1. Introduction

Thermal Energy Storage (TES) systems have become a cornerstone in advancing the efficiency and flexibility of microgrids, particularly when integrated with renewable energy sources. TES systems help balance supply and demand, reduce reliance on fossil fuels, and improve overall system performance by enabling the storage and strategic use of thermal energy. One of the recent advancements in this area is the ECHO-TES, a system developed within the framework of the European Union’s Horizon Europe initiative, aiming to enhance residential thermal energy management. However, it remains an emerging concept for utilizing TCMs and is not yet ready for real-world application [

1]. The ECHO-TES system provides compact and efficient solutions for heating, cooling, and hot water production [

2]. An innovative aspect of the ECHO approach is the creation of a small-scale TES solution designed specifically for individual households. Traditionally, TES systems—especially those based on TCM—have been more closely linked to large-scale applications. Furthermore, an essential feature of these future (micro) TES systems, including ECHO, is their potential to integrate seamlessly with the electrical grid [

3].

Accurate modeling and simulation of their operations are essential to fully harness the potential of TES systems within microgrids. Within the ECHO project, thermal performance analyses were carried out using the Energy Urban Resistance-Capacitance (EUReCA) method, a platform designed to model and predict energy consumption patterns in urban environments [

4]. While EUReCA simulations focus on long-term modeling and forecasting, the present study investigates the integration of the ECHO TES system into microgrids to address technical constraints using simulation tools such as OpenDSS.

OpenDSS, created as an open-source platform by EPRI, is widely employed for modeling distribution networks that integrate thermal energy storage and renewable generation, offering flexible simulation capabilities for microgrid studies. Its ability to model dynamic behaviors and evaluate various operational scenarios makes it an interesting and valuable tool for microgrid research and development. For instance, studies using OpenDSS, Version 10.1.0.1 (64-bit build)—Columbus, EPRI, 3420 Hillview Avenue, Palo Alto, CA, USA have demonstrated its effectiveness in improving distribution network efficiency through optimized configurations, where efficiency was observed when operating as a microgrid [

5]. Additionally, OpenDSS has been used for co-simulation studies that explore hybrid setups involving distributed generation, battery storage systems, and TES units to assess their combined impact on grid performance under diverse conditions [

6].

Deploying TES systems like ECHO within microgrids requires advanced demand-side management strategies to ensure optimal operation. These strategies involve balancing thermal needs—such as heating and cooling—with electricity demand while maintaining grid stability [

7]. Platforms like OpenDSS enable the implementation of sophisticated control algorithms that optimize TES unit performance, reduce peak loads, and enhance overall system reliability. For example, virtual energy storage models have been proposed to manage thermal loads efficiently by adjusting indoor temperatures in building microgrids while maintaining user comfort. These approaches improve operational flexibility and reduce costs associated with energy storage and distribution [

8]. When coupled with combined cooling, heating, and power (CCHP) systems, TES can serve as a virtual storage unit, enhancing the operational management of interconnected energy networks [

9].

Integrating TES into microgrids also raises important questions about system reliability and resilience. As renewable energy sources like solar and wind introduce variability into power generation, ensuring a consistent energy supply becomes a critical challenge [

10]. Research leveraging OpenDSS has provided valuable insights into how TES can mitigate these challenges by stabilizing fluctuations in supply and demand. Research using co-simulation approaches indicates that integrating TES within microgrids improves their resilience against fluctuations in demand and renewable energy output, helping to sustain steady performance under variable conditions [

11]. These findings highlight the importance of simulation tools in designing robust microgrid systems capable of adapting to evolving energy demands.

This paper focuses on assessing the impact of integrating the ECHO micro-thermal energy storage system to solve technical constraints in microgrids, using simulation tools such as OpenDSS and Python. Various thermal demand scenarios and their effects on grid stability and management will be analyzed to identify strategies to facilitate the transition to a more sustainable and resilient energy system.

The article is organized into several sections, starting with

Section 2, which addresses the state of the art related to the research topic, providing an overview of previous knowledge and advancements in the field of study.

Section 3 presents the methodology used in the research, detailing the approaches, tools, and procedures applied to conduct the study.

Section 4 presents the case study under investigation and the practical application of the method described in

Section 3. Next,

Section 5 showcases the results of applying this methodology to the case study, providing relevant analysis. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the study’s key findings and outlines potential future research directions that could expand or deepen the conducted research.

2. Literature Review

Managing technical constraints in microgrids through TES, modeled using OpenDSS, constitutes an innovative approach for improving the performance and flexibility of modern energy systems. This line of research brings together recent developments in long-duration energy storage (LDES), advanced modeling environments, and integrated microgrid control strategies. Furthermore, evaluating residential energy flexibility has proven essential for enhancing demand-side management, particularly in local contexts such as municipal distribution networks [

12].

Microgrids are composed of interconnected energy units that can function independently or in coordination with the primary power grid [

13]. These grids include various generation sources, such as photovoltaic systems, wind turbines, and conventional generation units, as well as both electrical and thermal energy storage systems [

14]. Including thermal energy storage within microgrids facilitates more efficient utilization of renewable resources while decreasing reliance on fossil-fuel generation, resulting in lower operating costs and a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions [

15]. However, there are significant technical challenges in implementing these solutions, such as managing the intermittency of renewable sources, optimizing thermal load relative to electricity demand, and coordinating effectively with other system elements [

16]. Microgrids have emerged as important components in the transition towards low-carbon energy systems, integrating DERs and ESS to optimize energy distribution and consumption. Managing these complex systems requires sophisticated approaches to address technical constraints such as load balancing, voltage regulation, and frequency control.

