Probabilistic Resilience Enhancement of Active Distribution Networks Against Wildfires Using Hybrid Energy Storage Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Modeling the spatio-temporal probability distribution of wildfire occurrence.

- Modeling the impact of wildfire on distribution lines, DERs, and ESSs.

- Probabilistically evaluating and enhancing the resilience of ADNs against wildfires by utilizing HESSs.

2. Methodology

2.1. Probabilistic Spatio-Temporal Simulation of Wildfire Occurrence

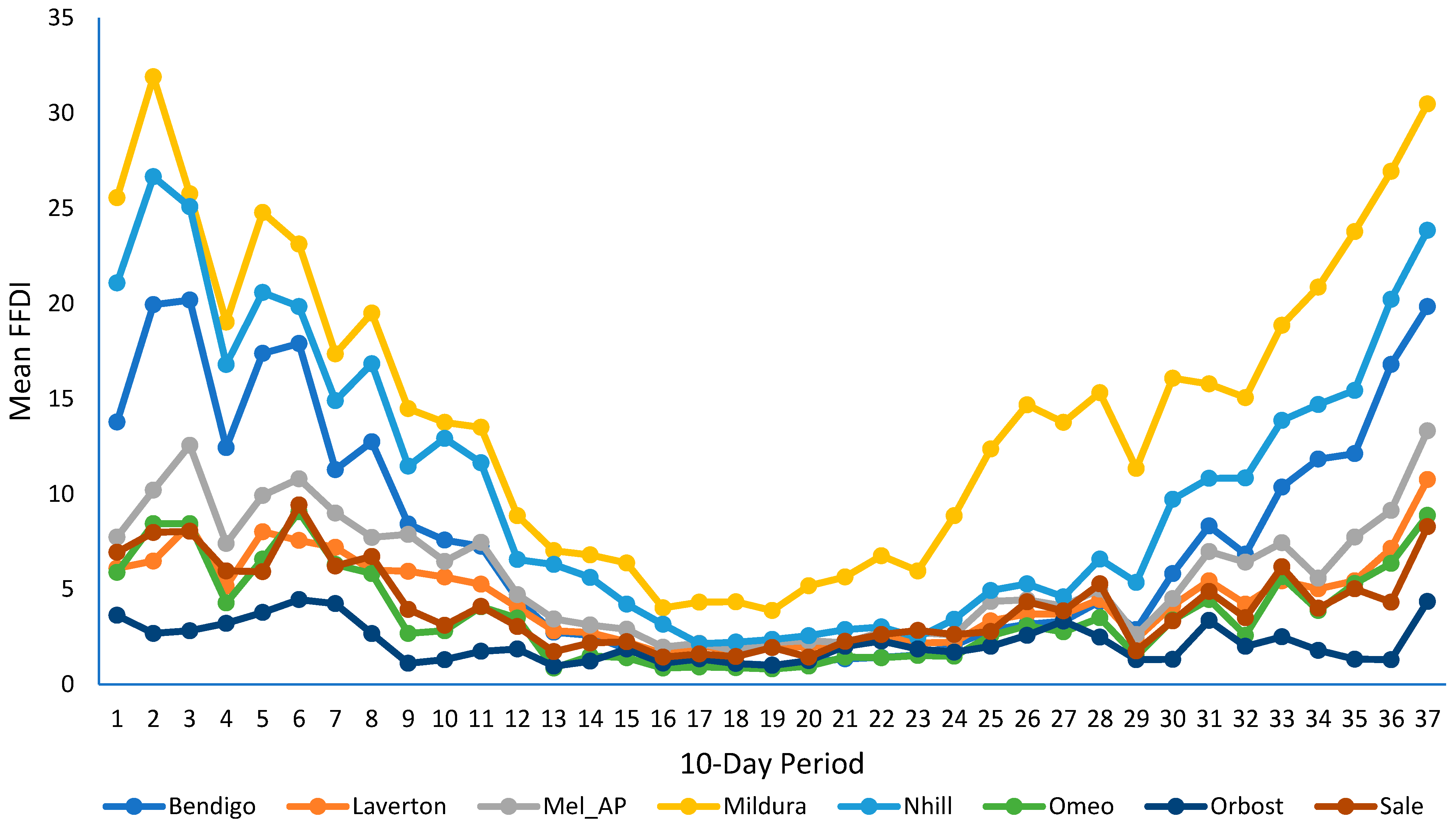

- The historical daily FFDI data for different geospatial locations, each associated with a distinct ADN, are collected. For instance, in this work, the daily FFDI data for eight different locations, with an ADN for each location, in Victoria, Australia for the last five years (2019–2023) has been obtained from Bureau of meteorology (BOM) of Australia [24]. These eight locations include Bendigo, Laverton, Melbourne Airport (Mel_AP), Mildura, Nhill, Omeo, Orbost, and Sale.

- As discussed in [25,26], power outages caused by wildfire events have been reported to last up to 10 days. Therefore, a 10-day duration is selected in this study to evaluate the impact of a single wildfire ignition. Accordingly, each year of historical data is divided into 10-day periods including 36 intervals of 10-day periods and one interval of remaining five/six days of a year (totally, 37 intervals). However, the proposed method has no limitation in this regard and can work with other time windows (other than the 10-day period) as well.

