Abstract

To address the limitation of the IEC 60287 standard in accurately representing the electrothermal characteristics of cables under different grounding conditions, this study proposes a modified equivalent thermal resistance method, using a YJLW03-Z 64/110 1 × 1200 mm2 high-voltage single-core cable as a case study to analyze three typical grounding modes, namely two-end solid bonding, segmented solid bonding, and semiconductive outer sheath. Equivalent circuit models are established to calculate the induced current, voltage, and losses of the metallic sheath and armor. Based on these results, the equivalent thermal resistance model is modified, and correction formulas for cable ampacity considering grounding effects are derived. The proposed model is validated through numerical simulations under typical laying conditions and field tests conducted in Zhoushan, Zhejiang Province. Results show that grounding modes significantly influence the electromagnetic losses and temperature distribution of cables. Segmented solid bonding effectively reduces sheath losses and increases ampacity, while its enhancement tends to stabilize beyond two bonding sections. The semiconductive outer sheath improves electric field distribution and thermal stability with limited ampacity gain. This study provides theoretical guidance and engineering reference for optimizing grounding designs, ampacity evaluation, and digital operation of high-voltage cable systems.

1. Introduction

State Grid manages the largest power grid, characterized by the highest voltage levels, the most robust energy resource allocation capabilities, and the largest integration of new energy sources. To address these demands, there is an urgent need to advance management transformation through digitalization and modern methodologies. The digital transformation initiatives at State Grid necessitate enhanced standards for the digital operation and maintenance of cables. Consequently, it is imperative that cable systems ensure precise calculations of electro-thermal field while significantly increasing the existing calculation speed to meet operational objectives. For digital operation and maintenance systems [1], analytical methods are predominantly used due to their computational speed and acceptable accuracy. This method calculates the electro-thermal field of cables in accordance with the IEC60287 standard established by the International Electrotechnical Commission, commonly referred to as the equivalent thermal resistance calculation method [2,3,4,5,6]. In the mid-20th century, Neher and McGrath introduced the NM method, building upon prior research to establish the cable thermal path model for the first time. They addressed the temperature rise of cables under various working conditions and installation methods, thereby deriving the theoretical values for the distribution of the cable temperature field [7]. Following extensive research and refinement, the International Electrotechnical Commission formalized the IEC60287 standard in the 1980s, leading to its global adoption. This standard delineates a thermal path model for power cables and facilitates the determination of the temperature field distribution through the calculation of parameters such as thermal resistance [8,9,10,11,12].The IEC60287 standard primarily employs the equivalent thermal resistance method to calculate the electro-thermal field of cables under typical operating conditions. This approach significantly simplifies calculations, allowing power designers to quickly assess cable operating conditions. However, due to complex real-world environments and installation methods, notable discrepancies exist between the standard calculations and the actual electro-thermal field distribution [13,14].The primary limitations are as follows: ① When power cables are installed in multiple circuits or clusters, the calculation formulas in IEC 60287 exhibit limitations. They do not account for eddy current losses in the outer sheath, proximity effects between adjacent conductors, or the impact of other component losses on the electro-thermal field distribution [15]. ② The resistivity of materials, such as cable core conductors and metal sleeves, varies with temperature and location. However, the resistivity values provided by the IEC60287 standard are fixed, making it impossible to accurately calculate the specific conditions at varying temperatures and positions. ③ The temperature distribution on the surface of the cable and the surrounding soil is uneven. However, the IEC60287 standard presumes that the environment surrounding the power cable is ideal, with all surfaces maintained at an isothermal state. ④ IEC60287 does not consider the effects of airflow on various heat transfer mechanisms. Consequently, when cables are installed in trenches, the calculations of the electro-thermal field distribution may yield certain inaccuracies under different methodologies.

To improve the accuracy of the equivalent thermal resistance method, researchers have combined it with iterative techniques. This integrated approach is widely used to calculate the electro-thermal field distribution of cables. Gang Liu [16] et al. introduced an improved analytical method based on a quasi-three-dimensional thermal model, integrating it with an iterative solution for cables laid in short pipes. They corrected the equivalent thermal path parameters through iteration and coupling with the actual thermal field, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the IEC60287 method in complex environments. Dan Pang et al. [17] employed the finite volume method and the equivalent thermal path method to calculate the external resistance of the cable. They incorporated the calculation results into an analytical formula, enabling rapid and accurate assessments of the cable’s current-carrying capacity. Verification was conducted under both uniform and non-uniform soil conditions, yielding results that surpassed the accuracy of traditional analytical algorithms. BRAKELMANN H et al. [18] offered corrections and numerical validation based on the IEC method to address the rated deviation resulting from the short section layout at the line’s end. This approach enhanced overall accuracy in conjunction with the segmented iterative thermoelectric coupling calculations. Xiao, R [19] et al. developed a rapid transient temperature rise model tailored for complex direct-burial conditions, achieving enhanced speed and accuracy through the use of equivalent thermal circuits and iterative updates. By integrating the iterative method, they significantly improved the calculation accuracy of the equivalent thermal resistance method outlined in IEC60287. Nonetheless, the equivalent thermal resistance calculation method specified by IEC60287 does not adequately account for the specific impact of losses in each component on the cable’s electro-thermal field calculations. Consequently, the results obtained do not accurately reflect the actual operating conditions. Despite this limitation, the equivalent thermal resistance method is characterized by a straightforward calculation process and relatively rapid computation speed, leading to its widespread application both domestically and internationally [20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

This paper examines three grounding methods: two-end solid bonding, segmented solid bonding, and semiconductive outer sheath. The study focuses on the YJLW03-Z 64/110 1 × 1200 mm2 high-voltage single-core power cable as the primary research subject. It establishes equivalent circuits for each grounding method and calculates the associated losses and induced currents. The electro-thermal field distribution formula based on the IEC 60287 equivalent thermal resistance method is corrected. This allows for the development of a revised ampacity calculation model that explicitly accounts for the influence of grounding modes. Through numerical analysis and empirical measurement under typical installation conditions, this research conducts a comparative study of the variations and influencing factors affecting current-carrying capacity across different grounding methods. This work provides a theoretical foundation and engineering guidance for the grounding design and current-carrying capacity verification of high-voltage cables.