Recent research has focused on developing optimization techniques ranging from classical methods to artificial intelligence-driven algorithms, aiming to reduce operational costs and enhance system reliability in both grid-tied and islanded configurations [

17], demonstrated the effectiveness of a rule-based battery control strategy combined with deep-learning load forecasting for peak shaving in Swiss distribution networks, achieving a reduction in peak demand costs through real-time energy storage management. For microgrid economic dispatch [

18], an initialization-free distributed algorithm was proposed that reduces computational complexity and minimizes the total generation cost in a dynamic dispatch problem. In solar-powered systems [

19], a two-stage optimization framework was developed, integrating shared energy storage. This decoupled approach allows testing and comparing different methods for the EMS on one side and for the energy sharing on the other, for a total of forty different investigated combinations. In addition, the work [

20] presented the techno-economic benefits of increasing PV self-consumption using shared energy storage for a prosumer community under various penetration rates. The research [

21] presented a collaborative voltage optimization method that leverages the flexibility of community heating systems to reduce daily voltage deviations in high PV penetration scenarios. Finally, the study [

22] proposed a week-ahead dispatch model using hybrid energy storage systems, reducing weekly operational costs compared to conventional battery-only systems.

TES systems are pivotal in this landscape, offering cost-effective, environmentally friendly solutions for long-duration energy storage. These systems, which include sensible heat storage (e.g., water tanks), latent heat storage (e.g., phase change materials), and thermochemical storage, can efficiently store energy for extended periods, making them ideal for diverse applications in heating, cooling, and industrial processes [

23]. The integration of TES with CHP units in microgrids has shown particular promise, enhancing flexibility and efficiency while reducing wind curtailment and optimizing heat and electricity production.

One of the main challenges in managing microgrids with thermal storage is optimizing energy conversion and distribution. In this regard, OpenDSS has positioned itself as a fundamental tool for analyzing and modeling distribution networks [

24]. OpenDSS, developed by EPRI, serves as a simulation platform that enables comprehensive modeling and analysis of electrical distribution networks, facilitating the study of the behavior of microgrids under different operating conditions. Thanks to its time-domain analysis capabilities and the possibility of modeling energy storage elements, OpenDSS allows evaluation of the effects of thermal storage integration on microgrid operation, identifying possible technical constraints, and designing appropriate mitigation strategies [

25]. Research employing OpenDSS simulations has shown considerable gains in efficiency for distribution networks functioning in microgrid mode, with one case study showing a 51.5% improvement in the IEEE 13-node test feeder [

26].

Integrating Long Duration Energy Storage (LDES) technologies provides additional capabilities for addressing technical limitations in microgrid operations. These technologies are particularly suited for applications requiring power over extended periods when renewable sources are not producing [

27]. For instance, iron-flow batteries have been integrated into tactical microgrids for military applications, providing up to 12 h of flexible energy capacity, reducing diesel consumption by up to 40%, and increasing generator efficiency. These advancements are particularly valuable for remote installations or contingency bases where reliable power is essential, facilitating the transition from diesel generators to renewable energy sources.

Addressing the challenges of load variability, renewable intermittency, and thermal balance requires sophisticated optimization models. Stochastic optimization methods incorporating chance constraints have been developed to handle uncertainties in load demand and renewable generation [

28]. Moreover, advanced models now integrate electrical and thermal dynamics to ensure optimal operation of hybrid systems like CHP-TES configurations, enhancing overall system efficiency and resilience. Integrating these various elements-advanced microgrid energy management strategies, TES systems, sophisticated modeling tools like OpenDSS, and long-duration energy storage technologies—creates a comprehensive framework for evaluating and optimizing technical constraint management in microgrids [

29]. This holistic approach addresses current challenges in energy distribution and consumption and paves the way for more resilient, sustainable energy systems capable of adapting to future demands and environmental constraints. While existing literature has explored the integration of TES systems and optimization models in microgrids, most studies focus on large-scale or generic implementations without fully addressing the operational flexibility required at the distribution level. In contrast, the ECHO device represents a novel contribution by offering a compact, home-scale TES solution designed to enhance grid flexibility. By enabling precise thermal load management and facilitating sector coupling between electricity and heat, ECHO addresses a critical gap identified in current research. Its integration into distribution networks supports mitigating technical constraints such as peak load stress and voltage fluctuations and aligns with decarbonization goals through efficient, demand-responsive operation.

Recent developments in microgrid energy management have focused on enhancing system flexibility and reliability. Indeed, researchers have explored the use of multi-energy systems within microgrids, leveraging redundancy in power electronics to improve overall system performance and contributing to the ability of microgrids to maintain stable operation under various conditions, including sudden changes in renewable energy generation or load demand [

30]. On the other side, some studies have explored the optimization of microgrid operation by implementing mathematical programming models and artificial intelligence techniques [

31]. These methodologies allow the development of advanced control strategies that optimize the use of available energy resources and minimize the impact of technical constraints [

32]. In particular, combining OpenDSS with optimization tools, such as genetic algorithms or dynamic programming, has shown promising results in improving system stability and reducing energy losses [

33]. In summary, it can be concluded that, while many studies address microgrid optimization and some of them consider thermal storage, there is a lack of research on the accurate impact that distributed thermal storage may have on the power grid when it is used to solve operational problems that may appear in the network, which is addressed in this paper.

The role of TES in microgrids has gained significant attention due to its potential to enhance system efficiency and reduce reliance on fossil fuels. TES systems can store virtual energy when combined with CCHP units or other renewable sources [

34]. This integration allows for better heat and electricity production management, potentially reducing wind curtailment in CHP-based microgrids and improving overall energy utilization [

35]. Researchers have used OpenDSS to evaluate the impact of different energy management strategies on microgrid performance, considering factors such as voltage regulation, power quality, and system losses [

36].

