Abstract

Wind and solar power generation, a clean and renewable energy source, relies on stable foundations in Gobi soil regions, where the mechanical properties of the local soil are critical. This study investigated the shear behavior of Gobi soil from Dabancheng District, Urumqi, China, through 60 direct shear tests, analyzing the effects of water content (4%, 6%, 8%, 10.5%, 12.5%) and compaction degree (87%, 90%, 95%). Results indicate that water content governs the strain response: low moisture leads to strain-softening, while optimum or higher moisture causes strain-hardening. The relative softening coefficient decreases with rising water content and vertical stress but increases with compaction. Peak shear strength grows with vertical stress and compaction, yet peaks and then declines as water content increases. Shear modulus improves significantly under low water content and high compaction. Cohesion initially rises and then falls with increasing water content, while the internal friction angle decreases continuously. Both generally increase with compaction, though cohesion gains diminish at high moisture levels. Binary quadratic equations were established to relate mechanical parameters to compaction and water content. The findings provide a reference for selecting shallow foundation design parameters for wind and solar installations in Gobi regions.

1. Introduction

Driven by the global strategic goals of carbon peak and carbon neutrality, the energy structure is undergoing a fundamental transformation dominated by renewable energy. Among these sources, wind and solar power have emerged as core forces in the energy transition due to their clean and sustainable nature [1,2]. China has committed to achieving carbon peaking by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060, which makes the development of renewable energy a critical pathway [3]. The vast Gobi regions in northwestern China, characterized by unique solar and wind resources as well as extensive unused land, are becoming ideal locations for large-scale wind and photovoltaic power bases. Developing renewable energy in the Gobi regions not only facilitates the adjustment of the national energy structure but also transforms the energy advantages of the western regions into economic benefits [4]. However, the specific engineering geological conditions in the Gobi areas, particularly the mechanical properties of the Gobi soil, which serves as the bearing stratum for foundations, directly impact the long-term stability and safety of wind and solar power infrastructure. Therefore, in-depth research on foundation issues in the construction of wind and photovoltaic power infrastructure is essential to overcome the technical bottlenecks associated with new energy projects in this region [5].

Gobi soil, as the main foundation bearing stratum for wind and solar power foundations, has mechanical properties that are directly related to the overall safety of the superstructure. Different from conventional soil, Gobi soil is a typical coarse-grained soil, characterized by a wide range of particle size distribution and strong spatial variability [6,7]. Its engineering geological properties are significantly influenced by its material composition and initial structural state. The degree of compaction is an important index for evaluating the soil compaction degree, and it exerts a significant influence on the soil’s strength and deformation characteristics [8]. Chen et al. [9] also noted in their research that coarse-grained red sandy soil is prone to particle breakage during compaction, which in turn affects the stability of the subgrade; thus, controlling the degree of compaction is crucial. For sandy gravel soil, the degree of compaction also affects its shear strength [10]. Water content is another key factor that affects the mechanical properties of soil; especially in arid and semi-arid regions, the mechanical properties of Gobi soil are highly sensitive to changes in water content [11,12,13]. Zhang et al. [14] showed that water content significantly influences the shear strength of coarse-grained soils. Under different conditions of degree of saturation, coarse-grained soils may exhibit different behaviors ranging from strain hardening to strain softening.

From the perspective of engineering application, the post-construction settlement of wind farm foundations in desert areas is closely related to the degree of compaction and water content state of foundation soil, and the precise control of these two factors is the key to ensuring foundation quality [15]. The degree of compaction directly affects the density and strength of soil, while water content significantly alters the shear strength of soil [16]. Therefore, during the construction of wind farm foundations, the coupling effect of compaction degree and water content must be fully considered to ensure the long-term stability of the foundation [17]. The degree of compaction is an important index for evaluating the compaction degree of soil; high compaction degree can effectively improve the bearing capacity of soil and reduce settlement. Studies have shown that the mechanical properties of desert sand can be significantly improved and its bearing capacity enhanced by controlling compactive effort [18]. Compactive effort can change the structure of soil and increase the contact area between particles, thereby improving the overall strength of soil [19]. Water content exerts a significant regulatory effect on the shear strength of sandy soil [20]. Within a certain range, appropriately increasing the water content can enhance the cohesion between soil particles and improve the shear strength of soil. However, an excessively high water content may lead to an increase in soil pore water pressure and a decrease in effective stress, thereby reducing the shear strength of soil [21]. Therefore, during construction, water content needs to be controlled according to the actual conditions to achieve the optimal compaction effect and foundation strength [20,22]. The degree of compaction and water content have a coupling effect on the engineering behavior of gravelly soil [23]. Gravelly soil is a common foundation material, and its engineering properties are affected by multiple factors. Studies have shown that there is a complex interaction between compaction degree and water content, which affects the compaction effect, strength, and deformation characteristics of gravelly soil [17,24].

It is worth noting that this coupling effect is particularly critical for the stiffness characterization of coarse-grained soils. Among these factors, the elastic modulus has a close relationship with water content, degree of compaction, and particle gradation. The elastic modulus is a key parameter describing soil stiffness, and it is significantly influenced by water content and degree of compaction. Studies have shown that changes in water content alter the effective stress of sand-gravel mixtures, thereby affecting their shear strength [25,26]. For instance, increased water reduces the cohesion between soil particles, lowering the overall strength of the soil [27]. The degree of compaction directly affects the porosity and density of the soil, which in turn influences its stiffness. The higher the degree of compaction, the tighter the contact between soil particles, and the greater the stiffness [28]. Additionally, as an inherent property of soil, particle gradation exerts an important influence on compaction characteristics [29,30]. Good gradation enables soil particles to arrange more closely, reduces porosity, improves compaction effect, and thereby enhances the stiffness and stability of the soil [31]. Studies have indicated that unreasonable particle gradation leads to difficulties in soil compaction and reduces its mechanical properties [32]. Differences also exist in the strain softening behavior of coarse-grained soils under different compaction conditions [33]. Strain softening refers to a phenomenon where the strength of soil gradually decreases as strain increases after reaching the peak strength. Soils with lower compaction degrees have looser contact between particles and are prone to strain softening [34]. In contrast, soils with higher compaction degrees exhibit relatively weaker strain softening due to the tight arrangement of particles [35,36]. From a microscopic mechanism perspective, water content affects the shear strength of sand-gravel mixtures by influencing the effective stress, cohesion, and friction between soil particles. The presence of water reduces the friction between soil particles, leading to a decrease in shear strength [37,38]. However, in some cases, an appropriate amount of water can increase the cohesion between soil particles, thereby improving shear strength. Therefore, the influence of water content on the shear strength of sand-gravel mixtures is a complex process that requires the comprehensive consideration of multiple factors.