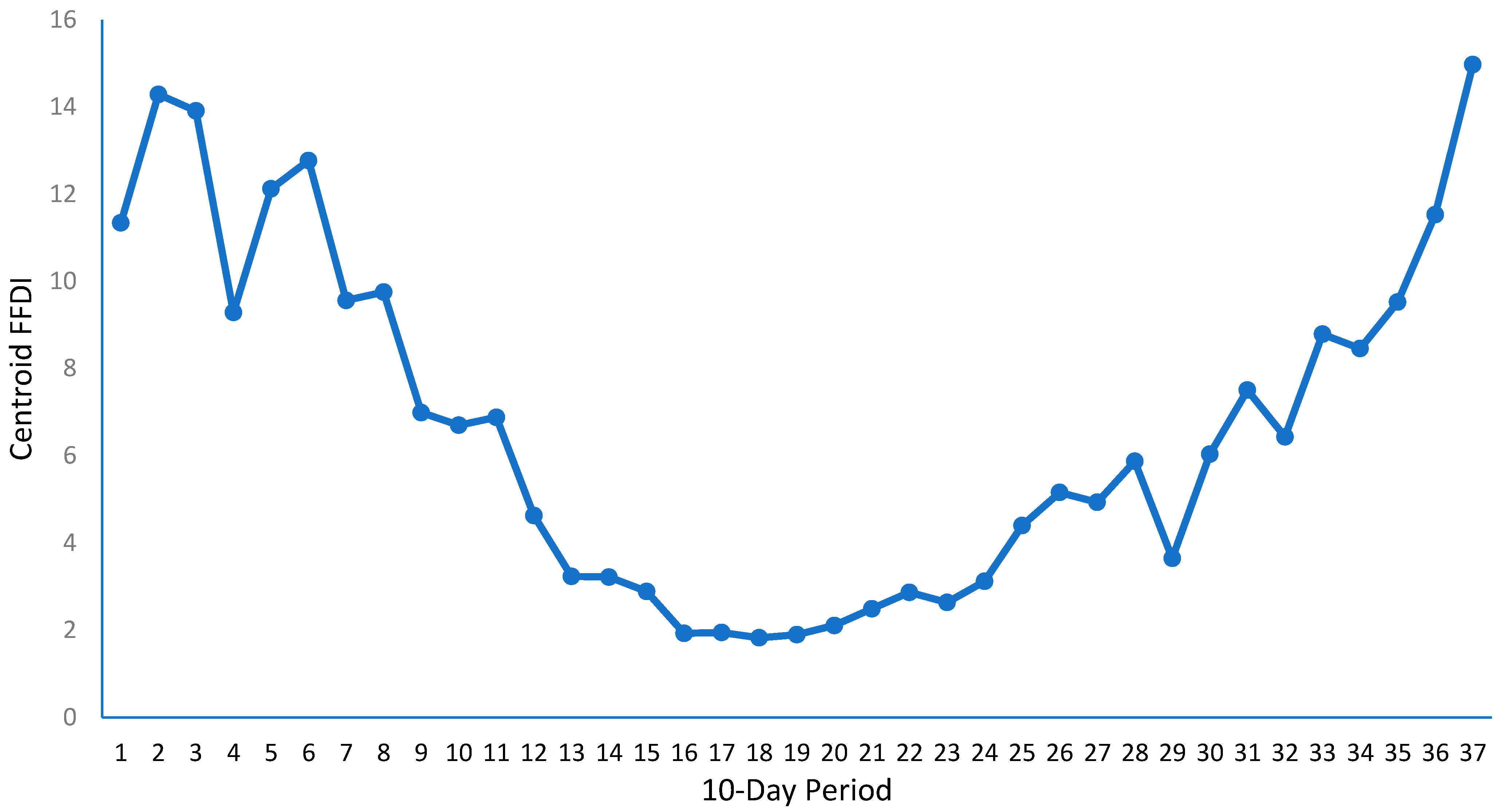

- The spatial-centroid time series of this temporal-mean FFDI data across all locations is calculated. For example, Figure 2 shows the spatial-centroid time series calculated for the temporal-mean FFDI data of the eight locations of Figure 1. The time series in Figure 2 shows the spatio-temporal average of all historical FFDI data.

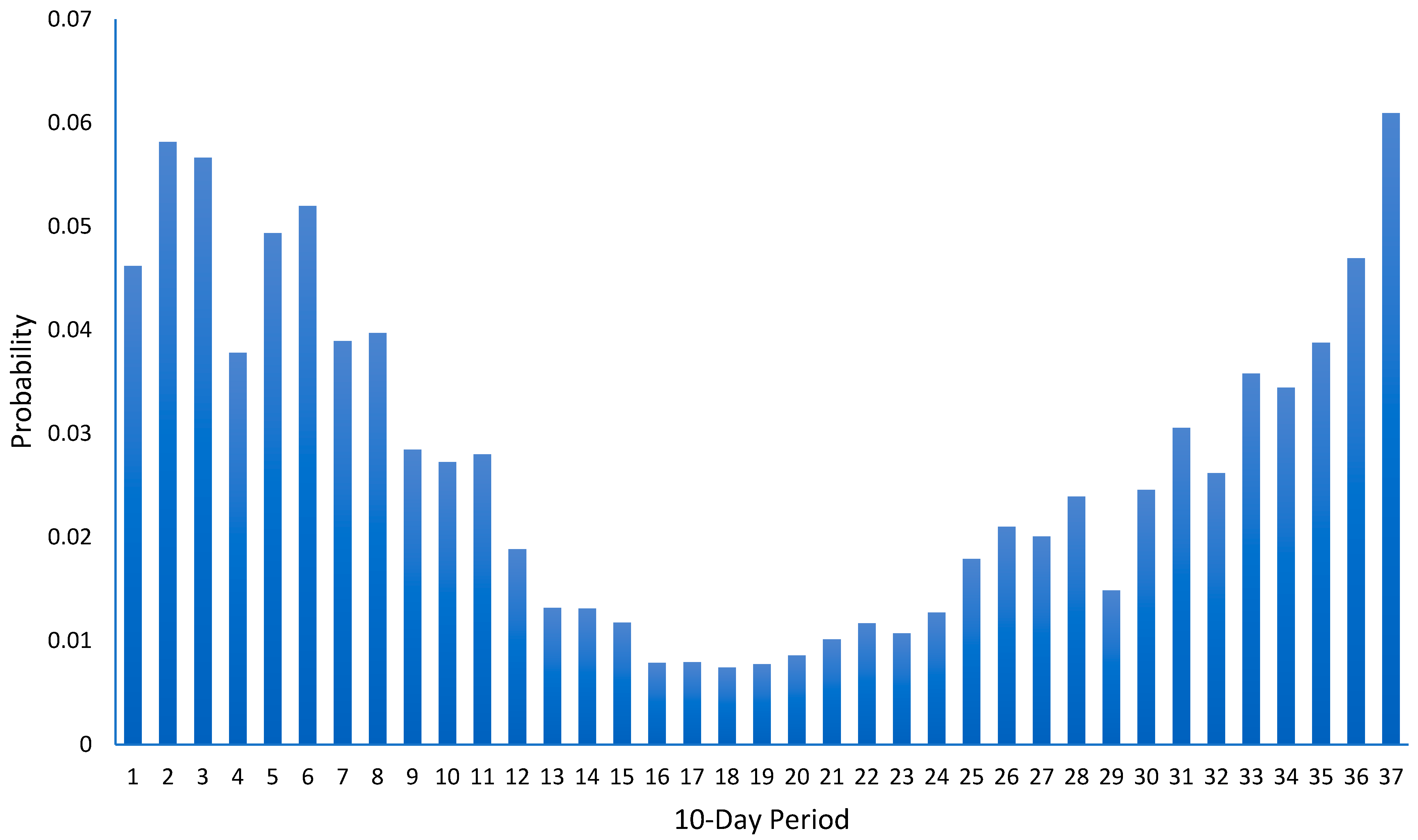

- Non-parametric probability distribution function is constructed using the spatio-temporal average time series obtained in the previous step (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows this non-parametric probability distribution across 37 time intervals, calculated from the spatio-temporal average FFDI time series presented in Figure 2. Figure 3 shows that the 10-day periods in January, February, March, and December (summer season in the Southern Hemisphere) exhibit higher fire danger probabilities than the other intervals.