2. Establishment of Cable Equivalent Circuits Under Different Grounding Methods

This section outlines the establishment of the equivalent circuits used for modeling the thermal and electrical behavior of cables under different grounding methods. The models consider the electromagnetic coupling between the conductor, metallic sheath, and armor, with the objective of calculating the losses and induced currents associated with grounding configurations. This provides an analytical foundation for assessing how grounding modes influence cable temperature rise and current-carrying capacity.

In developing the equivalent circuits and analytical models, several simplifying assumptions were made to ensure clarity and analytical tractability. First, the temperature-dependent variation in electrical resistivity for the conductor, metallic sheath, and armor was not considered. Although resistivity changes with temperature in practice, these parameters are treated as constants in the IEC 60287 standard, which this study follows for consistency and to maintain a concise analytical framework.

Second, the variation in soil thermal conductivity was not included. Soil thermal properties may change with environmental and geological conditions, but such variations primarily affect the external thermal resistance of buried cables and do not alter the electromagnetic interactions that determine grounding-related sheath and armor losses. Therefore, a representative constant value of soil thermal conductivity was used in the analysis.

2.1. Equivalent Thermal Resistance Method

The IEC60287 standard defines a thermal path model for power cables and determines the temperature field distribution by calculating parameters such as thermal resistance [27,28]. This standard primarily employs the equivalent thermal resistance method to assess the electro-thermal field of cables under typical operating conditions.

The formula for calculating the AC resistance of the cable core conductor is:

Here, R0 represents the DC resistance of the cable core conductor, Ys denotes the skin effect factor, and Yp signifies the proximity effect factor.

The equation for calculating the Joule heat loss of the cable core conductor is:

Here, Ic represents the current value of the cable core conductor.

The calculation formula for insulating dielectric loss is:

Here, tanδ denotes the insulation loss factor; U0 signifies the voltage to ground; and C represents the capacitance value per unit length associated with the cable. Its calculation formula is:

Here, ε denotes the dielectric constant of the insulating material, Di represents the diameter of the insulating material devoid of a shielding layer, and dc indicates the diameter of the cable core conductor.

The losses λ1 associated with the cable armor layer comprise two components: hysteresis loss λ1′ and eddy current loss λ1″. The total loss of the armor layer is:

The calculation formula for hysteresis loss λ1′ of the armor layer of a single-core cable is:

In the formula, S denotes the distance between each conductor cable core; δ represents the equivalent thickness of the cable armor layer; K indicates the relative magnetic permeability coefficient; and dA signifies the equivalent diameter of the armor layer.

The calculation formula for the eddy current loss λ1″ in the armor layer of a single-core cable is:

The calculation formula for the thermal resistance of the cable insulation layer part is:

Here, ρT1 represents the thermal resistance coefficient of the cable insulation material, while dc denotes the diameter of the cable core. The variable t1 indicates the thickness of the insulating material situated between the cable core and the metal sheath.

The calculation formula for the thermal resistance of the cable lining layer is:

Here, ρT2 represents the thermal resistance coefficient of the cable lining layer, while ds denotes the outer diameter of the metal sheath. Additionally, t2 indicates the thickness of each section of the cable’s inner lining layer.

The calculation formula for the thermal resistance of the cable’s outer sheath is:

Here, ρT3 represents the thermal resistance coefficient of the cable’s outer sheath, while da denotes the outer diameter of this sheath. Additionally, t3 indicates the thickness of the outer protective layer material.

The calculation formula for the thermal resistance of the medium in the cable laying environment is:

Here, ρT4 represents the thermal resistance coefficient of the medium in the cable laying environment, L denotes the depth of cable burial, and De indicates the actual outer diameter of the cable.

Taking into account the resistance of each component of the cable, as well as the results of various loss types and the thermal resistance associated with each segment, the formula for calculating the current-carrying capacity of the cable is derived as follows:

Here, I denotes the current-carrying capacity of the required cable, while θc indicates the maximum temperature at which the cable can function normally with the specified insulating material. R represents the direct current resistance per unit length of the conductor within the AC cable core, as calculated by Equation (1). Wd refers to the insulating dielectric loss, determined by Equation (3). Additionally, λ1 encompasses the hysteresis loss and eddy current loss of the armor layer, as calculated by Equation (5).