In summary, despite the fact that some scholars have achieved fruitful results in the field of coarse-grained soil mechanics, the systematic investigation into the coupling effect of compaction degree and water content remains relatively insufficient for the specific soil type of Gobi soil. In particular, in the specific engineering context of wind and solar power foundations, clarifying the law of the synergistic influence of these two factors on the full-process stress–strain relationship, peak strength, elastic modulus, and shear strength parameters (cohesion and internal friction angle) of Gobi soil, and revealing its microscopic mechanism, are of great significance for formulating scientific foundation design and construction control standards.

This study takes Gobi soil from the wind and solar power foundation in Dabancheng, Urumqi City, Xinjiang, China, as the research object. Through systematic mechanical tests, its main research objectives are as follows: (1) To reveal the shear mechanical behavior and strain characteristics (hardening/softening) of Gobi soil under different combinations of compaction degree and water content; (2) To quantitatively analyze the law of coupling influence of compaction degree and water content on key mechanical parameters such as peak shear stress, elastic modulus, cohesion, and internal friction angle; (3) To establish a practical empirical formula for predicting the mechanical parameters of Gobi soil based on test results. Ultimately, it provides direct theoretical basis and data support for the optimized design of wind and solar power foundations in Gobi regions. For the first time, the study establishes a quantitative model linking Gobi soil mechanical parameters to moisture content and compaction degree, enabling accurate prediction and control of its engineering behavior and shifting foundation design from “empirical guess” to “scientific calculation”.

2. Materials

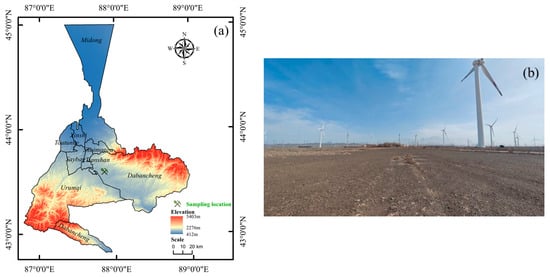

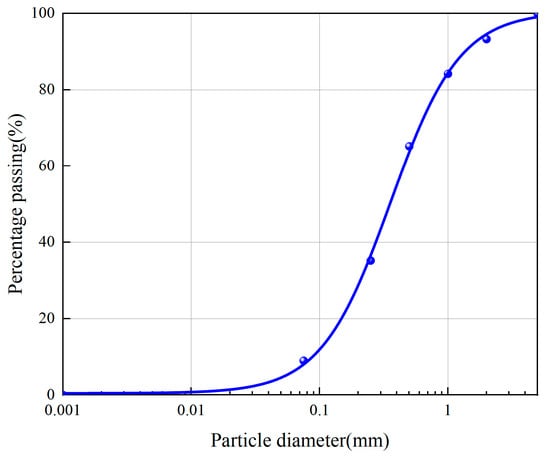

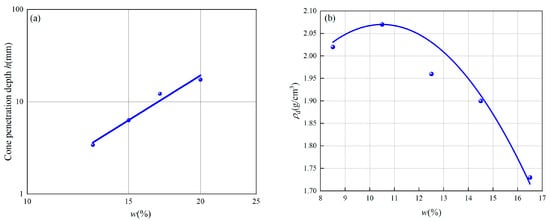

The Gobi soil used in this study was sampled from a wind farm in Dabancheng District, Urumqi City, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China, and the sampling location is shown in Figure 1. Sieve analysis was performed on the Gobi soil using a GZS-1 high-frequency vibrating sieve to obtain its gradation curve (Figure 2). The gradation curve indicates that Gobi soil contains 9.0% fine particles (particle size less than 0.075 mm), 84.3% sand particles (particle size between 0.075 mm and 2 mm), and 6.7% fine gravel particles (particle size between 2 mm and 5 mm). Through the Atterberg limits test, the liquid limit water content of the Gobi soil was measured as 16.3% (with a cone penetration depth of 10 mm), and the plastic limit water content was 12.5% (with a cone penetration depth of 2 mm) (Figure 3a). Via the standard Proctor compaction test, the optimum water content of the Gobi soil was determined to be 10.5%, and the maximum dry density was 2.07 g/cm3 (Figure 3b). The engineering properties of the Gobi soil are presented in Table 1. The main mineral composition of the Gobi soil was analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD), and the results are listed in Table 2; its main chemical composition was determined via X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF), with the results shown in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of sampling: (a) topographic map of the sampling site; (b) Gobi soil.

Figure 2.

Grain size distribution curve of Gobi soil.

Figure 3.

Physical properties of Gobi soil: (a) liquid-plastic limit water contents; (b) optimal water contents and maximum dry density.

Table 1.

Engineering properties of Gobi soil.

Table 2.

Relative content of primary minerals for Gobi soil.

Table 3.

Relative content of primary chemical component for Gobi soil.