- In the spatio-temporal probability distribution obtained in the previous step (such as the spatio-temporal probability distribution in Table 2), the summation of probabilities of each row is 1. However, to make a normalized spatio-temporal probability distribution for fire danger risk, the spatial probabilities of different locations in each row are multiplied by the temporal probability of the associated time interval (such as temporal probabilities shown in Figure 3). For example, the eight spatial probabilities of the first row in Table 2 are multiplied by the temporal probability of the first 10-day period (which is 0.046166609 taken from Figure 3). This is similarly repeated for the next rows of Table 2. The result is shown in Table 3. The summation of all 37 × 8 normalized spatio-temporal probabilities of Table 3 is one. The normalized spatio-temporal probability distribution of Table 3 clearly reflects the variation in wildfire danger risk across different time periods and geospatial locations.

2.2. Modeling Wildfire Impacts on Overhead Lines, DERs and ESSs

2.3. Optimal Power Flow and Resilience Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

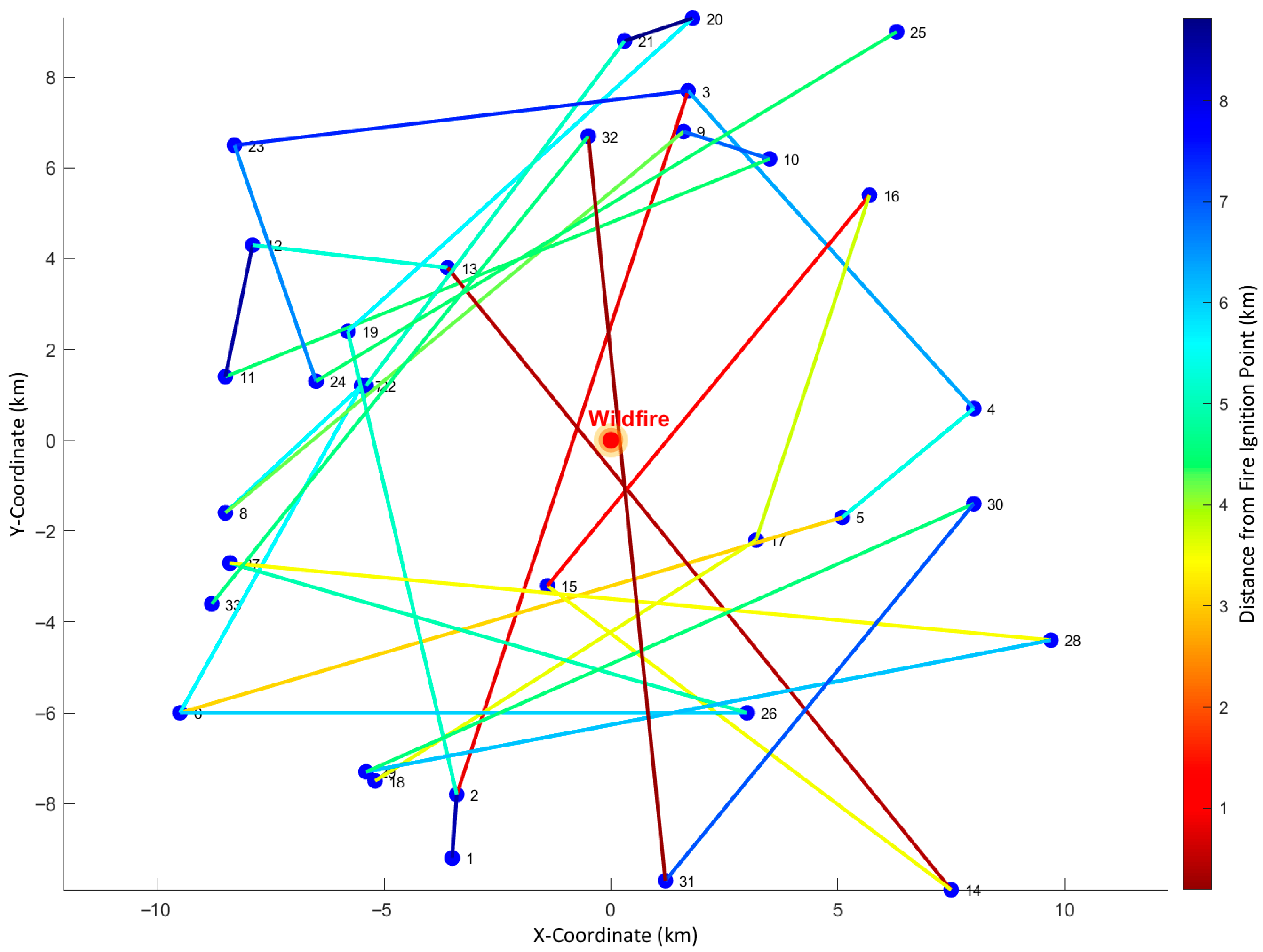

- Wildfires can significantly impact ADNs by disconnecting lines, DERs, and ESSs, with the disconnection time of each component depending on its distance from the wildfire and the propagation dynamics.

- Different locations in an ADN and different time intervals in a year can have significantly different wildfire risks. This justifies the proposed probabilistic spatio-temporal simulation model, which generates different wildfire scenarios along with their associated probabilities.

- HESSs can be effective in enhancing the resilience of an ADN against wildfires and farther HESSs from the wildfire ignition point can be more effective (e.g., 19.40% resilience enhancement in the case with the farthest distances between the wildfire ignition point and HESSs versus 4.16% resilience enhancement in the case with the closest distances, as demonstrated in the numerical experiments of the paper). This finding offers a practical recommendation for power system planners to install ESSs as far as possible from potential fire ignition points to maximize their contribution to resilience enhancement.

