scarcity of labeled data and their complex linguistic features, particularly their agglutinative morphology.

Currently, speech recognition systems mainly adopt two paradigms: traditional hybrid architectures and end-to-end architectures. In hybrid architectures, researchers have replaced conventional deep neural network (DNN) [8] with more advanced neural models, such as recurrent neural network (RNN) [9] and convolutional neural network (CNN) [10], achieving localized improvements within the traditional framework. In contrast, end-to-end architectures [11] integrate multiple components, such as acoustic models, pronunciation dictionaries, and language models, into a unified network that enables joint training. This design allows direct mapping from input audio sequences to corresponding label sequences, thereby simplifying the overall training process. Although these approaches have demonstrated outstanding performance in high-resource languages, they typically require large amounts of annotated data. Under low-resource conditions, however, the scarcity of labeled data severely degrades system performance and may even cause recognition failure.

To address this limitation, researchers in the field of speech recognition are exploring new approaches. In recent years, the rising popularity of large language models [12,13], such as BERT [14] and ChatGPT-4 [15], has also created new development opportunities for speech recognition. In particular, large-scale multilingual and multi-task speech models have gradually emerged as a promising solution for low-resource speech recognition [16]. Among these models, OpenAI’s Whisper [17] can recognize and transcribe approximately 100 languages, providing a powerful tool for low-resource scenarios. However, because its primary training dataset predominantly consists of high-resource languages such as English, Whisper often performs poorly on low-resource languages. Consequently, optimizing and fine-tuning the Whisper model for low-resource environments has become essential to enhancing its recognition performance.

In the fine-tuning Whisper models, researchers often employ parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods [18,19]. These approaches enhance model performance by updating only a subset of parameters or critical modules, thereby avoiding the computational overhead associated with full parameter updates. Among them, LoRA [20,21,22] has become a widely adopted technique. LoRA achieves substantial reductions in trainable parameters and computational cost by freezing pre-trained model weights and injecting trainable low-rank matrices into specific layers, such as self-attention modules. Its effectiveness in speech recognition has been well demonstrated. For example, Sicard et al. [23] fine-tuned Whisper to reduce word error rates on Swiss German dialects; Liu et al. [24] proposed a sparse-shared LoRA method for efficient fine-tuning, enabling rapid adaptation to children’s ASR tasks; Polat et al. [25] achieved a 52.38% reduction in word error rate on Turkish by applying LoRA to Whisper. While these studies provide valuable theoretical and practical insights, most rely on manual experience to set hyperparameters, such as the rank of the low-rank matrices and learning rate, leaving the impact of hyperparameter tuning on Whisper performance underexplored.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a tuning method that combines LoRA with the Optuna [26,27,28] hyperparameter optimization framework. The method investigates the synergistic effects of LoRA fine-tuning and hyperparameter optimization in improving Whisper model performance under low-resource conditions. In addition, a dual-metric early stopping mechanism [29] is incorporated to enhance the robustness of the training process. This study focuses on three Turkic languages spoken in Xinjiang, China, with the goal of validating the effectiveness of the LoRA-Optuna framework for low-resource Whisper fine-tuning and to provide a reproducible technical approach for speech recognition in minority languages.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

- By integrating LoRA with the Optuna hyperparameter optimization framework, this study enables efficient fine-tuning of the Whisper model for low-resource languages and systematically analyzes the impact of five hyperparameters on Whisper’s performance.

- The introduction of a dual-metric early stopping strategy effectively prevents overfitting while reducing hyperparameter search time.

- Experiments on three low-resource Turkic languages in Xinjiang, China, demonstrate the robustness and general applicability of the proposed method across diverse low-resource language settings.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a detailed description of the Whisper model used in this study, the LoRA fine-tuning strategy, and the Optuna hyperparameter optimization framework. Section 3 presents the datasets and evaluation metrics employed. Section 4 details the experimental design, results analysis, and hyperparameter sensitivity studies for the three low-resource languages. Section 5 discusses the study’s limitations, computational costs, and reproducibility considerations, and provides an outlook for future research directions.

2. Methods

2.1. Whisper Model

The Whisper model, developed by OpenAI, supports multiple tasks, including automatic speech recognition, speech translation, and language identification. Trained on 680,000 h of multilingual audio data, it demonstrates remarkable cross-language generalization capabilities. As illustrated in Figure 1, its architecture is based on a Transformer [30] encoder-decoder framework that maps input audio spectral features to text sequences. During audio processing, all inputs are resampled to 16 kHz before being fed into the feature extractor, ensuring consistency with the model’s pre-training configuration. Whisper employs a built-in feature extractor to normalize raw waveforms to a uniform length: audio clips shorter than 30 s are zero-padded at the end (representing silence), while clips longer than 30 s are truncated to 30 s.

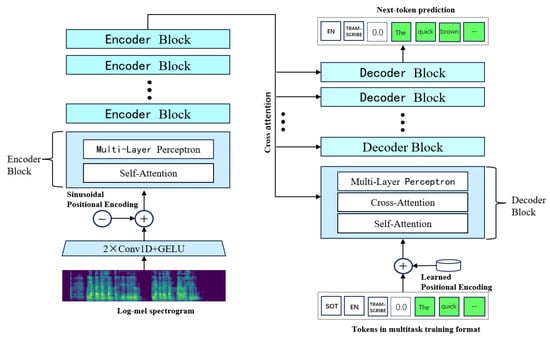

Figure 1.

Whisper model architecture diagram.

Subsequently, the feature extractor applies pre-emphasis and performs framing and windowing on the audio, then computes the complex spectrum using the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT). The power spectrum is calculated, the frequency axis is mapped to the Mel scale, and the logarithm of the power spectrum is taken to generate the log-Mel spectrogram. This spectrogram is further processed through a 2 × 1D convolutional layer with GELU (Gaussian Error Linear Unit) activation. Positional encoding is then applied to the convolutional output to encode temporal positions, enabling the model to capture sequential information within the audio. The resulting sequence is subsequently fed into the encoder.

During the encoding phase, the Mel-spectrogram is used as input and encoded to produce a sequence of encoder hidden states, extracting key features of the input speech. In the decoding phase, an autoregressive model predicts a sequence of text tokens. The process begins with a sequence containing only a “start” token (Whisper uses SOT as the start token), predicting one token at a time. It first predicts the most likely word, then generates the next word based on previous predictions, continuing until the entire speech sequence is transcribed.