3. Sample Preparation and Tests

3.1. Sample Preparation

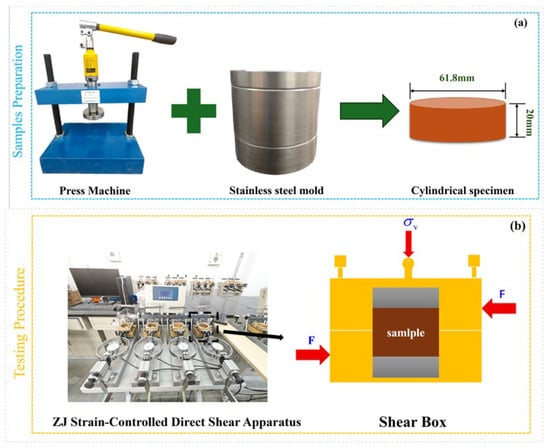

To investigate the effects of different compaction degrees and water contents on the direct shear mechanical properties of Gobi soil, it was necessary to prepare standard ring specimens. First, the field-collected Gobi soil was thoroughly air-dried in the laboratory. Considering the actual requirements of the site foundation, the compaction degrees were set to 87%, 90%, and 95%, respectively. Given that the local climate is arid with little rainfall, the water contents should not be too high; thus, the specimen water contents for the test were set to 4%, 6%, 8%, 10.5%, and 12.5%, respectively (Table 4). A standard ring sample mold with a diameter of 61.8 mm and a height of 20 mm was used to prepare specimens via the static pressure method under the optimum water content condition (wopt = 10.5%) (Figure 4a). For specimens with water contents of 4%, 6%, and 8%, the prepared specimens were further dried to the target water contents. For specimens with a water content of 12.5%, distilled water was uniformly sprayed onto the prepared specimens to ensure uniform water distribution and thus reach the target water contents. Subsequently, all ring specimens were placed in a constant temperature and humidity curing box for 48 h to ensure stable internal water of the specimens, which were then ready for subsequent direct shear tests.

Table 4.

Sample properties and design of direct shear tests.

Figure 4.

Procedures and instruments used for tests: (a) compacted specimen; (b) direct shear test.

3.2. Direct Shear Test

According to “Standard for Geotechnical testing method” (GB/T 50123-2019 [39]), the direct shear tests on Gobi soil were conducted using a ZJ strain-controlled automatic direct shear apparatus (Manufactured by Nanjing Soil Instrument Factory Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) (Figure 4b). The prepared standard ring specimens (with a diameter of 61.8 mm and a height of 20 mm) were carefully placed into the shear box of the direct shear apparatus, ensuring that the specimens were in close contact with the upper and lower permeable stones of the shear box. With reference to standard requirements and research needs, the vertical pressures were set to 50 kPa, 100 kPa, 200 kPa, and 400 kPa, respectively, and the shear rate was set to 1.2 mm/min. During the test, the preset vertical pressure was first applied to the specimen; after the specimen’s deformation stabilized, the direct shear apparatus was activated to perform horizontal shearing until shear failure occurred in the specimen. To better observe the residual strength of the soil sample, the shear deformation was set to 6 mm.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Shear Stress—Displacement Relationship

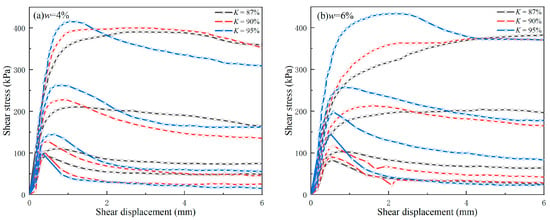

Figure 5 illustrates the shear stress–displacement relationships of specimens with varying water contents under different compaction degrees. At low water contents (e.g., 4%, 6%), the curves exhibited strain-softening behavior, attributable to strong interparticle adsorption and cohesion. At intermediate water content (e.g., 8%), strain-softening persisted under low normal stresses (e.g., 50 kPa, 100 kPa); however, under high normal stresses (e.g., 200 kPa, 400 kPa), the behavior transitioned to strain-hardening. At and above the optimum water content (e.g., 10.5%, 12.5%), reduced effective stress and enhanced lubricating effects between soil particles led to predominant strain-hardening.

Figure 5.

Shear stress–shear displacement curves of samples with different water contents.

The compaction degree directly influences the interparticle contact and porosity. A higher compaction degree results in tighter particle packing and greater cohesion, thereby enhancing the shear strength. Studies indicate that highly compacted soils are more prone to strain-softening, whereas loosely compacted soils tend to exhibit strain-hardening.

Normal stress is another critical factor governing shear behavior. Under low normal stress, soils typically display strain-softening, the reason being that the additional strength component provided by the dominant shearing dilation effect of soil particles is unstable and will be exhausted with the development of plastic deformation, leading to strength decay after the peak and strain softening. Conversely, under high normal stress, the tendency for soil particles to dilate is completely suppressed and even forced into shear contraction, leading to strain-hardening.

Consequently, strain-softening is commonly associated with low water content and high compaction degree, whereas strain-hardening is prone to occur under high water content and low compaction degree. These findings align with observations reported by other researchers in soil mechanics [40,41].

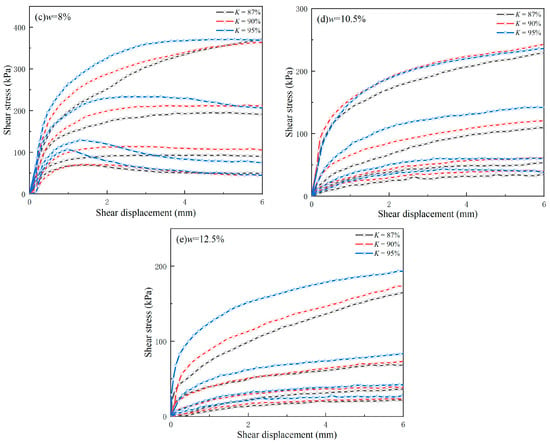

To quantitatively describe the strain softening characteristics of the specimens, the relative softening coefficient β is introduced, and its calculation formula is as follows:

where β is the relative softening coefficient; qmax is the peak shear stress (kPa); and qr is the residual shear strength (kPa), corresponding here to the shear stress at a shear displacement of 6 mm, which equates to an axial strain of 9.7%.

