Abstract

Pneumatic actuators are promising for wearable tactile interfaces, yet human perception of pneumatic stimulation is not well understood. This study examined how pressure and frequency affect tactile perception and emotional responses through three experiments. Experiment 1 measured the minimum perceivable pressure and just noticeable difference (JND). The perceptual threshold remained stable across low-frequency stimuli, while both upward and downward JNDs increased with pressure and frequency, indicating reduced sensitivity under stronger or faster stimulation. Experiment 2 evaluated perceived tactile intensity and found pressure to be the dominant factor, with frequency also contributing significantly. Experiment 3 examined emotional responses using the PAD model. Pressure and frequency jointly affected Pleasure and Arousal but minimally influenced Dominance. Moderate pressure and mid-range frequency (50 kPa, 5 Hz) produced the most positive, alert states; high-pressure, high-frequency stimulation (≥75 kPa, 10 Hz) generated unpleasant high-arousal responses; and low-pressure, low-frequency input (25 kPa, 1 Hz) led to low-arousal, negative affective states. These results offer quantitative and emotional insights that can inform the design of more realistic and expressive pneumatic haptic interfaces.

1. Introduction

Tactile feedback plays an important role in various applications, particularly in fields such as virtual reality (VR), telepresence, and human–computer interaction (HCI). Research has demonstrated that providing users with tactile feedback enriches immersion and realism, significantly improving task performance and user engagement [1]. Tactile feedback is commonly realized through innovative actuation mechanisms, employing technologies such as eccentric rotating mass (ERM) motors, linear resonant actuators (LRA), piezoelectric actuators, and pneumatic actuators [2,3]. Among these, pneumatic actuators, which generate tactile sensations through air pressure modulation, offer unique advantages, including the perception of softness in deformable objects and the ability to support adaptive tactile interactions [4]. Unlike vibration motors or electromechanical actuators that produce localized and high-frequency stimuli, pneumatic actuators usually generate broader, low-frequency, and dynamic pressure variations [5].

Pneumatic actuators are widely recognized for their skin-compatible and compliant materials, making them well-suited for wearable tactile devices and enabling more natural and comfortable interactions compared to conventional rigid electromechanical actuators. For example, Zhu et al. [6] embedded several soft pneumatic actuators into a fabric forearm sleeve to render a wide range of haptic stimuli, including compression, skin stretch, and vibration. They also mapped certain pneumatic patterns to emotional or socially meaningful sensations, indicating that pressure level, spatial distribution, and temporal envelope can be composed to communicate affect. Sonar et al. [7] developed a fingertip-mounted, skin-like tactile device that used a pneumatic actuator to simulate both surface texture and shape contour sensations. Yu et al. [8] designed a pneumatic wearable glove for the index fingertip to deliver precise force and vibration feedback, enabling tactile perception of actions such as touching a virtual board at varying speeds and grasping a virtual object. Talhan et al. [9] embedded pneumatic actuators in a jacket to mimic human touch gestures such as grab, gentle and firm touch, tap, and tickle, as performed by human fingertips. Raza et al. [10] developed a wearable pneumatic tactile actuator that can be attached to various body sites to deliver sensations of pressure, vibration, and softness.

Recent work has also explored the potential of hybrid pneumatic haptic technology for delivering richer, multimodal tactile cues. For example, Kang et al. [11] developed a wearable multimodal haptic suit that integrates pneumatic actuators and vibration motors to simulate brief and intense collision sensations, such as the impact of an explosion, a ball, or a fist. The suit was also designed to provide directional guidance and task instructions in VR. Cai et al. [12] developed a finger-worn tactile interface that combines pneumatic and vibrotactile feedback to modulate users’ perception of surface roughness in mixed reality environments. Ryu et al. [13] integrated pneumatic and electromagnetic actuators to render both low-frequency, large-amplitude sensations and high-frequency, small-amplitude sensations. In their design, the pneumatic actuator rendered signals from 0–5 Hz for shape and hardness sensations, while the electromagnetic actuator rendered signals from 5–50 Hz for texture sensation.

To design effective and realistic haptic feedback, it is essential to understand human tactile perceptual thresholds. Studies suggest that human tactile perception is highly sensitive to changes in vibration amplitude and frequency, with perceptual thresholds varying based on the contact location, skin sensitivity, and the type of actuation used [14,15,16]. The just noticeable difference (JND) provides a quantitative measure of the minimum perceptible change in a stimulus, enabling designers to ensure that actuators generate sensations that users can reliably discriminate, thereby optimizing haptic systems for human tactile sensitivity.

However, research on human perception of JNDs for pneumatic actuators remains limited, which constrains the development of accurate models for softness rendering and the design of high-fidelity pneumatic haptic interfaces. Frediani and Carpi [17] conducted a study on the perception of softness using a fingertip-mounted pneumatic tactile device on the index fingertip. A JND test was performed with reference pressure stimuli. The results showed that JND values increased with driving pressure, with a Weber constant of k = 0.15. The same device was later used to investigate softness perception on the thumb, index, and middle fingertips within a virtual environment [18]. In this case, the JND test was based on the Young’s modulus of virtual spheres rather than pressure levels. The results indicated that JND increased with the stiffness of the reference sphere, with a Weber constant of k = 0.27.

While JND provides threshold-based sensitivity insights, it is insufficient for modeling continuous perceptual scaling. To address this, researchers have applied Stevens’ power law, a more general psychophysical model that describes perceived intensity as a power function of stimulus magnitude:

In this equation, represents the perceived intensity, is the physical magnitude of the stimulus, is a scaling constant, and is a modality-specific exponent that determines the nature of the nonlinear relationship. Stevens’ power law allows capturing the nonlinear relationships between physical and perceived stimuli across a wider intensity range. For example, Ryu [19] applied Stevens’ power law to model perceived vibrotactile intensity in mobile devices. Their findings showed that perceived intensity increased as a power function of both vibration amplitude and frequency. They also revealed that the exponent in Stevens’ power law varies with frequency. However, the actuators used in these experiments were vibration motor and voice-coil actuators, rather than pneumatic actuators, which may limit direct applicability to systems using air-based haptic feedback.

Although pneumatic tactile feedback is increasingly used in interactive and immersive systems, understanding of how such stimuli are perceived, particularly at the fingertip, which is a highly sensitive and information-rich site, remains limited. Systematic data on detection and discrimination thresholds across pneumatic pressure and frequency are scarce. Evidence on how pneumatic cues shape users’ emotional and linguistic interpretations also remains limited. To address these gaps, perceptual sensitivity and semantic and affective responses to pneumatic stimulation are examined in this study. By systematically manipulating pneumatic pressure and frequency, JNDs are estimated, perceptual scaling is modeled (e.g., via Stevens’ power law), and the emotional and descriptive language associated with pneumatic changes is mapped. The resulting parameter-to-perception mappings are expected to provide a foundation for the design of more expressive and user-centered pneumatic haptic interfaces.