2.2. Low-Rank Adaptation

Currently, existing fine-tuning methods are primarily categorized into two types: full-parameter fine-tuning and parameter-efficient fine-tuning [18]. However, with the rise of large-scale models, parameter-efficient fine-tuning has gained increasing popularity. Mainstream parameter-efficient fine-tuning techniques include the adapter method, soft prompting, low-rank adaptation, and bias fine-tuning. This paper adopts the low-rank adaptation method to perform parameter-efficient fine-tuning on the Whisper model, aiming to enhance its performance on speech recognition tasks in the target language.

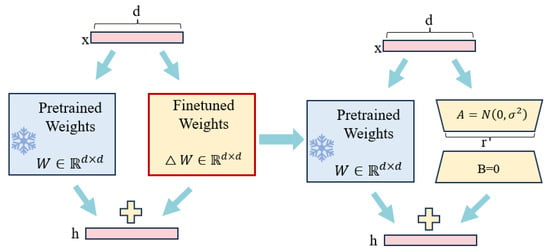

The core idea of LoRA involves adding two low-rank matrices to the original parameter matrix of a pre-trained model to learn features for new tasks. During training, only the parameters of these two low-rank matrices are updated, while the original weight matrix remains unchanged. This enables the model to acquire knowledge for new tasks while preserving the generalization capabilities of the pre-trained model. The structural diagram of LoRA is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

LoRA architecture diagram.

Assuming the original weight matrix of the pre-trained large model is , which remains frozen throughout the fine-tuning process, the parameter update is performed by introducing a low-rank matrix, as shown in Equations (1) and (2):

Here, and , with the matrix rank . By controlling the rank r, the number of trainable parameters can be reduced from to 2rd, thereby improving training efficiency.

For the two low-rank matrices, a differentiated initialization is used: the elements of matrix A are initialized from a Gaussian distribution , while all elements of matrix B are initialized to 0. This initialization ensures that , thereby maintaining consistency between the initial state of the model and the original pre-trained model.

Given an input , the output after passing through LoRA is given in Equation (3):

During training, LoRA updates only the matrices A and B. The final weights W are computed as shown in Equation (4):

Here, is the proportionality factor used to balance the contributions of new and existing knowledge to the target task in the experiments.

The LoRA fine-tuning method is applied to the Whisper model. This approach effectively captures task-specific features by training only a small number of low-rank matrix parameters while keeping the original pre-trained model parameters frozen, thereby improving the model’s performance on the target task. Table 1 compares LoRA fine-tuning with full-parameter fine-tuning methods.

Table 1.

Comparison of LoRA and Full Parameter Fine-Tuning.

LoRA fine-tuning has been validated on models like RoBERTa, DeBERTa, and GPT-2/3. By training only a small subset of parameters, it achieves results comparable to, or even better than, full-scale fine-tuning, without introducing additional inference latency [20]. This significantly reduces resource consumption during the fine-tuning process. As a result, the model can quickly adapt to new tasks even in resource-constrained environments, making it particularly well-suited for low-resource language scenarios.

2.3. Optuna Hyperparameter Optimization Method

Although LoRA can enhance training efficiency while maintaining model performance, its effectiveness largely depends on the proper configuration of certain hyperparameters during fine-tuning. Biderman et al. [31] noted that LoRA’s performance can be suboptimal when common low-rank settings are used throughout the tuning process. Additionally, LoRA is highly sensitive to hyperparameters, including learning rate, target module selection, and scaling factor. Properly configuring these parameters is essential for achieving performance close to full fine-tuning. Research has shown that a well-chosen scaling factor can significantly influence model performance [32]. However, hyperparameters that are empirically determined may not consistently apply across different tasks or model scales. As a result, hyperparameter optimization techniques are critical for identifying the optimal combinations during LoRA fine-tuning. Traditional hyperparameter search methods, such as grid search and random search, are often inefficient in high-dimensional spaces, making effective optimization challenging, especially with limited computational resources.

To address the issues mentioned above, this paper employs the Optuna hyperparameter optimization framework to optimize relevant hyperparameters. Optuna is a flexible and efficient automated hyperparameter optimization tool that supports various sampling strategies, such as the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE), to efficiently search for optimal hyperparameter combinations.The core idea of the TPE algorithm is to dynamically divide historical observations into high-performing and low-performing sample sets based on a predefined quantile . Each group is then modeled separately using Parzen windows (kernel density estimation), producing two probability density functions: for high-performing samples and for low-performing samples. During optimization, the algorithm selects hyperparameter values that maximize the ratio as the next candidates, prioritizing exploration in regions with higher likelihood of yielding high-quality solutions. As the number of trials increases, TPE automatically concentrates sampling in high-performance regions, allowing efficient convergence toward the global optimum with fewer trials.

During hyperparameter optimization, some trials may exhibit poor performance in the early stages of training, and continuing them would waste substantial computational resources. To address this, this study employs Optuna’s built-in Median Pruner strategy: after a trial reaches a specified warm-up intermediate step, its intermediate evaluation metric is compared with the median value of previously completed trials at the same step. If the current metric lags behind the median according to the optimization direction, the trial is pruned immediately. This mechanism effectively conserves computational resources and accelerates the hyperparameter search process.

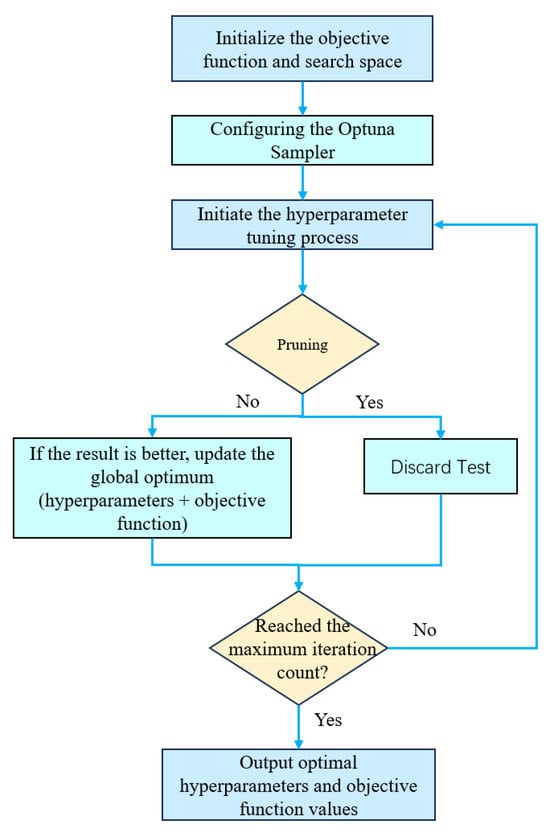

The specific Optuna optimization process is shown in Figure 3. When performing optimization with Optuna, both the objective function and the search space need to be initialized. The sampling strategy is set to TPE to sample the search space, exploring how different hyperparameter configurations influence model performance. Each set of hyperparameters is evaluated, and an objective function value is returned as feedback for the optimization process.