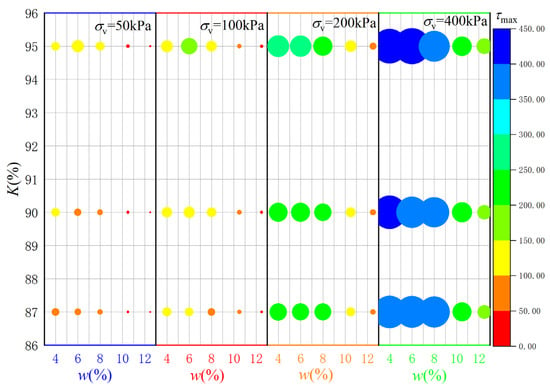

The distribution of the relative softening coefficient β for each specimen, calculated using Equation (1), is shown in Figure 6. The coefficient β of the specimen is influenced collectively by the compaction degree, water content and vertical stress. Under identical vertical stress and compaction conditions, β decreases as the water content increases. This trend aligns with the observed shear stress–displacement relationships, where a more pronounced strain-softening behavior is evident at higher water contents. Furthermore, β decreases with increasing vertical stress (i.e., β gradually declines for a given water content and compaction degree as σv rises). This reduction corresponds to a shear stress–displacement curve that more closely approximates a “weak strain-hardening” pattern, indicating that high vertical stress suppresses rapid strength decay, resulting in a more gradual strength reduction process.

Figure 6.

Variation of softening coefficient with compaction degree and water content.

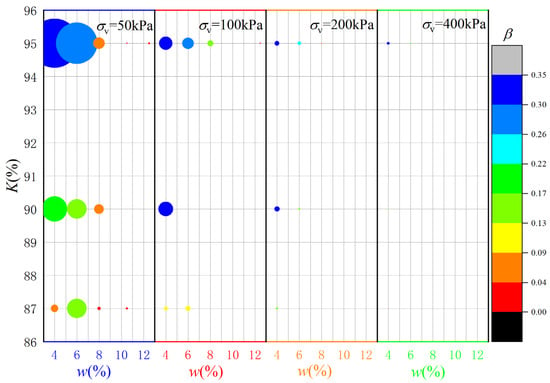

4.2. Peak Shear Stress Variations

4.2.1. Water Content Factor

The variation of peak shear stress (τmax) with water content under direct shear testing is shown in Figure 7. Under identical compaction degree and vertical stress conditions, τmax exhibits a clear dependence on water content. At excessively low water content, the insufficient water film between soil particles results in weak cohesion. As water content increases, an appropriate amount of water enhances interparticle bonding—via thicker water films or improved pore structure—leading to an increase in τmax. However, when the water content becomes too high, excess water induces a lubricating effect or loosens the soil structure, resulting in a decline in τmax [20,42,43,44,45].

Figure 7.

Variation of peak shear stress with water content.

4.2.2. Compaction Degree Factor

The variation of peak shear stress (τmax) with compaction degree in direct shear tests is shown in Figure 8. Under identical water content and vertical stress conditions, τmax exhibits a significant dependence on the degree of compaction. A higher compaction degree results in a denser internal soil structure, reduced porosity, and a corresponding increase in interparticle contact area and interlocking force. Consequently, greater frictional resistance and cohesion must be overcome during shearing, leading to an enhanced peak shear strength [46].

Figure 8.

Variation of peak shear stress with compaction degree.

Existing research establishes that the shear strength of soil is primarily governed by its cohesion and internal friction angle [43]. Cohesion represents the bonding strength between soil particles, while the internal friction angle reflects their frictional characteristics [47,48]. Variations in water content and compaction degree significantly influence these two parameters, thereby altering the soil’s overall shear strength [20,44].

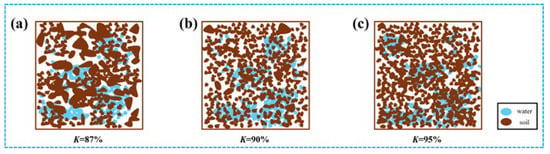

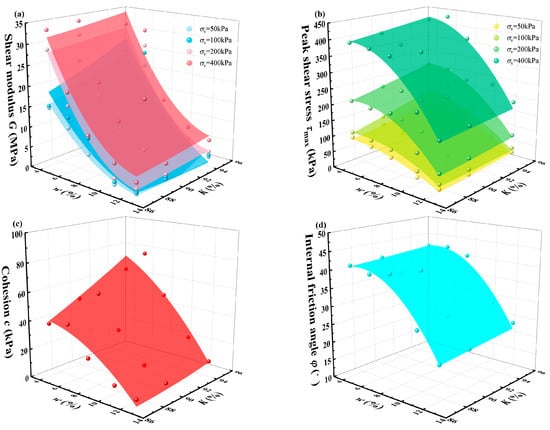

4.3. Shear Modulus Variations

Shear modulus is a crucial mechanical parameter that must be considered when calculating soil deformation. Based on previous similar research results, this study selected the stress corresponding to a shear strain of 2% to calculate the elastic shear modulus [49]. The calculation formula is as follows:

where τ2% is the shear stress at a shear strain of 2% (kPa); γ2% is the 2% shear strain; τ0 is the initial shear stress (kPa); and γ0 is the initial shear strain.

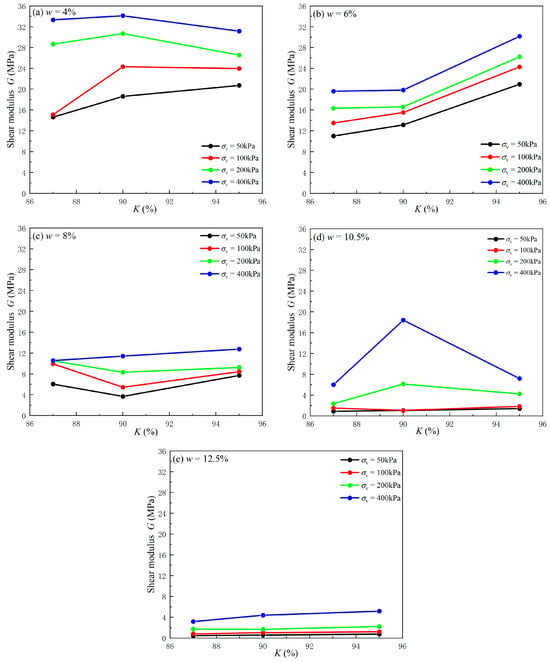

The influence of compaction degree on the elastic shear modulus under different water content conditions is shown in Figure 9. The soil shear modulus is affected jointly by the water content, compaction degree, and vertical stress, exhibiting distinct stage-specific characteristics. At low water contents (e.g., w = 4%, w = 6%), the shear modulus generally increases with the compaction degree, and it reaches higher values at greater compaction degrees and under higher vertical stresses. This is attributed to the denser internal structure, reduced porosity, and enhanced interparticle contact and interlocking resulting from increased compaction and confining pressure, which collectively improve the shear resistance of the soil [50,51].