2. Pneumatic Tactile Device

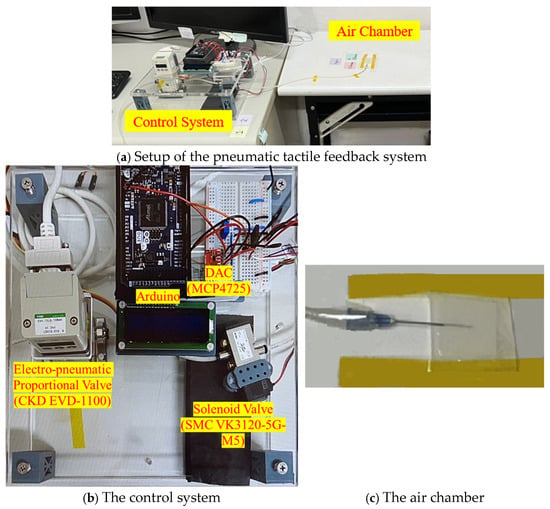

In this study, a pneumatic tactile feedback system (Figure 1) was developed. The system employs compressed air supplied by an air compressor, with airflow dynamically regulated through an SMC VK3120-5G-M5 solenoid valve and a CKD EVD-1100 electro-pneumatic proportional valve. The solenoid valve, controlled by an Arduino, enables rapid switching of airflow, while an MCP4725 digital-to-analog converter (DAC) provides the control voltage for continuous pneumatic pressure modulation via the electro-pneumatic proportional valve. The regulated compressed air is delivered to a silicone air chamber (3 mm × 3 mm × 3 mm, approximately 27 mm3), which undergoes inflation and deflation to generate perceivable tactile stimuli. The system operates at a maximum frequency of 10 Hz, and the air chamber can be inflated up to approximately 100 kPa.

Figure 1.

The pneumatic tactile feedback system.

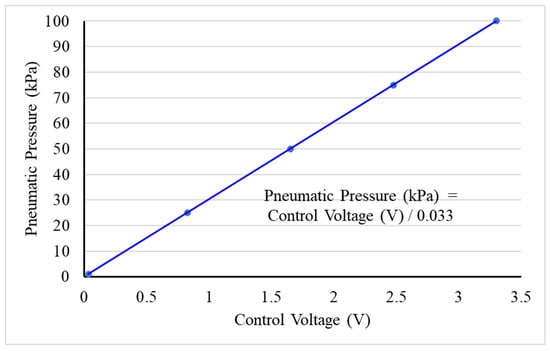

To characterize the relationship between the control voltage and the resulting pneumatic pressure, a series of calibration experiments were conducted. The Arduino program was configured to output a PWM signal, which was gradually increased from 0 to 255 in fixed increments of 15. At each step, the corresponding output voltage was measured using a digital multimeter, while the pneumatic pressure regulated by the electro-pneumatic proportional valve was simultaneously recorded. The results is shown in Figure 2. The collected data pairs of voltage and pneumatic pressure were then analyzed, yielding an approximate linear relationship between the control voltage and the resulting pneumatic pressure, as shown in Equation (2).

Figure 2.

The relationship between the control voltage and the resulting pneumatic pressure.

3. Pneumatic Tactile Perception Test

This study investigates human perceptual and emotional responses to pneumatic tactile stimulation. Therefore, the experiments were systematically designed to investigate how variations in pneumatic pressure and frequency affect (1) tactile sensitivity, (2) perceived intensity, and (3) emotional response. All three experiments were conducted on the human index fingertip.

Three experiments were conducted. Experiment 1 measured the minimum perceivable pneumatic pressure threshold and JND to evaluate perceptual sensitivity and compliance with Weber’s law. Experiment 2 assessed the subjective perception of tactile intensity across varying pneumatic pressure and frequency levels, allowing psychophysical scaling via Stevens’ power law. Experiment 3 examined the emotional and affective responses elicited by pneumatic stimuli using the Pleasure–Arousal–Dominance (PAD) model, mapping specific pressure-frequency combinations to emotional dimensions and discrete affective categories.

The air chamber could safely withstand pneumatic pressures up to approximately 100 kPa, and the solenoid valve responded reliably at frequencies up to 10 Hz. Based on the mechanical characteristics of the pneumatic tactile device, the experiments were conducted under four pneumatic pressure levels (25, 50, 75, and 100 kPa) and three frequency levels (1, 5, and 10 Hz).

The study was conducted in accordance with institutional ethical guidelines and was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Taiwan University. A priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power (Version 3.1) with an effect size of f = 0.3, α = 0.05, power = 0.80, and 12 repeated measurements. The analysis indicated that a minimum of nine participants would be sufficient to achieve adequate statistical power for our design. To ensure data completeness and to account for potential dropout or unusable data, twelve participants (8 males and 4 females), aged between 20 and 35 years, were recruited for this study. All participants reported having no history of any significant sensory impairments. Before participation, written informed consent was obtained, and participants were fully introduced to the experimental procedures.

3.1. Experimental Procedure

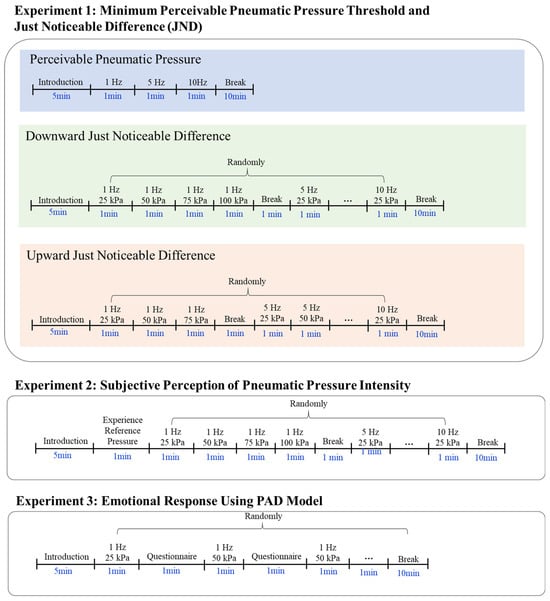

Each participant completed the three experiments to investigate different aspects of pneumatic tactile perception. The experimental procedure is shown in Figure 3. All experiments were conducted with participants seated at a desk, with their index finger resting on the silicone air chamber in a natural and relaxed state. Ambient temperature in the laboratory was controlled by maintaining air conditioning at 24 °C throughout the experiment. Ten-minute breaks were provided between each experimental session to prevent fatigue, and participants were allowed to terminate their participation at any time if they experienced discomfort, ensuring their well-being and safety.

Figure 3.

Experimental procedure. The “…” denotes that similar experimental steps were repeated.