Incorporating LDES technologies in microgrids has opened new possibilities for enhancing system resilience and reliability. LDES systems can provide power for extended periods, making them particularly valuable in scenarios where renewable energy sources may be intermittent or unavailable [

37]. According to the LDES Council, these storage technologies play a pivotal role in facilitating the integration of renewable energy into power grids and advancing carbon reduction objectives.

Effectively tackling technical challenges in microgrids demands a comprehensive strategy incorporating electrical and thermal system dynamics. Recent studies have focused on developing optimization models incorporating flexibility constraints to handle uncertainties in renewable generation and load [

38]. These models aim to enhance the reliability and resiliency of microgrid operations while minimizing operational costs.

The integration of thermal storage applications in microgrids [

39] presents both opportunities and challenges. On the one hand, thermal storage can provide a cost-effective energy storage means and help balance the intermittency of renewable sources. On the other hand, careful management is required to ensure optimal operation and avoid issues such as thermal losses or inefficient heat distribution. Multiple approaches have been investigated to optimize the functioning of thermal energy storage systems in microgrid environments, including predictive control algorithms and multi-objective optimization techniques [

40].

As the field of microgrid energy management continues to evolve, new research areas are emerging. These include the development of advanced control strategies for coordinating multiple energy storage technologies, integrating demand response programs to enhance system flexibility, and exploring novel thermal storage materials and configurations to improve efficiency and storage capacity.

An essential contribution of this work lies in incorporating an analysis of the flexibility required in the electricity distribution network to face complex future scenarios. This analysis introduces the strategic role of ECHO thermal energy storage technologies as an innovative and efficient solution to offer the flexibility demanded by Distribution System Operators (DSOs) to solve the technical constraints in the distribution network. The ECHO device is an advanced TES system developed under the ECHO project. This project aims to develop a home-sized storage solution for heating and cooling. Efficiently storing and regulating thermal energy distribution enhances grid reliability and promotes a more balanced and sustainable energy supply. This capability not only improves the operational stability of the electricity system but also contributes to the more efficient use of available energy resources, aligning with global sustainability goals.

In addition, this approach includes assessing how climate change will influence heating and cooling needs and the flexibility of a distribution network. This analysis makes it possible to anticipate the necessary adaptations in the energy infrastructure to ensure its resilience to changing conditions. In this sense, the model addresses current challenges and provides a strategic tool to plan and optimize the operation of electricity systems in the face of the challenges of an uncertain future. Furthermore, this model considers the sector coupling between the thermal and electricity sectors, which is becoming increasingly relevant in decarbonization. The thermal sector, often characterized by its higher volatility than traditional electrical uses, presents a complex challenge when integrated with the electricity grid. This volatility arises from the varying demand for heating and cooling, which can be heavily influenced by seasonal, geographical, and climatic conditions. The electrification of the HC sector introduces new dynamics in this context, with the transition from fossil fuel-based systems to electric solutions like heat pumps. While this shift offers significant benefits for reducing carbon emissions, it also poses grid stability and efficiency challenges. Electrification can increase electricity demand, particularly during peak times when heating and cooling needs are highest. Therefore, understanding the interplay between these sectors is essential for designing an integrated and resilient energy system. The optimal management of this coupling can help balance supply and demand more effectively, reduce emissions, and make the overall energy system more adaptable to both climatic changes and the ongoing transition to a low-carbon economy.

3. Methodology

The methodology employed in this research, represented in

Figure 1, consists of nine interconnected phases that enable a detailed and systematic analysis of the system under study, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the obtained results. First, the simulation environment is established, defining the tools and parameters necessary to realistically model the system. Then, the implementation of data and the configuration of the electrical model in OpenDSS is carried out, ensuring a precise representation of the energy infrastructure.

Subsequently, a validation process is performed by comparing the simulation results with real data, allowing the verification of the model’s fidelity and the adjustment of parameters as needed. Once the model is validated, the definition of different study scenarios takes place, considering key factors such as variations in demand and temperature, the integration of renewable energy sources, and extreme operating conditions. These scenarios are simulated in the fifth phase to evaluate system behavior under different conditions and identify potential operational issues.

In the sixth stage, technical constraints that could affect the microgrid’s performance are identified, such as overloads, voltage fluctuations, or inefficiencies in energy distribution. Based on this analysis, in the seventh phase, management strategies are designed and implemented to mitigate the detected limitations, improving the system’s stability and efficiency. Finally, a comprehensive analysis of the obtained results is conducted, focusing on quantifying the ECHO devices needed to address demand fluctuations and potential supply issues. This process allows for optimizing the sizing of energy resources and ensuring a more efficient and sustainable planning of the electrical system, guaranteeing its operability and compliance with technical and regulatory standards.

3.1. Step 1: Definition of the Simulation Environment

This step constitutes the first phase of the methodology, where the simulation environment and tools are established. In this study, OpenDSS has been selected as the main software due to its capability to model and analyze electrical distribution systems in detail. Additionally, programming languages such as Python 3.12 (64-bit), Python Software Foundation, 9450 SW Gemini Dr. ECM# 90772, Beaverton, OR, USA have been used to facilitate the automation of simulations and the processing of results.

The microgrid under study is defined, specifying its main characteristics, such as system topology, voltage levels, distributed generation elements, thermal storage system, and load distribution. The simulation developed in OpenDSS is based on a technical environment that represents a balanced three-phase distribution network operating at a base frequency of 50 Hz. Conventional electrical models are adopted for the main system components, such as lines, transformers, and switching devices, which are considered to exhibit linear behavior without the inclusion of nonlinear effects or imbalances. Additionally, a hierarchical voltage level structure is defined, allowing electrical quantities to be properly normalized during the simulation. The network also incorporates location data through coordinates assigned to the nodes, enabling a coherent spatial representation.