Figure 9.

Variation of shear modulus with compaction degree under different water contents.

As the water content approaches the optimum level (e.g., w = 8%), the rate of increase in shear modulus with compaction degree and vertical stress slows noticeably, indicating a diminished enhancing effect of these two factors on the modulus [52,53].

At the optimum water content (e.g., w = 10.5%), the shear modulus exhibits more complex behavior [54]. Under high vertical stress, the modulus first increases and then decreases with the compaction degree, peaking at K = 90% [53]. This suggests that excessive compaction may disrupt the internal soil structure, leading to a reduction in the shear modulus. In contrast, under low vertical stress, the variation of the modulus with compaction degree is relatively modest, implying a lesser influence of compaction under such conditions [20].

At high water content (e.g., w = 12.5%), the soil exhibits very low shear modulus values under all levels of vertical stress, with little variation with compaction degree [55]. Here, the water content becomes the dominant factor; the excess water fills the interparticle pores, substantially weakening the interparticle bonding forces and resulting in a marked decrease in overall soil stiffness. Under these conditions, the soil is more likely to exhibit fluid-plastic characteristics [56,57].

4.4. Shear Strength Parameters Variations

4.4.1. Water Content Factor

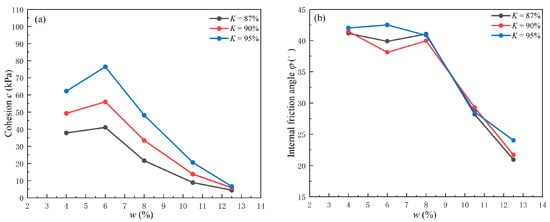

Cohesion and internal friction angle are key geotechnical parameters for evaluating soil shear strength and engineering stability. The variations of cohesion and internal friction angle of soil under different water content conditions are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Variation of shear strength parameters with water content: (a) cohesion; (b) internal friction angle.

As fundamental parameters describing soil mechanical behavior, cohesion and internal friction angle are influenced by several factors, among which water content plays a critical role. In the low water content stage (w = 4%, w = 6%), cohesion increases with rising water content, as water fills the interparticle pores and enhances cementation or bonding between particles. With a further increase in water content, the growing volume of free water in the soil leads to a notable decrease in cohesion. Beyond the optimum water content (w = 10.5%), the cohesion tends to stabilize [43,58].

The internal friction angle, which reflects interparticle friction and mechanical interlocking, exhibits a continuous decreasing trend with increasing water content. At low to medium water contents stages (w = 4%, w = 6%, w = 8%), the decline is relatively gradual. As water content rises, the thickening of water films around soil particles enhances lubrication, thereby reducing sliding and interlocking friction between particles and resulting in a consistent reduction in the internal friction angle. When the water content exceeds 8%, the internal friction angle decreases more markedly [43,59].

In summary, the influence of water content on the shear strength parameters of soil demonstrates a clear and consistent trend.

4.4.2. Compaction Degree Factor

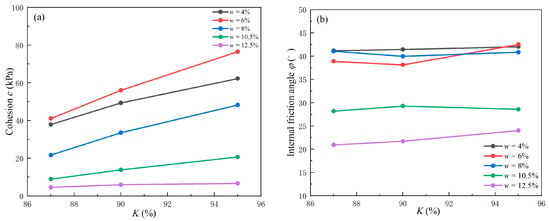

The variations of cohesion and internal friction angle with compaction degree are presented in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Variation of shear strength parameters with compaction degree: (a) cohesion; (b) internal friction angle.

Under a constant water content, cohesion generally increases with the compaction degree. This increasing trend is more pronounced at moderate water contents, whereas at high water contents, cohesion values remain relatively low and increase only marginally with higher compaction. This behavior is attributed to the denser particle packing and enhanced interparticle bonding induced by compaction. At high water content, however, the lubricating effect of water films diminishes the extent of this strengthening [43,54,60,61].

The internal friction angle, which reflects interparticle friction and interlocking, generally exhibits a slight increase or remains stable with increasing compaction degree under a given water content. Soils with lower initial water content demonstrate higher initial internal friction angles. In contrast, at high water content, the initial internal friction angle is lower but still shows a gradual increase with compaction. Moreover, the difference in the internal friction angle among specimens with different water contents tends to narrow as the compaction degree increases [43,61,62].

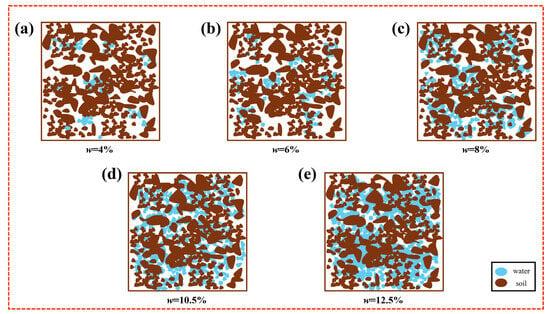

4.5. Mechanisms of Mechanical Parameter Change

At low water content (Figure 12a,b), the extremely thin water films on soil particles result in direct intergranular contact, where friction and interlocking dominate the mechanical behavior. The lubricating effect of water is negligible, leading to limited particle sliding and consequently higher shear strength of the soil [63,64]. At medium water content (Figure 12c), the thickening water films begin to exert a noticeable lubricating effect, reducing the sliding friction between particles and facilitating their relative movement, thereby enhancing the soil’s plastic deformation capacity. Since the pores are not excessively saturated, effective interparticle contact—the basis for interlocking and frictional resistance—remains reasonably well preserved, allowing the mechanical strength to be maintained at a relatively favorable level [20]. At high water content (Figure 12d,e), the combination of overly thick water films and abundant free water in the pores leads to a dual weakening effect: first, lubrication is further enhanced, significantly reducing interparticle friction; second, the presence of free water increases the pore water pressure, which diminishes effective interparticle contact and stress transmission while also disrupting the interlocked soil skeleton. These factors collectively result in reduced mechanical strength and promote larger deformations [65].