3.1.1. Experiment 1: Minimum Perceivable Pneumatic Pressure Threshold and Just Noticeable Difference (JND)

To determine the lowest pneumatic pressure at which tactile sensation could be perceived, the reference pneumatic pressure was set to 0 kPa, and the comparison stimulus initially started at 25 kPa. A 1-up-1-down staircase procedure was employed [20]. If participants perceived a difference between the two stimuli, the comparison pneumatic pressure was decreased; otherwise, it was increased. The first three adjustments used step sizes of ±5 kPa, followed by ±1 kPa in subsequent adjustments. Each condition ended after six reversals, and the average of the reversal points was recorded as the threshold. Tests were conducted at all three frequencies (1, 5, and 10 Hz).

The JND experiment measured participants’ ability to perceive slight differences in pneumatic pressure stimuli. Reference pneumatic pressures were set at 25, 50, 75, and 100 kPa. For 25, 50, and 75 kPa, both upward and downward JNDs were evaluated, while for 100 kPa, only downward JNDs were measured due to the air-chamber pressure limit. The same 1-up-1-down staircase method was applied, starting with larger step sizes and reducing after three adjustments. Each condition was completed after six reversals, and the JND was calculated as the average pneumatic pressure difference at the reversal points.

To further quantify perceptual sensitivity, the Weber fraction () was computed for each condition using the classical Weber’s law relationship , where represents the JND (the smallest detectable change in pneumatic pressure) and is the corresponding reference pneumatic pressure. The Weber fraction thus reflects the relative sensitivity to pneumatic pressure changes rather than the absolute threshold difference. The Weber fraction was calculated for each pressure at each given frequency condition to assess tactile discrimination performance.

3.1.2. Experiment 2: Subjective Perception of Pneumatic Pressure Intensity

The purpose of this experiment is to assess how participants subjectively perceived the intensity of pneumatic pressure stimuli under varying frequency conditions. The goal was to investigate the relationship between the physical parameters of pneumatic actuation (pneumatic pressure and frequency) and the users’ perceived magnitude of tactile stimulation. Each participant was exposed to randomized stimuli covering all combinations of the four pneumatic pressure levels (25, 50, 75, and 100 kPa) and three frequencies (1, 5, and 10 Hz), resulting in 12 unique conditions.

At the beginning of the experiment, participants were first presented with three reference stimuli at 0 kPa, 50 kPa, and 100 kPa, allowing them to establish a comparative baseline for subsequent ratings. Stimuli were presented randomized to minimize learning effects and response biases. After each trial, participants were asked to report the perceived intensity of the stimulus by assigning a numerical value ranging from 0 to 100 kPa. This subjective rating method allowed for quantifying perceived intensity, facilitating further analysis of the correspondence between objective pneumatic parameters and subjective perceived tactile magnitude.

3.1.3. Experiment 3: Emotional Response Using PAD Model

The third experiment aimed to assess participants’ emotional responses to pneumatic tactile stimulation by employing the Pleasure–Arousal–Dominance (PAD) emotional model proposed by Mehrabian and Russell [21]. The PAD framework maps affective states into a three-dimensional space defined as follows:

- Pleasure (P): Pleasure indicates how pleasant or unpleasant the experience is. Higher P values indicate more pleasant and enjoyable sensations (e.g., comfort, satisfaction, or pleasant touch), whereas lower P values reflect unpleasant or uncomfortable sensations (e.g., irritation, discomfort, or dislike).

- Arousal (A): Arousal indicates the degree of physiological or psychological activation. Higher A values correspond to greater excitement, alertness, or stimulation, while lower A values denote relaxation, calmness, or drowsiness.

- Dominance (D): Dominance indicates the extent to which the individual feels in control or subordinate to the stimulus. Higher D values indicate that the participant feels in control, confident, and dominant during the experience, whereas lower D values correspond to feelings of submission, passivity, or being overwhelmed by the stimulus.

The PAD reference values for emotional adjectives were derived from Russell and Mehrabian’s standardized affective norms [22], in which 151 emotion-related adjectives were rated by participants on 9-point bipolar scales (from −4 to +4) for Pleasure, Arousal, and Dominance. The averaged ratings across participants formed a comprehensive lexicon of emotional coordinates representing the typical PAD profiles of discrete affective states. The standardized values could serve as benchmark coordinates for comparing participants’ affective responses and identifying the most similar emotional category.

To interpret PAD ratings with respect to emotional categories, participants’ affective responses to pneumatic stimuli were mapped onto Ekman’s six basic emotions, namely happiness, sadness, fear, anger, disgust, and surprise [23]. Building on previous research linking the PAD model with categorical emotions [22,24], each basic emotion was associated with a characteristic region within the PAD affective space, as shown in Table 1. The means were transformed linearly to a scale ranging from −1 to +1 with a neutral value of 0. Pleasure ranges from deep unpleasantness at –1, through a neutral midpoint at 0, to a highly pleasant state at +1. Arousal follows a similar continuum, beginning with very calm or drowsy sensations at −1, rising to a neutral level of activation at 0, and reaching intense excitement or heightened stimulation at +1. Dominance reflects the degree of control an individual feels: values near −1 describe a sense of being constrained or submissive, values around 0 indicate emotional neutrality, and values approaching +1 represent a strong feeling of agency or dominance. In general, high Pleasure, high Arousal and high Dominant correspond to happiness; low Pleasure with low Arousal and low Dominant to sad; and low Pleasure with high Arousal to fear, anger or disgust.

Table 1.

Reference positions of basic emotions in the PAD space [22].

Participants were exposed to twelve pneumatic conditions generated by four levels of pneumatic pressure and three vibration frequencies. After each stimulus, participants completed an 18-item PAD semantic differential questionnaire, based on the version utilized by Elliott et al. [25]. The questionnaire included six items for Pleasure, six for Arousal, and six for Dominance. Dimension scores were calculated as the average of corresponding items.

A quantitative classification procedure was applied, following the method proposed by Jiang et al. [26]. Specifically, the Euclidean distance was computed between each participant’s PAD score vector and the PAD coordinates of a set of predefined emotional prototypes, as shown in Table 1. The emotional category associated with the shortest distance was considered the closest match, representing the perceived affective quality of the tactile stimulus. The classification was based on the following equation:

where P, A, and D represent the participants’ mean scores on the Pleasure, Arousal, and Dominance dimensions, respectively. Correspondingly, denotes the PAD coordinates of the reference emotion, and is the Euclidean distance between the participant’s response and that reference point. The basic emotion associated with the smallest value was defined as the PAD tendency corresponding to the emotional effect of the stimulus. This approach allows for the quantitative positioning of emotional responses within PAD space, while also enabling qualitative classification into distinct affective categories based on proximity to emotional prototypes.