Figure 3.

Optuna flowchart diagram.

During hyperparameter tuning, a pruning strategy is used to determine whether a current trial meets the pruning criteria. If the criteria are met, the trial is skipped. If pruning conditions are not triggered, the trial results are compared with the historical best. If the current result is better, the optimal parameter configuration is updated. The optimization process continues until the preset maximum number of trials is reached, ultimately outputting the optimal hyperparameter configuration and its corresponding objective function value.

3. Experimental Datasets and Performance Evaluation Methods

3.1. Dataset

This paper uses publicly available speech data from three minority languages in China’s Xinjiang region as experimental datasets. These include the Uyghur (Ug) dataset THUYG-20 [33], the Kyrgyz (Ky) dataset from Mozilla Foundation’s Common_Voice_15 platform [34], and the Kazakh (Kk) dataset from Google’s FLEURS [35].

Table 2 presents the speech datasets used in this paper along with their relevant details. Low-resource speech datasets of varying lengths were selected to systematically analyze the applicability of the Optuna optimization algorithm combined with the LoRA fine-tuning method across different datasets. Experiments were conducted using the PyTorch 2.0.1 deep learning framework and the Visual Studio Code 2023 development environment. Model training was performed on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4070 Ti GPU with 16 GB of VRAM.

Table 2.

Three language datasets from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China. The numbers in parentheses “()” represent the dataset split ratio (train: validation: test).

3.2. Performance Evaluation Metrics

In the field of speech recognition, the Word Error Rate (WER) is a key metric for evaluating model performance. WER is calculated by comparing the model’s predicted text with the target text word by word and counting the errors in the prediction. These errors are categorized into three types: Substitution (S), where an incorrect word is transcribed; Insertion (I), where an extra word is added; and Deletion (D), where a word is omitted. The formula for calculating the WER is shown in Equation (5):

Here, S, I, and D denote the number of substitution, insertion, and deletion errors, respectively, while N represents the total number of words in the target text. A lower WER value indicates better model recognition performance.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Whisper Low-Resource Speech Recognition Based on LoRA

4.1.1. Baseline Model Selection

The Whisper model is available in five versions: Tiny, Small, Base, Medium, and Large, with differences in the number of layers, the dimensionality of feature representations, and the number of attention heads. To more effectively compare the performance of these models across different languages, this study uses the Direct Inference (DI) method. In this approach, the pre-trained Whisper model is evaluated on the test set without any additional fine-tuning or optimization. This method directly assesses the performance of each model version across languages, providing valuable insights for selecting the most appropriate model for future experiments. Table 3 summarizes the WER for Whisper models of varying sizes during DI across the three languages.

Table 3.

WER for DI on Whisper models of varying sizes. WER values exceeding 100% still indicate the correct language.

As shown in Table 3, WER decreases across the three low-resource languages as the Whisper model size increases. However, both Ug and Ky exhibit WER values exceeding 100% across all five Whisper versions, indicating that the model lacks recognition capability for these languages. Kk performs best with the Large version, but its WER remains as high as 52.13%, which fails to meet practical application requirements and necessitates further fine-tuning.

Therefore, this paper uses LoRA to fine-tune the Whisper model, allowing it to quickly adapt to new target tasks in low-resource environments. Due to limited GPU memory, the Whisper-Medium version is chosen as the baseline model for the following experiments.

4.1.2. LoRA Fine-Tuning

The Whisper model demonstrates suboptimal recognition performance across three low-resource languages and incurs substantial costs when fully fine-tuned. To address this, this paper adopts the LoRA fine-tuning approach to investigate the trade-off between model performance and computational efficiency. Experiments were conducted over 4000 training steps, with checkpoints saved every 500 steps. The learning rate is set to 0.00001, employing the constant_with_warmup schedule, as shown in Equation (6):

Here, t denotes the current training step, represents the warm-up step, and corresponds to the initial learning rate. This strategy gradually increases the learning rate linearly during the early training phase, then keeps it constant to ensure stable training. The checkpoint achieving the lowest WER is ultimately selected as the fine-tuned model. Detailed parameter settings are presented in Table 4:

Table 4.

Parameter Settings for LoRA Fine-Tuning.

Before fine-tuning, text input requires processing. The Whisper tokenizer has been trained on pre-trained transcription data across multiple languages, featuring extensive byte pairs suitable for multilingual ASR tasks. In this paper, for three low-resource languages, we directly fine-tune using Whisper’s built-in tokenizer. By setting language = ‘zh’ and task = ‘transcribe’ in the tokenizer configuration, we leverage the pre-trained tokenizer’s multilingual knowledge transfer capabilities. This eliminates the need for training new tokenizers, enabling the model to efficiently adapt to specific tasks on low-resource languages.

Following the approach in PEFT [36], LoRA fine-tuning is applied to the query and value positions within the attention modules of each layer in the Whisper model’s encoder and decoder. The parameters are set as follows: rank = 32, alpha = 64, dropout rate = 0.05, and batch size = 4. With this configuration, only the parameters of the LoRA low-rank matrices are updated, accounting for approximately 1.2204% of the total parameters. The peak memory usage is 8.5 GB, significantly reducing computational and memory overhead during fine-tuning compared to full-parameter fine-tuning (peak memory: 15.6 GB). This allows the Whisper model to adapt to specific tasks without requiring substantial computational resources. Therefore, fine-tuning the Whisper model with LoRA significantly improves training efficiency for target tasks.

Table 5 presents the performance comparison of the Whisper-Medium model across three low-resource languages, including the WER for direct inference (DI) before LoRA fine-tuning and the WER after LoRA fine-tuning. It also shows the memory consumption after LoRA fine-tuning and the average experimental runtime per trial. To evaluate the robustness of the results, each experiment was conducted using three different random seeds (42, 2025, 12) [37], and the average WER, standard deviation (SD), and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated.