3.2. Step 2: Power System Modeling and Data Integration in OpenDSS

The second stage of this step consists of implementing the electrical model of the distribution network in OpenDSS. In this stage, the essential elements of the network, such as power lines, TSs buses, loads, and production curves, are incorporated using network data provided by the DSO, public data (such as temperature profiles and typical power line parameters). Once the model is completed, the consumption and demand data obtained in previous phases are integrated to analyze how the grid responds under different configurations and loads. The objective of this step is to identify the data required for the modeling of an electric distribution network, the electrical parameters of the electrical distribution lines and transformers, and to analyze and select the power system solver algorithm.

The first stage of this step consists of modeling of the elements of the grid using a nodal admittance approach [

41]. Therefore, power lines and transformers are modeled according to the concentrated parameters “pi” approach, where each element is considered as an electric circuit with a series branch, with

Rs and

Xs connected in series, and two shunt branches at the beginning and the end of this circuit, including the

Bp of the line.

In this model, depicted in

Figure 2,

Rs and

Xs are used to build the series complex impedance of the line or transformer:

Conversely,

Bp is used to calculate the shunt admittance of the line or transformer, which is divided into two as the model considers that half of the capacitive effect is concentrated at the beginning of the line, while the other half takes place at the end of the line. Notice that the shunt conductance has been neglected.

The values to feed this model are obtained from the Input data. However, the resistance

Rs may be affected by the temperature at which the grid is. Indeed, the value of resistance provided by the distribution company is at a standard temperature of 20 °C. In case the external temperature is different, the model considers the actual temperature for the simulated hour according to the following expression:

Once the parameters for each element (power line or transformer) have been updated, the mathematical model of the whole grid is obtained throughout by the nodal admittance matrix formulation. This is a square and symmetric matrix of dimensions NxN, N being the number of buses of the system. The number of buses, N, equals the total count of bus nodes in the modeled grid minus one (assuming the reference bus is excluded).

The architecture of the admittance matrix is represented next:

According to

Figure 2, the shunt branch is already calculated as an admittance. However, the series branch represents an impedance, and it must be turned into an admittance, as shown next:

Each element of the admittance matrix will have Gik and Bik. Therefore, this matrix can be represented as follows:

The shunt branch is already calculated as an admittance. However, the series branch

The admittance matrix represents the mathematical model of the system, and it remains constant for all the simulations of a specific scenario.

Regarding the simulation in OpenDSS, a power calculation model based on the Gauss-Seidel method is used in which the value of the complex voltage (module and phase) and the complex power balance (real and reactive) in each bar of the electricity system considered is determined. Once these four variables have been obtained, the working points of the system can be determined. Two of these variables are known depending on the type of bus (reference bus, voltage-controlled bus (PV), load bus (PQ)), so a power flow calculation must determine the remaining two variables per bus.

The following equations can determine the real and reactive power in buses where these magnitudes are unknown:

As can be seen, the solution of the system of equations is not evident since the power balance on a bus depends on the voltage of all the other buses in the system (and the same goes for voltages). Therefore, an iterative process must be applied to determine the solution of different unknowns. In power system analysis, there are two basic methods to address this problem: Newton-Raphson and Gauss-Seidel (the so-called “normal” current injection mode in OpenDSS). Gauss-Seidel is faster and relatively more straightforward. Newton-Raphson is more robust for systems that are difficult to solve but have the complexity of working with large matrices, which must be inverted. Therefore, the iterative Gauss-Seidel method was used in OpenDSS to solve the power flow due to its simplicity and efficiency in distribution networks, which are typically radial or weakly meshed. This method is particularly suitable for systems with sparse and diagonally dominant admittance matrices, common characteristics in medium- and low-voltage networks. Additionally, Gauss-Seidel offers fast convergence and low computational cost per iteration, making it ideal for performing multiple simulations across different scenarios or time profiles.

The expression used to calculate the complex voltage according to Gauss-Seidel is as follows:

Equation (9) is observed to be a vector expression, which provides a complex number composed of two components. Therefore, the variables to be entered are also complex numbers. On the contrary, the equations to calculate the real and reactive power values (Equations (7) and (8)) are scalar expressions where the variables to be entered are real numbers.

After determining the complex voltage for all buses, all line powers are calculated according to the following expressions:

It should be noted that Equations (10) and (11) are calculated with the serial and derivation admittances of the line, while Equations (7) and (8) are obtained from the elements of the admittance matrix.

3.3. Step 3: Model Validation

Model validation is critical to ensure the accuracy of simulated results. This process includes running steady-state power flow simulations and comparing the powers P and Q calculated on the reference busbar with actual values recorded by the DSO. In distribution networks, the reference busbar typically corresponds to the substation that connects the local grid to the main grid. Additionally, if available, the simulated stresses on other busbars are compared to actual measurements. When significant discrepancies are identified, adjustments are made to model parameters, such as line impedances and transformer configurations, to minimize error between the measured and simulated variables. This iterative process ensures that the model is accurate enough for subsequent stages of simulation and analysis. This process can be broken down into the following steps:

Preliminary validation of the values obtained for loads and voltages on the buses: in the base case, the voltage values must be close to the nominal value for each bus (approximately one per unit). The voltage phase must be small (in any case, less than the 30° stability limit). Finally, the power balance throughout the system must be balanced (the net power injected into the system must be slightly higher but approximately equal to the power extracted from the system since power losses are low).