4. Results

4.1. Experiment 1: Minimum Perceivable Pneumatic Pressure Threshold and JND

4.1.1. Minimum Perceivable Pneumatic Pressure Threshold

The minimum pneumatic pressure required for participants to perceive tactile stimulation was measured across three frequencies (1 Hz, 5 Hz, and 10 Hz). The mean threshold for each frequency is summarized in Table 2. The standard deviations correspond to 20–30% of the mean thresholds, which is within the typical range reported in psychophysical studies involving human tactile perception. Therefore, the variability observed in our data is considered acceptable.

Table 2.

Mean minimum perceivable pneumatic pressure thresholds and standard deviations (SD) across frequencies.

A one-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed that frequency had no statistically significant effect on threshold perception (p-value = 0.182). This suggests that participants exhibited similar sensitivity to minimum perceivable pneumatic pressure stimuli across the tested frequencies of 1 Hz, 5 Hz, and 10 Hz.

4.1.2. JND Analysis

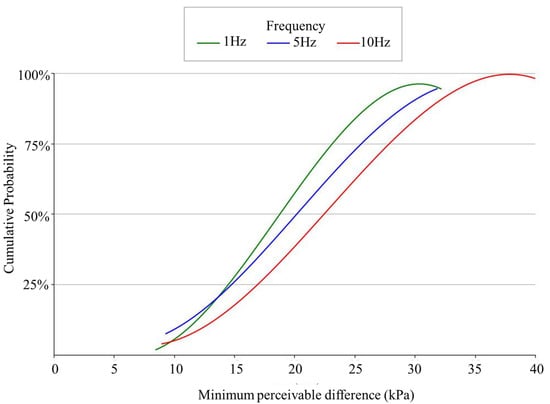

In this study, the JND was defined as the mean of the minimum perceivable differences in the reference pneumatic pressure at the 25th () and 75th () percentiles of the cumulative distribution, calculated as:

This method allowed for a robust estimation of the perceptual sensitivity range by incorporating both the lower and upper quartiles of the participants’ response distributions [27]. The cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of JND measurements were calculated for each reference pressure at every testing frequency. Figure 4 illustrates an example of the cumulative distribution of the minimum perceivable differences obtained at a reference pneumatic pressure of 75 kPa under three vibration frequencies (1 Hz, 5 Hz, and 10 Hz). The S-shaped curves clearly demonstrate the distribution of perceptual thresholds across participants. The horizontal gray lines at the 25% and 75% cumulative probabilities mark the range used to compute the JND, corresponding to the lower and upper quartiles of perceptual responses.

Figure 4.

An example of cumulative distribution curves of JND values measured during downward detection tasks at the reference pneumatic pressure of 75 kPa.

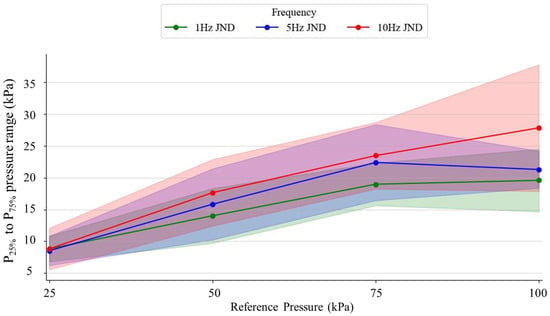

Downward JND Results (Minimum Decrease Detection)

The downward JNDs, representing the minimum detectable decreases in pneumatic pressure from reference levels (25, 50, 75, and 100 kPa), were evaluated under 1 Hz, 5 Hz, and 10 Hz conditions. The JND values obtained are summarized in Table 3. Figure 5 presents the downward JND values plotted against the reference pneumatic pressure at 1 Hz, 5 Hz, and 10 Hz. The solid lines represent the JND trends for each frequency condition. The semi-transparent shaded regions around each curve correspond to the interquartile range (IQR) between the 25th and 75th percentiles, highlighting the variability in perceptual sensitivity among participants.

Table 3.

The downward JND values obtained across frequencies (1 Hz, 5 Hz, and 10 Hz) under each reference pneumatic pressure.

Figure 5.

The downward JNDs of reference pneumatic pressures at each frequency.

A two-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the effects of pneumatic pressure intensity (25, 50, 75, and 100 kPa) and frequency (1, 5, and 10 Hz) on JND values, as shown in Table 4. The analysis revealed pneumatic pressure had a significant main effect on JND (p-value < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons revealed that JND values differed significantly across all pneumatic pressure levels. The mean JND values increased as the pressure level increased: 25 kPa (mean = 8.67 kPa) < 50 kPa (mean = 16.55 kPa) < 75 kPa (mean = 21.63 kPa) < 100 kPa (mean = 24.90 kPa), with all comparisons reaching statistical significance (p-value < 0.05).

Table 4.

Results of two-way repeated measures ANOVA for downward JND across pneumatic pressure and frequency. SS = sum of squares; df = degrees of freedom; MS = mean square; F = F-statistic; p = p-value.

In addition, the analysis also revealed a significant main effect of frequency on JND (p-value < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons indicated that JND values significantly increased with frequency. The JND at 10 Hz (mean = 19.98 kPa) was significantly higher than those at 1 Hz (mean = 16.19 kPa) and 5 Hz (mean = 17.65 kPa). However, the difference between 1 Hz and 5 Hz did not reach statistical significance (p-value = 0.211). The interaction between pneumatic pressure and frequency was not statistically significant (p-value = 0.135), indicating that there was no evident interaction effect between the two factors on JND.

The Weber fractions were computed for each condition to assess relative perceptual sensitivity across pneumatic pressures and stimulation frequencies. As summarized in Table 5, the Weber fractions ranged from approximately 0.20 to 0.35 across all conditions. Overall, the Weber fraction decreased with increasing reference pneumatic pressure. Conversely, Weber fractions tended to rise slightly with stimulation frequency.

Table 5.

The Weber fractions obtained across frequencies (1 Hz, 5 Hz, and 10 Hz) under each reference pneumatic pressure during downward discrimination tasks.

A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (Table 6) confirmed these trends. The main effect of pressure was significant (p-value = 0.01), and post hoc comparisons revealed that Weber fractions at 100 kPa (mean = 0.249) were significantly lower than at 25 kPa (mean = 0.347) (p-value = 0.016) and 50 kPa (mean = 0.331) (p-value = 0.002). The main effect of frequency was also significant (p-value = 0.003), with pairwise tests showing higher Weber fractions at 10 Hz (mean = 0.334) than at 1 Hz (mean = 0.278) (p-value = 0.018) and 5 Hz (mean = 0.299) (p-value = 0.029). No significant interaction was observed between pressure and frequency.

Table 6.

Results of two-way repeated measures ANOVA for downward Weber fractions across pneumatic pressure and frequency. SS = sum of squares; df = degrees of freedom; MS = mean square; F = F-statistic; p = p-value.