Table 5.

WER (mean ± SD) and 95% CI for Whisper model DI and LoRA fine-tuning on three low-resource languages. Times in parentheses (e.g., Ug (3.4 h)) denote the average training duration across three independent runs with different random seeds for each language.

LoRA fine-tuning substantially improves recognition performance across all three low-resource languages, while the SD and 95% CI remain consistently low, indicating strong stability. For Ug, the WER decreases from 110.19% to 55.58%; for Kk, it drops from 48.92% to 30.81%; and for Ky, it falls from 102.23% to 49.84%. These results demonstrate that LoRA fine-tuning not only greatly reduces the computational cost under low-resource conditions but also significantly enhances recognition accuracy, yielding stable and reproducible performance across experiments.

4.2. Cooperative Optimization of LoRA Hyperparameters Based on Optuna

4.2.1. Construction of Hyperparameter Search Space

To achieve effective hyperparameter optimization, this paper defines the hyperparameter search space within the Optuna framework, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Definition of Hyperparameter Search Space.

During the optimization process, this paper uses the model’s WER on the validation set as the optimization objective. The Optuna optimization framework automates the hyperparameter search for the Whisper model. In each trial, the TPE sampler generates a set of hyperparameters from the search space shown in Table 6 and then executes the full LoRA fine-tuning process using that configuration. After each trial, GPU memory is immediately released, and the pre-trained model is reloaded to prevent memory overflow. To balance computational cost and optimization quality, the maximum number of trials is set to 50, with each trial executed under identical hardware and parameter configurations. The hyperparameter combination yielding the lowest validation set WER is selected as the optimal result.

4.2.2. Dual-Criteria Early-Stopping Strategy

To further enhance optimization efficiency, this study simultaneously applies early stopping strategy and Optuna’s median pruning strategy. At the experimental level, median pruning removes inefficient parameter configurations through intermediate evaluations. At the training level, early stopping strategy stops the training process early based on validation metrics. The synergistic combination of these two strategies enhances overall search efficiency and resource utilization.

During the training of speech recognition models, traditional early stopping strategy typically relies on validation loss as the stopping criterion. However, observations from practical training processes show that validation loss does not always strongly correlate with recognition performance. At certain stages, the model’s validation loss may continue to decrease while the WER stabilizes or even increases. In such cases, continuing training solely based on a decreasing validation loss can lead to wasted computational resources without improving recognition accuracy.

Therefore, this paper proposes a dual-criterion early stopping strategy, which enables more rational control over early stopping decisions. Specifically, this strategy monitors two key metrics: validation loss and the relative improvement rate of WER. During each evaluation round, if the difference between the current validation loss and the historical minimum falls below a predefined threshold, it is considered a “non-significant decline.” At the same time, the relative improvement rate of the word error rate is computed. If the relative improvement rate between the current and the historical best WER falls below the threshold, it is regarded as “no improvement.” The formula for calculating the relative improvement rate of WER is shown in Equation (7).

During training, the number of consecutive rounds without improvement is monitored for both metrics. If either the validation loss or the relative improvement rate of WER falls below the set tolerance threshold, the model is considered to have converged, triggering early stopping.

To validate the effectiveness of this strategy, this paper employs Optuna for the co-optimization of LoRA hyperparameters using the Whisper-base model and the FLEURS Kk dataset from Section 3.1 as the experimental foundation. The training step count is set to 3000, with validation performed every 500 steps. Other hyperparameter settings are provided in Table 4. Specifically, the early stopping strategy combines two metrics: validation loss and relative WER improvement rate. The validation loss threshold is set to 0.001, and the relative WER improvement threshold is set to 1%. The early stopping strategy is triggered if either metric fails to meet the improvement criteria in two consecutive evaluations. Median pruning involves comparing the current trial’s validation WER against the median WER from the same period in historical data at each intermediate evaluation point. If the current WER is higher than the median, the trial is immediately discarded to prevent subsequent ineffective training. Pruning only takes effect after the completion of the two intermediate steps preceding each trial.

The experimental design included two sets of control experiments, evaluating median pruning combined with the baseline early stopping and median pruning combined with the dual-criterion early stopping strategy, respectively. To reduce the impact of random factors, each experiment was repeated three times, with results averaged. Key metrics included WER and training duration. Specific results are shown in Table 7:

Table 7.

Performance Comparison of Whisper-based Models Using Dual-Indicator Joint Early-Stopping Strategy.

As shown in Table 7, the WER under the baseline early stopping strategy was 34.88%, while adopting the dual-metric early stopping strategy reduced it to 34.47%, representing a relative improvement of 1.2%. In terms of training time, the dual-metric early stopping approach saved approximately 2.56 h compared with the baseline method. These results indicate that the dual-metric joint early stopping strategy can shorten the optimization cycle and improve resource utilization without compromising accuracy.

4.2.3. Optuna Hyperparameter Optimization Based on Dual-Indicator Early Stopping Strategy

The validation results of the dual-metric early stopping strategy on the Whisper-base model demonstrate that this approach effectively enhances model performance while reducing training time. Building on this foundation, this paper further extends the experiments to the larger-parameter Whisper-medium model. By integrating the LoRA fine-tuning method, an Optuna-based automated hyperparameter optimization framework incorporating the improved strategy was constructed. Training was conducted for 3000 steps with validation every 500 steps, and other experimental settings are detailed in Table 4. After 50 rounds of hyperparameter searches across three language tasks, the optimal hyperparameter configurations were obtained for the following three low-resource language datasets ( and represent scientific notation with minor variations in optimization parameters).

Table 8 presents the optimal parameter combinations and optimization times across three low-resource language datasets. The average optimization time was approximately 109 h, reflecting the substantial computational cost and duration required for multi-round optimization of large models. Despite this time investment, the optimized hyperparameter configurations can be directly reused in subsequent experiments or deployment phases, achieving an effective balance between training cost and model performance. Among the optimal hyperparameter combinations for the three low-resource languages, the r value consistently remains at 32, while other hyperparameters vary. This suggests differing parameter sensitivities across languages, necessitating tailored configurations to accommodate the unique characteristics of each language dataset.

Table 8.

Optimal hyperparameter combinations and WER for three datasets after 50 rounds of optimization.