Comparison of the values obtained with actual data obtained from measurements: It would be useful to compare the voltages of all buses and the power along the power lines when available. This information is sometimes missing; therefore, a comparison should be made between the power exchange values on the reference bus.

If the deviations between measurements and simulations are large (more than 15%), reviewing the parameters entered in the model for power lines and transformers is necessary. In this case, the check is performed using the standard values provided. If the values of some parameters are very different from those considered, they are replaced by standard values, and new simulations are performed to validate this action.

3.4. Step 4: Definition of the Scenarios

At this stage, multiple scenarios are designed (details of scenarios are provided in

Section 4.4) to evaluate the impact of the ECHO-TSS thermal storage system on the grid under different operating conditions and penetration levels. The scenarios are developed considering strategies related to the flexibility of the system, such as the absorption of energy surpluses during periods of high renewable generation (mainly photovoltaics and wind power), the increment in the energy consumption during low prices periods and load shift strategies to solve technical constraints in the grid. In addition, specific scenarios are proposed to evaluate the performance of the ECHO-TSS system in terms of flexibility and its contribution to network modernization.

3.5. Step 5: Simulation of Scenarios

After defining the scenarios and calibrating the model, detailed simulations are carried out to assess the impact of the ECHO-TSS system on the distribution network. These simulations allow for the analysis of how the storage capacity of grid users can be used for flexibility services, such as handling peak demand or efficiently integrating renewable resources. In addition, the maximum capacity of the network to support the installation of ECHO-TSS systems is evaluated using reliability analyses that consider technical criteria (such as network stability).

3.6. Step 6: Identification of Technical Constraints

After modeling the microgrid, a detailed analysis of the technical constraints that could affect its operation is conducted using load flow simulations in OpenDSS. These simulations allow for evaluating the system’s behavior under different operating conditions, identifying potential issues, and proposing solutions. Among the main constraints analyzed are overvoltage and voltage drops, ensuring that voltage levels at the nodes remain within the limits established by European and Spanish regulations. The Spanish Royal Decree 1955/2000 and the European standard UNE-EN 50160:2020 [

42] regulate the voltage limits and quality parameters that distribution companies must maintain. These regulations ensure that voltage levels remain within acceptable margins to guarantee reliable service and protect electrical equipment.

Another fundamental aspect is quantifying energy losses within the microgrid to identify opportunities for improving operational efficiency. Additionally, operational stability is analyzed, considering the impact of intermittent renewable generation, temperature variations, and energy demand fluctuations—factors that can influence the overall performance of the microgrid. Constraints are evaluated by comparing the simulation results with the reference values defined in the regulations, thus ensuring optimal system design and operation.

3.7. Step 7: Strategy Definition

In Step 7, real operational strategies are defined to mitigate the technical constraints identified in the distribution network through the use of the ECHO-TES thermal energy storage system. These strategies are based on a detailed characterization of ECHO-TES performance, including its storage capacity, efficiency, response times, and operational limitations. Based on this information, specific activation criteria are established—such as the occurrence of overloads, voltage drops, or high peak demand periods—and actions are taken, such as shifting thermal loads to off-peak hours, modulating consumption according to network conditions, or coordinating with other distributed energy resources. The strategies are implemented either locally or centrally, depending on the system architecture, and aim to optimize network operation by reducing critical events and improving voltage and load profiles, ensuring a more flexible, secure, and efficient operation.

3.8. Step 8: Implementation of Constraint Management Strategies

Based on the identification of technical constraints in the microgrid, various strategies are designed and proposed to mitigate detected issues, improving system stability, efficiency, and reliability. One fundamental solution is the implementation of ECHO-TSS, which enables more efficient energy demand management by shifting electrical loads to periods of lower consumption. This approach helps reduce stress on the electrical infrastructure during peak demand periods, optimizing resource utilization and decreasing operational constraints.

In addition to thermal storage, complementary strategies are considered to enhance the overall performance of the microgrid. One such strategy is energy dispatch optimization, which dynamically adjusts distributed generation and thermal load to minimize technical constraints and maximize energy resource utilization. This entails analyzing different operational scenarios and developing strategies to balance generation and consumption efficiently. Moreover, voltage and reactive power control is essential to ensure compliance with voltage level limits set by European regulations. For this purpose, voltage regulators and capacitor banks allow a stable voltage profile throughout the microgrid. This strategy is particularly important in systems with high penetration of renewable generation, where generation variability can cause voltage fluctuations that need to be efficiently compensated. Each of these strategies is implemented in the OpenDSS simulation software, allowing for the evaluation of their effectiveness in mitigating technical constraints. Various operational scenarios are analyzed through these simulations, and the results obtained are compared with reference values established in European regulations. In this way, the proposed solutions enhance the microgrid’s stability, security, and efficiency, optimizing its performance according to operational needs and regulatory requirements.

3.9. Step 9: Analysis of Results

The final analysis focuses on interpreting the results of the simulations for each of the defined scenarios. This includes evaluating the performance of the ECHO-TSS system, the impact of flexibility strategies on the network, and identifying potential limitations or areas for improvement. The results are compared with the objectives set to validate the proposed solutions’ effectiveness and provide valuable information that can be used in decision-making for the planning and modernization of the distribution network. This stage is very important in concluding the methodological process, ensuring that the solutions evaluated are viable, sustainable, and beneficial for the different actors in the energy system.

4. Case Study: Crevillente Electricity Distribution Network

The case study corresponds to the distribution network of the municipality of Crevillente, located in Spain, owned by the company Cooperativa Eléctrica San Francisco de Asís, belonging to the ENERCOOP Group. This company operates and maintains the MV and LV distribution network of the municipality of Crevillente, including a 40 MVA substation, which connects ENERCOOP’s infrastructures with the upstream network, owned by “i-de Redes Inteligentes” (Iberdrola Group) at a voltage of 132 kV.