- Deterministic approaches, by ignoring the probabilistic nature of wildfire occurrences, can significantly overestimate the EENS. For example, the deterministic method that assumes a single wildfire affecting all areas produced overestimation errors of 54.09–59.47%, whereas the deterministic method that assumes one wildfire per area resulted in substantially larger overestimations of 585.48–608.42%. This underscores the importance of the proposed probabilistic modeling.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shah, R.; Amjady, N.; Shakhawat, N.S.B.; Aslam, M.U.; Miah, M.S. Wildfire Impacts on Security of Electric Power Systems: A Survey of Risk Identification and Mitigation Approaches. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 173047–173065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, S. California Outages Exceed 425,000 as Wildfires Continue to Blaze. Available online: https://www.renewableenergyworld.com/power-grid/outage-management/california-outages-exceed-425000-as-wildfires-continue-to-blaze/ (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Aslam, M.U.; Miah, M.S.; Amin, B.M.R.; Shah, R.; Amjady, N. Application of Energy Storage Systems to Enhance Power System Resilience: A Critical Review. Energies 2025, 18, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, M.; Hosseinian, S.H.; Dehghan, S.; Fakharian, A.; Amjady, N. A critical review on definitions, indices, and uncertainty characterization in resiliency-oriented operation of power systems. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2021, 31, e12680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi, S.; Zhao, J.; Pierre, B.; Lei, F.; Anagnostou, E.; He, K.; Jones, C.; Wang, B. Wildfire and power grid nexus in a changing climate. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 2025, 2, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, S.U.; Majumder, S.; Srivastava, A.K.; Chhokra, A.D.; Neema, H.; Dubey, A.; Laszka, A. Reinforcement-Learning-Based Proactive Control for Enabling Power Grid Resilience to Wildfire. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Rhodes, N.; Yang, H.; Roald, L.; Ntaimo, L. Multi-Period Power System Risk Minimization Under Wildfire Disruptions. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 6305–6318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, B.; Arabnya, A.; Thompson, M.P.; Khodaei, A. A Wildfire Progression Simulation and Risk-Rating Methodology for Power Grid Infrastructure. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 112144–112156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, A.A.; Abdeltawab, H.; Mohamed, Y.A.R.I. Safe Deep Reinforcement Learning for Resilient Self-Proactive Distribution Grids Against Wildfires. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025, 16, 5065–5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazemi, M.; Dehghanian, P.; Darestani, Y.; Su, J. Parameterized Wildfire Fragility Functions for Overhead Power Line Conductors. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 2517–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayani, R.; Manshadi, S.D. Resilient Expansion Planning of Electricity Grid Under Prolonged Wildfire Risk. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 3719–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Sparrow, S.N.; Ashtine, M.; Wallom, D.C.H.; Morstyn, T. Resilient by design: Preventing wildfires and blackouts with microgrids. Appl. Energy 2022, 313, 118793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, K.; Yao, Q.; Reszka, P. An interpretable machine learning model for predicting forest fire danger based on Bayesian optimization. Emerg. Manag. Sci. Technol. 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khastagir, A. Fire frequency analysis for different climatic stations in Victoria, Australia. Nat. Hazards 2018, 93, 787–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, C. On Developing a Historical Fire Weather Data-Set for Australia. Aust. Meteorol. Oceanogr. J. 2010, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, M.; Hossein Hosseinian, S.; Dehghan, S.; Fakharian, A.; Amjady, N. Resiliency-Oriented operation of distribution networks under unexpected wildfires using Multi-Horizon Information-Gap decision theory. Appl. Energy 2023, 334, 120536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, A.A.; Abdeltawab, H.; Mohamed, Y.A.R.I. Towards Resilient Self-Proactive Distribution Grids Against Wildfires: A Dual Rolling Horizon-Based Framework. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2025, 40, 2915–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazemi, M.; Dehghanian, P. Powering Through Wildfires: An Integrated Solution for Enhanced Safety and Resilience in Power Grids. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, 4192–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayani, R.; Manshadi, S. An Agile Mobilizing Framework for V2G-Enabled Electric Vehicles Under Wildfire Risk. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 5771–5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atawi, I.E.; Al-Shetwi, A.Q.; Magableh, A.M.; Albalawi, O.H. Recent Advances in Hybrid Energy Storage System Integrated Renewable Power Generation: Configuration, Control, Applications, and Future Directions. Batteries 2023, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.U.; Shakhawat, N.S.; Shah, R.; Amjady, N.; Miah, M.S.; Amin, B.M.R. Hybrid Energy Storage Modeling and Control for Power System Operation Studies: A Survey. Energies 2024, 17, 5976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; He, J.; Liao, Y. Cost Minimization of Battery-Supercapacitor Hybrid Energy Storage for Hourly Dispatching Wind-Solar Hybrid Power System. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 210099–210115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Shaaban, M.F.; Sindi, H.F. Optimal Operational Planning of RES and HESS in Smart Grids Considering Demand Response and DSTATCOM Functionality of the Interfacing Inverters. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government. Bureau of Meteorology. Climate Data Services. Available online: https://reg.bom.gov.au/climate/data-services/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Pham, T.N.; Shah, R.; Amjady, N.; Islam, S. Prediction of fire danger index using a new machine learning based method to enhance power system resiliency against wildfires. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2024, 18, 4008–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DEECA; AEMO; CSIRO. Bushfire Risk Affecting Electricity Distribution: Approaches to Determine Feasibility of Stand-Alone Power Systems. Electricity Sector Climate Information (ESCI) Project: Canberra, Australia, 2021. Available online: https://www.climatechangeinaustralia.gov.au/media/ccia/2.2/cms_page_media/732/ESCI%20Case%20Study%205_Bushfire%20risk%20to%20distribution%20120721.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- DEECA. DataShare. Available online: https://datashare.maps.vic.gov.au/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Karimi, S.; Musilek, P.; Knight, A.M. Dynamic thermal rating of transmission lines: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trakas, D.N.; Hatziargyriou, N.D. Optimal Distribution System Operation for Enhancing Resilience Against Wildfires. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 2260–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, J.L.; Simeoni, A.; Moretti, B.; Leroy-Cancellieri, V. An analytical model based on radiative heating for the determination of safety distances for wildland fires. Fire Saf. J. 2011, 46, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std 738-2023 (Revision of IEEE Std 738-2012); IEEE Standard for Calculating the Current-Temperature Relationship of Bare Overhead Conductors. IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–56. [CrossRef]

- Noyanbayev, N.K.; Forsyth, A.J.; Feehally, T. Efficiency analysis for a grid-connected battery energy storage system. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 22811–22818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhao, J. Security-constrained unit commitment model considering frequency and voltage stabilities with multiresource participation. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1437271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, D.S.; Misra, S. An operational scheduling framework for Electric Vehicle Battery Swapping Station under demand uncertainty. Energy 2024, 290, 130219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Besheer, A.H.; Emara, H.M.; Bahgat, A. Optimal micro-grid battery scheduling within a comprehensive smart pricing scheme. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bushfire Factsheet. Energy Network Australia: Australia, 2020. Available online: https://www.energynetworks.com.au/resources/fact-sheets/bushfire-factsheet-2020 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Evangelopoulos, V.A.; Georgilakis, P.S. Optimal distributed generation placement under uncertainties based on point estimate method embedded genetic algorithm. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2014, 8, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powercor. Network Data. Available online: https://www.powercor.com.au/network-planning-and-projects/network-data/ (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Zone Substation Information. Available online: https://www.jemena.com.au/electricity/jemena-electricity-network/network-information/zone-substation-information/ (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- AusNet. AusNet GridView. Available online: https://gridview.ausnetservices.com.au/# (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Chatuanramtharnghaka, B.; Deb, S.; Singh, K.R. Short—Term Load Forecasting for IEEE 33 Bus Test System using SARIMAX. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Industrial Electronics: Developments & Applications (ICIDeA), Imphal, India, 29–30 September 2023; pp. 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermawan, S.; Putranto, L.M.; Ali, H.R.; Saputra, F. Determination of PV Hosting Capacity on the 20 kV Distribution Network considering Network Configuration. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Smart-Green Technology in Electrical and Information Systems (ICSGTEIS), Badung, Bali, Indonesia, 2–4 November 2023; pp. 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Gong, Q. Optimal allocation of a hybrid energy storage system considering its dynamic operation characteristics for wind power applications in active distribution networks. Int. J. Energy Res. 2018, 42, 4184–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimizadeh, K.; Soleymani, S.; Faghihi, F. Optimal placement of DG units for the enhancement of MG networks performance using coalition game theory. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2020, 14, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generalized Algebraic Modeling Systems (GAMS). Available online: https://www.gams.com/ (accessed on 28 September 2025).