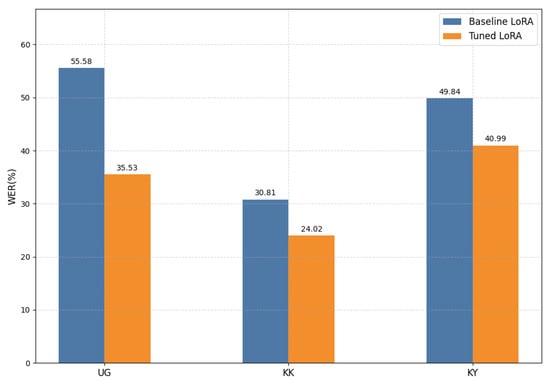

Figure 4 presents the WER comparison between baseline LoRA fine-tuning and the optimized LoRA fine-tuning across three low-resource languages. On the Ug dataset, the WER decreases from 55.58% to 35.53%; on the Kk dataset, it drops from 30.81% to 24.02%; and on the Ky dataset, it declines from 49.84% to 40.99%. These results indicate that the proposed Optuna+LoRA optimization framework, combined with the improved search strategy, significantly enhances model performance on low-resource languages. Furthermore, the approach achieves substantial performance gains while fine-tuning only a small subset of parameters, underscoring the effectiveness and practicality of integrating LoRA with Optuna for model adaptation in low-resource scenarios.

Figure 4.

Comparison of WER between baseline LoRA fine-tuning and optimized LoRA fine-tuning across three low-resource languages.

4.3. Experimental Verification and Analysis

4.3.1. Verification of Optimized Parameters

The hyperparameter configurations obtained through Optuna optimization must be validated on an independent dataset to ensure the reliability and stability of the optimized results. The model is retrained and evaluated using the dataset described in Section 3.1, with the pre-trained model reinitialized to verify the effectiveness of the optimized hyperparameters. The experimental setup follows the configuration outlined in Section 4.1.2. After replacing the empirical hyperparameters with those identified by Optuna (Table 8), the model is trained for 4000 steps, with checkpoints saved every 200 steps.

In low-resource settings, models are highly susceptible to overfitting due to the limited amount of training data. To mitigate this issue, this paper introduces a dual-metric early stopping strategy to improve training stability and prevent performance degradation.

To robustly evaluate the effectiveness of LoRA fine-tuning strategies and hyperparameter optimization, randomized seed-repeat experiments were conducted on three low-resource languages (Ug, Kk, and Ky). Specifically, each experiment was independently trained using three distinct random seeds (42, 2025, and 12). The final WER was recorded for each run, and the mean, standard deviation (SD), and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated to ensure robust and reproducible results. The performance metrics reported represent the average across the three seed experiments. The results are summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

Comparison of WER (mean ± standard deviation) between baseline LoRA fine-tuning and optimized LoRA fine-tuning for speech recognition tasks on three low-resource languages.

Experimental results show that after LoRA fine-tuning with parameters optimized via Optuna, the WER for all three languages was significantly lower than that of the baseline LoRA fine-tuning. Specifically, for Ug, the WER decreased from 55.58% to 34.60%, a reduction of 20.98%; for Kk, it dropped from 30.81% to 24.35%, a reduction of 6.46%; and for Ky, it declined from 49.84% to 41.12%, a reduction of 8.72%. In addition, the small standard deviations and 95% confidence intervals indicate that the results are stable and reproducible across repeated experiments.

After completing the overall performance evaluation using multiple random seeds, this paper further analyzed the statistical significance of the optimal parameter configuration by performing more detailed statistical tests and examining the training process under a fixed random seed (seed = 42). Subsequently, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test [38] was conducted on the paired WER values between the baseline LoRA model and the parameter configuration obtained through Optuna + LoRA optimization on the test set. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test is a nonparametric paired test suitable for situations where the observed differences do not follow a normal distribution. The procedure involves calculating the differences between each pair of observations, as shown in Equation (8):

Following the exclusion of samples with zero differences, the absolute values of the remaining differences were sorted in ascending order and assigned corresponding ranks. The original signs of the differences were then restored to determine positive and negative directions, yielding the positive rank sum and negative rank sum, respectively. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test uses the smaller of these two rank sums as the test statistic. Based on this statistic, the p-value is calculated to assess whether the difference between the two groups is statistically significant (p-value < 0.05).

As shown in Table 10, experimental results on the test set indicate that LoRA fine-tuning under the optimal parameter configuration significantly outperforms baseline LoRA fine-tuning across all three low-resource languages (Ky, Ug, Kk) (p-value < 0.05). Sentence-level comparisons show that recognition accuracy improves for most sentences under the optimal parameter configuration, fully demonstrating the effectiveness and stability of the hyperparameter optimization. Furthermore, this paper examines the evolution of training-stage loss and WER to evaluate the model’s training process and convergence under the optimized parameters.

Table 10.

Sentence-level performance comparison on the test set between baseline LoRA fine-tuning and optimized LoRA fine-tuning across three low-resource languages.

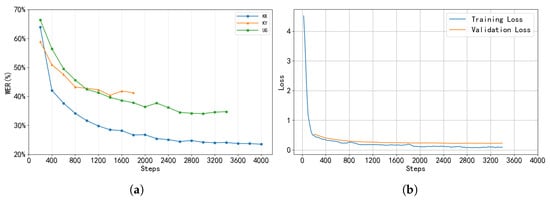

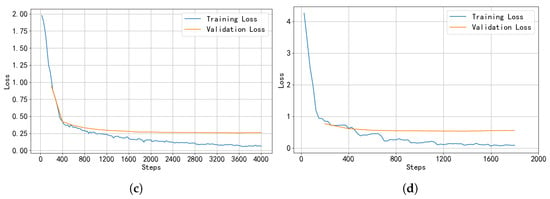

Figure 5 illustrates the training performance of three low-resource languages under optimized parameter settings. Figure 5a shows the WER evolution for the three languages during training. The WER for all three languages demonstrates a clear downward trend, indicating that the model’s recognition capability for Turkic languages improves progressively. Specifically, Ug converged at 3000 steps with a WER of 34.04%; Ky converged at 1400 steps with a WER of 40.35%; and Kk converged at 3600 steps with a WER of 24.09%. These results demonstrate that the parameter combinations obtained via Optuna optimization effectively enhance the model’s recognition performance on these low-resource languages.

Figure 5.