4.1. Network Description

The Crevillente distribution network starts from the border point in the aforementioned substation, which transforms the voltage level from 132 kV to 20 kV. This is performed by a 40 MVA transformer. This substation is considered the slack bar to evaluate the power flow using the implemented network model. Downstream are four main handling stations, which feed more than 150 transformer stations of Crevillente’s distribution network. Each of these TS steps down the voltage from 20 kV to 400 V to supply electricity to end consumers. The TS are located in the urban area of the town, as well as in industrial estates and rural areas closer to the end consumers. The network comprises almost 25,000 buses, which are interconnected with each other and with the CTs by more than 25,000 power distribution lines. In fact, there are more than 400 km of aerial and underground power lines.

Based on this architecture, the network model has been particularized for this case, characterizing and parameterizing all the elements according to the information provided by the DSO. In addition, the aggregated hourly load and generation profiles of each TS have been introduced into the model.

4.2. Correlation Between Outdoor Temperatures and Actual Electricity Consumption

As shown in

Figure 3, the relationship between measured electricity consumption and outdoor temperature conditions is complex, depends on many intrinsic and extrinsic factors and is not necessarily proportional to the difference in outdoor temperatures and comfort temperatures. Aggregated consumption data were provided by the DSO (Enercoop), representing actual measurements for the TSs considered for this study. This relationship cannot be deduced directly from standard demand profiles but reflects the combined effects of electrification of thermal generation, efficiency of generation equipment, specific building usage patterns, and substitution of alternative fuels (in particular, gas for heating). In particular, at lower temperatures, gas heating reduces the proportion of electric load.

Figure 3 is significant because it highlights two critical issues: the close relationship between thermal and electrical demand and the need to use data-driven models to accurately capture that interaction.

- 1.

First, there is considerable sensitivity of electricity consumption to increases in neutral temperature. Thus, differences of +14 °C mean an overconsumption of 54% in the case of TS158 and 110% in the case of TS32.

- 2.

Second, electricity consumption in heating-dominated climatic conditions is much less sensitive to outside temperatures than the corresponding consumption in cooling-dominated conditions. This fact is related to a substitute fuel, such as fossil gas, with a strong penetration in Crevillente and much of Spain and southern Europe.

Following this perspective, the following section analyzes the factors that influence this reality, such as the prevalence of different technologies and sources of heating and cooling in a town such as Crevillente. It should be noted that it has not been possible to obtain information directly from the homes analyzed, so bibliographic and statistical sources have been resorted to, which, as will be demonstrated, are scarce and not very up-to-date [

43].