| FFDI | Fire Danger Rating |

|---|---|

| 0–11 | Low–Moderate |

| 12–31 | High |

| 32–49 | Very High |

| 50–74 | Severe |

| 75–99 | Extreme |

| 100+ | Catastrophic |

| Spatio-Temporal Wildfire Probability (Eight Locations vs. 37 Periods) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color Legend | Period | Bendigo | Laverton | Mel_AP | Mildura | Nhill | Omeo | Orbost | Sale |

| 0.39 | 1 | 0.151913 | 0.067247 | 0.085327 | 0.281777 | 0.232389 | 0.064822 | 0.040018 | 0.076508 |

| 0.38 | 2 | 0.174484 | 0.056703 | 0.089254 | 0.279139 | 0.233287 | 0.073854 | 0.023451 | 0.069828 |

| 0.37 | 3 | 0.181377 | 0.075319 | 0.112889 | 0.23153 | 0.225418 | 0.075858 | 0.025346 | 0.072263 |

| 0.36 | 4 | 0.167497 | 0.069476 | 0.099636 | 0.256093 | 0.226202 | 0.057628 | 0.043221 | 0.080248 |

| 0.35 | 5 | 0.179249 | 0.082715 | 0.10231 | 0.255569 | 0.212252 | 0.067863 | 0.038985 | 0.061056 |

| 0.34 | 6 | 0.175215 | 0.074002 | 0.105717 | 0.226312 | 0.194205 | 0.088684 | 0.043657 | 0.092208 |

| 0.33 | 7 | 0.147451 | 0.094118 | 0.117647 | 0.226928 | 0.194771 | 0.082353 | 0.055425 | 0.081307 |

| 0.31 | 8 | 0.163312 | 0.076913 | 0.098962 | 0.249968 | 0.21587 | 0.074606 | 0.034226 | 0.086143 |

| 0.30 | 9 | 0.150599 | 0.106242 | 0.140941 | 0.258988 | 0.204972 | 0.047934 | 0.019853 | 0.07047 |

| 0.29 | 10 | 0.141471 | 0.105263 | 0.120567 | 0.256812 | 0.241135 | 0.052632 | 0.024263 | 0.057857 |

| 0.28 | 11 | 0.131904 | 0.095567 | 0.135538 | 0.245276 | 0.211483 | 0.074128 | 0.031613 | 0.074491 |

| 0.27 | 12 | 0.12095 | 0.109071 | 0.12743 | 0.239201 | 0.177106 | 0.093952 | 0.050216 | 0.082073 |

| 0.26 | 13 | 0.105955 | 0.109049 | 0.133024 | 0.271462 | 0.243619 | 0.033256 | 0.037123 | 0.066512 |

| 0.25 | 14 | 0.100233 | 0.105672 | 0.121212 | 0.26418 | 0.218337 | 0.058275 | 0.047397 | 0.084693 |

| 0.24 | 15 | 0.080519 | 0.09697 | 0.125541 | 0.27619 | 0.182684 | 0.060606 | 0.080519 | 0.09697 |

| 0.23 | 16 | 0.080415 | 0.105058 | 0.127108 | 0.2607 | 0.204929 | 0.055772 | 0.072633 | 0.093385 |

| 0.22 | 17 | 0.066838 | 0.131105 | 0.138817 | 0.277635 | 0.137532 | 0.059126 | 0.086118 | 0.102828 |

| 0.21 | 18 | 0.075342 | 0.117808 | 0.121918 | 0.29726 | 0.152055 | 0.060274 | 0.075342 | 0.1 |

| 0.20 | 19 | 0.067282 | 0.127968 | 0.145119 | 0.255937 | 0.155673 | 0.05409 | 0.065963 | 0.127968 |

| 0.18 | 20 | 0.07003 | 0.117507 | 0.136499 | 0.307418 | 0.151929 | 0.056973 | 0.074184 | 0.08546 |

| 0.17 | 21 | 0.067269 | 0.109438 | 0.109438 | 0.283133 | 0.144578 | 0.072289 | 0.100402 | 0.113454 |

| 0.16 | 22 | 0.061901 | 0.116827 | 0.120314 | 0.294682 | 0.131648 | 0.061029 | 0.09939 | 0.114211 |

| 0.15 | 23 | 0.07309 | 0.10299 | 0.129093 | 0.282867 | 0.116754 | 0.07214 | 0.088277 | 0.134789 |

| 0.14 | 24 | 0.082532 | 0.088942 | 0.104167 | 0.354968 | 0.137019 | 0.059295 | 0.068109 | 0.104968 |

| 0.13 | 25 | 0.081273 | 0.094913 | 0.123899 | 0.351236 | 0.140097 | 0.072748 | 0.056834 | 0.079 |

| 0.12 | 26 | 0.076587 | 0.089675 | 0.10761 | 0.355793 | 0.127969 | 0.074649 | 0.06253 | 0.105187 |

| 0.11 | 27 | 0.084157 | 0.09379 | 0.104436 | 0.348796 | 0.116603 | 0.069962 | 0.084411 | 0.097845 |

| 0.10 | 28 | 0.092805 | 0.094934 | 0.106428 | 0.326096 | 0.14006 | 0.0745 | 0.052788 | 0.112388 |

| 0.09 | 29 | 0.098765 | 0.082305 | 0.089849 | 0.388889 | 0.183813 | 0.05144 | 0.044582 | 0.060357 |

| 0.08 | 30 | 0.120497 | 0.085714 | 0.093168 | 0.332919 | 0.201242 | 0.069979 | 0.027329 | 0.069151 |

| 0.06 | 31 | 0.138574 | 0.090606 | 0.116256 | 0.262825 | 0.180213 | 0.074284 | 0.055963 | 0.081279 |

| 0.05 | 32 | 0.132919 | 0.082005 | 0.124757 | 0.292654 | 0.210649 | 0.050136 | 0.038865 | 0.068014 |

| 0.04 | 33 | 0.147389 | 0.077394 | 0.105847 | 0.268317 | 0.197183 | 0.080381 | 0.035567 | 0.087921 |

| 0.03 | 34 | 0.174845 | 0.074195 | 0.082471 | 0.308306 | 0.217263 | 0.057346 | 0.026456 | 0.059119 |

| 0.02 | 35 | 0.159118 | 0.071419 | 0.101615 | 0.312196 | 0.202704 | 0.069581 | 0.017461 | 0.065905 |

| 0.01 | 36 | 0.182173 | 0.077424 | 0.099111 | 0.292128 | 0.219258 | 0.068966 | 0.014097 | 0.046845 |

| 0.00 | 37 | 0.165665 | 0.089846 | 0.111222 | 0.254509 | 0.199065 | 0.074148 | 0.036406 | 0.069138 |