2.2. Two-End Solid Bonding

2.2.1. Equivalent Circuit Diagram

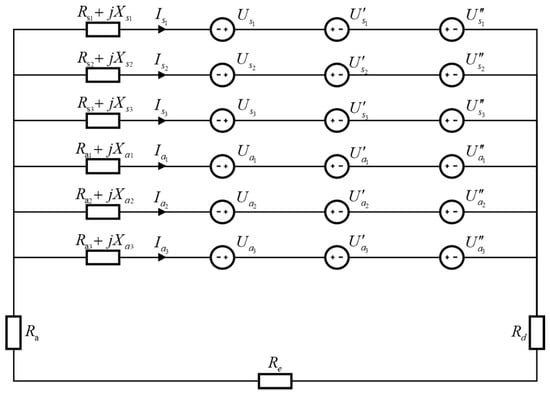

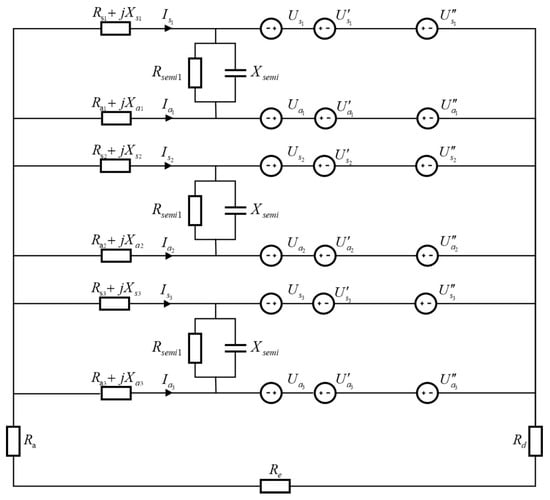

The metal sheath layer and the armor layer are interconnected and grounded at both ends, ensuring that no short-circuit occurs in the intermediate section. Figure 1 illustrates the equivalent circuit used for calculating the circulating current, while Equation (14) presents the calculation for the circulating current within the metal sheath layer and the armor layer.

Figure 1.

Equivalent circuit of the two-end solid bonding grounding mode.

Here, Rd denotes the grounding resistance of the cable, while Re signifies the equivalent leakage resistance of the surrounding soil. Rsi, Xsi, Rai, and Xai represent the resistance and self-inductive reactance of the materials comprising the metal sheath and armor layers. Isi and Iai indicate the circulating currents generated in the i-th phase of the metal sheath and armor layers, respectively, where i ranges from 1 to 3. The induced voltage Usi, U′si and U″si refer to the voltage generated in the i-th phase of the metal sheath material by the current flowing through the cable core conductor, as well as by the circulating currents in the metal sheath and armor layers. Additionally, it encompasses the induced voltage in the i-th phase of the armor layer material, which is produced by the circulating currents associated with the cable core conductor, the metal sheath layer, and the armor layer.

2.2.2. Calculation of Induced Potential for Metal Sheaths

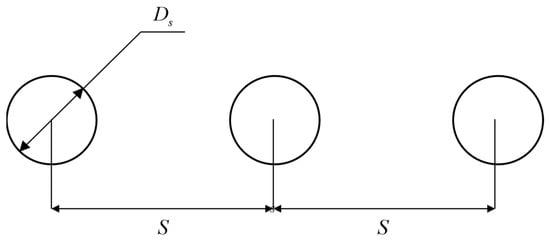

As shown in Figure 2, it is a schematic diagram for calculating the induced electromotive force of a single-loop three-phase cable sheath.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of calculation of induced potential of cable sheath.

Given that the thickness of the technical sheath is significantly smaller than the diameter of the cable, its internal induction can be disregarded. If S represents the distance between two cables, the inductance of the cable sheath per unit length is:

The induced electromotive force on the cable sheath per unit length is:

According to Figure 1 and Figure 2, the current flowing through the cable has the following relationship:

According to Figure 2, write the unit length sheath inductance of the three-phase cable as:

Here, each parameter is taken as the first phase as an example:

Then Equation (19) can be expressed as:

The induced electromotive force of the three-phase cable can also be expressed as:

Therefore, the matrix expression of the induced electromotive force of the metal sheath can be written as:

Thus, the induced electromotive force of the single-loop three-phase laid cable sheath is calculated.

2.2.3. Calculation of Armored Induced Current

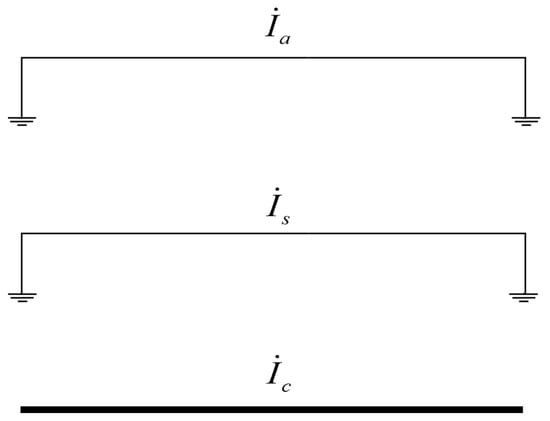

To calculate the induced current in the cable armor when both ends are grounded, an equivalent circuit is established, as illustrated in Figure 3. In this circuit, the variables İa, İs and İc represent the current values flowing through the armor, metal sheath, and cable core, respectively.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of induction potential calculation for Marine cable armoring.

To solve for İa and İs, it is necessary to establish the induced current equations as shown in Equation (24) based on Figure 1 and Figure 3:

Here, , , and represent the voltages at both ends of the armor, sheath, and core, respectively. Since the cable is grounded at both ends, .

The impedance parameters in the formula are defined as follows:

Here, Zaa, Zss, and Zcc represent the self-impedances of the armor, sheath, and core wire, respectively, while the remaining terms denote the mutual impedances among the three components.

By substituting Equation (25) into the system of equations represented by Equation (24) and integrating it with Equation (23), one can solve for the induced currents İs and İa in the metal sheath and armor across each phase of the three-phase cable.

2.2.4. Loss Expression, Current-Carrying Capacity Calculation Process and Results

The IEC60287 standard outlines the calculation formula for the losses associated with metal sheaths under typical laying conditions (26):

However, the loss factors λ1 and λ2 specific calculation methods for the metal sheath and armor layers must be expressed as a ratio relative to the conductor losses, as indicated in Equation (27). By integrating the induced currents of the metal sheath İs and armor İa, as derived from Equations (23) and (26), one can ascertain the loss factors λ1 and λ2.