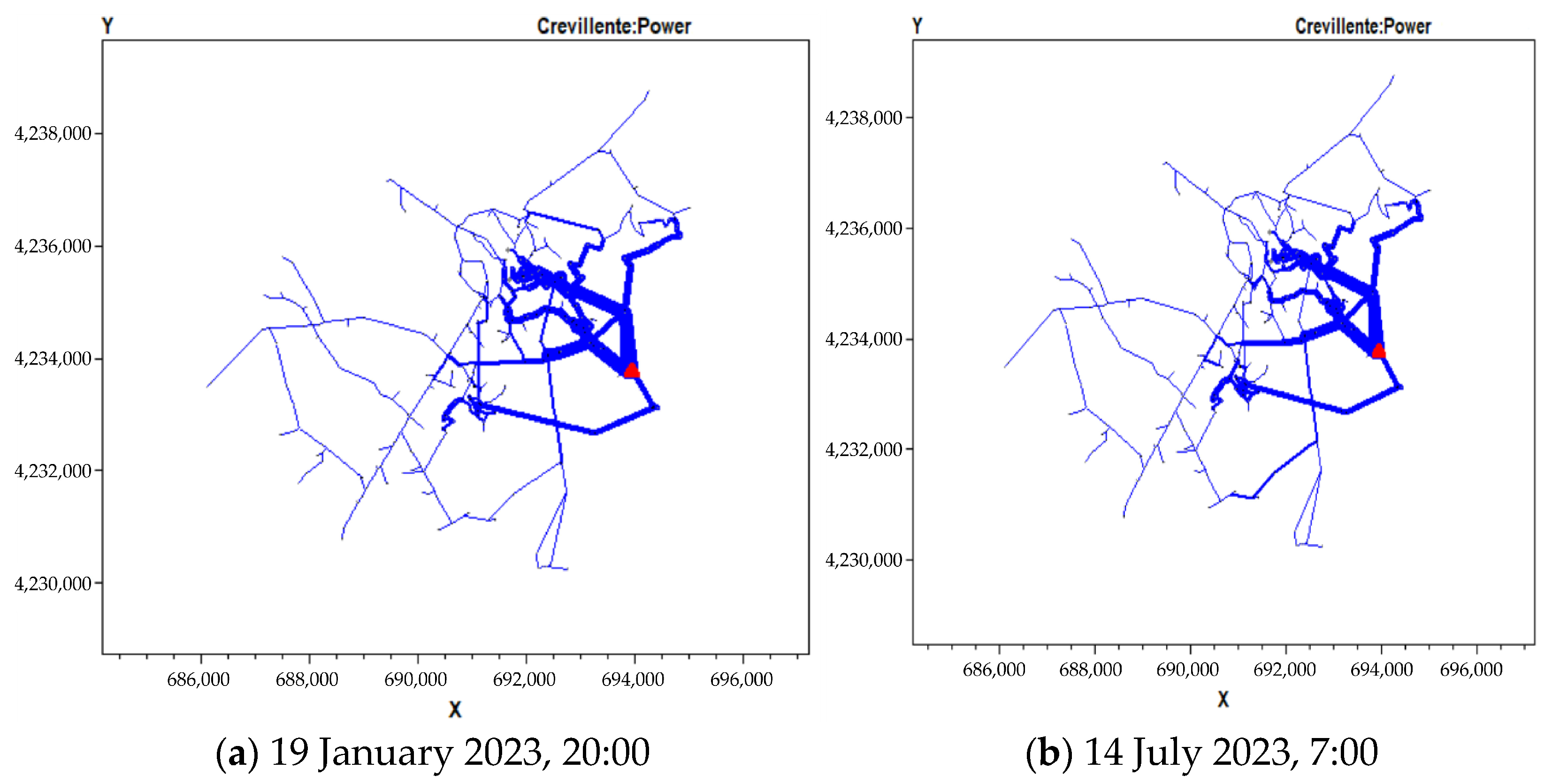

4.3. Description of the Base Case

The base case refers to two specific days (19 January 2023 and 14 July 2023). These two days have been chosen because the winter and summer profiles have been studied, and these days are the most representative and have the highest electricity consumption due to thermal needs. Therefore, the simulation these days was considered the extreme case that could occur in winter (the first date) and summer (the second). In particular, the maximum heating consumption during 2023 was obtained on 19 January at 8:00 p.m., while the equivalent cooling consumption was obtained on 14 July at 7:00 a.m. as shown in

Figure 4, which depicts the load profiles on both days for the base case, considering all the TSs for this study.

Due to the particular characteristics of this specific network, most consumers are residential, but there are also some industrial and commercial consumers, as well as offices and utilities.

4.4. Setting Up Scenarios

The scenarios developed in this study are designed to evaluate the impact of increasing electricity demand on microgrid operation and the management of the ECHO-TSS TES system under realistic yet progressively challenging conditions. The formulation of these scenarios is based on quantitative projections of electricity consumption, historical demand patterns, and sectoral trends in electrification, ensuring that the analysis reflects plausible near- and mid-term developments in residential, commercial, and transport sectors:

Scenario 1: this scenario represents the simulation of the actual electricity demand observed on the selected days, serving as a reference for all subsequent sensitivity analyses. The loads correspond to measured historical consumption profiles of the microgrid, as well as the operational characteristics of the distribution network under typical conditions. By using real data, this scenario provides a baseline for evaluating the microgrid’s normal operation, including voltage profiles, line and transformer loading, and overall power flow dynamics, under conditions that reflect actual consumer behavior and seasonal variations.

Scenario 2: reflects a moderate growth in electricity demand due to increased adoption of electric vehicles (EVs), average population growth, and rising electricity consumption for HVAC and household appliances. This scenario incorporates trends associated with remote work, which increases daytime residential electricity usage. The 50% demand increase is based on projections from regional energy studies and national statistical data [

44], representing a realistic intermediate growth trajectory for urbanized microgrids.

Scenario 3: 75% captures a higher growth trajectory, including widespread electrification of heating and transport, high adoption rates of EVs, moderate commercial sector expansion, and more frequent extreme weather events that increase HVAC loads. The percentage increase is aligned with forecasts from energy agencies [

45], integrated climate projections, and urban expansion scenarios.

Scenario 4: represents an extreme yet realistic scenario characterized by full electrification of residential, transport, and industrial sectors [

46], rapid urban growth, high industrial and commercial demand, and the maximum expected contribution of HVAC systems during peak periods. This scenario functions as a stress test to evaluate the robustness, operational flexibility, and coordination efficiency under conditions of maximal electricity demand, providing insights into microgrid performance limits and resilience under extreme operational conditions.

The criteria for defining these scenarios are grounded in three main pillars:

Historical demand analysis: Typical and peak daily load profiles were identified from historical consumption data, focusing on heating-dominated winter days and cooling-dominated summer days.

Sectoral and technological trends: Growth rates in electricity consumption due to electrification of transport, residential heating/cooling, and appliance usage.

Sensitivity and stress testing: Incremental load increases (50%, 75%, 100%) were chosen to systematically evaluate the microgrid performance under progressively challenging conditions, allowing a robust sensitivity analysis that identifies operational limits and response capabilities.

The selected days for simulation 19 January 2023 for winter peak and 14 July 2023 for summer peak were chosen because they correspond to historical peak demand periods for heating and cooling, respectively. All loads were modeled with a power factor of 0.9, reflecting historical averages and ensuring a realistic representation of the effects of reactive power on voltage and line loading. The scenarios were implemented in OpenDSS using incremental scaling of load profiles, maintaining consistency across all buses and ensuring that TES operation and dispatch could be analyzed in response to varying levels of demand.