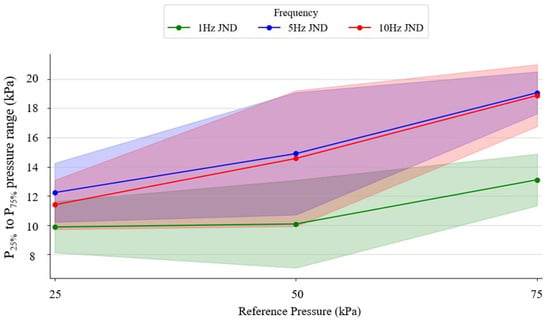

Upward JND Results (Minimum Increase Detection)

The upward JNDs represent the minimum detectable increases from reference pneumatic pressures (25, 50, 75 kPa). The upward JND results across testing frequencies are presented in Table 7. Figure 6 presents the upward JND values plotted against the reference pneumatic pressure at 1 Hz, 5 Hz, and 10 Hz. The solid lines represent the JND trends for each frequency condition. The semi-transparent shaded regions around each curve correspond to the IQR between the 25th and 75th percentiles.

Table 7.

The upward JND values obtained across frequencies (1 Hz, 5 Hz, and 10 Hz) for each reference pneumatic pressure.

Figure 6.

The upward JND of reference pneumatic pressures at each frequency.

The results of the upward JND task indicate that participants’ ability to detect increases in pneumatic pressure was significantly influenced by both pneumatic pressure and frequency. A repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant main effects of both pneumatic pressure and frequency, as well as a significant interaction between the two factors, as shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Results of two-way repeated measures ANOVA for upward JND across frequency and pneumatic pressure. SS = sum of squares; df = degrees of freedom; MS = mean square; F = F-statistic; p = p-value.

The mean JND values increased as the pressure level increased: 25 kPa (mean = 11.168 kPa) < 50 kPa (mean = 13.181 kPa) < 75 kPa (mean = 17.014 kPa). A significant main effect of pneumatic pressure was observed (p-value < 0.01). Post-hoc Bonferroni comparisons showed that JNDs at 75 kPa were significantly higher than those at both 25 kPa (p-value = 0.007) and 50 kPa (p-value = 0.01), whereas the difference between 25 kPa and 50 kPa was not statistically significant (p-value = 0.107).

Moreover, a significant main effect of frequency on JND values was also observed (p-value < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons using Bonferroni adjustment revealed that JNDs at 1 Hz (mean = 11.021 kPa) were significantly lower than those at both 5 Hz (mean = 15.396 kPa) (p-value < 0.001) and 10 Hz (mean = 14.945 kPa) (p-value < 0.001), whereas the difference between 5 Hz and 10 Hz was not significant (p-value = 1.000). These findings indicate that perceptual thresholds rose significantly between 1 Hz and 5 Hz, but showed no further increase at higher frequencies.

In addition, a significant interaction between frequency and pneumatic pressure was found (p-value < 0.01), indicating that the effect of pneumatic pressure on perceptual sensitivity varied as a function of stimulation frequency. At lower frequencies (e.g., 1 Hz), JND values increased moderately with pneumatic pressure, whereas at higher frequencies (e.g., 5 Hz and 10 Hz), the increase became more evident, implying that perceptual sensitivity was most reduced when both pneumatic pressure and frequency were high. The results indicate that both the pressure and frequency components of pneumatic stimulation significantly influence perceptual thresholds, and their interaction leads to an even greater reduction in perceptual sensitivity under strong tactile stimulation.

The Weber fractions for the upward discrimination task ranged from approximately 0.18 to 0.49 across all conditions, as shown in Table 9. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (Table 10) revealed significant main effects of both pneumatic pressure and frequency on Weber fractions. The main effect of pressure was highly significant (p-value < 0.001). Post-hoc comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment showed that Weber fractions at 25 kPa (mean = 0.428) were significantly higher than at 50 kPa (mean = 0.254) (p-value < 0.001) and 75 kPa (mean = 0.234) (p-value < 0.001), whereas the difference between 50 kPa and 75 kPa was not significant (p-value = 1.000).

Table 9.

The Weber fractions obtained across frequencies (1 Hz, 5 Hz, and 10 Hz) under each reference pneumatic pressure during upward discrimination tasks.

Table 10.

Results of two-way repeated measures ANOVA for upward Weber fractions across frequency and pneumatic pressure. SS = sum of squares; df = degrees of freedom; MS = mean square; F = F-statistic; p = p-value.

A significant main effect of frequency was also observed (p-value < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons indicated that Weber fractions were significantly larger at 5 Hz (mean = 0.340) and 10 Hz (mean = 0.326) than at 1 Hz (mean = 0.250) (p-value = 0.001), whereas the difference between 5 Hz and 10 Hz was not significant (p-value = 0.603). The interaction between pressure and frequency was not significant (p-value = 0.237), indicating that these effects were independent.

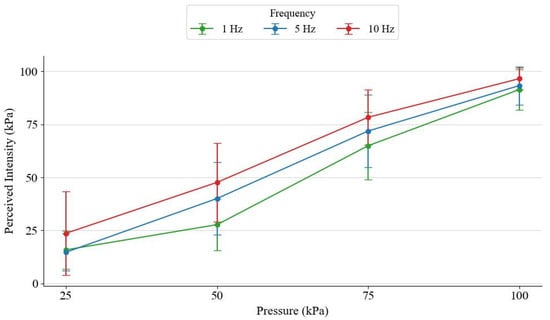

4.2. Experiment 2: Subjective Perception of Pneumatic Pressure Intensity

Table 11 and Figure 7 show the relationship between perceived pneumatic pressure intensity and the reference pneumatic pressures. A repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the effects of pneumatic pressure and stimulation frequency on the subjective perception of tactile intensity (Table 12). The results revealed a significant main effect of pneumatic pressure (p-value < 0.001), indicating that as the pressure increased, the simulated haptic feedback became more perceivable.

Table 11.

The relationship between perceived pneumatic pressure intensity and the reference pneumatic pressures.

Figure 7.

Perceived intensity across pneumatic pressure levels at three stimulation frequencies.

Table 12.

Results of two-way repeated measures ANOVA for pneumatic pressure and frequency. SS = sum of squares; df = degrees of freedom; MS = mean square; F = F-statistic; p = p-value.

The main effect of frequency was also statistically significant (p-value = 0.001), indicating that as the frequency increased, the simulated haptic feedback became more perceivable. Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni adjustment revealed that perceived intensity was significantly higher at 10 Hz compared to both 1 Hz (p-value = 0.010) and 5 Hz (p-value = 0.008), whereas the difference between 1 Hz and 5 Hz was not significant (p-value = 0.461). These findings suggest that while frequency influences perceived tactile intensity, the effect becomes prominent at higher stimulation frequencies. In addition, although the main effect of frequency reached a significant difference, its effect ( = 0.366) was considerably smaller than that of pneumatic pressure, indicating a relatively limited influence of frequency on perceived intensity. However, the interaction between pneumatic pressure and frequency was not statistically significant (p-value = 0.096), suggesting that the effect of frequency on perceived tactile intensity did not depend on the level of pneumatic pressure.