According to the cable current-carrying capacity calculation formula presented in Equation (13), and utilizing Equation (27) for correction, the formula for determining the current-carrying capacity of a cable, with both ends connected underground, is given in equation:

Here, represents the insulating dielectric loss of the primary insulating material of the cable, while U1 denotes the voltage difference between the cable core conductor and the metal sheath layer. The dielectric loss associated with the insulation of other layers corresponds to the voltage U2 difference between the metal sheath layer and the armor layer. Additionally, C2 and represent the capacitance parameters of the respective layers and the loss factor of the insulating medium.

2.3. Segmented Solid Bonding

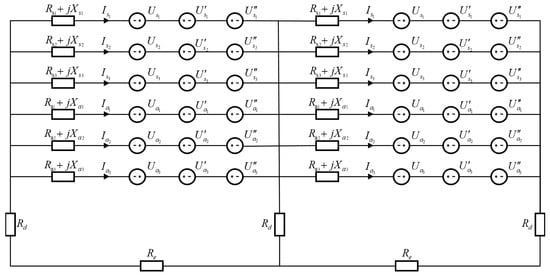

When the induced voltage generated under two-end solid bonding exceeds the insulation voltage withstand level of the sheath, it is advisable to employ the segmented solid bonding method. The equivalent circuit diagram is presented in Figure 4, and the calculation method aligns with that described in Section 2.2.

Figure 4.

Equivalent circuit of the segmented solid bonding grounding mode.

2.4. Using Semiconductive Outer Sheath

The grounding method known as segmented solid bonding affects the waterproof protection of cable lines due to the short-circuiting of multiple sections. Consequently, for longer lines, it is advisable to employ the grounding method that utilizes a semiconductive outer sheath. The resistance of this semiconductive outer sheath is situated between the insulating layer and the metal sheath, which influences both the voltage and current present on the outer sheath. Therefore, it is essential to derive separate current-carrying capacity calculation formulas for instances where the semiconductive outer sheath functions as either the conductor layer or the dielectric layer, thereby enhancing the accuracy of the corrected formulas.

When the semiconductive sheath serves as the conductor layer, the outer sheath connects in parallel with the metal sheath and armor layer. In this case, the calculation method aligns with the process outlined in Section 2.2 of this chapter. The induced voltage Ug and induced current Ig between the semiconductive outer sheath and the metal sheath and armor layer are calculated, resulting in an increased loss factor. The calculation formula is:

At this stage, the formula for calculating the current-carrying capacity of the cable will be revised from Equation (28) to Equation (30):

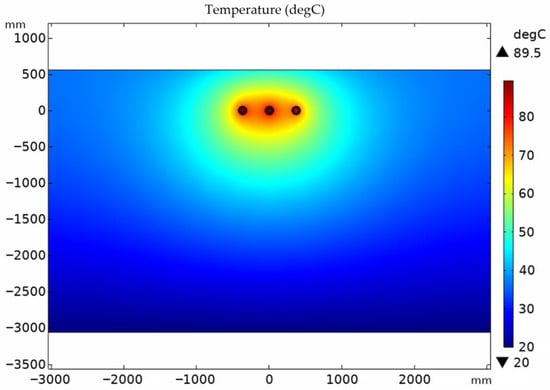

When a semiconductive sheath serves as the dielectric layer, the semiconductive outer sheath in the circuit behaves as a parallel connection of its lateral resistance and capacitance. Consequently, the leakage current within the semiconductive sheath is the aggregate of the capacitance and conductance currents. The equivalent circuit, with the semiconductive sheath functioning as the dielectric layer, is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Equivalent model of cable circuit with semiconductive outer sheath.

As illustrated in the equivalent circuit, the methods for calculating the lateral resistance and capacitance of the semiconductive sheath follow the same principles as outlined in Equation (25). However, based on Equations (22) and (23), determining the current-carrying capacity of the cable using Equation (30) necessitates solving for the voltage between the metal sheath and the armor. The calculation equation is:

Here, L denotes the cable length, while ra and rs signify the effective diameters of the armor layer and the metal sheath, respectively.

By substituting Equation (31) into Equation (28) during the calculation process, one can determine both the induced current and the current-carrying capacity of the cable.

3. Calculation, Analysis and Verification of the Electro-Thermal Field of Cable

3.1. Computational Analysis

After establishing equivalent circuits for different grounding methods of cables, calculating various losses and induced currents and potentials of the metal sheath and armor layer under different grounding methods, and correcting the calculation formula of the electro-thermal field of the cable, the YJLW03-Z 64/110 1 × 1200 mm2-shaped high-voltage single-core power cable was selected as the main research object. The electro-thermal field of the cable was calculated, analyzed, and verified. Establish a cable calculation model. Select a cable burial depth of 500 mm, a cable outer surface spacing of 250 mm, and take the soil at the burial site at 20 °C. The configuration assumed was direct burial with a three-phase arrangement.

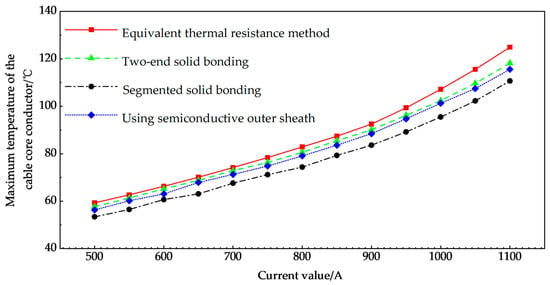

Set the core current values of the cable to 500 A, 550 A, 600 A, 650 A, 700 A, 750 A, 800 A, 850 A, 900 A, 950 A, 1000 A, 1050 A and 1100 A, respectively. The cable core temperatures were calculated and compared with simulation results under three grounding modes: two-end solid bonding, segmented solid bonding (with two intermediate short-circuit points), and semiconductive outer sheath. The results are shown in Table 1 and Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Table 1.