| Normalized Spatio-Temporal Wildfire Probability (Eight Locations vs. 37 Periods) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color Legend | Period | Bendigo | Laverton | Mel_AP | Mildura | Nhill | Omeo | Orbost | Sale |

| 0.0170 | 1 | 0.007013 | 0.003105 | 0.003939 | 0.013009 | 0.010729 | 0.002993 | 0.001847 | 0.003532 |

| 0.0165 | 2 | 0.010148 | 0.003298 | 0.005191 | 0.016235 | 0.013569 | 0.004296 | 0.001364 | 0.004061 |

| 0.0161 | 3 | 0.010271 | 0.004265 | 0.006392 | 0.01311 | 0.012764 | 0.004296 | 0.001435 | 0.004092 |

| 0.0156 | 4 | 0.006331 | 0.002626 | 0.003766 | 0.00968 | 0.00855 | 0.002178 | 0.001634 | 0.003033 |

| 0.0151 | 5 | 0.008846 | 0.004082 | 0.005049 | 0.012612 | 0.010474 | 0.003349 | 0.001924 | 0.003013 |

| 0.0146 | 6 | 0.00911 | 0.003848 | 0.005497 | 0.011767 | 0.010098 | 0.004611 | 0.00227 | 0.004794 |

| 0.0142 | 7 | 0.005741 | 0.003664 | 0.004581 | 0.008835 | 0.007583 | 0.003206 | 0.002158 | 0.003166 |

| 0.0137 | 8 | 0.006484 | 0.003054 | 0.003929 | 0.009924 | 0.008571 | 0.002962 | 0.001359 | 0.00342 |

| 0.0132 | 9 | 0.004285 | 0.003023 | 0.004011 | 0.00737 | 0.005833 | 0.001364 | 0.000565 | 0.002005 |

| 0.0128 | 10 | 0.003858 | 0.00287 | 0.003288 | 0.007003 | 0.006576 | 0.001435 | 0.000662 | 0.001578 |

| 0.0123 | 11 | 0.003695 | 0.002677 | 0.003797 | 0.006871 | 0.005924 | 0.002077 | 0.000886 | 0.002087 |

| 0.0118 | 12 | 0.00228 | 0.002056 | 0.002402 | 0.004509 | 0.003339 | 0.001771 | 0.000947 | 0.001547 |

| 0.0113 | 13 | 0.001395 | 0.001435 | 0.001751 | 0.003573 | 0.003206 | 0.000438 | 0.000489 | 0.000875 |

| 0.0109 | 14 | 0.001313 | 0.001384 | 0.001588 | 0.003461 | 0.00286 | 0.000763 | 0.000621 | 0.00111 |

| 0.0104 | 15 | 0.000947 | 0.00114 | 0.001476 | 0.003247 | 0.002148 | 0.000713 | 0.000947 | 0.00114 |

| 0.0099 | 16 | 0.000631 | 0.000824 | 0.000998 | 0.002046 | 0.001608 | 0.000438 | 0.00057 | 0.000733 |

| 0.0094 | 17 | 0.000529 | 0.001038 | 0.001099 | 0.002199 | 0.001089 | 0.000468 | 0.000682 | 0.000814 |

| 0.0090 | 18 | 0.00056 | 0.000875 | 0.000906 | 0.002209 | 0.00113 | 0.000448 | 0.00056 | 0.000743 |

| 0.0085 | 19 | 0.000519 | 0.000987 | 0.00112 | 0.001975 | 0.001201 | 0.000417 | 0.000509 | 0.000987 |

| 0.0080 | 20 | 0.000601 | 0.001008 | 0.001171 | 0.002636 | 0.001303 | 0.000489 | 0.000636 | 0.000733 |

| 0.0076 | 21 | 0.000682 | 0.00111 | 0.00111 | 0.00287 | 0.001466 | 0.000733 | 0.001018 | 0.00115 |

| 0.0071 | 22 | 0.000723 | 0.001364 | 0.001405 | 0.00344 | 0.001537 | 0.000713 | 0.00116 | 0.001333 |

| 0.0066 | 23 | 0.000784 | 0.001104 | 0.001384 | 0.003033 | 0.001252 | 0.000774 | 0.000947 | 0.001445 |

| 0.0061 | 24 | 0.001048 | 0.00113 | 0.001323 | 0.004509 | 0.001741 | 0.000753 | 0.000865 | 0.001333 |

| 0.0057 | 25 | 0.001456 | 0.0017 | 0.002219 | 0.006291 | 0.002509 | 0.001303 | 0.001018 | 0.001415 |

| 0.0052 | 26 | 0.001608 | 0.001883 | 0.00226 | 0.007471 | 0.002687 | 0.001568 | 0.001313 | 0.002209 |

| 0.0047 | 27 | 0.00169 | 0.001883 | 0.002097 | 0.007003 | 0.002341 | 0.001405 | 0.001695 | 0.001965 |

| 0.0043 | 28 | 0.002219 | 0.00227 | 0.002545 | 0.007797 | 0.003349 | 0.001781 | 0.001262 | 0.002687 |

| 0.0038 | 29 | 0.001466 | 0.001221 | 0.001333 | 0.005771 | 0.002728 | 0.000763 | 0.000662 | 0.000896 |

| 0.0033 | 30 | 0.002962 | 0.002107 | 0.00229 | 0.008184 | 0.004947 | 0.00172 | 0.000672 | 0.0017 |

| 0.0028 | 31 | 0.004234 | 0.002769 | 0.003552 | 0.008031 | 0.005507 | 0.00227 | 0.00171 | 0.002484 |

| 0.0024 | 32 | 0.003481 | 0.002148 | 0.003267 | 0.007665 | 0.005517 | 0.001313 | 0.001018 | 0.001781 |

| 0.0019 | 33 | 0.005273 | 0.002769 | 0.003787 | 0.009599 | 0.007054 | 0.002876 | 0.001272 | 0.003145 |

| 0.0014 | 34 | 0.006021 | 0.002555 | 0.00284 | 0.010617 | 0.007482 | 0.001975 | 0.000911 | 0.002036 |

| 0.0009 | 35 | 0.006168 | 0.002769 | 0.003939 | 0.012103 | 0.007858 | 0.002697 | 0.000677 | 0.002555 |

| 0.0005 | 36 | 0.00855 | 0.003634 | 0.004652 | 0.013711 | 0.010291 | 0.003237 | 0.000662 | 0.002199 |

| 0.0000 | 37 | 0.010098 | 0.005476 | 0.006779 | 0.015513 | 0.012133 | 0.004519 | 0.002219 | 0.004214 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| 1 | |

| 0.5 | |

| 0.5 | |

| 1.029 kg·m−3 | |

| B | 5.6704 × 10−8 W·m−2·K−4 |

| 2.043 × 10−5 kg·m−1·s−1 | |

| 1200 K | |

| 0.02945 W·m−1·°C−1 | |

| 28.1 mm | |

| 534 J·m−1·°C−1 | |

| 10 m | |

| 20° | |

| 0.5 | |

| 0.07 kg·m−3 | |

| 40 kg·m−3 | |

| 75 °C | |

| 25 °C | |

| 8.688 × 10−5 Ω·m−1 | |

| 7.283 × 10−5 Ω·m−1 |

| Line | Initial Distance from Wildfire (m) | Line | Initial Distance from Wildfire (m) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From Bus | To Bus | From Bus | To Bus | ||