To further characterize the psychophysical relationship between physical pneumatic pressure and subjective perception, Stevens’ power law () was fitted to the data for each frequency condition, where denotes perceived intensity, is the physical pneumatic pressure, is a scaling constant, and represents the perceptual growth exponent. The fitted exponents were n = 1.28 for 1 Hz, n =1.36 for 5 Hz, and n = 1.03 for 10 Hz.

4.3. Experiment 3: Emotional Response Using PAD Model

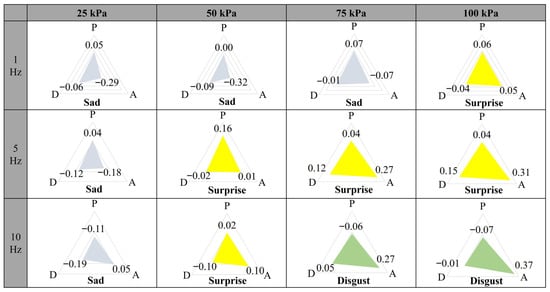

To investigate the affective characteristics elicited by tactile stimulation, participants rated twelve combinations of pneumatic pressure and vibration frequency using the PAD model. The mean PAD scores and their corresponding emotional classifications are summarized in Table 13, with graphical representations shown in Figure 8. Across all conditions, distinct PAD vector profiles emerged, indicating systematic variations in emotional responses as a function of both pneumatic pressure and frequency.

Table 13.

PAD Scores and emotional classifications across stimulus conditions.

Figure 8.

Radar plots showing PAD profiles for all twelve stimulus conditions. Each radar chart represents a unique combination of frequency (1, 5, 10 Hz) and pneumatic pressure (25, 50, 75, 100 kPa). Color coding reflects emotion classification: gray for Sad, yellow for Surprise, and green for Disgust. Axis labels represent the three PAD dimensions: Pleasure (P), Arousal (A), and Dominance (D). Values for each dimension are numerically displayed outside the corresponding axis.

The results indicate that the effects of pneumatic pressure on Pleasure varied across frequency conditions. At 25, 75, and 100 kPa, Pleasure values decreased with increasing frequency, whereas at 50 kPa, Pleasure increased as frequency rose. This trend indicates that the relationship between frequency and Pleasure was dependent on pressure intensity, suggesting that pneumatic pressure modulated the direction of frequency-induced changes in pleasantness.

For Arousal, both pneumatic pressure and stimulation frequency exerted consistent effects. Arousal scores increased progressively with higher pressure levels and higher stimulation frequencies, demonstrating that tactile stimuli with greater mechanical intensity and temporal density elicited stronger physiological activation.

In contrast, Dominance scores remained close to zero across all conditions, showing no systematic variation with either pneumatic pressure or frequency. This result indicates that pneumatic stimulation had a minimal impact on participants’ perceived sense of control.

5. Discussion

This study systematically investigated the psychophysical and emotional responses elicited by pneumatic tactile stimulation on the human fingertip by varying both pneumatic pressure amplitude (25, 50, 75, and 100 kPa) and frequency (1, 5, and 10 Hz). There are four main types of cutaneous mechanoreceptors in glabrous skin [28,29,30]. Among them, slow-adapting type I (SA I) receptors, associated with Merkel cells, respond to sustained pressure, while rapid-adapting type I (RA I) receptors, linked to Meissner corpuscles, detect low-frequency light touch and dynamic stimuli such as flutter or motion across the skin. Meissner corpuscles are most responsive to stimulation in the 10–60 Hz range. In this study, the frequency and pressure ranges used in the experiments mainly stimulated Merkel cells and Meissner corpuscles.

Through three complementary experiments, the study evaluated minimum perceptual thresholds, JNDs, subjective intensity ratings, and affective responses. The results provide new insights into how pneumatic stimulation parameters influence both somatosensory discrimination and emotional experience, offering foundational knowledge for designing affect-aware tactile interfaces.

5.1. Minimum Perceivable Pneumatic Pressure Threshold and JND

In Experiment 1, the minimum pneumatic pressure required for tactile detection was not significantly affected by stimulation frequency within the 1–10 Hz range. This suggests that the perceptual pressure threshold for pneumatic stimuli stays relatively stable across low-frequency temporal profiles. This could be because, at low frequencies (1–10 Hz), tactile detection primarily relies on Merkel cells, which are sensitive to pressure intensity rather than changes in frequency. Since Merkel cells respond to steady or slowly changing skin deformation, the minimum pressure threshold remains almost constant across this frequency range.

The results of the JND demonstrate that both frequency and pneumatic pressure significantly affect participants’ ability to detect and differentiate pneumatic stimuli. In both the downward and upward JND tasks, the findings revealed that JND values increased with higher frequencies and reference pneumatic pressures, suggesting that tactile discrimination under pneumatic stimulation generally decreases as stimulus intensity increases.

In this study, the Weber fraction, the ratio of JND to reference pressure, is not a fixed constant. For both the upward and downward discrimination tasks, although the JND increases with pneumatic pressure, it does so at a slower rate than the reference pressure, resulting in a decrease in the Weber fraction. In contrast, the Weber fraction increases with increasing frequency. Previous tactile research has also demonstrated that the Weber fraction might not be a fixed constant. For example, Debats et al. [31] demonstrated that in active arm-force discrimination, the Weber fraction decreased from 0.18 at 5 N to 0.10 at 20 N, indicating that Weber fraction decreases with increasing force. Merchel and Altinsoy [32] reported that for whole-body vibration stimuli, the Weber fraction increased from 0.14 at 20 Hz to 0.21 at 40 Hz, indicating the Weber fraction increases with increasing frequency. The present study is consistent with previous research showing that human tactile perception decreases more rapidly with increasing frequency, but more slowly with increasing pressure or force.

Furthermore, compared with previous findings on pneumatic tactile perception [17], which reported a Weber fraction of 0.15 using a fingertip-mounted pneumatic actuator, the Weber fraction observed in the present study was slightly higher (k = 0.17–0.49). The relatively higher Weber fraction observed in the present study may be attributed to the dynamic nature or higher frequency of the pneumatic stimulation. Unlike static or quasi-static actuation in previous research, where pressure changes occurred slowly and allowed participants to perceive subtle differences in indentation and contact area, the dynamic conditions in this study provided less time to detect fine pressure variations, resulting in larger Weber fraction values.