Numerical data of calculation results of cable core temperature with same current input.

Figure 6.

Calculation results of cable core temperature with same current input.

Figure 7.

Temperature difference of cable core with same current input.

As illustrated in Table 1, Figure 6 and Figure 7, when an identical current value is applied to the cable core, the temperature of the cable core exhibits varying degrees of change depending on the grounding method employed. However, these differences remain within the theoretical support range, thereby confirming the accuracy of the algorithm. The observed variations arise from the correction and calculation of diverse loss parameters associated with the metal sheath and armor, as detailed in Section 2.2, Section 2.3 and Section 2.4 of the preceding text, rather than applying uniform parameters as done in the equivalent thermal resistance method outlined in the original IEC60287. Furthermore, the temperature of the cable core conductor, under different grounding methods, is consistently lower compared to the equivalent thermal resistance method. Figure 6 demonstrates that, when the same current value is injected, the temperature of the middle section of the short-circuited cable core is the lowest among the three grounding methods that involve interconnection and grounding at both ends. Cable core temperature: When short-circuited in the middle section using a semiconductive electrical sheath, there is no short-circuiting in the middle. Furthermore, the temperature difference between the cable core with a semiconductive electrical sheath and the method without short-circuiting in the middle is relatively minor. This is primarily because the electrical conductivity of the semiconductive outer sheath material cannot be excessively high. Consequently, the reduction in total loss when employing a semiconductive outer sheath is not significantly different from that of the non-short-circuiting method in the middle. In contrast, when utilizing a segmented short-circuiting method in the middle (involving two short circuits), the reduction in total loss is substantial. Further discussions will be presented in Section 4.1, Section 4.2 and Section 4.3.

3.2. Finite Element Method (FEM) Simulation Validation

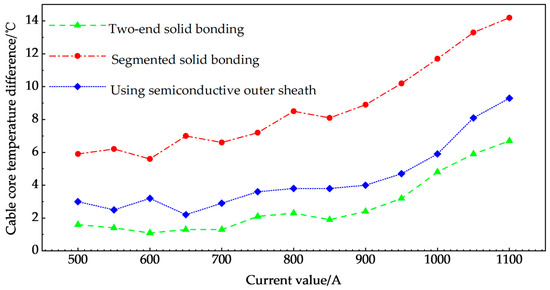

Finite Element Method (FEM) is a widely used and effective numerical technique for solving coupled electromagnetic and thermal problems. To validate the model in the two-end solid bonding configuration, a simulation was conducted using COMSOL Multiphysics 6.3 software. A 2D model was established with a burial depth of 500 mm and a cable outer surface spacing of 250 mm. The surrounding soil was set at 20 °C, with a thermal conductivity of 1 W/m·K, which is a typical value of thermal conductivity of moist soil [29,30]. According to the equivalent thermal resistance method, the calculated current-carrying capacity is 875.8 A, and the value obtained from the equivalent model is 897.6 A. FEM simulation results show that when the current-carrying capacity is set to 897.6 A, the cable core conductor temperature reaches 89.5 °C. The output results of the simulation are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Temperature field distribution obtained by FEM simulation for a current-carrying capacity of 897.6 A.

This FEM simulation validates that the equivalent model proposed in this study provides more accurate results compared to the equivalent thermal resistance method.

3.3. Experimental Verification

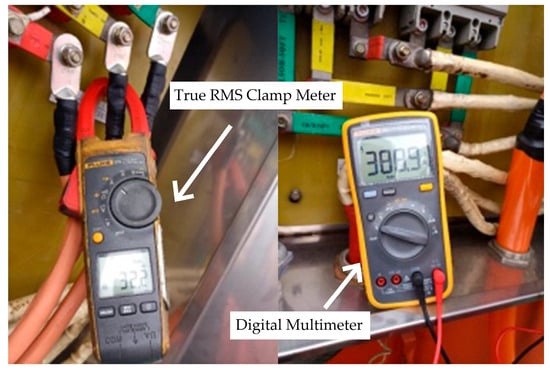

To validate the accuracy of the cable electro-thermal field calculation model that accounts for the grounding method, field measurements and inspections were conducted in Zhoushan, Zhejiang Province. The cable model selected for this study was the YJLW03-Z 64/110 1 × 1200 mm2 high-voltage single-core power cable, employing the segmented solid bonding method with two intermediate grounding points. The on-site measurement diagram is presented in Figure 9. A comparison of the test data and the calculated data is provided in Table 2.

Figure 9.

On-site measurement instrumentation.

Table 2.

Comparison table of measured data.

The core temperature was measured using a fiber optic sensor (Keyence, Shanghai, China), which was placed within the armor layer of the cable, close to the core. This positioning allowed for accurate measurement of the core temperature while avoiding direct contact with the conductor. The fiber optic sensor was chosen for its high precision and ability to operate in the harsh environment of high-voltage cables. The load current was monitored, and an effective current of 936.1 A was maintained. Data recording was conducted after the cable core temperature stabilized, ensuring the measured value of 89.6 °C represents the steady-state thermal condition.