6. Conclusions

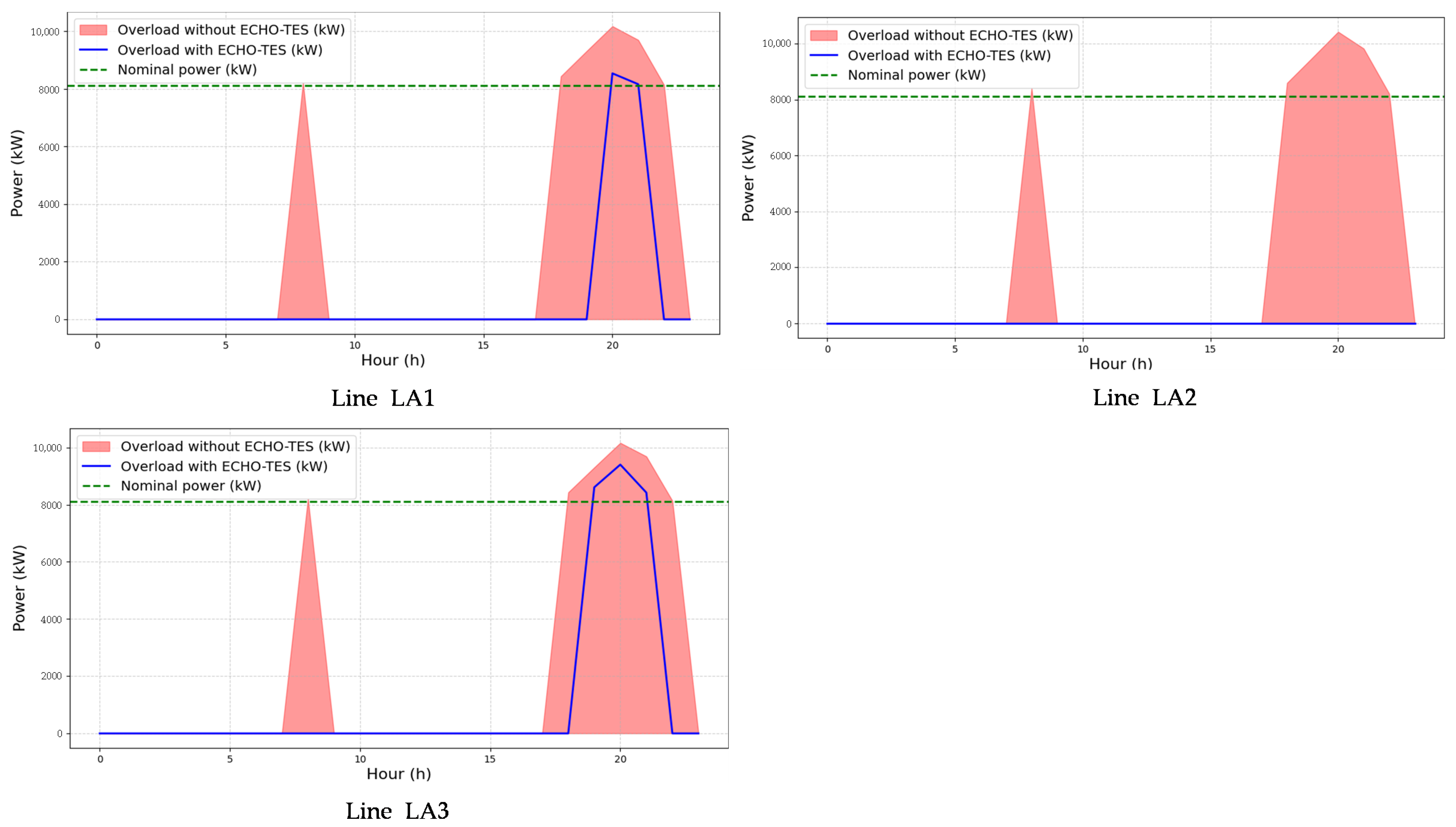

This study established a comprehensive theoretical and methodological framework to evaluate the integration of the ECHO-TSS system within a distribution-level microgrid, incorporating smart control strategies aimed at optimizing renewable energy utilization and enhancing network flexibility. The modeling approach, combining OpenDSS simulations with Python-based automation, enabled a detailed assessment of the technical constraints associated with increasing thermal and electrical demand, as well as the potential of ECHO-TES units to mitigate these constraints under diverse operating conditions. The modeling and scenario analysis demonstrated pronounced differences in the behavior of thermal demand: cooling consumption showed strong sensitivity to variations in outdoor temperature, while heating loads exhibited a more stable but seasonally concentrated pattern. These characteristics have direct implications for grid operation, as they shape the magnitude and timing of peak electricity demand and, consequently, the network’s exposure to voltage deviations and line loading constraints. The simulation platform developed in this work accurately replicated the electrical behavior of the microgrid across the four demand growth scenarios, capturing the progressive deterioration of voltage profiles, the increase in active and reactive power losses, and the emergence of line overloads under high and extreme load conditions. This validated framework provided a reliable basis for evaluating the effectiveness of thermal storage as a grid-supporting resource.

A key contribution of the study lies in quantifying the technical benefits of integrating ECHO-TES units. The results demonstrated that, even under extreme scenarios where electrical demand was doubled, the deployment of ECHO-TES in the most critical zones of the network significantly mitigated operational stress. The storage units effectively reduced peak active power demand, decreased both active and reactive power losses, and improved voltage conditions across the network. Importantly, the TES integration did not adversely affect system frequency or reactive power exchange. These findings highlight the potential of thermal storage as a non-electrical flexibility mechanism capable of relieving congestion, supporting voltage regulation, and postponing infrastructure reinforcement. The research also confirmed that ECHO-TES enhances demand management by enabling the temporal redistribution of thermal loads, thereby reducing pressure on the distribution grid during peak periods. This capability is particularly relevant in the context of increasing electrification of heating and cooling, where traditional grid assets alone may be insufficient to maintain operational margins. By alleviating technical constraints, ECHO-TES contributes to a smoother integration of renewable resources, supporting the broader transition towards low-carbon and climate-resilient energy systems.

Future work could expand this analysis by refining control algorithms to optimize TES charging and discharging based on real-time grid conditions, integrating distributed renewable energy sources such as rooftop PV, and assessing the combined impact of coordinated thermal and electrical storage systems. In addition, studies on the economic feasibility, regulatory barriers, user-side behavioral impacts, and large-scale deployment strategies of ECHO-TES would provide valuable insights to support decision-making and accelerate adoption. Ultimately, the results indicate that thermal storage constitutes a promising and scalable solution for enhancing the operational flexibility and resilience of modern microgrids.