5.2. Subjective Perception of Pneumatic Pressure Intensity

Experiment 2 examined subjective intensity ratings across 12 frequency–pressure combinations. Pressure exerted a strong main effect on perceived intensity, consistent with prior tactile perception research [33] where amplitude typically dominates sensory magnitude judgments, whereas stimulation frequency serves as a secondary but statistically significant modulator.

Perceived intensity increased with higher applied pressure, consistent with prior psychophysical findings that tactile magnitude grows as a function of stimulus strength. The fitted exponents from Stevens’ power law (n = 1.03–1.36) revealed an almost linear, yet slightly nonlinear, perceptual scaling between physical pressure and subjective magnitude. Notably, the highest exponent was observed at 5 Hz (n = 1.36), suggesting that moderate temporal modulation (among 1 Hz, 5 Hz, and 10 Hz) enhances perceptual gain and improves sensitivity to pressure variation.

This frequency-dependent variation in the perceptual growth exponent indicates that frequency affects the perceived intensity. Similar patterns have been observed in previous vibrotactile perception studies. Ryu [19] applied Stevens’ power law to model perceived motor vibration intensity in mobile devices and found that the exponent varies with frequency, showing that perceptual scaling becomes steeper at certain temporal ranges. Likewise, Hwang et al. [34] reported significant differences in the exponent across vibration frequencies (20–320 Hz), demonstrating that frequency can modify perceptual gain depending on the temporal properties of stimulation.

5.3. Emotional Evaluation Using the PAD Model

In Experiment 3, participants’ emotional responses to pneumatic stimulation were evaluated using the PAD model, providing a dimensional analysis of affective quality. The results revealed that pneumatic pressure and frequency exerted distinct yet interrelated effects on emotional dimensions. Pleasure decreased as stimulation frequency increased, whereas at 50 kPa, the opposite pattern emerged, with Pleasure slightly increasing at higher frequencies. This bidirectional trend suggests that pneumatic pressure modulated the direction of frequency-induced changes in pleasantness. Guest et al. [35] also reported that tactile pleasantness decreases with increasing normal force and surface roughness, supporting the view that affective touch is highly sensitive to stimulus strength and mechanical load.

In contrast, Arousal was jointly and positively influenced by both pneumatic pressure and frequency. Arousal scores increased systematically as either parameter rose, indicating that tactile stimuli with greater mechanical intensity and temporal density elicited stronger physiological activation. This observation is consistent with the findings of Yoo et al. [36], who demonstrated that higher vibration frequencies and amplitudes in tactile icons increased emotional intensity and perceived urgency. Dominance, however, remained largely unaffected, with scores close to zero across all conditions, indicating that pneumatic stimulation minimally influenced participants’ perceived sense of control.

These results suggest that pneumatic pressure and stimulation frequency jointly modulate Pleasure and Arousal, thereby defining the affective character of tactile perception. In this study, moderate pneumatic pressure and mid-range frequency (5 Hz, 50 kPa) elicited the most positive and alert affective responses (categorized as Surprise). Surprise in the PAD model is context-dependent, it may be neutral or mildly positive depending on the Pleasure value. In our results, most Surprise responses were located near the neutral-to-positive part of the PAD space, indicating that participants perceived the stimuli as unexpected rather than unpleasant. In addition, high-frequency, high-pressure combinations (10 Hz, ≥75 kPa) induced unpleasant affective states (Disgust), and low frequency, low-pressure combinations (1 Hz, 25 kPa) evoked low-arousal negative affective states (Sadness). These results demonstrate that specific tactile stimulation parameters can systematically modulate emotional valence, highlighting the importance of carefully calibrating both temporal and mechanical stimulation properties in affective haptic interface design.

6. Conclusions

As tactile technologies become more integrated into everyday contexts, soft pneumatic actuators present exciting opportunities for wearable and affective haptic devices. Consequently, adjusting tactile parameters to influence both perception and emotion has become increasingly important in design. This study examined how pneumatic pressure and stimulation frequency influence human tactile perception and affective response through three complementary experiments. The findings demonstrate that both physical and emotional aspects of touch are strongly shaped by the intensity and temporal characteristics of pneumatic stimulation.

In the first experiment, the minimum perceivable pneumatic pressure threshold and JND were measured. The perceptual threshold remained relatively stable within the 1–10 Hz range, suggesting that tactile detection in this frequency band primarily relies on the activity of Merkel cells, which respond to sustained or slowly changing pressure. Both upward and downward JNDs increased with pneumatic pressure and frequency, suggesting that higher levels of pneumatic stimulation reduced discrimination sensitivity. In the second experiment, subjective intensity ratings revealed significant effects of both pressure and stimulation frequency, with pressure exerting a stronger and more consistent influence on perceived tactile force. Finally, emotional evaluations based on the PAD model indicated that both pressure and frequency significantly affected Pleasure and Arousal, while Dominance remained largely unchanged. These results show that pneumatic stimulation conveys not only sensory information but also emotional expressiveness. These insights establish foundational principles for perceptual and affective design in pneumatic haptics.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. First, the pneumatic stimulus parameters were restricted to four pressure levels and three frequencies. A broader range of waveform shapes, temporal envelopes, or spatial actuation patterns may produce additional perceptual and emotional effects that were not captured in this study, such as happiness, fear, or anger. Second, environmental conditions were only partially regulated, with temperature controlled but humidity not specifically monitored. Although pneumatic actuation is relatively insensitive to humidity, variations in ambient humidity may influence the condition of the fingertip skin or even participants’ emotional states. Finally, the participant sample consisted mainly of young adults, limiting the generalizability of the results to broader populations with potentially different tactile sensitivity or affective reactivity.