The comparison between on-site measurement data and the results from the cable electro-thermal field correction model, which accounts for the grounding method, reveals a temperature difference of 2.7 °C in the cable core, corresponding to a calculation error of 3.01%. Additionally, the difference in current-carrying capacity is 15.7 A, with a calculation error of 1.68%. The analysis of the on-site test data indicates that the results derived from the electro-thermal field correction calculation model are both reliable and effective.

4. Analysis of Influencing Factors of Cable Current-Carrying Capacity Under Different Grounding Methods

4.1. Two-End Solid Bonding

When well grounded, the grounding resistance may be reduced to zero (RD = 0). The burial depth is 500 mm, the distance between the outer surfaces of the cables is 250 mm, and the soil temperature at the burial site is 20 °C. The thermal conductivity of the soil is 1 W/m·K [29,30]. According to the equivalent model, the calculated current-carrying capacity is 897.6 A, with a total loss of 1.25. Utilizing the recommended algorithm from IEC 60287-1-1:2006, the current-carrying capacity is determined to be 875.8 A, corresponding to λ = 1.36. Under the two-end solid bonding mode, the calculated current-carrying capacity is 21.3 A higher, resulting in a calculation error of 2.43%.

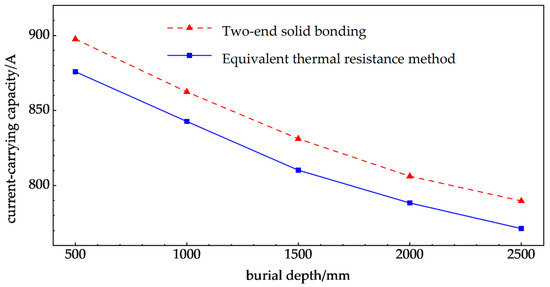

The burial depths were set at 500 mm, 1000 mm, 1500 mm, 2000 mm, and 2500 mm. The ampacity was calculated under the two-end solid bonding mode and using the equivalent thermal resistance method. The variation in ampacity with laying depth and the comparison of results between the two methods are presented in Table 3 and Figure 10.

Table 3.

Numerical data of cable rating under different burying depth.

Figure 10.

Cable rating under different burying depth.

The trends observed in the results derived from the equivalent thermal resistance method and the current-carrying capacity correction formula are consistent. Specifically, the current-carrying capacity diminishes as burial depth increases, with the rate of decrease itself also declining. Furthermore, the discrepancies between the two methods at various burial depths are 2.43%, 2.29%, 2.51%, 2.21%, and 2.33%, respectively.

These results provide a more detailed comparison with the classic IEC 60287 method under different laying depths. For burial depths ranging from 0.5 m to 2.5 m, the difference between the proposed grounding-mode correction model and the IEC 60287 calculation remains within approximately 2–3%. This indicates that the modified model is consistent with the standard method in terms of ampacity evaluation, while the small deviations are mainly due to the more explicit treatment of sheath and armor losses in the proposed approach.

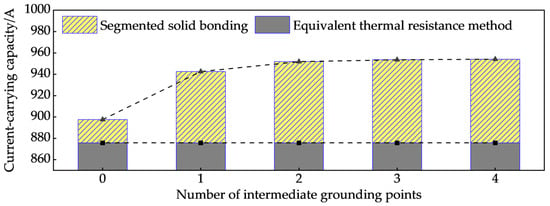

4.2. Segmented Solid Bonding

Using the modified current-carrying capacity calculation formula from Equation (28), we calculated the metal sheath loss, armor loss, and current-carrying capacity under conditions of one, two, three, and four short-circuits, as well as in the absence of short-circuiting. The results are presented in Table 4 and Figure 11.

Table 4.

Power Losses and Rating Corresponding to Connection Times.

Figure 11.

Variation in ampacity with the number of intermediate grounding points.

Compared with the equivalent thermal resistance method defined in IEC 60287, the proposed method explicitly accounts for the redistribution of induced currents caused by segmented solid bonding. Since the IEC method does not include this effect, its calculated ampacity remains unchanged regardless of the number of intermediate grounding points. In contrast, the proposed model shows that introducing segmented solid bonding progressively reduces sheath circulating current and therefore decreases sheath losses. As shown in Table 4, the metal sheath loss decreases from 13.93 W·m−1 (under two-end solid bonding) to 4.06 W·m−1 (with four intermediate grounding points). This reduction directly contributes to the improvement in current-carrying capacity.

At the same time, the armor loss exhibits a slight increase with additional intermediate grounding points. This occurs because part of the induced current previously confined to the sheath is redistributed into the armor when the segmented solid bonding alters the grounding path. However, this increase is relatively small compared with the reduction in sheath loss and does not offset the improvement in ampacity.

As illustrated in Figure 11, the current-carrying capacity rises from 897.6 A under two-end solid bonding to 954.1 A with four intermediate grounding points. The growth becomes less pronounced as the number of intermediate grounding points increases, indicating a point of diminishing returns. Beyond three or four grounding sections, the circulating current in the sheath becomes sufficiently suppressed, and the improvement in ampacity converges toward a stable value.

Overall, this section demonstrates that the main difference between the proposed approach and the traditional equivalent thermal resistance method lies in the treatment of sheath and armor losses under different grounding configurations. The IEC 60287 method cannot reflect the effect of segmented solid bonding, whereas the proposed model captures how grounding mode changes the distribution of induced currents and consequently alters the loss composition and ampacity. This distinction allows the proposed model to provide a more accurate evaluation of current-carrying capacity under practical grounding arrangements.