(a) Comparison of WER across three low-resource languages under optimal hyperparameter configurations. (b) Ug training and validation loss curves over training steps. (c) Kk training and validation loss curves over training steps. (d) Ky training and validation loss curves over training steps.

Figure 5b–d show the training and validation loss curves for Ug, Kk, and Ky, respectively. For Ug and Kk, the training and validation loss curves follow similar trends, showing no obvious signs of overfitting. In the case of Ky, the training and validation losses differ by approximately 0.5 but both converge to stable values, indicating that the model achieves good fit on both the training and validation sets. These results suggest that the dual-metric early stopping strategy adopted in this study helps the model converge stably.

4.3.2. Parameter Impact Analysis

In resource-constrained speech recognition tasks, model performance is particularly sensitive to hyperparameters. For each of the three languages, this study conducted 50 rounds of hyperparameter tuning experiments, with some trials prematurely terminated due to median pruning and thus excluded from subsequent parameter analysis. Upon aggregating the optimization results, certain trials exhibited abnormally high WER values, which could potentially skew assessments of the true contributions of individual hyperparameters. To achieve a robust sensitivity analysis, two metrics were introduced: Median WER and Median Absolute Deviation (MAD). Median WER serves as a measure of central tendency, is insensitive to extreme WER values, and accurately reflects model performance across the majority of samples. MAD functions as a robust measure of dispersion, quantifying the deviation of WER from the median. Compared with standard deviation, MAD demonstrates stronger resilience to outliers.

Table 11 presents the mean WER, median WER, and MAD across all experimental results for the three low-resource languages, reflecting the overall performance distribution and variability of the model under different hyperparameter combinations. Median WER and MAD provide more robust measures of central tendency and dispersion, effectively mitigating the influence of extreme WER values. Based on these metrics, outlier experiments were identified and removed using the criterion Median . After this cleaning process, 32, 37, and 34 complete experiments remained for Ug, Kk, and Ky, respectively, for subsequent analysis. The removal rate did not exceed 14%, ensuring that the overall trends were not affected. Using the outlier-cleaned data, further analyses were conducted, including Optuna hyperparameter sensitivity analysis, parameter correlation analysis, and significance testing based on p-values. This approach ensures that the final analysis is robust and reliable, free from the influence of extreme outlier experiments.

Table 11.

Statistical distribution of WER across experimental results for three low-resource languages.

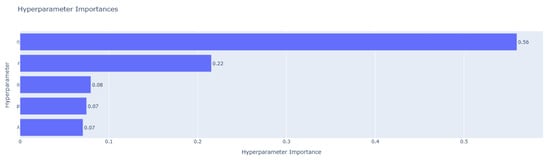

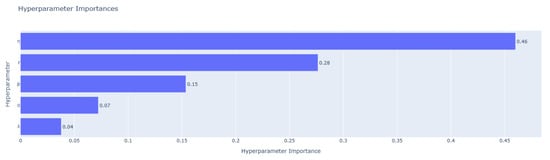

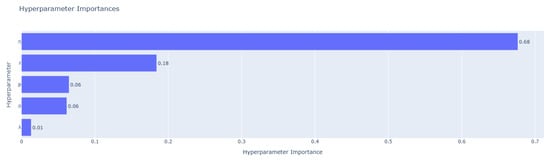

After removing outliers, this paper further utilizes Optuna’s built-in fANOVA method to evaluate hyperparameter importance. This approach constructs a random forest model to estimate each hyperparameter’s contribution to performance variance, thereby quantifying its true impact during optimization. Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the hyperparameter sensitivity for Ug, Kk, and Ky, respectively.

Figure 6.

Hyperparameter sensitivity analysis for Ug.

Figure 7.

Hyperparameter sensitivity analysis for Kk.

Figure 8.

Hyperparameter sensitivity analysis for Ky.

For Ug and Ky, the hyperparameter has the greatest impact, followed by r, while the remaining parameters exert relatively minor effects. In contrast, Kk displays a more balanced sensitivity pattern. Although remains the primary contributor, the influence of r and p is noticeably higher, suggesting that performance in Kk depends more on the coordinated tuning of multiple hyperparameters. Overall, across all three low-resource languages, consistently has the most significant effect on model performance, followed by r. Sensitivity to p varies among languages, whereas the effects of and are comparatively weaker.

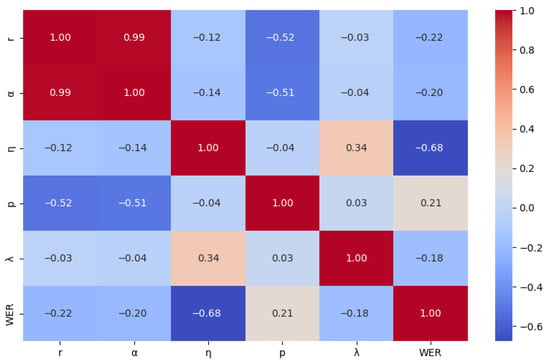

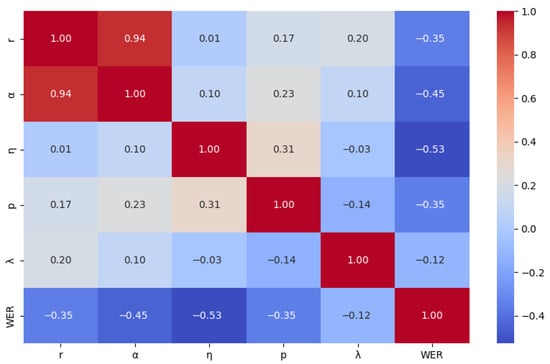

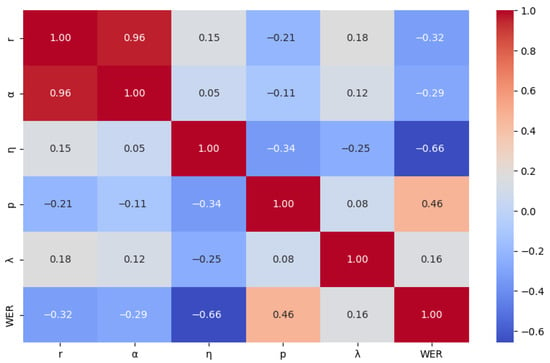

After completing the hyperparameter sensitivity analysis using fANOVA, this paper further validated the relationship between hyperparameters and model performance through statistical correlation and significance testing to ensure the robustness of the findings. Using the processed optimization data, a Pearson correlation coefficient matrix was constructed between hyperparameters and WER and visualized as a heatmap. The heatmap intuitively depicts the relationships through color intensity and numerical values: red indicates positive correlations in the range [0, 1], while blue indicates negative correlations in the range [−1, 0]. Darker colors represent stronger correlations.

Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 respectively show the correlation between hyperparameters and WER for Ug, Kk, and Ky. Across the three low-resource language datasets, r, , and exhibit negative correlations with WER, indicating that appropriately increasing these hyperparameters within their valid ranges can help reduce WER. In contrast, the effects of p and vary by language: p is positively correlated with WER in Ug and Ky but negatively correlated in Kk; shows a positive correlation in Ky but negative correlations in Ug and Kk. These results indicate that the model’s sensitivity to hyperparameters differs across languages.

Figure 9.

Correlation heatmap between hyperparameters and WER for Ug.

Figure 10.

Correlation heatmap between hyperparameters and WER for Kk.

Figure 11.

Correlation heatmap between hyperparameters and WER for Ky.

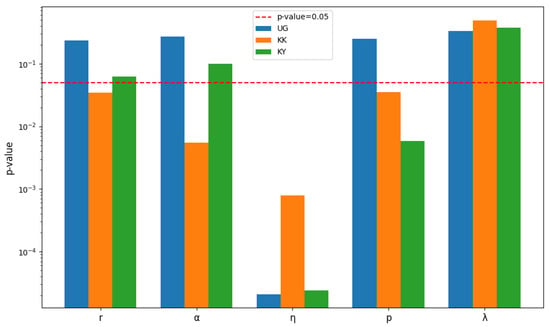

To further validate the statistical significance of these trends, Pearson correlation significance tests were conducted for the three languages (significance level = 0.05). Figure 12 shows the p-value analysis of hyperparameters versus WER for each language. The results indicate that significantly affects WER across all three languages (p-value ). r and show significant correlations in Kk (p-value ) but not in Ug or Ky (p-value ). p is significantly correlated in Kk and Ky (p-value ) but not in Ug, while is insignificant for all three languages (p-value ), further confirming its unstable influence. Overall, this test provides statistical evidence for the linear impact of each hyperparameter on WER across languages, supporting the robustness of our conclusions. Notably, although Pearson primarily measures linear relationships, combining it with fANOVA’s nonlinear sensitivity analysis allows for a more comprehensive assessment of hyperparameter effects.

Figure 12.

p-value analysis of hyperparameters and WER (Ug/Kk/Ky).

Within the hyperparameter search ranges defined in this study, and based on the preceding analysis of parameter influence, is the most critical hyperparameter for model training across the three low-resource languages and should be prioritized during optimization. The effects of r and are significant for certain languages and can serve as auxiliary adjustment parameters. The parameter p moderately affects the performance of Kk and Ky and can be tuned as needed. In contrast, shows unstable influence on model performance and can be kept at its default value. For the three experimental datasets, the recommended parameter ranges are: , , [2 × 10−4, 5 × 10−4]. In practical applications, further hyperparameter tuning should be performed experimentally, taking into account the specific characteristics of the dataset and validation set performance, to achieve optimal model performance and generalization.

5. Discussion

This study proposes a tuning method that integrates LoRA with the Optuna hyperparameter optimization framework and a dual-metric early stopping strategy, specifically designed for speech recognition tasks in low-resource languages. Through systematic experiments on Whisper for three low-resource languages (Ug, Kk, Ky), the results show that this method effectively improves the recognition performance of Whisper models.

Experiments show that LoRA fine-tuning substantially reduces GPU memory and computational requirements during training, as only approximately 1–3% of the parameters need to be updated. This makes it feasible to train models in low-memory hardware environments. The introduction of a dual-metric early-stopping mechanism further prevents overfitting and conserves computational resources. Hyperparameter combinations obtained through 50 rounds of search led to significant reductions in WER across all three languages, demonstrating the method’s effectiveness in resource-constrained settings.

The hyperparameter sensitivity analysis indicates that is the most critical factor influencing model performance across all three languages and should be prioritized for optimization. Parameters r, , and p show notable effects in certain languages and can be adjusted accordingly. In contrast, exhibits high instability in its impact on performance and can be left at its default value. These results highlight that hyperparameter sensitivity varies across languages, emphasizing the importance of task-adaptive hyperparameter optimization.

The proposed optimization method demonstrates stable performance across multilingual and resource-constrained scenarios, showing strong transferability. It offers valuable insights for speech recognition research in other minority or low-resource languages. Moreover, the hyperparameter configurations obtained through a single round of optimization can be directly reused in subsequent tasks, substantially reducing the time and computational costs associated with repeated training.

Although this approach achieves significant performance improvements, hyperparameter search for each language still requires over 100 h of training, resulting in substantial computational overhead. This indicates that achieving optimal performance in low-resource environments remains computationally demanding, highlighting a trade-off between resources and accuracy. When the optimization objective extends to more languages or larger models, existing methods may encounter limitations in computational resources and storage. Therefore, further research into the scalability and efficiency of these methods is essential.

Future work will explore more lightweight hyperparameter optimization strategies, such as Multi-Fidelity Hyperparameter Optimization (MF-HPO) [26], to reduce computational overhead and improve optimization efficiency while maintaining performance. Moreover, this study only conducted experiments on three Turkic low-resource languages. Future research will investigate the impact of interlingual similarity on model performance across additional tasks, aiming to validate the generalization capability of the proposed method in broader linguistic contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W. and J.B.; methodology, H.W., J.B. and C.G.; validation, H.W., J.B. and C.G.; formal analysis, J.B. and L.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W. and J.B.; writing—review and editing, M.Q. and B.H.; visualization, L.Y.; supervision, B.H.; project administration, H.W. and M.Q.; funding acquisition, M.Q. and H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by National Science Foundation grant 62261051.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This study uses publicly available speech datasets from three minority languages in the Xinjiang region of China as experimental data, including the Uyghur dataset THUYG-20 released by the Speech and Language Technology Center of Tsinghua University, which can be accessed at https://openslr.org/22/ (accessed on 9 December 2025); the Kyrgyz dataset from the Mozilla Foundation’s Common Voice 15 platform, available at https://commonvoice.mozilla.org/en/languages (accessed on 9 December 2025); and the Kazakh dataset from Google’s FLEURS dataset, available at https://huggingface.co/datasets/google/fleurs (accessed on 9 December 2025) Conneau, A.; et al. FLEURS: Few-Shot Learning Evaluation of Universal Representations of Speech. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT), Doha, Qatar, 2022, pp. 798–805. arXiv:2205.12446 [35]. These datasets are publicly available and can be accessed and downloaded from their respective platforms.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LoRA | Low-Rank Adaptation |