| 1 | 2 | 8508.82 | 17 | 18 | 3568.17 |

| 2 | 3 | 791.79 | 2 | 19 | 5096.13 |

| 3 | 4 | 6414.63 | 19 | 20 | 5675.60 |

| 4 | 5 | 5375.87 | 20 | 21 | 8805.11 |

| 5 | 6 | 3071.61 | 21 | 22 | 5040.00 |

| 6 | 7 | 5629.39 | 3 | 23 | 7442.60 |

| 7 | 8 | 5629.39 | 23 | 24 | 6628.73 |

| 8 | 9 | 4205.05 | 24 | 25 | 4464.59 |

| 9 | 10 | 6966.17 | 6 | 26 | 6000.00 |

| 10 | 11 | 4456.69 | 26 | 27 | 4929.21 |

| 11 | 12 | 8607.36 | 27 | 28 | 3473.66 |

| 12 | 13 | 5234.50 | 28 | 29 | 6150.51 |

| 13 | 14 | 404.94 | 29 | 30 | 4505.04 |

| 14 | 15 | 3492.85 | 30 | 31 | 7075.58 |

| 15 | 16 | 957.66 | 31 | 32 | 193.48 |

| 16 | 17 | 3727.21 | 32 | 33 | 4593.29 |

| Lines | Initial Distance from Wildfire (m) | Outage Hour | Lines | Initial Distance from Wildfire (m) | Outage Hour | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From Bus | To Bus | From Bus | To Bus | ||||