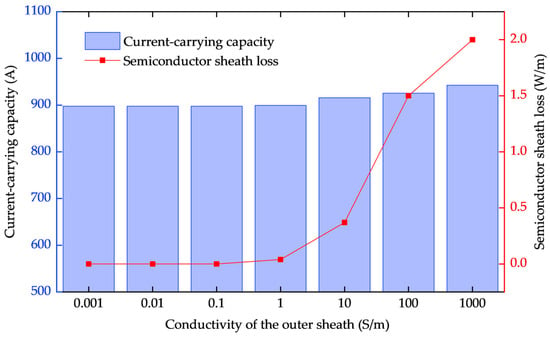

4.3. Using Semiconductive Outer Sheath

When the two ends of the cable are interconnected and grounded, and a semiconductive outer sheath is employed, the conductivity of the outer sheath is taken as 10 S/m, representing a typical effective value within the semi-conductive transition region of carbon black filled polymers. Based on the current-carrying capacity correction model, the losses of the metal sheath, armor, and semiconductive coating, as well as the resulting ampacity, are calculated for configurations with and without the semiconductive outer sheath. The results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Power Losses and Rating with and without Semiconductive Outer Sheath.

The addition of the semiconductive outer sheath results in a reduction in metal sheath loss from 13.93 W·m−1 to 9.5 W·m−1, and a slight increase in armor loss from 4.86 W·m−1 to 5.34 W·m−1. The semiconductor sheath itself contributes a small loss of 0.37 W·m−1, while the current-carrying capacity increases from 897.6 A to 915.8 A, indicating a modest improvement in the overall performance due to the use of the semiconductive outer sheath.

In Figure 12, we present the results of a sensitivity analysis showing the impact of varying the conductivity of the semiconductive outer sheath on both the current-carrying capacity and semiconductor sheath loss. As the conductivity increases from 0.001 S/m to 1000 S/m, the current-carrying capacity shows a noticeable improvement, reaching 915.8 A at 10 S/m and further increasing to 942.6 A at 1000 S/m. This demonstrates that higher conductivity values lead to an increase in the current-carrying capacity, though the effect diminishes beyond a certain point. Conversely, the semiconductor sheath loss also increases as the conductivity rises, with the loss reaching 2 W/m at 1000 S/m. However, the loss remains relatively modest compared to the overall current-carrying capacity increase. This suggests that while the semiconductive outer sheath enhances ampacity at higher conductivities, the impact on losses is not as significant.

Figure 12.

Variation in current-carrying capacity and semiconductor sheath loss with conductivity of the outer sheath.

Overall, the results demonstrate that the improved method for calculating current-carrying capacity is highly effective. The semiconductive outer sheath enhances the cable’s current-carrying capacity, particularly at higher conductivity values, while the increase in semiconductor sheath loss remains relatively small.

5. Conclusions

This paper examines the calculation of current-carrying capacity for high-voltage single-core power cables under various grounding methods. It develops equivalent circuit models for three typical grounding approaches: two-end solid bonding, segmented solid bonding, and the use of a semiconductive outer sheath. Based on these models, it revises the equivalent thermal resistance calculation method outlined in the IEC 60287 standard. Through theoretical derivation, numerical calculations, and field verification, the following conclusions have been reached:

- A unified equivalent circuit model for grounding modes has been established. By incorporating the electromagnetic coupling between the metal sheath and armor, expressions for induced voltage and induced current corresponding to different grounding configurations were derived. This provides a consistent theoretical framework for analyzing how grounding modes affect cable thermal behavior.

- The modified model demonstrates high engineering accuracy. For the YJLW03-Z 64/110 1 × 1200 mm2 cable, the difference between the calculated and measured core temperature is only 3.01%, and the ampacity error is 1.68% under typical laying conditions. These results indicate that the model is sufficiently precise for engineering applications such as ampacity verification and thermal evaluation.

- Grounding configuration has a quantifiable impact on loss distribution and ampacity. Transitioning from two-end solid bonding to segmented solid bonding reduces sheath losses from 13.93 W·m−1 to 4.06 W·m−1, and increases the ampacity from 897.6 A to 954.1 A, representing an improvement of approximately 6%. When the number of grounding sections exceeds two, the marginal increase in ampacity becomes small. The semiconductive outer sheath offers limited ampacity enhancement but contributes to improved electric field uniformity and thermal stability.

In conclusion, the grounding mode correction model developed in this study offers a valuable reference for the optimal design of grounding configurations, verification of current-carrying capacity, and assessment of the operational status of high-voltage cable lines. Furthermore, it holds significant engineering implications for enhancing the safety and cost-effectiveness of cable system operations. Future research will focus on incorporating temperature-dependent resistivity and soil thermal conductivity, as well as conducting more extensive validation through comparisons with FEM-based numerical simulations under various cable geometries and installation conditions, to further enhance the accuracy and robustness of the model.