Future work should address these limitations to further refine the design principles for pneumatic haptic interfaces. Different waveform shapes, duty cycles, temporal envelopes, and spatial actuation patterns should be tested. These variations can help reveal richer and more detailed links between touch and emotion. Adding physiological or behavioral measures can further clarify how tactile input and affective experience interact. This information can support the development of adaptive pneumatic systems that respond to or adjust users’ emotional states. Such emotionally responsive pneumatic interfaces can improve immersion, communication, and engagement in next-generation soft human–machine interaction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-Y.L., C.-T.Y., H.-H.K. and W.-H.H.; Methodology, T.-Y.L., C.-T.Y., C.-T.Y. and W.-H.H.; Validation, S.S., H.-H.K. and W.-H.H.; Formal analysis, T.-Y.L.; Investigation, C.-T.Y. and H.-H.K.; Resources, T.-C.H. and W.-H.H.; Data curation, T.-Y.L. and T.-C.H. and W.-H.H.; Writing—original draft, T.-Y.L.; Writing—review & editing, S.S.; Supervision, S.S., H.-H.K. and C.-T.Y.; Project administration, S.S. and H.-H.K.; Funding acquisition, H.-H.K., C.-T.Y. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Industrial Technology Research Institute, Hsinchu, Taiwan, under contract number 202551F0078, and by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, under contract number NSTC 113-2221-E-002-093.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gani, A.; Pickering, O.; Ellis, C.; Sabri, O.; Pucher, P. Impact of haptic feedback on surgical training outcomes: A randomised controlled trial of haptic versus non-haptic immersive virtual reality training. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 83, 104734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangxiao, W.; Yuan, G.; Shiyi, L.; Weiliang, X.; Jing, X. Haptic display for virtual reality: Progress and challenges. Virtual Real. Intell. Hardw. 2019, 1, 136–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Liu, S.; Yang, C.; Yang, Z.; Liu, T.; Xu, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhai, X. A review of smart materials in tactile actuators for information delivery. J. Carbon Res. 2017, 3, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Rao, Z.; Yang, M.; Yu, C. Wearable haptic feedback interfaces for augmenting human touch. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 2417906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yao, K.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Jia, H.; Liu, Y.; Yiu, C.K.; Park, W.; Yu, X. Recent advances in multi-mode haptic feedback technologies towards wearable interfaces. Mater. Today Phys. 2022, 22, 100602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Memar, A.H.; Gupta, A.; Samad, M.; Agarwal, P.; Visell, Y.; Keller, S.J.; Colonnese, N. Pneusleeve: In-fabric multimodal actuation and sensing in a soft, compact, and expressive haptic sleeve. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 25–30 April 2020; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sonar, H.A.; Huang, J.-L.; Paik, J. Soft Touch using Soft Pneumatic Actuator–Skin as a Wearable Haptic Feedback Device. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 3, 2000168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Cheng, X.; Peng, S.; Cao, Y.; Lu, Y.; Li, B.; Feng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Jiao, Z.; et al. A self-sensing soft pneumatic actuator with closed-Loop control for haptic feedback wearable devices. Mater. Des. 2022, 223, 111149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhan, A.; Yoo, Y.; Cooperstock, J.R. Soft Pneumatic Haptic Wearable to Create the Illusion of Human Touch. IEEE Trans. Haptics 2024, 17, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raza, A.; Hassan, W.; Jeon, S. Pneumatically Controlled Wearable Tactile Actuator for Multi-Modal Haptic Feedback. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 59485–59499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Lee, C.-G.; Kwon, O. Pneumatic and acoustic suit: Multimodal haptic suit for enhanced virtual reality simulation. Virtual Real. 2023, 27, 1647–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Chen, Z.; Gao, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, X.; Zhu, K. ViboPneumo: A Vibratory-Pneumatic Finger-Worn Haptic Device for Altering Perceived Texture Roughness in Mixed Reality. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2025, 31, 3957–3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Y.; Park, J.; Hong, J.; Kee, H.; Park, S. A Hybrid haptic device integrating pneumatic and electromagnetic actuators for realistic tactile signal feedback. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2025, 7, 2400674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ævarsson, E.A.; Ásgeirsdóttir, T.; Pind, F.; Kristjánsson, Á.; Unnthorsson, R. Vibrotactile threshold measurements at the wrist using parallel vibration actuators. ACM Trans. Appl. Percept. (TAP) 2022, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahns, D.A.; Perkins, N.; Sahai, V.; Robinson, L.; Rowe, M. Vibrotactile frequency discrimination in human hairy skin. J. Neurophysiol. 2006, 95, 1442–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zippenfennig, C.; Wynands, B.; Milani, T.L. Vibration perception thresholds of skin mechanoreceptors are influenced by different contact forces. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frediani, G.; Carpi, F. Tactile display of softness on fingertip. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frediani, G.; Carpi, F. Finger-mounted tactile display of softness for virtual reality. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Industry 4.0 & IoT (MetroInd4. 0 & IoT), Firenze, Italy, 29–31 May 2024; pp. 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, J. Psychophysical model for vibrotactile rendering in mobile devices. Presence 2010, 19, 364–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzfeld, C.; Werthschützky, R. Just noticeable differences of low-intensity vibrotactile forces at the fingertip. In Proceedings of the Haptics: Perception, Devices, Mobility, and Communication: International Conference, EuroHaptics 2012, Tampere, Finland, 13–15 June 2012; Proceedings, Part II. pp. 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.A.; Mehrabian, A. Evidence for a three-factor theory of emotions. J. Res. Personal. 1977, 11, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. An argument for basic emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1992, 6, 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, J.R.J.; Scherer, K.R.; Roesch, E.B.; Ellsworth, P.C. The World of Emotions is not Two-Dimensional. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, K.; Hall, M.; Meng, J.G. The impact of emotions on consumer attitude towards a self-driving vehicle: Using the pad (pleasure, arousal, dominance) paradigm to predict intention to use. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2021, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, N.; Li, R.; Liu, C.; Fang, H. Application of PAD emotion model in user emotional experience evaluation. Packag. Eng. 2021, 42, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, L.; Niwa, M.; Noma, H.; Susami, K.; Yanagida, Y.; Lindeman, R.W.; Hosaka, K.; Kume, Y. Towards effective information display using vibrotactile apparent motion. In Proceedings of the 2006 14th Symposium on Haptic Interfaces for Virtual Environment and Teleoperator Systems, Alexandria, VA, USA, 25–26 March 2006; pp. 445–451. [Google Scholar]

- Cacciamani, E.B.G.L. Sensation and Perception, 11th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, R.S.; Flanagan, J.R. Coding and use of tactile signals from the fingertips in object manipulation tasks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.A.; Sarter, N.B. Tactile displays: Guidance for their design and application. Hum. Factors 2008, 50, 90–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyzabadi, S. Human force discrimination during active arm motion for force feedback design. IEEE Trans. Haptics 2013, 6, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merchel, S.; Altinsoy, M.E.; Stamm, M. Just-noticeable frequency differences for whole-body vibrations. In Proceedings of the INTER-NOISE and NOISE-CON Congress and Conference, Osaka, Japan, 4–7 September 2011; pp. 2234–2239. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, S. Tactile vibration: Dynamics of sensory intensity. J. Exp. Psychol. 1959, 57, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, I.; Seo, J.; Kim, M.; Choi, S. Vibrotactile perceived intensity for mobile devices as a function of direction, amplitude, and frequency. IEEE Trans. Haptics 2013, 6, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, S.; Dessirier, J.M.; Mehrabyan, A.; McGlone, F.; Essick, G.; Gescheider, G.; Fontana, A.; Xiong, R.; Ackerley, R.; Blot, K. The development and validation of sensory and emotional scales of touch perception. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2011, 73, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Yoo, T.; Kong, J.; Choi, S. Emotional responses of tactile icons: Effects of amplitude, frequency, duration, and envelope. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE World Haptics Conference (WHC), Evanston, IL, USA, 22–26 June 2015; pp. 235–240. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).