Figure 12.

Water content at the microscopic scale.

In summary, the role of water transitions from initially assisting particle contact at low levels, to dominating lubrication and enhancing plasticity at medium levels, and finally to reducing strength through excessive saturation, which undermines effective stress and particle interlocking.

An increase in compaction degree leads to a greater number of soil particles and a denser arrangement per unit volume (as illustrated in Figure 13a–c, where the particle volume fraction rises noticeably). This enhanced packing significantly increases the number of particle contact points and the total contact area. The resulting tighter interparticle contacts strengthen both the frictional resistance and the mechanical interlocking among particles. When external loads (such as shear or compression) are applied, greater friction and interlocking must be overcome for particles to displace relative to one another, thereby markedly improving the soil’s shear strength. Furthermore, the dense particle configuration considerably reduces porosity, which diminishes the soil’s compressibility. Consequently, it becomes more difficult for particles to rearrange and for pores to be further compressed under load, effectively limiting overall deformation and enhancing the structural integrity and stability of the soil mass [38,66,67].

Figure 13.

Compaction degrees at the microscopic scale.

In summary, the increase in compaction degree substantially raises the number of interparticle contacts and the contact area, strengthening mechanical interactions between particles. This microstructural enhancement ultimately manifests as improved strength, reduced compressibility, and superior mechanical performance.

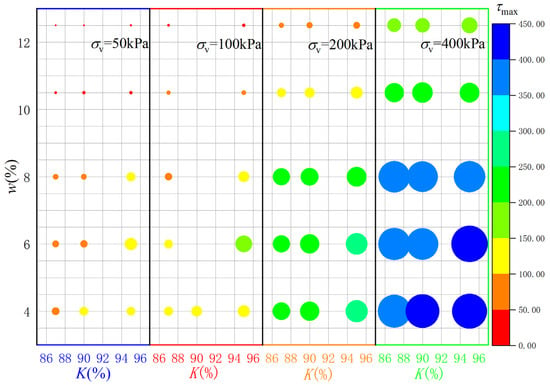

4.6. Empirical Formulations of Mechanical Parameters

Establishing empirical relationships between mechanical parameters and certain physical quantities is of great practical significance for engineering construction and design [68]. In this study, the mechanical parameters of Gobi soil were mainly affected by compaction degree and water contents. Figure 14 shows the relationships between mechanical parameters (including elastic shear modulus, peak shear stress, cohesion, and internal friction angle) and compaction degree/water contents. The distribution of data points exhibits a parabola-like characteristic; therefore, binary quadratic polynomial equations were used to fit the test results of mechanical parameters under different test conditions. The fitting process was performed using Origin and the empirical fitting equations for the mechanical parameters are presented in Table 5. The coefficient of determination (R2) of all fitting equations was greater than 0.88, indicating that the parabolic surface can well describe the relationship between mechanical parameters and test conditions. However, these empirical relationships are derived only from limited test data, and more universal laws still need to be verified through further research and engineering practice.

Figure 14.

Empirical relationships between mechanical parameters and the number of compaction degrees as well as water contents: (a) shear modulus; (b) peak shear stress; (c) cohesion; (d) internal friction angle.

Table 5.

Fitting results for the mechanical parameters.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated Gobi soil from wind-solar power station foundations in Dabancheng District, Urumqi, Xinjiang, systematically analyzing the effects of compaction degree and water content on its mechanical properties. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- The shear stress–displacement relationship of Gobi soil is governed by water content, transitioning from strain-softening to strain-hardening as water content increases. The relative softening coefficient decreases with higher water content and vertical stress, but increases with greater compaction degree.

- (2)

- Mechanical parameters improve with increasing compaction degree and vertical stress, while water content exhibits an initial increase followed by a decrease in its influence. When compaction degree rises from 87% to 95%, the peak shear stress at optimal water content shows a maximum increase of 35%. The elastic shear modulus demonstrates particularly significant growth under conditions of low water content, high compaction degree, and high vertical stress.

- (3)

- Compaction degree and water content affect mechanical properties by altering particle contact states and water film effects: high compaction enhances particle interlocking and contact; appropriate water content optimizes water film bonding, while excessive water generates lubrication effects that reduce strength.

- (4)

- Gobi soil mechanical parameters can be accurately fitted using binary quadratic equations. For engineering applications: water content should be maintained between 4–8% with compaction degree not less than 90%, providing crucial parameter guidance for wind-solar power foundation design in Gobi regions.

The study area features a temperate continental climate with cold winters and hot summers. Therefore, in future research, we will consider the impact of environmental factors on the mechanical behavior of Gobi soils, such as wet–dry cycles and freeze–thaw cycles.