Author Contributions

Q.S. conceived and supervised the study. S.F. and Z.Z. collected and analyzed the data. F.L. and Z.F. developed the weighting and evaluation models. J.L. provided technical support. P.L. conducted result validation and comparative analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Scientific and Technical Funds of Sichuan Electric Power Corporation, The Rapid Isolation and Transfer Technology for Single-Phase Ground Faults in Cable Lines, grant number 52199723002N.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Qianqiu Shao, Songhai Fan, Zongxi Zhang, Fenglian Liu, Zhengzheng Fu and Pinlei Lv were employed by the company State Grid Sichuan Electric Power Company Electric Power Science Research Institute. Author Jinkui Lu was employed by the company State Grid Sichuan Electric Power Company. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Zheng, Z.; Tang, M.; Wu, L.-S.; Qiu, L.-F.; Mao, J. Efficient Electro-Thermal Analysis of SIW Filters Considering Temperature-Dependent Characteristics of Materials. IEEE Trans. Compon., Packag. Manufact. Technol. 2024, 14, 1079–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczegielniak, T.; Jabłoński, P.; Kusiak, D. Analytical Approach to Current Rating of Three-Phase Power Cable with Round Conductors. Energies 2023, 16, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enescu, D.; Colella, P.; Russo, A.; Porumb, R.F.; Seritan, G.C. Concepts and Methods to Assess the Dynamic Thermal Rating of Underground Power Cables. Energies 2021, 14, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Meng, Z.; Song, P.; Zhu, M.; Li, X.; Du, B. Breakdown Performance Evaluation and Lifetime Prediction of XLPE Insulation in HVAC Cables. Energies 2024, 17, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, Y. Electrothermal Coupling Analysis of Submarine Cables. Ships Offshore Struct. 2025, 20, 1496–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierotti, G.; Popoli, A.; Ragazzi, F.; Diban, B.; Cristofolini, A.; Mazzanti, G. FEVER—Fem Electrothermal solVER: Application to an HVDC Joint. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2023 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC/I&CPS Europe), Madrid, Spain, 6–9 June 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Neher, J.H.; McGrath, M.H. The Calculation of the Temperature Rise and Load Capability of Cable Systems. Trans. Am. Inst. Electr. Eng. Part III Power Appar. Syst. 1957, 76, 752–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electrical Power Cable Engineering; Thue, W.A., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-315-21719-2. [Google Scholar]

- Petrović, G.; Cvetković, M.; Garma, T.; Kilić, T. An Approach to Thermal Modeling of Power Cables Installed in Ducts. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 214, 108916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Chen, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, X. Study on the Effect of Cable Group Laying Mode on Temperature Field Distribution and Cable Ampacity. Energies 2019, 12, 3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.X.; Kong, X.X.; Cui, B.; Li, J. Improved Ampacity of Buried HVDC Cable with High Thermal Conductivity LDPE/BN Insulation. IEEE Trans. Dielect. Electr. Insul. 2017, 24, 2667–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rerak, M.; Ocłoń, P. The Effect of Soil and Cable Backfill Thermal Conductivity on the Temperature Distribution in Underground Cable System. E3S Web Conf. 2017, 13, 02004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; He, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, F.; He, T.; Liu, L.; Wang, S.; Liu, H. Temperature Analysis Based on Multi-Coupling Field and Ampacity Optimization Calculation of Shore Power Cable Considering Tide Effect. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 119785–119794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Fu, Q.; Chen, L.; Xu, T. Research on Multi-Physical Field Coupling of Solid Electrothermal Storage Unit. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 775–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Hu, M.; Luo, L. Calculation of Thermal Distribution and Ampacity for Underground Power Cable System by Using Electromagnetic-Thermal Coupled Model. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Electrical Insulation Conference (EIC), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 8–11 June 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 303–306. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Xu, Z.; Ma, H.; Hao, Y.; Wang, P.; Wu, W.; Xie, Y.; Guo, D. An Improved Analytical Thermal Rating Method for Cables Installed in Short-Conduits. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 123, 106223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, Z.; Qi, M. Fast Calculation Method of Directly Buried Cables Ampacity. Vib. Proced. 2021, 38, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakelmann, H.; Anders, G.J. Ampacity Calculations of Underground Power Cables with End Effects. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 1968–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Liang, Y.; Fu, C.; Cheng, Y. Rapid Calculation Model for Transient Temperature Rise of Complex Direct Buried Cable Cores. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candela, R.; Gattuso, A.; Mitolo, M.; Sanseverino, E.R.; Zizzo, G. A Model for Assessing the Magnitude and Distribution of Sheath Currents in Medium and High-Voltage Cable Lines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Applicat. 2020, 56, 6250–6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, G.C.; Yanagihara, J.I. Prediction of the Temperature Distribution of Partially Submersed Umbilical Cables. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2012, 34, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jin, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, B.; Ma, X.; Ji, K. Study on Finite Element Analysis of the External Heat Resistance of Cables in Ductbank. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Xiao, J.; Hou, J.; Gao, J.; Zhong, L. Technical and Economic Demands of HVDC Submarine Cable Technology for Global Energy Interconnection. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2020, 3, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, P.J.; Uva, M.A.; Nowlin, J. Naval Ship-to-Shore High Temperature Superconducting Power Transmission Cable Feasibility. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2011, 21, 984–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yu, J.; Yu, L.; Zhou, H. Numerical Analysis of Thermo-Electric Field for AC XLPE Cable in DC Operation Based on Conduction Current Measurement. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 8226–8234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Hao, Y.; Deng, J.; Zhang, G. Analysis of Current Carrying Capacity and Temperature Field of Power Cables under Different Laying Modes. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on High Voltage Engineering and Application (ICHVE), Beijing, China, 6–10 September 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gouda, O.E.; Osman, G.F.A. Enhancement of the Thermal Analysis of Power Cables Installed in Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) Ducts under Continuous and Cyclic Current Loading Conditions. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2021, 15, 1144–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enescu, D.; Colella, P.; Russo, A. Thermal Assessment of Power Cables and Impacts on Cable Current Rating: An Overview. Energies 2020, 13, 5319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 60287-3-1-2017 RLV; Electric Cables—Calculation of the Current Rating—Part 3-1: Operating Conditions—Site Reference Conditions. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Georgiev, D.; Georgiev, G.; Rangelov, Y.; Kamenov, Y. Analysis of the Effect of Soil Thermal Resistivity on High-Voltage Cables Sizing. In Proceedings of the 2020 21st International Symposium on Electrical Apparatus & Technologies (SIELA), Bourgas, Bulgaria, 3–6 June 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).