| ASR | Automatic Speech Recognition |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| TPE | Tree-structured Parzen Estimator |

| Ug | Uyghur |

| Ky | Kyrgyz |

| Kk | Kazakh |

| WER | Word Error Rate |

| DI | Direct Inference |

References

- Alharbi, S.; Alrazgan, M.; Alrashed, A.; Alnomasi, T.; Almojel, R.; Alharbi, R.; Alharbi, S.; Alturki, S.; Alshehri, F.; Almojil, M. Automatic speech recognition: Systematic literature review. Ieee Access 2021, 9, 131858–131876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, H.; Sitaram, S. A survey of multilingual models for automatic speech recognition. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.12576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldarmaki, H.; Ullah, A.; Ram, S.; Zaki, N. Unsupervised automatic speech recognition: A review. Speech Commun. 2022, 139, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap, V.; Xu, Q.; Sriram, A.; Synnaeve, G.; Collobert, R. Mls: A large-scale multilingual dataset for speech research. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.03411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, A.; Wang, C.; Tjandra, A.; Lakhotia, K.; Xu, Q.; Goyal, N.; Singh, K.; Von Platen, P.; Saraf, Y.; Pino, J.; et al. XLS-R: Self-supervised cross-lingual speech representation learning at scale. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.09296. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, W.Q. Improving automatic speech recognition performance for low-resource languages with self-supervised models. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2022, 16, 1227–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slam, W.; Li, Y.; Urouvas, N. Frontier research on low-resource speech recognition technology. Sensors 2023, 23, 9096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuxiong, Q.; Lianhai, Z. DNN-based feature extraction technique for low-resource speech recognition. J. Autom. 2017, 43, 1208–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2020, 404, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, F.; Yang, W.; Peng, S.; Zhou, J. A Survey of Convolutional Neural Networks: Analysis, Applications, and Prospects. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 33, 6999–7019. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9451544 (accessed on 1 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Prabhavalkar, R.; Hori, T.; Sainath, T.N.; Schlüter, R.; Watanabe, S. End-to-end speech recognition: A survey. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech, Lang. Process. 2023, 32, 325–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Yan, C.; Li, Q.; Peng, X. From large language models to large multimodal models: A literature review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; et al. A survey of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.18223. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Qu, D. Exploration of Whisper fine-tuning strategies for low-resource ASR. EURASIP J. Audio Speech Music. Process. 2024, 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Xu, T.; Brockman, G.; McLeavey, C.; Sutskever, I. Robust speech recognition via large-scale weak supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 28492–28518. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Gao, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.Q. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning for large models: A comprehensive survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.14608. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Jiang, L.; Pan, S.; Cai, R.; Yang, S.; Yang, F. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning in large models: A survey of methodologies. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.19878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, B.; Su, X.; Tarkoma, S.; Hui, P. Helora: Lora-heterogeneous federated fine-tuning for foundation models. ACM Trans. Internet Technol. 2025, 25, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Aitchison, L.; Rudolph, M. LoRA ensembles for large language model fine-tuning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.00035. [Google Scholar]

- Sicard, C.; Pyszkowski, K.; Gillioz, V. Spaiche: Extending state-of-the-art ASR models to Swiss German dialects. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.11075. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Qin, Y.; Peng, Z.; Lee, T. Sparsely shared lora on whisper for child speech recognition. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024-2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; pp. 11751–11755. [Google Scholar]

- Polat, H.; Turan, A.K.; Koçak, C.; Ulaş, H.B. Implementation of a Whisper Architecture-Based Turkish Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) System and Evaluation of the Effect of Fine-Tuning with a Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) Adapter on Its Performance. Electronics 2024, 13, 4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 2623–2631. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas, P.; Katarya, R. hyOPTXg: OPTUNA hyper-parameter optimization framework for predicting cardiovascular disease using XGBoost. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 73, 103456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.H.; Lin, Y.L.; Liu, Y.H.; Lai, J.P.; Yang, W.C.; Hou, H.P.; Pai, P.F. The use of machine learning models with Optuna in disease prediction. Electronics 2024, 13, 4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, M.V.; Mosquera, Y.D.; Pena, F.J.R.; Bilbao, V.M.D. Early stopping by correlating online indicators in neural networks. Neural Netw. 2023, 159, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Biderman, D.; Portes, J.; Ortiz, J.J.G.; Paul, M.; Greengard, P.; Jennings, C.; King, D.; Havens, S.; Chiley, V.; Frankle, J.; et al. Lora learns less and forgets less. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.09673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuttleworth, R.; Andreas, J.; Torralba, A.; Sharma, P. Lora vs full fine-tuning: An illusion of equivalence. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.21228. [Google Scholar]

- Roze, A.; Yin, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, D.; Hamdulla, A. THUGY20: A free Uyghur speech database. In Proceedings of the NCMMSC’15, Tianjin, China, 1–11 January 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ardila, R.; Branson, M.; Davis, K.; Henretty, M.; Kohler, M.; Meyer, J.; Morais, R.; Saunders, L.; Tyers, F.M.; Weber, G. Common voice: A massively-multilingual speech corpus. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.06670. [Google Scholar]

- Conneau, A.; Ma, M.; Khanuja, S.; Zhang, Y.; Axelrod, V.; Dalmia, S.; Riesa, J.; Rivera, C.; Bapna, A. Fleurs: Few-shot learning evaluation of universal representations of speech. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT), Doha, Qatar, 9–12 January 2023; pp. 798–805. [Google Scholar]

- Mangrulkar, S.; Gugger, S.; Debut, L.; Belkada, Y.; Paul, S.; Bossan, B. PEFT: State-of-the-art Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning Methods. 2022. Available online: https://github.com/huggingface/peft (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Why comparing single performance scores does not allow to draw conclusions about machine learning approaches. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.09578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, A. More accurate tests for the statistical significance of result differences. arXiv 2000, arXiv:cs/0008005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).