Author Contributions

Methodology, X.L.; Conceptualization, X.L.; Writing—review and editing, X.L.; Funding acquisition, X.L.; Writing—original draft, J.W. (Jiayu Wang); Formal analysis, J.W. (Jiayu Wang) and J.W. (Jin Wu); Data curation, J.W. (Jiayu Wang); Validation, J.W. (Jin Wu). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The “Young Doctor” Fund Project of the Third Batch of Tianchi Talent Introduction Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (Grant No. 5105250182b).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express sincere thanks to the editor and anonymous reviewers for their constructive and professional comments and suggestions regarding this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Olodu, D.D.; Ihenyen, O.I.; Inegbedion, F. Advances in renewable energy systems: Integrating solar, wind, and hydropower for a carbon-neutral future. Int. J. New Find. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2025, 3, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Majumder, S.; Huang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Chang, P.; Hill, D.J.; Shahidehpour, M. The role of electric grid research in addressing climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.J. Key technologies and development challenges of high-proportion renewable energy power systems. Highlights Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 29, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enebish, N. Developing very large scale solar power plants in the Gobi desert to contribute for north east Asia’s energy transition. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 53rd Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 June 2025; pp. 842–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, H.; Saudi, G.; Aal, A.A.A. Geological, geotechnical and geophysical aspects of zafarana wind farms sites and their expansion at Gabel El Zeit sites Egypt. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 974, 12005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouakou, N.M.; Cuisinier, O.; Masrouri, F. Estimation of the shear strength of coarse-grained soils with fine particles. Transp. Geotech. 2020, 25, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Miao, F.S.; Wu, Y.P.; Dias, D.; Li, L.W. Combing soil spatial variation and weakening of the groundwater fluctuation zone for the probabilistic stability analysis of a riverside landslide in the Three Gorges Reservoir area. Landslides 2023, 20, 1013–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsuoka, F.; Hashimoto, T.; Tateyama, K. Soil stiffness as a function of dry density and the degree of saturation for compaction control. Soils Found. 2021, 61, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Zhang, Y.J.; Yang, Y.X.; Yang, B.; Huang, B.C.; Ji, X.P. Influence of coarse grain content on the mechanical properties of red sandstone soil. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Shi, B.L.; Li, J.L.; Li, S.S.; He, X.B. Shear strength of purple soil bunds under different soil water contents and dry densities: A case study in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area, China. CATENA 2018, 166, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Wang, H.F.; Hu, D.W. Influence of moisture content and grain composition on shear strength of slightly dense gravel soil and bearing capacity of foundation. J. Chongqing Jianzhu Univ. 2017, 39, 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Z.J.; Guo, Y.H.; Mao, S.L.; Zhang, W. Experimental study on shear strength parameters of round gravel soils in plateau alluvial-lacustrine deposits and its application. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.D.; She, D.L.; Sun, X.Q.; Tang, S.Q.; Zheng, Y.P. Analysis of unsaturated shear strength and slope stability considering soil desalinization in a reclamation area in China. CATENA 2021, 196, 104949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Q.; Luo, Y.; Yuan, S.Y.; Zhou, Y.R.; Zhou, Q.; Zeng, F.R.; Feng, W. Shear characteristics of gravel soil with different fillers. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 962372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Wen, T.; Mi, H.Z.; Ying, S.; Yang, P. Diseases and control methods of coarse-grained salty soil foundation of wind electricity engineering foundation in Hexi region. J. Lanzhou Jiaotong Univ. 2014, 33, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.B.; Zhang, H.Z.; Wang, J. Test study on the compressive strength properties of compacted clayey soil. Key Eng. Mater. 2016, 703, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.F.; Wang, H.B.; Wang, L.; Wang, K.; Hu, P. The Study on the Characteristics of Compaction and the Standard of Compaction Control of Gravel Soil for Construction of the Changheba Hydropower Project. Yunnan Water Power 2014, 30, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Youwai, S.; Detcheewa, S. Predicting rapid impact compaction of soil using a parallel transformer and long short-term memory architecture for sequential soil profile encoding. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 139, 109664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaivan, H.S.; Sridharan, A. Comparison of reduced modified proctor vs modified proctor. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2020, 38, 6891–6897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.P.; Zhan, Y.Y.; Lin, J.S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.H.; Jiang, F.S. Effect of soil moisture content on the shear strength of dicranopteris linearis-rooted soil in different soil layers of collapsing wall. Forests 2024, 15, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.R.; Li, F.H.; Lü, W. Effects of freeze-thaw status and initial water content on soil mechanical properties. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2017, 33, 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Aventian, G.D.; Satyanaga, A.; Sagu, A.; Serikbek, B.; Pernebekova, G.; Aubakirova, B.; Zhai, Q.; Kim, J. Analytical and Finite-Element-Method-Based Analyses of Pile Shaft Capacity Subjected to Rainfall Infiltration. Sustainability 2023, 16, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.D.; Wang, W.C.; Liu, J.; Ji, K. Test research on compaction effect of expressway embankment with sand-gravel-cobble mixture. Rock Soil Mech. 2012, 1, 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, W.-J.; Phantachang, T. Effects of gravel content on shear resistance of gravelly soils. Eng. Geol. 2016, 207, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahyari, N.; Maleki, M. Investigation into small-strain shear modulus of sand–gravel mixtures in different moisture conditions and its correlation with static stiffness modulus. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 2022, 16, 962–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.Y.; Cui, P.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, J.; Zhang, G.T.; Ramzan, M. Occurrence of shallow landslides triggered by increased hydraulic conductivity due to tree roots. Landslides 2022, 19, 2593–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.S.; Liu, W.; Chen, W.Z. Collapse test studies on coarse grain sulfite saline soil as an embankment fill material. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.S.; Cai, D.G.; Yao, J.K.; Wei, S.W.; Yan, H.Y.; Chen, F. Review on dynamic modulus of coarse-grained soil filling for high-speed railway subgrade. Transp. Geotech. 2021, 27, 100421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zou, Q.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Cui, J.F.; Zhou, B.; Zhou, W.T.; Chen, S.Y.; Zeng, Z.H. Probability analysis of shallow landslides in varying vegetation zones with random soil grain-size distribution. Environ. Modell. Softw. 2025, 183, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krim, A.; Brahimi, A.; Bouri, D.E.; Nougar, B.; Lamouchi, B.; Arab, A. Effect of non-plastic fines content and gradation on the liquefaction response of chlef sand. Transp. Infrastruct. Geotechnol. 2024, 11, 2638–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ren, T.Z.; Zhang, R.; Gao, Q.F.; Zheng, J.L. Influence of gradation on resilient modulus of high plasticity soil-gravel mixture. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghistani, F.; Abuel-Naga, H. Evaluating the Influence of sand particle morphology on shear strength: A comparison of experimental and machine learning approaches. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.C.; Hino, T.; Qiao, Y.F.; Ding, W.Q. Progressive yielding/softening of soil-cement columns under embankment loading: A case study. Acta Geotech. 2024, 19, 7229–7241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppa, N. Stress-strain behaviour of fine grained soils with varying sand content. Asian Rev. Civ. Eng. 2014, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Q.; Zhao, F.; Cheng, S.Q.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Gou, M.J.; Jing, H.J.; Zhi, H.F. Study of sericite quartz schist coarse-grained soil by large-scale triaxial shear tests. Front. Phys. 2020, 8, 551232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleghnejad Tabari, M.; TaghaviGhalesari, A.; Janalizadeh Choobbasti, A.; Afzalirad, M. Large-scale experimental investigation of strength properties of composite clay. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2019, 37, 5061–5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.F.; Ai, Z.W.; Luo, S.H.; Gui, Y. Experimental study on shear characters of clay-sand mixture. People’s Yangtze River 2014, 45, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.F.; Wei, H.Z.; Meng, Q.S.; Wei, C.F.; Ai, D.H. Effects of shear rate on shear strength and deformation characteristics of coarse-grained soils in large-scale direct shear tests. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2013, 35, 728–733. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T50123-2019; Standard for Geotechnical Testing Method. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Bao, L.L.; Wei, F. Macroscopic and microscopic analysis of the effects of moisture content and dry density on the strength of loess. Sci. Prog. 2024, 107, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.R.; Liu, J.G.; Ding, Y.Q.; Kong, T.Q.; Zhang, G.K.; Zhang, N.; Li, G. Effects of moisture and compactness on uniaxial dynamic compression of sandy soil under high strain rates. Transp. Geotech. 2022, 34, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, Y.; Wei, X.L.; Zhou, H.B.; Chen, N.S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, F.; Sun, H. Snowmelt-triggered reactivation of a loess landslide in Yili, Xinjiang, China: Mode and mechanism. Landslides 2022, 19, 1843–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, C.M. Mechanistic analysis of splash erosion on loess by single raindrop impact: Interaction of soil compaction, water content, and raindrop energy. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 236, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.J.; Wu, X.L.; Xia, J.W.; Miller, G.A.; Cai, C.F.; Guo, Z.L.; Arash, H. The effect of water content on the shear strength characteristics of granitic soils in South China. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 187, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamandé, M.; Schjonning, P. Transmission of vertical stress in a real soil profile. Part III: Effect of soil water content. Soil Tillage Res. 2011, 114, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.J.; Ren, T.S.; Horn, R. Effective stress and shear strength parameters of unsaturated soils as affected by compaction and subsequent shearing. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2023, 74, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marani, S.M.; Shahgholi, G.; Szymanek, M.; Tanaś, W. Experimental evaluation of nano coating on the draft force of tillage implements and its prediction using an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS). AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 1218–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.X.; Li, H.B.Q.; Jiang, Y.H.; Tian, P.Z.; Cao, A.S.; Long, Y.X.; Liu, X.T.; Si, P.F. Slope monitoring optimization considering three-dimensional deformation and failure characteristics using the strength reduction method: A case study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Cui, D.S.; Chen, Q.; Yang, L.X.; Xiang, W. Bender element test and numerical simulation of sliding zone soil of Huangtupo landslide. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2021, 80, 8465–8480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fateh, A.M.A.; Goleij, M. The effect of maximum diameter of geogrid-reinforced sandy soil particles on shear strength parameters. Eng. Res. Express 2023, 5, 045086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigeot, L.; Dufour, N.; Calissano, H.; Dermenonville, F.; Soive, A. Influence of the curing stress effect on the stiffness degradation curve of a silt stabilized with lime and cement. Eng. Geol. 2024, 337, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Tang, M.G.; Xiao, X.X.; Cai, G.J.; Wei, Y.; Li, S.L.; Li, H.J.; Xie, J.W. Physical Model Test of Deformation Self-Adaptive Mechanism of Landslide Mass. Water 2024, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Q.R.; Liu, J.W.; Shang, W.C.; Garg, A.; Jia, X.R.; Sun, K.Y. Application of ann in construction: Comprehensive study on identifying optimal modifier and dosage for stabilizing marine clay of Qingdao coastal region of China. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.M.; Teng, J.D.; Wang, H.W. Influence mechanism of water content and compaction degree on shear strength of red clay with high liquid limit. Materials 2024, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, R.; Meng, Q.S. Study of soft soil triaxial shear creep test and model analysis. Rock Soil Mech. 2012, 33, 106–110. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.L.; Lu, Y.Q.; Lai, J.X.; Zhang, Y.W.; Yang, T.; Wang, K. Experimental study on the effect of water gushing on loess metro tunnel. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 79, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.X.; He, S.M.; Li, X.P.; Scaringi, G.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Y. Investigating the dynamic process of a rock avalanche through an MLS-MPM simulation incorporated with a nonlocal μ(I) rheology model. Landslides 2024, 21, 1483–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmonem, H.H.; Abo Bakr, M.; Saad Eldin, M. Influence of wate content on the shear strength parameters for cohesive soil. J. Al-Azhar Univ. Eng. Sect. 2023, 18, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, X.L.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, Y.L.; Han, B.B.; An, N.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Y. Stability of loess high-fill slope based on monitored soil moisture changes. Res. Cold Arid. Reg. 2023, 15, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.H.; Zhang, J.R.; Lu, F.; Fan, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z. Stability assessment of tunnels excavated in loess with the presence of groundwater-A case study. Water 2024, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbi, S.M.F.; Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B.; Young, L.M. Microbial processing of organic matter drives stability and pore geometry of soil aggregates. Geoderma 2020, 360, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.Q.; Zhong, M.; Wei, C.F.; Zhang, W.H.; Hu, F.N. Shear strength features of soils developed from purple clay rock and containing less than two-millimeter rock fragments. J. Mt. Sci. 2016, 13, 1464–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawidowski, J.; Koolen, A. Changes of soil water suction, conductivity and dry strength during deformation of wet undisturbed samples. Soil Tillage Res. 1987, 9, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhao, Q.G.; Horn, R.; Baumgartl, T. Shear strength of surface soil as affected by soil bulk density and soil water content. Soil Tillage Res. 2001, 59, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.N.; Liu, H.L.; Chen, Y.M. Test study on influence of fine particle content on dynamic pore water pressure development mode of silt. Rock Soil Mech. 2008, 29, 2193–2198. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, K.M. A large deformation finite element model for soil compaction. Geomech. Geoengin. 2012, 7, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, B.K.; Shawez, M.; Gupta, V.; Rawat, G. Ground subsidence in Dar village (Darma valley), Pithoragarh district, Kumaun Himalaya, India: A Himalayan disaster in waiting. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 133, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Deng, P.Y.; Yang, Z.B.; Wang, Y. Statistical analysis of physical and mechanical parameters of soil-rock mixture in China. Eng. Res. Express 2025, 7, 045103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).