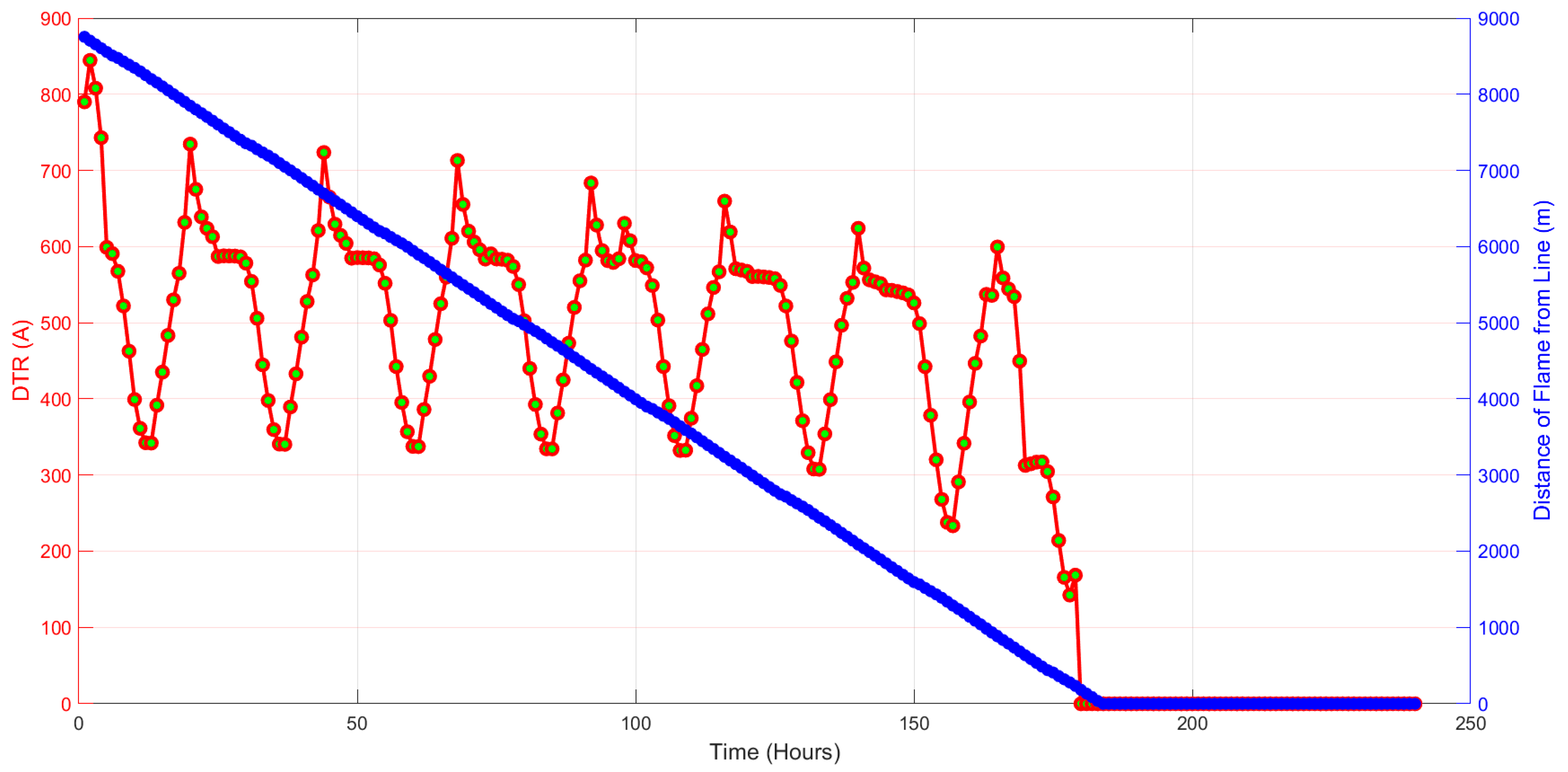

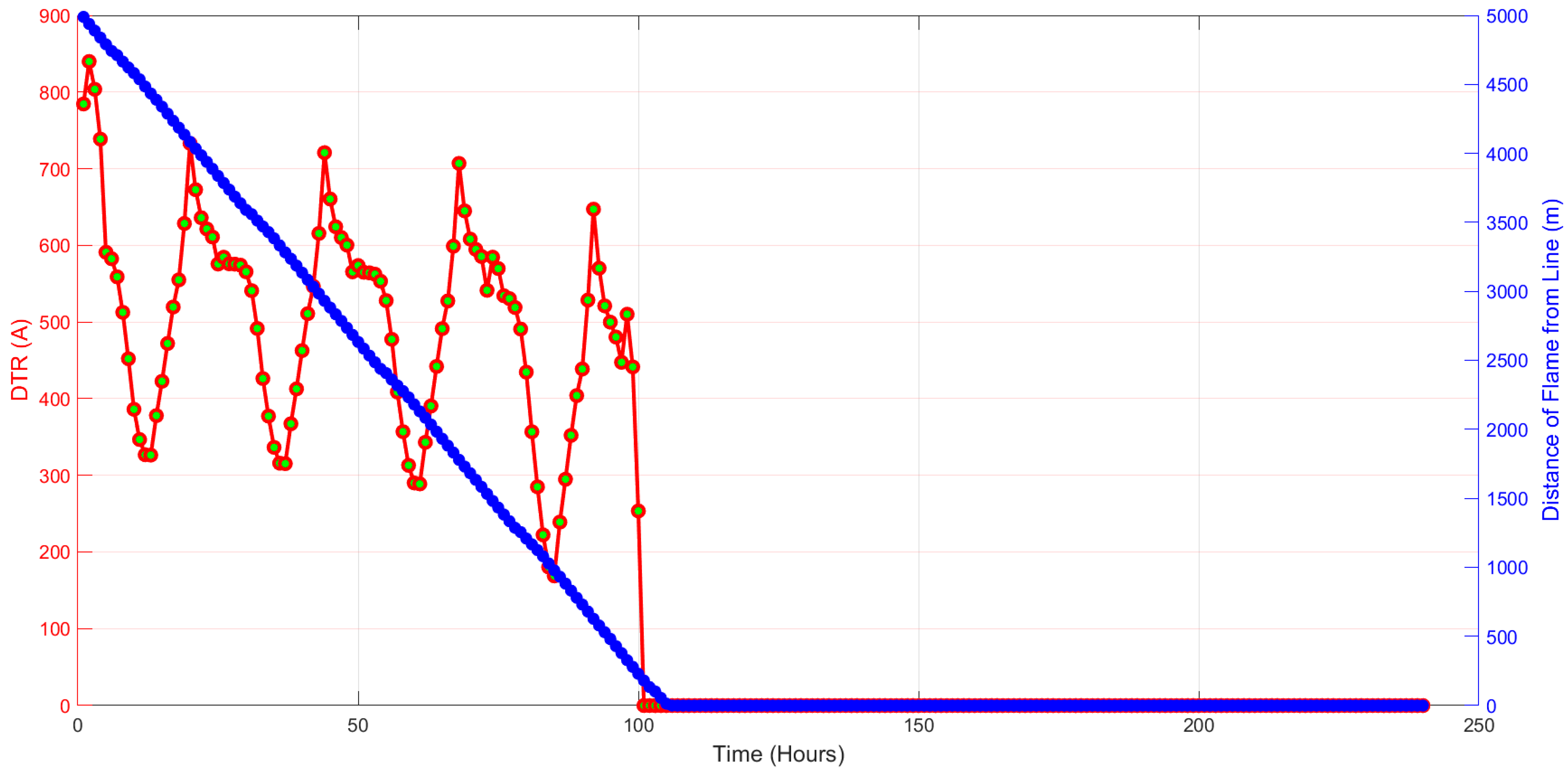

| 1 | 2 | 8508.82 | 174 | 17 | 18 | 3568.17 | 71 |

| 2 | 3 | 791.79 | 13 | 2 | 19 | 5096.13 | 102 |

| 3 | 4 | 6414.63 | 131 | 19 | 20 | 5675.60 | 115 |

| 4 | 5 | 5375.87 | 109 | 20 | 21 | 8805.11 | 180 |

| 5 | 6 | 3071.61 | 61 | 21 | 22 | 5040.00 | 101 |

| 6 | 7 | 5629.39 | 114 | 3 | 23 | 7442.60 | 152 |

| 7 | 8 | 5629.39 | 114 | 23 | 24 | 6628.73 | 135 |

| 8 | 9 | 4205.05 | 85 | 24 | 25 | 4464.59 | 90 |

| 9 | 10 | 6966.17 | 142 | 6 | 26 | 6000.00 | 121 |

| 10 | 11 | 4456.69 | 90 | 26 | 27 | 4929.21 | 100 |

| 11 | 12 | 8607.36 | 179 | 27 | 28 | 3473.66 | 69 |

| 12 | 13 | 5234.50 | 106 | 28 | 29 | 6150.51 | 124 |

| 13 | 14 | 404.94 | 5 | 29 | 30 | 4505.04 | 90 |

| 14 | 15 | 3492.85 | 69 | 30 | 31 | 7075.58 | 144 |

| 15 | 16 | 957.66 | 17 | 31 | 32 | 193.48 | 1 |

| 16 | 17 | 3727.21 | 75 | 32 | 33 | 4593.29 | 92 |

| HESS Bus No. | Initial Distance from Wildfire (m) | Outage Hour | HESS Bus No. | Initial Distance from Wildfire (m) | Outage Hour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 12,420.14 | NA | 22 | 5531.73 | 116 |

| 6 | 11,236.10 | 235 | 5 | 5375.87 | 113 |

| 25 | 10,985.90 | 230 | 13 | 5234.50 | 110 |

| 28 | 10,651.29 | 222 | 17 | 3883.30 | 82 |

| 23 | 10,542.30 | 220 | 15 | 3492.85 | 73 |

| DER Bus No. | Initial Distance from Wildfire (m) | Outage Hour | DER Bus No. | Initial Distance from Wildfire (m) | Outage Hour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 12,420.14 | NA | 21 | 8805.11 | 184 |

| 8 | 8649.28 | 181 | 30 | 8121.58 | 170 |

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buses hosting HESS | - | 5, 13, 15, 17, 22 | 6, 14, 23, 25, 28 |

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EENS (MWh) | 219.901 | 210.744 | 177.241 |

| EENS in % of total Demand | 0.223 | 0.214 | 0.180 |

| Improvement in EENS w.r.t Case 1 | - | 4.16% | 19.40% |

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EENS (MWh) | 339.043 | 324.729 | 282.646 |

| EENS in % of total Demand | 0.344 | 0.329 | 0.286 |

| Deviation with respect to probabilistic approach | 54.18% | 54.09% | 59.47% |

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EENS (MWh) | 1555.569 | 1492.951 | 1214.948 |

| EENS in % of total Demand | 1.576 | 1.513 | 1.231 |

| Deviation with respect to probabilistic approach | 607.40% | 608.42% | 585.48% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aslam, M.U.; Shakhawat, N.S.B.; Shah, R.; Amjady, N. Probabilistic Resilience Enhancement of Active Distribution Networks Against Wildfires Using Hybrid Energy Storage Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13072. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413072

Aslam MU, Shakhawat NSB, Shah R, Amjady N. Probabilistic Resilience Enhancement of Active Distribution Networks Against Wildfires Using Hybrid Energy Storage Systems. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13072. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413072

Chicago/Turabian StyleAslam, Muhammad Usman, Nusrat Subah Binte Shakhawat, Rakibuzzaman Shah, and Nima Amjady. 2025. "Probabilistic Resilience Enhancement of Active Distribution Networks Against Wildfires Using Hybrid Energy Storage Systems" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13072. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413072

APA StyleAslam, M. U., Shakhawat, N. S. B., Shah, R., & Amjady, N. (2025). Probabilistic Resilience Enhancement of Active Distribution Networks Against Wildfires Using Hybrid Energy Storage Systems. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13072. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413072